R. Amritavalli

The notion Tense plays a role in at least the following assumptions in current syntactic theory.

A. Clauses are finite because they are tensed. Tense anchors the sentence in time. In matrix clauses, Tense anchors the sentence to the speech (or utterance) time (Enç 1987; Stowell 1995).

B. Nominative case marking on subjects is a reflex of finiteness, i.e. of a tensed clause.

C. Finite (tensed) clauses require a subject, either overt or pro. Hence control, i.e. the presence of PRO, is a reflex of the non-finiteness (lack of tense) of a clause.

D. Semantic theories of tense require a syntactic Tense node.

The claim in (A), the Anchoring Condition of Enç (1987:642), requires that in all languages, “in main declarative clauses … events must be anchored to the utterance or some other salient reference point.” Event anchoring is what is identified as “finiteness,” or the ability of a clause to “stand alone.” It is usual to assume that the anchoring in question is temporal anchoring (of the event time to speech time, via a reference time); and that its syntactic reflex is tense. In the generative tradition, this assumption is attributed to Stowell (1995), but it is in fact a traditional assumption, as the discussion in Comrie (1976:1–2) shows. Finite clauses are described as carrying “independent tense” or “absolute tense,” which is “deictic,” because it locates “the time of a situation relative to the situation of the utterance” (loc. cit.); non-finite clauses with participial morphology (-ing, -en) are considered to instantiate “relative tense” (i.e., relative to the finite predicate).

Assumption (A) is challenged by the Dravidian languages. Amritavalli (2000) and Amritavalli and Jayaseelan (2005) have argued that in Kannada, and in Dravidian more generally, the finite or “anchoring” element is not the element that has a temporal interpretation (“Tense”), but Mood. What is currently seen as Tense must be understood as a complex of features with two functions: event anchoring or finiteness, and temporality and tense interpretation; and these features need not always occur together on one element.

A similar claim, that “event anchoring does not need to proceed temporally,” was made at about the same time by Ritter and Wiltschko (2005) (and later elaborated in Ritter and Wiltschko 2009) for the Salish language Halkomelem and the Algonquian language Blackfoot, both indigenous to North America. These authors describe anchoring by location in Halkomelem Salish, and by person in Blackfoot.

Landau (2004) addresses the claim in (C), which also impinges on (B), under the assumption that PRO and lexical subjects are in complementary distribution. Landau’s system, motivated by data from the Balkan languages, allows semantic tense to licence nominative case marking, i.e. a lexical subject, in non-finite clauses. His “calculus of control” decomposes finiteness into features of tense and agreement located in I0 and C0, and distinguishes two types of tense in non-finite clauses: “dependent tense” and “anaphoric tense.” Dependent tense is the presence of semantic tense (whether as a tense operator or a tense predicate) in morphosyntactically untensed complement clauses that project an independent tense domain. This is actually a proposal familiar from Stowell (1982). Dependent and anaphoric tense are both distinguished from the tense of “the indicative, which is completely independent” (op. cit.: 831). Landau’s proposals do not pertain (therefore) to matrix tense as a finiteness or anchoring element.

Mandarin Chinese has long been recognized as a language with no morphosyntactic tense (see, e.g., Comrie 1976). Analyses of Chinese in the generative tradition sometimes assume a null occurrence of syntactic Tense, in accordance with assumption (D). Lin (2006, 2010) however argues that Chinese is a truly tenseless language, although Chinese sentences in isolation have a clear tense interpretation.

Taken together, these papers in the last decade or so suggest a rich research agenda driven by data from very diverse languages for unpacking the construct Tense with respect to the assumptions (A–D) set out above. While the papers differ in their foci, and the languages under investigation also appear to differ considerably among themselves, there are nevertheless tantalizing glimpses into how these languages answer the questions of event anchoring, tense interpretation and the licensing of subjects very differently than we currently expect.

In this paper I situate the data from Dravidian against this perspective, adding to the original argument in Amritavalli and Jayaseelan (2005) both empirically and substantively, and pointing where appropriate to parallels and differences with other languages or analyses. In Sect. 2, I present the facts about negative clauses in Kannada, which superficially look quite different from affirmative clauses. Root negative clauses (and embedded finite negative clauses) present as infinitives or gerunds; their aspectual specifications give the negative clause its observed tense interpretations (Sect. 2.1). Since Kannada distinguishes finite from non-finite clauses, the question arises what licenses negative non-finite clauses in matrix (and embedded finite) contexts. A preliminary answer is proposed in Sect. 2.2: the neg element is the licensor. Section 3 argues for separating anchoring, and therefore finiteness, from tense. Section 3.1 attempts to force Tense in negative clauses by endowing the licensing neg with tense features and using Landau’s categories of anaphoric and dependent tense for the complement; but these notions turn out to be irrelevant to it. Section 3.2 proposes that the Kannada clause is anchored by a MoodP that hosts one of three elements: agreement (a reflex of indicative mood), a neg element illa that incorporates indicative mood, or a modal. I suggest that agreement and illa are merged as heads of a PolarityP; the verbal complements they select accord with their polarity specifications, hence the superficial dissimilarity of affirmative and negative clauses in Kannada.

In Sect. 4, the proposed clause structure is generalized to Tamil, Telugu and Malayalam; the subtle differences these languages show in their instantiation of the Dravidian clause structure are discussed. The case of Malayalam, of particular interest because it lacks agreement and has an apparently straightforward pattern of negation, is discussed in Sect. 4.2. Section 4.3 discusses some problematic instances of nominative case assignment (to be now seen as a reflex of finiteness rather than tense) that persist even when Landau’s proposal for dependent tense is adopted. Section 5 is the conclusion.

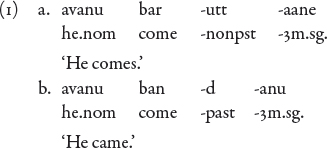

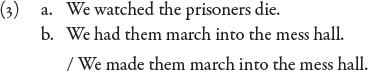

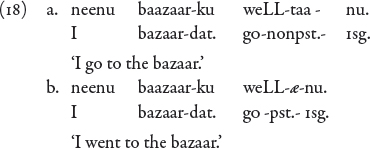

A striking fact about negative clauses in the Dravidian language Kannada is that they appear to be completely different syntactically from affirmative clauses. Affirmative verbs are overtly marked for person, number and gender agreement, and what appears to be a tense morpheme, which is homophonous with an aspect morpheme. (This homophony is familiar from the regular verbs in English, which do not morphologically distinguish past tense verb forms from perfect forms.)

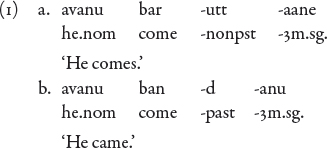

In the corresponding negative sentences, the verb form is a matrix gerund (2a) or a matrix bare infinitive (2b). The gerund plus neg illa is interpreted as the negation of non-past tense, and the infinitive plus neg illa as the negation of past tense. Neither tense nor agreement morphology occurs. The verb forms in (2) are therefore indifferent to the person, number or gender of the subject. The subject occurs in the nominative case, as shown by the pronominal forms that are drawn from the nominative paradigm, and the zero case realization on the lexical noun manuSHyaru ‘men’.

