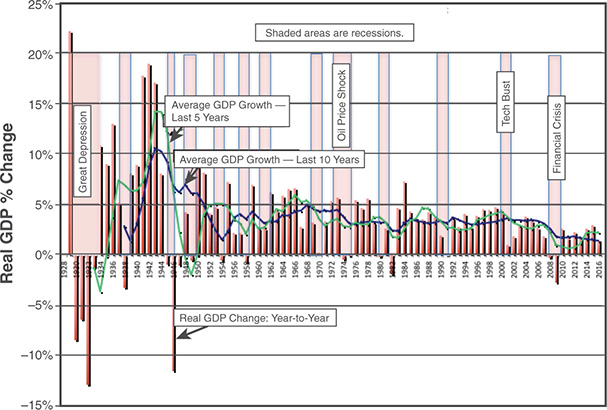

Figure 8.1 U.S. Real Economic Growth Over Time: 1929 to 2016

Companies operate in a larger economy, sometimes just domestic and often global, and the assumptions we make about macroeconomic variables affect the valuations of all companies. This chapter begins by looking at how changes in the real economy, inflation, and exchange rates affect valuation. It also looks at the historical behavior of each of these variables. With each of these variables, we also examine how analysts deal (or avoid dealing) with them, in the course of valuing companies. They often make implicit assumptions about growth and inflation that might be unrealistic or explicit assumptions that are internally inconsistent. We evaluate whether we should be building in views on the macroeconomic variables and, if so, how best to do this.

Every business is affected by the state of the economy, although the magnitude of the effect might vary across businesses. This section looks at how the growth in the real economy affects inputs into the valuation of individual companies. It also goes into some history on real economic growth.

When valuing companies, we have to estimate growth in revenues, income, and cash flows over time. Although we tend to look at the company’s specific prospects while making these estimates, a company’s operating numbers are influenced by the state of the economy in which the company operates. Put more simply, the revenues and earnings numbers look much better if the economy is doing well than if it is slowing down or shrinking. Because we are forecasting these numbers for the future, our estimates for individual companies are affected by how well or badly we think the economy will do over the next few years.

Although all companies might be affected by the growth rate of the economy, they are not affected to the same extent. We expect companies in cyclical businesses, such as housing and automobiles, to be affected more by overall economic growth. Conversely, companies that produce staples should be affected to a lesser extent by whether the economy is in boom or recession mode. Consequently, optimism about future economic growth will result in higher values for the former, relative to the latter. The effect of changes in economic growth on company valuations can also vary, depending on whether they derive their value primarily from existing assets or growth assets. Not surprisingly, companies with significant growth assets see their values change much more dramatically in response to shifts in the overall economy than mature companies.

Finally, economic growth affects other key market-related inputs into valuation. In Chapter 6, “A Shaky Base: a ‘Risky’ Risk-Free Rate,” we noted that risk-free rates tend to change over time and that change is often related to real economic growth. When economies are growing briskly, risk-free rates tend to rise, whereas economic slowdowns are associated with lower interest rates. In Chapter 7, “Risky Ventures: Assessing the Price of Risk,” we traced the shifts in equity risk premiums and default spreads over time. We noted their tendency to rise with uncertainty about the economy and investor risk aversion.

How much does real economic growth change from year to year? The answer clearly depends on which economy we look at. The first part of this section focuses on real economic growth in the U.S. over time and shows how both real and nominal growth have varied across time. We will also look at how real economic growth has affected the aggregate earnings and dividends of publicly traded firms. In the second part of the section, we will expand the discussion to encompass other countries, including the fast-growing emerging markets of Asia and Latin America.

During the 20th century, the U.S. grew to become the dominant global economic power, but the growth was not uninterrupted. Extended periods of economic decline and stagnation occurred, with the Great Depression being the most significant example. Figure 8.1 summarizes annual changes in real Gross Domestic Product (GDP) for the U.S. from 1929 to 2016.

The shaded areas in the figure represent recessions, at least as defined by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER). Two consecutive quarters of negative economic growth in real GDP has become the rule of thumb for classifying recessions. Table 8.1 summarizes the business cycles since 1945 in the U.S., with the length of each cycle in months.

Table 8.1 U.S. Recessions (in months): 1945-2016

Start of Recession |

End of Recession |

Length of Recession (in months) |

Mar-45 |

Oct-45 |

7 |

Dec-48 |

Oct-49 |

11 |

Aug-53 |

May-54 |

10 |

Sep-57 |

Apr-58 |

8 |

May-60 |

Feb-61 |

9 |

Jan-70 |

Nov-70 |

11 |

Dec-73 |

Mar-75 |

16 |

Aug-81 |

Nov-82 |

16 |

Aug-08 |

Feb-09 |

7 |

Mar-01 |

Nov-01 |

8 |

Jan-08 |

Jun-09 |

18 |

Average |

|

11 |

Median |

|

10 |

High |

|

18 |

Low |

|

7 |

Source: FRED

Looking at this long time period of history, some interesting facts emerge that might have implications for how we deal with real growth in valuation:

Cycle length is unpredictable: The cycles have no systematic length, making it difficult to forecast the length and duration of the next cycle. The boom cycles of 1982 to 1990 and 1991 to 2001 have been the longest (100 months or longer), but the boom cycle prior to that lasted only 28 months. The average boom cycle lasted 55 months, but the cycles have become longer since World War II.

