More than sixty years ago, an editorial in the Aspen Times summarized the challenge we face in this chapter: “To write a history of this famous old town in one newspaper article or even in one book, is a task which fails of accomplishment.”1 Instead of writing a history of this beguiling, maddening place, here we simply offer our own perspective on the crucial themes that are illustrative of the town’s past and its legacy of environmental privilege. From these seeds, we can better understand the resource-destroying forest that Aspen has become. We begin with the lasting lure of Manifest Destiny in the American West. From this broad beginning, we gradually narrow our focus to the long and embattled relationship between those white settlers who were pursuing their manifest destiny and the various nonwhite peoples who either stood in the way or facilitated that goal. From these relationships we gain a new understanding of Aspen’s evolution: for more than a century, this area has hosted extractive industry of one kind or another, and today’s Aspen, and the people who both revel in it and service it, are the latest link in that long, environmentally and socially degrading, chain.

The histories of the American West are largely contained and shaped by the ideology of Manifest Destiny and the desire to conquer new frontiers. For more than a century and a half, individual citizens, the state, and innumerable industries have searched for storied wealth and riches in this region. The West was, and remains, a site of imperialism for the U.S. government, corporations, and a largely European American population; it is a resource colony because it facilitates the continued domination of both people and nature. This process is made easier by more than a century of permissive federal legislation, which essentially handed over public lands and ecosystem resources to prospectors, miners, and companies of all stripes, both domestic and foreign.2 The historian Patricia Limerick put it this way:

We now have a situation in which the resources of the United States’ public lands are being mined by companies that are, many of them, foreign corporations—Canadian, northern European, and South African. Thanks to the 1872 Mining Law, these companies do not contribute revenue to the United States Treasury in return for the minerals taken from the public lands.3

Unlike people from particular global South nations, foreign corporations were welcome to come to the United States and, for a pittance, can mine or strip western land of its natural wealth and can use laborers from across the globe to perform this dangerous work. Those corporations that engage in hard-rock mining of gold and silver from public lands pay no royalties at all. Through the 1872 Mining Law, combined with earlier legislation, the federal government encouraged the exploitation of the land and its settlement by European Americans during the nineteenth century and after.4 During the twentieth century, the U.S. Forest Service subsidized the timber industry by selling tracts of forests at huge discounts and building roads for that industry. Together with the federal Bureau of Land Management (BLM, part of the Department of Interior), these two agencies have largely viewed their role as facilitators of mining, oil and gas extraction, logging, and cattle-grazing operations in the West, particularly on public lands.5

The historian and conservationist Bernard DeVoto spoke and wrote adamantly against the use of the West as the East’s resource colony. He fervently believed the western United States had a right to its own autonomy from the East Coast and that the nation had every obligation to protect its precious ecosystems. He described the situation in this way:

From 1860 on, the Western mountains have poured into the national wealth an unending stream of gold and silver and copper, a stream which was one of the basic forces in the national expansion. It has not made the West wealthy. It has, to be brief, made the East wealthy6. . . . Eastern capital has been able to monopolize oil and gas even more completely than it ever monopolized mining. In a striking analogy to eighteenth-century mercantilism, the East imposed economic colonialism on the West. The West is, for the East, a source of raw materials for manufacturing and a market for manufactured goods. Like the colonies before the Revolution the West is denied industry.7

Such voices among prominent scholars, however, are in the minority. For, as we know, much of U.S. history is built on the notion that such exploration and exploitation are essential aspects of our psyche and national identity. Unlike DeVoto, many historians have heralded such practices. Frederick Jackson Turner’s famous 1893 paper “The Significance of the Frontier in American History” contended that the idea of the frontier was a looming—and positive—presence in the American mind because it contributed to the nation’s cultural vitality and global exceptionalism. The 1890 Census declared that the frontier of the American West had been reached, populated, and closed; Turner’s thesis thus gave support to those who anxiously believed that the United States must continue this process of infinite expansion (i.e., frontier seeking) beyond the West via overseas imperialism.8 Turner’s paper was deeply influential in shaping the popular imagination of the American West, but it was also problematic in that his perspective was contemptuous of people of color and women, if only in their glaring absence in the essay, and the notion that the western frontier itself was closed was just plain wrong. As Limerick argues,

There was more homesteading after 1890 than before. A number of extractive industries—timber, oil, coal, and uranium—went through their principal booms and busts after 1890 . . . the nineteenth-century westward movement was the tiny, quiet prelude to the much more sizable movement of people into the West in the twentieth century.9

New frontiers—or, the term Limerick prefers, “conquests”—were continually unfolding in the West well after the Census and Turner declared its closure. The West is dotted with massive hydroelectric dams, oil, timber, and mining operations, and commercial farming and ranching; all of these industries are significantly larger today than they were in the nineteenth century. The continued and increasing reliance on extractive industries like oil, timber, mining, and hydropower also suggests that the term “Information Age” applies only to some sectors and puts to rest the notion that we have somehow entered a post-materialist economy.10 We are as dependent upon the extraction of ecological wealth (or “natural resources”) as we have ever been.

Our reliance on ecosystems is so great, in fact, that today these practices are often politically explosive and increasingly unpopular among affected communities, since they typically harm local ecologies and ensnare people into volatile economic cycles.11 Towns across the American West—certainly in the Rocky Mountain region—have seen their fortunes rise and fall based on a close reliance on a single ecological resource, tapped for export—the environmental consequences be damned—which has rendered much of the West a supply depot for the rest of the nation.12 As one historian put it, the “drive for economic development of the West was often a ruthless assault on nature, and it has left behind much . . . depletion and ruin.”13 It is also a heavily militarized region, with many parts of the area used for bombing ranges, testing sites, and nuclear waste dumping grounds.14

Many scholars argue that the West is also a site where movements for environmental conservation and preservation have taken hold and where environmental ethics run deep. We agree, but we must also qualify that claim. As we look more closely, we can see that most of these efforts have long been and continue to be aimed at the protection of open space and ecosystems for affluent or white populations and from people of color and indigenous peoples.15 That quest for white environmental privilege has been a defining feature of environmentalism and cultural politics in the West, just as it has been in the rest of the United States.

