K. A. Jayaseelan

In Lectures on Government and Binding (hereafter LGB), Chomsky (1981) proposed a binding theory which opposed (one to the other) anaphors and pronouns.* Anaphors (it was claimed) must be bound in a local domain; and pronouns must be free in the same local domain. LGB also proposed a feature analysis of nominal categories which was based on this opposition, and in which anaphors and pronouns were maximally opposed: anaphors were [+anaphoric, −pronominal] and pronouns were [−anaphoric, +pronominal]. Although the later discovery of long-distance anaphors somewhat disturbed LGB’s neat picture, we can confidently say that the opposition of anaphors and pronouns is still very much a part of the current theory. Thus, researchers still make use of the features [±anaphoric]/[±pronominal] when they wish to distinguish nominal classes.

In this paper we advance the claim that every anaphor either is a pronoun, or contains a pronoun. To be more precise: if the anaphor is morphologically simple, it is a pronoun; if it is morphologically complex, it contains a pronoun. In either case, the pronoun obeys Principle B. I.e. every monomorphemic anaphor obeys Principle B; and in every polymorphemic anaphor, the pronominal element contained in it obeys Principle B. If this claim is shown to be plausible, it may cast some doubt on LGB’s analysis of nominal classes, and suggest (rather) that anaphors are a subclass of pronominals.

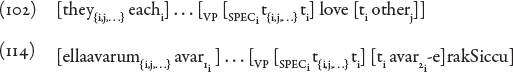

We demonstrate our claim with respect to both long-distance anaphors and local anaphors. In section 1, we examine the Malayalam long-distance anaphor taan.We show that taan requires an antecedent in the sentence and so is an anaphor; and yet it obeys Principle B, since it is illicit if bound in its governing category. In section 2, we glance at four other long-distance anaphors discussed in the literature – Japanese zibun, Korean caki, Chinese ziji, and Scandinavian seg/sig – and show that they confirm our claim. In sections 3 and 4, we look at two anaphors of English, the reflexive X-self and the reciprocal each other, both of which are commonly analyzed as local anaphors. We show (however) that there is mounting evidence (Zribi-Hertz 1989 and others) for adopting the view that the reflexive can take a long-distance antecedent; only the reciprocal is a local anaphor. In section 5, we look at a local anaphor of Malayalam, the ‘distributive’ awar-awar. Section 6 is the conclusion.

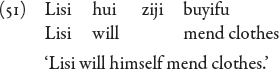

Taan in Malayalam is a reflexive anaphor. It is singular and [+human], and is unmarked for gender. It is currently analyzed as third person, but there is some reason to think that it is unmarked for person too. Its plural form is taŋŋaL.Taan (or taŋŋaL) is taken to be an anaphor because it requires a c-commanding antecedent in the sentence, cf. (1):1

In (1a), taan has a c-commanding antecedent, and so the sentence is fine. (1b) is ungrammatical because taan has no antecedent, and (1c) is ungrammatical because the antecedent of taan does not c-command it.2

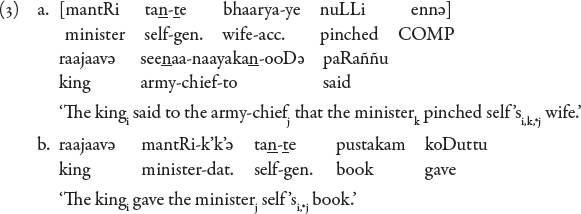

However, the antecedent of taan (or taŋŋaL) can be at any distance from it; in particular, it can be outside the minimal clause containing the anaphor, cf. (2):

As (2) shows, the binding relation is not affected by an intervening specified subject or boundary of a tensed S. In this respect, taan contrasts with Icelandic sig and Hindi apnaa, which are subject to Tense Opacity (Anderson 1983, Gurtu 1985).3

Like other long-distance anaphors, taan observes a subject-antecedent condition, cf.

However there are two kinds of exceptions to this condition, illustrated in (4) and (5):4

In (4), raaman-te (‘Raman-gen.’) is a licit antecedent of taan, yet it is not a subject but a genitive DP within a subject. (Note that raaman-te also fails to c-command the anaphor.) It is significant however that the head noun of the NP in the subject DP, namely paraati (‘complaint’) or kalpana (‘order’), denotes an act of ‘saying’ or ‘thinking’, and that the embedded clause represents what is ‘said’ or ‘thought’. That is, these embedded clauses are in logophoric contexts. The taan in the embedded clause can be bound by ‘Raman’ because ‘Raman’ is the agent of the ‘saying’ or ‘thinking’. When taan is not in a logophoric context, the antecedent of taan cannot be a genitive within the subject:

In (5), raaman-e (‘Raman-acc.’) is apparently the direct object of the sentences, and yet is a licit antecedent of taan contained in the subject phrase. It may be noted, however, that the verbs in these sentences are the so-called ‘psych verbs’ or psychological predicates. In sentences involving these verbs, the DP bearing the Experiencer θ-role is known to exhibit subject-like properties. The same phenomenon appears also in sentences where the Experiencer is encoded as a dative DP – the so-called ‘Dative Subjects’ of South Asian languages:

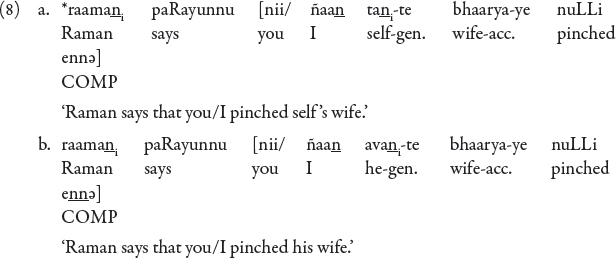

Taan also shows the familiar ‘blocking effects’ of long-distance anaphors (Huang & Tang 1989, Burzio 1989, Cole et al. 1990). Thus, taan—which takes only a third person antecedent—is blocked from being coreferential with a long-distance third person subject, if an intervening subject is non-third person. This is shown by (8a). ((8b) shows that no such effect obtains with the ‘regular’ pronoun avan ‘he’.)7

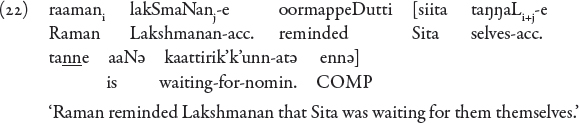

So far, taan fits perfectly our picture of long-distance anaphors. We now proceed to disturb that picture. First, we note that taŋŋaL (plural of taan) can have split antecedents:

We point this out because the ability to take split antecedents has been taken to be a property of pronouns, and has often been used as a test to distinguish pronouns from anaphors (see Zribi-Hertz 1989 for a discussion.)8

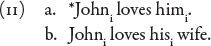

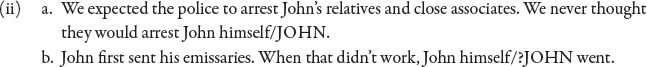

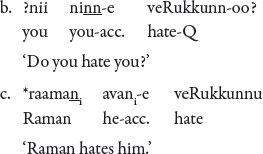

We now come to the property of taan which is of greatest interest to us, namely that taan is subject to Principle B, the obviation principle that applies to pronouns. (This fact has been noted in Mohanan 1982, Amritavalli 1984.) In (10) below, the (a) sentence is not possible, although the (b) sentence is fine:

If we take taan to be a pronominal, the facts are unsurprising, cf. English pronouns:

The ‘regular’ pronouns of Malayalam—avan (‘he’), avaL (‘she’), avar (‘they’), ñaan (‘I’), nii (‘you’), etc.—also show similar behaviour:

With the indicated coreference (12b) is fine, but (12a) is out. ((12a) is, of course, fine if avan-e is given a free reading.)

The Principle B effect with taan is not confined to verbs like sneehik’k'’(‘love’) or veRukk (‘hate’). In (13) we illustrate this effect with verbs of action, perception, belief, etc.:

The effect also shows up within nominals:

Taan’s obeying Principle B (then) is a completely general phenomenon.10

When taan is an argument of an embedded clause, as in (15) below, even speakers who otherwise judge a sentence like (10a) to be not totally unacceptable (see fn. 9) admit a very strong preference for the matrix subject as its antecedent. (We give a functional explanation for this ‘strengthened’ effect, in fn. 18).

Now, the behaviour of taan is paradoxical. It is like an anaphor in requiring an antecedent; but it is like a pronoun in obeying Principle B. Is it an anaphor or a pronoun? Our answer is: it is both. As we said earlier, our claim is that morphologically simple anaphors are pronouns.

We can distinguish a pronoun like taan which needs to be bound, from a ‘regular’ pronoun like avan which does not need an antecedent in the sentence, in terms of their inherent features. It is now widely recognized that long-distance anaphors are nominal elements which lack (some) inherent Φ-features—a fact which may explain their dependence on an antecedent. (See Burzio 1989,11 Huang & Tang 1989:199–200, Reinhart & Reuland 1991:286 and Reinhart & Reuland 1993:58.) We can refer to pronominal elements which become anaphors owing to a lack of some Φ-features ‘feature-deficit anaphors’. (We shall later distinguish these elements from another class of anaphors.) Avan (we can now point out) has a ‘saturated’ feature-matrix: it is third person, singular, masculine. Taan is lacking in the gender feature, and probably also in the person feature. (In our discussion of Japanese zibun, Korean caki and Scandinavian seg/sig, we shall be pointing out that these forms also lack some Φ-features.)

