R. Amritavalli

0. This paper presents an analysis of anaphora in Kannada (and more generally, Dravidian). In Section 1, I show that there is a process in Kannada which anaphorizes pronouns. In the following sections, I show that anaphors in Kannada and English have a bipartite structure. I argue that of the two parts, only one is an anaphor; the other is simply a pronoun. I further argue that the ‘anaphoric part’ itself owes its status (as an anaphor) to the anaphorization process, which I identify with the filling in of values for an abstract agreement matrix AG. I conclude that there is no feature [+ anaphor], and that there are no ‘intrinsic’ or ‘lexical’ anaphors in languages.

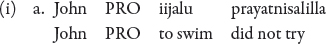

1. Sentences (1 a-c) show that the pronouns naanu ‘I’, niinu ‘you’ and avanu ‘he’ in Kannada obey disjoint reference in the minimal S. (I indicate coreference by underlining.)

Sentence (2) shows that the pronoun taanu ‘self’ also obeys Disjoint Reference.1 It contrasts with (3), where the reciprocal obbaranna obbaru ‘each other-acc’ can and must be bound within the minimal S.

Consider now sentences (4 a-c), corresponding to (1 a-c). Here, the verb carries a marker koLLu. With a verb thus marked, the pronouns in (1) ‘become’ anaphors: they now can and must be bound in the minimal S.

Sentence (5) corresponds to (2) above. It shows that if the verb is marked with koLLu, taanu too can and must be bound in the minimal S.

These data show that

i) the Kannada reciprocal is bound within the minimal S, the domain where pronouns are (ordinarily) free.

ii) koLLu ‘anaphorizes’ pronouns in some way, exempting them from the requirement of Disjoint Reference.

We shall now investigate the process of anaphorization, and show that it is a very general process in languages.

2. It is instructive to begin our inquiry into anaphorization with a preliminary examination of the Kannada reciprocal. The Kannada reciprocal consists of two parts:

I shall refer to these occurrences of obbaru as obbaru1 and obbaru2. The case marker of obbaru1 is appropriate to the position of the reciprocal in the sentence. The case marker of obbaru2 agrees with the case of the reciprocal’s antecedent.

I will argue that it is this process of agreement between obbaru2 and an NP, which anaphorizes the indefinite pronoun obbaru ‘someone’. To substantiate this claim, I briefly examine data from anaphors in English. I show that the English reflexives and the English reciprocals also have a bipartite structure, and that they undergo an agreement process (as in Kannada), which anaphorizes these expressions.

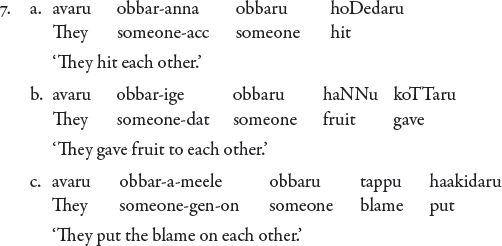

Let us first illustrate the structure of the Kannada reciprocal. The presence of a case marker on obbaru1 is obvious: cf. (7).

In (7 a, b), obbaru1 is case marked accusative or dative, according to its function as direct object or indirect object. In (7c), it is the object of the postposition meele ‘on’. (This postposition requires the genitive case on its object.)

The presence of a case marker on obbaru2 is not obvious in (7). This is because this case marker agrees with the case of the antecedent, and the antecedent in (7) is nominative, with a ø case marker. Compare (8), where the antecedent is case marked dative. obbaru2 now carries a dative case marker.3

Notice that the two parts of the reciprocal need not be contiguous on the surface. In (7c) and (8), the postpositions meele and kanDre intervene. When the reciprocal occurs as a possessive, its parts may be separated by the head noun with its case (and postposition, if any).

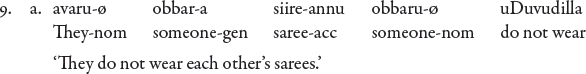

Compare (9):

That non-contiguous items may function together as a reciprocal expression is evident from English. Compare each … other in (10):

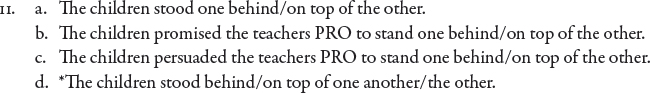

In the case of each … other, an alternative construction with each contiguous with the other is possible (They hit each other). There are, however, anaphors in English whose constituents can never appear contiguous on the surface. Consider one … the other in (11):

That one … the other is an anaphor is shown by (11b, c). It must be bound within the minimal S, to PRO. Thus in (11b), where PRO is controlled by the children, one … the other refers only to the children: in (11c), where PRO is controlled by the teachers, it refers only to the teachers. (11d) shows that one … the other cannot appear contiguous on the surface.

