K. A. Jayaseelan

IN THIS PAPER I present a series of arguments for postulating a functional projection of Focus above vP. I also postulate an iterable Topic Phrase above this Focus Phrase.

The postulation of IP-internal Topic/Focus projections will be shown to lead the way to a new view of the difference between the clause structures of SOV and SVO languages, and to some interesting results about clause-internal scrambling and object shift in such diverse languages as Malayalam, German, Dutch, Yiddish and Scandinavian.*

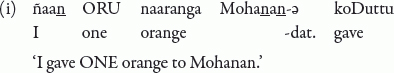

Many languages have a requirement that a question word should be contiguous to V.1 In Malayalam, although the natural way to ask a question is by clefting, a non-cleft question is possible under one fairly strict condition: the question word must be placed immediately to the left of V (in a position “normally” occupied by the direct object if one is present, Malayalam being an SOV language):

Even the clefting in questions, one can now see, is possibly a device for positioning the question word next to V:

In a cleft construction, the main verb is the copula; and the question word comes immediately to the left of the copula.2

How do we generate this position of the question word? Starting from an underlying SOV word order of the type traditionally assumed in South Asian linguistics, it is difficult to see how one can generate a COMP-like position “within VP”. Equally impossible are the “downward” movements we would need to postulate, to move (say) the subject into this position (cf. (1a)); this is illustrated in (6):

However, we can avoid these problems if we may assume a universal ‘Spec-Head-Complement’ order (Kayne 1994); and say that the surface order of the verb’s internal arguments in SOV languages is the result of the raising of these arguments into SPECs of higher functional projections. While the subject raises to SPEC,IP, the internal arguments raise to SPECs of functional projections which are intermediate between IP and VP. In the case of a monotransitive verb (e.g.), the two movements shown in (7) would be the “normal” movements of an SOV language. ((7) is anticipated, for Dutch, in Zwart (1993).)

Given this picture, all we need to do, in order to generate the question word’s position next to V, is to postulate a Focus Phrase (FP) immediately dominating vP, and to say that the Q-word moves into the SPEC of this FP. All other arguments (and such adjuncts as are generated within vP, e.g. manner, location, time adverbials) would now move “past” this position into SPECs of higher functional projections by the normal movements which derive the SOV word order. In the case of (1a), e.g., the subject is a Q-word and moves into SPEC,FP and the direct object moves “past” it, as shown in (8):

(V adjoins to v; there is reason to think that [v V-v] adjoins to Focus.3)

(Let us note at this point that some proposals in the literature for functional projections “in the middle” of vP/VP are irrelevant for our purposes. Koizumi’s “split VP” hypothesis (Koizumi 1994) has an AGRoP “between” a higher VP in which the subject is generated and a lower VP in which the internal arguments are generated; Collins & Thrainsson (1996) add a TP immediately above this AGRoP:

Note however that these “intermediate” functional projections are lower than the subject’s base position; even if we were to add (say) a CP immediately above the TP of (9), the subject will have to be “lowered” into it to generate a sentence like (1a).)4

In what is usually taken to be “the VP” of SOV languages, the canonical order of elements is: Adjunct—IO—DO—V; cf. (10):

As a comparison of this sentence with its English gloss shows, the order of elements is the mirror-image of English:

The movements out of the VP that we postulated for SOV languages are apparently “nested” movements.5

Interesting questions arise about Relativized Minimality. How do these movements escape minimality effects? There are two sub-questions. One, if SPEC,FP is filled, how do these movements go past it—or (indeed) past SPEC, vP (the “VP-internal subject”)? Two, why are there no inter se minimality effects among them; e.g. why doesn’t the landing site of the direct object prevent the indirect object moving to a higher position? The problem (of course) is that the Malayalam V does not raise any higher than the head of FP (as we just said).6

It has been recognized (however) that we need to postulate two types of movements: one, instantiated by Icelandic object shift, which obeys minimality; the other, instantiated by scrambling in Dutch, which does not obey this constraint (Zwart 1993, Diesing 1997).While the reason for this distinction remains puzzling—especially since both types of movement have many things in common; e.g. they obey a common ‘definiteness/specificity’ constraint -, let us for the time being simply say that the migration of arguments and adjuncts out of the VP (in SOV languages) is a case of scrambling.

What are the functional heads, higher than FP and lower than IP, which host these moved phrases? It has been claimed for the COMP system (Rizzi 1997), that there are any number of Topic Phrases possible above the FP in COMP; assuming a similar possibility with respect to the FP above vP, it is tempting to say that the “normal” movements of the internal arguments (and adjuncts) of SOV languages are to SPEC,TopP.7

This solution has a seeming advantage: repeated applications of Topicalization should be able to produce any order whatever of the elements that undergo the operation. I.e. the base order of these elements can be arbitrarily reordered. This should be able to generate “scrambling” understood as the free order of a verb’s arguments (which is the “classical” view of scrambling). This advantage however is outweighed by other considerations. Firstly, it cannot account for the canonical order of the verb’s internal arguments, the one which we tried to describe in terms of “nested” movements.

But the really serious problem is that the internal arguments in their canonical order—as, for example, in (10)—do not show any topicalization effects. Topics are familiar information in the discourse; they are entities which have already been mentioned, and are therefore definite or specific. (In fact, we shall be arguing that the leftward movements showing a definiteness/specificity effect in Scandinavian, Dutch or Yiddish are instances of topicalization—specifically, of movement into TopPs above FP.) But there are no definiteness/specificity constraints on the Malayalam verb’s internal arguments in their canonical order; cf.

It is difficult to imagine why the indefinite NPs in (11)-(13) should be topicalized.

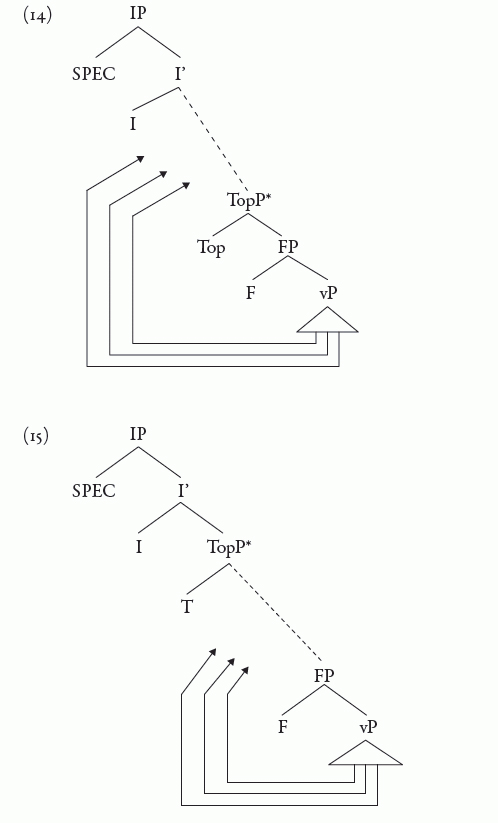

Our “nested” movements (then) are not into Topic Phrases.8 However, suppose we do postulate iterable TopPs above FP in Malayalam also—on the evidence of the European languages, to which we come back presently. Do we say that the “nested” movements that we are postulating are into positions higher than TopP*, or lower than TopP*? I.e., is (14) or (15) the correct picture?

When two definite arguments interchange their positions, it is difficult to say which one is topicalized; e.g.

The IO-DO order of (16a)/(17a) is the canonical order; the scrambled order DO-IO of (16b)/(17b) could have been produced either by the IO moving (from vP) into a TopP below the canonical position (assuming (14)),9 or by the DO moving (from vP) into a TopP above the canonical position (assuming (15)). This can be schematically represented as (18). (The “unoccupied” canonical position in each case is indicated within parentheses.)

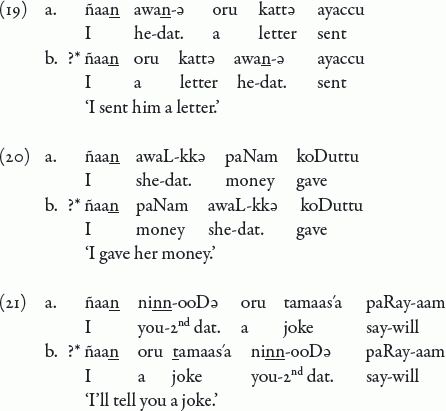

However, if one of the arguments is indefinite, we get some interesting results. Cf.

