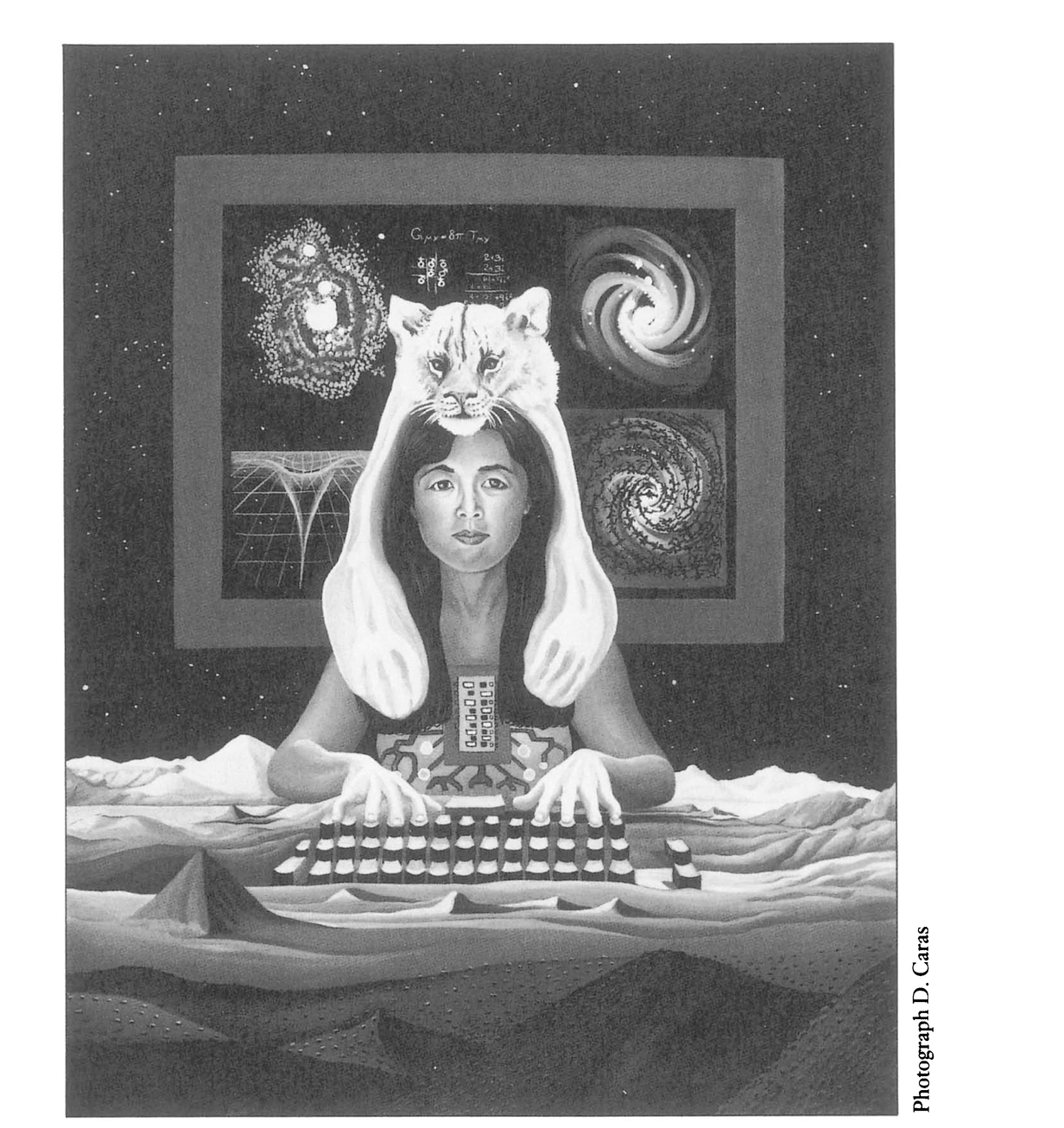

Plate 1 Cyborg, 1989, oil on canvas, 36" X 28"by Lynn Randolph ©

For these things passed as arguments

With the anthropoidal apes.

Charlotte Perkins Gilman, 'Similar Cases'

Language is not innocent in our primate order. Indeed, it is said that language is the tool of human self-construction, that which cuts us off from the garden of mute and dumb animals and leads us to name things, to force meanings, to create oppositions, and so craft human culture. Even those who dismiss such radical talk must acknowledge that major reforms of public life and public knowledge are coupled with projects for the purification of language. In the history of science, the fathers of things have been first of all fathers of words - or so the story is told to students of the discipline. Aristotle named beings and thereby constructed the rules of logic; Bacon denounced Aristotle in a project for the reform of language so as to permit, at last, true knowledge. Bacon also needed a new logic appropriate to his correct names. Linnaeus legitimated the kinship of human beings with animals in 1758 in the order he named, Primates. Linnaeus's taxonomy was a logic, a tool, a scheme for ordering the relations of things through their names. Linnaeus may have known himself as the eye of God, the second Adam who built science, trustworthy knowledge, by announcing at last the correct names for things.1 And even in our time, when such giants and fathers are dead, scientific debate is a contest for the language to announce what will count as public knowledge. Scientific debate about monkeys, apes, and human beings, that is, about primates, is a social process of producing stories, important stories that constitute public meanings. Science is our myth. This chapter is a story about part of that myth, in particular aspects of recent efforts to document the lives of Asian leaf-eating monkeys called langurs.

This chapter is not innocent; it is an interested story searching for clues about how to ask feminist questions concerning public scientific meanings in an area of the life sciences so crucial to tales about human nature and human possibility. Feminism is, in part, a project for the reconstruction of public life and public meanings; feminism is therefore a search for new stories, and so for a language which names a new vision of possibilities and limits. That is, feminism, like science, is a myth, a contest for public knowledge. Can feminists and scientists contest together for stories about primates, without reducing both political meanings and scientific meanings to babble?

I would like to explore the writings of four primatologists linked together in a particular social network in physical anthropology, primatologists who are also all Euro-American women, in order to probe some aspects of these issues. In particular, does the practice of their science by these women in a field of modern biology-anthropology substantially structure discourse in ways intriguing to feminists? Should we expect anything different from women than from men? What are the right questions to ask about the place of sex and gender in the social structuring of scientific meanings in the areas of scientific work under investigation: animal behaviour and evolutionary theory? What questions seem most unhelpful? We will return to look at these questions after following the careers of some of our primate kin, US white primatologists and langurs.

Why look through the window of words and stories? Isn't the essence of a science elsewhere, perhaps in the construction of testable propositions about nature? But what can count as an object of study? What is a biological object? Why do these objects change so radically historically? Such debates are complicated; here I would only like to establish the fruitfulness of paying close attention to stories in biology and anthropology, to the common structures of myths and scientific stories and political theories, in such a way as to take all these forms seriously. Stories are a core aspect of the constitution of an object of scientific knowledge. I do not wish to reduce natural scientific practice to political practice, or the reverse, but to watch the weaving of multi-layered meanings in the social working out of what may count as explanation in an area of biology-anthropology where sex and gender seem to matter a great deal.