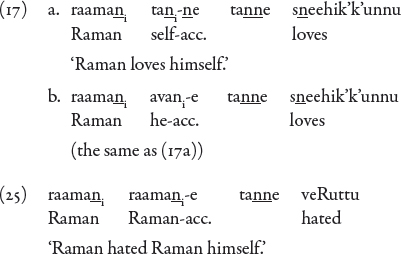

But we began our discussion of taan by saying that taan is a reflexive anaphor. In a typical reflexive context, the direct object of a transitive verb corefers with the verb’s subject. But if taan is the direct object, such a coreference is prohibited by Principle B, as we have just shown (cf. (10a)). To function in this context, taan must resort to a strategy which ‘gets around’ the operation of Principle B. The strategy it resorts to is that of taking a contrastive focus marker. The Malayalam focus marker corresponding to English X-self is tanne; cf. (16):

As (16) shows, tanne is an invariant form, unlike English X-self which is marked for person, number and gender.12

The unacceptable sentences, (10a) and (12a), become fine if tanne modifies the pronouns, cf.

We shall defer for the moment the question of how the presence of the focus marker ‘saves’ these sentences from the operation of Principle B. We now note the following. The complex forms taantanne and avantanne have all the properties of their ‘basic’ forms. Thus, taantanne, like simple taan, must have a c-commanding subject antecedent; it shows blocking effects; and its plural form taŋŋaLtanne can take split antecedents. Avantanne, like simple avan, can take a non-subject or non-c-commanding antecedent, or be without any antecedent in the sentence; and it shows no blocking effects.

Thus in the sentences of (17) (above), (17a) (with taan) has only a reflexive reading, because taan requires an antecedent in the sentence; but (17b) (with avan) has both a reflexive reading and a free reading. This becomes clearer in a pair of sentences like (18):

Because of the mismatch of number, taan cannot corefer with the subject of (18a). (Recall that taan is singular.) But since taan must be bound in the sentence, (18a) is out. But in (18b), avantanne can still be interpreted as a contrastively focused pronominal with a discourse antecedent. If (18a) and (18b) are embedded, both tannetanne and avanetanne can take an antecedent in the matrix clause and be interpreted as contrastively focused pronouns:

(20) (below) shows that avane tanne can take a non-subject or even a non-c-commanding antecedent, but not tannetanne:

(21) (below) illustrates the blocking effect. Contrast the grammatical sentence (19) (above), with the ungrammatical sentence (21a). ((21b) shows that awantanne shows no blocking effect.)

(22) (below) shows that taŋŋaLtanne, the plural of taantanne, can take split antecedents:

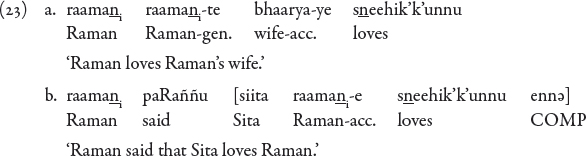

In order to complete our picture of reflexive forms in Malayalam, we must also glance at the pronominal use of proper names in this language. (See Jayaseelan 1991 for a fuller discussion.) Malayalam shares with some other oriental languages (e.g. Thai and Vietnamese, see Lasnik & Uriagereka 1988, Lasnik 1989, Lagsanaging 1990) the feature that a proper name can be c-commanded by a coreferential use of the identical proper name, in apparent violation of Principle C. Thus, sentences of the following type are perfectly grammatical (and very commonly used) in Malayalam.

The second occurrence of the proper name (however) seems to be functioning like a pronoun. Firstly, it shows Principle B effects, a fact noted also in Thai and Vietnamese (Lasnik 1989, Lagsanaging 1990). Thus, (24) is ungrammatical:

Secondly, and very interestingly for us, a sentence like (24) can be made fine, if we reflexivize the second occurrence of the proper name by the addition of the focus marker tanne:

Note that what we have in a sentence like (25) is a reflexive formed from a proper name. Since any proper name can be turned into a reflexive in this way, we can see that ‘reflexivization’ in Malayalam must be a fully productive rule, and the class of reflexives is not a closed set. The significance of this fact for a theory of reflexive forms across languages is the following: an approach (like that of LGB) which simply marks certain linguistic forms as anaphors in the lexicon is inadequate. Malayalam – and probably also Thai and Vietnamese – force us to postulate a syntactic process which ‘reflexivizes’ pronouns, in the sense that it applies to basic pronominal forms which are anti-local and outputs complex forms which accept an antecedent within the minimal clause.14

We now turn to this ‘reflexivization’ process and so return to the deferred question of the interaction of the focus marker tanne with Principle B. The problem may be stated as follows: we have shown that in a complement position of V, e.g. the direct object position, the anaphoric pronoun taan, or the regular pronoun avan, or a proper name used like a pronoun, cannot corefer with the subject of the minimal clause containing it; but if these forms are ‘covered’ by tanne, they can. How does this happen? The relevant examples are (17) and (25), repeated below:

The focus marker tanne is, in terms of category, probably a Determiner. We may assume, following a long tradition in linguistics (beginning at least with Postal 1966), that pronouns belong to the category of Determiner, not Noun (see Abney 1987:281 ff. and references cited there for arguments). (This position is particularly appealing for Malayalam, because its regular pronouns avan (‘he’), avaL (‘she’), avar (‘they’) are historically derived from the demonstrative aa (‘that’) with the suffixation of the usual agreement markers of the language.) Pronouns must (in fact) be considered ‘intransitive determiners’ since they do not take NP complements (as Abney points out, ibid.). Now, the focus marker tanne is historically derived from taan:

taan + -ee (focus-marking suffix) → tanne

It is reasonable to think that while tanne is no longer a pronoun (since it is no longer referential), it has not changed its category: it continues to be an ‘intransitive determiner’.

The determiner tanne naturally projects its own DP, of which the element it contrastively focuses, we may assume, occupies the SPEC position. For the complex forms taan tanne/ avan tanne/ raaman tanne we can postulate the structure (26):15

A similar structure has been proposed for Japanese zibun-zisin in Katada (1991) and for Norwegian seg selv in Hestvik (1990).

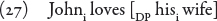

Given the structure (26), we can straightaway see how the pronoun in this configuration apparently escapes the effect of Principle B. Its position is parallel to that of the pronoun in a sentence like (27):

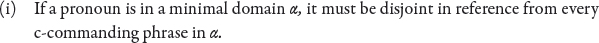

Let us assume Chomsky’s (1986) reformulation of Principle B:

In (27), the pronoun is governed by the head of DP, and therefore it need be A-free only in the CFC of this head, which is the DP itself.

Now in (26), the pronoun is again in SPEC, DP. It is governed by tanne. The category which contains the CFC of tanne is DP* itself. And the pronoun is A-free in this domain. (DP* itself is not subject to Principle B, since it is not headed by a pronoun but by a non-pronominal determiner.)

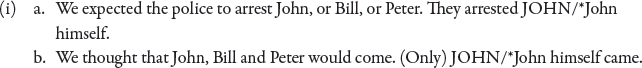

We should perhaps point out that stress (by itself) cannot enable a pronoun to take an antecedent within the minimal clause. Thus, stress does not save the following sentence from being ‘starred’ by Principle B:

The branching structure of (26) seems to be crucial for this function. Intuitively we can see that the function of the focus marker is to create a smaller domain in which disjoint reference is operative, so that the pronominal is free to corefer with the other arguments of a predicate which may take DP* as its complement.17

To conclude this section: observe that our claim (in the Introduction) that morphologically simple anaphors, and the pronouns contained in morphologically complex anaphors, obey Principle B, is vindicated in the Malayalam cases.

Also observe a three-way classification of the reflexive forms in Malayalam: simple taan is an anti-local anaphor, and the complex form taantanne is a non-local anaphor; but the complex form avantanne is not an anaphor at all. (The last, because avantanne requires no antecedent in the sentence.) We have explained why these three forms behave in these different ways.

In this section, we very briefly try to show that some other long-distance reflexives commonly discussed in the literature confirm our claim that morphologically simple anaphors are pronouns, and morphologically complex anaphors contain pronouns. A point we shall be making is that many complex reflexive forms which are commonly taken to be local anaphors, are on closer examination seen to be non-local; i.e. they can take both local and long-distance antecedents. We shall show that a reflexivization process parallel to that of Malayalam can account for the behaviour of these complex forms.

Katada (1991) presents an analysis of three reflexive anaphors in Japanese: zibun, zibun-zisin and kare-zisin. These exhibit a striking degree of correspondence to Malayalam taan,taantanne and avantanne (respectively).

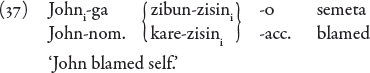

Zibun is a form which is marked [+human] and is unmarked for person and gender. So we can say that it is a ‘feature-deficit’ anaphor; it contrasts in this respect with kare (‘he’), which has a ‘saturated’ feature-matrix. It has a plural form zibun-tati. It is a long-distance reflexive with a subject-orientation, cf. (30) (adapted from Katada’s (3)):

Zibun can be anteceded by the matrix subject ‘John’, or the subject of its own clause ‘Bill’, but not by the non-subject ‘Mike’. However, note that zibun here is in SPEC, DP. When it is a complement of V, e.g. the direct object, its coreference with the subject of the minimal clause containing it is infelicitous, cf. (31) (adapted from Katada’s (28a); the grammaticality judgement is Katada’s):

This hitherto unexplained—and infrequently noted – fact can be explained if zibun is subject to Principle B.18

Since in much current literature, the ability to have ‘split antecedents’ is taken to be peculiarly a property of pronouns, we may note that zibun-tati can take split antecedents (examples from Kitagawa 1986:377, 378):

Zisin is a marker of contrastive focus in Japanese:19

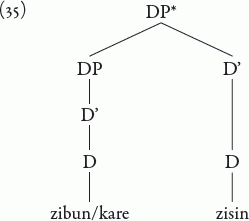

And kare (‘he’) is a ‘regular pronoun’ (and so, does not need an antecedent in the sentence).20 Katada (1991:294) proposes the following structure for zibun-zisin and kare-zisin:

Adapting this to the DP-analysis of Abney (1987), which we have been assuming throughout, we can say that zibun-zisin or kare-zisin – or any other of the morphologically complex reflexive forms of Japanese such as kanozyo-zisin (‘herself’) watasi-zisin (‘myself’), karera-zisin (‘themselves’, masc.) – is a DP headed by zisin, and the pronoun occupies the SPEC position of this DP.

