R. Amritavalli and K. A. Jayaseelan

Hale and Keyser (1993:76) say that “argument structure, or LRS [lexical relation structure] projections, are constrained in their variety by (i) the relative paucity of lexical categories, and (ii) the unambiguous nature of lexical syntactic projections.”* They assume the inventory N, V, A and P for lexical categories, corresponding to the semantic types of entities, events, states and relations (respectively).

Not all languages have all four of these categories, however, a fact that immediately complicates any one-to-one mapping between lexical category and semantic type. Whereas N and V appear to be universal, A and P are not. Hale and Keyser have themselves noted—citing the examples of Navajo and Walpiri—that the adjectival and prepositional functions may be performed in some languages by V or N (see Hale and Keyser 2002:13-14). (This is true also of Dravidian languages, as we shall see.)

In this paper we offer some speculations about the genesis of the two categories which are not primitive, namely A and P. We shall suggest that a language which has one also tends to have the other; and we shall try to explain why they arise together.

Whereas LRS representations ought to be the same for all languages, their surface realizations obviously are not. We show that some types of parametric variation between languages can be directly traced to the inventory of lexical categories they have. In particular, whether a language has a two-category lexical base or a fuller, four-category lexical base explains a well-observed typological divide between languages with respect to two construction types: the Dative Experiencer construction and the serial verb construction.

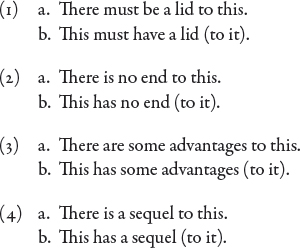

Consider (1-4) in English, which show an alternation of have and be:

The (a) sentence has a “dative NP” to this; which, in the (b) sentence, corresponds to the subject, which is a nominative NP. The other NP in these structures—in (1a, b), a lid—is apparently subject to an indefiniteness or non-referentiality constraint (as was pointed out in Amritavalli & Jayaseelan 2002), cf. * This must be the lid to that (or * This lid must be to that).

In English, the construction illustrated in the (a) sentences of (1)-(4) is extremely restricted, and truly vestigial. It is largely confined to “possessor datives” (but see § 8 below); and even in this class, it has the restriction that the possessor must be inanimate or abstract: cf. * There are ten fingers to me; There are five fingers to each hand. In some other languages—e.g. the Dravidian languages, Japanese and Korean—the dative construction is more widespread.

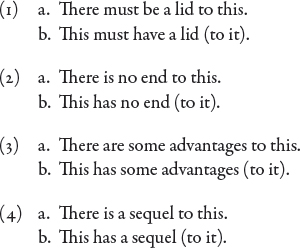

In Dravidian, (1a) corresponds to (5) (Kannada example), which is almost a word-for-word translation of it (modulo word order):

But Dravidian has nothing corresponding to (1b), which is a significant fact.

We have now two questions: (i) In the type of alternation illustrated by the English data (1)-(4), how are the (a) and (b) sentences related? (ii) Why does Dravidian not have a sentence type corresponding to the (b) sentences?

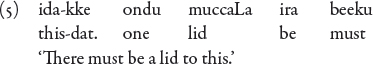

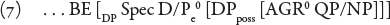

Our attempt to answer these questions takes off from an account of the BE/HAVE alternation offered in Kayne (1993). Kayne bases his analysis on some facts regarding the behavior of the possessive in Hungarian described by Szabolcsi (1983). In Hungarian, the possessive construction has a verb van which can be translated as ‘be’. It takes (according to Szabolcsi) a single DP complement, which contains the possessive DP. The possessive DP occurs to the right of (lower than) the D0 head of the complement of be. The full structure is:

If DPposs stays in situ, it has nominative Case. But if it moves to Spec of D0, it gets dative Case; it may now move out of the DP entirely, but the dative Case is retained. If D0 is definite, the two movements mentioned above are optional; but if D0 is indefinite, these movements are obligatory. Thus the possessive construction in Hungarian surfaces as (something like) To John is a sister.

Kayne claims that the English possessive construction has a substantially parallel underlying structure, with just a few parametric variations. The verb is an abstract copula, BE; which takes a single DP complement. A difference is that English has a non-overt “prepositional” D0 as the head of this DP, which Kayne represents as D/Pe0. The structure is:

In English, AGR0 cannot license nominative Case on DPposs, which therefore moves to the Spec of D/Pe0. But the latter also cannot license dative Case (English having lost dative Case); so DPposs must move further up, to get nominative Case in Spec, IP. The “prepositional” D0 adjoins to BE in English, and is spelt out as have. (The idea that have is be with a preposition incorporated into it is adopted from Freeze (1992).)