If the interchange of positions in the (b) sentences is due to IO moving into a TopP below its canonical position, it is difficult to see why these sentences are unacceptable, since a definite pronoun is always amenable to topicalization. On the other hand, if what is happening in the (b) sentences is the movement of DO into a TopP above its canonical position, the ungrammaticality of these sentences is explained: an indefinite (nonspecific) NP has been (illicitly) topicalized. These data (then) support (15) over (14).

As a matter of fact, if the IO is indefinite and the DO definite—the reverse of what is the case in (19)-(21) -, the canonical order is somewhat awkward! This is especially so, if the DO is a pronoun, cf.

If what is happening in (b) is the IO being topicalized in a position lower than its canonical position, the acceptability of this sentence is puzzling—since an indefinite NP is being topicalized. But if the (definite) DO is being topicalized in a position higher than its canonical position, the complete acceptability of the (b) sentence is unsurprising.10

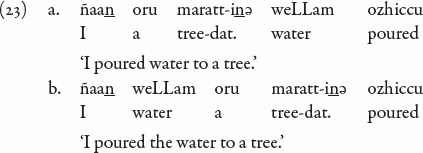

A very interesting pair of sentences which helps us to choose between (15) and (14) is the following:

In Malayalam, the definite article is null. This means that in itself, a form like weLLam (‘water’) is ambiguous between a definite and an indefinite reading. In the (a) sentence, which has the canonical order, the most natural interpretation of weLLam is as ‘(some) water’; i.e. the argument is indefinite. But in the (b) sentence, which has the inverse order, the only permissible interpretation of weLLam is as ‘the water’; i.e. the argument is obligatorily definite. (The (a) sentence could be an answer to the question ‘What did you do?’ The (b) sentence could only be an answer to the question ‘What did you do with the water?’) This definiteness constraint on weLLam in the (b) sentence is explained if it is a Topic. I.e., in effect, we are choosing the structure shown in (15), and saying that the DO is topicalized in a position higher than its canonical position. But if we were to choose (14) and claim that it is the IO which is topicalized in this sentence, in a position lower than its canonical position, then we end up with two problems: Why is there a definiteness constraint on the DO, which we are now saying is in its canonical position? How can an indefinite and non-specific NP like oru maratt-inə (‘one tree-dat.’) be topicalized?11

We (then) choose (15) as correctly representing the configuration of TopPs with respect to the canonical positions of arguments in SOV languages.12

However recall that in Rizzi’s (1995) articulation of the COMP system of IP, there are TopPs both above and below FP (see fn. 7). Is there any evidence of TopPs below FP in the COMP system of vP (also)? Consider the following sentences:

If we may assume a TopP below FP, we can readily explain the post-verbal elements in these sentences. We can say that these elements are in this TopP; and that (furthermore) aarum ‘nobody’ (a negative polarity item) in (24), and aarə ‘who’ (a question word) in (25) are in SPEC,FP, and that V has raised and adjoined to F.

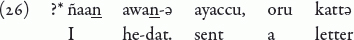

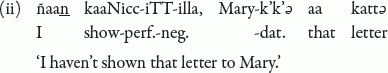

Tirumalesh (1996) was the first to claim (to my knowledge) that in Dravidian, the right-of-V elements are Topics. He pointed out that “(non-generic non-human) indefinite noun phrases” were unacceptable in this position. Thus consider (26):

(26) is as unacceptable as (19b) (repeated below), or (27) (where the indefinite NP is in a Topic position above IP):

Our postulation of a Topic position below FP (and therefore below the canonical positions of the verb’s internal arguments) may appear to compromise our explanation of sentences like (19)-(21), in which a definite IO and an indefinite DO interchange their linear order. (19b) has been repeated in the last paragraph. Our explanation of its ungrammaticality was that the indefinite DO oru kattə ‘a letter’ has been topicalized. But surely, the same word order could be obtained by moving the definite IO awan-ə ‘he-dat.’ into the below-FP Topic position? The fact of the matter is that (for unclear reasons) the below-FP Topic position is entirely ‘defocused’ and seems to induce obligatory V-raising past it. In fact, this position seems infelicitous if it does not occur in association with FP, to the head of which V raises and adjoins. Cf. (28):

(28a) has the canonical word order. In (28b), aa pustakam ‘that book’ has been moved into a pre-subject Topic position, which is fine. The unacceptability of (28c) is due to the fact that there is no F to induce V-raising. In (28d), ñaan-um ‘I too’ is in SPEC,FP and V adjoins to F; and the sentence is fine.

However, the fact that the below-FP Topic position invariably appears (in linear terms) post-verbally, suggests also another analysis of these data. Consider (29) ((29b)=(24)):

In the (a) sentence, aana-ye ‘elephant-acc.’ is plausibly in a pre-IP Topic position. The (b) sentence, we could suggest, is derived from the (a) sentence by preposing IP to the SPEC of a still higher functional head (say, a higher TopP). To account for the marginal status of a sentence like (28c), one could now say that IP-preposing requires a focused element in the IP.14

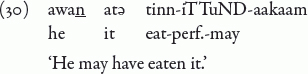

In fact, the preposing of IP and VP must be assumed to take place quite generally in Malayalam, as a result of the familiar property of SOV-language verbs of moving their arguments to the left (the “nested” movements to canonical positions that we spoke of)—but extended now (at least in Malayalam) to auxiliary verbs and the verbal complementizer. First, note that the auxiliary verbs are stacked on the right-hand side of the lexical verb, in the inverse order of English; e.g.

The VPs headed by the auxiliary verbs, we may assume, are generated still higher than the Topic and Focus positions—and the “sandwiched” canonical positions—that we investigated. We can reasonably claim that the auxiliary Vs share with the main V the property that their arguments vacate their base positions which are to the right of V. In the case of each auxiliary V, its complement raises, possibly to its own SPEC position. Repeated applications of this movement give us the inverse order of the stacked auxiliary verbs at the end of the main V.15

The Malayalam complementizer ennə, which occurs at the right edge of the embedded clause, is also a V: historically, it is a non-finite form of a verb meaning ‘say’. We may assume that it is generated as the head of the Finiteness Phrase in the Malayalam COMP system; and that it induces its complement IP to move to its left.16

Our clause structure of Malayalam has interesting explanations for some word-order phenomena of the “middle field” of the Dutch and German sentence.17

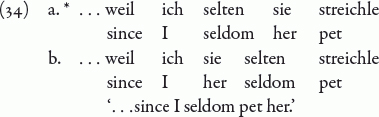

In the unmarked order, the indirect object precedes the direct object in German. The reverse order can be produced by scrambling, but this is subject to the following definiteness condition (Lenerz 1977:54, cited in Abraham 1986:17):

Consider (32) (below). The (a) sentence gives the neutral order; the (b) sentence is acceptable; but the (c) sentence is ungrammatical (Abraham 1986:18):

We have seen the same definiteness condition in operation in the scrambled DO-IO order in Malayalam. The same explanation should carry over. German and Dutch, we can say, are “SOV languages” in the same sense in which Malayalam is an SOV language: all the arguments and adjuncts of a V-initial VP move out of the VP (by nested movements) to a set of “canonical positions”—which are higher than a Focus Phrase18 but below a (set of) Topic Phrase(s). The scrambled order of (32b) and (32c) is generated by the direct object being topicalized. Lenerz’s definiteness condition can now be explained: an indefinite NP which receives an existential interpretation is necessarily ‘new information’ and therefore cannot be a Topic.

There is apparently an adverb position (in German and Dutch) immediately below the TopP, and above the canonical positions. In traditional generative analyses of German or Dutch as an SOV language, this adverb position was taken as adjoined to VP. The adverb was used as a diagnostic of scrambling: any phrase which was to the left of the adverb was taken as having moved out of VP. Interestingly it has been noticed that the position to the left of the adverb shows a definiteness effect—a fact which is unexplained if scrambling is a purely ‘optional’ movement. Thus Diesing (1997) observes that definite NP objects in German are under “pressure” to scramble (examples from Diesing (1997: 378, 380); ‘M’ means ‘marked’):

And pronominal objects must scramble:

In our terms, these facts indicate that there is a preference for topicalizing definite NP objects in German; and in the case of a pronoun topicalization is obligatory.

