2: The Late Middle Ages and the Age of the Rhetoricians, 1400–1560

Herman Pleij

I. Literary Life in the City

Urban Spectacle

In the late Middle Ages, society in the Low Countries was becoming more and more urban, and this brought with it changes to the literature that flourished there. From the fourteenth century onwards, towns and cities increasingly served as the focal points not only for commerce, finance, and artisan manufacture but also for ecclesiastical authority, worship, the arts, learning, and even courtly life. By the end of the Middle Ages all these activities would be conducted almost exclusively in this urban space. Rather than simply being another arena for things already familiar, the new environment saw the commingling of forms of human socialization and behavior that in previous centuries had remained separate but were now becoming integrated. This melting pot produced all kinds of innovations, adding new facets to a literature that in these urban circles, too, continued to be an instrument of unparalleled ideological importance.

The towns and cities of Flanders and Brabant were the first to emerge as centers of literary life, keeping pace with the relatively rapid spread of literacy within the new milieu. This development sprang from the specific communication needs of industry and commerce and coincided with the speedy growth of a broadly based intellectual middle class of clerks and officials who worked for the municipal administrations and, of course, the judiciary.

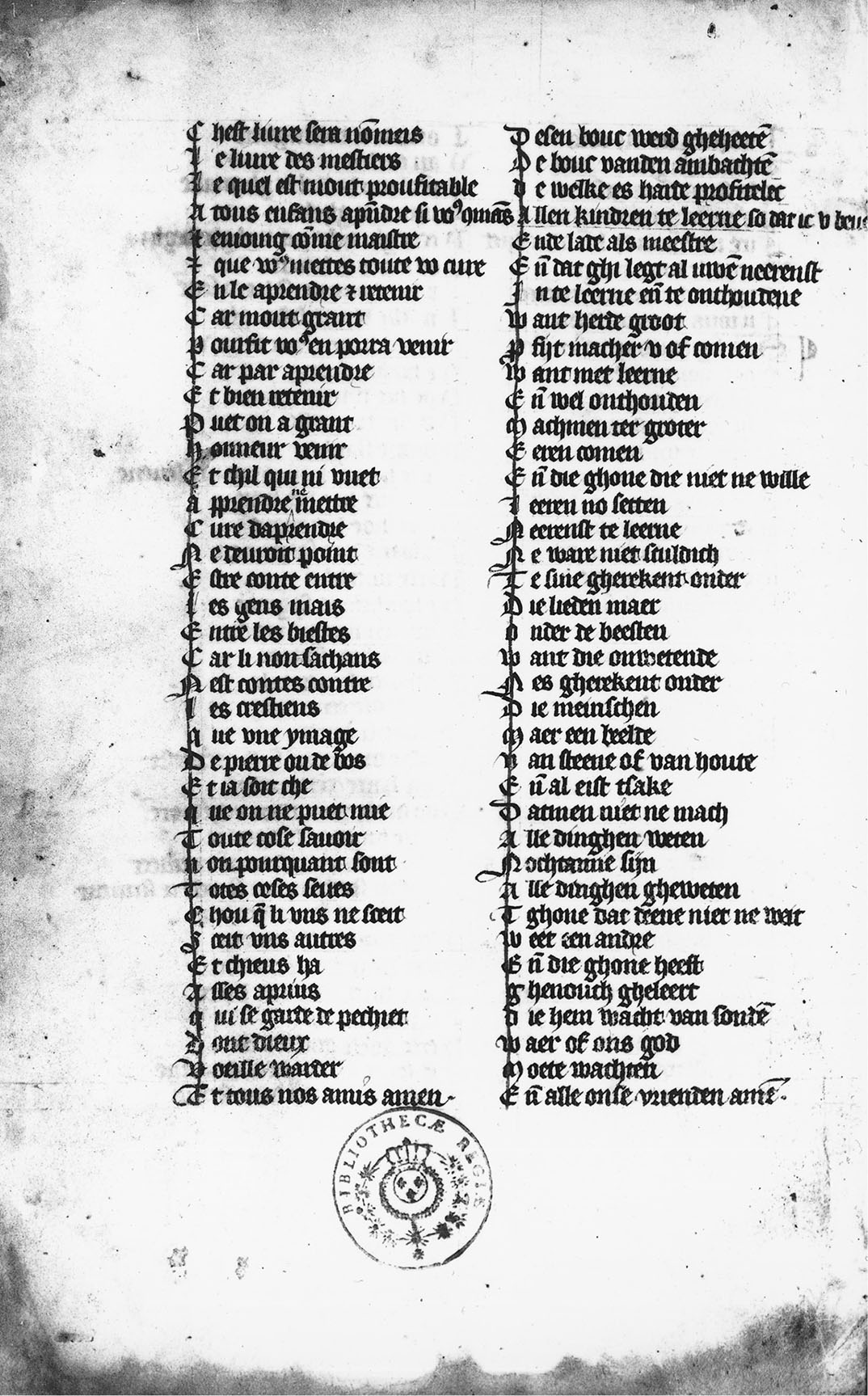

Final page of the Book of Professions (Bouc van den ambachten), written c. 1369. Paris, National Library of France.

A bilingual conversation manual written in Bruges around 1369, aimed at teaching Dutch and French, provides useful documentary evidence of the urban community’s awareness of a well-established literacy — a society that was now able to perceive and chronicle itself within a historical context. The Book of Professions (Bouc van den ambachten / Livre des mestiers) was intended for a new kind of school that was attempting to break free from ecclesiastical control. As an initiative of merchants and guildsmen, these new schools were inspired by the needs and aspirations of urban society rather than by those of the church. The Book of Professions therefore strove to approximate the language of everyday life in as direct and practical a manner as possible, using thematically organized dialogues and quasi-spontaneous arguments. It goes without saying that the didactic framework only presents situations and topics that would have been immediately recognized, such as the following:

Gilbert the clerk writes excellent legal and contractual documents, charters and deeds, expenses and incomes, wills, and transcripts. He is also highly skilled in accounting, such as calculating annuities, income from an estate or a loan, and even ground rent. Employed in a suitable post, one could profit greatly from him.7

Part and parcel of the urban scene, it appears, is the bookseller, who in those days also dealt in writing supplies: “Joris the bookseller has more books than anyone else in the city. He also sells goose and swan quills, and parchment of both superior and standard quality.” Elsewhere the manual recommends regular school attendance. It describes the activities of the town clerk (renowned for his skill in algebra), a specialist parchment seller, and other artisans and professionals. Together they provide the city with a network of practical learning and other aptitudes in the service of trade and prosperity. However, the crux was still the written word, which had nestled at the heart of the city and was never to abandon it again. The manual draws to a close in similar spirit:

Dearest children, this book need never come to an end, because no matter how much I write there will always be more to be written, providing one makes one’s best effort. For ink is not expensive, and paper is as fine as it is patient and can easily accommodate everything that one would want to commit to it!

The new bureaucracy was the exponent of an intricate system of guilds and fraternities, which supported a large-scale literary enterprise, and not simply by presenting organizational opportunities but also by functioning, together with the city authorities, as patrons of the literary arts. Literature, after all, made it possible to legitimize, defend, embellish, and even expand their newly gained power, vested interests, and ambitions, all under the guise of entertainment. From the very outset this urban literature was richly varied, its chief feature being that almost every literary manifestation was staged in the public sphere.

This is evident from the plentiful street spectacles that brightened up daily life nearly every week, on occasions such as the numerous feast days for saints, and other annual holidays. There were also pageants, fairs, seasonal markets, neighborhood festivities, the tournaments and contests of the civil militias and chambers of rhetoric, and the celebrations of the patron saints of the city’s many guilds and associations, both professional and more recreational in nature. These are only the stimuli from within the urban society; there were also external motives that prompted spectacular celebrations, such as the investiture of a new sovereign or a birth, baptism, marriage, or death among the ruling dynasty, or, of course, its military successes. This exuberance, as necessary as it was strictly orchestrated, reduced the working days per annum to half the number we are accustomed to nowadays. It should be noted, however, that the number of working hours per day was, in principle, determined by daylight hours and could therefore add up to an average of ten to twelve hours per day over the course of a year.

The festivities around the Burgundian court (which later gave birth to the Burgundian-Habsburg dynasty) were seized on by towns and cities large and small for solemn celebrations and commemorations, frequently accompanied by great rejoicing among all the strata of a city’s population. First and foremost, however, the civic tribute fulfilled a political function, for while it undoubtedly reflected the city’s fundamental subordination to the sovereign ruler, it did not conceal the fact that for the city the tribute was primarily about promoting its own interests and sometimes even making demands. The priority was to remind the sovereign of his obligations to the urban community, which therefore routinely mobilized the whole institutionalized festivity-machine in its midst.

The increasing autonomy of urban communities from the sovereign ruler, and the incessant conflicts that had paved the way for such a development, determined the late medieval history of the Low Countries under the House of Burgundy. In 1433 the Duke of Burgundy, Philip the Good, settled in Brussels, underscoring that the heart of his domain now lay in the North. Thanks to an ingenious policy of strategic marriages, territorial acquisitions, and imposed protection he quickly expanded his rule across the whole of the Low Countries.

This new European powerhouse, which was extended to include the Austrian and Spanish territories of the Habsburgs in the late fifteenth century, relied greatly on the prosperity of the towns and cities of Flanders and Brabant. Consequently, the lead players in those urban communities — patricians, the upper echelons of the administration, wealthy merchants, guildmasters, and, last but not least, the local ecclesiastical dignitaries — enjoyed considerable power throughout the empire. The sovereign overlord was in fact increasingly dependent on the capital and trade networks made available by the urban elite in exchange for military protection, greater autonomy, and certain forms of obeisance which were intended to gain the burgher a place in the circles of the nobility and knights.

Nevertheless, striking the right balance of power between the ruler and the urban communities proved difficult. Towns and cities repeatedly overplayed their hand and refused to pay taxes, especially when it came to extra taxes to bankroll a ruler’s wars for which they felt little interest. Moreover, relations with the potentate were a persistent cause of internal tensions which often sparked bloody rebellions within the city walls.