For Amritavalli and Jayaseelan (2005) (henceforth A&J), the negative forms in (2) invited two questions:

i. How is tense “read off” the non-finite verb forms?

ii. How is the matrix gerund or infinitive licensed?

We may here ask a third question:

iii. How is the subject case marked nominative?

The first question is discussed at length in Amritavalli (2000), and the discussion is reiterated in A&J. The gerund paradigm in Kannada offers a contrast of three aspectual forms: imperfect, perfect, and negative. The gerund that occurs in the matrix negative in (2a) has morphology that carries imperfect aspect, which must be interpreted as non-past tense.

As for the infinitival in (2b), there is no overt marking in it for either tense or aspect. Nevertheless, in view of Stowell’s (1982) proposal that English purposive infinitives have a tense operator specified as “unrealized,” it is conceivable that the infinitival hosts a tense operator. However, this operator cannot in (2b) be identical with the “unrealized” tense operator of purposive infinitives: (2b) has a past tense interpretation, not a future interpretation.

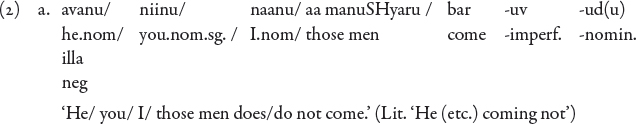

Addressing this problem, Amritavalli (2000) motivates a distinction between bare and case-marked infinitives, showing that purposive infinitives in Kannada, as in English, are specified as “unrealized;” but that these infinitives are case-marked infinitives. Bare infinitives, on the other hand, have a perfect interpretation, whether in the Kannada negative (2b), or in English (data from Akmajian 1977):1

This part of the analysis, then, countenances the possibility mooted in Stowell (1982) of tense operators in non-finite clauses, and adds content to it.

In sum, the answer to question (i) above offered in Amritavalli (2000) is that the specification of imperfect and perfect aspect in the verb forms of negative clauses in Kannada is what gives them their observed tense interpretations. Interestingly, precisely such an account of tense interpretation in Chinese has been offered in Lin (2006). Lin (2010:314) sums up his approach: “a tenseless analysis such as mine … employs aspectual properties of sentences to account for the temporal interpretations. Very briefly … perfective (bounded) event descriptions obtain a past interpretation by default and imperfective (unbounded) event descriptions obtain a present interpretation by default.”2 This establishes a precedent for the possibility of handling in the semantics the problem of tense interpretation in the Kannada negative clause in the absence of morphosyntactic Tense.

We have seen that root non-finite negative clauses in Kannada have reliable tense interpretations that appear to be grounded in their aspectual specifications. Note (however) that the anchoring question for (2) still remains: How is the matrix gerund or infinitive licensed in negative clauses? The presence of semantic tense or an independent tense domain in a non-finite clause does not suffice to render it finite. Thus Stowell does not claim that non-finite purposive complement clauses are finite, or licensed as main clauses; and Landau distinguishes dependent tense from the tense of “the indicative, which is completely independent.”

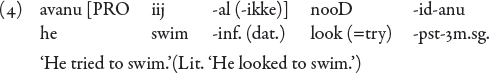

The tense interpretation of purposive infinitives and dependent tense complements is with reference to their matrix predicates, not with reference to utterance or speech time. In Kannada, too, purposive (case-marked) infinitive complements have an unrealized interpretation (as noted in the preceding section) with respect to the matrix predicate:

The swimming in the infinitive complement to try is unrealized with respect to a past event of trying, and not with respect to utterance or speech time.

What distinguishes the “relative tense” interpretation of the non-finite clause in (4) from the “independent tense” interpretation of the non-finite negative clauses in (2)? There must be an element in (2), other than the non-finite verb, that anchors the sentence in the world of the utterance: a deictic element that renders the clause finite. It must be this element that the tense interpretation in (2) references. To identify this element would also be to answer the question of what licenses the matrix gerund or infinitive in (2).

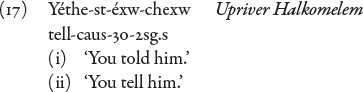

Before we proceed to do so, we must first consider and dismiss for Kannada a possibility that has been raised in the literature: that some languages may simply fail to distinguish finite from non-finite clauses. Such a claim was at first made for Halkomelem, which was said to “strikingly … not have infinitives” (Ritter and Wiltschko 2005:345), and to make use of a finite subordinate clause with subject agreement where English requires an infinitive.3 In the same vein, Lin (2010) argues for the possible lack of a finite versus non-finite distinction in Chinese. Lin retains the assumption that finiteness is a property tied to a syntactic Tense node. Consequently, if Tense is absent in this language, the finite/non-finite distinction must also arguably be absent.4 But if (as I argue) finiteness is not inevitably linked to Tense—if “event anchoring does not need to proceed temporally,” as Ritter and Wiltschko (2005) put it—the absence of Tense in a language does not entail the obliteration of the finite/non-finite distinction in it.

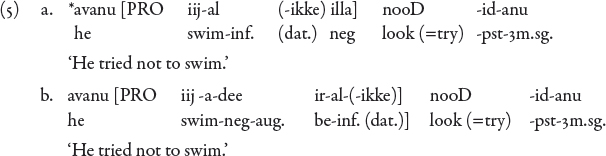

Kannada verb forms are clearly morphologically differentiated as tensed/finite and non-tensed/non-finite forms, as a comparison of (1) above with (2) or (4) shows. Secondly, control or the presence of PRO (and the prohibition of lexical subjects) is seen primarily in infinitives like the complement to the try class of verbs in (4), which therefore pass the classical test for non-finiteness. Thirdly, negation assumes different forms in non-finite and finite clauses, and therefore serves as a diagnostic for finiteness. The non-finite complement in (4) cannot be negated by illa (5a). It must be negated by the morpheme -a (5b).5

What we need in Kannada, therefore, is a three way distinction between finite affirmative clauses that are apparently “tensed” and have agreement morphology, e.g. (1), bona fide non-finite clauses such as the infinitive complement (4), and negative matrix clauses that have morphologically non-finite verb forms with no identifiable tense morphology, but are nonetheless finite and have an “independent tense” interpretation.

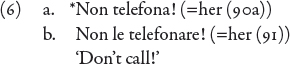

Returning now to the problem of how a matrix non-finite clause could be licensed, there is one other such instance documented, and that is the imperative in Italian (Zanuttini 1991). The Italian “true imperative” verb form occurs only in the 2nd person singular. (Elsewhere in the imperative, the indicative form of the verb occurs.) The “true imperative” verb form is not licit in the negative (6a). The verb form that must occur is the infinitive (6b), a “prima facie surprising construction.”

Two solutions have been proposed for the matrix infinitive (6b). Kayne (1991) suggests that the negative licenses an empty modal, which in turn licenses the infinitive. Zanuttini (1991:80) however suggests that the negative non needs to be licensed by TP, and that non is illicit in (6a) because true imperatives lack a TP. The infinitive in (6b) has “some inflectional morphology,” i.e. -re. Zanuttini allows this morphology to occupy a TP, and stipulates that this morphology, traditionally specified as [-tense], suffices to temporally anchor the clause to the utterance, and to license the negative.

