K. A. Jayaseelan

This paper is an attempt to understand a very intriguing set of facts about the Dravidian languages, namely that clausal coordination, relativization and finiteness are in a relation of mutual exclusion. That is, finite clauses cannot be coordinated; relative clauses cannot be finite; and relative clauses cannot be coordinated. There are also other exclusions: a negative sentence is finite (except in a very restricted set of clause types), and therefore negative clauses cannot be coordinated or relativized. I offer an explanation of these facts by making a typological claim about the Dravidian C domain.1 The Dravidian C domain (I suggest) is less differentiated than the C domain of some European languages with respect to functional positions; in fact, apart from a high ForceP (which can be occupied by a question operator or a correlative operator), there is only one position in the Dravidian C domain. The coordination marker, the relativizer, and the elements that instantiate Mood—Mood being the realization of finiteness in Dravidian—must compete for this position. This would explain the mutual exclusions that we find in the Dravidian clausal periphery.

The claim that Dravidian has fewer positions in the C domain has an implication for how we conceptualize the universal functional sequence postulated by the cartographic studies of Rizzi (1997), Cinque (1999), Starke (2009) and others. We shall comment on this in Sect. 9.

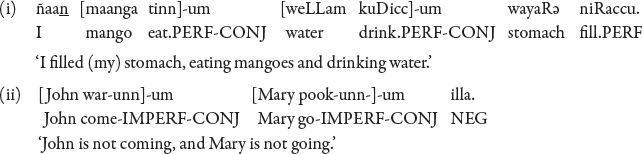

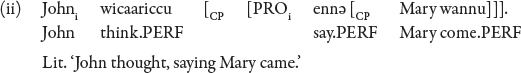

A long-standing puzzle in Dravidian languages is that they do not allow the coordination of finite clauses (Anandan 1993; Jayaseelan 2001:65, n. 1; Amritavalli 2003:3).

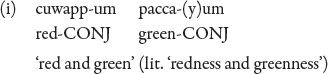

Consider coordination in Malayalam. The coordination markers of Malayalam are -um (for conjunction) and -oo (for disjunction); these forms have close cognates in the other Dravidian languages. The -um or -oo is suffixed to each conjunct or disjunct:

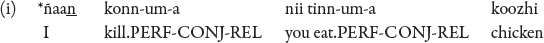

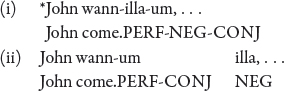

These markers cannot be suffixed to finite clauses to coordinate them.2

The way these meanings can be expressed in Malayalam is:

As (3a) shows, there is no problem coordinating nonfinite clauses. It is finiteness that is incompatible with coordination.

In traditional Dravidian linguistics it was customary to say that finiteness in Dravidian was not constituted by Tense but by Agreement (Steever 1988; Sridhar 1990; see also an overview of the traditional discussion in Amritavalli and Jayaseelan 2005: Sect. 1). The reason for the traditional view was that Tense seemed to appear in what were clearly nonfinite verb forms. Consider serial verbs, commonly called ‘conjunct verbs’. All the non-final verbs have an invariant ‘past tense’ form; they however have no past tense meaning (as noted in Jayaseelan 2004). Cf. (4):

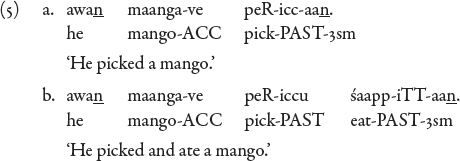

Now these invariant past tense forms are indistinguishable from the regular, meaningful past tense forms in Malayalam, because Malayalam—exceptionally among the Dravidian languages—has no agreement. But in other Dravidian languages the finite verb form is inflected for agreement. The nonfinite conjunct verbs have no agreement, although superficially they seem to have (Past) tense. Cf. the following Tamil sentences:

In (5b) peR-iccu has no agreement, as contrasted with peR-icc-aan in (5a).

Even in Malayalam, one can tell apart finite and nonfinite clauses by testing for the admissibility of modals; in Dravidian (and perhaps universally), a ‘true’ modal is possible only in a finite clause.3 The following sentence, containing a conjunct verb with a modal suffix -um (Future), is ungrammatical:4

Amritavalli and Jayaseelan (2005) (hereafter A & J) made a proposal about the paradox of ‘Tense’ in nonfinite clauses as follows: Dravidian has no Tense; what has traditionally been analyzed as Tense is Aspect.5 As we know, there can be Aspect in nonfinite clauses. (Stowell’s 1982 “tense of infinitives” is actually “aspect of infinitives.”) Finiteness in Dravidian is constituted by the presence of MoodP. In the indicative mood the head of MoodP is null, but the null head hosts an agreement matrix.6 This is why finiteness in the indicative mood is signaled by agreement—giving rise to the somewhat bizarre traditional claim that Agreement constitutes finiteness in Dravidian.

MoodP—distinct from, and above, TenseP—has been postulated even in the European languages. Thus, Pollock (1997:237) proposes that “the seldom recognized functional category of mood… should be the head of a MoodP, which… is the highest functional projection in French and Romance as well as Old, Middle and Modern English clauses.” What we see now in Dravidian is that Dravidian is less differentiated in this area of the universal functional sequence (‘fseq’). Whereas European languages have a MoodP and a TenseP, Dravidian has fewer positions in this area.7

We just saw that clausal coordination is incompatible with finiteness. An immediate solution that one might want to consider is to encode this fact as a selectional restriction of the coordination markers: they cannot select finite verb forms.8 But we now show that such a solution would fail in two ways. Firstly, it would be insufficiently general, because there is another element incompatible with finiteness; the selectional restriction will have to be ‘spread’ to this element too. Secondly, there is a type of nonfinite clause that cannot be coordinated, so one will have to say that the coordination markers cannot select finite clauses and even some nonfinite clauses.

