From the inner gateway, the Pastry Yard looks almost square (no. 19). It is surrounded on the north, east and west sides by Henry VIII’s kitchen offices of 1530–2, while to the south the earlier lodgings of Wolsey’s Base Court extend away eastwards, leaving a wide, open paved passage leading up towards the Great Hall.

This passage was essential for allowing daylight into the lodgings, but it also provided an effective firebreak between the kitchen offices and the main residential part of the palace. More importantly, it provided a direct route for carting such items as barrels of beer down to the cellars beneath the Great Hall and for the bread bearers to carry the manchet and cheat loaves from the bakehouse to the bread room near the buttery; the passage would also have been used to bring the talshides and faggots from the wood-yard to feed the palace’s numerous fires, and the torches, links and candles from the chandlery to provide its illumination. As the main service passage, it must have been a constantly busy thoroughfare, its security ensured by being under constant surveillance from the clerk comptroller’s rooms.

![]()

Starting from the inner gateway and proceeding clockwise around the yard, the first door led via a staircase to the offices of the clerk of the kitchen, directly over the gateway, and to those of the Scullery (no. 20), where the sergeant and two clerks of the scullery and woodyard kept their accounts. The next door gave access to the fish larder, described in the building accounts as the dry fish house (no. 18).1 As fish was the main fasting-day food, eaten every Friday and Saturday and throughout Lent, it was important that the palace always had supplies ready to hand.

Purchases of fish were made by the clerks comptroller and the sergeant of the acatery, probably with his clerk and John Hopkins, yeoman purveyor of sea-fish.2 In Elizabeth’s reign these officers were responsible for providing all the ‘ling, coddes, stock-fish, salt-herring, salmon, salt eeles, grey-salt and white-salt’ kept in store in the dry fish house, the yeoman of the salt store delivering them to the main kitchens and larders as required.3 It made good sense to store the ‘Bay Salt … £20’ and ‘White Salt £13 6 8d’ here in the dry, for they would have deteriorated rapidly in the steamy boiling house and damp wet larders.4

9. Ling This large variety of cod formed the bulk of the salt-fish eaten at Hampton Court.

For the King’s and Queen’s own use there were salt eel, salt lamprey, salt salmon and ‘organ ling’.5 The latter was the best kind of ling and the largest were caught around Orkney; one writer in 1603 described a superior person as ‘Differing as much from other people … as Stockfishe or poor John from the large organe ling’.6 Much came into this country from Norway and Iceland, where, Andrew Boorde tells us, ‘the people be good fyshers, much of theyr fyshe they do barter wyth English men, for mele [meal], lases [laces] and shoes’.7 Quantities would be carried from the dry fish house into the wet larder a few days before each fish day, to soak there in tubs of water in readiness for cooking in the kitchens.

Next door to the dry fish house, a staircase went up to the first floor to a landing which led left into the pastry and saucery office (no. 21) and right into the confectionary (no. 22). The sergeant and clerk of the pastry, assisted by a yeoman, was responsible for the administration and accountancy of both the main pastry – where pies, pastries and tarts were baked – and the saucery. In the 1674 lodging list the Saucery is located in the hall-side dresser office, but although this is a large room it is unlikely that important officers such as the clerk of the kitchen and his companions would have wished to share their office with a mere yeoman, especially one who was constantly busy grinding, sieving and mixing various odoriferous ingredients, and so the saucery may well have been located elsewhere.

![]()

The saucery concentrated on making the thick condiments eaten cold with the meat and fish, rather than the hot sauces made from the internal ingredients of the hot dishes cooked in the kitchens, although the yeoman of the saucery may have helped in their preparation by doing odd jobs such as grating bread. To make the sauces, the Saucery annually purchased ‘in mustard, vinegar and vergeuice [an acid liquor obtained from sour fruit such as crab-apples] £50 … in herbs for sauces, by estimacion £4’, as well as drawing supplies of bread from the Bakehouse, spices from the Spicery, and vinegar made by the Cellar from their ‘feeble or dull wines’.8

The Saucery’s most important product by far was mustard, which was ‘bruised and ground with vinegar [as] a wholesome sauce, meet to be eaten with hard, gross meats, either flesh or fish’.9 Henry Buttes, in his Dyets Dry Dinner of 1599, described it as ‘Good sauce for sundrie meates, both flesh and fish; English Mustard; that is, much tart’.10 First, the mustard seed was crushed, using either a pestle and mortar or perhaps a stone or iron ball in a bowl; then it was mixed with strong wine vinegar, strained into a pot, and tied down beneath a parchment cover until required for use. Next in importance came greensauce, which was sometimes made with sorrel or gooseberries as in later periods, but also with herbs such as parsley and mint. It was especially recommended to accompany fresh fish such as halibut and turbot, for which it might be eaten along with mustard, since they went well together.

