K. A. Jayaseelan

THE MAIN THEORETICAL claim of this paper will be that the device of “Attract” by an EPP feature as a means of implementing movement—in fact as the sole means of implementing phrasal movement (Chomsky 1998, 1999)—proves to be inadequate when we try to account for the behavior of wh-phrases in certain languages. I shall suggest a solution in terms of the notion of an operator’s ‘probe’, and a parameterized property of this probe.

In the main body of this paper I shall present the facts regarding question movement in Malayalam, incidentally comparing them with the facts of some other languages. I shall argue the inadequacy of the current formal devices that describe movement (and suggest a solution) at the end of the paper.

The paper is organized as follows. In §1, I outline (and adopt) an earlier proposal of mine about how to generate the position of a wh-phrase in a simplex sentence of Malayalam. I also look at Malayalam clefts. In §2, I look at multiple wh-fronting in Malayalam and try to explain two ordering constraints on the fronted wh-phrases. In §3, I look at scope-marking strategies in Malayalam questions, which involve clefting or clausal pied-piping (or both), and briefly compare the clausal pied-piping in Malayalam with clausal pied-piping in Basque and with the “partial wh-movement” strategy of Hungarian. In §4, I argue the inadequacy of “Attract” in describing wh-movement in Malayalam and make a proposal about a certain type of ‘probe’.

As is well-known, SOV languages which have a clause-final complementizer do not move a wh-phrase into a clause-final position (assuming that the COMP in these languages is clause-final), nor into a clause-initial position. These languages are usually described as wh-in-situ languages. But, as has been noticed for some time, at least some of these languages do not allow a wh-phrase to remain in its ‘canonical’ position; they move it more or less obligatorily to a position immediately to the left of V. Thus consider the following Malayalam sentences:

The (a) sentences illustrate the ‘canonical’ order of the verb and its arguments in Malayalam, which is: ‘Subject–Indirect Object–Direct Object–V’. The (b) sentences, in which the wh-phrase stays in its canonical position, are ungrammatical. Only the (c) sentences, in which the wh-phrase is contiguous to the verb, are acceptable.

The movement of the wh-phrase illustrated here may (at first glance) look like ‘rightward scrambling’. In fact, that was how it was analyzed in Madhavan (1987), where this phenomenon of Malayalam was first noticed. But the difficulty about calling it scrambling is that this movement is obligatory.1

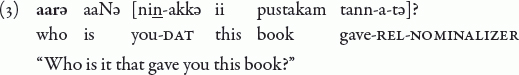

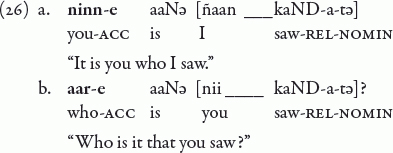

Some of these languages, e.g. Malayalam and Sinhala, in fact prefer a cleft construction in questions, placing the wh-word (or a larger phrase containing the wh-word) in the ‘cleft focus’; cf. (3). (The ‘cleft focus’ is shown in boldface; the ‘cleft clause’ is indicated within brackets.)

But observe that the matrix verb in the cleft construction is the copula and the ‘cleft focus’ is to the immediate left of the copula; so, clefting is also another way of bringing the wh-phrase into the preferred position next to V.

What is the significance of this position? If we were to adopt (for these languages) a “flat” clause structure in which arguments may be generated in any order whatever—i.e., if we were to adopt the ‘non-configurational’ analysis of “free word order” languages proposed by Hale (1983), see Farmer (1980) for an analysis of Japanese along these lines, Mohanan (1982) for a similar account of Malayalam—, the placement of the wh-phrase as the “last phrase” preceding the verb could perhaps be attributed to prosodic factors.2 But if we assume binary branching, and if we also postulate an underlying OV order in the VP, there is an acute problem. How do we generate a COMP-like position within VP, between the direct object and the verb? In a sentence like (1c) or (2c), how do we “lower” the subject into this position?

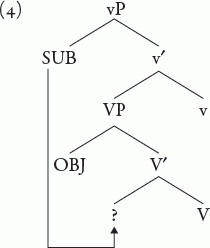

In Jayaseelan (1996, 1999, 2001a) I proposed a solution along the following lines. A Focus Phrase immediately above vP/VP (into which wh-phrases and other focused phrases are moved) has been postulated in a number of languages; e.g. Hungarian (Brody 1990), Basque (Laka and Uriagereka 1987), Chadic (Tuller 1992), Kirundi (Ndayiragije 1999). Assume that Malayalam also has such a Focus Phrase. Assume (with Kayne 1994) that the OV order is derived: in languages with this surface order, the verb’s arguments have actually all moved out of the VP. Now, this “VP vacating” movement of the verb’s arguments will move them “past” the Focus Phrase, as illustrated below for (2c):

In the case of a clefted structure like (3), we assume that the cleft clause is generated as the complement of the copula, and that the wh-phrase has moved out of the cleft clause (by a relativization process, to which we come back later) into the Spec of a FocP above the copula:3

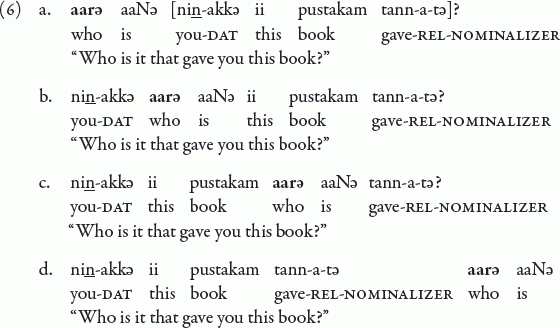

In Malayalam clefts, the cleft focus plus the copula can (superficially speaking) “float into” the cleft clause. (This ‘floating’ phenomenon is attested also in Chinese and Sinhala clefts.) Thus consider the following sentences:

(6a) (= (3)) has the cleft focus and the copula preceding the cleft clause; (6d) has them following the cleft clause. But in (6b) and (6c), the cleft clause appears to have disappeared as a unit: the focus-plus-copula, behaving like a constituent, seems to have moved into the ‘middle’ of the cleft clause.

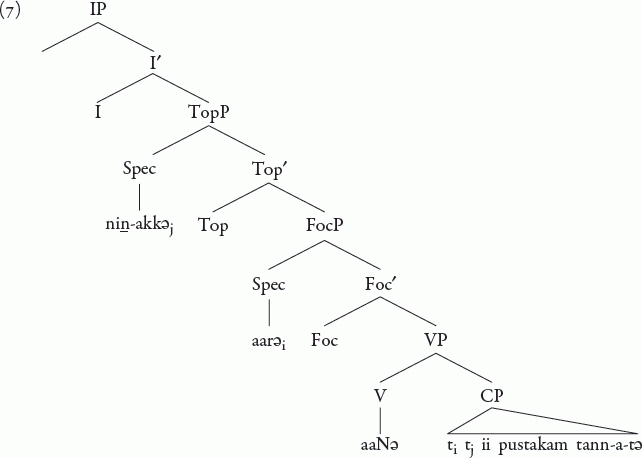

This “free floating” of the Focus looks like a typical instance of scrambling.4 However, in Jayaseelan (1999, 2001a) I pointed out that the phrases occurring to the left of the cleft focus are subject to a definiteness/specificity constraint; and suggested that these phrases are in fact topicalized in IP-internal Topic positions (which are generated higher than the FocP above vP/VP). Thus (6b) will have the following structure (according to this analysis):

The point of going through this analysis of clefts here is the following: Malayalam (as we said) normally uses a cleft construction in constituent questions. Owing to the “floating” phenomenon we outlined above, the wh-phrase appears to freely occur anywhere in the sentence. However, this “freedom” is illusory. The wh-phrase always moves into a fixed position, namely the Spec of a FocP above a vP/VP; and this is true of a clefted question no less than of a non-clefted question.