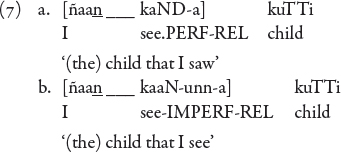

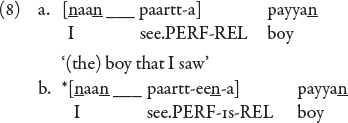

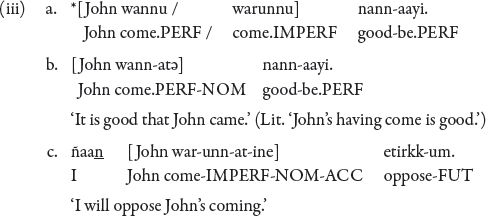

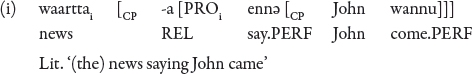

Consider the relative clause in Dravidian. Dravidian has a gap relative which is prenominal, and which has at its right edge a ‘relativizer’ -a:

The point of interest here is that the clause is nonfinite. Typologically, pre-nominal relatives tend to be nonfinite (see Keenan 1985:160; Kayne 1994:95). Consider the following Tamil data:

The agreement marker -een makes the relative clause in (8b) finite, thus it is ungrammatical.

In Malayalam one can demonstrate the non-finiteness of the relative clause by the ‘modal test’:

The relativizer -a is arguably a reduced form of the distal demonstrative aa ‘that’; we can tentatively take this -a to be a determiner (D0). (We shall later see corroborative evidence for this conjecture.) There is apparently a movement from the gap position to the clause-peripheral position, for the relation of the gap to the relativizer or the head noun shows island effects.9

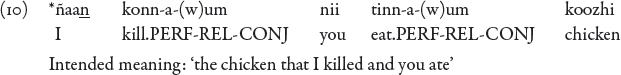

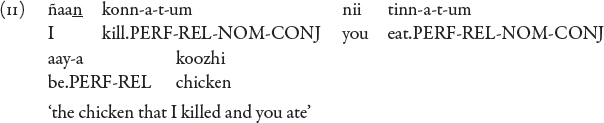

Not only is the relativizer -a incompatible with finiteness; we now note that it is incompatible with coordination. Relative clauses cannot be coordinated in Dravidian. This is unexpected, because we said that nonfinite clauses can be coordinated, and relative clauses are nonfinite. Consider (10):10

The way the intended meaning of (10) can be expressed is:

Here, the relative clause is nominalized: the -tA suffix is a 3rd person, singular agreement marker that plausibly agrees with a null nominal head.11 So what we are coordinating in (11) are two NPs. And since NPs cannot be directly predicated of the head noun, we need another verb, namely aay- ‘be.PERF’, which in turn has the relativizer -a that turns the structure into a relative clause.

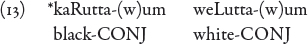

Most Dravidian adjectives are reduced relative clauses (Anandan 1985).12 Therefore they have the relativizer -a as a suffix:

These adjectives cannot be coordinated:

These adjectives have to be nominalized, exactly like the relative clauses, in order to be coordinated:

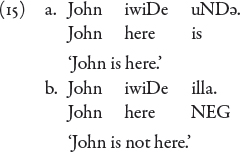

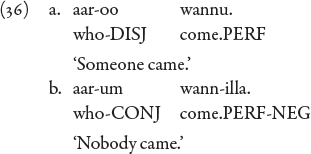

We now look at a third element which cannot co-occur with agreement or modal in Dravidian, namely Negation. The Neg element in Malayalam is illa; it has close cognates in the other Dravidian languages.16

The illa in (15b) is a finite verb which “negates existence” (Sridhar 1990:111); it is the negative counterpart of uNDә, an existential copula with a very defective paradigm.17

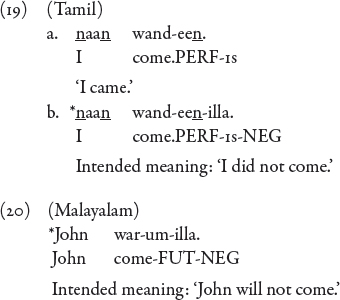

The illa illustrated in the (b) sentences of (16)–(18) below does not negate existence; however, it is still a finite, negative verb:

Illa can co-occur with nonfinite verb forms in the same clause, e.g., a participle (perfect or imperfect), cf. (16b) and (17b), or an infinitival, cf. (18b). But it cannot co-occur with an agreeing verb or a modal, because these are finite:

The intended meaning of (20) will be expressed in Malayalam as (18b), where the complement of illa is nonfinite.18

We said that it is the presence of Mood that makes a clause finite in Dravidian. The head of MoodP can be a modal; in the indicative mood this position is occupied by a null head hosting an agreement matrix. This is how an agreeing verb or a modal is the realization of finiteness. How does illa become finite? In A & J we analyzed illa as an element which is generated in the head of NegP and which raises to, and incorporates, the head of MoodP.19 Since illa incorporates the head of MoodP, neither a modal nor agreement can be generated in the latter position; this accounts for the mutual exclusion of illa, modals and agreement.

