K. A. Jayaseelan

The idea that some lexical categories—what are traditionally called “parts of speech”– are not primitives of Grammar but are generated by category-making operations in the syntax has been put forward in recent linguistics, with variations.* Marantz (1997, forthcoming) proposed that lexical roots have no category; a category-less root becomes Noun or Verb by adjoining to “little” n or “little” v. Marantz in effect separates encyclopedic meaning from “noun-ness” and “verb-ness;” in a sense, the primitiveness of Noun and Verb still survives in this approach (as functional heads). A more radical suggestion is made in Pesetsky (2007, 2012). Pesetsky, studying the case and agreement systems in Russian, suggests that a category-less root becomes a Noun by being suffixed with Genitive, or a Verb by being suffixed with Accusative. He also suggests that Determiner is made by Nominative case and Preposition by Oblique case. This notion of case-incorporation creating a lexical category is central to the present paper (although we won’t generate the category of Noun in this fashion).

A still further variation in the current ferment of ideas on this topic is represented by Kayne (2008). Kayne claims that Noun is the only category capable of denotation; as such, it is the only primitive lexical category, and the only “open class” category. The two other “open classes” of traditional grammar, Verb and Adjective, are derived from Noun by functional affixation.

Amritavalli & Jayaseelan (2003) claimed that the category of Adjective is generated when a nominal root incorporates into a case-head. The main task of this paper is to extend this analysis to Verb: Adjective and Verb, I now claim, arise when a nominal element N0 incorporates a case, specifically Dative case.

The paper is organized as follows. In § 1, I motivate for Dravidian the Case Hierarchy ‘Dative > Accusative > Genitive’, using the evidence of complex case morphology in Malayalam. In § 2, I propose an algorithm that generates the three cases in that order. In § 3, I first summarize the arguments of Amritavalli & Jayaseelan (2003) for the claim that Adjective is a derived category; then I demonstrate that the verb in Malayalam is a derived category that is generated by the incorporation of case. In § 4, I propose a theory about how the case-marking patterns of sentences with intransitive, transitive and ditransitive verbs are generated. In § 5, I resolve some prima facie problems for the case-incorporation account of the Malayalam verb; I also very briefly consider how this analysis might apply to English verbs. § 6 (‘Conclusion’) summarizes the main claims of the paper.

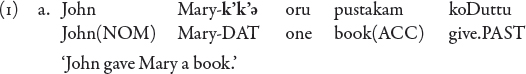

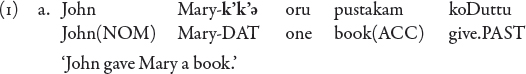

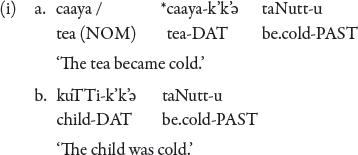

The Dative case in Malayalam is illustrated in (1):

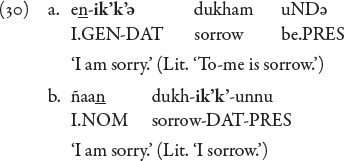

The -k’k’ə suffix can also be realized as -kkə, or simply -ə, the choice between the three forms being determined (seemingly) by phonological factors:

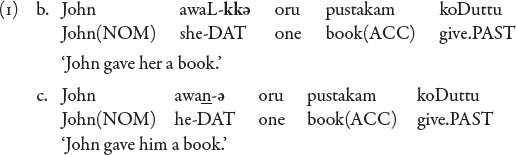

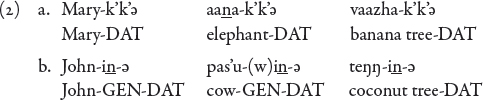

The Dravidian languages are case-stacking languages, a fact which is not obvious on the surface because of an overwriting rule: a later-suffixed case ‘overwrites’ (makes silent) an earlier-suffixed case. (This type of system has been recently made prominent by Pesetsky’s (2007/2012) study of Russian.) The overwriting is not “perfect,” however, because sometimes an earlier case “shows through.” Typically, it is a Genitive that shows through in this fashion—leading traditional grammarians of Dravidian to in fact say that all Dravidian cases are suffixed to a Genitive stem (Krishnamurti 2003:218ff.).1 The surfacing of the Genitive is again determined by phonological factors that we shall not go into here. Note how the forms in (2a) contrast with those in (2b) as regards the appearance of the Genitive:2

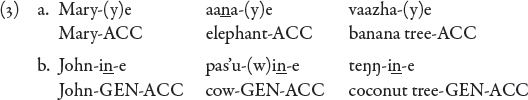

The Genitive surfaces also with the Accusative case in Malayalam, again with the same stems as with the Dative case; thus the nouns in (3a) don’t let the Genitive surface in the standard language, but the ones in (3b) do:3

Typological studies of case have determined a Case Hierarchy that is universal; it makes implicational predictions: e.g., if a certain language instantiates a particular case on the Hierarchy, it will also have all the cases that are lower on the Hierarchy. Building on the idea of the Case Hierarchy, a challenging claim has been made in the framework of Nanosyntax that all instances of case (with the possible exception of Nominative) are in fact ‘layers’ of case underlyingly—more explicitly, that when a case is generated on a nominal expression, all the cases lower on the Case Hierarchy are also generated on it (see Caha 2007, 2009; Starke 2005). The case-stacking in Dravidian—the phenomenon of ‘another’ case “showing through”—can be understood in terms of these ideas: we can say that whenever a Dative or Accusative is generated, a Genitive is also generated—which is sometimes silent and sometimes surfaces.

