K. A. Jayaseelan

It is argued that the ‘dative construction’—i.e. the construction in which an Experiencer or Possessor argument is realized as a DP marked with dative Case, and the VP has the form ‘be NP’—alternates with two ‘nominative constructions’ (i.e. constructions in which the Experiencer/Possessor argument has nominative Case): one in which the VP has the form ‘have NP,’ and another in which the VP has the form ‘be AdjP’. We try to account for the three-way realization of the same underlying Lexical Relational Structure (LRS) in terms of incorporation: when the dative Case incorporates into ‘be,’ we get ‘have’; and when a Noun incorporates into dative Case, we get an Adjective.*

Let us refer to the construction illustrated by the Malayalam sentences in (1–3) below by the term ‘dative construction’. In this construction, an NP bearing a particular theta role—in (1–3) this theta role is that of the Experiencer—has the dative Case.

We may take the structure of these sentences here as representative; for it is this structure that a great many of the world’s languages use, when they express ideas like ‘being happy/sad/hungry/angry’. Typologically, it is instantiated in all the languages of the Indian subcontinent and in most of the languages of Asia. Interestingly, it was also the structure used by Old English in its so-called “impersonal construction” (see Jayaseelan (to appear) for a discussion of the Old English facts vis-à-vis the Dravidian facts).

The contrast of this structure with the corresponding English structure has been discussed a great deal in recent literature under the rubric of ‘quirky Case subjects’. What has caught the attention of linguists here is the Case contrast: dative Case vs. nominative Case on the Experiencer argument. But there is another consistent contrast here. English has an adjective where Malayalam has a noun.

This second contrast (to the best of my knowledge) has never been focused on, for whatever reason. But it will be my contention in this paper that there is a dependency between the adjective/noun choice and the dative/nominative choice for the Case of the ‘subject’.

Many languages also use the dative construction to express the notion of possession. Cf.

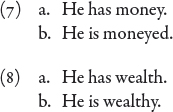

Here the NP with the Possessor theta role has the dative Case. In the English glosses of these sentences there is no adjective; this is in contrast to the English glosses of the sentences in (1–3). But there is now another contrast: where Malayalam has a verb that can only be translated as ‘be’, English has the verb ‘have’. But interestingly, in the possessor construction, although English typically uses ‘have’, it has also (in some cases) a way to express the same idea using ‘be’; but when it does this, an adjective appears. Cf.

I shall (again) claim that there is a dependency here, a relation between the be / have choice and the two choices that we mentioned earlier, namely the dative/ nominative choice and the adjective/noun choice. I shall suggest that there are three possibilities for languages to express notions like ‘being happy/sad/hungry’:

Similarly, languages have three ways—the same three ways—to express the notion of possession:

All three patterns (I shall try to show) are derived from the same underlying thematic structure, by different choices of incorporation.

Before we proceed, a fact should be noted: It has often been observed that Dravidian languages probably have no adjectives; they appear to fulfill the adjectival function by using participial forms which are transparently deverbal, or by nouns.1 Thus Anandan (1985) has argued that all Malayalam, or more generally Dravidian, ‘adjectives’ that end in -a (and the fact is that most Dravidian adjectives end in-a ) are participial forms of verbs that have the relativizer -a suffixed to them. In other words, they are ‘concealed relative clauses’. The Malayalam adjectives in the second column below are derived from the verbal roots given in the first column:

Even adjectives like nalla ‘good’, waliya ‘big’ and pazhaya ‘old’, which don’t have immediately recognizable verbal roots in the contemporary language, are derived from obsolete verbal roots that still turn up in poetry. Besides these adjectives that end in -a, Malayalam has a small class of adjectives that Anandan shows are plain nouns (going by all the syntactic tests).

In Kannada, similarly, adjectives are formed from verbs or from nouns by suffixation. Kannada (but not Malayalam, for some reason) has a process of deriving adjectives by dative suffixation to a noun, which is particularly interesting to us and which is illustrated below:

The language also has a way of deriving adjectives by suffixing -aagi (lit. ‘having become’) or -aada (lit. ‘having happened’) to nouns; e.g. ettara-vaada (lit. ‘height having happened’) ‘tall’; see Amritavalli and Jayaseelan (2003) for more details.