![]()

Across the landing from the saucery lay the confectionary – just a single room, but the one responsible for producing the most elaborate and expensive of all the foods prepared in the kitchen. At this period sugar was still a most expensive luxury food. Columbus had carried sugar-cane from the Canaries to the New World on his second voyage in 1493, the Spanish first cultivating it in San Domingo, using the labour of imported African slaves, and bringing their first shipments back to Europe around 1516. They then went on to expand its production in their colonies in the Caribbean, Mexico and Paraguay, and along the Pacific coast of South America. The Portuguese carried out a similar programme in Brazil, and were shipping sugar back to Lisbon by 1526. Although the sugar was refined to some extent in its country of origin, it was still too impure for high-quality use and so was further refined in northern Europe. Antwerp being the leading centre for this activity.

In early sixteenth century England sugar cost around 3d or 4d a pound (450g), but its growing popularity and scarcity saw it rise to 9d or 10d by 1544, when its price had to be checked by royal proclamation.11 In the same year London established its first refinery. Here the sugar was dissolved and boiled in a lye of ashes or lime, the scum was skimmed off, and the syrup clarified with white of eggs. It was then placed in cone-shaped pottery moulds covered with a layer of wet clay, from which the water slowly dripped through the sugar, removing the remaining molasses. When this process was finished, the sugar cones were knocked out of their moulds and left in a warm room to dry out. The finished cones weighed anything from three to fourteen pounds (1.3–6.3kg) and were almost as hard and white as crystalline marble. It was not until 1551 that Captain Thomas Wyndham returned to England from Agudin, Morocco, with the first-ever cargo of sugar to be brought into this country by an English ship direct from its country of origin. The Tudor taste for sugar intensified so that the trade rapidly expanded, and by 1585 London had replaced Antwerp as the leading refinery centre in Europe.

Although the Spicery could acquire its sugar in good condition, it was very difficult to keep it that way because sugar readily absorbs moisture from the atmosphere and soon turns into an unpleasant sticky syrup. My own experience of Hampton Court’s kitchens has brought this home to me: on one occasion, sugar-work that had dried to rock-hardness over some months began to dissolve and to weep syrup after only a day’s exposure to the kitchens’ damp winter air. Exhibiting great good sense and practicality, the architect who designed the kitchen offices placed the confectionary in the warmest and driest place in the whole palace – directly over the pastry ovens, a mass of some 80 cubic yards (61 cubic metres) of masonry that would have been continually fired up whenever the court was in residence. This constant source of dry underfloor heating made the confectionary ideal for sugarwork.

Most of the sugar, spices and dried fruits used in the Confectionary, along with some of the finished confectionery, was bought from one of the two Venetian galleys that used to arrive in Southampton each year, where one of them would unload and the other would keep its cargo intact for trading with Flanders on the return journey. The use of corporate hospitality to promote business was already a well established practice in the sixteenth century, and on one of these occasions the captain of the Venetian flag-galley provided the King and his court with a sumptuous entertainment. A large platform on the deck had been decorated with tapestry and silk, and on either side were four tables, each bearing dishes of every sort of confection for the three hundred guests. Henry passed down the centre and up to the poop deck, where he tasted sponge cakes and other sweetmeats, and the remainder was distributed among the nobles. Meanwhile, those at the tables below enjoyed their share of the confectionery and wine, their hosts giving them the glass vessels they had used, all of fine Venetian workmanship, as leaving presents.12

Since sugar was so expensive, the confectionary was one of the few kitchen offices that produced food especially for the King. It was supervised by the sergeant of the confectionary, who received his sugar and spices from the Spicery. With these ingredients he made ‘confections, garquinces [quince marmalade], plaatess [sugar plate], sedes [comfits] and all other spycery nedefull; dates, figges, raisonnes, greate and smalle for the Kinge’s mouthe, and for his household in Lente seasone; wardens [cooking pears], pearys, apples, quinces, cherryes, and all other fruytes after their seasonne’.13 These fruits were all supplied at no charge from the King’s orchards, in particular the moated Privy Orchard just to the north of the kitchens and the Great Orchard beyond, while ‘blaunderelles (white apples), pippins and other fruits were bought in by the sergeant; it was also his responsibility to prepare any fruit given to the King as presents. Some are mentioned in the Privy Purse expenses:14

