R. Amritavalli

This investigation of clause structure in Kannada (a Dravidian language of South India) shows that:*

(a) Finiteness cannot be equated with Tense. Kannada lacks Tense, with finiteness residing in a Mood P whose head is one of the elements Indicative (Agr), Modal or Neg.

(b) What is interpreted as Tense is an Aspect in the domain of a finite head. Perfect aspect is interpreted as past tense, imperfect aspect as non-past tense.

(c) Aspect is present in nonfinite verb forms (the gerund and the infinitive). In English as in Kannada, bare infinitives and dative case-marked infinitives (or ‘for-to’ infinitives) differ in aspect: bare infinitives carry perfect aspect, dative case-marked infinitives carry unrealized aspect.

Finite clauses in Kannada fall into the following superficial subtypes, with the superficial structure indicated:

If we take finiteness to be what allows a clause to ‘stand alone’ as a root clause, it is a common current assumption (e.g. Shlonsky 1997: 3, 55) that finiteness is synonymous with Tense.1 Clauses of type (I) above—that is, ‘nominal clauses’ or copular clauses with no overt verb—are prima facie counterexamples to this assumption.

Nominal clauses occur also in the present tense in Hebrew. For Hebrew, analyses differ on whether these clauses are indeed tenseless. Rapoport (1987) considers them so, offering a choice of structure of a matrix small clause and a tenseless full clause headed by Agr in Infl. Shlonsky (1997), however, assimilates Hebrew nominal clauses into regular clause structure by postulating a null present tense auxiliary with abstract tense and agreement features.

Kannada copular sentences would appear to be a little more recalcitrant to a similar assimilation effort.2 But my focus in this paper is not on copular sentences. I concern myself with negative sentences in Kannada (clauses of type II [ii]) that are the counterparts of affirmative sentences with verbs fully inflected for what looks like Tense and Agreement morphology (clauses of type II [i]). In standard accounts of clause structure, affirmative and negative sentences differ primarily in the presence of the Neg P. The Neg P is simply an additional functional projection optionally introduced into the functional architecture of the non-negative clause. (Modals, too, are similarly ‘added into’ the functional frame of the basic clause.) In Kannada, however, the negatives of the simplest present and past tense sentences look dramatically different from the affirmatives, as a cursory comparison of the schemas II (i) and II (ii) shows.

I present here an analysis of negative sentences in Kannada which leads me to deduce three claims:

(a) Finiteness cannot be equated with Tense. Kannada appears to lack Tense, with finiteness residing in an XP (perhaps a Mood P) whose head X is one of the elements Indicative (Agr), Modal or Neg.

(b) Tense being absent, what is interpreted as Tense is an Aspect in the domain of the finite head X. Perfect aspect is interpreted as past tense, non-perfect aspect as non-past tense.

(c) Aspect is present not merely overtly in the standard ‘perfect’ (-en) and ‘progressive’ (-ing) verb forms, but also covertly in nonfinite verb forms, e.g. in the gerund, and, crucially, in the infinitive forms. ‘Bare’ infinitives and ‘for-to’ infinitives (or dative case-marked infinitives) appear to consistently differ in their aspectual specifications in two such genetically and areally unrelated languages as Kannada, and English: ‘bare’ infinitives carry perfect aspect, ‘for-to’ (or dative case-marked) infinitives carry unrealized aspect.

A consequence of the first and fundamental claim, delinking Tense from finiteness, is that it explains the simultaneous existence in Kannada (as in Hebrew) of two major finite clause types—with and without a verb. For theories according Tense a pivotal role in clause structure, with Tense carried by the verb, ‘nominal clauses’ are an anomaly, to be explained away by assimilating their structure to that of verbal clauses.

A consideration of ‘nominal clauses’ in their own right suggests that they are ‘built around’ Agr (Rapoport 1987; Amritavalli 1997). We are now arguing that in Kannada, affirmative ‘verbal clauses’ are also ‘built around’ Agr, and not Tense. This argument is entirely due to properties intrinsic to ‘verbal clauses’; its rationale is to explain the superficial variety of clause types exhibited in affirmative, negative and modal sentences in terms of a single clause structure. What is interesting, then, is that a claim motivated by the analysis of Kannada clauses of subtype II generalizes to and explains clauses of subtype I.3

Consider the affirmative sentences 1a and 1b. The verbs in them are standardly analyzed as having the tense and agreement markers identified in the glosses.

Consider now the negative counterparts 2a, 2b of 1a, 1b.

We note that (i) the verbs in 2a, 2b are not inflected for tense and agreement; (i) they occur in a gerundive or infinitive form, apparently non-tensed forms.

Yet tense cannot be absent in (2a, b). First, the choice of the nonfinite verb form reflects a (covert) tense. Gerund plus illa negates a verb with non-past tense, while infinitive plus illa negates the past tense. (This pattern of negation is a feature of the modern language. An earlier stage had a negative infix on the verb in main clauses [V + Neg + Agr], giving rise to the ‘negative conjugation’ or ‘mood’. In this (now absent) conjugation, tense was not merely superficially absent; there was also no indication of tense in the interpretation, i.e. negative verb forms in the ‘negative conjugation’ were apparently free with respect to the interpretation of Tense.)4

Secondly (and strikingly), the Neg illa is not licensed in genuinely non-tensed (= nonfinite) clauses, i.e., in non-root gerundive and infinitive complement clauses. This is shown by 3–4: the a sentences cannot be negated by adding illa (the b sentences).