But the point we wish to emphasize is that the absence of the category of adjective in Malayalam, as opposed to its availability in English, is not the explanation for the ‘adjective/noun’ contrast noted above; the explanation is deeper and more interesting. It is only in languages in which, owing to processes of language change, the Case system has become destabilized that the incorporation process that gives rise to adjectives can take place (or at least, happen in a widespread manner). This point is argued more at length in Amritavalli (this volume) and Amritavalli and Jayaseelan (2003).

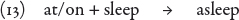

The fact that some languages of the world do not have the category ‘adjective’, suggests a line of thinking: suppose ‘adjective’ is not one of the basic categories of human languages. Consider the possibility that even in English, adjective is a derived category. There are some fairly transparent cases here, e.g. the adjective asleep, which is derived from a preposition and a noun:

Lumsden (1987: 302, 317) points out that in the transition period from Old English to Early Middle English (the 12th century), the “loss of Case signals … encouraged speakers to use more prepositions”, and that (during this period) many prepositions—to, of, on and at—were used interchangeably; also that the EME on is the ancestor of the a- we find in the predicate adjectives asleep, alive, afloat, away, asunder, afire, aloft, and o’clock. Thus, if English permitted a sentence like The child is at sleep or The child is on sleep, we would say that the complement of the copula is a PP; but in The child is asleep, we say that the complement is an adjective. We shall argue that the incorporation of a noun into a preposition (or Case) is the process by which all adjectives are derived.

Our discussion in Section 1 may have given the impression that the dative construction is a typological property of the languages of India and (much of) East Asia, which distinguishes these languages from (Modern) English. But the fact is that English too has something like the dative construction, although the English dative construction is much more limited in its privileges of occurrence.

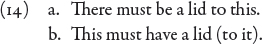

Consider the following pair of sentences:

The (a) sentence has (what we may call) a ‘dative NP’ to this ; in the (b) sentence it corresponds to a nominative NP which is the subject. There is also a contrast in the verb, be in the (a) sentence and have in the (b) sentence. The other NP in these sentences, namely a lid, is subject to a non-referentiality constraint; thus one cannot have a definite NP in its place: * There must be the lid to this ; * This must have the lid (to it). The relation between the two NPs is one of possession; thus one speaks of “this vessel’s lid”. The reader will immediately recall the way Malayalam expresses the relation of possession; we repeat (4) here:

Here, the possessor NP has the dative Case in Malayalam, and the nominative Case in the English translation. The verb is uNDə ‘be’ in Malayalam, have in the English translation. But the fact is that, if we make allowance for the word order difference and the fact that Malayalam is a pro-drop language while English requires a pleonastic there in the subject position, the Malayalam sentence is completely parallel to the English Sentence (14a). The interesting thing that we have just demonstrated in (14), then, is that the structural contrast between the Malayalam sentence and its English translation is instantiated within English.

Here are some more examples of the structural alternation illustrated in (14):

In English, unlike in Malayalam, only a very restricted type of possession relations can be expressed by the dative construction; e.g. the possessor cannot be animate, as shown by the following contrast:

The Experiencer relation also can be expressed in English by the dative construction; but here the restrictions are even narrower and more difficult to define. Cf.

The verb be (for some reason) cannot appear in the dative construction here, cf. * There is to him a feeling of boredom. Also, the NP denoting the ‘experienced’ thing has some kind of a heaviness constraint, because the sentence is marginal when the N is not modified, cf. ?? There came to us a smell.

We now come to the central problem that we wish to address in this paper, namely the one posed by the three-way alternation illustrated in (9) and (10). Our analysis takes off from Kayne’s (1993) account of the be/have alternation. Kayne bases his analysis on some facts regarding the behavior of the possessive in Hungarian described by Szabolcsi (1983), and on Szabolcsi’s analysis of these facts. In Hungarian, the possessive construction has a verb van which can be translated as ‘be’. It takes (according to Szabolcsi) a single DP complement, which contains the possessor DP. The possessor DP occurs to the right of (lower than) the D0 head of be ’s complement. The full structure is as follows:

If DPposs stays in situ, it has nominative Case. But if it moves to Spec of D0, it gets dative Case; it may now move out of the DP entirely, but the dative Case is retained. If D0 is definite, the two movements mentioned above are optional; but if D0 is indefinite, these movements are obligatory. Thus the possessive construction in Hungarian would be (something like) To John is a sister, where to John is a dative-marked DP.

