K. A. Jayaseelan

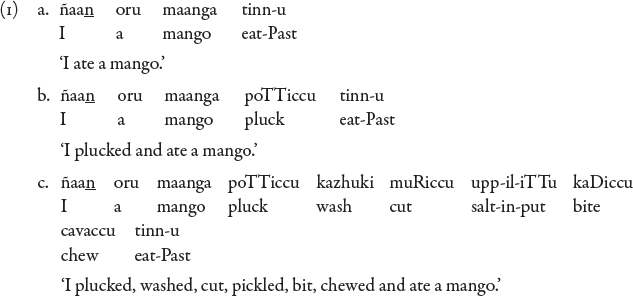

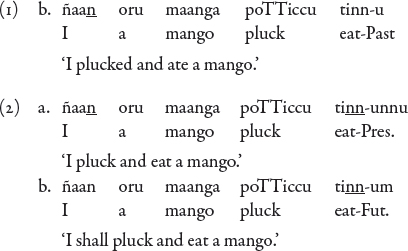

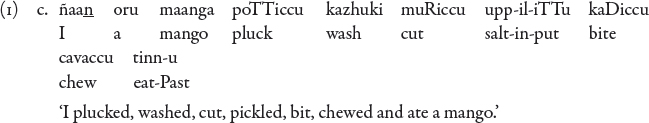

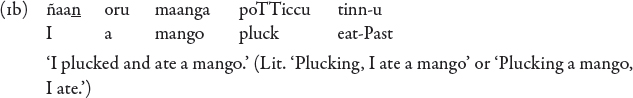

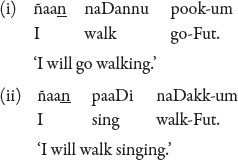

A very noticeable feature of Dravidian syntax is that sentences very often end with a string of verbs.* Consider the following Malayalam sentences:1

The string of verbs at the end can be lengthened to any extent depending only on one’s ingenuity and patience! It might appear that it is generated by an iterable syntactic process, like conjunction.

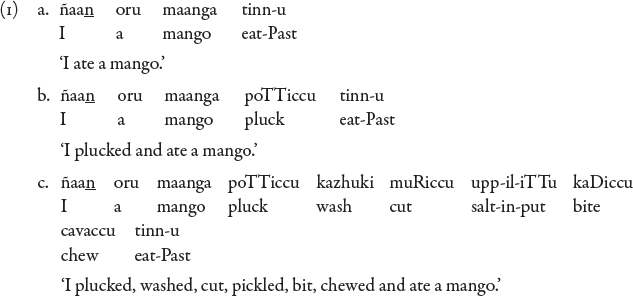

It is not conjunction, however. For one thing, there is no conjunction marker. More to the point, only the last verb is finite, i.e. marked for Tense. Malayalam has no subject-verb agreement, but other Dravidian languages do. In these languages, only the last verb is marked for Tense and Agreement. Thus compare (1b) (repeated below) with its present and future tense variants, (2a) and (2b).

Only the last verb changes to indicate the change of Tense; the non-final verb is invariant.

This invariant form of the non-final verb is identical in Malayalam with the past tense form of the verb. I.e., it is a “frozen” past tense form, which carries no obvious meaning of past tense.2

Let us (hereafter) refer to this type of series of verbs as “serial verbs”(SVs), and to the construction as a whole as the “serial verb construction”(SVC). Collins (1997: 462) gives the following ‘definition of SVC’:

A serial verb construction is a succession of verbs and their complements (if any) with one subject and one tense value that are not separated by any overt marker of coordination or subordination.

Our construction appears to fit this definition. I shall later present some evidence suggesting that the stipulation of ‘one subject’ may need to be removed from this definition. In traditional grammars of Dravidian languages, SVs were called “conjunctive participles”, to indicate their conjunction-like semantics and their non-finiteness.

SVCs are ubiquitous in Dravidian. The reason is that much of the work of function words in a language like English is done by SVs in these languages. Also, Dravidian uses SVs to describe many actions for which English has a single verb. Let me illustrate.

As seems to be standard in languages with SVCs, the notion ‘bring’ is expressed by ‘take-come’:

In ‘take away’, the function of ‘away’ is filled by an SV:

koNDu (‘take’) also figures as the instrumental postposition:

The same form is also the postposition corresponding to ‘because’:

The postposition ‘from’ is an SV:

The notion ‘about’ is expressed by an SV meaning ‘stick or adhere (to)’:

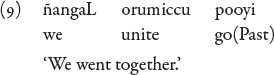

The adverb meaning ‘together’ is an SV formed from the verb orumik’k’ ‘unite’:

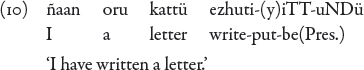

Aspectual meanings, which are expressed by auxiliary verbs in English, are expressed by SVs in Dravidian:

Note that the perfective aspect is expressed by a three-verb sequence: the content verb (here ezhuti), a verb iTTu ‘put or drop (down)’ indicating the finishing of the action, and a verb uNDü which is the existential ‘be’ that usually translates the English verb ‘have’. All but the last verb are in the “frozen” past tense form of SVs.4