Interestingly, Katada (ibid.) notes the parallelism of her structure for zibun-zisin/kare-zisin with the structure of a phrase like zibun-no hahaoya (‘self’s mother’):

Pursuing the logic of this parallelism, we can say that zibun or kare in the structure (35) apparently escapes the effect of Principle B for the same reason that a possessive pronoun escapes that effect in an English sentence like John loves his wife. I.e. the pronoun is governed by zisin, and so it can satisfy Principle B by being A-free in the CFC of zisin, which is DP*.

We predict (therefore) that if any of these complex forms occurs as a complement of a verb, it can corefer with the minimal subject. This prediction is correct, cf. (37) (adapted from Katada’s (28a)):

Contrast (37) with (31), which is less than fine. And compare both with (10a) and (17), to see the parallelism with Malayalam.

We also predict that, owing to the subject-orientation of zibun, zibun-zisin – like taantanne – can take only a subject antecedent, whereas kare-zisin – like avan tanne – has no such restriction. This (again) is correct, cf. (38) (=Katada’s (4)):

Compare (38) with the Malayalam sentences in (20).

Since kare (a regular pronoun) needs no antecedent in the sentence, we also predict that kare-zisin can occur without an antecedent in the sentence, with the meaning of a contrastively focused pronoun (possibly with stress – but see fn. 13 in this connection). This prediction is borne out by the following sentence:

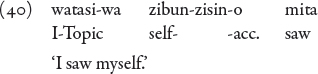

Compare (39) with (18b), a similar Malayalam sentence. Since zibun zisin requires an antecedent in the sentence, (40) can have only a reflexive reading:

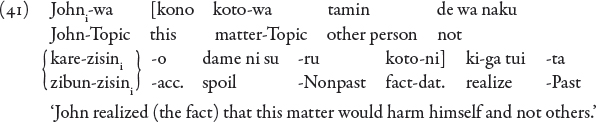

Regarding long-distance binding of zibun-zisin, the established position now is that this is not possible. In fact, a good deal of theoretical work on anaphora is devoted to explaining why a simplex form like zibun can be long-distance bound but a complex form like zibun-zisin must have a local antecedent. (See, among others, Pica 1987, Cole et al. 1990, Katada 1991.) However, in eliciting informant judgements in this matter, care must be taken to eliminate an extragrammatical factor. If both a local antecedent and a long-distance antecedent are grammatically permissible, there is (it would seem) a strong tendency to choose the local antecedent. Psycholinguistic evidence is relevant here: thus in an acquisition study of Chinese ziji, which is an anaphor universally admitted to allow both local and long-distance antecedents, a control group of adults chose the local antecedent for ziji 90% of the time (Chien & Wexler 1987). Now, if we take care of this ‘proximity effect’ by testing also with examples in which the local antecedent is ruled out owing to mismatch of semantic features, we get some surprising results for zibun-zisin. Consider (41):

In (41) kare-zisin or zibun-zisin can corefer with ‘John’ quite unproblematically (and it cannot corefer with the embedded subject ‘this matter’ because the latter is [—human]). Compare (41) with the Malayalam sentence (19) to appreciate the parallelism.

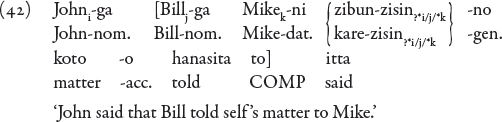

However it is true that in a sentence like (42) adapted from Katada’s (3) (the grammaticality judgements are Katada’s):

there is clearly a strong preference for the local antecedent. But we can now say that this preference is not a binding theoretical effect, for otherwise it should rule out (41).21

If zibun-zisin and kare-zisin can take both local and long-distance antecedents, note that this is precisely what is predicted by our account of the complex forms. Zisin only enables a basic pronominal form, which is anti-local, to accept an antecedent within the minimal clause. Apart from this, the properties of the complex forms are simply those of the basic forms. Thus, long-distance bound zibun-zisin still requires a c-commanding subject antecedent. (This fact should sufficiently disprove any possible claim that this zibun-zisin is a different form, say an ‘emphatic pronoun’.)

To conclude this section: in our classification of reflexive forms, zibun is an anti-local anaphor, zibun-zisin is a non-local anaphor, and kare-zisin is not an anaphor at all since it can occur without an antecedent in the sentence.

The Korean long-distance reflexive caki is [+human], singular and third person. We can say that it is a ‘feature-deficit’ anaphor because it is unmarked for gender and so is less fully specified than the regular pronouns of the language. Its plural form is cakitul. There is a related word casin22 whose function is to mark contrastive focus.

Casin is added to pronouns to form contrastively focused pronouns. Thus we have forms like the following: caki-casin (‘himself/herself’), cakitul-casin (‘themselves’), ku-casin (‘himself’), kuyne-casin (‘herself’), ce-casin (‘himself/herself/itself’), na-casin (‘myself’), ne-casin (‘yourself’) (Choi 1988). All these forms also figure as reflexives. Casin can also apparently occur alone, as a reflexive.

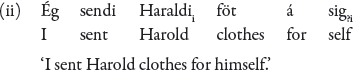

Caki patterns with Malayalam taan and Japanese zibun in that (a) it is a subject-oriented anaphor; and (b) it can take a long-distance antecedent but not a local antecedent. This latter fact has been noted by Lee (1986) and Cole et al. (1990:18). Cole et al. provide the following examples. (The grammaticality judgements are theirs.)

We can explain this fact if we say that caki (like zibun or taan) is a pronominal.23

Cakitul, the plural of caki, takes split antecedents as noted by Jeon (1989:114):

Jeon (1989:96) also gives the following example of caki taking a discourse antecedent in a logophoric context:

See fn. 2 for a parallel instance of the logophoric binding of taan.

The complex ‘pronoun-casin’ forms listed above can all take a local antecedent. Interestingly, a ‘bare’ casin can also take a local antecedent. These facts are illustrated in (48) (adapted from Cole et al.’s (20a), (22a) and (19a)):

If we can maintain that a ‘bare’ casin is underlyingly ‘pro-casin’24 we gain two advantages: firstly, we can ‘regularize’ the distribution of casin, which can now be seen as invariably a focus marker attached to a DP. Secondly, we can explain the different behavior of all ‘pronoun-casin’ forms (as compared to simple pronouns) with respect to a local antecedent: within the complex form ‘pronoun-casin’, casin – a determiner heading the complex form – governs the pronoun and thereby limits the domain in which the pronoun is required to observe disjoint reference.

It has been claimed (as in the case of Japanese zibun-zisin) that the complex form caki-casin, as well as other complex forms such as ku-casin ‘himself’, are local anaphors; see Cole et al. (1990). The claim (however) is incorrect, cf. (49) (example given by Yong-Tcheol Hong):

In (49), any of the four forms – caki, caki-casin, casin, ku-casin – can refer to the matrix subject; and it cannot refer to the embedded subject because the latter is [—human].

In terms of our three-way classification of reflexives, caki is anti-local, caki-casin and ‘bare’ casin are non-local, and ku-casin is not an anaphor at all.

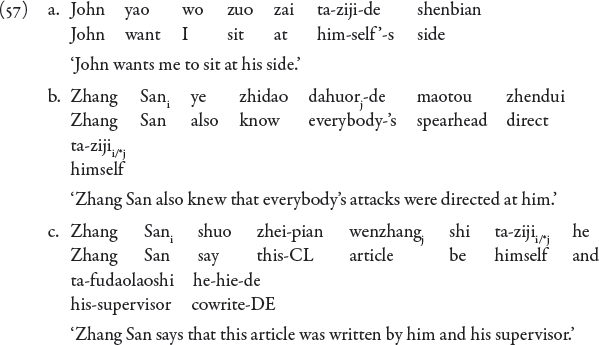

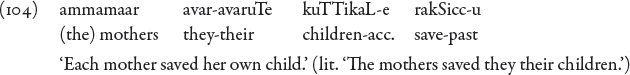

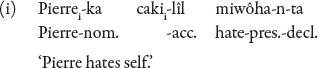

Chinese ziji, which is a form unmarked for person, number or gender, is attached as a contrastive focus marker to DPs:

Like English X-self, which it resembles in all its functions, ziji ‘floats’ rightward:25

When attached to pronouns – such as ta (‘he’ or ‘she’), tamen (‘they’), wo (‘I’), ni (‘you’) – it yields contrastively focused pronouns: ta-ziji (‘he himself’ or ‘she herself’), tamen-ziji (‘they themselves’), wo-ziji (‘I myself’), ni-ziji (‘you yourself’), etc. All these focused pronouns also ‘double’ as reflexives. Interestingly, a ‘bare’ ziji can also function either as a reflexive or as a focused pronoun. Thus, in (52) it is a reflexive:

and in (53), it is ‘ambiguous’ – according to Tang (1989:95) – between an ‘intensifying’ and a purely reflexive reading:

(The ambiguity judgement is Tang’s; probably the ‘intensifying’ reading is signalled by stress.) Tang (1989) suggests that ‘bare’ ziji is underlyingly ‘pro-ziji’. We shall adopt this suggestion. (Note the parallelism with our analysis of ‘bare’ casin in Korean.)26

A simple pronoun in a complement position of a verb cannot be bound by the minimal subject:

But ta-ziji or pro-ziji can be bound by the minimal subject:

This is predicted by our analysis: within the complex form ‘pronoun-ziji,’ the pronominal is governed by ziji; so that the pronominal need observe disjoint reference only within the CFC of ziji which is the complex form itself.

