THE UPPER PALEOLITHIC AS HISTORY

Our history has always … been up to us.

MORE THAN ANYONE ELSE, V. Gordon Childe (1892–1957) helped shift the subject of archaeology from artifacts to people. Nineteenth-century archaeology had been dominated by the classification of artifacts, organized into stratified sequences and interpreted within a framework based on a vague theory of progress. Beginning in 1925 with the publication of The Dawn of European Civilization, Childe transformed the artifacts into a historical narrative: “a preliterate substitute for the conventional politico-military history with cultures, instead of statesmen, as actors, and migrations in place of battles.”1

Throughout his career, Childe searched for the appropriate framework to interpret the archaeological record from a historical perspective. In The Dawn, he applied the concept of archaeological culture to the artifacts, and it was this innovation that most impressed his colleagues in Britain. Childe had borrowed the concept from the German archaeologist Gustav Kossinna (1858–1931), whose views on the biological or racial basis of cultural progress enjoyed the public approval of leading Nazi officials.2 Childe had rejected such ideas in his book, which instead emphasized the diffusion of ideas, and was distressed by their link to the archaeological culture concept. In the months after Adolf Hitler came to power in March 1933, Childe denounced the racial doctrines behind Kossinna’s notion of culture in papers and lectures.3

In 1934, Childe revised an earlier synthesis on the Near East to include two major social and economic upheavals in prehistory: the rise of agriculture and the development of urban centers. He later referred to them as the Neolithic Revolution and Urban Revolution, respectively. They were modeled explicitly on the concept of the Industrial Revolution of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and, by analogy with the latter, were tied to a significant increase in population density.4 Although Childe’s thinking about the Neolithic and Urban revolutions was later attributed to the influence of Marxism and Soviet archaeology,5 it was actually another step in his continuing effort to approach the prehistoric archaeological record from the perspective of a historian. In 1934, he shifted away from culture history and turned to the analysis of technological innovation, economic change, and their impact on population growth.

In the following year, Childe visited the Soviet Union, where he was inspired by the ongoing effort to apply a Marxist framework to the archaeological record. This framework was largely derived from the cultural evolutionists of the late nineteenth century, especially Lewis Henry Morgan. Although Marx and Engels had accepted it as the ethnology of their day, by the 1930s the unilinear evolutionary stages postulated by Morgan and his contemporaries had long been abandoned by ethnologists outside the Soviet Union. Nevertheless, Childe promptly published Man Makes Himself (1936), which combines his prehistoric economic revolutions with a Marxist viewpoint—simultaneously articulating his current thinking on prehistory and battling the racial archaeology of the Nazis.6 He later wrote What Happened in History (1942), resurrecting the antiquated terminology of the nineteenth-century evolutionists by labeling the epochs preceding civilization as “savagery” (Paleolithic) and “barbarism” (Neolithic).7

In later years, colleagues wondered how serious Childe was about his commitment to Marxism and support for the Soviet Union; he often wielded them to shock people. Throughout his life, he was a shy and isolated person who never married or formed intimate friendships; some thought that his reticence reflected his rather odd physical appearance. He had emigrated from Australia to England, where he remained an outsider. He subsequently accepted an academic post in Edinburgh, where he repeatedly scandalized the local regime and later published—as a “parting insult”—a Marxist prehistory of Scotland. He wore strange hats and exotic clothing. Arriving at an expensive hotel, he demanded to know why copies of the Daily Worker were not available to guests. In public lectures, he outraged his audience with quotations from Comrade Stalin.8

Childe is probably best remembered for his Marxist and cultural evolutionary views. He became a victim of his own success, and Man Makes Himself and What Happened in History remain his most widely known works. When cultural evolutionism was revived in North America in the mid-twentieth century, he was solemnly acknowledged for his earlier writings. But Childe continued to think about an appropriate framework for the archaeological record, and during the last decade of his life, he developed something rather different from his earlier perspective. His principal biographer, Bruce Trigger, observed that “this was a period of lonely innovation, much of which was too easily dismissed by contemporary British archaeologists as more examples of ‘Gordon’s naughtiness.’ It was also a period when major shifts occurred in his thinking, which produced real or seeming contradictions in his writings … an important creative phase … that significantly altered and developed his earlier contributions.”9 Childe was influenced by the British philosopher and historian R. G. Colling wood (1889–1943), and his later publications reflect Collingwood’s idea list perspective.10

Collingwood was himself an isolated and iconoclastic figure. He practiced philosophy, history, and historical archaeology during a period when natural science had almost completely overwhelmed the philosophy of history. This was due in part to the impact of Darwin’s ideas, but had deeper roots in the Enlightenment. Two popular historical works of the time were Oswald Spengler’s Decline of the West (1926–1928) and the first volumes of Arnold Toynbee’s massive Study of History (1934), both of which treat societies and cultures as organisms that develop through a natural life cycle. Collingwood regarded these studies as manifestations of the “tyranny of natural science” over history, which he believed to be “a special and autonomous form of thought.”11 He placed the human mind at the center of history: “Unlike the natural scientist, the historian is not concerned with events as such at all. He is only concerned with those events which are the outward expression of thoughts, and is only concerned with these in so far as they express thoughts” (italics added).12 Shortly after the posthumous publication of Collingwood’s book The Idea of History (1946), Childe wrote History (1947), which Trigger described as a turning point, a small volume in which he melded Collingwood’s vision of history with his own interpretation of Marxism, emphasizing the role of invention and its relationship to social and economic change.13 History, he wrote, is fundamentally a “creative process,”14 and several years later, he openly rejected the cultural evolutionary schemes of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries for their implicit “magic force that does the work of the concrete individual factors that shape the course of history.”15

Childe’s later thinking was articulated in Society and Knowledge (1956), published a year before his death.16 In this most interesting and thoughtful of his many books, he presented a theory of progress based on the observation that human societies increase their control over the environment by creating new technologies. By improving their ability to manipulate the world, societies acquire knowledge about the way it works (that is, the “sensory hand”), which they tend to explain in terms of the technologies (for example, the mechanistic worldview that developed in Europe after 1200).17 Childe stressed the social character of both invention and the accumulation of knowledge. But the central theme of the book is human creativity, which he defined as “not making something out of nothing, but refashioning what already is.”18 He had at last found the appropriate framework to interpret the archaeological record as a historical narrative.

By defining history in terms of thought—”all history is the history of thought”19—Collingwood made prehistory, or at least a portion of it, part of history; as a historical archaeologist specializing in Roman Britain, he wrote about reconstructing the past “from documents written and unwritten.”20 And as Childe incorporated Collingwood’s ideas into his later writings, he repeatedly referred to artifacts as“concrete expressions and embodiments of human thoughts and ideas.”21 The goal of the archaeologist, he stated, is “to recapture the thoughts” expressed by the people who created the artifacts, and he noted that, by so doing, the archaeologist “becomes an historian.”22 He emphasized that the accumulation of knowledge—the history of science—had begun long before the invention of writing.23

In theory, history as defined by Collingwood and Childe can be extended back to the Lower Paleolithic, especially since the appearance of the Acheulean bifaces 1.6 million years ago provides archaeologists with an externalized mental representation. Before the emergence of the modern mind, however, the lack of creativity manifest in the archaeological record makes for a rather dull narrative. It was not until the advent of the super-brain and modernity—of potentially infinite creativity in both symbolic and nonsymbolic form—that human societies began to accumulate and interpret knowledge on the scale that Childe had in mind. The interval described in chapter 3, corresponding with the Middle Paleolithic in Eurasia and the Middle Stone Age in Africa, seems to lie somewhere in between. It contains evidence of innovation and accumulating knowledge, but until the later African Middle Stone Age, it is very limited.