Recession length has varied: Since the Great Depression, recessions have lasted anywhere from eight to 18 months and have ranged from mild (2001 to 2002) to strong (1981 to 1982). It is true that recessions have become shorter, on average, since the Great Depression—perhaps because central bankers have become better versed in the tools for dealing with recession. The 18-month recession from December 2007 through June 2009 is perhaps a cautionary note that the powers of central banks has waned, in terms of managing recessions, perhaps because of globalization.

Hindsight is 20/20: One fact that does not come through when we look at this table is that the dates for the economic cycles are determined with the benefit of hindsight. In other words, investors and businesses were unaware in July 1990 that they were entering a recession. It was only in early 1992 that the NBER finally got around to categorizing the July 1990 to March 1991 time period as a recession.

If we accept the proposition that predicting economic cycles is impossible and that we should focus on estimating real growth over the next five or ten years rather than the growth in the next quarter, our task becomes easier (at least in hindsight). Figure 8.1 includes a smoothed-out estimate of real growth over the next five years and the next ten years to provide a contrast to the year-to-year real-growth numbers. The ten-year growth rate estimated in 1954, for instance, is the average growth rate from 1954 to 1963. Note that these long-term forecasts have far more stability, especially since World War II. Both the five-year and ten-year average growth rates have been between 2% and 3%. This stability suggests that using a reasonable real-growth rate number for the long term is more important (and viable) than forecasting growth on a year-to-year basis.

Real growth affects valuation through the earnings and cash flows reported by businesses. Therefore, Figure 8.2 shows how aggregate earnings and dividends on the S&P 500 have behaved over time, as real economic growth has varied.

Looking back at the last 80 years of earnings and dividends on the S&P 500 companies, three trends emerge. The first is that both earnings and dividends are sensitive to economic conditions, with both declining during recessions. The second is that earnings are much more volatile than dividends over time. The third is that although earnings growth is loosely correlated with real economic growth, the two are not always in sync, with low (high) earnings growth in some periods of high (low) real growth, reflecting both lags between economies and business operations as well as the globalization of companies. For instance, earnings growth at U.S. companies has been robust between 2009 and 2016, notwithstanding slow growth in the U.S. economy, partly because U.S. companies derive so much of their revenues overseas.

As a final test, Figure 8.3 shows how the level of the S&P 500 index has changed over time as a function of real economic growth.

Looking at the changes in real GDP growth and changes in the S&P 500, it seems clear that the index is far more volatile than the economy. Another interesting and more subtle relationship is also visible for most of the graph. Stock prices seem to drop prior to the slowing down in the real economy and seem to start their rise prior to the actual recovery taking hold.

Estimating both short-term and long-term real growth in a mature market like the U.S. is far simpler than forecasting growth in young economies, especially ones that derive much of their growth from a commodity or specific sector. The fact that these economies are small, relative to the global economy, can allow them to grow at double-digit rates in good years and suffer catastrophic drops in bad years. Figure 8.4 summarizes real-growth rates for four time periods: 1997–2001, 2002–2006, 2007–2011, and 2012–2016 in Brazil, India, China, and Russia and contrasts them with real-growth rates in the European Union (EU) countries, Japan, and the U.S.

Not only are real-growth rates higher in the smaller, emerging markets than in the mature economies, but they also tend to be volatile. Among the BRIC countries, China clearly dominates in real growth over the period, whereas Russia lags. Among the developed countries, Japan has had the lowest real growth rate over this time period and the Euro zone has seen real growth decline in the last decade. It should come as no surprise that developed market companies increasingly look to emerging markets, in general, and China, in particular, to recapture their growth potential.

In their zeal to incorporate the effects of real growth and views on how that real growth affects the values of companies, analysts are often tempted to overreach. In particular, three practices in valuation, related to real economic growth, can give rise to skewed end numbers:

Forecasting future cycles: Analysts, and especially those valuing cyclical companies, start with the unassailable logic that their companies’ earnings are a function of whether the economy is in recovery or recession, but then go off the tracks by not only forecasting where the current economic cycle is headed but also future economic cycles. As you can see in Figure 8.1, it difficult enough to forecast when cycles begin and end and impossible to predict future economic cycles.

Bringing in strong idiosyncratic views on the economy: Some analysts have strong views on the overall economy; that is, that it is going to get stronger or weaker, relative to today’s levels, and then proceed to bring in these views into their valuation of companies. Not surprisingly, analysts who are bullish about future economic growth find undervalued companies wherever they look, and analysts who are bearish find the exact opposite.