The student of the history of primatology is immediately confronted with a rich tapestry of images and stories. For a person formed by a Judaeo-Christian mythological inheritance, the extraordinary persistence of the Genesis story in scientific reconstructions of human evolution demands attention, and not just in the flourish of popular presentations. Equally prominent are secular origin stories.2 The history of the relations of science and religion is represented on the primate stage, for example, in the contest in the early twentieth century for medical rather than moral definitions of sexual behaviour, using animal models (Yerkes, 1943). One of the first book-length treatments of the organization of wild primate societies can only be understood in the line of Thomas Hobbes and the social Leviathan (Zuckerman, 1932). Stories of the origin of the family, of language, of technology, of co-operation and sharing, and of social domination all demand sensitivity to echoes of significance embedded in available metaphor and in the rules for telling meaningful stories in particular historical conditions. It is impossible not to suspect that multi-levelled stories are at the core of things when, without ever necessarily speaking about human primates, contemporary primatologists must speak seriously about harems, dual-career mothering, social signalling as a cybernetic communication control system, troop takeovers and infanticide, rapid social change, time-energy budgets, reproductive strategies and genetic investments, conflicts of interest and cost-benefit analyses, nature and frequency of orgasm in non-human animal females, female sexual choice, male overlords and leadership, social roles, and division of labour.3

But why explore the weaving of multiple meanings in the practice of primatology by looking at the obscure Asian leaf-eating monkeys, the langurs?4 Langurs are a major group of monkeys, familiar to primatologists, but virtually unknown until very recently to a wider public which would not fail to recognize a gorilla, a rare mammal indeed. Surely the apes, especially chimpanzees, and cercopithecines, especially baboons and rhesus monkeys, have most often and most importantly been at the centre of debates about human evolution, legitimate and illegitimate ways of arguing an animal model for any human dimension, the nature and significance of primate social organization, and the impact of gender on the social construction of facts and theories (Fedigan, 1982)? Perhaps this was true, until the question of infanticide emerged at the centre of the debate about langur social life and evolution (Ford, 1976). Why and when do langur males kill langur babies? What should these acts be called? What should the rules be for reliable observation of such acts? Do they really occur? What shall have the social status of fact and of scientific explanation? These are the questions internal to a little corner of primatology which provoked the focus of this chapter. Why and how did these questions come to be crucial to technical discourse by the late 1970s? A response to that question will lead us back to an exploration of scientific practice as the social production of important public stories.

First, however, let us remember that evolutionary biology in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries is part of the public debate about the human place in nature - that is, about the nature of politics and society. Primate social behaviour is studied inescapably as part of the complex struggle in liberal Western democracies to name who is a mature, healthy citizen and why. Argument about human politics from a state of nature is a hoary tradition in Western political discourse; its modern form is the interweaving of stories in natural and political economy, in biology, and in social sciences. Further, I want to argue that primate stories, popular and scientific, echo and rest on the material social processes of production and reproduction of human life. In particular, primate bioanthropology from the 1920s has figured prominently in contests in ideology and practice for who will control the human means of reproduction, as well as in contests over the causes and controls of human war, and struggles over technical ingenuity and co-operative capacities in family and factory. These generalizations, I believe, are true whether or not particular primate scientists intend their work to be part of such struggles; their stories are part of the public resource in the contests. And primatologists tell stories remarkably appropriate to their times, places, genders, races, classes - as well as to their animals.

A series of quick illustrations must suffice for the longer argument, if we are to get on to the missing, maybe murdered, langur babies and to the Euro-American women who watch monkeys professionally. During the 1920s, in the hands of psychobiologists, comparative psychologists, and reproductive and neural physiologists, primates in laboratories figured prominently in debates about human mental function and sexual organization. Marriage counselling, immigration policy, and the testing industry all are directly indebted to primates and primatologists, who in Robert Yerkes' words were 'servants of science'. Primates seemed models of natural co-operation unobscured by language and culture. During the 1930s, in early field work on wild primates, the sexual physiology of natural cooperation (in the forms of dominance of males over females and of troop demographic structure) emerged in arguments about human social therapeutics for social disorder - like labour strikes and divorce. Primate models of nuclear families and of fathering in the suburbs, as well as of the doleful results of absent mothers, appeared in public debates about US social problems throughout the 1950s and 1960s. Primate models for human depression have been avidly sought, and a great deal of technical ingenuity has gone into reliably producing psychoses in monkeys. Population policy and questions about population regulation drew on primate studies, as did psychiatry (even proposed telemetric control) of stressed, perhaps black male human primates in riotous cities in the 1960s. The pressing question of 'man's' naturally co-operative or warlike nature was argued in symposia and classrooms throughout the Vietnam war, with constant debts to developing new theories of human evolution based on recent fossils from South and East Africa, new field studies of living primates, and the anthropology of modern gatherer-hunters. Primatologists could be found on most sides of most debates, including the 'side' of not wanting to be part of any explicit political attitude. From the point of view of practising primatologists, perhaps the most pressing direct political questions involve the rapid destruction of non-human primates all over their range. But that worry quickly embroils the most apolitical scientist in international politics profoundly determined by the history of imperialism.

It should surprise no one that langur bioanthropology began to interest a wide US public in the 1970s and 1980s, when questions about domestic violence (specifically beaten women and children); reproductive freedom (or often coercion); abortion; parenting (a euphemism for mothering and an ambivalent look at fathering); and 'autonomous' women who are not primarily defined in terms of a social (that is, family) group are prominent. Is mothering itself 'selfish'? One cannot but be struck by the plethora of feminist and anti-feminist, biological and homiletic, subtle and blatant publishing on human and non-human mothering and on female reproductive strategies. It is not easy to disentangle the technical and popular threads in the langur story in this context, and that disentanglement is in any case a certain ideological move in the interests of saving the purity of science. Perhaps for the moment it is more intriguing, even more responsible, to leave the weaving tangled and try to sort out the principal arguments about infanticide among the sacred Hanuman monkeys of India.

It is appropriate in biology to begin with descent, with modification, and in anthropology with the social object of kinship; so let us approach the subjects of this chapter through the fiction of a patriline - that of a very visible father in the primate order, Sherwood Washburn. All the women whose work will be examined (Phyllis Jay [later, Dolhinow], Suzanne Ripley, Sarah Blaffer Hrdy, and Jane Bogess) are academic 'daughters' or granddaughters in an important network of primatologists in the United States after the Second World War. It is directly through the Washburn lineage that the langur students of this story inherited core elements of their Active strategies, their allowable stories, and their tools with which to craft the outlines of a different story. Primatology has been a collective historical production, not the offspring of an omnipotent father. But the analyses, entrepreneurial activities, and institutional power of Washburn have grafted primate science as a branch of physical anthropology on to roots of modern neo-Darwinian evolutionary theory and structural-functional social anthropology. The rules of these root sciences must be sketched to follow the debates about langur babies.

All the women discussed in this paper have experienced multiple influences on their work; the fiction of a patriline should connote neither unique influence nor necessary harmony. In fact, families should be expected to be scenes of intense conflict. But the patriline, and language of daughters and sons, does connote both public identification of people as present or former students of a prominent figure and common discussion of academic 'begats' among biologists and anthropologists. The language itself is charged with questions of independence and indebtedness, of individual achievement and ascribed identities. Part of women's struggle against patriarchy has been to insist on being named independently of fathers. My use of family language is intended to suggest problems and tensions, as well as to note an ambivalent starting point in present scientific social relations historically ordered by male-dominant hierarchies. I think there is little question that Washburn's professional power has had profound effects for his female and male students. Like any family name, the academic patronymic is a social fiction. The language of a patriline does not tell the natural history of an academic family; it names a lineage of struggles, mutual concerns, and inheritance of tools and public social identities.

The chief intellectual legacy of the patriline of Washburn's physical anthropology was the imperative to reconstruct not fixed structures, but ways of life - to turn fossils into the underpinnings of living animals and to interpret living primates in carefully rule-bound ways as models for aspects of human ways of life. Adaptation, function, and action were the real scientific objects, not frozen structures or hierarchical, natural scales of perfection or complexity. By developing functional comparative anatomy as part of the synthetic theory of evolution and extending the approach to the social behaviour of living primates, Washburn and his students integrated genetic selection theory and disciplined field and experimental methodology into the practice of evolutionary reconstruction.