It is important to note that the case of illa is actually different from that of the relativizer -a or the coordination marker: while these last two elements are in complementary distribution with Mood, illa is the spell-out of ‘Neg+ Mood’ and in that sense ‘contains’ Mood.20

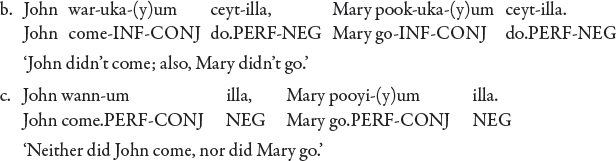

As is to be expected, since illa makes a clause finite, two illa clauses cannot be coordinated:

The intended meaning of (21) can be expressed in the following ways:

In the sentences of (22), -um is suffixed to nonfinite verb forms.21

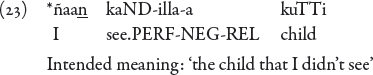

Again, since an illa-clause is finite, it cannot be relativized:

The way the intended meaning is expressed is by a construction in which the proto-Dravidian negative morpheme -aa appears; it shows up in the contemporary Dravidian languages only as an infix in nonfinite verb forms such as the negative gerund (A & J: 202):

Note that this relative clause is neutral with respect to tense interpretation; this is because there is no Aspect in it.23

Let us summarize the discussion so far. In Dravidian, finiteness and coordination are in complementary distribution. Similarly, finiteness and relativization are in complementary distribution. The negative element illa, which incorporates finiteness, is—as a corollary—in complementary distribution with coordination and relativization. Illa is also in complementary distribution with the other realizations of Finiteness, namely Agreement and Modal. Besides these mutual exclusions, coordination and relativization also exclude each other. That is, only one of the following can occur in the C domain (besides ForceP, see below):

A. MoodP (the realization of Finiteness), which in turn can accommodate only one of the following:24

B. Coordination marker, -um / -oo

Before we proceed, we must make clear that A, B, and C are not the only elements allowed in the Dravidian C domain. Malayalam has a question particle -oo (with close cognates in other Dravidian languages), which is homophonous with the disjunction marker -oo. In Jayaseelan (2001, 2012), I argued that the question particle -oo is the disjunction operator, not a disjunction marker; and it is generated high up in C, as the head of ForceP. Now, this question particle co-occurs with MoodP: thus it co-occurs with agreement in (25a) (Tamil data), with a modal in (25b), and with illa in (25c):

Similarly, Dravidian has a correlative construction, in which the correlative clause ends with a suffixal -oo. This -oo is the disjunction operator and is generated as the head of ForceP (Jayaseelan 2001); it also takes MoodP as its complement. Thus it co-occurs with agreement in (26a) (Tamil data), with a modal in (26b), and with illa in (26c):

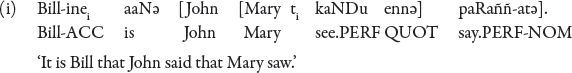

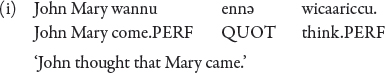

Malayalam also has a quotative complementizer ennә (with cognates in other Dravidian languages), which is historically derived from the perfective form of a verb enr- ‘say’. (This latter verb is obsolete in present day Malayalam, but is still a regular verb of Tamil.) There is reason to believe that ennә is outside CP. That is, it is still an inflected verb, which takes an object complement. Such an analysis makes ‘ennә-plus-clause’ an adjunct of the matrix clause. This ambiguous status of the complement clause is very clear in Dakhini Urdu which is heavily influenced by Dravidian syntax; cf. woh nahii aayegaa bolke bola, lit. ‘He said saying he will not come’.26

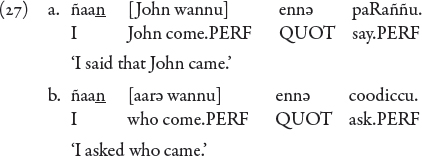

This ‘outside CP’ status of ennә explains two things. Firstly, unlike the English complementizers that and whether, ennә indifferently takes a declarative or interrogative complement, suggesting that it does not ‘inherit’ any feature from the embedded C; cf. (27):

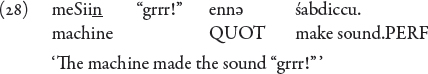

A second, and more telling, argument is that the object complement of ennә need not be a clause; cf. (28):

Here there is no C to lodge ennә in!27

In fact, if ennә is still functioning as a ‘say’ verb, it should not be surprising that its object argument can be a clause or just a quoted element, e.g., a sound; cf. the following English data:

But the point is that in either case, the ‘say’ verb is outside its object argument. Or more pertinently here, when the object argument is a CP, the ‘say’ verb is outside that CP.