An indefinite NP object which has scrambled cannot have an existential interpretation, but acquires a specific reading (as observed by Diesing 1997, for German; Zwart 1996, De Hoop 1992, for Dutch); cf. the following Dutch examples (Zwart 1996:91):

Again, this fact follows from our claim that a scrambled phrase is topicalized.

There is a well-known alternative account of this definiteness/specificity effect of scrambling, offered by Diesing (1992,1997) and De Hoop (1992). This account says that VP is the domain of existential closure; but a definite NP—which introduces a free variable in the semantic representation—must not be existentially interpreted and so must move out of VP in order to “escape” existential closure (see Diesing 1997: 378-379). However an indefinite NP may either remain in the VP and get an existential interpretation; or scramble out of VP and get other types of interpretation (e.g. a specific interpretation) (Diesing 1997: 377). Observe that this explanation hinges on the assumption that the NP object in its canonical position (in German or Dutch) is within VP. It is obviously incompatible with German or Dutch being an SVO language.

Zwart (1996), trying to maintain that Dutch is SVO, attempts an alternative account in terms of prosodic factors. He notes that a non-D-linked (existentially interpreted) indefinite NP must bear pitch accent; a D-linked (specific or generic) indefinite NP is deaccented. Since the three adverb types of Dutch have their own intonational requirements, the positioning of NPs vis-a-vis these adverbs is determined in response to these requirements.19

Our explanation of German and Dutch scrambling in terms of a movement to Topic is different from either of these other accounts in the following respects. Unlike the Diesing/De Hoop account, it is consistent with these languages being underlyingly SVO. It seems more generalizable than the Zwart account; since Malayalam scrambling shows the same definiteness/specificity effect without any adverb figuring in the data.20

It has been observed that scrambled objects in Dutch and German license parasitic gaps (see Zwart 1996:50 and references cited there). Zwart gives the following Dutch example:

Since it is known that Topics are licensers of parasitic gaps, cf.

our account of scrambling readily accommodates this property. (It is difficult to see how an account in terms of prosodic features can account for it.)21

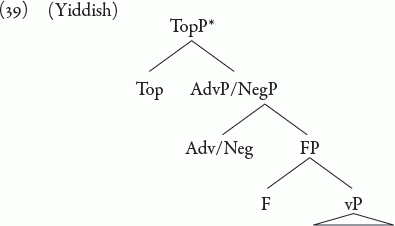

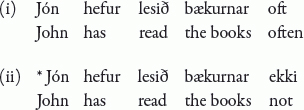

Contrasting two closely related languages—German (an SOV language) and Yiddish (an SVO language22)—gives us very interesting confirmation of the structures we have postulated. Since we assume a universal SPEC-Head-Complement order (and therefore a V-initial VP in all languages), for us the difference between SOV and SVO languages is (crucially) the following: SOV languages generate the “canonical” positions—above Focus Phrase and below Topic Phrase(s) and an adverb/neg position—into which they move (by “nested” movements) all the (unmarked) arguments and adjuncts in the VP. SVO languages do not make use of this option. The two contrasting structures we have argued for are the following:

(38) (which may be compared with the lower part of (15) which we adopted for Malayalam24) differs from (39) in having the “canonical positions” (indicated by a dotted line), into which the “nested” movements go.

Now consider a definite DP which occurs to the right of an adverb (and to the left of the verb) in German. We know that in German, a definite DP does not normally stay in its canonical position because there is a strong preference for it to be topicalized—i.e. it normally occurs to the left of the adverb position. Therefore, if it is to the right of an adverb, it could only be because it is contrastively (or otherwise) focused, i.e. it is in Focus Phrase. This prediction appears to be correct, cf. (33a) (repeated below) which is perceived as exhibiting a marked order and is acceptable only if die Katze ‘the cat’ is focused:25

An indefinite NP is under no pressure to scramble. Therefore an indefinite NP in the same position, i.e. to the right of an adverb and to the left of the verb, is most probably in its canonical position; here it is existentially interpreted. However it could also be in the Focus Phrase, in which case it will bear contrastive stress.

Now consider Yiddish. The Yiddish indefinite NP is normally placed to the right of the verb, which is its base position. But the definite DP must move to the left of the verb—in fact, to the left of the adverb position, i.e. it must normally be topicalized. Cf. (40) (examples from Diesing 1997):

Now consider the sentences in (41) which have an NP between an adverb and the verb (Diesing’s examples):

Given the structure (39), the NP in question can only be in the Focus Phrase. This prediction is correct, because both the definite and the indefinite NP are obligatorily interpreted as contrastively focused (as shown in the gloss). As Diesing points out, the interesting contrast is with the German indefinite NP in the same position, which has an unmarked (non-contrastive), existential interpretation. This contrast is explained by the presence of the “canonical positions” above vP in German, but not in Yiddish.

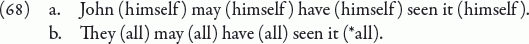

Diesing notes that the position between the adverb/neg and the verb in Yiddish can accommodate only one constituent, but that the position to the left of both the adverb/neg and the verb can accommodate more than one constituent. Cf.

These facts again are predicted by our postulated structures, which have only one Focus Phrase but iterable Topic Phrases.

Thus we see that our structures (38) and (39), for SOV and SVO languages respectively, make just the right predictions in every case. We take this to be strong confirmation of our analysis.26

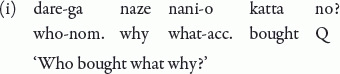

In multiple questions in Malayalam, question words are “stacked” in the Focus position:

The ungrammatical variants given below are meant to show that every question word must move into the Focus position.

We can try to understand this “stacking” in terms of multiple Focus positions—in other words, by saying that Focus Phrase (like Topic Phrase) is iterable—or alternatively, in terms of adjunction (like what has been assumed to happen in English multiple questions in LF). (The latter option, however, would be in violation of Kayne’s LCA (Kayne 1994).)27

Without trying to resolve this question, let us note a certain order restriction on the stacking of Q-words in the Focus position: an adjunct must be closer to V than an argument.

This fact is strongly reminiscent of the well-known English requirement that an adjunct Q-word must move into COMP:

The English facts have been sought to be explained in terms of a COMP-indexing algorithm, in conjunction with ECP (Aoun et al. 1981, Huang 1982). The COMP-indexing algorithm is a stipulation that the first wh-phrase to move into COMP—in English, this means the wh-phrase which moves into COMP in the overt syntax—gives its index to COMP and is thereby enabled to c-command (and therefore antecedent-govern) its trace. The wh-phrases which adjoin to COMP in LF cannot antecedent-govern their traces. In (48b), in contrast to (48a), the trace of the adjunct why is not antecedent-governed; but neither is it lexically governed—therefore it violates ECP.

From the above account, what we need is the result that an adjunct Q-word must be the first to move into COMP. If English wh-movement is also to a Focus position albeit in the COMP system (Rizzi 1997), we may now generalize the English and Malayalam requirements: if Q-words are being moved into Focus, an adjunct Q-word is moved first. In English, the “doubly-filled COMP” filter allows no other Q-word to move in the overt syntax. But in Malayalam, observe that this gives us the order restriction that we noted. If we are thinking in terms of multiple FPs, the adjunct Q-word must move into the SPEC of the first Focus head which is merged with vP. If we are thinking in terms of a single FP and adjunction to its SPEC position, the adjunct Q-word must move into SPEC,FP and the other Q-words must left-adjoin to it.

Parallel facts have been noted in Japanese, cf. (49) (examples from Watanabe 1992):

As (49) shows, Q-words are “stacked” near the verb, and an adjunct Q-word must be closer to V than an argument Q-word. Saito (1989) attempts to assimilate this order restriction to Superiority effects, and tries to extend Pesetsky’s (1982) explanation of Superiority effects in terms of a Path Containment Condition (“If two paths overlap, one must contain the other”) to the Japanese facts. He reinterprets Pesetsky’s condition in linear terms. By moving Japanese Q-words to a clause-final COMP, he gets the following derivations for the naze–nani-o order and the nani-o—naze order:

Here, (50b) and (51b) violate Pesetsky’s condition and are ruled out. In (50a), naze ‘why’ will not be able to antecedent-govern its trace (given the COMP-indexing mechanism); therefore this derivation involves an ECP violation. Only (51a) is a possible derivation, and therefore the nani-o—naze order is the only permissible order.