In other words, what we have in 2a and 2b appear to be ‘matrix’ infinitives or gerunds.5

The facts presented above raise a couple of fundamental questions about the functional architecture of the clause. Given that we do not expect radical differences in clause structure between affirmative and negative sentences, the questions to answer are:

(a) What happens to tense (and agreement) in 2a, 2b?

(b) How is the nonfinite verb form selected in 2a, 2b, depending on the tense to be negated?

The intuitive answer to the first question is that tense is in some fashion ‘absorbed’ by the negative element illa. The phenomenon of Tense and Neg ‘going together’ is attested even in English, and is widespread enough to be encoded by Laka (1990) into the pre-Minimalist s-structure condition TCC (Tense C-command). We might execute this intuition by giving illa a strong tense feature to check, assuming very ‘surfacy’ structures like 5a and 5b for affirmative and negative sentences:

Tense does not appear on the surface in 5b (we may say) because illa is morphologically ‘defective’, and hence does not manifest tense (and agreement) overtly. (illa is in fact historically a ‘defective verb’ of negative existence.)

But the more interesting question is, how does the tense of the negated sentence get ‘read off’ the nonfinite morphology on the main verb? Assuming a covert tense feature located in the negative, this must be the result of a ‘match’ between that tense feature and the nonfinite morphology. There exist mechanisms in the theory to achieve such a ‘match’, such as agreement between a tense feature and the nonfinite verb, or selection of an appropriate complement type by the tense feature. Either way, there remains the central question: What makes the ‘match’ (of non-past tense with gerundive morphology, and past tense with infinitival morphology) non-arbitrary, and therefore learnable?

I shall argue that the tense-interpretation of the Kannada negative is demonstrably non-arbitrary when the aspectual specifications of infinitives and gerunds are taken into account. I shall show, moreover, that the aspectual specifications of infinitives are more complex than currently recognized, and that careful reanalyses may well reveal such aspectual specifications to be language-independent.

Let us begin by considering gerunds and infinitives in their more familiar position of complement clauses. We recall here Stowell’s (1982) proposal that infinitives carry ‘unrealized’ tense in COMP, whereas gerunds, lacking both a COMP and a tense operator, are simply transparent or ‘completely malleable’ on the semantics of the matrix verb.6

Now neither of these observations about infinitives and gerunds sits comfortably with our data. If gerunds have no tense operator and are ‘completely malleable to the semantics of the governing verb’, we expect the gerund in the Kannada negative to occur indifferently in either tense, past or non-past, with the appropriate interpretation (taking the ‘governing verb’ here to be Neg + Tense specified as [+/− past]). That is not the case, however; the gerund occurs only in the non-past tense.

Worse is the case of infinitives. The Kannada negative sentence uses infinitival morphology to signal past tense, whereas the suggested tense specification of infinitives is ‘unrealized’, or for the future!

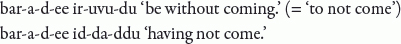

Let us consider the gerund more closely. If we look at the paradigm for gerunds in Kannada, we see immediately that the gerund must carry aspect. The gerund form V-uvudu that occurs in the negative sentence 2a is one of a paradigm of three forms, the other members of which are the ‘perfect gerund’ and the ‘negative gerund’. (Thus the V-uvudu gerund is the ‘imperfect’ gerund.) The three forms are illustrated below:

The incidence of perfect and imperfect forms of the gerund has sometimes led to the claim that in Dravidian, Tense is present in the gerundive and participial forms of the verb. This is because (as we shall see) the putative tense morphemes in Kannada are in fact aspect morphemes. Thus notice the vowel u in the imperfect gerund that parallels the vowel in the putative non-past tense morpheme utt in 1a: and the consonant d in the perfect gerund identical to the putative past tense morpheme d in 1b.

Note, however, the incidence in the gerund paradigm of the negative gerund form ba-a-r-addu. This form exhibits a negative infix a in the verb bar-. The negative infix is a survivor from an erstwhile ‘negative conjugation’; and the negative infixed verb currently occurs only in nonfinite contexts (cf. note 5). (As shown in 3b and 4b, the Neg illa is barred from such contexts.) This form, moreover, is unspecified for tense, as was the erstwhile ‘negatively conjugated’ finite verb.7 Thus the negative gerund is not a tensed form; and by extension, nor are the other gerund forms in the paradigm 6 tensed. The three gerunds in 6 are all nonfinite, but must be specified for aspect, taking negation to be an instantiation of aspect here.

We now see that in 2a. it is the non-perfect gerund that must ‘match’ with a putative tense feature [non-past], absorbed by illa. It follows that in 2b, for the infinitive to similarly ‘match’ with the hidden tense feature [past], the infinitive must (pace Stowell) be specified for perfect aspect.

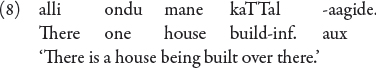

There is indeed a supporting piece of language-internal evidence that this is so: namely, that the Kannada passive auxiliary aag- ‘happen’ takes as its complement a verb in the infinitive.

Consider the comparable fact from English: the verb form selected by the passive auxiliary is the perfect or -en form. If this selection of a perfect is a principled fact about passives in general (owing perhaps to their ‘stative’ interpretation, and linking stativity with perfectivity), it is possible to draw the inference that the Kannada infinitive is in this aspect parallel to the perfect form of the English verb.

