R. Amritavalli

The Kannada clause raises interesting questions from a synchronic as well as diachronic perspective.* In earlier work (Amritavalli 2000), beginning with the puzzle of how tense was interpreted in negative sentences instantiating the ‘matrix infinitive’ and the ‘matrix gerund,’ I proposed that the finiteness feature of the Kannada clause resides in a Mood Phrase that hosts one of the heads agr (Indicative mood), neg, or modal. The category tense, now divested of finiteness, i.e. its function of “anchoring the sentence in time,” is consequently subsumable under that of temporal aspect in this language. Each of the heads of the Mood Phrase is seen to select an Aspect Phrase complement, some apparently finite in containing morphemes standardly taken to be ‘tense,’ now reanalyzed as temporal aspect; and some obviously nonfinite, i.e. the ‘matrix infinitive/ gerund’. The postulation of a Mood Phrase with a finiteness feature thus allows us to analyze a variety of superficial clause-types in Kannada in terms of a single underlying clause structure. This work is summarized in section 2.

In section 3 of this paper, I argue that the Mood P is a relatively new functional projection in the language. An older functional projection hosting agr, which was the sole marker of finiteness, looks to have yielded ground to a new projection of Mood which allows finiteness to be marked by the neg and modal elements in addition to agr. Simultaneously, a new functional projection or projections have evolved of temporal Aspect; and this is perhaps the first step in the evolution of a category of Tense in the language. These changes in the functional architecture of the clause are invoked to explain a variety of changes in the distributional facts concerning the cooccurrence of agreement with negation, agreement with modality, and negation with an interpretation of tense, in the history of Kannada. At a prior stage of the language, which had a ‘negative conjugation’ and a ‘contingent future tense’, markers for negation, temporal aspect and modality occur in a single, undifferentiated position in the clause. Negation does not permit temporal specification, and negation cooccurs with agreement. In the current language, both these facts are reversed.

Our account of the differentiation of the features of negation and temporal aspect, and their evolution into separate functional projections, allows us to strengthen Grimshaw’s (1991) proposal of extended projections with an interesting detail. The original proposal that functional projections share categorial features with related lexical projections does not address the question why this should be so; nor does it give a rationale, other than an observational one, for the identification of particular lexical and functional categories as categorially related. We argue the functional elements in the extended projection of a lexical category to literally originate in the lexical category, at a functional level of zero. It is lexical features that “migrate” or reinstantiate themselves in functional projections in the XP. In particular, the Kannada facts suggest that the feature content of heads of individual functional projections in the clause for negation, temporality and modality has its counterpart not only in the lexical aspectual features of a verb as an integral part of its meaning, but also in isolable morphemes with corresponding meanings which nevertheless lack individual clausal, functionally differentiated positions of their own.

Section 4 of the paper elaborates the clause structure developed in the preceding two sections by taking into account nonfinite negation in the matrix clause, and the occurrence of temporal aspect on “dummy verbs.” This structure is also seen to accommodate the semi-lexical auxiliary and the serial verb constructions in the language.

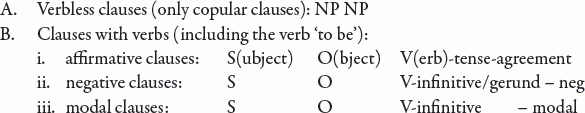

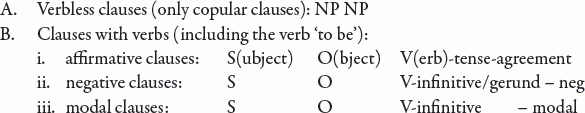

It has been a guiding intuition in research into clause structure that a variety of superficial clause-types may emerge from underlying structures that are only minimally different. The postulation of empty subjects in subjectless clauses; of tense projections in infinitival clauses, and even in verbless “nominal” clauses; and the Split-Infl hypothesis, are all examples of analyses that follow this leading idea. For this research program, the superficial wealth of finite clauses in Kannada is an embarrassment. Finite clauses in Kannada can be described under the following subtypes:

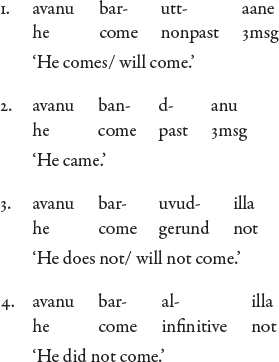

Restricting our attention for the moment to clauses with verbs, we see that these clauses appear to fall into three subtypes according to whether they are affirmatives, negatives, or have a modal.

In standard versions of clause structure, these three clause types differ only with respect to the presence or absence of the optional functional projections of negation and modality; but this is not the case in Kannada. In affirmative sentences, the Kannada verb is inflected for what is standardly glossed as tense, and agreement.

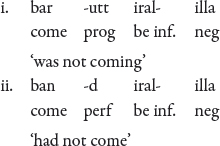

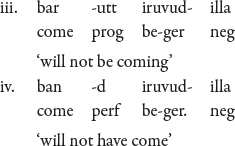

In negative sentences, tense and agreement morphemes are absent. The verb occurs in one of two nonfinite forms:

Negative sentences thus appear to be ‘matrix gerund’ and ‘matrix infinitive’ complements to the neg element illa, which appears to have the status of a verb. Illa is historically indeed a verb of negative existence.

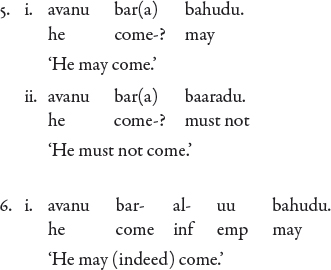

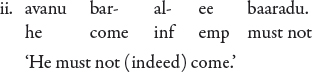

In modal clauses, again, what occurs is a ‘matrix infinitive’ complement to a modal element. Again, neither tense nor agreement are present. Nor can the negative element illa occur in these clauses. The negation of sentences with modals is accomplished, rather, by ‘negative modals,’ which have a lexically incorporated negative element. (In (5), the modal appears to take a bare verb stem as its complement. However, this complement is actually an infinitive; the examples in (6) show the expected infinitival ending -al surfacing on the verb when the emphatic morphemes uu and ee are present.)

Thus modal, like neg, takes a ‘matrix infinitive’ complement.

Summing up this description, tense and agreement morphemes occur only in affirmative clauses in Kannada, and modals and the negative look like main verbs that subcategorize nonfinite complements. Affirmative and negative/ modal clauses (then) appear to fundamentally differ in clause structure.

