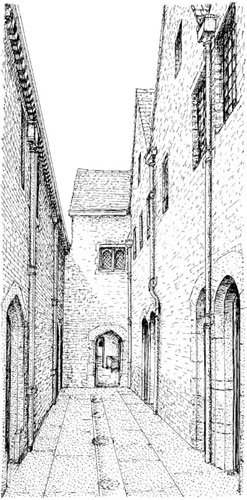

Between the Pastry Yard, the main kitchens and the Privy Orchard to the north lay a block of larders and preparation kitchens, all entered from a narrow central corridor open to the sky. Known as the Paved Passage up to the late seventeenth century at least, it is now called Fish Court (no. 27).

![]()

The larder where the raw meat was stored was located at the centre of the Paved Passage’s southern wall (no. 33). The meat delivered here was already butchered; the sergeant of the acatery who organised its transport on the hoof from the royal estates or the markets would have arranged the messy, noisy, smelly slaughtering well away from the main palace buildings. He and his officers took specified parts of each carcase as their fee: the sergeant received the head, tongue, midriff, paunch and four feet of each ox, while the yeoman and groom had its belly-piece, rump, and ‘sticking-piece’ along with the head, caul, ‘gatherings’ (heart, liver and lungs) and feet of each sheep; and the clerk got the head and skin of each veal calf.1

On arriving at the palace kitchens, the carcases would be brought through the Back Gate to the door leading from the Pastry Yard into the boiling house (no. 26) and from there into the larder. Here ventilation was very important for keeping the meat fresh, although the throughput must have been very rapid when the court was in residence. In the Larder, the meat was inspected by James Mitchell, sergeant of the larder, and its quantity recorded by his clerk, Anthony Weldon.2 In 1541 Weldon had been granted both the income from the town of Penlosse in northwest Wales and the passage of boats to Conway, etc. By 1543 he was clerk of the pastry, and then promoted to second clerk of the kitchen, while in 1544, when he returned to the larder, he received the lease of the manor of Swanscombe in Kent. Weldon had done well for himself. But it was not unusual for officers to substantially improve their income through service in the household.3

18. The Paved Passage Now known as ‘Fish Court’, this passageway provided the main means of communication between the larders, the boiling house, the pastry, the workhouses and the main kitchens. The upper rooms were used as lodgings for the staff who worked in the rooms directly below, the larder staff sleeping over the larders to the left.

The work cycle began here in the larder each evening, when the clerk comptroller and the clerk of the kitchen, together with the larder staff, attended ‘the coupage of the fleyshe … in the grete larder, as requiryth nyghtly to knowe the proportion of beef and moton for the expences of the next day, and see the fees thereof, to be justly smytten by the yeoman cooke’.4 The larder officers, like the acatery officers just mentioned, took their ‘fees’ in the form of joints cut off the ends of the carcases. The sergeant had the two joints of each ox cut from just above the rump, the two top neck joints with the ‘bore of the head’, the feet, the belly piece and the hindquarters ‘to the arse bone’, while the yeomen had the forelegs struck off at the first joint, and a piece of the first joint of the neck.5 The yeomen also took three joints of the scragend of the necks of sheep and veal calves, along with their rumps and the lower parts of their back legs, while the grooms had the head, feet and small end of the chine, or lower back joint, of every hog. The main parts of the carcases, complete with ribs, breasts, shoulders, loins and hindquarters, would then be cut into portions, each sufficient to serve a certain number of messes ‘according to the ancient custome’6 Each ox, which would weigh some 500lb (227kg), was cut up into major joints that would provide the following messes:

19. Larder fees The ox and sheep heads, together with the tongue, as shown in this woodcut from Lobera de Avila’s Banket der Hofe und Edelleut of 1556, would all have been cut off and taken as fees by the officers of the larder, leaving only the main carcases for the kitchens.

Messes |

|

Two livery pieces |

10 |

Two crops [necks] |

6 |

Two briskets [lower chest] |

6 |

Two sirloins [small of back] |

4 |

Two shoulders |

4 |

Chines (lower back) |

4 |

Fillet (undercut to sirloin) |

4 |

38 messes |

|

at 4 people per mess, 152 individual servings |

As for the other carcases:

Messes |

Individual servings |

|

One mutton |

10 |

40 |

One veal |

12 |

48 |

One pork |

13 |

52 |

One stirk (a bullock or |

||

heifer of 1–2 years) |

24 |

96 |

The meat was cut in the evening so as to be ready for cooking at any time after five the next morning, in time for the ten o’clock dinner. The poultry and rabbits that had been plucked or skinned in the scalding house in the Outer Court arrived in the larder before eight, so that the officers could distribute them to the various master cooks, as needed for that particular day’s dinner and supper.

