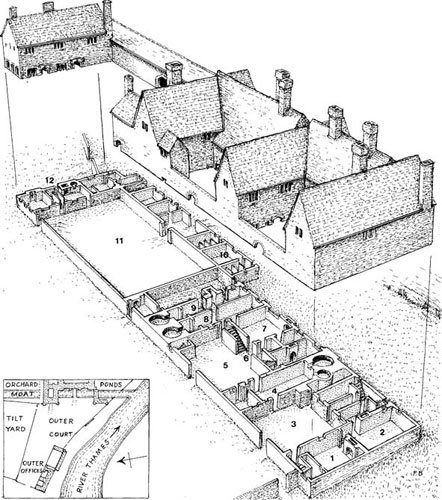

From the medieval period through to the late nineteenth century, bakehouses and similar places that produced smoke, smells, potential fire risks and a bustle of activity at unsocial hours were located in the outbuildings of most great houses. This was certainly the case at Hampton Court, where a block of outer offices was built in the Outer Court, the present lawned area extending from the entrance gates along to the main west front of the palace (fig. 3).

Construction started in the spring of 1529 at the east end, incorporating materials from Wolsey’s old bakehouse in the park, while new timber frames were prefabricated at Reigate by a carpenter called John Wylton.1 These were carted to Hampton Court, then erected to form ‘a ryshe house [for rushes] … a grete bakehouwse and a prevey bakehouse with a crosse howse betwn them … a brede howse, a panlever [?] and a scalding house’. The yard walls, chimney-stacks and ovens were built in brick for additional security and fire protection, while the roofs were covered in earthenware tiles by one “William Garret in November 1529. All this is clear evidence that the whole of this large building, measuring some 300 feet (91m) by 90 feet (27m), was constructed within some seven months.

![]()

3. The houses of office Situated in the Outer Court (the present lawned area in front of the Great Gatehouse), this timber structure of 1529–30 was built with brick ovens and chimney-stacks to accommodate the Scalding House for preparing poultry and rabbits, the Bakehouse for breadmaking, and the Woodyard for preparing and storing wood, fuel and rushes.

1, 2. Scalding Rooms (?)

3. Poultry Yard

4. Privy Bakehouse

5. Bakehouse Yard

6. Stairs up to granaries

7. Bread House (?)

8,9. Great Bakehouse

10. Stables for purveyors’ horses

11. The Woodyard

12. The Woodyard Offices

The west, or outer, end of these offices was occupied by the Poultry and Scalding House, which was controlled by the sergeant of the poultry and his clerk. All the birds required for both the King and his household were purchased around London and beyond by two yeomen purveyors, using a scale of set prices which was revised from time to time as the economy dictated. Those confirmed by the Lord Great Master and the Counting House for William Gurley, purveyor of poultry, on 27 March 1545, were as follows:2