The archaeological record of the first 40,000 years of the modern mind is traditionally classified as the Upper Paleolithic (Later Stone Age in Africa). Like the other subdivisions of the early archaeological record, the term “Upper Paleolithic” is itself a piece of fossilized thought. It was proposed in western Europe during the mid-nineteenth century, when all prehistory was viewed as an epoch of gradual progress.24 As more sites were excavated during the final decades of the nineteenth and the early years of the twentieth century, some archaeologists began to see a major break in the record at the start of the Upper Paleolithic.25 Soviet archaeologists inserted this break into the Marxist evolutionary scheme that Childe initially embraced and later abandoned.26 But at the beginning of the twenty-first century, the original classificatory framework remains in place. Upper Paleolithic is used here as a label with the sole virtue of familiarity.

The reclassification of the Upper Paleolithic as history is more than a matter of semantics and formal definition. It reflects recognition not only that the process of accumulating knowledge about the external world through creative innovation was already under way, but that the technological knowledge acquired was substantive and significant. It was knowledge that had a major impact on the human population; Upper Paleolithic settlements reached unprecedented size and complexity, and overall population density almost certainly increased. Moreover, it seems to have provided the requisite base of knowledge for what followed after the Upper Paleolithic: agricultural villages and urban centers. There is reason to doubt that these developments would have taken place without the accumulation of technological knowledge during the preceding 40,000 years.27

Upper Paleolithic history also reflects recognition that the accumulation of knowledge is the essence of the historical Process—with or without written records—and that “prehistoric” archaeological data can provide a significant part of the story. We do not know a single word spoken by the peoples of the Upper Paleolithic, but we do know a great deal about their thoughts. Artifacts that offer evidence of technological knowledge—tools, weapons, facilities, and structures—are filled with information derived from the collective mind of each Upper Paleolithic society. These modified pieces of organic and inorganic material are literally part of the mind, remnants of hierarchically structured thought that existed (and still exists!) outside individual human brains. To understand history, Collingwood asserted, the historian discerns the thoughts of the past “by rethinking them in his own mind.”28

Moreover, changes in artifacts and features observed over time (other than stylistic changes) provide a record of how thought progressed over time and how knowledge of the external world and how it works developed during the Upper Paleolithic. By the later phases of the period, people in many places understood more about physics, chemistry, and biology than had their predecessors, as well as how to apply this knowledge to achieve desired ends. The archaeological record of the late Upper Paleolithic reveals that people thought differently than they had earlier—their minds had changed.

The Age of Art and Music

Is the conception of nature and of social relations which underlies Greek imagination and therefore Greek [art] possible when there are self-acting mules, railways, locomotives and electric telegraphs?

The most mysterious and fascinating period in the modern human past is the interval between 50,000 and 30,000 years ago,29 which is often referred to as the early Upper Paleolithic (or, simply and affectionately, the EUP). Along with the final phase of the African Middle Stone Age, it represents the initial outing of the super-brain and the modern mind. It may have been uniquely primitive, relative to later periods, with respect to technology because the people of the EUP were just beginning to create the tools, weapons, and other gadgets that would eventually be commonplace among foraging societies (especially at higher latitudes).30 Adding to the mystery of this period is that EUP sites are often small and hard to find, particularly in places where caves and rock shelters are absent.

If the technology is primitive, the visual art and musical instruments of the EUP are remarkably sophisticated. Visual art includes sculptures of humans, animals, and a mixture of both, as well as the earliest dated cave drawings and paintings. The creative character of these iconic representations, which exhibit a potentially infinite array of combinatorial variations within a complex hierarchical structure, was presented in chapter 3 as an unambiguous manifestation of the modern mind.31 And although the structure of EUP music is unknown, the subtle design of the wind instruments reveals an impressive knowledge of musical sound (figure 4.1).32

What is striking about the art and music of the EUP is not their prominence and sophistication compared with those of the later phases of the Upper Paleolithic, but their contrast with the technology of the time. During the middle and late Upper Paleolithic, the technology became considerably more complicated, while the art and music—at least the design of the musical instruments—appears to have remained fundamentally unchanged.33 The gulf between the structural complexity of art and of technology became even more pronounced after the Upper Paleolithic, and it has been especially stark in the machine era (and although music did become more complex, this trend seems to have been related to developments in the technology of musical-sound production). Moreover, written records show that the structure of language also remained fundamentally unchanged in later periods of accelerating technological complexity. The contrast between art and language, on the one hand, and technology, on the other, reflects the fact that they represent different parts of the mind. Art and language are almost entirely internal to the super-brain or collective mind; they are the primary means of super-brain integration. Through the medium of visual art, individuals project artificial representations that bear a rather obvious relationship to the internal natural visual representations of the catarrhine brain. Language is projected through a medium as well—the human voice—but this masks its true character. Language is integrated with sensory cognition (auditory, visual, and tactile [in the case of braille]), but its core elements have no sound, color, or feel; they probably reside in the neural pathways of the neocortex itself. Technology is both internal and external to the mind. Its internal aspect is the sharing of artifacts or thoughts about artifacts among individuals or groups. Its external aspect lies at the interface of the mind and the world outside the mind, where the mind engages the world. Most human technology is designed with nongenetic information, and an artifact is analogous to an organism—the phenotypic expression of that information. By the beginning of the EUP, modern humans had evolved a mental capacity analogous to sex—potentially infinite recombination of the bits of information.

Figure 4.1 The earliest evidence for the creation of musical sounds and structures is at least broadly coincident with the earliest evidence for the production of visual art and creative technology, and surprisingly sophisticated musical instruments (“pipes”) are dated to more than 30,000 years ago, including this specimen, recovered from Geissenklösterle (southern Germany). (Redrawn from Francesco d’Errico et al., “Archaeological Evidence for the Emergence of Language, Symbolism, and Music—An Alternative Multidisciplinary Perspective,” Journal of World Prehistory 17 [2003]: 41, fig. 11b)

Gordon Childe was one of many thinkers who noted the apparent connection between the clocks and other machines that arose in western Europe after 1200 and the mechanistic worldview that accompanied the new technology. He sensed a link between technology and the way the world is interpreted through language and art, although neither he nor anyone else has been able to explain precisely how it works. It seems clear, nevertheless, that as the structural complexity of technology has increased—bringing with it revelations of the ways in which the world works—the world has been reinterpreted in new ways (even if the structural complexity of the systems employed to explain it have remained fundamentally unchanged). The worldview of the early civilizations was probably as different from that of the hunter-gatherer societies that preceded them as it was from that of western Europe after 1200.34

If the technology of the EUP was uniquely primitive in comparison with those of the later phases of the Upper Paleolithic and of hunter-gatherers of the post-Paleolithic era, did EUP people perceive and explain the external world in their own peculiar way? And, given the widely held assumption among historians of technology that worldview affects the capacity for innovation,35 did the way in which the EUP mind interpreted the outside world influence the pace of technological change during this mysterious period? It is impossible to answer these questions because we can only guess at the content of the EUP worldview and the meaning of the few symbols yielded by its archaeological record. As we study the pattern of change in all areas of material culture between 50,000 and 30,000 years ago, however, I believe that we should keep these questions in mind.

Some archaeologists view the EUP as “transitional” or intermediate between the late Middle Paleolithic and the later phases of the Upper Paleolithic. This idea is related to a once widely held notion that living Europeans evolved directly from the local Neanderthals. It remains popular among those who believe that the Neanderthals contributed genetically and/or culturally to modern humans. But it has become more difficult to sustain in recent years in light of the discoveries of EUP sculptures and paintings, as well as the new analysis of musical instruments, all of which suggest that the people of the EUP had “the same cognitive and communication faculties” as living humans. There are still dramatic differences between the EUP and the later Upper Paleolithic, but they seem to be confined to technology and economics—the same sort of differences apparent in historic times that reflect the gradual accumulation of new inventions and their impact on population density and settlement size.