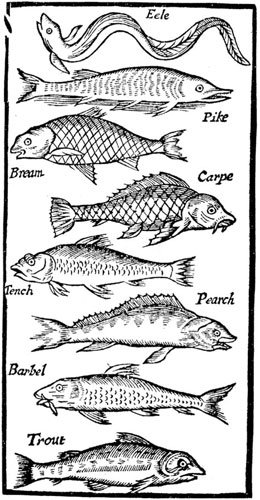

20. Freshwater fish Many of these varieties, illustrated in Hannah Woolley’s The Accomplish’t Lady’s Delight, would have been brought into the larders shortly before being cooked on the Friday and Saturday fish-days.

Just to the west of the larder lay the wet larder (no. 32), where the fresh fish was probably kept for almost immediate use. Most of the sea-fish was provided by Thomas Hewyt of Hythe in Kent, to whom a contract had been awarded by the officers of the green-cloth.7 He would send the fish up from the coast in panniers slung from the sides of pack-horses, led by a servant who also carried a note of its prices. The most expensive fish were bought individually, a halibut costing 2d, a John Dory 12d, and porpoises, not above one horseload, 13s 4d; the prices of larger ones were agreed with the clerks comptroller. The other fish were bought by the ‘seam’, a very practical measure since it represented a single horse-load:

1 seam of pilchards |

6s |

1 seam of herrings |

9s |

1 seam of mixed conger, cod, whiting and thornback |

10s |

if no conger or cod in seam |

6s |

1 seam of plaice |

10s |

1 seam of mullet, turbot and bass |

13s |

Freshwater fish was brought to the palace by purveyors such as Robert Parker and George Hill, who provided the following at these agreed rates:8

Length |

||

Pike, alive |

18–21 in (46–53cm) |

14d |

bream |

16–18 in (40–46cm) |

30d |

carp |

16–18m (40–46cm) |

48d |

perch |

9–12in (23–30cm) |

3d |

trout |

14–17in (35–43cm) |

8d |

chub |

16 in (40cm) or more |

14d |

roach, large |

10in (25cm) or more |

1d |

roach, small |

7–10in (17.5–2.5cm) |

¼d |

Weight |

||

eels |

3lb (1350g) |

10d |

panniers of crab and lobster |

100lb (45kg) |

96d |

salmon, fresh and calver, by |

||

agreement with the clerk comptroller |

In addition, fish were kept in ponds extending from the front of the King’s apartments at Hampton Court, across towards the Thames. These are now drained, but the site is still called the Pond Gardens.

Having been checked and recorded by the sergeant and clerk of the larder, the clerk of the kitchen and the clerk comptroller would presumably supervise the cutting of the ‘fees’ of the fish – for the master cooks had all the salmons’ tails, the heads of turbot, halibut, purpoise and so forth.9 The fish would then be given to the cooks so that they could prepare them for that day’s meals.

![]()

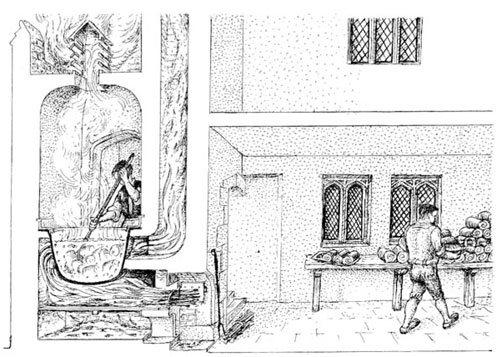

Next to the larder lay the boiling house (no. 26), staffed by four yeomen and two junior servants and supervised by the sergeant of the larder, who was charged to ensure that ‘the Beef be put to the lead every morning in due time, soe that it may be thorough boyled when it shall be served’.10