Swannes, the piece 6s |

|

Cranes, Storke, Bustard, the piece 4s |

8d |

Capons of gress [fat], the piece |

22d |

Capons good, the piece |

14d |

Capons, Kent, the piece |

8d |

Hennes of gress … the piece |

7d |

House Rabbetts, the piece |

3d |

Rabats out of the Warren … |

2½d |

Ronners [free-range rabbits], the piece |

2d |

Wynter Conies, the piece |

2½d |

Herons, Shovelard [shovellers], Byttorne |

20d |

Mallards, the piece |

4d |

Kyddes, the piece 2s |

|

Pegions, the dozen |

10d |

Large and fat geese from |

|

Easter till Midsummer, the piece |

7d |

Geese of gress from Lamas till 22th day, the peice |

8d |

Eggs from Shrovetide, till Michaelmas, the hundred |

14d |

Eggs from Michaelmas till Shrovetide, the hundred |

20d |

Peacocks and Peachicks |

16d |

Grewes [grebes], Egretts, the peice |

14d |

Gulls, the peice |

16d |

Mewes, the peice |

8d |

Godwits, the peice |

14d |

Dottrells, the peice |

4d |

Quails, very fat, the peice |

4d |

Cocks, the peice |

4d |

Plovers, the peice |

3d |

Snytes [snipes], the peice |

2½d |

Larks, the dozen |

6d |

Teales, the peice |

2d |

Wigeons, the peice |

3d |

Sparrows, the dozen |

4d |

Butter, sweet, the pound |

3d |

Although some of these items are still cooked and eaten today, many have not appeared on English menus for centuries. Relatively few descriptions of their basic preparation survive, and I include some of them here. As a Venetian visitor to England around 1500 recalled, ‘It is a truly beautiful thing to behold one or two thousand swans upon the river Tames … which are eaten by the English like ducks and geese’3 Although eaten in most great households, particularly around Christmas and the New Year, large swans were usually fairly tough and could have a fishy taste. The cygnets made much better eating, and are still served with great ceremony by Mr Swan Warden at the annual feast of the Vintners’ Company of London.4 Among the large wading birds, the heron, bittern and shoveller were all highly regarded, the bittern in particular having much the flavour of the hare, and none of the fishiness of the heron. In his Castel of Helth of 1541, Sir Thomas Elyot, diplomat and writer, stated that these birds ‘being yonge and fatte, be lyghtyer digested than the Crane, and the Byttour sooner than the Hearon … All these fowles muste be eaten with muche ginger or pepper, and have good old wyne drunk after them.’5 The stork was certainly a much rarer bird, but, according to the medical writer Tobias Venner’s Via Recta ad Vitam Longam of 1620, it ‘is of hard substance, of a wilde savour, and of very naughty juyce’!6 Both the snipe and the godwit, smaller waders, made very good eating. According to Sir Thomas Browne, physician and writer, Godwits … [are] accounted the daintiest dish in England; and, I think, for bigness, of the biggest price.’7 As for ducks, the wigeon and the smaller teal were greatly appreciated too – ‘Teal for pleasantnesse and wholesomeness excelleth all other water fowle’,8 commented Venner.

The appearance on the list of seabirds such as mews (common gulls), gulls and puffins may surprise us, but in fact they had all been eaten for centuries. The puffin’s flesh tasted so fishy that one writer in 1530 described it as ‘a fysshe lyke a teele’, and the Church actually classed them as fishes which could be eaten in Lent.9 In Cornwall puffins were chased out of their holes near the cliffs using ferrets and then, being ‘exceeding fat, [they were] kept salted, and reputed for fish, as coming neerest thereto in taste’.10 Prepared in this way, they were considered something of a delicacy. Gulls, meanwhile, were caught in nets and fattened during the winter in poultry yards, where they were ‘crammed with salt beef ready for the table’.11

Of the wild land birds, the most impressive was the great bustard, the largest wild bird in Europe. Before it became extinct in this country around 1860, it was remembered as having particularly delicious flesh, weighing some fifteen pounds or more, with a six-foot wing span.12 The much smaller quail, plover and dotterel were equally desirable, especially the first of the three – fat and tender, it was lured into nets using a whistle called a quailpipe.13 In contrast, the delicate yet nourishing larks were taken either by a small hawk called a hobby, or by using a mirror and a piece of red cloth to distract them until they were netted. In Shakespeare’s King Henry the Eighth the Earl of Surrey alludes to this practice when taunting Cardinal Wolsey about his red cardinal’s hat:14

If we live thus tamely,

To be thus jaded by a piece of scarlet,

Farewell nobility! Let his grace go forward

And dare us with his cap like larks.