The best-known product of practice in the Washburn patriline was the 'man-the-hunter' hypothesis of the 1960s. This hypothesis suggested that the crucial evolutionary adaptations making possible a human way of life in the hominid line in its likely ecological setting were those associated with a new food-getting strategy, a subsistence innovation carrying the implications of a human future based on social co-operation, learned technical skill, nuclear families, and eventually fully symbolic language. It is important to stress from the beginning that the fundamental elements of the man-the-hunter hypothesis guiding much of primate field study for well over a decade were co-operation and the social group as the principal adaptations. Phenomena such as aggression, competition, and dominance structures were seen primarily as mechanisms of social co-operation, as axes of ordered group life, as prerequisites of organization. And of course, the man-the-hunter hypothesis was pre-eminently about male ways of life as the motors of the human past and future. Hunting was a male innovation and speciality, the story insisted. And what was not hunting had always been. Hunting was the principle of change; the rest was a base line or a support system.5

So Washburn's daughters entered the field as part of a complex social family of life scientists practising at the disputed boundaries of biology and anthropology, arguing about the meanings of long-disputed objects of knowledge called primates, and constructing origin and action stories about disputed visions of past constraint and future possibility. Field and laboratory studies of living primates developed exponentially from modest pre-war levels nearly simultaneously and internationally after the Second World War for complex reasons, such as polio research, new fossil hominid finds in Africa, Japanese development of longitudinal studies of primate societies as part of comparative anthropology, and searches for animal model systems for human emotional disorders and social disorganization within a cybernetic control model of social management. But these reasons take us beyond the concerns of this essay. Washburn was one of perhaps a dozen key actors in developments rooted in large historical determinations like war, new technologies for international travel and tropical disease control, modern medical research institutionalization, and international conservation organization in decolonialized but contested neo-imperialist world orders.6

Washburn earned his doctorate in physical anthropology at Harvard in 1940. His training reflected the medical heritage and colonial racist social basis of physical anthropology and primatology. Schooled in traditional anthropomorphic methods and primate anatomy, he taught medical anatomy at Columbia College of Physicians and Surgeons until 1947, when he moved to the University of Chicago, where he worked with his first important graduate students in social behaviour (as opposed to strict functional comparative anatomy), including Phyllis Jay. Washburn belonged to the generation of physical anthropologists who disavowed the practice of their science to construct racial hierarchies, a practice of comparative life science based on premises of increasing complexity and perfection in evolution with implicit and explicit teleological standards of white, male, professional, bourgeois social organization. Washburn actively contested to move physical anthropology away from part of this heritage, primarily by crafting rules for telling evolutionary stories that did not easily yield racist meanings.7 He did not see or challenge similar scientific frameworks for knowing and for producing hierarchically ordered gender - not because of personal ill-will, but because world struggles challenging racism were ending colonialism and making visible many of its rules for generating public knowledge, including the life sciences. The women's movement of the 1970s made different scientific constructions of gender possible, not the insight of genius in the heads of either men or women. But specific women and men did produce transformed debates about sex and gender in scientific contests grounded in changed social possibility. These primate scientists had no more of a direct relationship to various feminisms and other dimensions of revolutionized social relations of women and men than Washburn did to African, Asian, and United States liberation struggles. But neither did Washburn and his academic children have direct relations to the social lives of baboons and langurs. The mediations of public stories are multiple. However, we are moving ahead of our story and asserting what must be told.

By the mid-1940s Washburn was practising physical anthropology as an experimental science; by 1950 he was developing a powerful programme for reinterpreting the basic concepts and methods of his field in harmony with the recent population genetics, systematics, and palaeontology of Theodosius Dobzhansky, Ernst Mayr, and George Gaylord Simpson. By 1958 he had a Ford Foundation grant to study the evolution of human behaviour from multiple points of view, including initial provision for field studies of baboons in East Africa. This work was done in collaboration with his student, Irven DeVore; it grounds the first development of the baboon comparative model for interpreting hominid evolution from the viewpoint of man-the-hunter. In a subsequent National Science Foundation grant proposal ('Analysis of Primate Behavior', 1961), DeVore and Washburn were principal investigators, although the grant supported others' work as well. Acknowledging differences from baboon data and interpretations, the final report to the foundation paid considerable attention to Jay's langur investigations. Those early grant proposals cited the relevance of the baboon social behaviour studies to human psychology and psychiatry. Psychiatrist David Hamburg from NIH and comparative psychologist Harry Harlow from the University of Wisconsin were among the consultants named in the proposals. In 1959, at Berkeley, Washburn developed funding for one of the first primate field stations in the United States. From the beginning of his career, he lectured, wrote popular texts, made pedagogical films, reformed curricula on all educational levels, and helped determine the careers of prominent figures in evolution and primatology.8

I am including in the Washburn patriline primate behaviour and evolution students at the Universities of Chicago and California who earned their PhDs after about 1958. Included also are many students of students and people who earned degrees elsewhere. For example, Jane Bogess (1976) was the doctoral student of Phyllis Jay/Dolhinow (1963), who earned her doctorate with Washburn; and Sarah Blaffer Hrdy (1975) was the PhD student of Irven DeVore (1962) of Harvard, who earned his degree with Washburn. One should not expect harmony in a family; and, indeed, we will see the emergence of major debates among the Washburn siblings, as well as major deviations from the father's stories. DeVore and Washburn have been in conflict from the late 1970s over sociobiology; Jay/Dolhinow and Bogess share positions in opposition to Ripley and Hrdy. All of these oppositions centre on reproductive strategies and their meanings. We will also see a field of common discourse and transformations of inherited stories which have the result of centring debates about sex and gender in ways not possible before the 1970s.

A preliminary survey of the direct (Universities of Chicago and California, Berkeley) Washburn lineage shows at least 40 doctoral students, of whom about 15 are active professional women. These figures should be placed in the context of very rough preliminary statistics for primatology as a whole. There are three major professional associations to which primate behaviour and evolution scientists belong: (1) The International Primatological Society (founded 1966) has a membership of about 750, of whom 380 are from the United States, and 120 (16 per cent) of whom are women. Judged by professional address, about 130 IPS members consider themselves anthropologists; only 17 per cent of these are women. (2) The American Society of Primatologists (founded 1977) has a membership of about 445, of whom 23 are foreign, mostly Canadian. About 30 per cent, or 131, are women, and about 16 per cent (70) of the membership have an address in an anthropological institutional division. (No specialty, not even medicine [16 per cent] or psychology [13 per cent], has a larger representation.) There are about 30 women anthropologists (45 per cent of members who are anthropologists) listed in the ASP, 7 of whom are originally PhDs from the University of California at Berkeley. The Washburn lineage is remembered by several of its members from its beginning to have included atypically large numbers, for the profession, of women graduate students. It is certainly true that prominent women in primate debates are in the Washburn lineage, but these statistics indicate that by 1980 women generally practised primatology in the United States within the specialty of anthropology in large numbers compared to the total international figures and compared to other primate-related specialties in the United States. (3) The American Association of Physical Anthropology has a membership of about 1,200, about 26 per cent of whom are women. None of these figures gives an accurate sense of how many people study primate behaviour and evolution, as opposed to many other aspects of primatology, and deciding the specialty of a practitioner is often fairly arbitrary: where does anthropology end and comparative psychology begin? Moreover, addresses are sometimes ambiguous. But even these rough figures indicate the collective and international nature of primate studies, the significant participation of women in the field, especially in the United States, and the visible presence of members of the Washburn lineage.9