It seems as if Ghent, as the most powerful city, sometimes wanted to present itself as a wholly autonomous city-state, following the example of the Italian cities, but neither the ruler nor other cities allowed this to happen. And if Ghent ever believed it could bask in the good grace of Charles V (1500–1558), the emperor who had been born there, then he disproved that with the bloody revenge he wreaked on the city in 1540, after Ghent’s citizens had once again refused to contribute to a campaign of national import. Even more serious was the reputation Ghent had acquired as a hotbed of heretical propaganda for the Reformation, spurred on by the rhetoricians who represented the official literary life of the city. By carrying out a string of executions, demolishing civic bastions, and implanting a military garrison within the city, Charles was perhaps attempting to call a definitive halt to this urban arrogance. This may have served as a warning to other cities as well, but it remained obvious that material and cultural might were by now firmly anchored in the cities.

A fine illustration of the need to exact and secure the desired relationships within the hierarchical order is provided by the spectacle staged by Ghent on 3 March 1500 to mark the christening of the young crown prince who would later become the emperor Charles V. The decorations along the streets made an unforgettable impression on those who saw them. The widely traveled humanist and historian Adrianus Barlandus (1486–1538) wrote of truly wondrous spectacles, to be seen in all quarters of the city. A later chronicler ratifies this, commenting that the eye-witness reports were “well-nigh impossible and almost incredible.” However, their reliability and accuracy seemed unequivocal, so he could do nothing but express his utter amazement at the remarkable inventiveness of the city’s inhabitants.

The route to be followed was covered over, thus forming an extended gallery illuminated by no fewer than 1,800 torches and accentuated by triumphal arches, each of which bore a different message. Even toward the end of the Middle Ages, fire still constituted a distinct attraction — the natural rhythm of day and night could hardly be influenced otherwise. The baptismal ceremonies were evidently held early in the morning or late in the evening. The baby prince was carried in procession under a series of gantries that impressed on him values such as wisdom, justice, and peace, probably in the form of tableaux vivants or statues adorned with texts. The houses were also decorated with torches, paintings, and banners, and a fanfare of trumpets resounded incessantly.

Whether a festive text by the priest Lieven Boghaert (dates unknown) was also recited here is unknown. As the so-called factor, the artistic leader of the Saint Barbara chamber of rhetoric, he certainly sang the praises of the young prince at length, saluting him as a worldly redeemer in no fewer than twenty-one strophes of nine lines. The age of oppression is now at an end, and browbeaten Ghent can look forward to a new period of prosperity:

Awake now, sleeping souls and depressed spirits.

Rise up in full glory, you troubled hearts!

The text, like other components of the festivities, is certainly lacking in originality, as evidenced by its succession of blatant commonplaces, but these are precisely the elements on which such formulaic literary spectacles rely. The clashes between Ghent’s city authorities and the court were already notorious; the city attempted time and again to assert its independence from the sovereign, hoping to attain a status on a par with, or even above, him. The city authorities were, however, repeatedly and heavy-handedly brought to heel by a government that watched every form of urban particularism with eagle-eyed suspicion.

Archers; detail from The Hoboken Fair (De kermis van Hoboken), burin engraving by Frans Hogenberg after Pieter Bruegel, 1559. Brussels, Royal Library Albert I.

The sense of malaise that the rhetorician Lieven Boghaert described was by no means an exaggeration. This applies in equal measure to his imploring supplications that the newborn heir to the throne should enjoy the gifts of wisdom, peaceableness, and justice. In the opinion of the burghers of Ghent, these were qualities that had been distinctly lacking in his forefathers. The hope was that Charles would grow up in their midst as a Fleming, fully alive to the needs of the cities and those of Ghent in particular, the city where he had seen the light, hopefully in more than one sense. His birth and baptism therefore merited the grandiose spectacle of which he could be reminded throughout his life, with a list of demands in the guise of a mark of honor.

Literature in the city was the servant of individual and collective trials and tribulations. When it came to the spectacle and imagery produced for festive parades or religious processions, people were less concerned about the desired relations with their ruler. Yet here, too, the promotion of the city — and the public interest — remained the central concern. The local authorities seized on these occasions with enthusiasm, exuberantly mobilizing the city’s literary and theatrical talent.

Long before the founding of the exclusively literary societies known as the chambers of rhetoric, such talent seems to have been readily available among members of the devotional associations known as confraternities, and of the local civil guard or militia. These groups organized the processions and the performances that took place during or after them, which might have consisted of silent spectacles on floats or along the route, or even of complete plays being performed during the course of the procession or at the procession’s end. The fraternities, sometimes referred to as “companies,” refused to relinquish this role even after the chambers of rhetoric split away to form separate organizations. Until well into the sixteenth century they continued to play a prominent role in the organization and realization of urban spectacle, sometimes in association with the members of artisan guilds.

This is demonstrated, for example, by the annual procession of Our Blessed Lady in Brussels, a tradition that lasted for more than two centuries. The chief organizer was the “Great Guild,” which united the city’s crossbowmen. The enduring importance of this guild for the city is evident from the self-awareness so eloquently expressed in their livery, which was issued by the city in 1412: a red cloak, green bows, and a red hat. From 1348 the guild organized the procession, which commemorated the secret transport of a statue of the Virgin Mary from Antwerp to a church in Brussels. From the very start this involved the performance of a Marian mystery play. In 1441 the event was elevated to a higher plane by expanding the spectacle and introducing a cycle of seven plays, the Seven Joys of Mary (Bliscappen van Maria). Only the first and seventh Joys have survived in manuscript. The seven-play cycle was performed each year without interruption until at least 1559, and to judge by various accounts it must have been a magnificent event. Each and every year visitors flocked from far and wide, and high-placed guests — including the sovereign — were also invited.

This religious processional theater, which included tableaux vivants within the actual parade, was seized on by the city of Brussels for exuberant self-promotion. The monies made available were primarily channeled into the expansion and improvement of the play proper, and the new scheme of a seven-part cycle was a stroke of genius. Now the city could advertise a serialized spectacle, designed to establish something like customer loyalty. The organization was also professionalized: it gained a permanent depot for decorations and floats, the times and places of the complete production were set out in a grand scheme, a new stage was provided for the performance of the plays, and it was timetabled so that mealtimes for the guests did not clash with the highlights of the procession or the plays. In addition, the magistracy decreed that other organizations in the city, notably the chambers of rhetoric, were obliged to contribute, and in the years after 1441 these bodies did indeed become involved. Lastly, festival officials on horseback were introduced, charged with maintaining order around the procession and with keeping it moving.

The aims of the procession can also be deduced from the two surviving plays. The material was highly familiar, but it was spectacularly dramatized and, in particular, quite clearly brought up to date for a broad public, in the manner of the exciting tales from the Bible. The Fall of Man, the defeat of Satan, the legend of the Holy Rood, prophecy plays, and the debate of vice and virtue were not only cause for excitement; they were also scripted to be emotionally stirring and even spilled over into slapstick. Examples of the latter include the extremely banal scenes with Adam and Eve, certainly when Eve reduces her husband to a henpecked faint-heart on whom she pours abuse. Eve is approached by the serpent and then informs Adam that she wants to discuss something with him. He is a paragon of obliging reasonableness and affability:

What shall it be,

My Lady Eve, that you most earnestly desire

From me? An explanation I require,

Without delay, then, I shall do

My utmost, out of love for you.

For I would not your anger rouse,

Be it within reason.

However, Adam is profoundly shocked by Eve’s proposal that he taste of the apple. Realizing that this is contrary to God’s will, he tries to reason with her to change her mind. God has emphatically forbidden it! There are trees enough to satisfy her appetite, so why this one in particular? But Eve interrupts him with a crude and somewhat premature curse: “Jesus Christ! Quit whining, Adam. Take it and eat it!” Adam is helpless in the face of such female aggression, and he takes a bite. From that moment on he is transformed into a complaining, henpecked wimp who is bossed around by his wife, even after their expulsion from paradise. Condemned to a life of blood, sweat, and tears in worldly woe, he sits down in despair. And Eve takes the initiative once again. She shoves the spade into his hands for him to go and till the earth, to earn his bread by the sweat of his brow, while lamenting that now, poor wretches, they must work to stay alive.

Updating texts in this catchy manner encouraged the audience to make a connection between the tales and their everyday lives. The transformation of Adam into a foolish, henpecked husband, overcome by infatuation, inertia, and fear, would have hit onlookers hard, since it was an exact inversion of how conjugal relations were meant to be. The adaptation of the story of the fall of man served to propagate a new conjugal ethic. The positive ideal that the play strove to project was a stricter division of roles within the household, in which the husband ought to be absolute lord and master and the wife should remain as far removed as possible from public life. Otherwise the city’s economy would surely degenerate into chaos.

Another scene acquires special significance thanks to the addition of a dialogue between two neighbors. They talk about how the impotent Joachim (who was to become Mary’s father) was humiliated by the temple priests, who had driven him out because of his infertility. It is the public nature of this act to which the neighbors take offense, and they want to voice their indignation loudly. However, one of them admonishes the other to be silent, with the warning that you must always be wary of such priests, and the other agrees. The scene clearly recommends being pragmatic, even opportunistic, although it is also sharply critical of the clergy: never speak your mind, for such priests are not to be trusted. And at every performance this message would have been topical and relevant for urban society, whether it was applied to countering the ever-controversial hypocrisy of the clergy, the aggressive moral claims of the mendicant friars in their noisy sermons, or the church’s systematic refusal to pay any form of tax.

The scene also highlights a sense of privacy. The message is that certain things should be kept out of sight and hearing of all and sundry, and should remain within the circle of those directly concerned. The growing inclination to withdraw into one’s private space seems to have been an important goal in the midst of cramped urban living conditions. Here too literature stepped forward in order to offer escape routes and to articulate alternative possibilities, preferably using old and trusted themes that could lend true authority to new aspirations.

