Virtually everyone concerned with the domestic management of Hampton Court, along with every item of its food, drink and fuel, had to enter the main palace buildings from the Outer Court by way of the Back Gate (no. 3). As they approached, they would be directly observed by the administrative staff working in the counting house up on the first floor of the gatehouse. At the gateway itself, once the great oak doors had been swung back, they would be challenged by one of the porters. This man was responsible to William Knevet, the sergeant porter who had served as a captain at the siege of Boulogne, and his job was to prevent

any Vagabonds, Rascalls, or Boyes [entering] in at the Gate at any time; and that one of [the porters] shall three or four times in the day make due search through the House, in case that negligently at any time, any Boyes or Rascalls have escaped by them … and put them out again … the said Portes shall have vigilant eyes to the Gate, that they doe not permitt any kind of Victualls, Waxe-lights, Leather Potts, Vessels Silver or Pewter, Wood or Coales, passe out of the Gates, upon paine of losse of three dayes Wages to every of them as often as they offend therein.1

To enforce their authority, the porters carried their traditional porter’s staff, and also had the use of a pair of small stocks, which were transported from palace to palace in the Greencloths’ carriage.2 They were probably based in the small room to the right of the Gate, beneath the staircase there (no. 4). From their doorway, not only could they check every person and vehicle entering and leaving the palace, but they could also watch the door of the jewel house only a few feet away, and by scanning the courtyards see anyone entering the boiling house door to gain access to the main kitchens.

![]()

The four ground-floor rooms to the left of the gate were occupied by the Jewel House (no. 6). Considering the fabulous value of Henry VIII’s gold, silver and bejewelled artefacts as well as his superb gemstones, this would appear to be a ludicrously insecure and exposed location. But in fact, all those really valuable items were kept in a far safer ‘secret’ jewel house in the King’s apartments, deep in the heart of the palace. This jewel house by the gate was used only to store the less valuable domestic pieces of gold, silver, coinage and so on. Although physically within the household offices, the Jewel House was administered quite independently, the master of the jewels being directly responsible to the King for all items placed in his care; he would issue and receive many whole and broken silver vessels as instructed by the Treasurer of the King’s household, presumably including those intended for the use of the courtiers in the Great Chamber and other rooms of states.3

To perform these duties, the master of the jewels had two waiters, a clerk (and his servant), and a yeoman and a groom, who shared a servant. The yeoman and groom were particularly charged with the safety of the silver and so forth when it was in transit, the latter carrying the boxes to their department’s ‘charyet’, or wagon, packing them and securely tying them down, and then, with the yeoman, guarding them as they were moved from one place to another. For such moves, smaller items and boxes were packed into great leather-covered iron-bound strongboxes called standards. Just before Candlemas on 2 February 1530, Henry had sent ‘three or four cartloads of stuff, the most part lokked in great standerds’, to the disgraced Wolsey at nearby Esher; then just a few months later, on 11 May, he purchased two more standards for £3 1s 8d to carry quantities of gold and silver plate from York Place, the Cardinal’s former London residence as Archbishop of York, back to Hampton Court.4

![]()

Beyond the archway of the Back Gate, the walls fall back to each side, to provide convenient ‘parking bays’ for carts and so on unloading their goods into the stores and offices which lined this first courtyard, the Greencloth Yard (no. 11). Proceeding down the left, or north, side of the yard, the first door in the corner gave access to a spiral stair leading up to the comptroller’s lodgings, while the second led into the jewel house. The next two doorways, each with a narrow window to one side, were the entrances to the Comptroller’s cellar and the King’s coal house (nos 9 and 10), constructed within the area of the moat, which ran through this area up to 1530.

At this period the word ‘coal’ was used to describe both the charcoal made by baking wood in kilns and the ‘sea-coal’ dug out of the ground. It is probable that the ‘Coals in the year, by estimacion £324’, purchased by the Scullery and Woodyard were charcoal, used in cooking stoves, in small portable dish-warmers called chafing-dishes and in small portable room-heaters called stoves.5 In the 1540s the ‘coal’ was delivered by the ‘quarter’, a measure of eight bushels (about 290 litres) and was probably stored in the cellars here until required by the various kitchen offices or by the King, the Queen or Princess Mary – courtiers were not provided with any supplies to heat their rooms.6 For the King’s Chamber, it was put in baskets containing one third of a quarter, some three and a half cubic feet (0.1 cubic metres); each basket would be checked for volume and then marked by the clerks comptroller.7 This ‘coal’ was probably charcoal: if it had been sea-coal it would have weighed around two hundredweight (100kg), and would have been too heavy for the groom porters to conveniently carry up to the chambers. It is also notable that none of Henry VIII’s fireplaces were provided with the iron grates that were essential for coal fires.

