In which I describe some resources for rebuilding liberty that are coming together in the second decade of the twenty-first century.

MUCH OF WHAT has happened to the United States is not new. Cultures age. Political institutions become sclerotic. To that extent, ours is the story of all regimes that last long enough.

What’s new about the United States is that resurrecting the American project in an altered form is not an exercise in nostalgia. We don’t want to restore a bygone Golden Age. I don’t know of any Madisonians who want the 1950s back, let alone the 1780s. We just want to put government into its proper box, using a definition of “proper box” based on eighteenth-century principles but one that also accords with twenty-first-century realities. That’s a call to shape the future, not restore the past.

Charles Dickens’s famous opening of A Tale of Two Cities, “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times,” applies to us. Part I of this book described some of the ways in which this is the worst of times. But the last few decades have also given us new assets that the founders couldn’t have imagined. Along with them are new problems confronting our adversaries. Right now is also the best of times.

Of the things we have going for us, one stands out: technology that makes liberty practical as never before. Limited government and a high level of individual freedom no longer pose some of the problems that they used to pose.

Replacing Government Oversight with Public Oversight

Suppose we are back in 1900 and I am arguing with a progressive, trying to make the case for Madisonian freedom and limited government. There are reasons why the progressives won. In 1900, they have strong arguments in their favor.

First, my progressive adversary can point to numerous examples of local tyranny that go unchecked in the America of 1900. There’s the company town, where the dominant employer forces workers to shop at the company store and borrow from the company bank. Anyone who tries to unionize the workforce will be fired and perhaps physically attacked. In the South, local tyrannies are directed against African Americans. Local police ignore any inconvenient laws that interfere with keeping African Americans “in their place.” State governments are often indifferent to these abuses because the legislature and senior officials have been bought off or, in the case of the Southern states, share the mind-set of the localities. In 1900, it’s easy to argue that only the federal government can stand up to these local tyrannies.

Next, my 1900 progressive adversary can point to the helplessness of ordinary consumers. Information is hard to acquire and hard to share. Lack of information enables unscrupulous middlemen to buy crops at below-market prices or sell products at inflated prices. Lack of information enables food and drug producers to sell adulterated products to consumers who have no way of knowing what is in them. Lack of information enables people to pass themselves off as teachers or attorneys who actually know nothing about teaching or the law. Lack of information allows manufacturers to get away with selling inferior products, because bad reputations spread slowly. The only way to cope with these problems, my progressive adversary says, is through government oversight, licensing, and regulation.

Over the course of the twentieth century, technology turned out to be an extraordinarily powerful and efficient way of countering these problems. With regard to local tyrannies, the civil rights movement is the obvious case in point. It succeeded because of the development of news media over the twentieth century, especially television. The evening news showed videotape of black elementary-school children being escorted to school by National Guardsmen past whites shouting abuse at them, of Medgar Evers’s widow comforting her son at the funeral of that murdered civil-rights activist, and of a burning bus carrying Freedom Riders firebombed by a mob in Georgia. Such images drove a sea change in the consciousness of the white electorate about what was being done to black Americans in the segregated South that was impossible before television and became inevitable thereafter.

In the decades since, the competition among local television news programs has led to a nationwide capacity for searching out local tyrannies and getting them on camera. It is a way to win the ratings war. If the scandal is juicy enough, it will get picked up by one of a dozen network and cable news shows specializing in scandal and exposés. Letting the news outlets know about such behavior is as simple as an e-mail. For that matter, traditional media outlets are no longer necessary. Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, and a profusion of blogs specializing in such topics can be tapped by almost anyone with a grievance. There is no such thing as a local fiefdom immune from exposure to the rest of America.

The changes have been even more revolutionary in the availability of information about products and services. Commercial exchanges in a free market need two characteristics: they must be both voluntary and informed. Now they can be both in a way that was difficult in 1900. It doesn’t make any difference what you’re in the market for. There’s information on everything. Whether you’re looking for a new smartphone or a better pepper grinder, just Google smartphones or pepper grinders, and in a few minutes you will know everything about the merits of alternative choices. You’ll also have a choice of vendors from which to purchase the smartphone or pepper grinder of your dreams at the lowest price—usually for delivery tomorrow.

You need a plumber? You can go to Angie’s List and read about the experiences of your fellow citizens with different plumbers in your area. Looking for an apartment? You can go to Craigslist. You name it, and the Internet has an abundance of usable, reliable information. It also has a lot of unusable and unreliable information, but only members of the hard left think that the government should step in and run the Internet. We can figure it out for ourselves. With the Internet, freedom really does work. An unregulated Internet has empowered us to make informed choices about an incredibly wide range of goods and services. The government has become nearly irrelevant to this process. Cast your mind over the hundreds of questions you have used the Internet to answer during the past year, and consider how little you used government websites. For those of you who have needed to use government websites, how well did they meet your needs compared to commercial websites?

In the early 1900s, Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle led to government inspection of meat, for good reason. But suppose that the government stopped inspecting meat in 2015. What would Safeway do? Try to make money by selling contaminated meat? That would mean catastrophe; Safeway’s customers would know about it right away. Instead, Safeway would start touting its tough internal inspection system in an advertising campaign. Or the major food-store chains would get together and establish industry meat standards and inspection mechanisms that are more impressive than the government’s sketchy inspection process. The vulnerability of bad behavior in the total information environment of the Internet is much more important to the prosperity of corporations than their vulnerability to government inspection.

Technology is revolutionizing public safety. Historically, the interrelationships of crime, the police, and the public were among the toughest for a free society to handle. Somebody must have a monopoly over the right to physically coerce malefactors—the maintenance of public safety is one of the most elemental reasons for government to exist—but the police power is inherently subject to abuse. As America urbanized, metropolitan police departments were chronically beset by scandal, whether it was petty corruption, coerced confessions, or planted evidence. In the first half of the twentieth century, attempts to root out these problems through civilian oversight or internal controls had limited success. Then the pendulum swung the other way during the 1960s, when police were subjected to new procedural constraints by Supreme Court decisions. The likelihood that a felon would go to prison plummeted and the crime rate soared. By the late 1970s the pendulum had swung yet again. Wherever the pendulum was, conscientious cops needed a way to go about their work without getting hit by bogus charges of misconduct, but citizens equally needed a way to protect themselves from cops who ran roughshod over their rights.

Both police and citizens can now have that protection in the form of cameras that record every encounter between the police and the public. They began as cameras mounted on the dashboards of highway patrol cars. A few years ago, inexpensive body cameras became available. Experience to date has been a win-win proposition. In jurisdictions using this technology, the consistent result has been that the cameras not only deter police misconduct but also deter people from falsely claiming police misconduct.1

In the fall of 2014, two events showcased the importance of visual evidence: the shooting death of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, and the fatal chokehold applied by a New York policeman to Eric Garner. In the Brown case, a video record would perhaps have averted the rioting (if the police officer acted with good reason) or led to prosecution (if he acted without good reason). In the Garner case, a bystander’s video did exist—and the Staten Island grand jury failed to indict the police officer anyway. Some interpret this as evidence that video evidence doesn’t matter. I suggest an alternative: The reaction to the Garner case was nationwide, uniting liberals and conservatives in condemnation of the failure to indict. Future grand juries and trial juries will be extremely reluctant to reach decisions that are contradicted by video evidence.

The use of video technology in law enforcement is spreading rapidly and soon will be effectively universal—good police departments want it, and bad police departments will come under too much pressure to resist buying it. We can anticipate that the lack of a visual record will eventually be treated by the courts as police malpractice.

As time goes on, it’s not going to be just police who need to worry about bad behavior being recorded. So will corrupt bureaucrats, plus the larger number who misuse their authority to browbeat the people they are supposed to serve. Imagine what the defense funds could do with a video of a government official saying, “You try to fight this and we’ll put you out of business.” Government officials do a bad job of providing the transparency that politicians constantly promise, but technology is increasingly taking the choice out of their hands.