In Amritavalli (1998a, b, 2000) I propose an analysis that gathers up this descriptive diversity into a proposal for a single underlying structure for the Kannada clause.2 This is achieved by attending to two important details within the description of affirmative and negative clauses. The first detail pertains to the interpretation of tense in negative clauses. The second pertains to the apparently accidental homophony of the putative tense morphemes in affirmative sentences with the corresponding aspect morphemes. The unification I propose, based on these descriptive fragments, rests on the premise that Kannada has no functional projection labelled Tense. What is interpreted as tense is an Aspect head that is the complement of a Mood head; and what has been labelled tense in affirmative sentences is really aspect. On this analysis, affirmative, negative and modal sentences are shown to have a common structure, in that they all consist of an aspectual complement to a Mood head.

Let us briefly recapitulate the relevant arguments. Consider first the data pertaining to the interpretation of tense in negative sentences. Verbs in negative sentences, we said, occur in one of two forms: gerund, or infinitive. Which of these two nonfinite forms occurs depends on the tense of the negative sentence: gerund plus illa negates nonpast tense, infinitive plus illa negates past tense. Thus the negative counterpart of (1) is (3), and the negative counterpart of (2) is (4); these data are repeated below.

How does tense get read off the nonfinite verb forms in (3-4)? The argument I advance is that each of these forms carries its own, differing, aspectual specification. Consider thus the gerund in (3). This form is one of a paradigm of three forms of gerund in Kannada, the other two forms being the ‘negative’ gerund and the ‘perfect’ gerund. What we have in (3) is thus the ‘imperfect’ gerund, and this is the form that corresponds to a nonpast tense interpretation.

Coming to the infinitive in (4), we run into an immediate problem. This is a form interpreted as past tense; but Stowell (1982) argues the tense of infinitives to be “unrealized,” i.e., future. However, a careful cross-dialectal analysis of infinitives in Kannada reveals that there are two kinds of infinitives: bare infinitives, and case-marked (dative) infinitives; and that these two kinds of infinitives have quite different aspectual specifications. The infinitive that has the future, or unrealized, interpretation is the case-marked infinitive in Kannada, and the for-to infinitive in English. The bare infinitive (on the other hand) in both Kannada and English is interpreted as a perfect aspect. (This is the infinitive in the complement of perception verbs, e.g. I saw John cross the street, which is here interpreted as a completed action.) Now it can be shown that what occurs in the Kannada negative sentence (cf. (4) above) is in fact a bare infinitive, which, therefore, carries a perfect aspect, which is interpreted as a past tense.

Tense interpretation in the negative sentence, then, hinges on the specification for aspect of the nonfinite matrix verb. It is a plausible inference that the finite element in the negative sentence is negilla;3 i.e. that finiteness and tense interpretation are located at different heads in the Kannada negative clause.

Turning now to the affirmative clauses (1-2), if -utt- and -d- are indeed “tense” morphemes in the standardly understood sense of the term, these clauses must be very different in their realization of finiteness and tense interpretation, since both are apparently located in a single Tense head. We note, however, that the putative tense morphemes in Kannada are identical with the corresponding aspect morphemes. Thus -utt-, glossed as nonpast tense in (1), marks progressive aspect in (7), in the form bar-utt; and -d-, glossed as past tense in (2), marks perfect aspect in ban-d in (8).

Now if we take seriously this morphological “accident” of the identity of tense and aspect morphemes in affirmative clauses, we might treat -utt- and -d- uniformly as aspect. This would give us the interesting result of comparable structures for affirmative and negative clauses: both would exhibit an Aspect Phrase complement to some element X, where X is agr in affirmatives and illa in negatives. (Recall that the infinitive and gerund verb forms in negative sentences are marked for aspect.) The same structure would generalize to modal sentences.

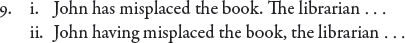

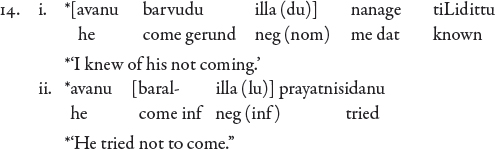

The proposal that “tense” in Kannada is in fact aspect actually follows straightforwardly from the observation—inescapable for negative and modal sentences—that the clause structure of this language has the property of separating finiteness and temporal information. Our claim is that affirmative clauses, too, utilize this potential the Kannada clause offers to separate finiteness from temporal information. We may understand finiteness as the ability of a clause to “stand alone,” to mean that a predication is related to the moment of speaking: it is “anchored in time”. In grammatical traditions that attribute finiteness to tense, a distinction has been made between “absolute” or “deictic” tenses that “relate the time of the situation … to the moment of speaking” (Comrie 1976:2, based on Lyons 1968), and “relative” tenses: “In English, typically, finite verb forms have absolute tense, and nonfinite verb forms have relative tense” (loc.cit.). So the English sentence (9i) has an absolute or finite “present perfect tense,” and (9ii) has a relative (nonfinite) “present perfect tense”:

Now suppose a language like English, called ENGlish, were to say (10) instead of (9i), where -s is still the 3rd person singular agreement morpheme:

Is the verb form having misplaced, without an agreement morpheme, tensed or nontensed? There would seem to be little justification for considering it nontensed in (9ii), but “tensed” in (10); especially if it could also be shown that ENGlish had the negative (11i), instead of the English negative (11ii):

ENGlish, we would rather say, “converts” the nonfinite verb form having misplaced into a finite form either by adding a negative element, or by adding an agreement morpheme.4

In sum, a careful description of three types of finite clauses in Kannada—affirmatives, negatives, and clauses with modals—shows that agr, negilla, and modal serve as heads of a phrase XP that takes as its complement an Aspect Phrase instantiating the main verb. We take the XP to be a Mood P, which is the locus of finiteness in the clause. (Observe that since we do not equate finiteness with tense, we solve the paradox of the “matrix nonfinite verb.”)5

Agreement morphology, we propose, is the reflex of Indicative mood, often taken to be the default or “null” mood. Kannada clauses thus have the general schematic structure (12), illustrated in (13):6

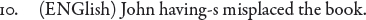

In the structure (13ii), the negilla occurs as one of the heads of Mood P, which we said is the site of finiteness. This implies that illa cannot occur in nonfinite clauses, where Mood P is (by definition) absent.7 The prediction is borne out: illa cannot occur in non-root gerundive and infinitival complement clauses.8