In the light of the above analysis we can make sense of the alternation illustrated by (1)-(4). In the (a) sentences, D/Pe0 has not adjoined to BE; so there is no have in the place of be. And the dative Case associated with D/Pe0 is realized as the preposition to. (The details of this Case-to-preposition change, we shall come back to presently.) The (b) sentences represent the “normal” possessive construction of English, with have as the verb and the possessor in the nominative Case.1

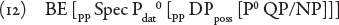

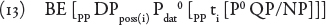

Let us propose a slightly different structure for the possessive construction. Assuming (with Hale and Keyser) that theta roles are defined as positions in structural configurations, what is the structure corresponding to the possessive theta role? Functional elements like AGR0 and D0 cannot be part of a configuration that determines a theta role; therefore in (7), DPposs cannot have as its base position the Spec of AGR0. The AGR projection, if it must be postulated, must be higher. We shall also assume, differently from (7), that D0 and P0 are heads of separate projections; and that a D0 may not be generated at all if the DP is indefinite. The P0—which in this case licenses dative Case in its Spec position, and which we can notate for the time being as Pdat2—may actually be generated outside DP.3 But Pdat (again) should not be part of the theta configuration in question, because it is only a functional element (a Case-assigner).

The notion of possession implies two entities that stand in a certain relation. We shall represent the relation as a P,4 which takes two entity-denoting expressions in its Spec and complement position. The copula BE may or may not be an essential part of the configuration; for concreteness, let us assume that it is. The theta configuration for the Possessor we assume is the following:5

We suggest that this is also the configuration for the Experiencer theta role, a claim in line with the observation that the theta roles available to Language are quite few in number, being limited by the number of distinctive configurations available (Hale & Keyser 1993). Therefore, (9) may be revised as (10):6

The configuration (9) (or (10)) occurs in a context of functional categories in the structures we are interested in. In order to linearize these functional categories, let us look at Hungarian again. As we said, DPposs in Hungarian must move before it gets the dative Case. The evidence for saying this is that the Hungarian D0, when definite, is optionally overt; and when it is overt, what we find is that DPposs is nominative when it occurs to the right of D0, and dative when it occurs to the left of D0. This argues that AGR0 (licensing nominative Case) is to the right, and Pdat to the left, of D0.

The full structure we are dealing with (then) may be something like (11):

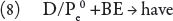

But here, the D0 (as we said) may not be generated if the possessed entity is indefinite; as it is in all the cases that we shall speak of.7 The AGR0 also may be only optionally generated. If D0 and AGR0 are absent, what we get is (12):

Consider the situation where DPposs has moved into the Spec of Pdat:

In English, Pdat adjoins to BE and we get have; and DPposs then moves to the Spec of a higher functional projection to get nominative Case.

We have now a reasonable answer to our first question: In the alternation illustrated by the English data (1)-(4), how are the (a) and (b) sentences related? We now come to our second question: Why does Dravidian not have a sentence type corresponding to the (b) sentences?

Let us first note that the element we call ‘Pdat’, which “licenses” a dative Case in its Spec position in Kayne’s analysis, is probably a Case element (K); and the phrase it heads is a KP. Regarding Kayne’s proposal that this element adjoins to BE to yield have, we suggest that this kind of “absorption” takes place only when Case is destabilized in the course of syntactic change.

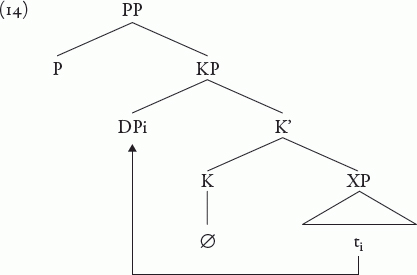

In fact, when Case is destabilized, two things tend to happen. One is the creation of a new syntactic category P(reposition). We can conceive of this development as follows: when the head of the Case Phrase (KP) becomes null (‘ø’), the language develops a higher projection headed by P, which is “paired with” the KP (see Kayne 2003: ex. (57)):8

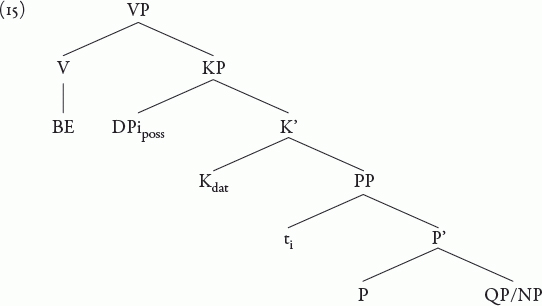

A second thing that can happen (when Case is destabilized) is the “absorption” of Case into existing lexical categories, of which we have been examining an instance. Consider (15), which is a diagrammatic representation of (13), but with the change that Pdat has been replaced by Kdat:

The Kayne claim is that in English, the dative Case assigning element—his D/P0, which for us is Kdat0—adjoins to BE and we get have. We suggest that something else can happen in (15): when NP consists of only an N, it may adjoin to Kdat (“picking up” the intervening head P on the way) and be realized as an adjective. That is, what we call Adjective is Noun incorporated into Case.

