R. Amritavalli

The experiencer dative construction in South Asian languages has received the attention of linguists for about half a century now (Verma & Mohanan 1990; Shibatani 1999; Bhaskararao & Subbarao 2004).1 This investigation has centered mainly on the subject-like properties of the experiencer dative argument. Amritavalli and Jayaseelan (2003, and related papers; henceforth A&J) turned their attention to the experience-denoting noun in the predicate. In this paper, I examine the verb in the predicate. I begin with an account of the event structure projection, in terms of the first-phase syntax of Ramchand (2008), of the verbs bar-‘come’ and aag- ‘happen, become’ in Kannada that are typical of the construction.

A&J pointed out a significant, if neglected, fact about the dative experiencer construction: its predicate categorially expresses the experience as a noun, whereas nominative experiencer constructions express it as an adjective. Not all four of the syntactic categories N, V, A and P, which correspond respectively to the semantic types of entities, events, states and relations, are universal; many languages lack A and P (Hale & Keyser 1993). The impoverishment of the category A in the Dravidian languages correlates with the prevalence of the experiencer dative construction in them. A&J postulated a “floating” dative case in experiencer constructions with be, which appears on the experiencer in Dravidian, or (in languages like English) is absorbed by the experience N to yield the syntactic category Adjective.

I shall here widen the inquiry to verbs other than be, and argue that the experiencer and experience denoting nouns in the dative construction are in a “possession” relation expressed by dative case. They occur in a small clause in the result projection of the event structure of the verb. Kannada bar-, like English come, is an activity or accomplishment verb when it occurs with nominative subjects. But in the dative experiencer construction, it is a presentational verb—a light verb that projects a “rich” result and a “poor” process (Ramchand 2008:148). The structure it occurs in is that of double object verbs in English, minus the init projection. My account of bar- is consistent with the proposal in Higginbotham (1999) that achievement verbs allow telicity by “classifying events that are themselves already results.”

Turning to the verb aag-, I show that its paraphrases become and happen follow from the nature of its small clause complement. A copular small clause complement yields the become interpretation via “incorporation” of the copula into the process verb; in this case, aag- has a nominative subject. A dative small clause argument yields the happen reading; dative case in Kannada does not “incorporate” into the verb, and the experiencer dative construction results. This structurally derived alternation in the meanings of aag- in its occurrences with a dative experiencer or nominative subject argues against traditional accounts of experiencer dative case as a “governed” or “quirky” case assigned semantically by a class of “psychological” predicates.

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 sets out the main theoretical assumptions in this paper: a first-phase syntax of event structure that facilitates a “rich” result sub event, and a dative case with the semantics of possession that is overt in Kannada, but covert in have languages like English. Section 3 is an exploration of the event structures projected by bar- in its occurrences with nominative subjects and dative experiencers, and proposes an event structure for the latter. Section 4 addresses issues in the representation of stative verbs that arise out of my analysis. I distinguish the result phrase that I posit from resultatives of accomplishment verbs, and outline Higginbotham’s account of telicity in achievement verbs. Section 5 presents an analysis of the verb aag- as ‘come to be,’ ‘come to pass’ or ‘come to have;’ and Section 6 concludes with the argument that the experiencer dative construction is the sub part of the double object construction that does not project the causative sub event.

Ramchand (2008) is a recent account within minimalist assumptions of how lexical items are mapped into the syntax. Verbs have argument structure, their arguments have recognizable thematic roles, and there are identifiable regularities in the thematic-syntactic mapping. Such grammatically relevant aspects of lexical meaning can be thought of as arising out of the computational system in syntax. Ramchand proposes an event-building phase in the syntax (the ‘first phase’), taking into account core predicational relations and syntactic argument types. The event-building portion of a proposition is assumed to be prior to case marking/checking, agreement or tense (op. cit.:16, n.4). In her system of event structure, an event is decomposed into three sub event types. There is a causing projection initP whose subject is the external argument, the INITIATOR; a process-denoting projection procP, whose subject is the UNDERGOER; and a result state resP whose subject is the RESULTEE. The category label V(erb) is correspondingly decomposed into [init], [proc] and [res], and a lexical item can project these features to form a predication.

Let me add (at a reviewer’s instance) a word about the choice of this “complex and costly” framework for a construction that has been much analyzed “using more ‘standard’ approaches.” My exploration of some non-obvious properties of a construction long viewed as an areal/typological phenomenon of “quirky” or “governed” case assigned by a semantically identifiable class of predicates, and earlier, even speculated to reflect an “experiential” rather than “agentive” world view (Klaiman 1986), aims at an explanatory account of it in terms of parametric variation in the categorial representation of stative predications, and the expression of the possession relation. In the absence of Adjectives, a predicate Noun designates the experiential state of the experiencer, and a possession-denoting case relates the two. The principled and restrictive account of the syntactic projection of various aspectual categories of verbs in the first phase is what prompts and facilitates this analysis.

The idea that syntax represents sub lexical units, i.e. of lexical decomposition in the syntax, allows us to unify the possession relation in the experiencer dative construction with the same relation in an apparently different construction in a genetically and typologically unrelated language: namely, the double object construction in English. The postulation of an abstract preposition of possession in the latter (Harley 2002, building on Pesetsky 1995; Richards 2001) was consequent on Kayne’s (2000[1993]) decomposition of possessive have into be and a dative case. (An earlier attempt at a parametric approach to the experiencer dative construction, Jayaseelan 1990, cast in the mould of pro-drop and scrambling, had postulated a “complex predicate” formed by the experiencer and the experience but left unspecified the nature of the relation between them.) Lexical decomposition receives a natural implementation within Distributed Morphology (which allows “late” lexical insertion, after syntactic trees have been built up). The decomposition of transitive/ causative verbs into v and V (Chomsky 1995:315ff.; Kratzer 1996) is now part of the standard generative machinery, even as v has later been split into various ad hoc ‘flavours.’

First phase syntax is built up by Merge. A verb may be specified for more than one of the features [init], [proc] and [res]; the system allows it to project a feature and Merge with its argument, then project again and Remerge. Remerge is a way of implementing “head movement” in this framework; it also follows from a copy theory of movement. A single argument can now have more than one thematic role (a “composite role”), as it can be remerged into more than one projection, depending on the verb’s event structure. A second novel idea is Underassociation. A lexical item bears multiple features and associates with multiple nodes: it lexicalizes chunks of trees. Its features may be a superset of the sequence to be spelled out; thus, it can have Underassociated features, which have to be independently identified and linked with it under specific conditions.