Watanabe (1992) offers an alternative explanation of the order restriction by proposing the following condition for Japanese:

This condition (as its name suggests) is the opposite of the English condition; given two wh-phrases, one c-commanding the other, the lower wh-phrase must be moved first. In the order naze—nani-o, naze c-commands nani-o; therefore naze cannot move first, owing to Anti-superiority. But when it moves later, it cannot antecedent-govern its trace, and there is an ECP violation. In the order nani-o—naze (however), naze can (and must) move first; it can now antecedent-govern its trace, and a well-formed derivation results.28

Whereas Watanabe’s solution makes English and Japanese obey apparently opposite conditions, our analysis makes a cross-linguistic generalization possible: in both English and Malayalam (or Japanese), an adjunct question phrase moves into Focus first, ahead of other question phrases. We consider this to be strong supporting evidence for our postulated structures: in particular, an (underlying) V-initial VP even in SOV languages, and a projection of Focus above vP.

We shall now use the evidence of the cleft construction to show that English also makes use of a Focus position above VP.

We mentioned earlier that the natural way to ask a question in Malayalam is by clefting: a question word (or a larger phrase containing the question word) is placed in the “cleft focus”. (In the case of a multiple question, there will be a “stack” of question words in the “cleft focus”.)29

Let us assume that the constituent commonly called the “cleft focus” is a phrase moved into the SPEC of a Focus Phrase above the VP headed by the copula. Now consider English: the English copula obligatorily raises to I; and English being a non-prodrop language, an expletive is merged in the subject position. So we get a sentence like (53a), derived as shown in (53b):30

The Malayalam copula (like other verbs) does not raise to I. (We suggested that it adjoins to Focus, when Focus is present.) And Malayalam being a pro-drop language, the subject position can be filled by an expletive pro.31 So we get a sentence like (54a), derived as shown in (54b):

This analysis of English/Malayalam clefts explains why a phrase which superficially looks like a predicate complement of the copula acquires a meaning of focus. (A predicate complement is not a focus position, cf. John is tall/John is a doctor.)

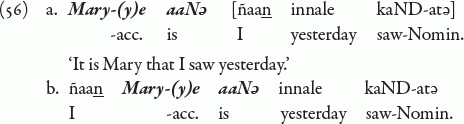

What is commonly called the “cleft clause” can appear on the left of the focused phrase in Malayalam:

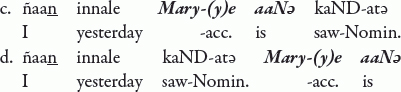

What is intriguing however is that elements of the cleft clause can appear on both sides of the cleft focus and the copula: i.e., superficially, the focus-plus-copula (like a constituent) seems to “float” into the cleft clause:

Note that in (b) and (c), the focus-plus-copula is “inside” the cleft clause.

In fact, if we ignore the nominalizing morphology, the copula seems to be functioning merely as a focus marker that may be freely attached (inside a clause) to a focused phrase.32 Thus, in the neutral sentence underlying (56), either of the arguments, or the adverbial modifier, of kaNDu ‘saw’ can have the copula “attached” to it and so be focused:

How should we understand this free-moving “focus-marker” copula?

Analyzing the shi-de cleft construction in northern dialects of Mandarin Chinese, Simpson & Wu (1999) show that the nominalizer de—originally derived from a demonstrative and therefore belonging to the category of Determiner—has been reanalyzed from Do to To (i.e. Tense); and that (as a result), the shi-de clause, which ought to behave like a Complex Noun Phrase (CNP) and be opaque to extraction and certain types of interpretation, has become transparent to such processes. Now the Malayalam nominalizer -atə also incorporates a demonstrative: it is historically derived from aa ‘that’ + -tə ‘3rd person singular (agreement)’ (Anandan 1985). Let us say that a similar process as Simpson and Wu postulate for Chinese has taken place in Malayalam; so that the clause ending with -atə is no longer a CNP but simply a tensed clause which is fully transparent to extraction.33

Given this, we can account for the puzzle of the “floating” of the focus-plus-copula. The elements which flank the cleft focus on the left are elements which have been moved (from the cleft clause) into SPECs of Topic Phrases above the Focus Phrase. Thus (56b) (repeated below) has the structure (58).

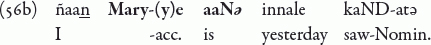

If elements to the left of the cleft focus are indeed Topicalized, they ought to show the familiar definiteness/specificity effect. This prediction is borne out, cf.

Again, since generics are topicalizable like definites and specifics, the following sentence is predicted to be fine:

Clefts are not the only construction in which we have evidence of English making use of the IP-internal Focus position.

Consider the process variously called “incomplete VP deletion” (Jayaseelan 1990), “VP subdeletion” (Kayne 1994) and “pseudogapping” (Lasnik 1995, 1999)—we shall henceforth adopt the last name. In pseudogapping, what looks like a case of VP Deletion leaves behind a “remnant” (underlined in (62)). (Examples from Sag (1976).)

The remnant is sometimes in the “middle” of the deleted VP, as in Speaker B’s response in (62b):

In Jayaseelan (1990) I analyzed pseudogapping as two operations—the remnant (which is a constituent that invariably receives contrastive stress) undergoes Heavy NP Shift, formulated (standardly) as right-adjunction to VP; the “inner” VP then undergoes deletion:

Lasnik (1995, 1999) suggests a modification of this analysis, namely that the movement of the remnant is to SPEC,AGRoP, which involves a leftward movement.36 I now think (along with Lasnik) that the remnant’s movement out of the VP should be formulated as a leftward movement. But the proposed landing site is problematic. As was just mentioned, the remnant invariably bears contrastive stress; if the discourse context makes it impossible to give it contrastive stress, pseudogapping yields an ungrammatical sentence:

In Jayaseelan (1990), I called this requirement of stress on the remnant, a Focus Constraint on it. Now it is difficult to imagine why a direct object moving into SPEC, AGRoP—a process which both Koizumi and Lasnik hold is something that normally takes place in the overt syntax in English—should be subject to a Focus Constraint, just in the pseudogapping cases.37

A second problem is that the remnant is not always a direct object, nor even a DP. In the following examples, the remnant is a PP:

Lasnik’s suggestion regarding this is that PP also—in fact, any complement generally—raises to SPEC of AGR, because AGR contains an EPP feature. If I understand this argument correctly, the claim is that an EPP feature can be satisfied by a phrase of any category. It is difficult to evaluate this suggestion, but let us point out that this indifference to the category of the phrase raised to its SPEC is strongly reminiscent of Topic or Focus, and is unlike AGR (as originally conceived).

Chomsky (1995,1998) has suggested that it is theoretically undesirable to allow [-interpretable] features to head phrases; and as a consequence, he has proposed doing away with AGRPs. If we go along with this theoretical move, we must anyway look for another host for the remnant of pseudogapping.

Now, if we say that the remnant moves into the SPEC of the Focus Phrase immediately above vP, we do not face any of the problems of Lasnik’s analysis. We also have a natural explanation of the Focus Constraint on the remnant.

As we said, Heavy NP Shift—also called “Focus NP Shift” (Rochemont 1978)—used to be standardly analyzed as “extraposition,” the extraposed NP being right-adjoined to VP. However, Den Dikken (1995) is cited in Kayne (1998) as proposing a reanalysis wherein the “heavy NP” is moved leftward to the SPEC of AGRoP, followed by VP-preposing. Kayne (1998) adopts the Den Dikken proposal in its essentials, but is more unspecific about the landing site of the “heavy NP”: he moves it to the SPEC of a functional head which he simply calls H. In VP-preposing, he moves the VP to the SPEC of a higher functional head which he calls W. (H raises and adjoins to W.) Thus (66) will be derived via the steps shown in (67):

Den Dikken’s original proposal to move the “heavy NP” to SPEC of AGRo has all the drawbacks of Lasnik’s analysis of pseudogapping, especially if the notion of ‘heaviness’ (that applies to the “heavy NP”) can be assimilated to focus (see Rochemont & Culicover (1990), also Kayne (1998: fn. 93)). We can make Kayne’s proposal more specific if we say that his H0 and W0 are (respectively) Focus and Topic; i.e. the “heavy NP” moves to the SPEC of Focus Phrase, and VP moves to the SPEC of a (higher) Topic Phrase.