Public Surveillance vs. Private Surveillance

This discussion focuses on the benefits of ubiquitous video surveillance of public places and public activities. There are downsides, too—if nothing else, it is creepy to realize how much of our public activity can be caught on someone’s security camera or smartphone. But public activity is just that: the things we do when we are aware that we are in a public space, which by definition means that someone might be watching. In that sense it’s “our fault” if we are observed doing something embarrassing or illegal in public. The most ominous downsides of IT are associated with surveillance of private activities. The NSA and other government agencies can read our e-mail, listen to our telephone conversations, track our web surfing, and, in some cases, bug our homes or workplaces, and then store all this information indefinitely. Yes, private hackers do pose a threat to our private computers, but that’s a far cry from the NSA’s comprehensive daily monitoring of the nation’s electronic traffic.

An additional consideration is that the great bulk of public surveillance is done by private citizens and businesses. Government has lots of traffic cameras to go with the cameras used to monitor police interactions with the public, but those resources are outweighed by the security cameras maintained by businesses plus the ability of a couple of hundred million citizens with smartphones to record whatever is happening around them. It’s another example of the best and worst of times: we can celebrate the upside of public surveillance even as we worry about prospective misuse of the government’s massive private surveillance.

Scraping Away Sclerosis

The most exciting potential of liberation technology is for doing what the political process cannot do: crash through the combination of regulation and collusive capitalism that stifles innovation.

From one perspective, that’s what the Internet has already done. In the mid-1990s, the Internet was a patchy network of servers with clunky websites that only a computer geek could get excited about. It was not a target of regulation because there wasn’t much of anything to regulate. Then, in less than a decade, the Internet was providing services that government would have loved to regulate, but they had sprung up so fast and had acquired large user bases so fast that the regulators were stymied. If the government had seen Amazon coming, for example, it would have sought to regulate it, and the big bookstore chains would have tried to enlist the regulators in giving them a competitive advantage over the upstart. But Amazon got big and popular too fast. By the time that regulators recognized what juicy targets the Internet was producing, those targets were already firmly in place and could not be regulated with impunity.

During the past decade, services made possible by information technology have undertaken a more difficult task: moving into traditional businesses that are already highly regulated and finding ways to beat the system.

GIVING PEOPLE A PLACE TO STAY. Airbnb.com was one of the first. Begun in 2008 in a loft in San Francisco, Airbnb is a way for ordinary people to rent out lodging, from a spare room to an entire house, for use as vacation housing, for travelers who are facing sold-out hotels, or for travelers who are simply tired of staying in overpriced, boring hotel rooms. Airbnb doesn’t actually own a single room. It just brings together hosts and lodgers. Airbnb uses two-way feedback—ratings of lodgings by guests and ratings of lodgers by hosts—to make the system work. As of the fall of 2014, Airbnb reported more than 800,000 listings in 190 countries and had arranged lodging for more than 25 million guests.2

Inevitably, many jurisdictions are trying to bring Airbnb under their regulatory and taxation regimes. How these struggles will eventually play out is up in the air as I write. But this much is obvious: the regulatory state is having to play catchup.

GIVING PEOPLE A RIDE. An even more aggressive attempt to bypass the regulatory state involves real-time ridesharing, also known as “dynamic carpooling,” which has taken on the taxi industry.

Taxis are highly regulated. That doesn’t mean that a taxi is clean, that the trunk isn’t filled with the driver’s junk, or that the driver knows how to get to your destination. But in many cities, it does mean that it’s hard to find even a dirty taxi with an incompetent driver, because the taxi owners and city council have colluded to limit the number of taxis on the streets.

Ridesharing is made possible by the Internet and smartphones. For readers who haven’t already experienced one of the ridesharing services, I’ll use Uber, the biggest one, to describe how it works. You download the Uber app to your smartphone and register, providing your credit card information. When you need to get somewhere, you open the Uber app. A map appears that shows your location, the locations of nearby Uber cars, and how long it will take the nearest one to get to you. You press the Request button, and the car comes to pick you up (you can watch its progress on the screen). You hop in, the car takes you where you want to go, and you get out (payment is handled invisibly). Just as Airbnb doesn’t own a single room, Uber doesn’t own a single vehicle, and it uses ratings by customers and drivers of each other as an internal regulatory mechanism.

Ridesharing services get rid of all the things that make ordinary taxis a pain. They are so convenient that many people have already decided they don’t need to own cars themselves—it’s just as convenient and no more expensive to go everywhere through rideshare.

Uber and its main competitors, Lyft and Sidecar, are still works in progress. Not all of Uber’s drivers are paragons, and not all of its cars meet Uber’s standards. Its problems get immediate media exposure because of the buzz it has created.3 As I write, a counterattack is under way by the taxi industry.4

But the counterattack faces a couple of unprecedented problems. Uber doesn’t apply to the municipal government for permission and struggle for months to get approval. It just moves into a city and begins operations. By the time the city council and the taxi industry can coordinate their counterattack, lots of customers have already come to love Uber. Those customers are liberals, conservatives, and everything in between. They don’t see Uber as an ideological issue.[5] City councils that try to shut down Uber have encountered unprecedented public opposition.

Second, shutting down Uber is not easy—Uber often continues to operate despite injunctions to stop. Since Uber cars are unmarked, police have a hard time identifying the civilly disobedient people who insist on taking customers to destinations that they want to get to (and, one suspects, police don’t see a ride in an Uber car as high on their list of transgressions that need police intervention). When fines are levied, Uber has been known to pay the fines for their drivers (just as the defense funds would do for their clients).

Third, Uber has deep pockets (as I write, valuations of Uber range up to $15 billion) and its managers have thought through their strategy. City governments that go after Uber are not dealing with a business that can be cowed by city hall. On the contrary, a city hall that tangles with Uber has to worry about how much grief it is going to bring down upon itself, in the same way that I want regulatory agencies to worry about creating problems for themselves if they litigate against defense fund clients.6

Companies like Airbnb and Uber are eerily analogous realizations of the kind of strategy I propose for the defense funds, with citizens of most political views agreeing that the current state of affairs is ridiculous, jointly engaging in civil disobedience where necessary, backstopped by a well-funded, private entity to do battle with the regulatory state. These extensions of the general technique into the economy, made possible by liberation technology, have potential we cannot possibly gauge. Twenty years ago, who would have been able to envision Airbnb and Uber?

The federal government can easily hide much of its incompetence from the average citizen, who has no reason to be aware of what goes on fifteen management layers down in a federal bureaucracy. There’s the occasional news story about the $400 toilet seat or the $700,000 government contract to study methane gas emissions from cows, but the federal government is mostly invisible to the average citizen. Not so with state, county, and municipal government. Much of the potential for sweeping change will arise from a broadly shared perception in certain parts of the country that government is incompetent, driven by what is happening in state capitals and city halls.

It’s part of what Walter Russell Mead calls “the collapse of the blue model.” At the end of World War II, the United States was in a uniquely advantageous position. The war had devastated our economic competitors and enriched us. American industries could operate without worrying about foreign competition. White-collar and blue-collar jobs were stable. Tax revenues were ample for the demands of the time. Living standards were rising, vacations were getting longer, state-supported universities were inexpensive. “Life would just go on getting better,” Mead writes. “The broad outlines of our society would stay the same. The advanced industrial democracies had in fact reached the ‘end of history’: this is what ‘developed’ human society looked like and there would be no more radical changes because the picture had fully developed.”7

But it couldn’t last. Businesses that lack competition become just as sclerotic as governments. The pre-breakup AT&T did a good job of providing phone service, but it had no incentives to develop new technologies that might displace it, and no need to do so—it was cocooned in government regulations that safeguarded its monopolistic position. Lacking foreign competition, the Big Three automakers could make billions of dollars selling cars that spent far too much time in the repair shop. After a few decades of operating this way, large segments of the American economy were vulnerable to aggressive competition, and in the 1970s they began getting it. Companies across America experienced the shock of creative destruction. Unions became something that a competitive company couldn’t afford. Workforces were slashed when necessary; the days of lifetime job security with the same firm were over. So was the guaranteed pension—employers would contribute to a retirement fund, but it was up to the employee to take care of it.

