R. Amritavalli

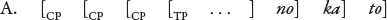

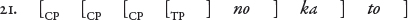

Saito (2011) proposes a layered structure for the right periphery of the Japanese clause that hosts complementizers, with no, ka and to occurring in that order to introduce (respectively) propositions, questions, and ‘paraphrases of quotes’ or ‘reports of direct discourse’ (op.cit:57):*

Comparing (A) with the left periphery of Rizzi (1997) in (B) below, Saito suggests that “if ka is Force and no is Finite, Japanese is identical to Italian except for the presence of to.”

This paper investigates the right periphery of the Kannada clause. The complementizer anta introduces propositions as well as paraphrases of quotes.1 However, proposition-introducing anta differs from Japanese no in resisting case; the parallel to no is with a nominal complementizer annoo-du that requires case, and occurs presumably in the innermost C layer.

The position of anta in the layered C structure becomes clearer when we look at interrogative complements. The yes-no question particle is -aa. A sequence aa-anta obtains in embedded polar questions (in embedded constituent questions, -aa is not pronounced), suggesting that anta occurs outside the interrogative complementizer layer headed by -aa. Interrogative complements may semantically be questions or propositions (Saito op. cit., McCloskey 2006). Japanese to, when it co-occurs with ka, is restricted to question interrogative complements; but anta introduces propositional interrogative complements as well. Thus anta seems to occur above the interrogative complementizer layer in both its propositional and quotative functions.

A second interrogative complementizer in Kannada is the disjunction marker -oo (Amritavalli 2003:11). -oo freely introduces question interrogative complements, but it introduces propositional interrogative complements only in the presence of a matrix negation, imperative, modal, or (more marginally) question. These licensing conditions for -oo are precisely those for embedded T-to-C in Irish English (McCloskey 2006), which occurs freely in question interrogative complements, but requires matrix non-veridicality operators in propositional interrogative complements. McCloskey hypothesizes that embedded T-to-C is licensed by a layered CP structure C1-C2; and suggests that C1 may be Force in the Rizzi left periphery, and C2, Focus. Looking at the co-occurrence possibilities of anta and -oo in question and propositional interrogative complements, however, I suggest that McCloskey’s C2 may be Force, and C1 the outermost layer in the Saito structure (A) above.

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 considers finite propositional complements, and shows that anta introduces direct as well as indirect discourse, but resists case. The latter point is developed in the context of an argument for purely “nominal” clauses in Kannada. Section 3 discusses interrogative complements. In 3.1, we see that anta introduces question and propositional interrogative complements. Sections 3.2–3.3 introduce -oo complementation, and the parallelism with Irish T-to-C. The location of anta and -oo in the dual C system of McCloskey is explored in 3.4-3.6. Section 4 is the conclusion.

The Dravidian complementizers that introduce finite embedded clauses are known as ‘quotatives’ in the literature. In Kannada, the complementizer anta is a frozen present participle (ann-utta, ‘saying’) of the verb ‘say,’ ann-.2

Like Japanese to, Kannada anta can introduce direct as well as indirect speech complements. This is a more general property of Dravidian quotative complementizers (Jayaseelan 1991).3 In the paired examples below, the complement subject is a pronoun coreferential with the matrix subject. The coreferential subject in the (a) examples is a first person pronoun, consistent with direct speech. In the (b) examples it is a third person or reflexive pronoun, consistent with reported speech.

Example (2) shows a second contrast: the verb in the direct speech complement is in the imperative, whereas the indirect speech complement has a modal of obligation. These data are consistent with anta as complementizer for ‘paraphrases of quotes’ (Plann 1982) or ‘reports of direct discourse’ (Lahiri 1991), like Japanese to. However, anta also introduces propositions.

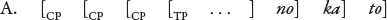

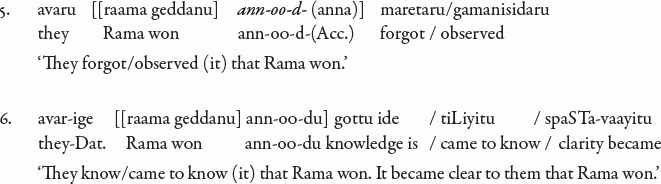

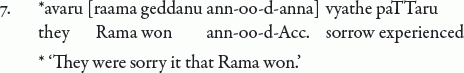

Factive predicates like mare ‘forget,’ gamanisu ‘observe,’ vyathe paDu ‘be sorry,’ gottu iru ‘know,’ tiLi ‘come to know,’ and spaSTavaagu ‘become clear’ take anta complements. The first three predicates take nominative subjects; the last three take “dative subjects.”

