R. Amritavalli

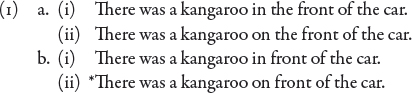

Svenonius (2006b) distinguishes the “axial part” and “part” readings of a body:*

The AxPart reading is seen in (1bi), the part reading in (1bii) and (1aii). Svenonius quotes Jackendoff (1996) on the notion of an axial part:

“The “axial parts” of an object—its top, bottom, front, back, sides, and ends—behave grammatically like parts of the object, but, unlike standard parts such as a handle or a leg, they have no distinctive shape. Rather, they are regions of the object (or its boundary) determined by their relation to the object’s axes. The up-down axis determines top and bottom, the front-back axis determines front and back, and a complex set of criteria distinguishing horizontal axes determines sides and ends.” (Jackendoff 1996:14)

Svenonius argues that “AxPart is a category like aspect or modality, realized in many languages” (Svenonius 2006b:50). He refers to the ‘part’ sense of a word like front as its N use, and to the region or spatial sense as its AxPart use:

In English, Svenonius points out, the AxPart

i. cannot take plural morphology

• There were kangaroos in the fronts of the cars

• *There were kangaroos in fronts of the cars

ii. cannot take adjectival modification

• There was a kangaroo in the smashed-up front of the car

• *There was a kangaroo in smashed-up front of the car

iii. and may combine with measure phrases

• *There was a kangaroo sixty feet in the front of the car

• There was a kangaroo sixty feet in front of the car

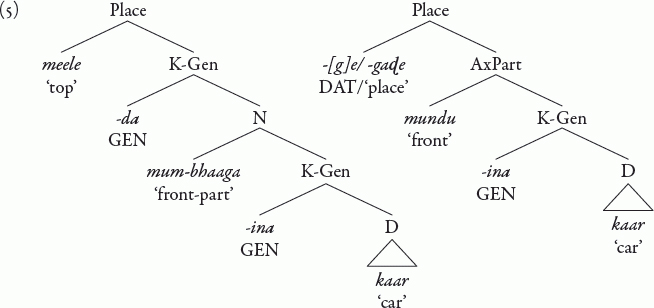

“The semantic function of AxPart is to identify a region (a set of points in space, cf. Nam 1995, Kracht 2002) based on the Ground element (the complement DP; see Svenonius in press for discussion of the Ground interpretation of P complements) … The semantic contribution of Place is to specify how space is projected from a region; I will assume a modelling of space in terms of vectors along the lines proposed by Zwarts (1997), Zwarts and Winter (2000). Vectors are one-dimensional objects with direction and length which define points in a space when they are drawn from a region.” (Svenonius 2006b:52, references updated)

“PlaceP is relational; I assume a syntactico-semantic component p, which introduces a Figure and specifies a spatial relation to a Ground (Svenonius 2003). … The content of p may specify such relations as containment (in), contact (on), support (Dutch an), etc.” (Svenonius 2006a)

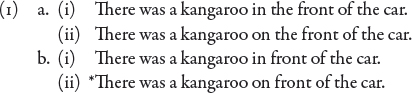

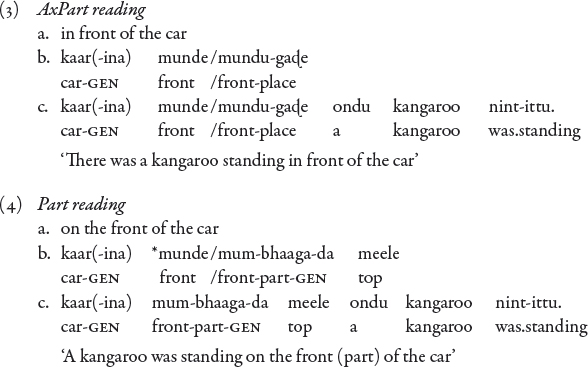

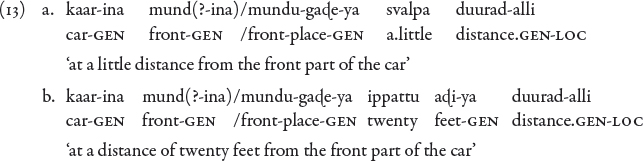

Kannada encodes the two readings AxPart and Part in the choice of the noun that seems to form a compound with the (putative) postposition. The bare “postposition” (itself perhaps just a noun, or a noun in the process of “bleaching” into a P) appears to convey only the AxPart reading. Cf.1

