1. Constable’s England? This is, in fact, Brzostowo village in eastern Poland. Small herds steward a landscape crawling with invertebrates (Chapter 3). Andrzej Gorzkowski Commercial / Alamy Stock Photo

1. Constable’s England? This is, in fact, Brzostowo village in eastern Poland. Small herds steward a landscape crawling with invertebrates (Chapter 3). Andrzej Gorzkowski Commercial / Alamy Stock Photo

2. Dairy desert. A typical cattle lawn in Sussex, with not a wryneck, red-backed shrike or cuckoo in sight (Chapter 3). LatitudeStock / Alamy Stock Photo

3. It’s all in the soil. A black-tailed godwit on a fence post in the farmland of Texel, in the Netherlands (Chapter 3). AGAMI Photo Agency / Alamy Stock Photo

4. Food flow. The rich woodland glades of Hungary’s Bukk Hills (Chapter 3). Rob de Jong

5. Europe’s Serengeti. Letea Forest, in Romania’s Danube Delta (Chapter 4).Nature Picture Library / Alamy Stock Photo

6. Wild parkland. Dawn in the Kanha National Park, India (Chapter 4). GM Photo Images / Alamy Stock Photo

7. Scrub management. The rich scrub-grasslands of the Serengeti, Tanzania, with zebras leading the management regime (Chapter 4). Anca Enache / Alamy Stock Photo

8. Forgotten stewards. Wild horses graze a wooded meadow in the Chernobyl wilderness, straddling Ukraine and Belarus (Chapter 4). kpzfoto / Alamy Stock Photo

9. Rivers in charge. In Poland’s Biebrza Marshes, winter flooding provides an enormous stimulus for regrowth in the following spring (Chapter 4). Benedict Macdonald

10. Wild coast. A coastal plain in the Netherlands – a landscape driven by water, succession and grazing animals (Chapter 4). Europe-Holland / Alamy Stock Photo

11. English wilderness. A fledgling ‘Serengeti’ of our own, the Knepp Wildland Estate in Sussex (Chapter 4). Charles Burrell

12. Last stand. Cuckoos were once birds of the wider countryside, but they have retreated into the wooded grasslands of Dartmoor (Chapter 5). Each dot on the map represents a sighting of a cuckoo. Mike Daniels / Devon Birds / Google Maps

13. Wild Scotland. The regenerating woodlands of Alladale (Chapter 8). Nature Picture Library / Alamy Stock Photo

14. Singing in the shade. The kingdom of the nightingale, Bradfield Woods, Suffolk (Chapter 9). Steve Aylward & John Ferguson / Suffolk Wildlife Trust

15. Let it rot. A maze of dank, rotting floodplain trees – one of the last UK strongholds of willow tits, Dearne valley, South Yorkshire (Chapter 9). Geoffrey Carr

16. Hazel maze. The dense joinery of low branches used by marsh tits in a hazel coppice in the Cotswolds (Chapter 9). Bob Gibbons / Alamy Stock Photo

17. Deer desert. A conservation woodland in Gloucestershire’s Forest of Dean (Chapter 9). Colin Underhill / Alamy Stock Photo

18. Lost forester. A primitive-breed cattle bull wanders through the Letea Forest, in the Danube Delta (Chapter 9). Nature Picture Library / Alamy Stock Photo

19. Bleeding out. The extent of grouse moors in England (Chapter 11). The orange areas show Moorland Association data; the red is a Friends of the Earth best estimate of the area specifically covered by grouse moors; the blue shows historic flooding. Source: https://friendsoftheearth.uk/page/map-grouse-moors-england. Adam Bradbury / Friends of the Earth

20. Grouse farming. This heather moorland in Aberdeenshire is burned in rotational patches (Chapter 11). Nicholas Gates

21. Mosaic moorland. Juniper and birch mingle with heather on the Rothiemurchus Estate in the Highlands (Chapter 11). Nicholas Gates

22. Moors without fire. Store Mosse, in Sweden. Here, with no heather burning, ‘moorland’ birds survive in greater diversity than on any grouse moor (Chapter 11). Martha Wägeus / Store Mosse National Park

23. Sustainable grouse moors. A man and his dog hunt willow grouse in Sweden (Chapter 11). Arterra Picture Library / Alamy Stock Photo

24. The not so famous grouse. A willow grouse, the same species as Britain’s red grouse, creeps through a natural heather glade in Scandinavia (Chapter 11). Nature Picture Library / Alamy Stock Photo