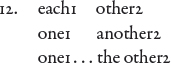

Suppose, then, we think of the anaphoric expressions each other, one another, and one … the other as bipartite, as in the Kannada case:

Notice now that of the two parts of an anaphoric expression like each other, the second part, viz. the other(s), is not in itself an anaphor. This is clear from (13):

These are typical cases of the Tensed-S condition and the Specified Subject Condition respectively. The phrase the others is here free in its governing category; yet the sentences are grammatical. They contrast with (14):

Thus while the other(s) is not an anaphor, each other is.

This fact becomes significant in light of the following; it has been argued that ‘floated’ or displaced quantifiers are anaphors. Jaeggli (1980) shows that the relation between a ‘floated’ quantifier and the element it modifies, is sensitive to Opacity, in Italian, Spanish, French and English. (The suggestion that ‘floated’ Qs are anaphors is originally credited to Belleti (1979).) Consider the following data pertaining to ‘floated’ all (from Jaeggli (1980)):

(15 a) is a case of quantifier ‘floated’ in the same S as its antecedent. (15 b) is grammatical because it contains a PRO, controlled by the kids, which can serve as the quantifier’s antecedent. (15 c) is ungrammatical because all is free in the minimal S; PRO is controlled by John, a singular NP, and therefore cannot serve as the antecedent of all. (15 d) is ungrammatical because all is in a tensed sentence which does not contain its antecedent; it violates both the Tensed-S Condition and the Specified Subject Condition.

The reader can easily verify that each behaves in the same way. We therefore conclude that ‘floated’ Qs are anaphors; in particular, that ‘floated’ each is an anaphor.

Recapitulating,

i) the other(s) is not an anaphor

ii) ‘floated’ each is an anaphor

iii) each other is an anaphor.

Now, if we consider each in each other to be a ‘floated’ Q (as seems reasonable), the anaphoricity of each other can be attributed to the anaphoricity of each. In other words, each anaphorizes the expression each other. The data from English thus support the postulation of a process of anaphorization of pronouns, and the anaphorization of Kannada pronouns by koLLu begins to look more tractable.

3. Given that there is a process of anaphorization, what is the scope of this process? That is, do we need both a process which creates anaphors, and a feature [± anaphoric]—in other words, is there a class of “intrinsic” or “lexical” anaphors? I will now argue in favour of the following strong claim: there is only a process of anaphorization. There are no “intrinsic” or “lexical” anaphors.

We may begin by asking why it is that a displaced or ‘floated’ Q is an anaphor. In an interesting speculation, Jaeggli (1980) suggests that displaced Qs are anaphors because they contain an agreement element AG, and that it is AG which is in fact the anaphor. I quote his proposal in full:

There is nothing inherent in displaced quantifiers which would easily warrant their anaphoricity, at least at first sight. Upon closer inspection of the Romance examples, however, we find one feature of these constructions which might provide a clue. Recall that the displaced quantifier must agree in number and gender with the NP which it modifies. We might speculate that it is this agreement process which is in fact responsible for the anaphor status of these elements. More generally, suppose we assume that all elements which enter into agreement relations with another major constituent contain an anaphoric AG element = α person, β gender, γ number. This element must find an antecedent which is nondistinct to it in those features. This relation obeys all the conditions normally found to hold between antecedents and anaphors. It might be, then, that displaced quantifiers are anaphors because they contain AG, which is an anaphor.

(Jaeggli 1980)

Jaeggli here appears to envisage an “intrinsic” anaphor AG, which anaphorizes ‘floated’ each, which in turn (as we have seen) anaphorizes each other. At a first glance, the data from Kannada and Malayalam seem to support Jaeggli’s proposal. A quantifier in Kannada or Malayalam starts agreeing with its head noun only when it ‘moves’ to the right of the noun (i.e. when it ‘floats’). Compare the (a) and (b) pairs in the sentences below. In the (b) sentences, the quantifier shows number and gender agreement.