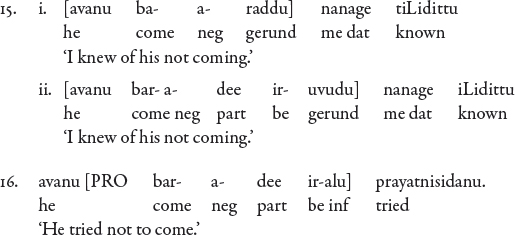

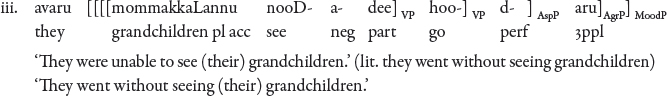

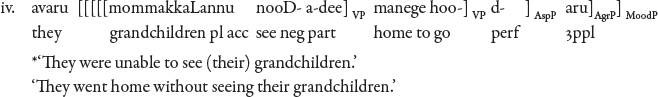

Negation in nonfinite complement clauses is achieved by a “negative verb,” a verb with an infixed negative element a. This verb, illustrated in (15-16), is the ‘negative gerund’ mentioned earlier; it is one of the three members of the gerund paradigm. (The negative gerund has the variants shown in (15i) and (15ii)).

The negative infix -a- is actually the historically prior negative element. It survives from a stage of the language that attested, in addition to the negative participle or gerund illustrated in (15-16), a finite “negative conjugation” or “mood.”9 In this erstwhile conjugation, the neg element occurred between the verb stem and the agr element in finite clauses: naanu maaD-e-nu, I do-neg-agr ‘I do not/ did not do’; other forms being maaD-e (2psg), maaD-a-nu (3pmsg), maaD-a-Lu (3pfsg), etc.10 Thus where earlier the neg -a- occurred in finite as well as in nonfinite clauses, it is currently restricted to nonfinite clauses, and a distinction has developed between finite and nonfinite clause negation.11

Note that in the negative conjugation, neither tense nor temporal aspect were marked. Negative verb forms were free with respect to tense interpretation. Kittel (1908:157) tells us that “the conjugated negative is used for the present, past and future tense, according to circumstances.” He later (op.cit.:332) emphasizes the point that the older “simple negative” differs in this respect from the current forms; he gives examples to show that gerund+illa forms of the “modern dialect take the place of the simple negative to express the present tense of the negative in a clear way,” and that infinitive+illa forms “are used in the modern dialect to express clearly the past tense …” (emphasis in the original).

Indeed, in the negative conjugation, ‘tense’ and neg were in competition for the same position in the verb; verbs surfaced either as Vstem-- neg –agr or as Vstem--‘tense’–agr. By ‘tense’ we must here understand an aspectual specification for a participle, precisely as we have argued for in the previous section, in our analysis of ‘tense’ in the current language.12

The stage of the language that had a negative conjugation also had a “contingent future tense” that expressed “probability, possibility or uncertainty: ‘I shall perhaps make,’ ‘I may perhaps make’ ” (Spencer 1914:34). In this conjugation again, the modal element occurred between the verb stem and the agr element: maaD-(y)ee-nu (1psg), maaD-ii (2psg), maaD-(y)aa-nu (3pmsg), maaD-(y)aa-Lu (3pfsg), etc. Spencer observes (loc. cit.) that this conjugation has been supplanted by the “invariable verbal form bahudu in combination with an infinitive,” i.e. the “contingent future tense” has yielded to the Modal + infinitive construction described at the outset: bahudu is the modal ‘may.’ We may add that the current modals are all free forms, which do not inflect for agreement.13

Beginning with the development of different forms for negation in finite and nonfinite clauses, we have now described the following changes in finite clauses in the language:

(a) Earlier, every finite clause had an agr. Currently only non-negative, non-modal finite clauses have agr.

(b) Earlier, neg and agr, and modal and agr, cooccurred. Currently, they do not cooccur.

(c) Earlier (however), ‘tense’ and neg did not cooccur. Currently, negative sentences have a tense-interpretation.

(d) Earlier, neg and modal were bound morphemes; currently they are free morphemes.

Clearly, agr has been (and continues to be) a marker of finiteness. This suggests that agr has always headed its own functional projection, with a finiteness feature [+F] of the clause located at this functional projection. In (17i-ii) we illustrate the erstwhile negative and modal conjugations.

But just as clearly, agr is no longer the sole marker of finiteness. The scope of finiteness marking has expanded to allow neg and modal as well as agr to signal finiteness.

We must thus minimally infer a change in the nature of the finiteness feature [+F], such that it can now be satisfied by a range of elements, including agr. But in fact, a stronger inference is necessary: that the finiteness feature has also relocated itself further “up” the clause. For if the finiteness feature continues in the same position as in (17), and the only change is that it is now “more expansive” and satisfied by a modal or neg element as well as by agr, we should expect the language to permit just the minimal change, and let the neg and modal elements “move over” and up into the position occupied by agr in (17). That is, agr would become “optional,” and simply by dropping the personal endings of agr in negative and modal clauses, the following forms would be allowed to surface:

But these forms are never attested.

Instead, simultaneously with the expansion in the range of elements that signal finiteness, the language has had to reinvent the forms of modal and neg as free, lexical forms. Why should this have been necessary?

Let us propose that the finiteness feature has moved out of the AgrP altogether, and has relocated itself in a position “higher up” the clause. Intuitively, we might expect such a change in the clausal position of [+F] to accompany the expansion of the range of elements marking finiteness: in a sense, the migration of [+F] out of AgrP into a new functional projection explains why finiteness is no longer identified exclusively with agr. Let us identify the new functional projection as MoodP: [+F] is now relocated in MoodP.

We know from the current language that the lexical realization of one of the three elements agr, neg or modal is necessary for the satisfaction of the feature [+F] in MoodP. Now in (19) below, which is the development that we propose from (17), we observe that the head agr of AgrP can straightforwardly move up into the head of MoodP, which is adjacent to it. But the movement of neg in (17i) or modal in (17ii) into the MoodP is blocked by the presence of the intervening projection of AgrP. At the time the clause structure of the language was changing, then, these possibilities in the MoodP could not have been realized through movement of the existing categories, across AgrP. Thus in the new clause structure, negation and modality had to be instantiated by the insertion of new lexical material into the MoodP: by merge rather than by move.