27th June, 1530 |

keeper of the gardens at York Place, reward for bringing cherries to Hampton Court 4s 8d |

10 Aug., 1530 |

paid to the gardeners of Hampton Court for bringing pears and damsons to the King 7s 6d |

16th Aug., 1530 |

to the gardener of Richmond in reward for bringing filberts and damsons to the King at Hampton Court 4s 8d |

14th Oct., 1530 |

Hobart’s servant for bringing oranges and citrons to the King at Hampton Court 4s 8d |

17th June, 1531 |

James Hobart, pomegranates, oranges, lemons to Hampton Court 20s |

The sergeant was assisted by a yeoman, who made confectionery for the King, the Great Chamber and the Great Hall, and so had to be ‘well learned in the makeinge of confections, plates, gard-equinces, and others, safely and cleanly to keepe, and honestly to minister it forthe at all tymes of the King’s worship, and make trewe answere therof by weyghtes inward and outward’.15 There was also a groom who helped to make and serve the confections, cleaned the confectionary and undertook general fetching and carrying, as well as a pack-horse man who transported fruit, spices and confectionery as required.

At the end of their meals, after their table had been cleared, or ‘voided’, the King and Queen would stand up to take sugar-coated spices and a spiced wine called hippocras to warm their stomachs and aid digestion. Even on ordinary days, the spice plates used were of silver, silver gilt or gilded glass, which the sergeant drew from either the Counting House of the Jewel House, filled with spices and passed to the usher of the King’s Chamber for service to the King, the groom later collecting the plates and bringing them back to the confectionary. If less important people were to be served, the spice plates were of pewter, drawn from the sergeant of the scullery. For state occasions, the royal spice plates were of the greatest magnificence – here is a description of one listed in Henry VIII’s inventory:16

Item one spice plate of greystone the fote and brymme garnysshed with silver gilt standing upon four antique heddes with homes and a cover of silver and gilt garnyshed with three heddes videlicet [namely] an Agathe a pursleyne [porcelain] and of mother of Emerrauld and garnished with Roses and flower deluces [fleur-de-lis] of counterfete stones … with a man in the toppe thereof with a staff and a Sheilde weyieng togethers 68oz [1.9kg].

On important ‘days of estate’, when the court displayed its grandest ceremonies, the royal spice plates were filled with a pound and a half (700g) of spices – a pound (450g) was normal on ordinary days or for the service of dukes, earls and bishops. The royal confectioners had been making aniseed, coriander, fennel and ginger comfits for centuries, using the ‘pannys, basyns, and ladylles that he maketh his confections with dayly’.17 Most of the smaller, dry spices served at the ‘void’ were coated in sugar as comfits; pippins eaten with caraway comfits being especially recommended.

Sugar was also used to preserve fruits, very much as it is today. The fruit was lightly cooked in syrup and then sealed with the syrup in ceramic jars. The peels of oranges and lemons, meanwhile, were treated in a similar way to form ‘succade’, more usually known as sucket in Tudor England. As Andrew Boorde advised, ‘Oranges doth make a man to have good appetite, and so do the rinds if they be in succade.’18 Other fruits were preserved in the form of very stiff, sticky pastes which could be served cut up into small slices. These were first brought to England from Portugal, where quinces, marmelos in Portuguese, were mixed with sugar and scented substances such as rosewater, musk and ambergris, and then cooked until their natural pectin made the mixture thicken into semi-solid marmelada. This was poured into shallow wooden boxes – the most convenient means of packing it for preservation, sale and transport. In 1560, Lord Robert Dudley bought a ‘brick of marmelade 2s 4d’ for a banquet at Eltham.19 In England, the Portuguese marmalades were soon being reproduced, using either home-grown quinces or a variety of other fruits such as warden pears, damsons, apricots, peaches, oranges and lemons.

10. Comfit-making Spices such as caraway, coriander and chopped ginger were given a smooth, hard sugar coating by being repeatedly hand-stirred in a swinging copper pan set over a chafing dish of glowing charcoal. Sugar syrup was added little by little, until it had built up the required thickness around each seed or piece.