I now wish to suggest that ennә, together with its object argument, is in itself a nonfinite clause, in fact a CP, and that it may have a PRO subject which is controlled by the matrix subject. (The PRO subject would be like the one we postulate in the clausal adjunct of an English sentence like: Heithreatened me, [PROisaying …].) While the ‘say’-meaning of ennә is bleached like in light verbs—thus in (28), the machine does not ‘say’ anything—its syntax as a verb is intact.28

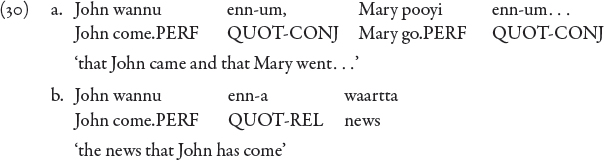

Why do we say that ennә + object argument is a CP? Its C domain is restricted: it cannot generate a MoodP (or the ennә clause would be finite), but it can accommodate either of the two other elements that can appear in the C domain of a nonfinite clause, namely the coordination marker or the relativizer:

(30b) is conclusive evidence that ennә + object argument is a CP; for the relativizer can appear only in the C domain.29

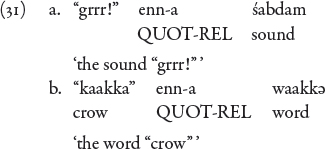

Note that (30b) is a noun complement construction; it contains no gap from which the relativizer -a could have been moved. This argues that the gap in the Dravidian relative clause is not the trace of the relativizer -a; it must then be the trace of the raised head-noun—lending support to the Vergnaud analysis of relative clauses (Vergnaud 1974; see also Kayne 1994; Cinque 2009). This conclusion is strengthened when we note that the relativizer can appear even when the complement of ennә is just a simple nominal element, cf. (31):

The suffixed -a (then) must be generated in situ.

Where exactly is the relativizer -a generated? In Kayne’s (1994: Sect. 8.2) implementation of the raising analysis of relative clauses, a phrase like ‘the picture that Bill saw’ has the structure and the derivation shown below:

Cinque (2009) has a variant of this analysis, in which the relative clause is generated pre-nominally as the specifier of an extended projection of the head. His structure for the above phrase would be:

In either analysis, we have a determiner the which takes a CP as complement; and the CP is headed by that and contains the relative-clause IP. Now, the relativizer -a cannot correspond to the determiner the; for one thing, the definite article in Dravidian is a null element. More importantly, it cannot be generated outside CP, or it would not be in complementary distribution with the MoodP of the CP. If anything, we can take it that the relativizer -a corresponds to that in the Kayne/Cinque analysis. (As we said earlier, it is plausible that the Dravidian relativizer is a reduced form of the distal demonstrative aa ‘that’.)30

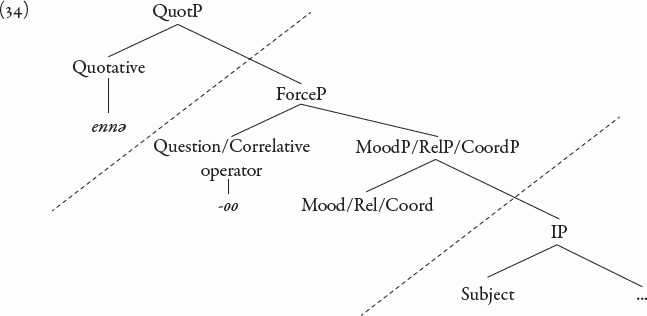

The picture of the Dravidian C domain and its environs that we have now obtained is (34):

There is a quotative complementizer when CP is embedded, which is outside CP. (What we have called ‘QuotP’ is actually an adjunct CP containing more structure, but we ignore this fact here.)

In the C-zone ‘proper’—below QuotP and above IP—there is a ForceP which can be occupied by the question or the correlative operator; both of these are realized as -oo. Below ForceP, I have shown just one position. I claim that there is only this one position below ForceP in the Dravidian C-zone, which Mood, the relativizer -a, and the coordination marker must compete for.

How do we understand this situation? Chomsky (2004, 2008) has suggested that C and T are not really independent categories, and that T’s features are ‘inherited’ from C (Chomsky 2008:143–144). We can conceptualize this in two ways: T can be generated as a ‘dummy’ head, which gets its features by inheritance from C. Alternatively, we can think of T as being generated as part of C, and of C projecting this part of itself downwards. There is no counter-cyclicity involved in this downward projection, as has been pointed out by Richards (2007), if we assume that all operations in a phase are simultaneous. A still different way of conceptualizing this is to think of C as ‘stranding’ T and then moving up; this does not involve downward projection.

Chomsky further suggests that Rizzi’s (1997) “left periphery”, consisting of Force, Topic, Focus, etc., is generated by “feature spread” from a single functional category, namely C (Chomsky 2008:143). That is, these functional heads too, like T, are ‘spread out’ from C; we can think of C as ‘hiving out’ its features both upward and downward, thereby allowing them to project their own phrases.

If we adopt the above Chomskyan position about C, we can identify the head that we labeled ‘Mood/Rel/Coord’ in (34) as simply ‘C’, and we can say that the Dravidian C is typologically different from the C of European languages. It does not ‘hive out’ any features except Force0. In a way of speaking, Dravidian has a ‘narrow’ left periphery.