Among the predicates in (3), not all allow a DP object corresponding to the clausal argument. (The “dative subject” predicates in (4) all allow a nominative DP argument corresponding to the clausal argument.) Thus mare ‘forget’ can take a DP object (naanu idanna marete ‘I forgot this’), but vyathe paDu ‘be sorry’ cannot (*naanu idanna vyathe paTTe ‘*I was sorry this’). The predicates that allow a DP argument allow a nominal complementizer ann-oo-du to introduce the complement clause, and to be case-marked as appropriate (accusative in (5), nominative in (6)).

In (7), the ann-oo-du clause is not licit, as the predicate ‘be sorry’ does not permit a DP object.

Ann-oo-du (annuv-a-du in careful speech) is a relativized form ann-oo (annuv-a) of the verb ann- ‘say,’ with a (pro)nominal [3sg.n.] head or agreement matrix -du. Ann-oo can introduce nominal complements to N like maatu ‘word,’ suddi ‘news’ (… annoo suddi, ‘the news that …’).4 Anta and ann-oo-du clauses thus have the structures (8a, 8b).5

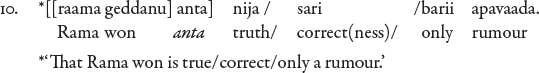

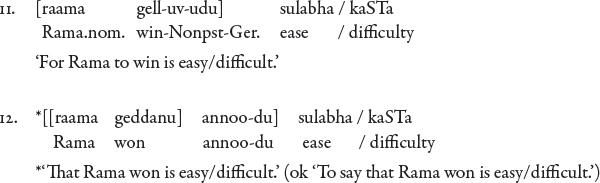

We have seen that anta clauses occur where a DP is not licensed. In fact, anta clauses are prohibited where only a DP is licensed; i.e. they resist case (Stowell 1981). Predicates such as nija ‘true (lit. ‘truth’), suLLu ‘false(hood),’ sari ‘correct(ness)’, tappu ‘wrong (n.),’ apavaada ‘rumour’ are nominal in Kannada.6 Their CP subjects are finite annoo-du clauses.

Anta clauses cannot occur as the subject of these predicates.

The annoo-du complement in (9) is a CP, not a gerund (a nonfinite clause). Predicates that allow only gerundive subjects (sulabha ‘easy (lit. ‘ease),’ kaSTa ‘difficult (lit. ‘difficulty),’ do not allow annoo-du clauses as subjects.7

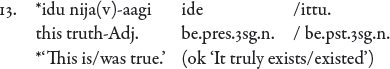

Note that (9) is a verbless copular clause, a “nominal” clause.8 A clause with an overt copula has its predicate marked by -aagi, an adjective/adverb marker. Factive predicates like nija ‘truth’ do not occur in such clauses (13), perhaps because they can signify only stage-level predication.9

Again, predicates like sari ‘correct(ness)’ are interpreted as stage-level predicates when the copula is overt (14). They do not admit factive CP subjects when the copula is overt (15).

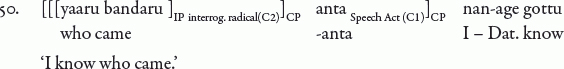

The complementizer anta introduces question complements as well: yes-no questions, and wh-questions. The yes-no question particle is aa. It occurs on the verb, following agreement morphology (16). Yes-no questions can be introduced as complements by anta (17).

Anta also introduces wh- complements (-aa does not surface in wh- questions).