Another very popular Tudor sweetmeat was made by pounding blanched almonds with rosewater and sugar to form a smooth, stiff off-white paste called marchpane – the early word for our modern ‘marzipan’. The recipe produced flat, glazed discs with raised rims, their broad surfaces being ideal for decoration such as gilding or ornate sculptures made of marchpane paste, sugar plate and cast sugar figures. In their most extravagant forms these were served as ‘subtleties’ – wonderfully impressive sculptural models that would be brought in with great pomp at the start of each course.

Some ‘subtleties’ were made of wax. The one that preceded the first course at the Sergeant’s Feast given to Philip II of Spain and Queen Mary on 16 October 1555 in Inner Temple Hall was ‘A Standing Dish of wax, representing the Court of Common Pleas, artificially made, the charge therof £4.’ Preceding the second course, there was ‘A standing Dish of Wax, to each mess one, £4.’20 And Anne Boleyn’s coronation feast held in Westminster Hall on 1 June 1533 had included’ subtleties and shippes made of waxe, marvylous, gorgeous to behold.21

Other subtleties were probably made of sugar, the confectionary making ‘A George on Horseback’, a suitably magnificent theme to introduce the first course at Henry VIII’s Garter dinners.22 This must have been cast from a set of moulds about a hundred years old – ‘a soteltee Seint-Jorge on horseback and sleyng the dragun’ had been served at the first course of a royal feast recorded about 1440, the third course continuing the legend with a subtlety of ‘a castel that the King and the Qwhene comen in for to see how Seint Jorge flogh [flew?].23 Some of the other moulds used in the confectionary had probably been inherited from Cardinal Wolsey’s kitchens. In 1527 he had served a subtlety of the great medieval St Paul’s Cathedral, with its soaring spire; and in 1562 Queen Elizabeth received a similar marchpane bearing a model of St Paul’s as a New Year’s gift from her surveyor of the works, along with ‘a very faire marshpaine made like a tower with men and artillery in it’ from her yeoman of the chamber, and a ‘faire marchpane being a chessboarde’ – another Wolsey speciality – from her master cook.24

![]()

11. A Marchpane Mould This early sixteenth century marchpane mould bears the IHC monogram of Jesus, a popular motif in the decorative arts of this period, and the inscription, cut in reverse, ‘An harte that is wyse will obstine from sinnes and increas in the workes of God’.

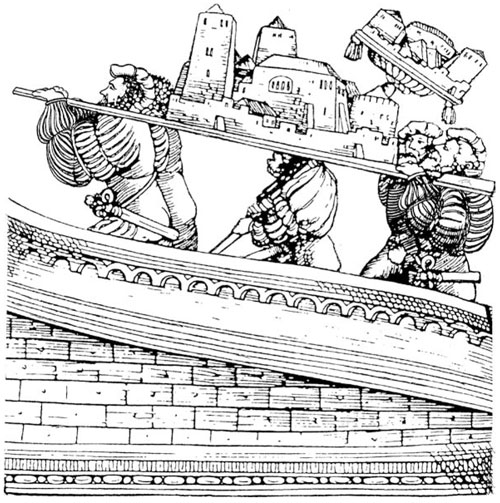

12. Subtleties The main decorative feature of any Tudor feast was a’subtlety’, which could be a model of a building, a saint, a worthy or a virtue, with appropriate mottoes. Here in Hans Springlee’s print, The Battle before the Rouanne, from The Triumph of Maximilian (1526), two subtleties are being carried up to the Emperor. The print provides us with rare evidence of their scale and appearance, and the manner in which they were presented.

The finest account of Tudor confectionery comes from George Cavendish’s biography of Cardinal Wolsey, in which he describes the preparation and service of a magnificent feast for the reception of the French ambassadors at Hampton Court in October 1527.25 It is well worth quoting at length. First, Wolsey called for his principal officers of his house, as his steward, Comptroller, and the Clerkes of his kitchen – whome he commaundyd to prepare for them a bankett at Hampton Court, and noither to spare for expences or travell to make them suche tryumphant chere as they may not only wonder at hit here, but also make a gloryous report in their contrie, to the Kynges honour & that of the Realme … [Also, they sent for] all the expertest Cookes besydes my lordes that they could gett in all Englond where they myght be gotten to serve to garnysshe this feast. The purveyors brought and sent In suche plenty of Costly provysion as ye wold wonder at the same. The Cookes wrought bothe nyght & day in dyvers subtiltes and many crafty devisis where lakked nother gold, Sylver ne other costly thyng meate for ther purpose …

