I

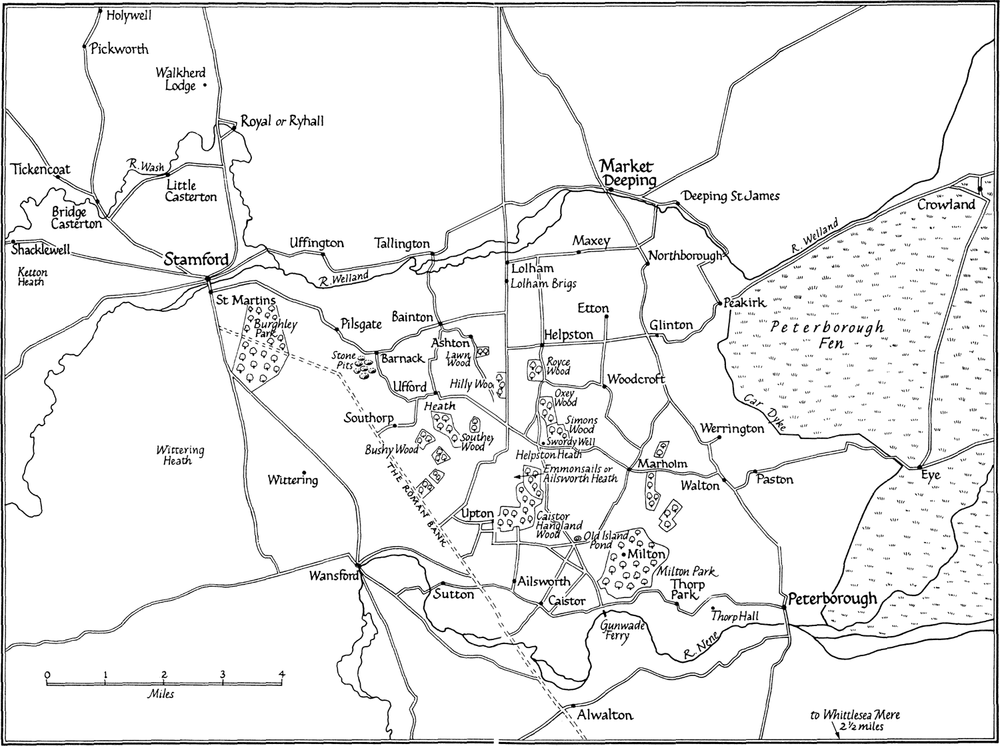

From his birth in Helpston in 1793 to his death in Northampton in 1864, except for four visits to London, some months in Epping Forest and his years in the Northampton General Lunatic Asylum, John Clare never travelled more than a few miles from his native village. He lived at first under the same roof as his parents in Helpston, moved to another cottage in Northborough only a few miles away in 1832, and then from 1841 spent the remainder of his life in Northampton.

Clare’s life-story is told against the background of a particular landscape with its fens, its heaths, its sheep-pastures and its villages and market-towns. (It is significant that Clare uses the word ‘town’ to denote any settlement, however small.) He talks of Will-o’-the-wisps (or Jenny burnt-arses), of ghosts and poachers, of spires peeping over stiles, of bird-haunted thickets, of lonely farms, and of the threshers, gleaners and weeders in his native fields. The skies of the Fens always overshadowed him, and there is no writer from whom one gets a better sense of an unbroken horizon or of the scarlet flames of sunset and sunrise. In this landscape he breathed freely: once he left it, he felt suffocated and began to lose touch with reality. He speaks constantly of the ‘lordship’, the area under the control of the lord of the manor, or of his ‘world’, the locality with which he was familiar. It is not uncommon to this day to find on the edge of English towns a pub called ‘The World’s End’, as though when one reached the boundary of a familiar settlement one dropped over the edge of the horizon. Clare’s sense of identity is intimately involved with his awareness of his birthplace and of all the living things that he remarked within his locality:

I lovd the meadow lake with its fl[a]gs and long purples crowding the waters edge I listend with delights to hear the wind whisper among the feather topt reeds and to see the taper bulrush nodding in gentle curves to the rippling water and I watchd with delight on haymaking evenings the setting sun drop behind the brigs and peep again thro the half circle of the arches as if he longs to stay1