We should not forget that the American West is where many of the largest Indian reservations are located and where Mexico lost major territory through the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848. This is also where some of the nation’s most impressive and vast national parks are located, which were produced in the name of patriotic conservation and preservation, but which also involved the displacement and exclusion of Native peoples who first lived in these spaces.16 Patricia Limerick reminds us that multiple groups have been marginalized and oppressed in western history, not just the working classes, women, and people of color. She explains how religious minorities and labor radicals are often forgotten members of oppressed populations in the region. “Judging by the written record alone, a historian blind to actual physical characteristics might think that there were at least eight oppressed races in the West: Indians, Hispanics, Chinese, Japanese, blacks, Mormons, strikers, and radicals.”17 The West is a landscape charged with politics, violence, and righteous ideologies of who belongs and who does not, and who should and shouldn’t have access to the land and its ecological wealth.

What Frederick Jackson Turner did get right was his observation that the idea, the myth, of the frontier is one of the most important stories in the American imagination. The frontier was and is a site of conquest—of both nature and the people who inhabit it. The frontier, in his words, has “been the means to our achievement of a national identity, a democratic polity, an ever-expanding economy, and a phenomenally dynamic and ‘progressive’ civilization.”18 Across the twentieth century, even as the literal “frontier” became more and more settled, the potency of the metaphoric frontier remained. John F. Kennedy’s use of the imagery and symbolism of the “new frontier” after his presidential nomination by the Democratic Party in 1960, was a linguistic technique he employed to justify his use of power. Just seven years later, U.S. forces would be heard talking about Viet Nam as “Indian Country” and describing war tactics there as a game of “Cowboys and Indians.”19 Decades later, U.S. troops would refer to places like Iraq and other spaces around the globe as “Indian Country.”20

Today’s American West, like the West of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, remains ensconced in this mythical narrative. Alongside mining and ranching and other extractive industries, a powerful new economy has emerged: tourism. In addition to utilizing the land’s material wealth, now a different group of corporations utilizes a more ethereal resource—the land’s beauty, and its capacity for entertainment and adventure.21

Colorado’s state seal features a pick and shovel, highlighting the fact that mining and ecological wealth extraction are at the core of the state’s history and anticipated future. Paralleling that history and continuing legacy of environmental domination, are long-standing practices and polices of racial exclusion, violence, and control.

It seems Colorado has been the site of more than its fair share of right-wing causes since it began as a mining state. In the 1990s alone, this state spawned several right-leaning initiatives, including the anti-gay Amendment 2, the Aspen and Pitkin County resolutions on population stabilization, and legislative efforts by the “English only” movement to maintain the dominance of a single language in Colorado’s public institutions. It is also home to notoriously powerful conservative Christian groups like Focus on the Family. Also located in southern Colorado is the U.S. Air Force Academy, contributing official respectability to militarism. Even so, it is important to acknowledge the constant presence of countervailing progressive forces, including environmental, labor, peace, indigenous, and racial justice movements in Colorado. This would include the Chicano Movement organization known as the Crusade for Justice, led by Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzales (who also helped found the La Raza Unida Party), the Colorado Chapter of the American Indian Movement (AIM), and environmental justice and human rights groups like the Colorado Peoples Environmental and Economic Network, Global Response, and the Rocky Mountain Peace and Justice Center. But long before these organizations were born, the state’s cultural and ecological terrain was under a full-scale assault from the military, settlers, and corporations.

The first U.S. official to fully explore the mountains of Colorado was Zebulon Pike who, during his travels to the area in 1810, came upon numerous Spanish and Indian settlements that had been thriving for years.22 The U.S. military continued to survey and map the area for decades afterward. In the late 1850s there was a Gold Rush in the Colorado Territory that triggered a reverse migration, as many of the ’49ers in California returned East to seek fortune in the mountains and streambeds of the Rockies. By the 1870s, white settlers had built several small towns in the Rockies where they routinely expressed fear of Indian attacks and frequently called on the government and military to control Native populations.

One of the most horrific chapters in Colorado’s history was the 1864 Sand Creek Massacre of a band of the Cheyenne and Arapaho people. With the movement of federal troops from the West to fight in the Civil War, white citizens and the press felt vulnerable and urged Governor John Evans to solve the “Indian Problem.” Tensions increased as Indians resisted their confinement to reservations, and Anglos continued their incursions onto Indian lands. In response, Evans authorized citizen militias to exterminate any “hostiles” who refused to give up their arms and return to lands agreed upon in an 1861 treaty.23 These social dynamics and Evans’s authorization contributed to the Sand Creek massacre, in which at least 165 Cheyenne and Arapaho were killed in an early morning surprise attack by U.S. troops on November 29, 1864. A special investigation of the incident concluded that the army unit involved had perpetrated “gross and wanton outrages” against a peaceful people.24

Tribes from what whites called the Colorado Territory (statehood came in 1876) were targeted for reservations or extermination. But the Utes were the last to retain any claims to lands in the state. Silver prospectors first called the town that would become Aspen “Ute City” because the Utes were the main Native population in the area. The growing numbers of white miners on the Utes’ hunting grounds was the beginning of a long struggle over what would become a playground for the ultra rich.

The Utes signed their first treaty with settlers in 1863, which reduced their land base to acreage in the Colorado Territory west of the Continental Divide. But, as whites sought more gold and silver, those boundaries were seen as threats to progress. An 1868 treaty between the Utes and the federal government pushed the tribe onto reservation lands in southwestern Colorado to ensure Anglo access to minerals and lands fertile for agriculture. A major loophole in the treaty was that Anglos and the government could drive railroads and highways through Ute land in perpetuity to gain access to other territories. This was guaranteed to produce further conflict and did, when, in the summer of 1879, whites discovered silver in Colorado’s Roaring Fork Valley. There, they staked claims and built camps, including in a place that, in 1881, would become the city of Aspen.25

That year, an Indian agent, Nathan Meeker, plowed the White River Ute’s lands, without their permission, in an effort to force them to take up Anglo farming methods. A conflict ensued, escalated, and ended in Meeker’s murder, which in turn spawned the Ute War of 1879. The “Meeker Massacre,” as it became known, provided a justification for moving the Utes farther West, so as to make the Roaring Fork Valley available for white settlement. Colorado’s governor Frederick W. Pitkin adopted the slogan “the Utes must go!” and fully supported tribal displacement and genocide.26 In a statement he made before the Colorado legislature, Pitkin made the case for Indian removal and exclusive environmental privilege for whites:

Along the western borders of the State, and on the Pacific Slope, lies a vast tract occupied by the tribe of Ute Indians, as their reservation. It contains about twelve million acres and is nearly three times as large as the State of Massachusetts. It is watered by large streams and rivers, and contains many rich valleys, and a large number of fertile plains. The climate is milder than in most localities of the same altitude on the Atlantic slope. Grasses grow there in great luxuriance, and nearly every kind of grain and vegetables can be raised without difficulty. This tract contains nearly one-third of the arable land of Colorado, and no portion of the State is better adapted for agricultural and grazing purposes than many portions of this reservation. Within its limits are large mountains, from most of which explorers have been excluded by Indians. Prospectors, however, have explored some portions of the country, and found valuable lode and placer claims, and there is reason to believe that it contains great mineral wealth. The number of Indians who occupy this reservation is about three thousand. . . . If this reservation could be extinguished, and the land thrown open to settlers, it will furnish homes to thousands of the people of the state who desire homes.27

The governor’s words made it clear that vigilantes and frontier extremists were not the ones driving Indian removal and extermination; this was a process being spearheaded by state and corporate interests.

Still another treaty the following year reduced the tribes’ land base even more. In a racist dehumanization that typically supports such moves, a local newspaper front-page story read: “Colorado’s Governor has declared it to be the duty of frontier settlers to treat as wild beasts all Indians found away from the reservation.”28 One year later, in 1881, most of the Utes in Colorado were moved to reservations in Utah.29 This case was just one of many in which indigenous peoples in the United States were living on lands that contained ecological wealth, which whites saw as their God-given entitlement.30 The displacement of natives from mineral-rich lands and their relegation to reservations is a time-honored example of the use of borders and violence to maintain white supremacy and environmental privilege.

Even after being removed and sent to Utah, the Utes were required to have a special pass to travel off the reservation, and such a pass could be granted only by an Indian agent or well-placed public official. The following pass was found in a raid on a Ute camp in Utah:

Ouray Indian Agency, Utah, May 15, 1886. To whom it may concern: The bearer of this is Uncompaghre Colorow, who asks for a paper as he intends visiting Meeker [reservation]. I request kind treatment for him from all citizens he may meet and forbearance so long as he remains peaceable and friendly to the whites. He asks me to say that he feels friendly to all Americans. Signed, Edward L. Carson. U.S. Indian Agent.31

Troubles continued well into the late 1880s as Native uprisings occurred periodically, but the Utes were soon overwhelmed militarily, and the Rocky Mountains were secured for white exploitation and enjoyment.32

In 1993 an historic powwow took place in the Roaring Fork Valley. This event united the three Colorado Ute tribes for the first time in one hundred years. They came together for this occasion because the U.S. Forest Service and other federal agencies wanted them to sign a Memorandum of Understanding, which would allow the agencies to consult with tribes to make sure that sacred sites and artifacts would be preserved in the face of future development.33 In other words, the primary driver for this agreement was—and is—to guarantee the rights of developers. This agreement actually allowed these agencies to prevent legal liabilities by securing tribal agreement to the consultations and still allow ski area and commercial and residential developments to go forward. The U.S. economy’s thirst for land and other ecological resources was so strong that even seemingly positive developments like consulting with Native nations in order to preserve their sacred spaces actually revealed other motives.

At the same time, in places like Aspen, Native American culture is appropriated and sold mercilessly. In 1992—the year of the five hundredth anniversary of Columbus’s genocidal voyage to the New World—the Wind-star Foundation in Aspen hosted an event called “Living the Sacred Circle: Healing Time.” According to the brochure, the theme was “the Native American way of life” and participants paid up to $500 for admission to hear the wisdom of the Natives, none of whom were Utes, despite the fact that they were the first people in Aspen. Luke Duncan, chairman of Uintah-Ouray tribe (an Ute band) commented to reporters:

I’ve seen so many times across Indian country how other people . . . have picked up on the ways of the Indians, only to turn around and sell that ceremony to someone who lives in the urban areas. And it happens

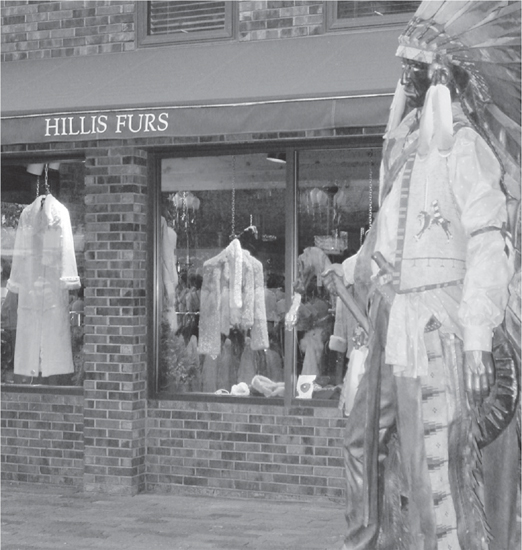

Cigar-store Indian statue next to a furrier. Photo by L. S. Park

right here in Aspen. That is a form of disrespect to Indian people, since that ceremony belongs to the Native Americans and we do that with respect. . . . The healing process we go through, it is not a game to us and it should not be used for monetary gain by anyone, including Native Americans.34

Throughout the Roaring Fork Valley today, disturbing signs of the appropriation of Native history and culture abound.

Walking the streets of Aspen and other Roaring Fork Valley towns, you pass cigar-store Indian statues, and you can buy a dream catcher to hang in your window or an “authentic” Indian blanket to keep you warm. You can even experience the “Happy Hunting Ground” of the Sioux Villa Curio in Glenwood Springs.35 Native Americans, just like the minerals in the land itself, have become one of Colorado’s most valuable and most exploited resources.