Another factor that contributes to the false impression of the EUP as a transitional stage is the profusion of archaeological sites in many parts of northern Eurasia that date to this interval and contain a mixture of typical Middle and Upper Paleolithic artifacts. They are assigned to industries like the Uluzzian in Italy and the Szeletian in Hungary and other parts of central Europe. The artifacts include some types known only in Upper Paleolithic (or late African Middle Stone Age) industries, such as shell ornaments and bone points, alongside classic Middle Paleolithic stone-tool forms, such as scrapers made on flakes and small bifaces. In some cases, the mixture is thought to reflect the adoption of Upper Paleolithic traits by local Neanderthal groups; in others, it is viewed as the gradual development of technology by modern humans slow to abandon the traditions of the past.36

A more parsimonious explanation of the Middle Paleolithic tools in these sites is that they represent simple expedient forms that were used for certain tasks, especially the butchery of large-mammal carcasses. Modern humans continued to make such tools long after the EUP, and they are particularly common at sites in North America where large mammals were killed and butchered. The source of the confusion probably lies in the inherent biases of the west European archaeological record, which is heavily skewed toward habitation sites in caves (where these tool types are present but not abundant). For historical reasons, the interpretive framework of western Europe was applied far beyond its boundaries. In eastern Europe, where caves are often absent, a wider range of sites are found; some of them are kill-butchery locations that predictably contain many Middle Paleolithic tool types. In short, the presence of such tools in EUP sites probably has little to do with the Middle Paleolithic.37

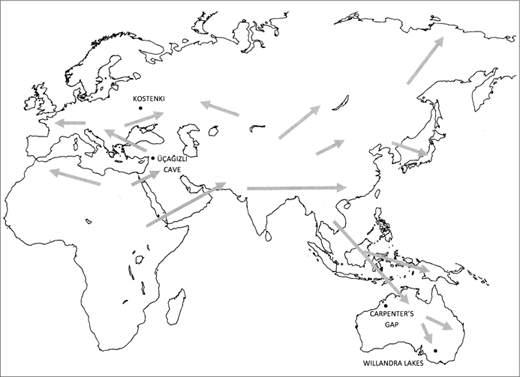

Ironically, some of the earliest known traces of the EUP outside Africa are from distant Australia. When modern humans began to expand out of Africa, they apparently moved eastward across tropical Eurasia, perhaps initially along the coast of the Indian Ocean (figure 4.2).38 Archaeological evidence of the south Asian migration remains to be found, but both artifacts and human skeletal remains show up in Australia by 50,000 years ago. Their presence alone is significant, since even the shortest water crossing of 55 miles from Southeast Asia indicates some form of watercraft, which seems to have precluded earlier settlement. Freshwater-shell middens are dated in both southeastern Australia (Willandra Lakes) and Papua New Guinea to more than 40,000 calibrated radiocarbon years ago, while evidence of marine-resource use is slightly younger.39

Figure 4.2 Modern humans spread out of Africa and into Eurasia and Australia roughly 50,000 years ago. Their rapid occupation of a wide variety of habitats and climate zones appears to have been largely a consequence of their unprecedented ability to redesign themselves with technology.

As in northern Eurasia, personal ornaments of perforated shell and other materials are found in the earliest phase of the EUP in Australia. And although musical instruments have yet to be recovered from an EUP context there, very early evidence of visual art is known at Carpenter’s Gap (northwestern Australia) in the form of a fragment of a rock-shelter wall—apparently painted with ocher—that fell into deposits dated to roughly 46,000 to 39,000 years ago.40 As elsewhere, technology remained relatively simple during the EUP in Australia. Points and other implements made of bone are generally scarce and thus far unknown from the earlier phases of the EUP (although this may be a function of sampling error and preservation bias).41

Above latitude 30° North, the EUP materializes on Africa’s doorstep in the Levant also roughly 50,000 years ago. The archaeological record in the eastern Mediterranean is different from that in Australia and illustrates how, as they dispersed out of Africa into different parts of Eurasia and Australia, modern human groups began to develop their own local historical peculiarities. The succession of industries in the Levant between 50,000 and 40,000 years ago also illustrates the potential for rapid innovation and constant change.

Some isolated bone implements are found in this industry, as well as the ubiquitous personal ornaments in the form of perforated marine shells.42 But the principal changes are manifest in the stone-tool technology, which began with a shift toward the production of long blades—in addition to triangular points—from prepared (Levallois) cores. As before, the stone points were attached to wooden shafts as spear tips, but the blades were chipped into tools that are considered generally typical of the Upper Paleolithic—especially end scrapers and burins. The technology gradually moved toward the mass-production of thin bladelets and narrow points that were struck off the cores with a “soft hammer” (bone or antler). The gradual character of the transition has been nicely documented in recent excavations at Üçagğizli Cave on the southeastern coast of Turkey.43

The series of industries in the Levant after 50,000 years ago may illustrate something even more fundamental about the modern human mind than the capacity for rapid innovation. It is difficult to explain the changes, especially the later changes, as a result of external factors, such as climate or interactions with other species. The inhabitants of the Levant had begun to make their own history—driven by the internal dynamics of human society and the collective mind. While the initial changes in stone-tool technology could conceivably reflect the response of an incoming population from northeastern Africa to novel environments and/or local competitors (Neanderthals), it is hard to account for the subsequent shift to soft-hammer production of small blades and narrow points in either terms. The Neanderthals seem to have vanished from the Levant by 50,000 years ago, and the climate—although oscillating—was generally mild.44

Both climate change and nonhuman species have had effects on human societies throughout prehistory and history, but after the advent of modernity other factors have been at work. In historic times, following the emergence of the early civilizations, the primary external factor in shaping societies probably has been the impact of other societies. Climate change often has altered the course of history, such as the consequences of the Little Ice Age on European society and the impact of El Niño on the Classic Maya. Catastrophic events like the volcanic eruption on the island of Santorini roughly 3,600 years ago in the eastern Mediterranean also represent a periodic external factor. And other organisms, especially pathogens such as Pasteurella pestis (bubonic plague bacillus), have had an impact on history.45 But there have been many developments, such as the invention of the printing press and the cotton gin, with significant consequences for human societies that cannot be plausibly ascribed to global warming, falling asteroids, or killer bees. These internal factors probably were at work during the EUP.

Most of what we know about the EUP is based on archaeological sites in Europe, which is a reflection of the long history of discovery and research in that part of the world. For the Upper Paleolithic, this is especially true in western Europe, where Paleolithic archaeology had its beginnings. It also reflects the high visibility of Upper Paleolithic sites in caves and rock shelters—nicely preserved and easily discovered—which are predominant in southwestern France and northern Spain but also known in Italy, Germany, and Austria. In central and eastern Europe, open-air sites are more common, and, in some areas, rock shelters are completely absent. Outside Europe, a number of Upper Paleolithic sites—including EUP sites—are known from southern Siberia.46

The northern bias of the EUP archaeological record has one advantage: it offers a rich source of data on how modern humans, recent migrants from the equatorial zone, adjusted to cooler and more seasonally variable environments. Their skeletal remains reveal anatomical proportions typical for living peoples of the tropics—tall and thin, with long limbs—who are adapted to warm climates.47 Such people are more susceptible to cold injury and loss of core body temperature (hypothermia), and they require cultural buffering in the form of insulated clothing and heated shelters. One of the most striking aspects of the wide geographic dispersal of modern humans 50,000 years ago is how the biogeographic “rules” of climate adaptation did not apply. Human groups living in higher latitudes eventually developed stockier bodies and shorter extremities, which reduce heat loss and the potential for frostbite, but during the EUP, adaptation to northern environments was achieved almost entirely through the creation of new technologies.48