The noun compound formed by munde ‘front’ with kaɖe ‘place’ gives us the AxPart reading (as does the bare munde); the compound formed by munde with bhaaga ‘part’ gives us the part reading.2 Notice that the AxPart munde/mundu-gaɖe manifests no overt postposition or noun corresponding to in in English. We shall later suggest that munde incorporates a phonologically reduced form of the dative case -ge, which functions as the Place head. We suggest also that kade, which we choose to gloss as ‘place,’ is a Place head.3

Svenonius’ observations that the AxPart or ‘region’ reading

• does not permit adjectival modification

• allows for MeasureP modification, unlike the part reading

hold good for Kannada. (There is a caveat about measure phrase modification, see below.)

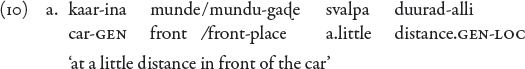

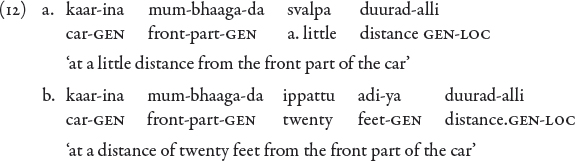

In (9) the measure phrase occurs preceding the AxPart munde. In the case of the AxPart mundu-gaɖe, it appears that the head noun kaɖe does not allow for a coherent reading with measure phrase modification preceding it (cf. *twenty feet place in English). However, a postposed appositive phrase strategy allows a MeasureP to occur with munde as well as mundu-gaɖe in (10).

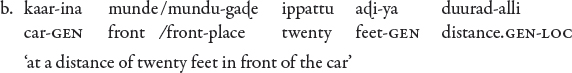

This postposed appositive phrase strategy is not available for mum-bhaaga, as seen in (11).

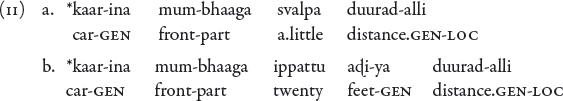

In (12), mum-bhaaga is marked genitive, and occurs as the “possessor” of a MeasureP. But (12) indicates not a distance in front of the car, but a measurement from the front part of the car.

The genitive-marking strategy of (12) is marginally possible with bare munde; and surprisingly, quite possible with mundu-gaɖe. But in such cases, a Part reading seems to be forced for these elements which are otherwise understood as AxParts:

It seems that munde or mundu-gaɖe, when they are marked genitive, cannot be interpreted as AxParts. Note that there is no general prohibition on munde taking a genitive marker: mund-ina kaaryakrama, ‘the next programme.’ We shall return to the latter type of expression when we discuss NextParts.

Although the AxParts munde and mundu-gaɖe do not allow genitive case, they do allow for dative, locative and ablative (from) case-modification. In the examples below, the dative and ablative case markers delineate a Path with respect to Place, while the locative case marker specifies a Location. (The locative case marker is homophonous with an adverbial free morpheme alli meaning ‘there, at that place.’) We may thus take the dative and ablative cases to “represent different values of a functional projection Path, dominating Place,” following a suggestion of Svenonius (p.c.); and take Location as the corresponding functional projection for the locative case (17). We note that when the AxPart is thus embedded under Path/Location, a vestigial genitive case may then occur as a frozen morpheme “governed by” the ablative or locative (to use terminology from traditional grammar).

The reader may notice in (17)/(18) the claim that the dative-marked form of munde, namely munda-kke, incorporates a null dative case (the head of PlaceP) inside the overt dative case (the head of PathP). We shall now consider the evidence for this claim of a null dative case in munde.

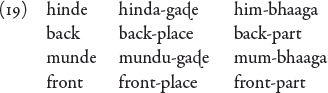

We have so far considered the horizontal axis from front to back, with munde ‘front’ as its exemplar. Hinde ‘back’ is essentially similar to munde: it is an AxPart in its bare form, and it forms an AxPart and a Part by compounding with the nouns kaɖe and bhaaga respectively (19). (We include the munde forms in (19), for completeness.)