The Tibbles, in their edition of Clare’s prose, speak of the ‘Sketches’ as

the enchanting account of a vanished English childhood and youth, far away from, while yet contemporary with, the French terror and the Napoleonic Wars … an account of a country childhood during one of the hardest periods of Enclosure, when rustic activities and customs, now swept away for ever, were still in full swing.2

In fact the Terror, the Napoleonic Wars, and even Enclosure are so far removed from Clare’s preoccupations that they only appear on the scene as part of a local experience — in the POW camp at Norman Cross, in the strange antics of the militia, and in the inconvenience of fences. This is the world seen through the wrong end of the telescope but filled with its own strange intensity. In the London episodes, the great wander across the scene — Lamb, Coleridge, Hazlitt, Reynolds, Sir Thomas Lawrence and others — or Byron, Clare’s hero, is seen through the eyes of a poor sailor, but most of the characters are purely local. Granny Bains, John Cue of Ufford, old Shepherd Newman, John Billings, George Cousins: these are people who but for Clare would have been entirely forgotten. They and their countryside become the setting for Clare’s Paradise.

He tells us much about the people — of the hardships suffered by poor men, their humiliations and their sense of oppression, but also of their joys, their festivities and their songs. Sometimes, as in his ‘Apology for the Poor’, one hears his honest anger:

now if the poor mans chance at these meetings is any thing better then being a sort of foot cushion for the benefit of others I shall be exceedingly happy to hear but as it is I much fear it as the poor mans lot seems to have been so long remembered as to be entirely forgotten

or when he speaks of one rude visitor:

he then asked me some insulting libertys respecting my first acquaintance with Patty and said he understood that in this country the lower orders made their courtship in barns and pig styes and asked wether I did I felt very vext and said that it might be the custom of high orders for aught I knew as experience made fools wise in most matters but I assured him he was very wrong respecting that custom among the lower orders here3

Since Piers Plowman there has hardly been an authoritative voice in English literature to speak for the ploughmen, the threshers, the hedgers, shepherds, woodmen and horse-keepers, until Clare began to write. Robert Bloomfield is perhaps the nearest. The farmer-journalist William Cobbett is heard loud and clear, and so, at a later date, is the gamekeeper Richard Jefferies. Joseph Ashby of Tysoe is nearer to Clare in social status, but none of these is his equal. As Edmund Blunden said, Clare’s autobiographical writings contain

fresh information on the early life and thoughts of a poet of the purest kind: originality of judgment, bold honesty; illuminating and otherwise unobtainable observations on intimate village life in England between 1793 and 1821; a good narrative — nearly as good as Bunyan — and plenty of picturesque expression. It will be a long time before a voice again speaks from a cottage window with this power over ideas and over language.4

The people of Clare’s autobiography — Will Farrow, the cobbler; Hopkinson, one of that increasing number of clerical magistrates who posed a special problem on the bench by their mixing of law and morality; Henson the bookseller and Ranter-preacher; the servants at Milton; the head-gardener at Burghley; the boy, John Turnill — are as lively and individualized as characters from The Canterbury Tales, of which Clare was a great admirer. And when we move from individuals to meetings, ceremonies and occasions such as religious holidays, singing and dancing with the gypsies, drilling with the militia or walking Vauxhall Gardens in London, there too all is light and colour, and we may well agree that ‘the year was crowned with holidays’.

Clare transformed the people and the fields they roamed by suffusing them with the glow of childhood — for Clare’s autobiography is as remarkable a vision of childhood as the poems of Blake and Traherne. It is a deliberate vision of Eden before the Fall and a realistic appraisal of Eden after it. The ‘Sketches’ are mostly representative of the former vision and the ‘Autobiographical fragments’ increasingly reflect the latter as Clare’s disenchantment grew over the years. The ‘Autobiographical fragments’ are much more openly critical of the middle classes, revealing Clare’s aversion to simpering misses and pompous magistrates, to pretentious militia officers and grasping farmers, to overbearing surveyors and interfering ministers.

Like other authors in the same vein, Clare’s language often has a strong proverbial quality: ‘I was quite in the suds’; ‘Send him to Norberrey hedge corner to hear the wooden cuckoo sing’; ‘I was in that mixd multitude calld the batallion which they nick namd “bum tools” for what reason I cannot tell the light Company was calld “light bobs” and the granadeirs “bacon bolters”’; ‘I was now wearing into the sunshine’; ‘Another impertinent fellow of the Name of Ryde who occupys a situation which proves the old Farmers assertion that the vilest weeds are always found in the richest soil’. Indeed the same forcefulness of language runs throughout Clare’s prose as one finds in the newspapers and almanacs of the day.