Government was the only sector of the economy shielded from that creative destruction. Alone among American institutions, it continued to operate according to the blue model. Even as the private sector discovered it could not afford unionization, the public sector unionized. Even as the private sector realized that defined-benefit pensions could bankrupt them, the public sector locked in ever more generous ones. Even as job insecurity became routine in the private sector, the public sector continued to make it almost impossible to fire anyone.

Over the past decade, budget crises at the state level have shown how unsustainable the governmental part of the blue model is. For example, as recently as 2001, the assets and liabilities of state pension systems were about equal. As of 2012, state-run retirement systems had a $915 billion shortfall. The most recent data show that shortfall continuing to grow, long after the economy has emerged from the worst of the Great Recession.8 The gap is not spread equally around the country, but instead is concentrated in the bluest states—most conspicuously New York, Illinois, and California—which by now have funding deficits that will require either major tax increases or a default on the promised pensions.9

Blue cities are in just as much trouble as blue states. From the beginning of 2010 through the middle of 2014, thirty-eight municipalities around the country filed for bankruptcy. The most well-publicized examples are San Bernardino, Stockton, and Vallejo in California, and, of course, Detroit. But filing for bankruptcy doesn’t necessarily allow for institutional revitalization. Vallejo emerged from bankruptcy in a way that left it on the hook for its pension and union obligations. The result is that it still costs $230,000 for Vallejo to employ one police officer for one year.10

American workers are coming to recognize that the historic trade-off people made when they began a career in government has been altered. It used to be that a government job provided lower pay but greater job security. Now, in unionized government jobs except for the top levels, pay has matched or surpassed that of comparable jobs in the private sector, while job security is nearly absolute. In 2013, the average total compensation for state and local government employees was $42.51 per hour, 45 percent more than the equivalent figure for private employees.11 Unionized police in most jurisdictions can make good salaries, then retire after twenty years and collect a generous pension even though the retiree, still in his early forties, has taken a full-time job in the private sector. Unionized teachers almost everywhere have negotiated packages of salaries, guaranteed days off, and pensions that few private schools can match.12

The Internet is making these cozy arrangements visible. For example, Californians can go to TransparentCalifornia.com, which gives the income for every public employee in the state. One can search on people named “Murray,” for example, and discover that in 2011 a Murray who was a Los Angeles firefighter made $273,773 in salary, overtime, and benefits; a Murray captain in the Ventura Sheriff’s Department made $267,525; and a Murray deputy county administrator in Sonoma made $231,094. But it’s not just the extreme cases that make the point. Another Murray in Sonoma County has the job title of accounting technician—based on the job description, a clerk.13 Her pay and benefits came to $78,156.

The resources monopolized by generous personnel policies drain resources from the provision of essential government services. Cities with budgets that have ballooned over the last few decades don’t fix potholes or collect garbage nearly as well as they did in the 1950s. The same law-enforcement system that has such generous retirement packages for police may not have enough patrol cars. In the same school system where teachers with seniority make close to six figures, students may not have enough textbooks.

Government is visibly shoddy in all sorts of ways. Contractors who work for government know that the standards are different from those of the private sector, and use the same dismissive cliché: “Good enough for government work.” How do you know you’re in a government office building instead a corporate one? Look at the computers. The people using them may make more money and have better benefits than their counterparts in the private sector, but the computers themselves are a couple of generations out of date. The janitors make great money and benefits compared to janitors in the private sector, but the walls haven’t been repainted for years and some of the ceiling lights are burned out. How do you know that you’re dealing with the government instead of with a commercial enterprise? Because, in an age when you can order just about any consumer item twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, get it the next day, and return it with no questions asked if you don’t like it, your business with the government is still likely to have to be transacted during a restricted number of hours, perhaps a limited number of days, and in person. Too often, you have to go back three times to get the thing resolved. As Mead sums it up:

There are several ugly truths that the country (and especially the states whose governments are bigger and bluer than the rest) will be facing in the next ten years.

First, voters simply will not be taxed to cover the costs of blue government. Voters with insecure job tenure and, at best, defined-contribution rather than defined-benefit pensions will simply not pay higher taxes so that bureaucrats can enjoy lifetime tenure and secure pensions.

Second, voters will not accept the shoddy services that blue government provides. Government is going to have to respond to growing “consumer” demand for more user-friendly, customer-oriented approaches. The arrogant lifetime bureaucrat at the Department of Motor Vehicles is going to have to turn into the Starbucks barista offering service with a smile.

Third, government must reconcile itself to its declining ability to regulate a post-blue economy with regulatory models and instincts rooted in the past. The collapse of a social model is a complicated, drawn out and often painful affair. The blue model has been declining for thirty years already, and it is not yet finished with its decline and fall. But decline and fall it will, and as the remaining supports of the system erode, the slow decline and decay is increasingly likely to bring on a crash.14

Mead referred to “voters,” not “Republican voters,” with good reason. It’s not just conservatives who are grumbling about how their tax money is used. Failure to fix potholes is not a partisan complaint.

The potential for sweeping change is also going to be fed by the looming fiscal crunch at the federal level. In its 2014 projections for the budget and economy, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projected that from 2013 to 2024, federal outlays would increase from $3.5 trillion to $6.0 trillion—using unrounded numbers, a 74 percent increase in spending in constant dollars.15 That additional $2.5 trillion is an amount equal to the size of the entire budget as recently as 2002. It is a particularly stupendous number when you consider that this additional $2.5 trillion will be used to service a population that will have grown by just 9 percent since 2013.[16]

Where is the government going to get the money? Based on current laws (the basis on which the CBO is required to make its projections), the government will have to borrow a lot of it. The CBO projected that the federal budget deficit, which spiked to $1.4 trillion in 2009, would fall to a “low” of $478 billion in 2015 and then begin rising, passing $1 trillion in 2022 and continuing upward.17