High real growth = high earnings: Conventional wisdom holds that strong economic growth translates into strong earnings growth and high stock prices. As you can see in Figure 8.2, that is not always the case, especially as we enter an era where companies get larger and larger portions of their revenues and earnings from foreign markets. Thus, you can have strong earnings growth at companies, even as the domestic economy stagnates, or weak earnings growth, as the domestic economy strengthens.

In summary, when analysts are asked to value companies, it is best that they don’t become economic forecasters, partly because it will distract them from doing their company-specific homework, but also because the history of macroeconomic forecasting is not filled with success.

So, how should we deal with real economic growth in valuations? The answer is to do less, rather than more, and focus on the company, not the economy. Specifically, the following are good practices to adopt:

Smooth out forecasts: Assume that you are valuing a mature, cyclical company. You know that its future earnings will be volatile, notwithstanding its mature status, because the economy is volatile. As we argued in the last section, trying to forecast future economic cycles is a pointless and often distracting exercise. Consequently, your valuation will be on more solid ground if you forecast what the operating numbers, including growth, return on capital, and cost of capital, will look like across a cycle and use those numbers in valuing the company. Thus, in Chapter 13, when we value Toyota, a cyclical, auto company, we will normalize current earnings and use a smoothed-out growth rate of 1.5% in perpetuity to value Toyota as a mature company. In doing so, we recognize that earnings growth will be much higher in boom years and much lower in recession years, but lacking the capacity to forecast booms and busts, we believe that valuing with the smoothed-out growth rate will deliver a more robust estimate of value.

Do not bring views on economy into valuation: We all have views on the economy, and it is natural to try to bring those views into valuation, especially with companies that we believe are sensitive to the economy. The danger of doing so, though, is that it makes every valuation that you do a joint function of both what you think about the company and your economic views, making it difficult for others to use your valuation in making investment judgments. So, what should you do? Value the company with consensus views on the economy, even if you disagree with them. After you have valued the company, create a separate analysis based on your views on the economy and what sectors or groups of stocks will be helped or hurt the most, if those views become reality. The latter can be used by investors, if they trust your judgments on the economy, to decide which sectors they should invest in and the former can be used to pick individual companies with each sector.

Focus on the links between economic growth and earnings: For real economic growth to become earnings growth and higher value at a company, several links must fall into place. First, the company must derive a significant portion of its revenues from the economy in question. A Brazilian company, like Embraer, that derives only a small portion of its revenues from Brazil, will not be helped much by high real growth in the Brazilian economy. Second, the competitive landscape should allow the company to have enough pricing power to convert its revenue growth into earnings and excess returns. If you have high economic growth accompanied by cutthroat competition, you could very well see low earnings growth and negative excess returns. Finally, there might be lags in the process, where high economic growth today will result in high revenue growth two or three years down the road, especially in sectors where infrastructure investment is expensive and takes a long time to become operational.

The bottom line again is a simple one. If your job is assessing the value of a company, the more time you spend obsessing about economic growth and researching the economy, the less time you are spending on understanding your company and valuing it well.

The valuation of every company will be affected by the assumptions we make about expected inflation in the future. This section begins by looking at why inflation has such an impact on value, how inflation rates have behaved in the past, and how much and why inflation rates vary across currencies.

As we noted in Chapter 6, valuations can be either nominal or real. If they are nominal, the expected inflation rate is built into both the cash flows and the discount rate. In nominal valuations, expected inflation affects key inputs that we use in our analysis:

The risk-free rate is the interest rate on a default-free bond and thus should have an expected inflation rate built into it. Consequently, the cost of equity and debt that we obtain based on this risk-free rate also have expected inflation components.

The growth rates that we use to forecast future cash flows incorporate both the growth in real output sales and expected inflation. To the extent that higher inflation allows the firm to charge higher prices, the growth rates increase with inflation.

In other words, changing the expected inflation rate affects all aspects of a nominal valuation. That is why the currency in which we do a nominal valuation matters: expected inflation rates can vary widely across different currencies. Figure 8.5 shows the interrelationship between inflation, currency choice, and other valuation inputs.

In a real valuation, neither the cash flows nor the discount rate has an expected inflation component, and real growth has to come from growth in real output. One reason analysts choose to do real valuations is to try to immunize them from changes in inflation. However, expectations about inflation and changes in those expectations can affect even real valuations for the following reasons:

Taxes are usually computed based on nominal income, not real income. To the extent that not all items in an income statement are adjusted the same way for inflation, the tax rate on real income can diverge from the tax rate on nominal income as inflation rises. In most economies, depreciation, for instance, is based on the original price paid for an asset, and the tax benefits from depreciation are therefore fixed at the time of purchase. If inflation accelerates, even a company that can pass the inflation to its customers in the form of price increases might see its after-tax cash flows decline, because the tax benefits from depreciation stay fixed (and are not marked up to reflect inflation).1

In many cases, analysts estimate real discount rates and real cash flows by first estimating the nominal values and then netting out expected inflation from these values. Using higher expected inflation rates results in lower real discount rates and real cash flows.