The problem with extending such a solution to the Kannada negatives in (2) is obvious. If non-finite morphology can anchor a clause, what would distinguish the negatives in (2) from the non-finite complement in (4)? The Kaynean solution is more general: modals render a clause finite (although they are not “tensed”), and take non-finite verb complements—even in a language like English. To anticipate a little, the Kaynean insight into (6b) renders a little less outlandish the claim that in Kannada, and in Dravidian more generally, the anchoring element is Mood and not Tense, and that the mood head takes a non-finite complement.

Negative clauses in Kannada occur not only as root clauses but as finite embedded clauses. All finite clauses can occur in embedded contexts where they are introduced by the finite complementizer anta (formally, endu; literally, a perfect participle of the verb ‘say’).6 The illa negative clauses occur in this environment, arguing (again) that they are finite:

Clearly, negative non-finite clauses that occur in finite contexts, whether root or embedded, must be licensed by neg illa. Classical grammars of Kannada (such as Kesiraja’s SabdamaNi darpaNam) have called illa a kriyaatmaka-avyaya, i.e. a verb-like indeclinable (Amritavalli 1977:12, and note 5). We have noted that illa is excluded from non-finite complements (cf. (5a)); this argues that illa incorporates finiteness.

The observation that finite neg illa may be a defective verbal element invites the following question. Is there after all a covert tense in (2) and (7), which does not manifest itself due to the morphological defectiveness of illa? This solution would allow Kannada to fit in with existing assumptions about the absolute necessity of Tense in clause structure. A covert [−past] feature on illa in (2a/7a) could select a gerundive complement, and a covert [+past] feature on illa in (2b/7b) could select an infinitive complement. The selection could be taken as non-arbitrary and therefore learnable in view of the tense interpretations of non-finite clauses that I have argued for above. Let us pursue the implications of this technical solution (which we shall reject), which (we shall see) also bears on the proposals in Landau (2004).

Our attempt is to say that the non-finite complements in (2)/(7) are selected by a “tensed” illa, marked [+/−past]. We have already seen that it is the non-finite complements that contribute to the tense interpretation of these sentences. Are the non-finite complements also therefore “tensed,” in the sense of Landau (2004)?

Landau (2004:831, 838) proposes that complements with selected tense divide into two types: untensed or “anaphoric tense” complements, and “dependent tense” complements. Untensed ([−tense]) complements do not project an aspectually independent sub-event with respect to the main clause. Their tense is identical to the matrix tense. (Thus, Now, John knows how to swim is licit, but not ∗Now, John knows how to swim tomorrow.) Dependent tense ([+tense]) complements project an aspectually independent subevent, and “the tense of the embedded clause is constrained by (though, crucially, not necessarily identical to) the matrix tense” (Landau 2004:822): e.g., John (now) wants/hopes to leave (tomorrow).

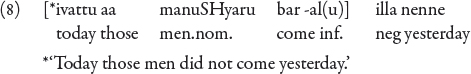

Neither of these notions (“anaphoric tense,” “dependent tense”) will serve our purpose. The question whether there is “dependent tense” in the complements to illa in (2)/(7) yields contradictory answers. The fact that the bare infinitive complement to illa has a tense interpretation argues that it must be [+tense]. (Recall that it is the bare infinitive’s tense interpretation as “past” that must determine its selection by the putative [+past] matrix tense feature covertly present on illa.) If so, a temporal adverb should be licensed in the embedded infinitive clause, which is independent of another temporal adverb in the matrix clause containing illa. But the complements to illa fail this test, showing that there are no two aspectually independent subevents in the negative clauses (2a–b) or (7a–b). Inserting separate temporal adverbs into (7b) (for example) renders it uninterpretable:

Then let us examine whether the complements to illa in (2)/(7) are anaphoric tense complements. Again, we arrive at a contradiction. We have seen that there is a single tense domain in (8). Since we have postulated a covert [+past] or [−past] feature on illa, we expect that its complement is untensed, i.e. that it is specified for anaphoric tense. But this cannot be, because the tense interpretation of (2)/(7) is determined solely by the nature of the non-finite complement: it is determined by whether the complement is a gerund ([−past]) or a bare infinitive ([+past]). These complements cannot therefore be untensed.

The relevant fact to be captured about (2) or (7) is not that a covert matrix tense selects an appropriate non-finite complement, but that a non-finite but [+tense] complement determines, as a single tense domain, the interpretation of a finite negative clause. The content of any putative covert tense feature on illa is determined solely by the “tense” of its non-finite complement. In this scenario, a covert tense feature on illa serves simply to anchor the sentence in time, i.e. to license the non-finite clause as a matrix clause. It does not make any contribution to the tense interpretation of the negative clause.7

Returning now to the Stowellian assumption that Tense anchors the sentence in time by specifying when an event occurs relative to an utterance, we see that Tense must be understood as a complex of features with two functions: finiteness, i.e. anchoring, and temporality; and that these features need not always occur together on one element. The core facts of the negative clause in Kannada show that the non-finite verb determines its tense interpretation, and the negative element illa anchors the sentence. Then Tense is not the only anchor available to languages, and finiteness must be understood as anchoring, not as Tense. We have already argued that the absence of a T(ense) node in a language need not entail the absence of a finite/non-finite distinction in it. Languages may distinguish anchored (=finite) from non-anchored (=non-finite) clauses in the absence of Tense. We have also referred briefly to the fact that modals appear to anchor a sentence; modals are not tensed, even though they are taken to be merged into a T node in a language like English. There already appears to be an implicit shift from the notion of tense to the notion of Mood as the anchor in the standard treatment of modal clauses.

Sentences with modals in Kannada have the modal taking a non-finite verbal complement, as in English. (The infinitive morphology in (9) surfaces in the presence of the emphatic morpheme; the verb form is otherwise indistinguishable from a stem form. Note the absence of subject-verb agreement.)

Example (9b) illustrates an interesting point. Kannada has “negative modals”, with the negation incorporated into the modal stem. Modals, in fact, cannot be negated by illa. Now this complementarity of modals and illa in Kannada (which contrasts with the co-occurrence of modals and not in a language like English) can be understood to follow from their both being anchors, or finiteness-denoting elements, in this language. We do not expect an anchoring element to have more than a single occurrence in a single finite clause. (Indeed, Ritter and Wiltschko 2009 formalize this intuition, pointing out that tense morphology does not appear on the auxiliary as well as on the main verb in English, and stating “uniqueness” as their first “formal diagnostic for INFL.”)

We have now established that neg illa and modals can anchor the Kannada clauses in which they occur, namely finite negative clauses, and modal clauses. What about the anchoring of affirmative clauses? As we saw in (1), these have a verb that carries a morpheme standardly analyzed as a “Tense” morpheme. Does the Kannada child then have to acquire two anchoring systems, one through Tense for affirmative clauses, and a different one for negative and modal clauses? How (moreover) are we to understand the “finiteness” or anchoring function of negation?

The answer to these puzzles emerges when we consider that the so-called tense morphemes in affirmative clauses are homophonous with aspect morphemes. Affirmative clauses may thus be analyzed as carrying not Tense, but aspect. As for their tense interpretation, we have proposed that in negative clauses tense interpretation is achieved through aspectual specification that references a finite element. We may assume a similar mechanism for affirmative clauses.