If the question morpheme is also the question complementizer, i.e. if -aa corresponds to Japanese ka, we may assume that the question complementizer is unpronounced in (18):

Saito shows that in Japanese the sequence of complementizers corresponding to Kannada aa-anta, namely ka-to, occurs only if the interrogative complement is subcategorized by a verb of saying or thinking. That is, to co-occurs with the question complement of verbs like ask, scream, or think, but not with the complement to verbs like investigate, understand, or don’t know. Saito points out that the latter verbs subcategorize propositional interrogative complements. He concludes that Japanese to is a complementizer for ‘paraphrases of quotes’ or ‘reports of direct discourse,’ but not for propositions. Recall that the complementizer for propositions is no; cf. (A) above, repeated below as (21).

We have seen that anta in Kannada introduces propositions (such as factive complements). Then we may expect anta to occur not only with question complements to verbs of saying or thinking (keeL- ‘ask,’ vicaaris- ‘inquire’ in (22)), but in propositional interrogative complements to verbs like kaNDu hiDi ‘discover,’ tanikhe maaD- ‘investigate,’ tiLidukoLL- ‘find out,’ yoocis- ‘think about,’ gott (illa) ‘(don’t) know’ in (23-24).

These data argue that anta must always occur above the interrogative complementizer layer in (21). (This is consistent with the finding that when anta introduces propositions it resists case, unlike Japanese no.)

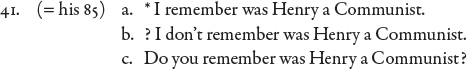

Amritavalli (2003:11) noted that the disjunction marker -oo functions as an interrogative complementizer in Kannada. I did not there distinguish question from propositional interrogative complements. Interrogative complements introduced by -oo, however, distinguish question interrogative complements from propositional interrogative complements in Kannada. We shall see that -oo freely introduces question interrogative complements; but it needs a matrix licensor (negation, imperative, modal, or, more marginally, question) to introduce propositional interrogative complements. Interestingly, Irish English (McCloskey 2006) allows embedded clause subject-auxiliary inversion (T-to-C movement) freely in question interrogative complements, but in propositional interrogative predicates, T-to-C occurs only under the set of matrix non-veridicality licensors mentioned above. There is then a remarkable parallel between the licensing of embedded T-to-C in Irish English, and Kannada -oo interrogative complements.

Yes-no question complements (25) and wh-question complements (26) can be introduced by -oo. (The disjunct of the question is shown in parentheses.)

Notice that -oo co-occurs with anta in (26). The oo-anta complementizer sequence is overt in constituent questions, unlike the putative -aa -anta sequence in (18/20). A second difference between -oo-anta and - aa -anta is that a wh-word can scope out of an -aa -anta constituent question complement (27, 29), but it cannot scope out of an -oo-anta question complement (28, 30). Compare the pairs (27-28, 29-30).

This suggests that -oo is a question complementizer that precisely delimits the scope of an embedded question. It need not occur in the same clause as the wh- gap. In (30), the wh-gap is in the most deeply embedded clause; -oo occurs in the middle clause. The wh- word scopes out of its own clause up to the -oo clause, but it cannot scope beyond that clause. In (29), however, the wh- word has matrix scope. Thus aa -anta complements may be ambiguous between a matrix and an embedded question reading, cf. (31):

Since -aa need not always scope below anta, we may infer that it can occur either as an interrogative complementizer or as a question operator in the matrix clause. In contrast, -oo in constituent questions is required to take embedded scope, below anta.10

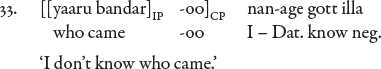

In (33), -oo introduces the complement to gott illa ‘don’t know.’ (34) shows this complement introduced by anta.

We see that in propositional interrogative complements, unlike in question interrogative complements, -oo and anta do not co-occur. They cannot co-occur (35):

In propositional interrogative complements, again, -oo needs licensing. In (33), -oo is licensed by the negation of gottu ‘know’ in the matrix clause. The affirmative predicate gottu ‘know’ does not allow an -oo complement (36), but it allows an anta complement (37).

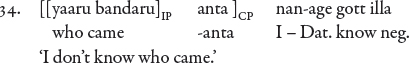

Negation is not the only licensor for -oo in propositional interrogative complements to predicates like kaNDu hiDi ‘discover, find out,’ tanikhe maaD- ‘investigate,’ tiLidukoLL- ‘find out,’ or yoocis- ‘think about.’ Other licensors are matrix imperative mood, modals, and (somewhat more marginally) questions.