There is, however, a complication. Within Kannada itself, exactly as in English, there exist both purposive infinitives, and infinitival complements to verbs like try, which must have an ‘unrealized’ interpretation. Compare example 9a—which is a slightly modified version of example 4a given earlier—with the purposive 9b:

Thus Stowell’s facts, and his analysis, cannot easily be dismissed, even for Kannada.

The solution to the puzzle is to recognize that there are two types of infinitives, often confused, which have opposite aspectual specifications. In Kannada, these are the dative case-marked infinitive and the ‘bare’ infinitive. In English, these are the ‘for-to’ infinitive and the ‘bare’ infinitive.

Considering first Kannada, what we have so far cited as the infinitive form in 2b and 4a, V-alu, is indistinguishable from the ‘bare’ form of the infinitive. However, Kannada also has a dative case-marked infinitive. The confounding factor is that this dative case is often dropped; but with the benefit of hindsight, we may sort out the data.

Let us take first examples like 4a or 9: infinitival complements to verbs like try, and purposive complements, both of which have the ‘unrealized’ interpretation. The form of the verb we have cited in 4a and in 9 is (to repeat) the caseless infinitive; and this is indeed the standard, literary citation form for the verb in such sentences. However, the same standard dialect allows this infinitive on carry an overt dative case, especially in the spoken language. Thus 4a (repeated as 10a) has the variant 10b:

In my own spoken language, again the standard (Bangalore–Mysore) dialect, there is an even more revealing difference between the bare infinitive and the dative case-marked infinitive. The bare infinitive has the expected form V-alu. Whereas the case-marked infinitive is actually realized as a dative case on the gerund:

Significantly, the truly ‘bare’ infinitive, which (we argue) occurs in the past tense negative sentence 2b, and as a complement to the passive auxiliary 8, can neither be optionally case-marked, nor (in my dialect) substituted by a gerund, case-marked or otherwise.8,9

Coming now to English, notice that Stowell in ‘The Tense of Infinitives’ actually deals only with ‘for-to’ infinitives in English. Let us then investigate the tense of the bare infinitive in English.

The English bare infinitive, indistinguishable from a ‘bare’ or simply tenseless verb, occurs as a complement to perception verbs. Most of these verbs also take ing or gerundive complements. Akmajian (1977) credits to Emonds (1972) the following observation about the semantics of these two types of complements: the gerundive signifies an ‘incompleted’ [sic] action, where the infinitive signifies a completed one:

Akmajian adds that the same distinction holds for certain nonperception verbs which take both kinds of complements:

He observes that ‘the semantic distinction between incompleted and completed action is not restricted to perception verb contexts, but seems rather to be a function of a more general structural distinction between “gerundive” and “infinitive” verb phrase complements.’10

Akmajian does not speculate on what this ‘more general structural distinction’ might be. I suggest that it is a distinction of Aspect. What Stowell calls the Tense of infinitives is actually the Aspect of infinitives.

Locating the distinction in Aspect gives us the required distinction between ‘for-to’ infinitives and bare infinitives, along the values unrealized and perfect. Notice that it is very difficult to claim that bare infinitives have a tense operator: they occur in ‘small clauses’, which lack the functional baggage of full clauses. In the selection of the bare infinitive by the passive auxiliary in Kannada too, it seems to be Aspect that is the operative factor.

Again, this relocation allows us to group together and compare the ‘tense’ specifications of the gerund vis-à-vis the bare infinitive in the Kannada negative. We recall that Stowell argues against Tense in gerunds: gerunds lack a COMP, and if Tense is in COMP, gerunds cannot have Tense. But Aspect is a ‘content’ category, a property often intrinsic to verbs as part of their semantic specification, so it seems natural to project an Aspect Phrase whenever a Verb Phrase is projected.11

The distinction attempted here between the bare infinitive and the ‘for-to’ infinitive in English is confounded by the fact that a subsection of what we call ‘for-to’ infinitives are commonly treated as to-infinitives without for. There is, however, evidence the ‘unrealized’ interpretation of the so-called to-infinitive is attributable to the element for, rather than to (Jayaseelan 1987; Stowell 1982). If so, the parallel to be drawn is between dative case in Kannada and for in English, or perhaps the for-to complex.12

A second problem is that bare infinitives in English appear to ‘turn into’ to-infinitives when, for example, the complement of a perception verb is passivized:

There are two facts to note. First, the apparent convertibility holds only one way: bare infinitives turn into to-infinitives, but to-infinitives do not turn into bare infinitives.

Second, to appears in the absence of a lexical subject for the infinitive (disregarding for the moment the ecm contexts). Thus, it occurs in infinitives with PRO subjects, and in bare infinitives with an NP-trace subject 16b; but it does not occur in bare infinitives with wh-trace subjects (which we take to be case-marked variables), see example 16c:

These facts suggest that the presence or absence of to may be attributable to case theory. Suppose infinitive verbs have a ‘weak’ case to assign to a subject, and that to is actually a reflex of an unassigned subject case, just as passive morphology is a reflex of object case absorption. Then in 16a, the verb assigns a ‘weak’ case to the subject, in addition to or in conjunction with a case received by the subject across the small clause boundary. When the bare infinitive’s subject NP-moves under passivization 16b, this case has to be reabsorbed, and to appears. But when the same subject wh-moves 16c, there is no case absorption, and no appearance of to.