(Kannada)

(Malayalam)

These data appear to support the idea that ‘floated’ quantifiers contain AG, “which is an anaphor.” There is a problem, however. How do we analyze the non-‘floated’ quantifiers in the (a) sentences above? If they contain AG, and AG is an intrinsic anaphor, then they too must be anaphors. But there is no evidence that quantifiers in this position are anaphors. The alternative is to posit two sets of quantifiers, with and without AG, which seems counterintuitive.

The solution to this problem lies in a clearer elucidation of the proposal that AG is an anaphor. What kind of an element is AG ? It is clearly not a lexical item which can be lexically specified as an anaphor. AG is a label for a schematic complex of unspecified features whose values must be filled in by a rule that refers to some NP in the sentence. I propose that it is this filling in of its schematic feature complex that anaphorizes AG. It seems to me that this is Jaeggli’s crucial insight: that it is a process like agreement, the application of a rule that specifies feature values by ‘copying’ the values of some other NP, that causes the anaphorization of AG.

A corollary of this proposal is that if the feature values of the AG matrix are not filled in with reference to the feature values of some NP in the sentence (that is, if the agreement process is blocked for some reason), AG is not an anaphor. This would appear to be a desirable result. There are two subcases to consider: (i) where the feature values of AG are left unspecified; (ii) where the feature values of AG are specified, but not with reference to the values of some NP in the sentence.

Let us consider the second subcase first. The intuitive sense in speaking of AG as an ‘anaphor’ is that agreement generally operates within the clause, linking two elements. A verb, for example, generally agrees with ‘its’ subject, or ‘its’ subject and object, and so on. We can think of AG here as ‘bound’ to the subject, or the subject and object. Consider now the case where a verb does not agree with anything in the sentence. This happens, for instance, in Hindi. In Hindi, the verb normally agrees with an NP which has a ø case marker, whether subject or object. (Thus in the ‘ergative’ construction, the verb agrees with a ø case-marked object.) Now if both subject and object are overtly case-marked, there is nothing for the verb to agree with. In such an event, the verb surfaces in the ‘unmarked’ third person singular form:

In (20), the values of the feature complex [AG +3rd pers., + masc., + Sg.] have not been specified by ‘copying’ the values for any NP in the sentence. AG here does not agree with (‘is not bound to’) anything in the clause; it is free. In our terms, AG is not an anaphor in (20). But if AG were intrinsically an anaphor, this sentence should be starred, since AG has no antecedent.

Returning to the data in (16-19), we see that the (a) sentences illustrate the first subcase. The feature values for AG are here left blank. We can show that in general, there is no agreement in Kannada between a quantifier in determiner position and the head noun. Consider the following data. Kannada has a quantifier ondu ‘one’, which is specified [+ neuter]. In determiner position, ondu can occur both with nouns which are + neuter and with nouns which are [− neuter] (i.e. nouns requiring masculine or feminine agreement).

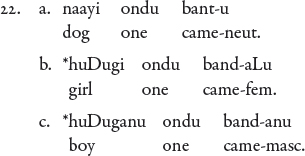

When the quantifier is to the right of the noun, however, a [+ neuter] quantifier cannot cooccur with a masculine or femine noun. Thus (22 a) is grammatical, (22 b, c) are not:

In (22 b, c), only the [-neut.] quantifier obba is possible, which (in this position) also shows number and gender agreement (cf. egs. (16-17) above).

In the (a) sentences of (16-19), then, AG (under our proposal) is not an anaphor. In the (b) sentences, it is anaphorized, as its values are specified with reference to the head noun. This achieves the result that only ‘floated’ quantifiers are anaphors, even though AG is present in the feature matrix of a quantifier in ‘floated’ as well as non-‘floated’ position.

The proposal concerning ‘floated’ each can be fleshed out in the same way. Each contains an abstract, unspecified AG matrix; in this state, it is not an anaphor. When each ‘floats’, it acquires values for the AG matrix by a rule which refers to the feature matrix of the head noun. Each is thus anaphorized when ‘floated’.

We can similarly account for the anaphoricity of NP trace. Let us say that a moved NP leaves behind an abstract, empty feature matrix, which must be filled in by referring to the feature of the moved NP.