‘Bare’ ziji can take any c-commanding subject as antecedent, including a long-distance one (example from Cole et al. 1990):

But it has been claimed that ta-ziji etc. are local anaphors (Tang 1989, Huang & Tang 1989, Battistella 1989, Cole et al. 1990). The claim (however) is apparently incorrect. Yu (1992) provides many examples of ta-ziji which is long-distance bound:

Yu also provides examples of ta-ziji which has no antecedent in the sentence:

These facts accord with our predictions, which are that ta-ziji (as a focused pronoun) should have the option of a free reading, and that ‘bare’ ziji (‘pro-ziji’) must be bound in the sentence, either in the local or longdistance domain, because pro must be so bound. (The apparent exceptions are cases of logophoric binding, see Yu 1992 for examples.)

In our classification, ziji is a non-local anaphor, and ta-ziji is not an anaphor at all.

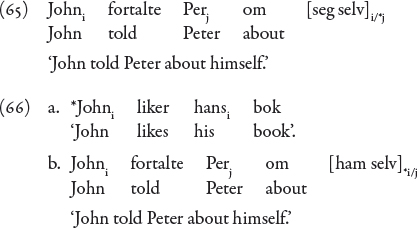

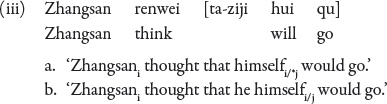

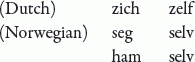

The Norwegian seg, or the Danish, Swedish or Icelandic sig – we refer to all these elements as sig – is a reflexive form which takes only a third person antecedent, but is unmarked for number and gender. It contrasts in this respect with a regular pronoun like (Nor.) han ‘he’ which is fully specified for the Φ-features. (Sig is in fact the accusative form of the reflexive; it has no nominative form.)

Sig patterns with Malayalam taan, in that (i) it is subject-oriented; (ii) it takes a long-distance antecedent; and (iii) it cannot be bound in the local domain (Hestvik 1990:61 ff.). Consider the following Norwegian examples (from Hestvik 1990):

In Icelandic – but apparently not in Norwegian (Hestvik 1990:63) –, sig can also be logophorically bound; Maling (1984) provides the following example, in which the c-command condition on binding is superficially violated. (It may be compared with the parallel Malayalam sentences (4a, b).)

(Sig differs from taan in one respect: an antecedent cannot bind sig across the boundary of a tensed clause (Anderson 1983).)

There is an element selv in Norwegian and Danish (sjálf in Icelandic) which, like the English X-self, is added to DPs for contrastive focus (example from Hellan 1986):

Now, the sentences of (61) become grammatical if selv is added to sig:

We can straightaway explain the ungrammaticality of (61), if sig is a pronoun; and we can account for the acceptability of (64) in the now familiar way, by saying that in seg selv – or in the other complex forms such as ham selv ‘him himself’ – the pronoun is governed by selv, and therefore need be free only in the CFC of this governor (which is the complex form itself).30

Apart from enabling the pronoun to be bound in the minimal clause, the presence of selv does not alter the properties of the pronoun in any way. Thus, seg selv is subject-oriented because seg is subject-oriented, cf. (65). And since ham ‘him’ is anti-subject oriented in the domain of the minimal subject, cf. (66a) – this is a peculiar property of Scandinavian non-reflexive pronouns, see Hestvik (1990, 1992) –, ham selv is also anti-subject oriented, cf. (66b). (Examples from Hestvik 1990:8, 198.)

It has been claimed that the complex forms seg selv and ham selv are local anaphors (Hellan 1986, 1988; Hestvik 1990). But this is maintained only by analyzing a sentence like (67) as containing an instance of ‘another’ selv – a non-anaphoric element which carries ‘emphatic stress’ (Hellan 1986:104):31

In our classification, sig is an anti-local anaphor, sig selv is non-local, and ham selv is not an anaphor at all.

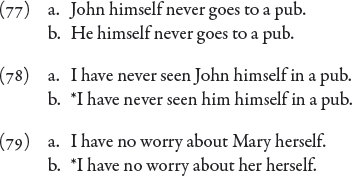

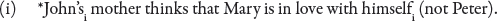

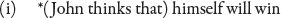

The English form X-self (X the genitive or the accusative form of a pronoun) occurs either attached to a DP, as in (68); or independently in an A-position, as in (69) and (70):

The X-self of (68) is clearly a marker of contrastive focus; and it carries stress. In the current theory, there appears to be no particular proposal regarding it. (What is the category of this X-self? What is the structure of a phrase like John himself in (68)?). On the other hand, the X-self exemplified in (69) has had a lot of attention paid to it. It is analyzed as a local anaphor. It is kept separate from the X-self exemplified in (70) by appealing to stress and meaning. The anaphoric X-self (so the claim goes) is unstressed and has a purely ‘reflexive meaning’, whereas the X-self of (70) – probably an ‘emphatic pronoun’32 – is stressed and carries a meaning of contrastive focus. We therefore have, going by the current theory, three X-selfs in English.

Regarding the [DP X-self] configuration of (68), we can extend to it our analysis of the parallel phrase in Malayalam. That is, we analyze the English phrase as having the following structure:

The focus-marker may ‘float’ rightward, like some quantifiers; when it does, it may occur in all the positions in which floated quantifiers may occur and in addition in the sentence-final position (the right-peripheral position of VP), cf.

X-self may float only from a subject DP, cf. (73): this is a property which Baltin (1982) has noted as belonging to floated quantifiers, cf. (74):

Also, the relation of a floated X-self to its antecedent is subject to SSC, cf. (75); as is well-known, floated quantifiers are also subject to this constraint, cf. (76):

We can explain these properties if we say that the subject of a clause is generated within the ‘innermost’ VP and moved to [SPEC, IP] cyclically through the SPEC-positions of all intervening maximal projections (Fukui & Speas 1986, Chomsky 1992, Huang 1993); and that a ‘floated’ X-self (or quantifier) is ‘stranded’ in an intervening [SPEC, VP] (Sportiche 1988). Since only subjects move up (overtly) in English, ‘floating’ is possible only from a subject. If the ‘floated’ element must adjoin to its antecedent by SPEC-to-SPEC movement in LF, an intervening ‘filled’ SPEC position (in particular, an intervening subject) will block this movement.33

We have already suggested (in fns. 13 and 17) that the stress and meaning arguments customarily adduced to keep apart the X-selfs of (69) and (70) have little substance in them. We shall therefore treat these X-selfs as the same X-self. What is the structure of this X-self?

Luckily, we have a clue to its proper analysis in the following configuration of data.

What these data suggest is that X-self may not co-occur with a non-nominative pronoun.34 (That it is the Case of the pronoun, and not its subjecthood, that is crucial, is shown by (80b).) Whatever may be the explanation of this restriction, we can state it (for our purposes) in the form of a filter:

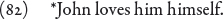

(81) expressess the fact that there is a ‘gap in the paradigm’: we have both ‘full’ DPs and pronouns with contrastive focus markers in nominative positions; but in non-nominative positions, we have only full DPs and no pronouns, with these markers. (Alternatively, pronouns are rare with these markers.) The existence of this gap is significant for our analysis. We can now see that it is because English has the filter (81) that we do not get a sentence like:

If we postulate that, in contexts affected by the filter, English in fact employs the non-lexical pronoun pro, we immediately fill the gap in the paradigm. We wish to suggest (therefore) that the ‘bare’ X-self of (69) and (70) has the following structure:36

(Note that if the occurrence of pro must be ‘licensed’ by a governing element which identifies its feature content (Chomsky 1982, Rizzi 1986), it always is, in this configuration: pro’s Φ-features are uniquely identified by X-self, which governs it.)

If we can assume that pro also needs to get an index from a c-commanding antecedent in the sentence,37 we can now explain why ‘pro himself’ is an anaphor, whereas John himself and he himself are not. Thus, while (68) and (77b) (repeated below) are grammatical, (78b′) (a variant of 78b) is still ungrammatical:

Similarly, (84) is ungrammatical, and (85) is unambiguous:

Note that the structure (83) is completely parallel to (71). We have now unified the three X-selfs of English. Moreover, the formation of the English reflexive construction is now completely parallel to that of the complex reflexives of Malayalam, Japanese, Korean, Chinese and Scandinavian. We can (therefore) naturally extend our analysis of these other complex reflexives to English; [pro X-self], we can say, can take a local antecedent because X-self governs pro and limits the domain in which the pronoun must be A-free.39 The LGB analysis, which simply labelled the reflexive X-self an anaphor, seemed to foreclose all questions and block further enquiry into the nature of ‘reflexivization’; but with the observing of the parallelism with other languages, we have a new understanding of this issue.40

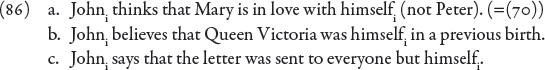

Its position in SPEC, DP enables the pro in ‘pro X-self’ to take a local antecedent; but it does not make it a local anaphor. Like the complex reflexive forms of the other languages that we have examined, it can be bound from a higher clause:

Again, English X-selves can take split antecedents like the other reflexives:

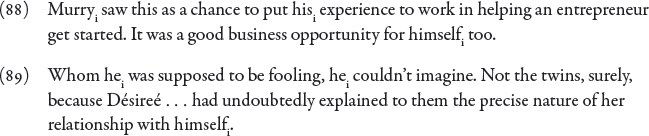

We said that pro must be bound in the sentence. But like other ‘feature-deficit’ anaphors, it can occur without an antecedent in the sentence in logophoric contexts:42

X-self can also have a non-c-commanding antecedent in cases where it is logophorically bound:43

We see (then) that the claim that X-self is a local anaphor which obeys Principle A cannot be entertained. In our classification of anaphors, the English reflexive is a non-local anaphor.44

Let us point out (at this juncture) that with all the reflexive forms that we have considered, we have vindicated our claim that morphologically simple anaphors are pronouns, and morphologically complex anaphors contain pronouns.