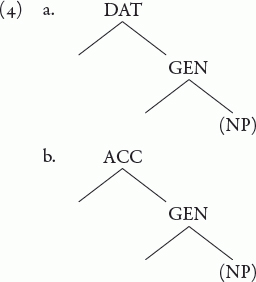

The data in (2b) and (3b) enable us to determine two sequences of the hierarchical order of cases at least as far as Dravidian is concerned:

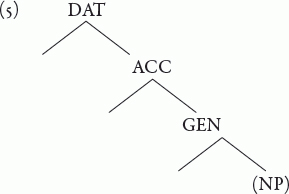

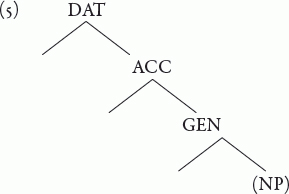

That is, since the Genitive is closer to the nominal stem than Dative or Accusative, it is generated lower than either of these. (And we may assume that the NP picks up the case-suffixes by moving to the left of them cyclically.) A remaining question is the inter se order of Dative and Accusative (assuming that these two cases also are hierarchically ordered). In Dravidian, Dative and Accusative never co-occur on the same nominal form on the surface; so “containment relations” of case morphology will not give us a straightforward cue to resolve this question. But there are languages in which Dative is morphologically based on Accusative (Caha 2010:206); and in the Universal Hierarchy proposed by Blake (1994) and Caha (2007, 2009), Dative is above Accusative. So we shall adopt the following hierarchy:4

But how is the structure (5) generated? First we ask a more specific question: how does the Dative case come to be, on a nominal expression?

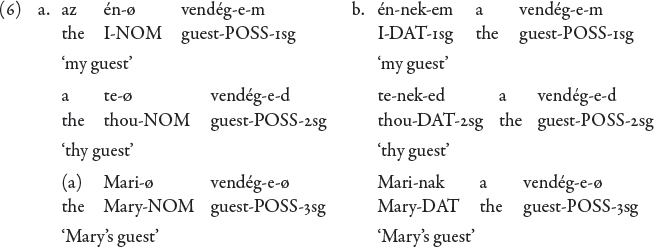

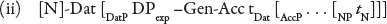

An explicit proposal about the “genesis” of the Dative case was made by Szabolcsi (1983). In a careful study of the Hungarian possessive construction, she demonstrated that the Possessor argument in Hungarian gets the Dative case as a result of movement. The phenomenon she had to account for was a puzzling case alternation on the Possessor, illustrated in (6) (Szabolcsi 1983:89, 91):

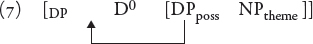

When the Possessor is to the right of a definite determiner, it is Nominative; when it is to the left of the determiner, it is Dative. Szabolcsi’s analysis (spelt out more explicitly in Szabolcsi 1994, § 4) was that in the possessive construction, a D0 takes as its complement a small clause consisting of the Possessor DP and the theme NP; but the Possessor DP can—and in some cases, must—move to the Spec of D0:

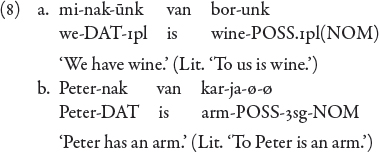

As a result of this movement it gets Dative case. The Possessor can now move out of the possessive NP structure altogether, but the Dative case is retained. The possessive clause of Hungarian has a copula, and the Possessor moves to the subject position of this copula; so that the possessive clause of Hungarian comes out as in (8) ((8a) from Szabolcsi 1994; (8b) from Szabolcsi 1981, cited by Freeze 1992):

In Szabolcsi (1983) there is a suggestion that the Dative case that the Possessor gets in Spec,DP could be an instance of exceptional case marking by an “outside” governor of the DP structure; but this analysis is abandoned in Szabolcsi 1994, which offers no account of how the movement to Spec,DP brings about Dative case. However the thing to bear in mind—what the data tell us—is that the Dative case comes about only after movement.

In Amritavalli & Jayaseelan (2003), we suggested that a Case Phrase (KP) is generated above the DP structure shown in (7); and that it is by moving into the Spec of this KP that the Possessor argument gets Dative case.

Our assumption was that a Dative KP is optionally generated above the basic predication; and that when it is generated, the Kdat “attracts” the nearest nominal phrase to its Spec position.

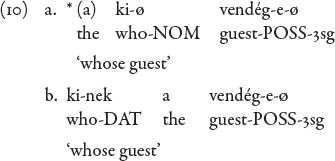

But there is a small problem about saying this. The generation of the Dative KP is not really optional. If the Hungarian possessive structure is indefinite—i.e. if the structure shown in (7) is headed by an indefinite D (which has a null lexical realization in Hungarian)—the movement of the Possessor argument is obligatory; cf. the sentences of (8), where ‘wine’/ ‘arm’ is indefinite. This movement is also obligatory if the Possessor argument is a wh-phrase, cf. (10) (Szabolcsi 1983:91):

The movement (then) is triggered by other factors (like indefiniteness or a wh-feature); and it would seem that it is the movement that forces the derivation to generate a Dative KP. In other words, the case is a reflex of the movement.

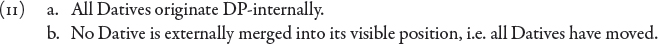

In a recent paper, Kayne (2010) extends Szabolcsi’s analysis of the Hungarian possessor Dative to Datives in general in other European languages, and makes the following claims:

He however—like Szabolcsi earlier—stops short of suggesting how the Dative case suffix actually comes to be.

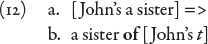

To address this question, we look at two analyses of predicate inversion, proposed in Kayne (1993) and den Dikken (1996, 2006). Kayne (ibid.:109) notes that Hungarian and English have different strategies in dealing with an indefinite possessive construction: whereas the Possessor DP moves out and receives Dative case in Hungarian, the theme NP moves out in English, cf.

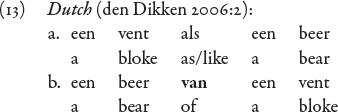

Kayne suggests that the preposition ‘of’ is inserted “to Case-license DPposs.” But actually DPposs already has a case, namely the Genitive. Den Dikken has a different proposal here: he suggests that predicate inversion needs a LINKER. His examples are:

(13a) is an uninverted structure; in (13b), the predicate has been inverted, necessitating the insertion of a LINKER, van ‘of’.

Adopting den Dikken’s idea of a LINKER, let us say that what Szabolcsi observed in Hungarian was the insertion of a LINKER. In other words, the Dative case suffix has the function of a LINKER.5

Now recall that there are two other cases on the Case Hierarchy that we motivated in § 1; we reproduce it below:

Viewed in the light of Caha’s (2007, 2009) proposal that we outlined earlier, this hierarchy in effect says that Accusative and Genitive are generated before Dative on a nominal, when the latter has the Dative case. Now if we combine this with the idea of the DP-internal origin of Datives (Szabolcsi 1983, Kayne 2010), we are pushed towards some very interesting questions (or conjectures): Do Accusative and Genitive also have a DP-internal origin? Are these two cases too, LINKERs triggered by movement?