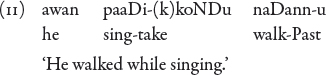

The SV koNDu ‘take’ is used to express the durative aspect, very much like the preposition ‘while’ in the English gloss of (11):

As in many languages which have SVCs, the complementizer of finite embedded clauses is an SV meaning ‘say’:

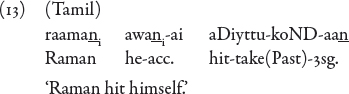

In Tamil, Telugu and Kannada (but not in Malayalam), “reflexivization” of a pronoun is done by means of an SVC—specifically, by adding koLL/koND ‘take’ to the SV form of the main verb:

Without the suffixed koLL/koND ‘take’, the sentence is a Principle B violation:

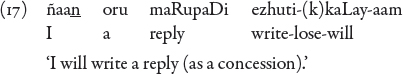

SVCs are also used to express modal notions such as “benefactive”, “permissive”, and “concessive”:

The SVs we have illustrated in this section—and described as having postpositional, aspectual and modal functions—are to be distinguished from the SVs we first looked at, i.e. the SVs of (1) and (2). Consider (1c) (repeated below):

Here, each of the verbs retains its primary meaning; and the meaning of the verbal sequence is compositional. This is not the case with the SVs we looked at in the present section; e.g., consider the “concessive” meaning of kaLay- ‘lose’ in (17); or the aspectual meaning of iTTu ‘put’ in (10).

When we later look at the syntax of SVCs, I shall suggest that the two classes of SVs perhaps ought to be given different syntactic analyses. Anticipating a little, let me note here that the SVs with postpositional meanings have probably been reanalyzed as postpositions; and that the SVs with aspectual and modal meanings have probably been reanalyzed as auxiliary verbs, which means that they take a VP complement and no longer have their own argument structure.7

Let us first look at the type of SVs we illustrated in (1) and (2). It is tempting to generate these SVs as what they look like on the surface—a string of verbs:

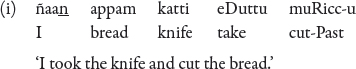

But this will not do. Each verb can have its own direct object or other complement, its own adverbial modifier, etc.

The Vs of an SVC must (therefore) be the heads of (at least) VPs.

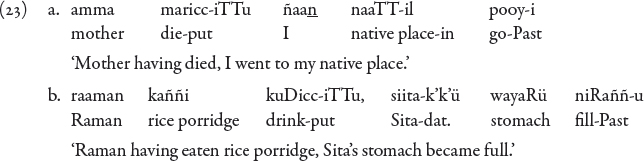

There is reason to think that in the case of these SVs, we are in fact dealing with clauses; that, like the English gerund, we have here a non-finite clause with a controlled PRO subject. Two supporting pieces of evidence are the following. Pieter Seuren (1990) notes that in some languages with SVCs, one finds (what he calls) “subject spreading”, i.e. semantically vacuous copying of the matrix subject (sometimes combined with copying of the matrix tense/aspect markings); he cites the following examples:

Although this might be “mechanical” copying (as Seuren maintains), it stands to reason that there must already be a position in the phrase structure for this process to copy into; therefore there must be a subject position, and (for tense copying) an INFL position, in the SVCs of these languages.

A more telling piece of evidence comes from Malayalam. As I first pointed out in Jayaseelan (1984), there is an SV -iTTu ‘put’ in Malayalam, which signifies the perfective aspect (see (10) above), and which licenses a lexical subject for the content verb (also an SV) which it occurs with:

Without the -iTTu, a lexical subject is not possible:

Here in (23a,b) we have an SVC with its own subject, which is not coreferential with the matrix subject.

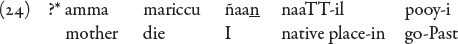

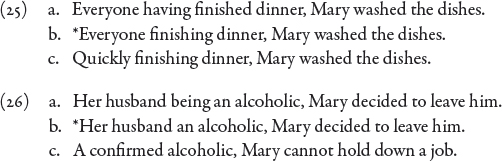

The parallelism with the English gerundial “absolute construction” is (in fact) striking. As I pointed out in Jayaseelan (1984), in both the English construction and the Malayalam SVC, a lexical subject is licensed only by the presence of an aspectual verb. For the Malayalam case, we have seen the contrast between (23a) and (24); for English, consider the following:

If the gerundial clause has a have or be, a lexical subject is licensed; in the absence of have or be, only a PRO subject is possible.

What the evidence of sentences like (23) (also Pieter Seuren’s evidence) and the parallelism with the English gerundial absolute construction suggest, is that each SV (of the type we are looking at here) is the verb of an underlying clause. The shared subject of SVC, which is typical and which for that reason has been widely taken to be a defining property of this construction, is a case of control of PRO.

The PRO subject of the Malayalam SV is obligatorily controlled by the matrix subject; it can neither be controlled by a non-subject, nor be uncontrolled (have an arbitrary reading):

(27) cannot have the reading that ‘a mango fell and I picked it up’; it can only have the odd reading that ‘I fell and picked up a mango’.

(28) cannot have the reading that ‘I caught him while he was running’.