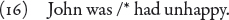

This hypothesis explains a fact noted in Kayne (1993: 112), namely that have cannot take an adjectival complement:

Note that if have is derived from be, it is prima facie surprising that have cannot take an adjective as its complement. But we now see why this is so: it is the same Pdat that either incorporates into be to yield have, or combines with a noun to give us the adjective.9

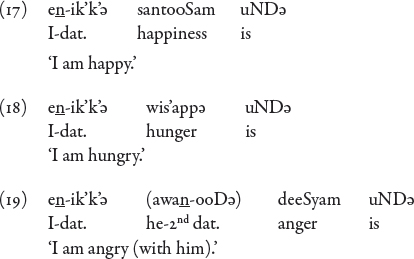

Consider the ‘dative subject’ construction (Malayalam examples):

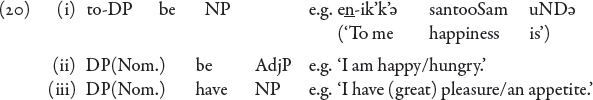

The contrast of this structure with the corresponding English structure has been discussed a great deal under the rubric of “quirky Case subjects.” What has caught the attention of linguists is the Case contrast on the Experiencer argument: dative Case vs. nominative Case. But there is another consistent contrast here: English has an adjective where Malayalam has a noun. This second contrast (to the best of our knowledge) has hardly been noticed. We now see that the two choices are related; i.e. there is a dependency between the adjective/noun choice and the dative/nominative choice. Moreover, these two choices are also dependent on the BE/HAVE choice in English. We can say that there are three possibilities for languages to express notions like ‘being happy/sad/hungry’:

All three patterns are derived from the same underlying thematic structure, by different choices of incorporation. If dative Case is realized on the Experiencer, the Case element (Kdat) must have remained independent; so there can be neither have, nor an adjective, cf. (i). If N has adjoined to Kdat to yield an adjective, there cannot be dative Case on the Experiencer argument nor the verb have, cf. (ii). And if Kdat has adjoined to BE and yielded have, there can be neither a dative Case on the Experiencer argument nor an adjective, cf. (iii).

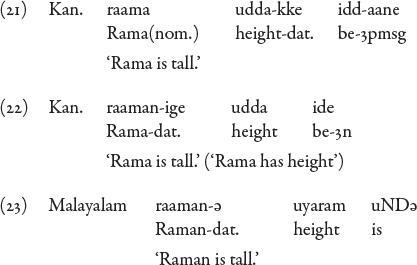

In some instances in Kannada, a contrast between the “dative subject” and the nominative subject patterns makes transparent our hypothesis that A is K to which N has adjoined.10 In Kannada the normal way to say ‘Rama is tall’ is (21); the dative pattern (22) is used only in contexts like ‘Rama has the height to do something’. In (21), udda-kke ‘height-dat.’, functionally an adjective, is transparently N+K. (But Malayalam has only the dative pattern (23).)

Let us briefly review the more traditional arguments against a category ‘Adjective’ in Dravidian.11 Morphologically, most putative adjectives or adverbs in Kannada are clearly derived from nouns, either by dative suffixation (cf. udda ~ udda-kke ‘height ~ to a height’, i.e, tall; kappu ~ kappige ‘blackness ~ dark, black’); or by -aagi suffixation to a noun (sukha ~ sukhav-aagi ‘happiness ~ happily’), where -aagi (lit. ‘having become’) is very probably currently a complementizer (‘as’); or by aada-suffixation to a noun (ettara-vaada ‘height having happened’.) Whether the derived forms are categorially compositional, or categorially different from the components, has been open to debate. There are only a few indisputable underived adjectives, such as oLLeya ‘good.’

A syntactic argument against distinguishing adjectives from nouns in Kannada is that they take the same range of specifiers. In English, intensifiers distinguish these categories (Emonds 1985:18): cf. how angry, how much anger. In Kannada, the intensifier yeSHTu occurs with both N (24i) and A (24ii).