It may be significant that the earliest traces of the EUP in Europe coincide with a warm-climate oscillation. According to the Greenland ice cores, which provide the most detailed and comprehensive record of climate change in the Northern Hemisphere for the period (based on oxygen isotope fluctuations), temperatures increased sharply a few centuries after 48,000 years ago. Greenland Interstadial 12 began with a warm peak that was followed by a gradual cooling until colder climates returned shortly before 44,000 years ago. Artifact assemblages dating to this interval that bear a close resemblance to the oldest EUP industry of the Levant—that is Levallois blades and points with typical Upper Paleolithic tools—are found in southeastern and south-central Europe. Other than isolated bone implements, there is little evidence of novel technology, although this may be due largely to the biases of preservation, sampling, and site function. Most of these sites are thought to be stone-tool workshops.49

Because only isolated human skeletal remains that cannot be firmly identified as those of particular species are found in these sites, some archaeologists are hesitant to ascribe them to modern humans. In theory, the artifacts could have been made by local Neanderthals, and at least a few archaeologists are convinced that they were. Such a view is compatible with the widely held notion that the European Neanderthals produced several industries comprising a mixture of Middle and Upper Paleolithic artifact types.50 However, there is consensus that the next batch of artifact assemblages to appear in southeastern Europe, at roughly 45,000 years ago, were most probably made by modern humans. The sites also lack diagnostic human skeletal remains, but they contain small bladelets and narrow points similar to those that were produced in the Levant before 40,000 years ago, which are associated with indisputably modern human remains in Lebanon, as well as other typical EUP artifact forms. Often referred to as the Proto-Aurignacian industry, this group of assemblages is found in caves and open-air sites in Italy and the Balkans.51

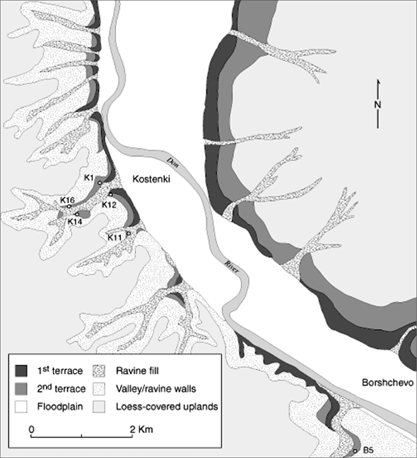

The EUP in Europe between 45,000 and 40,000 years ago is best represented on the East European Plain at a concentration of open-air sites on the Don River about 250 miles south of Moscow. The sites are located around a series of ravines incised into the west bank of the main valley around the villages of Kostenki and Borshchevo (figure 4.3). The EUP remains are buried in a thick bed of silt and fine rubble, inter-layered with lenses of carbonate formed by seeps and springs. The oldest levels lie beneath a volcanic-ash horizon deposited by an immense eruption in southern Italy (Campanian Ignimbrite) that spewed a cloud of ash across much of southeastern Europe. The ash is firmly dated to 40,000 years ago and is represented in the Greenland ice cores, where it precedes a major cold-climate event.52

Figure 4.3 Much of the evidence for settlement on the East European Plain in the early Upper Paleolithic is derived from a group of sites around the villages of Kostenki and Borshchevo on the Don River (Russia).

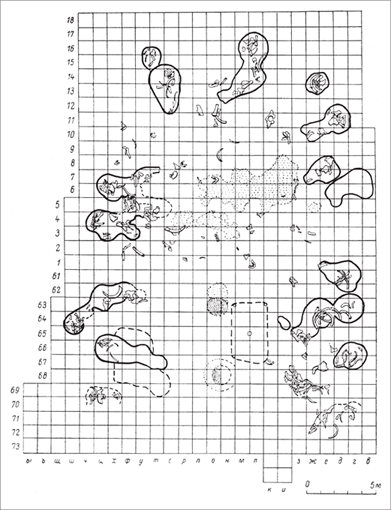

Mammoth bones were discovered at Kostenki centuries ago, but the associated Paleolithic artifacts were not recognized until 1879. In the 1930s, Soviet archaeologists excavated massive feature complexes of middle Upper Paleolithic age; the occupation floor patterns were used in the debates over the application of Marxist cultural evolutionary models to archaeology that intrigued Gordon Childe. Although older EUP occupations were known as early as 1928, they were investigated on a large scale only after World War II, under the direction of A. N. Rogachev (1912–1981).53 Without the extensive earlier excavations of the younger levels, the EUP layers probably would have remained largely unknown because most are deeply buried and rarely exposed by erosion or other disturbances.

The excavations by Rogachev and more recent investigations exposed EUP occupation floors in many of the Kostenki sites (and lately at Borshchevo), ultimately revealing a unique “EUP landscape” across which people moved, camped, and engaged in various activities. Some of the sites represent locations where large mammals—chiefly horse, but also reindeer and mammoth—were killed and butchered. They contain the same types of stone artifacts (points, bifaces, and scrapers) found at kill-butcherysites of different times and places. Other locations show traces of camps that were occupied for at least a few days, perhaps longer, yielding a diverse array of artifacts and other debris. The Kostenki–Borshchevo sites offer a more complete view of EUP society and economy than do the caves of southwestern Europe.54

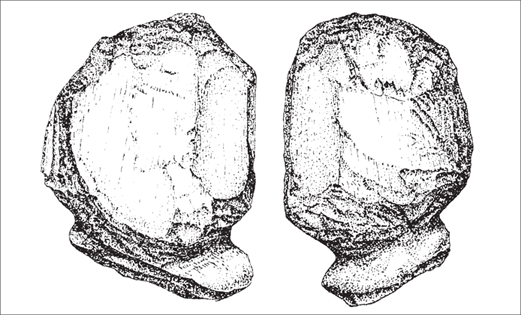

The analysis of pollen-spore samples in layers below the oldest EUP levels at Kostenki indicates an interval of very mild climates that dates to more than 44,000 years ago and may correspond to Greenland Interstadial 12. Occupation during the EUP probably began at about the same time that the Proto-Aurigancian industry arrived in southern Europe, and at least some of same types of artifacts found in Italy and the Balkans are present at Kostenki–Borshchevo. In addition to bone points and awls, digging implements made of antler and ornaments perforated with a hand-operated rotary drill were found in the lowest levels. Perhaps most significant from a technological and economic perspective are the concentrations of small-mammal remains and some bird remains, indicating the expansion of diet and most probably the production of new devices for harvesting these foods (for example, snares, nets, and throwing darts). One of the Kostenki sites yielded what may be the oldest known visual art in the world—a small piece of carved mammoth ivory that resembles a human head and neck (figure 4.4). It may represent part of an unfinished human figurine that broke during carving.