In this sentence, it is the police who were hiding in the bushes, not him.

We may note that the control possibilities change if the embedded clause in (29) has, not an SV, but a suffix meaning ‘when’ as its last element:

Here, either the police or he could have been hiding in the bushes. The control facts are parallel in English: in the absolute construction, PRO is controlled by the matrix subject, cf. the English gloss of (27) or (29); but this is not necessarily so in an infinitival adjunct with ‘when’, cf. the English gloss of (30).

The obligatory subject control in the case of Malayalam SVs may appear to be surprising; for, according to the literature, the African and Creole SVs instantiate both subject and object control. Cf.

About (31), Sebba comments: “Kofi is necessarily the subject of fringi; a tiki is necessarily to be interpreted as the subject of fadon since it is the stick which falls rather than Kofi; and native speakers confirm that it is likewise the stick which hits Amba, so that a tiki is the subject of naki.” Likewise in (32), it is the trousers (not I) which “go till my knee”.

It may be necessary however to investigate whether fadon (“fall down”) and go te (“go till”) in Sranan are still functioning as verbs or have been reanalyzed as prepositions. In Malayalam, the only exceptions to obligatory subject control are some SVs which have apparently been completely reanalyzed as postpositions:

weeNDi—which corresponds to ‘for’ in Malayalam—is the SV form of a verb meaning ‘want’, with a very defective paradigm; it occurs in a sentence like:

In (33)—assuming a PRO subject in PPs—the PRO is coreferential with ii pustakam ‘this book’. Consider also (35):

Here, patti and kuRiccu, which do duty for ‘about’ in Malayalam, are SVs formed from verbs meaning (respectively) ‘adhere (to)’ and ‘aim (at)’. The PRO in (35) (assuming one) is, arguably, controlled by oru leekhanam ‘an article’; for it is the article (not I) which “adheres to” or “aims at” him. But object control in these cases, I wish to suggest, is possible only because weeNDi, patti and kuRiccu are no longer functioning as verbs, but have been reanalyzed as postpositions. (It is possible that PPs do not contain PRO, and are interpreted by some other means than control of PRO.) The other SVs exhibit obligatory subject control of the PRO subject.8

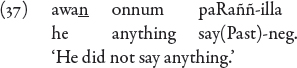

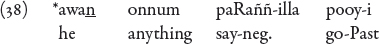

Another claim in the literature is that an SV may not contain negation (see Seuren 1990). This claim is not true of Dravidian. We have already given an example of a negated SV in fn.2; here is another:

We may note (however) that the negative affix -aa which figures here, is not the normal negative marker of the language, which is illa/alla:

illa/alla is a finite verb in its own right, and therefore may not occur as an SV (which is non-finite):

The affix -aa is a survival of an old Dravidian negation strategy, which in present-day Malayalam shows up only in SVs and relative clauses. The point we are making is that, whether (or not) a language allows negation in its SVs may depend on the negation devices available to it; and that negation is not inherently incompatible with SVs.

Nor is Passive incompatible with SVCs. A sentence is passivized in Malayalam by means of a verb peD (‘happen to’ or ‘suffer’) added to a nominalized form of the content verb.

The SV form of peD (identical in Malayalam with the past tense form peTTu) in used in a passive SVC:

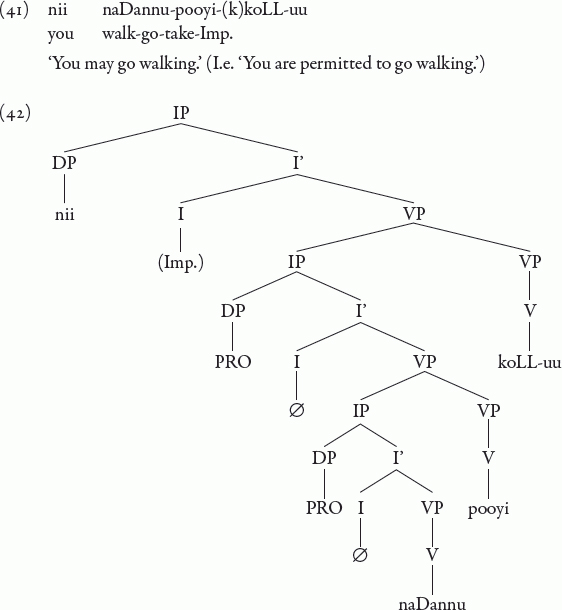

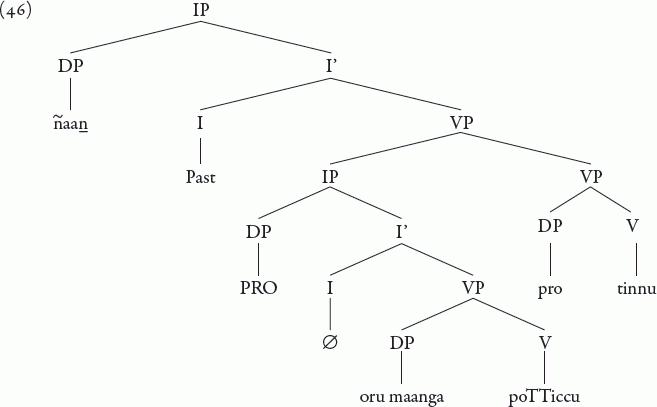

I suggested that an SV—at least an SV of the type illustrated in (1) and (2)—is generated within a structure like the English absolute construction. Pieter Seuren compares it to the phrase fishing in John went fishing (Seuren 1990). The analysis I have in mind is that an SV is the verb of a non-finite clausal adjunct. It has an INFL node, but being non-finite, its INFL contains neither Tense9 nor AGR (cf. -ing which heads the English -ing clauses). I shall represent this clause, call it the “SV clause”, as left-adjoined to VP; although determining its real position will depend on determining the position of adverbial clausal adjuncts in SOV languages. Thus a sentence like (41) can be represented as having the structure (42):10

This structure can be straightforwardly extended to a sentence like (43) in which each of the Vs has a direct object. We may assume that (43) has a structure like (44):11

In a sentence like (1b) (repeated below), we come across the classic problem of “object sharing” in SVCs, which has generated a lot of debate.

The first question is: which verb does the lexical direct object go with? We could generate it as the direct object of the finite (final) verb tinnu (‘ate’):

To account for the surface word-order, we could say that oru maanga (‘a mango’) has been scrambled to the left of the SV clause.13

An alternative is to generate the lexical direct object in the SV clause, and pro in the other VP:

We prefer (46) over (45), for two reasons. Firstly, the following sentence is more or less unacceptable:

Therefore, if we start from (45), we shall have to make the scrambling of oru maanga to the left of the SV clause obligatory. This seems odd, because scrambling is generally taken to be an optional rule.14 Secondly, the string oru maanga poTTiccu can be scrambled to the left of the matrix clause:

This shows that oru maanga poTTiccu is a constituent—as is the case in (46), but not in (45). (If we start from (45), even if we scramble oru maanga to the left of the SV clause, it will not form a constituent with poTTiccu.15)

We assume (46), then. The reader will have noticed (with interest) the pro in (46), which represents the ‘missing’ object. This solution to the so-called “object-sharing” problem is clearly workable in Malayalam, because the language allows an argument to surface as a null element in any position except the object position of a postposition. The null element in question is not a variable but a pronominal, going by all the standard tests such as the possibility of being A-bound (Savio 1995, Jayaseelan 1995). An interesting question is whether this explanation can be extended to the African and Creole languages in which “object-sharing” was first noticed; e.g.

The answer will depend on whether these languages have the same possibilities with regard to the distribution of pro. Without going into this question, let us simply note here that Collins (1997), in his analysis of Ewe SVCs, in fact postulates a pro to mediate “argument sharing”.

Some questions about “argument sharing” still remain, however. Consider the following:

In (50a), tar ‘give’ has a modal meaning, something like ‘for (someone’s) benefit’. (Cf. the English benefactive dative of ‘I’ll call you a taxi’; English sometimes uses a modal verb for such meanings, cf. the ‘may’ of permission.) But in (50b), we simply have two actions. In fact, the equivalent of (50b) is not possible in some other cases:

The (b) sentences here are bad, because it makes no sense to ‘give a door to somebody’ or ‘give a story to somebody’. The sentences are syntactically fine, with the very odd “two-actions” reading indicated in the English glosses.

Note some points about the syntax of these sentences. The dative argument belongs to the verb tar ‘give’; the verb tuRakk ‘open’ certainly has no dative argument in its subcategorization:

The verb paRay ‘say’ arguably can have a third argument (‘XP say YP to ZP’); but in Dravidian, this third argument of ‘say’-verbs has a special Case called ‘second dative’:

The Case of the dative argument nin-akkü (therefore) clearly comes from tar ‘give’.

A Baker-type analysis (Baker 1989) predicts that in a serial verb construction, a shared argument of the verbs will be generated in the complement position of the first verb, and an unshared argument will be generated in the complement position of the verb to which it belongs. This predicts only the deviant (51b)/(52b); it cannot generate (51a)/(52a).

We may now ask: what is the second argument of tar ‘give’? What is given is not ‘the door’ or ‘the story’, but (in a sense) ‘opening the door’ and ‘telling the story’. Suppose (then) we generate the SV clause as an argument of tar ‘give’. In general, an SV clause is unlike an English gerund—it does not have the distribution of an NP (cannot substitute for an NP). But we can say that as an exception, in cases like (51)/(52), it fills an argument position. Alternatively, we can say that tar ‘give’ in (51)/(52) has the function of an auxiliary verb, and that the structure containing the SV (in this case) is not a clause but a VP—the VP complement of the auxiliary verb. We must assume in this second analysis that when the verb is converted into an auxiliary verb, its theme argument is suppressed or eliminated; this seems acceptable enough. But what is problematic is the fact that the verb’s ability to take a dative argument is retained. This makes it quite unlike an auxiliary verb.