Ramchand’s main concern is with eventive predicates, and her suggestions about how to represent stative predicates are much more programmatic. I will return to these in the sections where I present my analysis, following my explication of the Kannada data. Here, I only illustrate briefly her treatment of verbs of the come class. For Levin and Rappoport-Hovav (1995; henceforth L&RH), come is an unaccusative verb of inherently directed motion (L&RH: 111). Ramchand, however, treats as unaccusative only such intransitive (inchoative) verbs like break that have causative forms (2008:78, n.6).2 In her system, come, like the intransitive verbs arrive and fall that she discusses, would project all three of [init, proc, res]; the single argument of these verbs would have this composite thematic role. The telicity of these verbs, their having an end state, argues that they project [res]. They must also (argues Ramchand) project [init], because (i) they do not allow causativization, and (ii) unlike “the true unaccusatives,” they do not allow their -en participle to occur pre-nominally (contrast the broken stick with *the arrived train, *the come guests). The possibility of the recently arrived train (moreover) suggests that “modification related to the initiation portion of the event is required” because the argument of arrive is an INITIATOR as well as an UNDERGOER or RESULTEE. The sentence Michael arrived thus has the representation (1) (=her (34), p. 79).

More pertinent to my analysis of the dative experiencer construction is a suggestion Ramchand offers about “light verbs” in complex predicate constructions in Indic. This construction is the counterpart of the verb-particle construction in English. Compare (2–3). The particle in (2), and the second verb in (3), force a resultative reading.

In (2), the particle up identifies the [res] projected by the verb, and it is ‘light:’ i.e. it has “a fairly general and abstract semantics” (Ramchand op.cit.: 136). The sub events into which the eating event is decomposed are here separately lexically identified by the verb and the particle. So eat must underassociate its [res] feature, and unify its “lexical-encyclopedic” content with up (by a process like Agree). In this scenario, one of the unifying items is forced to be ‘light;’ in (2), the particle is light (“plausibly one of the salient properties of particles in English” (loc. cit.)).

In (3), a verb does the duty of the particle in English; the second verb is semantically ‘light.’ Interestingly, it is this verb and not the content verb eat that carries tense and agreement. Ramchand argues from the head-finality of the Indic languages that the proc head must (at some level) follow the res head. Taken together, these facts argue that the light verb is the prochead (and where projected, the init head) of the complex predicate. Therefore, the verb eat, which is encyclopedically rich, is the res head in (3); and indeed, it is realized as a perfect participle in Kannada and Bangla. Standardly, the light verb has been considered to add telicity to the predicate; however (Ramchand points out) this “descriptive statement can easily be reconciled with the facts once we realize that it is the light verb that selects for a resP in this structure” (p. 146); “the crucial contribution of the tensed verb here is as the process descriptor … that selects the resP.”

First phase predicate decomposition, thus, accounts for “result augmentation” in the verb-particle and complex predicate constructions. The difference between (2) and (3) lies in “how rich the lexical-encyclopedic content of each part of the first phase syntax is.” In the verb-particle construction (2), “the main verb provides the bulk of the real-world content, and the particle representing the result is fairly abstract, or impoverished.” In the complex predicate (3), the res head is rich in encyclopedic content, but the proc element is a light verb. In English as well, argues Ramchand (p. 148), cases “can be detected, whereby a ‘light’ verb joins forces with a richly contentful final state to create a complex predication:”

Notice that (4) instantiates “causative” get, and not its unaccusative counterpart, Her boyfriend got arrested. Ramchand’s discussion of “result augmentation” is limited to accomplishment verbs, i.e. verbs that have a causal subevent. The literature on resultatives has considered achievement verbs to not allow result phrases. I shall argue in Section 4.2 that the “rich res, poor proc” account be extended to achievement verbs.

Kannada expresses inalienable possession with a “dative of possession” construction. There is no verb have in this language.

A&J note that English, which expresses possession with the verb have in (6a), has a vestigial and restricted dative of possession construction (6b) which corresponds word-for-word (modulo word order and expletive pro) to the Kannada “dative of possession” (7).3

The idea that have is derived from be by the incorporation of a prepositional dative case (Kayne 2000 [1993]; also Freeze 1992) explains these data. The be and have sentences in (6) are related by the incorporation of the prepositional dative in (6b) into the verb in (6a), which surfaces as have.4 Kannada has no verb have because dative case does not incorporate into be in Kannada; this case surfaces instead on the possessor.

In Ramchand’s framework, the dative of possession can be simply expressed as an XP headed (in Kannada) by dative case ge-, which relates two entities: a possessor and a possession. (Following Antisymmetry (Kayne 1994), the representations for Kannada are in the head-complement order, though nothing crucial hinges on this.)

A counterpart has been proposed in English to the overt dative case in (8): a covert preposition of possession PHAVE in the English double object construction (Harley 2002, following Pesetsky 1995; cf. also Richards 2001). PHAVE is covert because the English preposition to has lost possessional meaning, this sense of to incorporating obligatorily into be to yield have.5 (Ramchand analyzes to as a path head or a result head.) Harley’s “alternative projection” approach to the double object construction opposes Larson’s (1988) account deriving it from the to-dative structure. For Harley, a verb like give selects different prepositional complements in the to-dative and the double object constructions. In the latter (… give Mary a letter), it selects PHAVE.

Ramchand adapts (9) to her more articulated clause structure: (10) below is her (74), p. 103. The verb give projects the causal subevent init (that perhaps corresponds to v’), and identifies proc and res. The possession PP is not res, but the complement of res. This PP does not have a specifier; the possessor is generated as the specifier of resP. Thus Ramchand adds a layer of structure between the possessor and Phave.

Kayne (2010) suggests that BE rather than HAVE is more likely the silent element in (the French counterpart of) such possessive constructions, because matrix be is left unpronounced in many languages, whereas a silent matrix have is unattested; then the possessor “already has, within the small clause, its dative Case.” If so, the Kannada and the English/French dative-of-possession constructions are completely parallel.