The lark was considered to be ‘of all smale byrdes the beste’, whereas sparrows were ‘harde to digest, and are very hot, and stirreth up Venus, and specially the brains of them’, Sir Thomas Elyot tells us.15 Presumably this is why they were a luxury at the palace, while remaining a poor man’s food, netted and caught beneath sieves from the earliest times through to the middle of the twentieth century.16

Of the tame birds, many of the geese, hens and pheasants, for instance, were fed in the poultry yards attached to some of the palaces, as well as being purchased in vast numbers. Peacocks and peachicks made very impressive dishes at table, but had to be eaten when still quite young. Dr Andrew Boorde, physician and traveller, states in his Dyetary of Helth (1542) that ‘yonge peechyken of half a yere of age be praysed, olde pecockes be harde of dygestyon’, while Henry Buttes complained of their ‘very harde meate, of bad temperature, & as evil juyce. Wonderously increaseth melancholy, & casteth, as it were, a clowd upon the minde’.17 However, when a year-old bird was recently roasted at Hampton Court, it was found to be very toothsome – somewhere between a chicken and a pheasant in flavour and texture. To prepare it for the kitchen, the Tudor cooks first cut its throat and hung it with a weight tied to its heels for two weeks in a cool place.18 Turkeys were also available at this period: they were brought into Europe from Mexico and Central America about 1523–4, and into England at about the same time by the Strickland family of Boynton near Bridlington in the East Riding. The crest adopted by the Stricklands for their coat of arms showed a white turkey cock with a black beak and red wattles – probably representing the colouring of those early birds. Listed as one of the greater fowls by Archbishop Cranmer in 1541, the turkey soon gained an excellent reputation, being ‘very good nourishment; restoreth bodily forces; passing good for such as are in recovery; maketh store of seede; enflameth Venus’. For preparation, they were simply hung overnight and cooked quite fresh.19

Using money advanced to them by the clerk for the coming month, the Hampton Court purveyors would purchase their poultry as required. In the case of shortages, they could compulsorily requisition supplies from members of the Poulterers’ Company of London, paying the agreed prices. The Company was also obliged to buy back at the same rates any supplies that the palace purveyors found they didn’t need. In return for these impositions, it was agreed that the purveyors would not take any poultry from within seven miles of London, and that they would not purchase any birds offered to them by nobles or gentlemen.20 Most of the poultry was probably unloaded in the poultry yard so as to be ready for preparation before five in the morning.21 The sergeant then checked it for quality and quantity.22 If it contained any bad stuff, he rejected it and reported the purveyor to the clerks of the greencloth for punishment, while if it was of overall poor quality he could call in the clerks comptroller, who would reduce the price accordingly. As soon as it was accepted, the poultry was carried into the scalding house, where great pans of water would already be boiling over the fires. If the birds were dipped in for half a minute, the feathers could easily be plucked out by pulling them against the grain.23 Since this process heated the carcases, it could make them go off within a day. Long experience had made this common knowledge, so the birds were plucked immediately before being cooked; those for late-morning dinner were delivered fresh to the larder by 8 a.m., and those for early-evening supper by 3 p.m. They were probably delivered drawn, but with their heads and feet in place to make it easier to tie them on to the spit, and with their major organs still inside for use by the cooks in specific recipes.

![]()

To the east of the Poultry, in the centre of the outer offices, lay the bakehouse.24 At Hampton Court at this time the sergeant of the bakehouse was John Heath. He it was who had provided all the ‘hard tack’ biscuits for the King’s siege of Boulogne in July 1544, and personally served there as a standard-bearer in the army, for which he earned an additional two shillings a day. Assisted by his clerk, he supervised the provision of all the bread required for the court.25 The supplies of wheat were either purchased from outside or brought in from the royal estates by two yeomen purveyors, each load being delivered by cart or by barge and then measured by the bushel (64 pints, 36 litres); the sergeant or his clerk would always ensure that all of it was sweet and good for baking.26 Some of the six ‘conducts’ (labourers) would carry it up the two broad staircases from the yard into the granaries, where the yeoman garnetor cleaned it and turned it, as necessary, to prevent it being spoiled by mildew or pests. This officer was also responsible for sending the wheat to be ground at the mills; he would make sure to check that the same weight that went out as grain returned as meal, for the King never surrendered a percentage of the meal as toll, but paid for the miller’s services in cash.