English also makes use of the FocP above vP/VP in its cleft construction and in several other constructions (as argued at some length in Jayaseelan 2001a). So it seems reasonable to say that this FocP is available in all language types.

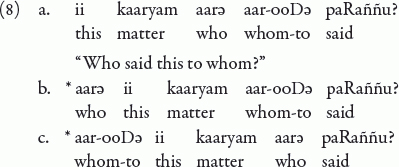

In multiple questions in Malayalam, every wh-phrase must be in the Focus position, cf. (8):5

(8a) is a fine sentence because both the wh-phrases are in the Focus position. (8b) and (8c) are out because one of the wh-phrases has not moved to the Focus position. We assume that the FocP above vP/VP is iterable, and that all the wh-phrases are in SpecFocP.6

If we employ a cleft construction (which is in fact preferred, as we said earlier), the wh-phrases are similarly “stacked” in the cleft focus:

We note that in (9b), the wh-phrase “left behind” in the cleft clause, namely aar-ooDə ‘whom-to’, could very well be in the Focus position of that clause since it is contiguous to V. But apparently, that is not enough—all wh-phrases must move into the cleft focus.)

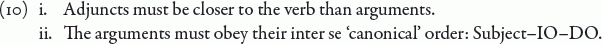

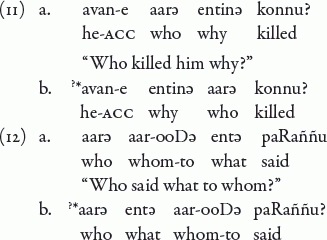

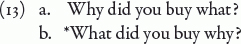

The interesting thing about the “stacked” wh-phrases is that they obey the following ordering restrictions:

Thus in the following sentences, the (b) sentences are bad, only the (a) sentences are acceptable:

As regards the restriction (10i), Watanabe (1992)—discussing parallel facts in Japanese7—rightly suggests that the explanation of this restriction ought to be related to that of the English restriction illustrated below:

In descriptive terms, an adjunct wh-phrase must move into COMP (overtly) in English.

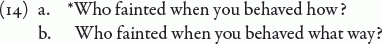

The earlier explanation of the English data was in terms of a COMP-indexing algorithm and the ECP (see Huang 1982). However there is an alternative solution to the English problem, offered by Reinhart (1993). Reinhart points out (about English) that the problem under discussion is not actually a general problem with wh-adjuncts, it is restricted to wh-adverbs. Cf. (14) (Reinhart’s examples):

Only ‘how’ needs to be obligatorily in COMP; ‘what way’ can be in situ.

Reinhart’s solution to this puzzle is to say that “wh-adverbials are only interpretable in SpecCP”; she base-generates them in SpecQP, the QP being in COMP. For us, the essence of the Reinhart proposal is that wh-adverbs do not need to leave a trace in the VP, unlike arguments; therefore they can be generated directly in an A-bar position.8 Adapting the Reinhart proposal to a claim of Rizzi (1997) that wh-phrases in English move to the Spec of a FocP in COMP, let us say that wh-adverbs are base-generated in SpecFocP. In English, since the FocP in COMP is non-iterable, there can be only one such question word per clause. Also, once a wh-adverb is base-generated in SpecFocP, no other wh-phrase can move into COMP. But the Malayalam Focus position above vP/VP has no such restriction. Any number of wh-adverbs can be base-generated in SpecFocP, and any number of wh-arguments can be moved into SpecFocP. Cf. (15):

But still, how do we get the adverbs closer to V than the arguments? The answer is straightforward, if we adopt Chomsky’s claim that “Merge takes precedence over Move” (Chomsky 1995:348). At the point (in the derivation) when a Focus head is merged to VP, if there is a wh-adverb in the numeration, this is merged in the Spec position of the Focus Phrase, in preference to a wh-argument being moved into that position. A wh-argument is moved into the Spec of a later-merged (higher) Focus head. This gives us a neat account of the ordering restriction (10i).9

Our argument above was couched in terms of an iterable FocP. However (as noted earlier), an alternative possibility is to assume a single FocP with multiple Spec positions. If we adopt this alternative, there arises the possibility of ‘tuck in’: when two movements target the Spec positions of the same head, a subsequent movement may ‘tuck in’ beneath an earlier movement (trying to be “closest” to the head) (see Chomsky 1998[2000:137]). Now in the ordering of wh-argument and wh-adjunct in the Focus position, if the adjunct is merged first and the argument ‘tucks in’ below the adjunct—the fact that one is a case of ‘pure’ merge and the other a case of copy and merge ought to make no difference—, we should get the wrong order, namely ‘adjunct–argument–V’. Obviously, ‘tuck in’ does not happen here.

This brings us to the constraint (10ii), which says that in the Focus position, the wh-arguments must preserve their inter se canonical order. This constraint, observed in a multiple wh-fronting language like Bulgarian, was the original motivation for Richards’s (1997; 1999) proposal of ‘tuck in’. Thus consider the following Bulgarian data (Rudin 1988:472–473):

Here (the claim is) the subject (the superior argument) moves into SpecCP first; and the object, when it moves subsequently, moves into a lower Spec position of CP, thereby preserving the canonical ‘Subject–DO’ order. The movements of the wh-phrases into SpecCP (in other words) are obligatorily ‘crossing’ movements.

However Balusu (2002) has shown that if, as implied by the phase theory (Chomsky 1998, 1999, 2001), wh-movement to SpecCP is a two-step movement—one movement to the edge of vP, and a second movement to the edge of CP—, two sets of nested movements of the wh-phrases will give us the base order of these phrases. If this analysis is correct, we can possibly dispense with the notion of ‘tuck in’; and the possible argument (outlined above) against our account of the constraint (10i), loses its force.