The distribution of isHTu ‘this much’, aSHTu ‘that much’ is similar. Intensifiers like bahaLa ‘very much,’ tumba ‘very many’, svalpa ‘little,’ saakaSHTu ‘enough, quite a few’, cooccur with both N and A.

The point extends to the comparative construction in Kannada. A postposition -inta ‘than’ appears on a noun marked with dative Case:12

We said that in English, N incorporates into K to yield an adjective. The chain of incorporation can go farther up, to “take in” an abstract inchoative verb.

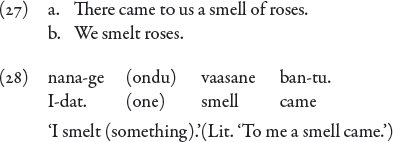

Consider (27a), which has a paraphrase relation with (27b). ((27a) is an “Experiencer dative;” it is even more vestigial in English than the “Possessive dative”.) Dravidian has only the dative construction here (Kannada example):

The English “Experiencer dative” seems to have a requirement that the “experience NP” be modified (“heavy”); cf. ?? There came to us a smell.

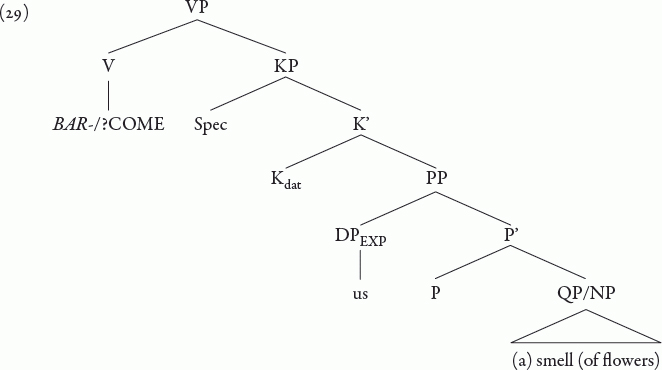

The Kannada and the English sentences must have the LRS (29) (cf. (15)).

In Kannada, the experiencer NP moves to Spec of Kdat in the familiar way.

In English, the noun ‘smell’ incorporates into P, and then into Kdat. This latter movement is made possible by the weakening of Kdat to null. The resulting complex element then incorporates into an abstract inchoative V to yield the denominal verb smell. (That is, the verb smell in English is derived in much the way that Hale & Keyser derive denominal verbs like shelve.) The incorporation operations here are nearly obligatory if the N head of the ‘experience NP’ is unmodified, cf. the marginality of ?? There came to us a smell. But if the relevant NP is “heavy”, this series of movements is optional, and a “dative” experiencer construction surfaces in English alongside the nominative construction.13

Incorporation from the complement position of P is completely absent in Dravidian, which has no verbs corresponding to the English shelve class. This is to be expected, since the head of KP has not been weakened.

Why is incorporation the preferred outcome in English? We suggested that when Case is weakened, it may get “absorbed” into other categories, or the language may develop Prepositions. Both these things happened in English. But in the history of English, during the transition from Old English to Early Middle English in the 12th century when the “loss of Case signals … encouraged speakers to use more prepositions” (Lumsden 1987:302), there appears to have been an indeterminacy or a variability in the preposition chosen to “pair” with a weakening Case-marker. Thus Lumsden (1987:352ff.) describes how the OE verbs with dative objects begin to appear with the preposition to; but this to is different from both the OE and the modern to, because as “the ME equivalent of the OE affixes of inflection,” it is interchangeable with of, on, and at.14

It may be that this indeterminacy of the “paired” preposition for Kdat is the reason why the verb come+KP in English has yielded to verbs derived from cognate objects.

This ends our discussion of the “dative construction”, and of why Dravidian has this construction and English does not have it (or has it only vestigially). The second parametric difference between Dravidian- and English-type languages had to do with serial verbs. Emonds (1985:40) notes an interesting correlation: “Languages which have ‘serial verb constructions’ often apparently lack PP structures.” Why should this be so?

Serial verbs are adjuncts (Jayaseelan 2003), so we shall need to understand some things about adjuncts; and also about the complements of BE. The two are related, because the phrases that can be the complements of BE are also the phrases that can be adjuncts; and the commonality has to do with Case.

In our structure (15), the complement of BE is a KP. In the particular instance, it is a KdatP. Suppose we say that BE always selects a KP. (It would be like v in this respect (see fn. 8), but with the difference that v is invariably paired with a KaccP, whereas BE can apparently select any KP.) Making such an assumption about BE has several advantages, as we shall see.