If our analysis above is correct, we now have evidence of English making use of not only the IP-internal Focus Phrase, but also the IP-internal Topic Phrase(s), that the Grammar allows the language to generate.

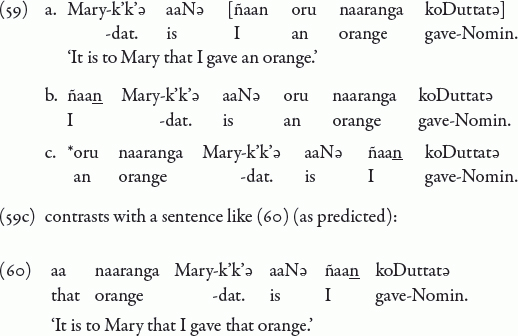

More evidence for both these positions comes from “floated” focus markers. In Jayaseelan (1997), I noted that when the English focus marker himself (herself, themselves, etc.) floats rightward from the DP it focuses, it may occur in all the positions which Baltin (1982) noted as the landing sites of floated quantifiers; but in addition, it may occur in the sentence-final position (the right-peripheral position of VP) where a floated quantifier cannot occur.

I also noted that, as was known to be the case for quantifiers, the focus marker also may float only from a subject DP:

I proposed (ibid.) the extension of Sportiche’s (1988) analysis of floated quantifiers to floated focus markers. Sportiche’s suggestion is that the subject, generated VP-internally (Fukui & Speas 1986), raises to SPEC,IP via the SPEC positions of all the intervening VPs; and that a quantifier in the subject DP may be ‘stranded’ in any of these intermediate SPEC positions. This explains why the left peripheries of VPs are the landing sites of these floated elements. Since only subjects move up (overtly) in English, it also explains why floating is possible only from the subject DP.

But a problem remained, just for focus markers. Sportiche’s analysis, extended to them, did not account for one of their landing sites, namely the clause-final position:

This was left unsolved.

But if there is a Focus Phrase above vP, we now have a solution. We can say that a subject DP with a focus marker may first move into SPEC,FP, and may optionally ‘strand’ the focus marker in that position when it raises further; now, VP-preposing gives us the desired word order:

(A direct or indirect object bearing a focus marker may also raise to SPEC,FP. But an object would raise no further in English in the overt syntax, so it will not ‘strand’ a focus marker. Subsequent VP-preposing will either make the first movement ‘invisible’, or yield the same result as Heavy NP Shift.)38

Chomsky (1998) proposes the notion of a ‘phase’, which plays a crucial role in his new account of cyclicity: CP and vP are phases; and a ‘phase impenetrability’ condition requires that any extraction must first move an element to the “edge” of the phase, i.e. the SPEC of the head of the phase. In other words, CP and vP have SPECs which are “escape hatches” through which extracted elements must pass. Since SPEC,vP is the position in which the external argument (the subject) is merged, Chomsky gives vP an “extra” SPEC position which can function as the “escape hatch”:

Here EA (external argument) is the position occupied by the subject, and XP is the “extra” SPEC position. Chomsky further suggests that this outer SPEC position is also the target of object shift in Scandinavian.

One may point out that, given a more finely articulated COMP system like that of Rizzi (1997), one can no longer say that SPEC,CP is an “escape hatch”. One must say which phrase among the many phrases that constitute the COMP system functions as the “escape hatch”. Rizzi suggests that English wh-movement moves a wh-phrase into the SPEC of the Focus Phrase in the COMP system. Now, if we can say that the “escape hatch” in the left periphery of the vP phase is also the SPEC of a Focus Phrase, we have a generalization: cyclic wh-movement is seen to be focus-to-focus movement.

Object shift in Scandinavian shows the same definiteness/specificity effects as scrambling in German and Dutch (Diesing 1997, Holmberg p.c.). Using the adverb position as a diagnostic of object shift, it is observed that an indefinite NP to the left of the adverb has a specific reading forced on it. An unstressed definite pronoun must shift, like in German (see (34)); and although, for a ‘full’ definite DP, object shift is apparently optional, an unshifted definite DP has a “contrastive interpretation” (Diesing 1997: 418). This (for us) suggests that it is in the Focus Phrase. A shifted definite or indefinite object, on the other hand, is (we can say) in a Topic Phrase. Needless to say, analyzing object shift as a movement to an ‘outer’ SPEC position of vP does not explain any of the observed semantic effects.39

The ‘outer’ SPEC position of vP (then) is not needed to account for either cyclic wh-movement or object shift. We can eliminate multiple SPECs, with a consequent simplification of the theory, if other uses of them (like in “multiple subject constructions”, see Chomsky (1995:356)) can also be dispensed with by reanalysis.

Chomsky (1998) adopts the device of assigning an EPP feature to C and v; the aim being to give C and v also (like T) a SPEC position which is not mandated by theta-theory. (In the case of v, this is the ‘outer’ SPEC position.) This assignment is stipulated to be optional, which means that C/v will get this SPEC position only “when needed” (e.g. for wh-movement, or in the case of v, additionally for object shift). It is further stipulated that, unlike T (which presumably has the EPP feature when it enters the numeration), C/v is assigned this feature at the end of the phase, after the lexical subarray from which it is derived has been exhausted. This ensures that the SPEC position is not filled by “pure” Merge—specifically, the merge of EXPL40—but must be filled by Movement.

Now observe how our alternative analysis obtains these results. For us, the SPEC position into which a wh-phrase or a shifted object moves is generated only “when needed”, because a Focus/Topic Phrase is always generated optionally. Also, an EXPL cannot be introduced by “pure” Merge in SPEC,FP (or be raised to SPEC,FP), because an expletive cannot bear focus. (An argument, which can bear focus, cannot be introduced here by “pure” Merge, because this is not a theta position.)

Rizzi’s “more finely articulated” COMP system has a Topic-Focus configuration bounded at the upper end by a Force Phrase and at the lower end by a Finiteness Phrase (see fn. 7). If we leave aside the Force Phrase and the Finiteness Phrase, it would appear (at first glance) that the Topic-Focus configuration is replicated above vP. But there are differences. In the case of the configuration above vP, there is an adverb position between the Topic positions and the Focus position. (This is the adverb position which is used as a diagnostic of scrambling in some European languages.)41 In SOV languages (moreover), the so-called canonical positions of the verb’s arguments seem to come immediately above the Focus Phrase, in fact intervening between the Focus Phrase and the Topic Phrases (and the above-mentioned adverb position) (see the figure in (38)). As a consequence, in these languages, a topicalized phrase comes to the left of its canonical position, and a focused phrase comes to the right of its canonical position, in linear terms.

Certainly many questions arise regarding this structure (assuming it to be correct). (E.g. why are the canonical positions in that particular configuration with respect to Topic and Focus? There is also the prior question: what motivates the “migration” of arguments out of VP in SOV languages?) But it seems reasonable to claim that the clause-structure proposed here for SVO and SOV languages provides a new way of looking at clause-internal scrambling and object shift in a wide variety of languages.

* This paper was presented at the 2nd Asian GLOW Colloquium held at Nanzan University (Japan), September 1999. A shortened version of this under the title “A Focus Phrase above vP” appeared in the conference proceedings. I wish to thank the audience of the GLOW Colloquium, and also R. Amritavalli, M. T. Hany Babu, Jeffrey Lidz and two anonymous reviewers of this journal, for comments.

1. This is a fairly well-studied phenomenon. Perhaps the language in which it has been the subject of the most extensive discussion to date is Hungarian; see (among others) Horvath (1986), Kiss (1987), Farkas (1986), Kenesei (1986), Brody (1990). But the phenomenon has also been studied in Basque (Laka & Uriagereka 1987) and in several African languages, e.g. Aghem (Watters 1979), Chadic (Tuller 1992), and (most recently) Kirundi (Ndayiragije 1999).

2. Other Dravidian languages—and indeed many other languages of the Indian subcontinent—also tend to place their question words to the immediate left of V. But in their cases, this positioning is apparently not a strict requirement (like it is, in Malayalam). (The parametric difference can perhaps be stated in terms of strong/weak features: Malayalam question words have a strong focus feature (see our analysis below), whereas the question words of the other languages have a focus feature which is optionally strong.)