We thus explain why a finiteness projection whose scope has expanded or altered has resulted in the reinvention of neg and modal as free forms in the language. Only agr continues as an affix.

The proposal that the finiteness feature has relocated itself into a MoodP that is further ‘up’ the clause than AgrP also explains a puzzle in the pattern of complement selection by these three elements in MoodP. While agr continues to take the regular perfect and imperfect participial verb forms as its complement, neg and modal take infinitive complements (and neg takes gerundive complements as well). These latter elements thus pattern, in their complement selection, with higher predicates that subcategorize clausal complements. So robust is this complement selection property that the newly developed negative sentences in Kannada even choose to express tense interpretation (surely somewhat opaquely!) in terms of two types of nonfinite complements, gerundive and infinitival, rather than by the regular perfect and imperfect morphology.

To explain this, we may surmise that the MoodP projection is a constituent of the C-system rather than the I-system. Then if AgrP is part of the I-system (with agr moving into MoodP in the manner suggested above), and the functional projections for gerundive and infinitival morphology occur higher than AgrP, we would account for their unavailability as complements to AgrP, while their proximity to the Mood head would make them the natural choice of complement for elements lexicalized in MoodP.

The account of clause structure change developed so far is also an account of the progressive differentiation of the elements of ‘tense,’ modality, and negation in the Kannada clause. To recapitulate, these three elements were at one stage all in competition for the same position, or functional slot, in the clause. The presence of any one of them was all that was necessary, or possible, in the finite clause:

Such complementarity of distribution is classically a diagnostic of categorially commensurate elements. Yet the subsequent differentiation of these elements shows them to have been discriminable as well. What is the category in (20) in which these elements are instantiated?

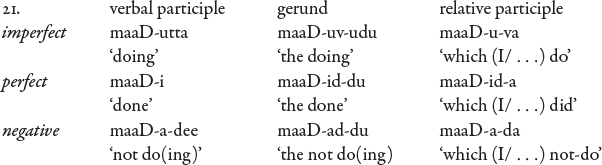

We shall maintain that this is the category of Aspect. One current definition of Aspect is that it is the internal temporal contour of an event; but perhaps “internal contours of events” need not be restricted to the merely temporal. We have seen that in present-day Kannada, the participial and gerundive forms are specified with internal contours not merely for temporality but also for negativity; suggesting that negation here has a categorial specification comparable to temporality. Let us list below the currently extant forms, viz. the verbal participle, the gerund, and the relative participle, to illustrate this parallelism between negation and temporality. The temporal feature or morpheme in (21), we have said, must be aspect; and it is a reasonable conjecture that this is the categorial specification for the negative feature or morpheme as well.

Now, if we grant that negation is an aspect in (21), it is a reasonable conjecture again that this was also the category of the negative and modal morphemes in the earlier language illustrated in (20), which had a negative conjugation, and a contingent future conjugation. This is because the same parallelism between temporal and negative elements that is now seen in the participles obtained earlier in finite clauses as well: these were both complements to agr. We have argued that the temporal complement to agr is an aspectual complement; Caldwell’s remark (in n. 12) that the Dravidian tenses are formed from participles suggests that this has been a stable feature of the language. Thus there is good reason to surmise that the modal and negative elements in (20) are also aspectual elements.

Aspect is fundamentally a feature of the semantics of the verb; there are predicates that are inherently durative or completive, for example. Our suggestion is that lexical semantic features such as negative and dubitative are also aspectual features. Beginning with cases of fully lexicalized aspect, then, we may have at the other end of the spectrum a series of functional categories, specialized for negation, modality, or temporal aspect. At these functional positions in the clause, however, negation and modality are commonly considered to be realizations not of aspect, but of mood; thus we have argued that in Kannada, they are located in MoodP.15

What we see in Kannada is that in the route from fully lexicalized aspect to individual functional projections for prominent aspectual categories, there is an intermediate stage, illustrated in (20). At this stage, although various kinds of aspect are each located in their own particular, identifiable morpheme, these morphemes are not yet themselves located in individual functional projections in the clause. They are all located in a single projection that we have called Aspect. (It is difficult to say whether this Aspect projection had the status of a functional projection, or was still within the verb’s lexical projection, in some sense.)16

This account of the development of functional projections in the clause, from a lexical origin via a general category to well-defined individual projections for temporal Aspect and Negation, adds content to Grimshaw’s (1991) proposal of Extended Projections. The idea of an extended projection is that certain functional categories have the same categorial features as the lexical categories they are extensions of; lexical and functional categories within an extended projection differ only in functional level (zero for lexical categories, one for functional ones.) Grimshaw develops her proposal from the observation that functional and lexical categories cannot be paired off anyhow; the intuition to be expressed is that “a functional category is a relational entity. It is a functional category by virtue of its relationship to a lexical category.” This intuition that DP is the functional category “for N,” and IP “for VP,” is captured in the extended projection proposal by the allotment of common categorial features to certain functional and lexical categories.

However, the logic of the initial assignment of such common categorial features only to certain lexical and functional category pairs, and not to others, is left unaddressed by Grimshaw. Our proposal enriches hers with the detail that functional projections in fact start out at the lexical level of those very lexical categories that they are peceived to naturally belong to. They start out at the functional level of zero, and that is why they inherit or retain the categorial features of the lexical categories they extend. On this analysis, the content of a functional category must in some way be semantically coherent with its lexical category.

Summing up, the changes in Kannada described in (a–d) in section 3.2 above are changes in the functional architecture of the clause. A functional projection for agr hosting a finiteness feature [+F] has lost that feature, which has migrated upwards, become more inclusive, and lodged in a new functional category of Mood.17 With this change, an earlier generalized category of Aspect (located at the verb stem, and including temporal, negative and modal elements) has broken up, differentiating itself along the temporal/ non temporal dimension. In finite clauses, these are currently located at distinct projections. Hence in the contemporary language, temporal aspect and negation cooccur, which they were unable to earlier; and Kannada negative sentences currently permit a tense interpretation.

Our discussion this far suggests that with the development of the MoodP and the finite negilla, “infixed” negation (neg -a-) has been relegated to the nonfinite complement clause. “Negative verbs” or neg-internal verbs do still occur, however, in the matrix clause, in specific types of constructions. We shall now illustrate and discuss these.