Nowe was all things in a redynes and Supper tyme at hand. My lordes Officers caused the Truppettes to blowe to warne to Supper And the seyd Officers went right discretly in dewe order And conducted thes nobyll personages frome ther Chambers unto the Chamber of presence where they shold Suppe And they beyng there caused them to sytt down ther servyce was brought uppe in suche order &c Aboundaunce both Costly & full of subtilties wt suche a pleasaunt noyce of dyvvers Instruments of musyke tht the French men (as it semyd) ware rapte in to an hevenly paradice … devysyng and wonderyng uppon the subtilties … Anon came uppe the Second Course wt. so many disshes, subtilties, & curious devysis wche. ware above an [hundred] in nomber of so goodly proporcion and Costly that I suppose the Frenchemen never sawe the lyke, the wonder was no lesse than it was worthy in deade. there were Castelles wt. Images in the same, powlles [St Paul’s] Chirche & steple in proporcion for the quantitie as well counterfeited as the paynter shold have paynted it uppon a clothe or wall. There were beastes, byrdes, fowles of dvers kyndes And personages most lyvely made & counterfet in dysshes, some fighting (as it ware) wt. swordes, some wt. Gonnes and Crosebowes, Some vaughtyng & leapyng, Some dauncyng wt. ladyes, Some in complett harnes lustyng [fighting] wt. speres, And wt. many more devysis than I am able wt. my wytt to discribbe. Among all oon I noted there was a Chesse bord subtilly made of spiced plate wt. men to the same, And for the good proporcyon bycause that frenche men be very experte at that play my lord gave the same to a gentilman of fraunce commaundyng that a Case shold be made for the same in all hast to preserve it from perysshyng in the conveyaunce therof to hys Contrie.

13. The Waddesdon Court Figures The sugar figures made in the Confectionary probably bore a close resemblance to these early sixteenth century oak figures which originally stood around the frieze of the dining room at Waddesdon Court, Stoke Gabriel, in Devon. This selection shows (top) the Christian Worthies – King Arthur, Charlemagne and Godfrey de Bouillon – and (bottom) the Pagan Worthies – Hector of Troy, Julius Caesar and Alexander the Great, as described in the introduction to Caxton’s Morte de ‘Arthur of 1485. They may now be seen in the Torquay Museum.

To make many of the figures a new kind of sugar plate was introduced, one that dried to a pure matt-white finish ideal for receiving decoration. The first recipe for this sugar plate to be published in England was in Girolamo Ruscelli’s The Secretes of the Reverend Maister Alexis of Piedmont of 1562, but by this time it had probably been in use in the royal confectionary for many years. Instead of having to be boiled, the sugar was simply ground to a fine powder and then sifted to produce the equivalent of today’s icing sugar. Once mixed with a natural vegetable substance, gum tragacanth, as a binder, and lemon juice and rosewater for flavour, it was transformed into one of the most versatile of all confectionery media.

The moulds used for this paste were used bone-dry – just dusted with a little finely powdered sugar, starch or spice to prevent the sugar plate from sticking inside them. To make a round fruit such as an orange, for example, pieces of the soft, pastry-like mixture could be pressed into each section of a plaster, or a pottery mould, the edges trimmed level with a knife and brushed with a little gum tragacanth solution to make the parts stick together; then the mould would be reassembled and after a while the completely spherical fruit turned out into a box of freshly sifted flour, which would hold it in shape until it had hardened. The sugar plate could also be cast in shallow wooden moulds, perhaps only an eighth of an inch (3–4mm) in depth; the surplus would be cut off with a knife, and then the sugar plate would be turned out by holding the mould upside down above a worktop, at a slight angle from the horizontal, then sharply banging down the lower end to make the sugar plate drop out face upwards. The moulding could then be carefully draped over a ‘former’, where it would set into the shape of part of a limb, a torse, a shield – or whatever was being made. Once perfectly dry, the edges of each piece would be neatly trimmed and stuck to other pieces using a strong gum-tragacanth and icing-sugar ‘cement’, in much the same way as you might assemble the parts of a injection-moulded plastic construction kit.

14. St Catherine This figure, shown holding her symbolic wheel in her left hand, was made by pouring boiling sugar into the accompanying mould, which beforehand had been either soaked in water or brushed with oil to enable the complete cast to be easily removed. The mould, now in the Museum of London, was found in the Old Bailey.