Consider the Malayalam forms of (2b), e.g. John-in-ə ‘John-GEN-DAT’. We have overt evidence here of a Genitive “within” a Dative, arguing that the Genitive marking happened “prior” to the Dative marking. So the Genitive must have been generated DP-internally. In the case of the Genitive, this conclusion is not difficult to concede, because the traditional analysis of Genitive is that it is a case assigned to the specifier of an NP (Chomsky 1981).

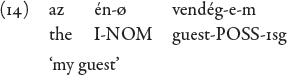

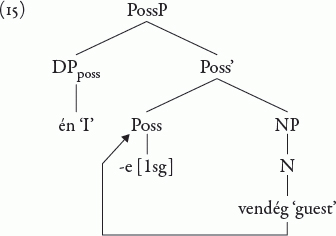

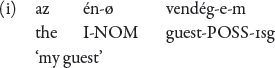

In Jayaseelan (2007a), I proposed an analysis of the Hungarian possessive construction that departed in some respects from Szabolcsi’s (1994) structure shown earlier in (7). Note that in a form like (14) (see (6a)):

the NP ‘guest’ has two suffixes: a possessive marker -e, followed by an agreement morpheme. I proposed that the possessive marker is the head of the small clause, which takes the theme NP as its complement and DPposs in its Spec position; and that the AGR element is just an agreement matrix on this head, cf. English (finite) T. In Hungarian, the theme NP adjoins to the head:6

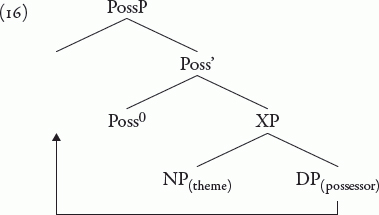

But possibly, (15) itself is a structure generated by movement. In the initial structure, the theme NP (the possessee) and the possessor DP could be in a hierarchically equal relation in violation of antisymmetry, “requiring” one of the terms to move (Moro 2000). The Genitive marker could then be the LINKER triggered by the movement:

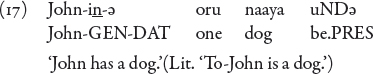

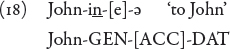

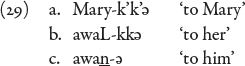

Consider the double case-marking on the subject in the following possessive construction in Malayalam:

If our Case Hierarchy (5) is right, there must be an unpronounced Accusative in the Possessor DP of (17), whose proper underlying representation should be (18). (-e is the Malayalam Accusative marker.)

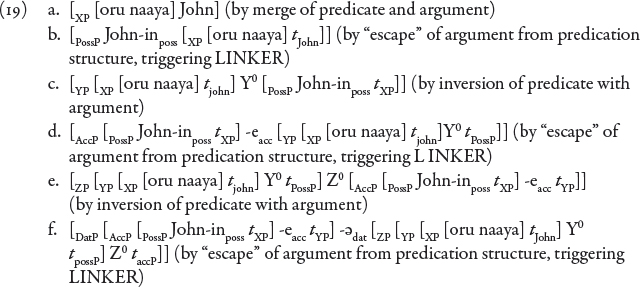

We can derive this sequence as follows, if we may assume that these cases are LINKERs generated by predicate-argument inversion:7

The advantage of postulating an “invisible” Accusative case immediately below the Dative case will become clear in analyses we propose in Section 4.

3.1. Amritavalli & Jayaseelan (2003)—also Amritavalli (2007), Jayaseelan (2007b)—argued that Adjective is a derived category which is generated when Noun adjoins to Case. We presented both distributional and morphological evidence in support of this claim.

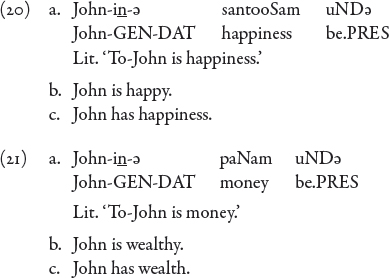

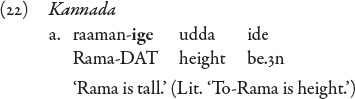

The distributional argument was that we could account for a three-way alternation in the way languages express the Experiencer notion or the Possessor notion; cf. (20) and (21). (The (a) sentences are Malayalam data.)

In each set, the Malayalam sentence (a) has a Dative subject, the English sentences (b) and (c) have a Nominative subject. But there are other contrasts. In the English sentences, there is a ‘be’/ ‘have’ alternation of the verb, with ‘be’ taking an adjectival complement and ‘have’ a nominal complement. The Malayalam sentence has a copular verb like English (b) but a nominal complement like English (c). How do we account for this complex set of contrasts?

The idea that ‘have’ is underlyingly ‘be + to’—i.e. ‘be’ into which a Preposition/Case has incorporated—is now a well-known and widely accepted analysis; the original insight was that of Benveniste (1966:197): ‘avoir n’est rien autre qu’un être-à inversé’ (‘avoir is nothing other than an inverted être-à’). Kayne (1993), comparing Hungarian and English possessives, suggested that it is the same Dative case that shows up on the subject in the Hungarian possessive construction—cf. (8)—that gets incorporated into ‘be’ to yield the English ‘have’. (See also Freeze 1992, Hoekstra 1993.)

But there is a gap left by this explanation (as it stands). How do we generate an English sentence like the (b) sentence? And what is its relation to (a) and (c)? In (b), the Dative preposition (or case) neither incorporates into ‘be’ to yield ‘have,’ nor shows up on the subject. What has happened to it? In Amritavalli & Jayaseelan (2003) we claimed that a bare Noun (here denoting the Experience or the Possessum) can incorporate into Preposition/Case and yield an Adjective. This explains the (b) sentence, and we now have a complete account of the three-way alternation shown in (20) and (21).

This account also explains why ‘have’ cannot take an adjectival complement, a fact which should be surprising if ‘have’ is derived from ‘be.’ The explanation is that there is only one Dative case here, which can incorporate to yield either ‘have’ or an Adjective but not both.

