for Robert Filomeno (1949-86), who loved peace and died of AIDS

(Plate 2)

If Koch's postulates must be fulfilled to identify a given microbe with a given disease, perhaps it would be helpful, in rewriting the AIDS text, to take 'Turner's postulates' into account (1984, p. 209): 1) disease is a language; 2) the body is a representation; and 3) medicine is a political practice. (Treichler, 1987, p. 27)

Non-self: A term covering everything which is detectably different from an animal's own constituents. (Playfair, 1984, p. 1)

[T]he immune system must recognize self in some manner in order to react to something foreign. (Golub, 1987, p. 484)

It has become commonplace to emphasize the multiple and specific cultural dialects interlaced in any social negotiation of disease and sickness in the contemporary worlds marked by biological research, biotechnology, and scientific medicine. The language of biomedicine is never alone in the field of empowering meanings, and its power does not flow from a consensus about symbols and actions in the face of suffering. Paula Treichler's (1987) excellent phrase in the tide of her essay on the constantly contested meanings of AIDS as an 'epidemic of signification' could be applied widely to the social text of sickness. The power of biomedical language - with its stunning artefacts, images, architectures, social forms, and technologies - for shaping the unequal experience of sickness and death for millions is a social fact deriving from ongoing heterogeneous social processes. The power of biomedicine and biotechnology is constantly re-produced, or it would cease. This power is not a thing fixed and permanent, embedded in plastic and ready to section for microscopic observation by the historian or critic. The cultural and material authority of biomedicine's productions of bodies and selves is more vulnerable, more dynamic, more elusive, and more powerful than that.

But if there has been recognition of the many non-, para-, anti-, or extra-scientific languages in company with biomedicine that structure the embodied semiosis of mortality in the industrialized world, it is much less common to find emphasis on the multiple languages within the territory that is often so glibly marked scientific. 'Science says' is represented as a univocal language. Yet even the spliced character of the potent words in 'science' hints at a barely contained and inharmonious heterogeneity. The words for the overlapping discourses and their objects of knowledge, and for the abstract corporate names for the concrete places where the discourse-building work is done, suggest both the blunt foreshortening of technicist approaches to communication and the uncontainable pressures and confusions at the boundaries of meanings within 'science' - biotechnology, biomedicine, psychoneuroimmunology, immunogenetics, immunoendo-crinology, neuroendocrinology, monoclonal antibodies, hybridomas, inter-leukines, Genentech, Embrex, Immunetech, Biogen.

This chapter explores some of the contending popular and technical languages constructing biomedical, biotechnical bodies and selves in postmodern scientific culture in the United States in the 1980s. Scientific discourses are 'lumpy'; they contain and enact condensed contestations for meanings and practices. The chief object of my attention will be the potent and polymorphous object of belief, knowledge, and practice called the immune system. My thesis is that the immune system is an elaborate icon for principal systems of symbolic and material 'difference' in late capitalism. Pre-eminently a twentieth-century object, the immune system is a map drawn to guide recognition and misrecognition of self and other in the dialectics of Western biopolitics. That is, the immune system is a plan for meaningful action to construct and maintain the boundaries for what may count as self and other in the crucial realms of the normal and the pathological. The immune system is a historically specific terrain, where global and local politics; Nobel Prize-winning research; heteroglossic cultural productions, from popular dietary practices, feminist science fiction, religious imagery, and children's games, to photographic techniques and military strategic theory; clinical medical practice; venture capital investment strategies; world-changing developments in business and technology; and the deepest personal and collective experiences of embodiment, vulnerability, power, and mortality interact with an intensity matched perhaps only in the biopolitics of sex and reproduction.2

The immune system is both an iconic mythic object in high-technology culture and a subject of research and clinical practice of the first importance. Myth, laboratory, and clinic are intimately interwoven. This mundane point was fortuitously captured in the title listings in the 1986-87 Books in Print, where I was searching for a particular undergraduate textbook on immunology. The several pages of entries beginning with the prefix 'immuno-' were bounded, according to the English rules of alphabetical listing, by a volume called Immortals of Science Fiction, near one end, and by The Immutability of God, at the other. Examining the last section of the textbook to which Boob in Print led me, Immunology: A Synthesis (Golub, 1987), I found what I was looking for: a historical progression of diagrams of theories of immunological regulation and an obituary for their draftsman, an important immunologist, Richard K. Gershon, who 'discovered' the suppressor T cell. The standard obituary tropes for the scientist, who 'must have had what the earliest explorers had, an insatiable desire to be the first person to see something, to know that you are where no man has been before', set the tone. The hero-scientist 'gloried in the layer upon interconnected layer of [the immune response's] complexity. He thrilled at seeing a layer of that complexity which no one had seen before' (Golub, 1987, pp. 531-2). It is reasonable to suppose that all the likely readers of this textbook have been reared within hearing range of the ringing tones of the introduction to the voyages of the federation starship Enterprise in Star Trek - to boldly go where no man has gone before. Science remains an important genre of Western exploration and travel literature. Similarly, no reader, no matter how literal-minded, could be innocent of the gendered erotic trope that figures the hero's probing into nature's laminated secrets, glorying simultaneously in the layered complexity and in his own techno-erotic touch that goes ever deeper. Science as heroic quest and as erotic technique applied to the body of nature are utterly conventional figures. They take on a particular edge in late twentieth-century immune system discourse, where themes of nuclear exterminism, space adventure, extra-terrestrialism, exotic invaders, and military high-technology are pervasive.

But Golub's and Gershon's intended and explicit text is not about space invaders and the immune system as a Star Wars prototype. Their theme is the love of complexity and the intimate natural bodily technologies for generating the harmonies of organic life. In four illustrations — dated 1968, 1974, 1977, and 1982 - Gershon sketched his conception of 'the immunological orchestra' (Golub, 1987, pp. 533-6). This orchestra is a wonderful picture of the mythic and technical dimensions of the immune system (Plates 3-6). All the illustrations are about co-operation and control, the major themes of organismic biology since the late eighteenth century. From his commanding position in the root of a lymph node, the G.O.D. of the first illustration conducts the orchestra of T and B cells and macrophages as they march about the body and play their specific parts (Plate 3). The lymphocytes all look like Casper the ghost with the appropriate distinguishing nuclear morphologies drawn in the centre of their shapeless bodies. Baton in hand, G.O.D.'s arms are raised in quotation of a symphonic conductor. G.O.D. recalls the other 1960s bioreligious, Nobel Prize-winning 'joke' about the coded bodily text of post-DNA biology and medicine - the Central Dogma of molecular biology, specifying that 'information' flows only from DNA to RNA to protein. These three were called the Blessed Trinity of the secularized sacred body, and histories of the great adventures of molecular biology could be tided The Eighth Day of Creation (Judson, 1979), an image that takes on a certain irony in the venture capital and political environments of current biotechnology companies, like Genentech. In the technical-mythic systems of molecular biology, code rules embodied structure and function, never the reverse. Genesis is a serious joke, when the body is theorized as a coded text whose secrets yield only to the proper reading conventions, and when the laboratory seems best characterized as a vast assemblage of technological and organic inscription devices. The Central Dogma was about a master control system for information flow in the codes that determine meaning in the great technological communication systems that organisms progressively have become after the Second World War. The body is an artificial intelligence system, and the relation of copy and original is reversed and then exploded.

G.O.D. is the Generator of Diversity, the source of the awe-inspiring multiple specificities of the polymorphous system of recognition and misrecognition we call the immune system. By the second illustration (1974), G.O.D. is no longer in front of the immune orchestra, but is standing, arms folded, looking authoritative but not very busy, at the top of the lymph node, surrounded by the musical lymphocytes (Plate 4). A special cell, the T suppressor cell, has taken over the role of conductor. By 1977, the illustration (Plate 5) no longer has a single conductor, but is 'led' by three mysterious subsets of T cells, who hold a total of twelve batons signifying their direction-giving surface identity markers; and G.O.D. scratches his head in patent confusion. But the immune band plays on. In the final illustration, from 1982, (Plate 6) 'the generator of diversity seems resigned to the conflicting calls of the angels of help and suppression', who perch above his left and right shoulders (Golub, 1987, p. 536). Besides G.O.D. and the two angels, there is a T cell conductor and two conflicting prompters, 'each urging its own interpretation'. The joke of single masterly control of organismic harmony in the symphonic system responsible for the integrity of 'self' has become a kind of postmodern pastiche of multiple centres and peripheries, where the immune music that the page suggests would surely sound like nursery school space music. All the actors that used to be on the stage-set for the unambiguous and coherent biopolitical subject are still present, but their harmonies are definitely a bit problematic.