The completed figure could now be decorated – its smooth, white and slightly absorbent surface being ideal for receiving the painted brushwork. The confectionery colours used at this period were usually of vegetable origin:26

Red |

saunders (red sandalwood), the East Indian tree Pterocarpus santalinus brazilwood, the East Indian tree Caesalpinia sappan red rose petals |

Yellow |

saffron, the dried stigmas of Crocus sativus, grown around Saffron Walden cowslip or marigold petals |

Green |

the juice of spinach, Spinacia oleracea, or of green wheat |

Blue |

‘bluebottles’, the petals of the common cornflower, Centaurea cyanus |

Violet |

violet petals, Viola odorata |

The hardwoods, saunders and brazil, were reduced to fine chippings or to powder and boiled in a little water together with gum arabic, while the flower petals were ground in rosewater and the coloured juice squeezed out through a piece of cloth. Turnsole rags had only to be scalded in water to induce them to give up their colour.

All these colours were relatively safe to consume, especially since they were used in such small quantities, but other materials were positively poisonous, as may be seen from these examples mentioned by John Partridge in his book The Widowes Treasure, published in 1585:27

‘A very good green’ |

the juice of rue, verdigris (basic copper acetate) and saffron |

Emerald green |

verdigris, litharge (lead monoxide) and mercury, beaten together and ground ‘with the pisse of a young childe’ |

Gold |

orpiment (arsenic trisulphate), ground with clear quartz, saffron powder and the gall of a hare or a pike, stored in a phial in a dunghill for five days, and kept for use |

It is amazing to find such recipes in any cookery book, since anyone who consumed even the smallest amount of some of these substances would certainly become dangerously ill, if not die.

Either gum-water (a solution of gum tragacanth) or egg white was used to provide a thickening and drying medium, which made the colours easy to apply with a brush and gave a hard finish, usually with a slight gloss. (Today you should use only the safe vegetable colours, needless to say, and the whites of sterilised eggs.) For denser colours and richer flavourings, the sugar plate could be mixed with finely ground and sifted spices, or the petals of marigolds, cowslips, primroses or roses first ground into some icing sugar with a little rosewater before being made up into a paste with more sugar and a little gum tragacanth.28

In his recipe of 1562, Alexis of Piedmont had described sugar plate ‘whereof a man may make all manner of fruits and other fine things with their form, as platters, glasses, cups and suchlike things, wherewith you may furnish a table, and when you have done, eat them up, A pleasant thing for them that sit at table’.29 A table completely set with sugar-plate tableware must have been very impressive, its pure white closely resembling expensive oriental porcelain or the milk-white variety of Venetian glass. It is most probable that for producing cups and other vessels in this way the confectioners made special moulds, but flat sweetmeat trenchers, about five inches (13cm) in diameter, could be easily rolled out and cut to size, leaving a blank area that would be ideal for elaborate painting and gilding. Small platters were easily executed too, simply by dusting a sheet of rolled-out sugar plate with icing sugar, patting it dusted-side-down on top of a metal or pottery plate, then trimming the edges and leaving it to dry.

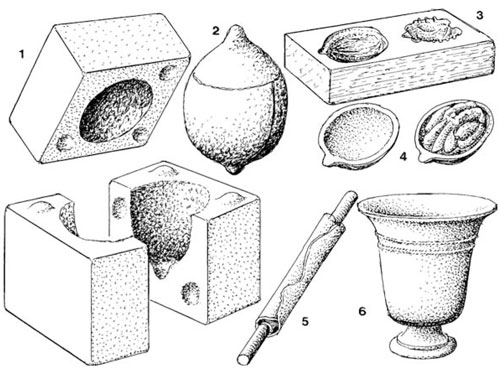

15. Sugar moulds Tudor sugar-moulding was a highly skilled craft. Here are (1) the sectional plaster moulds used to cast lemons (2) in boiling sugar; the carved wooden press-mould (3) for making walnut shells and kernels (4); and the equally realistic cinnamon sticks (5) and porcelain-like drinking cups (6), also made in finely flavoured sugar plate.