The case-assigning property of the bare infinitive is perhaps attributable to the incidence of perfect aspect in it (Jayaseelan [1984] notes that lexical subjects become possible in Malayalam adjuncts and in the English absolutive construction when have or be are present). We speculate that an infinitive verb specified for ‘unrealized’ aspect must obligatorily absorb its subject case; so that its lexical subject, if any, must then find an ‘external’ (to the IP) case assigner. Thus to always appears in ‘unrealized’ infinitives; and the suggested link between the realization of aspect and case explains why for must occur, and for-to function here as a unitary ‘complex’.

As for the to in ecm contexts, its appearance is consistent with the account of the infinitive verb absorbing its own case, if the complement subject here gets its case not in its own clause, but in the matrix clause’s AgrO projection (Lasnik and Saito 1991). The absence of the ‘unrealized’ reading for these clauses is due to the impossibility of for in these contexts.13,14

We have accounted for the apparent ‘match’ in 2a, 2b between a covert tense and the nonfinite morphology on the main verb in terms of the aspectual specifications of the bare infinitive and the gerund. Our data for this argument come from two very different languages, English and Kannada. This encourages the view that such aspectual specifications for clauses may be part of the initial state of the language faculty. This would explain the acquisition of negatives in Kannada, considering that the language-internal evidence—such as the difference of aspect between bare and case-marked infinitives—is meager at best.15

Our account began with the fiction of a covert matrix tense feature [past] or [non-past], ‘absorbed’ by Neg illa, that actually ‘selects’ the nonfinite complement. This is a fiction that we now propose to discard. For, the aspectual specifications here identified for the nonfinite complement seem to obtain independently of the feature content of the matrix tense. For example, in We shall see [Mary release pigeons on Republic day], the matrix tense is non-past or future, but the bare infinitive is interpreted as a completed action, that is, what we have identified is a phenomenon quite different from ‘anaphoric’ tense, such as obtains in tensed pseudorelative complements to perception verbs in Romance (where the tense of the pseudorelative must be the same as the tense of the matrix verb, cf. Guasti 1993: 148).

What seems to be required in 2a, 2b is a ‘dummy’ matrix tense with no substantive or content feature, that is, a finiteness head F, that sanctions the nonfinite clause in a matrix context, allowing its aspect to be interpreted as tense. The finiteness head, we suggest, is none other than the Neg illa.

A potential argument against this reduction is that the resulting structure]VP]NegP, or …]VP]AspP]NegP looks very different from what appeared to be a reasonable structure for affirmative clauses in Kannada: …]VP]TP]AgrP. But I shall show below that affirmative sentences in Kannada actually have the structure 17, quite unlike their surface appearance: (17).

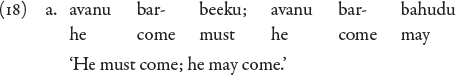

Sentences with Modals, moreover, fall naturally into the proposed structural schema. Like negatives, they surface with neither tense or agreement (the sole exception is the Modal (l) aar-, a Modal of inability, which inflects for agreement), taking a bare infinitive complement (cf. 18a).

The verb form in 18a looks like a stem; but it is a (bare) infinitival, as we see when the emphatic morphemes ee or uu attach to the verb. The consonant l of the infinitive now surfaces.

Modals and Neg illa are in complementary distribution in Kannada. Instead of analytic modal + illa phrases, we have ‘negative modals’ such as baaradu (cf. 18c).

Thus modals induce a ‘matrix infinitive’.16

Let us therefore propose that Kannada has a Mood P which hosts a finiteness head F.17 Mood P as its complement an Aspect Phrase, which takes a VP complement. A superficial possibility is that the head F of Mood P is simply one of the elements Neg, Modal, or Agr. However, there are two facts to consider: one, that Agr on the one hand, and Neg and Modal on the other, pattern differently with respect to the type of aspectual complement they select. Agr selects verbs with standardly acknowledged progressive or perfective morphology, such as occur in non-complex clauses in the ‘compound’ tenses. Whereas Neg and Modal, by selecting infinitive or gerundive aspectual phrases, pattern with higher predicates that select complement clauses; they behave as if they are ‘outside’ the IP projection, in some sense.

Secondly, Agr is intuitively a very different type of element than Neg or Modal. Agr is not itself a ‘Mood,’ but a reflex of what is traditionally labeled Indicative mood. If we take Indicative mood to be the ‘absence’ of mood, as is sometimes suggested, this gives us the result that there must be a null head for Mood P when Agr is present. This gives us the structure 19, abstracting away from word order:

It may be that Mood P is actually part of CP rather than IP. Mood P, that is, may be the lowest element of a more fully articulated ‘Comp complex’ (Rizzi 1997).

I briefly summarize in this section an independent set of arguments against a category TENSE in affirmative sentences in Kannada, that is, sentences of type II (i), which have an overt verb marked for (what is standardly analyzed as) ‘tense’, and agreement. I show that derecognizing tense as a functional category in this language allows us to (a) treat as non-accidental the identicality of the tense morphemes with the progressive and the perfect aspectual morphemes; (b) explain a puzzle in the tense pattern of the ‘simple’ vis-à-vis the ‘compound’ tenses; and (c) explain a puzzle in the pattern of negation of the verb iru ‘to be’.