To sum up this section, there is a PP of possession that occurs as a complement to a copula, yielding either the dative of possession, or the verb have. This PP of possession occurs also in the double object construction. I shall argue that yet another occurrence of it is what gives rise to the dative experiencer construction. In the structure I propose in (21), the verb (bar- or aag-) is the head of a proc phrase which takes a dative case possession phrase as its complement. (I revert to Harley’s structure for the possession phrase in preference to Ramchand’s.)

I explore the event structure projected by bar- in the nominative and experiencer dative constructions by teasing out differences between the Kannada verb and its English counterpart in their privileges of occurrence: i.e. the types of subjects and complements each allows. Where the verb meaning in the two languages maps into identical event structure projections, the Kannada sentence translates into English almost literally, modulo word order and case realizations. Kannada locutions that fail to thus converge in English show us the fault lines between these languages in the mapping from verb meaning to syntax.

In its prototypical use as a verb of physical motion with a nominative subject, the Kannada verb bar- corresponds to the English verb come.

We have seen that in Ramchand’s system, English come is a [proc] verb that also projects [init]. In (12), the argument of come is plausibly an initiator. Come is also punctual, incorporating a [res] or result phrase: ‘John will come in a minute/ *for a minute;’ ‘The pizza boy comes in 20 minutes/ *for 20 minutes.’6

A similar characterization is possible of Kannada bar- in (11) as [init, proc, res]. Consider first the [init] feature, Kannada bar- has a morphological causative form bar-is-, which may appear to argue that the causative morpheme realizes [init], and not the verb bar-. However, (11) (which has a nominative subject that is a plausible initiator of the movement) does not in my judgment allow the causativizing morpheme to occur.7

bar- is also punctual: it allows adverbial adjuncts of time headed by -alli ‘in,’ and disallows the bare or the -hottu ‘time’ adjunct that has the durative interpretation:

How should the verb bar- be analyzed in its occurrences in the experiencer dative constructions (15) and (16)? A literal rendering of these examples is that a memory or thought “comes” in (15); in (16), anger, sleep or wisdom “comes” But clearly, none of these can be said to initiate a process of coming. I conclude that bar- in (15–16) must lack an [init] feature.

Where bar- lacks [init], we expect [init] to be independently lexically realizable when projected. Indeed, the causative verb bar-is occurs most naturally in examples corresponding to (16 i–ii):

Insofar as the Kannada examples (15–16) have well-formed English counterparts, an inference that [init] need not always be projected by the English verb come either, seems to be warranted.8 We do not of course expect straightforward correspondences in English for the occurrences of bar- in the experiencer dative construction (henceforth “dative bar-”), since English is known to lack the construction. Yet some instances of dative bar- lend themselves more readily to an English rendering than others. Compare the sets (18–19). (The dative experiencer corresponds to a to-object, and the predicative noun in Kannada to the subject, in English). I judge the English examples in (19) less acceptable than those in (18). The examples in (19) improve when the parenthesized elements are included; these are elements that modify and enhance the process component.

The less acceptable English examples in (19) are more obviously stative than (18). In English, the semantic type of state is encoded by the predicative category Adjective, and the most natural way in English to express the states in (19) is with adjectival predicates, as in the translations of (16): ‘I felt/ got angry;’ ‘I felt/got sleepy;’ ‘I got wise/I became wiser.’ Kannada, we have noted, is impoverished in adjectives, and so relies on nouns to designate states. Now in (18) as against (19), the nouns that are the subjects of come, though not sentient, are individualized and therefore conceivable as entities that undergo a process of coming; it is easier to visualize ‘thinking’ or ‘remembering’ as an event, than ‘sleeping’ or ‘being angry.’ This explains why (19ii–iii) improve when elements that modify the proc projection are included; they foreground the process of “coming.” The process-enhancing elements include, but are not limited to, manner adjuncts in (19ii) (unheralded, unaided by pills), or a time adjunct in (19iii) (late in life). The acceptability of elude relative to come in (19ii) is perhaps because the lexical meaning of elude encodes manner of motion, i.e. avoidance of pursuit. Negation, i.e. the not-coming of sleep, may also play a role: the relative acceptability of Sleep would not come to me as against ?Sleep came to me suggests that the not-coming of sleep is eventive compared to the stativity of sleep “coming” to someone. Conversely, example (19iv) improves if its stativity is enhanced by specifying a locational source for a generic subject: Dreamscome to usfrom the collective unconscious.

In short, dative bar- differs from English come in that it tolerates a weaker proc element. It encodes a state that is the end result of a process. Hence, it more readily allows the semantic type of state in its nominative argument, which denotes the state that the dative argument is in. Dative case here thus signifies simply a relation between two nouns. We know that dative case encodes possession in Kannada. Now it is well-known that the possession relation serves merely to relate two nouns in a somewhat unspecified, or typical, relationship. Thus, the experiencer dative construction is in fact a (dative-of-) possession construction. Indeed, we find that the relation expressed by dative case in the experiencer construction is, in a range of corresponding English examples, expressed by the verb of possession have. We have already seen this in (16iv) (repeated below as (20i): the dream-state conveyed by bar- translates into English as I had this dream, i.e. the dreamer “possesses” the dream. The other examples in the set elaborate this point.

The last example, translated as a double object dative in English, does not have an overt have. But it is of a natural class with possessives, cf. (9-10) above.

We have seen that dative bar- has no [init], and tolerates a weak [proc]. It encodes a state that is the end result of a process. Dative bar- is then like a verb of appearance or existence, with a relational element in the predicate. This relational element is dative case, which designates a possession relation between the experiencer and the experience. I, therefore, represent dative bar- in (21) as a process head that has a result phrase, a small clause. The head of the small clause is dative case, which relates the experiencer (the holder or possessor of a result state) and the experience-denoting noun in the rheme position.9

This structure is akin to the relevant subpart of the English double object structure. Ramchand’s structure for it was illustrated in (10) above. A difference is that I have allowed bar- to underassociate its res feature, with dative case instantiating res. Ramchand has the verb identify both proc and res to show that the result of giving is “cotemporaneous” with the act of giving. (In contrast, in her to-dative construction the verb underassociates and unifies its semantics with to, which heads res.) Since dative bar- does not denote an action or process that brings about the result, but only “presents” the result, I choose not to project the additional layer of structure required if res were not headed by dative case.10 Dative bar- thus underassociates its res feature and unifies its conceptual content with the res head ge, in the manner of the complex predications discussed in Section (2.2). The possessor/experiencer is merged as the specifier of the dative head, as in Harley (2002).