Besides guilds, militias, confraternities, and chambers of rhetoric, there were — and continued to be — loosely organized groups of semi-professional entertainers in various towns and cities. It is by no means always clear whether these companies or guilds of actors were groups of burghers who normally pursued another profession but were called on for special occasions, or professional actors who traveled far and wide. We often encounter such companies in municipal records, demonstrating that the authorities were keen to stimulate the urban dynamic with all kinds of manifestations and performances, for which a whole variety of artists stood ready.

The accounting entries sometimes mention a title. We therefore know that a company of actors from Diest performed the Play of Lanseloet (spel van Lanseloet) at Aix-la-Chapelle in 1412. This must be a reference to Lancelot of Denmark (Lanseloet van Denemerken), one of the four so-called abele spelen (“noble” or “beautiful” plays), which are recognized as the oldest known form of serious secular drama in medieval Europe. The play was later distributed in print, and the numerous reprints testify to its success. However, the ledger entries usually mention titles of works that have not survived as drama, though their kinship with the still-prevalent tales of chivalry is obvious. For example, there are entries for a performance of The King of the Moors (den coninc van den Moriaens) at Kortrijk (Courtrai) in 1418, and of a Play about Aernout (spel van Aernoute) at Tielt in 1431. A play called Roland and Oliver’s Campaign (de batailge van Roeland ende Oliviere) — evidently a dramatized version of The Song of Roland (Roelantslied) — was performed by a company from Geraardsbergen in 1423 and 1424. The 1444 records of the town of Deinze refer to this play as The Play of the Battle of Roncevaux (’t spel van den wijghe van Ronchevale), and also mention performances of dramatized versions of Floris and Blanchefleur, The Four Sons of Aymon, and the Romance of the Rose, which are all texts we know only in epic form.

Occasionally one encounters a whole list with the titles of plays that were performed, as in the records of a confraternity in Ghent dated 1532. This inventory mentions twenty-one plays, eight of which must be considered as religious; the others seem to be secular. Only The Duke of Brunswick (Hertoghe van Bruisewijc) is identifiable as a version of one of the abele spelen, namely Gloriant. The other plays are known only in the form of chivalric romances or novellas, such as The Knight of Couchi (Ridder van Coetchij), Lucretia and Eurialus (Lucresia en Eurialus), The Lord of Trazegnies (van den Heere van Trasengijs), The King of Aragon (Conijnc van Aragoen), The King of England and the Evil Moor of Hainaut (van den Coninc van Ingghelant ende de quade moere huut Henegauwe), and The White Knight (van den Witten Ridder).

Besides the theatrical endeavors of the chambers of rhetoric there must have been plenty of other dramatic activity during the fifteenth century. This was primarily focused on the performance of works more secular in nature, for which popular tales from the world of chivalry could easily be translated into drama. Or could the list above actually refer to the repertoire of puppeteers? The municipal accounts clearly refer to companies of actors, though their status is far from clear. Little of their dramatic material has survived because of the loose structure of these companies and the transient nature of their performances. Plays were rarely written out in full, at best being stored as a number of individual roles known as “parts.” With their more firmly structured and established chambers, the rhetoricians would be the first to establish an institutional repository for theatrical repertoire, which was now recorded in a complete form with a view to later use.

We encounter such a semi-professional actor with his own small theater company in the town of Geraardsbergen in the person of Pieter den Brant. A carpenter by trade, he was also responsible for regular performances for the town with a company of like-minded individuals. In the period 1427–30 he was remunerated for this by the city magistracy. He must have been multitalented, because as justification for the generous payments the records note that “he is skilful in the composition of plays and rhyming texts, as well as in the improvisation of quick rhymes, one after the other.” His aptitude seems to be to produce a popular variant of the thousands of lines of verse that the great medieval poets were able to produce at great speed. The fragment that survives, a one-hundred-line rhyme about the qualities of the four human character types based on the four humors, demonstrates Pieter den Brant’s skill. The theory of humors was a popular notion at the time, and the poem couches it in a very simple rhyme full of padding. This not only suggests that the poem was jotted down à la minute but also leaves the distinct impression that it was intended only for subsequent recitations, and not for reading in private.

Burgher Virtues

In town and city, literature seems to have been the ideal instrument for creating an intellectual space that enabled the burghers to defend their interests and claim their rightful place in the order of things. Within this literary space, the burghers established the freedom of mind to openly confront the traditional powers with an identity of their own. This typical middle-class literature does not hesitate to present its proposed social model as superior to all others. The late-medieval city in the Burgundian Low Countries defined itself, at least on paper, in terms of an unprecedented urge to expand, and in fact aimed to swallow up the aristocratic domain and the countryside, or at least make these spaces subordinate to its own commercial might.

Literature could, moreover, serve as a formidable weapon to establish new hierarchical structures or to protect existing ones. Most feared was the so-called scoffing song, because it could crop up anywhere and authorship proved very difficult to trace. There are numerous extant edicts from the late Middle Ages and the early modern era that announce severe punishments for the singing and distribution of such songs, up to and including public execution. For example, on 25 October 1444, Louvain’s authorities forbade anyone to publicly taunt a certain Roelof Roelofs and others “in poetry or song.” The figures in question must have been local dignitaries, since such attacks would have been understood as mockery of the city in general. The threatened punishment consisted of a pilgrimage of atonement to the Alsace. Not even minors escaped; if they were found guilty, their parents were held accountable. There was good reason for these measures, because in their periodic charivari — rituals with raucous “pots and pans music” which accompanied an alternative dispensation of folk justice — youths would denounce any established burghers who by their adultery appeared to hamper the youths’ own chances of becoming settled, for example by finding suitable brides. That was why, in 1425, the city authorities in Brussels felt compelled to prohibit them from shaming adulterers with their songs.

Almost everyone participated in this urban literary culture, and it found expression almost entirely in the public domain. The boundaries between its conceivers, designers, producers, actors, musicians, followers, and spectators were fluid. Everyone was involved in some way or other. However, all this street theater in an urban setting was not simply intended to serve the validation, consolidation, and projection of a new urban self-perception in relation to the sovereign ruler; people from different urban communities competed with one another as well. The literary forms were no less important as a means of foregrounding and promoting particular social strata within the city, all under the well-intentioned pretext of a fundamental concern with common interests. The city was primarily attempting to shape its own literature based on urban aspirations and frustrations that the new form of cohabitation and community inspired among the burghers. Collective fears and ideas were as much defined by texts as they were manipulated by them. Along with their obvious purpose as recreation, the texts also continued to contribute directly to the regulation of a contented everyday life on earth that, in principle, had to be attainable for all.

It is illuminating how, for example, people tackled the age-old fear of the devil, the incorrigible malefactor who is incessantly setting ingenious traps into which bedazzled humankind has been stumbling since the Fall of Man. This was achieved in the form of a comic play which at first seems to completely deny that such a fear exists. On stage, the devil is consistently presented as a farcical character who breaks wind out of nervousness and can be hoodwinked by the simplest of souls using the simplest of ruses.

This is what happens in The Apple-Tree (Esbatement van den Appelboom), a striking little play from the start of the sixteenth century. God comes to the aid of a truly simple peasant couple in answer to their complaint about the repeated ransacking of an apple tree. God decrees that anyone who climbs into the tree will be trapped there. When Death appears (in the shape of a woman), the peasant couple ask her to pick a last apple for them to quench their thirst. Death is then trapped, and when the devil appears, in a rage, demanding to know why so few people are dying and he is having to make do without the daily delivery of souls to hell:

Brrraaagh! What’s become of darling Death?

I’ve such a longing to see her. Is she lost?

Have the succubi been at her and sucked out her soul,

or has she hidden her might in a mouse’s hole,

seeing the gravediggers’ spades have gone silent?

Lucifer in his blind fury writes Finish

Even for cowerers and skulkers in corners.

I must delve in every direction for Death.

By Lucifer’s sweat, what secret place is she lurking in?

I gaze on the ground and harry the horizon —

they deliver me as much as Madoc’s dream!

— Wait a bit, what’s that up there in the apple-tree?

It’s Death, there’s no doubt! It’s my dear friend Death.

Ahoy, Death darling, what in hell’s name are you doing?

Are you trying your hand at horticulture?8

Prompted by the peasant couple, the devil joins Death in the tree, and then both are trapped.

An amusing play like this channels and allays collective fears of death and the devil. One can negotiate with Death, and the devil is easily duped. Though the deep-seated terror is certainly not banished, it is rendered manageable by a form of communal ritual meant to make life on earth tolerable. Literature teaches us that there is an answer to everything, and confronting the masses with humor and satire plays an important part in this.

The same applies to the recitation of boerden, a genre closely related to the fabliaux of northern France. With their topical humor, these short, comical tales in verse had a much greater impact on the public than we might at first suspect. For example, in The Monk’s Tale (Vanden monick) we encounter a preacher renowned for his tirades against the devil. However, he has made a young woman pregnant and, fearful of retribution, he is intent on escaping the consequences. The devil in disguise obligingly dashes to his aid. He says he can temporarily remove the monk’s dastardly member, enabling him to prove that he does not have the equipment necessary to have committed such a sinful act. No sooner said than done! The monk brags from the pulpit that he will prove his innocence and then lifts his habit. But to everyone’s consternation the devil has that very instant taken his revenge by re-endowing the monk with a member as gorged and erect as it is substantial.

Such tales were recited and even acted out by professional actors, who interpolated plenty of apposite mime, obscene gestures, vocal distortions and, above all, as much audience involvement as possible. They thus enacted a collective ritual, replete with peals of laughter and snickering, in which a shared fear of sex, the devil, and mendicant friars — those hypocrites and quasi-scholars — was rendered manageable by ridiculing and thus temporarily allaying it. Humor was perhaps the most important lubricant in the cogs of human society.