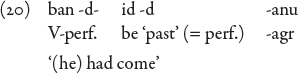

Taking up the first point, recall the ‘tense’ morphemes of Kannada identified at the outset in 1a and 1b: -utt- for non-past, and -d- for past. The aspect morphemes are (likewise) -utt- for progressive aspect, and -d- for perfect aspect. This is seen in ‘compound’ tenses, where (standardly) aspect and ‘tense’ are both taken to occur in the verb phrase. Consider thus the composition of the past perfect form of the verb bar-’come’. Aspect occurs on the main verb, and ‘tense’ on the auxiliary verb iru: note the occurrence of -d- on both verbs.

That is, compound tenses in Kannada appear to consist of a (serial verb-like) combination of main verb + aspect with iru + aspect.

The fact that the putative tense morphemes in Kannada have the same shape as the aspect morphemes might in isolation perhaps be dismissed as a curious coincidence. Given what we have said about the structure of negative clauses (and modal clauses), however, it invites us to postulate the clause structure 17 (elaborated in 19) for affirmative clauses in place of the more conventional clause structure.

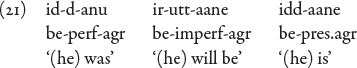

Turning to the second point, a complication in the ‘tense’ system of Kannada is that while verbs in general illustrate a two-valued system [perfect/imperfect], uniquely, the existential verb iru ‘to be’ is instantiated in three forms, with tense interpretations corresponding to ‘past’, ‘present’, and ‘future’.

In 21, the perfect form of iru is the regular form. But the regular imperfect morpheme here has only a future interpretation; and there is an additional, irregular form of iru, with no clearly isolable aspect morpheme, interpreted as the present (although the stem of the ‘present’ form in 21 resembles the perfect stem, this is merely a superficial resemblance: there is a clear differentiation of the two in the neuter forms ittu ‘(it) was’, ide ‘(it) is’).

The verb iru retains this idiosyncracy when it functions as an auxiliary verb in the ‘compound’ tenses (Recall that the compound tense is a serial verb-like combination of the main verb and its aspect with iru and its aspect.) Thus, there appear to be three compound tenses, although the language otherwise has a two-tense system. Below we illustrate the ‘perfect tenses’.

A similar paradigm obtains for the ‘progressive tenses’, with ‘past’, ‘future’, and ‘present progressive’ instantiated: bar-utt- id-d-anu, ‘(he) was coming’ (often used in the sense ‘he used to come’); bar-utt- ir-utt-aane, ‘(he) will be coming’ (commonly used for habitual or iterated activity, cf. the typical Indian English usage ‘He will be coming now and then’); bar-utt- idd-aane, ‘(he) is coming’.

How then should we analyze the ‘tense system’ of Kannada, keeping in mind, moreover, Chung and Timberlake’s observation (note 15) about tense in general being a two-valued system in the world’s languages?

Our proposal is that the third, ‘present tense’ that appears only in the verb iru ‘be’ is simply the ‘finiteness element’ that resides in the Mood P. Our claim is that the existential verb iru is the only verb that can occur with no aspectual specification, that is, with a null Aspect. Hence the finiteness element is allowed to surface in its ‘bare’ form, with no aspectual reading added in, only in the presence of this verb: whether as a main verb or as an auxiliary. We analyze the verb iddaane (which occurs, e.g., in sentences like deevaru iddaane ‘God is!’ or ‘God exists’), as consisting of the elements ir + øaspect + agreement.

In support of this analysis of iru, we adduce the following facts about the negation of iru. The two regular forms of iru, namely the perfect and the imperfect, are negated in the usual way, by combining a bare infinitive and a gerund form of iru (respectively) with illa: iral (u)-illa ‘was not’; iruvud(u)-illa ‘will not be’. Negation of the third, irregular or ‘present’ form of iru, however, consists in the apparent ‘replacement’ of iru by illa. (This is the third point, the puzzle in the pattern of negation of iru, mentioned in the beginning of this section.)

Such facts have given rise to a two-illa theory: a Neg illa, and a full verb illa, a negative existential verb (this analysis, proposed in Hany Babu 1996 for Malayalam, is assumed in Amritavalli 1997 for Kannada). The plausibility of the two-illa proposal lies in that diachronically, illa is indeed a verb of ‘negative existence’: that is, a form of the verb ir ‘to be’ in the now obsolete negative conjugation or mood (unlike other verbs in this conjugation, illa showed no person, number or gender agreement; it was ‘defective’).

This analysis is, however, not without problems. The putative verb of negative existence illa currently occurs only in one ‘tense’—the ‘present’ tense. (The regular forms of iru, it may be recalled, are negated in the regular way.) Unlike iru, illa lacks any other finite forms; and it ‘replaces’ iru only in the ‘present’ tense. The two-illa theory fails to explain either of these facts.

We propose that what looks like the main verb illa in 23b is actually the Neg illa. The main verb here is indeed iru, in its occurrence with a null aspect; and the structure of the verb in 23b is ir + øaspect + Neg (illa), parallel to that in 23a: ir + øaspect + agr. This should give us in 23b a surface form *ir-illa, or *id-illa or *il-illa (where id-, il- are variants of the stem of iru). And indeed, a reduplicated il- does show up in emphatic structures corresponding to 23b: illav-ee illa ‘is certainly not’. But in non-emphatic contexts there is probably a ‘double il-’ filter, which accounts for the single illa in 23b.