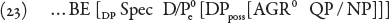

Kayne claims that the English possessive construction has a substantially parallel underlying structure, with just a few parametric variations. The verb is an abstract copula, BE, which takes a single DP complement. A difference is that English has a nonovert “prepositional” D0 as the head of this DP, which Kayne represents as D/Pe0. The structure is:

In English, AGR0 cannot license nominative Case on DPposs, which therefore moves to the Spec of D/Pe0. But the latter also cannot license dative Case; so DPposs must move further up, to get nominative Case in Spec,IP. The “prepositional” D0 obligatorily adjoins to BE in English, and is spelt out as HAVE.

The idea that have is be with a preposition incorporated into it is adopted from Freeze (1992).

In the light of the above analysis we can make sense of the alternation between structures ( within English) illustrated in (14–18). We repeat (14) below:

In the (a) sentence, D/Pe0 has not adjoined to BE; so there is no have in the place of be. And the dative Case associated with D/Pe0 is realized as the preposition to. The Case relations of Old English were translated as preposition relations in the transition to Early Middle English, as Lumsden (1987) notes. And since, during the same transition, English ceased to be a pro-drop language (as Jespersen 1909–1949 notes), the subject position is filled by the pleonastic element there.

The (b) sentence represents the ‘normal’ possessive construction in English. The D/Pe0 has adjoined to BE, and so we get the verb have. The possessor DP, since it can no longer get its Case from D/Pe0, moves to Spec,IP and gets nominative Case. (The optional ‘to it’ can perhaps be explained as follows: D/Pe0, when adjoining to BE, leaves a copy which is optionally realized as to ; the Possessor DP subsequently moves to the subject position, leaving a pronominal copy it. The movement from a Case position to another Case position (we must assume) is allowed in this case, because the moved DP continues to be in the Spec of the same element, namely D/Pe0.)

We shall adopt a slightly different structure for the possessive construction than the one Kayne (1993) proposes. Assuming Hale and Keyser’s proposal that theta roles are to be defined as positions in structural configurations, let us ask the question: What is the structure corresponding to the Possessor theta role? Obviously, functional elements like AGR0 and D0 cannot be part of a configuration that determines a theta role; therefore in (23), DPposs cannot have as its base position the Spec of AGR0. The AGR projection, if it must be postulated, must be higher. We shall also assume, differently from (23), that D0 and P0 are heads of separate projections; and that a D0 may not be generated at all if the DP is indefinite.

As regards P0, its function in Kayne’s analysis is to license, or “assign”, the dative Case of the possessor DP. But if we adopt the position (of distributed morphology) that Case is not “assigned”, but DPs simply move into the Spec of a Case Phrase (KP) headed by a Case morpheme, we need a different execution here. Thus, when a P appears to “assign” Case to its object DP, what happens is that P selects, and is “paired with,” a KP into whose Spec position the object DP moves. Since there is no preposition on the Malayalam (or indeed, Hungarian) possessor DP, we need not postulate a P0 at all; all we need is a K0—or more specifically, a K0dat—heading a KP. But since this KP also is only a functional category, it cannot be part of the LRS representation of the Possessor theta role, and so must be generated higher.

So then, what does form part of the LRS representation of the Possessor theta role? The notion of possession implies two entities that stand in a certain relation. Let us represent this relation as P, which take two entity-denoting expressions in its Spec and complement position. (This element is not a member of the lexical category P, which in English at least, we believe, is a development of the loss of Case in Early Middle English; moreover P, being a functional category, cannot be part of a theta configuration. It is semantically simply a ‘R(elation).’ But for want of such a categorial notation, we call it P advisedly.) The copula BE may or may not be an essential part of the configuration in question. For concreteness, let us assume that it is. The theta configuration for the Possessor we assume is the following:

The space indicated by ‘…’ implies a claim that a theta configuration need not be strictly local: in the particular case (25), functional heads like K0, AGR0 and D0 may intervene between BE and the PP. (But if BE is not an essential part of the possessive configuration, we may dispense with both BE and ‘…’ in (25); nothing in our analysis is affected by this decision.)