These licensing contexts for -oo complements are similar to those for embedded T-to-C in Irish English, which occurs freely with question interrogative predicates such as wonder, but not (at first sight) with propositional interrogative predicates such as know. (The latter are termed ‘resolutive predicates’ by McCloskey (2006).) The examples below are from McCloskey:11

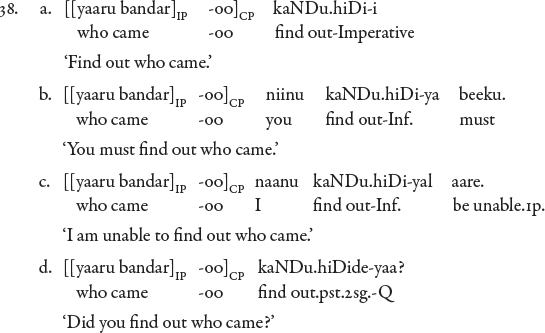

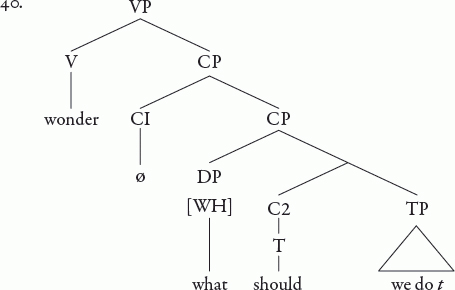

McCloskey argues that T-to-C is possible only if target C is not lexically selected. Thus it occurs in matrix CP, or in adjunct CP (like conditionals), which are not selected at all. Or, he suggests, it is possible in a CP selected by a functional rather than a lexical head. Observing that in V2 languages, a C that itself takes a CP complement makes embedded V2 possible, he postulates a double layer of CP structure for predicates like wonder. In (40) (= his (68)), wonder selects the ‘higher’ interrogative head C1, which in turn selects the ‘lower’ interrogative head C2.12

Resolutive predicate complements lack the additional, protective layer of complementation. Complements to resolutive predicates project only the lower C, an “interrogative radical”, and so disallow T-to-C. However, the licensing capabilities of resolutive predicates can be “expanded” by negation, or questioning, or imperative mood in the matrix clause, and indeed, by “any number of devices which determine nonveridical contexts (in the sense of Giannakidou 1997):”

McCloskey argues that the matrix licensors have the semantic effect of turning the complement into a question act, in that the issue in embedded complement is now left unresolved. This is an interesting point that he develops at some length about the ‘larger’ (C1-C2) complement: it represents a speech act, and the higher C projection is an “embedded illocutionary force indicator.” Thus the matrix non-veridicality licensors legitimize a question act, which syntactically licenses the double C structure, where C1 is a question act head that selects C2.

Notice that on McCloskey’s analysis, the difference between question interrogative complements and propositional interrogative complements is semantically as well as syntactically neutralized when the latter carry non-veridical operators. But if so, we should expect, in Kannada, -oo-anta complements to simply be legitimized in propositional interrogative complements, under the appropriate matrix licensing conditions. Contrary to this expectation, a syntactic difference persists: -oo cannot co-occur with anta in propositional complements. This suggests that in propositional interrogative complements, the disjunction head -oo resides in the larger C, C1, whereas in question interrogative complements -oo occurs in C2, and anta occurs in C1, yielding the oo-anta sequence in them.

One argument that supports the evidence from surface order for locating -oo in C2 in question complements is that they occur where they are obviously lexically unselected by a matrix predicate. Recall that C2 is an unselected, lower, interrogative complement. Consider now the complement to the predicate ‘fear, be afraid’ in (42), clearly non-interrogative. (42) has an “interrogative” variant (43), with an -oo complement.