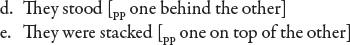

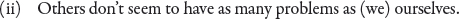

We now turn to truly local anaphors. We show that English each other and Malayalam avar-avar contain pronouns.

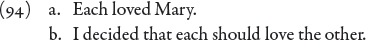

It seems fairly clear that, like the Italian reciprocal l’uno … l’altro (Belletti 1982) or the Kannada reciprocal obbaranna obbaru (Amritavalli 1984), English each other also has a bipartite structure. Of these, the second part, namely (the) other, is in itself not an anaphor but a pronominal (like one). Thus it can occur without an antecedent in the sentence (cf. (91)), or with an antecedent outside its governing category (cf. (92)):

In (92), on the more obvious reading, the other picks its referent from the set denoted by the boys. But (92) also has another reading, which illustrates an important point: so long as each and (the) other are ‘apart’, (the) other always has also a ‘free’ reading, in which it picks its referent from the discourse or from a different DP than each picks its referent from. This becomes clearer if (92) is ‘continued’ as in (93):

But in each other, the second element has only a ‘bound’ reading, in which it picks its referent from the same DP as each.

Note that each does not have a ‘free’ reading in (92); i.e. each must pick its referent from the boys. This is obviously because each is in a θˉ-position and must get a θ-role by being associated with the boys. In contexts where each occupies a θ-position, it in fact has a ‘free’ reading:

Like any pronoun, (the) other is subject to the principle of disjoint reference, cf. (95):

The referent of the other (one) in (95a) or that of either one or the other in (95b), cannot be in the set denoted by they.46 This being the case, a question we must ask is how (the) other escapes the effect of Principle B in a sentence like (96a), or like (96b) on the reading wherein the other picks its referent from they.

That is, there is a problem which is similar to the one we encountered in the case of reflexives, which too contain pronominal elements.

The problem could also be stated using the other English reciprocal, one another. Since another is disjoint in reference from they in (97a), how does it escape the effect of Principle B in (97b)?

The sentence (96b) is particularly interesting because it shows that treating each other as a lexical anaphor, which (for that reason) is not subject to Principle B, is an insufficiently general solution. In (96b) there is no each other. And yet the operation of Principle B is blocked, exactly as in (96a).

Each is a quantifier word which occurs both prenominally, modifying a lexical or ‘empty’ head noun (Each boy/Each of the boys/Each loves a girl), and postnominally (Tell them each to do a different thing). It is one of the quantifier words which may ‘float’ rightward. When it does, it occurs in positions immediately preceding a V (modal verb, aspectual verb, or main verb). Baltin (1982) sought to generate this distribution by stipulating that a floated quantifier must be left-adjoined to a ‘V-projection’, i.e. a VP. But we can obtain this distribution more intuitively if we say that a floated quantifier is in SPEC, VP (Sportiche 1988).

It is clear that the floated quantifier has no independent θ-role apart from that of its antecedent. If we assume that it must be adjoined to its antecedent at LF, and that it must move cyclically through intermediate Specs in order to do that, we get the SSC effect shown by floated each as a bonus: an intervening ‘specified subject’ would block its progress.

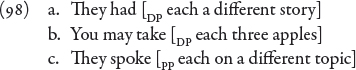

A VP with a quantifier word ‘subject’ is a small clause. Floated quantifier words may appear to form such small clauses also with PPs and DPs, given such sentences as (98):

But if we accept Richard Larson’s proposals (Larson 1988), the bracketed phrases of (98) could all be (simply) VPs from which the V has moved into a higher V position; the quantifier words each and one would then all be in the SPEC position of VPs. Now a VP with a ‘subject’ is (in a very obvious sense) a Complete Functional Complex. So we can offer to explain why (96b) (repeated below), on the relevant reading, does not violate the principle of disjoint reference:

Here, the other need be disjoint in reference only within the CFC of love, (its governor), which is the bracketed portion of (99). (In (99) we ignore the LF-movement of each.)

Importantly, note that each and the other are contra-indexed; i.e. each must pick a different index from they than the other picks. Otherwise, there will be a Principle B violation within the small clause. Thus the contra-indexing of each and the other does not have to be stipulated as a property of ‘reciprocal interpretation’, but follows from Principle B.47

The above account (however) needs to be made more precise in a certain respect, if we accept the ‘VP-internal subject’ hypothesis (Fukui and Speas 1986, Chomsky 1992, Huang 1993). If the subject they is moved out of the VP, ‘stranding’ each, in (96b), the SPEC of VP will contain a trace of they as well as each:

Here, the other is not disjoint from the trace of they. This in itself does not present a problem, since the trace does not c-command the other. The question is: how is the SPEC itself indexed? Let us follow the claim of Heim et al. (1991:74) that it is the ‘distributive operator’ each which gives its index to SPEC. (The claim, in effect, is that they each – like the more transparent each of them – has each as the head of the phrase.) The relevant structure (then) is:

Here, the other is (correctly) free in the VP.

We now come to the forms each other and one another. What is the position of each in each other? It seems clear (from the meaning) that each does not stand in the same relation to other in each other, as each stands to book in each book. In the latter case, each is the head of a phrase which takes the NP book as its complement (Abney 1987). Regarding each other, let us say (not crucially for our analysis) that DPs may have TOPIC positions, and that each occupies this position with respect to (the) other. (DPs have COMPs in some languages (Abney 1987); so it is not implausible that the parallelism between DP and IP structure can go all the way through.) Assuming that TOPIC (the same as COMP) projects a maximal phrase, each is possibly the specifier of TOPIC, whose complement is (the) other.48

The each of each other (like the ‘floated’ each) must adjoin to its antecedent in LF. When the antecedent is the subject like in (96b), we will say that each must adjoin to the subject by adjoining (in turn) to each of its traces in specifier positions of VPs. Accepting the claim of Heim et al. (1991), but extending it now to the traces of the subject, we will further say that after this adjunction, the SPEC nodes have the index of each at LF. (96a) (repeated below) will have the LF-representation (102):

Here, the trace of they does not c-command (the) other, and the specifier of VP (which does c-command it) is contraindexed. Therefore, the pronominal (the) other is free in the VP, which is the CFC of its governor.

Each other (unlike X-self) cannot have split antecedents:

This fact neatly falls out from our account of each other: each must be adjoined (by SPEC-to-SPEC movement) to the antecedent whose θ-role it shares, and it cannot be adjoined at the same time to two antecedents.

We have already shown how the necessity of adjunction via SPEC-to-SPEC movement accounts for the SSC effects on each other. We can predict that obeying SSC and disallowing split antecedents are two properties which will go together.50

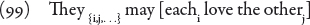

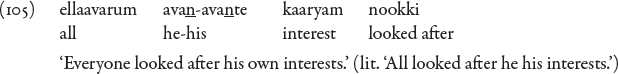

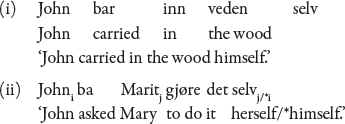

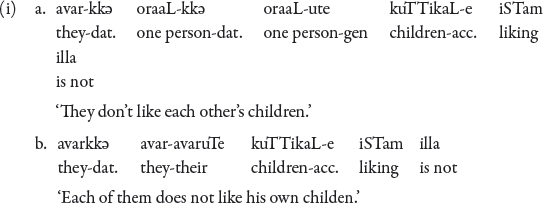

Malayalam has a ‘distributive’ anaphor avar-avar (lit. ‘they-they’), illustrated in (104):

Avar-avar has a singular, masculine variant avan-avan (lit. ‘he-he’):

Since avar-avar and avan-avan are third person forms, they cannot have non-third person antecedents, cf. (106); avan-avan also cannot have non-masculine antecedents, cf. (107); neither (of course) can have a non-plural antecedent, cf. (108):

Avar-avar (or avan-avan) is a local anaphor, like each other; thus, its relation to its antecedent is subject to SSC, cf.

The SSC effect can be straightforwardly explained, if we analyze avar-avar along the lines of each other. Note that in the bipartite structure avar1avar2, avar1 is an invariant nominative form; it is avar2 which shows the case-marking of the anaphor’s position in the sentence.51 (In all our examples so far, avar2 is genitive; but this of course is not necessary.) Let us say that avar1 is in a θˉ-position, specifically the TOPIC position of the DP avar-avar. And that, to be interpreted with a θ-role, it must be adjoined to its antecedent in LF, via SPEC-to-SPEC movement. An intervening ‘specified subject’ blocks this movement.

Let us note two further facts about avar-avar before we proceed. One, avar-avar (like each other) can be bound by a non-subject:

Two, the relating of avar1 to its antecedent does not seem to be subject to Tense Opacity, since at least some sentences in which this anaphor is the subject of an embedded tensed clause seem to be acceptable, cf.

We point this out to suggest that SSC and NIC should not be collapsed into a single principle, as is sought to be done in LGB.