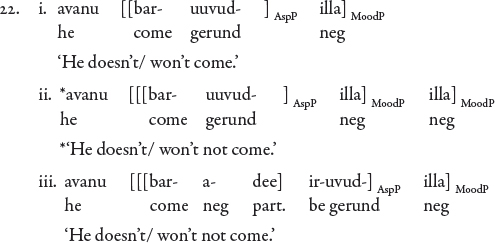

We saw in section 3.1 that negilla, being a constituent of MoodP (the site of finiteness), cannot occur in nonfinite complement clauses. Now if the MoodP with its finiteness feature [+F] can have only a single realization or occurrence in a finite clause (as seems reasonable), we expect a further restriction on illa: it should not occur more than once, even in the matrix clause. This prediction is borne out: illa cannot occur twice in clauses with double negation. This is illustrated in (22) below.

Example (22i) is a negative sentence. This sentence cannot itself be negated as in (22ii), with two illas (contrast the English translation, which permits not to occur twice). It must be negated as in (22iii), where illa cooccurs with a negative verb, i.e. the negative “infix”.

Example (22iii), where a negative -a- occurs in the matrix clause in the current language, naturally invites comparison with the erstwhile negative conjugation that instantiated this element in finite clauses: cf. (23).

We note the now familiar historical development that whereas the negative conjugation (23) precludes the occurrence of any temporal specification, the double negation (22iii) has a tense-interpretation by virtue of the gerundive morphology uvud-.

Observe, however, that in the double negation (22iii), the gerundive morphology uvud- does not occur on the stem of the verb bar- ‘come’, as it does in the standard negative (22i). In (22iii), the stem of the verb bar- ‘come’ supports the negative participial suffix. The gerund suffix in (22iii) occurs on a verb ir- ‘be.’

This then is the very familiar phenomenon of a “stranded” affix requiring “support,” and it is now seen to be an expected and typical indication of an extended projection. What we observe in Kannada is that the development of functional projections appears to make its own demands on the lexical resources of the language. Thus the movement of [+F] out of AgrP into a MoodP resulted in new lexical forms for modality and negation that could satisfy that feature in its new projection, as we saw in the previous section. While (therefore) the repositioning of negation and modality in the clause was obvious, it was less apparent whether or not temporal aspect had been left to continue undisturbed in its earlier position, i.e. the position in (20iii), at the right edge of the verb stem. What we see in (22iii) is that temporal aspect, too, has moved “up and out” into the clause, for it now occurs separated from “its” verb stem, in a functional projection. This is what allows it to cooccur in (22iii) not only with the finite negilla, but also with the neg -a-, with which it was earlier in complementary distribution. We may speculate that the relocation of temporal aspect into a functional projection is perhaps the first step towards the development of Tense in this language.

Thus the three elements in the erstwhile single position between the verb stem and agreement—namely temporal aspect, modality, and negation—appear to have each gone their own way. Interestingly, whereas the older, “infixal” modals appear to be dying out, the older “infixal” negative continues to occur as a neg in the language, in non-finite clause positions.

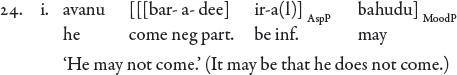

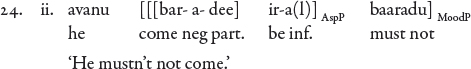

We observed earlier that negative and modal elements are in complementary distribution in the MoodP, and that therefore Kannada attests “negative modals,” in a kind of synthetic negation. We now add that it is possible for a verb with a neg -a- to occur with a modal, as in (24i), where the modal scopes over the negation. (Recall that modals take an infinitive complement, and note, in all the examples that follow, that the “stranded” infinitival affix a(l)- occurs on a “dummy” verb ir- ‘be’.)18

“Infixal” negation can cooccur with a negative modal (24ii).

In (24iii) the optative -i- cooccurs with the negative “infix”.

We have shown that negative verbs occur in matrix sentences that are modal or negative clauses, with the gerundive and infinitival morphology characteristic of such clauses occurring in a separate functional projection. Let us now illustrate negative verbs in affirmative matrix clauses, to make the same point: the perfect or imperfect aspectual morphology of affirmative sentences can occur separated from “its” verb, in an independent functional projection.

Examples of negative verbs in affirmative matrix clauses are typically sentences with “semi-lexical auxiliaries:” verbs that add shades of aspectual meaning to the clause, such as inadvertance, unfortunateness, suddenness, completeness, and so on.19 Consider examples (25i-ii), where the semi-lexical auxiliary hoog- ‘go’ contributes a tone of regret at the non-occurrence of an event (by indicating inadvertence). Here the negative element that occurs is -a-, and the auxiliary picks up the standard aspect morphology of affirmative sentences. Compare the use of participial negation in the food went/ remained uneaten: this sentence entails or conveys the sense of the food was not eaten, but its verb is affirmative.20

We have seen that whenever “infixal” negation occurs in the main clause, the negative morpheme stays tightly bound to the verb stem which it negates, forcing the aspect morphemes—whether these are the “regular” perfect and imperfect morphemes of affirmative clauses, or the nonfinite gerund or infinitival morphology of modal and negative clauses—to occur separated from this verb stem. The negative -a- cannot occur independently of its lexical category host. It behaves like a derivational suffix, which does not occur separated from its stem, being a lexical and not a functional categorial element. In other words, the negative -a- now finds place only within the negative verbal participle; and this participle takes its place in the paradigm of verbal participles listed in (21) above, the other participles being the perfect and the imperfect.

We shall say that all these participles remain within the VP; i.e. the negative, perfect or imperfect aspect morphemes in them do not occur in extended functional projections, and so these verbs do not raise out of the VP. (We return to the question of verb raising in the last section.) We can now thus assign a VP label to the negative participle in the structures (24) and (25).

Given that perfect and imperfect participles can as well occur in this position, we now have a structure for the Kannada clause that accomodates its “compound tenses,” as well as two typical construction types in the language: the “conjunct verb” or the semi-lexical auxiliary, and the serial verb, given two additional provisions: one, the participial VP is iterable; and two, the participial VP appears to have a default morphological specification for perfect aspect.