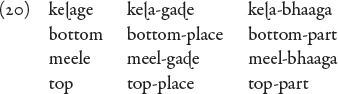

The vertical up-down axis is also like the horizontal front-back axis. We give below in (20) the bare form AxParts and the -kaɖe/-bhaaga compounds that are the Parts and AxParts for this axis:

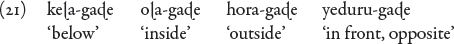

Consider now the form keɭage ‘bottom’ in (20). It is morphologically complex, and it seems to incorporate the dative case. To see this, compare keɭa-ge ‘bottom’ with the companion forms oɭa-ge ‘inside,’ hora-ge ‘outside’ and yeduri-ge ‘in front of, opposite.’ All these forms attest an ending, -ge, which is synonymous with the dative case. This -ge disappears when these words are compounded with -kaɖe or -bhaaga:

The morphemes keɭa-, oɭa- and hora- no longer occur as free morphemes in Kannada. Nor do other case-endings attach directly to these morphemes, when (e.g.) Place is embedded under Path. (In such a case, the case-endings that head the Path projection attach to the ge-fused forms: e.g. keɭa-g-inda ‘below-ge-from’, ‘from below’.) But the morpheme yedur- is attested in a ge-less form. It appears in the locative, with the latter attached to a frozen genitive case: yedur-in-alli ‘opposite-GEN-LOC.’ This shows that -ge in yeduri-ge is indeed a separable morpheme, specifically, dative case. Thus the -ge in the other words in this group is also very likely an incorporated dative case.

These dative-marked words are AxParts. They behave like munde, hinde and meele in isolation, and they form AxParts when compounded with kaɖe, Parts when compounded with bhaaga:

In short, when we consider AxParts in Kannada, we find

i. elements that are followed by no overt case or postposition at all: munde/hinde/meele ‘front/behind/top,’ and

ii. elements that seem to have fused with a dative case: keɭage/yedurige/… ‘under/front/…’

The idea we shall pursue is that the dative case has had a role in the evolution of nouns into AxParts such as keɭage, oɭage, etc. We therefore suggest that there is a submerged dative marker in superficially unmarked AxParts such as munde as well. This is supported by the interchangeability of the bare with the dative-marked form in expressions such as {mund-akke kuutuko/munde kuutuko} ‘Sit to the front, sit in front.’ It is also suggested by the strong form -kke of the dative case, rather than the expected form -ge, on munde, hinde and meele: we have mund-akke, hind-akke, meel-akke, and not *munde-ge, hinde-ge or meele-ge. The explanation for this strong form of the dative cannot lie purely in the sound pattern of the language, which permits the similar-sounding noun handi ‘pig’ to be dative marked by -ge: handi-ge, ‘to the pig.’

Rather, we find that the strong form -kke of the dative occurs on the AxParts which (on our analysis) already incorporate a dative marker, when these AxPart complements to Place are further embedded under a Path with a dative case head (as postulated in (17) above): keɭa-ge ‘below’ ∼ keɭakke ‘to a lower place’; oɭa-ge ‘inside’ ∼ oɭakke, ‘to the inside’; hora-ge ‘outside,’ ∼ hora-kke ‘to the outside.’

We suggest that a “bleached” noun like munde, now an AxPart, has become such by virtue of its incorporation of an abstract dative case. Notice that this explains our earlier observation that the AxPart cannot take genitive case. More generally, we can say that what licenses an AxPart reading for a noun is the incorporation of either a Place head like the noun kaɖe, which indicates a region, or the dative case marker: hence mundu-gaɖe, munde (=mund+ge). In the next section we shall reinforce these points by looking at the AxPart that denotes the horizontal axis from side to side.

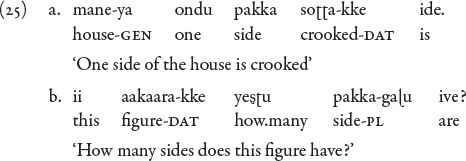

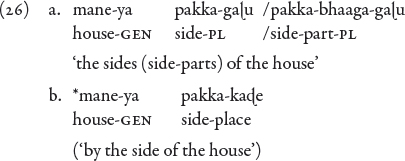

The Kannada word for ‘side’ is pakka. The bare noun pakka ‘side’ has the ‘part of an object’ meaning (25a), and it pluralizes (25b). Let us call this pakka1.

pakka1 also forms a -bhaaga or Part compound (26a); but it does not form a -kade or AxPart compound (26b):

The inability of pakka to form a compound with kaɖe may be because pakka itself can also indicate a region. I.e., it can have the same meaning as kaɖe. Thus in (27a), pakka has a non-relational abstract meaning ‘these parts,’ and in (27b) a directional reading ‘towards that side.’ On this reading, pakka cannot pluralize:

Pakka in (27)—let us call it pakka2—is like the non-compounded kaɖe in some of our earlier examples, in that it indicates simply a region. Indeed, pakka and kaɖe are intersubstitutable in examples (27a)–(27b).