About the constraint (10ii), let us say the following: In Malayalam, the wh-phrases move only one step, to the edge of vP. So, with nested movements, we should get the mirror image of the base order. We have no way of ascertaining the base order of arguments in the Malayalam vP, since both wh- and non-wh- arguments move out of the vP. But let us assume that the order of superiority in the vP is ‘Subject–DO–IO’ (the same as in English). Nested movements of non-wh- arguments into their ‘canonical’ positions should give us the order ‘IO–DO–Subject’; but the order we find is ‘Subject–IO–DO’. We explain this by saying that the subject is subsequently topicalized. We can say the same things about the movements of the wh-arguments. These move into the Spec position of FocPs by nested movements, giving the order ‘IO–DO–Subject’. The subject then gets topicalized among the set of focused phrases, giving the order ‘Subject–IO–DO’ (see Balusu (2002) for details).

We adverted earlier to Rizzi’s (1997) claim that COMP—which comprises many phrases—contains a Focus Phrase (FocP), and English wh-phrases move into the Spec of this FocP. If we adopt this analysis, the difference as regards wh-movement between English and Malayalam is simply stated: English moves a wh-phrase into a FocP above IP, Malayalam moves it into a FocP above vP/VP.

An interesting question arises here: Why doesn’t Malayalam move its wh-phrases “all the way up” to a FocP in COMP like English does? (The FocP in COMP is presumably universally available.)

Kayne (1994:54) offered an explanation of why languages which have a clause-final complementizer never show question movement into COMP. The complementizer (which is in C0) takes its IP complement to the right; but the IP then moves into SpecCP. Therefore, SpecCP is no longer “free” to accommodate a wh-phrase.

Unfortunately, this explanation does not work very well, if we adopt Rizzi’s ‘expanded COMP’. Rizzi’s structure for the COMP is as follows:

The head of Force Phrase (ForceP) expresses such facts as whether the sentence is declarative or interrogative; in a question, it will presumably host the “Q-operator” (cf. Baker 1970). At the lower end, the head of Finiteness Phrase (FinP) hosts the complementizer, which determines whether the sentence is finite or infinitival. In between, there can be a Focus Phrase (FocP), flanked on both sides by iterable Topic Phrases (TopPs); both FocP and TopP are optional.

If we adopt this structure without modification, and grant that SpecFocP is the landing site of wh-movement, Kayne’s explanation will go through only if IP-preposing targets SpecFocP; but this is difficult to maintain. If IP were to move into SpecFinP, or even SpecForceP, we ought to still be able to generate a FocP and move a wh-phrase into its Spec position. Thus, if the IP were in SpecFinP, a wh-phrase ought to be able to show up in the left periphery of the clause (with the complementizer at the right periphery); and if the IP were in SpecForceP, a wh-phrase ought to show up in the right periphery of the clause (followed by the complementizer). But as we know, neither possibility is realized.

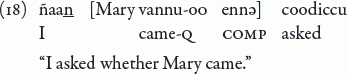

However let us examine whether the structure shown in (17) is actually right for Malayalam. I have argued elsewhere (Jayaseelan 2001b) that the Q-operator, although it is always abstract in English, is realized as the disjunction marker -oo in Malayalam,10 and ka in Japanese. The Malayalam complementizer is ennə. Now consider a sentence like (18), which has an embedded yes/no question:

Observe that -oo precedes ennə. I assume that -oo is generated as the head of ForceP, and ennə as the head of FinP.

Now, regarding a head-final language like Malayalam (or Japanese), it is known that the order of elements at the end of the clause is the mirror-image of the order of these elements in an English-type language. Kayne (1994:52–53) proposes to generate this mirror-image order by a “roll-up” operation: thus, IP raises into the Spec of the first phrase dominating it, and the resulting structure moves into the Spec of the next phrase dominating it, and so on. Given this, the surface order -oo > ennə compels us to generate the ForceP lower than the FinP. Cf. (19):

We have no evidence of any phrase that can be generated between FinP and ForceP in (19) (in the space indicated by a dotted line). But suppose a FocP were generable in this space. A wh-phrase in IP will not raise into the Spec of this FocP, because it would be raising ‘past’ the question operator, and would thereby become inaccessible to it. If our phrase structural claims here are on the right track, we now have an explanation of why languages which have a clause-final complementizer never show wh-movement into COMP.

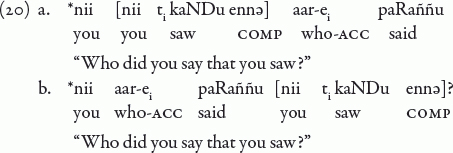

The fact that there is no wh-movement into COMP has an implication for scope-marking in questions. In English, if a wh-phrase in an embedded clause has matrix scope, it moves successive-cyclically to the matrix COMP. In Malayalam, this way of indicating scope is unavailable, because the Focus position of the COMP is not available as an “escape hatch”.11 Thus a sentence in which a wh-phrase from an embedded clause shows up in the Focus position of the matrix clause is ungrammatical:

In (20a), the wh-phrase is shown in the Focus position of the matrix clause, and the embedded clause (from which the wh-phrase has been extracted) is shown in the canonical position of the direct object. (All canonical positions, as we know, are to the left of the Focus position, speaking in linear terms; see (2c′).) In (20b), the embedded clause is shown “extraposed” to the right of the matrix clause.12 As we see, both sentences are equally ungrammatical.13 The nearest one can come to a sentence like (20a) or (20b) is:

Here (obviously) the wh-phrase is generated in the matrix clause (as an oblique argument of the matrix verb); and a pronoun in the embedded clause is interpreted as coreferential with it. Crucially, the wh-phrase is not moved out of any clause here.

Since “long extraction” by focus-to-focus movement is not available, how do languages without wh-movement to COMP express scope? The current answer is that this is done by LF movement. While this might be true of some of these languages, it is not true of Malayalam. Malayalam requires scope to be indicated in the overt syntax. It employs two different devices to achieve this. One is a strategy of clefting. The other is a strategy of “clausal pied-piping”.

Consider the following cleft sentence:

The question word is the cleft focus here; and it is extracted from a clause embedded within the cleft clause. The extraction can take place from any depth of embedding, cf. (23); provided there is no intervening island boundary, cf. (24):

The island effect clearly demonstrates that there is movement here. The facts are parallel to those of English, in which the extraction of the cleft focus can take place from any depth of embedding, but not across an island. But now, we have just shown that Malayalam (unlike English) cannot move a wh-phrase into COMP and therefore cannot extract a wh-phrase from an embedded clause. The question arises: How then is extraction possible in the case of clefts?

The answer seems to be that clefting makes use of relativization, not question movement; and that relativization has an “escape hatch” in the Malayalam clause. There is morphological evidence for relativization in the Malayalam cleft. The Malayalam relative clause has a clause-final particle -a:15

Assuming a raising analysis of relatives, we can say that in (25), kuTTi ‘(the) child’ is raised from the shown gap; and that -a is a relative proform (corresponding to English relative pronouns, but invariant). Now in the cleft construction, the cleft clause has a clause-final suffix -atə, which is morphologically complex: it consists of -a (the same -a that occurs in relative clauses, plausibly) and -tə (which is a third person, singular, neutral agreement, see Anandan 1985 for a more detailed analysis). We shall gloss them (and have done so earlier) as ‘relativizer’ and ‘nominalizer’ respectively:

We may add that relativization has the properties of clefting that we noted: it can extract a phrase from any depth of embedding, but is sensitive to island constraints (see Mohanan 1984 for a discussion of this latter property of relativization).