Our attempt at an adequate descriptive account of clause structure in Kannada has unveiled some issues of broader theoretical significance. Two foci of interest to emerge have been the constitution of finiteness, and the derivation of tense interpretations. We have shown that nonfinite verbs have aspectual specifications that, while not always obvious, are of sufficient generality to be theoretically interesting, demonstrating a parallel between ‘bare’ and case-marked infinitives in Kannada and English, two languages that are neither genetically nor areally related.

The fact that the interpretation of tense in Kannada is determined by the aspectual specification of the verb points to the need for a refinement in our understanding of the categories of Tense and Aspect, and their relation to Mood and finiteness. One understanding of this issue is that in Chung and Timberlake (1985: 202): ‘Tense locates the event in time. Aspect characterizes the internal temporal structure of the event. Mood describes the actuality of the event in terms such as possibility, necessity, or desirability.’ A question arises in what way this broad distinction between the internal temporal structure of an event, and its location in the real world (whether by anchoring it in time, or in terms of actuality), is reflected in the functional architecture of the clause. Current syntactic analyses place on Tense the burden of actualizing the event. Our suggestion is that Tense is an epiphenomenon, and that it is the specification of Mood that serves to confer finiteness and to locate a predication in the real world.

* Parts of this paper were presented at the GLOW Colloquium, CIEFL, Hyderabad in January 1998, and at the conference on the Syntax and Semantics of Tense and Mood Selection, University of Bergamo in July 1998. My thanks to the audiences at these two fora. The research reported here was undertaken during the year I was on sabbatical leave from the CIEFL.

1. ‘My starting point is that every clause, by definition contains a TP (tense phrase). I will argue … that the essential difference between a full clause and a small clause is that only the former contains a TP’ (Shlonsky 1997: 3); ‘… independent or full clauses must by definition contain a TP projection. Clauses lacking a TP are, to adapt a familiar terminology, “small clauses” and cannot occur, for example, as root sentences’ (ibid.: 55).

2. Two kinds of copular sentences are extant in Kannada, with and without the verb iru ‘be’.

Notice the element aagi in b. I have suggested (Amritavalli 1977: 48, n. 5; 1997) that aagi is a postpositional complementizer, like English ‘for’.

The verbless clause a is a finite clause. (It is introduced in embedded contexts by the regular complementizer anta, the counterpart of English ‘that’.) The other looks like a small clause (-aagi clause) complement to a verb iru ‘to be’. -aagi clauses occur (thus) in ‘object complement’ constructions (‘elect X president’), and with ‘raising’ verbs such as kaaN ‘seem’, tiLi ‘know, think’:

The Neg that appears in the verbless copular clause a, namely alla, is not the same element (namely illa) as in b. alla normally negates noun phrases but not clauses with verbs (Amritavalli 1997).

3. The properties of Agr in nominal clauses and verbal clauses are not identical: nominal Agr lacks the person feature.

4. Hence the emphasis in Kittel (1908: 332) on how ‘the modern dialect expresses clearly’ or ‘in a clear way’ the negations of particular tenses: ‘… forms like iruvadilla, baruvadilla, kaaNuvadilla, aaguvadilla, in the modern dialect, take the place of the simple negative to express the present tense of the negative in a clear way; kaLeyalilla, paDeyalilla, keeLalilla, sigalilla are used in the modern dialect to express clearly the past tense of the simple negative …’ (emphasis in the original).

Kittel’s clarity regarding the ‘match’ of current negative verb forms with the tenses in the affirmative (easily verifiable by tests with time adverbials) contrasts with the confusion in this regard in some later work (for pertinent remarks, see Amritavalli 1977; Hany Babu 1986).

5. Negation in non-root gerundive and infinitive clauses is by the negative infix -a- in the verb, a morpheme which goes back to the ‘negative conjugation’ mentioned earlier.

The problem of the ‘matrix gerund/infinitive’, noticed as a ‘prima facie surprising construction’ in Italian (Zanuttini 1991), is created by a set of assumptions. Gerundive or infinitival morphology is standardly taken to be a realization of [−finite] tense in the TP. Therefore, it must occur in complement clauses, not in matrix (finite) clauses. Typically, it needs to be licensed by lexical selection (notwithstanding Laka’s [1990: 197–200] evidence for selection as a compositional process where ‘the inflectional elements of the matrix sentence play a role’).

For English, the problem goes unrecognized if the form of the main verb that occurs with modals in matrix clauses is assumed to be a bare or stem form rather than a (bare) infinitive. However, modals like ought (standardly cited as ought to) clearly select an infinitive. Perhaps in recognition of this, Kayne (1991) (reported in Zanuttini [op. cit.]), postulates an empty modal in the Italian matrix infinitive construction described below.

Italian has a ‘true imperative’ verb form that occurs only in the second person singular (the second person plural and the first person plural use the indicative verb form). This ‘true imperative’ cannot be negated by non: what occurs in the negative is an infinitive verb form.

According to Kayne (1991), the negative licenses an empty modal that licenses the infinitive. According to Zanuttini, non itself needs to be licensed by a TP, absent in true imperatives, but present in infinitives. (Though not a finite form, the infinitive has ‘some inflectional morphology’, namely, the suffix re—which may be tense, or may be the head of an InfP—which suffices to license non.)

What militates against similar ad hoc solutions for Kannada (for example, illa could be said a matrix element that selects nonfinite complements) is the fundamental, non-peripheral nature of the phenomenon with respect to Kannada clause structure.