This analysis of dative bar- raises some questions about the representation of stative verbs, including verbs of appearance and existence, and the licensing of result phrases by them. Stative verbs, in Ramchand’s system, have no proc element (op.cit.:55), as proc is “the hallmark of dynamicity” (p. 106). This accords well with our observation that proc is attenuated in dative bar-; but it also militates against this projection for it. What, then, would bar- project in Ramchand’s system, as a stative verb?

For Ramchand, stative verbs “consist simply of an init projection, with rhematic material projected as the complement of init instead of a full processual procP” (p. 55). Thus, Katherine fears nightmares (her example (33)) has the structure (22) (=her (34)), where Katherine is “straightforwardly interpreted as the holder of the state:”

Ramchand concedes that “notating the first-phase syntax of statives as ‘init’ is not strictly necessary, since we could simply assume an independent verbal head corresponding to an autonomous state,” but prefers to “unify the ontology” of stative and dynamic verbs because Burzio’s generalization (that verbs that assign accusative case license an external argument) applies to both.11

The considerations from Burzio’s generalization do not, of course, straightforwardly carry over to the experiencer dative construction. The experience argument in Kannada is never marked accusative.12 Therefore, nothing forces an external argument in this construction. The initiator is a primitive that distinguishes the external argument. It is defined for intransitive unergatives as “an entity whose properties/behavior are responsible for the eventuality coming into existence” (p. 24; e.g. he stank). This definition is indeed appropriate for the nominative subject of bar- in (23a), but not for the dative experiencer in (23b).

For statives, the initiator is claimed to be “the entity whose properties are the cause or grounds for the stative eventuality to obtain” (p. 107). Again, this characterization is more appropriate to the external argument in (23a) (where the decaying subject is giving rise to a stink), than to (23b).

The argument that (22) is not the appropriate representation for all stative verbs can be made purely on the basis of English. The English verb come, like dative bar-, occurs as a verb that presents a result state. Consider first the metaphoric contexts in (24).

Ramchand intends “the abstract structuring principles behind all eventive predications … to cover changes and effects in more subjective domains as well” (op. cit. 54). So come in (24) must be an [init, proc, res] verb. But the information content of (24) resides chiefly in the res part of the predication, as evident in the informational richness of the negation of (24):

Another way of saying this is that in these examples, there is a “rich res, poor proc;” or that come in (24–25) is a light verb.13 Consider now (26):

The infinitive in (26) that denotes a state of belief, knowledge, or understanding, contrasts with the purposive to infinitive in (27).

Correspondingly, in (27) the subject is the initiator of the movement of coming, in (26) it is not. Thus, in the paraphrase (28) of (26b), the subject position of come is not thematic.

I do not claim a one-to-one correspondence between the verbal and nominal complements of come in (26) and (28) (cf. It has come to our notice/attention/*belief/*understanding); the point is that the subject of come, which is clearly not thematic in (28), is arguably not thematic in (26) either. This suggests a raising structure (29) for come in (26):

Now this is very close to the structure suggested in (21) for Kannada bar-: come has a clausal internal argument that encodes a result state, a mental state that the subject is in. The difference is that bar- has a small clause complement, and come an infinitival complement (but cf. (33) below). Infinitival complements to bar- can have only a purposive, eventive reading (thus the Kannada counterpart of (26iii) has the odd reading ‘I have come (somewhere) in order to believe that …’), due to the more general fact that Kannada does not allow subject raising out of infinitive complements.14

We must distinguish the “rich” result postulated in the complement of a light verb come or bar- from the resultative constructions discussed in the literature on unaccusatives, such as the following:

L&RH (p. 34) define a resultative phrase as “an XP that denotes the state achieved by the referent of the NP it is predicated of as a result of the action denoted by the verb …” (emphasis added, RA). The result state in this construction is caused by the predicate: “the state denoted by the resultative XP is part of the core eventuality described in the VP” (p. 49). Resultatives are “expressions in which both the causing event and the change of state are specified, each by a different predicate” (p. 107). In Van Valin’s (1990) system of predicate decompositions, an activity predicate that causes a change of state derives an accomplishment predicate, and the resultative in (30 i–iv) is diagnostic of accomplishments.15

L&RH point out (pp. 55–56) that the resultative as they define it does not occur with verbs of inherently directed motion such as come, go and arrive: (31) does not mean (32).

The nonexistent meaning is clearly an accomplishment reading (i.e. if the activity of arriving resulted in breathlessness, arrive would be an accomplishment verb; compare shout in (30ii) above). L&RH also observe that verbs of existence and appearance, “though cited as bonafide unaccusative verbs, are like unergative verbs in generally lacking causative uses” (p. 81). I.e. we do not have the usages “The magician appeared the rabbit” or “God be-ed the universe.” (Recall that this is why Ramchand analyses these verbs as projecting [init] as well as [proc] and [res].) Again, what is nonexistent is an accomplishment reading.

The claim that verbs of inherently directed motion are incompatible with resultatives is contested by Tortora (1998). I briefly summarize below Tortora’s argument, before turning to its refutation by Higginbotham (1999), who provides an account of the telicity of achievement predicates that supports my analysis of dative bar-.

L&RH attribute (p.58) the putative inability of verbs of inherently directed motion to accommodate resultatives to Tenny’s (1987) claim that “an eventuality may be associated with at most one delimitation.” Since “verbs of inherently directed motion are achievement verbs; they specify an achieved endpoint,” a resultative, which is a delimiter, cannot again occur with these verbs. Tortora points out (however) that

Tortora argues that the ungrammatically of *Willa arrived breathless may be due to a violation of the further specification constraint. Then this example has no bearing on the incompatibility of arrive with resultatives. Verbs like arrive do occur with goal phrases (We arrived at the airport), which are delimiters. Tortora concludes that the goal phrase delimiter meets the “further specification” condition; and that “there does not seem to be a way to straightforwardly maintain that open in [The bottle broke open] is a resultative but at the airport in [We arrived at the airport] is not” (p. 343).