By the 1980s, the immune system is unambiguously a postmodern object - symbolically, technically, and politically. Katherine Hayles (1987b) characterizes postmodernism in terms of 'three waves of developments occurring at multiple sites within the culture, including literature and science'. Her archaeology begins with Saussurean linguistics, through which symbol systems were 'denaturalized'. Internally generated relational difference, rather than mimesis, ruled signification. Hayles sees the culmination of this approach in Claude Shannon's mid-century statistical theory of information, developed for packing the largest number of signals on a transmission line for the Bell Telephone Company and extended to cover communication acts in general, including those directed by the codes of bodily semiosis in ethology or molecular biology. 'Information' generating and processing systems, therefore, are postmodern objects, embedded in a theory of internally differentiated signifiers and remote from doctrines of representation as mimesis. A history-changing artefact, 'information' exists only in very specific kinds of universes. 3 Progressively, the world and the sign seemed to exist in incommensurable universes - there was literally no measure linking them, and the reading conventions for all texts came to resemble those required for science fiction. What emerged was a global technology that 'made the separation of text from context an everyday experience'. Hayles's second wave, 'energized by the rapid development of information technology, made the disappearance of stable, reproducible context an international phenomenon ... Context was no longer a natural part of every experience, but an artifact that could be altered at will.' Hayles's third wave of denaturalization concerned time. 'Beginning with the Special Theory of Relativity, time increasingly came to be seen not as an inevitable progression along a linear scale to which all humans were subject, but as a construct that could be conceived in different ways.'

Language is no longer an echo of the verbum dei, but a technical construct working on principles of internally generated difference. If the early modern natural philosopher or Renaissance physician conducted an exegesis of the text of nature written in the language of geometry or of cosmic correspondences, the postmodern scientist still reads for a living, but has as a text the coded systems of recognition - prone to the pathologies of mis-recognition embodied in objects like computer networks and immune systems. The extraordinarily close tie of language and technology could hardly be overstressed in postmodernism. The 'construct' is at the centre of attention; making, reading, writing, and meaning seem to be very close to the same thing. This near-identity between technology, body, and semiosis suggests a particular edge to the mutually constitutive relations of political economy, symbol, and science that 'inform' contemporary research trends in medical anthropology.

Bodies, then, are not born; they are made (Plate 7). Bodies have been as thoroughly denaturalized as sign, context, and time. Late twentieth-century bodies do not grow from internal harmonic principles theorized within Romanticism. Neither are they discovered in the domains of realism and modernism. One is not born a woman, Simone de Beauvoir correctly insisted. It took the political-epistemological terrain of postmodernism to be able to insist on a co-text to de Beauvoir's: one is not born an organism. Organisms are made; they are constructs of a world-changing kind. The constructions of an organism's boundaries, the job of the discourses of immunology, are particularly potent mediators of the experiences of sickness and death for industrial and post-industrial people.

In this over-determined context, I will ironically - and inescapably invoke a constructionist concept as an analytic device to pursue an understanding of what kinds of units, selves, and individuals inhabit the universe structured by immune system discourse: This conceptual tool, 'the apparatus of bodily production', was discussed earlier on pp. 197-201 (King, 1987b). Scientific bodies are not ideological constructions. Always radically historically specific, bodies have a different kind of specificity and effectivity, and so they invite a different kind of engagement and intervention. The notion of a 'material-semiotic actor' is intended to highlight the object of knowledge as an active part of the apparatus of bodily production, without ever implying immediate presence of such objects or, what is the same thing, their final or unique determination of what can count as objective knowledge of a biomedical body at a particular historical juncture. Bodies as objects of knowledge are material-semiotic generative nodes. Their boundaries materialize in social interaction; 'objects' like bodies do not pre-exist as such. Scientific objectivity (the siting/sighting of objects) is not about dis-engaged discovery, but about mutual and usually unequal structuring, about taking risks. The various contending biological bodies emerge at the intersection of biological research, writing, and publishing; medical and other business practices; cultural productions of all kinds, including available metaphors and narratives; and technology, such as the visualization technologies that bring colour-enhanced killer T cells and intimate photographs of the developing foetus into high-gloss art books for every middle-class home (Nilsson, 1977, 1987).

But also invited into that node of intersection is the analogue to the lively languages that actively intertwine in the production of literary value: the coyote and protean embodiments of a world as witty agent and actor. Perhaps our hopes for accountability in the techno-biopolitics in postmodern frames turn on revisioning the world as coding trickster with whom we must learn to converse. Like a protein subjected to stress, the world for us may be thoroughly denatured, but it is not any less consequential. So while the late twentieth-century immune system is a construct of an elaborate apparatus of bodily production, neither the immune system nor any other of biomedicine's world-changing bodies - like a virus - is a ghostly fantasy. Coyote is not a ghost, merely a protean trickster.