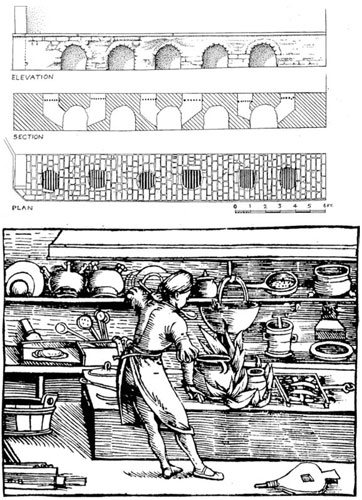

At Hampton Court a lead, or copper boiler, was installed in the boiling house in September 1531.11 It was probably coated with tin inside, like the boiling vessels listed in the inventory of all equipment in the palace’s kitchens drawn up for the Commonwealth in 1659, and like the copper pans used in any modern restaurant kitchen. (Without this tinning, the copper is attacked by the acids in the food, dissolving into it, spoiling the taste and eventually causing poisoning.) Early in the morning the lead would be filled with water – it probably had its own supply on tap from a cistern full of spring water in the rooms above. Faggots or similar fast-burning timber would then be lit and fed into the long firebox underneath, which had raised firebars to ensure that the fuel burned as fiercely as possible. From here the flames played directly on to the base of the copper and then were drawn up flues at the back of it and forwards around the upper parts of both sides, to ensure that they made maximum contact with the huge cauldron before being carried away up the chimney.

Although Hampton Court’s original copper does not survive, the dimen sions of the surrounding masonry and furnace arch show that it must have held around 80 gallons (364 litres), which would have given it the capacity to boil batches of around two hundred messes – enough to serve eight hundred people at a time. On the other hand, given that the household regulations state that its primary purpose was to boil all the beef, it would have been barely large enough to meet the demands placed upon it unless the better-quality beef for the nobles etc. was boiled in the Lord’s side kitchen – as may have been the case.12

21. The Boiling House This large built-in copper boiler was supplied with spring water from a tank in the rooms above, and was heated by a typical flue system which conducted the flames first underneath and then around its upper parts.

From its position, it looks as though the boiling house was used as a preparation facility for the pastry and main kitchens too. There would certainly have been time to receive the raw meats from the larder each night or early morning, parboil some of them between, say, 5 and 7.30 a.m. for transfer to the pastry for pie- and pasty-making, or to the kitchens for roasting, and still boil a batch of 200 two-pound (900g) beef joints ready for dinner at 10 a.m. Needless to say, the boiling house would have been constantly bustling, the staff busy non-stop with trimming and trussing the joints, putting them into the copper, stoking the fire, baling out the boiled meats into kettles and pans for transfer to the pastry, the other kitchens or the serving hatches. Then, once dinner had been served, they would start all over again so as to be ready for the four o’clock supper. For all this, in addition to their wages, the boiling house staff received the strippings from the brisket joints, the grease produced from the transfer of the meat from the boiler into the kettles and pans, and the dripping from the roasts in the kitchen.13

The major by-product of the boiling house was pottage. As the ever-informative Andrew Boorde recorded, ‘Pottage is not so much used in al Crystendom as it is used in Englande. Potage is made of the lyquor in which flesshe is sodden [boiled] in, with puttyng-to chopped herbes and oatmeal and salt.’14 It formed an excellent broth, with which to start any meal.

All manner of herbs good for pottage15

Take the crop of red brier,

Red nettle crop and avens [herb bennet, Geum urbanum] also

Primrose and violet together mostly go,

Lettuce, beets and borrage good,

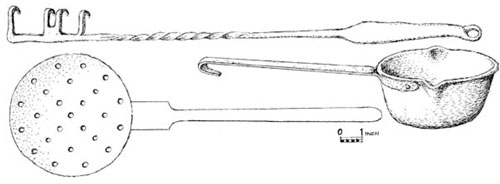

22. Boiling utensils The flesh hook was used to lift the hot meat out of the boiling water – this example was found in the cellar of a house in Norwich which burned down on 25 March 1507. The large broth ladle is based on one in Bartolommeo Scappi’s famous cookery book of 1570, while the skimmer, for removing the scum, was used by William Coke, cook to William Cannynge of Bristol. When Coke was buried in his master’s great church, St Mary Redcliffe, in 1467, the mason simply placed it on his gravestone and carved its outline, which remains there today.

Town cress, cress that speweth in flood,

Clary, savory, thyme good won,

Parsley worth other herbs many a one.

All other herbs thou not forsake,

But best of primrose thou shalt take,

Red cole [cabbage] half part pottage is,

From June to St James tide [25 July] I wis,

Then winter his course shall hold.

In lent season porray [leeks] be bold.

![]()

On the opposite side of the Paved Passage, to the north between the dry larder and the main kitchens, were two rooms, each having a wide fireplace with a small oven set to one side of it (nos 30–31). In 1674 these were listed as the comptroller’s and master of horse’s kitchens, but this must be a later usage. From their position and their facilities, it is obvious that in the 1530s–40s they were the workhouses for the adjacent hall-place kitchen. These smaller kitchen workhouses were ideal for carrying out the more delicate cookery procedures, particularly the making of hot sauces which formed an integral part of many major dishes, and the better-quality small-scale roasting and baking. Unfortunately, there are neither inventories nor written descriptions to tell us how they were equipped and used. However, it is possible to make informed suggestions by comparing them with the contemporary commercial kitchens probably operating on a similar scale.