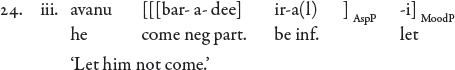

We have already illustrated the semi-lexical auxiliary in (25), with a negative participle. We now illustrate affirmative sentences with semi lexical auxiliaries. In (26i), the verb oDe‘break’ occurs with a nonpast interpretation, without any aspectual modification by a semi-lexical auxiliary. In (26ii), it is instantiated with the semi lexical auxiliary hoog- ‘go,’ which indicates inadvertence. And in (26iii), there occurs a second semi-lexical auxiliary biD- ‘leave,’ which indicates completeness or irretrievability.

Notice that the inflections of aspect and agreement in (26) inevitably occur on the rightmost verb (the morpheme sequence utt-e shifts from oD- ‘break’ to hoog-‘go’ to biD- ‘leave’ in (26i-iii)). Notice also that any verb other than the finite verb inevitably occurs in the perfect form in this sequence.

The clause structure of the semi-lexical auxiliary (as Jayaseelan (1997) notes) generalizes to what he calls the serial verb construction in Malayalam. This construction, which has similar properties in Kannada and in Malayalam, is described by him as a series of verbs—any number of verbs, of which only the last verb is finite. Jayaseelan gives the example:

Here, the verbs other than the last one are all in a perfect participial form. Let us consider an example in Kannada parallel to Jayaseelan’s Malayalam example:

In (28i), although the sentence refers to a nonpast event, every verb except the last is in the perfect form. (Notice too that “each verb can have its own direct object (or other complement),” as Jayaseelan points out; thus an object ad-anna, the accusative form of the pronoun it, occurs in the final, finite clause in (28i), coreferential with the object (raw mango) of a subordinate clause.) The perfect morphology appears to be a default specification for the participles. However, in (28ii) and (28iii) below we see that negative and progressive participles are also attested in the serial verb construction. Compare the occurrence of a negative participle in the semi-lexical auxiliary construction (25).21

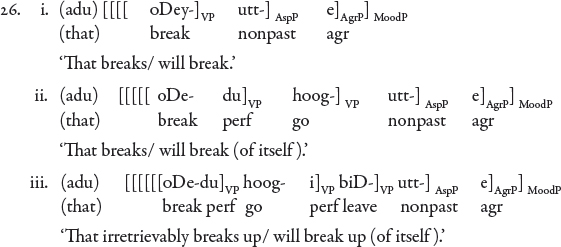

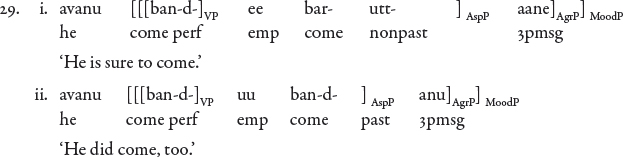

Does the Kannada verb raise out of the VP to inflection before spell-out? We conclude by presenting some suggestive data from verb emphasis.

The emphatic morphemes uu and ee suffix to nouns as well as to verbs in Kannada. Their attachment to nouns is straightforward: Rama-(n)ee banda, ‘Rama himself came;’ Rama-(n)uu banda, ‘Rama, too, came.’ But in emphasizing verbs in affirmative sentences, ee/uu show an interesting restriction: they cannot attach to the inflected main verb. They attach to a copy of the main verb in the default, perfect form. The verb bar- in (29i) has the imperfect inflection, and in (29ii) the perfect. In either case, the emphatic morphemes ee/uu attach to a verb-copy in the perfect form.

The evidence presented so far about the position of participles argues the verb-copy to be in the VP. This suggests that the emphatic morphemes ee/uu attach only to maximal lexical projections, such as NP and VP. If they cannot occur attached to functional projections, the need for a verb copy in the VP when a verb moves out of it before Spellout is explained. Thus emphasized verbs also appear to provide evidence that the verb moves out of VP before Spellout, to check its inflections.

That there is no morphological prohibition against ee/uu attachment to an aspect-inflected verb is evident from (29ii), where the inflected (perfect) stem is identical with the reduplicated stem. Again, ee/uu can attach to an imperfect verb stem (e.g. bar-utt-) in the present perfect form. Thus the contrast of (30) with (29i) reinforces the suggestion that the operative fact is the VP boundary.

The wrinkle in the data is that with gerundive and infinitive verb forms, ee/uu attach to them straightforwardly. Verb-copying is not necessary.

By the ee/uu attachment test, then, the gerundive and infinitive verbs do not climb out of the VP before Spellout. But we have presented evidence from suffix “stranding” that the suffixes of gerunds and infinitives occur in their own functional categories; they pattern in this respect with the perfect and imperfect morphology of affirmative clauses. How do we resolve the contradiction?

Either ee/uu attachment is to a nonlexical category in (31-32), or the reduplication rule is more complex than what we have described.22 A suggestive fact is that the infinitive in modal sentences allows emphasis in two ways: either by direct suffixation, as in (31), or by emphatic verb-copy, as in (33i). In contrast, the infinitive in the negative sentence does not permit emphatic verb-copy (33ii). This last example has only non-emphatic readings, either contradictory, or serial-verbal: “He came but didn’t come/ He came (somewhere) but didn’t come (here).”

Our analysis of the Kannada clause, while suggesting that finiteness is not universally identified with Tense, charts the relocation of the finiteness feature over a period of time from an agr projection to a MoodP in CP. Since the history of English shows a complementary movement of Tense from the CP into IP, the instantiation of finiteness in CP or IP would appear to raise interesting possibilities for parametric variation. Acquisition data exhibiting matrix infinitives in languages where finiteness is ultimately identified with Tense (Wexler 1994) are consistent with a parameter-setting approach; more so because initial explanations of the Optional Infinitive period, implicating purely maturational considerations, have been called into question by tense-marking and its acquisition in second-language and specific language impairment contexts (Paradis and Crago 2000).

The functional architecture of the clause can be said to literally grow out of lexical categories, extending their projections. As the change from bound to free forms for neg and modal in Kannada shows, the relocation of semantic features resulting from the extension of projections may require their re-lexicalization. Thus changes in clausal architecture may provide a window of explanation for the well-documented phenomenon of the grammaticization of lexical items.

* My thanks to P. Madhavan, Jeffrey Lidz, and the anonymous referees for their comments on this paper. All shortcomings remain my own.

1. The Dravidian verb has two stems, referred to in the literature as the non-past (or present tense) stem, and the past tense stem. The past tense stem is historically derived through morphophonemic changes from a form with an older “past tense” or perfect suffix. Thus Kannada ban-d- is derived from bar+nd, where -nd was the perfect suffix. Cf. Amritavalli and Jayaseelan (2000[2002]), n.1.