Let us say (therefore) that all Kannada sentences are anchored by Mood. The idea that affirmative sentences instantiate indicative mood is a traditional and familiar one. Negative sentences, we shall now say, are the negation of indicative mood. (Traditional grammars recognize a “negative mood,” but we may say that neg illa incorporates indicative mood.) The Mood Phrase, then, can host one of three elements: neg illa, a modal, or agreement, which we shall treat as the reflex of indicative mood.

The complement to the Mood head is a non-finite clause. This is obvious when the Mood head is illa or a modal. It is less obvious in the case of the verbal complement to agreement in affirmative clauses, but we have argued that this complement is also plausibly a non-finite aspectual complement. This analysis allows us to anchor the Kannada clause uniformly through Mood to the world, and to give a unified structure to the superficially very different affirmative and negative clauses in Kannada.

In (10), I indicate the possible heads of MoodP as subscripts. These heads select the relevant heads of the AspectP: agreement selects the so-called tense-aspect morphemes, modals the infinitive morpheme, and illa the infinitive or the gerund.

This picture enables us to understand why modals and agreement are in complementary distribution; why neg illa is in complementary distribution with both modal and agreement; and how affirmative and negative clauses can superficially look as different as they do.8

The pattern of selection in (10) between the mood heads and the verbal heads that express Aspect suggests that there is very probably a polarity phrase PolP intervening between MoodP and AspP in (10); and that agreement and illa are not merged into MoodP, but merged as heads of a polarity phrase with positive and negative values respectively. This explains why agreement and illa select Aspect complements with different heads: i.e. why agreement occurs with the “tense-aspect” instantiation of Aspect, and illa with its infinitival or gerundive instantiation. The selection would follow if the relevant verbal morphology carried polarity specifications that are compatible with the selecting head.

Let us say that the “tense-aspect” verb forms (the past and nonpast forms) are designated “positive polarity items” (PPIs) which cannot scope under neg. The plausibility of this idea lies in these verb forms’ membership in a paradigm of triples: namely as the perfect, the imperfect, and the negative participles. (A participial negative is instantiated in (5b) above. There are also negative gerunds and negative relative participles in Kannada.) The parallel fact about PPIs like someone is that they typically occur in a paradigm (Krifka 1995:225).9

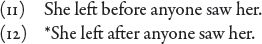

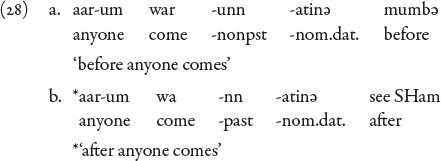

The idea that the tense-aspect verb forms are PPIs receives support also from a comparison of verb complements to munche ‘before’ and meele ‘after’. Let us first note that before and after differ in their licensing of polarity. The complement of before but not after serves as an affective domain:

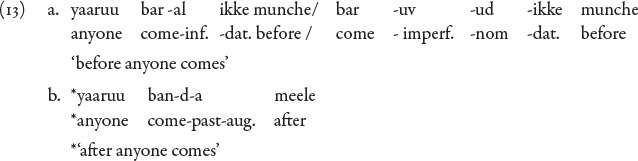

The corresponding postpositions in Kannada have similar properties: munche ‘before’, but not meele ‘after’, allows yaaruu ‘anyone’ in its complement.

Note now an interesting asymmetry in the verb complements (13a) and (13b): munche ‘before’ takes a non-finite (infinitive or gerundive) complement,10 meele ‘after’ takes a tense-aspect complement; i.e., the selection of verb complements by munche and meele mirrors the selection of verb complements by illa and agreement.

I thus revise (10) to (14).

In this section I generalize the clause structure arrived at for Kannada to the other three “major” Dravidian languages, Tamil, Telugu and Malayalam. Negative clauses in Tamil and Telugu are non-finite verb complements to a negative element, as in Kannada. I argue that these languages also therefore achieve clausal anchoring in terms of Mood, and not Tense. Nevertheless, Tamil and Telugu vary among themselves, and both differ from Kannada, in the tense interpretations they allow for negative clauses. These differences will be shown to be accommodated by the proposed structure.

Malayalam at first glance appears to depart from the Dravidian pattern, in that its negative clauses do not appear to radically differ from its affirmative clauses; the same tense-aspect morpheme appears on the verb in affirmative and in negative clauses. I shall argue that Malayalam nevertheless conforms to the Dravidian clause structure.

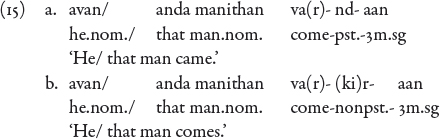

Affirmative clauses in Tamil have a verb that carries a tense-aspect morpheme and an agreement marker.

The negation of both (15a) and (15b) is (16). The Tamil negative clause in (16) is a matrix infinitive. The point to note is that it is completely free with respect to tense interpretation. (Note the absence of verb agreement in (16); subjects can be of any person, number and gender.)

What licenses the infinitive in (16)? Again, it must be the neg ille.11

Note that the absence of tense interpretation in (16) rules out the possibility of a covert tense feature [+/−past] on ille (recall that this was a putative technical solution to the finiteness of illa in Kannada that we considered above). Tamil thus speaks directly to the conclusion that ille serves simply to anchor the sentence (in addition to signalling negation), and so to license the non-finite clause.12 The status of neg ille in Tamil is parallel to illa in Kannada. It occurs only in finite clauses. It is excluded from infinitive complements and other non-finite clauses such as gerunds and participial relatives, where the neg -a must occur. It is distinct from a homophonous defective predicate of non-existence (cf. footnote 7, above).

All this suggests that anchoring in Tamil is via a MoodP, as in Kannada; that agreement in (15) is a reflex of indicative mood, while negation in (16) incorporates indicative mood. The tense-aspect morphemes in (15) must be analyzed as aspect morphemes; if they are analyzed as Tense, anchoring in affirmative clauses would differ from anchoring in negative clauses, since illa does not incorporate Tense.

How do we explain the absence of tense interpretation in the negative clause in Tamil? We have so far assumed (from the analysis of Kannada) that bare infinitives are specified for perfect Aspect, and yield a past tense interpretation. The Tamil facts suggest that the infinitive needs to raise to Aspect to get its aspectual specification; it is generated lower than Aspect on the clausal spine. In Tamil, the infinitive fails to raise to Aspect.

This could be explained as follows: the Aspect node in Tamil is specified for positive polarity; it can host only PPIs. The infinitive is obviously not a PPI (as its selection by neg ille shows). Hence Aspect cannot host the infinitive in Tamil. Aspect is specifiable only for the tense-aspect marked verbs, which are PPIs. The complement to neg ille in Tamil is not an Aspect Phrase, but an InfinitiveP.13 Note that Tamil must project the PolarityP proposed in (14), because agreement occurs only in affirmative clauses, and selects a tense-aspect marked verb. Note also that positive and negative polarity values must be specifiable independently of each other on the host Aspect node, on this analysis.