Now coming to the morphological evidence that Adjective is ‘Noun + Case,’ we first note that Dravidian has hardly any adjectives; indeed it has been argued not to have Adjective as a lexical category (see Zvelebil 1990 for a discussion). But there are a few forms that are functionally adjectival, although transparently denominal. These yield an interesting pattern, cf. the following Kannada examples (Amritavalli & Jayaseelan 2003:29):

When the Dative case does not show up on the subject, it is suffixed to the nominal complement, yielding a form which is clearly adjectival in function.

3.2. Now we shall argue (on similar grounds) that the Verb in Malayalam is a derived category. The two claims—about Adjective and Verb—can be seen to converge on the Kaynean claim (Kayne 2008) that the only “open class” lexical category is Noun, and that the other seemingly open classes are derived by the incorporation of Noun into functional heads.

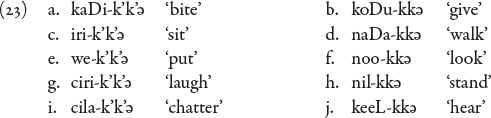

We begin by noting that most Malayalam verb forms end in-k’k’ə or-kkə:

When Sanskrit roots are borrowed to form Malayalam verbs, it is a completely regular process to suffix -k’k’ə/-kkə to it; so that all Sanskrit-derived verbs end in -k’k’ə/-kkə:

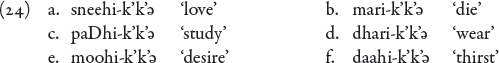

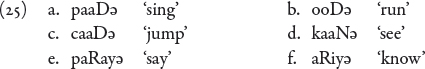

It must be noted that there are also many verb forms in the language that do not end in -k’k’ə/-kkə:

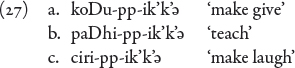

But what is interesting is that when any one of these verbs is causativized, the -k’k’ə/-kkə suffix is the “causativizer”:

When a verb form which ends in -k’k’ə/-kkə is causativized—adding another -k’k’ə/-kkə to it—there is a “dissimilation” process in morphology whereby the first -k’k’ə/-kkə becomes -ppə:

See Madhavan (2006) for a detailed study of this -k’k’ə/-kkə suffixation process; he argues that -k’k’ə/-kkə is only a verbalizer and not a causativizer per se. (See also Killimangalam & Michaels 2006.)

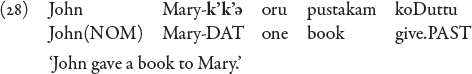

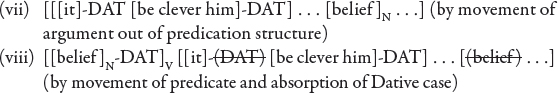

What has not been noticed hitherto is that this verbalizer is homophonous with the Dative case in Malayalam, cf. (28) (= (1a)):8

As we said in § 1, the Dative case has three allomorphs: -k’k’ə, -kkə, and -ə:

The Malayalam verb forms that do not end in -k’k’ə/-kkə—illustrated in (25)—could very well have the third allomorph -ə in their composition; this -ə would be easily elided or assimilated when other suffixes are added to the verb. In other words, the Malayalam verb forms could be completely regular in being formed with the help of the Dative case.9

If both adjectives and verbs are nominal roots that have incorporated the Dative case, a natural question to ask is: what constitutes their difference? While I shall not provide anything like an adequate answer here, let me make an initial observation: A salient difference between the two categories is that adjectives are forms that do not raise to Tense, while verbs are forms that do. It must be the raising to Tense that gives a verb an event reading. In a parallel fashion, adjectives may raise to the head of a Degree Phrase, giving them the possibility of degree modification. Whether a form will raise to Tense or Degree Phrase seems to be partially determined by its meaning: it seems correct to say that event-denoting predicates, if they ‘exit’ out of the predication structure and incorporate case (see next section), invariably raise to Tense. Most stative predicates (on the other hand) do not raise to Tense, although a few do. But a full investigation of this question is beyond the scope of this paper.10

We discussed in § 2 how an argument in Malayalam gets suffixed with three cases, namely Genitive, Accusative, and Dative (in that order) in the course of exiting the predication structure it is merged in. The example we discussed was (17) (repeated below):

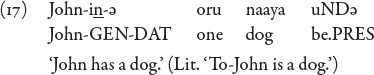

In this example, the predicate nominal oru naaya ‘a dog’ is a complex nominal expression—as it typically is, in the possessive construction. But if we take an experiencer predicate, the NP denoting the experience is always (or nearly always) a simple nominal element, N0. In this case, an alternative derivation is possible in Malayalam: the predicate nominal can “absorb” the Dative case of the experiencer DP, and become a verb.11 We get sentence pairs like the following:

The Dative case is on the experiencer argument in (30a) and on the verb in (30b).

If the verb removes the Dative case from the experiencer DP, we expect it to surface with the Accusative case. But this is not what we see in (30b). I explain it in terms of the following claim:

As a consequence, in (30b), the single argument of the intransitive predicate surfaces with Nominative case (no case).

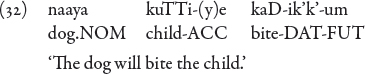

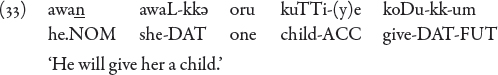

However the Accusative case surfaces when we have a transitive predicate, cf.

When we have a ditransitive predicate, we get a sentence like the following:

This traditionally-recognized case-marking pattern can now be given a non-traditional explanation. The verb formation process absorbs the Dative case from the first argument that the predicate merges with, which therefore surfaces with the Accusative case (direct object). The finite INFL absorbs all the cases of the highest argument, which exhibits no case, i.e. Nominative case. The middle argument (indirect object) preserves all the structural cases that it acquires in the course of exiting the predication structure it is merged in, and therefore surfaces with the Dative case.

Let us now make explicit an assumption underlying our discussion of (32) and (33). The Dative case is generated not merely on the Possessor or Experiencer argument of the possessive/ experiencer construction. Every argument (we are assuming) is merged with a predicate in a predication structure at the point when it enters the derivation; and if it exits the predication structure—essentially in the way described by Szabolcsi (1983) –, it must acquire the Dative case in the process. This implies the following claim:

We shall see some support for this large claim in the next section.14

We note at this point that our analysis of the Accusative case in (33) and (34) is dependent on two of our early postulates in the paper: firstly, our adoption of Caha’s (2007, 2009) claim that the visible case on a nominal expression is only the top layer of what is underlyingly multiple ‘layers’ of case; and secondly, our Case Hierarchy (5), which has Accusative immediately below Dative. Many intriguing alternations of Dative and Accusative in languages can be explained in terms of these hypotheses.15

In this section we try to answer some of the obvious questions that arise with respect to our proposal about verb formation in Malayalam.