3. Some other details: The subject of (1a) has its case checked in SPEC,FP by a “probe” from I. (For the notion of “probe”, see Chomsky (1998). There will be no “intervention effect” induced by the direct object, if we adopt a suggestion of Chomsky (1999) that only the whole of an A-chain creates an intervention effect. In (1a), only the head of the chain of DO intervenes between I and the subject in SPEC,FP.) I’s EPP feature is possibly satisfied by a pleonastic pro merged in the subject position (Malayalam being a pro-drop language (of the Chinese type)); or possibly, the EPP feature is assigned only optionally to I in Malayalam (which would be a matter of parametric difference).

4. A Focus Phrase above VP, and essentially the analysis outlined above, was proposed in Jayaseelan (1996). Recently, Ndayiragije (1999) has postulated a Focus Phrase above VP to explain two marked word orders in Kirundi in which the subject follows the verb and the object—the unmarked order in Kirundi is SVO—and acquires a contrastive focus reading. The following is Ndayiragije’s proposed structure:

Note that the Focus Phrase—and only the Focus Phrase—has its SPEC position to the right of the head. We feel that this asymmetry can be avoided, and the marked word orders in Kirundi still accounted for, if a VP-preposing operation—such as has been attested in many SVO languages (Kayne 1998)—applies after the subject’s movement to SPEC,FP:

For our purposes (then), we shall continue to adopt a canonical configuration for Focus Phrase (as in (8)).

A reviewer of this journal wonders if a question word’s movement into a Focus Phrase would fix its scope for good, making it impossible to describe cases of a question word in an embedded clause taking matrix scope. A fully adequate answer to this query must await another paper, but we may note that different languages may have different scope-marking strategies for their questions. In Malayalam, when a question word in an embedded clause has matrix scope, the question word first moves into the FP of the embedded clause, and then the whole embedded clause moves into the FP of the matrix clause. Alternatively, a cleft construction is used, in which the embedded clause is the cleft focus. The two strategies are illustrated below:

(The first strategy has recently been described for Bangla, in Simpson & Bhattacharya (1999).)

5. For the DO-IO order in SVO languages, we follow Larson (1988), who takes the IO-DO order of the “double object construction” to be a derived structure.

Although nothing depends (for the claims of this paper) on the above-mentioned movements being “nested” movements, we may keep in mind the following: The mirror-image correspondence of the VPs of SVO and SOV languages needs to be accounted for. This can conceivably be explained—while retaining a traditional ‘SPEC-Complement-Head’ order for SOV languages—by “reversing” for SOV languages Larson’s Thematic Hierarchy (i), or his principle for mapping the Thematic Hierarchy into constituent structure (ii) (see Larson (1988, 382)):

But remember that we also need to account for our original problem, namely the Focus position which is apparently to the immediate left of V. In order to do this, we still need to move the arguments out of the VP “past” a Focus Phrase—like in our present proposal. (Therefore, we do not “save the VP-vacating movements” by postulating an underlying ‘SPEC-Complement-Head’ order for SOV languages.)

Now—given the need for these movements -, if we have adopted the “reversed” Thematic Hierarchy/mapping rule, we need to stipulate that these movements must be consistently “crossing” movements in order to preserve the canonical order, cf.

If (on the other hand) we have taken the simpler option of applying Larson’s Thematic Hierarchy and mapping rule to SOV languages (the same as to SVO languages), we need “nested” movements, cf.

Between stipulating “crossing” or “nested” movements, we must choose the latter, since “nested” movements are computationally simpler.

6. Relativized Minimality (Rizzi 1990) stipulates that an A-movement cannot “skip” an intervening A-position; similarly an A-bar movement cannot “skip” an intervening A-bar position.

Chomsky’s (1992) reformulation of minimality—which tries to account for certain observations of Holmberg (1986) about Scandinavian object shift—allows A-movement to skip one intervening A-position if it lands in the SPEC of a head to which V has raised.

Neither formulation is helpful for the Malayalam movements we postulated, since these move elements to SPECs of heads higher than F, to which the verb does not raise. (In fact, even the Malayalam subject’s normal movement to SPEC,IP should be stopped by SPEC,FP since there is no V-to-I raising.)

7. Rizzi’s articulation of the COMP system has iterable Topic Phrases both above and below FP:

8. In this paper, I do not answer the question of the nature of the heads which host the elements moved by these “nested” movements. The answer is obviously related to the question of what motivates these movements. While richness of morphological Case shows some corelation with SOV word order, the movements cannot be attributed to Case-checking for various reasons that I will not go into here.

9. Note that we are not suggesting a “downward” movement of the IO from its canonical position into a TopP below it, which would be theoretically indefensible. The idea is that elements which are marked for Topic/Focus features move into Topic/Focus Phrases, while the unmarked elements undergo “nested” movements. (But all the movements are “upward” movements from within vP.)

10. A sentence like (i) is okay, with stress on ORU ‘one’:

Here ORU naaranga ‘one orange’ is specific: it is interpreted as ‘one orange, from among a previously-mentioned set of oranges’. It is therefore topicalizable. Cf. the following English data (noted in Mahapatra (in preparation)):

(iia) is ungrammatical unless ‘a boy’ is interpreted as generic. (An indefinite, nonspecific NP cannot be the subject of the copula. I.e. the conditions on topicalization apply to this position.) But (iib) is fine, because ‘one boy’ is specific: its reading is ‘one boy, from among the set of boys under discussion’.

A variant of (i) with stress on Mohanan-ə ‘Mohanan-dat.’ is also fine:

Here, ‘Mohanan’ is interpreted as contrastively focused, and is (we must conclude) in FP.

11. One may note that in a variant of (23b) in which IO is definite and contrastively stressed, the indefinite reading of weLLam can resurface:

Here, IO is in Focus (we may conclude), and weLLam is not topicalized.

12. Jeffrey Lidz (p.c.) points out that, if there are multiple TopPs above the canonical positions, a sentence like (i):

ought to be ambiguous, with weLLam ‘water’ being interpreted as either definite or indefinite; since both IO and DO could have been topicalized. But in fact, it is difficult to get a definite reading for weLLam. This would argue that there is only one TopP above the canonical positions, in (15).

But we shall see evidence from some European languages for multiple TopPs in this position (cf. (43), below). Even in Malayalam, if definite pronouns have a strong tendency to be topicalized (cf. (22)), the following sentences would seem to argue for multiple TopPs above the canonical positions:

We shall leave open the question of multiple TopPs above the canonical positions (in Malayalam).

13. Note however that an indefinite noun phrase is not always interdicted from appearing in the post-verbal Topic position—or for that matter, in the pre-subject Topic position.

Here, “getting a letter” has been the subject of conversation, and therefore ‘a letter’ is part of the ‘given information’ (i.e. Topic).

14. Or the presence of neg in the IP. Thus (i) seems not as acceptable as (29b) (unless one were to stress ñaan ‘I’ or the verb):

Again, (ii) is much better than (iii):

(Observe that the Topic position is iterable, as illustrated by (ii).)

We may point out that adverbial elements occur post-verbally quite freely, without the need of any FP or neg in the clause:

A different process may be at work here. Alternatively, an adverbial in a pre-subject Topic position can perhaps induce IP-preposing.

15. Some details: it is the highest V that is inflected for Tense. In linear terms, this will be the last V in the verb sequence. The other Vs are in participial or ‘bare’ form; so it is always a VP with a non-finite V which is moved.

16. In Jayaseelan (1998) I suggested that in Malayalam questions, the head of Force Phrase is occupied by the disjunction marker -oo; and that when this -oo is present, IP obligatorily raises to the SPEC of ForceP. So the linear order we get is IP-oo-ennə, cf.

we must then assume that Mary-(y)e has been raised to a Topic position higher than IP, prior to the raising of IP to the SPEC of ForceP.

Correspondingly, in the case of a sentence like:

Mary-(y)e must be in a TopP which is “within” IP, although it is still higher than the position of the subject—possibly providing evidence for our claim that the Malayalam subject can be simply in a TopP and does not necessarily occupy SPEC,IP. But such a Topic position—“within” IP but above the subject—is needed even in other languages where the subject is claimed to be in SPEC,IP; cf. the following Dutch sentence (Zwart 1996:29):

or the English sentence:

17. What is called the “middle field” in the German or Dutch sentence is the space occupied by the elements that undergo (clause-internal) scrambling. In an embedded clause, this would be the space between the (clause-initial) complementizer and the (clause-final) finite V. See Abraham (1986) (who draws on Lenerz (1977)) for a more explicit definition.