What are the social mechanisms for passing on rules for telling stories? How did the Washburn lineage work in giving the daughters of man-the-hunter tools for modifying their inheritance in the scientific construction of sex and gender as both objects and conditions of study? We have already glanced at the logical skeleton of evolutionary stories told by Washburn. The principal rule was to weave stories about function and action, about ways of life. It remains to glance equally quickly at what might be called his 'plan' for establishing authoritative stories about primates. The main element in the 'plan' was making space for his students to speak, initially covered by his substantial social authority, but ultimately with their own professional bases. Another principal component in Washburn's training was insistence on what was in 1960 an unusual structure of course and field-lab work for physical anthropology. Washburn students, whatever their final concentration, ideally studied functional comparative anatomy, social-cultural theory in social anthropology, and field investigations of living primates. Some students did not actually study all three elements, but the ideal was stressed in Washburn grant proposals and other descriptions of his projects for the reform of physical anthropology. Fossils, modern hunter-gatherers, and living primates were all necessary to Washburn's programme that produced the synthetic man-the-hunter hypothesis guiding research and informing explanatory stories. His students were equipped for leadership roles in an emerging discipline. This was a father who knew how to ground an inheritance materially.

nashburn's primatology patriline may be said to have been born with the 1957-58 University of Chicago seminar 'Origins of Human Behaviour'. Members of this group, including Phyllis Jay and Irven DeVore, became formative figures in evolving primate field studies; and the knowledge of the Japanese language of another participant, the Jesuit, John Frisch, permitted a fuller initial conception of the contemporary work of Japanese colleagues.

Washburn students were not members of a particularly authoritarian laboratory; they chose their own topics. They also opposed Washburn in several ways and worked independently of his ideas and support. But several report the sense in retrospect that the intellectual excitement of a new synthesis in physical anthropology and Washburn's nurturance of students' choices and opportunities (as well as indifference to other choices) suggest the existence of a more explicit plan. For example, since functional anatomy appropriate to a hunting way of life was an essential part of the story, it should not be surprising to find students in the 1960s working out new anatomical adaptational complexes made visible by the man-the-hunter hypothesis. Different students could be found studying the hand, vertebral on. column, foot, communication, range and diet, maternal behaviour, and so

Two special sessions in the 1960s at the American Anthropological Association (AAA) meetings were typical of the social mechanisms which Washburn made available to his students and associates and which grounded the man-the-hunter hypothesis firmly in the discipline. In 1963, an all-day symposium featured fifteen Washburn students, six of them women. Adrienne Zihlman spoke on range and behaviour; she would do her doctorate on bipedalism within the framework of the hunting hypothesis. Later she would be a central figure in challenging this explanatory framework and in proposing a major synthetic alternative. Her colleague for part of this task, Nancy Tanner (died 1989), was a social anthropologist who worked as a teaching assistant for Washburn while she was a graduate student. Judith Shirek spoke on diet and behaviour; her PhD concerned visual communication in a macaque species. Phyllis Jay spoke on dominance in 1963; her doctorate treated langur monkey social organization. Suzanne Chevalier gave a paper on mother-infant behaviour; her later research brought questions and methods from Masters and Johnson into consideration of non-human primate female orgasm, within the context of the widespread challenge to notions of the primary importance of male sexual activity. Suzanne Ripley communicated results from her study of maternal behaviour in langurs, the species at the heart of her dissertation and later work. Jane Lancaster spoke about primate annual reproductive cycles, an early presentation of what became a major new point of view for studying primate reproduction outside the laboratory. Her dissertation was on primate communication; her later work would be an important part of the daughters' revolt against the man-the-hunter synthesis. Washburn's male graduate students similarly spoke on aspects of the hunting hypothesis in its three-part plot of anatomy, primate behaviour, and social anthropology. The 1966 AAA session was called 'Design for Man'; all the components of the male-centred hunting story were then in place, including approaches to psychological and emotional adaptational complexes, within the context of the ideology of stress proposed within modern psychiatry.

Washburn summarized the talks of the session in a brief, pointed talk on 'The Hunting Way of Life'.10 The lessons for the discipline of physical anthropology would have been hard to miss. And whatever meanings individual students attached to their own work at the time of their graduate training, it seems very likely that in the 1960s the public meanings of presentations from the University of California, Berkeley, framed by Washburn's interpretations - and sometimes more active direction included: (1) the primacy of the baboon model for a comparative functional understanding of hominid evolution; (2) the crucial role of the social group (and a much lesser role of sexual bonds) as the key behavioural adaptation of primates; and (3) the central drama of a male subsistence innovation -hunting - in the human origin story, which included bipedalism, tools, language, and social co-operation. Again, male dominance hierarchies were a key mechanism of this promising co-operation.

It should be clear that the daughters of the Washburn patriline were raised to speak in public, to have authority, to author stories. They also often got teaching jobs which permitted time for research and publication. A lengthy story deserves to be told about these primate students, their brothers, and their tribe (troop?). But here let us turn to only one set of stories authored by man-the-hunter's daughters in the field, the langur saga.11 In looking more closely at part of just one complex tale, perhaps we can clarify how stories with public meanings change within the life sciences.

One conclusion of this idiosyncratic exegesis should be announced in advance: the langur story with all its multiple public meanings is not a mechanical reflection of ideology and social forces outside physical anthropology-primatology; nor is it the product of diligent objective science ever improving its own methods of finally seeing nothing but Ur-monkeys. The natural sciences are neither so tame nor so mystifying. Both these points of view caricature the production of science as myth, that is, as meaning-laden public knowledge. But both poles of the caricature contain a suggestion of what I find to be true and what makes the process of crafting science interesting to a person who wonders how new kinds of stories can be given birth. Natural scientific stories are supposed to be fruitful; they regularly lead people who practise science to see things they did not know about before, to find the unexpected. Scientific stories have an intriguing rule of construction: in spite of the best precautions, they force an observer to see what one cannot expect and probably does not want to see. The tools to craft this vision are quite material, even mundane. For example, primatologists over decades have developed and progressively enforced on each other quite explicit criteria for collecting data worthy of respect: number of hours in the field, physical position of observer, ability to recognize animals, inter-observer similarity in naming and counting 'units' of behaviour, form of data sheets and storage of data, sampling procedures to counter observer preferences to watch what is already interesting, and so on. Washburn's patriline provided the children with tools to force provocative vision in a historical environment which structured the possibility of different stories. The chief problem with arguing this position from the point of view of social forces determining scientific stories from the 'outside' versus painstaking scientific practice clearing out bias from the 'inside' is that inside and outside are the wrong metaphors. Social forces and daily scientific practice both exist inside. Both are part of the process of producing public knowledge, and neither is a source of purity or pollution. Indeed, daily scientific practice is a very important social force. But such practice can only make visble what people can historically learn to see. All stories are multiply mediated (Latour and Woolgar, 1979).

A cautionary word is necessary: no attempt is made in this chapter to describe, much less explain, the whole career, publication record, or historical influences for Dolhinow, Ripley, Hrdy, or Bogess. Particular moments in the history of modern primatology and particular papers come into focus here in order to highlight public debates about female human nature and about parenting and violence. These debates raise political-historical questions about scientific origin stories and lead to contests for naming meanings and possibilities, in the context of current US struggles to define and judge human female and male co-operation and competition, domestic violence, abortion and political reproductive freedoms and constraints, social pathology and stress, and sociobiological arguments about inherited tendencies in human social behaviour, including sex roles. These concerns are traditional in the history of evolutionary biology and physical anthropology. Primates are privileged objects in specific historical contests to name the unmarked human place in nature, as well as to describe the equally unmarked nature of human society.