All this suggests that pakka2 can (like kaɖe) be the head of a Place phrase that takes an AxPart as its complement; and indeed, in my dialect of Tamil (a sister Dravidian language to Kannada) AxParts are formed with compounds with -pakka, rather than -kaɖe compounds: mum-pakkum ‘front-side’ ‘in front,’ pin-pakkum ‘back-side’ ‘at the back.’

In Kannada, however, pakka2, ‘side, region,’ does not occur as a Place head (this function being fulfilled by kaɖe). Nor can pakka1, ‘side,’ compound with either kaɖe or with pakka itself: *pakka-kaɖe ‘side-place,’ *pakka-pakka ‘side-side.’ What then is the AxPart for the side-to-side axis?

We have said that an AxPart reading for a noun may be licensed in one of two ways: the incorporation of a Place head like the noun kaɖe, which indicates a region; or by the incorporation of the dative case marker, which may or may not be overt. Consider now the dative-marked use of pakka.

The dative case (and in the English translation, the preposition to) result in a reading where the noun pakka ‘side’ acquires the reading of a figure that relates to some unspecified ground. (Dative-marked pakka is also open to metaphorical construal, parallel to the English example “We agreed to put our differences aside.”)

We may add an example where dative-marked pakka is an AxPart that picks out the figure relative to a ground that is specified:

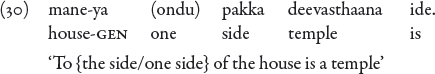

Given a clear AxPart context like (29), there is the option of letting the dative case remain covert (as in (30)). It is possible, therefore, that there is a covert dative case in our examples (27) above as well. This would suggest that pakka2, ‘the region at the side,’ differs consistently from pakka1, ‘a side,’ in being marked dative.

But now consider (31)/(32), where an AxPart reading for pakka emerges with genitive case embedded under a locative case (or ablative case, given an appropriate context). The occurrence of the latter cases suggests that what we have in (31)/(32) is a Path/Location projection dominating Place.

We had noted in connection with example (13) that AxParts seem to lose their ability to take genitive case. But in (31) the “region” reading for pakka emerges with genitive case on it.

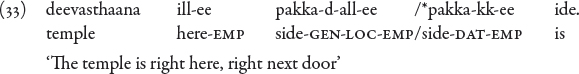

There is a subtle semantic difference between (29) and (31): there is in (31) a sense of immediate adjacency that is absent in (29). This is a difference that comes through in the English translations as well: so one can say ‘right {by my side/beside me},’ ‘right/just at the side of,’ corresponding to the genitive-marked pakka examples in Kannada, but not *‘right/just to the side of,’ corresponding to the dative-marked pakka in Kannada. That is, (31) seems to incorporate a reference to the boundary of the house, in a way that (29) does not.

This presence or absence of immediate adjacency is also what makes the idiomatic expression (33) below licit with genitive pakka, but illicit with dative pakka. While the genitive conveys a sense of nearness, the ungrammatical dative gives rise to an odd reading that the temple is tucked away to one side, out of sight:

We thus identify a reading ‘Next to’ or NextPart that is intermediate between a Part and an AxPart reading, which appears to incorporate a reference to the boundary of an object. (This sense of ‘contact with the boundary of an object’ also emerged earlier in our examples (12) and (13) where genitive case occurred with a MeasureP.) On this reading of adjacency, genitive case is possible on the AxParts discussed earlier as well. Notice that genitive case allows for recursion in the noun phrase: we return to this point.

The difference between the NextPart and the AxPart readings can be seen clearly with the AxPart meele ‘top’. A genitive case can appear on this AxPart when we speak of ‘the house above (ours)’ (meele-gaɖ e-ya mane ‘top-place-GEN-house’), or of ‘the overhead tank’ (meel-ina tankku ‘top-GEN tank’), both of which are in contact with the roof of the house. But to speak of the plane that flies overhead, one cannot say *meel-ina plane ‘top-GEN plane.’ A relative clause structure meele hoog-uva plane ‘top go-REL aeroplane’ ‘the plane going overhead’ must occur instead.