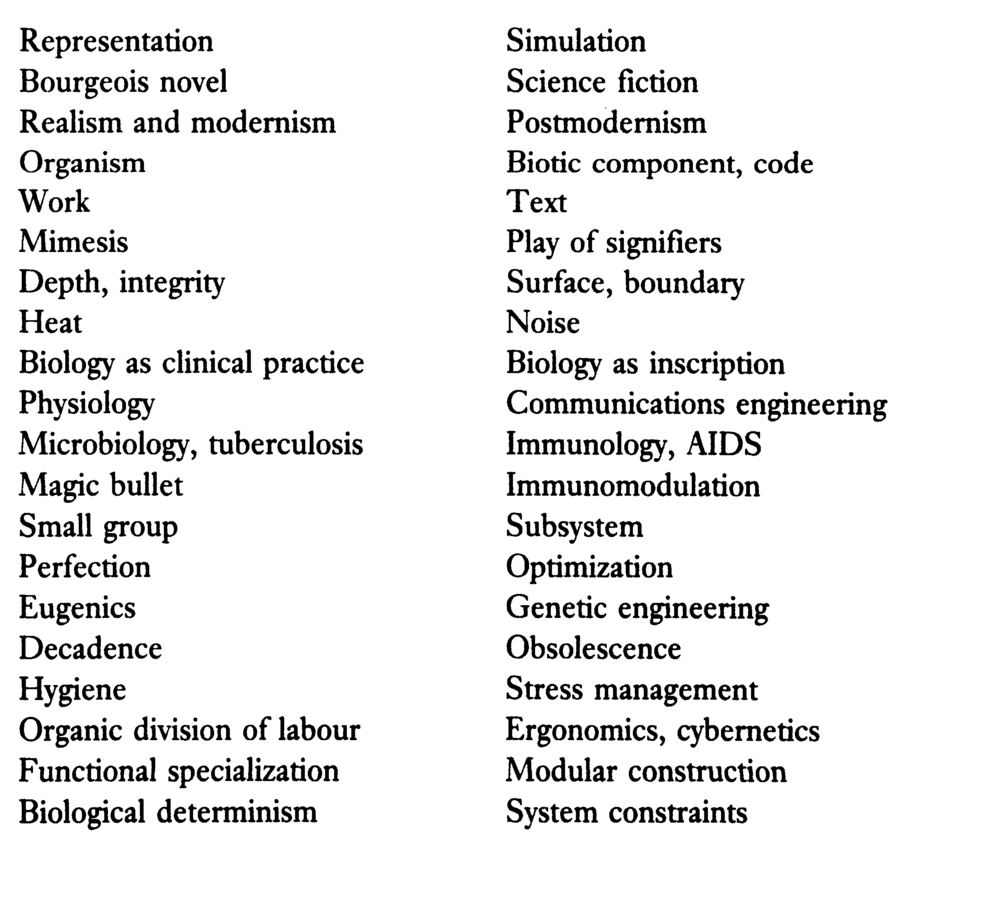

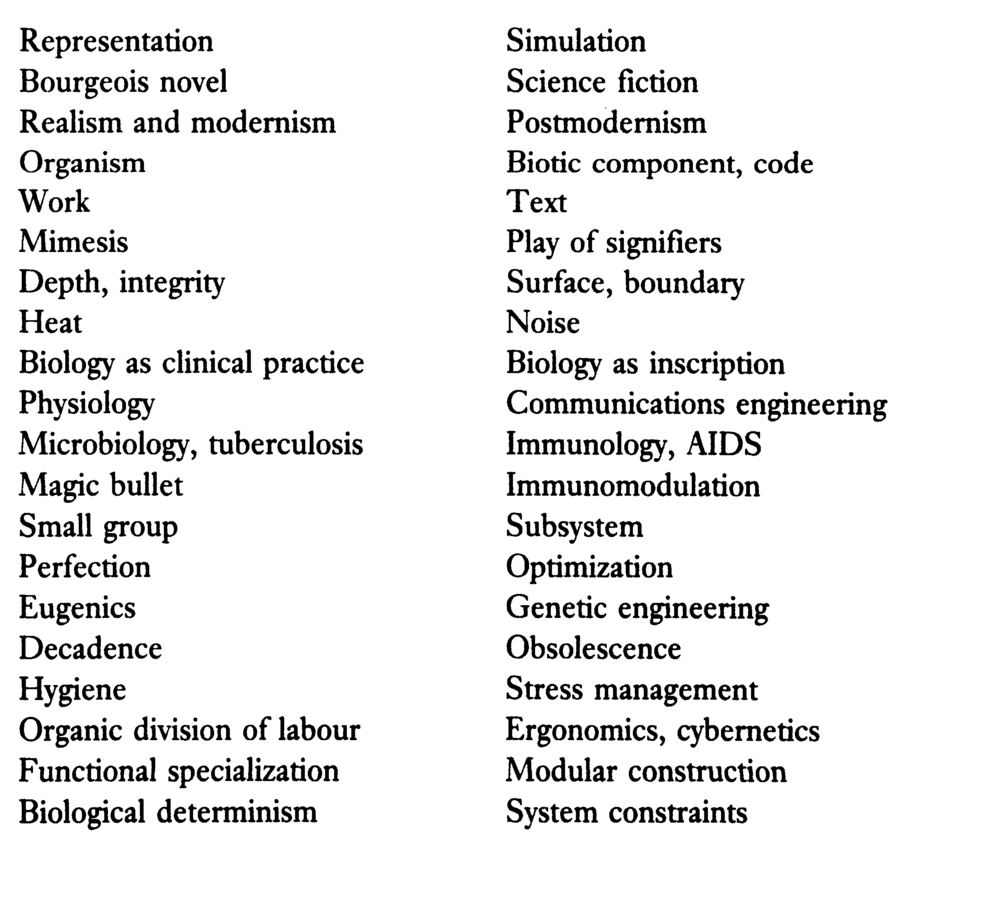

The following chart abstracts and dichotomizes two historical moments in the biomedical production of bodies from the late nineteenth century to the 1980s. The chart highlights epistemological, cultural, and political aspects of possible contestations for constructions of scientific bodies in this century. The chart itself is a traditional little machine for making particular meanings. Not a description, it must be read as an argument, and one which relies on a suspect technology for the production of meanings - binary dichotomization.

It is impossible to see the entries in the right-hand column as 'natural', a realization that subverts naturalistic status for the left-hand column as well. From the eighteenth to the mid-twentieth centuries, the great historical constructions of gender, race, and class were embedded in the organically marked bodies of woman, the colonized or enslaved, and the worker. Those inhabiting these marked bodies have been symbolically other to the Active rational self of universal, and so unmarked, species man, a coherent subject. The marked organic body has been a critical locus of cultural and political contestation, crucial both to the language of the liberatory politics of identity and to systems of domination drawing on widely shared languages of nature as resource for the appropriations of culture. For example, the sexualized bodies of nineteenth-century middle-class medical advice literature in England and the United States, in their female form organized around the maternal function and the physical site of the uterus and in their male form ordered by the spermatic economy tied closely to the nervous system, were part of an elaborate discourse of organic economy. The narrative field in which these bodies moved generated accounts of rational citizenship, bourgeois family life, and prophylaxis against sexual pollution and inefficiency, such as prostitution, criminality, or race suicide. Some feminist politics argued for the full inclusion of women in the body politic on grounds of maternal functions in the domestic economy extended to a public world. Late into the twentieth century, gay and lesbian politics have ironically and critically embraced the marked bodies constructed in nineteenth- and twentieth-century sexologies and gender identity medicines to create a complex humanist discourse of sexual liberation. Negritude, feminine writing, various separatisms, and other recent cultural movements have both drawn on and subverted the logics of naturalization central to biomedical discourse on race and gender in the histories of colonization and male supremacy. In all of these various, oppositionally interlinked, political and biomedical accounts, the body remained a relatively unambiguous locus of identity, agency, labour, and hierarchicalized function. Both scientific humanisms and biological determinisms could be authorized and contested in terms of the biological organism crafted in post-eighteenth-century life sciences.

But how do narratives of the normal and the pathological work when the biological and medical body is symbolized and operated upon, not as a system of work, organized by the hierarchical division of labour, ordered by a privileged dialectic between highly localized nervous and reproductive functions, but instead as a coded text, organized as an engineered communications system, ordered by a fluid and dispersed command-control intelligence network? From the mid-twentieth century, biomedical discourses have been progressively organized around a very different set of technologies and practices, which have destabilized the symbolic privilege of the hierarchical, localized, organic body. Concurrently - and out of some of the same historical matrices of decolonization, multinational capitalism, world-wide high-tech militarization, and the emergence of new collective political actors in local and global politics from among those persons previously consigned to labour in silence - the question of 'differences' has destabilized humanist discourses of liberation based on a politics of identity and substantive unity. Feminist theory as a self-conscious discursive practice has been generated in this post-Second World War period characterized by the translation of Western scientific and political languages of nature from those based on work, localization, and the marked body to those based on codes, dispersal and networking, and the fragmented postmodern subject. An account of the biomedical, biotechnical body must start from the multiple molecular interfacings of genetic, nervous, endocrine, and immune systems. Biology is about recognition and misrecognition, coding errors, the body's reading practices (for example, frameshift mutations), and billion-dollar projects to sequence the human genome to be published and stored in a national genetic 'library'. The body is conceived as a strategic system, highly militarized in key arenas of imagery and practice. Sex, sexuality, and reproduction are theorized in terms of local investment strategies; the body ceases to be a stable spatial map of normalized functions and instead emerges as a highly mobile field of strategic differences. The biomedical-biotechnical body is a semiotic system, a complex meaning-producing field, for which the discourse of immunology, that is, the central biomedical discourse on recognition/misrecognition, has become a high-stakes practice in many senses.

In relation to objects like biotic components and codes, one must think, not in terms of laws of growth and essential properties, but rather in terms of strategies of design, boundary constraints, rates of flows, system logics, and costs of lowering constraints. Sexual reproduction becomes one possible strategy among many, with costs and benefits theorized as a function of the system environment. Disease is a subspecies of information malfunction or communications pathology; disease is a process of misrecognition or transgression of the boundaries of a strategic assemblage called self. Ideologies of sexual reproduction can no longer easily call upon the notions of unproblematic sex and sex role as organic aspects in 'healthy' natural objects like organisms and families. Likewise for race, ideologies of human diversity have to be developed in terms of frequencies of parameters and fields of power-charged differences, not essences and natural origins or homes. Race and sex, like individuals, are artefacts sustained or undermined by the discursive nexus of knowledge and power. Any objects or persons can be reasonably thought of in terms of disassembly and reassembly; no 'natural' architectures constrain system design. Design is none the less highly constrained. What counts as a 'unit', a one, is highly problematic, not a permanent given. Individuality is a strategic defence problem.