Many things fall into place once we say this. A & J’s claim that Dravidian has no Tense appeared to be an ‘extreme’ claim, when taken in isolation. But now we can see this as an instance of the Dravidian C’s general ‘unwillingness’ to hive out positions.31

Dravidian languages have no wh-movement to a clause-peripheral position. If we assume that wh-movement targets Focus (Rizzi 1997), we can say that no Focus position is generated in the C domain. Indeed, if it had been, Focus would have competed for the single position below ForceP—excluding other ‘candidates’ for it, e.g., MoodP. Therefore, if Dravidian had wh-movement to the C domain, only nonfinite questions would have been possible.32

The relativizer -a, as we said earlier, appears to occupy a position analogous to that of the complementizer that of the embedded CP in Kayne’s (1994) and Cinque’s (2009) analysis of relative clauses. Generating it in the C domain excludes MoodP from it, wherefore only nonfinite relative clauses are possible.

The Dravidian coordination markers -um/-oo also function as conjunction/disjunction operators (see Jayaseelan 2001, 2012 for a fuller discussion of this). Consider (35):

Here, the clause-final -um in the adjunct conditional clause turns the question words aarә ‘who’ and entә ‘what’ into universal quantifiers.33 The coordination markers can also be directly suffixed to question words to turn them into quantifiers:

In fact, suffixing -um/-oo to question words is the standard way in which Dravidian languages make their quantifiers (see Jayaseelan 2011).

The English forms and/or, or Hindi aur/yaa, cannot similarly operate on question words to turn them into quantifiers. The obvious conclusion (it seems to me) is that there is a category difference here: whereas the English/Hindi forms are only coordination markers, the Dravidian forms are primarily operators, although they can also function as coordination markers as in (1)–(2).34

When the disjunctive -oo is functioning as the question/correlative operator, we saw that it can co-occur with finiteness (MoodP), and we accounted for this by saying that in these functions, it is generated in ForceP (see (34)). The question is: where is -oo/-um generated when it is coordinating clauses? Possibly, even in this function, it must be generated in an operator position.35 Let us hypothesize that there is an operator position which is below ForceP in the C domain. In Dravidian this would be the single position below ForceP in (34). When -um/-oo is generated in this position, it excludes MoodP from it; wherefore coordinated clauses are nonfinite in Dravidian. It also excludes the relativizer -a and the Neg illa; and therefore, relative clauses and illa-clauses cannot be coordinated.

I now wish to suggest that there may be other languages with a Dravidian-type C domain.

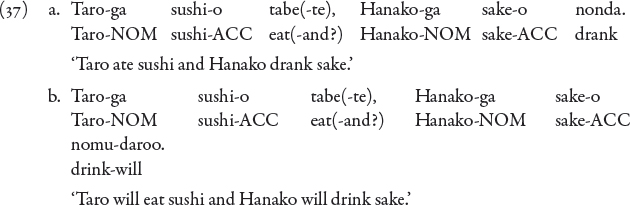

In Japanese, the coordination of finite clauses is done in the following way:36

The coordination marker is -te.37 It is attached to the first conjunct; and this conjunct is devoid of tense. The interpretation of tense depends on the second conjunct, which has no -te marker and has tense. Superficially speaking, the coordination marker ‘knocks off’ tense.

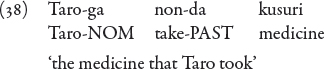

The Japanese relative clause is described by Keenan (1985:161) as a typological exception: whereas pre-nominal relatives are typically nonfinite, the Japanese relative clause appears to be finite. Consider (38) (example adapted from Haraguchi and Shuhama 2011):

But there is a problem with respect to the occurrence of modals in relative clauses, a fact pointed out by Haraguchi and Shuhama (2011). These authors make a distinction between two types of modals in Japanese: G(enuine)-modals and Q(uasi)-modals. They suggest that only G-modals are in the CP-zone, the Q-modals being low in the clausal structure and contained inside TP. Now, G-modals are disallowed in relative clauses, although Q-modals are fine. Cf. (39) (examples adapted from Haraguchi and Shuhama 2011):

Why is a ‘genuine’ modal disallowed in a relative clause? Going by the ‘modal test’ that we applied in Malayalam, we must conclude that the Japanese relative clause is not fully finite.

Japanese linguists have tried to explain the restrictions on the relative clause by appealing to the idea of ‘truncation’. Murasugi (1991) proposed that Japanese relative clauses are TPs, without a CP layer. The Haraguchi-Shuhama explanation of the distribution of G- and Q-modals accords well with this idea. However there is a problem if we assume that Tense is inherited from C: how does the relative clause get tense?

An alternative might be to pursue the idea of ‘paucity of positions’, which we found necessary to appeal to in the case of Dravidian.

In the elaboration of functional heads that we witnessed in the cartographic investigation of languages, there was apparently an implicit assumption that the functional heads in any syntactic domain ought to form a linear ordering. In fact, the term ‘functional sequence’ seems to imply this. The paradigm example of such an ordering is Cinque’s (1999) enumeration of the functional heads in the clausal domain.

Given that functional sequences are intended to be universal, one might ask where we should look for a space, or spaces, for parametric variation. One possibility is that a language may choose not to include a certain head in its repertoire; this would be analogous to a language selecting its sounds from Universal Phonology. Another possibility is a proposal in Nanosyntax (Starke 2009), which seeks to locate parametric variation in the mapping from pre-lexical syntax to the lexicon: a lexical item of one language may spell out a different ‘stretch’ of the functional structure—overlapping but non-coterminous—as compared to the ‘corresponding’ lexical item of another language. Neither of these ways of interacting with the universal functional sequences disturbs the linear ordering of the functional heads.