We said that relativization has an “escape hatch” in the Malayalam clause. This could be a Topic position in the ‘space’ between FinP and ForceP, or even the Spec of ForceP (see (19)). We cannot ascertain its position vis-à-vis the complementizer ennə (which we assumed heads FinP), because ennə never cooccurs with the relativizer -a of the relative clause.

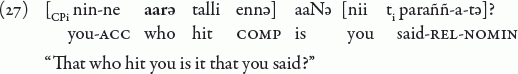

In our examples of scope marking by clefting, we have so far illustrated only cases where the extracted element is just the question word (wh-phrase). But Malayalam also often extracts the whole embedded clause containing the wh-phrase to the cleft focus:16

Note that the wh-phrase has moved into the Focus position in its own clause. Without this movement, the sentence is somewhat unacceptable:

There are (then) two movements in (27): the movement of the wh-phrase into SpecFocP in its own clause, and the movement of the embedded clause to ‘cleft focus’. (27) can therefore be considered an instance of our second scope-marking strategy, to which we now turn.

Consider the following sentence:

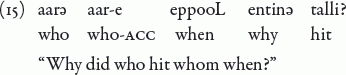

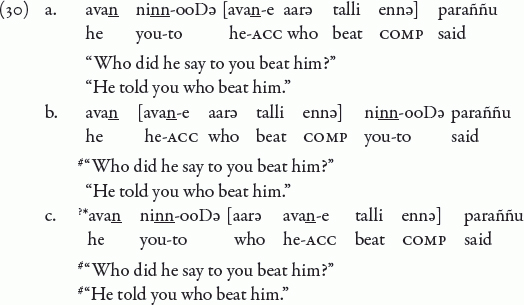

This sentence has only an indirect question reading. (It is well-formed as an indirect question, for notice that the wh-phrase has moved to the Focus position of the embedded clause.) If one wishes to express matrix scope, this is done by two movements: (i) the wh-phrase moves into the Focus position of the embedded clause, and (ii) the whole embedded clause moves into the Focus position of the matrix clause. Consider (30):

(30a) is a good matrix question: the wh-phrase aarə ‘who’ occurs to the immediate left of the embedded verb talli ‘beat’, and the embedded clause occurs to the immediate left of the matix verb paraññu ‘said’, showing that the two movements that are required for matrix scope have taken place. (30a) can also be an indirect question (‘He told you who beat him’), since the only requirement for this reading—namely that the wh-phrase should be in the Focus position of the embedded clause—is also met.17 (30a), in other words, is ambiguous as regards the scope of the question.

(30b) is bad as a matrix question (‘#’ indicates the unavailability of a reading), because the second of the above-mentioned movements—the movement of the embedded clause to the Focus position of the matrix clause—has not taken place. This is shown by the non-contiguity of the embedded clause to the matrix verb. This sentence (however) is fine as an embedded question, because the wh-phrase is in the Focus position of the embedded clause (i.e. the first of the above-mentioned movements has taken place).

In (30c), the first movement has not taken place, but the second movement has. The sentence is not acceptable either as an embedded question or as a matrix question. (For a good embedded question, the first movement is required; and for a good matrix question, both movements are required.)

Let me first note some parallels with two Indo-Aryan languages—Hindi and Bangla—, since the facts of these languages have been noticed and fairly widely discussed in the literature. In Hindi, an embedded tensed clause is obligatorily “extraposed” to the right of the matrix verb; and a wh-phrase in this extraposed clause has only narrow scope. Cf. (31) (example from Srivastav (1989), cited by Bayer (1996:275)):

In Bangla, an embedded tensed clause can either be “extraposed” to the right (like in Hindi), or be in the canonical position of the direct object which is to the left of the matrix verb. In the first case, a wh-phrase in the embedded clause can have only narrow scope; in the second case, it can have narrow or wide scope. Cf. (32) (examples from Bayer 1996:272, 273):

Srivastav (1989; 1991a,b) tries to explain the narrow scope of the wh-phrase in the extraposed clause of Hindi in essentially the following terms: the extraposed clause is an adjunct, and an adjunct is a barrier for movement. Bayer (1996) offers an explanation of the scope of the Bangla wh-phrase—narrow in the extraposed clause, narrow or wide in the non-extraposed clause—in terms of directionality of government: the wh-phrase cannot move out of the extraposed clause because the clause is governed by the matrix verb in a non-canonical direction.

Both these explanations assume that the crucial contrast is between extraposed and non-extraposed embedded clauses. Let me note that at least in Malayalam, this is not the case. (29) and (30b) allow only narrow scope for the question, and contrast with (30a) which shows scope ambiguity. Only (29) has an extraposed clause; (30b) does not. The crucial difference (we are claiming) is whether the embedded clause is in the Focus position of the matrix clause or not. In (30a), it is; in (29) and (30b), it is not.

Now let us note some facts of Basque, which uses the Malayalam strategy of clausal pied-piping for marking the scope of questions (Mey & Marácz 1986, Ortiz de Urbina 1990). Thus, cf. (33) (example cited by Mey & Marácz (1986), from Azkarate et al. (1982)):

Basque has a Focus position immediately preceding the verb;18 and in (33), as Mey and Marácz point out, the embedded clause is in the matrix Focus position, and the wh-phrase nork is in the embedded Focus position.

Basque also permits extraction of a wh-phrase from an embedded clause, like English (examples (34) and (35) from Ortiz de Urbina (1990)):

The phrase so extracted can be a pied-piped clause:

This possibility does not exist in Malayalam, for reasons we have already explained.19

There is an interesting comparison between the “clausal pied-piping” strategy of Malayalam and Basque20 and the “partial wh-movement” strategy which has been studied in a wide variety of languages—e.g. Hungarian (Mey & Marácz 1986, Horvath 1997), German, Romani (McDaniel 1989), and Hindi (Dayal 1994). We shall confine our discussion here to Hungarian.

Hungarian has a Focus position to the immediate left of V in linear terms. There is some debate about whether the FocP should be generated above VP or S (i.e. IP) (see Szabolczi 1983:99–100); but possibly the question is vacuous if Brody (1990) is right in his claim that Hungarian has no IP projection at all, only a “focus field” above VP. Wh-phrases are obligatorily moved into this Focus position. Hungarian (like English) can employ focus-to-focus movement to indicate the scope of a wh-phrase; cf. (36) (example from Mey & Marácz (1986:259)):

In the construction we are interested in (however), the wh-phrase only moves to the Focus position in the minimal clause; but if the question operator is generated in the COMP of a superordinate clause, the Focus position of that clause, and that of every intervening clause, hosts a “dummy” wh-element (example from Horvath (1997)):

In (37), the wh-phrase kinek ‘to whom’ is in the Focus position of the clause it is generated in; but the Focus position of each of the superordinate clauses contains a “dummy” wh-phrase mit ‘what-ACC’, indicating the fact that the sentence is meant as a direct question.