One should expect control strategies to concentrate on boundary conditions and interfaces, on rates of flow across boundaries, not on the integrity of natural objects. 'Integrity' or 'sincerity' of the Western self gives way to decision procedures, expert systems, and resource investment strategies. 'Degrees of freedom' becomes a very powerful metaphor for politics. Human beings, like any other component or subsystem, must be localized in a system architecture whose basic modes of operation are probabilistic. No objects, spaces, or bodies are sacred in themselves; any component can be interfaced with any other if the proper standard, the proper code, can be constructed for processing signals in a common language. In particular, there is no ground for ontologically opposing the organic, the technical, and the textual.4 But neither is there any ground for opposing the mythical to the organic, textual, and technical. Their convergences are more important than their residual oppositions. The privileged pathology affecting all kinds of components in this universe is stress - communications breakdown. In the body stress is theorized to operate by 'depressing' the immune system. Bodies have become cyborgs - cybernetic organisms - compounds of hybrid techno-organic embodiment and textuality (Haraway, 1985 [this vol. pp. 149-81]). The cyborg is text, machine, body, and metaphor - all theorized and engaged in practice in terms of communications.

However, just as the nineteenth- and twentieth-century organism accommodated a diverse field of cultural, political, financial, theoretic and technical contestation, so also the cyborg is a contested and heterogeneous construct. It is capable of sustaining oppositional and liberatory projects at the levels of research practice, cultural productions, and political intervention. This large theme may be introduced by examining contrasting constructions of the late twentieth-century biotechnical body, or of other contemporary postmodern communications systems. These constructs may be conceived and built in at least two opposed modes: (1) in terms of master control principles, articulated within a rationalist paradigm of language and embodiment; or (2) in terms of complex, structurally embedded semiosis with many 'generators of diversity' within a counter-rationalist (not irrationalist) or hermeneutic/situationist/constructivist discourse readily available within Western science and philosophy. Terry Winograd and Fernando Flores' (1986) joint work on Understanding Computers and Cognition is particularly suggestive for thinking about the potentials for cultural/scientific/political contestation over the technologies of representation and embodiment of 'difference' within immunological discourse, whose object of knowledge is a kind of 'artificial intelligence/language/communication system of the biological body'.6

Winograd and Flores conduct a detailed critique of the rationalist paradigm for understanding embodied (or 'structure-determined') perceptual and language systems and for designing computers that can function as prostheses in human projects. In the simple form of the rationalist model of cognition,

One takes for granted the existence of an objective reality made up of things bearing properties and entering into relations. A cognitive being gathers 'information' about those things and builds up a mental 'model' which will be in some respects correct (a faithful representation of reality) and in other respects incorrect. Knowledge is a storehouse of representations that can be called upon to do reasoning and that can be translated into language. Thinking is a process of manipulating those representations'. (Winograd, in Edwards and Gordon, forthcoming)

It is this doctrine of representation that Winograd finds wrong in many senses, including on the plane of political and moral discourse usually suppressed in scientific writing. The doctrine, he continues, is also technically wrong for further guiding research in software design: 'Contrary to common consensus, the "commonsense" understanding of language, thought, and rationality inherent in this tradition ultimately hinders the fruitful application of computer technology to human life and work'. Drawing on Heidegger, Gadamer, Maturana, and others, Winograd and Flores develop a doctrine of interdependence of interpreter and interpreted, which are not discrete and independent entities. Situated pre-understandings are critical to all communication and action. 'Structure-determined systems' with histories shaped through processes of 'structural-coupling' give a better approach to perception than doctrines of representation.

Changes in the environment have the potential of changing the relative patterns of activity within the nervous system itself that in turn orient the organism's behavior, a perspective that invalidates the assumption that we acquire representations of our environment. Interpretation, that is, arises as a necessary consequence of the structure of biological beings. (Winograd, in Edwards and Gordon, forthcoming)

Winograd conceives the coupling of the inner and outer worlds of organisms and ecosystems, of organisms with each other, or of organic and technical structures in terms of metaphors of language, communication, and construction - but not in terms of a rationalist doctrine of mind and language or a disembodied instrumentalism. Linguistic acts involve shared acts of interpretation, and they are fundamentally tied to engaged location in a structured world. Context is a fundamental matter, not as surrounding 'information', but as co-structure or co-text. Cognition, engagement, and situation-dependence are linked concepts for Winograd, technically and philosophically. Language is not about description, but about commitment. The point applies to 'natural' language and to 'built' language.

How would such a way of theorizing the technics and biologies of communication affect immune system discourse about the body's 'technology' for recognizing self and other and for mediating between 'mind' and 'body' in postmodern culture? Just as computer design is a map of and for ways of living, the immune system is in some sense a diagram of relationships and a guide for action in the face of questions about the boundaries of the self and about mortality. Immune system discourse is about constraint and possibility for engaging in a world of full of 'difference', replete with non-self. Winograd and Flores' approach contains a way to contest for notions of pathology, or 'breakdown', without militarizing the terrain of the body.

Breakdowns play a central role in human understanding. A breakdown is not a negative situation to be avoided, but a situation of non-obviousness, in which some aspect of the network of tools that we are engaged in using is brought forth to visibility ... A breakdown reveals the nexus of relations necessary for us to accomplish our task ... This creates a clear objective for design - to anticipate the form of breakdowns and provide a space of possibilities for action when they occur. (Winograd, in Edwards and Gordon, forthcoming)

This is not a Star Wars or Strategic Computing Initiative relation to vulnerability, but neither does it deny therapeutic action. It insists on locating therapeutic, reconstructive action (and so theoretic understanding) in terms of situated purposes, not fantasies of the utterly defended self in a body as automated militarized factory, a kind of ultimate self as Robotic Battle Manager meeting the enemy (not-self) as it invades in the form of bits of foreign information threatening to take over the master control codes.

Situated purposes are necessarily finite, rooted in partiality and a subtle play of same and different, maintenance and dissolution. Winograd and Flores' linguistic systems are 'denaturalized', fully constructivist entities; and in that sense they are postmodern cyborgs that do not rely on impermeable boundaries between the organic, technical, and textual. But their linguistic/ communication systems are distinctly oppositional to the AI cyborgs of an 'information society', with its exterminist pathologies of final abstraction from vulnerability, and so from embodiment.7

What is constituted as an individual within postmodern biotechnical, biomedical discourse? There is no easy answer to this question, for even the most reliable Western individuated bodies, the mice and men of a well-equipped laboratory, neither stop nor start at the skin, which is itself something of a teeming jungle threatening illicit fusions, especially from the perspective of a scanning electron microscope. The multi-billion-dollar project to sequence 'the human genome' in a definitive genetic library might be seen as one practical answer to the construction of 'man' as 'subject' of science. The genome project is a kind of technology of postmodern humanism, defining 'the' genome by reading and writing it. The technology required for this particular kind of literacy is suggested by the advertisment for MacroGene Workstation. The ad ties the mythical, organic, technical, and textual together in its graphic invocation of the 'missing link' crawling from the water on to the land, while the text reads, 'In the LKB MacroGene Workstation [for sequencing nucleic acids], there are no "missing links".' (See Plate 8.) The monster Ichthyostega crawling out of the deep in one of earth's great transitions is a perfect figure for late twentieth-century bodily and technical metamorphoses. An act of canonization to make the theorists of the humanities pause, the standard reference work called the human genome would be the means through which human diversity and its pathologies could be tamed in die exhaustive code kept by a national or international genetic bureau of standards. Costs of storage of the giant dictionary will probably exceed costs of its production, but this is a mundane matter to any librarian (Roberts, 1987a,b,c; Kanigel, 1987). Access to this standard for 'man' will be a matter of international financial, patent, and similar struggles. The Peoples of the Book will finally have a standard genesis story. In the beginning was the copy.

The Human Genome Project might define postmodern species being (pace the philosophers), but what of individual being? Richard Dawkins raised this knotty problem in The Extended Phenotype. He noted that in 1912, Julian Huxley defined individuality in biological terms as 'literally indivisibility - the quality of being sufficiently heterogeneous in form to be rendered non-functional if cut in half' (Dawkins, 1982, p. 250). That seems a promising start. In Huxley's terms, surely you or I would count as an individual, while many worms would not. The individuality of worms was not achieved even at the height of bourgeois liberalism, so no cause to worry there. But Huxley's definition does not answer which function is at issue. Nothing answers that in the abstract; depends on what is to be done.8 You or I (whatever problematic address these pronouns have) might be an individual for some purposes, but not for others. This is a normal ontological state for cyborgs and women, if not for Aristotelians and men. Function is about action. Here is where Dawkins has a radical solution, as he proposes a view of individuality that is strategic at every level of meaning. There are many kinds of individuals for Dawkins, but one kind has primacy. 'The whole purpose of our search for a "unit of selection" is to discover a suitable actor to play the leading role in our metaphors of purpose' (1982, p. 91). The 'metaphors of purpose' come down to a single bottom line: replication. 'A successful replicator is one that succeeds in lasting, in the form of copies, for a very long time measured in generations, and succeeds in propogating many copies of itself' (1982, pp. 87-8).