We ought to recognize, moreover, that Clare’s autobiography belongs to that tradition of those sixpenny chapbooks hawked from door to door which shaped his childhood imagination. Clare is the hero of his own chapbook: he is his own Tom Hickathrift, Jack and the Beanstalk, or Dick Whittington making his way to London, that sink of iniquity or crucible of success. He was quite aware of the strangeness of his own rise to fame. Other tales of men and women rising from obscurity were part of folk-tradition. Even when totally fictional, they were presented as true-life stories: Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels, Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe and Gay’s Beggar’s Opera all belong to the tradition of marvellous lives and adventures, along with the memoirs of James Lackington, the Methodist bookseller. The newspapers were full of extracts from works such as these and they provided vigorous models for young working-men. Clare’s autobiographical writings are at least partly in the tradition of the poor boy’s rise from obscurity to fame, or at least to notoriety: the boy practising his writing on a slate, or having his poems — written on grocer’s paper — used by his mother to light the stove. Clare was even more deeply entrenched in the idiom than Defoe, Gay and Swift because for many years the chapbooks were almost his sole literary diet. His imagination was nourished by the popular songs and stories that have always fed the minds of the poor and compensated them for their deprivations with a rich world of fantasy. Clare’s dreams were made from tales of knight-errantry, the adventures of Robin Hood, the story of Joseph and even the true stories of Chatterton, Kirke White and Bloomfield.

At all times of his life, sane or insane, Clare identified himself with some hero. In his insane years he seems to have been unable to keep fact and fiction apart: was he Clare or was he Byron, or Burns, or Shakespeare? Was he Nelson or was he Ben Caunt, the prize-fighter? His life always had its elements of fantasy: did he really drub a bullying corporal in the army, or was it merely that he would have liked to do so? Is he not a bit like the farm-boy in his verse-tale, ‘The Lodge House’? Were the amorous advances he thought were made to him by the governess at Birch Reynardson’s house any more real than the mind-games he played with Eliza Emmerson or Mary Howitt? What conflicts arose within him when he saw that his fantasies of fame and fortune were never to be realized? If our disappointments as editors in our struggles to obtain full recognition for him are bitter, how much greater his own must have been!

Clare wanted to believe in his own special destiny, to feel that he had been marked out by fate. Was not his providential birth and survival to be contrasted with the death of his twin sister, who had seemed to be more robust? Was it not for some great reason that he was twice saved from drowning and preserved from a dangerous fall when he was birds-nesting? Why was it that he was not buried in the collapse of a barn in which he and his fellows, only a few hours before, had been carousing? The resemblances to other providential escapes related in religious biographies are very clear.

During his visits to London, Clare is fascinated by kidnappers, cheats and ladies of the town. He enjoys the frisson of the tale of Sweeney Todd. Later, as he sets out on his walk from Essex, he presents himself as a general marshalling his forces. At Northampton he sees himself as Burns or as Byron. Fantasy was a deeply imbedded aspect of his nature. It is not that he tells lies, but that he views the truth in a peculiar light. He chops and changes throughout his life in his attitude to public affairs and it is often impossible to nail him down.

In the ‘Sketches’, Clare is presenting his life-story to his publisher, John Taylor, and to his patrons, all of whom were imbued to a greater or lesser degree with the evangelicalism of the time. They wanted to assist a talented member of the deserving poor, someone honest, sober and hardworking; Christian — preferably Anglican — and critical of popular superstition; patriotic and law-abiding; a decent family man with acceptable sexual habits; respectful and grateful. Clare therefore presents himself as a model for Hogarth’s industrious Apprentice:

I resignd myself willingly to the hardest toils and tho one of the weakest was stubbor[n] and stomachful and never flinched from the roughest labour by that means I always secured the favour of my masters and escaped the ignominy that brands the name of idleness …5

He spends all his free time improving his handwriting and working out problems in ‘Pounds, Shillings and Pence’. All his efforts are directed towards the repayment of his parents. He says little about his unreadiness for starting work. (More of that story is to be found in the ‘Autobiographical fragments’.) He admits to escaping from church on Sundays but has suggestions to make about the way in which the Scriptures should be taught to children. In general, he is a much more conforming character in the ‘Sketches’ than he was in real life. In the ‘Sketches’ he defends himself from the suggestion that the Billings brothers were poachers, whereas in the ‘Autobiographical fragments’ he tells a story of a miraculous escape from the explosion of a flintlock on a poaching expedition.