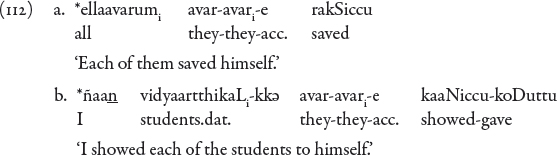

The interesting thing about avar-avar is that if it occurs in a complement position of a verb, e.g. the direct object position, it cannot corefer with the subject of its own clause, cf. (112a) or with another complement of the verb, cf. (112b). In other words, it cannot take a local antecedent.

These sentences however can be made grammatical by adding the focus-marker tanne to avar-avar:

Let us recapitulate what we have said about avar-avar and make clear what is happening here. We said that avar-avar is subject to (the SSC part of) Principle A, which requires it to be bound in the domain of the minimal subject. Then we showed that it is subject to Principle B, which requires that it should be disjoint in reference in the same domain when it is in a complement position. And it appears that the anaphor escapes from this predicament by taking the focus marker, which seems to limit the domain of operation of Principle B.

Superficially, it is puzzling that avar-avar, which is a complex form, behaves unlike other complex forms – e.g. each other or pro X-self – with respect to local antecedents. Thus there is a straightforward contrast between (112a) and (96a) (repeated below):

But we now go on to show that the unexpected behaviour of avar-avar can be explained; and the explanation is an interesting confirmation of our analysis.

In the case of each other, we said that each adjoins to (the trace of) the antecedent, and that the resulting adjunction structure has the index of each. We must assume that the same thing happens in the case of avar-avar. But observe the LF-representations that we get in the two cases: (96a) is represented as (102) (repeated below), and (112a) is represented as (114):

Since each and (the) other pick different indices from the antecedent, SPEC, VP (which gets the index of each) is contra-indexed with (the) other in (102). But to give the distributive meaning, avar1 and avar2 must pick the same index from its antecedent. Therefore, SPEC, VP is coindexed with avar2 in (114). Principle B is violated within the VP (which is the CFC of the pronoun’s governor).

Now in (113), the focus marker tanne has the familiar function which we examined at length in section 1: it projects a DP which takes the pronoun in its specifier position. We have (possibly) the following structure:

Here, tanne governs avar2, which now can be free in the CFC of this governor, namely DP*.52

To conclude our discussion of local anaphors, let us point out that our claim that complex anaphors contain pronouns has been shown to be true about each other and avar-avar. We have also explained why each other and avar-avar are local anaphors.

In this paper we showed that morphologically simple anaphors are pronouns, and morphologically complex anaphors contain pronouns. This suggests that LGB’s opposition of anaphors and pronouns is incorrect. We submit that anaphors are a subclass of pronouns.53

We divided anaphors into three classes: local, non-local and anti-local. Anti-local anaphors are morphologically simple pronominal forms which (in contrast to the ‘regular’ pronouns) are lacking in some (or all) Φ-features. Being pronouns, they cannot (when they are complements of V) be bound in the minimal clause. Non-local anaphors are complex forms which contain (again) one of these ‘feature-deficit’ pronouns, but the pronoun now is in the SPEC position of a DP headed by a marker of contrastive focus. This configuration limits the pronoun’s domain of disjoint reference to the focus-marker’s maximal projection; so that it can be bound either within the minimal clause or outside it. We can refer to both these classes, namely anti-local and non-local anaphors, as ‘feature-deficit’ anaphors (or equivalently, ‘feature-deficit’ pronouns). What makes these forms anaphors – i.e. what makes them need an antecedent in the sentence – is the ‘feature-deficit’.

‘Feature-deficit’ anaphors exhibit the following configuration of properties:

(i) they do not obey SSC (but some of them are sensitive to the Tense Opacity Condition);

(ii) they can take split antecedents;

(iii) they are subject-oriented (with some exceptions, e.g. English X-self – but more about this directly);

(iv) they have an option of taking a discourse role (instead of a subject) as antecedent, i.e. they can be ‘logophorically bound’; in which case, they may appear to have no antecedent in the sentence or to have a non-c-commanding antecedent.

Local anaphors, which we can also perhaps refer to as ‘theta-deficit anaphors’, are forms which contain (or consist of) an element in a θ-position, which shares the θ-role of an element ‘higher up’. It is this element which makes these forms anaphors. (For example, each other contains such an element, and a ‘floated’ each or X-self is such an element.) By assuming the existence of a principle which forces this element to adjoin to the antecedent in LF by SPEC-to-SPEC movement (rather than, say, adjunction to maximal categories), we showed that the SSC effect exhibited by these anaphors can be derived (and does not have to be stipulated).

Local anaphors show the following configuration of properties:

(ii) they cannot take split antecedents;

(iii) they are not subject-oriented; and

(iv) they cannot be logophorically bound.

Of the properties we have noted as associated with ‘feature-deficit’ anaphors and local anaphors, we have explained the SSC effect shown by local anaphors and the fact that local anaphors cannot take split antecedents.

We have offered no account of the subject-orientation of ‘feature-deficit’ anaphors, nor of the fact that these anaphors can be logophorically bound. But we wish to note the following. It is well-known that the English reflexive does not show any subject-orientation. It contrasts in this respect with the other reflexive anaphors that we have considered. Casting about for a reason for this difference, we can note that in [pro X-self], the missing features of pro are locally identified by X-self; whereas in all the other cases, the focus-marker is an invariant form. It would appear that subject-orientation should fall out from the feature-seeking strategies of a pronominal form when it has to look for its missing features further up than its ‘strictly local’ neighbourhood.54

The option of logophoric binding is not confined to subject-oriented anaphors. Thus the English reflexive, which is not subject-oriented, can be logophorically bound. We suggest that logophoric binding arises (as an option) in the course of a ‘feature-deficit’ anaphor seeking an index (see fn. 37). More explicitly, the contrast between logophoric binding and subject-orientation is the following: a ‘feature-deficit’ anaphor can get an index from any c-commanding DP or from a discourse role (cf. the English reflexive); whereas it can get Φ-features only from a subject (a ‘semi-Topic’) or from a discourse role (cf. Japanese zibun).

A yet unanswered question (among many) that arises out of our new proposals is how these proposals relate to a great deal of current research into long-distance anaphora. It has been claimed (e.g.) that there is a correlation between an anaphor’s being a local anaphor and its morphological complexity: specifically, that a complex anaphor is invariably local, and long-distance binding is possible only for simple anaphors (Yang 1983, Pica 1987, Cole et al. 1990). This claim will obviously have to be abandoned.

Taking off from the above claim, it has been further claimed that a morphologicaly simple anaphor must adjoin to INFL at LF, and that by INFL-to-INFL movement, it can go up into higher clauses. Two things are sought to be explained by such a movement: long-distance binding and subject-orientation. (See Pica 1987 and Cole et al. 1990 for details.) This claim can perhaps be maintained if we say that, in complex forms such as taantanne or zibun-zisin, it is only the pronominal part (i.e. taan or zibun) which moves up, and not the whole complex form. An alternative (in line with some recent theoretical developments, see Chomsky 1995) would be to say that it is only the relevant features of taan or zibun which move up. The prediction now would be that taan tanne or zibun-zisin can take long-distance antecedents and will be subject-oriented, which are correct predictions.55

* I wish to thank Probal Dasgupta, Anne Zribi-Hertz and Tanya Reinhart for helpful comments on the analysis, and the following for providing (with great patience) grammaticality judgements and useful data: Tetsuya Enokizono, Yamabe Junji, Hiroshi Mito and Hidetake Imeto (Japanese), Sang-Hui Kim and Yong-Tcheol Hong (Korean); also Kyung-Jun Jeon and Shim Bong-Sup for sending me their dissertations on Korean anaphora. A special thanks to R. Amritavalli, for comments both on the analysis and on the writing.

1. A few hints about the transcriptions: /t, n/ are dental; /ñ/ is palatal; /T, D, N, L/ are retroflex; /th, dh, ph, bh/ are aspirated; /k’/ is palatalized; /¯s/ and /S/ are (respectively) palato-alveolar and retroflex; /ž/ is a retroflex frictionless continuant; and /R/ is an alveolar tap.

2. Taan can have a discourse antecedent in precisely the same restricted type of contexts in which the English reflexive X-self can have a discourse antecedent. See Zribi-Hertz (1989) for an account of these contexts (for X-self). Typically, a discourse-bound taan (or X-self) occurs in a discourse describing the thoughts and feelings, or point-of-view, of a protagonist. (These contexts are called ‘logophoric contexts’, see Sells (1987) for a discussion.) The following is an example:

3. I have no account of why the Icelandic or Hindi anaphor is sensitive to Tense Opacity. It may be noted that the long-distance binding in (2) is not logophoric: while ‘the king’ is a possible logophoric antecedent, ‘the army-chief’ (subject of ‘see’) is not. Cf. also (i):

‘The kingi objected to the ministerj pinching self’si,j wife.’

The fact that the Malayalam verb has no agreement morphology does not seem to be relevant to the binding possibilities in (2). Tamil, Telugu and Kannada (sister languages of the Dravidian family) have rich morphologies of subject-verb agreement and yet permit long-distance binding, cf.

4. The inadmissibility of ‘Sita’ as an antecedent of taan in (4a) and (5a) will be explained presently.

5. The Chinese reflexive ziji also (like taan) allows a genitive within a subject DP to be its antecedent (Tang 1989); but the parallelism seems to stop there. In the Chinese case, the only constraint seems to be that the subject DP be inanimate and therefore not a possible antecedent of ziji (the latter being [+animate]). Cf.

The parallel Malayalam sentence is ungrammatical:

Interestingly, the Chinese facts can be replicated in English, cf.

We come back to the English data in Section 3.