The inflation rate is not the same for all products and services. To the extent that inflation rates vary across products and services, relative prices change. Therefore, some companies might see cash flows rise at a rate much higher than the general inflation rate, and others might see growth rates in their cash flows that lag inflation.

In summary, the value that we arrive at for a company, if we believe that expected inflation will be 3%, might be very different from the value of that same company with an expected inflation rate of 5%. Inflation is not a neutral item in valuation and changing inflation can have value consequences.

Expected inflation affects risk-free rate and equity risk premiums, two inputs covered in the preceding two chapters. When expected inflation increases, the risk-free rate increases to reflect that expectation, and equity risk premiums might be ramped up as well. Uncertainty about inflation in the future can also make companies more reluctant to invest in long-term projects and thus alter both the level of real economic growth and what sectors it occurs in. Finally, if the expected inflation rate in one currency increases relative to other currencies, we should expect exchange rates to follow, with the higher inflation currency depreciating over time.

If expected inflation rates are constant, incorporating their effect into value is relatively simple. It is because inflation rates change over time and vary across currencies that they can wreak havoc on valuation. This section begins by looking at variation in the inflation rate in the U.S. dollar over time. Then it examines differences in inflation rates across currencies.

Before we look at variation in the inflation rate across time, we must determine how inflation is to be measured. The task is a complicated one, especially when we look at an economy as large and complex as the U.S. At least in theory, the inflation rate should measure changes in how much it costs to buy a representative basket of goods and services from period to period. Not surprisingly, inflation rates vary depending on what we put in the basket. The U.S. has three widely used measures of inflation, with a long history attached to each:

The consumer price index (CPI) measures changes in the weighted average price paid for a specified bundle of goods by consumers. It is a reflection of price pressures at the retail level and includes imported goods and sales and excise taxes.

The producer price index (PPI) measures the weighted average cost of the entire marketed output of U.S. producers. Because it reflects revenues received by producers, it does not incorporate sales and excise taxes.

The Gross National Product price deflator (GNP deflator) measures the inflation rate in the prices of the broader mix of goods and services produced by an economy, rather than the narrower mix used in the CPI.

All three measures share some common problems. The first is that the basket of goods and services that is used to compute inflation is kept stable even as relative prices change. In other words, it is assumed that the proportion of the basket that is oil remains the same, even if oil prices increase significantly relative to other items in the basket. In reality, though, consumers use less gasoline and adjust their consumption to reflect relative prices. The second problem with the basket is that it does not consider implicit costs. For instance, the cost of housing is measured by looking at the cost of renting a house rather than the implicit cost of owning one. To the extent that housing prices are increasing much faster than rental costs are, as was the case between 2002 and 2006, inflation will be understated. Figure 8.6 graphs the behavior of all three measures of inflation from 1921 to 2016.

Note that notwithstanding the differences, the three measures move together over time. Quirks in how they are computed have sometimes caused one measure to lag the other. During much of this period, inflation in the U.S. was benign and ranged from 1% to 4%. Bouts of high inflation occurred in the 1930s and during World War II, but the volatility in inflation accelerated in the 1970s, with inflation rates hitting double digits by the last few years of the decade. The only sustained period of deflation was during the Great Depression, when prices dropped more than 10% a year in 1932 and 1933. Since the 2008 financial crisis, the U.S. has flirted with deflation in a couple of years and the average inflation rate has been low.

All three measures of inflation shown in Figure 8.6 represent actual inflation. In much of valuation, our focus is on expected inflation. Two measures try to capture expectations. One comes from surveys done by the University of Michigan on inflation expectations among consumers. The other can be backed out of the ten-year nominal and inflation-indexed Treasury bond rates:

Figure 8.7 graphs both measures since 2003, when the inflation-indexed Treasury bond starting trading.

The survey numbers and the Treasury-imputed inflation rate closely track the historical inflation numbers. The expected inflation rates backed out of the Treasury rates have been consistently lower than survey expectations but have been better predictors of actual inflation during the periods.

As we noted at the beginning of this section, expected inflation is relevant in valuation because earnings and dividends can be affected by changes in inflation rates. To examine this relationship, Figure 8.8 shows changes in the aggregate earnings on the S&P 500 against the inflation rate (measured using the CPI) over time.

Note that although nominal earnings have increased at higher rates during periods of high inflation, there is substantial noise in the relationship, especially in the years when inflation is changing. Between 1971 and 1980, for instance, the average inflation rate was 8.19%, but earnings increased at a compounded annual rate of 10.57% during the period and earnings growth in the early part of the decade did not keep up with inflation. This resulted in a real-growth rate in earnings of just under 2.5%. Between 1981 and 1990, the inflation rate dropped to 4.47%, and the nominal earnings growth rate was also lower at 4.74%, yielding a barely positive real-growth rate in earnings. In the period since 2008, the relationship between earnings growth and inflation has become even weaker, indicating again that globalization is having an effect.