There is no question that Clare is trying to present himself in a good light while revealing as much about himself as he safely can. He does confess to drinking too much and having too many flirtations, however he ends by saying that ‘mercey spared me to be schoold by experience who learnd me better’.6 It is doubtful whether Clare often spoke that way to his cronies. In his letters, even those to Taylor, he is often more open. All this adds to, rather than detracts from, the interest of his memoirs. We see that we are dealing with a complex character.

II

There have been several biographies of John Clare, but none that is entirely satisfactory. The problem with most is that their writers were not deeply enough read in Clare’s own manuscripts. The Oxford English Text edition of his collected poetry is nearing completion, in nine volumes. There is no collected edition of Clare’s prose, and the Tibble selections are unreliable, but Margaret Grainger’s The Natural History Prose Writings of John Clare (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1983) is a first-rate edition of those pieces she has included. Mark Storey’s The Letters of John Clare (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1985) is the standard edition of Clare’s outgoing letters. No one has tackled the mass of incoming correspondence. It is not surprising, therefore, that biographers have been handicapped by the lack of printed sources.

The first biography of Clare was Frederick Martin’s The Life of John Clare (London and Cambridge, 1865; second edition, eds E. Robinson and G. Summerfield, 1964), a lively, emotional but unreliable account, which nevertheless used original sources. There is evidence in J.L. Cherry’s Life and Remains of John Clare the ‘Northamptonshire Peasant Poet’ (London and Northampton, 1873) that the author had access to original Clare manuscripts. He refers on page 9 to ‘a few undecipherable lines commencing “Good morning to ye, ballad-singing thrush”’ written in an arithmetical and geometrical exercise-book which is now Northampton MS 11. Cherry also quotes extensively from Clare’s ‘Journal’ and letters to and from him. But the best biography is still J.W. and Anne Tibble’s John Clare: A Life (1932), which deserves to be reissued. A subsequent volume by the same authors, John Clare: His Life and Poetry (1956), adds new information but is less successful as a whole and is, in general, a rather strange mixture of biography and criticism.7 What always brings these biographies to life is the quotations from Clare’s own autobiographical statements, reflective or satirical, nostalgic or ironic, contemplative or indignant.

III

Clare had the idea of collecting facts for his life-story very early on. He wrote to J.A. Hessey (John Taylor’s publishing partner) on 29 June 1820:

— I mean to leave Taylor the trouble of writing my Life merely to stop the mouths of others — & for that purpose shall collect a great many facts which I shall send when death brings in his bill—8

At the time, he was composing his will. Keats, as Clare learned from Taylor, was seriously ill. Some of Clare’s Helpston friends were dying off. He never thought that he himself would make old bones. Yet at the same time he was getting his first experience of fame — his first volume, Poems Descriptive of Rural life and Scenery, had been published in January 1820. Lord Radstock had become his patron, the local gentry were making him ‘the stranger’s poppet Show’, and he was enquiring from Captain Sherwill whether he knew Wordsworth and Coleridge personally,9 asking Taylor to give his regards to Keats,10 and reporting to Taylor that his fellow regional poets, Robert Bloomfield and James Montgomery, were recognizing him, and had ‘written me & praisd me sky high & added not a little to my vanity I assure ye’.11 Local rivals such as Ann Adcock, S. Messing and Edward Preston were springing up.12 How long would he stay ahead of them? The newspapers were stuffed with the poems of unknown writers, some of them awful, others not half-bad. Meanwhile his publishers, Edward Drury of Stamford and John Taylor, were bickering about their rights in him; Lord Radstock and Mrs Emmerson, his evangelical patrons, were trying to censor him; and his village friends were beginning to regard him with suspicion. He was anxious to have his true story set down on paper, even if he intended to leave it to Taylor to write the finished biography after his death. Several of his patrons seemed anxious to build their own fame on his pitiful scaffolding.