Historically, as Native Americans grappled with the growing stream of new arrivals on their land, more and more of the faces they encountered were not white. Since the mid-nineteenth century, Colorado has always had a significant immigrant population. By 1870 around 17 percent of the population was foreign born.36 Most of these immigrants were from northern Europe or spoke English (Germans, Canadians, Swiss, French, Britons, Scandinavians). By 1910 the immigrant population in Colorado was increasingly from other parts of Europe or from countries where English was not the primary language (Slovenia, Hungary, Croatia, Serbia, Russia, Poland, Greece, Mexico, Japan, China, the Netherlands, and Finland). These groups faced a great deal of hostility at the hands of Anglo and native-born white Coloradans, attributed to nativist anxieties over ethnic, religious, and linguistic differences. Not surprisingly, environmental injustice was common. Many of these groups were packed into segregated communities like Globeville and other Denver neighborhoods where living and working conditions were dirty and hazardous. The American Smelting and Refining Company (later renamed ASARCO) operated a refinery that polluted many neighborhoods in the Denver area, the majority of them populated by ethnic minorities. In Leadville, immigrants were the hardest hit during a typhoid outbreak in 1903 that claimed five hundred victims. And while European immigrants were allowed to enter the formal political arena, like most of the country, African Americans and Asians in Colorado were “totally excluded from politics” in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.37

Many whites in the American West at this time seemed to reserve a particular contempt for Chinese immigrants, reflecting the national mood at the time, which was punctuated by the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, barring most Chinese immigrants from entering the United States. A sign posted at the Leadville city limits summed up the sentiment rather bluntly: “All Chinamen will be shot.”38 Chinese people were also barred from setting foot in the city of Aspen during the town’s early years, beginning in the 1880s.39 A group of Chinese men was run out of Caribou, Colorado, in the early 1880s, and a newspaper in Boulder praised this action.40 Denver was also the site of an anti-Chinese riot in 1880, in which homes and businesses were burned and looted, and many people were assaulted, including an elderly Chinese man who was hanged from a lamppost on the corner of Lawrence and Nineteenth streets.41 This, of course, was part of a much broader rash of anti-Chinese violence and riots occurring throughout the American West from the 1870s to the turn of the century.42

Mexican immigrants and Mexican Americans in the state fared no better. Mexicans have been in western Colorado since the time that land was owned by Mexico. After the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (1848) and the subsequent founding of the state of Colorado (1876), Mexican Americans and Mexicans migrated from nearby states and from Mexico for work. There was a spike in Mexican immigration to the U.S. Southwest during and after World War I to fill jobs in steel plants, agriculture, and other key industries. For them, school and residential segregation in Colorado were the order of the day. In rural Weld County, the school superintendent made it clear that education would remain segregated for as long as he was in office: “the respectable people of Weld County do not want their children to sit along side of dirty, filthy, diseased, infested Mexicans.”43 And while the Colorado Fuel and Iron Corporation, the Great Western Sugar Company, the Holly Sugar Company, and the American Beet Company all heavily recruited Mexican immigrants to work in their southern Colorado facilities, many Anglo residents despised these newcomers, often making little distinction between them and Hispano Coloradans who had lived there for generations and faced similar hardships. During the Great Depression, there was such anxiety about job security in the state that in April 1936, Colorado governor Ed Johnson declared martial law on the U.S.–Mexico border and ordered the Colorado National Guard to prevent Mexicans from entering the state.

Colorado was a hotbed of nativism and religious and racial intolerance, stemming in part from its embrace of the doctrine of Manifest Destiny, which assumed a white birthright to the land. People of color, immigrants, and Native peoples continued to experience displacement and discrimination in terms of property, politics, housing, and labor markets throughout the twentieth century.

A group of silver miners founded Ute City in 1879, ignoring the governor’s pleas that they leave the area during an Ute uprising. A year later the businessman, promoter, and publisher B. Clark Wheeler incorporated the Aspen Town and Land Company, on behalf of eastern investors looking for silver wealth in the Rockies, and renamed the town Aspen. Many of Aspen’s founders and first residents came from other nations, such as East Prussia (Henry P. Cowenhoven), New Brunswick, Canada (David R. C. Brown) and Bavaria, (David Hyman).44 As a result, like the goldfields of California, Aspen was largely under the control of absentee corporations.45 The Aspen Mining and Smelting Company was headquartered at 54 Wall Street, in Manhattan. The historian Malcolm Rohrbough wrote, “the single most powerful economic force in Aspen in 1888 was a corporation with its headquarters on Wall Street in New York City. . . . Aspen had become simply another part of industrial America.”46

As with many western towns, Aspen quickly experienced boom and bust cycles. In 1892 the city was producing one-sixth of the total volume of silver mined in the United States. By 1893 Aspen had grown to become Colorado’s third largest city, but with significant accompanying ecological costs. As early as 1881, official reports emerged that pollution from the town’s sawmill was befouling the nearby rivers and streams, posing health risks to wildlife and to the residents who depended on the rivers for fish and drinking water.47 Moreover, timber cutting for use in the mines reduced nearby forested areas to dust within a short time. In nearby Garfield County, even after President Benjamin Harrison established the White River Plateau Timberland Reserve in 1891 (later renamed the White River National Forest by FDR), hunters wiped out animals for food and profit, driving many species to extinction. In 1895, a hunter killed the last native elk in the area, the final chapter in a short twenty-year span of time in which the animals were mercilessly slaughtered without regard for preservation.48 Deer, bears, grouse, mountain sheep, and fish nearly met the same fate, until local newspapers campaigned against such destruction.49

The social landscape of the Aspen area was also an exciting and dynamic space. The town soon became a site of intense class divides, with mine company investors and their socialite families on the West End of town, and mine workers living in cramped, makeshift housing in the East End. Moreover, the work of mining silver was as difficult, unrewarding, and lethal as anywhere in the West. Miners’ consumption, or silicosis (caused by inhaling silica dust), afflicted many workers in the mines around Aspen. The miners experienced shortness of breath and coughing along the road to a slow death. Near the turn of the last century at the Union-Smuggler Mine in Aspen, an underground fire took the lives of fourteen miners. For many years, tragedies like these were not followed by industrial reform because, legally, miners were responsible for their own health and well-being on the job, until modern occupational safety and health regulations were instituted in the twentieth century.50

Aspen developed a strong tradition of working-class populism and labor-union militancy in the late nineteenth century, partly because of the low wages and high risks associated with the work.51 Regrettably, as was the case elsewhere, such unionism often took on an anti-immigrant flavor because mine owners frequently pitted these groups against each other. During strikes in 1892 and 1893, for example, foreign workers were brought in to fill jobs at lower pay. The city also had a policy of placing indigent people on a train with a one-way ticket out of town, so there was little in the way of a social welfare ethic in this place of vast riches and hard luck. At the same time, a group of wealthy women in town started organizations such as the Women’s Home Missionary Society, St. Mary’s Guild, the Women’s Assembly of the Knights of Labor, the Women’s Literary Club, and the Ladies Aid Society. These groups raised funds for charity, for a lecture series, and for the general elevation of refined culture in Aspen.52