Higginbotham (1999:134) deems this a conclusion “that would be unfortunate if true,” because there are languages (e.g. the Romance languages) that lack resultatives of the break XP open type but have constructions of the type arrive at XP. Kannada is like the Romance languages; it by and large lacks resultatives of accomplishment predicates. The solution Higginbotham proposes is to regard arrive as a predicate applying to (instantaneous) events of being at a place, which constitute the terminus or telos of events of journeying to that place, formally as:

arrive (x, e) 〈-〉 (Ep [at (x, p, e) & (Ee') (e' is a journey by x & (e', e) is a telic pair)

If so, then the adjunct [at the airport in They arrived at the airport, RA] does not express the result of the arrival, but simply identifies the place in question. Furthermore, arrive does not admit a resultative, since it classifies events that are themselves already results. (loc. cit.)

A “telic pair” is a mode of semantic interpretation through composition. A telic predicate “makes some reference to the notion of an end;” it may be “the end of a process given by the predicate itself,” as with accomplishment predicates; or “recovered by implication” for an achievement predicate (Higginbotham op.cit. 132). In the latter case, the predicate presents a situation that has come into existence (recall that achievement predicates are BECOME predicates that take a state as complement).

I have characterized as a weak [proc] what Higginbotham characterizes as an “instantaneous event.” The observation that arrive “classifies events that are themselves already results” is particularly pertinent to my analysis of dative bar- as a verb that presents or encodes a result state. Kannada incidentally does not distinguish arrive from come: both translate as bar-.16 In English as well, come and arrive overlap in meaning. Arrive, like come, can take metaphoric locations as complement (arrive at a conclusion). Come, like arrive, presents the result of metaphorical events located in a PP complement: What has come over him? He came into (a lot of) money. His efforts have come to grief/come to naught), suggesting that like dative bar-, come can take a small clause complement:

A second verb typical of the dative experiencer construction is aag-. I assume that like bar-, aag- projects a weak [proc] and a rich [res] (‘to me fear’) in (34).

Other psychological predicates that occur with aag- are aascarya ‘surprise,’ dukkha ‘sadness,’ gaabari ‘fear,’ santooSHa ‘happiness,’ and yoocane ‘worry.’

Aag- is commonly translated into English as a pair of verbs ‘happen, become.’ The ‘become’ reading is seen in (35).

The ‘happen’ reading is seen in (36).

aag- thus means both come to be (=become), and come to pass (=happen), which I shall analyze as come to be at (=take place). aag- also means come to have, i.e. get:

Consider the examples below. They form minimal pairs with respect to the happen and become readings of aag-. These readings are contingent on a dative argument on the happen reading, and a nominative subject on the become reading.

This alternation is clear evidence that dative case is not a “governed” case, i.e. a semantic case assigned by a particular class of “psychological predicates.” It suggests that the distinction between the dative and nominative case frames for aag- derives from the happen-become distinction that aag- straddles.

This distinction lies in the head of the small clause res complement to aag-. The small clause head is a copula on the become reading, and dative case on the happen reading. When a copula heads the small clause, be “incorporates” into aag-. In Ramchand’s framework, incorporation (head movement) is effected by underassociation of the incorporating element, and remerge. I analyze aag- as projecting both proc and res, informally notating these as ‘come’ for process and ‘be’ for stativity. Let us assume ‘be’ to reflect the minimum or barest possible content, the least encyclopedically rich instance, of the stativity head res. When the result complement of aag- is headed by (the features of) a copula, the semantics of the lexical copula are non-distinct from the features of the res head that aag- identifies. This allows the copula to underassociate in res—to be identified by aag- under Agree, and unify content with it, as required (Ramchand op.cit: 98). In this case, underassociation exhausts the features of the copula, and so it is not spelt out separately as a lexical item. The “subject” (Specifier) of res is now remerged as the “subject” of proc (in its Specifier). This is shown in (42).

We must note that copular sentences in Kannada may have the copula overt or covert (or perhaps absent). What concerns us here is that according to whether it is overt or covert, the category of the complement to the copula varies. When there is an overt be, its complement is adjectival (cf. (43)).17 When the copula is covert, the complement is nominal (cf. (44)).

aag- permits either type of complement. Thus, the rheme in (45) is adjectival and corresponds to (43), and the rheme in (46) is a noun and corresponds to (44).

Thus aag- must have the full range of features that the copula in Kannada has, allowing it to take either nominal or adjectival complements.

The subject of aag- in (42) is remerged into procP, by the under association of the copula and the identification of res by aag-. Hence, it is an UNDERGOER (of a process sub event; it undergoes some sort of identifiable change/transition (Ramchand op.cit: 28)). In Ramchand’s system, INITIATORS and UNDERGOERS both end up as nominative case marked subjects (the former, classical external arguments; the latter, subjects of unaccusative verbs). aag- thus has a nominative subject on the ‘become’ reading.18

The subject of aag- in (42) is perhaps remerged again as high as initP, i.e. aag- in the sense of ‘become’ probably projects all three of [init, proc, res]. The evidence for [init] is that purposive adjuncts may occur with this sense of aag-, as they may with become in English: avanu raajanannu kondu raaja aada, ‘he king- ACC. kill- PST.PPL. king became,’ ‘He became King by killing the King.’

When the small clause head is dative ge-, a happen reading obtains, which corresponds to the eventive reading of English happen as well as the possession reading of English have. Consider first the latter reading. The res phrase here is identified by dative case ge-, which encodes not only a res state, but adds the semantics of possession to it. This is a lexical-encyclopedic content of dative case that we have extensively illustrated. aag- lacks the semantics of possession. So ge-cannot “incorporate” into it. Instead, aag- underassociates its res feature.

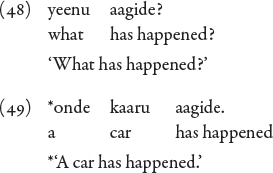

On the ‘happen’ or ‘come to pass’ reading, aag- may surface with a single argument (48), but this argument is required to be eventive (49).