Sentences like (51a) and (52a) should make us appreciate the difficulty about postulating a clean division between two classes of SVs—one consisting of ‘full’ verbs, the other consisting of ‘light’ verbs—which have different syntactic structures. The different structures one would want to postulate for the two classes would presumably be the following: The full verbs can take their normal complements, and are underlyingly the heads of (at least) VPs. The light verbs are like auxiliary verbs, contributing aspectual and other meanings; and they are generated in the configuration appropriate to auxiliaries, namely they select a VP (but have no arguments). But in the two aforementioned sentences, tar ‘give’ is clearly a light verb; it has a non-primary (“bleached”) meaning. And yet it seems to retain all its three arguments.

Let us now look at another property of (51a) and (52a), which may give a clue to its structure. An argument (in Malayalam) can normally be moved by scrambling (subject only to some specificity conditions); and even the VP complement of an auxiliary verb can be topicalized, as we know from English, cf. Buy the car, I will! But in (51)/(52), the two verbs cannot be separated:

(These sentences have the same odd reading as (51b) and (52b).) To account for the inseparability of these verbs, we must assume that they configure in an adjunction structure. Specifically, we assume that in cases like (51) and (52), where the second verb has a modal-like function, the verb of the SV clause adjoins to it. This is shown in (57)16:

It is not only when the second verb has a modal meaning, that the first verb adjoins to it. This adjunction must also be happening in certain sequences which look as if they have been “lexicalized”, and which have a not-quite-compositional meaning: e.g. konDu-war ‘bring’ (lit. ‘take-come’), see (3). It also happens (I think) in the use of SVs to express aspectual meaning, e.g. ezhuti-(y)iTT-uNDü ‘have written’ (lit. ‘write-put-have’), see (10). This last phrase must have the following structure:

The verbs iTTu and uNDü here (it seems to me) are clearly just auxiliary verbs.

At this point, a brief comparison with earlier analyses of SVCs seems to be in order. Baker’s (1989) analysis of “argument sharing” in terms of a double-headed VP involving a ternary branching structure, as shown in (59) (cf. Baker’s (13)):

has not found wide acceptance. Dechaine’s (1993) position is that “serialization reduces to the possibility of adjoining one VP to another” (p. 800); essentially, her structure is (60):

In (60), VP2 could be right-adjoined to VP1, or VP1 could be left-adjoined to VP2—an ambiguity which she claims is exploited by languages. Our decision to left-adjoin the SV clause to the finite verb’s VP may be said to have something in common with this analysis. (However, we adopted the adjunction structure advisedly, pending better understanding of the position of adverbial adjunct clauses in SOV languages.)

Lefebvre (1991), Collins (1997), and Carstens (1997) adopt a structure in which VP2 is the complement of V1. This has an obvious point of comparison with the structure we just proposed for some SVCs, namely the ones in which (we claimed) the lower V adjoins to the higher V. In a sentence like (51a) (we said), the SV clause (or VP) is an argument of the finite V. (It is actually the Theme argument of the finite V, see below.)

But for us, this is not the “general” structure of SVCs. The fully productive type of SVC in Dravidian, which has a string of content verbs like in (1), has a structure in which the SV represents an underlying clause which is only an adverbial adjunct of the finite V. This analysis (therefore) appears to be a departure from other current analyses.

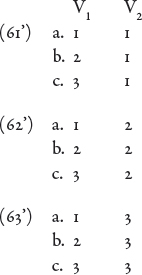

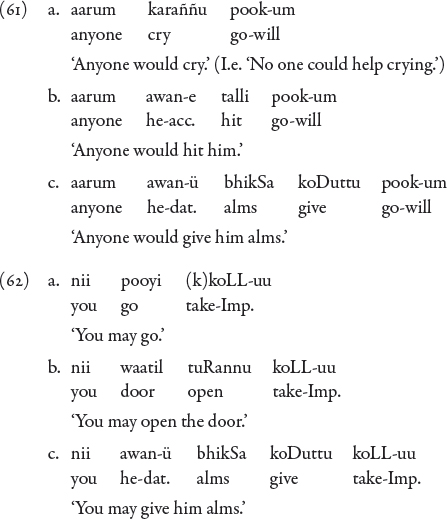

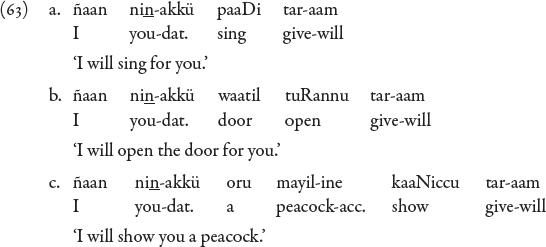

I conclude by exhibiting a set of data to show that there are no restrictions on the valency (number of arguments) of the verbs which may take part in the adjunction described in the last section. In (61), (62) and (63) (below), the valency of verbs is as shown in (61’), (62’) and (63’):

I.e., given a maximum valency of three, all the permutations are possible. (In (61), V2 is pook ‘go’, which gives the meaning of ‘not being able to help doing (something)’; in (62), V2 is koLL ‘take’, which gives the meaning of permission; and in (63), V2 is tar ‘give’, which gives the meaning of doing an action ‘for the benefit of (someone)’.)