In the Tamil negative clause, then, we see finiteness without semantic tense. The Tamil negative clause is reminiscent of Halkomelem, which is said not to have obligatory tense inflection. A Halkomelem sentence without overt tense morphology can receive either a past or a present interpretation (Ritter and Wiltschko 2005:345, their Example (5)):

But affirmative sentences in Tamil are not like Halkomelem in this respect. The clause structure of Dravidian, then, seems to allow within a single language phenomena that look like possible parametric variations between languages. The analysis proposed here attributes this language internal “parametric variation” in Tamil to its PolarityP and the polarity of its AspectP.

Turning to Telugu, once again, affirmative sentences have verbs marked for what is usually taken to be a tense morpheme, and agreement suffixes.

Example (18b) with [+past] tense is negated by a matrix infinitive. The infinitive is followed by a neg element lee-du.

The past tense negative (19) in Telugu is structurally identical to its Kannada counterpart: there is an infinitive complement to a neg element. It must be the infinitive that gives the sentence its tense interpretation, and the neg that licences the infinitive and anchors the clause. Further, the tense-aspect verb form in (18b) cannot occur as the complement to leedu; it appears to be a PPI.

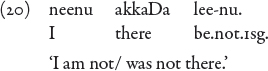

Neg leedu is distinct from its lexical counterpart, a verb lee of non-existence. Note that in (19), there is no subject-verb agreement: the putative agreement morpheme on lee is a fixed default form. In its lack of agreement, neg leedu differs from the verb of negative existence whose 1sg. (agreeing) form is lee-nu (cf. the 1sg. agreement morpheme -nu in (18)). This verb of negative existence, illustrated in (20), appears to have no tense interpretation.

Thus it is unlikely that the past tense interpretation of (19) arises from the neg element leedu. Neg leedu differs from its lexical counterpart lee in not exhibiting agreement, and the latter in any case has no tense interpretation.

Turning now to the negation of the non-past affirmative (18a), the [−past] negative clause in Telugu is related to an erstwhile “negative conjugation” in Dravidian that has not been discussed here.15 The negative marker in that “negative conjugation” was -a, a morpheme that is (as noted in our discussion) restricted to non-finite contexts in current Kannada and Tamil. Neg -a must occur lower in the clause than the finite neg; it occurs below infinitive or gerundive morphology, and infinitives and gerunds occur below finite neg, as its complements. Since we have said that infinitives are lower than Aspect, neg -a is also below Aspect.

In Telugu, too, -a occurs in non-finite contexts. The difference is that Telugu -a also occurs in non-past negation in the matrix context. In the “negative conjugation,” -a occurred in the tense-aspect verb paradigm. Neg -a could take the place of a tense-aspect morpheme, and be followed by an agreement morpheme. The negative clause was free in its tense interpretation. The Telugu [−past] negative clause (21) currently has a morpheme sequence identical to the erstwhile negative conjugation, but it has a non-past tense interpretation. This argues for a null AspectP above neg -a in (21).

I assume that agreement occupies the MoodP in (21), as in affirmative clauses, to anchor the sentence. Neg -a raises to imperfect Aspect.

Clausal negation in Telugu thus takes three forms. Neg leedu anchors the sentence, and selects an infinitive that raises to perfect Aspect, yielding a [+past] interpretation. A null imperfect aspect selects a neg -a, whose cognates in Kannada and Tamil are restricted to non-finite negation. This negative plus Aspect complex cooccurs with an agreement morpheme. Thus agreement anchors the non-past negative clause in Telugu, as it does the affirmative. Finally, a verb of negative existence lee-, which is completely free with respect to tense interpretation, occurs in a clause that is anchored by agreement, but does not project an AspectP. Telugu thus shows within itself stages in the unravelling of the erstwhile “negative conjugation” of Dravidian, and the development of neg as an anchor.

Among the four “major” Dravidian languages, in Malayalam alone are negative clauses not obviously non-finite. “Negation in Malayalam appears to be a straightforward affair of adding a negative marker to an affirmative sentence” (Amritavalli and Jayaseelan 2005:195). In (22)–(23), what looks like a tense morpheme (homophonous with an aspect morpheme) occurs on the verb. The negative sentences differ from the corresponding affirmatives only in the presence of neg illa.

Is Malayalam then different from the other Dravidian languages in its clause structure—does it anchor its clause temporally, through Tense?

One problem for a straightforward account of the negative sentences (22b, 23b) is that Malayalam, like Kannada and Tamil, clearly distinguishes a finite neg illa from a non-finite neg -aa. Malayalam illa cannot occur in gerunds or infinitive complements. The negative permitted in non-finite clauses in Malayalam—familiar from our discussion of its sister languages—is -aa.

In these sister languages, we have argued for a clause structure such that neg illa is finite (the anchor), and the tense-aspect morphology is always non-finite. The question is: what is the finite element in the Malayalam negative clauses (22b) and (23b): the tense/aspect morphology, or illa? If illa is finite, and there is also “Tense” on the verb, we (unacceptably) have finiteness marked on two elements in the negative sentences. (Recall the uniqueness diagnostic for Infl proposed by Ritter and Wiltschko 2009.)

Let us for argument’s sake adopt the view that Malayalam wears its clause structure on its sleeve, and that the verb in the negative clause is indeed tensed; i.e., that Tense is the anchor in Malayalam, and not Mood. Now the restriction of neg illa to finite clauses will have to be stipulated in some way; let us assume that this can be done.

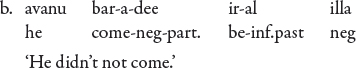

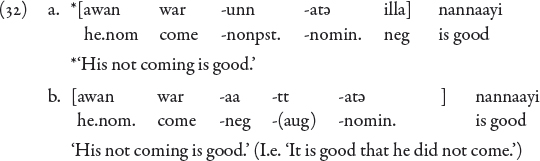

An immediate complication for such a stipulation is that it will need to include an additional prohibition: only one illa may occur in a finite clause. To see this, let us consider clauses with “double negation,” where both negatives in the clause count for interpretation (as distinct from “negative concord,” wherein only one negative is interpreted; Dravidian does not have negative concord). Consider the Malayalam counterpart to the English sentence He didn’t not come (=‘he came’). Where English allows two nots to occur, in Malayalam, two illas cannot occur (24a, 25a). The second negative has to be the non-finite neg -aa (24b, 25b).

Now this is a puzzling paradigm. If negation in Malayalam is a straightforward matter of “adding in” illa into a tensed clause, why is it not possible to add in a second illa, as in English?

Notice that the licit double negative clauses (24b, 25b) appear to have a somewhat complex structure. Let us look at the structure of the “inner negation” below illa (to the left of it). The “tense” morpheme no longer occurs on the lexical verb; it occurs on a dummy verb ‘be’. The lexical verb is “demoted”; it surfaces in an obviously non-finite (participial) form, and a non-finite neg -aa occurs on it.

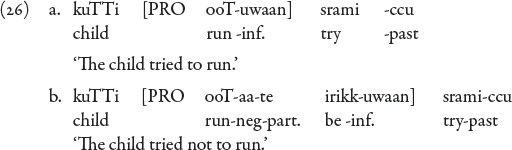

We must note two points. One, the structure of the “inner negation” in (24b) and (25b) is precisely the structure of non-finite clause negation in Malayalam illustrated in (26b) below. In the affirmative (26a), infinitive morphology appears on the verb in the complement to try. In the negative (26b), infinitive morphology appears on a dummy verb ‘be’. The lexical verb is marked with non-finite neg -aa, followed by a participial particle -te.