The replicator fragment whose individuality finally matters most, in the constructed time of evolutionary theory, is not particularly 'unitary'. For all that it serves, for Dawkins, as the 'unit' of natural selection, the replicator's boundaries are not fixed and its inner reaches remain mutable. But still, these units must be a bit smaller than a 'single' gene coding for a protein. Units are only good enough to sustain the technology of copying. Like the replicons' borders, the boundaries of other strategic assemblages are not fixed either - it all has to do with the broad net cast by strategies of replication in a world where self and other are very much at stake.

The integrated multi-cellular organism is a phenomenon which has emerged as a result of natural selection on primitively selfish replicators. It has paid replicators to behave gregariously [so much for 'harmony', in the short run]. The phenotypic power by which they ensure their survival is in principle extended and unbounded. In practice the organism has arisen as a partially bounded local concentration, a shared knot of replicator power. (Dawkins, 1982, p. 264)

'In principle extended and unbounded' - this is a remarkable statement of interconnectedness, but of a very particular kind, one that leads to theorizing the living world as one vast arms race. '[P]henotypes that extend outside the body do not have to be inanimate artefacts: they themselves can be built of living tissue ... I shall show that it is logically sensible to regard parasite genes as having phenotypic expression in host bodies and behaviour' (1982, p. 210, emphasis mine). But the being who serves as another's phenotype is itself populated by propagules with their own replicative ends. '[A]n animal will not necessarily submit passively to being manipulated, and an evolutionary "arms race" is expected to develop' (1982, p. 39). This is an arms race that must take account of the stage of the development of the means of bodily production and the costs of maintaining it:

The many-celled body is a machine for the production of single-celled propagules. Large bodies, like elephants, are best seen as heavy plant and machinery, a temporary resource drain, invested so as to improve later propagule production. In a sense the germ-line would 'like' to reduce capital investment in heavy machinery ... (1982, p. 254)

Large capital is indeed a drain; small is beautiful. But you and I have required large capital investments, in more than genetic terms. Perhaps we should keep an eye on the germ-line, especially since 'we' - the non-germline components of adult mammals (unless you identify with your haploid gametes and their contents, and some do) - cannot be copy units. 'We' can only aim for a defended self, not copy fidelity, the property of other sorts of units. Within 'us' is the most threatening other - the propagules, whose phenotype we, temporarily, are.

What does all this have to do with the discourse of immunology as a map of systems of 'difference' in late capitalism? Let me attempt to convey the flavour of representations of the curious bodily object called the human immune system, culled from textbooks and research reports published in the 1980s. The IS is composed of about 10 to the 12th cells, two orders of magnitude more cells than the nervous system has. These cells are regenerated throughout life from pluripotent stem cells that themselves remain undifferentiated. From embryonic life through adulthood, the immune system is sited in several relatively amorphous tissues and organs, including the thymus, bone marrow, spleen, and lymph nodes; but a large fraction of its cells are in the blood and lymph circulatory systems and in body fluids and spaces. There are two major cell lineages to the system. The first is the lymphocytes, which include the several types of T cells (helper, suppressor, killer, and variations of all these) and the B cells (each type of which can produce only one sort of the vast array of potential circulating antibodies). T and B cells have particular specificities capable of recognizing almost any molecular array of the right size that can ever exist, no matter how clever industrial chemistry gets. This specificity is enabled by a baroque somatic mutation mechanism, clonal selection, and a polygenic receptor or marker system. The second immune cell lineage is the mononuclear phagocyte system, including the multi-talented macrophages, which, in addition to their other recognition skills and connections, also appear to share receptors and some hormonal peptide products with neural cells. Besides the cellular compartment, the immune system comprises a vast array of circulating acellular products, such as antibodies, lymphokines, and complement components. These molecules mediate communication among components of the immune system, but also between the immune system and the nervous and endocrine systems, thus linking the body's multiple control and co-ordination sites and functions. The genetics of the immune system cells, with their high rates of somatic mutation and gene product splicings and rearrangings to make finished surface receptors and antibodies, makes a mockery of the notion of a constant genome even within 'one' body. The hierarchical body of old has given way to a network-body of truly amazing complexity and specificity. The immune system is everywhere and nowhere. Its specificities are indefinite if not infinite, and they arise randomly; yet these extraordinary variations are the critical means of maintaining individual bodily coherence.

In the early 1970s, the Nobel Prize-winning immunologist, Niels Jerne, proposed a theory of immune system self-regulation, called the network theory, that must complete this minimalist account (Jerne, 1985; Golub, 1987, pp. 379-92). 'The network theory differs from other immunological thinking because it endows the immune system with the ability to regulate itself using only itself' (Golub, 1987, p. 379). Jerne's basic idea was that any antibody molecule must be able to act functionally as both antibody to some antigen and as antigen for the production of an antibody to itself, albeit at another region of 'itself'. All these sites have acquired a nomenclature sufficiently daunting to keep popular understanding of the theory at bay indefinitely, but the basic conception is simple. The concatenation of internal recognitions and responses would go on indefinitely, in a series of interior mirrorings of sites on immunoglobulin molecules, such that the immune system would always be in a state of dynamic internal responding. It would never be passive, 'at rest', awaiting an activating stimulus from a hostile outside. In a sense, there could be no exterior antigenic structure, no 'invader', that the immune system had not already 'seen' and mirrored internally. 'Self' and 'other' lose their rationalistic oppositional quality and become subtle plays of partially mirrored readings and responses. The notion of the internal image is the key to the theory, and it entails the premise that every member of the immune system is capable of interacting with every other member. As with Dawkins's extended phenotype, a radical conception of connection emerges unexpectedly at the heart of postmodern moves.

This is a unique idea, which if correct means that all possible reactions that the immune system can carry out with epitopes in the world outside of the animal are already accounted for in the internal system of paratopes and idiotopes already present inside the animal. (Golub, 1987, pp. 382-3)

Jerne's conception recalls Winograd and Flores' insistence on structural coupling and structure-determined systems in their approach to perception. The internal, structured activity of the system is the crucial issue, not formal representations of the 'outer' world within the 'inner' world of the communications system that is the organism. Both Jerne's and Winograd's formulations resist the means of conceptualization facilitated most readily by a rationalist theory of recognition or representation. In discussing what he called the deep structure and generative grammar of the immune system, Jerne argued that 'an identical structure can appear on many structures in many contexts and be reacted to by the reader or by the immune system' (quoted in Golub, 1987, p. 384).9

Does the immune system - the fluid, dispersed, networking techno-organic-textual-mythic system that ties together the more stodgy and localized centres of the body through its acts of recognition - represent the ultimate sign of altruistic evolution towards wholeness, in the form of the means of co-ordination of a coherent biological self? In a word, no, at least not in Leo Buss's (1987) persuasive postmodern theoretic scheme of The Evolution of Individuality.

Constituting a kind of technological holism, the earliest cybernetic communications systems theoretic approaches to the biological body from the late 1940s through the 1960s privileged co-ordination, effected by 'circular causal feedback mechanisms'. In the 1950s, biological bodies became technological communications systems, but they were not quite fully reconstituted as sites of 'difference' in its postmodern sense - the play of signifiers and replicators in a strategic field whose significance depended problematically, at best, on a world outside itself. Even the first synthetic proclamations of sociobiology, particularly E.O. Wilson's Sociobiology; The New Synthesis (1975), maintained a fundamentally techno-organicist or holist ontology of the cybernetic organism, or cyborg, repositioned in evolutionary theory by post-Second World War extensions and revisions of the principle of natural selection. This 'conservative' dimension of Wilson and of several other sociobiologists has been roundly criticized by evolutionary theorists who have gone much further in denaturing the co-ordinating principles of organismic biology at every level of biotic organization, from gene fragments through ecosystems. The sociobiological theory of inclusive fitness maintained a kind of envelope around the organism and its kin, but that envelope has been opened repeatedly in late 1970s' and 1980s' evolutionary theory.