Phyllis Jay, today Phyllis Dolhinow, a full professor in the University of California, Berkeley's Department of Anthropology and dissertation adviser to another of the daughters of this story, Jane Bogess, was one of Washburn's first graduate students to study social behaviour and a member of the Chicago seminar on the origins of human behaviour. She conducted observations on langur monkeys (Presbytis entellus) in central and north India for 850 hours over 18 months in 1958-60, work that formed the core of her dissertation, 'The social behavior of the langur monkey' (1963a), and several other publications (Jay, 1962, 1963b, 1965; Dolhinow, 1972). Jay was the first post-Second World War systematic observer of these monkeys in the field; her study was followed quickly by those of a team of observers from the Japan Monkey Center with Indian colleagues, working in south India from 1961 to 1963, and of her fellow Washburn graduate student, Suzanne Ripley, who completed a one-year study in 1963 of grey langurs in Ceylon. Jay's story was complex; but I should like to isolate a few elements for closer analysis: the question of how to establish a model for an aspect of ways of life of early hominids, the structure of argument about the organized social group as an evolutionary adaptation, the criteria for establishing social behaviour as pathological or healthy, the shifting of positions of phenomena within an observer's field of vision and the strategy for explanation of these shifts, and the transformation of meanings of stories when such shifts occur. The focus here will be on Phyllis Jay's early publications, based on field study done as a graduate student in the first years of re-awakened, post-Second World War interest in naturalistic primate behaviour. In many ways primatology was structurally different in the early 1960s from what it was around 1980, when Hrdy and Bogess did their first field work and publishing. The size of related literatures, standardization of field procedure, dynamics of career social networks and professional possibilities, and relations to other debates in biology (for example, within ecology and population biology) and anthropology (for example, about sociobiology applied to human groups) have all changed. A thesis of this chapter is that some of these changes have been a function of, and have in turn contributed to, major political struggles over the social relations of human reproduction and over the political place of all primate females in nature.

At the same time that Jay was in the field watching langurs, her fellow graduate student was watching baboons in Africa. Washburn and Irven DeVore conducted a 12-month, 1,200-hour study of baboons in Kenya in 1959, following up a 200-hour preliminary study conducted by Washburn in 1955, as an almost accidental opportunity at a pan-African conference on human evolution. The baboon field work explored the power of a scientific model for certain aspects of reconstructed hominid behavioural adaptational complexes, postulated to be associated with savannah living and the hunting innovation. Modelling in the Washburn school did not mean searching for a simpler version of a supposedly more complex human behaviour, much less searching for a species considered as a whole to be a simpler version of hominids. Scales of complexity were not objects of knowledge here. Other primate species could be models for quite specific aspects of adaptational complexes, such as range or diet or correlation of intensity of dominance hierarchies with predation pressure. Such models, like any other biological model systems, should be subject to observation and experimental manipulation in field and laboratory. Logically, primate model systems had the same status as in vitro or even totally synthetic cell membrane subsystems in studying cell movement. Baboons seemed like promising models in the study of human evolution because they were ground-living primates dependent on a structured social group for survival. Behaviour, ecology, functional anatomy - all had to be correlated in any explanatory story. Models could be illuminating as contrasts as well as comparisons; model building was part of construction of a comparative evolutionary science. Indeed, Washburn and DeVore (1961) concluded that the differences between baboons and hominids were most significant. But there was an explicit centre to all the comparisons: Homo sapiens. In its beginning, the Washburn school did not pose the questions of zoologists, but of students of the human way of life. And baboons emerged early as privileged model systems determining meanings for other species studied by Washburn students, for example, vervet monkeys and langurs. Baboons seemed the correct model system for discussions of male-male co-operation, male dominance hierarchies as a form of adaptive social organization, and male indispensability in troop defence for a savannah-living potential hominid.

Did this baboon centre structure the meanings of Jay's story about langurs? Jay's early papers are replete with references to DeVore's story about baboons, a story with a strong plot turning on the life of males, especially in their supposed role as troop protectors, internal peace-keepers, and organizers through the mechanism of their dominance hierarchy. DeVore literally saw a male-centred baboon troop structure, containing a core of allied dominant males immensely attractive to females and children, with other males on the periphery when the troop was stationary or following behind as special guards when the troop seemed threatened by danger. This tableau proved hard for anyone else to see physically, but symbolically it has been repeated in multiple variations, including textbook illustrations.12 If male dominance were the mechanism of troop organization, then variations in male dominance should be the object of attention to generate comparative stories. An implicit corollary was that degrees of social organization were correlated to fullness of development of that key adaptational mechanism for life in a social group, stable male hierarchies, the germ of co-operation. The logical link to medical-psychiatric therapeutics of social groups should be clear: social disorder implies a breakdown of central adaptational mechanisms. Stressed males would engage in inappropriate (excessive or deficient) dominance behaviours - at the expense of troop organization and even survival.

Both DeVore and Jay saw the organized social group as the basic adaptive unit of the species. This was not necessarily a group selectionist claim, and this issue was hardly raised until sociobiological challenges to (or extensions of?) neo-Darwinian selection theory emerged in the 1970s. Social roles were basic objects of study because they structured groups. Social bonds maintained troop unity, and male dominance relations were hardly the only kind of social bond for either observer. But in DeVore's explanations, they were the bonds that ultimately made a group possible; and groups made primates possible, as well as the human way of life, the pre-eminent object of knowledge in the Washburn patriline. Note that the important level of explanation is mechanisms and adaptational complexes. Jay's early papers showed a series of fascinating oppositions to this story structure, because her langurs failed to act like good baboons, but still had very stable groups.

The bulk of Jay's papers on overall langur life was about infants and mothers. Her approach to social organization was longitudinal and developmental, in contrast to DeVore's topical plot with dominant adult male central actors on a savannah stage set for hominid possibilities. I read Jay's early work as substantively more biologically and ecologically complex and multi-centred than DeVore's. Jay published separate papers on infants and mothers as well. In spite of their frequent publications on the theme, some female former graduate students recall trying to avoid too much identification with the topic of females and infants - too much attention to females pollutes the observer, labels the observer as peripheral. In any case, Jay was repeatedly requested to write papers on that subject for early collected volumes on primates. Again, whatever her sense of the overall biology of langurs, she was publicly associated with a story not named as the comparative centre for hominid innovation. Baboons were the privileged model system; and that meant, in the hands of DeVore, male activity. Although DeVore knew infants were centres of attraction, and all observers recorded infant socialization in describing the genesis of group structure, the explanation of a group could not rest on the activity of mothers and infants. Jay explicitly saw the infant as a key centre of attraction in langur troop structure; but that subplot was not a major component of her story conclusions. She described the passage of infants among females, relative male lack of interest in infants, sex differences in infant development, the lack of well-defined dominance hierarchies among adult females, temporary alliances of adult females in conflict with other females (no female-female organizations were seen as stable or primary by Westerners until well after 1960, and matrilines continued to be about ranks of sons for even longer), low incidences of aggression in the troops, and generally looser troop organization than DeVore's baboons had. She argued that the mother-infant relationship was the most intense of a langur's life, maintaining as well that all dominance structures were exceedingly complex and subtle and not very important in daily existence. In short, she literally, physically saw what almost could not figure in her major conclusions because another story ordered what counted as ultimate explanation. Washburn's physical anthropology of man-the-hunter required comparative primate social behaviour studies, but the not-so-silent centre of comparison lived on the African savannah and yawned a dominant threat at other story structures and conclusions. All comparisons are not equal when the scientific goal is to know 'man's' place in nature.