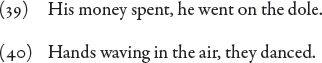

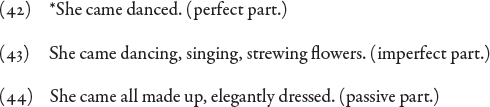

Consider the English perfect and passive participles, both -en forms. Superficially, the perfect participle is selected by have, the passive participle by be:

Kayne (1993) rightly suggests that the analysis of the main verb BE/HAVE should be extended to the auxiliaries; and notes (in this connection) a suggestive fact noticed by Benveniste (1966, sect. 15): in Classical Armenian, the subject of a transitive past participle appears as an oblique dative/genitive.

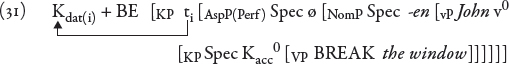

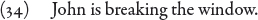

Let us assume that the English perfect participle phrase also has a dative Case at the point when BE selects it; and that the dative Case obligatorily adjoins to BE and is realized as have; cf. (31). (In (31), we have shown the head of the Aspect Phrase (AspP) as null; because we think that -en—possibly a nominalizer—does not carry the meaning of perfective aspect.)15

The account of the passive participle phrase has to be more complicated. There are two facts to account for here: (i) we do not get have in the place of be; and (ii) the transitive verb is unable to Case-mark the Object.

Fact (i) argues that Kdat0 is not generated; which can be readily understood if the dative Case here “goes with” the perfective aspect.16 Eliminating (then) both KP and AspP from (31), we get:

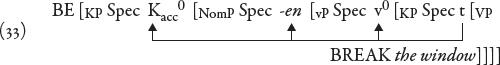

But BE (as we said) selects only a KP. Let us say that in order to satisfy BE’s requirement, Kacc0 moves up to head a KP; and that it does this by adjoining to, and excorporating from, each of the intervening heads:

A point unexplained in (33) is that the Spec of Kacc0, in its new position, is never filled; otherwise we should get an accusative DP immediately after BE. Possibly, Kacc0 obligatorily adjoins to BE when it is in the configuration (33), although this adjunction is without any overt morphological reflex. (When Kacc0 is not in the configuration (33), it can in fact have a filled Spec, see (39).)

The result of the movement of Kacc0 (and its possible final adjunction to BE) is that the transitive verb’s Case is never assigned. The object DP therefore has to get nominative Case in Spec,IP; and this necessitates the suppression of v’s argument, since (otherwise) both DPs would be competing for the same Case. This (then) explains how passive morphology suppresses the subject’s theta role and the verb’s Case.

We must naturally extend our claim about BE, namely that it obligatorily selects a KP, to its -ing complement in clauses with imperfective aspect:

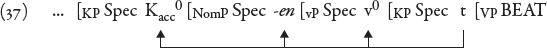

We shall follow the pattern of our analysis of perfective aspect: -ing itself (we shall say) is only a nominalizer; it does not in itself bear the aspectual meaning. We shall take the imperfective aspect to be an abstract element; and assume that it is “paired” with a Case—possibly nominative Case (but see fn. 17 below). The structure involved could be something like:

Again (as in the case of the structure postulated for perfective aspect), the Spec of the KP selected by BE is never filled in the surface; otherwise in (35), John should be able to turn up to the right of BE with a nominative Case, and also (by minimality) be unable to reach Spec,IP (* Is Johnnombreaking the window). So we shall say that here too, the K selected by BE obligatorily adjoins to it. (In a configuration other than (35), the Spec of KP can be filled, cf. (40).)17

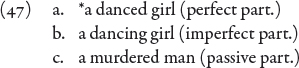

Now let us look at adjuncts. Apparently, an adjunct also (like the complement of BE) must have Case; which means, in hierarchical terms, that the highest phrase in an adjunct must be a KP. This assumption is needed to understand the possibility of a passive participle as an adjunct, as in:

In our analysis of the passive, we claimed that it is the need of BE to select a KP as its complement that induces the Kacc0 paired with v0 to move up to be the head of BE’s complement (see (33)). But there is no BE in (36). It must be an independent requirement, namely the need of an adjunct to be headed by Case, which induces the same movement in a passive participle adjunct:

The imperfect participle also can be an adjunct, cf.

Here again, we shall assume that there is a KP as the highest phrase of the adjunct. The Case here is the one “paired” with the imperfect aspect element which is abstract, see (35).18

Since there is no BE to attract to itself the K0 head of the adjunct, the latter can have a filled Spec. This possibility is illustrated in (39) and (40):

Note (incidentally) that the possibility of a lexical ‘subject’ in adjuncts like these is strong evidence that there is a KP at the left edge of these adjuncts.