18. We shall look at evidence for this Focus Phrase in German, presently.

19. See Zwart (1996: Chapter III), for details. Zwart writes (p.100):

The word order in the Mittelfeld in Dutch is the result of a complex interaction of prosodic phrasing and the placement of different types of adverbs.

20. Our topicalizing idea is similar to an older idea—attributed by Zwart (1996:93) to Von Stechow and Sternefeld (1988:464f.) and Reinhart (1995)—that object movement in Continental West Germanic is a ‘defocusing’ movement.

21. The licensing of parasitic gaps brings up the question of the A/A-bar properties of scrambled phrases. This difficult question—see Webelhuth (1992), Sengupta (1990), Mahajan (1990), Kidwai (1995) for a debate of this question—is completely sidestepped in this paper.

22. Diesing (1997) argues (convincingly, to my mind) that Yiddish is an SVO language.

23. We have ‘conflated’ the Adverb and Neg positions in (38) and (39). See fn. 39 for a more ‘fine-grained’ account.

24. A small difference is that (15) shows no AdvP/NegP. Neg in Malayalam is a finite auxiliary verb which is clause-final; one must suppose that it heads an auxiliary VP immediately under TP (Tense Phrase). Regarding adverbs, Hany Babu (p.c.) has pointed out to me that Malayalam adverbs seem to behave pretty much like the German adverbs. Cf.

In (ia), both ‘a beggar’ and ‘a rupee’ have (most naturally) a non-specific reading. But (ib) means that I give a particular beggar a rupee every day; and (ic) has the odd reading that I give a particular rupee coin (or note) repeatedly to a beggar every day. Thus, we could very well have indicated an AdvP in (15), in the same position relative to TopP* and the canonical positions as in German.

25. Also see the discussion in Diesing (1997:378,379,391).

26. Further (and very interesting) confirmation is provided by Modern Persian, an SOV language, in which specific and non-specific DOs occupy different positions in the surface syntax (Karimi 1999; all examples below are from this source). A specific (definite or indefinite) DO precedes IO, and is invariably followed by a special marker râ; a non-specific DO follows IO:

A specific DO can license a parasitic gap, a non-specific DO cannot:

We can readily fit these facts into our analysis if we say that râ is a Topic marker generated as the head of a Topic Phrase; and that a specific DO (in Modern Persian) is obligatorily topicalized. (Karimi (1999) posits different phrase structure rules to base-generate specific and non-specific DOs in different positions. This move—which violates a very widely-accepted ‘Uniformity of Theta Assignment Hypothesis’ (Baker 1988)—can be dispensed with, given our analysis.)

27. In Hungarian also, question words—and only question words—are stacked in a Focus Phrase above VP; but not all question words need be so stacked (Brody 1990:204). It is unclear why multiple Focus positions—or alternatively, the option of adjunction—should be available only for question words.

We said that German and Yiddish admit only one Focus position above vP (at least in overt syntax). There may be a parametric difference between German/Yiddish type languages and Malayalam/Hungarian type languages.

28. Given three question phrases, in the following c-command relation:

Watanabe’s condition allows either B or C to move first, since either will have another question phrase which it does not c-command. In support of this prediction, he cites the following sentence (=Watanabe’s (33b)):

The parallel Malayalam sentence (ii), we find not much better than (46b) (repeated as (iii)):

29. See Madhavan (1987), Srikumar (1992) for earlier studies of Malayalam clefts.

30. Normally, the movement of a focused phrase to SPEC,FP is a clause-internal process. In (53b), is the “cleft focus” Mary moved directly from the embedded CP? If so, this would be exceptional. However we shall presently see more things that are exceptional about clefts.

31. Another possibility is that the EPP feature is only optionally assigned to Malayalam INFL. See fn. 3.

32. This was (more or less) the analysis suggested for the cleft copula in Chinese, in Huang 1982. Shi ‘be’ was analyzed as a focusing adverb that marked a focused constituent, only in clefts.

33. In the Malayalam pseudo-cleft construction, the cleft clause has not undergone a similar process; and therefore the “floating” of the focused phrase and the copula into the cleft clause is not allowed:

See Madhavan (1987) for a discussion of this fact.

34. Movement to the SPEC of IP-internal Topic Phrases normally takes place only within the clause. What takes place in the cleft construction (assuming our analysis to be correct) is therefore exceptional. (See also fn. 30.) The Simpson-Wu account of Chinese, extended to Malayalam, perhaps only explains why the cleft clause does not behave like a Complex NP; it does not explain why it does not behave like a tensed clause at all. We (therefore) still do not have a “complete” explanation.

35. An interesting theoretical point arises in connection with our analysis of clefts. Suppose we wished to claim that every ‘phase’ (in the sense of Chomsky 1998) has a “COMP system” on its left periphery. This is certainly true of CP (which is a ‘phase’): IP is dominated by a COMP system. We have shown that vP is also dominated by a COMP system which shows some parallelism with the COMP system above IP. If our claim is to go through (however), it now looks as if we must consider a VP headed by a copula also as a ‘phase’.

36. Lasnik adopts Koizumi’s “split VP” structure, in which a higher and a lower VP have an AGRP positioned between them. The remnant is moved to the SPEC of this AGRP, and the lower VP is then deleted:

Koizumi’s position is that the direct object in English raises overtly to SPEC,AGRoP; and that the main verb also raises overtly to the (higher) “shell” V position. In the deletion case (however), the main verb (in (i), seen) apparently has not raised (otherwise it will not be included in the deleted string). Lasnik accounts for this by suggesting that the strong feature which drives the verb’s movement to the “shell” V position is not lodged in the target position but in the verb itself; therefore, given a “PF crash” theory of strong features, the deletion of the string that includes the verb in the PF component saves the derivation from crashing.

37. It is unclear how such a condition can even be stated, unless one were to argue that only stressed direct objects move overtly to SPEC, AGRoP. But this is a very implausible thing to say.

38. An anonymous reviewer of this journal raises the question: Will the subject’s movement from SPEC,FP to SPEC,IP be a case of A’-to-A movement (an illicit type of movement)? The answer obviously will depend on what we consider SPEC,FP to be, A or A-bar. It is now known (however) that scrambled phrases exhibit some A, and some A-bar, properties (Webelhuth 1992); and under our analysis, scrambled phrases are simply phrases moved to SPEC,TopP and SPEC,FP. SPEC,FP (then) could very well be exhibiting an A property in this case. But as we stated earlier (fn. 21), we shall not examine issues pertaining to the A/A-bar distinction in this paper. (‘Subextraction’ from the postulated position is generally admissible, cf. the ‘subextraction’ from a Heavy-NP-Shifted phrase in (i):

39. The puzzle still remains, of the apparent dependence of Scandinavian object shift on verb movement. A possible solution is that what is now taken to be V-raising licensing object shift, is actually obligatory remnant-VP-preposing after object shift, very much like what seems to be happening in the case of Heavy NP Shift in English (see (66)). (V-raising by itself is also independently possible.) Observe that such an analysis involves no counter-cyclic operation and also is a very natural explanation of the “phonological edge” condition on object shift of Chomsky (1999), Holmberg (1999).

What we represented as a single Adv/Neg position in (38)/(39) possibly needs to be “split”, with Neg higher than Adv (and with Topic(s) intervening). Such a move seems warranted by the following facts: if there is an auxiliary verb in the sentence, this does not seem to affect VP-preposing to a position above the adverb; but (for unclear reasons) it seems to prevent VP-preposing above Neg (all examples below from Collins & Thrainsson (1996)):

Again, the ‘above-Adv’ position seems to tolerate a ‘heavy’ VP containing two objects much more comfortably than the ‘above-Neg’ position ((iii) is a Danish example from Vikner (1991) cited by Collins & Thrainsson (1996)):

At least some cases of so-called “inversion” involving the double object construction, in which the normal IO-DO order is reversed, cf. (v), are cases of the indirect object being moved to Focus, and subsequent VP-preposing:

(Inversion analyzed as base-generated dative alternation—Collins & Thrainsson (1996) and references cited there—leaves unexplained the requirement of stress on the indirect object here.)

Incidentally, a preposing VP can apparently carry along an indefinite NP:

While many puzzles remain, the approach outlined here seems promising and deserves to be pursued.