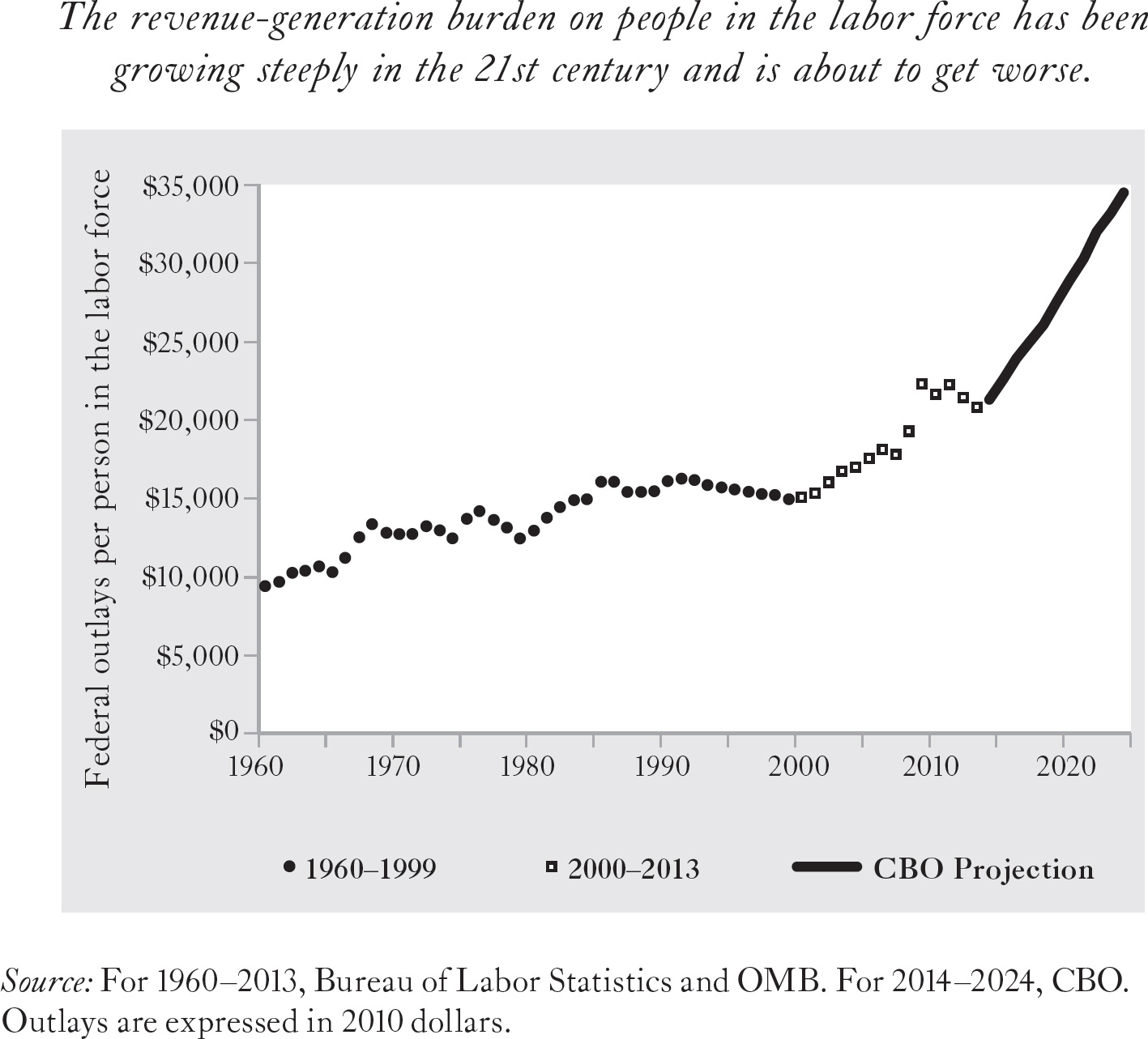

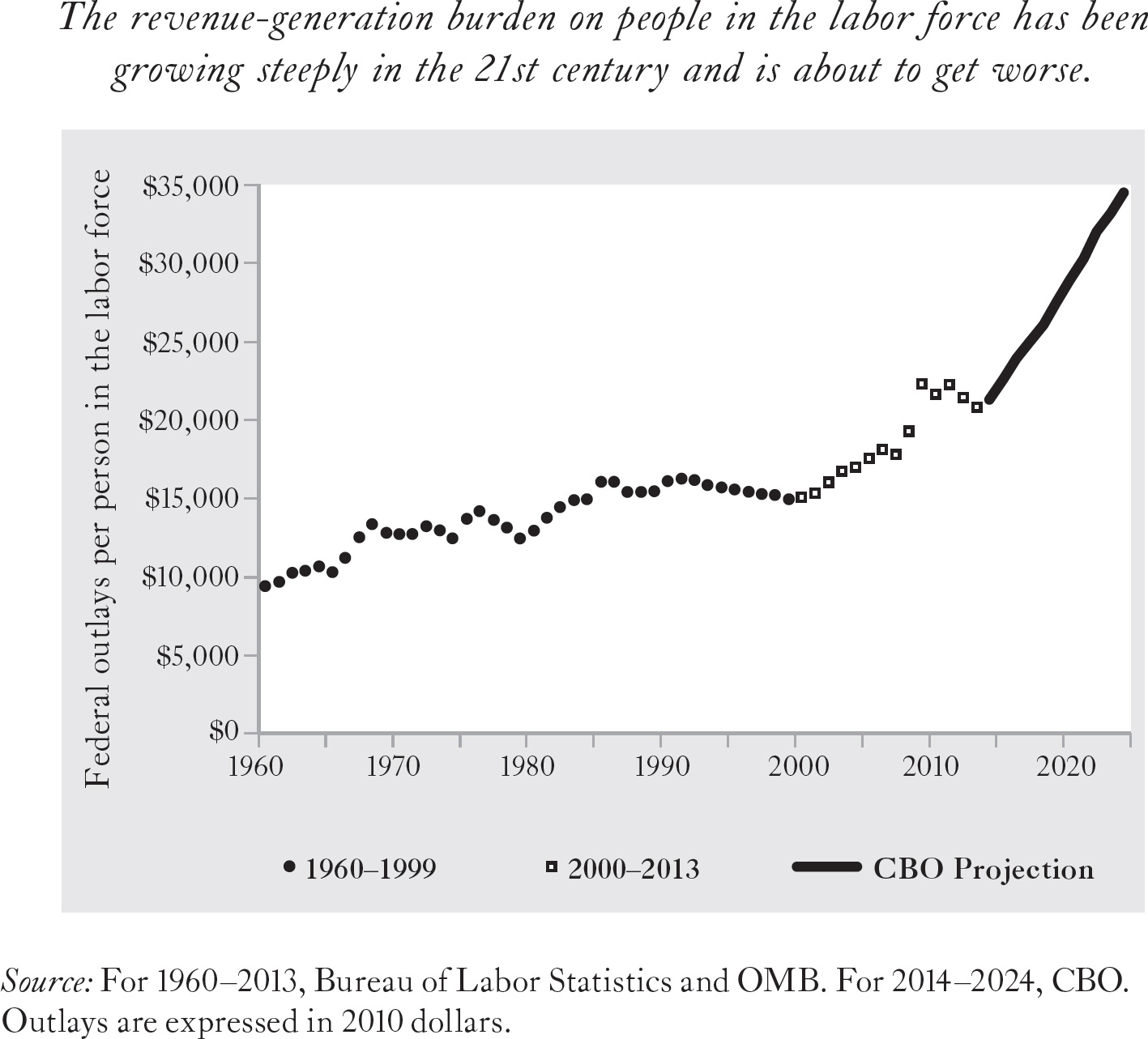

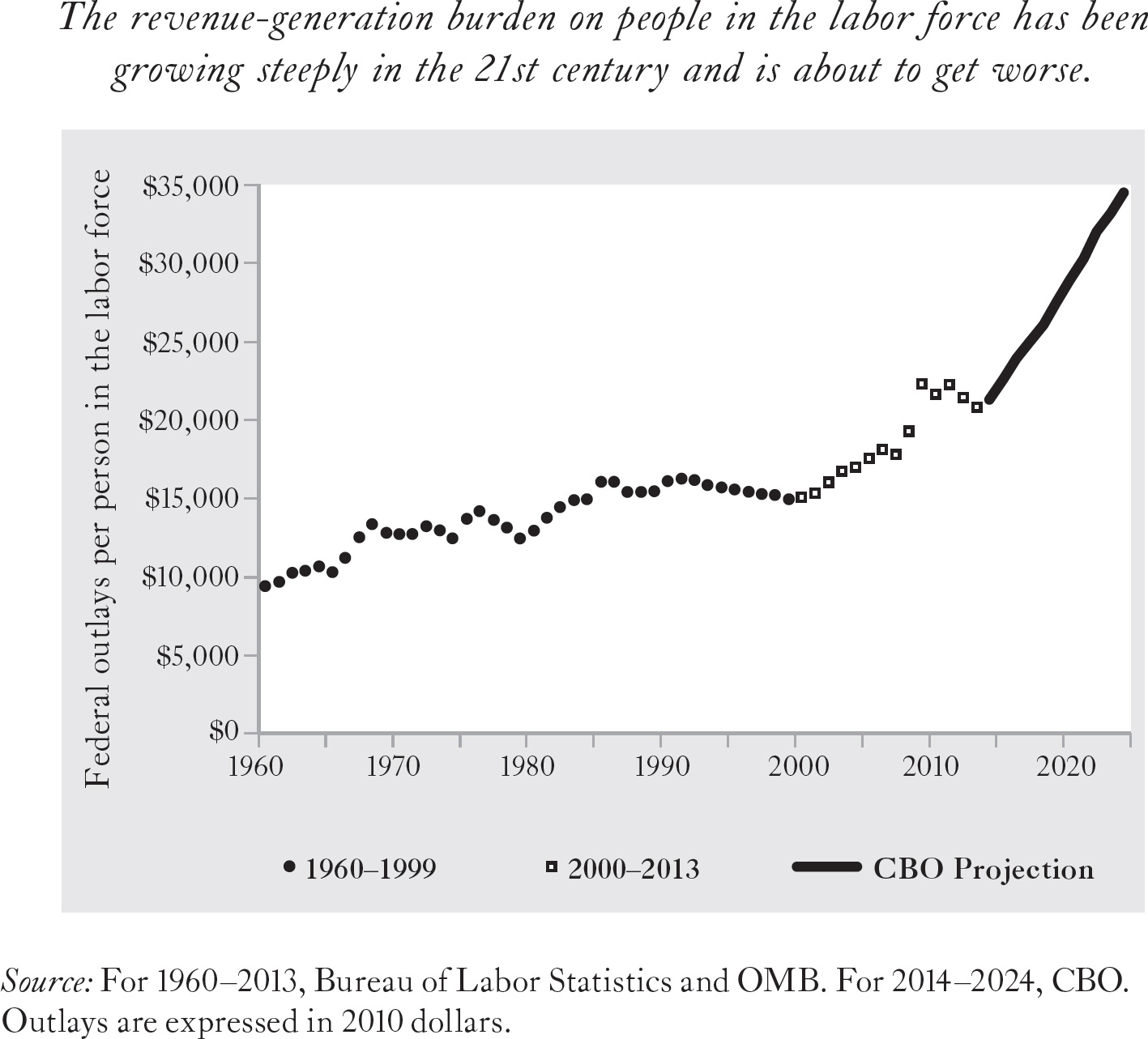

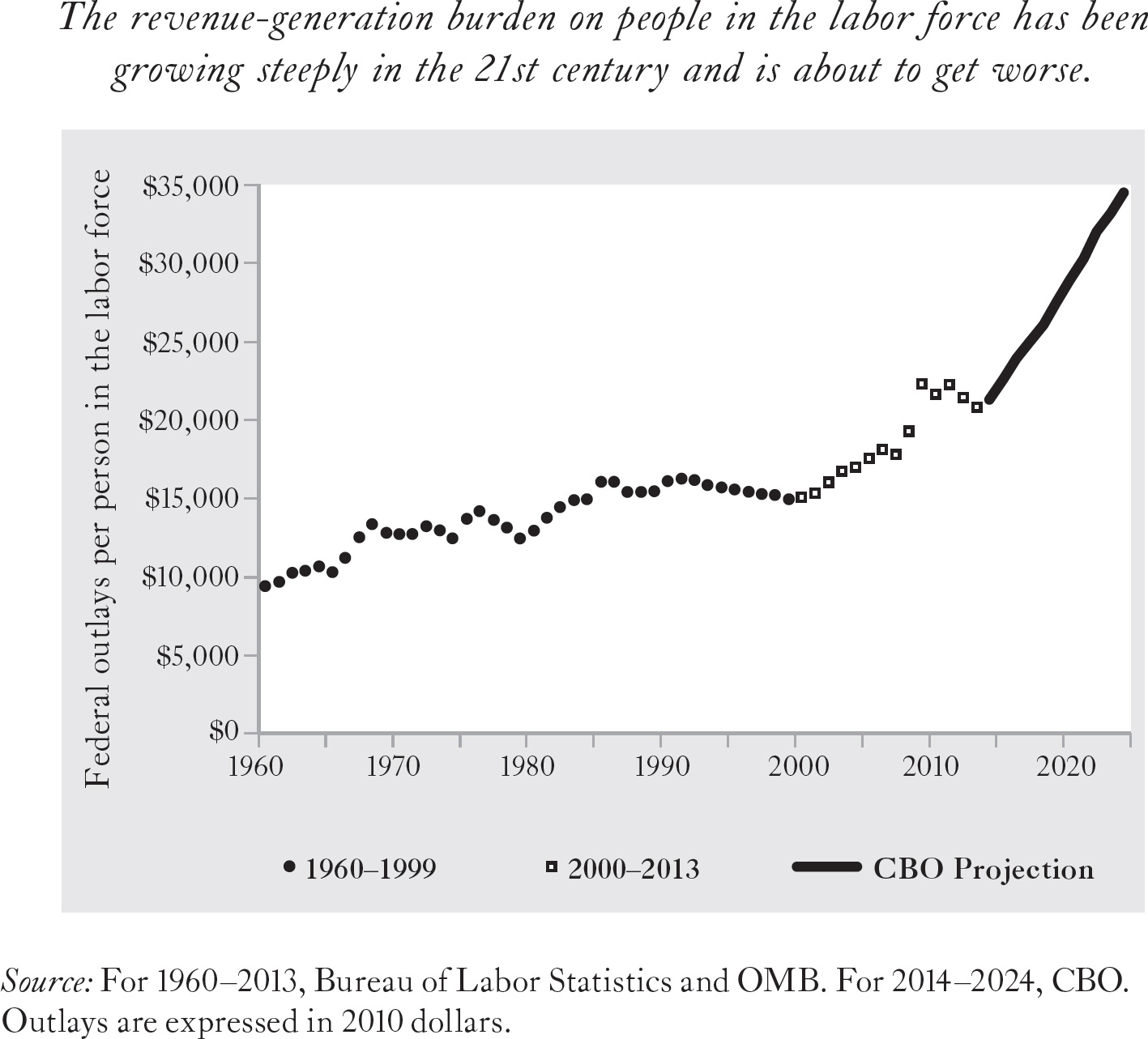

Meanwhile, economic growth is expected to generate an additional $2.2 trillion in revenues. But a shrinking proportion of the population will generate that increased wealth. Two factors contribute to the shrinkage. First, the population is aging. The leading edge of the baby-boom generation turned sixty in 2006, beginning an eighteen-year bulge in the percentage of Americans leaving the workforce and starting to collect Social Security and Medicare benefits. Second, working-age Americans are dropping out of the labor force. An increasing proportion of working-age Americans are being defined as physically disabled, thereby qualifying for lifetime disability payments and free health care. Still other working-age people are simply leaving the labor force, to be supported by spouses, relatives, girlfriends, boyfriends, or welfare. The figure below uses actual labor force participation rates for 1960 to 2013 and the CBO’s projections for 2014 to 2024 to show the implications of these trends.

The graph shows the ratio of total federal outlays to the number of people in the labor force. In 1960, the revenue-generation burden was a little less than $10,000 per person. From 1960 through 1985, the burden grew to a little more than $16,000.[18] From 1986 through 1999, the ratio dropped. Then the new century brought a substantial increase, from a little less than $15,000 in 1999 to almost $21,000 in 2013 (and an even higher spike during the Great Recession). But not even that rising burden matches what we can expect during the next decade. Based on the CBO’s projections, we can expect the burden to reach nearly $34,500 in 2024.