Dawkins (1976, 1982) has been among the most radical disrupters of cyborg biological holism, and in that sense he is most deeply informed by a postmodern consciousness, in which the logic of the permeability among the textual, the technic, and the biotic and of the deep theorization of all possible texts and bodies as strategic assemblages has made the notions of 'organism' or 'individual' extremely problematic. He ignores the mythic, but it pervades his texts. 'Organism' and 'individual' have not disappeared; rather, they have been fully denaturalized. That is, they are ontologically contingent constructs from the point of view of the biologist, not just in the loose ravings of a cultural critic or feminist historian of science.

Leo Buss reinterpreted two important remaining processes or objects that had continued to resist such denaturing: (1) embryonic development, the very process of the construction of an individual; and (2) immune system interactions, the iconic means for maintaining the integrity of the one in the face of the many. His basic argument for the immune system is that it is made up of several variant cell lineages, each engaged in its own replicative 'ends'. The contending cell lineages serve somatic function because

the receptors that ensure delivery of growth-enhancing mitogens also compel somatic function. The cytotoxic T-cell recognizes its target with the same receptor arrangement used by the macrophage to activate that cell lineage. It is compelled to attack the infected cell by the same receptor required for it to obtain mitogens from helper cells ... The immune system works by exploiting the inherent propensity of cells to further their own rate of replication. (Buss, 1987, p. 87)

The individual is a constrained accident, not the highest fruit of earth history's labours. In metazoan organisms, at least two units of selection, cellular and individual, pertain; and their 'harmony' is highly contingent. The parts are not for the whole. There is no part/whole relation at all, in any sense Aristotle would recognize. Pathology results from a conflict of interests between the cellular and organismic units of selection. Buss has thereby recast the multi-cellular organism's means of self-recognition, of the maintenance of 'wholes', from an illustration of the priority of co-ordination in biology's and medicine's ontology to a chief witness for the irreducible vulnerability, multiplicity, and contingency of every construct of individuality.

The potential meanings of such a move for conceptualizations of pathology and therapeutics within Western biomedicine are, to say the least, intriguing. Is there a way to turn the discourse suggested by Jerne, Dawkins, and Buss into an oppositional/alternative/liberatory approach analogous to that of Winograd and Flores in cognition and computer research? Is this postmodern body, this construct of always vulnerable and contingent individuality, necessarily an automated Star Wars battlefield in the now extra-terrestrial space of the late twentieth-century Western scientific body's intimate interior? What might we learn about this question by attending to the many contemporary representations of the immune system, in visualization practices, self-help doctrines, biologists' metaphors, discussions of immune system diseases, and science fiction? This is a large enquiry, and in the paragraphs that follow I only begin to sketch a few of the sometimes promising but more often profoundly disturbing recent cultural productions of the postmodern immune system-mediated body.10 At this stage, the analysis can only serve to sharpen, not to answer, the question.

This chapter opened with a reminder that science has been a travel discourse, intimately implicated in the other great colonizing and liberatory readings and writings so basic to modern constitutions and dissolutions of the marked bodies of race, sex, and class. The colonizing and the liberatory, and the constituting and the dissolving, are related as internal images. So I continue this tour through the science museum of immunology's cultures with the 'land, ho!' effect described by my colleague, James Clifford, as we waited in our university chancellor's office for a meeting in 1986. The chancellor's office walls featured beautiful colour-enhanced photographic portraits of the outer planets of earth's solar system. Each 'photograph' created the effect for the viewer of having been there. It seemed some other observer must have been there, with a perceptual system like ours and a good camera; somehow it must have been possible to see the land masses of Jupiter and Saturn coming into view of the great ships of Voyager as they crossed the empty reaches of space. Twentieth-century people are used to the idea that all photographs are constructs in some sense, and that the appearance that a photograph gives of being a 'message without a code', that is, what is pictured being simply there, is an effect of many layers of history, including prominently, technology (Barthes, 1982; Haraway, 1984-5; Petchesky, 1987). But die photographs of the outer planets up the ante on this issue by orders of magnitude. The wonderful pictures have gone through processes of construction that make the metaphor of the 'eye of the camera' completely misleading. The chancellor's snapshot of Jupiter is a postmodern photographic portrait - a denatured construct of the first order, which has the effect of utter naturalistic realism. Someone was there. Land, ho! But that someone was a spaceship that sent back digitalized signals to a whole world of transformers and imagers on a distant place called 'earth', where art photographs could be produced to give a reassuring sense of the thereness of Jupiter, and, not incidentally, of spacemen, or at least virtual spacemen, whose eyes would see in the same colour spectrum as an earthly primate's.

The same analysis must accompany any viewing of the wonderful photographs and other imaging precipitates of the components of the immune system. The cover of Immunology: A Synthesis (Golub, 1987) features an iconic replication of its tide's allusion to synthesis: a multi-coloured computer graphic of the three-dimensional structure of insulin showing its antigenic determinants clustered in particular regions. Golub elicits consciousness of the constructed quality of such images in his credit: 'Image created by John A. Tainer and Elizabeth D. Getzoff'. Indeed, the conventional trope of scientist as artist runs throughout Golub's text, such that scientific construction takes on the particular resonances of high art and genius, more than of critical theories of productions of the postmodern body. But the publications of Lennart Nilsson's photographs, in the coffee table art book The Body Victorious (Nilsson, 1987) and in the National Geographic (Jaret, 1986), allow the 'land, ho!' effect unmediated scope (Plates 9 and 10). The blasted scenes, sumptuous textures, evocative colours, and ET monsters of the immune landscape are simply there, inside us. A white extruding tendril of a pseudopodinous macrophage ensnares a bacterium; the hillocks of chromosomes lie flattened on a blue-hued moonscape of some other planet; an infected cell buds myriads of deadly virus particles into the reaches of inner space where more cells will be victimized; the autoimmune-disease-ravaged head of a femur glows in a kind of sunset on a non-living world; cancer cells are surrounded by the lethal mobil squads of killer T cells that throw chemical poisons into the self's malignant traitor cells.

The equation of Outer Space and Inner Space, and of their conjoined discourses of extra-terrestrialism, ultimate frontiers, and high technology war, is quite literal in the official history celebrating 100 years of the National Geographic Society (Bryan, 1987). The chapter that recounts the National Geographic's coverage of the Mercury, Gemini, Apollo, and Mariner voyages is called 'Space' and introduced with the epigraph, 'The Choice Is the Universe - or Nothing'. The final chapter, full of Nilsson's and other biomedical images, is entitled 'Inner Space' and introduced with the epigraph, 'The Stuff of the Stars Has Come Alive' (Bryan, 1987, pp. 454, 352). It is photography that convinces the viewer of the fraternal relation of inner and outer space. But curiously, in outer space, we see spacemen fitted into explorer craft or floating about as individuated cosmic foetuses, while in the supposed earthy space of our own interiors, we see non-humanoid strangers who are supposed to be the means by which our bodies sustain our integrity and individuality, indeed our humanity in the face of a world of others. We seem invaded not just by the threatening 'non-selves' that the immune system guards against, but more fundamentally by our own strange parts. No wonder auto-immune disease carries such awful significance, marked from the first suspicion of its existence in 1901 by Morgenroth and Ehrlich's term, horror autotoxicus.

The trope of space invaders evokes a particular question about directionality of travel: in which direction is there an invasion? From space to earth? From outside to inside? The reverse? Are boundaries defended symmetrically? Is inner/outer a hierarchicalized opposition? Expansionist Western medical discourse in colonizing contexts has been obsessed with the notion of contagion and hostile penetration of the healthy body, as well as of terrorism and mutiny from within. This approach to disease involved a stunning reversal: the colonized was perceived as the invader. In the face of the disease genocides accompanying European 'penetration' of the globe, the 'coloured' body of the colonized was constructed as the dark source of infection, pollution, disorder, and so on, that threatened to overwhelm white manhood (cities, civilization, the family, the white personal body) with its decadent emanations. In establishing the game parks of Africa, European law turned indigenous human inhabitants of the 'nature reserves' into poachers, invaders in their own terrain, or into part of the wildlife. The residue of the history of colonial tropical medicine and natural history in late twentiety-century immune discourse should not be underestimated. Discourses on parasitic diseases and AIDS provide a surfeit of examples.