Taken together with (50) where a dative argument surfaces, this suggests that there is indeed a small clause in the complement of aag- in (48), headed by dative case. I take dative case here to encode a location for a result: as to does in English, specifying PLACE as well as res (Ramchand op. cit: 118).19 Informally, we may notate this content of ge- as BE AT.20

The structure I have proposed in (21) for the experiencer dative construction is essentially that of the English double object construction (minus the changes in Ramchand 2008), with the difference that the verb in the experiencer construction does not project an initP. Consider now (51), a canonical ditransitive sentence interpreted as the transitive or causative counterpart of the experiencer dative sentence (52).21

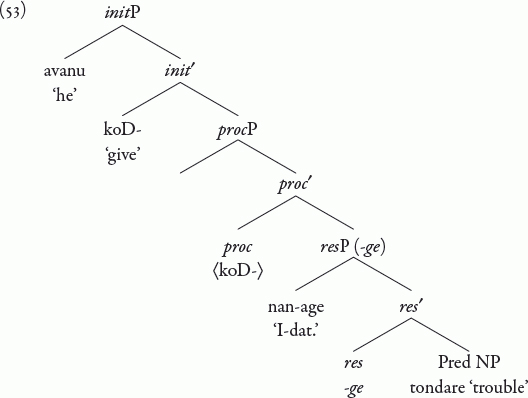

The simple addition of an init projection to the experiencer dative structure gives us the structure for (51). The verb koDu- ‘give’ lexicalizes an init projection in addition to the proc and res projections lexicalized by aag- (47), as shown in (53).

(53) (the structure of (51)) is a double object construction. This suggests that Kannada has a double object construction in addition to, and different from, the standard goal-dative construction in (54).

Up until now, (54) has not been differentiated from (53). There is no difference in the word order. However, while it is possible to mark the direct object with an overt accusative case in (54), it is not possible to so mark the predicative noun in (53). This has so far remained a stipulative observation.22

Up until now (again), the double object construction (51) and the experiencer dative construction (52) have been thought to differ radically, in that (52) is a “dative subject” construction, whereas (51) is a “nominative subject” construction with a dative (indirect) object. On my analysis, (51) and (52) differ only in the init projection, which is lexicalized by the Kannada verb ‘give’ but not by ‘happen.’ Such a relation between English give in its double object occurrence, and get/take, is supported by the classical argument of shared idioms (Richards 2001). The idioms The Count gives everyone the creeps, You get the creeps (just looking at him) suggest a component have the creeps common to both these occurrences. This in turn argues for the Harleyan double object structure with its sub lexical preposition of possession (notated as HAVE), that occurs also in the complement of unaccusative get: [vPThe Count [v’.CAUSE [PP everyone HAVE the creeps]]], [vP You [v’ BECOME [PPHAVE the creeps]]].

Richards does not mention the possibility of a pleonastic subject for this idiom in the double object construction: It gives me the creeps (when he does that/ to think that …) (= I get/ have the creeps when …).23 This example (and others like it, e.g. It gives me great pleasure to…) suggest that in English as in Kannada, the double object construction does not necessarily project an initP. Then the structures for The Count gives me the creeps and It gives me the creeps … are related precisely as the structures for koD- and aag- are in (51–52), modulo the requirement of a pleonastic subject for the latter in English: [initP The Count [init’give [procP [proc’ 〈give〉 [resP me HAVE the creeps]]]]], [procPe [proc’ give [resP me HAVE the creeps]]].

The argument in the preceding sections identifies the dative experiencer construction with the sub component of the double object construction that depicts a res complement to a proc head. If so, in the event structure projected by bar- or aag-, the dative experiencer is a RESULTEE argument. Experiencer objects of eventive verbs like depress (The weather depressed John) are also RESULTEES (Ramchand 2008:54), as are possessors in the double object construction. The RESULTEE position in event structure is plausibly thus the canonical position for experiencers/possessors.

I analyze the dative experiencer as a RESULTEE but not an UNDERGOER, even as Ramchand does the goal or possessor in the double object construction (op. cit.: 103–4). The RESULTEE is the holder of a result state. The experiencer dative and the double object dative both hold the state of possession. But neither appears to “undergo” the process designated by the verb (the experiencer does not undergo the process of bar-, i.e. ‘coming,’ or aag-, i.e. ‘happening;’ and in (10) above, Alex gave Ariel the ball, Ariel does not undergo the process of ‘giving’).

To add to the argument that the dative experiencer is a RESULTEE, and not an UNDERGOER, recall that when aag- takes a copular complement, its subject is remerged at least as high as in the specifier of the proc head, if not the init head; i.e. it is either an UNDERGOER or an INITIATOR. This subject is nominative. When the small clause has a dative of possession head, a dative marked NP is the most prominent argument. Nothing suggests that this argument has a role other than RESULTEE, and it surfaces with dative case.

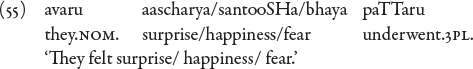

This correlation between nominative case and an event structure position higher than RESULTEE is seen again in the following data. Some predicate nouns that occur with aag- occur also in a nominative experiencer construction with the verb paD- ‘experience, undergo:’

The verb paD- has a causative form paD-is, arguing that it allows an initiator to be projected. Thus aascharya paD-isu ‘surprise’ (transitive) (‘surprise caus-undergo’) has an initiator that causes the state, and therefore, an undergoer that receives the process of causation as well as experiences the resultant state. No such roles are available for aag-, which no causative form *aag-is. Modals arguably related to the proc subcomponent occur with paD- but not with aag-: kaSHTa paD beeku ‘One should take trouble (lit. should undergo difficulties),’ *kaSHTa aag beeku *‘Difficulties should happen.’ All this suggests that RESULTEE arguments that are not remerged in higher event projections surface with dative case in Kannada.

What are the consequences of these claims for case marking, and the subject-like properties of the dative experiencer (to address a reviewer’s concern)? The arguments distinguishing the dative object from the dative experiencer that impute subject-like properties to the latter are well-known: e.g. control of a null participial subject, or control of anaphora. On the other hand, its very case marking argues that the dative experiencer is not in the “subject position,” if that designates a nominative case-marking position in the syntax. Now a property of the double object construction is that the goal argument c-commands the theme argument. This suggests that the subject-like properties of the dative experiencer may derive from it being the most prominent argument in the clause, which c-commands all other arguments.24

Coming to case marking, Ramchand assumes that the inflectional head is responsible for nominative, and init for internal structural case (p. 62); and that all three sub event “subjects” must be licensed by these two cases. Thus (she points out) in her descriptions of English verb types, the specifiers of init, proc and res are not all three ever full, for Case reasons (loc. cit.).