Clare was not the shrinking violet he has sometimes been thought to be. As many of his early poems reveal, he was preoccupied with fame in general and his own in particular. It may be local fame — that of the young soldier who goes off to the wars, or of the boxer or wrestler who wins a bout at the local fair, or of a village schoolmaster or schoolmistress — or the fame of Shakespeare, Byron or Keats. It may be the fame of a place or monument — the River Welland, Burthorp Oak or St Guthlac’s Stone; even the false fame of the Revd Mr Twopenny or of a quack doctor.13 Clare’s greatest fear was obscurity, and it was to ‘Obscurity’ that, ‘in a fit of Despondency’, he wrote one of his earliest sonnets.14 He did not wish to vanish from the records like old Shepherd Newman or the Ruins of Pickworth. His own aspirations are wittily expressed in ‘The Authors Address to his Book’, in which he sees himself and his book, like fellow vagrants and beggars, tramping towards their destiny:

No never be asham’d to own it

For better folks than I have known it

But tell em how thou left him moping

Thro oblivions darkness grouping

Still in its dark corner ryhmeing

& as usual ballad chyming

Wi’ few ha’pence left to speed wi’

Poor & rag’d as beggars need be

— Money would be useful stuff

To the wise a hints enough

Then might we face every weather

Gogging hand in hand together

Tow’rds our Journeys end & aim

That fine place ycleped fame…15

Is there a reference here to Chaucer’s House of Fame? The poem is typical of Clare: though he apologizes for his rough upbringing and lack of education, he has confidence in his own genius and in the fame it will eventually bring him. Whether his fame is in the local pub or on the national scene, he always has his eyes on greater things. In poems such as ‘Dawning of Genius’, ‘Some Account of my Kin, my Tallents and Myself’, ‘In shades obscure & gloomy warmd to sing’16 and many more, Clare returns to the theme of the rise from obscurity to fame. Much of his autobiographical writing in prose is occupied with the same matters.

IV

By January 1821, Clare was trying his hand at prose. ‘Charicteristic Descriptive Pastorals in prose on rural life & manners’, in the hope of eventually publishing a volume entitled ‘Pastorals in Prose’.17 He was also assembling facts for Taylor to go into the introduction to The Village Minstrel:

I will fill your last ruled Quarto with as much of my little life as

I can & get it done doubtless to bring up with me in summer as

I then intend to storm the hospitality of Fleet St —18

It is not the hospitality of Fleet Street that he intends to storm but the bastions of literary fame. On 8 February 1821 he told Taylor, ‘— I have been getting on with my “Memoirs” & shall have it for your inspection by summer’.19 By 7 March he could promise ‘the “Sketches of my Life” ready for sending you in a fortnight at most’,20 and they were actually sent off on 3 April 1821.21 He promised Taylor sole ownership of the manuscript and that no copies would be provided to anyone else.22

It seems probable, however, that Edward Drury had already seen part of it. Mark Storey has brought to our attention a ‘Memoir’ of Clare in the Bodleian Library (MS Don. d.36), attributed to Hessey but actually by Drury. It is dated ‘May 6. 1819’ and is based on information that clearly formed part of the ‘Sketches’: Clare’s early admiration for Pomfret’s poems, especially the woodcuts; the borrowing of Robinson Crusoe; and the purchase of Thomson’s Seasons.23 The poet’s name is even misspelt ‘Thompson’, as in the ‘Sketches’, suggesting that the information was transmitted in a document rather than orally.

When Taylor received the ‘Sketches’, he thought them the best things he had ever seen from Clare in the prose line,24 and he did use parts of them for his introduction to The Village Minstrel (published in September 1821). The subsequent history of the ‘Sketches’ is a little obscure until they become MS 14 in the Clare collection at the Northampton Central Public Library. Frederick Martin, in the preface to his Life of John Clare, refers to ‘some very curious autobiographical sketches’,25 and it was from his daughter, Miss Louisa Martin, that Edmund Blunden received permission to publish his edition of the ‘Sketches’ in 1931.26 Did Martin also have access to the ‘Autobiographical fragments’? Very probably so, since he speaks of Granny Bains, the ‘old Mary Bains the cow keeper famous for the memory of old customs’, whose existence was later wrongly questioned by the Tibbles.27

It is clear that Clare did not abandon his autobiography after sending off the ‘Sketches’, because he wrote to Taylor on 11 August 1821, ‘I have ideas of writing my Literary Life & continuing it on till I live’.28 In several Clare manuscripts there appear ‘Autobiograhical fragments’ that supplement the ‘Sketches’ in important ways. First of all they continue Clare’s story fragmentarily down to the year 1828. Secondly, they provide pen-portraits of his literary acquaintances in London and describe his visits to the metropolis. They also include much additional material.