40. Arguments cannot be merged in this position because it is not a theta position.

41. Cinque (in press) has argued for a universal hierarchy of adverb positions, distinguished into a lower and a higher set. The fact (pointed out by Cinque) that the Italian subject can occur “in between” the higher adverbs, suggests that the Topic positions may be “interleaved” with the higher adverb positions. But this claim requires further investigation.

Abraham, W. 1986. Word order in the middle field of the German sentence. Topic, Focus and Configurationality (Papers from the 6th Groningen Grammar Talks, Groningen, 1984), ed. W. Abraham & S. de Meij, 15–38. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Anandan, K. N. 1985. Predicate nominals in English and Malayalam. M.Litt. diss., Central Institute of English and Foreign Languages, Hyderabad.

Aoun, J., Hornstein, N. & Sportiche, D. 1981. Some aspects of wide scope quantification. Journal of Linguistic Research 1, 69–95.

Baker, M. 1988. Incorporation. Chicago: Chicago U. Press.

Baltin, M. 1982. A landing site theory of movement rules. Linguistic Inquiry 13, 1–38.

Brody, M. 1990. Some remarks on the focus field in Hungarian. UCL Working Papers in Linguistics, 201–225. Department of Linguistics, University College London.

Chomsky, N. 1992. A minimalist program for linguistic theory. MIT Occasional Papers in Linguistics 1. (Also in Chomsky 1995.)

Chomsky, N. 1995. The minimalist program. Cambridge MA: MIT Press.

Chomsky, N. 1998. Minimalist inquiries. Ms. MIT.

Chomsky, N. 1999. Derivation by phase. Ms. MIT.

Cinque, G. In press. Adverbs and functional heads: a cross-linguistic perspective. Oxford and New York: Oxford U. Press.

Collins, C. & Thrainsson, H. 1996. VP-internal structure and object shift in Icelandic. Linguistic Inquiry 27, 391–444.

De Hoop, H. 1992. Case configuration and noun phrase interpretation. Ph.D. diss., University of Groningen.

Den Dikken, M. 1995. Extraposition as intraposition, and the syntax of English tag questions. Ms.Vrije Univeriteit Amsterdam/HIL.

Diesing, M. 1992. Indefinites. Cambridge MA: MIT Press.

Diesing, M. 1997. Yiddish VP order and the typology of object movement in Germanic. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 15, 369–427.

Farkas, D. 1986. On the syntactic position of Focus in Hungarian. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 4, 77–96.

Fukui, N. & Speas, M. 1986. Specifiers and projections. MIT Working Papers in Linguistics 6, 128–172.

Holmberg, A. 1986. Word order and syntactic features in the Scandinavian languages and English. Ph.D. diss., U. of Stockholm.

Holmberg, A. 1999. Remarks on Holmberg’s generalization. Studia Linguistica 53, 1–39.

Horvath, J. 1986. FOCUS in the theory of grammar and the syntax of Hungarian. Dordrecht: Foris.

Huang, C.-T. J. 1982. Logical relations in Chinese and the theory of grammar. Ph.D. diss., MIT.

Jayaseelan, K. A. 1990. Incomplete VP deletion and gapping. Linguistic Analysis 20, 64–81.

Jayaseelan, K. A. 1996. Question-word movement to Focus and scrambling in Malayalam. Linguistic Analysis 26, 63–83.

Jayaseelan, K. A. 1997. Anaphors as pronouns. Studia Linguistica 51, 186–234.

Jayaseelan, K. A. 1998. Questions, quantifiers and polarity in Malayalam. Paper presented at the 1st Asian GLOW Colloquium, Central Institute of English and Foreign Languages, Hyderabad.

Karimi, S. 1999. A note on parasitic gaps and specificity. Linguistic Inquiry 30, 704–713.

Kayne, R. 1994. The antisymmetry of syntax. Cambridge MA: MIT Press.

Kayne, R. 1998. Overt vs. covert movement. Ms. NYU.

Kenesei, I. 1986. On the logic of word order in Hungarian. Topic, Focus and Configurationality (Papers from the 6th Groningen Grammar Talks, Groningen, 1984), ed. W. Abraham & S. de Meij, 143–149. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Kidwai, A. 1995. Binding and free word order phenomena in Hindi and Urdu. Ph.D. diss., Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi.

Kiss, K. E. 1987. Configurationality in Hungarian. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Koizumi, M. 1994. Object agreement phrases and the split VP hypothesis. MIT Working Papers in Linguistics 18: Papers on Case and Agreement I, 99–148. Department of Linguistics and Philosophy, MIT.

Laka, I. & Uriagereka, J. 1987. Barriers for Basque and vice-versa. NELS 17, 394–408, Department of Linguistics, University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Lasnik, H. 1995. A note on pseudogapping. Papers on Minimalist Syntax (MIT Working Papers in Linguistics 27), ed. R. Pensalfini & H. Ura, 143–163. Department of Linguistics and Philosophy, MIT.

Lasnik, H. 1999. On feature strength: three minimalist approaches to overt movement. Linguistic Inquiry 30, 197–217.

Lenerz, J. 1977. Zur Abfolge nominaler Satzglieder im Deutschen. (Studien zur deutschen Grammatik 5). Tubingen: Narr.

Madhavan, P. 1987. Clefts and pseudoclefts in English and Malayalam—a study in comparative syntax. Ph.D. diss., Central Institute of English and Foreign Languages, Hyderabad.

Mahajan, A. 1990. The A/A-bar distinction and movement theory. Ph.D. diss., MIT.

Mahapatra, B. (in preparation) Untitled Ph.D. diss., Central Institute of English and Foreign Languages, Hyderabad.

Ndayiragije, J. 1999. Checking economy. Linguistic Inquiry 30, 399–444.

Pesetsky, D. 1982. Paths and categories. Ph.D. diss., MIT.

Reinhart, T. 1995. Interface strategies. OTS Working Papers, U. of Utrecht.

Rizzi, L. 1990. Relativized minimality. Cambridge MA: MIT Press.

Rizzi, L. 1997. The fine structure of the left periphery. Elements of grammar. Handbook of generative syntax, ed. L. Haegeman. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Rochemont, M. S. 1978. A theory of stylistic rules in English. Ph.D. diss.,U. of Massachusetts.

Rochemont, M. S. & Culicover, P. W. 1990. English focus constructions and the theory of grammar. Cambridge: Cambridge U. Press.

Sag, I. 1976. Deletion and logical form. Ph.D. diss., MIT.

Saito, M. 1989. Crossing and WH-Q binding. Talk given at the Ohio State University.

Sengupta, G. 1990. Binding and scrambling in Bangla. Ph.D. diss., U. of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Simpson, A. & Bhattacharya, T. 1999. Obligatory overt wh-movement in a wh in situ language. Ms. School of Oriental and African Studies & University College London.

Simpson, A. & Wu, X-Z. Z. 1999. From D to T—determiner incorporation and the creation of tense. Ms., School of Oriental and African Studies & U. of Southern California.

Sportiche, D. 1988. A theory of floating quantifiers and its corollaries for constituent structure. Linguistic Inquiry 19, 425–449.

Srikumar, K. 1992. Question-word movement in Malayalam and GB theory. Ph.D. diss., Osmania University, Hyderabad.

Von Stechow, A. & Sternefeld, W. 1988. Baustein syntaktischen Wissens. Ein Lehrbuch der generativen Grammatik. Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag.

Tirumalesh, K. V. 1996. Topic and focus in Kannada: implications for word order. South Asian Language Review 6, 25–48.

Tuller, L. 1992. The syntax of postverbal focus constructions in Chadic. NNLT 10, 303–334.

Vikner, S. 1991. Verb movement and the licensing of NP-positions in the Germanic languages. Ph.D. diss., U. of Geneva.

Watanabe, A. 1992. Subjacency and S-structure movement of wh-in-situ. Journal of East Asian Linguistics, 1, 1–37.

Watters, J. 1979. Focus in Aghem. Aghem grammatical structure, ed. L. Hyman. SCOPIL-7, U. of Southern California.

Webelhuth, G. 1992. Principles and parmeters of syntactic saturation. New York: Oxford U. Press.

Zwart, C. J. W. 1993. Dutch syntax: A minimalist approach. Ph.D. diss., U. of Groningen.

Zwart, C. J. W. 1996. Morphosyntax of verb movement. A minimalist approach to the syntax of Dutch. Dordrecht: Kluwer.