The cases of ‘bound anaphora’ noted by Helke also fall into this pattern. We observe that the underlined possessive pronouns below must always agree with their subjects:

We can analyze the verbs in these expressions as sub-categorizing objects, which are themselves subcategorized for a possessive NP position. This possessive NP position has AG, with unspecified features:

The features of AG are filled in, in the familiar way. This anaphorizes AG, which anaphorizes the pronoun, and, ultimately, the NP containing the pronoun.

The English reflexive (as noted by Helke) is a subcase of ‘bound anaphora’. The peculiarity of the noun self in English is that it obligatorily subcategorizes a possessive NP position with unspecified features. Thus while in the word formation component we get a ‘bare’ self (self-help, self-confidence, selfish), neither the ‘bare’ self nor a Determiner-self sequence surfaces in the syntax. We thus give self the lexical entry (25), requiring the AG matrix to be filled in, in the usual way.

Thus while the noun self is just a noun, the NP X self becomes an anaphor.

To sum up this section, I have argued that there is no feature [+ anaphor], and there are no ‘intrinsic’ or ‘lexical’ anaphors in languages. Anaphors are created by a rule which specifies the values of a schematic AG (agreement) matrix by ‘copying’ or ‘floating’ out the corresponding values from another NP in the sentence. I have shown that traditionally recognized anaphoric expressions such as reflexives and reciprocals have a bipartite structure: a non-anaphoric part which is just a (pro)noun, and an anaphoric part which contains AG, which gets anaphorized.

A consequence of this approach is the delinking of the notion of reference from the notion ‘anaphor’, We cannot maintain (for example) that each other ‘has no intrinsic reference’, for in contexts where each has not been ‘floated’ into the NP containing the other, the latter is simply a pronoun, which has reference. Similarly, obbaru1 ‘someone’ in the Kannada reciprocal obbaru1 c.m. obbaru2 c.m. is an indefinite pronoun, which has reference.

In the next section we turn to a more detailed examination of the anaphorization process in Dravidian, and substantiate our claim that Dravidian taan(u) ‘self’ is not an anaphor. We show that taan(u) is, in itself, no more an anaphor than the English noun self is.

4. We have already mentioned the two major instances of anaphorization in Dravidian: anaphorization by case-agreement, and (the apparently somewhat different type of) koLLu-anaphorization. The former process is illustrated in the Kannada reciprocal. Recall that obbaru2 agrees in case with that of the antecedent (cf. egs. (8a, b) above). We can think of obbaru2 as containing an AG matrix [αcase], which has to be specified by rule. The latter process (i.e. koLLu-anaphorisation) is illustrated by data from the reflexivization of taanu and the personal pronouns.

In this section I give an account of koLLu-anaphorization, and assimilate it into our analysis of anaphorization as an agreement process. Before I do so, I wish to illustrate a case where taanu (and the personal pronouns) are obviously anaphorized by agreement, specifically, by agreement of case. This occurs in a construction where the verb cannot be marked with koLLu. The construction in question is the ‘Dative Subject’ construction,4 of which (26) is an illustration.

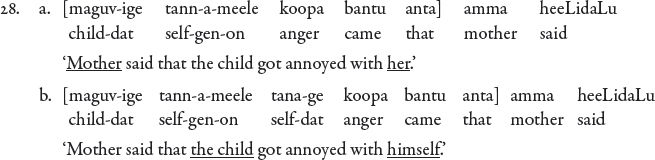

Consider now a variant of (26) where instead of Murti, we have taanu, and we embed this sentence under Gopal heeLidanu ‘Gopal said’. We have the two subcases (27a) and (27b):

Observe that taanu in (27a) behaves like a pronoun, in (27b), like an anaphor. Observe also that in (27b), there is a reduplicated form of taanu which is case-marked dative : i.e., the case of the second taanu agrees with the case of the antecedent, Mohan. There is no reduplicated taanu in (27a).