Clare wrote to H.F. Cary, the translator of Dante and biographer of Chatterton (one of Clare’s heroes), on 30 December 1824 asking him to read his memoirs and to give his opinion of them.29 Cary replied on 19 February 1825, saying that he would ‘read the memoirs of yourself which you propose sending me; & not fail to tell you, if I think you have spoken of others with more acrimony than you ought.’30 Clare, who was becoming increasingly disenchanted with John Taylor at this time, may have written some critical comments about him, but as The Shepherd’s Calendar was in progress, Clare would not have wanted to imperil its publication. What were these memoirs: a more or less finished version drawn from the ‘Autobiographic fragments’, or the fragments themselves? If Clare were going to submit them to Cary, they would have had to be in a more finished form than they are in now, in the surviving manuscripts. The Tibbles suggest that Clare never sent anything to Cary,31 and certainly we hear no more about them in Cary’s surviving correspondence. Yet even if they were never sent, the fact that many of them are crossed through or marked ‘done for’ suggests that Clare was following his usual practice of writing up a fair copy from his scattered notes.

When Clare wrote to Cary, he spoke of having ‘gotten 8 chapters done’ and having ‘carried it [the Memoirs] up to the publication of the “Poems on rural life &c.”’32 This is clearly a reference to Poems Descriptive of Rural Life and Scenery. Northampton MS 14, on which Blunden’s edition of the ‘Sketches’ is based, shows no chapter divisions. Is Clare therefore referring to an expanded memoir – already planned when he wrote to Taylor back in 1821 – divided by December 1824 into eight chapters? Clare’s Journal shows him at work on the life on 12 and 28 September 1824, and 20 November has the entry: ‘finishd the 8th Chapter of my life’.33 He was finding the task more difficult than he had expected, and he adds:

in the last sketch which I wrote for Taylor I had little vanitys about me to gloss over failing[s] which I shall now take care to lay bare & readers if they ever are published [may] comment upon [them] as they please in my last 4 years I shall give my likes and dis likes of friends & acquaintance as free as I do of my self.

Clare told E.V. Rippingille on 14 May 1826, ‘I have nearly finished my life having brought it down as far as our last visit to London & as soon as its done I think of offering it for sale.’34 We find it difficult to believe that Clare could have contemplated offering for sale anything so fragmentary as the paragraphs we have printed here as ‘Autobiographical fragments’, and it also seems clear that he had improved on the material he had earlier sent to Taylor. It should be noticed, too, that he is proposing to sell this material while he had promised the ‘Sketches’ exclusively to Taylor.

By 1825, as is revealed by partially deleted passages in the Journal, Clare had grown disillusioned with Taylor.35 In the entry for 17 April 1825 he has heavily deleted a reference to ‘the pretending and hypocritical friendship of booksellers’, and there are other entries to similar effect. By the time The Shepherd’s Calendar was published, perhaps he felt that he could not afford to reveal his true feelings about Taylor, and suppressed the new version of his life. We cannot agree with the Tibbles’ suggestion that the ‘Autobiographical fragments’ represent the totality of his autobiographical writings in these years, though they may well be correct in suggesting that he changed his mind about submitting anything to Cary. We therefore agree with Blunden in thinking that Clare probably wrote an extended version of his life, for which the ‘Autobiographical fragments’ are first drafts, but we consider it a possibility that Clare deliberately destroyed the new version.

V

We welcome the opportunity to bring together in one volume some of Clare’s most important autobiographical records, chiefly the Journal, his ‘Sketches’ and the ‘Autobiographical fragments’.