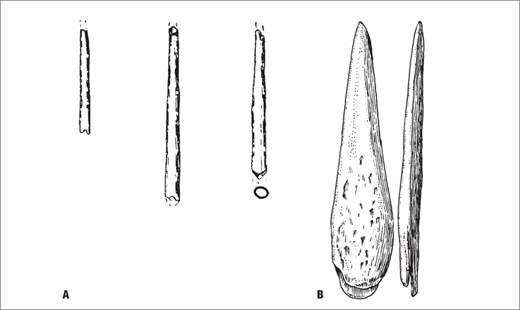

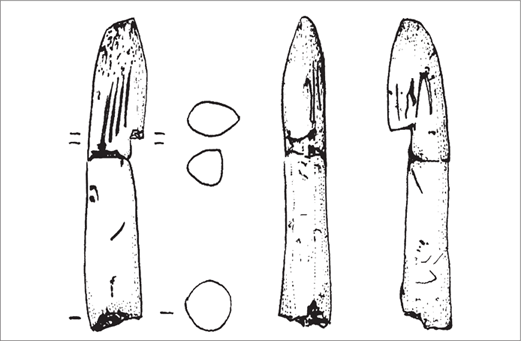

Settlement at Kostenki–Borshchevo must have ended 40,000 years ago with the Campanian Ignimbrite eruption and ash fall across the East European Plain. In some places, the ash layer is several inches thick and presumably wiped out most plant and animal life for a while. The catastrophic eruption also inaugurated a period of intense and sustained cold climate (known as Heinrich Event 4).55 During this time, the most widely known EUP industry—the classic Aurignacian—spread across Europe. Conditions were so extreme in southwestern France that trees became scarce, and the local inhabitants burned fresh bone as a substitute for wood fuel.56 On the East European Plain, which eventually was reoccupied by Aurignacian folk, eyed needles of bone and ivory provide early evidence of sewn clothing (figure 4.5A).57

Figure 4.4 The earliest known specimen of visual art is a fragment of carved ivory from Russia that is dated to roughly 44,000 years ago and appears to represent the head and neck of an (unfinished?) human figurine (height = 2 inches). (Adapted from Andrei A. Sinitsyn, “Nizhnie Kul’turnye Sloi Kostenok 14 [Markina Gora] [Raskopi 1998–2001 gg.],” in Kostenki v Kontekste Paleolita Evrazii, ed. Andrei A. Sinitsyn, V. Ya. Sergin, and John F. Hoffecker [St. Petersburg: Russian Academy of Sciences, 2002], 230, fig. 9)

Overall, the technology of the later EUP remains simple in comparison with that of later periods, however, and the size and complexity of the settlements are modest. The best-known example of Aurignacian technology is the split-base point carved from a piece of deer antler, which was designed to wedge tightly into the socket of a spear shaft, reflecting familiarity with the elastic properties of antler and the way to exploit them for improved spear construction (figure 4.5B).58 A fishing gorge from Italy indicates cleverly applied knowledge of fish behavior. Also noteworthy is the evidence for simple information technology, represented by fragments of bone and ivory that exhibit sequences of engraved marks. But many of the more complex technologies of the later Upper Paleolithic, including mechanical spear-throwers (atlatls) and high-temperature kilns, were still to come. The occupation areas of EUP sites are relatively small. Traces of former dwellings are rare and indicate ephemeral structures—tents erected with wooden poles and walls of mammal hide—apparently used for limited periods by small groups.

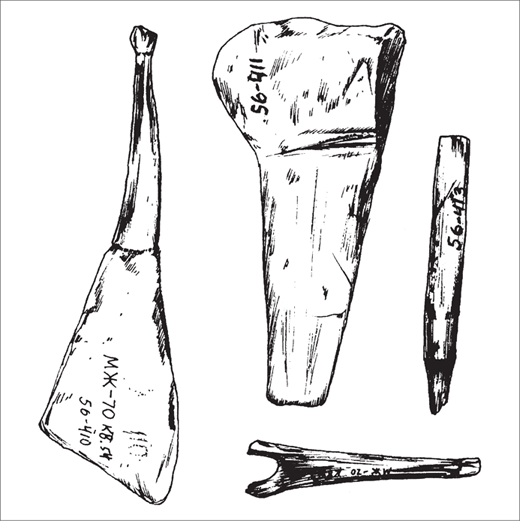

Figure 4.5 Two notable technological innovations of the EUP: (A) eyed needles manufactured from bone and ivory date to around 35,000 years ago in eastern Europe and presumably reflect the need for sewn winter clothing (after A. N. Rogachev and A. A. Sinitsyn, “Kostenki 15 [Gorodtsovskaya Stoyanka],” in Paleolit Kostenkovsko-Borshchevskogo Raiona na Donu, 1879–1979, ed. N. D. Praslov and A. N. Rogachev [Leningrad: Nauka, 1982], 170, fig. 59); (B) the split-base point was an application of the elastic properties of deer antler (redrawn from Paul Mellars, The Neanderthal Legacy: An Archaeological Perspective from Western Europe [Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1996], 394, fig. 13.1).

It is during this phase of the EUP that the contrast between the visual art and the musical instruments, which are represented by spectacular finds at sites in western Europe, becomes so striking. Controversy continues to surround the dating of the paintings in Chauvet Cave (southern France), which may be younger than previously reported, but they can be tentatively assigned to the EUP. In any case, the Löwenmensch sculpture from Hohlenstein-Stadel, as well as several recently discovered Aurignacian sculptures from Hohle Fels Cave (southern Germany), illustrate the capacity to create visual art of comparable complexity to that at Chavet. Among the objects from Hohle Fels are a female figurine and a therianthropic representation reminiscent of the Löwenmensch.59 To these may be added the famous animal carvings from Vogelherd Cave (southern Germany) and the “dancing lady” stone sculpture from Galgenburg (Austria). Finely crafted wind instruments (pipes) from Geissenklösterle (Germany) and Hohle Fels Cave are from the same time range.60

The later EUP occupations at Kostenki yielded at least one burial containing, in addition to the bones and teeth of the deceased, grave offerings in the form of ornaments and tools as well as generous inclusions of red and yellow ocher.61 If the meaning of EUP visual art remains obscure, there can be little doubt that the grave offerings pertain to belief in an afterlife. The steadfast denial of the reality of death is one of the most characteristic elements of every known culture and reflects the ghastly dilemma that confronts an organism with the faculty of abstract thought or “intentionality”—recognition of the inevitability of its own death.62 Only behaviorally modern humans seem to have faced this dilemma; there are some Neanderthal burials, but they lack any convincing traces of ritual and symbolism.63

The Gravettian: An Industrial Revolution

Technology is explained by history and in turn explains history. … It is not a linear process.

Gordon Childe may have overlooked the first economic revolution in prehistory, which arguably took place between 30,000 and 25,000 years ago in northern Eurasia. Perhaps he did not regard the social and demographic consequences as sufficiently profound, especially when measured against the tectonic upheavals of food production and urbanization.64 It seems, nevertheless, to have followed the classic pattern that Childe envisioned: a wave of technological innovation associated with significant growth in settlement size and population density. But in an Upper Paleolithic context, it is difficult to sort out the cause-and-effect relationships. Many of the innovations seem to have been unrelated to economy and population and may have been a result instead of a cause of the increased size of communities.

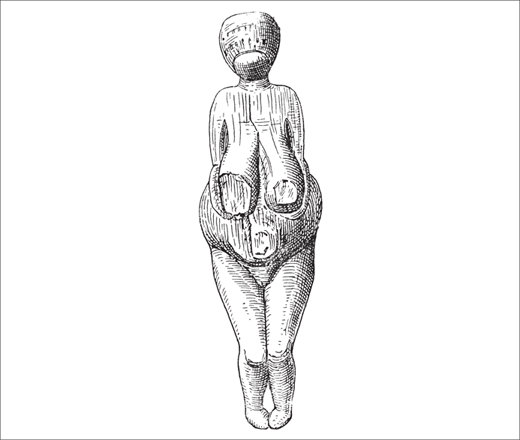

In Europe, this phase of the Upper Paleolithic (often referenced as the middle Upper Paleolithic) is associated with the Gravettian industry or culture, which is broadly distributed across the continent from Spain to Russia. The Gravettian is best known for its evocative “Venus” figurines, carved in ivory and stone and sometimes modeled in fired clay. Another characteristic and common artifact is the shouldered stone point (often used as a knife). The most significant archaeological remains of the Gravettian, however, are the often large and complex settlements comprising hearths, pits, and other features.65 These settlements suggest gatherings, at least on a temporary basis, of unprecedented size and are the principal basis for the inferred growth in population. Traces of similar settlements, although not classified as Gravettian, are found in southern Siberia at this time.66

The Gravettian emerged from the EUP immediately before the beginning of the Last Glacial Maximum (23,000 to 22,000 years ago). Climates were becoming increasingly cold and dry—especially in eastern Europe and Siberia, where isolation from the moderating influence of the North Atlantic Ocean produces more continental conditions. Periglacial steppe environments inhabited by a curious mixture of arctic-tundra and temperate-grassland species developed in these regions. Some archaeologists have suggested that the burst of technological innovation associated with the Gravettian was a response to the cooling climates.67 There is a strong correlation between technological complexity and latitude among foraging peoples,68 and at least some of the novel instruments and devices of the Gravettian reflect the presence of cold conditions.69 But the pace of technological innovation continued, and probably even accelerated, after the Last Glacial Maximum and during the period of gradually warming temperatures that followed.