The cozy domesticity and banality of these texts was instrumental to such a handling of collective anxieties. Devil and mendicant friar were also belittled by cutting them down to fit the audience’s immediate surroundings. This made them even more mundane and therefore more intelligible for the masses. The Anti-Christ Play (Antichristspel) of around 1430, from Limburg, seems to contain the outline of a black comedy, but only fragments survive. Two low-ranking devils are seriously concerned about how to keep souls trapped on earth fresh during their journey to hell. Lucifer, their devil-in-chief, will be furious if they do not succeed. They come up with the idea of salting them, and Lucifer advises them to go and find salt in Stockheim on the River Meuse and in Biervliet in Zeeland. As with herring, this will prevent the souls from rotting. Lucifer’s advice refers to a tried and tested technique, since Jan Beukelszoon had introduced the practice of gutting and pickling herring in Biervliet more than a century earlier, while Stockheim was renowned for its salt production. Besides the comic effect of the operation itself, it provides a succinct example of the exploitation of everyday reality.

The urban literature of the late Middle Ages played an active part in molding, defending, and propagating what came to be known as typical middle-class virtues, with pragmatism and utilitarianism as its primary pillars. Literature employed an extensive arsenal of rhetorical techniques in order to achieve this goal, developing a highly particular art of persuasion and an array of new text types. These were intended to provide some consolation for the mishaps that could disrupt the life of the city-dweller. They also supplied the intellectual wherewithal to withstand the daily onslaught of dangers that could strike and throw them off balance at any time: fickle fate, infatuation, and sudden death.

To this end, individual texts, complexes of narrative material, and models from earlier times were annexed and adapted, prompting later characterizations such as “vulgarizing imitation.” However, the suggestion of plagiarism is anachronistic, since the medieval notion of art attached very little value to originality. In fact, originality was suspect, since anyone could make something up. The essence of true art lay in demonstrating mastery in the reworking of familiar materials and examples from the classical, biblical, and earlier medieval canons, in line with the prevailing laws of poetics and rhetoric.

The chivalric verse romance, which had its origins in courtly culture, offered the burghers attractive points of reference, providing the romance was tailored to reflect urban aspirations and morals. The thirteenth-century Henry and Margarita of Limburg (Heinric en Margriete van Limborch), for example, was altered to provide various points of identification for the new city-dwelling audience, first and foremost by concentrating on an individual hero or heroine in the title; as we shall see, a bourgeois readership was primarily interested in the inspirational model of an individual hero. The scene that includes Henry’s elevation to knighthood was also adapted. He must swear to uphold the traditional knightly virtues, such as loyalty to his lord and master and the protection of widows and orphans, but the new prose version adds that he should be creditworthy under all circumstances: “Pay generously wherever you travel, by land or sea, then people will speak honorably of you.” The obligatory concept of honor is retained, but now it is associated with a virtue that belongs specifically to the mindset of an urban society.

Within the urban milieu there was also a growing interest in the function of literature as an uplifting or even therapeutic instrument, resulting in a raft of corresponding adaptations of existing texts. The simplest form of adaptation was the addition of a prologue or foreword, which preached at great length about the recommended manner of reading the ensuing text and mentioned the salutary effect that would follow. For example, the prose version of Hugh of Bordeaux (Huyghe van Bourdeus), printed at the start of the sixteenth century, is accompanied by an instruction that was becoming common practice for such texts: the work, it is said, is primarily intended to provide entertainment and pleasure, “and to lighten people’s spirits if they are troubled by any melancholy, whether brought on by the evil influence of the devil or by slowness of the blood. For melancholy also generates heaviness and usually thickens the blood, which often makes a person ill.” This well-nigh-clinical explanation emphatically makes the point that the entertainment factor in literature is a means of combating melancholy. The fact that such modifications to the texts were considered necessary reveals how bourgeois the culture of the Low Countries had become. The original version of Henry and Margarita of Limburg opens with Duke Otto stating that he wishes to go out hunting. That was perfectly normal for a nobleman, so an audience in court circles required no explanation. In town and city, however, this was not the case. Nature was no longer regarded as a challenging wilderness to be conquered by knights to their hearts’ content. For the urban middle classes, nature had acquired new functions and significance. Besides being a perilous playground of the devil, who is fond of trying to make vulnerable individuals stumble and fall there, it has also become a place of consolation which can bring pleasure and even healing to desperate souls. Hence an audience of burghers expected a motive when someone — knight or otherwise — headed out into nature. The 1516 prose version accordingly adds that Duke Otto was melancholy and was therefore seeking solace in going hunting.

Such simple interventions are extremely telling. They demonstrate that old literary material has been made useful again. At the same time they reveal the fountainhead of public opinion in urban society: it was primarily courtly culture which furnished the models for behavior worthy of emulation. This was so firmly rooted that many a knight could be transformed into an inspiring entrepreneur by means of a simple rhetorical device. The adventurous merchant setting out into the world liked to perceive himself as a fearless knight. This process of literary annexation and adaptation had already begun in the fourteenth century, when the urban community, which now enjoyed its own solid, centralized administration responsible for maintaining peace and public order within the city walls, took advantage of new opportunities for social differentiation. The emerging urban elite saw literature as an apt vehicle to serve these purposes.

The abele spelen, four plays that represent the world’s oldest known forms of serious, secular drama, provide an early example of this. Together with six farces, the plays have survived in the Van Hulthem manuscript, which, as discussed in the previous chapter, was probably compiled in Brussels around 1400 and contains a range of texts for use in an urban context. The various plays are much more closely related than has generally been assumed, their common focus being the emerging urban elite and its aspirations. The farces ridicule the inverse of the ideals of the urban bourgeoisie, projecting them onto caricatures of peasants or rural immigrants living in town and city. These folk gesticulate wildly, have disgusting eating habits, lack all inhibitions, and inhabit a world that is devoid of any sense of privacy. We find the same device of the topsy-turvy world in the “realistic” portrayals of peasants in prints and paintings realized a century later.

In later centuries, and even to this day, such cardboard caricatures of undesirable behavior have sometimes been taken for conscientious accounts of medieval life as it actually was. However, if the medieval period ever presented a veiled image of itself, then it is in these documents. A text such as the so-called Song of the Churls (Kerelslied) is a good example. It comes from the most famous collection of secular songs in the vernacular, part of the Gruuthuse manuscript, which was compiled in Bruges by a city confraternity that, under the leadership of Jan van Hulst, undertook a whole range of cultural activities from the late fourteenth century. The “peasant” in this text is a construct, fashioned after the seven cardinal sins and other forms of undesirable behavior that were the very antithesis of how a cultured burgher in Bruges was expected to behave. He is bad-tempered, wears disheveled clothes, has long, unkempt hair, and gorges on food the whole day long:

Bread and cheese, curds and whey,

The bumpkin eats the livelong day,

That’s why he’s such a simpleton,

He eats more than is good for him.

And his wife looks just as scruffy. When he goes to the fair he fancies himself a count and wants to knock everyone out of the way with his gnarled staff. A swig of wine has him tipsy in no time, and then he gets completely carried away, imagining he can lord it over the world. Having returned to his wife’s side, thoroughly drunk, he tries to placate her, but she curses him to high heaven. He manages to get her back on his side, and peace is restored. They become entranced by the sound of the bagpipes and the two of them stamp around wildly. It is high time, the song concludes, that these country bumpkins were taught a lesson by dragging them through town and hanging them.

We also encounter this upside-down world in the farces that accompany the abele spelen. Blow-in-the-Box (Die buskenblaser) opens with a long monologue in which an old peasant claims an improbable portfolio of skills. His lengthy list is a catalogue of distinct trades as they had evolved in the urban milieu, where people had also learned to distinguish between them with a view to the organization of society in general. The peasant declares himself to be a miller of wheat, but he can also sew bags and gloves, knows how to mow grass and flail corn, and claims to possess the commercial acumen of a market trader. And he can pass for a carpenter, though to be honest he has never earned a penny from it. Nor is he averse to making investments using borrowed money, though he concedes he will be tardy with repayment. He is, moreover, equipped to chop down trees and clear thickets, to brew beer, bake bread, build dikes and create polders, and thresh and winnow grain. And there’s more! He is available if a lady or gentleman would like to hire him as a servant, though he readily admits that he likes to sleep late, is rather sluggish in his work, and loves to linger over his food. In order to swiftly dispel the poor impression this could make he concludes with the statement, still meant as a bragging advertisement, that he can also dig and tease flax.

From the perspective of the urban community, the peasant’s hilarious and inane catalogue of skills represents a series of distinct trades. The quack he is speaking to at the market is drawn into a sneering elaboration on this ridiculous list of professional specialties. In his retort, the quack claims he can “cooper” items of pottery such as stoneware dishes and milk cans. At this the peasant cries out in indignation that he must have been sent by the devil to come up with such crazy jokes. The quack is clearly scoffing at the arsenal of skills that the peasant has reeled off by adding an outrageous and nonsensical specialties to the list: wooden barrels are coopered, not pottery.

The peasant’s insistent sales pitch is motivated by a shortage of funds. He can no longer satisfy his young wife’s sexual needs — she curses him for being a useless impotent — and he wants to regain her affections with rejuvenated looks, including the proper functioning of the equipment that has failed him, of course. To that end the quack invites him, at considerable expense, to blow into a box, with the assurance that his looks will be rejuvenated and the more private parts of his anatomy will be reinvigorated, too. The peasant agrees, but when his wife sees him later, his face completely black with the soot the box contained, she immediately grasps what has happened. The farce ends with a spectacular drubbing for the poor peasant.

The peasant’s chaotic recital of so many different professions fits the criteria of didactic caricature. By means of inversion he demonstrates the urban demand for rational coherence and, especially, self-control, both of which are called for in order to constrain the stupidity that the peasant demonstrates time and again. He is so carried away by his self-sung praises that he loses all self-control and unwittingly manifests his total lack of restraint. He has never earned a penny as a carpenter, likes to swill down beer, fails to repay his debts, likes sleeping in, works slowly, and adores lingering over his food. This places the emphasis on the urban ideal of working hard, investing profitably, and exercising moderation in all things.