In their Prose of John Clare, the Tibbles reconstructed chapters for Clare’s ‘Autobiography’, and it is certainly true that there are chapter numbers and chapter headings here and there in the manuscripts. Thus there are chapter numbers 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7. Chapter 4 has the heading ‘My first feelings and attempts at poetry’, and chapter 5 is headed ‘My first attempts at poetry’, so that the subject-matter of these two chapters is not clearly differentiated. Chapter 10 is headed ‘My visit to London (I)’ and chapter 11 ‘My visit to London (II)’. It is not clear to us where these chapters begin or end, so we have grouped the ‘autobiographical fragments’ in what appears to us to be the most logical order. To print the fragments in the order in which they appear in the manuscripts, as catalogued by David Powell and Margaret Grainger, would have been confusing. We always indicate in square brackets the location of a passage in the manuscripts. If the MS is from the Peterborough Museum collection, it is preceded by a capital letter, according to the numbering in Dr Grainger’s catalogue. The number after the comma is the page number: [A32, R12], for example, indicates that the material appears upside down on page 12 of Peterborough MS A32. A MS preceded by the letter N denotes that it is to be found in the Northampton collection. BL and Pfz are the abbreviations used for the occasional passage taken from the British Library and the Pforzheimer collection in New York.

We have been able to include Clare’s Journal in this volume, very occasionally improving on Margaret Grainger’s readings, although we do not have the space to match her wonderful annotations on natural history. Unlike Dr Grainger, however, we have not regularized Clare’s dating. The Journal is an essential part of Clare’s general autobiographical record, providing evidence of his correspondence, his reading, his relationship with his publishers, and his family affairs. It reveals how much almanacs and newspapers formed part of his daily reading and how he became increasingly interested in archaeology. Natural history was of course a critical part of his life — the Journal shows how deeply he was interested in the history of old trees, for instance — but so also was a serious study of religious writings. The Journal is a true record of Clare’s intellectual diversity.

The autobiographical writings so far mentioned only take us up to 1828, thirty-six years before Clare’s death. We have therefore thought it desirable to add one or two pieces dealing with Clare’s later years. We print here his ‘Journey out of Essex’, describing his journey on foot from Dr Allen’s asylum in Epping Forest to Northborough. We also include a few of Clare’s asylum letters from Northampton because they show how closely he retained in memory his friends and neighbours in Helpston. Many more are to be found, of course, in Storey’s edition of Clare’s letters. Our readings of all documents have been made independently, though we have benefited from the opportunity of making comparisons with other editors’ readings.

All Clare’s work needs, ideally, to be read aloud, for the sound of the local Helpston voice vibrates throughout it. Clare grew to be critical of punctuation and increasingly dispensed with it. This means that the reader has to allow the meanings of the prose to dictate the rhythm and movement: one has to feel one’s way carefully as if looking for a nest in a thicket. We have tried to help by leaving spaces between sentences, for sentences and natural breaks there are, if seldom pointed. But in the ‘Sketches’ Clare sprinkled commas and semi-colons all over the place. We have chosen to remove much of that punctuation to bring the work into closer alignment with his maturer method of composition. As he himself wrote: ‘do I write intelligible I am gennerally understood tho I do not use that awkard squad of pointings called commas colons semicolons etc …’36

CLARE’S COUNTRYSIDE

We have not changed spellings — except that ampersands have been translated to ‘and’ — nor standardized grammar because Clare’s practice in such matters was highly personal, and he came to object ever more strongly to such interference with his work. Some previous editors have substituted standardized words such as ‘shrill’ and ‘porch’ for the dialect forms ‘shill’ and ‘poach’. We do not intend to cramp Clare’s writings into a conformity entirely foreign to them. All editors of Clare tread a fine line in such matters. We do not believe that we are justified in making verbs and subjects agree in number, or in removing double negatives when it is certain that such practices were part of Clare’s speech and grammatical habits. The reader will soon find it easy to come to terms with Clare’s language: again, the best test for the reader to adopt is to read a puzzling word aloud. We have included a glossary for all difficult words just as Clare’s first publisher, Taylor, did.

A space between square brackets in the text means that Clare has left a space in which he intended later to fill in a word or words but has failed to do so. Words or letters between square brackets are supplied by the editors and are not in the text. Clare may have omitted them inadvertently. In other cases, the paper has deteriorated since Clare wrote. In this text, intended for the general reader, we have not shown minor deletions and alterations but have mentioned those which seem to us to be of importance to the meaning or to illustrate Clare’s intentions in some significant way.