Aspen was not exactly a melting pot but had its share of ethnic and racial diversity.53 According to the 1885 Census, African Americans made up just 1 percent of the city’s population, and they generally worked in the service sector. An early newspaper laundry advertisement may have reflected their role in the community: “Mr. Pearce’s African can change soiled clothes to garments as white as snow.”54 The town’s population of thirty-two African Americans was, like many African Americans today, highly segregated from whites, even in church. An article in the Aspen Times reported that the “colored people, headed by Brother Jones,” held prayer services every week on Deane Street.”55 In nearby Glenwood Springs at the time, many of the professional servants were African Americans, several of whom were former slaves.56 There was one Mexican in Aspen, and not a single Chinese, as they were banned from the town. The local newspaper described Chinese as “surly, treacherous, and careless, and indifferent workmen.”57 Nearly one-quarter of the city’s population in 1885 was comprised of immigrants, the vast majority of them northern European.58 A great percentage of the persons living in Pitkin County, Colorado, (of which Aspen is the county seat) were from nations such as Ireland, England, Scotland, Canada, Russia, Wales, Denmark, Poland, Germany, and France. Some of the occupations they held were listed in the 1885 Census as miner, housewife, teamster, grocer, laundress, student, baker, restaurant cook, carpenter, laborer, dressmaker, freighter, blacksmith, butcher, bartender, civil engineer, mine foreman, saloon keeper, salesman, and lawyer.59 This was indeed a prosperous city during those heady economic times.

Then, with the Panic of 1893, everything changed. That year President Grover Cleveland overturned the Silver Purchase Act of 1890, which had provided price supports for silver producers. The repeal of the act drove the price of the precious metal down, dooming silver mines and all those whose fates were tied to them. Many workers and investors organized to stop this onslaught, calling the newspapers (such as the Denver Republican, the Denver Post, and the Rocky Mountain Sun) that embraced the demonetization “vile and contemptible.”60 Their efforts fell on deaf ears, however, and hundreds of thousands of people were thrown out of work almost overnight as mines across the West suddenly closed. There was some good news that year, however. In 1893, Colorado became the first state to approve women’s suffrage by popular vote. The Aspen papers supported this effort as well.61 But with the collapse of silver, the booster brigade had to step up to the plate and either market the town or watch it die.

Many towns in the nineteenth-century West were literally promoted into existence. Newspapers published advertisements and personal stories, while business organizations, railroads, and traveling salesmen were critical to getting the word out and getting investors and workers in. In 1872, the same year the Mining Act was passed (opening up public lands to private companies), the Colorado Territory set up a Board of Immigration—an agency whose purpose was to recruit immigrants to live and work in Colorado. The plan was to increase investment, improve the tax base, and make a successful bid for statehood, which they did in 1876.62 This was the first wave of the “sell Colorado” campaign that continues to the present day. Some of the many features of the territory that were emphasized in advertisements were its mild climate, ecological beauty, and mountain ranges, earning Colorado the label of “The Switzerland of America.”63 Another popular phrase in the booster lexicon was Colorado’s “champagne air,” which, along with its many hot springs, had a purported medicinal effect on visitors. Racism and Anglo supremacy were often coupled with these campaigns. One promotional venture for the town of Colorado Springs came with a description that the city was “a fine place to live because so few Irish polluted its refined atmosphere.”64

Published personal dictations of Aspen residents were an effective way to publicize a vision of prosperity. Newspaper editors and journalists (whose economic interests were tied to promoting the town to outsiders) would seek out and publish these accounts. Consider the dictation of Harvey Young, who spoke about his exploits in the Crystal City, as Aspen was known then: “Mr. Young took the Emma lode [a mine], something that was generally supposed to be worthless, sunk a shaft, and took out $75,000 in a month. Made several other good strikes. Regards Aspen today as the most promising mining camp in the state.”65

Continuing this tradition into the early years of the twentieth century—which was important, since those were the “quiet years” of economic recession in Aspen—the Colorado Board of Immigration published the following description of Pitkin County in 1916:

Why Come to Colorado? They who seek for wealth by delving into the bowels of the earth, may know that within the accessible fastnesses of our mountains lie buried, and awaiting development, untold millions which can be had by energy and well directed toil. . . . They who fancy the charms of unsurpassed scenery, varying with every light and shade, yet ever the same, come and look upon the lofty crags which lift their “awful forms” around, and crown our everlasting mountains. They who fear that the rigors of a variable climate will shorten their days, come to Colorado and take a new lease of life, by breathing the invigorating air which gives life and health to declining invalids.66

It is interesting that within this booster call, the Board of Immigration saw no conflict between promoting mining and maintaining the natural beauty and ecological charm of the area. This reflects a long-simmering tension in the American West wherein boosters and residents have emphasized the aesthetic attractions of the region, while also embracing a laissez-faire approach to tapping ecosystems for financial wealth.

The period between the Panic of 1893 and the late 1930s is commonly known as Aspen’s “quiet years.” It was a sleepy town, where some old-timers hung on to a dream that had long since faded in the shadow of the silver collapse. But even amid the inactivity and silence, changes loomed.

With the emergence of corporate capitalism, the completion of the transcontinental railroad, and the advent of new communications technology, one of the West’s now-permanent features bloomed: tourism. The notion of traveling in order to see something of interest was developed as an elite practice and promoted as a patriotic duty. Until that point in time, nearly all tourism in the United States centered on the East Coast. As the American West opened up, however, ancient ruins, natural wonders, and other sites became marketed under the government’s “See America First” campaign. This was an effort to build a new national identity that reinforced imperialist ventures across physical and cultural frontiers.