In both the English double object structure (10) and the dative experiencer structure (21), the specifier of proc is empty. What is the case of the RESULTEE? In English, it is standardly assumed to receive accusative case, which is plausible if init is projected. We, have, however noted the possibility of an expletive subject in this construction—i.e. init may not be projected. If so, the RESULTEE case may in fact be dative (cf. Kayne’s (2010) suggestion cited in Section 2.3). This would be as in Kannada, where (I suggest) the RESULTEE retains the dative case it receives within its small clause. In the Kannada experiencer dative structure (21), the external argument (the specifier of proc) may be an expletive pro (Jayaseelan 1990), or it may not be projected at all (perhaps a structural reflex of Kannada tolerating a weak proc). The predicate noun controls verb agreement. Early analyses, therefore, assumed it to be a subject, in addition to the dative “subject.” I suggest that agreement in this construction is an instance of “inverse” agreement with a predicate when the subject is empty, as in existential there-constructions in English.

I have argued that experiencer datives in Kannada are RESULTEE arguments of verbs that project a weak or poor process and a rich result. This implies that there are stative verbs (achievements) that merely present a result state, in a kind of resultative construction noticed in Higginbotham (1999). My analysis of the dative experiencer construction assimilates it to the possession subpart of the double object construction, limiting it neither to “psych” verbs nor to South Asian languages. English lacks the dative experiencer/possessor construction because it does not tolerate weak or poor process verbs. Kannada must do so, as it is impoverished in adjectives, and nouns in this language designate states that are “in the possession of” experiencers. A second difference between these languages is in the signaling of possession with the verb have or dative case. Finally, RESULTEE arguments that are the sole “subject” argument in the first phase surface with inherent dative case in Kannada.

1. I thank Rahul Balusu, Shruti Sircar and K. A. Jayaseelan for helpful discussion, and two anonymous referees for useful comments.

2. Intransitive break projects [proc] and [res]. The two “subjects,” UNDERGOER and RESULTEE, share a subscript to mark their identity. The causative counterpart of break projects [init].

3. The possessor must be inanimate, and the possession non-referential, in this construction in English: *There are ears to the dog, *This is the lid to this.

4. Kayne builds on Szabolcsi’s (1983) analysis of the Hungarian possessive construction, where John has a sister surfaces as To John is a sister. This construction originates with a copula (van in Hungarian) taking a single DP complement containing the possessor DP, to the right of and below D0:

The possessor may move to the left of the D head and surface as dative; it can then move out of the larger DP entirely, retaining dative case. (If the larger DP is definite, the possessor can also remain in situ and be marked nominative.)

For an account of the optional “to it” in (6a), cf. A&J p. 64, n. 1.

5. When not merged into the clausal functional architecture, to expresses possession, cf. the fragments in birth announcements To John, a sister; sister to John. She is a sister to me patterns with the examples in (6) above: to forces a non-referential reading for a sister, signaling the absence of a real relation.

6. These for-phrases can occur with the meanings ‘John will stay for a short while,’ or ‘the pizza boy habitually hangs around for 20 minutes’ (as a reviewer points out). The paraphrases indicate that what is modified is not the process of coming (‘the pizza boy’s coming will last for 20 minutes’), but its result (the “staying” or “hanging around”); strengthening the claim that come is punctual.

7. A magical situation, where movement could be externally induced, is imaginable with the causative bar-is. We may treat this as an instance of the “underassociation” of the causative feature of bar- when it is embedded under a causative morpheme (Ramchand op. cit:172 ff., 181).

8. If bring in English is ‘cause to come’ (John brought his new girlfriend to the party), come does not inevitably lexicalize [init]. (L&RH report a suggestion in Chierchia (1989) to this effect.)

9. The rheme is characterized as the object of a stative verb, where there is “no dynamicity/process/ change involved in the predication” (Ramchand op. cit: 33), only a “predicational asymmetry.” The rheme is part of the description of the state predicated of the subject.

10. That dative case can head res, even as to can, is suggested by the dative adjunct below, interpreted as a result. Compare the Kannada with its literal English translation: ‘To our misfortune, they happened to see us.’

11. It is not obvious that be in English (e.g.) has an “object” with accusative case. As Ramchand notes (p. 34), DP objects of stative verbs are ‘Rhematic Objects’ that are part of the description of the predicate, and RHEMES can be PPs and APs as well as DPs.

12. Mahajan (2004:286) in fact argues that “constructions is which (the) non-nominative subjects appear (in Hindi, RA) lack a source for accusative case.” Tamil, however, is claimed to allow accusative case in the dative experiencer construction.

13. In adjuncts, i.e. in the absence of the first phase functional projections, come merely presents a state or event.

i. Come September, the clouds will be here. (=when it is September, …)

ii. Come what may, you must contest the election. (=Whatever happens, …)

iii. How come you’re here? (= how does it happen/ how has it come about that …)

Come also occurs with presentational there (There comes a time when …).

14. E.g. to seem or appear:

On the other hand, (28) corresponds word for word to the Kannada (ii), except that Kannada lacks expletive it; and a non-clausal subject can occur in this structure in both English and Kannada (iii):

In (ii–iii) the dative NP is not an experiencer. Dative case has here the semantics of English to, specifying a res and a location (cf. Section (5)). As in (6) above, English allows parallels to Kannada in the absence of the semantics of possession.

15. Clause (d) of Van Valin’s (1990) system of predicate decompositions (from L&RH p. 167) derives an accomplishment predicate from an achievement predicate, via an activity that causes the achievement.

a. STATE: predicate’ (x) or (x, y)

b. ACHIEVEMENT: BECOME predicate’ (x) or (x, y)

c. ACTIVITY (± Agentive): (DO (x)) [predicate’ (x) or (x, y)]

d. ACCOMPLISHMENT:ϕ CAUSE ψ, where ϕ is normally an activity predicate and ψ an achievement predicate

16. A serial verb bandu-seeru (lit. ‘come-join’) can specifically signify arrive, but also “to join a group.” The claim that verbs that classify “events that are themselves already results” do not admit resultatives may need to be thought out further, given the causativization of stative datives in (17) above.