In (43), the -oo licenses a dummy wh- word yelli ‘where’ (note that wh- is not here a variable for a place). Thus -oo syntactically converts a propositional complement to ‘fear, be afraid’ into an interrogative complement. As far as I can judge, the dummy wh- word complement is restricted to speech acts of “apprehension;” it occurs with matrix predicates with the meaning of fear, such as bhaya or hedarike ‘fear.’ This suggests that in (43), the -oo complement is licensed by a C1 that represents a speech act of apprehension. This C1 head is lexically realized as anta. This is not surprising if anta is a quotative complementizer that occurs with verbs of saying or thinking.13

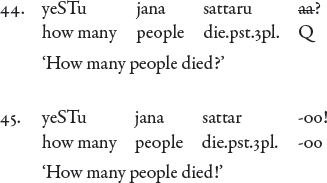

C1 in question interrogative complements is then not limited to a question act. Indeed, C1 may also express exclamation. Let us first note that a root wh- question (44), when suffixed with disjunctive -oo as in (45), has the force of an exclamation, or rhetorical question:

Let us say that in exclamations as in questions, a wh- phrase moves to a focus position. What differentiates exclamations is that they subordinate the wh-clause to an exclamatory speech act.

The exclamatory interpretation of a wh- …-oo sequence obtains also in embedded contexts. Consider the matrix predicate heeL-, ‘say, tell.’ When it takes an -oo-anta complement, the complement has exclamatory rather than interrogative force. Cf. the change in gloss for the verb ‘say’ from ‘reported’ to ‘lamented’ in (46) (=32 above):

To sum up, I have suggested that anta when it introduces question interrogative complements is the head of a Speech Act phrase, to be identified with C1 in the double CP structure of McCloskey (2006); its content includes Q(uestion), Exclamation and Apprehension. In the oo-anta sequence, -oo occupies C2.

The need for non-veridical matrix elements to license propositional interrogative -oo complements argues in favour of McCloskey’s double C structure for them. But the question arises why anta cannot co-occur with -oo in these complements.

I have suggested that in (47), -oo occurs in C1, where it is licensed by matrix negation.

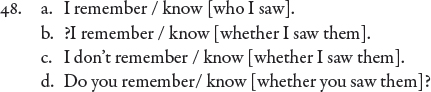

Let us look at parallel data from English, suggestive of which position – C1, or C2 – whether occurs at. In the now-familiar paradigm (48) below of resolutive predicates, in (48a), there is only what McCloskey calls an “interrogative radical,” a lower interrogative head C2 (as there are no matrix polarity licensors, C1 does not occur). Notice that this structure suffices to host a wh- or constituent question complement. What it does not license is the polar question complement (48b). The polar question complementizer whether needs licensing by matrix negation or questioning (48c-d); it requires a double C1-C2 structure, precisely as embedded T-to-C in Irish English and Kannada propositional -oo complements do.

We could treat whether in (48c-d) as the realization of the speech act Q that occurs in C1, where it is licensed by the matrix negation or question. I.e. the interrogative radical does not host the question operator in (48), although it suffices to host the moved wh-.14

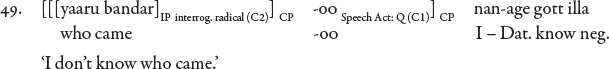

If -oo in propositional interrogative complements is a speech act head Q in C1, the failure of anta to co-occur with it naturally follows. In (49), -oo in C1 is licensed by the non-veridicality operators of the matrix clause, and it licenses the interrogative radical C2.

In the absence of non-veridicality matrix licensors, propositional complements must be introduced by anta (anta is actually indifferent to their presence). Thus in (50), anta must be in the Speech Act complementizer slot C1, and its complement an interrogative radical.

Rizzi’s (1997) articulation of the left periphery receives support in Saito (2011) and McCloskey (2006). Saito suggests that Japanese ka corresponds to Force, and no to Finite C; McCloskey, that C1 is Force, and C2 Focus. Saito posits to as an additional C for ‘paraphrases of quotes’ or ‘reports of direct discourse.’