Horvath (1997) gives several arguments to show that the “dummy” proform is generated in the clause it is found in (generated in an A position, moved to the Focus position); and that it is associated, not directly with the wh-phrase, but with the embedded CP. Thus in (37), the first mit is associated with the intermediate clause, and the second mit with the most deeply embedded clause. In LF, each embedded CP is adjoined to the “dummy” proform it is associated with. Since pleonastic elements, which receive no interpretation, are deleted in LF (Chomsky 1995), in effect the embedded CP “substitutes” into the position of the dummy element. Horvath terms this ‘expletive replacement’.

Now observe that what we get in the overt syntax of Malayalam is like what Horvath’s analysis claims is the LF representation of a sentence like (37) in Hungarian.

It may be recalled that in an earlier stage of the theory, A movement and A-bar movement were implemented by different means. A movement was induced by the need of lexical NPs to get Case; whereas A-bar movement, or at least the movement of wh-phrases and quantifiers, was motivated by the need to indicate scope. Movement itself was taken as optional and free. However in the current theory (Chomsky 1998, 1999), Case-checking and movement are independent of each other: Case-checking is done in-situ by a ‘probe’, while A movement itself is induced by an EPP feature of T0. In the case of A-bar movement (too), wh-movement is induced by an EPP feature which is optionally assigned to C0 and v0. There is thus a unification in the treatment of movement: all movement is induced by an EPP feature of the target.

T0 is obligatorily endowed with an EPP feature. In the case of wh-movement, C0 and v0 (as we said) are given an EPP feature, but optionally. In a language like English this does not give rise to any obvious problem. One (and only one) wh-phrase moves to SpecCP in an English interrogative clause. This can be described by stipulating that (as a parametric property of the language) a C0 which is [+ interrogative] must obligatorily have an EPP feature.

There is a potential problem in the case of multiple wh-fronting languages. As a preliminary to presenting this problem, first let us look at some typological claims made about these languages. Rudin (1988) divides the multiple wh-fronting languages she considers into two types. In the Bulgarian-Romanian type (she claims), all the wh-phrases move into SpecCP. In the Serbo-Croatian-Polish-Czech type, only the first wh-phrase is in SpecCP; all the others are adjoined to IP. Bošković (1999) gives a somewhat different analysis: In Bulgarian (he claims), only the first wh-phrase moves by wh-movement, the other wh-phrases move by focus movement. (However all of them target SpecCP.) He suggests that in Serbo-Croatian, all wh-phrases move by focus movement.

In Malayalam, the multiple wh-movement to the Focus position above vP is clearly a case of focus movement. Whether a theoretical distinction between wh-movement and focus movement is valid, is a separate question that need not detain us here.21

Now let us come back to the potential problem in the case of multiple wh-fronting languages. Assuming EPP-driven movement—and cutting across any wh-movement/focus movement distinction by claiming that the head of FocP also (like interrogative C0) has an EPP feature—, we can state the problem as follows: How do we ensure that a [+ interrogative] C0 (or a Foc0) has just the right number of EPP features? If there are too few EPP features, one or more of the wh-phrases will not move to SpecCP (or SpecFocP), which is inadmissible in these languages. If there are too many EPP features, one or more of the EPP features will not be deleted and the derivation will crash.22

Instead of speaking about the ‘number’ of EPP features (however), one can also speak of a single EPP feature which has a parameterized property that enables it to not ‘erase’ when checked and therefore can “reapply” (an indefinite number of times). The idea, proposed by Chomsky (Chomsky 1995:280–281), is that there is a distinction between ‘delete’ and ‘erase’: a ‘deleted’ element is still accessible to the computation; it is only an ‘erased’ element—‘erasure’ is a “stronger form” of deletion—that is eliminated altogether. Some −Interpretable features which enter into a checking relation may (Chomsky suggests) escape erasure after checking (as a parameterized property) and so enter into a checking relation repeatedly. Chomsky adds that a feature which (in the manner suggested above) is deleted but not erased “optionally eras[es] at some point to ensure convergence” (ibid.: 286). We can make use of this idea and say that in a multiple wh-fronting language, the EPP feature of C0 (or Foc0) escapes erasure after inducing a movement and so can induce another movement, and yet another movement, and so on. It erases eventually to ensure convergence. This seems to get around the problems noted in the last paragraph.23

A modified version of the above idea has in fact been proposed as a solution to the problem of multiple wh-fronting. In order to explain the Bulgarian movements, Bošković (1999) suggests that the Bulgarian [+ interrogative] C0 has—besides a [+ WH] feature which induces the wh-movement of the first wh-phrase—an “attract-all-F” feature, which has the property of repeatedly attracting focused elements in its domain until all of them have been moved up. Possibly, Serbo-Croatian can also be dealt with by the same device: we can—translating Rudin’s IP-adjunction suggestion into current terms—think of I0 having an “attract-all-F” feature. (Should this feature be made dependent on a [+ interrogative] C0? If so, can this be done by a selectional property of C0? We shall see presently however that the answer to the first question is in the negative.)

Coming to Malayalam, are the Malayalam wh-movements amenable to description by an “attract-all-F” feature? Consider a sentence like (38), and its cleft counterpart (39):

There are two movements here, but for the time being let us look at only the multiple wh-fronting to the Focus position above the vP in the embedded clause. Earlier we spoke in terms of an iterable FocP above vP to accommodate these movements. But how do we ensure that the ‘right’ number of FocPs are generated above vP? If we make a different analysis (however) and assume a single FocP with the possibility of multiple Spec positions, we can say that Foc0 (in Malayalam) has an “attract-all-F” feature; and we now seem to be able to handle the multiple wh-fronting facts.

Alternatively, if we adopt Chomsky’s (1992, 1995, 1998) analysis of wh-extraction from vP, where the wh-phrase moves to an “outer” Spec position of vP, we can say that v0 has an “attract-all-F” feature in the embedded clauses of (38) and (39). This seems (again) unproblematic.

But a question arises. In English, an obligatory EPP feature is given only to an interrogative C0. Should the “attract-all-F” feature of v0 (or Foc0) in Malayalam also be (similarly) made dependent on an interrogative C0? If so, how do we express this dependency? Note that in a sentence like (38) or (39), the C0 hosting the question operator is ‘far above’ the v0 (or Foc0) which attracts the multiple wh-phrases.

It is when we consider this question that we realize a difference between Chomsky’s solution to the problem of multiple checking by a feature, and Bošković’s solution. Chomsky’s −Interpretable feature F must check at least once, although—if it has the property of escaping erasure—it can check again, and again, and so on. But Bošković’s “attact-all-F” feature can apply vacuously. Thus Bošković writes (Bošković 1999:fn.23):

Notice also that although a head with an Attract-all-X property obligatorily undergoes multiple checking if more than one X is present in the structure, it does not have to undergo checking at all if no X is present. The Attract-all-X property is then trivially satisfied.