The higher earnings growth posted by companies during periods of high inflation might seem to indicate that high inflation is good for stock prices and values. To help us examine whether this is, in fact, the case, Figure 8.9 shows the relationship between inflation and changes in the level of the S&P 500 index from 1928 to 2016.

It is difficult to see any pattern here when it comes to stock prices. The S&P 500 increased only about 10% a year during the 1970s, when earnings growth was healthy, whereas the annual return was closer to 16% between 1981 and 1990, when inflation was lower. The complicated relationship between inflation and value should come as no surprise, because inflation is a double-edged sword. Higher inflation might allow companies to increase earnings much more quickly, but interest rates and discount rates also go up—nullifying and, in some cases, overwhelming the effects of higher earnings.

The only reason that the currency you do a valuation in matters is because inflation rates vary across currencies. In trying to compare actual inflation rates in different currencies, we run into two issues. The first is that the way inflation is measured varies widely across countries, making it difficult to compare them head to head. The second is that many countries have government-imposed price ceilings for some products and services, and these fixed prices can skew inflation measures.

In spite of these estimation issues, comparing inflation rates in different currencies is still useful. Figure 8.10 shows actual inflation rates in 2015 and 2016 and the expected inflation rates for 2017 for seven currencies.

Note that inflation rates were highest in Russia and Brazil, moderate in India and Mexico, and low in the U.S., the Euro zone, and Japan during this period. In fact, Japan had deflation in 2016 and it stands to reason that interest rates are also lowest in Japan and highest in Brazil and Russia and that exchange rates reflect the differences in inflation.

The ways in which analysts make mistakes with inflation are different in different parts of the world, largely as a result of their inflation histories. In countries with a history of high or even hyperinflation, analysts often spend too much time trying to get inflation right in valuation, and in countries with a history of low and stable inflation, analysts often forget all about inflation. Looking across both groups, here is a list of inflation sins:

Mixing up currencies: We do not want to rehash our discussion of currencies from Chapter 6, but the only reason the currency you pick can have an effect on the numbers you use in the valuation is through the expected inflation rate that you use. Building on that theme, one of the most dangerous mistakes that you can make in valuation is to mix up currencies, with cash flows estimated in one currency and discount rates measures in another. When Latin American and Turkish analysts, lacking faith in their own high-inflation currencies, decide to dollarize their valuations, they have to be wary because discount rates are easily dollarized, but cash flows, if not dealt with right, might stay in the local currency (often because growth rates are estimated from historical data in local currency terms). That mismatch will lead to overvaluing companies. With stable currency market analysts, the mismatch results from a more subtle problem and occurs when the economy that they are in is going through an inflation transition, from low to higher inflation or vice versa. Again, the problem occurs because many of the numbers underlying cash flows, such as growth rates and returns on capital, come from a low-inflation past and discount rates reflect a high inflation present. They will end up undervaluing companies, as many U.S. analysts did in the 1970s when inflation rates in the U.S. jumped.

Internal Inconsistencies: Expected inflation shows up in almost every input into a valuation, and changing just one, without changing the others, to reflect different inflation expectations can lead to inconsistencies. Thus, higher inflation will translate into higher discount rates and higher growth rates but its effects are not limited to these numbers. Accounting return measures, like return on equity and invested capital, are often in nominal terms and will be affected by the inflation rate in the period of assessment. As we will see in the next section, so will exchange rates and any estimates that stem from forecasts of these rates. It is easy to see how making selective adjustments for changes in inflation in one input (say discount rates) without adjusting the other inputs can lead to internally inconsistent valuations.

Obsession with getting inflation right: High inflation leaves both economic and emotional scars on those who are exposed to it. After periods of unstable inflation, it is natural for analysts to obsess about getting the inflation number right, on the mistaken assumption that if you can get inflation right, your valuations will also be right. Why mistaken? Not only is inflation difficult to forecast, but the effect it has on valuation is muted, if you preserve valuation consistency. Overestimating inflation will cause your cash flows and growth rates to be too high, but this problem will be offset by the fact that the discount rate will also be overestimated.

Ironically, the more work that analysts do in trying to forecast inflation correctly and get that number into their valuations, the more damage they risk doing to their valuations.

The remedies for inflation problems in valuation mirror those given for real economic growth. Less is more, with the following guiding principles:

Currency awareness: The first and most critical step in dealing with inflation in a healthy manner is to be aware of the currency that you are using to do your valuation, with every input that you estimate, from cash flows to growth rates to discount rates. Thus, rather than ask managers what growth rate they expect to see in revenues for the next five years and risk getting a number that is in a different currency, you should ask for a growth rate in a specified currency, and if you are unable to get that number, at least ask for the currency in which the growth rate is denominated, so that you can make the conversion.