But our proposal in this paper appears to require such a radical move. Our proposal is about the obligatory non-co-occurrence of the heads in a certain stretch of the clausal functional sequence, namely the left periphery. Prima facie, this seems to require for its representation a branching structure, rather than a linear ordering, for this part of the fseq—just for these languages.

However I wish to suggest that the right solution is not to radically manipulate the fseq for these languages. Even as there is a mapping from functional structure to lexical items such as Nanosyntax postulates, there is possibly another point of articulation in the grammar, namely a mapping from functional heads to syntactic heads. This mapping too—like the mapping to lexical items—can be a many-to-one mapping. If we grant this, the linear ordering of functional sequences can remain undisturbed.

An important typological question that remains to be addressed is why the ‘compression’ of the C domain—the many-to-one mapping in this area—appears to show up in head-final languages (if my impression is correct).

This paper was presented at LISSIM-V at Kangra (Himachal Pradesh, India) (May 2011), at a conference on Finiteness in South Asian Languages at the University of Tromsø (June 2011), and at a conference on Syntactic Cartography at the University of Geneva (June 2012). I wish to thank the audiences at the three venues for helpful feedback. Thanks to R. Amritavalli for discussions and comments during the writing of the paper. And I am thankful to Rajesh Bhatt, the official commentator for this paper for this volume, for the very insightful comments and feedback he provided, which have been of very great help to me.

1. By ‘C domain’, I mean Rizzi’s (1997) “left periphery,” which is above IP and can include many functional heads. Chomsky (2008:143) claims that all the functional heads in this structural space are generated by “feature spread” from the phase head C.

2. We illustrate only conjunction, but what we say about conjunction here is equally applicable to disjunction. The question particle -oo, which is homophonous with the disjunction marker, can be used in a finite clause, as we show later.

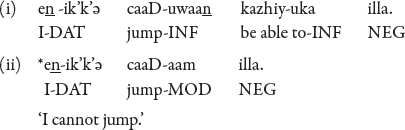

3. I am distinguishing ‘true’ modals, which belong to the syntactic class of ‘modal’, from verbal expressions which only have a modal meaning. In English, we can distinguish ‘can’ from ‘be able to’ (signifying ability), or ‘will’ from ‘be going to’ (signifying future eventuality). In Malayalam, -aam (a verbal suffix) is a true modal, signifying possibility/permission/ability; whereas kazhiy- ‘be able to’ is not a modal at all. The latter, but not the former, can occur as the complement of the finite negative element illa (see Sect. 5):

4. The future marker -um is a modal in Malayalam (Hany-Babu 1997).

5. A weaker claim would be that tense and aspect morphemes are homophonous in some cases, and that in contexts where ‘tense’ morphemes seem to appear in nonfinite verb forms, what we actually see are aspect morphemes. While such a solution will serve the case of conjunct verbs, it is insufficient to deal with the facts of Kannada negation. See also fn. 7. But let me also note that the issue of whether Dravidian has Tense or not is not crucial for us; what is crucial is the claim that finiteness is constituted by MoodP.

6. Recall that there is an agreement matrix on Tense in English in the indicative mood. Could this agreement matrix actually be on the head of MoodP, and not TP, even in English (as suggested by A & J:216–217, n. 21)? In other words, could the AgrP above TP of early minimalism actually be the MoodP?

7. Would there be any point in postulating an abstract TenseP in Dravidian, to bring it in line with the functional sequence of European clause structure? The question is discussed in A & J. One will have to say that its head, T0, is phonologically null, but can be marked for the feature [+Past/−Past]. But note that since the tense interpretation will be determined entirely by the perfective/imperfective—i.e., aspectual— choice (see A & J for details), T0 will in effect make no semantic contribution; or in other words, it will be doing no work. A & J also point out that a null functional head which is optionally marked for opposite values—[+Past/−Past]—may constitute a learning problem.

8. In fact, Anandan (1993) suggested that the coordination markers of Malayalam select only [-V] categories. This suggestion would of course have an immediate problem with the coordination of infinitival verb forms like in (3a)—unless one can maintain that infinitivals are nominal. See also fn. 15.

9. We shall later show that it cannot be the relativizer that moves from the gap position, so what moves must be the head noun (as per the prediction of the ‘head-raising’ analysis of relative clauses, cf. Vergnaud 1974; Kayne 1994; Cinque 2009).

10. Changing the order of relativizer and conjunction marker does not ‘save’ the sentence:

11. See Jayaseelan and Amritavalli (2005) for an account of the nominalization of relative clauses in Dravidian. Typical examples of this are free relatives; cf. (i). Note that the nominalized relative clause is case-marked.

12. Whether Dravidian has Adjective as a lexical category is a much-debated question. See Amritavalli and Jayaseelan (2003) for a discussion of this question.

13. The stems are perfective forms of verbs, most of which are functioning verbs of the contemporary language—although some of the verbs have become obsolete. Thus, kaRutt is the perfective form of kaRukk- ‘to become black’.

14. There are a few ‘adjectives’ which are actually nouns (as Anandan 1985 notes). These can be coordinated:

Adverbs and PPs can be coordinated, cf. (ii) (adverbs) and (iii) (PPs):

The ‘postpositions’ in (iiia) are clearly case-marked nominal elements; the one in (iiib) is verbal—it is the perfective form of the verb patt- ‘to adhere or stick’. The ‘adverbs’ in (ii), uRakke ‘loudly’ and patukke ‘slowly’, seem to be derived from verbal roots (now obsolete). So in effect, in (ii) and (iii), we are only looking at the coordination of nominal and verbal forms.