In the 1930s, when investors turned their eyes on the Crystal City once again, they had money, snow, and tourism on their minds. Aspen’s ski slopes first opened in 1936, but the dream was deferred when World War II broke out, and the nascent resorts closed down until the war was over. At that time, Walter Paepcke, an industrialist from Chicago, like the boosters of old, once again promoted this town into a renewed existence. Beginning with a nationally lauded celebration of the famed scholar Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s Bicentennial in 1949, Paepcke inaugurated Aspen’s rebirth as a city where great ideas, culture, and the enjoyment of nature could thrive and intermingle. With his Aspen Skiing Company, the Aspen Institute for Humanistic Studies, the Aspen Music Festival, and the International Design Conference, Paepcke created an exclusive space for the elite business class to network, hear lectures and music, and rejuvenate their minds, bodies, and spirits. The Aspen Institute’s lectures soon morphed into “the Executive Seminar,” specifically created for leading corporate executives who could attend conferences, take in a concert, and rest far away from the fast-paced life of the cities.67

Paepcke’s vision reveals the heart of contemporary Aspen. He sought to create a getaway for those executives who could enjoy nature while relaxing from hectic jobs; then they could return to those jobs refreshed and resume their corporate activities with renewed vigor. This is central to the Aspen Logic—that what is good for the executives is good for society, that a top-down approach to social planning and politics is best for all, and that capitalism, environmental sustainability, and democracy are intimately compatible.

The highbrow facelift promoted by Paepcke and other boosters did not sit well with many old-timers, who would have appreciated some acknowledgement of Aspen’s proud mining history and working class presence. As one former miner put it, “Gallons of printer’s ink to lure the tourist! And not a drop of ink to tell the world where we stood, back in the Eighties,”68 exhibiting the pride that many locals feel about Aspen’s boom town days in the 1880s. But the plan to build the “American Salzburg” would not be sidetracked by working-class nostalgia. Paepcke was a genius at bringing media coverage to this mile-high town. One national magazine boldly proclaimed that as of 1950, Aspen was the nation’s “intellectual center.”69 Another magazine declared, “Accommodations in Aspen are suited to all tastes and pocketbooks. . . . Today the old-timers and the visitors agree that Aspen has never been a ghost town and that now it’s the melting pot on top of the nation—in Colorado.”70 Despite such generous proclamations, however, Paepcke’s plans were always more socially specific: to create a place where white, elite, ecological privilege reigned supreme. In October 1950, the Saturday Evening Post reported:

The rise in property values that accompanied Paepcke’s development in Aspen was welcomed by some and feared by others who became priced out of the market. And an unfortunate rumor went around at one time that Paepcke no longer wanted the “local peasants” to make a social center of the Jerome Hotel.71

Aspen was to become a town for the rich, while working-class folks, people of color, and immigrants by necessity had to live down valley and work in a support capacity in the service of that fantasy. As one reporter stated around the time of Aspen’s rebirth, “One of the nicer things about the capitalistic system is that it permits enough private money to accumulate now and then to make possible a venture like Aspen, Colorado.”72 Therefore, despite claims that the marketing of Aspen was a mass advertising campaign, it was a targeted promotional effort aimed at a limited demographic group.

Back during Aspen’s quiet years, the town leaders and would-be boosters carried on a continuous chatter about how to recapture the magic and return the town to its former greatness. In a typical 1913 newspaper article, the author lambasted Aspenites for behaving like “mossbacks”—lazy and unwilling to get the word out to tourists and “sell” the town.73 Apparently, with Paepcke’s help three decades later, they eventually did. So much so that by the 1960s, Aspen’s marketing “problem” was that they had been too successful, as evidenced by the growth in population and development in the area, and by the presence of some new undesirable social elements—hippies.

A place like Aspen was heaven on earth for hippies, or at least, hippies with money. Known variously as flower children or, today’s term of choice, “trustafarians,”74 these free spirits by choice are said to have taken over cities like Berkeley, Portland, San Francisco, and Boulder. Aspen was also on that list; in the 1960s and early 1970s those long-haired nature lovers were flocking to town. According to one report, Aspen was so popular among this set that one hippie reportedly hijacked a blimp in California and attempted to fly it to the Crystal City.75 The hippie “problem” rubbed Aspen’s elite the wrong way, and they pushed the city leaders to pass a vagrancy ordinance, which led to many instances of harassment and arrests. The Aspen Times sided with the cause of civil liberties and took a huge hit when advertisers organized a boycott of the paper (business leaders were, after all, the main force behind the vagrancy ordinance). Eventually, the ACLU brought a class-action lawsuit against the town in 1968. Even though a federal judge in Denver refused to rule on the issue, three months later the city repealed the vagrancy ordinance. Soon after, the Colorado Supreme Court ruled such laws unconstitutional, including a similar one on the books in Denver.76 Aspen has, since its founding, had both prominent progressive and reactionary elements among its denizens. The following two editorials illustrate this divide:

Aspen is tourist oriented and must do all it can to attract and satisfy tourists if it is to exist and prosper . . . the hippie movement is as radical and undesirable to the essence of Aspen as can be produced by any group or individual. This conglomeration of disenchanted misfits who are unable and unwilling to meet the competition which prevails under the long-established concept of society in America would foster their level of existence upon others, dragging down everything with them. Some methods of control must be put into use in Aspen.77

One cannot compare Aspen to Germany during World War II. But certain similarities exist between the condition in Aspen today and the early years of Nazi rule. There are the brown-shirted bully-boy police who seem to delight in harassing and apprehending those people who appear poor, ill-dressed, ill-shaved or ill coiffed. . . . It is time for the City Council to recognize the evil it has created and to take steps to end this reign of evil and injustice.78

The controversy over hippies was part of the larger and ongoing conflict over Aspen’s future. While everyone wanted a prosperous Aspen, many people felt that commercial and residential growth had gotten out of hand. Anti-growth or growth-control sentiment gained support during the 1960s. One resident at a town hall meeting at the time suggested placing a sign with the word “FULL” on it at the city limits.79 This might be thought of as the more respectable version of the “All Chinamen will be shot” sign that appeared outside Leadville in the previous century. Today, Coloradans defiantly sport bumper stickers on their SUVs and Subarus bearing the message “No Vacancy.”