Inflation consistency: In the same vein, rather than take inputs as given, especially if they come from external sources, you should consider the inflation rate embedded in the inputs. Thus, if you are estimating historical growth in earnings for the last five years, you should also obtain the inflation rate over that period. Thus, if inflation has shifted, you can adjust the numbers accordingly. As a final check on any valuation, and especially when working in currencies with high and unstable inflation, you should review your inputs to see whether the inflation rate that you have built into them, implicitly or explicitly, is the same.

Inflation offset: Perhaps the best news of all is that getting the inflation numbers right is less important than making sure that the inflation numbers that you are using to forecast cash flows and discount rates match.

If you are still concerned about inflation expectations and how it is affecting your valuation, we have a simple suggestion. Value a company with explicit assumptions about inflation driving your discount rate, cash flow, and growth inputs and check the value. Then change the inflation rate and work through the effect on each of your inputs and then on value. You will notice that if you are consistent, the effects of inflation on value are far smaller than you might have expected. That insight will free you to spend more time on the inputs that truly matter, and less on estimating or forecasting inflation for the future.

As with real economic growth and inflation rates, our views on exchange rates can affect the value that we attach to individual companies. In this section, we will first consider why exchange rates matter, and then we will examine practices in valuation, related to exchange rates, that can pull them off course.

Changes in exchange rates in the past and expectations in the future can make a difference in valuation. For companies with foreign operations, the reported earnings are affected by changes in exchange rates. Favorable movements in exchange rates result in higher earnings, whereas unfavorable movements can result in large losses. Note, though, that what type of movement is favorable or unfavorable depends on the nature of the foreign exposure. If the firm’s costs are all domestic and its revenues are overseas, a weakening of the domestic currency causes earnings to improve. On the other hand, if the firm’s costs are overseas but its revenues are primarily domestic, as is the case for some software companies, a weakening in the domestic currency causes earnings to deteriorate. Expectations of future changes in exchange rates also manifest themselves in differences in expected growth. Thus, the company with foreign revenues gets a boost in growth if we expect the domestic currency to continue to depreciate over time. On the other hand, the growth rate for the company with foreign costs might have to be scaled back for the same expectation. Views on exchange rates can affect even companies with just domestic operations, because their competitive advantages against foreign adversaries will be affected by expectations of exchange rates. If we expect the domestic currency to weaken, a foreign company will be at a disadvantage relative to a purely domestic company. This, in turn, will affect expectations of future growth, margins, and returns for the domestic company.

In emerging markets, views on exchange rates can sometimes play an outsized role, because analysts choose to value emerging-market companies in a foreign currency to make some of their estimation easier. Thus, many Latin American companies are valued in U.S. dollars, because estimating risk-free rates and risk premiums is easier to do than in the local currency. However, this also requires that the future cash flows for these companies be estimated in U.S. dollars, even though the actual cash flows might be in pesos or reais. The conversion of the local currency cash flows to U.S. dollar cash flows requires expected exchange rates (local currency to U.S. dollars) in the future.

Exchange rate views and expectations can affect valuations in one final way. In the face of volatile exchange rates, some companies choose to hedge their currency exposures, leading to hedging costs that lower operating income and value. Other companies, however, make bets on exchange rate movements. If these bets turn out to be right, they add substantially to profits, but if they are wrong, they can cause huge losses. To value a company, we therefore need information on its hedging and speculative bets on the future direction of exchange rates. That information is not always forthcoming.

Until 1971, the world operated in a regime of fixed exchange rates. Changes occurred only when governments chose to devalue or revalue a currency. Because these fixed exchange rates were often incompatible with the underlying fundamentals (inflation, interest rates, and real growth in the economies), black markets sprang up for the most overvalued and undervalued currencies where the exchange rates were very different from the official rates. After the Bretton Woods Conference in 1971, the major currencies were allowed to float (and find a market price), but most emerging markets continued (and some still continue) to maintain a fixed rate structure.

The currencies that have the longest market history are the U.S. dollar, the British pound, the Swiss franc, and the Japanese yen. Figure 8.11 graphs the movements in those currencies, with the dollar as the base as well as a trade-weighted dollar, against major currencies.

Note that a rising value indicates that the currency has strengthened against the dollar, as is the case with the Swiss franc and the Japanese yen, and a declining value is an indication of the currency weakening against the U.S. dollar, as is the case with the British pound. There are two things to note. The first is that different currencies often move in different directions. During this period, the dollar strengthened against the pound but weakened substantially against both the Swiss franc and the yen. Within each currency, there are long cycles of up and down movements. With the Swiss franc, for instance, the dollar weakened through 1980, strengthened for the first half of the 1980s, and reverted to weakness in the second half of the decade. Some of this movement can be traced to the underlying economic fundamentals—the strengthening of the yen reflects Japan’s rise as an economic power during the 1970s and 1980s—but some of it reflects deliberate government policy. The U.S. actively encouraged dollar depreciation after 2001 to improve the competitive position of U.S. companies in the export market. Since 2008, there have been extended periods of strengthening and weakening in the currency, often with no fundamental reasons.