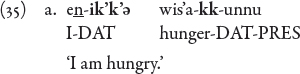

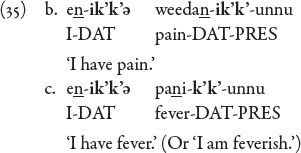

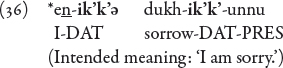

One problem is the appearance of two Datives in what is seemingly a one-argument clause; cf.

If the verb formation takes away a Dative case, how does the subject surface with its Dative case intact? There is also an ancillary question: since this is a finite clause, where is the Nominative NP that INFL agrees with?

Other predicates denoting physical experience also exhibit the same pattern as (35a), cf.

But predicates denoting mental experience do not have this pattern. Thus the sentences of (30) have no alternative realization like (36):

Why should physical and mental experience predicates diverge in their syntax in this puzzling fashion?

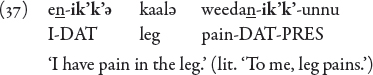

The answer to this problem, argued in Jayaseelan (2004:239-240), is that there is an underlying pro, marked Nominative, which is the “syntactic subject” of the sentences of (35); more generally, the ‘dative construction’ in Dravidian always has a Nominative NP. We can now say that this pro, which is the first argument of the predicate, yields up a Dative case for verb formation; and INFL removes its other structural cases and agrees with it.16 The pro seems to denote a body part (or the body); in fact, it can sometimes be replaced by an overt nominal denoting a body part, cf.

The difference in the mental experience predicate (then) is that there is no corresponding covert nominal denoting a mind part.17

Note how the above explanation depends on the covert argument pro in (35), or the overt argument kaalə in (37), having a Dative case that it can yield up for verb formation. This follows if every argument gets Dative case by default, as per our proposal (34). Also note that if we had treated the homophony of the Dative case-suffix and the verbalizer in Malayalam as merely an accident of morphology, we would not have had an explanation of the contrast in grammaticality between (35) and (36).

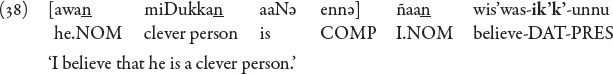

I wish to suggest a solution along the same lines for another possible problem for our claim that verb formation requires a Dative case from an argument, specifically its first argument: what happens when the verb takes a clausal complement? Cf. (38):

Where does wis’was—from Skt. wis’waas ‘belief’—get its Dative case from?

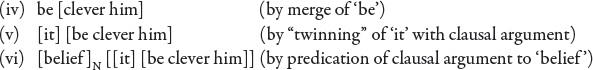

Rosenbaum (1967) had an account of English complementation which claimed that English clausal complements are associated with an underlying ‘it’ (which is mostly deleted but can sometimes surface). This analysis has been revived and generalized by Kayne (2008) in the context of a proposal that all clausal complementation should be reanalyzed as covert relativization. We can (in line with this proposal) assume that the nominal predicate wis’wa(a)s takes a clausal complement with an associated covert pronoun; and that this pronoun acquires Dative case as a result of movement, which it yields up to turn the nominal predicate into a verb.

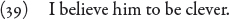

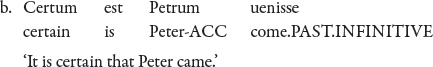

If we wish to conclude this section on a more ambitious note by trying to see if our analysis of Malayalam clausal complementation can be extended to other languages, I suggest that an interesting case to look at is the English nonfinite complement; for it gives us overt evidence of the Dative case on the clausal argument. Consider (39):

The infinitival ‘to’ has been variously analyzed, e.g. as a prepositional complementizer (Kayne 1999); but I give below a derivation that makes it simply the Dative preposition, the same as the preposition on the second argument in ‘give a book to Mary.’

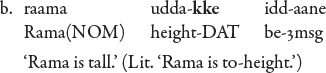

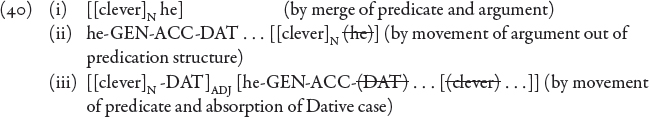

The initial steps of the derivation of (39) will be as follows:

At this stage we have an adjective that takes an Accusative argument, ‘clever him’.

We shall assume that both parts of the “twinned” structure—‘it’ and the clause—are separately marked Dative (strictly, ‘GEN-ACC-DAT’, but we indicate only ‘DAT’ here) when they together exit the predication structure:

We are assuming that only the Dative of the “silent” ‘it’ is absorbed by the predicate, and that the clause ‘be clever him’ retains the Dative case. In English the Dative case is realized as the preposition ‘to’.18

The derivation at this point yields the string ‘believe to be clever him’ (assuming ‘it’-deletion). We must postulate two further movements: ‘him’ raises to a position above the VP headed by ‘believe’ (possibly the object shift position); and ‘believe’ raises still higher, to the position of its inflection.

The main claim of this paper is that the Malayalam Verb is a non-primitive lexical category, which is derived when a predicate which is N0 “absorbs” the Dative case of the first argument that it merges with. This can be seen as an extension of the claim about the genesis of Adjective made in Amritavalli & Jayaseelan (2003). It has an interesting similarity-and-difference relation to Pesetsky’s (2012) proposal that Verb originates when Accusative case is affixed to a categoryless root; and it is in agreement with Kayne’s (2008) claim that two of the major lexical categories, Verb and Adjective, originate by functional affixation to the primitive category of Noun.

Some ancillary ideas also came up in the course of pursuing the main claim, none of them (however) crucial for the adoption of the latter. I suggested that the three cases, Genitive, Accusative and Dative, which form a sequence in a universal Case Hierarchy, are all generated as LINKERs in the course of an argument ‘exiting’ the predication structure in which it is initially merged. The three cases are generated in that order on the argument, with Genitive as the innermost and Dative as the outermost case; and Accusative case is “revealed” when verb formation “absorbs” the argument’s Dative case. This idea breaks the traditional link between a verb’s transitivity and its ability to determine Accusative case on its first argument (known in generative grammar as Burzio’s Generalization). In my system, I appeal to finite INFL’s ability (or need) to remove all structural cases from an argument, to explain the Nominative case shown by the single argument of intransitive/unaccusative verbs in finite clauses.