On its return, the meal was boulted, or sieved, by the labourers. A coarse sieve first removed the bran, which the sergeant sold to the avener for feeding the King’s horses. The remaining meal was either used to make ‘cheat’, or wheatmeal bread, or put through a very fine sieve to produce an almost white ‘mayne’ flour for making small loaves of the highest quality, called manchets. For general use the yeoman fernour (a baker in charge of the ovens or furnaces) would season the flour, prepare the leaven or yeast, make sure the dough was not too wet, check its weight in his balance both before and after baking, and heat the ovens in the great bakehouse. John Wynkell, the yeoman baker for the King’s mouth, made the ‘mayne, chete and payne de [bread of] mayne’ for the royal table quite separately in the privy bakehouse. In 1546 the King had granted him the additional office of bailiff and collector of revenues for the lands of dissolved Leicester Abbey, in both Leicestershire and Derbyshire.27

The bulk of the Bakehouse’s production was the cheat bread, the wholemeal loaves that in 1472 are recorded as weighing about 1lb 9oz (725g) each.28 Around 200 or more messes of cheat were required every day to serve with meals, along with a minimum of 150 additional loaves to provide the breakfast, afternoon and supper-time snacks for those who had bouche of court. Similarly, over 700 manchets were required for the upper household’s meals, and further supplies for bouche-of-court staff.

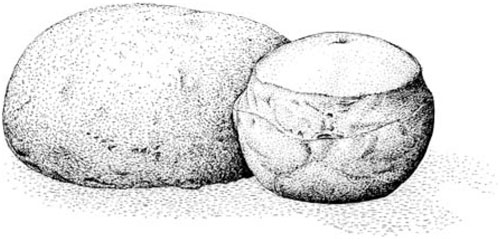

To make the cheat bread, the wholewheat flour was tipped into a deep wooden dough trough, and a hole scooped in the middle. Into this was poured a solution of old sourdough mixed with lukewarm water; next, it was mixed until it thickened enough to resemble pancake batter, as Gervase Markham tells us in his The English Hus-wife of 1615.29 The batter was then covered with more meal and left to ferment overnight to form a spongy mass. In the morning, the remaining meal was kneaded in with a little warm water, yeast and salt to form a dough. Kneading by hand was far too laborious and slow for operations of this scale, and so it would either have been worked beneath a ‘brake’, a long beam secured to a bench by means of a strong iron shackle, or folded into a large clean cloth and trodden under foot. It is possible that the canvas ‘couch cloths’ (table cloths) purchased for the Bakehouse in the 1540s were used for this purpose.30 Having been left to rise for a while the dough was then divided into individual loaves, which were weighed, worked or moulded into shape, and left to rise once more, ready for baking in the ovens.

To make manchet bread, fine boulted white flour would be similarly tipped into the dough trough and have a hollow scooped out of it, but instead of sourdough, a barm or liquid aleyeast would be poured in – the sergeant purchasing this as required.31 Having been mixed with salt and warm water, it was kneaded up on the brake or under foot, allowed to rise, then kneaded once more and divided up into individual loaves or rolls. Once each loaf had been weighed and shaped into a smooth ball, it was lightly rotated with the left hand while a knife in the right would slash it all the way round. A stick or a finger was then used to poke a dimple into it from top to bottom. This preparation gave the manchets their characteristic shape and quality. With the sides of the loaf slashed, the dough was free to rise upwards, giving a lighter, taller end product, much better for table use and also occupying less of the valuable oven space. The dimple, meanwhile, prevented the fermentation gases from forming unwelcome bubbles under the upper crust.