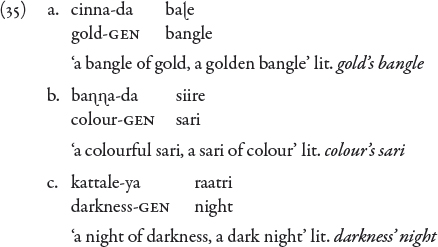

The status of the genitive marker in such examples is of some interest. Our suggestion (cf. (31)) is that it is a Place head, a counterpart to the dative case illustrated earlier. We must note here the possibly relevant fact that the genitive and dative cases pattern together elsewhere: there is a ‘dative of possession’ in Kannada, with dative case appearing on the possessor. Again, a function for the genitive marker other than signaling possession is seen in (35), where the genitive appears merely to link a noun in an attributive or modifier function to a head noun:

As the English translations suggest, the of -genitive in English has a comparable range of interpretation, although the English affixal genitive does not allow these readings.

Kannada has only the affixal genitive. Indeed, Kannada does not allow any post-N structures at all (such as PPs). This seems to characterize Dravidian more generally; thus Jayaseelan (1988:95) notes for Malayalam the following facts that are true for Kannada as well: “… a noun in Malayalam may not … take an NP complement. … A Malayalam noun may not even take a PP complement …” As Jayaseelan illustrates, structures corresponding to the king’s love (for the minister), the king’s criticism (of the poem), or the wealth’s squandering (by the king) are ungrammatical in Malayalam if the parenthesized complements are included.

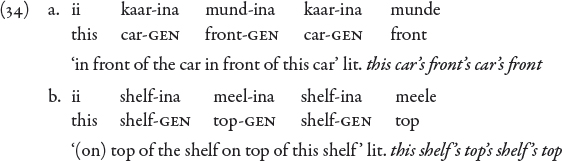

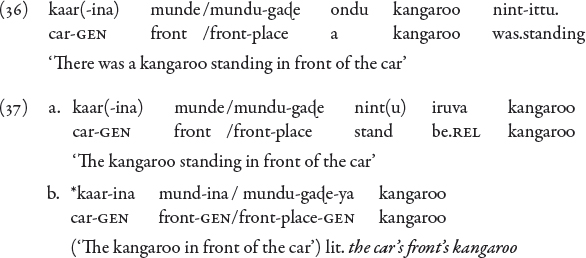

What the Dravidian noun phrase does allow are (i) pre-nominal relative clause structures, and (ii) recursive genitive structures. This brings us to the second interesting fact about the genitive in structures like (31). Although not semantically a possessive marker, it makes possible the recursion shown in (34). This recursion is not possible when the AxPart is marked dative, or is compounded with a noun functioning as a Place head. In such cases iteration is possible only with the help of a relative clause, i.e. option (i) above.

To illustrate, let us go back to our example (3) (=(36)).

To conclude, nouns meaning ‘place, region’ and ‘part’ are recruited in Kannada to form AxPart and Part readings. AxParts may also be formed out of nouns by the fusion of a dative marker or a genitive marker with the N. The genitive marker gives a sense of immediate adjacency that we designate as a NextPart reading.

The dative case may be overt, or covert in AxParts like munde, where it serves to introduce the Place element. We must note that dative case also serves to introduce time in Kannada: eɳʈu gaɳʈe-ge ‘eight hours-DAT,’ ‘at eight o’clock.’ Again, a historically fused dative case is visible in such adverbial words as beɭa-gge ‘in the morning,’ where the morpheme beɭa- has a meaning related to ‘light’ (beɭa-ku, ‘a lamp’).

The dative case serves to ‘bleach’ a noun into a postposition. A noun bleached in this way by dative-marking loses the ability to take genitive case. Thus one difference between nouns and postpositions in Kannada could be the inability of the postpositional “noun” munde, meele, etc. to build a recursive noun phrase.

The sometimes parallel functions of the dative and genitive cases in Kannada are worthy of investigation. We had earlier suggested (Amritavalli and Jayaseelan 2004) that dative case on a noun can turn it into an adjective, noting the existence of pairs like udda ‘height,’ udda-kke ‘tall,’ as also the consequent change from an Experiencer Dative construction to a Nominative Subject construction (pp. 29–30, exx. 21–22) for the derived adjectival predicates. In (25a) above we have another such example: the noun soʈʈa, which translates into English as the adjective ‘crooked,’ needs to be dative-marked to occur as a predicate with the verb ‘be’: soʈʈa-kke ide ‘is crooked.’ Our examples (35) show that the genitive serves to allow a noun to occur attributively, much like the element of in English.