Now consider what a disproportionate amount of that burden must be carried by the top few deciles of that labor force. The IRS annually breaks down income-tax payments by income group based on adjusted gross income (AGI), showing the percentage of taxes paid by returns with AGIs in the top 1, 5, 10, 25, and 50 percent of returns. The following numbers refer to 2011, the most recent available data as I write:

• The filers in the top 1 percent of AGI paid 35 percent of all income taxes.

• The top 10 percent paid 56 percent of all income taxes.

• The top quartile paid 86 percent of all income taxes.

People who are not in the top quartile of earnings may view these numbers with equanimity (“Those rich guys can afford it”). Probably a majority of them would vote in favor of higher taxes for the rich. But only a tiny minority of the people within the top quartile are “rich” in the sense of mansions, private jets, or yachts. Sixty percent of the people in the top quartile are in the eleventh to twenty-fifth percentiles, with AGIs ranging from $70,492 to $120,136. To them, the idea that they are “rich” is crazy. A middle-aged couple in that income range is likely to have a couple of children, live in a modest house that carries a large mortgage, and drive a Honda. They’re trying to save for their children’s college educations and have little if any discretionary income.

Another 36 percent of those in the top quartile were in the second through tenth percentiles, with AGIs of $120,136 to $388,905. You will have a hard time convincing most of them that they are rich. At the bottom of the range, they live like those in the eleventh to twenty-fifth percentiles. At the top of that range, they are affluent, but their lifestyles are those of the upper middle class, not of the wealthy (especially if they live in an expensive city). No private jet. A Lexus, not a Rolls. A nice home, not a mansion.

The fabled 1 percent, with AGIs of $388,905 or more, does indeed include the rich who live a visibly rich lifestyle. But they are a fraction of the people in the 1 percent. Less than 1 percent of the 1 percent made more than a million dollars in 2011.19 The hedge-fund managers and the IT billionaires who live in a different universe from the rest of us are somewhere near the top 1 percent of the top 1 percent of the top 1 percent.

Meanwhile, half of those in the top 1 percent of income as of 2011 had total incomes between $368,000 and $443,000. They are doing quite well. If they live outside the most expensive cities in the country, they can afford a lifestyle that is obviously affluent. But that’s just half of the top 1 percent.

My point is that almost all of the people in the top quartile who supply 86 percent of the federal government’s income-tax revenue are not billionaires or even obviously rich, but corporate managers, owners of small businesses, attorneys, physicians, and other professionals who typically work long hours, often six or seven days a week, have been doing so from the outset of their careers, and are often married to a spouse who does exactly the same thing. They have earned their success.

Now take another look at that graph of the steeply increasing demand upon people in the labor force to pay for the growth in the federal government that the next decade will bring. The CBO divided revenue into four streams—income taxes, social-insurance taxes (Social Security and Medicare), corporate taxes, and “other.” Income taxes and social-insurance taxes account for 82 percent of the total. The top quartile of earners are responsible for shouldering around three-quarters of that 82 percent—and they will be responsible for shouldering about the same proportion of the increased $2.5 trillion in spending that the CBO projects for 2024.20

The IRS reports on the percentage of income taxes paid by different income groups get a lot of publicity. They are a common topic of conversation among people in the top quartile of income, and an impassioned topic of conversation among the people in the top decile. When they read about politicians demanding that the rich pay their “fair share,” there is a lot of anger—not so much about the size of their tax bills, per se, as about what they perceive as an injustice: they see themselves as hardworking citizens who provide a disproportionate amount of the government revenues that makes it possible for those politicians to keep spending so many trillions so inefficiently. The alienation crosses party lines.

Big business has an abysmal track record with respect to supporting limited government, but we shouldn’t be surprised. The function of corporations is to make a profit, not to defend free markets. Unless the owner or CEO has a personal commitment to limited government, managers of corporations have generally been willing to use the legislative process to acquire tax breaks or competitive advantages without worrying about the abstract role of government.[21] Most of them have learned to live with government regulation as well. Since the regulation of specific industries began with the railroads back in the nineteenth century, the most influential corporations have been adept in capturing the regulatory process so that it favors them and makes life difficult for those who would try to enter their markets. When economy-wide regulation took off in the 1960s and 1970s, big business made the best of it, as recounted in chapter 4. Big corporations have become deeply entwined in the iron triangle of regulators, politicians, and special interests that makes lobbying such a lucrative enterprise in Washington. Occasionally, the willingness of corporations to connive in aggressively anticompetitive laws has vindicated Ayn Rand’s most savage portraits of businesspeople colluding with government.

Underlying most of the collusive capitalism has been the less blameworthy mind-set described in chapter 5: “Like it or not, this is the world in which we’ve got to compete.” Many business executives openly despise the process. They may not be Madisonians, but they typically take pride in what they do and seek to provide value for money with a good product or service. They don’t like being treated as cash cows for campaign contributions, but if that’s what it takes to stay in the game, they do it. Recently, however, executives have been treated not as cash cows for campaign contributions but as cash cows for supplementing government budgets through the criminalization of business.

The vulnerability of corporations and their executives to criminal prosecution for their business activities goes back to the early twentieth century, but those violations usually involved crimes by ordinary definitions. The 1940s qualitatively broadened their vulnerability to criminal prosecution through the introduction of the responsible corporate officer (RCO) doctrine discussed in chapter 3, whereby a corporate official could be criminally charged for what amounted to a management error with no awareness on his part of wrongdoing. Subsequently, that was broadened to include management errors of omission as well as errors of commission. Then in the 1980s, Rudy Giuliani made his political reputation as New York City’s district attorney with highly publicized “perp walks” in which Wall Street executives were taken in handcuffs from their offices to police cars, arrested on charges of financial wrongdoing.

In the last few decades, this criminalization of American business has taken a new turn. As recently as 2002, the total annual criminal fines levied on corporations was less than $100 million. Only once between 1994 and 2002 did total fines exceed $1 billion, and then mostly because of a single large fine paid by Pfizer. Then in 2007, total fines reached $2.5 billion. In 2011 they surpassed $4 billion.22

The size of individual fines also went up. In 1994, the average was under half a million dollars. In 2010, the average hit almost $16 millon. In 2013, a new record was set following the BP oil spill: $1.26 billion.23

Then things went crazy. In just the first eight months of 2014, The Economist was able to identify settlements with major banks and corporations that had produced something in the neighborhood of $100 billion in fines. A single fine imposed on a French firm called BNP Paribas for breaches of American sanctions against Sudan and Iran came to $9 billion.24

What’s going on? One possibility is that corporations have become incredibly more evil over the past few decades (and especially in the past few years), or that the Department of Justice has become incredibly more efficient at uncovering evildoing. Legal scholar Brandon Garrett makes that case, in more elegant terms and with many specific examples, in his book Too Big to Jail.25 Another possibility is that we are watching shakedowns. As The Economist described it, “The formula is simple: find a large company that may (or may not) have done something wrong; threaten its managers with commercial ruin, preferably with criminal charges; force them to use their shareholders’ money to pay an enormous fine to drop the charges in a secret settlement (so nobody can check the details). Then repeat with another large company.”26

These settlements are known as deferred-prosecution agreements. Deferred-prosecution agreements had never been used before 1992. Only 17 occurred from 1993 through 2003. From 2004 to 2014, 278 such agreements were entered into. Now they are ubiquitous. Here’s how Garrett approvingly describes their purpose: “Prosecutors now try to rehabilitate a company by helping it to put systems in place to detect and prevent crime among its employees and, more broadly, to foster a culture of ethics and integrity inside the company.”27 If the corporation accedes to these conditions and pays the fine, the government agrees not to bring a criminal prosecution. Among other things, the agreement usually involves embedding government enforcers within the firm.