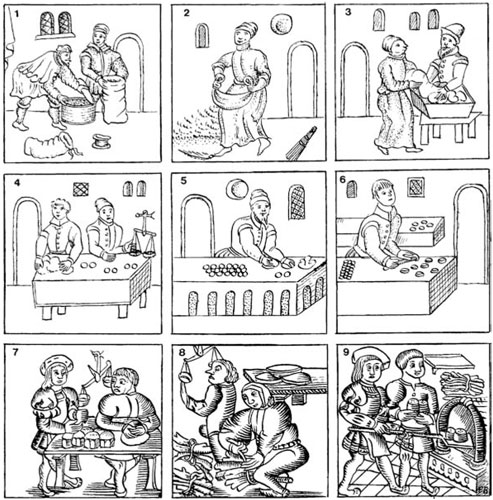

4. Tudor breadmaking These drawings based on the 1596 ordinances of the York Bakers’ Company and on a mid sixteenth century assize of bread (bottom row) show the processes which the bakers and their labourers would have carried out here:

1. Measuring the wheat on its arrival, using a bushel measure and a ‘strike’ to level its surface.

2. Boulting the ground meal through a piece of canvas to remove the bran. Note the goose-wing and the brush for sweeping up the flour.

3. Mixing the dough in a trough.

4. Weighing manchet dough.

5. Moulding manchet loaves.

6. Cutting the manchets around the sides with a knife.

7. Moulding cheat loaves.

8. Tying up faggots for the oven. This labourer is wearing a linen coif, a close-fitting cap tied beneath the chin, to keep his head clean and warm.

9. Setting the bread into the oven.

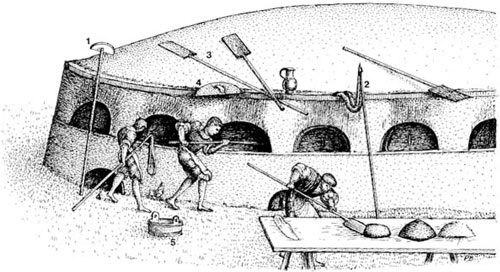

The ovens used both in the bakehouses and in the main kitchens were of the traditional wood-fired kind. To house each oven, tons of insulating sand and rubble were encased within the brick walls of the bakehouses. Inside this mass, the large, flat circular floor of each brick-built oven was surrounded by a low wall, which supported a shallow dome of tiles set edge to edge to form a fireproof chamber. The only entrance was by a doorway at one side – the lintel of which was often pierced by a flue to carry away the smoke and steam from inside, but for the largest ovens in the palace kitchens this was replaced by a huge smoke-hood. To heat the oven, bundles of light branches were used, dry hawthorn being particularly good for this purpose because when ‘bound into faggots … and burnt in ovens and in furnaces … they be soon kindled in the fire, and give a strong light, and sparkleth, and cracketh, and maketh much noise, and soon after they be brought all to nought’.32 This kind of fuel, in the quantities needed by the palaces, cost £40 a year in the 1540s.33

Having been set alight, probably by being held over an open fire at the end of a long iron oven-fork, the flaming faggots would be either placed to one side or scattered over the oven floor and allowed to burn out, their flames licking the roof of the oven as they reached towards the open door. Once the brick structure had absorbed sufficient heat, sparks would fly at the mere rubbing of a twig across its dome; a little flour sprinkled on its floor would quickly turn dark brown, but not burst into flame. The bakers may then have taken a long iron bar with an L-shaped end, called a rooker, to rake out most of the ashes, and they would certainly have used a hoe, a semi-circular blade on the end of a long handle, to remove most of the remaining ashes and loose dust. They would then have dipped a long mop called a mawkin into a tub of water and swabbed out the final ashes, thereby introducing a degree of moisture into the oven before inserting the bread.

5. Tudor bread A cheat loaf of coarse wheatmeal flour, and a manchet of fine unbleached white flour, showing its characteristic dimple on the top and encircling slash.