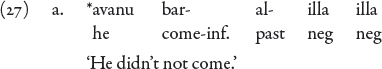

Two, double negation in Kannada is identical to double negation in Malayalam. In (27) below, we illustrate the Kannada counterpart to the Malayalam past tense double negatives (25).

(27a) shows a prohibition in Kannada, precisely as in Malayalam, on two illas in the negative clause. Note now the verb form in the licit (27b). The lexical verb is “demoted”; infinitive morphology appears on a dummy verb; and the lexical verb carries non-finite negation.

Now for Kannada, these facts are easily explained. Neg illa cannot appear more than once in a finite clause because it is the anchoring element; hence (27a) is ungrammatical. The complement to neg illa is non-finite (witness the infinitival morphology on the lexical verb in (27a)). So the complement to illa can only be negated with non-finite -a. (The reader may compare (27b) with (5b), which shows the negation of a purposive infinitive.)

But how do we explain the Malayalam facts, if we assume that Malayalam has “Tense”? On that analysis, the verbal complement to illa in (24b, 25b) is tensed (=finite). How and why (then) is it negated in the manner of a non-tensed clause, and why is illa prohibited in it?

Under the hypothesis that the clause structure of Malayalam conforms to the Dravidian pattern of anchoring by Mood, all these facts fall out. In negative clauses with illa, illa is the finite anchor. This explains why it cannot occur more than once—why a second illa is prohibited in double negative clauses. If illa is finite, its verbal complement is a non-tensed or aspectual complement. So it is negated in precisely the manner of a non-finite clause, by -aa.16

This still leaves one fact to be explained. If Malayalam has the same anchoring properties as Kannada, Tamil, and Telugu, why are its negative clauses different? Why are finite negative clauses not obviously non-finite clauses (such as infinitives or gerunds) in Malayalam?

There is one obvious difference in Malayalam: alone among the Dravidian languages considered here, Malayalam has lost overt verb agreement. Let us pursue the intuition that the explanation for the apparently straightforward pattern of negation in Malayalam is to be sought in this fact. This can be formalized in more than one way. In A&J, the suggestion was that in an agreeing language like Kannada, “tense” (i.e., aspect) and agreement morphemes are generated “together,” or “paired” in some way in affirmative indicative clauses. (The morphological evidence supports this idea. The shapes of the Kannada agreement morphemes in affirmative sentences co-vary with “tense”. Compare the present 3m.sg. sequence utt-aane with the past 3m.sg. sequence d-a(nu) in (1).) In this scenario, agreement has to climb to the finiteness position in the MoodP from its base position. Let us assume that in negative clauses, illa intervenes between agreement (generated along with Aspect) and MoodP. This would now explain why illa and agreement cannot co occur, and (thus) why the complement to illa in Kannada, or in Dravidian languages with overt agreement (more generally), could not be the same as in affirmative clauses.

Given the PolarityP that I have proposed in this paper, a different explanation becomes possible that builds on the same intuition. I have said that the selection of their complements by illa and agreement in Kannada is due to the polarity properties of the verbal morphology. A consequence of the loss of agreement in Malayalam could be a concomitant loss of polarity specification in its verb forms.17 In support of this argument, recall that we showed that in Kannada, the postpositions ‘before’ and ‘after’ select different types of verb complements. ‘Before’, which allows polarity sensitive items like ‘anyone’ in its complement, takes a non-finite (infinitive/gerundive) complement, as neg illa does. ‘After’ takes a tense-aspect marked verb from the affirmative paradigm.

We may now note that in Malayalam (unlike in Kannada), the postpositions mumbә ‘before’ and seeSHam ‘after’ both select verbal complements from the same tense-aspect paradigm. These postpositions nevertheless differ in their ability to license polarity-sensitive ‘anyone’ in their complement.

We thus see a consistent difference between Malayalam and Kannada with respect to the selection of verbal complements by polarity-specific heads. In Kannada, both neg illa and the postposition ‘before’ must choose gerundive or infinitive verbal complements, rather than the PPI tense-aspect verb complements that occur in affirmative clauses. In Malayalam, neither illa nor ‘before’ need choose a verbal complement other than the one that occurs in affirmative clauses.

This suggests that the difference between Malayalam and Kannada is that (with reference to (14)) Malayalam does not project a Polarity P, but merely projects a NegP above AspectP.

We have so far been concerned mainly with the question of anchoring, set down at the outset as assumption (A). It will have been obvious to the reader that our argument serves also to question the assumption that Tense is responsible for nominative case marking on subjects; i.e. assumption (B), repeated below:

B. Nominative case marking on subjects is a reflex of finiteness, i.e. of a tensed clause.

Dravidian has no Tense, but it has nominative subjects. Even if we hold that at least affirmative clauses in Dravidian have Tense, there remains the problem of nominative subjects in negative clauses, which are obviously not tensed.

These negative clauses are, however, finite. Can we then maintain that nominative case is a reflex of finiteness or anchoring, if not of Tense as such? Then the first clause of (B) would still hold, and nominative case marking in finite clauses in Dravidian could be accounted for.

Unfortunately for this hypothesis, the gerund in Dravidian has nominative subjects. Not only do current theories assume gerunds to be non-finite; gerunds are also arguably non-finite in Dravidian, by the test of the negative they permit. The finite or anchoring neg illa and its cognates are disallowed in the gerund; the neg element allowed is the non-finite neg -a (and its cognates), as illustrated below.

I shall illustrate this in Malayalam, taking it as representative of this phenomenon in Dravidian. The significance of this property of Malayalam can be appreciated when we recall that the apparently straightforward pattern of negation in Malayalam encourages an analysis of this language as carrying Tense. We have argued against this analysis in the previous section; we shall now see that gerunds too pose a problem for the postulation of Tense in Malayalam as a licensor of nominative case.

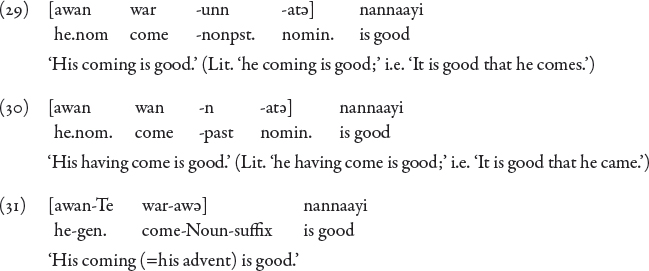

To repeat, in Malayalam (as in Kannada, Tamil and Telugu, not illustrated here), the subjects of gerunds are marked nominative, not genitive (29)–(30). In contrast, the subjects of underived nouns are marked genitive (31).

Notice that the noun in (31) does not carry any tense/aspect marker, whereas the gerunds in (29)–(30) do. In Malayalam, as we have noted, there is tense-aspect homophony. Is the temporal marker in (29)–(30) then Tense, that licenses nominative case on the subject?18

The diagnostic of negation by illa shows the gerund to be non-finite (32a). (32b) shows that it is the non-finite negation -aa that must occur in the gerund.