The tones of colonial discourse are also audible in the opening paragraphs of Immunology: The Science of Non-Self Discrimination, where the dangers to individuality are almost lasciviously recounted. The first danger is 'fusion of individuals':

In a jungle or at the bottom of the sea, organisms - especially plants, but also all kinds of sessile animals - are often in such close proximity that they are in constant danger of losing their individuality by fusion ... But only in the imagination of an artist does all-out fusion occur; in reality, organisms keep pretty much separate, no matter how near to one another they live and grow. (Klein, 1982, p. 3)

In those exotic, allotropic places, any manner of contact might occur to threaten proper mammalian self-definition. Harmony of the organism, that favourite theme of biologists, is explained in terms of the aggressive defence of individuality; and Klein advocates devoting as much time in the undergraduate biology curriculum to defence as to genetics and evolution. It reads a bit like the defence department fighting the social services budget for federal funds. Immunology for Klein is 'intraorganismic defense reaction', proceding by 'recognition, processing, and response'. Klein defines 'self as 'everything constituting an integral part of a given individual' (1982, p. 5; emphasis in original). What counts as an individual, then, is the nub of the matter. Everything else is 'not-self and elicits a defence reaction if boundaries are crossed. But this chapter has repeatedly tried to make problematic just what does count as self, within the discourses of biology and medicine, much less in the postmodern world at large.

A diagram of the 'Evolution of Recognition Systems' in a recent immunology textbook makes clear the intersection of the themes of literally 'wonderful' diversity, escalating complexity, the self as a defended stronghold, and extra-terrestrialism (Plate 11). Under a diagram culminating in the evolution of the mammals, represented without comment by a mouse and a fully-suited spaceman,11 who appears to be stepping out, perhaps on the surface of the moon, is this explanation:

From the humble amoeba searching for food (top left) to the mammal with its sophisticated humoral and cellular immune mechanisms (bottom right), the process of 'self versus non-self recognition' shows a steady development, keeping pace with the increasing need of animals to maintain their integrity in a hostile environment. The decision at which point 'immunity' appeared is thus a purely semantic one'. (Playfair, 1984, p. 3; emphasis in original)

These are the semantics of defence and invasion. When is a self enough of a self that its boundaries become central to entire institutionalized discourses in medicine, war, and business? Immunity and invulnerability are intersecting concepts, a matter of consequence in a nuclear culture unable to accommodate the experience of death and finitude within available liberal discourse on the collective and personal individual. Life is a window of vulnerability. It seems a mistake to close it. The perfection of the fully defended, 'victorious' self is a chilling fantasy, linking phagocytotic amoeba and moon-voyaging man cannibalizing the earth in an evolutionary teleology of post-apocalypse extra-terrestrialism. It is a chilling fantasy, whether located in the abstract spaces of national discourse, or in the equally abstract spaces of our interior bodies.

Images of the immune system as battlefield abound in science sections of daily newspapers and in popular magazines, for example, Time magazine's 1984 graphic for the AIDS virus's 'invasion' of the cell-as-factory. The virus is imaged as a tank, and the viruses ready for export from the expropriated cells are lined up as tanks ready to continue their advance on the body as a productive force. The National Geographic explicitly punned on Star Wars in its graphic entitled 'Cell Wars' in Jaret's 'The Wars Within' (1986, pp. 708-9). The battle imagery is conventional, not unique to a nuclear and Cold War era, but it has taken on all the specific markings of those particular historical crises. The militarized, automated factory is a favourite convention among immune system illustrators and photographic processors. The specific historical markings of a Star Wars-maintained individuality12 are enabled in large measure by high-technology visualization technologies, which are also critical to the material means of conducting postmodern war, science, and business, such as computer-aided graphics, artificial intelligence software, and many kinds of scanning systems.

'Imaging' or 'visualization' has also become part of therapeutic practice in both self-help and clinical settings, and here the contradictory possibilities and potent ambiguities over biomedical technology, body, self, and other emerge poignantly. The immune system has become a lucrative terrain of self-development practices, a scene where contending forms of power are evoked and practised. In Dr. Berger's Immune Power Diet, the 'invincible you' is urged to 'put immune power to work for you' by using your 'IQ (Immune Quotient)' (Berger, 1985, p. 186). In the great tradition of evangelical preaching, the reader is asked if'You are ready to make the immune power commitment?' (1985, p. 4). In visualization self-help, the sufferer learns in a state of deep relaxation to image the processes of disease and healing, in order both to gain more control in many senses and to engage in a kind of meditation on the meanings of living and dying from an embodied vantage point in the microplaces of the postmodern body. These visualization exercises need not be prototypes for Star Wars, but they often are in the advice literature. The National Geographic endorses this approach in its description of one such effort: 'Combining fun and therapy, a young cancer patient at the M. D. Anderson Hospital in Houston, Texas, zaps cancer cells in the "Killer T Cell" video game' (Jaret, 1987, p. 705). Other researchers have designed protocols to determine if aggressive imagery is effective in mediating the healing work of visualization therapies, or if the relaxation techniques and non-aggressive imagery would 'work'. As with any function, 'work' for what cannot remain unexamined, and not just in terms of the statistics of cancer survival. Imaging is one of the vectors in the 'epidemics of signification' spreading in the cultures of postmodern therapeutics. What is at stake is the kind of collective and personal selves that will be constructed in this organic-technical-mythic-textual semiosis. As cyborgs in this field of meanings, how can 'we', late-twentieth-century Westerners, image our vulnerability as a window on to life?

Immunity can also be conceived in terms of shared specificities; of the semi-permeable self able to engage with others (human and non-human, inner and outer), but always with finite consequences; of situated possibilities and impossibilities of individuation and identification; and of partial fusions and dangers. The problematic multiplicities of postmodern selves, so potently figured and repressed in the lumpy discourses of immunology, must be brought into other emerging Western and multi-cultural discourses on health, sickness, individuality, humanity, and death.

The science fictions of the black American writer, Octavia Butler, invite both sobering and hopeful reflections on this large cultural project. Drawing on the resources of black and women's histories and liberatory movements, Butler has been consumed with an interrogation into the boundaries of what counts as human and into the limits of the concept and practices of claiming 'property in the self' as the ground of'human' individuality and selfhood. In Clay's Ark (1984) Butler explores the consequences of an extra-terrestrial disease invading earth in the bodies of returned spacemen. The invaders have become an intimate part of all the cells of the infected bodies, changing human beings at the level of their most basic selves. The invaders have a single imperative that they enforce on their hosts: replication. Indeed, Clay's Ark reads like The Extended Phenotype] the invaders seem disturbingly like the 'ultimate' unit of selection that haunts the biopolitical imaginations of postmodern evolutionary theorists and economic planners. The humans in Butler's profoundly dystopic story struggle to maintain their own areas of choice and self-definition in the face of the disease they have become. Part of their task is to craft a transformed relation to the 'other' within themselves and to the children born to infected parents. The offsprings' quadruped form arehetypically marks them as the Beast itself, but they are also the future of what it will mean to be human. The disease will be global. The task of the multi-racial women and men of Clay's Ark comes to be to reinvent the dialectics of self and other within the emerging epidemics of signification signalled by extra-terrestrialism in inner and outer space. Success is not judged in this book; only the naming of the task is broached.

In Dawn, the first novel of Butler's series on Xenogenesis, the themes of global holocaust and the threateningly intimate other as self emerge again. Butler's is a fiction predicated on the natural status of adoption and the unnatural violence of kin. Buder explores the interdigitations of human, machine, non-human animal or alien, and their mutants, especially in relation to the intimacies of bodily exchange and mental communication. Her fiction in the opening novel of Xenogenesis is about the monstrous fear and hope that the child will not, after all, be like the parent. There is never one parent. Monsters share more than the word's root with the verb 'to demonstrate'; monsters signify. Buder's fiction is about resistance to the imperative to recreate the sacred image of the same (Buder, 1978). Buder is like 'Doris Lessing, Marge Piercy, Joanna Russ, Ursula LeGuin, Margaret Atwood, and Christa Wolf, [for whom] reinscribing the narrative of catastrophe engages them in the invention of an alternate fictional world in which the other (gender, race, species) is no longer subordinated to the same' (Brewer, 1987, p. 46).