When possible, Jay conducted her observations physically from within the troop; she acted like a troop subordinate, averting her eyes from direct glances to avoid any provocation. Although most langur troops Jay watched could not be observed from within because, for example, they were high in trees overhead, Jay's only explicit methodological comment in her early papers about her own physical relation as an observer named herself explicitly within the troop, and neither dominant nor intervening to provoke the animals' dominance among themselves. In contrast, DeVore watched from the periphery, protected by a landrover, partly because of the presence of lions in the region; daily life therefore looked different. DeVore also experimentally provoked the male-male dominance interactions that had to be seen to signify central meanings, called observations. Jay, on the other hand, spent much less space describing male activities than those of females and infants and had a hard time specifying exactly what males did that mattered in daily troop life. However, she explicitly concluded, 'Adult males maintain internal troop stability by establishing and asserting a stable male dominance hierarchy that structures the relationships of adult males within the troop' (Dolhinow, 1972, p. 230). Males were leaders who co-ordinated troop unity and stability, despite the observation structure of her papers. It was the generation of Washburn daughters after Jay who turned the constant observations of matrifocal groups into an explanation of troop structure and into privileged models for hominid evolution.13

Although females and infants were very visible to Jay, she did not see something which other observers elsewhere began to report in dramatic terms: males killing infants after they moved into a troop, ousting the previous resident male or males. For example, Yukimaru Sugiyama from the Laboratory of Physical Anthropology at Kyoto University, and part of the team from the Japan Monkey Center that studied langurs at Dharwar from 1961 to 1963, told a story of animals for whom, 'Apart from the fact that one large adult male leads the troop, there is no other evident social differentiation.' He observed what he called 'social change' in troops, including 'reconstruction' through successful attack of a bisexual troop by an all-male group. Subsequently, all but one of the usurping males were ousted. In the next two months the remaining male apparently bit a juvenile female and all five troop infants, none of whom survived. But it seems Sugiyama did not see the male killing the infants. The same observer also experimentally provoked troop social change by removing the sole male (called 'the dominant male overlord who had protected and led the troop') in another bisexual group. Ultimately a male entering this troop killed four infants; these events appear to have been witnessed directly. In these studies the important experimental manipulations of troops, that is, of model systems for studying social organization, were always of high-status males, presumed points of organic vitality and 'social change'.14

It was not that Jay could not record such a drastic event; none occurred during her study or in her region of India. But she did comment on others' observations of infant deaths in noting the extraordinary variability of habitat and behaviour characteristic of langurs and the need for more study correlating ecology and social behaviour. It is here that the criteria for deciding the significance of male troop takeover and infanticide began to be enunciated. For Jay, such 'rapid social change' occurred in the context of a high population density of langurs, which produced stress that in turn yielded social pathology. The infanticide did not explain anything. In any case, these events occupied the periphery of a stage set to represent the success of social groups as primate adaptations. That stage was necessary to man-the-hunter as harbinger of human, male-based co-operation expressed through healthy dominance relations. Jay noted the observations of infanticide, but her story did not alter because of them.

Let us now turn to a major effort to wreck that stage in the confrontation of sociobiological explanation with the rules for meaning that had given birth to the Washburn line. Then we will return to the question of key event in explanatory stories versus accidental occurrence or social pathology. For Sarah Blaffer Hrdy the social group emphasis seemed to obscure, ironically, female equality - equality in reproductive strategies, that is. But reproductive strategies lie close to the heart of contests for political meanings in the 1970s and 1980s, including full human female citizenship in the United States based on reproductive autonomy, 'ownership of one's own body'. Reproductive strategies concern the body's investments. Remember that at least since Thomas Hobbes and seventeenth-century debates in England about sovereignty, citizenship, and suffrage, property in the self - the right and ability to dispose of one's investment, one's incorporation - was argued to ground legitimate political action, particularly the formation of civil society in contrast to a supposedly natural reproductive family. The sociobiological logic of feminism we are about to glance at draws from the theoretical wellsprings of Western political democracy. Pollution of the waters does not date from E. O. Wilson's sociobiological publications on human nature. Biology's logic of reproductive competition is merely one common, early form of argument in our inherited capitalist political economy and political theory. Biology has intrinsically been a branch of political discourse, not a compendium of objective truth. Further, simply noting such a connection between biological and political/economic discourse is not a good argument for dismissing such biological argument as bad science or mere ideology. It should not be surprising that the contest over langur infanticide touches raw political and scientific nerves.

In Sarah Blaffer Hrdy's version of langur life, infanticide and male troop takeovers became the key to the meaning of langur social behaviour. And Hrdy's (1977) work was heralded with meanings Jay/Dolhinow never claimed: the dust jacket to her Harvard University Pressbook announces 'The Langurs of Abu (subtitle: Female and Male Strategies of Reproduction) is the first book to analyze behavior of wild primates from the standpoint of both sexes. It is also a poignant and sophisticated exploration of primate behavior patterns from a feminist point of view.' Hrdy, the former graduate student of Irven DeVore at Harvard, also worked closely with Robert Trivers and E.O. Wilson. These three men are fundamental sociobiological theorists. DeVore, in root opposition to Washburn, has reinterpreted the social anthropology of human hunter-gatherers in terms of the behavioural systems emerging from a genetic kinship calculus of interest. For Hrdy, the primate social group became one possible result of the strategies of individual reproducers to maximize their genetic fitness, to capitalize on their genetic investments. The social origin story of pure liberal, utilitarian political economy ruled; individual competition produced all the forms of combination of the efficient animal machine. Social life was a market where investments were made and tested in the only currency that counts: genetic increase.

Infanticide in certain circumstances became a rational reproductive strategy of langur males, opposed to a rational extent by langur females, whose reproductive interests were certainly not the same as the males'. Indeed, root sexual conflict from a sociobiological viewpoint is a necessary consequence of sexual reproduction. Any genetic difference introduces some degree of conflict, even if expressed in coalition. The pattern here is the reverse of seeing dominance hierarchies as mechanisms of co-ordination for the chief adaptational complex, the social group. Sociobiologists might still view dominance hierarchies as patterns co-ordinating a social group, but the basic logic is different. All biological structures are expressions of a genetic calculus of interest, that is, the best possible (not perfect) resolutions of fundamental conflict when all the elements in a system need each other for their own reproductive success. Note that the crucial level of explanation is not mechanism, function, or way of life, but pared-down fitness maximization strategy. Explanation is game theory. The dust jacket of Hrdy's book could call her use of this logic 'feminist' because she paid systematic attention to female activity in their reproductive interest and did not explain individual behaviour in terms of roles for co-ordinating elements for group survival. Where Jay/Dolhinow speaks of adaptation, Hrdy speaks of selection. It is only in a situation of direct controversy that all the differences in meaning of these two apparently harmonious evolutionary terms emerge.

Although Hrdy did not, probably, write her own dust jacket, it still frames her story for readers. She did, however, write her dedication and acknowledgements, both marvellous icons, or stories in miniature, suggesting public meanings that open a book replete with the language of heroic struggle and Odyssean voyages to preserve the products of genetic investment in dangerous times. The book, dedicated to her mother, opened with 'a catalogue of heroes'. Hrdy continued, 'I first learned of langurs accidentally, while satisfying a distribution requirement in one of Harvard's most popular undergraduate courses, primate behavior, starring Irven DeVore.' Her teaching assistant in that course was Trivers. Later, 'In the voyage that followed, Professors DeVore and Trivers, together with a synthesizing omnipotent, Edward O. Wilson, introduced me to a realm of theory that transformed my view of the social world.' The mundane nature of scientific socialization again shows clearly. After acknowledging langurs themselves, animals named after gods and heroes in Hindu and Roman mythology (Hanuman, the Hindu monkey god, and Entellus, a boxing champion in the Aeneid), Hrdy concluded, 'Anyone heroic enough to read on to the end of this book will learn why the identification of langurs with warriors was an appropriate taxonomic choice, and why the final salute must be to the prescience of the nineteenth-century British naturalists who first went out to study the Hanuman (1977, pp. v-x). A salute to the naturalist-imperialist ventures of Britain at the height of its bourgeois triumph, ideologized as a fruit of unrestrained capitalism, could not be more appropriate for the logic of the story that followed.