6. Data involving interaction of psych verbs and anaphors (like (5) or (7)) have been sought to be dealt with in two alternative ways: by proposing that at another level of representation, the Experiencer DP c-commands the subject DP (Belletti & Rizzi 1988); and by the suggestion that the anaphor-antecedent relation is determined by a hierarchy of θ-roles (Jackendoff 1972, Wilkins 1988, Engdahl 1989).

7. Taan shows blocking effects also if it is conjoined with a non-third person DP, cf. (i); or if there is any non-third person DP (even a non-subject) in the minimal clause, cf. (ii):

Apparently, blocking effects (at least in Malayalam) have nothing specifically to do with intervening subjects.

8. This of course is a false test, as will repeatedly appear in the course of this paper. (Incidentally, note that the possibility of split antecedents is not confined to a logophoric interpretation, cf. (9a).)

9. There are speakers for whom a sentence like (10a) is not totally unacceptable. For other speakers – e.g. the present author and K. P. Mohanan – the sentence is definitely bad. There is a similar variation in speaker judgements with respect to Japanese zibun and Korean caki. We come back to this question later.

10. Incidentally, taan obeys Principle B when it is the subject of an ECM construction:

11. Burzio claims that anaphors lack all Φ-features. But this does not seem to be necessary; the crucial feature whose absence makes a nominal element obligatorily require an antecedent, could be the person feature.

12. The focus marker tanne is homophonous with the accusative form of taan, as the reader may have noticed.

13. Our last observation may lead some readers to suppose that we could be actually dealing with two homophonous pairs of forms: a taantanne / avantanne which is just a contrastively focused pronominal (which is stressed), and a taantanne / avantanne which is a ‘true’ reflexive (which is unstressed). Currently this is the position often taken about English himself in (i) and (ii):

The himself in (i) is claimed to be the ‘true’ reflexive which obeys Principle A, and which bears normal stress; the himself in (ii) is said to be ‘another’ element –a contrastively stressed pronominal. We shall come upon a similar attempt to distinguish between reflexive and ‘emphatic’ seg selv in Norwegian, in §2.4 below; and to distinguish between reflexive and ‘intensifying’ ziji in Chinese, in §2.3. At this point we will only say that the stress facts in Malayalam will not bear out a distinction along these lines. Actually, taantanne / avantanne can be unstressed only when it corefers with the minimal subject; avantanne is stressed if it corefers with a non-subject even within the minimal clause:

The degree of stress on avantanne in (iii) is the same as on taantanne / avantanne in (19) where this form takes a long-distance antecedent. But observe now that the sentences in (iii) are ‘true’ reflexive contexts since a simple pronoun (a ‘bare’ avan) will be inadmissible in these sentences. One may also point out that the sense of contrastive focus (‘emphasis’) which is felt in (19) or (18b), is also felt in the sentences of (iii); so it appears that what native speakers interpret as the ‘emphatic meaning’ is simply the presence of stress. In other words, the reflexive function may coexist with stress and the (so-called) ‘emphatic meaning’; and therefore, there is no non-circular way of distinguishing between a reflexive anaphor taantanne / avantanne and a contrastively focused pronominal taantanne / avantanne. (The untenability of this position is further shown up by the fact that the putative contrastively focused pronominal taantanne will still require a c-commanding subject antecedent and will exhibit blocking effects – just like its putative reflexive ‘double’!)

Incidentally, the long-distance binding of taantanne / avantanne has nothing to do with a logophoric interpretation, cf.

14. It may be the case that ‘reflexivization’ is a fully productive, syntactic process in all languages; and that the reflexive forms of a particular language appear to be a closed set only because the input to the rule, namely the pronominal forms of the language, are a closed set.

15. One clarification may be in order regarding (26). The focused element occupying the SPEC position of the DP* in this structure is shown as a DP. But in two earlier examples (20a) and (20b), as also in (iiib) in fn. 13, the reader may have noticed that the focused element is apparently a PP. In (i) below, an adverbial is seemingly focused, and in (ii), a tensed embedded clause is focused:

Should the structure therefore be stated more generally as (iii), where XP can be any maximal category?

We do not think so. Note (firstly) that in English too, X-self may focus CPs as well as DPs.

(These two categories pattern together in many respects.) However, X-self cannot focus an adverbial:

But Malayalam appooL, though functionally adverbial, may be categorially a DP: it literally means ‘that time’. Similarly, Malayalam postpositions, like patti ‘about’ or koNDə ‘with’, are non-finite forms of verbal roots; so that what translates as PPs may be categorially clausal. We suggest (therefore) that the SPEC position of DP* in (26) should be restricted to DPs and CPs.

16. Given later developments in the theory, specifically Chomsky (1992), we can restate this as (i):

Although we continue to use (for convenience) notions like ‘govern’ and ‘CFC’, nothing crucial depends on this.

17. Let us address a tangential question here: if tanne carries a meaning of contrastive focus, how could it ‘lose’ this meaning when it functions merely as a ‘reflexivizer’ in sentences like (17)? Since the same question can be posed about English X-self, we shall discuss the question in terms of English data.

English has two devices for marking contrastive focus, namely simple stress and X-self; and they have distinct functions. When we have a mentally present list, say ‘A, B, C and D’ – in a list, all members are of equal ‘rank’ – and we wish to pick out one member, say ‘A’, we can use only simple stress not X-self. Cf.

On the other hand, when we have A as the ‘centre’, and perceive B, C and D as related to it – i.e. when we have a ‘centre-and-periphery’ structure –, and wish to pick out A, we use X-self; although simple stress is also often possible since one can think of the elements of a hierarchical structure also as a list. Thus, cf.

(Possibly this ‘centre-and-periphery’ structure which X-self presupposes, is related to Zribi-Hertz’s 1989 idea that X-self is an anaphor which refers to a ‘subject-of-consciousness’. See also Baker’s 1995 notion of ‘discourse prominence’.)

In typical reflexive contexts like those illustrated in (iii):

‘John’ is (conceivably) seen as the ‘centre’ of a domain of individuals consisting of ‘John’ and people connected with ‘John’. (I.e. (iiia), for example, is saying that ‘John’ loves ‘John’, as opposed to people in John’s world.) Thus it may not be the case that X-self (or, by analogy, tanne) no longer has the meaning of contrastive focus in reflexive contexts. In fact, in a sentence like (iv) where X-self is normally stressed in a neutral reading:

we do intuit a meaning of contrastive focus. (Incidentally, (iv) shows that in English too – like in Malayalam, see fn. 13 – stress and the meaning of contrastive focus may coexist with the reflexive function.)

18. As with taan, there is a variation in speaker judgement about zibun.

Ueda (1984) and Fukui (1984) try to analyze zibun as a pure pronominal, basing their claim on the evidence that it shows principle B effects. Fukui also points out that its plural can take split antecedents, a fact which we illustrate directly. (Fukui also considers the alternative that zibun is specified with the feature [pronominal] and [anaphor] disjunctively, i.e. as [+pronominal or +anaphor].)

‘Feature-deficit’ anaphors generally seem to induce weak (or variable) Principle B effects, whereas ‘feature-saturated’ pronouns like avan and kare show very definite Principle B effects which do not vary between speakers. We can suggest a functional explanation: avan/kare can take a discourse antecedent, but taan/zibun cannot (except in logophoric contexts). Now, given a sentence like (31), some speakers seem to be able to ‘suppress’ the Principle B effect in the interests of giving the sentence an interpretaton. They do not have to suppress the Principle B effect in a parallel sentence with kare because the pronoun can be given a free reading.

Two arguments seem to support this suggestion. Fukui (1984) claims to find a weaker Principle B effect with zibun in a simplex sentence (such as our (31)) than when zibun is in an embedded clause. (In the latter case, zibun has the possibility of an ‘alternative antecedent’, namely the matrix subject.) We have noted a similar effect in Malayalam, cf. our discussion of (15). Secondly, for those Malayalam speakers who have a weak (or nonexistent) Principle B effect with taan, first and second person pronouns also show a weak Principle B effect. Thus (ia) and (ib) are not totally unacceptable for them, and contrast sharply with (ic) – the reason being that a first/second person pronoun has no reading which is non-coreferential with another first/second person pronoun in the sentence, whereas a third person pronoun always has a free reading available.

Taan, and also repeated proper names, seem to pattern with first and second person pronouns for these speakers.

It is not merely the Principle B effect that (some) speakers can ‘suppress’ in the interests of giving a sentence an interpretation. Maling (1986) notes that even speakers who normally reject a non-subject antecedent for Icelandic reflexive sig, tend to accept it in the following sentence:

Here the subject cannot be the antecedent of sig, because sig is 3rd person; so ‘Harold’ is chosen as the antecedent, suppressing the subject-antecedent condition.

19. Zibun and zisin are related words, like taan and tanne are related words. Zi(bun) is a form which means ‘self’; and zisin is underlyingly zi (‘self’) + sin (‘body’). (Information provided by Tetsuya Enokizono.)

20. Kare is different from Malayalam avan (‘he’) only in that it cannot be bound by a quantifier (Saito & Hoji 1983). In contrast, avan can be bound by a quantifier:

21. Is (41) ‘saved’ only by a logophoric interpretation? See – with regard to this question – fn. 13 (last paragraph) for a comment on the parallel Malayalam data: also see fn. 44 (below) for a more basic argument about logophoric interpretation in general.

22. Caki/casin is exactly parallel to zibun/zisin: ca(ki) means ‘self’, and casin is ca (‘self’) + sin (‘body’).

23. As in the case of taan and zibun, there is variation in speaker judgement about the Principle B effects induced by caki. One of my Korean informants, Sang-Hui Kim, felt that when the subject was marked for Topic as in (45), caki was infelicitous, and caki-casin or casin was only ‘slightly better’; but that if the subject was nominative (i.e. ‘John-ka’ instead of ‘John-un’ in (45)), caki and the other two forms were all fine. Jeon (1989:90, 92) cites the following sentence as grammatical:

But it is significant that the same author finds the following sentences also fine:

See fn. 18 for a suggested explanation.