We suggest that this is also the configuration for the Experiencer theta role, a claim which would be in line with the observation that the theta roles available to Language are quite few in number owing to their being limited by the number of distinctive configurations available (Hale & Keyser 1993). Therefore, (25) may be revised as (26):

Possibly, (26) is also the configuration for Locatives. A figure-ground configuration may be the underlying notion here; the Possessor, or the Experiencer, or the Location being the ground, and the possessed thing, or the experienced thing, or the located thing being the figure.2

The configuration (25) (or (26)) always occurs in a context of functional categories in the structures we are interested in. In order to linearize these functional categories, let us look at the Hungarian facts again. The Hungarian D0, when definite, is optionally overt; and when it is overt, what we find is that DP poss is nominative when it occurs to the right of D0, and dative when it occurs to the left of D0. This argues that AGR0 (licensing nominative Case) is to the right of D0, and Pdat—Kdat in our analysis—is to the left of D0. The inter se order that we must postulate for these functional categories, then, is: ‘K0 – D0 – AGR0’.

If we generate these functional categories in the space indicated by ‘…’ in (25), the full structure we are dealing with may be something like (27):

But here, the D0 (as we said) may not be generated if the possessed entity is indefinite; as it is in all the cases that we shall speak of.3 The AGR0 also may be only optionally generated. If D0 and AGR0 are absent, what we get is (28):

Consider the situation where DP poss has moved into the Spec of Kdat:

In English, Kdat adjoins to BE and we get have; and DPposs then moves to the Spec of a higher functional projection to get nominative Case.

Kayne’s claim (as we just said) is that in English, Kdat (or what he called D/Pe0 in his analysis) adjoins to BE and we get have. We suggest that something else can happen in (29): when the complement NP consists of only an N, it may adjoin to Kdat (‘picking up’ the intervening head P0 on its way) and be realized as an adjective.

This hypothesis explains a fact noted in Kayne (1993), namely that have cannot take an adjectival complement:

Note that if be can take an adjective, and if have is derived from be, it is prima facie surprising that have cannot take an adjective as its complement. But we now see why this is so: it is the same Kdat that either incorporates into BE to yield have, or is adjoined to by a noun to give us the adjective.

Our hypothesis also solves a ‘technical’ problem that Hale and Keyser encounter with adjectives (see Hale and Keyser 2002: 25–27, 205ff.). Consider the following:

Here, the sky is an argument of clear, so we would want to generate it in a projection of the adjective. But if we merge the DP and the A, the mechanism of Merge will give us only a Head-Complement relation, not a Spec-Head relation. The authors’ solution is an LRS representation for A, in which A’s argument is always realized in the Spec of another head that takes A as a complement. Our analysis of adjectives obviates this problem: the subject DP of a small clause with an adjectival predicate is never merged with A; it is merged in the Spec of an abstract P0 which takes an N as complement.

But the biggest result of our hypothesis about adjectives is that we are now in a position to explain the three-way alternation that languages exhibit in expressing the notion of experiencing something or the notion of possession. We repeat (9) here:

If Kdat remains independent, the Experiencer DP (or the Possessor DP, as the case may be) can move into the Spec of this KP and get dative Case; this gives us (a). But if Kdat is absorbed into BE as in (c), or into N as in (b), the Experiencer (or Possessor) DP must move up into Spec,IP and get a nominative Case there.4

What needs to be further noted is that this type of “absorption” of Case into other categories takes place in a widespread manner only in a language in which the Case system has become destabilized as a result of language change. This happened in English, but not in Dravidian. Which explains why English has adjectives and Dravidian has no adjectives (or few adjectives); also, why English has a verb like ‘have’ and Dravidian does not; and also, why the dative construction is such a prominent part of Dravidian syntax whereas this construction has only a minimal presence in English.

We conclude this paper by drawing attention again to an ‘adjective-making’ strategy that obtains in Kannada, because it supports our proposal about adjectives in a particularly transparent fashion. In Kannada the normal way to say ‘Rama is tall’ is:

Here, udda-kke ‘height-DAT’, which is functionally an adjective, is transparently N+K. The contrasting nominative pattern:

is used in Kannada only in special contexts like ‘Rama has the height to do something (e.g. join the army).’