Figure 8.12 shows the U.S. dollar versus the euro, which replaced the individual EU currencies (such as the French franc and the Deutsche mark) in 1999.

After the euro was introduced in January 1999, it initially suffered depreciation, reaching a value of $0.85/euro in June, but it has gone through an extended period of appreciation against the U.S. dollar. The high was just over $1.575/euro in April 2008 but the last decade has seen the rate drop to $1.05/euro in December 2016 before it strengthened again in 2017.

Some emerging-market currencies have opened up to free-market pricing over the last two decades. They have been much more volatile than the developed-market currencies shown in Figures 8.11 and 8.12. Figure 8.13 graphs the Mexican peso, Indian rupee, the Brazilian real, and the Chinese yuan from 1995 to 2017.

The Brazilian real lost almost 80% of its value against the dollar between 1995 and 2002 but more than doubled its value between 2002 and early 2008. In the 2012–2015 time period, it reversed direction and lost almost half its value against the dollar, before stabilizing in 2016 and 2017. The volatility in these rates should not come as a surprise. The short-term movements are caused by political instability in these markets and economic variability over time. The long-term movements of these currencies, though, are more reflective of differences in inflation, with the rupee, peso, and Brazilian real all losing half or more of their value against the dollar between 1995 and 2017, whereas the Yuan strengthened against the dollar over that same period.

Although the conventional wisdom is that the currencies of mature economies like the U.S., Japan, and Western Europe (with similar inflation) do not go through sharp contortions, the market crisis of 2008 that we highlighted in the preceding chapter might lead to a rethinking. Figure 8.14 shows the movements in the U.S. dollar versus the euro, yen, and Brazilian real from September 12 to October 16.

Although the volatility in the Brazilian real might be predictable, the sharp devaluation of the euro (which has lost almost 8% of its value against the dollar) and the rise in the yen (up about 10%) is a sign that volatility in exchange rates is not restricted to emerging-market currencies.

A few decades ago, when most companies derived much or all of their revenues domestically, analysts avoided thinking about or dealing with exchange rates. Those days are behind us, because most companies generate some or much of their revenues from foreign markets, and even those that do not have costs in other currencies. Thus, currency avoidance is no longer an option, because movements in exchange rates can affect revenue growth, operating margins, and even discount rates. Unfortunately, the way analysts deal with exchange rates exposes them to valuation mistakes, with the following practices contributing to the errors:

Current exchange rate extrapolation: In a surprisingly large number of valuations, analysts when valuing companies with revenues or costs in a foreign currency use today’s exchange rate to convert future cash flows. This is especially true in currencies where there are limited or no futures markets and the defense that is offered by analysts is that they have no choice. In the process, though, they are embedding inconsistent inflation assumptions into their valuations, and here is why: Assume that you are valuing an Indian company, say Bajaj Auto, in U.S. dollars and have computed a cost of capital in U.S. dollars. Assume also that you have forecasted the cash flows in Indian rupees and that you proceed to convert those cash flows into U.S. dollars, using the current exchange rate ($/rupees). By doing so, you have embedded a rupee inflation rate of 4%−5% in your cash flows while computing a cost of capital with U.S. dollar inflation rate of 1.5%−2%. You should not be surprised if you get too high a value for Bajaj Auto.

Exchange rate views: At the other end of the spectrum are analysts who have strong views on future exchange rates and are determined to bring them into the valuation. This problem gets worse if you are hiring and paying a forecasting firm that delivers exchange rate forecasts, because you now feel obligated to use them in your valuations. So what? Assume that you are valuing Bajaj Auto again in U.S. dollars, but that you believe that notwithstanding the higher inflation rate in rupees, that the rupee is likely to appreciate over the next five years. If you use these forecasted exchange rates, you will make Bajaj Auto’s valuation even higher but the peril that you face is that your conclusion is a joint effect of your views on the U.S. $/Rupee exchange rate and the company. In fact, if it is the former that is driving your conclusion, there are far easier ways for you, as an investor, to make money than risking it on an automobile stock; you would just make your bets on the exchange rate futures market.

Currency risk: If the essence of discounted cash flow valuation is that you discount expected cash flows at a risk adjusted rate, it seems reasonable that investors should demand higher expected returns when investing in companies that have an exchange rate risk embedded in them. Based on this reasoning, you would expect the cost of equity of Coca-Cola, which derives almost half of its revenues overseas, to be higher than the cost of equity for Monster Beverage, which derives a far higher percent of its revenues in the United States. That reasoning, though, misses a key component of risk measurement, which is that investors should measure risk in a company by looking at how much risk it adds to their portfolios, rather than risk standing alone. Even if you invest only in U.S.-incorporated companies, the effects of exchange rate risk are surprisingly diffuse, with a stronger dollar hurting some U.S. companies and helping other U.S. companies in your portfolio. In fact, as investors gets more diversified and global, perhaps using exchange traded funds and index funds, you could argue that currency risk is becoming a diversifiable risk and should not therefore command a discount rate adjustment. There is one other reason to be cautious about hiking discount rates to reflect currency risk. Exchange rate risk is the most hedged macroeconomic risk in the world, and many companies use forwards, futures, and options to insulate their earnings from exchange rate movements.