Given this, the Bulgarian C0 can have the “attract-all-F” feature in a declarative clause as well as an interrogative clause; i.e. the feature can be an invariant property of Bulgarian C0. Similarly, Serbo-Croatian I0, or Malayalam v0 (or Foc0) can have this feature as an invariant property.

This seems to solve the Malayalam problems exceedingly well. In (38) (or (39)), the embedded v0 (or Foc0)—because it has the “attract-all-F” property—attracts all the wh-phrases to it; then the matrix v0 (or Foc0)—because it too has this property—pied-pipes the entire embedded clause to it, because it cannot extract the wh-phrases from the embedded clause.

However, we should find the vacuous application of the “attract-all-F” feature disturbing. This is because the theory of checking is based on the idea of ‘deficiency’. When we say that the target attracts, we are saying that the deficiency that needs to be remedied is in the target. Similarly when we say that there is a ‘strong feature’ that needs to be checked in the XP or X0 category which moves, we are saying that the deficiency is in the element which moves. Now, a head which can be satisfied by a vacuous application of checking cannot be deficient.

Where then is the deficiency that drives the movements here? It must be in the wh-phrases which move! So we are back to a theory where there are ‘strong features’ in the elements which move—although Bošković presents his “attract-all-F” feature as a solution that obviates the need for precisely this type of theory.

Should we then go back to this older theory and postulate a strong feature in the wh-phrases of Malayalam? Unfortunately, this will not do either. As we said earlier, there are two movements in a sentence like (30a), or (38), or (39): the wh-phrase in the embedded clause moves into the Focus position in its own clause, and then the embedded clause moves into the Focus position in the matrix clause. A strong feature in the wh-phrase will be checked and deleted (presumably erased) at the end of the first movement. So, what will drive the second movement?24

Can we adopt (for Malayalam) the Chomskyan solution, where the attracting feature must check at least once, although it can go on to check a number of times? But this type of an EPP feature on v0 (or Foc0) must be made dependent either on an interrogative C0 in the sentence, or on the presence of a wh-phrase in the vP. As we said earlier, the interrogative C0 can be indefinitely far away from the v0 (or Foc0) that must receive the EPP feature, so it is impossible to express a dependency here. Making the EPP feature dependent on the presence of a wh-phrase in the vP is even more problematic. We must have a way of ensuring that when a subarray of a numeration contains a question word, it also contains a v0 (or Foc0) with an EPP feature. The problem is compounded by clausal pied-piping, since the matrix v0 (or Foc0) also must have an EPP feature. That is, it must be ensured that when a subarray contains a question word, a later-accessed subarray must contain a v0 (or Foc0) with an EPP feature. These problems appear to be insuperable.

It is in view of this situation that I wish to suggest that we should look at another possibility. I argue below that a parameterized property of the question interpretation algorithm in languages may be able to describe multiple wh-movement adequately.

In Jayaseelan (2001b) I give several arguments to show that the question operator accesses question words by “association with focus”. Syntactically, let us think of “association with focus” as a ‘probe’ which the operator sends “down the tree”, to find an element with the feature [+ Focus]. The probe appears to have at least the following properties. It does not “stop” when it finds its first focused element, but goes on to search its entire c-command domain for elements with this feature. (Thus a question operator can unselectively bind several wh-words, i.e. variables.)25 A probe can choose to bind, or not bind, a [+ Focus] element that it finds; but if it binds it, this element is “closed” to other probes. (I.e., a variable cannot be bound by two operators.) A probe cannot “skip” a potential ‘goal’ which is not “closed off” in the above-mentioned manner, and bind a farther-off ‘goal’. (Cf. the ‘nested’ pattern of interpretation in sentences with two question operators, noted by Pesetsky (1982).)

The “association with focus” probe (as we said) seeks an element with the feature [+ Focus]. But let us say that in some languages—presumably languages with strong focusing devices like Malayalam or Bulgarian—, the question operator is more narrowly targeted at a Focus position. I.e., the probe “sees” only Focus positions. (One can also think of this as a “least effort” strategy of the search algorithm; or formalize this as a feature which the Foc0 head of the “strongly focusing” languages have, which the probe targets.) In Malayalam, the only Focus position generated is the one above vP; possibly in Bulgarian the only Focus position is the one in COMP. Therefore the wh-phrases cluster in these positions in these languages.

But to explain Malayalam fully, we must also take into account a locality restriction placed on the question operator’s probe by the phase theory, specifically the Phase Impenetrability Condition (PIC) (Chomsky 1998, 1999). A question operator in the COMP of the matrix clause can “see” only the ‘edge’ of the highest vP in its domain (i.e. the matrix vP), or higher. Given that the Malayalam question operator’s probe sees only Focus positions, a wh-phrase in an embedded clause must (therefore) appear in the Focus position above the matrix vP, if it is to be interpreted by the matrix question operator. Since a wh-phrase cannot be extracted from the embedded clause, the language pied-pipes the embedded clause to the Focus position above the matrix vP.

The interpretation now goes as follows. In a sentence like (30a) on the matrix question reading, the question operator’s probe—starting from the matrix COMP—first looks at the only Focus position accessible to it, namely the one above the matrix vP. It finds a pied-piped clause there. It now looks for the Focus position of this clause in a recursive step, and finds a wh-phrase there which it interprets.26

To conclude: Our account of multiple wh-fronting and clausal pied-piping in Malayalam has the following theoretical advantages. It leaves the theory of EPP-driven phrasal movement undisturbed. (It does not postulate a strong feature in the phrase which moves, either explicitly or covertly.) It also allows us to maintain that Focus (and Topic) positions are generated optionally in the architecture of the clause. (But the ‘right’ number of Focus positions will nevertheless be generated. For if there are ‘too many’ FocPs, the EPP feature of one or more of the FocPs will not be deleted and the derivation will crash; and if there are ‘too few’ FocPs, one or more of the wh-phrases in the sentence will not move into a Focus position and—owing to the parameterized property of the question operator’s probe—will not be interpreted.)

1. In Tamil or Japanese, where there is only a tendency to place the wh-phrase next to the verb, a scrambling analysis is much more plausible. Japanese linguistics, till recently, appears to have adopted such an analysis by and large; but see Kobayashi (2000) for a focus movement proposal for (some instances of) Japanese multiple questions. See also Jayaseelan (2001a, 2001c) for an argument that all clause-internal scrambling ought to be explained in terms of focus movement or topicalization. If this claim is granted, the question of choosing between scrambling and focus movement becomes vacuous. Rather, the question must be restated as: why is focus movement optional for Tamil/Japanese wh-phrases, and obligatory for Malayalam wh-phrases?

2. Thus, Hock (2001) has some very interesting arguments for a prosodic approach to the placement of Focus immediately to the left of V in Sanskrit.

3. In (5), SpecIP is probably filled by pro, Malayalam being a pro-drop language; see for details, and a comparison of English and Malayalam clefts, Jayaseelan (1999, 2001a).