* Many of the ideas presented in this paper were first tried out at workshops and seminars at Nanzan University (Nagoya) over the past seven years or so. The workshops and seminars were part of an international research project whose “prime mover” was Mamoru Saito. This paper therefore owes much to Mamoru. I am very happy to participate with this paper in this festschrift for him. (I wish to thank Richard Kayne for comments on this paper. This paper was presented at the “Faculty of Language: Design and Interfaces” workshop at the Indian Institute of Technology, Delhi, 11-12 February 2013 and at FASAL-3 at the University of Southern California, 9-10 March 2013; I wish to thank the two audiences for helpful discussion.)

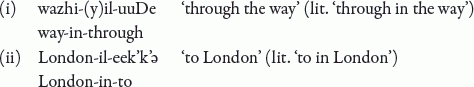

1. Another case that “shows through” is Locative, as in:

2. The Genitive case suffix is either -in(te) or -(u)Te, as in:

(The form -in(te) could be bimorphemic, -in and -te, and the -te could be a phonologically conditioned variant of -Te; in which case the form -inte is an instance of “double case-marking.”)

3. In the colloquial speech of certain parts of Kerala (or of certain social classes), the Genitive in fact surfaces invariably with the Accusative case. Thus the forms of (3a) are realized as: ‘Maryin-e’, ‘aana-(y)in-e’, ‘vaazha-(y)-in-e’.

4. We note that (5) differs from the Blake/Caha hierarchy in one respect: Genitive is above Accusative in their proposal but below Accusative in (5). Caha (2007) appeals to an adjacency theory of Case Syncretism to support his DAT > GEN > ACC order: apparently, in some languages, Dative and Genitive can be syncretic, excluding Accusative. On the other hand, we are—as we indicated above—crucially depending on the Dravidian order of case-stacking: ‘Stem – GEN – ACC.’

5. Den Dikken’s LINKER is a meaningless element which is inserted purely for a structural reason. The Dative case (then)—if our analysis is right—belongs to the class of structural cases. Regarding the other structural cases, namely Nominative, Accusative and Genitive, there is perhaps general agreement that they are not linked to any particular thematic role; but the Dative case is widely believed to have the meaning of Goal. However see Jayaseelan (2009), Caha (2007, 2009) for an account of how the Dative comes to be associated with a null Path head in directional PPs—which could be the basis for this common impression.

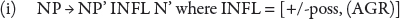

6. As a matter of fact, Szabolcsi’s earlier paper, Szabolcsi (1983), represents (the rule that generates) the structure of the possessive construction as in (i) (see p. 92):

This is meant to bring out the analogy between the possessive marker in NP structure and the INFL in clause structure. (This analysis is apparently abandoned in the later paper.)

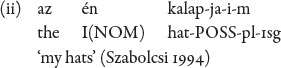

The inflection on the theme NP can also contain a plural marker (for the plurality of the theme NP):

We can accommodate this marker as a second agreement matrix on the possessive-marker head.

7. The inversion in (19b) can be motivated by the argument that the structure in (19a) is too symmetric, but this explanation cannot be extended to the other inversions. I must leave a better understanding of these movements to later research. (Some DP-internal functional heads can be merged in the course of these inversions and may indeed be correlated to them in yet unclear ways, cf. the merge of D0 in Szabolcsi’s structure (7) just prior to the inversion that generates the Dative LINKER.)

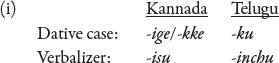

8. Tamil—which is the language closest to Malayalam among the Dravidian languages—also exhibits the same homophony: -k’k’ə /-kkə does duty both as verbalizer and as Dative case. However, Kannada and Telugu show no such homophony, cf.

R. Amritavalli and Rahul Balusu (personal communication) inform me that Telugu -inchu is the Ablative case suffix in the contemporary language. I have not investigated whether it was also the Dative suffix in an earlier stage of the language.

9. Now in retrospect, the analysis of ‘have’ as ‘be + to’ stops being just a “one off” instance; the absorption of the Dative case could be a very general process in verb formation. If in the case of ‘have’, what absorbs the Dative case is the copula, in the case of other verbs (at least in Malayalam) it is a nominal element that absorbs the Dative case.

10. Another important difference appears to be that adjectives are obligatorily unaccusative, in the sense that adjectives take only one argument. I have no account at present of this limitation.

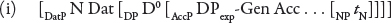

11. We can think of the process in either of two ways: the predicate nominal “preempts” the experiencer DP’s movement into Spec,DatP by moving into that position first:

Or, the experiencer DP gets all its three cases, but the predicate nominal moves up higher and “attracts” the Dative case from it:

12. See Bittner and Hale (1996) for the idea that Nominative case is the absence of case; but this absence of case (we are claiming) comes about because of the absorption of structural cases by finite INFL. Caha (2007, 2009) proposes a “peeling” analysis to account for the absence of case on the Nominative NP: an NP that moves to the Spec of finite INFL “peels away” its cases. Pesetsky (2012) has a system wherein V automatically marks its argument Accusative; then he must (I guess) appeal to the device of ‘overwriting’: finite INFL, identified as D, bearer of Nominative case, overwrites the Accusative case on the single argument of the unaccusative verb. (As regards languages which apparently have an overt Nominative case-suffix, we could perhaps say that the morphological marking is a realization of Agreement with finite Tense as proposed by Pesetsky & Torrego (2001). In Standard Arabic, the Nominative marker is identical with the indicative mood marker on the verb (Al-Balushi 2011).)

13. An argument that does not move completely out of the predication structure will not get Dative case. An example would be the Possessor argument in the Hungarian possessive phrases in (6a), one of which we reproduce below:

In our analysis, the Possessor argument here has undergone one movement and acquired the Genitive case; but the Genitive is incorporated into the theme NP, leaving it without any case, i.e. with Nominative case (see (15) and (16)).