25. Pelican possibility. A remote colony of Dalmatian pelicans nests within the safety of Romania’s Danube Delta (Chapter 12). Stelian Porojnicu / Alamy Stock Photo

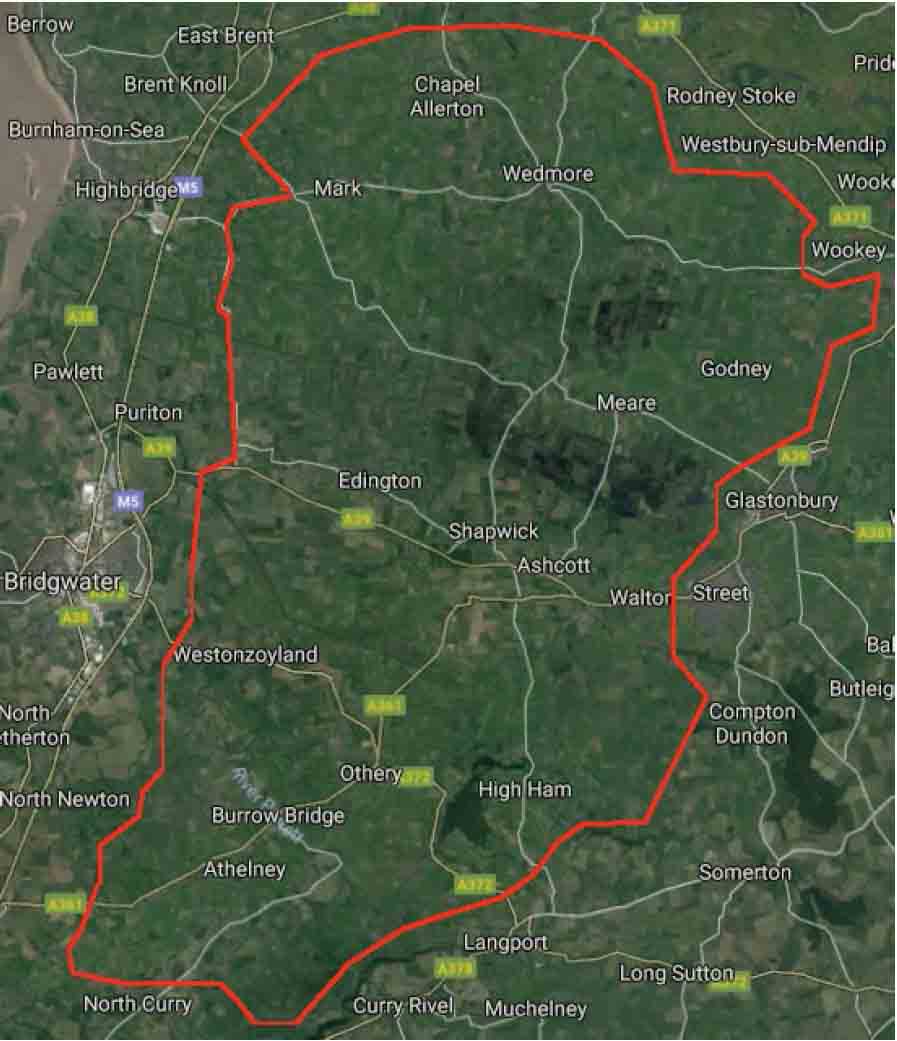

26. A question of scale. The red area sketches out an area of low-lying, unprofitable dairy farmland in Somerset that could be transformed into a wetland ecosystem large enough for pelicans (Chapter 12). Benedict Macdonald / Google Maps

27. Living with nature. A house in a Hampshire village, 1914 (Chapter 13). The Francis Frith Collection

28. Sterile Britain. The same Hampshire house as in Figure 27, photographed in 2017. Now cleansed as a result of ecological tidiness disorder (Chapter 13). Benedict Macdonald

29. Wild village. Zywkowo, a ‘stork’s village’ in Poland (Chapter 13). Hans Winke / Alamy Stock Photo

30. Beavers know best. Without any of the usual tools in the UK conservation toolbox, beavers create a diverse wetland free of charge on Tayside (Chapter 14): a) 1 year after beaver release, and b) 12 years after beaver release. CC BY 4.0 Adapted from: Law, A., Gaywood, M.J.,m Jones, K. C. Ramsay, P. & Willby, N. J. 2017. Using ecosystem engineers as tools in habitat restoration and rewilding: beaver and wetlands. Science of the Total Environment 605–606: 1021–1030. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.06.173