Looking at Kannada, I have suggested that anta is like Japanese to, with the difference that it also introduces propositions. The co-occurrence or otherwise of -oo and anta in interrogative complements suggests that (i) anta is McCloskey’s C1, a speech act head that can co-occur with -oo; and that (ii) -oo can also be C1, in which case anta cannot occur. McCloskey’s C1 is thus not Force, but the third C identified by Saito. Wh- movement can target Focus in the absence of a Q in Force, in propositional interrogative complements and in exclamatives. These claims about the C-system are summarized in the table below (ignoring word order):

A number of questions remain about questions and disjunctions (see n.10 above). We have seen some differences between -aa and -oo in Kannada. If -oo is a question complementizer like whether rather than a question operator, we have a clue to a puzzle noted in Amritavalli (2003): apparent matrix wh-questions, when suffixed with -oo, are understood as indirect or embedded questions. Contrast the translations of (51) and (52):

If (51) has an overt C, an “embedded” reading for it might follow from whatever principle of the grammar ensures that root sentences do not have their C head pronounced (cf. Rizzi 2005 for some discussion). The intuition about the content of the ‘silent’ matrix predicate in (51) (understood as either a question predicate, or a non-veridical resolutive predicate) matches the licensing conditions for -oo in question and propositional interrogative complements.

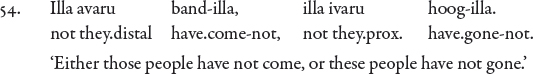

On the other hand, -oo can occur in the root clause in the absence of wh-. The primary observation in Amritavalli (2003) was that root disjunctions in Kannada are interpreted as alternative questions: root -oo is interpreted as whether, not either.15

A root declarative disjunction has to be licensed by an overt negative illa (the initial neg in (54), distinct from the sentence negator illa in sentence-final position). (In English declarative disjunction, there is a covert neg, reflected in the negative polarity of either.)

Declarative disjunction also occurs in the scope of modal operators of ability (can), genericity, etc. (Higginbotham 1991). The licensing conditions of interrogative -oo complements explicated in this paper are therefore consistent with the polarity properties of disjunction noted earlier.

* It has been a rich and rewarding experience to interact with Mamoru Saito over the years, and to be associated with the research group at Nanzan University. This paper is obviously inspired by Saito’s work; thanks also to James McCloskey for readily making available to me a soft copy of his insightful paper on Irish English, and to an anonymous reviewer for helpful suggestions.

1. Like Spanish que, said to be ambiguous in this respect (Saito, loc.cit.).

2. Anta has a formal counterpart endu, a past participle (‘having said’) of the verb enn-. The syntactic properties of the formal and informal complementizers are, to my knowledge, the same.

3. Sridhar (1990 [2007]:1) notes that direct speech is always marked by endu/anta. The complementizer is omissible only when the matrix verb is itself annu or ennu, the putative verbal source of the quotative complementizer.

4. Nominal complementation in Kannada thus supports Kayne’s (2010:175-6) suggestion that sentential complementation to nouns involves a relative clause structure.

5. I use the IP nomenclature rather than TP for Kannada, as finiteness is not identified with tense in this language (cf. Amritavalli and Jayaseelan 2005, and the discussion below on verbless copular (“nominal”) clauses). I retain the TP nomenclature when citing work that uses it.

6. Thus nija ‘truth’ occurs as an accusative object in (i), and with dative case (as an adverb) in (ii). (Dative case derives A (Adj./Adv.) from N in Kannada, cf. Amritavalli and Jayaseelan 2003.)

7. In English too, these predicates do not allow finite complements: *It was easy that Rama won.

8. Rapoport (1987) argues for verbless copular clauses or “nominal sentences” in Israeli Hebrew.

9. “(Copular) sentences with overt copula … sound awkward if used in the present tense without a locative or time expression (e.g. ii naDuve ‘these days’)…” (Sridhar 1990 [2007]: 82).

10. -oo occurs in matrix polar questions, where wh- is absent. Note the absence of wh+disjunction in the matrix clause in English: *Whether he came? (whether = wh+either).

Jayaseelan (2001, to appear) argues, from the semantics of questions, that the question operator is the disjunction operator; the polar question morpheme and the disjunction morpheme are reflexes of this operator. In Malayalam, both are pronounced -oo. In Kannada, the question morpheme -aa and the disjunction morpheme -oo differ: (i) -aa is covert in constituent questions, -oo is overt in embedded constituent questions; (ii) -aa allows wh- to scope out, -oo does not. Malayalam -oo does not limit the scope of wh- (Jayaseelan 2001); it appears to be ambiguous between Kannada -oo and -aa.

For a discussion of the exclamatory force of (32), see section 3.5.