14. Cf. van Riemsdijk’s (2007, 2012) claim that Dative is the default case in German in oblique contexts (i.e. PPs).

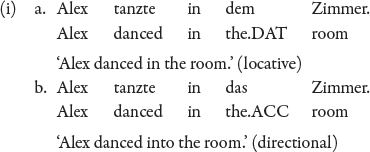

15. I note just one example, a well-known fact in German: the Dative complement of a locative preposition becomes Accusative when the sentence acquires a directional meaning, cf. (i) (Zwarts 2006, cited in Caha 2007):

This can be explained if we may assume that a null Path0 attracts Dative case from the prepositional object, revealing the underlying Accusative (Jayaseelan 2009; but see van Riemsdijk 2007, Caha 2007 for different solutions).

16. Malayalam has no overt subject-verb agreement; but other Dravidian languages do. In these languages, the verb shows 3rd person, singular agreement (what is often called “default agreement”).

A question remains: why does finite INFL remove structural cases from pro, rather than from enik’k’ə ? Experiencer predicates are unaccusatives (Shibatani 1999, Amritavalli 2004); possibly the predicate treats pro as its only argument and the Experiencer DP as an adjunct.

17. The same explanation carries over to an interesting pair of sentences noted in Mohanan & Mohanan (1990):

There is a pro in (ib), but not in (ia).

18. A question arises: why doesn’t the finite clause in the corresponding sentence I believe that he is clever have the preposition ‘to’? The fact is that universally, finite clauses never show overt case. The reason could be that when inversion of argument with predicate takes place, the finite clause itself does not move – only the associated “silent” ‘it’ moves. Therefore the clause does not acquire case. But in the case of a nonfinite clause, both the clause and the associated ‘it’ move, and they separately acquire case.

The small clause in I believe him clever also must have a silent ‘it’ that yields up its Dative case for the generation of the matrix verb. Kayne (2010) posits a silent BE in the small clause; and the silent BE appears to make the preposition ‘to’ also silent – a dependency for which I have no account at present.

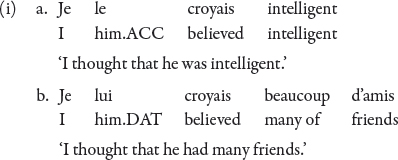

Note that in our account of ECM, the embedded subject’s case is not determined by the matrix verb but by the embedded predicate. This appears to be supported by the following French data (from Kayne 2010):

In (ia) the adjective absorbs the Dative case of its argument, which therefore shows up with Accusative case; but in (ib) the nominal predicate absorbs no case and therefore its argument keeps its Dative case intact.

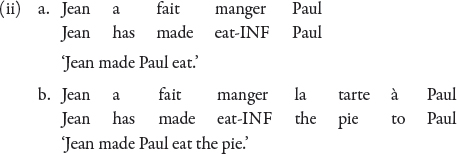

The embedded subject’s case is affected also by the transitivity of the embedded verb, cf. (ii) (from Kayne 2004):

When ‘Paul’ is the first argument of ‘eat’, it loses its Dative case to the verb and surfaces with Accusative case; but when it is the verb’s second argument, it retains its Dative case (realized as the preposition à).

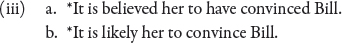

The English data in (iii) discussed by Lasnik (2004:270) represents the classic argument for the infinitival subject’s dependency on the matrix predicate for its case:

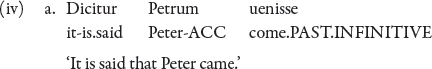

But Lasnik also notes (ibid., p.271) that “[t]here are Accusative-Infinitive constructions in some other languages where the accusative subject does not display this dependence on the matrix verb;” and cites from Rouveret and Vergnaud (1980) the following Latin sentences which are fine:

Let us say that the pleonastic ‘it’ of (iii a, b) is the ‘it’ “twinned” with the embedded clause; and that English moves this ‘it’ to the matrix subject position only as a last resort. When the embedded clause is finite, nothing can be moved out of it by A-movement, forcing ‘it’ to move; but there is no such prohibition with a nonfinite complement, so the embedded subject moves.

References

Al-Balushi, Rashid Ali (2011) Case in Standard Arabic: the Untravelled Paths, Doctoral dissertation, University of Toronto.

Amritavalli, R. (2004) “Experiencer Datives in Kannada,” Non-nominative Subjects, ed. by P. Bhaskararao and K. V. Subbarao, Vol. 1, 1–24, John Benjamins, Amsterdam.

Amritavalli, R. (2007) “Syntactic Categories and Lexical Argument Structure,” Argument Structure, ed. by Eric Reuland, Tanmoy Bhattacharya and Giorgos Spathas, John Benjamins, Amsterdam.

Amritavalli, R. and K. A. Jayaseelan (2003) “The Genesis of Syntactic Categories and Parametric Variation,” Generative Grammar in a Broader Perspective: Proceedings of the 4th GLOW in Asia 2003, ed. by H-J Yoon, Hankook, Seoul.

Benveniste, E. (1966) Problèmes de linguistique générale, Gallimard, Paris.

Bittner, M. and K. Hale (1996) “The Structural Determination of Case and Agreement,” Linguistic Inquiry 27: 1–68.

Blake, Barry J. (1994) Case (Second Edition), Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (U.K.).

Caha, Pavel (2007) “Case Movement in PPs,” Tromsø Working Papers on Language & Linguistics: Nordlyd 34.2. Special issue on Space, Motion, and Result, ed. by Monika Bašić, Marina Pantcheva, Minjeong Son, and Peter Svenonius, 239–299, CASTL, Tromsø:. Available at http://www.ub.uit.no/baser/nordlyd/

Caha, Pavel (2009) The Nano-Syntax of Case, Doctoral dissertation, University of Tromsø. [http://ling.auf.net/lingBuzz/000956]

Caha, Pavel (2010) “The Germanic Locative-Directional Alternation: A Peeling Account,” The Journal of Comparative Germanic Linguistics 13(3), 180–223.

Chomsky, Noam (1981) Lectures on Government and Binding, Foris, Dordrecht.

den Dikken, Marcel (1996) “How External is the External Argument?” paper presented at WECOL 1996. Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam/HIL.

den Dikken, Marcel (2006) Relators and Linkers: The Syntax of Predication, Predicate Inversion, and Copulas, The MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass.

Freeze, Ray (1992) “Existentials and Other Locatives,” Language 68(3):553–595.