Regarding the last sentence, i.e. (63c), there is an interesting problem. Both V1 and V2 are three-argument verbs, and the dative argument nin-akkü ‘you-dat.’ could belong to either of them. Which verb should we generate it with? It is tempting, in such cases, to argue that the problem is obviated; that after the adjunction of V1 to V2, the two verbs may amalgamate their arguments (theta roles), and that they may (then) together assign the Goal theta role to the dative NP (and similarly, perhaps, the Theme theta role to the accusative NP). This solution would be in the spirit of Baker’s (1989) “argument-sharing” analysis. I however prefer to generate nin-akkü as an argument of V2, and to satisfy the theta-grid of V1 by generating pro for the latter’s dative argument:

We need more compelling evidence, I think, before we enrich the theory with powerful devices like “argument-sharing”.

A final point regarding the theta roles of the verbs in the above sentences: Note that when the clause containing V1 substitutes for an argument of V2, it is always the Theme argument which is substituted. This may be a general phenomenon, cf. the formation of complex predicates in English—e.g. take a walk, put the blame on NP, give permission to NP (see Jayaseelan 1988).

In this paper, we studied a ubiquitous structure of Dravidian syntax, namely the serial verb construction (SVC). Dravidianists have often talked about this construction under the name of “conjunctive participles”; but without relating it to SVC or placing it in the context of the study of SVC in the languages of the world.17 We exhibited its numerous functions (section 2): some SVs are ‘full’ verbs, some are ‘light’ verbs; the ‘light’ verbs give meanings like ‘benefactive’, ‘concessive’ and ‘completive’, and also fill the functions of adpositions, adverbs and auxiliary verbs. We examined the properties of SVC (section 3): we argued (departing from previous analyses) that at least in the case of ‘full’ verbs, each verb of a string of such verbs corresponds to a clausal structure; and argued that the clauses corresponding to the non-final verbs are adverbial adjuncts. As regards the structure of SVC (section 4), we represented the ‘SV clause’ as left-adjoined to a VP; and we dealt with “argument sharing”—a classic problem regarding SVCs—by generating a pro. A ‘light’ verb (we suggested) may have only the structure of an adposition, or adverb, or auxiliary verb (depending on its function). But we discussed some “in between” cases, where an SV which does not have its primary meaning—and therefore must be considered a ‘light’ verb—nevertheless seems to be able to take its own (unshared) argument. The fact that in some of these SV sequences the verbs are ‘inseparable’, we tried to account for by adjunction (via head-to-head movement). We also made some observations (section 5) about the valency of the verbs which may enter into a ‘full verb-light verb’ sequence.

Since the time when Seuren (1990) wrote that “[d]ata on the relatively few languages with other [i.e. non-SVO] basic word order patterns are … scarce and, often, unreliable …,” there have been important studies of verb serialization in SOV languages. Notably, Carstens (1997) has used SVC data from Ijo (an SOV language) as arguments for the correctness of the predictions of LCA (Kayne 1994). I skirt the SOV/SVO issue in the present paper, wishing to focus on other structural questions about this construction. But I hope to have also contributed new SOV data to the ongoing SVC debate, and thereby to have further mitigated the cause for Seuren’s complaint.

* An earlier version of this paper was presented at a seminar on Verb Typology at the University of Trondheim (Norway) in September 1996.

1. A note on the transcription: /t, d, n/ are dental; /t, n/ are alveolar; /T, D, N, L, S/ are retroflex; /s’/ is palato-alveolar; /k’/ is palatalized; and /R/ is an alveolar tap.

2. A caveat: It has been claimed that serial verbs correspond to a temporal sequence of events; that for each verb, the event denoted by it is preceded by the events denoted by the preceding verbs. (This claim has been termed the Temporal Iconicity of the serial verb construction; see Li 1993.) Given this, it could be argued that the past tense form of the non-final verb is not devoid of past tense meaning. Thus in (2b), with respect to the ‘eating’ (which is in the future), the ‘plucking’ has already taken place (is in the past).

Amritavalli & Jayaseelan (2000[2002]) (see also Amritavalli 2000) argue that Dravidian has no Tense, only Aspect; and that finiteness is marked by a Mood Phrase. In Malayalam this Mood Phrase has no morphological realization when it is indicative; but in other Dravidian languages, agreement is the reflex of the indicative mood. What has hitherto been treated as the past tense is the perfective aspect (according to this view). What we must now say about the serial verb construction is that all but the last verb has an invariant perfective aspect. Significantly, some African languages with SVCs also have been reported to mark their SVs with an invariant perfective aspect marker: e.g. Yoruba marks them with a perfective aspect marker -rV, see Dechaine (1993, 809-810). This perfective aspect can then be explained in terms of the Temporal Iconicity of the construction.

This explanation (in turn) is not entirely straightforward (however). Consider the following sentences:

In (i), the ‘going’ does not follow the ‘walking’. Again in (ii), the ‘singing’ and the ‘walking’ are simultaneous. Also, when the non-final verb is negated, cf. (iii):

the negative suffix -aa is attached to a non-perfective stem. (This second argument, however, can be got around if the ill-understood augment -te is a marker of perfectivity.)