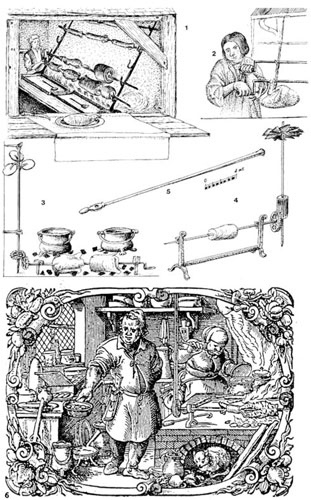

The ovens, for example, would be used exactly like those in the bakehouse and pastry and so could turn out dozens of small pastries and tarts. As for the fireplaces, they would appear to be unsuitable for full-scale roasting fires, particularly in view of the relatively small size of the rooms. Probably they would have had raised masonry hearths, where the cooking could take place at a convenient table-top height. As in the seventeenth to mid nineteenth century royal kitchens, they may have incorporated charcoal stoves. The seventeenth century charcoal stoves that still survive in the hall-place kitchen, presumably the very same that were used by great royal cooks such as Patrick Lamb, First Master Cook in the King’s Kitchen from 1688 to 1709, perfectly illustrate their construction. Built of brick, they have a number of arched recesses set into their vertical fronts. Every other arch is simply a bunker for holding supplies of fresh charcoal, but the ones in between have square ducts going off to each side, each duct bridged by parallel rows of square wrought-iron firebars a few inches from the worktop. These form the bases of circular firepits, which held the burning charcoal. The fuel drew up a strong draught from below, while the ashes fell directly down into the empty arches beneath.

23. Charcoal stoves These seventeenth century charcoal stoves (top) in the hall place kitchen are probably very similar to those used by the Tudor cooks. As the cross-section shows, three of the open arches have pairs of combined draught- and ash-holes serving the six fireplaces on the top, so that the fuel could burn with a clear, fierce heat. The other two arches formed convenient bunkers for fresh charcoal.

Hans Burgkmair’s woodcut published in 1542 (bottom) shows a charcoal stove in use for boiling and broiling. Other interesting features include a chopping board with raised sides, cast-bronze cooking pots, a mortar and pestle and, to the right, a typical wooden salt-box with a sloping, hinged lid.

24. High-level roasting Town cook-shops used table-height roasting ranges, as seen in Hoefnagel’s painting, The Marriage Feast at Bermondsey (1). Here the turnbroach operates two spits at once, like his late fifteenth century Italian counterpart at the Castello d’lssogne (2). Since this was the standard commercial practice of the period, it may have been adopted by cooks working in the royal household. They probably used jacks, too, like the one in drawing 3, based on a woodcut from Kuchenmeisterei (printed by Froschauer, Augsburg, 1507), and a drawing based on Bartolommeo Scappi’s illustrations of 1570 (4). A jackshaft (5) was excavated from a cellar dated to 1507 in Norwich. The chicken roasting in the woodcut from Marx Rumpolt’s Ein Neu Kochbuch of 1581 (6) is being turned by a rope driven from the smoke-jack in the chimney above.

These stoves are far superior to any modern barbecue, burning efficiently with a steady, clear heat ideal for boiling or frying, and immeasurably more practical for undertaking the more delicate aspects of cookery than the great open hearths of the adjacent kitchens. They are very clean to use, too, their combustion gases leaving only a light coat of ash on the bases of the cooking vessels, and producing no visible smoke. Under normal conditions, when the fumes are drawn straight upwards, these stoves present the cook with few problems, but when sudden draughts direct the invisible gases into his face the effects are devastating – rather like being punched on the nose by a scorching phantom boxing glove, leaving one gasping for breath, eyes watering and nostrils burning. Since the open top of each firepit was its effective chimney, pans could not be placed directly over it or the fire would be stifled. Instead, a triangular wrought-iron trivet with three legs a few inches high was used to support the cooking vessels; this also had the advantage of leaving the fire open to view, so that it could be poked to shake out the ash or have fresh charcoal added whenever necessary.

With cooking facilities like these, along with all the smaller implements such as the graters, sieves, spice-boxes, salt-boxes, bowls, knives, spoons, skimmers, mixing bowls, cooking pots and frying pans, the palace cooks would be fully equipped to perform the tasks allotted them by the clerk of the kitchen.