Above all, however, the peasant represents a world unfamiliar with the benefits of the division of labor, or even averse to the idea. In the eyes of town dwellers, the success of the urban economy can be ascribed to the spectrum of specialized professions organized under the artisan guilds and merchant companies, which reflect the core values of urban self-awareness in their prescribed attire, manners, and rituals. From this perspective, country life may readily be viewed as backward, or at the very least outmoded, because, among other things, everyone living there is still an all-rounder. Peasants, and also their wives, are represented as offering themselves as jacks (and jills) of all trades and as failing precisely to realize that in doing so they stymie every form of progress in the countryside. With his ridiculous behavior the peasant on stage only confirms the city-dwelling public in their ideas.

The abele spelen serve the same purpose, even though in three of the four plays these values are directly projected onto an idealized life of chivalry. The fourth play is distinctive only in its choice of subject matter, the ritualized struggle between summer and winter known from rural folklore, but it is adapted in a similar manner to serve the objectives of the urban middle classes. The knights and young damsels in the first three plays are preoccupied with concerns of an urban nature. These primarily relate to (real or assumed) differences in religion or social rank that present obstacles to true love as the basis for starting a family.

The urban population had a more pragmatic attitude toward these matters; it wanted social mobility based on merit, industriousness, and talent to be as fluid as possible. In this way an abel spel such as Lancelot of Denmark (Lanseloet van Denemarken) could serve as a didactic manual for the leading bourgeois circles, showing how to secure an appropriate marriage, with special consideration for problems regarding social rank. The crux of the tale is that everything is possible in principle, provided that the practices of the city’s new matrimonial mores are observed. Lancelot, the Prince of Denmark (not to be confused with Lancelot, the knight of Arthur’s Round Table), fails to meet the demands of this social code when he falls in love with a maiden of more humble origins. Following the false counsel of his malicious mother, he deflowers the maiden, having promised to marry her, and then abandons her. At the end of the play he will be left even more miserable than in his state of frustrated despair prior to committing the treacherous deed.

The girl flees into the forest, deeply traumatized by the brutish theft of her virginity. Then a second knight makes his entrance, representing the new bourgeois worldview and therefore, to put it mildly, cutting a rather curious figure in this courtly setting. Before he catches sight of the young woman he voices his ideas about work and investment. First he explains why he is roaming through the forests, but his motives are different from those of Duke Otto in the 1516 prose version of Henry and Margarita of Limburg, who was seeking solace for his melancholy. This knight has been out hunting for four days already and has not even “caught a rabbit,” as he puts it himself. He concludes: “I am ashamed at such bad luck, / And that I should lose my labor so.”

Not only is his adventure in the forest explicitly motivated by profit — he is not just hunting as an exercise in the art of war — but he speaks in tradesman’s terms. His investment of time has not yet brought him any success, which is why his efforts (aerbeit, “work, labor”) thus far have been wasted. But then he spies the damsel in distress beside a fountain and exclaims enthusiastically that it seems he might still find success: “Ah Lord God, should I catch her, / My labor would not be in vain.” This knight, who turns out to be a very likeable fellow, does not react by asking the damsel how he might help, what is amiss, which scoundrel has abused her, or some other gallant platitude. Nay, he has a nose for profit, in the form of this eventual reward for all his investment of time and effort. Once this mentality has been made clear to the audience he consoles the girl and asks her to marry him.

The knight tellingly couches his proposal in contractual terms, the most obvious way to certify a human relationship for him and his social milieu. That is why he also defines the young woman as a commodity: as a wife, he says, she is more valuable than a wild boar, even one of gold; and he promises her a life of opulence in his castle in exchange for carnal pleasures. The fact that she has lost her virginity — which would have been a virtually insurmountable problem in court circles — presents no problem for him whatsoever. This knight is very practically minded. He is in need of a wife, she is beautiful, and why would anyone get excited about a blemish on her reputation?

The young woman starts to talk in commercial terms herself. She turns her lost virginity into a selling point by comparing herself to a richly blossoming tree from which a falcon has plucked a single blossom:

Now let us go into this grove,

Sir knight, and let us talk a little.

I pray you understand my riddle:

In courteous words I will tell you all.

Look at this tree shapely and tall,

How gloriously it blossoms out.

Its noble smell goes all about

The orchard and the lovely dell.

So sweet it is, and grown so well,

That all this orchard it doth adorn.

If now a falcon nobly born

From high upon this tree flew down,

And picked one flower, only one,

And after that never one more,

Nor ever took but that one flower,

Now pray you tell me faithfully,

Would you therefore hate the tree?

To buy it would you therefore scorn?9

This knight and young lady are guided by morals that are unlike the traditional codes of honor of court culture. The new concern is to enter into an advantageous marriage for love, but that marriage must of necessity be founded on practical considerations and the careful weighing of investment, work, and profit.

The emergence of a distinctive urban literature involves articulating the philosophical and moral values that acquired special significance in urban society. At the time we are discussing, these values were invariably couched in terms of the qualities a worthy citizen should possess and the goals he ought to pursue. A citizen had to be useful, practically minded, industrious, inquisitive, ambitious, adventurous, self-supporting, enterprising, frugal, smart, individualistic, opportunistic, moderate, reasonable, modest, and self-controlled. It would be a mistake to think that these virtues were “discovered” in town and city. Individualism, hard work, and making a career are not among urban society’s exclusive achievements, no matter how often the city dwellers of the late Middle Ages attempted to present them as novel. Most of the qualities mentioned date back to classical antiquity, many were later adopted at court, and we encounter almost all of them in the earliest monastic milieus. Overlaps in these moral codes are a constant, since the prominent feature of such a mind-set is that it is constantly cross-pollinated.

Broadly speaking, the authors of classical antiquity posited the need for reason and emotional control as a guiding principle for worldly life, together with instructions for the methodical management of household affairs (oeconomia). The latter was also a particular concern of the monastic orders, with their emphasis on diligence and discipline, and the efficient timekeeping required to achieve this. The ideal of constituting a self-sufficient community belongs in this milieu, too. Finally, the lone adventurer who takes on the world and vies with fate (fortuna) initially flourished in the midst of courtly culture, as exemplified by the epics of chivalry.

The unique thing about the city of the late Middle Ages was that a highly original and effective moral code was formulated with a new purpose, based on the legacy handed down by the classical, biblical, and medieval past. It is rooted in an almost primitive survival strategy that, if necessary, subordinates all values to the will to survive, without the help of, but also unhindered by, traditions, rules, inherited power, or the threat of physical or spiritual punishment. This new package of virtues is generated, tested, and propagated in the literature of the late Middle Ages.

This allowed the tale of Reynard the Fox, which in Willem’s thirteenth-century version was so closely associated with the world of the court, to enjoy a new lease of life in the city. With only minor adaptations, the text could inspire audiences to identify with the essence of an evolving civic morality. Of course, various versions of the tale of Reynard had already been produced during the Middle Ages, adapted to meet the demands and expectations of audiences from diverse social strata. Whereas in Willem’s poem the parody on chivalric literature and the courtly world in general is paramount, in later versions we see this focus gradually disappear, and it has become virtually imperceptible in the prose version. Conversely, the tendency to moralize increases, leading to further exaggeration of the human traits of the animal characters.

But who would have enjoyed this ruthless humiliation of the traditional might of aristocratic courts, effected by a widely detested animal to boot? The supposition that we are dealing here with some form of literary self-reflection in these courtly circles is surely belied by the harshness of the satire, which makes a mockery of the principles of feudal society and its courtly machinations. But is that fox really such a despicable creature? His cunning in the face of the dull-witted authorities and their brazen selfishness must have seemed irresistible, especially for those upwardly mobile groups in urban society that were striving to establish a new kind of power structure by means of their economic wealth and marriage politics. In any case, it is hard to see how a medieval text could have become popular if it depended entirely on an anti-hero with whom nobody would ever want to identify.

The late medieval public’s liking for texts that demonstrate how an individual can take on the whole world with practical ingenuity and be self-reliant under all circumstances is indeed striking. The common feature of all these often comical exercises in cunning is that the hero flouts all traditional values and is not weighed down by courtly codes of conduct or any other behavioral norms, although he gleefully respects them if he might profit by them. Reynard is a perfect embodiment of this mentality. He knows the ceremonial posturing of the dispensation of justice like the back of his paw, so to speak, and unerringly exploits the system’s weaknesses. But he remains courteous where that achieves results, for example in the presence of King Nobel the lion and his wife Gente, rendering them defenseless against his boundless scams.