No edition of Clare will ever be final, but a generation has passed since the publication of The Autobiographical Writings of John Clare. This volume is undoubtedly more accurate and we hope that it will replace that edition as a reference source. Here is the best we can now contrive; in another twenty years, if more autobiographical material comes to light, the work may have to be done again. But that is the nature of editorial work: it is never finished.

Notes

1 See above, p.39.

2 J.W. and A. Tibble, The Prose of John Clare (London, 1951; repr. 1970), p.3. Hereafter referred to as Prose.

3 Oddly enough, Clare did write one poem where the courtship takes place in a pig-sty — see The Rivals, 1.372; note in E. Robinson and D. Powell (eds), John Clare: Poems of the Middle Period (Oxford, 1996), i. p.229. His story of the magistrate Hopkinson and his wife is a brilliant satire upon condescension gone wrong (see above, pp.125-7). The satirical tone of these passages conforms with The Parish, never published in Clare’s day. See E. Robinson (ed.), John Clare: The Parish (Penguin, 1986).

4 Edmund Blunden (ed.), Sketches in the Life of John Clare written by himself (London, 1931), p.12. Hereafter referred to as ‘Blunden’.

5 See above, pp.3-4.

6 See above, p.29.

7 See also Anne Tibble, John Clare: A Life (1972) and E. Storey, A Right to Song: the Life of John Clare (1982).

8 Mark Storey (ed.), The Letters of John Clare (Oxford, 1985), pp.78-9. Hereafter referred to as Letters.

9 Ibid., p.86.

10 Ibid. p.90.

11 Ibid. p.94.

12 Ibid., pp.333-4 and notes, p.398; and see above, pp.120-4.

13 See ‘The Disabled Soldier’ in E. Robinson and D. Powell (eds), The Early Poems of John Clare (Oxford, 1989, 2 vols — hereafter Early Poems), i, pp.125-7; ‘Death of the Brave’, i, pp.248-50; ‘To the Welland’, i, pp.102-3; ‘Burthorp Oak’ in A. Tibble and R.K.R. Thornton (eds), John Clare: The Midsummer Cushion (Manchester, 1978 — hereafter M.C.), p.429; ‘On Dr. Twopenny’, Early Poems, i, p.234; ‘The Quack and the Cobler’, i, pp.164-70; ‘On the Death of a Quack’, i, pp.330-32; ‘Shakspear the Glory of the English stage’, i, pp.336-7; ‘Lord Byron’, M.C. p.389; ‘To the Memory of Keats’, Early Poems, ii, pp.476-7; ‘To the Memory of James Merrishaw a Village Schoolmaster’, Early Poems, i, pp.456-7; ‘Lines on the Death of Mrs Bullimore’, i, pp.197-9.

14 ‘To Obscurity Written in a fit of despondency’, Early Poems, i, p.386.

15 Early Poems, i, p.424-31.

16 ‘Dawning of Genius’, Early Poems, i, pp.451-2; ‘Some Account of My Kin …’ ibid., ii, pp.607-8; ‘In shades obscure …’, ibid., ii, p.382.

17 Letters, p.133.

18 Ibid., p.138; Clare to Taylor, 7 January 1821.

19 Ibid., p.147.

20 Ibid., p.161.

21 Ibid., p.161 note 4.

22 Ibid., p.173; Clare to Taylor, 3 April 1821.

23 M. Storey, ‘Edward Drury’s “Memoir” of Clare’, The John Clare Society Journal, no.11, July, 1992, pp.14-16.

24 Letters, p.172 note 2; Taylor to Clare, 7 April 1821.

25 F. Martin, The Life of John Clare (1865), p.vi.

26 Blunden, pp.11-12.

27 J. and A. Tibble, John Clare: His Life and Poetry (1956), p.10 note 1.

28 Letters, p.208. In note 9 on this page, Storey identifies this Literary Life with the ‘Autobiographical Fragments’ as printed in E. Robinson (ed.), The Autobiographical Writings of John Clare (Oxford, 1983), but see above, p.xviii.

29 Ibid., p.311.

30 Ibid., p.311 note 2.

31 Prose, p.2.

32 Letters, p.311.

33 See above, pp.173, 178 and 197.

34 Letters, p.380.

35 He seems to have obliterated remarks critical of Taylor in his Journal for 30 March 1825, 15 April 1825 and 17 April 1825, but it should be pointed out that the Journal does not actually begin until September 1824.

36 Letters, p.491.