Thus the dative and the genitive cases apparently effect the categorial change of a noun to an adjective or attributive element. We have seen that the dative and genitive cases also serve to induce a ‘region’ or AxPart reading for certain nominal words denoting spatial axes, with genitive case consistently inducing a reading of immediate adjacency.

* My thanks to Peter Svenonius for his careful comments on an earlier version of this paper. http://www.ub.uit.no/baser/nordlyd/

1. kaɖe/gaɖe translates into English as ‘side’ (as in oɭa-gaɖe ‘inside,’), or as ‘place’ (ella kaɖe, ‘everywhere, every place’; ondu kaɖe, ‘one place, a/some place’). It might also translate as ‘direction, way’ (yaava kaɖe, ‘in which direction’), or ‘end’: kaɖe-ge ‘in the end.’

2. The change in /kaɖe/ to /gaɖe,/ in mundu-gaɖe, and the truncation of munde and concomitant assimilation of /n/ to /m/ in mum-bhaaga, suggests that these words are compounds (of different degrees of cohesion). Kannada does not have a general rule of intervocalic voicing of consonants, either within a word or across word boundaries. Thus the voicing of /k/ in mundu-gaɖe contrasts with the absence of voicing in ii kaɖe ‘this place, here,’ aa kaɖe ‘that place, there,’ and similar examples in n. 1 above. This suggests that mundu-gaɖe, oɭa-gaɖe are N-N compounds, while ii kaɖe, aa kaɖe, etc. are D-plus-N combinations.

3. AxParts in French can have spatial meanings without a preceding P[lace] element (Roy 2006, reported in Svenonius 2006b). Svenonius suggests that French has a null Place head.

References

Amritavalli, R. and K.A. Jayaseelan. 2004. The genesis of syntactic categories and parametric variation. In Generative Grammar in a Broader Perspective: Proceedings of the 4th GLOW in Asia 2003, edited by Hang-Jin Yoon, pp. 19–41. Hankook, Seoul.

Jackendoff, Ray. 1996. The architecture of the linguistic-spatial interface. In Language and Space, edited by Paul Bloom, Mary A. Peterson, Lynn Nadel, and Merrill F. Garrett, pp. 1–30. MIT Press, Cambridge, Ma.

Jayaseelan, K.A. 1988. Complex predicates and theta-theory. In Syntax and Semantics volume 21: Thematic Relations, edited by Wendy Wilkins, pp. 91–111. Academic Press, San Diego.

Kracht, Marcus. 2002. On the semantics of locatives. Linguistics and Philosophy 25: 157–232.

Nam, Seungho. 1995. The Semantics of Locative PPs in English. Ph.D. thesis, UCLA.

Roy, Isabelle. 2006. Body part nouns in expressions of location in French. In Tromsø Working Papers in Language & Linguistics: Nordlyd 33.1, Special Issue on Adpositions, edited by Peter Svenonius and Marina Pantcheva, pp. 98–119. University of Tromsø, Tromsø. Available at http://www.ub.uit.no/baser/nordlyd/.

Svenonius, Peter. 2003. Limits on P: filling in holes vs. falling in holes. In Tromsø Working Papers on Language and Linguistics: Nordlyd 31.2, Proceedings of the 19th Scandinavian Conference of Linguistics, edited by Anne Dahl, Kristine Bentzen, and Peter Svenonius, pp. 431–445. University of Tromsø, Tromsø. Available at www.ub.uit.no/baser/nordlyd/.

Svenonius, Peter. 2006a. Axial parts. Handout #3 for EALing course in Paris, September.

Svenonius, Peter. 2006b. The emergence of axial parts. In Tromsø Working Papers on Language and Linguistics: Nordlyd 33.1, special issue on Adpositions, edited by Peter Svenonius, pp. 1–22. University of Tromsø, Tromsø.

Svenonius, Peter. in press. Adpositions, particles, and the arguments they introduce. In Argument Structure, edited by Eric Reuland, Tanmoy Bhattacharya, and Giorgos Spathas, pp. 71–110. John Benjamins, Amsterdam. Preprint available at http://ling.auf.net/lingBuzz/000042.

Zwarts, Joost. 1997. Vectors as relative positions: A compositional semantics of modified PPs. Journal of Semantics 14: 57–86.

Zwarts, Joost and Yoad Winter. 2000. Vector space semantics: A model-theoretic analysis of locative prepositions. Journal of Logic, Language, and Information 9: 169–211.