4. Which was how it was analyzed in Madhavan (1987), where it was also assumed that the copula was cliticized to the Focus.

5. In Malayalam, a multiple question sounds better (for some reason) if it is embedded. Although I have abstracted away from this in the following examples in the interests of simplicity, a reader who knows Malayalam can consider these sentences as embedded in a matrix clause saying (e.g.):

6. Alternatively we can assume a FocP with multiple Spec positions—we come back to this question later.

7. In Japanese (as we said earlier), the focus movement of a wh-phrase is optional; and this optionality applies to wh-adjuncts also. But when a wh-adjunct and a wh-argument both are in the Focus position, the restriction we stated as (10i) is observd in Japanese. Saito (1989) tries to account for it in terms of the ‘path containment condition’ (Pesetsky 1982) and the ECP; and Watanabe (1992) tries to explain it in terms of an “anti-superiority principle” that applies to the LF-movement of wh-phrases in Japanese, again in conjunction with the ECP. In the current theory we must look for an alternative explanation that does not appeal to the ECP. However, the explanation we offer below for the Malayalam facts does not carry over straightforwardly to Japanese, see fn. 9.

8. The A/A-bar distinction has only a “taxonomic role” in the current theory (Chomsky 1995:276).

9. This account needs to be qualified for Japanese, because a Japanese wh-adjunct is apparently not obligatorily merged in SpecFocP. Thus the following Japanese sentence is fine (sentence provided by a reviewer for this volume):

Likewise in German, a sentence like “I wonder who left why/how” is acceptable (Haider 1986). It could be a parametric property of English and Malayalam (but not Japanese or German) that their wh-adverbs are obligatorily merged in SpecFocP.

10. In wh-questions, the -oo is deleted in present day Malayalam; hence its absence in example sentences like (1c) and (2c). The -oo surfaces in a yes/no question (however), cf. (18) below.

11. We can restate the “escape hatch” idea in current terms as follows: if a wh-phrase has not moved into the left periphery of CP (the ‘edge’ of the CP phase), it becomes inaccessible to extraction or interpretation in the next higher phase owing to a ‘Phase Impenetrability Condition’ (PIC) (Chomsky 1998).

12. This type of extraposition of an embedded clause, either to the right or the left of the matrix clause, is common in Malayalam, because Malayalam tries to avoid centre-embedding. (Thus Malayalam is not as strictly head-final as Japanese is.) In Kayne’s framework, we can take it that the embedded clause here is topicalized, with subsequent IP-preposing to a still higher Topic position. Alternatively, we can say that the embedded clause is in its base position, i.e. has not moved out of vP. We would then in effect be claiming that in some SOV languages—e.g. in Malayalam, but not Japanese—a clausal argument can be an exception to the requirement that all elements of the vP should vacate the vP.

13. A sentence like (20b), in which a wh-phrase from an “extraposed” embedded clause shows up in the Focus position of the matrix clause, is apparently grammatical in Bangla, cf. (example from Bayer 1996:279):

14. In a case like (23), the language generally avoids centre embedding by “extraposing” the embedded clauses consistently to the left (as in (23)) or to the right. (See also fn. 12.) However a non-extraposed version of (23) is grammatical, although awkward:

15. We are speaking about the so-called ‘gap’ relative. Malayalam also has a ‘corelative’ construction where the relativized position is occupied by a question word (see Mohanan 1984, Jayaseelan 2001b for some facts about this construction).

16. In fact when the wh-phrase is nominative (i.e. the subject)—as it is in (27) —, its ‘long extraction’ from a clause embedded within the ‘cleft clause’ is somewhat unacceptable:

(Madhavan (1987) tried to account for it in terms of the ECP.) In such cases, the extraction of the whole embedded clause containing the wh-phrase (like in (27)) is more or less obligatory.

17. For the indirect question reading of (30a), it is actually immaterial where the embedded clause is positioned. Thus it could simply be in the direct object’s canonical position, not in SpecFocP. (Recall that the direct object’s position is to the left of the Focus position; and if the FocP is not generated, the direct object will be next to V (see (2c′).)

18. It is unclear to me whether the FocP is generated above vP or in COMP. (There is a similar uncertainty about Hungarian, see below). Basque is an SOV language, so we expect the FocP to be above vP (like in Malayalam); but Ortiz de Urbina (1990) treats the Focus position as being in COMP, explaining its obligatory contiguity to V as due to a V2 phenomenon (op.cit.: 196). This seems plausible in view of the possibility of wh-extraction from an embedded clause in Basque, see (34) (below).

19. Since extraction of a phrase (or a clause) by COMP-to-COMP movement is not possible, the equivalent of (35) would be the following in Malayalam:

The repeated centre-embeddings make the sentence awkward; a cleft construction—actually a “double cleft”—would be preferred in this case:

20. We must add Bangla to this growing list, see Simpson & Bhattacharya (2003).

21. As we discussed earlier, Rizzi (1997) claims that English wh-movement moves a phrase into the Spec of a FocP in COMP. Chomsky (1995, 1998, 1999), echoing the Rizzi claim, suggests that when an EPP feature is optionally assigned to C0 or v0, the latter automatically also gets a ‘P feature’, by which he means a Force, Topic or Focus feature. This claim could be taken to mean that the target of wh-movement in English is a Focus position.

Bošković’s distinction (Bošković 1999) is based on a claim that a multiple question involving wh-movement requires an (obligatory) ‘pair list’ answer; while the same involving only focus movement allows either a ‘single pair’ or a ‘pair list’ answer. (Incidentally, Malayalam multiple questions allow either ‘pair list’ or ‘single pair’ answers, and so are not a problem for Bošković’s claim.)

22. A derivation crashing is not a problem, if there is another derivation which converges. The real problem (therefore) is ‘too few’ EPP features.

23. The “optional erasure” of the EPP feature however needs to be modified: if the EPP feature erases too soon, we will again have the problem of wh-phrases which have not moved to SpecCP (or SpecFocP). Actually, the EPP feature can erase only when its search algorithm for a wh-phrase returns “empty handed”; and it must erase at that point or later.

24. Can we think in terms of a strong feature in the wh-phrase which does not erase after movement? Recall that there can be more than one clausal pied-piping in a Malayalam question, cf. (i) and (ii) of fn.19. Therefore the number of times this feature must escape erasure is indefinite. It is unclear what will trigger the final erasure of the strong feature which will ensure convergence.

25. It should be obvious that the ‘operator’s probe’ that we are postulating here is a very different thing from the ‘probe’ of Chomsky (1998). Chomsky’s probe is a –Interpretable feature of a functional head, which needs to be checked; accordingly, when the checking is done, the probe deletes. Therefore, a Chomskyan probe can check with only one goal. (However, see Hiraiwa (2001) for a version of the Chomskyan probe which can check several goals simultaneously.)

26. Some technical questions that arise regarding the recursive step mentioned, are looked at in some detail in Jayaseelan (2004).

Anandan, K.N. 1985. Predicate Nominals in English and Malayalam. M.Litt. dissertation, Central Institute of English & Foreign Languages, Hyderabad.