If sea-coal was used at Hampton Court at this time, as suggested by a layer of coal excavated from the cellars in 1984, it is far more likely to have been used to fuel the large room-heating stoves.8 Introduced from the Continent, these had their fireboxes and flues clad with finely moulded glazed earthenware tiles, to work rather like giant storage radiators. One of these was certainly in use at Whitehall (formerly Cardinal Wolsey’s residence, then known as York Place), where green-glazed tiles bearing the initials ‘HR’ were excavated from the bathroom area in the 1930s, and there was probably a similar example at Hampton Court. When Baron Waldstein visited the palace in 1600, he found that ‘In the Queen’s bathroom there is a stove, and in its upper part a certain metal which the English call by the extraordinary name of sea-coal; by heating this the room itself is warmed.’9

![]()

Returning to the Back Gate, we now go along the right, or south side of the Greencloth Yard. In the corner by the Gatehouse were two doorways: the first was the staircase to the counting house, up to which the White Sticks, the clerks of the kitchen and spicery, the purveyors and others would have passed on their way up to the greencloth, while the second led into the counting house’s ground-floor room. Next, half-way along the wall, came the door into the spicery office (no. 12), where the chief clerk of the Spicery supervised not only the spicery office itself but also those of the Chandlery, the Confectionary, the Ewery, the Wafery and the Laundry. Within five days of each month’s end, this clerk had to make a list, or ‘parcel’, of all the provisions he had bought in, noting any sales on the back of the list and then passing it to the cofferer together with any money received.10 In addition, he had to complete his annual returns to the Greencloth within two months of the year’s end, or else be fined three months’ wages.

As far as the spices were concerned, these included all the popular medicinal and flavouring ingredients of the period. Andrew Boorde listed the most common as ginger, pepper, nutmeg, mace, cloves, cinnamon, saffron, liquorice, grains of Paradise (the seeds of Aframomum melegueta, a West African plant of the ginger family) and galingale (another spice similar to ginger) to which may be added caraway, aniseed and coriander.11 Some of these were distributed to the kitchens, the saucery and the confectionary in their whole form, but if required as a powder they were ground by William Hutchinson, the yeoman of the spicery, probably using a bell-metal or marble mortar, and sieved to ensure that they were of sufficient fineness.12 Some indication of the furniture and equipment he may have used may be gathered from the 1599 inventory of the spice house of Sir Thomas Ramsey, Lord Mayor of London:13

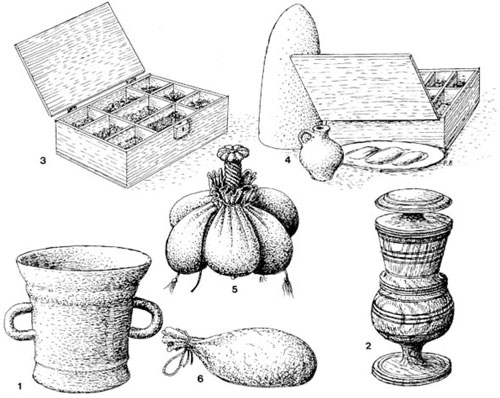

7. Spicery Equipment These drawings, based on contemporary illustrations, show (1) a bronze mortar for reducing the spices to a fine powder and (2) a mortar mill in which the spices were grated between iron plates and would then collect in the lower bulbous section. The lockable wooden spice-boxes (3 and 4) ensured that their expensive contents were kept secure in the kitchen. The ground spices were hung up in the spice-purse with its leather bags (5), or in bladders (6), ready for use.