Back in the Pastry Yard after our visit to the confectionary, we find that the next doorway led into the room below, the pastry, where almost every variety of pasty, pie and tart was baked for the royal household. Its sergeants, John Jenyns in 1540–2, succeeded by John Heath before he transferred to the bakehouse, and its clerk Anthony Weldon, were responsible for ensuring that ‘all their baked Meates [were] well seasoned and served … without imbesselment or giveing away any of the same; and also that there be no wastefull expences made of any Flower or Sawce within the said Office’.30 Before eight every morning, the clerk had to deliver to the clerk of the kitchen the brief that detailed the previous day’s consumption of foodstuffs in the bakehouse, and once a month submit his ‘parcel’ of requests for fresh supplies to the counting house. The Pastry’s administrative office was on the first floor, beyond the confectionary, while the sergeant’s and clerk’s lodgings, along with those of their six yeomen, their grooms and four ‘conducts’, or labourers, were in the first-floor chambers and second-floor garrets – warm and dry over the main pastry workhouses.

There were three working rooms in the pastry, the first and smallest (no. 25) of which was probably the storehouse and boulting house for the various flours used there. These probably included wholemeal for the coarsest pastry, and from which the conducts would sift the bran to produce wheatmeal flour for common pastry, or sift again through finer sieves to produce unbleached white flour for the finer pastries. Next door (no. 24), was the main pastry workhouse, where the practical pastry-making was carried out.

Of all the foods prepared here, by far the largest and most impressive were the venison pasties made with deer either hunted in the royal parks or presented as gifts to the King – such as the stags brought from Waltham Forest to Hampton Court in August 1530, or the Windsor venison that arrived in June 1531.31 Pies of all kinds of meats, fish and fruits would also be baked here, along with open-topped tarts and custards.

Usually a number of empty tart cases would be baked, these being filled with a variety of prepared mixtures which had only to be cooked for a relatively short period. This was a sensible system for the large-scale catering necessary for great households such as Hampton Court, since the cases could be baked in the ovens while they were still hot from preparing supper for four o’clock, then stored until required for uses. In addition, this method ensured that their bases were cooked properly, neither soggy nor underdone as they would have been if baked when full of moist fillings.

16. Venison Venison for the King’s table came from his frequent hunting expeditions, from the royal parks, or as gifts from courtiers. These harts are from George Turberville’s Boke of Hunting of 1576.

All the pies and pasties made in the pastry were baked in the adjacent pastry bakehouse (no. 23). Four ovens were built in its west wall by Gabryell Dalton in 1530; all were constructed with shallow domed roofs made of tiles set edge to edge to resist the effects of the constant fierce heat followed by gradual cooling.32 The largest measured over twelve feet (3.7m) in diameter – ideal for all the largest pasties. In front of the ovens, extending across one third of the pastry bakehouse ceiling, was a huge smoke-hood shaped like a half-pyramid, designed to carry away all the smoke that issued from the oven mouths as they were fired up to temperature, just like those in the Outer Court bakehouse.

Unlike many of the other foods prepared in the kitchens, pastries could be kept fresh for quite a few days after being baked, so long as they remained cool and dry. For this reason, the north-facing room just to the east of the pastry was used as a dry larder (no. 28). Pre-empting modern food hygiene regulations by four and a half centuries, the Tudor cooks fully appreciated the need to keep raw and cooked foods separate if outbreaks of food-poisoning were to be avoided. By storing its finished goods here, the Pastry was able to maintain a reservoir of supplies ready to be whisked off down the Paved Passage to the servery hatches.

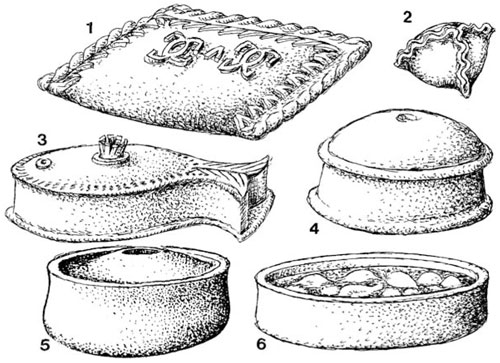

17. Pasties and Pies Tudor pasties and pies were made in a variety of shapes. Here we see venison pasties (1) marked with an appropriate V, based on an illustration from Robert May’s The Accomplish’t Cook (1660); and a smaller triangular pasty (2) as recommended by Thomas Dawson. Some raised pies, like May’s salmon pie (3), used their shape to indicate their contents, while others resembled modem pork pies (4) or had their lids blown up using a straw before being put into the oven (5). This one, together with the open-topped tart (6), is based on an engraving showing James I entertaining the Spanish ambassadors in 1623.