A morphological note is in order here: Every Malayalam verb has two stems, e.g.

The first one is the base for the imperfective suffix (and also for some other suffixes); and the second one is the base for the perfective suffix (and also for some other suffixes). The point is that the non-final verb of the serial verb construction—except when it is negated—has both the stem and the suffix of the perfective form, and so is identical in Malayalam with the finite “past tense” form. In other Dravidian languages, which mark agreement also on the finite verb, this verb will be distinguishable from the finite “past tense” form by the absence of agreement. (In Malayalam also, however, the non-finiteness of this verb is not in any doubt: an inherently finite negative verb illa cannot appear in this slot, see (38) below.)

3. A reviewer queries if koNDu and war are written as one word, and if so, whether this is significant. Indeed, it is. As I shall say later, some SV sequences are “lexicalized”, and the verbs of such sequences cannot be separated by any intervening material; these verbs tend to be written as one word. I shall suggest an adjunction analysis for them: one verb is adjoined to another by head-to-head movement. See the discussion of (57) and (58) below.

4. If we follow Amritavalli & Jayaseelan (2000[2002]), the verb ezhuti itself is perfective; so one might ask why another verb, iTTu ‘put’, is needed to indicate the finishing of the action. But the fact is that *ezhuti-uNDu is ungrammatical. This could be a quirk of uNDu (it selects only iTTu ?); because the corresponding Tamil form is grammatical: ezhuti-irukku ‘write-be’.

5. In present-day Malayalam, the verb for ‘say’ is paRay; the obsolete verb enr ‘say’ now survives only in the complementizer ennü. But in Tamil, enr is still the regular verb for ‘say’, and its SV form enru is the complementizer. (If the matrix verb is enr, the complementizer is obligatorily dropped in Tamil—perhaps to avoid the repetition ‘say-say’.)

6. Strictly speaking, koLL ‘take’ in this construction only means that the specified action is for the benefit of the addressee (or a third person). When the agent of the action is ‘you’ as in (16), this gives the meaning of permission; but cf.

7. Sahoo (2001) also tries to make a similar demarcation between two classes of SVs: in one class, all the verbs have their primary meanings and can have their own independent arguments; in the other class all but the first verb is a ‘light’ verb. She analyzes them as corresponding (syntactically) to ‘VP serialization’ and ‘V serialization’.

But, as we shall show later, it is not possible to make a neat division between these classes; because we encounter some “in between” cases, where a verb which is a ‘light’ verb with respect to its meaning contribution to the sentence nevertheless has its own argument which it does not share with the main verb.

8. Another possible analysis of sentences like (31) and (32) is to say that the Theme argument of the first verb (fringi ‘fling’ / hari ‘pull’) is suppressed; and that what looks like its direct object (a tiki ‘the stick’ / mi bruku ‘my trousers’) is actually generated as the subject of the second verb. This happens in English, cf.

(ii) They ate us out of hearth and home.

One shaves one’s face, not one’s beard; therefore, ‘his beard’ cannot be the Theme argument of ‘shave’ in (i). Again in (ii), ‘us’ cannot be the Theme argument of ‘eat’. In both cases, the Theme argument of the first verb is suppressed. (See Jayaseelan 1988 for an analysis of this type of causative construction in English.)

9. But if we accept the analysis of Amritavalli & Jayaseelan (2000), an SV has perfective aspect, which is morphologically marked on it—-u in the case of some verbs, -i in the case of other verbs. (In the diagram (42), I have shown the INFL node of the clause in question as occupied by a null element (‘Ø’).)

10. If koLL- ‘take’ has been reanalyzed as an auxiliary (it is certainly a ‘light’ verb, with a non-primary meaning), the structure shown in (42) will have to be modified: koLL- will select a VP as its complement, possibly the VP containing pooyi. The latter VP will have the IP containing naDannu adjoined to it.

11. In (44), as indeed also in (42), we are ignoring important questions about how SOV word-order is generated. If Kayne (1994) is right, the direct objects katti (‘the knife’) and appam (‘the bread’) are in SPEC positions of functional heads above VP. Thus, in the case of appam (‘the bread’), the position can (optionally) be higher than the SV clause, cf.

12. The reader may want to compare (43) with (5), which has koNDu in the place of eDuttu. koNDu, in its use in (5), has probably been reanalyzed as a postposition. Present-day Malayalam uses only eDukk/eDutt for the literal meaning of ‘take’.

13. See fn. 11. If one were to adopt Kayne’s (1994) position, direct objects must (in any case) move to the SPEC position of a functional head above VP in an SOV language; so one can say that (in this case) it has moved to the SPEC position of an even higher functional head.

14. A reviewer objects that scrambling as an optional movement rule is problematic, given Minimalist assumptions. But actually, this problem is completely orthogonal to our argument. Thus, suppose we go along with the proposed solution of Boškovic & Takahashi (1997): generate a “scrambled” phrase in its surface position; in the LF component, lower it to its theta position. Our argument now would be that in order to prevent the generation of (47), we would have to prohibit the generation of oru maanga in its theta position!