Aspenites wanted growth control and open-space preservation, and over the years they tried to institutionalize these goals, with varying degrees of success. Nongovernmental organizations sprang to life and stepped up to fight developers and urge the city council forward on these issues. Groups that formed on short notice in the late 1960s for this purpose included Citizens for a Better Aspen, the Pitkin County Park Association, the Aspen Valley Improvement Association, the Roaring Fork Foundation, and the Aspen Liberation Front.80 People were troubled about threats to their enjoyment of a peaceful and exclusive environment, including a development plan that might add 45,000 new people to the valley; Texas International Petroleum’s plan to purchase a green space just to the west of Aspen for a megadevelopment; and a proposed widening of Highway 82 to four lanes.81 Joe Edwards, an Aspen attorney, and several other local activists formed yet another group called Citizens for Community Action. Edwards told a newspaper reporter, “We cannot stop all growth, but we can regulate it to ensure open space and the preservation of our ecology.”82

The city responded and produced the “Aspen Area General Plan” in 1966. This growth-management plan was an effort to accommodate future economic development in a way that would “retain the fine balance between man and his environment, the essence of Aspen’s character.”83 In 1970 the city council approved a 1 percent sales tax to be used toward the purchase and maintenance of open space. The council hired a full-time planner, bought up a prime half-block near the base of the mountain to stave off further development there, and in 1974 the council approved a law protecting mountain views from downtown Aspen so that no new construction would be allowed if it blocked the scenery.84 It soon became evident that the earlier growth-management plan was having limited success because it was designed to channel the “right kind of growth,” not limit growth altogether.

In 1977 the city put forth an updated plan. Only a 3.47 percent growth rate would be allowed annually, and this was enforced via the issuance of building permits through a quota system resembling the plans that Petaluma, California, and Boulder, Colorado, had already adopted (these two cities are also excellent examples of white environmental privilege in action). Aspen took the quota system an additional step forward by extending it to the main business district.85 For those who wanted to visit or live in Aspen and whose salaries placed them below the ranks of the upper economic class, the town was becoming increasingly unaffordable. Aspen’s plan, like many growth-management plans based on limiting growth, created a housing scarcity that rapidly increased prices and reduced the supply of affordable places to live. These growth-management plans were multifaceted, and contained potentially important and beneficial ecological elements to them, but they also produced greater social inequalities. The anti-growth ethic in Aspen was tested again and again during the 1970s and 1980s, and was slowly being chipped away as the power and reach of the town’s elite became clear. As one plaintiff stated, regarding a lawsuit brought to allow him to develop 115 acres in Aspen during the early 1980s, “There has been a change in the general public mood and the law from the early ’70s ‘no growth’ to ‘reasonable growth.’”86

Aspen is a complex place, and city leaders, residents, and activists must be credited with being progressive and socially open-minded from time to time. Consider the passage, in 1977, of a pioneering anti-discrimination law by the city council. The law prohibits discrimination in employment, housing, public services, and accommodations. It makes unlawful:

any act or attempted act, which because of race, color, creed, religion, ancestry, national origin, sex, age, marital status, physical handicaps, affectional or sexual orientation, personal appearance, family responsibility, political affiliation, source of income, place of residence or business which results in the unequal treatment or separation of any person, or denies, prevents, limits, or otherwise adversely affects, the benefit or employment, ownership or occupancy of real property or public services or accommodations.87

This is an expansive, far-reaching, and generous law, way ahead of its time. Of course, it is not difficult to abide by a law that prohibits discrimination against groups that cannot even afford to visit—let alone live or work in—the town.

Similarly, there have been attempts at building affordable housing in Aspen, but nearly everyone we asked about it had the same reaction: loud, throaty, and therapeutic laughter.88 The point was that affordable housing in Aspen is a contradiction in terms. Moreover, the symbolism of real affordable housing in the imaginations of many wealthy white Aspenites is similar to that of many whites and middle-class communities nationally: it is unwanted and associated with people of color and the working classes. One Carbondale City trustee Alice Hubbard Laird put it this way:

So I think there’s a lot of basic sympathy for wanting to keep the air clean, but also varying levels of hypocrisy at the same time. Aspen has been really great and progressive on arts, transportation, energy, and open space. At the same time there’s this big brouhaha around an affordable housing development up there, with people complaining about sprawl. So you’re going to complain about that sprawl, but not complain about sprawl down valley and the long commutes?! . . . there’s that odd hypocrisy where they’re saying “we want our little corner of the world to be very pristine” and then a development less than two miles outside of town, where people wouldn’t have to drive forty miles to work, to some of these staunch environmentalists it’s horrible.89

By the early 1960s, Colorado’s economy shifted from mining and extractive industries to one based primarily on tourism. The silver mining economy had hit rock bottom decades before, so this was a chance for a rebirth. State boosters successfully marketed the natural beauty that had, in a previous era, netted billions of dollars in mineral wealth, to attract visitors from out of state.90 Ironically, the resulting nature-loving activities have taken a great toll on the West. Tourism, hiking, camping, and skiing have grown in ways that the Sierra Club founder John Muir could never have anticipated. Outdoor recreation has become one of the most significant activities impacting the ecological integrity of Western lands.91 Skiing in particular has damaged the West’s ecology, despite its eco-friendly image. One author writes about the faux snow that is used on so many ski slopes in the West:

Snowmaking isn’t a zero-pollution activity; it’s an elsewhere-pollution activity. . . . In the West, where most electricity is produced by coal-burning power plants that release significant quantities of sulfur dioxide, the precursor to acid rain, the air pollution impacts of snowmaking are exponentially greater. Here, snowmaking is a form of alchemy, of turning coal into snow. In Colorado, 94 percent of electricity is generated by coal-burning power plants. If a ski area pays a million dollars over the course of a winter for electricity to run its snowmaking compressors—not an unreasonable amount by today’s standards—it has paid its utility company to burn fourteen million pounds of coal, which produced thirty million pounds of airborne carbon dioxide, the leading greenhouse gas that causes global warming, and, by extension, may be altering weather patterns in ways that will make commercial skiing in the United States a thing of the past during the twenty-first century. Much of the power for ski resorts in Colorado comes from the Hayden power plant in northwest Colorado. This plant, the region’s largest producer of sulfur dioxide, was found by a federal court to have violated clean air regulations 19,000 times in five years.92

Contributing further to ecological woes associated with skiing are the air and automobile traffic that comes with ski tourism, and the machine grading of mountain slopes and artificial snow produced at many resorts, both of which cause long-term damage to the vegetation and can take decades to recover.93

In response to these kinds of allegations, the National Ski Areas Association recently published a report titled “Sustainable Slopes: The Environmental Charter for Ski Areas.” The report declared skiing a pro-environment activity and, through voluntary principles that it hopes ski resort operators will choose to follow, predicted that the industry will soon reach a state of sustainability. The resort association’s president, Michael Berry, stated, “Resorts across the country are well on their way to implementing environmental practices and programs that will ensure a sustainable future.”94 Vera Smith, the conservation director for the Colorado Mountain Club, critiqued this report as an example of self-monitoring that ignores the larger ecological footprint of ski resorts. Concurring with a number of respected experts, Smith declared, “The real impact of ski areas today is expansions and the commercial development in and around the ski areas. . . . It’s the condos and the strip malls and everything else that comes along in the valley and by the river, which is the ribbon of life for that area. The “Sustainable Slopes” [report] deliberately did not address those issues.”95 Or as the activist Nicole Rosmarino put it so succinctly: “I see skiing as just another extractive industry.”96

But the ski industry would not be half what it is today if not for the subsidies that resort developers enjoy through their privileged access to public lands. The U.S. government gives ski resort developers rights to build and expand on federal land all over the western United States, in a way that parallels the subsidies given to mining and other extractive industries operating on public lands.