17. Here, a dative case-marked noun. Dative case derives A (Adj./Adv.) from N in Kannada; cf. Amritavalli and Jayaseelan (2003).

18. English become may also be decomposed as the “incorporation” of be into a weak process verb come, although become is taken to be a primitive in the predicate decomposition of achievement verbs in the tradition of Dowty 1979; Van Valin 1990 and Vendler 1957 [1967].

19. For Ramchand, to “has a res feature in addition to its specification for PLACE” (p. 118). The place head may be filled with in and on; underassociation of to’s place feature yields into and onto.

20. Dative case can indicate a point of time: ondu gaNTe-ge, ‘at one o’clock.’ The res of aag- may covertly signify the temporal location of an event (AT OVER/AT NOW, identified by the tense of the verb), cf.

21. As Shibatani (1999:54) notes, “many languages provide transitive and intransitive pairs” (canonical transitive counterparts to the dative experiencer construction).

22. This NP, being non-referential, must remain indefinite and non-specific (Jayaseelan 2004:240).

23. My thanks to a reviewer for drawing my attention to Richards’ squib in the context of this example.

24. That the dative experiencer does not occupy the canonical subject position but is a scrambled non-subject argument is argued in Jayaseelan (1990). The possibility of naanu meeri-geiavaLanneitooriside ‘I Mary-dat. herself showed’ ‘I showed Mary herself,’ in contrast to *naanu avaLanneimeeri-geitooriside, argues that a dative argument on the left c-commands the accusative to its right.

References

Amritavalli, Raghavachari & Jayaseelan, Karattuparambil A. 2003. The genesis of syntactic categories and parametric variation. In Generative Grammar in a Broader Perspective: Proceedings of the 4th GLOW in Asia 2003, Hang-Jin Yoon (ed.), 19–41. Hankook: KGGC and Seoul National University.

Bhaskararao, Peri & Subbarao, Karumuri Venkat (eds). 2004. Non-nominative Subjects, vol. 1 [Typological Studies in Language 60]. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Chierchia, Gennaro. 1989. A Semantics for Unaccusatives and its Syntactic Consequences. Ms., Cornell University.

Chomsky, Noam. 1995. The Minimalist Program. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Dowty, David. 1979. Word Meaning and Montague Grammar. Dordrecht: Reidel.

Freeze, Ray. 1992. Existentials and other locatives. Language 68: 553–595.

Hale, Ken & Keyser, Samuel J. 1993. On argument structure and the lexical expression of syntactic relations. In The View from Building 20: Essays in Honor of Sylvain Bromberger, K. Hale & S. J. Keyser (eds), 53–109. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Harley, Heidi. 2002. Possession and the double object construction. Yearbook of Linguistic Variation 2: 29–68.

Higginbotham, James. 1999. Accomplishments. In Proceedings of the Nanzan GLOW, the Second GLOW Meeting in Asia, Mamoru Saito et al. (eds), 131–139. Nanzan University: Nagoya, Japan.

Jayaseelan, Karattuparambil A. 1990. The dative subject construction and the pro-drop parameter. In Experiencer Subjects in South Asian Languages, M. K. Verma & K. P. Mohanan (eds), 269–283. Stanford: CSLI.

Jayaseelan, Karattuparambil A. 2004. The possessor-experiencer dative in Malayalam. In Non-nominative Subjects, vol. 1, P. Bhaskararao & K. V. Subbarao (eds), 227–244. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Kayne, Richard. 1994. The Antisymmetry of Syntax. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Kayne, Richard. 2000. Toward a modular theory of auxiliary selection. In Parameters and Universal, R. Kayne (ed.), 107–130. New York: Oxford University Press, and Studia Linguistica [1993]. 47: 3–31.

Kayne, Richard, 2010. The DP-internal origin of Datives. Paper at the 4th European Dialect Syntax Workshop in Donostia/San Sebastian.

Klaiman, Miriam. 1986. Semantic parameters and the South Asian linguistic area. In South Asian Languages: Structure, Convergence and Diglossia, Bh. Krishnamurthy, C. P. Masica & A. K. Sinha (eds), 179–194. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass.

Kratzer, Angelika. 1996. Severing the external argument from the verb. In Phrase Structure and the Lexicon, J. Rooryck & L. Zaring (eds), 109–137. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Larson, Richard. 1988. On the double object construction. Linguistic Inquiry 19(3): 335–391.

Levin, Beth & Rappoport-Hovav, Malka. 1995. Unaccusativity: At the Syntax-Lexical Semantics Interface. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Mahajan, Anoop. 2004. On the origin of non-nominative subjects. In Non-nominative Subjects, vol. 1, P. Bhaskararao & K. V. Subbarao (eds), 283–299. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Pesetsky, David. 1995. Zero Syntax: Experiencers and Cascades. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Ramchand, Gillian. 2008. Verb Meaning and the Lexicon: A First-phase Syntax. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Richards, Norvin. 2001. An idiomatic argument for lexical decomposition. Linguistic Inquiry 32(1): 183–192.

Shibatani, Masayoshi. 1999. Dative subject constructions twenty-two years later. Studies in the Linguistic Sciences 29(2): 45–76.

Szabolcsi, Anna. 1983. The possessor that ran away from home. The Linguistic Review 3: 89–102.

Tenny, Carol. 1987. Grammaticalizing Aspect and Affectedness. Doctoral dissertation, MIT.

Tortora, C.M. 1998. Verbs of inherently directed motion are compatible with resultative phrases. Linguistic Inquiry 29(2): 338–345.

Van Valin, R. D. 1990. Semantic parameters of split intransitivity. Language 66: 221–260.

Vendler, Zeno. 1957/1967. Verbs and times. In Linguistics in Philosophy, Z. Vendler, 97–121. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Verma, Manindra K. & Mohanan, Karuvannur P. 1990. Experiencer Subjects in South Asian Languages. Stanford: CSLI.