The fully risen loaves, probably arranged on broad planks or work-boards, were then brought to the oven; each one would be scooped up on to the spade-shaped blade of an oven peel and skilfully set in place within the oven’s dark interior. Now the oven door, probably made of sheet iron, was propped in place and its edges cemented with thick mud or clay, thus totally sealing the new batch until it had finished cooking. Only then was the door removed and the loaves taken out with the peel to cool, finally to be placed in the bread room for storage. Freshly baked bread was con sidered very unhealthy, all those who enjoyed its fine taste and texture fully expecting soon to be suffering from painful heartburn. As Dr Andrew Boorde advised:

Hote breade is unholsom for any man, for it doth lye in the stomacke lyke a sponge, haustyng undecoct humours [causing indigestion]; yet the smell of newe breade is comfortable to the heade and to the harte. [Bread must be] a daye & a nyght olde, nor it is not good when it is past 4 or 5 dayes olde, except the loves [loaves] be great … Olde bread or stale bread doth drye up the blode or naturall moyster of man, & it doth engender evyll humours, and it is evyll and tarde of dygectyon [slowly digested].34

From the bread store, the clerk of the bakery recorded its distribution to the various offices that would use it. Most went to the Pantry, for the direct use of the household, while smaller quantities went to the Wafery and the Saucery to be used as ingredients in their products. Each day 102 loaves were also sold to the officers of the leash for a farthing each, for feeding the King’s greyhounds.35

![]()

The third part of the outer offices, nearest to the palace, was occupied by the Woodyard.36 This came under the responsibility of John Gwyllim, the sergeant of the woodyard. In addition to his wages, Gwyllim enjoyed a considerable income from grants made to him by the King. These included the lease of prize wines, and the collection of custom duties as well as the subsidy of taxes and duties from the port and town of Bristol, and the lease of four former Whitefriar’s tenements near St Dunstan’s in Fleet Street, London. He also undertook the unlikely role of purveyor, buying hops and stockfish worth some £335 for Calais and Boulogne in 1545.37 He and his clerk supervised the delivery of wood and rushes for the court, following the same accounting procedures as those described for the Bakehouse. In the 1540s they were supplying:38

in Wood for fewell, over and above Bouche of Court |

£440 |

||

in Rushes and straw, by estimacion |

£60 |

||

in necessaries, as Planks, Boords, quarter |

£10 |

||

th’expences of Purveyors and other officers |

£6 |

13 |

4d |

£516 |

13 |

4d |

The fuel listed here, used to heat all the public rooms in the palace as well as to maintain all the fires in the kitchens, consisted of faggots, which were made from the smaller branches so burned fairly quickly, and talshides, timbers of a more substantial size that could maintain the fires throughout the day. Because trees and branches do not come in standard sizes, a quick and efficient method of measuring them had to be developed so that they could be fairly distributed according to the ordinances. Each log appears to have been about four feet (1.2m) in length and classified by its cross-section, as determined by measuring its girth according to a system which was later formalised by Queen Elizabeth.39 The smallest size – for example a number one talshide, could either be a complete log of about sixteen inches’ (40cm) girth and about five inches’ (13cm) diameter, or of nineteen inches’ (48cm) girth when split down the middle lengthways from a seven-and-a-half-inch (18.5cm) diameter log, or eighteen and a half inches’ (47cm) girth when quarter-split from a ten-inch (25cm) diameter log. There was then a sliding scale extending up to a size seven; the first four sizes would be:

6. Bread and pastry ovens This detail based on the painting of The Field of the Cloth of Gold (c. 1545) shows Henry VIII’s bakehouse or pastry staff operating a bank of ovens using (1) a hoe to scrape the ashes out of the ovens, (2) mawkins to mop them out, (3) peels for putting the food in the ovens and taking it out, (4) iron oven doors and (5) a tub, probably to hold the clay for sealing the doors.