Hoekstra, T. (1995) “To Have to be Dative,” Studies in Comparative Germanic Syntax, ed. by H. Haider, S. Olsen, and S. Vikner, 119–137, Kluwer, Dordrecht.

Jayaseelan, K. A. (2004) “The Possessor-Experiencer Dative in Malayalam,” Non-nominative Subjects, ed. by P. Bhaskararao and K. V. Subbarao, Vol. 1, 227–244, John Benjamins, Amsterdam.

Jayaseelan, K. A. (2007a) “Possessive, Locative and Experiencer,” paper presented at the 2007 International Conference on Linguistics in Korea (ICLK-2007), 20 January 2007.

Jayaseelan, K. A. (2007b) “The Argument Structure of the Dative Construction,” Argument Structure, ed. by Eric Reuland, Tanmoy Bhattacharya and Giorgos Spathas, 37–48, John Benjamins, Amsterdam.

Jayaseelan, K. A. (2009) “Case Hierarchy and Theories of Case,” paper presented at the Third Workshop of the International Research Project on Comparative Syntax and Language Acquisition, Nanzan University (Nagoya), March 12, 2009.

Kayne, R. (1993) “Toward a Modular Theory of Auxiliary Selection,” Studia Linguistica 47, 3–31. [Reprinted in R. Kayne, Parameters and Universals, 2000, 107–130, Oxford University Press, New York.]

Kayne, R. (1999) “Prepositional Complementizers as Attractors,” Probus 11: 39–73. [Reprinted in R. Kayne, Parameters and Universals, 2000, 282–313, Oxford University Press, New York.]

Kayne, R. (2004) “Prepositions as Probes,” Structures and Beyond: The Cartography of Syntactic Structures, Vol. 3, ed. by Adriana Belletti, Oxford University Press, New York. [Reprinted in R. Kayne, Movement and Silence, 2005, 85–104, Oxford University Press, New York.]

Kayne, R. (2008) “Antisymmetry and the Lexicon,” Linguistic Variation Yearbook, 8 (2008), 1–31. [Reprinted in R. Kayne, Comparisons and Contrasts, 2010, 165–189, Oxford University Press, New York.]

Kayne, R. (2010) “The DP-Internal Origin of Datives,” paper presented at the 4th European Dialect Syntax Workshop in Donostia/San Sebastián, 22 June 2010.

Killimangalam, A. and J. Michaels (2006) “The three ‘ikk’s in Malayalam,” unpublished MIT ms.

Krishnamurti, Bh. (2003) The Dravidian Languages, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (U.K.).

Lasnik, H. (2004) “The Accusative Subject in the Accusative-Infinitive Construction,” Non-nominative Subjects, ed. by P. Bhaskararao and K. V. Subbarao, Vol. 1, 269–281, John Benjamins, Amsterdam.

Madhavan, P. (2006) “The Layered vP: Transitivity Alternations in Malayalam,” paper presented at the Hyderabad-Nanzan Joint Workshop on the Syntax-Semantics Interface, Nanzan University (Nagoya), 21–22 October 2006.

Marantz, Alec (1997) “No Escape from Syntax: Don’t Try Morphological Analysis in the Privacy of Your Own Lexicon,” University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics, ed. by A. Dimitriadis, L. Siegel et al., 4(2): 201–225, Proceedings of the 21st Annual Penn Linguistics Colloquium.

Marantz, Alec (forthcoming) Phases and Words. Available at http://homepages.nyu.edu/~ma988/Phase_in_Words_Final.pdf

Mohanan, K. P. and Tara Mohanan (1990) “Dative Subjects in Malayalam: Semantic Information in Syntax,” Experiencer Subjects in South Asian Languages, ed. by Manindra K. Verma & K. P. Mohanan, 43–57, CSLI, Stanford.

Moro, Andrea (2000) Dynamic Antisymmetry, MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass.

Pesetsky, David (2007) “Undermerge … and the Secret Genitive Inside Every Russian Noun,” Handout of a talk at FASL 16.

Pesetsky, David (2012) “Russian Case Morphology and the Syntactic Categories,” paper presented at LISSIM 6, Kangra (India), May-June 2012.

Pesetsky, David and Esther Torrego (2001) “T-to-C Movement: Causes and Consequences,” Ken Hale: A Life in Language, ed. by Michael Kenstowicz, 355–426, MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass.

van Riemsdijk, Henk (2007) “Case in Spatial Adpositional Phrases: The Dative-Accusative Alternation in German,” Pitar Mos: A building with a view. Festschrift for Alexandra Cornilescu, ed. by Gabriela Alboiu, Andrei Avram, Larisa Avram, and Isac Dana, 1-23, Bucharest University Press, Bucharest.

van Riemsdijk, Henk (2012) “Discerning Default Datives,” Discourse and Grammar, ed. by Günther Grewendorf and Ede Zimmermann, Mouton de Gruyter, Berlin.

Rosenbaum, P. S. (1967) The Grammar of English Predicate Complement Constructions, The MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass.

Rouveret, A. and J.-R. Vergnaud (1980) “Specifying reference to the subject,” Linguistic Inquiry 11:97–202.

Shibatani, M. (1999) “Dative-Subject Constructions Twenty-Two Years Later,” Studies in the Linguistic Sciences 29(2): 45–76.

Starke, Michal (2005) Nanosyntax class lectures, Spring 2005, University of Tromsø. [Cited in Caha 2009]

Szabolcsi, A. (1981) “The Possessive Construction in Hungarian: A Configurational Category in a Non-Configurational Language,” Acta Linguistica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 31: 261–289.

Szabolcsi, A. (1983) “The Possessor that Ran Away from Home,” The Linguistic Review 3: 89–102.

Szabolcsi, A. (1994) “The Noun Phrase,” Syntax and Semantics 27: The Syntactic Structure of Hungarian, ed. by F. Kiefer and K.E. Kiss, 179–274, Academic Press, San Diego.

Zvelebil, K. V. (1990) Dravidian Linguistics: an Introduction, Pondicherry Institute of Linguistics and Culture, Pondicherry.

Zwarts, Joost (2006) “Case Marking Direction. The Accusative in German PPs,” paper presented at the 42nd meeting of the Chicago Linguistic Society, Chicago, 7 April 2006. Available at: http://www.let.uu.nl/users/Joost.Zwarts/personal/Papers/CLS.pdf.