Itm. an iron beame and skales … |

10s |

Itm. two brasse morters wayinge 164lb (74kg] |

|

net at 4d ob [ha’penny] |

£3 1s 6d |

Itm. two olde presses |

|

Itm. an olde counter |

|

Itm. two small paire of balance … |

|

Itm. two boxes, 3 barrells … |

|

Itm. 3 spice treyes … |

|

Itm. two piles of brasen waghts poize |

|

[weight] 31lb [14kg] at 4d ob |

12s |

Itm. browne paper, and white in the cupboard … |

3s |

The Spicery also dealt with items we would not now describe as spices, such as dates, figs, raisins and other dried fruits, sugar and other groceries, as well as fresh fruits such as the apples, pears, quinces, oranges and lemons used by the household.14

![]()

Next door lay the chandlery (no. 13), where the clerk of the spicery maintained records of how much wax was brought in every day, and how much of it was distributed as candles and so on both for general household use and, weekly, to those who received such items as part of their bouche of court. According to the Black Book of 1472, the sergeant of the chandlery used both large and small balances, weights, pans, a travelling trunk, hot irons, and a ‘carriage’ and a pack-horse to carry the long coffers containing the lights of all sizes – in short, everything required to make and distribute torches and candles as needed.15 To do this he was assisted by three yeomen. The first deputised for him in lighting the King’s chamber and presenting the expenses for these lights to the ushers there. The second yeoman had to help make the lights and distribute them to each person according to their bouche of court entitlement, and then supervise two grooms to collect all the unburnt pieces of the larger lights from every lodging in the palace by nine each morning. The third yeoman, ‘cunnynge in waxemakinge’, assisted them in these tasks, and also supervised the lights in the Great Hall and chambers. Finally there was a page who did all the dirty and unskilled work such as cleaning the Chandlery, fetching the wood and charcoal, and carrying equipment and stores to and from the wagon whenever the court was on the move.

Most of the lights were made of beeswax, which at £400 a year, not including the bouche-of-court supplies, was extremely expensive.16 The largest lights were torches. These were made by dipping lengths of tow, coarse hemp or flax fibres or fine linen rags into the wax and rolling them to form columns probably some three feet (90cm) long and around three-quarters of an inch (2cm) in diameter. A number of these, perhaps six, would then be waxed together around the top of a wooden shaft to form a torch. Such costly lights were provided only for the King, the nobles and the highest officials.17 Links (a shorter kind of torch) were made in a similar manner, but instead of being mounted on an integral shaft they were spiked on portable iron cressets mounted on long poles; Henry VIII’s inventory listed 1000lb (454kg) of links for cressets, plus twenty cressets, in one of his stores.18

To light the King’s chambers, square blocks of wax with a central wick were used, 14lb (6.3kg) of fine wax being purchased to make these ‘quarriers’ for the King in 1531.19 They were delivered from the chandlery every day, and their remains, along with the ends of the torches, were collected by the grooms of the chamber who passed them to the groom porters for return to the chandlery for remelting.20

For general good-quality lighting, the senior members of the court used one pricket candle every winter’s day. This consisted of a peeled rush or a plaited wick over which warm wax was poured until it was probably an inch (2.5cm) or more in diameter, so that it could be stuck on to the spike of either a wall-mounted or a portable pricket candlestick.21 Smaller candles made in the same way were called sizes, most courtiers and household officers receiving two of these each day in winter. The cheapest candles used at the palace were called white lights. These were distributed by weight, a duke receiving a pound (450g) a day, for example, and each courtier and upper household servant eight ounces (225g). In the late fifteenth century the royal household was still using pieces of bread to hold the smaller candles; the first yeoman of the chandlery would draw loaves from the Pantry for this particular use in the King’s Chamber, later returning those that remained unused.22 Henry VII’s ‘grand porter’ had kept a ladder near the Great Chamber ‘redie to sett upp sises withall on a plate; which plate ought to be hanged on the uppermost side of the arras’ at frieze level.23 By the sixteenth century candlesticks with sockets were already in regular use; ‘two Candlesticks of silver gilt with sockettes’ weighing over twenty-four ounces (700g) were recorded at Hampton Court in 1547, for example.24