Hrdy's book is a sustained polemic against what she sees as group selection arguments and structural-functional social system theory. Dolhinow and her students are Hrdy's principal antagonists in a 'heroic' struggle for correct vision. The purpose, like the purpose of the stories in the orthodox Washburn lineage, is to illuminate the logic of the human way of life by telling scientific stories, thereby producing public meanings. As Hrdy put it:

Not surprisingly, when we first began to intensively study our closest non-human relatives, the monkeys and apes, an idealization of our own society was extended to theirs: thus, according to the first primatological reports, monkeys, like humans, maintain complex social systems geared towards ensuring the group's survival. It is this particular misconception about ourselves, and about primates, that lends the history of langur studies its significance. By revealing our misconceptions about other primates, the langur saga may unmask misconceptions about ourselves. (1977, p. 11)

In the language of command, control, war, adultery, property and investment strategies, and dramatic soap opera about power struggles, Hrdy tells a story that is fundamentally a political history of troops dominated by male combat and female and male conflicting reproductive calculations. She argues for the hypothesis that langur males have several possible reproductive strategies given the design constraints of a leaf-eating monkey body and their ecological niche possibilities. For a male outside a troop, one of those strategies is to invade and oust the resident male, kill his putative offspring, and provoke females into an earlier oestrus so that they will mate with the usurper as quickly as possible, before he too is deposed. His children must have the best chance to reach maturity; a few months' difference would matter if the frequency of troop takeovers (rapid social change?) is that calculated from Hrdy's and others' observations. Females clearly have an interest in preserving former genetic investments, but only to a point short of damage to their overall best possible reproductive chances. Females have counterstrategies for male patterns, as well as patterns of reproductive conflict of interest with each other - and with their own offspring. The point is that any explanatory bind in the story is undone by an appeal to profit calculations under conditions of the market (species biology and habitat). The degree to which these calculations are rooted in 'observations', or simply follow from the plot, is highly controversial - a point to which we will return in the discussion of the work of Dolhinow's student, Jane Bogess, which contains scathing critiques of Hrdy's self-styled soap opera. The rules of observation themselves are very much contested by the daughters of the Washburn lineage. But most of all, the stories are contested - which 'idealizations' about primate life, human and non-human, will have the status of scientific knowledge.15

But before looking at the responses to the deviant daughter within the direct (legitimate?) Washburn lineage, let us look at the langur story of Jay/ Dolhinow's near contemporary among graduate students at Berkeley, Suzanne Ripley. Ripley also enters in the contest for primate nature a candidate for a model for human possibility within inherited constraint. Her model turns on the logic of mechanisms for population regulation and calls on the language of women's contemporary struggles for reproductive rights, as well as the language of ecological stress and population catastrophes. Stress is a basic determinant of the story's plot. Stress has been a common theme in the Washburn lineage. It is linked to stories of past adaptation and the threat of present human obsolescence. And as Jay had published 'The Female Primate' in a book entitled The Potential of Women and Zihlman had published 'Motherhood in Transition' in a conference organized around human psychiatric and therapeutic concerns for the family, resulting in the book The First Child and Family Formation, Ripley published in a socially charged context in a very scientifically respectable setting: an interdisciplinary symposium on crowding, density dependence, and population regulation in 1978. The proceedings were published by Yale University Press.

Ripley's (1980) argument also contested for the logic of models for the human way of life; hers, like those of many Washburn daughters, centred on female activity. The problem she set herself was to look at human infanticide 'from the perspective of another primate species' (p. 350). She asked if widespread human infanticide is pathological or adaptive. Unlike Dolhinow, Bogess, and Hrdy, she did not here contest for what counts as an observation; she accepted the 'facts' of troop takeover and infanticide as established. She compared both human beings and langurs as foraging generalists with exceptionally wide ranges of habitat compared to the habitats of their near relatives with similar design constraints set by their respective basic biology (colobines and apes). How do langurs and humans survive as generalists within the parameters of their biology? Flexible social systems and learned behavioural plasticity turning on reproductive practices are the answer. Sex is at the centre of the explanation, hardly a novel aspect of explanation in life science. Sex is the principle of increase (vitality) in biological stories, and biology has been from its birth in the late eighteenth century a discourse about productive systems or, better, modes of production. Sex is also especially prone to stress and pathology. Finally, to connect reproduction and production has been the key theoretical desideratum of both natural and political economy for 200 years.

Ripley's story contends that generalists exploit marginal habitats all the time, avoiding specialization and its confining consequences. A cost of this life strategy is periodic population crashes, when marginality turns into disaster; a need then is for a reproductive-behavioural system that can re-establish populations quickly. That property entails the inevitability of periodic population excesses when conditions are easy. So in turn some feedback population regulation mechanism should be expected in successful species, and infanticide is a perfectly good candidate. Note the general cybernetic model of the animal machine; this aspect of models is typical of post-Second World War stories. Steam engines and telephone exchanges belong to an earlier era of biology.

The best feedback device should operate close to the steps tying reproductive and subsistence subsystems of species life strategies together. So for humans, female-controlled infanticide in gatherer-hunter groups would be an excellent mechanism for maintaining population regulation, that is, a close fit of subsistence opportunities and numbers. Ripley assumes the demotion of hunting and the requirement to consider female activity in hominid subsistence innovations. That she can so quietly assume this major change in stories in physical anthropology in 1980 is the result of work by others, many in the Washburn lineage, in the context of an 'external' women's movement.

In langurs, infanticide is male-controlled; but that is a minor point. Langurs also need some mechanism for ensuring outbreeding in the face of their rather closed troop structure. Male aggression and troop takeover habits in crowded conditions ensure just that good. Humans have evolved culture-kinship systems, so langurs are no model here for Ripley.

Although there is little fundamental disagreement, Ripley contests with Hrdy for the level of final biological explanation. For all the story-tellers in this paper, real explanation is evolutionary, a plot in which the past both constrains and enables the future and contains its germ of change, even progress. But for Ripley, infanticide is a mechanism, one possible, rather interesting enabling strategy for obligate generalists. Male langur reproductive strategies are proximate causes; final causes ('ultimate biological value') are retention of polymorphism of genotypes in populations for an ecological generalist within a social structure that otherwise produces inbreeding. Hrdy's final causes are strategies of least units of reproduction: genes or individuals. Ripley is not arguing for group selection, but for the genetic conditions of continued system persistence.

In her conclusions, Ripley focuses on questions of adaptation, pathology, stress, obsolescence, and the limits of models. Facing an analogous evolutionary dilemma, langurs and humans, though phylogenetically remote, are related in modelling a jointly experienced opposition of fundamental conditions for continued existence. Human population dilemmas are not new, from this point of view, but are an aspect of our basic evolutionary history for which people found a learned behavioural solution (female-regulated infanticide) in small-group societies. Modern humans, though, do introduce a troubling novelty. They have uncoupled decisions about reproduction and production. The ability to make decisions about future ecosystem-carrying capacity does not lie with reproducing units, and rapid feedback regulation could hardly be expected. What is a simple achievement in small-scale societies is nearly impossible in modern conditions. The threat of obsolescence in the face of such stresses suggests solutions: small is beautiful, and women should make decisions about productive and reproductive links in the human life system. Of course, biological value is not social value; but still Ripley concludes pregnantly:

It seems that the possibility of adaptive infanticide is an inevitable accompaniment of the status of an ecologically generalist species and is simply a price our species had to pay in the process of becoming, and remaining, human. It is the interplay of carrying capacity . . . and combinations of evolutionary strategies (generalist or specialist . . .) that determines the biological value of infanticide in both human and nonhuman primate species problems. (1980, pp. 383-4)

Here, medical appropriation of moral-political stories about human behaviour, which characterized arguments about sex in primatology earlier, yields pride of place to biological cost-benefit analysis. Economics and biology are logically one. Hrdy and Ripley are both well within the boundaries of their technical discourse in crafting these public stories. It is all a question of becoming and remaining human, a stressful problem.