As in the EUP, I suspect, internal factors were at work, for external variables such as climate and other species probably account for only some of the culture change that took place during Gravettian times. The critical question is one that Childe raised in his best known books: What accelerates innovation, and what retards it?70 What helps unleash the creativity of the mind—and facilitates the acceptance of new ideas—and what sup-presses novel thinking? History is filled with examples of societies that stagnated, some of which suffered partial or complete destruction as a consequence; there are also historical examples of societies that experienced waves of invention and dramatic change.71 Less attention has been paid to prehistoric societies in this regard, but it is apparent from the archaeological record that foraging peoples of the past underwent similar episodes of change, as well as protracted periods of stability. There may be a strong tendency among archaeologists to ascribe the advances in prehistoric societies to environmental factors, but I see no reason to exclude a role for the same variables, such as worldview and social institutions, that seem to have affected innovation in historical societies.

The population growth associated with the appearance of the Gravettian is inferred from the size and complexity of the remains of the settlements. The largest sites are thought to have been places where a large number of people (perhaps 50 to 100) assembled for at least a few days and perhaps several weeks. Although the famous Gravettian sites are in central Europe (for example, Dolní Věstonice [eastern Czech Republic]), the most extensive settlements seem to lie on the East European Plain at places like Avdeevo, Zaraisk, and the uppermost level at Kostenki 1, all in Russia (figure 4.6).72 At these sites, linearly arranged hearths are surrounded by large pits; they apparently represent integrated-feature complexes constructed during a single episode of occupation. Perhaps some or all of these temporary aggregations were designed to exploit a concentration of a food resource, such as a fish run; stable isotope analyses of human bone from several sites indicates a high level of consumption of freshwater foods.73 It seems likely, however, that these complexes were also used to reinforce social ties through rituals, feasts, and other public events.

Some of the population growth may reflect the impact of periglacial climates on flora and fauna in eastern Europe and southern Siberia. The cold and aridity were favorable to steppe species like bison and tundra dwellers like reindeer, and the large-mammal biomass may have increased relative to that in the generally milder conditions that had prevailed during the EUP. But a significant factor in population growth probably was the accumulated technological knowledge of the EUP—perhaps, especially, the late EUP—and possibly a wave of innovation that marked the beginning of the Gravettian. Novel inventions and improvements over existing technologies to harvest, prepare, and store food probably increased the number of people who could support themselves per unit area. Gravettian sites yielded the first evidence of nets, for example,74 which may have been used to catch birds, fish, and small mammals like hare. A boomerang is reported from a site in Poland.75

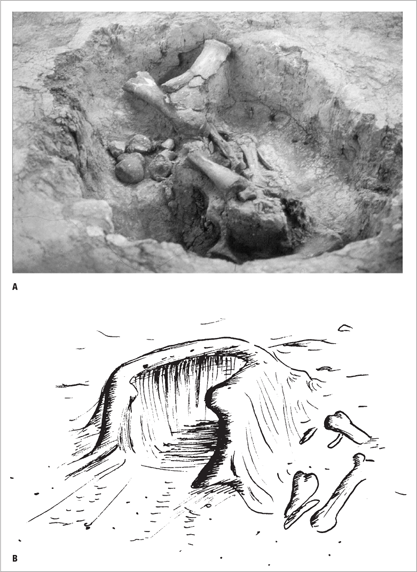

The Gravettians knew how to manipulate temperature for various purposes, and they constructed miniature worlds in which temperature could be controlled. At least some of the large pits in their sites were apparently dug down to the permafrost level during warmer months to create “ice cellars” for cold storage of perishables (figure 4.7A). In areas where wood was scarce or absent and bone was used as fuel, these pits probably were used to keep supplies of bone fresh and flammable.76 Even more impressive was their fired-ceramic technology. Modeled-clay objects were heated to temperatures of at least 1,500°F in constructed kilns (figure 4.7B).77 Like other major new technologies—for example, the weight-driven clock—the production of fired ceramics among the Gravettians seems to have been devoted to nonutilitarian purposes, such as making art objects. The practical uses of this technology did not emerge until the later Upper Paleolithic.

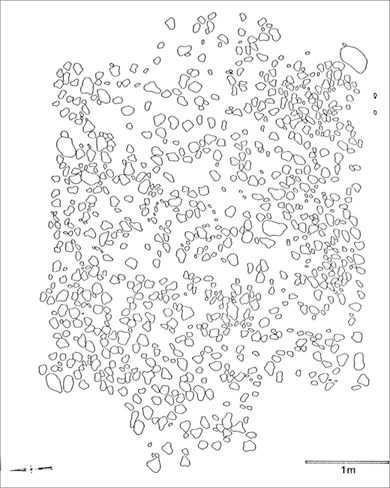

Figure 4.6 A Gravettian settlement in Russia, illustrating the complex arrangement of hearths and pits: Kostenki 1, Layer I, second feature complex, was excavated in the 1970s by A. N. Rogachev and others. (Modified from A. N. Rogachev et al., “Kostenki 1 [Stoyanka Polyakova],” in Paleolit Kostenkovsko-Borshchevskogo Raiona na Donu, 1879–1979, ed. N. D. Praslov and A. N. Rogachev [Leningrad: Nauka, 1982], 45, fig. 11)

Figure 4.7 Technological applications of temperature in controlled artificial micro-environments: (A) a cold-storage pit at Kostenki 11 (Russia) was dug to what was probably the level of frozen ground during warmer months (photograph by author); (B) an excavated kiln at Dolní Věstonice I (eastern Czech Republic) could fire clay at temperatures of about 1,500°F (redrawn from Pamela P. Vandiver et al., “The Origins of Ceramic Technology at Dolni Věstonice, Czechoslovakia,” Science 246 [1989]: 1007, fig. 7a).

The Gravettians manufactured a profusion of household items and gadgets, some of them of unknown function. They made portable lamps, fueled with animal fat, out of mammoth bone, and apparently they weaved baskets. As in EUP times, they made sewing needles from bone and ivory and fashioned small needle cases similar to those of the Inuit. The southern Siberian sites yielded figurines that depict people wearing fur suits, complete with snug-fitting hoods, which illustrate this highly complex technology for the first time. But the function of many of the carved and drilled pieces of bone and ivory in Gravettian sites is unknown; they are reminiscent of the items recovered from prehistoric Inuit sites.78

The increased population density in the Gravettian is significant because it represents the first discernible growth of the mind or super-brain. Although the expansion of modern humans out of Africa must have greatly increased the total number of individuals who contributed to the collective mind, the relative simplicity of EUP technology constrained “carrying capacity” and population density, as indicated by the consistently small size of the sites of that period. Day-to-day social interactions must have been limited to small groups, supplemented by periodic interactions among groups and individuals within wider networks (maintained by marriage and trade). As modern humans dispersed across Eurasia and Australia, they would have differentiated into local groups and regional networks—with corresponding dialects and languages—which are reflected as separate cultures in the archaeological record.