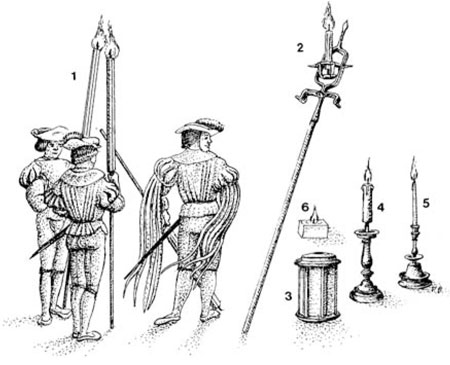

8. Tudor Lighting The Chandlery made the long beeswax torches (1) used only for the royal family and nobles (shown in BM Add MS 24098); the shorter ‘link’ (2) was mounted on a long pole for more general use. It also made the candles for wooden lanterns (3), pricket candlesticks (4) and socket candlesticks (5), as well as quarriers (6) – the large square night-lights used for the King’s Privy Chambers and other royal rooms.

![]()

Beyond the chandlery, in the corner of the Greencloth Yard on the south side of the inner gateway, a doorway led into the rooms of the clerk comptroller (no. 15). Just opposite, and entered from the gate passage, is a room identified in the 1674 inventory as the Bottle House, but its use in the 1540s is uncertain (no. 17). In 1545 the groom of the bottles was John Mawde, to whom the King had granted the lease of the watermills at Carleton and Burton in Yorkshire.25 Mawde was responsible to the sergeant of the cellar for carrying wine in large leather bottles slung from the sides of his bottle-horse, and for ensuring that none was lost or dispensed along the way. Since the storage of beer and wine in glass bottles only began on a large scale in the Elizabethan and Stuart periods, there would appear to have been little need for a bottle house in the palace in the 1540s, and this room probably had another use when first built. It may well have been associated with the adjacent dry fish house and salt store, with which it communicated directly by means of an internal door. Certainly there would have been a great need for such a cool, dark store with no south-facing windows to keep supplies of salt beef, especially during the winter months.

Salt beef formed an important part of the diet of virtually every Tudor household, and it enjoyed a sound reputation. Andrew Boorde wrote:

Beef is good meat for an Englishman so be it the meat be young; for old beef and cow-flesh doth engender melancholy and leprous humours. If it be moderately powdered [salted], that the gross blood by salt may be exhausted, it doth make an Englishman strong, the education of him with it considered. Martylmas beef, which is called ‘hang beef in the roof of the smoky house is not laudable. It may fill the belly, and cause a man to drink, but it is evil for the [kidney-] stone, and of evil digestion, and maketh no good juice.

Salt beef was usually prepared around Martinmas, 11 November, when the cattle were still in good condition after their summer grazing and before they had to be fed on expensive hay and peas. As Thomas Tusser, in his Five Hundred Points of Good Husbandry (1577), advised:27

November [for Easter] at Martilmas, hang up a beef,

For stall-fed and pease-fed, play pickpurse the thief.

With that and the like, ere grass-beef come in,

Thy folk shall look cheerly, when others look thin.

The first task when salting beef was to decide whether it was to be dry-salted or wet-salted. The first method involved rubbing a mixture of common salt, bay salt (a salt with large crystals made by evaporating sea-water by the heat of the sun in the Bay of Biscay), saltpetre (potassium nitrate) and coarse brown sugar into the meat. Plain salt would have tended to dry out the surface of the beef, making it as hard as a board, but mixing it with saltpetre helped the salt to penetrate and gave the beef an appetising pink colour, while the sugar softened it and so counteracted the hardening effects of the salt. When large quantities of salt beef were being prepared, this rubbing and turning process was frequently replaced by wet-salting, for which the meat had only to be soaked in a brine. Wet-salting was certainly carried out at Hampton Court – the palace was provided with ‘ranges for the cawdren to stand upon for the seething and boiling of bryne for the larder’.28 The beef was first cut up into pieces weighing 2lb (900g) each, which was enough for one mess for four people, and then immersed in the brine as described above, until it was completely impregnated. During this process the salt made it shrink, but, as the Privy Council informed Lord Hertford when he was mounting the 1544 expedition against Scotland, even if this caused the meat to weigh less, it still contained ‘as much feeding, and more, than two pounds of fresh beef when it had been soaked and boiled ready for the table. For storage, the beef was packed into ‘pipes’, large wooden casks of 105 gallons (about 478 litres) capacity, each of which held four hundred pieces, enough to provide 1,600 individual servings.29