6. Stowell presents the contrast (i, ii):

There is an inference in i, but not in ii, that Jim did not lock the door. This would follow if infinitives and gerunds differed in their tense specification. Infinitives might have a tense operator with the specification unrealized (with respect to the matrix tense). The familiar purposive interpretation of infinitives would thus be explained, as also the inference in iii, where the bringing of the wine is unrealized with respect to the remembering:

Stowell argues that gerunds, on the other hand, have no tense operator: the ‘understood tense of the gerund is completely malleable to the semantics of the governing verb’. Thus since remembering refers to the past, the wine-bringing is in the past in iv below, whereas the locking of the door in ii is simultaneous with the trying, or even unrealized with respect to it:

7. Temporal aspect can be ‘added’ into 7c if a dummy carrier iru ‘to be’ is inserted for this morpheme:

8. Note that the truly “bare” infinitive cannot be substituted by a gerund in my dialect. The significance of this point emerges in comparison with dative case-marked contexts, where the dialectal facts appear to argue for a neutralization of gerunds and infinitives in favor of a single ‘nonfinite’ category in Kannada. (I thank Hans Kamp for drawing my attention to the last point.)

The point that in non-dative-marked contexts, gerunds and infinitives have different privileges of occurence irrespective of dialect, can be illustrated both ways. While only infinitives are permitted in past negative and in passive sentences, only gerunds are permitted in the subject position of verbless copular sentences, and in conditional clauses:

9. Negation of a dative case-marked nonfinite verb (examples [11] in the text) yields a modal of prohibition: maaDali-kk-illa (maaDuvudi-kk-illa), ‘cannot or should not do.’ Notice that these readings are in the expected direction: what is prohibited is an unrealized event, and the verb form that occurs is the dative case-marked infinitive. (Compare the English be + to inf. construction, which functions as a modal of obligation.)

Like example 11, example 12 in the text also has a legitimate reading ‘It has been possible to build a house there,’ with the nonfinite clause serving as a clausal complement to the verb aagu ‘happen’ (‘it has happened [pro to build a house there]’). A ‘dative subject’ can occur in 12:

10. Guasti (1993: 150) reiterates the facts about English bare infinitives. She, however, notes that the accusative-infinitive complement to perception verbs in Romance may have an imperfective aspect; it is in this respect like the English acc-ing construction.

11. Martin (1992b), reported in Boskovic (1997: 11 and 179 n. 9) appears to have made the opposite move, generalizing the label ‘tense’ to aspect. Starting with the observation that eventive predicates contain a temporal argument that must be bound by (any one of) Tense, aspectual have and be, or adverbs of quantification, Martin reportedly treats have and be as specified for [+ tense] in the ‘raising’ complements John believed Peter to have brought the beer/to be bringing the beer. It is not apparent (however) how this meshes with his proposal (built on Stowell 1982) that [+ tense] infinitivals are control structures (since only [+ tense, − finite] I checks null case, permitting PRO), while [− tense] infinitivals are raising structures.

12. The idea that for is ‘semantically active’ is due to Bresnan (1972).

Jayaseelan (1987) argues from a different perspective to conclude that ‘a to infinitival interpreted as describing an “unrealized” event invariably contains for underlyingly’. He regroups try- type verbs with want- type verbs (rather than believe- or seem- type verbs) with respect to complement selection, adducing evidence from Malayalam, as also from ing- ‘infinitivals’ in English: pointing out that the latter include the (little noticed) obligatorily controlled complements to succeed in, fail at, tried.

In his analysis, the lexical subject of a nonfinite clause is a reflex of (i) the ‘case-absorbing’ properties of the matrix element (e.g. try always absorbs the case of for), and (ii) the ability of ing or to to ‘pass on’ a case from a matrix element (adapting Reuland’s 1983 analysis).

Jayaseelan also points out that infinitive adjuncts and infinitival relatives with for have the unrealized interpretation: …went to market for his wife to buy a pig; the man (for you) to cultivate. … We may add that purposive infinitives in nursery rhymes show a for: for to catch a whale (Simple Simon), for to buy a pig (To market, to market).

Stowell’s (1982) analysis, which locates the ‘tense’ of infinitives in COMP, may be taken as indirect support for our claim, since for is located in COMP. Stowell also notes (1982: 569) the following data: To kill animals … does not have an unrealized interpretation (being aspectually equivalent to Killing animals …); but ‘the unrealized tense suddenly reappears’ in For John to kill his goldfish …, where there is ‘a lexical complementizer for in COMP.’

13. The idea that perfect or progressive aspect assigns a ‘weak’ case to the verb’s subject receives support from Jayaseelan, who notes (1984: 627–28) that a have or a be in the English ‘absolute’ construction allows a lexical subject where only PRO is otherwise possible:

Jayaseelan generalizes this observation to Malayalam, where lexical subjects are permitted only in adjuncts with perfect or progressive aspect markers.

We term this a ‘weak’ case because it sanctions a lexical subject only in nonfinite or dependent clauses.

14. Chomsky (1995: 119–120) proposes that PRO receives a null Case from to or ing. The motivation for this is the argument-like behavior of PRO (which moves from non-Case positions, and is barred from moving from Case positions).

However, Boskovic (1997: 178, n. 6) credits to Lasnik the generalization of this problem (in i) to ii) and to Martin (1992a) the proposal that follows: which suggests that an alternative account of the problem is possible.