The data above are exactly parallel to the case of the reciprocal obbaru1 c.m. - obbaru2-c.m. The non-reduplicated form obbaru is an indefinite pronoun ‘someone’: cf. (29a) below. A reduplicated form of this pronoun, with the second pronoun agreeing in case with the antecedent, is an anaphor: cf. (29b):

Evidently, there is a range of cases for which the structure of the Kannada reflexive is entirely parallel with the structure of the Kannada reciprocal:

It should now be clear that taanu and obbaru are pronouns. They both undergo anaphorization by (reduplication and) agreement. In the case of obbaru, this is the only applicable anaphorization process, whether or not the verb can be marked with koLLu.5 In the case of taanu (and the personal pronouns), anaphorization by reduplication and agreement applies only where koLLu-anaphorization is not possible. Thus, a ‘reduplicated’ taanu with case-agreement does not save sentence (31), with no koLLu on the verb, from Disjoint Reference:

At this point, it is appropriate to briefly consider anaphorization in Malayalam. We can show that the structure of the Malayalam reflexive is essentially the structure of the Kannada reciprocal and the Kannada reflexive given in (30) above.

As Mohanan (1981) notes, a ‘bare’ taan in Malayalam obeys Disjoint Reference.

Corresponding to (32a), we have (32b), where there is what looks like a reduplicated taan. taan here behaves like an anaphor: it must be bound in the minimal S.

The same paradigm is illustrated in the sentences below.

What we see in these data is that there are two pronoun positions, Pronoun1 tanne 2 or tanne 1 - tanne 2. The first is occupied by a pronoun whose case marker is appropriate to its position in the sentence; the second, by an invariant tanne2. This tannei 2 does not show overt agreement with the case of the antecedent. Let us say, however, that tanne2 does have an abstract AG matrix [α case], which must be filled in by rule. Our analysis of Malayalam tanne is thus parallel to our analysis of English each. Each, we said, contains an abstract AG, although it shows no overt agreement. Observe that Malayalam, like English, is a language with very little overt agreement (Malayalam has no subject-verb agreement, for example).

We now proceed to give an account of koLLu anaphorization. koLLu has many functions in Kannada, not all of which are relevant to our study of anaphora.6 What is interesting for us is that koLLu functions as a detransitivizer. Consider the following data:

Notice that the (b) sentences have one argument less than the (a) sentences. The relation exhibited by the pairs above is typical of the transitive-intransitive verb relationship.7

The detransitivizing function of koLLu is attested in another construction which I shall call the ‘Dative of Possession.’ Typically, in cases of inalienable possession, the possessor in this construction appears as a dative NP, the possessed item as an accusative. Sentence (39a) is an illustration.

Now if the Dative NP is coreferential with the subject NP (i.e. if the mother washes her own hands), we get (39b), where the verb is marked with koLLu, and the Dative NP does not surface.

This suggests the following analysis: let us treat koLLu as a detransitive/reflexive clitic. Let us say that this clitic is subcategorized for a pronoun position which contains the agreement matrix AG, which must be specified by rule.

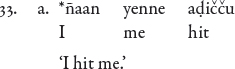

The claim is that in a Kannada sentence like naanu nannannu hoDedukoNDe ‘I hit myself’, the accusative pronoun nannannu is the realization of a feature matrix which is ‘copied’ from the matrix of the subject, just as in the English translation, my in myself is a ‘copy’ of the subject. The difference in the Kannada case is that on the surface, koLLuand the ‘copied’ pronoun are not contiguous. We claim, however, that koLLu and the ‘copied’ pronoun are contiguous underlyingly, and that the surface discontinuity is the result of a rule which cliticizes koLLu on to the verb. We can thus assimilate what we have informally been referring to as “koLLu-anaphorization” into our analysis of anaphorization as a process of agreement.

I have not dealt explicitly with Tamil data in this paper. Tamil reflexives and reciprocals are essentially parallel to those in Kannada. The reciprocal has the form ottar1 ‘someone’-c.m.-ottar2-c.m. with the second case marker agreeing with the case of the antecedent. Tamil also has a koLLu marker on the verb. As in Kannada, this marker cannot appear in the ‘Dative Subject’ construction; taan is here reduplicated, with case agreement.8

5. This concludes our examination of anaphorization in Dravidian. I have argued that anaphors in Dravidian have invariably a bipartite structure, of which one part is an anaphor, the other a pronoun. I have extrapolated this structure to English anaphors.

I have endeavoured to show that the anaphoric part of the bipartite structure (whether in English or Dravidian) contains an agreement clement AG. AG, to begin with, is only an abstract matrix of features with unspecified values; it is not an anaphor in this state. AG is ‘anaphorized’ by the rule which ‘copies’ in the values of its features from an NP antecedent in the setence. Where there is a failure of agreement, there is no anaphorization.