As our forecasting tools get more sophisticated and data gets more plentiful, falling into the trap of believing that you can forecast exchange rates and bringing them into your valuations is easy to do. If your mission is to value companies, not play pricing games with exchange rates, you will be undercutting that mission, if you make yourself an exchange rate forecaster.

Keeping their views on exchange rate out of their individual company valuations is often difficult for analysts. To prevent these views from hijacking valuations, we suggest that you follow a few simple rules:

Use purchasing power parity: One of the first theorems that you learn in any session on exchange rates is the notion of purchasing power parity, which is that exchange rates will change to keep purchasing power equalized across currencies. Thus, higher inflation currencies will weaken over time against lower inflation currencies, and the change in the exchange rate can be written as a function of the differential inflation rate between the two currencies. For instance, the expected exchange rate n periods from now, for a foreign currency (FC) against the U.S. dollar ($), can be written as a function of expected inflation in that currency and expected inflation in the U.S.:

The pushback that you will get is that purchasing power parity, although it might hold in the long term, does not in the short term, but that critique does not stand up to scrutiny. Even if you believe that exchange rates will move in a direction different from the one predicted by purchasing power parity, remember that the only way in which you can stay inflation-consistent in your valuations is by assuming that exchange rates move over time to reflect inflation differences. What if you have forward or future market forecasts of exchange rates? Because these are market-set rates, there is nothing wrong with using them, as long as you then use inflation rates that are consistent with the forward rates. Thus, if the forward market is predicting a 3% depreciation in a currency against the U.S. dollar, your inflation rate in that currency should be roughly 3% higher than the U.S. dollar inflation rate.

Keep exchange rate views separate: If you strongly believe that exchange rates will move in a specific direction over time, either because of your views of economic fundamentals or because of momentum, keeping that view out of the valuation is best for reasons that we stated in the last section. In fact, given the sorry track record of exchange rate forecasting, this might not only save you money but also reduce your valuation errors.

Look at exchange rate risk through investor eyes: In our discussion of discount rates in Chapter 2, we argued that they should be estimated from the perspective of the marginal investors in the company, rather than your eyes or mine. That is the basis for the argument that it is only non-diversifiable risk that you incorporate into the discount rates, not total risk. Bringing that perspective into looking at exchange rates is helpful, because it focuses attention on who the marginal investors in the company are and how they perceive exchange rate risk. To the extent that the marginal investors are globally diversified institutions (BlackRock or Fidelity, for instance), we would argue that exchange rate risk can cause earnings to be volatile and stock prices to move, but it does not translate into higher discount rates. That conclusion might be challenged if you are valuing a closely held, small public company or a private business, but it is a debate that is worth having.

You might want to consider using one final tool in dealing with macroeconomic variables. If your company is particularly exposed to macroeconomic movements (in real growth, inflation, or exchange rates), you could use probability distributions for these variables and value your company using simulations. Thus, rather than value a cyclical company with a point estimate of real economic growth, you could be more realistic and come up with a distribution of value for your company, given a distribution for real economic growth.

The value of every company is affected by what we expect to happen to the overall economy, expected inflation, and exchange rates in the future. Given this centrality, it is surprising how haphazard analysts are when it comes to making reasonable assumptions about these variables. Some make implicit assumptions through the company-specific numbers they use and are unable or unwilling to make these assumptions explicit. Others build all their forecasts on last year’s numbers, thus building whatever happened last year with the real economy, inflation, and exchange rates into their future estimates and value. Still others make strong assumptions about the future path of macroeconomic variables, and through these assumptions have large effects on value.

As you review the chapter, you should be seeing a pattern. With real economic growth, inflation rates, and exchange rates, there are two suggestions for dealing with all of them. First, no matter how strongly you feel about future movements in these variables, you should avoid bringing those views into company valuations. You can use your macro views to make judgments on whether you should invest in equities, which sectors to invest in, and what geographies to concentrate on, as part of the asset allocation process. Second, macro variables affect all of your valuation inputs; that is, growth, cash flows, and discount rates, and being internally consistent is more important than being right on these variables.

___________________________

1. Assume that a firm has $100 million in EBITDA, $40 million in depreciation, and no interest expenses. Furthermore, it faces a marginal tax rate of 40% on its income. The firm reports $36 million in net income and $76 million in cash flows prior to reinvestment (net income + depreciation). Now introduce an inflation rate of 10% into the analysis, and assume that the firm can raise the prices of its products at the inflation rate. EBITDA rises to $110 million, but depreciation stays frozen at $40 million. The firm now reports net income of $42 million and cash flows of $82 million. If we convert the latter into real numbers, the real EBITDA is $100 million, the real net income is $37.8 million, and the real cash flow is $73.8 million—$2.2 million less than it used to be.