24. As independently suggested by Sang-Hui Kim (p.c.).

25. Tang (1989) analyses (incorrectly, we think) floated ziji as an adverbial, and generates it in an Ā-position. (We shall give our account of floated focus-markers when we deal with English reflexives.)

26. Tang (1989) intends her analysis (of ‘bare’ ziji as ‘pro-ziji’) to apply only to anaphoric ziji, not ‘intensifying’ ziji; but since we do not recognize this distinction, we shall extend this analysis to all ‘bare’ ziji.

Tang offers three arguments in support of the aforesaid distinction. One: anaphoric ziji is generated in an A-position, ‘intensifying’ ziji in an Ā-position. Her evidence however is based on ‘floated’ ziji which she analyzes as an adverbial, cf. (51). Two: intensifying ziji may be attached to any DP, but anaphoric ziji may have only an animate antecedent, cf. (i) and (ii) (adapted from Tang’s (18) and (14)):

But the animacy condition could be a property of Chinese pro: note that there is pro-ziji only in (ii), not (i). Three: the pronoun preceding the anaphoric ziji is necessarily bound, but the pronoun preceding the intensifying ziji could be free; thus a sentence like (iii) (=Tang’s (23)) is ambiguous between the two readings, (a) and (b), depending on whether ziji is anaphoric or intensifying:

This argument is circular.

27. In Icelandic, there is apparently some variation in speaker judgement: some speakers tend to accept a non-subject antecedent if it is within the minimal clause (see Maling 1986).

28. The non-local binding condition on sig has been noted in Taraldsen (1983), Vikner (1985), Hellan (1986). The claim that sig can be also locally bound (Anderson 1983; Hyams & Sigurjónsdóttir 1990) is disputed by Hestvik (1990), who shows at some length that the putative cases of local binding are instances of ‘lexical reflexivization,’ a process associated with a restricted set of verbs.

29. Selv can ‘float’, cf. (i); and when it does, its relation to its antecedent is subject to SSC, cf. (ii):

We shall explain this SSC effect seen here, when we deal with ‘floated’ X-self in English. (Hestvik 1990:203 takes the SSC effect to be an inherent property of selv – a wrong claim, we think.)

30. After writing this paper, we came across the same explanation for seg selv in Hestvik (1990:201). Hestvik (however) claims that the complex forms seg selv and ham selv are local anaphors, explaining the locality condition as an inherent property of selv.

31. Hellan (1988) gives three reasons for keeping apart the anaphoric selv from the ‘emphatic’ selv. One: the emphatic selv requires stress. Two: the emphatic selv is ‘accompanied by some sort of contrastive or focal interpretation.’ Three: the anaphoric selv (unstressed, non-focalizing) occurs in all and only the contexts where its presence is needed to obtain a bound reading (i.e., in our terms, to save a pronoun from a Principle B violation). With regard to the first two arguments, see fns. 13 and 17. Regarding the third argument, the observation is not true at least of English X-self and Malayalam tanne, see (again) fns. 13 and 17: what we actually find is an overlap, with many cases of X-self/tanne which are both stressed and needed for a pronoun to have a bound reading.

32. The trouble with calling it simply an ‘emphatic pronoun’ is that it (too) seems to require a c-commanding antecedent, cf.

33. Note that this explanation also applies to the ‘floated’ selv of Norwegian cited by Hestvik (1990), and that (therefore) the SSC effect shown by it cannot be argued to be an inherent property of selv (as Hestvik claims, see fn. 29).

One may well ask: What is the structure of the ‘floated’ X-self? In view of our explanation, this could possibly be [t X-self], where t is the trace of the subject which has moved further up.

(We must admit that our explanation is unable (by itself) to account for the occurrence of ‘floated’ X-self in the right peripheral position of VP.)

34. This fact has been noted in Bickerton (1987).

35. (81) is admittedly not an explanation; it is only a formalization of an observation. But all that is relevant for our purposes is the fact that the configuration shown in (81) is illicit (or not preferred), not why it is illicit (or not preferred).

36. A (popular) alternative analysis of himself as [[him] self] is shown to be inadequate in fn. 40 below.

37. It appears that pro – or ‘feature-deficit’ pronominal forms generally – need to get an index and to have their missing features identified. Thus Chinese pro-ziji, according to Huang & Tang (1989, 1991), gets its features identified by the minimal subject but must still get an index, which it can get either from the minimal subject or from a higher subject. (The aforesaid index may apparently also be provided by a discourse role – ‘logophoric binding’; and this permits even a discourse antecedent or a non-c-commanding antecedent.)

38. The question arises: why cannot ‘pro X-self’ occur as the subject of a tensed clause? In (i), at least when ‘pro himself’ is an embedded subject, both pro’s feature-identification requirement and its requirement of an index from a c-commanding antecedent are met:

But note that in nominative positions other than the subject position of a tensed clause, pro and lexical NP do indeed alternate:

(i) is then disallowed for some independent reason. Mahto (1989) has suggested that sentences like (i) are ruled out because pro in non-pro-drop languages cannot trigger agreement (which can now be restated as: pro in these languages cannot be checked by AGR). (See Mahto 1989 for details.)

39. There are also superficial differences between these languages: the English pronominal in the complex reflexive form is invariably pro; the Malayalam and Japanese pronominal is invariably lexical; and Korean and Chinese allow both possibilities. The differences are partially explained if we say that only English has filter (81) (which is what makes a lexical pronoun impossible in English); so the other languages have the possibility of a lexical pronoun. (This still does not explain why Japanese and Malayalam cannot have a pro in this context.)

40. Our account of the English reflexive may be charged with ignoring its morphology: ‘pronoun-self’. In fact, one of the earliest studies of the reflexive, Helke (1971), suggested the following structure:

(Helke further suggested that the place of the pronoun could be occupied by an empty feature-matrix in deep structure, which is filled by feature-copying from the antecedent.) This analysis has had a lot of influence, partly because of the parallel reflexive forms in related European languages, e.g.

where the complex reflexive is formed by simply adding a cognate of self to a pronominal form. If we were to go along with this analysis and adapt it, the structure of the English reflexive could be (ii) (instead of (83)):

A closer look (however) shows that this analysis has many disadvantages. We have seen that in language after language, the complex reflexive is formed by adding the language’s normal focus marker to a pronoun. In Norwegian the focus marker is selv, and in Dutch it is zelf; but in English it is himself:

Adopting (ii) would in fact make English an exception to the way in which many languages, including the related European languages, make their complex reflexives.

Also, note that (in any case) we need the structure (71) to represent a phrase like John himself. Now, whereas (71) and (83) are the same structure, leading to a generalization, (ii) is different. So we end up with at least two himselfs in the language – a type of proliferation we have been trying to avoid.

(ii) also does not explain why himself is an anaphor, since it does not contain a ‘feature-deficit’ pronoun.

Again, (ii) does not fill the ‘gap in the paradigm’ that we pointed out.

41. Examples (87b) and (87c) are from Zribi-Hertz (1989), who also gives some ‘found examples’.

There are constraints on split antecedents which need to be investigated. Consider the following sentences:

The condition here seems to be that either both antecedents should be within the minimal clause, or both should be outside it. The following sentence suggests that both antecedents should c-command the anaphor:

42. Both these examples are ‘found examples’: (88) is from a popular magazine (Span, September 1987), (89) from David Lodge: Changing Places, Penguin, 1975, p. 170 (cited by Zribi-Hertz 1989). The logophoric binding of X-self has been extensively documented, see Cantrall (1974), Kuno (1972, 1983, 1987), Zribi-Hertz (1989) and Reinhart & Reuland (1991).

43. (90a) is from Christopher Isherwood: Mr. Norris Changes Trains, Methuen Paperbacks reprint, 1987, p. 132 (cited by Zribi-Hertz 1989). (90b) and (90c) are repeated from fn. 5.

44. It has been customary to say that ‘reflexive’ binding of X-self – and of complex reflexives generally – is indeed well-behaved with respect to Principle A; problematic cases are instances of either logophoric binding or focus binding. A recent attempt to firm up this approach has been the claim that logophoric and reflexive binding can be kept apart in terms of their syntactic environments: logophoric binding is an option only when the reflexive form is not an argument – or at least, not an argument of a ‘full’ predicate with a subject; see Pollard & Sag (1992), Reinhart & Reuland (1991, 1993). Thus Reinhart & Reuland (1993) analyze (i)–(iii), which they consider instances of logophoric binding, as follows: logophoric binding is permitted here because in (i), X-self is a proper subpart of an argument; in (ii), it is in an adjunct; and in (iii), the relevant predicate is not a ‘full’ predicate.

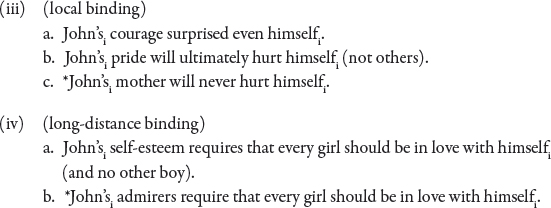

This claim (however) cannot be sustained; we have seen many examples of Malayalam taan in argument positions which are logophorically bound, see (4), (5) and fn. 2 above. See also (90b), where himself is an argument of a ‘full’ predicate: but both the non-c-commanding antecedent and the sensitiveness of the coreference interpretation to the animacy feature of the subject DP’s head-noun (cf. *John’s mother will never harm himself) argue that this is a case of logophoric binding.