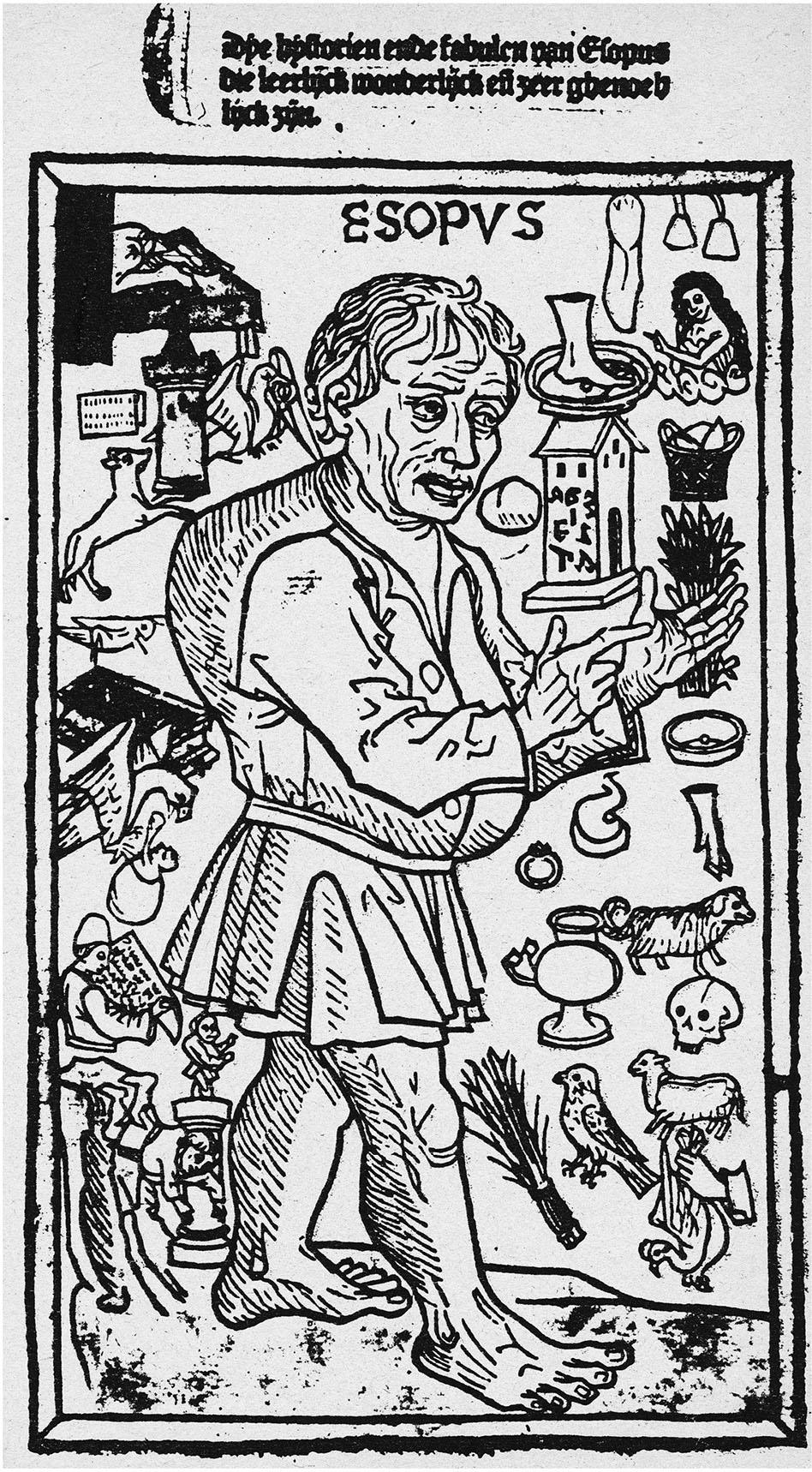

It is as if the text about Reynard’s triumphs prepared the way for the later tales of resourceful villainy, which, in step with the expanding powers of the urban elites, enjoyed increasing popularity. These tales were about the antics of hyper-individualists, such as Marcolph, Aesop, pseudo-Villon, Aernout, Everaert, Uilenspiegel, the Pastor of Kalenberg, Virgil, Heynken de Luyere, and many more. The edition of Aesop’s Fables (Esopus) printed in 1485 features a prologue which recommends the work as a manual for self-preservation based on personal shrewdness, thus underscoring the proven usefulness of the animal fable to demonstrate those very values and life skills.

Title page of the Histories and fables (Historien ende fabulen) about Aesop, printed 1485. The Hague, Museum Meermanno-Westreenianum.

The Repertoire of Popular Festivities

By devoting so much attention to the adaptations of ideologies and subject-matter from the traditionally higher social milieu we may risk losing sight of the fact that urban literature of the time poached a very wide range of materials from popular culture. True, the sources available to document and analyze this bottom-up cultural filtration are much less plentiful. They are also harder to interpret, since, unlike sources on court culture, the materials used are very rarely still in existence in their original form. But the vast majority of city-dwelling burghers originated, directly or indirectly, from the countryside and therefore had first-hand knowledge of popular culture. Also, migration to the urban centers persisted after the Middle Ages, and there continued to be plenty of agricultural activity and tending of livestock within the walls of every town and city, even though space was limited. In other words, the city stood in the middle of the countryside.

Many immigrants and their descendants kept their own culture alive, certainly at the level of the urban neighborhoods, and this culture was only very gradually absorbed into more general urban interests. The forms and rituals were often preserved in essence, even though the aims and orientation acquired an urban signature. We see that phenomenon most clearly in the youthful diversions associated with the charivari. In the countryside, bands of youths could administer an alternative form of justice in the name of their forefathers and with community endorsement. In town and city their activities were limited to jeering and demanding money from those who had contravened urban matrimonial mores, and their rabble-rousing was gradually assimilated into the more general pre-Lenten celebrations. The authorities in many cities also organized these traditionally rowdy gangs of as yet unsettled youngsters into official neighborhood associations and later on even molded them into chambers of rhetoric, which strove to become the exclusive organizers of urban literary life.

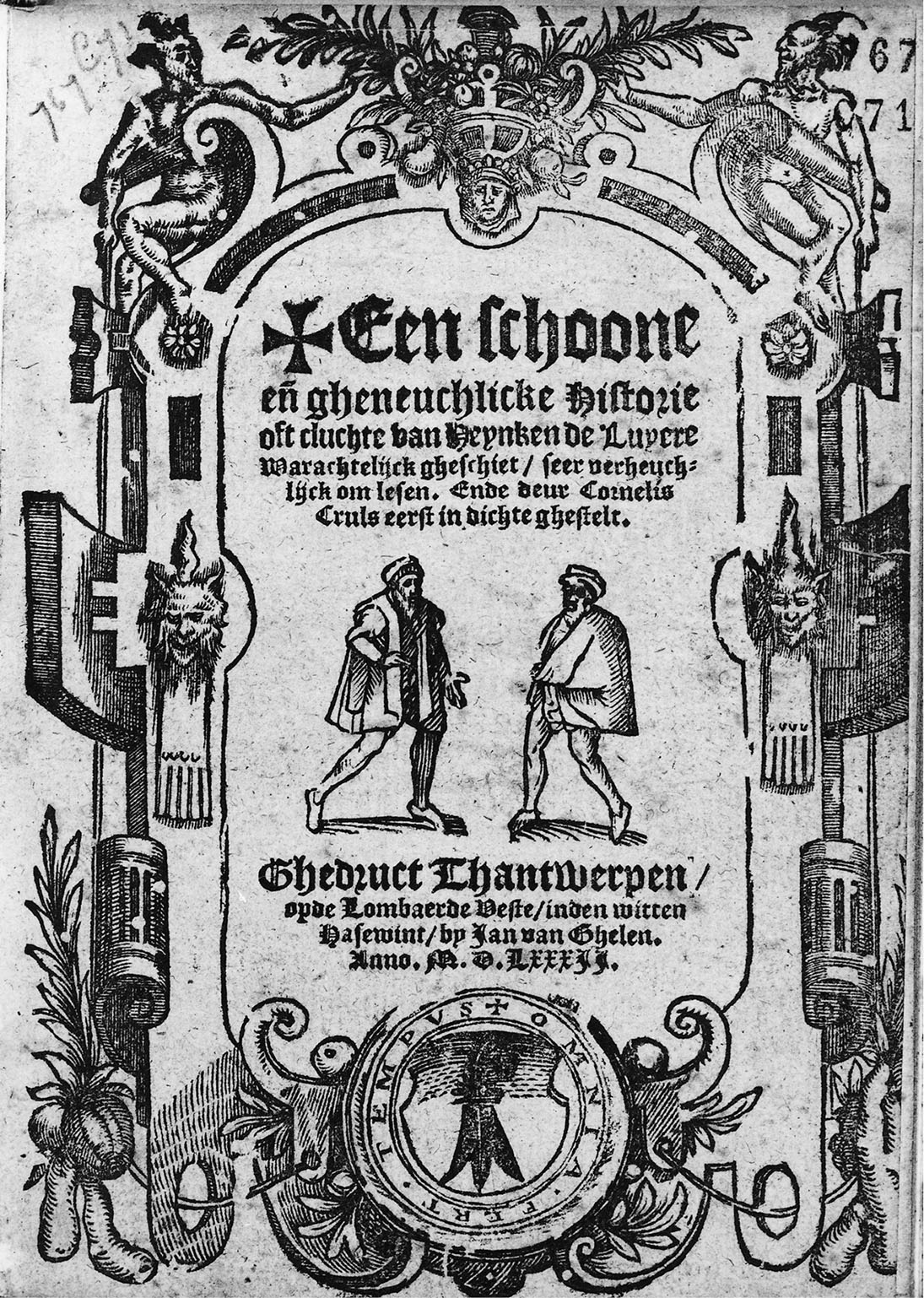

Title page of Heynken de Luyere by Cornelis Crul, written c. 1540, printed 1582. The Hague, Royal Library.

Such textual materials have come down to us only when official culture found their subject-matter sufficiently interesting to commit them to paper — usually in an adapted form — and to employ them for events that the authorities themselves organized. This sometimes involved gathering whole collections of folk texts, primarily songs, which were given a new lease of life by the printing press. The so-called Antwerp Songbook (Antwerpse Liedboek), printed in 1544, contains a substantial corpus of such lyrics. Within this collection, material that has its origins in an anonymous folk tradition is usually indicated by the legend “an old song.”

One such example is Of the Beans (Van den boonkens), which denounces all the aforementioned transgressors of the desired marital order. Its short refrain is an insistent reminder that such folly is caused by the scent of the flowering bean plant. As the ritual described also involves the incineration of bean plants at the doors of offenders, producing a malodorous stench, there is a plausible connection:

Men with locks of purest white,

They marry a young maid,

Dance on two stools with all their might,

True sottishness displayed!

And their limbs are all so stiff,

They can’t be counted on to lift.

What makes them move is gout’s sore pain,

Their noses run, their old eyes water,

And those itches in the main

Are an everlasting bother.

When pollen wafts upon the air,

You get more than your fair share!

The original rituals, and those of rural fertility rites in general, are easily discerned in the extant repertoire for feasts of inversion such as Carnival, the purpose of which was to teach, by means of instigating a temporary topsy-turvy order, how life in the real world ought to be conducted. We find such texts preserved in manuscripts and early printed works. They reveal how, for the duration of the festivities, townspeople sought to dispel prevailing fears concerning hunger, sex, cold, and the devil by presenting all manner of jokes and pranks that were scatological or deleterious in nature.