11. McCloskey points out that this cut between two types of interrogative complements has long been recognized by semanticists: the interrogative complement to predicates like wonder is semantically a question, the interrogative complement to predicates like know is a proposition; the latter predicate allows that-complements in English, the former does not.

12. In the discussion that follows this example, McCloskey suggests that in a layered CP structure, C1 may be identified with Force in the Rizzi left periphery, and C2 with Focus.

13. In reporting thoughts, anta may countenance a rather loose relation between clauses, as in (i).

English that-complements to adjectival predicates: The mother was happy / surprised that the son was coming, similarly yield a causal inference.

14. If wh- movement targets Focus, on a widely prevalent view (including Beninca (2004), cited by McCloskey), this would support the identification of C2 with Focus.

15. Matrix -oo polar questions have an air of challenge (“I ask you: [polar question]?”) absent in matrix -aa polar questions. This is consistent with the claim here that -oo is a speech act head.

References

Amritavalli, R (2003) “Question and Negative Polarity in the Disjunction Phrase,” Syntax 6.1, 1–18.

Amritavalli, R. and K. A. Jayaseelan (2003) “The Genesis of Syntactic Categories and Parametric Variation,” Generative Grammar in a Broader Perspective: Proceedings of the 4th GLOW in Asia 2003, ed. by Hang-Jin Yoon, 19–41, Hankook, KGGC and Seoul National University.

Amritavalli, R. and K. A. Jayaseelan (2005) “Finiteness and Negation in Dravidian,” The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Syntax, ed. by Guglielmo Cinque and Richard S. Kayne, 178–220, Oxford University Press, New York.

Beninca, Paola (2004) “A detailed map of the left periphery in medieval romance,” ms., University of Padua, Presented at GURT 2004, Georgetown University, March 26, 2004.

Higginbotham, James (1991) “Either/or,” Proceedings of NELS 21, ed. by T. Sherer, 143–155, Amherst, Mass., GLSA publications.

Jayaseelan, K. A. (1991) “Review article: The Serial Verb Formation in Dravidian Languages by Sanford S. Steever, Motilal Banarsidass, Delhi, 1987,” Linguistics 29, 543–548.

Jayaseelan, K. A. (2001) “Questions and Question-word Incorporating Quantifiers in Malayalam,” Syntax 4.2, 63–93.

Jayaseelan, K. A. (to appear) “Question Particles and Disjunction,” Linguistic Analysis 38, 1–2.

Kayne, R. S. (2010) “Antisymmetry and the Lexicon,” Comparisons and Contrasts by R. S. Kayne, Chapter 9, 165–189, Oxford University Press, New York.

Lahiri, U. (1991) Embedded Interrogatives and Predicates that Embed Them, Doctoral dissertation, MIT.

McCloskey, J. (2006) “Questions and Questioning in a Local English,” Crosslinguistic Research in Syntax and Semantics: Negation, Tense and Clausal Architecture, ed. by R. Zanuttini, H. Campos, E. Herzburger and P. H. Portner, 87–126, Georgetown University Press, Georgetown.

Plann, S. (1982) “Indirect Questions in Spanish,” Linguistic Inquiry 13, 297–312.

Rapoport, Tova R. (1987) Copular, nominal and small clauses: a study of Israeli Hebrew. Doctoral dissertation, MIT.

Rizzi, Luigi (2005) “Phase theory and the privilege of the root,” Organizing Grammar: Studies in Honor of Henk van Riemsdijk, ed. by H. Broekhuis, N. Corver, R. Huybregts and J. Koster, 529–-537, Mouton, Berlin.

Rizzi, Luigi (1997) “The fine structure of the left periphery,” Elements of Grammar, ed. by L. Haegeman, 281–337, Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht.

Saito, Mamoru (2011) “Sentence Types and the Japanese Right Periphery,” Research in Comparative Syntax on Movement and Noun Phrase Structure, 55–77, Interim research report, Nanzan University, Nagoya.

Sridhar, S. N. (1990 [2007]) Kannada, Routledge, New York. [Reprinted as Modern Kannada Grammar, Manohar, New Delhi.]

Stowell, Tim (1981) Origins of Phrase Structure, Doctoral dissertation, MIT.