What is rehabilitative from Garrett’s point of view looks to others like the apotheosis of the regulatory state: use complex regulatory regimes to threaten years of unbearable legal hassle and expense, effectively coerce the deferred-prosecution agreement, and thereby insert government oversight into the interior of the organization and bring in hundreds of millions, or billions, of dollars of revenue.28

So far, corporate America has seldom fought back. It’s the shareholders’ money that pays the fines, and settling in secret enables executives to avoid career-ending publicity and perhaps jail time. In addition, there is a pragmatic risk/reward calculation to be made on behalf of the shareholders. Is it better to pay a billion now and get on with business, or engage in a multiyear legal battle that will cost at least hundreds of millions and may end up costing an even bigger fine? Or cost the corporation its existence? The experience of Arthur Andersen, the accounting firm, is cautionary. It fought an obstruction of justice charge in court, was convicted by the jury, appealed, and won a reversal from a unanimous Supreme Court. But the initial conviction destroyed the firm, and vindication came too late.29 Knuckling under for the big shakedowns follows the same logic that leads corporations to reach out-of-court settlements with employees who allege racial or gender discrimination. Even if a charge is frivolous, it’s cheaper to pay out of court than go to court and win.

If the government has been behaving with integrity in this process, and exposure of the sealed settlements would reveal that the companies have behaved badly enough to warrant their multibillion-dollar settlements, then corporations have no choice but to start behaving better, and that’s as it should be. But if it is the government that has been behaving badly, selectively choosing what regulations to enforce against whom so as to yield a large cash windfall, corporate America will have to start asking itself whether it can afford to coexist profitably with the regulatory state.

Part of corporate America is already eager to rebel—many CEOs are already angry with the regulatory state on principle. But you don’t have to hold Madisonian principles to be angered by government acting like the Mafia. Shakedowns are ugly. If that is in fact what has been going on, the time is ripening for a broad swath of CEOs to start treating government as “them,” an entity to be resisted.

It will not be an across-the-board shift. Collusive capitalism has become essential to the defense, pharmaceutical, health-care, agribusiness, and financial industries, and their incentives to go along to get along will probably be too powerful to resist.30 But that leaves large numbers of companies that are less dependent on government contracts and less enmeshed in the regulatory web. The most promising leader of a revolt against the regulatory state is the IT industry. It is still far less regulated than other industries, and the corporate cultures of places like Google, Apple, and Facebook are independent, even libertarian.

Here’s where the activities of the defense funds come into play. If the defense funds have been operating for some years and have successfully challenged the government’s enforcement of illegitimate regulations, large corporations will take notice. At some point, some of them will start defending themselves. If large components of corporate America decide to join the fight against intrusive government, it could be a game-changing event.

When Jimmy Carter left office, federalism seemed to be as dead as the enumerated powers. The original dual federalism that prevailed until the constitutional revolution of 1937–1942, in which the states still had reasonably well-understood areas of independent authority, gave way to “cooperative” federalism. Under cooperative federalism, the federal government had nearly unlimited power to override a state’s policies. At the same time, large cash grants increasingly drifted downward from Washington to the states—accompanied, of course, by instruction about how those funds might be used.31

Then Ronald Reagan came to office with a pledge to devolve authority to the states. He was able to accomplish some of that with executive orders, increased use of block grants, and other devices that loosened the strings attached to federal aid, but his most effective ally was William Rehnquist, whom Reagan elevated from justice to chief justice of the Supreme Court in 1986. Rehnquist was the guiding force behind a series of decisions during his twenty-year tenure as chief justice that led to what has been called “the new federalism.”32 It was not a return to the pre-1930s division of power. Its real effects on the states’ independence were minor, and mostly involved greater state participation in processes that remained ultimately under the control of the feds. But most legal scholars agree with Kathleen Sullivan’s assessment that the “Rehnquist Court’s federalism revival was theoretically deep even if practically limited.”33 The Roberts Court has continued that revival to some degree.

During the last decade, these modest increments in federalism have been augmented by what can best be described as increased feistiness on the part of the states. It is reflected in their approach to regulation. Both OSHA and the EPA permit state agencies to conduct enforcement activities, and about half of the states have availed themselves of that option. A study of 1.6 million OSHA audits from 1990 through 2010 found differences between the outcomes from inspections conducted directly by the feds and those conducted by state employees. State inspectors were more sensitive to local economic conditions, reducing the number of violations as unemployment increased. They also issued smaller fines than the federal inspectors, a procedure, the authors concluded, that “likely results in fewer hearings and challenges on the part of firms, removing a layer from the bureaucracy of enforcement and the costly employment of legal professionals and regulatory consultants on the part of sanctioned firms.”34

A progressive website in favor of strict enforcement found similar differences between state and federal inspectors in EPA actions. The author complained that many states have “shifted resources toward compliance assistance programs” and have even gone so far as to create “customer service centers.” Many states impose smaller penalties than the EPA itself assessed in similar circumstances, and “do not follow EPA guidance for responding to violations with ‘timely and appropriate’ enforcement actions.” The list of the states’ sins go on, concluding with the worst of all: “Almost one-half of the states have enacted environmental audit privilege or immunity laws that preclude penalties for violations voluntarily disclosed and corrected by regulated entities as a result of environmental audits.”35 Shocking.

Apart from subtly competing with federal regulatory agencies, the states have also been engaged in various forms of independent action that seem plainly unconstitutional. The Supremacy Clause states that federal laws “shall be the supreme law of the land; and the judges in every state shall be bound thereby.” In that light, it is remarkable that, as I write, twenty-one states and the District of Columbia have passed laws legalizing marijuana in some form despite the Controlled Substances Act of 1970, which makes the production, distribution, or use of marijuana illegal. Most of these decriminalize the possession of small amounts of marijuana or legalize marijuana for medical use. Two states, Colorado and Washington, have legalized marijuana for recreational use. On August 29, 2013, the Department of Justice announced that it would defer its right to challenge these state laws, contingent on the states establishing “strict regulatory regimes that protect the eight federal [enforcement] interests” that are the Department of Justice’s highest priority.36 Or to put it another way, the Department of Justice has affirmed that the federal government can challenge those laws, which are plainly unconstitutional, but, for the moment, never mind.

The marijuana laws are just one example of a broader phenomenon. From the end of the Civil War through the 1960s, the traditional justification for federalism was overshadowed by a “states’ rights” movement that was identified with the South and its efforts to preserve a racially segregated society. But in recent decades, as political scientists Christopher Banks and John Blakeman write, liberals have discovered the merits of federalism:

Some progressives and others observe that the growth in federal power has been matched by efforts in the states to legislate in social policy areas that traditionally have been ignored or scorned by federal officials, especially in times of conservative control. These initiatives, which encompass advancing gay and lesbian rights, banking regulation, health care, environmental control and international law principles, have coalesced to form “blue state federalism.”37

Conservatives in general and Madisonians in particular have always been advocates of muscular federalism. That the left is joining in that advocacy, albeit for different reasons, gives reason to expect that the state marijuana laws are just the thin edge of the wedge. The federal government does not rely on voluntary compliance with its laws only from individuals. It also must rely on the voluntary compliance of state and municipal governments. In the past, liberal administrations in Washington have been comfortable enforcing their will on conservative states and municipalities. The marijuana case demonstrates how reluctant a liberal administration is to do the same thing with liberal states and municipalities. It is a precedent begging to be exploited.

This brings us to the state of the federal bureaucracy. Bureaucrats have to endure popular abuse that is often over the top. “In America,” as political scientist Peter Schuck has observed, “bureaucracy is often used as an epithet, evoking ubiquitous red tape, rigidity, soullessness, waste, unreasonableness, impenetrability, and Kafkaesque cruelty and arbitrariness.”38 Since it will soon appear that I am piling on, let me begin with some caveats.