* A preliminary version of this paper was presented at the conference on ‘Argument Structure’ at the University of Delhi, January 2003. I wish to thank the audience of the conference for insightful comments. A special word of thanks to Halldór Sigurdsson for sending me the data noted in Fn. 4. Let me also acknowledge my indebtedness to R. Amritavalli for the central idea of this paper, namely that adjectives are derived by the incorporation of nouns into prepositions, see Amritavalli (this volume).

1. Actually, there is no consensus on this question. Thus Zvelebil (1990: 27) writes: “Among those who tend to deny or do deny the existence of adjectives as a separate ‘part-of-speech’, the most prominent are Jules Bloch and M.S. Andronov. Master, Burrow and Zvelebil, on the other hand, accept adjectives as a separate word-class.” Bhat (1994) advances several arguments in support of his contention that Dravidian has a class of adjectives; but see Amritavalli and Jayaseelan (2003) for the observation that most of Bhat’s arguments are functional and not syntactic.

2. As regards the two phrases related by P in (26), it may be the case that the more referential (definite) phrase goes into the Spec position, and the less referential into the predicative (complement) position. This means that, depending on their relative referentiality, the positions of the two phrases may be reversed. In the Hale-Keyser derivation of the denominal verb shelve, the N shelf is non-referential and is therefore in the complement position, from where it is free to incorporate into the head of the phrase.

3. For a way of dealing with a sentence like John has your article (with him), where the possessed entity is a DP, see Kayne (1993, Fn. 14).

4. Halldór Sigurdsson (p.c.) points out that there are a few cases in Icelandic where a dative construction has apparently an adjective as predicate, cf. (i); he also gives a German example, cf. (ii), and says that there are similar examples in Russian.

Such examples, although few in number (the construction is non-‘productive,’ according to Sigurdsson), are nevertheless a problem for our analysis: how can the Case element, which has become part of the adjective, also show up on the Experiencer DP? One way to solve the problem is to suggest that kalt ‘cold’ in this context is actually a Noun; but we have not investigated how viable such a suggestion is. Another possibility is that K0dat, when it moves along with the Experiencer DP to a Topic-like position, leaves behind a copy which (exceptionally) is amenable for the N to adjoin to. (This solution would be in the spirit of our earlier suggestion about the optional ‘to it’ in sentences like (14b).)

Amritavalli, R. & Jayaseelan, K.A. 2003. The genesis of syntactic categories and parametric variation. Paper presented at the 4th Asian GLOW Colloquium at Seoul, August 2003.

Anandan, K.N. 1985. Predicate Nominals in English and Malayalam. M.Litt. Dissertation, Central Institute of English & Foreign Languages, Hyderabad.

Bhat, D.N.S. 1994. The Adjectival Category: Criteria for differentiation and identification. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Hale, K. & Keyser, S.J. 1993. On argument structure and the lexical expression of syntactic relations. In The View from Building 20: Essays in linguistics in honor of Sylvain Bromberger, K. Hale & S.J. Keyser (eds), Cambridge MA: The MIT Press.

Hale, K. & Keyser, S.J. 2002. Prolegomenon to a Theory of Argument Structure. Cambridge MA: The MIT Press.

Freeze, R. 1992. Existentials and other locatives. Language 68: 553–595.

Jayaseelan, K.A. To appear. The possessor/experiencer dative in Malayalam. In Non-nominative Subjects, P. Bhaskararao & K.V. Subbarao (eds). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Jespersen, O. 1909–1949. A Modern English Grammar on Historical Principles, Vols. I–VII. London: Allen & Unwin.

Kayne, R. 1993. Toward a modular theory of auxiliary selection. Reprinted in Parameters and Universals, R. Kayne, 107–130, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

Lumsden, J.S. 1987. Syntactic Features: Parametric variation in the history of English. PhD Dissertation, MIT.

Szabolcsi, A. 1983. The possessor that ran away from home. The Linguistic Review 3: 89–102.

Zvelebil, K.V. 1990. Dravidian Linguistics: An introduction. Pondicherry: Pondicherry Institute of Linguistics and Culture.