However what is noteworthy is that a perfect participle cannot be an adjunct, with or without a ‘subject’.

Let us say that in English, the dative Case associated with the perfective aspect has been reanalyzed as being paired with BE. (The fact that Kdat + BE is realized as have may have facilitated such a reanalysis.) Therefore, in an adjunct, where there is no BE, the Kdat cannot be generated.19 Since an adjunct must be headed by a K, the only way to ‘save’ the structure is to move up the Kacc associated with v0; and what we get (therefore) is the passive adjunct.

What we have said above about adjuncts has a bearing on Emonds’s observation about serial verbs and PPs.

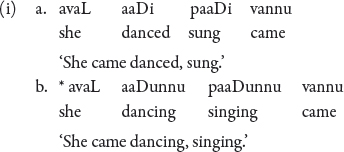

What are standardly called ‘serial verbs’ are strings of perfect participles that are adjuncts. (This is so, e.g., in Dravidian and also in African languages like Yoruba, see Jayaseelan (2003: fn. 2 and references cited there).) Since English perfect participles cannot be adjuncts, English cannot have serial verbs of this type. But English can have two other kinds of ‘serial verbs’ (a fact hitherto unnoticed), namely strings of imperfect participles and strings of passive participles:

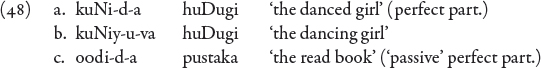

In Kannada (which has no equivalent of have), perfect and imperfect participles are both complements of iru ‘be’. Kannada has ‘serial verbs’ with perfect and imperfect participles. (It has no passive participles, although it can have perfect participles with a ‘passive reading’, see below):

Again, in the prenominal position, English permits imperfect and passive participles, but not a perfect participle:

These data suggest that prenominal elements are like adjuncts, needing their own Case. Adjectives, we can argue (given our analysis) are headed by Case. We must now assume that other prenominal elements also must have a Case head.21

Kannada permits imperfect participles, and perfect participles with both ‘active’ and ‘passive’ readings, in the prenominal position:

In sum, languages with stable Case are the ones which (i) can have ‘serial verbs’, i.e. strings of perfect participles that are adjuncts; and (ii) tend to not have P, since P is a consequence of ‘weakened’ Case.

* Some of the issues in the research reported here were initiated as part of a project on Argument Structure at Nanzan University (cf. Amritavalli and Jayaseelan 2002.) We thank the project coordinators, in particular Mamoru Saito, for the opportunity to work on the project. An earlier version of this paper was presented (in two separate papers by the authors) at the conference on Argument Structure, Delhi University, January 2003. We thank Alice Davison for making available to us an unpublished ms. of Mark Baker.

1. The optional “to it” in these sentences can perhaps be explained as follows: D/Pe0, prior to adjoining to BE, assigns to the Possessor its dative Case which is realized as to; the Possessor subsequently moves to the subject position, leaving a copy it. The movement from a Case position to another Case position (we must assume) is allowed in this case, because the moved NP continues to be in the Spec of the same element, namely D/Pe0.

2. We shall later suggest that it is the head of a Case Phrase and represent it as Kdat.

3. We may keep in mind the claim that a P which shows up on a phrasal constituent of the VP is actually generated outside VP and functions as an “attractor” of that phrase (Kayne 1999). The same claim—mutatis mutandis—ought to be applicable to a P which relates to a phrasal constituent of the DP. Case Phrases are also generated outside the VP (or DP) whose subconstituents they assign Case to. Therefore, irrespective of whether we are dealing with a Pdat or a Kdat, the element in question is generated outside DP.

4. This element is almost certainly not a member of the lexical category P, however; it is simply ‘R(elation)’. (P, for us, is a development of Case and therefore a functional category; as such, it cannot be part of a theta configuration.) But we shall keep ‘P’ for want of a conventionally accepted notation for this element.

5. The space indicated by ‘…’ implies a claim that a theta configuration need not be strictly local: in the particular case (9), functional heads like AGR0, and D0, and a Case assigner P0, may intervene between BE and the PP. (But if BE is not an essential part of the possessive configuration, we can dispense with both BE and ‘…’ in (9); nothing in our analysis is affected by this decision.)

6. Possibly (10) is also the configuration for Locatives. A figure-ground configuration may be the underlying notion here; the Possessor, or the Experiencer, or the Location being the ground, and the possessed, experienced or located thing being the figure.