‘…the construction is ruled out because the Case feature of to remains unchecked.’

15. There is yet another piece of interesting evidence from Kannada. The grammarian Spencer, speaking of the tense interpretations of negative sentences, tells us in a footnote (1914: 51) that in the Southern Maratha variety of Kannada, ‘maaDuvudilla is present and maaDlikkilla is future’. Notice that the latter is a dative case-marked infinitive, which (as predicted) has the ‘unrealized’ interpretation.

Spenser does not speak about whether this variety retains the bare infinitive form maaDlilla for past. If it did, it would indicate a three-way distinction past, present, future, using respectively the bare infinitive, the gerund, and the dative infinitive. However, a more likely possibility is that (in line with the tendency of languages to have a two-valued tense system) this variety distinguishes future and non-future rather than past and non-past. (cf. Chung and Timberlake 1985: 204: ‘The direct encoding of three tenses is not particularly common. It is more usual to find only a two-way distinction in tense, either future vs. non-future or past vs. non-past.’)

16. The modal of prohibition beeDa can take either an infinitive complement or a gerundive complement. The infinitive permits only a 2nd person subject, and has a prohibitive reading:

The gerund has a negative permissive reading: it has an impersonal rather than an imperative interpretation even with 2nd person subjects.

These facts are parallel to the English facts in (iii):

The stage of the language which had a negative infix in the finite clause also had modal infixes. Whereas the infixal negative is now found only in nonfinite contexts, an archaic modal construction still occurs in the matrix: niinu yelladru bidd-ii, ‘(I fear that) you may fall.’ The verb in the modal conjugation inflects for agreement, but tense is not present: avanu bidd-aanu, naanu bidd-e, etc.

17. Pollock (1994) proposes that ‘the seldom recognized functional category of mood … should be the head of Mood P, which … is the highest functional projection in French and Romance, as well as Old, Middle and Modern English clauses.’

References

Akmajian, Adrian. 1977. The complement structure of perception verbs in an autonomous syntax framework. Formal Syntax, ed. by Peter Culicover, Thomas Wasow, and Adrian Akmajian, 427–60. New York: Academic Press.

Amritavalli, R. 1977. Negation in Kannada. Simon Fraser University, Burnaby: Master’s thesis.

———. 1997. Copular sentences in Kannada. Paper presented at the Seminar on Null elements, Delhi University, January 1997.

Boskovic, Zeljko. 1997. The syntax of nonfinite complementation: an economy approach. Linguistic Inquiry Monograph 32. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Bresnan, Joan. 1972. Theory of complementation in English syntax. Cambridge, MA: MIT Doctoral dissertation.

Chomsky, Noam. 1995. The minimalist program. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Chung, Sandra and Alan Timberlake. 1985. Tense, aspect and mood. Language typology and syntactic description, volume III: Grammatical categories and the lexicon, ed. by Timothy Shopen, 202–58. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Emonds, Joseph. 1972. A reformulation of certain syntactic transformations. Goals of linguistic theory, ed. by S. Peters. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Guasti, Maria Teresa. 1993. Causative and perception verbs: a comparative study. Torino: Rosenberg and Sellier.

Hany Babu, M.T. 1986. The structure of Malayalam sentential negation. International Journal of Dravidian Linguistics 25 (2). 1–15.

Jayaseelan, K.A. 1984. Control in some sentential adjuncts of Malayalam. BLS 10, 623–33. Berkeley, CA: Berkeley Linguistic Society.

———. 1987. Remarks on for-to complements. CIEFL Working Papers in Linguistics 4 (1). 19–35. Hyderabad: CIEFL.

Kayne, Richard S. 1991. Italian negative imperatives and clitic climbing. New York: CUNY, ms.

Kittel, F. 1908 [1982]. A Grammar of the Kannada Language. New Delhi: Asian Educational Services.

Laka, I.M. 1990. Negation in Syntax: On the Nature of Functional Categories and Projections. Cambridge, MA: MIT Doctoral dissertation.

Lasnik, Howard and Mamoru Saito. 1991. On the subjects of infinitives. CLS 27, Part 1: The general session, ed. by L.M. Dobrin et al. Chicago Linguistic Society: University of Chicago.

Martin, R. 1992a. Case theory, A-chains, and expletive replacement. Storrs: University of Connecticut, ms.

———. 1992b. On the distribution and case features of PRO. Storrs: University of Connecticut, ms.

Pollock, Jean-Yves. 1994. Notes on clause structure. Amiens: Universite de Picardie, ms.

Rapoport, T. 1987. Copular, nominal and small clauses: A study of Israeli Hebrew. Cambridge, MA: MIT Doctoral dissertation.

Reuland, E. 1983. Governing -ing. Linguistic Inquiry 14. 101–36.

Rizzi, Luigi. 1997. The fine structure of the left periphery. Elements of Grammar, ed. by Liliane Haegeman, 281–337. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Shlonsky, Ur. 1997. Clause Structure and Word Order in Hebrew and Arabic: An Essay in Comparative Semitic Syntax. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Spencer, H. 1914. A Kanarese Grammar. Mysore.

Stowell, Tim. 1982. The tense of infinitives. Linguistic Inquiry 13 (3). 561–70.

Zanuttini, Raffaella. 1991. Syntactic properties of sentential negation: A comparative study of Romance languages. Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania: Doctoral dissertation.