2. Amritavalli and Jayaseelan (2000[2002]) refines these proposals and extends them to Malayalam, a “sister” Dravidian language.

3. Although illa is historically a verb of negative existence in Kannada, not all current instances of illa are be+neg; i.e., illa has been reanalyzed simply as neg in these languages. This “two-illa” theory propounded by Hany Babu (1986) for Malayalam is explicated in Amritavalli and Jayaseelan (2000[2002]).

4. Note that example (9ii) shows that the occurrence of “compound tenses” is independent of finiteness. In Kannada, the matrix gerund and the matrix infinitive verb forms in negative sentences are attested in compound tenses. The negative (i), a past progressive, is the counterpart of (7) above, and (ii), a past perfect, is the counterpart of (8) above. Here the past interpretation is given by the matrix infinitive.

In (iii-iv) we illustrate a matrix gerund in compound tenses (yielding the future perfect/progressive).

Jeffrey Lidz (p.c.) points out the existence of a negative form band-illa. This form has a present perfect interpretation (‘has not come’); its imperfect counterpart is barutt-illa, ‘is not coming.’ The illa here is the “main verb” illa (cf. n.3 above). Cf. Amritavalli and Jayaseelan (2000[2002]) for detailed discussion.

5. We speculate that this option of separating finiteness from tense in UG may account for the “Optional Infinitive” (OI) stage in acquisition (Wexler 1994).

By attributing to Mood P “the locus of finiteness in the clause,” we ascribe to it the referential or deictic properties of Tense: MoodP connects the sentence to the world, through reference (to possible or actual worlds). This account (a reviewer observes) “depletes the normally referential IP system and shifts reference to the CP system.” (We may say that Indicative Mood refers to the real world, entertaining then the possibility that neg illa occurs in the scope of Indicative Mood.)

The location of finiteness (or referentiality) in Mood P, where it may be realized as Agr, allows us to account for the “nominal” clauses, or verbless copular clauses, in Kannada and Hebrew (Rapoport 1987) without recourse to an unrealized Tense, or an unrealized verb. These clauses instantiate nominal agreement (with gender and number features, but no person features). If these features are the realization of Agr in Mood P, the structure of such clauses differs from affirmative clauses with verbs only in lacking an Aspect P (which may be part of the IP system, and an extended projection of VP). The “nominal” clause is a CP: it is introduced in embedded finite contexts by the regular complementizer anta (cf. Amritavalli 2000, n.2.) Expanding a little, Kannada actually attests two kinds of copular clauses, with and without the verb be (respectively); both are CPs. In the copular clause with be, the predicate nominal is marked with –aagi, a complementizer-inflection for small clauses that appears also in “predicate complement” (elect X president) and raising-to-subject structures. Cf. Amritavalli (loc.cit.).

6. I shall assume an underlying head-complement word order for Dravidian, as argued for in Jayaseelan (2001), following Kayne (1994).

7. A reviewer points out that this assumption (that “a functional head should in general either be present or not present”) raises a methodological issue. While Agr (e.g.) is projected only where required, Tense is usually assumed to be present, but marked [−finite], in nonfinite clauses. (Again, Laka’s (1990) Sigma P contrasts with Pollock’s (1992) “take-it-or-leave-it” Neg P in allowing a choice between Neg and other values.) Descriptively, either account of Mood P would appear adequate for Kannada. The reviewer wonders if the stronger methodological claim is intended, namely that functional heads that do no work should be eliminated, thereby reducing the existence of negative feature values in the syntax corresponding to morphological nulls.

The methodological claim may be worth making, notwithstanding the overarching concern to maintain uniformity in clause structure. If Mood P is linked to reference, it may be more conceptually coherent for it to be absent from certain clause types (than to be present but negatively marked). This would also allow us to distinguish putative morphological nulls “associated with negative feature values” from the morphological nulls for functional categories that are arguably present in child language or second language acquisition data. E.g., at the OI stage, children distinguish finite and nonfinite verb forms positionally in the clause, though not morphologically; the “finite” matrix nonfinites are arguably licensed by a null tense or Mood P.

8. illa can of course occur in finite embedded clauses:

9. Caldwell (1913:468) prefers the term “negative voice.”

10. Cf. Spencer (1914:42), Amritavalli (1977:15-16, 20). Although a neg morpheme -a- is not uniformly identifiable in all these verb forms, Kittel (1908:161) assures us that “there can be no doubt” about the common origins of the negative participle and the conjugated negation, both being “based … on the so-called infinitive ending in a.”

11. The loss of the conjugated negative is relatively recent. Kittel in fact lists these verb forms as extant in the “modern dialect,” but adds the qualification: “The conjugated negative is somewhat seldom used in the modern colloquial dialect (except in proverbs …)” (1908:159).

12. Cf. also Caldwell (1913:486): “Most of the Dravidian tenses are formed from participial forms of the verb … commonly called verbal participles or gerunds …” He goes on to observe that Kannada has a “present verbal participle” and a “preterite verbal participle.”

13. The sole exception is the inability modal, which takes agreement. But this has an archaic flavour, and is no longer the preferred form for this function; it is probably a “peripheral” fact of the language, comparable to the fact that the “contingent future tense” (as well) vestigially survives in the written—and in a few forms, even in the spoken—language.

14. It is difficult to satisfactorily translate this form. Kittel (1908:158) resorts to exhaustive listing, translating (20i) as the set ‘I do not make, I did not make, I shall not make, I have not made.’ But the flavour of this form is perhaps better conveyed by English participial negation, which has a similar freedom of tense interpretation: Unseen by me,(John makes, made, was making, had made, will make a sign); On not hearing from John, (I wrote / had written/ have written/ will write…). In our imagined language ENGlish, participial negation might surface as a finite form with the mere addition of an agreement marker.

15. A reviewer points to this dual characterization of negation (as aspect, and as mood) as a potential problem; but this may not be so if we take into account the interaction of negation with finiteness and clausal position. We have said that Mood appears to be a sentential, perhaps CP-level, category. Aspect is perhaps a VP or at best an IP category, or just a lexical feature. What the traditional nomenclatures mood, etc. reflect (thus) may not be the substance of features, but the positions or domains of their realization. Compare the nomenclatures “relative” and “absolute” tense, or “aspect” and “tense,” for temporal features in nonfinite and finite clauses respectively.