Could we use the idea of “dependent tense” to explain the nominative case on the gerund in Dravidian? The positions regarding Tense taken here and by Landau (2004) are not incompatible, in as much as they both countenance the presence of semantic tense in morphosyntactically untensed clauses. Landau (we may recall) shows that nominative subjects can occur in infinitivals if they project an independent tense domain. Menon (2011) adopts his analysis for one class of infinitivals in Malayalam, termed uwaan2 infinitivals in the literature, which attest an alternation of PRO with nominative subjects.

Can we say that the Dravidian gerund has dependent tense? Dependent tense is typically selected by a matrix predicate; but it is not clear how the tense in the gerund in (29)–(30) could be selected, as the matrix predicate equally allows perfect and imperfect gerunds to occur as subjects.

An alternative approach that could be explored, first suggested in Jayaseelan (1984) and pursued in Amritavalli and Jayaseelan (2007) and Amritavalli (2010), is that nominative case assignment is a two-step process; and that the number and gender features of participles license a ‘weak’ nominative case (which may be the “nominative absolute” found in some varieties of English). I must note that the nominalizing morphology -atә in (29)–(30) and (32b) incorporates a 3n.sg. agreement or pronominal morpheme in Dravidian, tә. In Malayalam, which has no agreement, the 3n.sg. distal and proximal pronouns are a-tә and i-tә.

I shall leave this question open, observing only that the core instances of nominative case marking in Dravidian appear to be a reflex of clausal anchoring or finiteness; and that ancillary principles may account for nominative subjects of infinitives and gerunds.

The Dravidian languages anchor the clause to the world of the utterance by virtue of Mood. MoodP has multiple exponents: we have identified agreement, modals and a finite occurrence of neg as anchors. The Dravidian languages thus lack Tense, where Tense is understood as a morphosyntactic element with a temporal interpretation that in addition functions to anchor the sentence to utterance or speech time.

A clear distinction between finite and non-finite clauses nevertheless exists in these languages (contra Lin 2010). Finiteness is therefore a reflex of clausal anchoring, and not of Tense. The functions of Tense that arise out of its anchoring property, such as the licensing of nominative subjects, are attributable to finiteness, and obtain in the absence of Tense. Thus negative clauses in Dravidian that (under current theoretical assumptions) are deemed to be “matrix non-finite clauses” have nominative subjects, and contrast in this respect with non-finite complements to verbs like try. In Dravidian as in Tense languages, problematic cases occur of nominative case licensing: the subjects of gerunds (demonstrably non-finite), and of one class of Malayalam infinitives, are nominative.

Tense interpretation in Dravidian is independent of tense-aspect morphology. Finite negative clauses in Kannada, which do not have tense morphology, have clear tense interpretations. Tense interpretation is also (of course) independent of anchoring: the finite negative clause in Tamil has neither tense morphology nor tense interpretation. This difference between Tamil and Kannada was explained in terms of the positive polarity of AspectP in Tamil, but not in Kannada. The polarity-sensitive selectional relations that obtain between anchors and morphological verb forms in the overt agreement languages motivate a PolarityP in them. Malayalam, which has no agreement, lacks a PolarityP. Its negative clauses therefore do not superficially differ from its affirmative clauses in their verb morphology.

My account of anchoring confirms one of the diagnostics for anchors suggested by Ritter and Wiltschko (2009), that of uniqueness; and assumes a second: obligatoriness (in finite clauses). A third diagnostic these authors suggest is the possible “lack of phonetic content (silence).” This may be pertinent to Malayalam, wherein affirmative clauses must be licensed by a null element, Malayalam having no verbal agreement morphology.

However, I do not require that an anchor exhibit “the presence of an obligatory contrast of some sort” (cf. footnote 8 above) in INFL; observing that although Tense, Location and Person features apparently introduce a feature contrast, modals (which render a clause finite) do not. The relevance of the other diagnostics suggested by Ritter and Wiltschko (2009) (i.e., expletiveness, and movement to COMP) remains to be seen. Lin (2010) suggests a slew of characteristics that languages without Tense may exhibit, including the lack of a copula in constructions with a nominal predicate. This property holds in Kannada, Tamil and Telugu, but not in Malayalam. The predictions and claims made in the literature with regard to Tenseless languages thus remain to be validated.

Finally, the parallels that Ritter and Wiltschko (2005) point out between event anchoring and the anchoring of entities are worthy of investigation. These authors describe Blackfoot, in which discourse participants serve to anchor the event to the utterance, as also using this strategy to anchor entities to the utterance. In its demonstrative system, “different demonstrative stems express degrees of proximity to the speaker, the addressee or both.” Now as is well known, the Dravidian pronominal systems incorporate demonstratives that encode proximity or distalness with respect to the speaker. (The pronouns are analyzable as distal/proximal markers and a Person-Number-Gender suffix.) More interestingly, Blackfoot has a “suffix to mark words referring to entities which are not visible.” Some of the so-called “minor” Dravidian languages (with no literary history) are claimed to have just such agreement suffixes (Ramakrishna Reddy, personal communication).

Thus the claim that agreement in Dravidian is an anchor may be related to the claim in Ritter and Wiltschko (2005) that utterances can be anchored by discourse participants (that is, the fact that in the affirmative indicative mood the Mood head is occupied by agreement may indicate that Dravidian needs to anchor such sentences by way of the subject). Ritter and Wiltschko (2009) indicate that Person anchoring is less well understood than Location anchoring. Nevertheless, the investigation of parallelisms in the anchoring of events and entities is enticing, in view of the parallelisms between T and D already noted in the literature.

1. In (3a), the watching goes on until the prisoners have died, and in (3b), the marching goes on until the marchers complete entering the mess hall; i.e., the events described in the embedded clauses are completed.

2. Lin (2006) modifies the rule for the interpretation of perfective aspect, to indicate past time.

3. Subsequently, Ritter and Wiltschko (2009) have analyzed these clauses as non-finite nominalized clauses that disallow location anchoring, and have possessive morphology as subject agreement. They now characterize the contexts where Halkomelem does not allow location marking as precisely those where English does not allow tense marking.

4. Observing that “the strongest piece of evidence” for this distinction in Chinese is the distribution of PRO and lexical subjects, Lin refers to alternative analyses that do not appeal to finiteness. Lexical subjects occur in control contexts where an adverbial intervenes between the matrix verb and embedded subject. This suggests that the absence of lexical subjects in these same contexts may be due to the Obviation Principle. Control into the possessor position of body-related nouns (‘tears’, ‘breast milk’) suggests the possibility of a semantic/pragmatic account of control into verb complements as well.

5. Non-finite negation appears on the stem of the verb, and is followed by an augment. Infinitive morphology does not appear on the negated verb, but on a dummy verb ‘be’.

6. The finite complementizer has the cognate forms ani, annɨ and ennә in Telugu, Tamil and Malayalam, sister Dravidian languages with a literary tradition (hence the nomenclature “major” Dravidian languages). The Dravidian finite complementizer is often referred to as the “quotative.”

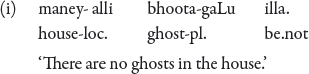

7. The proposal to specify neg illa with a covert tense feature in effect treats it as a “higher predicate” that selects a verbal complement. Our argument against it is consistent with evidence that neg illa is distinct from a negative existential predicate illa, illustrated in (i):

Negative existential illa has non-finite relative and conditional forms:

Neg illa has no non-finite forms.