15. For the sake of completeness of data we note that all nonfinite verb forms can be coordinated. We have already seen the coordination of the verb form -uka in (3a). In (i) below we see the perfective verb form of nonfinite adjuncts being coordinated; and in (ii) we see the coordination of the imperfective verb form:

These verb forms are not nominal—i.e., they are not verbal nouns—for they cannot occur in an argument position or bear case unless they are first nominalized:

Taking stock, it might be simpler to say that all categories that can be coordinated in English can be coordinated in Malayalam—except finite clauses and relative clauses (and as a subcase, adjectives).

16. See A & J, Sect. 4 for a fuller treatment of illa.

17. The language also has a copula of predication—commonly called the ‘equative’ copula—aaNә; it is negated by alla, cf. (i):

Since alla has all the properties of illa, we will not give it a separate treatment.

18. The negation of modals in Dravidian is a complicated question, which we will not go into here. See Hany-Babu (1997) for a preliminary discussion.

19. The head of MoodP that it incorporates is the head of indicative mood which is null.

20. Actually, A & J distinguish three illas in Dravidian, only two of which incorporate Mood. The third illa (their illa3) incorporates an existential verbal root and negation, and stays well within IP. (We illustrate this illa presently.)

21. One might ask: what accounts for the grammaticality contrast between (21) and (22c)? (Their first conjuncts are repeated below.) Superficially, they show just a change of order between -um and illa.

The answer must be that the -um in (ii) is not in the C domain, but is generated in a lower position. I suggest that it is generated above the Aspect Phrase that hosts the perfective aspect. (The -um in (22a) and (22b) also must be in a lower position than the C domain.) But in (i), -um does not have that option, because it is above illa which is in the C domain. And the ‘narrow C domain’ of Dravidian cannot accommodate both these elements (as we argue below).

But why doesn’t a similar change of order between -um and -a rescue sentence (10), as was shown in fn. 10? We repeat the relevant sentences below as (iii) and (iv):

In (iv), if -um is generated above Aspect Phrase, it should not prevent the generation of -a in the C domain. The only solution I have at present is a morphological restriction: -a apparently needs to be directly affixed to an aspect head without any intervener; whereas illa, by contrast, is an independent word.

22. The -tt—glossed as ‘?’—is an augment of uncertain function; possibly it is an aspectual suffix which has lost its aspectual meaning.

23. For some reason, negation by -aa is possible only when the verb is not a copula. If the relative clause is a copular clause, its negation is done by using illa3, the nonfinite illa (see fn. 20); cf. (i):

Since this illa stays within IP, it does not ‘interfere’ with the appearance of the relativizer -a in C.

24. Since agreement is a reflex of indicative mood, and indicative mood and ‘true’ modals are in complementary distribution universally, the non-co-occurrence of Agreement and Modal is not surprising. What is peculiar to Dravidian is that Neg incorporates Mood.

25. The Tamil and Kannada question particle is -aa, not -oo; and even in Malayalam, in the colloquial language of certain parts of Kerala or certain social classes, both the disjunction marker and the question particle are realized as -aa. (This change does not happen with the correlative -oo discussed below, obviously because the correlative construction is used only in formal language.)

26. We need to note that ennә clauses also show some complement-like behavior. Thus they allow subextraction in the cleft construction (as shown at length in Jayaseelan and Amritavalli (2005)):

Also, pronominals in the ennә clause can be like in indirect speech:

27. The traditional analysis of ennә is that it is a ‘say’-verb which has been grammaticalized as a complementizer. But a complementizer needs a clause as its complement. In (28), or in the sentences of (31) (below), ennә does not have a clausal complement, just an NP complement.

28. The analysis I am suggesting will give the sentence (i) the underlying structure shown in (ii).

Kaynean ‘roll-up’ (Kayne 1994), which moves the object argument to the left of the verb, will give us the surface word order. The point to note is that ‘ennә + object argument’ is itself a CP—more specifically, a nonfinite adjunct CP.

29. The structure of (30b) would be (i) (abstracting away from roll-up movements):

30. The Malayalam data lend support to Kayne’s (2010) claim that the category Noun does not project, and that all the elements which have traditionally been analyzed as nominal complements are relativization structures. If relativization structures are necessarily clausal, the Malayalam data support that claim too: a Malayalam noun takes either a straightforward relative clause, or an ‘ennә + -a’ structure—and we claimed that ennә together with its object argument is a CP.

31. A reviewer queries: are we saying that the Tense head still exists in C, but is collapsed with the Mood head? Or are we saying that in Dravidian, Tense is truly missing?

An answer to this question is already touched on in fn. 7. We can add the following: In languages which clearly have a Tense head, two functions are usually attributed to Tense, namely anchoring (which is the same as finiteness) and temporal interpretation. In Dravidian, temporal interpretation is completely determined by Aspect. And finiteness is dependent on the presence of Mood. Therefore it is difficult to imagine what function an ‘implicit’ Tense in C can have in Dravidian. The fact is that Tense is never projected in Dravidian. What happens to a feature of C—e.g., Focus—when it is not projected? It is simply not there!

32. Malayalam moves its wh-phrases to a Focus position above vP; see Jayaseelan (2001, 2010). The question operator in ForceP interprets wh-phrases in this vP-peripheral position; see Jayaseelan (2012).