Size |

Complete log |

Half-split |

Quarter-split |

1 |

16in (40cm) |

19in (48cm) |

18½in (47cm) |

2 |

23in (58cm) |

27in (68.5cm) |

26in (66cm) |

3 |

28in (71cm) |

33in (84cm) |

32in (81cm) |

4 |

33m (84cm) |

39in (99cm) |

38in (96.5cm) |

In this way the volume and burning capacity of each log could be readily measured for purchasing and accounting purposes, and also for meeting the needs of the particular users. In addition, faggots and talshides were supplied to all those who had bouche of court: dukes were allowed eight faggots and ten talshides per day; bishops, senior nobles, the Lords Chamberlain and Privy Seal, the Queen’s maids and the Counting House, six faggots and eight talshides each; knights and senior members of the household staff, four of each; the Wardrobe and household officers, two of each; and the sergeants and gentlemen officers, one of each. Altogether, at least 400 faggots and a similar number of talshides would have been distributed around the palace on each winter’s day.40 The numerous smoking chimneys must have looked very impressive – the placing of the King’s own apartments and gardens to the south-east of the palace, though, ensured that the prevailing south-west winds would keep them largely smoke-free.

As for the rushes, they would most probably have been the common rush, Juncus, whose clumps of tapering tubular green stems grow two feet (61cm) or more in height in most wet heaths and fields in this country. Their main use then was as a floor-covering. Even though many rooms in the palace were fitted with mats made of bulrushes – plaited into four-inch (10cm) strips, then stitched together to make them up to the required size, John Cradocke having obtained a lifetime monopoly in 1539 for supplying them to all the royal palaces within twenty miles of London – loose rushes continued to be strewn.41 Writing to Wolsey’s physician, Erasmus had described English floors as having accumulations of up to twenty years’ rushes, stinking with the vilest mass of filth and rotting vegetable matter, but neither archaeology nor any contemporary evidence can confirm this.42 Nicolo di Favri of the Venetian embassy more accurately observed: ‘In England, over the floors they strew weeds called “rushes” which resemble reeds … Every eight or ten days they put down a fresh layer; the cost of each layer being half a Venetian livre, more or less, according to the size of the house.’43

To keep the rushes clean, the three grooms who were responsible for strewing them in Edward VI’s Privy Chamber each morning had to sweep away all those that were matted, while the description of Queen Elizabeth’s presence chamber strewn with rushes (which he mistook for straw) given by Paul Hentzner of Brandenburg, travelling tutor to a Silesian noble, and Ben Jonson’s of ‘ladies and gallants languishing upon the Rushes’ show them to have been a clean and relatively high-status floor-covering.44 Certainly, a monarch as fastidious as Henry VIII would never have allowed masses of stinking rushes to lie about his palace. In practice, the Juncus type of rushes provide a warm insulating layer, quiet to walk upon, and give any room a delightfully moist and piquant scent, as anyone knows who has attended the rush-bearing service in St Oswald’s Church at Grasmere in the Lake District.45 In addition, they help to contain the dust, grit, grease and small litter, leaving the floor quite clean when they are swept up with a broom, and so making them the ideal covering for rooms such as the Great Hall at Hampton Court.

Rushes were also used for other purposes. If their outer layer was peeled off, leaving only a narrow strip to support the fine spongy pith, they could be used as wicks for pricket candles or oil lamps. Henry’s Privy Purse expenses included payments ‘for a potell of salet [salad] oyle 2s 6d; for a bottell and for Rushes to brenne [burn] wt. the saied oyle 3d’; and if dipped in tallow, they formed rush lights and tapers.46 Dry rushes could be used to light fires or lanterns, or even to make pallets or mattresses for servants.47 A number of junior officers, such as the under-clerk comptroller, were provided with ‘lytter and rushes for [their] paylette’, while Henry VII’s household regulations include instructions for shaking up a layer of litter – suggesting the manner in which the rushes may have been prepared for the purpose – and laying it between two layers of canvas to form a base for his feather bed.

Running parallel to the river, at the back of the Woodyard, were the stables where the purveyors of the Poultry, the Bakehouse and the Woodyard could keep their horses. By the 1880s these stables had fallen into ruin and over the course of the following decades, along with every other building in this block, they were demolished and the whole area grassed over, leaving no visual evidence that a major domestic building had ever occupied the site.