Catastrophe, survival, and metamorphosis are Butler's constant themes. From the perspective of an ontology based on mutation, metamorphosis, and the diaspora, restoring an original sacred image can be a bad joke. Origins are precisely that to which Butler's people do not have access. But patterns are another matter. At the end of Dawn, Buder has Lilith - whose name recalls her original unfaithful double, the repudiated wife of Adam pregnant with the child of five progenitors, who come from two species, at least three genders, two sexes, and an indeterminate number of races. Preoccupied with marked bodies, Buder writes not of Cain or Ham, but of Lilith, the woman of colour whose confrontations with the terms of selfhood, survival, and reproduction in the face of repeated ultimate catastrophe presage an ironic salvation history, with a salutary twist on the promise of a woman who will crush the head of the serpent. Buder's salvation history is not Utopian, but remains deeply furrowed by the contradictions and questions of power within all communication. Therefore, her narrative has the possibility of figuring something other than the Second Coming of the sacred image. Some other order of difference might be possible in Xenogenesis - and in immunology.

In the story, Lilith Iyapo is a young American black woman rescued with a motley assortment of remnants of humanity from an earth in the grip of nuclear war. Like all the surviving humans, Lilith has lost everything. Her son and her second-generation Nigerian-American husband had died in an accident before the war. She had gone back to school, vaguely thinking she might become an anthropologist. But nuclear catastrophe, even more radically and comprehensively than the slave trade and history's other great genocides, ripped all rational and natural connections with past and future from her and everyone else. Except for intermittent periods of questioning, the human remnant is kept in suspended animation for 250 years by the Oankali, the alien species that originally believed humanity was intent on committing suicide and so would be far too dangerous to try to save. Without human sensory organs, the Oankali are primatoid Medusa figures, their heads and bodies covered with multi-talented tentacles like a terran marine invertebrate's. These humanoid serpent people speak to the woman and urge her to touch them in an intimacy that would lead humanity to a monstrous metamorphosis. Multiply stripped, Lilith fights for survival, agency, and choice on the shifting boundaries that shape the possibility of meaning.

The Oankali do not rescue human beings only to return them unchanged to a restored earth. Their own origins lost to them through an infinitely long series of mergings and exchanges reaching deep into time and space, the Oankali are gene traders. Their essence is embodied commerce, conversation, communication - with a vengeance. Their nature is always to be midwife to themselves as other. Their bodies themselves are immune and genetic technologies, driven to exchange, replication, dangerous intimacy across the boundaries of self and other, and the power of images. Not unlike us. But unlike us, the hydra-headed Oankali do not build non-living technologies to mediate their self-formations and reformations. Rather, they are complexly webbed into a universe of living machines, all of which are partners in their apparatus of bodily production, including the ship on which the action of Dawn takes place. But deracinated captive fragments of humanity packed into the body of the aliens' ship inescapably evoke the terrible Middle Passage of the Adantic slave trade that brought Lilith's ancestors to a 'New World'. There also the terms of survival were premised on an unfree 'gene trade' that permanently altered meanings of self and other for all the 'partners' in the exchange. In Butler's science fictional 'middle passage' the resting humans sleep in tamed carnivorous plant-like pods, while the Oankali do what they can to heal the ruined earth. Much is lost for ever, but the fragile layer of life able to sustain other life is restored, making earth ready for recolonization by large animals. The Oankali are intensely interested in humans as potential exchange partners partly because humans are built from such beautiful and dangerous genetic structures. The Oankali believe humans to be fatally, but reparably, flawed by their genetic nature as simultaneously intelligent and hierarchical. Instead, the aliens live in the postmodern geometries of vast webs and networks, in which the nodal points of individuals are still intensely important. These webs are hardly innocent of power and violence; hierarchy is not power's only shape - for aliens or humans. The Oankali make 'prints' of all their refugees, and they can print out replicas of the humans from these mental-organic-technical images. The replicas allow a great deal of gene trading. The Oankali are also fascinated with Lilith's 'talent' for cancer, which killed several of her relatives, but which in Oankali 'hands' would become a technology for regeneration and metamorphoses. But the Oankali want more from humanity; they want a full trade, which will require the intimacies of sexual mingling and embodied pregnancy in a shared colonial venture in, of all places, the Amazon valley. Human individuality will be challenged by more than the Oankali communication technology that translates other beings into themselves as signs, images, and memories. Pregnancy raises the tricky question of consent, property in the self, and the humans' love of themselves as the sacred image, the sign of the same. The Oankali intend to return to earth as trading partners with humanity's remnants. In difference is the irretrievable loss of the illusion of the one.

Lilith is chosen to train and lead the first party of awakened humans. She will be a kind of midwife/mother for these radically atomized peoples' emergence from their cocoons. Their task will be to form a community. But first Lilith is paired in an Oankali family with the just pre-metamorphic youngster, Nikanj, an ooloi. She is to learn from Nikanj, who alters her mind and body subtly so that she can live more freely among the Oankali; and she is to protect it during its metamorphosis, from which they both emerge deeply bonded to each other. Endowed with a second pair of arms, an adult ooloi is the third gender of the Oankali, a neuter beeing who uses its special appendages to mediate and engineer the gene trading of the species and of each family. Each child among the Oankali has a male and female parent, usually sister and brother to each other, and an ooloi from another group, race, or moitié. One translation in Oankali languages for ooloi is 'treasured strangers'. The ooloi will be the mediators among the four other parents of the planned cross-species children. Heterosexuality remains unquestioned, if more complexly mediated. The different social subjects, the different genders that could emerge from another embodiment of resistance to compulsory heterosexual reproductive politics, do not inhabit this Dawn.

The treasured strangers can give intense pleasure across the boundaries of group, sex, gender, and species. It is a fatal pleasure that marks Lilith for the other awakened humans, even though she has not yet consented to a pregnancy. Faced with her bodily and mental alterations and her bonding with Nikanj, the other humans do not trust that she is still human, whether or not she bears a human-alien child. Neither does Lilith. Worrying that she is none the less a Judas-goat, she undertakes to train the humans with the intention that they will survive and run as soon as they return to earth, keeping their humanity as people before them kept theirs. In the training period, each female human pairs with a male human, and then each pair, willing or not, is adopted by an adult ooloi. Lilith loses her Chinese-American lover, Joseph, who is murdered by the suspicious and enraged humans. At the end, the first group of humans, estranged from their ooloi and hoping to escape, are ready to leave for earth. Whether they can still be fertile without their ooloi is doubtful. Perhaps it is more than the individual of a sexually reproducing species who always has more than one parent; the species too might require multiple mediation of its replicative biopolitics. Lilith finds she must remain behind to train another group, her return to earth indefinitely deferred. But Nikanj has made her pregnant with Joseph's sperm and the genes of its own mates. Lilith has not consented, and the first book of Xenogenesis leaves her with the ooloi's uncomprehending comfort that 'The differences will be hidden until metamorphosis' (Butler, 1987, p. 263). Lilith remains unreconciled: 'But they won't be human. That's what matters. You can't understand, but that is what matters.' The treasured stranger responds, 'The child inside you matters' (p. 263). Buder does not resolve this dilemma. The contending shapes of sameness and difference in any possible future are at stake in the unfinished narrative of traffic across the specific cultural, biotechnical, and political boundaries that separate and link animal, human, and machine in a contemporary global world where survival is at stake. Finally, this is the contested world where, with or without our consent, we are located. '[Lilith] laughed bitterly, "I suppose I could think of this as fieldwork - but how the hell do I get out of the field?"' (1987, p. 91).

From this field of differences, replete with the promises and terrors of cyborg embodiments and situated knowledges, there is no exit. Anthropologists of possible selves, we are technicians of realizable futures. Science is culture.