These texts extol the virtues of extreme lasciviousness in a heavily ironic manner, thus indicating by inversion what is expected of every good citizen under normal circumstances: industriousness, thrift, moderation, and self-sufficiency. The best-known specimen in Dutch is the Guild of the Blue Barge (Gilde van de Blauwe Schuit), dated 1413, which includes the mock statutes of a fraternity that organizes the annual Carnival celebrations in various cities. The painter Hieronymus Bosch and the German humanist Sebastian Brant drew extensively on such performances for their moralizing portrayals of fools. Bosch’s The Ship of Fools is one of his most famous paintings, while Sebastian Brant’s The Ship of Fools (Das Narrenschiff) was translated into almost every Western European language soon after its initial publication in 1494.

The Blue Barge (Die Blauwe Schuit); burin engraving by Pieter van der Heijden after Hieronymus Bosch, 1559. Brussels, Royal Library Albert I.

The rhyming text about the Guild of the Blue Barge describes in detail who is allowed to become a member of the guild and on what conditions, who is excluded, and when membership must be revoked. Candidate members are subdivided into categories reminiscent of the three medieval “estates” but incorporating later variants specific to urban society, namely profession, age, and marital status.

The crux of the text is a severe critique of any sections of society reputed to behave in a manner no longer desirable within the city walls. Following the spirit of the poem this critique is presented ironically, so the points of criticism assume the character of absolute prerequisites for becoming a member of the guild. And this is taken to such an extreme that even mishaps and calamities that are beyond one’s control are presented as the consequences of individual decisions to live wantonly and sinfully. For example, the Carnival Prince extends an invitation to poverty-stricken nobles with the recommendation to indulge their proclivity for drunkenness, fornication, and gambling to their heart’s content within the guild:

First of all, about those men,

Knights or grooms, whose fief or land

Is sold for money in the hand.

Or to the Lombard make their way

And pawn their goods, but cannot pay

To get them back, too poor, it seems.

They eat their grain while it’s still green.

Their income they can’t wait to spend,

They play at being gentlemen,

And every year they sell some land,

And let their debts get out of hand.

Of indolence they make a habit,

Buying all they can on credit.

They’ve no need of moderation

For they are our prodigal children.

Such insinuations must have hit hard in late-medieval society, where members of a now redundant landed gentry could no longer make ends meet and struggled to participate in the urban economy. The city, however, showed little patience for these nouveaux pauvres, who had nothing but a title to offer a merchant’s daughter. They were contravening one of the principal pillars of urban ethics, namely independence and self-sufficiency. A burgher provided for himself and did not depend on granting and receiving favors. He buys and hires, and does not need to knock on any doors for help. Whoever is reduced to that is harshly reminded of his personal responsibility, with the implication that it is all his own fault. The aged and the infirm are dealt with equally harshly in these ruthless carnival rituals, which were above all meant to define the urban community’s interests.

The invitations continue in a similar fashion, being extended to church prelates who abuse their privileges, lusty nuns and monks, the idle children of the wealthy, women of loose morals, aging spinsters, and many others besides. All of them are welcome, on condition that they diligently continue to overindulge their gluttonous and destructive behavior. Indeed, the guild was designed for that very purpose. The fact that, in principle, this involves behavior that could yet be rectified to correspond with the bourgeois order is underscored by the description of the circumstances that would secure release from membership: marriage, wealth, or wisdom.

This defines “tearaway” behavior (the term recurs several times) as a rite of passage: to join well-ordered society you must become a settled burgher by getting married, accumulating wealth and, especially, gaining wisdom, thus quashing the chaotic foolishness of the upside-down world. In addition, it is made clear that serious crimes are an entirely different matter. The Guild of the Blue Barge prescribes the rules of behavior that grant entry to bourgeois society as it had become established by the end of the Middle Ages. The formation of urban elites required the suppression of folk culture. Murderers, arsonists, and traitors do not fit into any social order whatsoever, and they are excluded also from the inverted order of the Guild of the Blue Barge.

These performances and festivities must have been a significant feature of urban society in the late Middle Ages. Mock rulers and mock kingdoms cropped up everywhere, not just in urban neighborhoods but also in villages and hamlets. The temporarily established mock kingdoms assumed all the trappings of true order, so as to transform them into their opposites. The mock sovereign issued decrees (“commandments”) and administered justice, and the kingdom had a mock ecclesiastical hierarchy with all due pomp and circumstance. All these components were depicted and acted out with abandon. Some of the texts that were used as repertoire for such performances — or at least describe them — have been preserved.

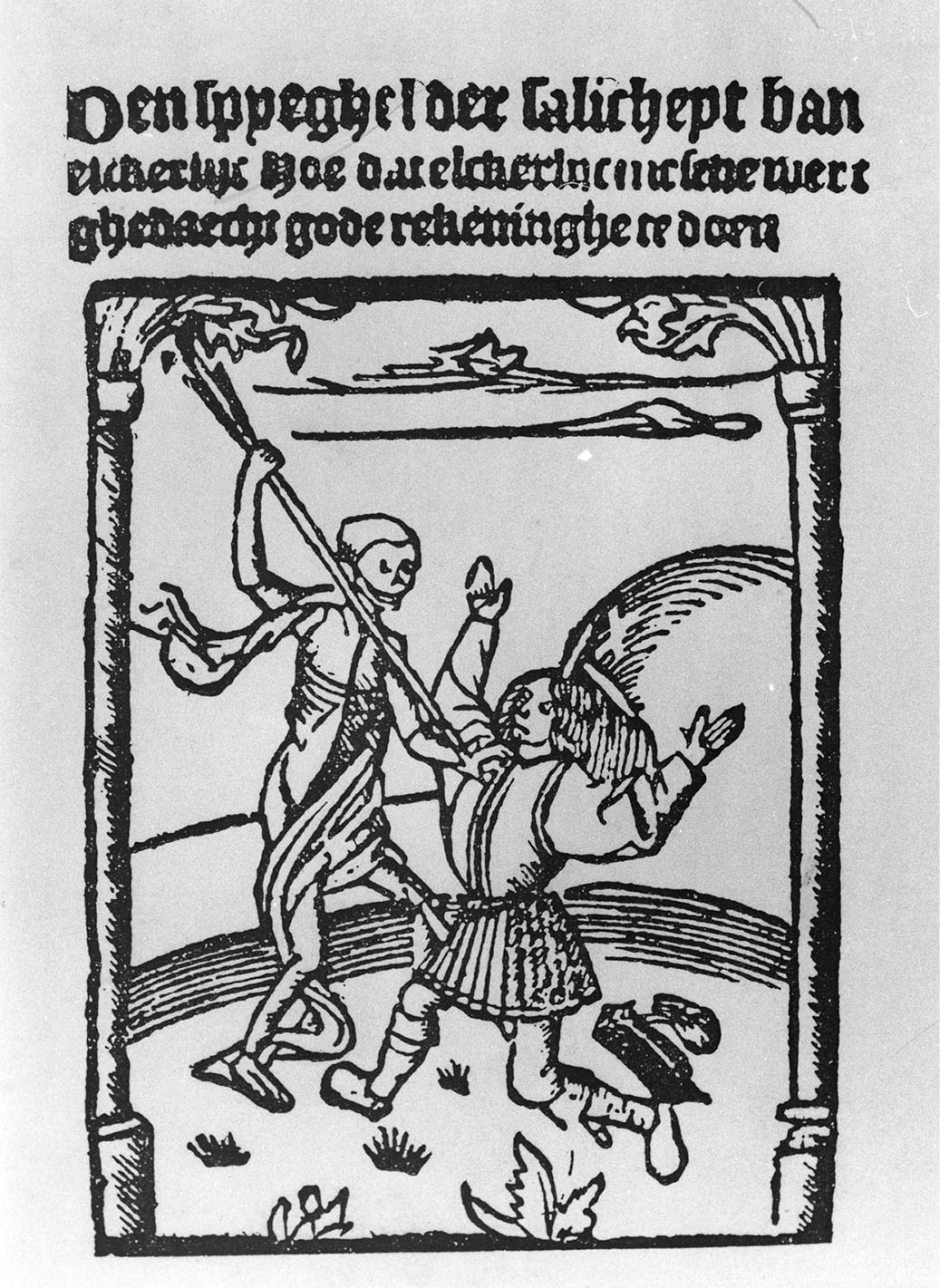

Fragment of From the Potty Pulpit (Dit is van den scijtstoel), a work possibly used as toilet paper. Amsterdam, University of Amsterdam Library.

Several mock sermons intended to embellish the alternative Mass have come down to us. One example is From the Potty Pulpit (Dit is van den Scijtstoel), a text in which a merrymaker, garbed as a priest, mounts the pulpit and launches into the well-nigh obligatory scatological and sexual wordplay by treating the pulpit, the usual place to preach God’s truth, as a privy. He then holds a learned disquisition, liberally sprinkled with pig Latin, about materials for wiping one’s behind. He warmly recommends mussel shells, the Fool’s Stone, and even snowflakes. In another text we are blessed with a benediction of farts, and as subjects of the mock kingdom we must swear allegiance to the new sovereign as follows: “Now stick your fingers up your behind, then kiss them.” The priest explains that we can only follow his wishes and those of God by drinking ourselves into a stupor and fornicating the whole time. Entry into hell is guaranteed, he concludes emphatically.

Highly popular throughout Western Europe was a type of mock sermon in which the venerated saint in the upside-down world went by the name of Saint Nobody. This redoubled the irony, because his incessantly repeated commands established a full-blown society that was a match for one based on Christian virtues. “Nobody” urged you to drink yourself silly, commit adultery, and squander your money:

Take pains to understand me well,

The ranks of the heavenly kingdom swell

With drunkards and wastrels, I must explain.

So, dearest, if saving your soul is your aim,

Then spare neither goods nor legacy,

Though your children might starve in misery.

Swig and swill at every opportunity.

The mock preacher reiterates this message time and again: blow your money, drink yourself into a stupor. A little further on he continues:

One may reach the heavenly kingdom by boozing

For those who guzzle too much beer or wine

Release a soul from purgatory each time.