Negation-as-mood is a familiar idea in some traditions. However, the same reviewer points out that “logically these are rather different operators”: “negation seems to occupy a much more central role in languages in terms of what is and what is not,” whereas mood may not even be overtly marked in some languages (e.g., English has no subjunctive).

This difficulty may be avoided if the basis for mood distinctions in language is the notion of “veridicality,” with negation the special case of non-veridicality that Giannakidou (1997) terms “averidicality.” Then all languages mark veridicality (Indicative mood) and averidicality (negation), but may or may not mark other types of non-veridicality such as the subjunctive.

16. Thus negation occurs in the modal at a lexical level in the negative modal (cf. examples (5-6) above).

17. Platzack (1995) develops the idea that “the tense affix and the finiteness feature [+F] are in different functional heads (Iº and Cº respectively),” to explain the difference between non-verb-second and verb second languages. The loss of verb-second in English is here seen as a change of position for [+F] from Cº to Iº. The change we suggest for [+F] in Kannada is in the reverse direction (from AgrP to MoodP).

This is consistent with a reviewer’s observation that the development of a MoodP in Kannada is “perhaps exactly the opposite” of what happened in languages like English, which is considered to have lost mood distinctions (cf. Pollock 1992).

18. A reviewer raises the question of a minimalist implementation of the idea of a “stranded” affix on a “dummy” verb. Our main concern here being to motivate a functional projection for Aspect, we can remain agnostic between treating verb forms like ir-uvudu in (22iii) like any other verb (generated in the VP, and raised to inflection), or giving ir- ‘be’ a designated status in the lexicon (similar, e.g., to that of epenthetic vowels, which ensure that syllable structure requirements are met), allowing it to merge directly into the appropriate functional position in the tree.

19. The main verb and semi-lexical auxiliary pair is sometimes called a “conjunct verb” in the literature.

20. Semi-lexical auxiliaries can also occur in negative sentences with illa. In (i), the auxiliary biD-‘leave’ conveys a sense of inadvertent suddenness in the saying. Notice that it picks up the gerund morphology:

21. A reviewer points out that “in serial verbs the main verb is at the right end, after all the stacked nonfinite verbs, while in negatives as well as in the sequence with semi auxiliaries the main verb comes to the left end.” The suggestion seems to be that the semi-lexical auxiliaries are in functional rather than lexical positions in the clause. On our account, the difference between a semi-lexical auxiliary reading and a serial verb (main verb) reading is not structurally encoded.

Semi lexical auxiliaries, in English as in Kannada, do not possess the full complement structure of the corresponding lexical verb. Consider thus English go, which, like Kannada hoogu ‘go’, has an auxiliary interpretation in (i), where it occurs without a goal argument. In (ii), with a goal argument, it is only interpreted as a full verb.

But Kannada examples like (i) are in fact ambiguous, since the goal can be a pro. Our claim is that (25ii) (=(iii) below) is ambiguous between a serial verb and an auxiliary reading for hoogu ‘go’.

Example (iv), where hoogu occurs with a goal argument, allows only the full verb interpretation.

22. A reviewer points out (thus) that if the verb leaves a copy of itself before it climbs out of the VP, it must illegally cross the emphatic heads ee/uu. (Hence the verb copy cannot simply be a trace spelled out.)

References

Amritavalli, R. 2000. Kannada Clause Structure. In Rajendra Singh et al, eds. The Yearbook of South Asian Language and Linguistics, 11–30. New Delhi: Sage Publications.

Amritavalli, R. 1998a. Kannada Clause Structure. Paper presented at GLOW in Hyderabad.

Amritavalli, R. 1998b. Tense, Aspect and Mood in Kannada. Paper presented at the Conference on the Syntax and Semantics of Tense and Mood selection, University of Bergamo.

Amritavalli, R. 1997. Copular sentences in Kannada. Paper presented at the seminar on null elements, Delhi University.

Amritavalli, R. 1977. Negation in Kannada. Master’s thesis, Simon Fraser University.

Amritavalli, R., and Jayaseelan, K.A. 2000 [2002]. Finiteness and Negation in Dravidian, ms., CIEFL. Included in CIEFL Occasional Papers in Linguistics 10, 1–42.

Caldwell, Robert. 1913. A Comparative Grammar of the Dravidian or South-Indian family of languages. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co., third edition.

Comrie, Bernard. 1976. Aspect. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Giannakidou, Anastasia. 1997. The Landscape of Polarity Items. Groningen dissertations in Linguistics 18.

Grimshaw, Jane. 1991. Extended Projection. ms., Brandeis University.

Hany Babu, M.T. 1986. The structure of Malayalam sentential negation. International Journal of Dravidian Linguistics 25.2: 1–15.

Jayaseelan, K.A. 1997. The serial verb construction in Malayalam. Paper at the Trondheim workshop on serial verb constructions.

Jayaseelan, K.A. 2001. IP-internal topic and focus phrases. Studia Linguistica 55.1:39–75.

Kayne, Richard S. 1994. The antisymmetry of syntax. Cambridge MA: MIT Press.

Kittel, F. 1908 [1982]. A Grammar of the Kannada Language. New Delhi: Asian Educational Services.

Laka, Ignatius M. 1990. Negation in Syntax: on the nature of Functional Categories and Projections. Doctoral Dissertation, MIT.

Lyons, John. 1968. Introduction to theoretical linguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Paradis, Johanne, and Crago, Martha. 2000. Tense and Temporality: A Comparison between Children Learning a Second Language and Children with SLI. Journal of Speech, Language and Hearing Research 43: 834–847.

Platzack, Christer. 1995. The Loss of Verb Second in English and French. In Adrian Battye and Ian Roberts, eds. Clause Structure and Language Change, 200–225. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Pollock, J.-Y. 1992. Notes on Clause Structure. Amiens: Universite de Picardie, ms.

Rapoport, Tova. 1987. Copular, Nominal and Small Clauses: a study of Israeli Hebrew. Doctoral dissertation, MIT.

Spencer, H. 1914. A Kanarese Grammar. Mysore: Wesley Press.

Stowell, Tim.1982. The tense of infinitives. Linguistic Inquiry 13.3:561–570.

Wexler, Ken.1994. Finiteness and head movement in early child grammars. In David Lightfoot and Norbert Hornstein (eds.) Verb Movement, 305–350. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.