As regards the two phrases related by P in (10), it may be that the more referential (definite) phrase goes into the Spec position, and the less referential into the predicative (complement) position. This means that, depending on their relative referentiality, the positions of the two phrases may be reversed. In the Hale-Keyser derivation of the denominal verb shelve, the N shelf is non-referential and is therefore in the complement position; from where it is free to incorporate into the head of the phrase.

7. For a way of dealing with a sentence like John has your article (with him), where the possessed entity is a DP, see Kayne 1993, fn. 14.

8. The “pairing” of categories appears to be a pattern in languages. In Jayaseelan (to appear) it is proposed that the English question operator obligatorily selects a FocP in the C system, and that the focusing particles only and even optionally select one in their VP-peripheral position—such selection being a property of all English operators that employ “association-with-Focus” as an interpretive mechanism. Kayne (2003) proposes that P is paired with K, and D with Num(ber). Similarly we can say that the light verb v is paired with K, the latter being responsible for the accusative Case of the Object; this K, generated between VP and v, appears to be the only K generated within vP. (One may observe that with the notion of the pairing of K with v or P, the older notion of “assigning” Case goes.)

9. Our hypothesis solves a “technical” problem that Hale and Keyser encounter with adjectives (see Hale and Keyser 2002: 25-27, 205ff.). Consider We found [the sky clear]: the sky is an argument of clear, which we would want to generate in a projection of the adjective. But if we merge the DP and the A, the mechanism of Merge will give us only a Head-Complement relation, not a Spec-Head relation. The authors’ solution is an LRS representation for A, in which A’s argument is always realized in the Spec of another head that takes A as a complement. Our analysis of adjectives obviates this problem: the subject DP of a small clause with an adjectival predicate is never merged with A; it is merged in the Spec of an abstract P0 which takes an N as complement (see (15)).

10. In an appendix (“Adpositions as Functional Categories”) to his recent work on syntactic categories, Baker (unpublished) suggests that “Ps select NPs and make them into something like an AP” (§ A.2.4, “A fuller typology of categories.”) This observation is based mainly on the distributional similarities of APs and PPs. What is of interest is Baker’s conclusion that “the functional category P is thus rather like the syntactic equivalent of a derivational morpheme” (loc. cit.).

11. Cf. Zvelebil (1990). Bhat (1994) maintains that Kannada has adjectives; Baker (unpublished) argues that Chichewa “has approximately six words that behave like true adjectives” (§4.6.2). But the attempt to “prove” that all languages “have” a lexical category A seems to us simply irrelevant. In the approaches of Hale & Keyser, Distributed Morphology, or their variants (e.g. Baker), nodes of syntactic/ lexical trees may be spelt out (lexicalized) at any point. The mechanism allows for the creation of V from N (e.g.) even if both these are “basic” categories in the language.

Our point is that (i) a type of incorporation that gives rise to what are standardly analyzed as adjectives seems to be near-absent in languages with strong morphological Case; and (ii) there is thus an implicational relationship between the absence of adjectives and the prevalence of the dative experiencer construction.

12. Bhat (1994:26) avers that the comparative construction requires an adjective within an NP. However, a dialectal fact he notes argues against this. In Bhat’s dialect, the meaning ‘he is younger to me’ can be expressed by the noun phrase tamma ‘younger brother’ instead of the adjective ‘young’. Compare ((i)a, b) below: the word tamma in (a) means ‘younger brother,’ but it simply means ‘younger’ in (b):

13. We can also say that the verb get in a sentence like We got a smell of roses is the lexical realization of Kdat + COME; i.e. the difference between have and get is that in the former Kdat adjoins to the stative BE and in the latter it adjoins to the inchoative COME.

How does roses get accusative Case in We smelt roses? The answer may have to do with a fact noted by Lumsden (1987:393): the transition from OE to EME is marked by a process of “transitivization,” by which verbs that took indirect objects start to take accusative, unmarked objects, sometimes with a change of meaning. We may note that only some of the verbs so “transitivized” became “true” transitives. Thus smell is not a true transitive because it cannot be passivized (* Roses were smelt (by us)); but love can be passivized (cf. Mary is loved (by us)). (In the dative construction, Mary is an oblique argument: To-John is love towards Mary.)

14. The on is the ancestor of the a- we find in the predicate adjectives alive, asleep, afloat, away, asunder, afire, aloft, and o’clock, cf. Lumsden (1987:317).

15. This (it seems to us) is particularly clear in the case of passives; cf.

The ‘active’ form of this sentence is (iia) and not (iib):

A time expression like ‘every day’ is inconsistent with the perfective aspect.