Drink in order to save souls and gain entry into heaven. This is followed by a listing of foods personified, some of which would not appear on the table until Easter, as they were forbidden during Lent: Peter Ox, Roger Rabbit, and John Capon, as well as John Cod, Harry Haddock and Tommy Thornback, and Trish Fig, Kelly Apple, and Betty Raisin. Dozens of these names were concocted, resulting in enumerations that were highly comical and well suited to a spectacular delivery, during which the mock priest probably also attempted to represent these foodstuffs graphically. The text concludes with a blessing of the gathered crowd in the name of Sanctus Drincatibus. Drink as much as you can in his honor, until you’re so sozzled that the booze oozes out of you unnoticed!

The moralizing objectives are evident in these texts. The advice to deviate from accepted moral values serves to demonstrate that such inversion would lead to nothing but chaos, and that those who fail to mend their ways will surely end up in hell. The generous sprinkling of scatological folklore serves as an instrument to invert the established order, which could then be denigrated and ridiculed with ease. The names of the mock rulers already give a clear indication of the intended objects of derision, the targets in the real world that, using hilarity and gravity in equal measure, they wish to pillory or attempt to render tolerable in the year to come. We hear from the gentlemen Empty-Hands, Shabby, Uncle Lombard (a nickname for a pawnbroker), Hunger-Mount, Rowdy-Rule, All-Wrong, Seldom-Rich, and Grim-Church, as well as from pseudo-saints such as Saint Have-Not, Saint Snot-Glob, and Saint Flat-Broke. It is obvious that the main objective here was to dispel the fear of cold, poverty, and hunger as well as to gain control over the sinful behavior that would lead to such predicaments.

These texts, and with them our knowledge of the accompanying carnival celebrations, have been handed down via the well-to-do middle classes, who plundered the popular culture on their doorstep and tailored it to serve their own purposes. A farce from the mid-sixteenth century known as The Fool’s Dubbing (De sotslach) provides an illustration. The Fool tempts the Farmer, who is dissatisfied with his life of drudgery, into joining the Guild of Fools. After some hesitation the Farmer enters the Guild by way of a parody on the dubbing of a knight. The Farmer and the Fool combined stand for everything from which the established burghers wished to distance themselves. On his way to market with half-rotten eggs and poultry, the Farmer initially mistakes the Fool for the Devil, and he is so terrified that he loses control over his bodily functions. The Fool promptly ridicules him as a drunken nincompoop for soiling himself with rotten eggs and his own excrement. The Farmer also rides roughshod over all the rules of etiquette, sometimes literally, for instance when he bursts in on a distinguished company of people at table in his unwieldy clogs. His uncouth behavior is of course the reason he is well suited to join the Guild of Fools.

The inversion of the bourgeois virtues to be cultivated in the real world continues with the Fool listing the privileges of membership: no more work, food in abundance, and endless freeloading. That suits the Farmer down to the ground, especially when he thinks about his miserable life with his ill-tempered and nasty wife, and he eagerly renounces all wisdom in order to be dubbed a fully fledged fool. He then bursts out into a wild song and dance. He has just one question for the Fool: where does he find the guild’s headquarters, so that he can collect his cap with bells and his provender? So the Fool gives him directions, and his answer makes it abundantly clear that foolishness leads to abject misery:

To Churlishness, a city world-renowned,

Lying past Cockaigne, a mile at most,

Through Wretchedness you travel to the coast

Where Mister Drifter ferries folk at speed.

One skipper is called Want, the other Need,

They toil to bring you quickly, safe and sound.

The moral is laid on thickly in this farce: anyone who relinquishes wisdom and thus becomes a complete fool, who does nothing in life but sing, dance, and guzzle, will eventually slip into utter destitution.

A similar exploitation of rural culture can be found in the texts about the Land of Cockaigne. These tales are spun around a kernel of compensatory fantasies of gluttony and laziness in a paradise of worldly abundance. It is easy to discern the rural origins of these tales, as people in the countryside had endured drudgery and a frantic fear of famine since the early Middle Ages. The set ingredients of the Land of Cockaigne included animals presenting themselves in ready-roasted or ready-cooked form (all one has to do is open one’s mouth and take a bite), absolute idleness, and edible architecture — houses and fences constructed from luxurious victuals. This narrative material proved useful to other social strata and was adapted to allay their prevailing fears, feed their cherished fantasies, and trumpet their particular interests. In the new urban milieu, the Land of Cockaigne was recast as the more familiar mundus inversus. In other words, townspeople seized upon the Land of Cockaigne in order to moralize.

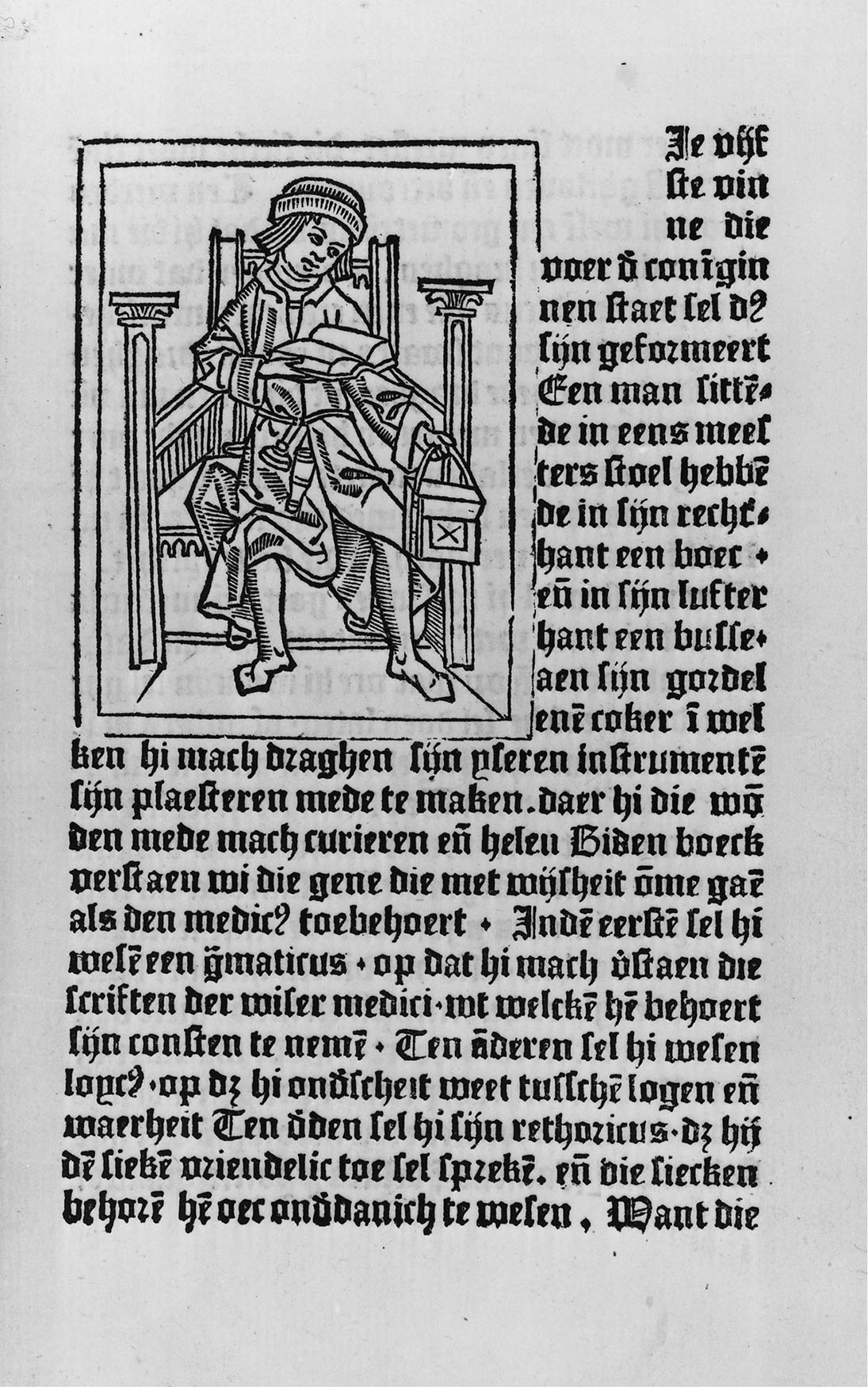

Damaged leaf from The Land of Cockaigne (Dat lant van cockaengen). London, British Library.

The two oldest rhyming texts, which are distantly related to French thirteenth-century fabliaux, add a new dimension to the compensatory fantasy of gorging. They are now also employed as a warning against the sin of gluttony: the behavior in this preposterous Land of Plenty is the opposite of the moderation and self-control prescribed in ethical treatises and moralistic sermons. For example, the tables in the Land of Cockaigne are fully laden at all hours of the day, so people can gorge whenever they desire:

In all the streets there you will find

Tables with food of every kind.

On tablecloths of spotless white,

Bread and wine, oh what a sight!

And, moreover, meat and fish,

And everything that you could wish.

You can eat and drink the livelong day

And never even have to pay,

As is the custom here with us.

Handbooks of Penance leave no doubt that eating whenever one feels the urge is one of the features of the cardinal sin of gluttony. The sin of sloth is inverted in a similar manner: in the Land of Cockaigne those who sleep longest earn the most, which also serves as a topical critique of the usurers from whom the urban work ethic sharply differentiates itself.

The Land of Cockaigne portrayed in these texts is further tainted by a suspicion of heresy, since they claim the Holy Ghost as Cockaigne’s lord and ruler. The Holy Ghost had long been associated with the thousand-year reign of peace and prosperity of which the Book of Revelation speaks. Unorthodox millenarianist ideas about the imminence of Utopia gave rise to blasphemous practices throughout the Middle Ages. Lay preachers frequently proclaimed the imminence of this biblical paradise on earth, in which poverty and inequality would be consigned to history. Their exhortations to start preparing for such a kingdom often sparked social unrest due to the accompanying imposition of community of property and free sex, mirroring the situation that was supposed to have existed in the Garden of Eden. For the church, such fantasies, and the resulting deeds, smacked of heresy.