Perhaps a predictable outcome of this control over land and nature by the ski industry is ecotage—the deliberate sabotage of machines or other symbols of industrialization by activists who believe these instruments do great harm to ecosystems. In October 1998, the Earth Liberation Front (ELF) took credit for torching the Two Elks Lodge on Vail Mountain, apparently in response to the planned expansion of the resort and the possible threat that move would have posed to the habitat of the endangered lynx. The federal government labeled this action the costliest act of “ecoterrorism” in U.S. history.97 The incident called into question developers’ and skiers’ self-proclaimed roles as environmentalists and avid nature lovers. The ELF may have spoken a dirty truth by calling these elites the primary threat to sustainability. In response, it seems that some of those who enjoy and benefit from these ski resorts have found a convenient scapegoat in order to distract people’s attention from their immense contribution to environmental degradation.

There were efforts to rein in growth decades earlier at the local and state level. California was the gold standard for urban sprawl and out-of-control growth. Accordingly, one bumper sticker popular among Colorado anti-sprawl advocates in the early 1970s read “Don’t Californicate Colorado.” And, while the present day spike in anti-immigration politics has a long history in Colorado, it is also part of the broader anti-growth politics evident in that state since the 1960s.

Many laws were passed and numerous officials elected on growth-control platforms in the late 1960s and 1970s in Colorado. The statewide Land Use Act of 1970 required all sixty-three counties to develop plans to control growth, particularly the increase in housing subdivisions in the rural and mountain areas. Evidently, this law had little impact on deterring growth because the housing and tourism boom continued. Richard Lamm ran for governor of Colorado in 1974 and placed environmental issues at the top of his campaign. He, Gary Hart, and Timothy Wirth all ran for elected positions and prominently stressed environmental protection themes that year. The election was buttressed by the recent memories of Lamm’s 1972 campaign to challenge Denver’s bid for the 1976 Winter Olympics on the grounds that it would only exacerbate future growth. Lamm successfully ran the Olympics out of town and was elected Colorado’s new governor.98 He billed himself as new blood in a state where the establishment politicians promoted a “sell Colorado” mentality to the outside world in order to secure capital investment for the state’s economic stability.

Lamm and others were publicly more concerned about quality-of-life indicators, and Lamm specifically noted that overpopulation and immigration were part of the problem.99 Lamm, a longtime nativist, ran an unsuccessful campaign for election to the Sierra Club board of directors on an anti-immigrant and population-control platform in the 1990s. George Stranahan told us that in Aspen, “We have the Dick Lamm Syndrome, which is overpopulation will be the death of all of us and tourism too and immigrants are a large part of creating overpopulation issues.”100 Aspen activist Rebecca Doane agreed with Stranahan when she told us “he’s [Lamm] a fairly radical—in my opinion—right-winger who, if it were up to him he’d close the borders. So he occasionally shows up around here trying to get the INS to run people out of here.”101 Lamm has served as chair of the Advisory Board of the Federation for American Immigration Reform (FAIR)—one of the most prominent and respectable nativist groups in the United States—and became infamous for giving a speech in which he argued that bilingualism and multiculturalism will “destroy America.”102

But Lamm also exhibits a populist and anti-corporate streak. He once vowed, “We’re not going to let exploiters rip us up and rip us off . . . I know that just as soon as some Eastern politician’s constituents get cold in the winter, he’s going to say ‘screw Colorado.’”103 Colorado has vast coal, crude oil, and natural gas deposits that are exploited for energy consumption, and the animosity toward eastern capitalists who habitually and historically use the state as a resource colony remains strong to this day. After becoming governor, Lamm once cautioned, “We don’t want to be a national sacrifice area.”104

No-growth politicians and propositions continued gaining ground in Colorado during the 1970s. The cities of Fort Collins and Colorado Springs elected anti-growth city council members, and Boulder passed a measure that limited new housing construction to four hundred units per year, while also buying up large tracts of rural land to create a “greenbelt” around the city. But eventually, the call of the beautiful Rockies, the bucolic meadows, and open space were too strong for tourists and retirees to resist. The magnetic force that Colorado’s natural wealth has long had on investors was also too powerful to ignore. The state’s growth trend continued upward. Figures from the 2000 Census show that since 1990, there was growth in every county in Colorado’s Western Slope but one. Eight counties experienced growth rates higher than 50 percent, and five of them grew by more than 80 percent. With the state’s established history of anti-growth sentiment, such jumps were troubling. In the minds of nativists, the source of this growth was clear. But was immigration from south of the border the primary culprit? The Colorado state demographer Jim Westkott stated, “The second homes are the driver (of population increases), more than anything. . . . We’ve had seven, eight years of very strong second-home development in some of those counties, and it looks like it’s going to stay pretty strong.”105 It is unlikely that many of the immigrants coming to work in Colorado’s service and construction industries are these second-home owners. In fact, according to one custom home-builder on the Western Slope, typical buyers are semi-retired or retired engineers, stockbrokers, and dentists.106

The growing divide between the have-mores and have-nots in America has been called “the Aspen effect” because that city is an excellent, readymade, localized example of how capitalism in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries has culminated in shocking extremes of wealth and poverty, of riches and rags, of profit and misery.107 Ski resorts across America reflect this pattern of social violence, which is also mirrored nationally in virtually every city and state. The writer Harlan Clifford may have said it best when he wrote, “The lesson from Europe and from our own destruction of communities in the name of progress is that the time has come for Americans to set aside the concept of manifest destiny.”108