These facts were first noted by Hany Babu (1996) for Malayalam.

8. Ritter and Wiltschko’s (2009) Parametric Substantiation Hypothesis allows functional categories not to be uniquely associated with the same substantive content across languages (INFL in English is INFLTENSE, in Halkomelem INFLLOCATION, and in Blackfoot INFLPERSON). It does not envisage multiple exponence of a functional category within a language. Note that these authors do not address the question of the finiteness of modals in English, i.e., the occurrence of INFLMODAL. This oversight also explains their belief that “the presence of an obligatory contrast of some sort” in INFL (i.e., a binary contrast of tense, location or person) is necessary for anchoring.

9. Krifka contends that NPs based on some are not polarity items. He attributes the scope differences of not … anyone, not … someone to “a paradigmatic effect induced by Grice’s principle of ambiguity avoidance” (the unambiguous form with anyone would be preferred for the wide-scope reading of not). But he concedes that “it may … be that this paradigmatic effect is so strong that it is virtually grammaticalized.”

10. This context “neutralizes” the gerund and the infinitive into a single non-finite category.

11. In speech, ille is often realized as le. Emphatic markers -ee or -ũũ on the verb may render ille more perspicuous: vara(v)-ee (i)lle, vara-(v)-ũũ ille.

12. Data such as (15)–(16) explain the Dravidianist Schiffman’s (1974) call for “an evaluation procedure to help ascertain when two sentences are equivalent except for one being positive, the other negative,” and his speculation that the ability to relate affirmative and negative sentences in this way is “perhaps an artifact of Western education and perhaps Aristotelian logic” (1974:9, quoted in Amritavalli 1977:9).

13. Cf. Ramadoss and Amritavalli (2007) for a discussion of Tamil clause structure.

14. Hariprasad describes the tense system of Telugu as [+/−future] (in his system, (19) is negation of the “non-future”). I retain without argument a conservative specification of tense as [+/−past].

15. Cf. Amritavalli (2004).

16. In the next section we see that Malayalam also has nominative subjects in gerunds, unexpected in a language where Tense licenses nominative case.

The main thrust of the review of A&J by Hany Babu and Madhavan (2002) is that tense-aspect homophony cannot suffice to motivate the reanalysis of tense as aspect in Malayalam. They however take no cognizance of the problems pointed out here and in A&J for the “Tensed” analysis of Malayalam.

17. We may speculate that in the history of Dravidian, agreement developed polarity when a neg illa developed, distinct from the neg -a of the negative conjugation. (The latter, I said, co-occurred with agreement in that conjugation; it was in complementary distribution with tense-aspect.) Then Malayalam exhibits a later stage in this development, wherein agreement is lost, and concomitantly, so is the polarity of the verbal tense-aspect morphology.

18. A&J remark (p. 197) that Jayaseelan had (in earlier work on Malayalam) indeed, for this reason, “misdiagnosed the category Tense in verb forms that are at best ambiguous between tensed and aspectual forms.”

References

Akmajian, Adrian. 1977. The complement structure of perception verbs in an autonomous syntax framework. In Formal syntax, eds. Peter Culicover, Thomas Wasow, and Adrian Akmajian, 427–460. New York: Academic Press.

Amritavalli, R. 1977. Negation in Kannada. Master’s thesis, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby.

Amritavalli, R. 2000. Kannada clause structure. In Yearbook of South Asian languages, ed. Rajendra Singh, 11–30. New Delhi: Sage India.

Amritavalli, R. 2004. Some developments in the functional architecture of the Kannada clause. In Clause structure in South Asian languages, eds. Veneeta Dayal and Anoop Mahajan, Studies in natural language and linguistic theory, 13–38. Boston: Kluwer.

Amritavalli, R. 2010. Person checking in nominative and ergative languages. In Proceedings of GLOW in Asia VIII, 80–87. Beijing: Beijing Language and Culture University Press.

Amritavalli, R., and K. A. Jayaseelan. 2005. Finiteness and negation in Dravidian. In The Oxford handbook of comparative syntax, eds. Guglielmo Cinque and Richard S. Kayne, 178–220. New York: Oxford University Press.

Amritavalli, R., and K. A. Jayaseelan. 2007. Clause structure and early acquisition of split ergativity and negation. In GLOW in Asia VI: Parametric syntax and language acquisition. Hong Kong: The Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Comrie, Bernard. 1976. Aspect. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Enç, Mürvet. 1987. Anchoring conditions for tense. Linguistic Inquiry 18(4): 633–657.

Hany Babu, M. T. 1996. The structure of Malayalam sentential negation. International Journal of Dravidian Linguistics 25(5): 1–15.

Hany Babu, M. T., and P. Madhavan 2002. The two lives of -unnu: A response to Amritavalli and Jayaseelan. CIEFL Occasional Papers in Linguistics 10.

Hariprasad, M. 1989. Negation in Telugu and English. M. litt thesis. CIEFL: Hyderabad.

Jayaseelan, K. A. 1984. Control in some sentential adjuncts of Malayalam. Berkeley Linguistics Society 10: 623–633.

Kayne, Richard S. 1991. Italian negative imperatives and clitic climbing. Ms., New York: CUNY.

Krifka, Manfred. 1995. The semantics and pragmatics of polarity items. Linguistic Analysis 25(3–4): 209–257.

Landau, Idan. 2004. The scale of finiteness and the calculus of control. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 22: 811–877.

Lin, Jo-wang. 2006. Time in a language without tense: The case of Chinese. Journal of Semantics 23: 1–53.

Lin, Jo-wang. 2010. A tenseless analysis of Mandarin Chinese revisited: A response to Sybesma 2007. Linguistic Inquiry 41(2): 305–329.

Menon, Mythili. 2011. Revisiting finiteness: The need for tense in Malayalam. Paper presented at FISAL: Tromsø.

Ramadoss, Deepti, and R. Amritavalli 2007. The Acquisition of functional categories in Tamil with special reference to negation. Nanzan Linguistics Special Issue 1: Papers from the Consortium Workshops on Linguistic Theory, 67–84. Graduate Program in Linguistic Science: Nanzan University.

Ritter, Elizabeth, and Martina Wiltschko. 2005. Anchoring events to utterances without tense. In Proceedings of the 24th West coast conference on formal linguistics, eds. John Alderete et al., 343–351. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project. www.lingref.com, document #1240. Accessed 10 July 2013.

Ritter, Elizabeth, and Martina Wiltschko. 2009. Varieties of infl: Tense, location, and person. In Alternatives to cartography, ed. Jeroen van Craenenbroeck. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. http://ling.auf.net/lingbuzz/000780/current.pdf. 31 August 2013.

Schiffman, H. F. 1974. Complex negation in Tamil: Semantic and syntactic aspects. Jaffna, Sri Lanka. Paper presented at the Fourth International Conference of Tamil Studies.

Stowell, T. 1982. The tense of infinitives. Linguistic Inquiry 13: 561–570.

Stowell, T. 1995. The phrase structure of tense. In Phrase structure and the lexicon, eds. Johan Rooryck and Laurie Zaring, 277–291. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Zanuttini, Raffaella. 1991. Syntactic properties of sentential negation: A comparative study of Romance languages. Doctoral dissertation, University of Pennsylvania.