15. Nor can (48) be generated from (45) by two separate scrambling movements: first, of poTTiccu from the SV clause (or, for that matter, of the whole SV clause); then, of oru maanga from the matrix VP. For in fact, the second movement is disallowed: an indefinite, non-specific NP cannot be scrambled (see Jayaseelan 2001).

If more evidence were necessary (in support of (46) and against (45)), we can try “spelling out” pro as a lexical pronoun. What we get is the following:

This supports (46) over (45).

16. But see again fn. 11. If we adopt the Kayne hypothesis, nin-akkü ‘you-dat.’, and the SV clause containing waatil ‘(the) door’, will be in the SPEC positions of functional projections above VP—moved there by a process which applies quite generally to all VP-internal elements in SOV languages. In the underlying structure, the SV clause will be lower than tar-aam, in fact (if we adopt the suggested analysis) in the complement position of tar-aam. Now tuRannu could adjoin to tar-aam by head-to-head movement; and this could take place before the SV clause is moved out of the VP.

Our idea of adjunction has an echo in Collins (1997), who argues that “[t]he second verb incorporates into the first verb in an SVC” (p. 485); but his incorporation takes place only at LF.

17. Steever (1988) used the term “serial verb formation” (SVF) to refer to certain structures found in Old Dravidian; but it is doubtful if these structures have anything to do with the structure we are discussing in this paper. Thus consider one of Steever’s examples (Old Tamil):

This appears to be a main verb followed by an auxiliary verb (although it is indeed remarkable that both verbs are inflected for agreement).

References

Amritavalli, R. 2000. Kannada clause structure. In The Yearbook of South Asian Languages and Linguistics 2000, ed. Rajendra Singh. New Delhi: Sage.

Amritavalli, R. & K.A. Jayaseelan. 2000[2002]. Finiteness and negation in Dravidian. Ms. Central Institute of English and Foreign Languages, Hyderabad. [Included in CIEFL Occasional Papers in Linguistics 10 (July 2002).]

Baker, Mark. 1989. Object sharing and projection in serial verb constructions. Linguistic Inquiry 20:4, 513–553.

Boškovic, Želko and Daiko Takahashi. 1998. Scrambling and last resort. Linguistic Inquiry 29(3): 347–366.

Byrne, Francis. 1990. Some presumed difficulties with approaches to “missing” internal arguments in serial structures. Paper read at 8th Biennial Conference of the Society of Caribbean Linguistics, Belize City, Aug. 1990. Ms.

Carstens, Vicki. 1997. Implications of serial constructions for right-headed syntax. Paper presented at the 1997 GLOW Workshop in Rabat.

Collins, Chris. 1997. Argument sharing in serial verb constructions. Linguistic Inquiry 28(3):461–497.

Déchaine, Rose-Marie. 1993. Serial verb constructions. In J. Jacob, A. von Stechow, W. Sternfeld and T. Vennemann (eds.) Syntax: An International Handbook of Contemporary Research, pp. 799–825. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Jayaseelan, K.A. 1984. Control in some sentential adjuncts of Malayalam. Proceedings of the Tenth Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society, eds. Claudia Brugman et al. (pp. 623–633).

Jayaseelan, K.A. 1988. Complex predicates and theta theory. In Wendy Wilkins (ed.) Thematic Relations (Syntax and Semantics 21), New York: Academic Press.

Jayaseelan, K.A. 1995. Empty pronouns in Dravidian. Talk given at Annamalai University (Agesthialingom Endowment Lectures), August 1995. [Printed in K.A. Jayaseelan, Parametric Studies in Malayalam Syntax, Allied Publishers, Delhi, 1999.]

Jayaseelan, K.A. 2001. IP-internal topic and focus phrases. Studia Linguistica 55(1):39–75.

Kayne, Richard S. 1994. The Antisymmetry of Syntax. The MIT Press: Cambridge, Mass.

Lefebvre, Claire. Take serial verb constructions in Fon. In Claire Lefebvre (ed.) Serial verbs: Grammatical. comparative and cognitive approaches, 79–102. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Li, Yafei. 1993. Structural head and aspectuality. Language 69.3.

Mcwhorter, John H. 1990. Substratal influence in Saramaccan serial verb constructions. Paper read at 8th Biennial Conference of the Society of Caribbean Linguistics, Belize City, Aug. 1990. Ms.

Sahoo, Kalyanamalini. 2001. Oriya verb morphology and complex verb constructions. Doctoral dissertation, University of Trondheim.

Savio, Dominic. 1995. Pro drop in Tamil and English. Doctoral dissertation, Central Institute of English and Foreign Languages, Hyderabad.

Sebba, Mark. 1987. The syntax of serial verbs. An investigation into serialization in Sranan and other languages. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Seuren, Pieter. 1990. Serial verb constructions. Proceediings of the Ohio State University Mini-conference on Serial Verbs, eds. Brian D. Joseph & Arnold M. Zwicky (pp. 14–33).

Steever, Sanford S. 1988. The Serial Verb Formation in the Dravidian Languages. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass.

Voorhoeve, Jan. 1975. Serial verbs in Creole. Paper presented at Hawaii Pidgin and Creole Conference.