Of course, Ripley and Hrdy may simply be wrong; at least that conclusion is argued in still another version of the langur story, that of Jane Bogess of the University of California, Berkeley. Bogess argues that Hrdy and others who advance the language of troop takeover and goal-directed infant-killing by males fundamentally have not fulfilled the necessary conditions for convincing their peers they know what they claim. Bogess works to establish that Hrdy and others extrapolated on the basis of the logic of their stories, and that the best observational foundations lead to different stories, those closely related to Dolhinow's original ones, but with greater explicit emphasis on the workings of natural selection. The core meaning of the Bogess tale is again social health and pathology (Bogess, 1979, 1980).

Bogess insists on naming putative troop 'takeover' as 'rapid' social change' (also Jay's terminology), to avoid the teleology of the sociobiological investment argument. She looks at males in troop structure in terms of the concept of 'male social instability' because of frequent changes in male troop membership. She does not remark on this intriguing transformation in language about males and the determinants of troop organization. She says easily, without comment, what twenty years ago no one saw or said. Bogess can even say such things without further comment in a paper totally about male behaviour. Female behaviour in 1980 is an implicit centre partly ruling the story's plot. Almost the opposite was true for Jay in 1960. What intervened was more than monkeys - and more than primatology. Bogess argues that changes in male troop membership usually occur in staggered introductions and exclusions, not dramatic takeovers. Moreover, infant-killing was in fact rarely directly observed; and even when it was, ascribed paternity important to the logic of Hrdy's sociobiological story is very doubtful. A second look at the reports suggests to Bogess that attacks may have been against the females of troops in stressed circumstances and, furthermore, may have been in keeping with a particular aspect of langur biology (low tolerance, especially by females, of strangers). Hrdy's takeovers and infanticide become, in the view of Bogess, 'sudden and complete replacement in adult male membership and attendant infant mortality' (1979, p. 88).

Stress was likely to be a human-mediated condition resulting from recent habitat disruption. Behaviour resulting from modern human impacts on habitat could hardly be given centre stage in the evolutionary story of langurs. Infant-killing would then be either the sign of social pathology resulting from the unnatural human element or an 'accident'. Bogess argues that there is precious little observational evidence for goal-directed infant-killing, and the logic of her story demotes the incidents she agrees were seen. Bogess is quite explicit about standards for calling specific social behaviour pathological, rather than calling it the key to genetic investment strategies. If the behaviours in question, infant-killing and uncontrolled male social instability, harm the reproductive success of both sexes, call them pathological, maladaptive.

In certain populations, where there is social crowding and artificially high densities and where adult males live outside bisexual troops, the species-typical characteristic male social instability can operate against the reproductive success of all troop members, including the new male residents. (Bogess, 1979, p. 104)

Bogess values explanation at the level of mechanisms; like Dolhinow she is committed to structural-functionalism and neo-Darwinian evolutionary theory. She is interested in the social system as a behavioural adaptation, and she focuses on environmental variables and range of flexibility in the social system.

nut Bogess does enter the argument about genetic fitness maximization strategies; such an argument is required in contemporary evolutionary discourse. She is within the received logics of this argument in focusing on inter-male dominance competition as the primary male strategy for maximizing male reproductive success, but not for troop organization itself. She carefully documents exactly what she means by male dominance competition. Rates and forms of competition are here contested more than the logic of explanation. But perhaps the most fundamental challenge of Bogess's paper to other langur students is from her standards of field work and dissection of what can count as data. She has inherited and crafted high standards for pursuing her stories.

I cannot tell a story about who is weaving the best langur tales, though I have my favourites. I have neither the scientific authority to name the facts, nor is that my purpose in this chapter. On the other hand, I am certainly not arguing that the women whose work I have squeezed for my meanings have been unscientific in modelling human life or have imported in some illegitimate way the pollutions of women's interests into scientific discourse. Nor have they purified science by importing women's 'natural' insights. I do find some intriguing meanings for feminist reflection in this tale of the transformation of stories, meanings that bear on the nature of feminist responsibility for crafting science as public myth in the present and future. It is my opinion that forbidding comparative stories about people and animals would impoverish public discourse, assuming any individual or group could enforce such draconian restrictions on stories people tell about themselves and other beings in Western traditions. But no class of these stories can be seen as innocent, free of determination by historically specific social relations and daily practice in producing and reproducing daily life. Surely scientific stories are not innocent in that sense. It is equally true that no class of tales can be free of rules for narrating a proper story within a particular genre, in this case the discourse of life science. Demystifying those rules seems important to me. Nature is constructed, constituted historically, not discovered naked in a fossil bed or a tropical forest. Nature is contested, and women have enthusiastically entered the fray. Some women have the social authority to author scientific stories.

That fact is fairly new. Before the Second World War, indeed before the birth of the daughters of the Washburn patriline, women did not directly contest for primate nature; men did. That point mattered, as even a sceptical glance at the work of the leaders in primatology (for example, Robert Yerkes or Solly Zuckerman) will show. Many primatologists, including women, claim gender does not materially determine the contents of natural science; if it does, the result is called poor science. I think the evidence supports a different interpretation. At the least, gender is an unavoidable condition of observation. So also are class, race, and nation.

It is also new to look at a group of women constituting the major authoritative contestants in a publicly important debate. There are several men who study langurs, but with a little qualification, exclusive focus on Euro-American women does not leave out the generative centres of debate about the species. I do not think these white women are the major figures in langur sagas merely because langurs appeal to their nature somehow. White women exist in primatology in substantial numbers; they occupy nearly every position possible in various controversies, and they have collectively changed the rules for explicit and implicit logics of stories, it is no longer acceptably scientific to argue about animal models for a human way of life without considering female and infant activity as well as male. That result seems complexly the product both of a historical world-wide women's movement and of phenomena made visible by field and laboratory practice in primatology by culturally specific men and women. It has not just been the women whose scientific practice has responded to recent history. What would the stories be in a genuinely multi-racial field of practice?

Women scientists do not produce nicer, much less more natural, stories than men do; they produce their stories in the rule-guided public social practice of science. They help make the rules; it is a mundane affair requiring the trained energy of women's concrete lives. Responsibility for the quality of scientific stories, for the meaning of comparative tales, for the status of models is multi-faceted, non-mystical, and potentially open to ordinary women 'in' and 'out' of science. To ignore, to fail to engage in the social process of making science, and to attend only to use and abuse of the results of scientific work is irresponsible. I believe it is even less responsible in present historical conditions to pursue anti-scientific tales about nature that idealize women, nurturing, or some other entity argued to be free of male war-tainted pollution. Scientific stories have too much power as public myth to effect meanings in our lives. Besides, scientific stories are interesting.

In moral is that feminists across the cultural field of differences should contest to tell stories and to set the historical conditions for imagining plots. It should be clear that the nature of feminism is no less at issue than langur social habits. There seems a grain of truth in the dust jacket statement of Harvard University Press that simply putting females at an explanatory centre is in some sense feminist. But not just any story will do. Hrdy's sense of our illusions about our social life is not mine. The differences matter.