Azkarate, M.D., J. Farwell, Ortiz de Urbina & M. Salterelli. 1982. “Word Order and WH-Movement in Basque.” NELS XII ed. by J. Pustejovsky & P. Sells. Amherst, Mass.

Baker, C. L. 1970. “Notes on the Description of English Questions: The Role of an Abstract Question Morpheme.” Foundations of Language 197–219.

Balusu, R. 2002. “Multiple Wh-fronting and Superiority: A Nested Movement Analysis.” CIEFL Occasional Papers in Linguistics 10, Central Institute of English & Foreign Languages, Hyderabad.

Bayer, J. 1996. Directionality and Logical Form: On the Scope of Focusing Particles and Wh-in-situ. Kluwer: Dordrecht.

Bošković, Ž. 1999. “On Multiple Feature Checking: Multiple Wh-Fronting and Multiple Head Movement.” In Working Minimalism, eds. S.D. Epstein & N. Hornstein. Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press.

Brody, M. 1990. “Some Remarks on the Focus Field in Hungarian.” UCL Working Papers in Linguistics 201–225.

Chomsky, N. 1992. “A Minimalist Program for Linguistic Theory.” Ms., MIT. Reprinted in The Minimalist Program by N. Chomsky, 1995. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

——— . 1995. “Categories and Transformations.” In The Minimalist Program by N. Chomsky, 1995. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

——— . 1998. “Minimalist Inquiries: the Framework.” MIT Occasional Paper in Linguistics 15. [Also published in Step by Step, ed. R. Martin, D. Michaels, and J. Uriagereka. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2000. Page references to this volume]

——— . 1999. “Derivation by Phase.” Ms. MIT. [Also in Ken Hale: A Life in Language, ed. M. Kenstowicz. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2001.]

——— . 2001. “Beyond Explanatory Adequacy.” MS., MIT.

Dayal, Veneeta. 1994. “Scope Marking as Indirect WH Dependency.” Natural Language Semantics 2.137–170.

Farmer, A. 1980. On the Interaction of Morphology and Syntax. Doctoral dissertation, MIT.

Haider, H. 1986. “Affect α: A Reply to Lasnik and Saito, On the Nature of Proper Government.” Linguistic Inquiry 17: 113–126.

Hale, K. 1983. “Walpiri and the Grammar of Non-configurational Languages.” Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 1: 5–48.

Hiraiwa, Ken. 2001. “Multiple Agree and the Defective Intervention Constraint in Japanese.” MIT Working Papers in Linguistics 40, 67–80.

Hock, Hans. 2001. Keynote Lecture Delivered at International Conference on South Asian Linguistics III (ICOSAL-3), University of Hyderabad, Hyderabad.

Horvath, J. 1997. “The Status of ‘Wh-Expletives’ and the Partial Wh-Movement Construction of Hungarian.” Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 15: 509–572.

Huang, C.-T.J. 1982. Logical Relations in Chinese and the Theory of Grammar. Doctoral dissertation, MIT.

Jayaseelan, K.A. 1996. “Question-Word Movement to Focus and Scrambling in Malayalam.” Linguistic Analysis 26: 63–83.

——— . 1999. “A Focus Phrase Above vP.” Proceedings of Nanzan GLOW. Nanzan University, Nagoya.

——— . 2001a. “IP-internal Topic and Focus Phrases.” Studia Linguistica 55(1): 39–75.

——— . 2001b. “Questions and Question-Word Incorporating Quantifiers in Malayalam.” Syntax 4(2): 63–93.

——— . 2001c. “Scrambling and the Grammar of the Middle Field in SOV Languages.” Paper presented at the South Asian Languages Analysis (SALA) Roundtable, University of Konstanz, October 2001.

——— . 2004. “Question Movement in Some SOV Languages and the Theory of Feature Checking.” Language and Linguistics 5(1), 5–27.

Kayne, R. 1994. The Antisymmetry of Syntax. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Kobayashi, A. 2000. “The Third Position for a Wh-Phrase.” Linguistic Analysis 30(1–2), 177–215.

Laka, I. & J.Uriagereka. 1987. “Barriers for Basque and vice versa.” NELS 17, 394–408. Department of Linguistics, University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Madhavan, P. 1987. Clefts and Pseudoclefts in English and Malayalam—A Study in Comparative Syntax. Doctoral dissertation, Central Institute of English and Foreign Languages, Hyderabad.

McDaniel, D. 1989. “Partial and Multiple Wh-Movement.” Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 7: 565–604.

Mey, de S. & L. Marácz. 1986. “On Question Sentences in Hungarian.” In Topic, Focus, and Configurationality ed. by W. Abraham & S. de Mey. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Mohanan, K.P. 1982. “Pronouns in Malayalam.” Studies in the Linguistic Sciences 11(2).

——— . 1984. “Operator Binding and the Path Containment Condition.” Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 2: 357–396.

Ndayiragije, J. 1999. “Checking Economy.” Linguistic Inquiry 30: 399–444.

Ortiz de Urbina, J. 1990. “Operator Feature Percolation and Clausal Pied-Piping.” MIT Working Papers in Linguistics ed. by L. Cheng & H. Demirdash. 13.193–208.

Pesetsky, D. 1982. Paths and Categories. Doctoral dissertation, MIT.

Reinhart, T. 1993. “Wh-in-situ in the Framework of the Minimalist Program.” Ms., Tel Aviv University.

Richards, N. 1997. What Moves Where When in Which Language. Doctoral dissertation, MIT.

——— . 1999. “Featural Cyclicity and the Ordering of Multiple Specifiers.” In Working Minimalism, eds. S.D. Epstein & N. Hornstein. Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press.

Rizzi, L. 1997. “The Fine Structure of the Left Periphery.” In Elements of Grammar. Handbook of Generative Syntax ed. by L. Haegeman. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Rudin, C. 1988. “On Multiple Questions and Multiple Wh-Fronting.” Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 6: 445–501.

Saito, M. 1989. “Crossing and WH-Q Binding.” Talk given at Ohio State University.

Simpson, A. & T. Bhattacharya. 2003. “Obligatory Overt Wh-Movement in a Wh-in-situ Language.” Linguistic Inquiry 34: 1, 127–142.

Srivastav, V. 1989. “Hindi WH and Pleonastic Operators.” NELS 20. Department of Linguistics, University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

——— . 1991a. WH Dependencies in Hindi and the Theory of Grammar. Doctoral dissertation, Cornell University.

——— . 1991b. “Subjacency Effects at LF: The Case of Hindi WH.” Linguistic Inquiry 22: 762–769.

Szabolcsi, A. 1983. “The Possessor That Ran Away from Home.” The Linguistic Review 3: 89–102.

Tuller, L. 1992. “The Syntax of Postverbal Focus Constructions in Chadic.” Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 10: 303–334.

Watanabe, A. 1992. “Subjacency and S-structure Movement of Wh-in-situ.” Journal of East Asian Linguistics 1: 1–37.