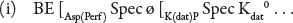

16. It is unclear how to conceptualize this “go with” relation, though. One cannot obviously say that Kdat0 obligatorily selects Asp(Perf)0. If (on the other hand) we say that Asp(Perf)0 selects Kdat0, we get the hierarchical relation (i) (since selection is “downward”):

But (i) does not satisfy BE’s requirement that its complement should be a KP. Perhaps Kdat0 moves up to head a new KP above AspP, in the manner suggested below for passive participles.

17. The Case paired with -ing can be variably nominative or accusative for some speakers (apparently), cf. John knows nothing about children, he/him being a bachelor.

An interesting puzzle is why English has no passive -ing (parallel to passive -en). Thus in (35), if we eliminate the imperfective aspect and its associated Case, we should get a structure like (i) (wherein we have shown Kacc0 as having moved to satisfy BE’s selectional requirement, cf. (33)):

This should give us a form like The window is breaking but without any imperfective meaning. But of course we don’t get any such form.

18. A puzzle is that the -ing adjunct does not carry any aspectual meaning; e.g., (38) does not say that the event ‘(John) beat Bill’ was taking place at the time of the second event, ‘John win the trophy’. This would seem to argue that the aspect phrase is not generated; but then, we should not be able to generate the KP associated with the AspP.

Possibly, the nominalizer -ing is paired with a Case of its own—which is (for some reason) generated only when Asp(Imperf) and its associated Case are not generated. Alternatively, the Case here is ambiguously associated with Asp(Imperf) or -ing. Either hypothesis would (then) also explain the puzzle noted in fn. 17, namely that there is no passive -ing form corresponding to the passive -en form.

19. We must add, in view of what we said about -ing in fn. 18, that -en has no Case of its own.

20. A puzzle is that Malayalam allows only perfect participles, and not imperfect participles, as serial verbs; cf.

Since a great deal still needs to be understood about the Dravidian aspect system, we will not go further into this parametric difference between Kannada and Malayalam.

21. Interesting questions arise in this connection. Case elements that head participial adjuncts can have their Spec positions overtly filled, cf. (39-40). Why doesn’t this happen for prenominal elements? An Adjective’s Case (we can say) is “absorbed” by the N that adjoins to it; so a phrase in its Spec cannot get Case. For prenominal participial elements, bearing in mind the raising analysis of relative clauses, one might argue that the ‘modified’ NP passes through the Spec of the participial’s KP: i.e., in a phrase like the stolen letter, there may be a trace of letter in the Spec of the KP of stolen.

References

Amritavalli, R. & K.A. Jayaseelan. 2002. Syntactic categories and lexical argument structure. In Complex Predicates and Argument Structure: A Comparative Study on the Syntactic Representations of the Argument Structure (Research Report for the Ministry of Education Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research—Research Leader: Yasuaki Abe), 9–34. Research Center for Linguistics, Nanzan University.

Bhat, D.N.S. 1994. The Adjectival Category: criteria for differentiation and identification. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Emonds, J.E. 1985. A Unified Theory of Syntactic Categories. Dordrecht: Foris.

Freeze, R. 1992. Existentials and other locatives. Language 68, 553–595.

Hale, K. & S.J. Keyser. 1993. On argument structure and the lexical expression of syntactic relations. In K. Hale and S. J. Keyser, eds., The view from Building 20: Essays in honor of Sylvain Bromberger. Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press.

Hale, K. & S.J. Keyser. 2002. Prolegomenon to a Theory of Argument Structure. Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press.

Jayaseelan, K.A. 2003. The serial verb construction in Malayalam. In V. Dayal and A. Mahajan, eds., Clause Structure in South Asian Languages, 67–91. Kluwer.

Jayaseelan, K.A. (to appear) Question movement in some SOV languages and the theory of feature checking. Language and Linguistics.

Kayne, R. 1993. Toward a modular theory of auxiliary selection. Studia Linguistica 47, 3–31. [Included in R. Kayne Parameters and Universals, 107–130. New York: Oxford University Press. Page references to this volume.]

Kayne, R. 1999. Prepositional complementizers as attractors. Probus 11, 39–73. [Included in R. Kayne Parameters and Universals, 282–313. New York: Oxford University Press.]

Kayne, R. 2003. Some remarks on agreement and on Heavy-NP Shift. Ms., New York University.

Lumsden, J.S. 1987. Syntactic Features: parametric variation in the history of English. Doctoral dissertation, MIT.

Szabolcsi, A. 1983. The possessor that ran away from home. The Linguistic Review 3, 89–102.