The large gatherings at Gravettian sites would have represented an expansion of the individual components of a super-brain in any given area or, at the very least, an intensification of interactions and collective thinking in a local neocortical network. As a larger gene pool offers a wider source of genetic variation, a super-brain composed of more components offers a greater potential for innovation and creativity. And as a bigger organism provides more room for hierarchically organized specialization among its cells and organs, a super-brain with more participants contains more potential for specialized thinking—for individuals devoted to specific arts or technologies. Although full-time specialists are not thought to have emerged until later times, with the advent of much larger settlements, the seeds were present in the kiln makers and tenders of the Gravettian.

The pattern of Gravettian art may illustrate another consequence of greater population density and an enlarged collective mind. An increased potential for creativity and innovation also brings an increased potential for alternative realities in the form of subversion and blasphemy. If it contains the seeds of specialized thought in some of its complex technologies, the Gravettian may also yield traces of another phenomenon that emerges vividly in later times and among more complex societies: the control of thought and behavior through public ritual and other expressions of faith.79 Childe counted it among the forces—perhaps the most important one—that inhibit innovation.80 The often elaborate burials of the Gravettians—such as the triple grave at Dolní Věestonice II, with its inclusions of ocher, charcoal, and various artifacts81—may reflect the intensification of public ritual, but it is the mobilary art that suggests a break with the EUP.

The “Venus” figurines of the Gravettian are striking for not only their subject matter, but also their ubiquity and geographic spread (figure 4.8).82 They contrast markedly with the EUP sculptures, which are few and highly individualistic. The female figurines may reflect the emergence of a Gravettian worldview, and while its content may forever remain unknown, the sameness of the sculptures across a vast expanse suggests widespread conformity to the new doctrines. Future discoveries of, say, more Löwenmenschen at EUP sites may expose the contrast as a sampling problem. But at present, a difference between the art of the EUP and that of the Gravettian is apparent, and it could be interpreted as evidence of a conservative backlash against the social and economic upheavals that accompanied the end of the EUP or simply as a response to the unprecedented cacophony of voices that arose with the Gravettian. Perhaps the wave of innovation came to a close at this point.

Figure 4.8 The Gravettian “Venus” figurines are the earliest known examples of the use of a uniform motif in visual art, although they exhibit some stylistic variation. The pattern might reflect changes in society and politics during this first “industrial revolution.”

In any case, the Gravettian way of life seems to have ended abruptly after 24,000 years ago, and at this point, climate may indeed have been the cause. Both on the East European Plain and across southern Siberia, settlement declined markedly during the Last Glacial Maximum, and some stratified sites exhibit an occupation hiatus.83 It is unclear why people appear to have abandoned the coldest and driest regions of mid-latitude Eurasia at this time. In addition to the extreme cold, food and fuel resources probably decreased, and one or more of these variables may have reached a critical threshold for human settlement. Skeletal remains of the Gravettians reveal that they retained in large measure the anatomical proportions of their EUP ancestors—an essentially tropical physique—which may have been a significant liability despite their fur clothing.84

The Periglacial Village

The archaeological course toward domestication in the Levant can be traced from around 19,000 B.C., at the peak of the last glaciation.

Climates in the Northern Hemisphere ameliorated somewhat after the Last Glacial Maximum, but temperatures remained low for several millennia (19,000 to 16,000 years ago). Significantly milder conditions prevailed during the Lateglacial Interstadial (15,000 to 13,000 years ago), followed by a brief cold interval at the end of the Pleistocene epoch, or Ice Age (which terminated after 11,000 years ago). For the first time in more than 100,000 years, full interglacial climates returned to the Northern Hemisphere.

There is broad consensus among prehistorians that warming climates and their effects on plants and animals after 11,000 years ago were the primary cause of settled village life, farming and stockbreeding, and eventually urban centers and civilization. I suggest instead that climate change had a limited role in the development of villages and cities. A more significant factor was the steady accumulation of technological knowledge during the critical millennia between 19,000 and 11,000 years ago. I further suggest that village agriculture would not have developed anywhere, at least not for many thousands of years, had the Ice Age ended 19,000 years ago, before this important phase in the history of the mind.

Building on the existing knowledge of the early and middle Upper Paleolithic mind, societies in various parts of the world achieved major breakthroughs and expanded and refined previously known technologies. They developed the earliest known mechanical technology, applied their high-temperature kilns to the production of pottery, and domesticated dogs. Many of the new technologies hint at a more settled way of life, and sites in a number of regions acquired an increasingly village-like appearance—groups of houses with walls of bone in some cases, and paved stone floors in others.85 In the Near East, where the oldest known agricultural settlements were discovered long ago, the gradual transition from hunting camps to farming villages—accompanied by significant population growth—began after the Last Glacial Maximum.86

Gordon Childe described the first artifacts with moving parts as “engines,” even though human muscles provided the power source.87 They constitute a defining difference, nevertheless, between the technology of humans and that of all other organisms. The oldest documented specimen is a fragmentary spear-thrower from Combe-Saunière I (southern France) that dates to about 20,000 years ago (figure 4.9).88 As the earliest known mechanical technology, it is predictably simple and represents a classic example of “organ projection” envisioned by the nineteenth-century philosopher of technology Ernst Kapp,89 by effectively extending the length of the arm and creating an artificial hand to increase its leverage. The bow and arrow appeared much later; wooden arrow shafts from Stellmoor (Germany) are dated to no more than 12,000 years ago.90 While the design of the arrow was a modification of that of earlier projectiles, the bow was a novel and highly imaginative piece of technology without obvious parallels or models in the natural world—its structure was generated in the mind. Human muscles still provided the energy, but it was stored in the bow and bowstring by applying knowledge of the elastic properties of these materials.

Figure 4.9 The oldest currently known example of mechanical technology is a fragment of a spear-thrower (atlatl) from Combe-Saunière I (southern France). (Redrawn from Pierre Cattelain, “Un crochet de propulseur solutréen de la grotte de Combe-Saunière 1 [Dordogne],” Bulletin de la Société préhistorique française 86 [1989]: 214, fig. 2)

More complex mechanical technology—also powered by stored energy supplied by muscles, but without a human present to release it—may be manifest in “untended facilities” for trapping small mammals. The harvesting of small mammals can be traced back to the initial phases of the EUP, but the technology behind it (perhaps nets and snares) remains unclear. Some possible trap components in the form of ivory fragments that were planed, beveled, and otherwise worked into various shapes were found at Mezhirich (Ukraine) (figure 4.10) dated to roughly 17,000 years ago.91 An effective trap reflects knowledge of animal behavior and how to exploit it and is a clever device for saving both time and labor. Thomas Hobbes would have recognized it as the first example of “artificiall life,”92 designed to function like a simple organism. Because traps would have been placed away from settlements—potentially distributed across the landscape along extensive traplines—they have unusually low archaeological visibility and may have been used much more often than an isolated specimen would suggest.