The conclusion we draw is that there is no element which can be said to be inherently (or lexically) an anaphor. A corollary is that there is no lexical feature [

± anaphor] available to linguistic theory. This has implications for the classification of empty elements.

1. Dravidian taanu has been labelled a ‘reflexive’ in traditional as well as recent work (e.g. Mohanan 1981). This label has led to its classification as an anaphor. It will become evident from our argument that this is a misclassification, and that taanu is a pronoun.

2. There is a preference for (5) over (4c) in my dialect. There are dialects in which (4c) is fully grammatical.

3. The sentences in (8) instantiate the ‘Dative Subject’ construction characteristic of this linguistic area: cf. Masica (1976), Sridhar (1976).

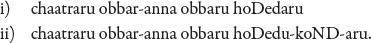

4. That this is a property of the construction and not of the verb is shown by (i) and (ii) below. The verbs iru- ‘to be’ and baru-‘to come’ can take koLLu in the ‘Nominative Subject’ constructions in (i), but not in the ‘Dative Subject’ constructions in (ii).

5. In a sentence with the reciprocal, koLLu introduces a subtle semantic difference which needs further investigation. Compare (i) and (ii):

While both mean ‘The students beat each other’, (i) suggests an orderly scene where A beats B and B beats A, while (ii) does not. Compare ‘The children each hit the others’ and ‘The children hit each other’ in English.

6. See Tirumalesh (1983) for a preliminary characterization of these functions. We also exempt from our discussion verbs which obligatorily take koLLu. Some of these verbs are intransitive, e.g. kuLitukoLL - ‘to sit’, tappisikoLL ‘to escape’, yendukoLL ‘to think, imagine that …’, koopisikoLL ‘to get angry’. Cf. also tabbikoLL ‘to embrace’, yettikoLL ‘to lift up, carry’.

7. The function of koLLu as a detransitivizer is complementary to the function of -isu in Kannada as a causativizer. Compare the transitive-intransitive pair (i):

8. One problem which remains is that of accounting for the apparently anaphor-like properties of taan(u), noted by Mohanan (1981):

Property (iii) is peculiar to taan(u); it does not hold of anaphors in general (the reciprocal can have non-subject antecedents). It is therefore irrelevant to the classification of taan(u).

For Kannada at least, it is not obvious that (i) is correct. Kannada taanu can take a discourse antecedent; it is here typically used for pronominal reference to a character whose point of view the writer (or reader) must adopt. (One form of discourse where taanu characteristically occurs, therefore, is “free indirect speech”.)

taanu thus appears to be a pronoun which always needs a linguistic antecedent.

There are two other kinds of occurrences of taanu which deserve mention. First, in a restricted range of cases, taanu appears instead of PRO in control structures.

Compare:

Observe that this taan is not the emphatic taane. There is however a slight sense of emphasis in the (b) sentences above, perhaps comparable to the sense of emphasis in clitic-doubled constructions in Spnaish, noted by Jaeggli (1981).

The restriction here is that taanu cannot appear in the place of non-subject controlled PRO. Thus an embedded taanu subject is not possible with matrix verbs like ottaya padisu ‘to force’ or prootsahisu ‘to encourage’.

Second, taanu appears in idioms like taanu maaduvudu uttama (roughly) ‘it is best to do one’s work oneself’ and taanu hiDida kooLige muuru kaalu ‘the hen that one has caught has three legs’ (said when one insists on an unreasonable opinion). There is a parallel here, it seems, with English one.

References

Belleti, A. 1979. On the Anaphoric Status of the Reciprocal Construction in Italian. MIT talk.

Chomsky, N. 1981. Lectures on Government and Binding. Foris Publications: Dordrecht.

Jaeggli, O. 1980. On some Phonologically Null Elements in Syntax. Doctoral Disst., MIT

Masica, C.P.1976. Defining a Linguistic Area: South Asia. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Mohanan., K.P. 1981. Grammatical Relations and Anaphora in Malayalam. M.Sc. Thesis, MIT.

Sridhar, S.N.1976. Dative Subjects, Rule Government, and Relational Grammar. Studies in the Linguistic Sciences Vol.1.

Tirumalesh, K.V. 1983. Kannada and Malayalam: Towards a Contrastive Study. Paper read at CIIL, Mysore.