Students of bureaucracy have consistently found that government workers who are engaged in tasks that carry with them a strong sense of mission—such as the military, police, firefighters, paramedics, and air-traffic controllers—are as likely as anyone in the private sector to perform at a high level of excellence. Some bureaucrats in the regulatory agencies with especially sensitive responsibilities—those charged with ensuring the safe handling of nuclear-weapons material, for example—presumably have a similarly strong sense of mission. To that, let me add what should be obvious: As individuals, bureaucrats are as nice, honest, loving to their children, and helpful to their neighbors as any other group of people—or such is the impression of someone who has counted many government employees as friends and acquaintances during four decades of life in the Washington area.

None of this is inconsistent with the larger truth: When the pedestrian tasks of government are involved, the rules by which government bureaucracies are run foster poor performance and low morale. I will limit the discussion to the way federal bureaucracies are structured and administered, but they apply generically to state and municipal bureaucracies as well. For readers who want the details, Paul Light’s A Government Ill Executed is a highly regarded source, and Peter Schuck’s chapter on bureaucracy in Why Government Fails So Often is an excellent synthesis of the recent literature. James Q. Wilson’s Bureaucracy, first published in 1989, remains the indispensable basic text.

LEADERSHIP. The top jobs are filled by people selected by the president, often for reasons having nothing to do with their technical or administrative skills. That’s a recipe for ineffectual management, especially when the incoming appointees have not had experience in Washington or are not familiar with the institution’s history. Even when the newly confirmed administrators are experienced and competent, career civil-service employees all know ahead of time that the new guys are not going to be around for long.39 The median tenure of political appointees is 2.5 years, with a quarter of them serving fewer than 18 months.40 Many senior jobs go unfilled for long periods of time, sometimes entire presidential terms. In recent history, the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives did not have a senate-confirmed director for six years.41

HIERARCHY. The typical bureaucracy in the federal government is an efficiency expert’s nightmare. In the private sector, vibrant businesses are managerially streamlined, with only a few management layers and easy lines of communication between decision-makers and personnel on the front line. Vibrant or not, few corporations have more than six management layers. The median for cabinet departments in the federal government is twenty-two layers.42 The functional distinctions among these layers are excruciatingly vague, with sixty-four executive titles open for occupancy.43 Yes, there really are people whose job title is “deputy associate deputy administrator” and “chief of staff to the associate deputy assistant secretary.” These paralyzingly numerous layers of management help explain why getting a decision on anything takes forever, and why bright ideas generated by federal employees are unlikely to get through all the approvals that are required to make a change. It also helps explain why just about everything in most federal offices is behind the times, whether we’re talking about design, organization, or equipment. Even getting routine office supplies is often a hassle.

COMPENSATION. In the federal government, as in state and local governments, positions below senior management have excellent salaries and benefits compared to similar jobs in the private sector.44 But in 2014 the federal salary scale topped out at $130,810 for the highest step of the highest grade in the General Schedule and at $181,500 for the Senior Executive Service—levels far below the compensation that a senior corporate manager gets.45 The result: Talented managers seldom want to go into government in the first place, talented managers who do go into government get hired away by the private sector, and untalented government managers stay with the government career ladder and end up occupying many of the senior career slots.

JOB TENURE. One of the most crippling defects of the federal bureaucracy is that people are so hard to get rid of. In the private and public sectors alike, many hiring decisions are mistakes. Workers who are incompetent, lazy, or devious not only impair the productivity of the organization by failing to do their jobs well, they also create resentment and low morale among their coworkers. Besides that, people who know they can’t be fired are not nearly as responsive to a supervisor’s direction as workers who can be fired.

The private sector has two resources for culling incompetent workers: layoffs when business is bad or a reorganization has eliminated positions, and firing for cause. The government hardly ever lays off anybody, and firing someone for cause requires such an investment of time and effort (the process takes one to two years) that the entire federal government fired just 0.55 percent of its workers in 2010.46 Unless government’s hiring procedures are an order of magnitude more precise than the private sector’s—an absurd assumption—it is inevitable that government bureaucracies are filled with people who would long since have been pushed out the door for incompetence if they worked in the private sector.

COMPETENCE ON THE JOB. Nobody really knows just how bad the situation is. The private sector has bottom lines that tell companies how well their organizations are doing as a whole. Usually there are also measures of productivity for specific jobs. Few jobs within the federal bureaucracy have such measures. There are, of course, supervisors’ performance ratings of their subordinates—and they are meaningless. This was brought to public attention in 2014 when a scandal at the Veterans’ Administration broke. A congressional hearing into the many and serious failures of the VA, including a cover-up of those failures by senior management, revealed that all of the 470 senior executives at the VA had received annual ratings of “fully successful” or higher.47 Of course, that also meant that none had received either of the two lowest ratings, “minimally satisfactory” or “unsatisfactory.” A spokesperson for the VA defended the ratings by pointing out that in the entire federal government, only fifteen senior executives had received either of the two lowest ratings in the most recent year.

HOW HARD THEY WORK. The public’s widespread belief that government workers show up late and go home early has some basis in fact. An analysis of time-use data collected by Census Bureau indicates that over the course of year, the average government employee works 152 fewer hours than employees in the private sector—equivalent to 3.8 forty-hour work weeks.48

MORALE. Paul Light conducted a survey of morale among federal and private-sector employees. The results once again support the stereotypes. Light found that federal employees liked their benefits and job security, and not much else. They were much less satisfied than private-sector employees with their opportunities to develop new skills and accomplish something worthwhile. They were dissatisfied with the resources they were given to do their jobs well. They gave poor ratings to the competence of their colleagues and supervisors. They rated their organizations unfavorably when it came to spending money wisely, helping people, acting fairly, and being worthy of trust.49

It is bad that government has these problems because it means government often performs its legitimate functions poorly and inefficiently. It is propitious because these problems make the federal government an easily discouraged adversary in cases of low-level civil disobedience.

That statement is not true for prominent cases. Surely the Department of Justice puts its best talent into key antitrust cases, the EPA does so when it takes action against the biggest polluters, and the FBI does so when it’s going after the best-organized crime syndicates.

But most of the open-ended possibilities for rebuilding liberty will not involve landmark cases that the federal government can focus on—there need be no Gettysburgs or Yorktowns, just hundreds of hit-and-run guerrilla actions. The situation facing the defense funds will be an instructive model for subsequent steps to roll back the reach of government.

The defense funds are going to be defending not huge corporations but many individuals and small businesses—cases that won’t be contested by a task force of attorneys but by one or two people far down in the chain of command. Some of those may end up being landmark cases, as Sackett became, but, like Sackett, they will start out as small, inconspicuous ones.

In other words, the contest between the defense funds and the government is going to be a mismatch between people who typically feel strongly that they are being arbitrarily and capriciously harassed by the government, represented by attorneys who believe strongly in the justice of their cause, fighting against government bureaucrats of middling talent and little motivation to work extra unpaid hours, for whom contesting a case against an aggressive defendant looks like a lot of hard work for no reward. They will know that a defendant won’t even have to pay the fine if the government wins the case.

“A lot of hard work for no reward” brings us to the ways in which the defense funds can convert the dysfunctions of the legal system and turn them into weapons. For the defense funds, the point of litigating a case is not necessarily to win it in court. The defense fund has accomplished its goal if the regulatory agency subsequently begins backing off cases whenever it hears that a defense fund has gotten involved. It’s not that the agency fears the possibility of losing. It fears the amount of work it will take to litigate the case.

These observations about the nature of the bureaucracy and of the legal system apply specifically to the work of the defense funds. But they also have another implication. Maybe, just maybe, when the other enabling forces come together, the potential for change is far broader than anything that the defense funds accomplish directly. And that in turn brings us to a speculative look at the future.