33. The conditional clause is nonfinite as can be determined by our tests. Therefore -um is taking a nonfinite complement here, as we should now expect.

34. But there was a historical stage of English in which or was used as a question particle, a fact which argues that it was then a disjunction operator generated in ForceP; see Jayaseelan (2012).

35. In this function, it of course does not have the option of being generated in ForceP, for this would yield the wrong semantics. There is a residual question—why should it be generated in an operator position when it is not an operator but only a coordination marker? I have no good answer to this at present.

36. I wish to thank Miyamoto Yoichi for kindly providing the data, and for discussing the data.

37. About this marker, M. Yoichi says: “some people translate it as ‘and’; but I am not sure that is really the case.”

Amritavalli, R. 2003. Question and negative polarity in the disjunction phrase. Syntax 6(1): 1–18.

Amritavalli, R., and K. A. Jayaseelan. 2003. The genesis of syntactic categories and parametric variation. In Proceedings of the 4th GLOW in Asia 2003: Generative grammar in a broader perspective, ed. Hang-Jin Yoon, 19–41. The Korean Generative Grammar Circle.

Amritavalli, R., and K. A. Jayaseelan. 2005. Finiteness and negation in Dravidian. In The Oxford handbook of comparative syntax, eds. Guglielmo Cinque and Richard Kayne, 178–220. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Anandan, K. N. 1985. Predicate nominals in English and Malayalam. M.Phil. dissertation, CIEFL, Hyderabad.

Anandan, K. N. 1993. Constraints on extraction from coordinate structures in English and Malayalam: An ECP approach. Ph.D. dissertation, CIEFL, Hyderabad.

Chomsky, Noam. 2004. Beyond explanatory adequacy. In Structures and beyond: The cartography of syntactic structures, ed. Adriana Belletti. Vol. 3, 104–131. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Chomsky, Noam. 2008. On phases. In Foundational issues in linguistic theory: Essays in honor of Jean-Roger Vergnaud, eds. Robert Freidin, Carlos P. Otero, and Maria Luisa Zubizarreta, 133–166. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Cinque, Guglielmo. 1999. Adverbs and functional heads: A cross-linguistic perspective. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cinque, Guglielmo. 2009. Five notes on correlatives. In Universals and variation: Proceedings of GLOW in Asia VII, 2009, eds. Rajat Mohanty and Mythili Menon, 1–20. Hyderabad: The EFL University Press.

Hany-Babu, M. T. 1997. The syntax of functional categories. Ph.D. dissertation, CIEFL, Hyderabad.

Haraguchi, Tomoko, and Yuji Shuhama. 2011. On the cartography of modality in Japanese. Poster presented at GLOW in Asia workshop for young scholars, Mie University, Japan, 7–8 September 2011.

Jayaseelan, K. A. 2001. Questions and question-word incorporating quantifiers in Malayalam. Syntax 4(2): 63–93.

Jayaseelan, K. A. 2004. The serial verb construction in Malayalam. In Clause structure in South Asian languages, eds. Veneeta Dayal and Anoop Mahajan, 67–91. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

Jayaseelan, K. A. 2010. Stacking, stranding, and pied-piping: A proposal about word order. Syntax 13(4): 298–330.

Jayaseelan, K. A. 2011. Comparative morphology of quantifiers. Lingua 121(2): 269–286.

Jayaseelan, K. A. 2012. Question particles and disjunction. Linguistic Analysis 38(1–2): 35–51.

Jayaseelan, K. A., and R. Amritavalli. 2005. Scrambling in the cleft construction in Dravidian. In The free word order phenomenon: Its syntactic sources and diversity, eds. Joachim Sabel and Mamoru Saito, 137–161. New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

Kayne, Richard. 1994. The antisymmetry of syntax. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Kayne, Richard. 2010. Antisymmetry and the lexicon. In Comparisons and contrasts, 165–189. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Keenan, Edward L. 1985. Relative clauses. In Complex constructions. Vol. 2 of Language typology and syntactic description, ed. Timothy Shopen, 141–170. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Murasugi, Keiko. 1991. Noun phrases in Japanese and English: A study in syntax: Learnablility and acquisition. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Connecticut.

Pollock, Jean-Yves. 1997. Notes on clause structure. In Elements of grammar: Handbook of generative syntax, ed. Liliane Haegeman, 237–279. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

Richards, Marc. 2007. On feature inheritance: An argument from the phase impenetrability condition. Linguistic Inquiry 38(3): 563–572.

Rizzi, Luigi. 1997. The fine structure of the left periphery. In Elements of grammar: Handbook of generative syntax, ed. Liliane Haegeman, 281–337. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

Sridhar, S. N. 1990. Kannada. London: Routledge.

Starke, Michal. 2009. Nanosyntax: A short primer to a new approach to language. In Nordlyd 36.1, special issue on nanosyntax, eds. Peter Svenonius, Gillian Ramchand, Michal Starke, and Knut Tarald Taraldsen, 1–6. Tromsø: CASTL. http://www.ub.uit.no/baser/nordlyd/.

Steever, Sanford B. 1988. The serial verb formation in the Dravidian languages. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass.

Stowell, Timothy. 1982. The tense of infinitives. Linguistic Inquiry 13: 561–570.

Vergnaud, Jean-Roger. 1974. French relative clauses. Ph.D. dissertation, MIT.