Figure 4.10 Several pieces of modified ivory recovered from Mezhirich (Ukraine) have been interpreted as trap components. Evidence for the consumption of small mammals and freshwater aquatic foods in earlier sites suggests that traps and snares probably date to the EUP. (Drawn by Ian T. Hoffecker, from a photograph in I. G. Pidoplichko, Mezhirichskie zhilishcha iz Kostei Mamonta [Kiev: Naukova dumka, 1976], 164, fig. 61)

Pottery was long associated with the rise of village farming, but it is now apparent that people were producing ceramic vessels in the immediate aftermath of the Last Glacial Maximum. A partially reconstructed pot—a wide-mouthed, cone-shaped vessel—from Yuchanyan Cave (southern China) dates to between 18,300 and 15,430 years ago (figure 4.11).93 The dates are only slightly older than those for the earliest pottery found in Japan (roughly 16,000 calibrated radiocarbon years ago) and for late Upper Paleolithic pottery in the Amur River Basin (Russian Far East), at 16,500 to 14,500 years ago.94 Some of the pots from Japan were manufactured with fiber temper and decorated with simple incised or impressed designs. Traces of secondary burning and carbonized adhesions indicate that many were used for boiling and cooking, while others may have been used for storage.95

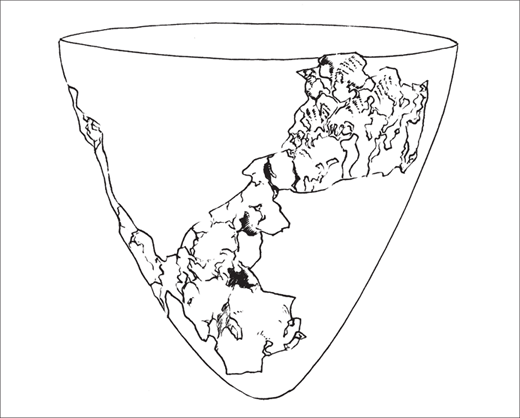

Figure 4.11 Reconstructed ceramic vessel from Yuchanyan Cave (southern China). (Drawn from a photograph by Ian T. Hoffecker)

Domesticated dogs are documented at Eliseevichi I (Russia), in the form of skulls with shortened snouts, a diagnostic characteristic that helps differentiate them from wolves.96 The skulls are associated with an occupation layer that contains remains of dwelling structures and substantial quantities of household debris, dating to roughly 17,000 years ago. More recent dogs are reported farther west at Bonn-Oberkassel (Germany).97 An analysis of mitochondrial DNA among living dogs placed their initial domestication in East Asia during the later Upper Paleolithic,98 which is not surprising given the hint of protracted settlement provided by the pottery. Dogs represent the first biotechnology—the genetic modification of an organism—even if undertaken with little sense of purpose or method.

Another realm of innovation laden with destiny is information technology. There is evidence for simple artificial-memory systems, comprising rows of incised marks on pieces of bone, in the EUP. More convincing examples have been recovered from Gravettian sites, such as Abri Labuttat (France), but the most complex forms, sometimes containing hundreds of marks, date to the later Upper Paleolithic and include specimens from Laugerie Basse and La Marche (both France) and Tossal de la Roca (Spain) (figure 4.12). These pieces reveal groups of marks—for example, short parallel strokes and notches—some which were made with different tools and perhaps at different times. A few of the marks on the Laugerie Basse piece were partly erased.99 The information recorded, and apparently deleted, remains unknown. For decades, Alexander Marshack argued that at least some of them represent lunar calendars,100 but others have questioned or disputed his conclusion. An alternative explanation is that they record the number of prey taken, and it is noteworthy that engraved images of two horses are associated with the marks on the La Marche piece.101

If tailored clothing is artificial skin and spear-throwers are elongated arms, the notational systems of the Upper Paleolithic are examples of a technological extension and enhancement of brain function outside the individual cranium. They also illustrate the use of true symbols—the shape of the marks presumably having little connection with the items recorded—in digital rather than iconic form. On some pieces, the marks seem to be organized hierarchically, and, in my view, they provide the strongest indirect evidence for the presence of syntactic language.

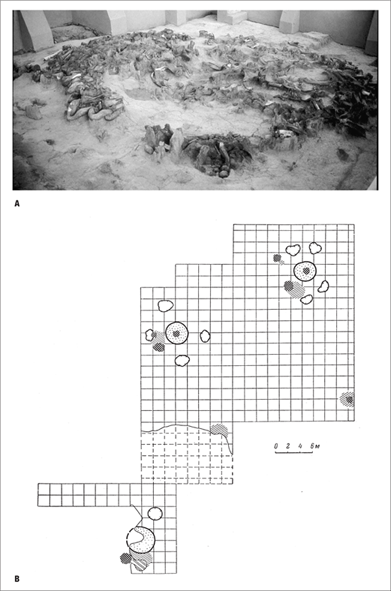

Perhaps the best evidence for increasingly sedentary life during the later Upper Paleolithic is offered by the former settlements themselves. If Yuchanyan Cave and other sites in East Asia that have yielded fragments of pottery are regarded as precursors to the village life of the post-Paleolithic era, large open sites in other regions contain the remains of village-like groups of semipermanent dwellings. The most widely known are the mammoth-bone houses of the East European Plain (figure 4.13A). In a landscape devoid of trees, the houses were constructed from the bones and tusks of woolly mammoth. Most are round or oval in plan and several yards in diameter. Former hearths (filled with bone ash) are located in the interior of each residence, along with a mass of household debris. Deep storage pits were dug around the houses, possibly for cold storage of bone or food during the warmer months. Traces of no fewer than four mammoth-bone structures have been found at Mezhirich and Dobranichevka (Ukraine) and Yudinovo (Russia) (figure 4.13B).102

Rather permanent-looking former dwellings also are known from late Upper Paleolithic open-air settlements in western Europe. In southwestern France, sites along the Isle River contain pavements of stone that apparently reflect the shape of former structures. At Plateau Parrain, the pavement measures 16 × 18 feet in plan and seems to indicate an entrance on the south side. At Le Cerisier, the cobble flooring measures roughly 16 × 16 feet, creating a perfect square with opposing entrances on the east and west sides (figure 4.14).103

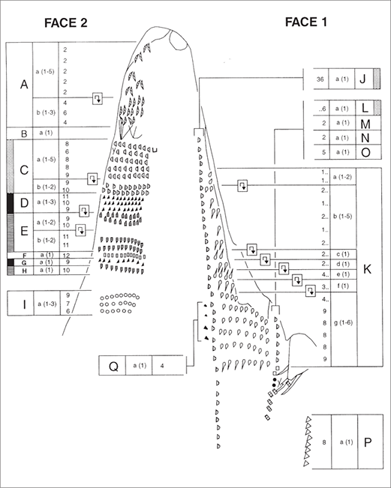

Figure 4.12 Information technology in the form of artificial memory systems (AMS) dates to the earlier phases of the Upper Paleolithic, but became increasingly complex during the later phases. Each face of this antler from La Marche shelter (France) is engraved with a series of marks interpreted by Francesco d’Errico as groups of signs. (From Francesco d’Errico et al., “Archaeological Evidence for the Emergence of Language, Symbolism, and Music—An Alternative Multidisciplinary Perspective,” Journal of World Prehistory 17 [2003]: 34, fig. 8[f]. Reprinted with the permission of Springer Science and Business Media)

Figure 4.13 The foundations of village life: (A) ruins of a mammoth-bone house at Kostenki 11 (Russia) (photo by author); (B) floor plan of Dobranichevka (Ukraine), showing several former mammoth-bone structures (modified from I. G. Shovkoplyas, “Dobranichevskaya Stoyanka na Kievshchine,” Materialy i Issledovaniya po Arkheologii SSSR 185 [1972]: 178, fig. 1).

Figure 4.14 The imposition of geometric form on the landscape is evident in the paved house floor at Le Cerisier (France), a nearly perfect square with entrances to the east and west. (After James R. Sackett, “The Neuvic Group: Upper Paleolithic Open-Air Sites in the Perigord,” in Upper Pleistocene Prehistory of Western Eurasia, ed. Harold L. Dibble and Anna Montet-White [Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Museum, 1988], 69, fig. 3.5. Reproduced with permission from The University Museum, University of Pennsylvania)

The house floors in the Isle River sites illustrate a pattern that becomes increasingly obvious and even somewhat oppressive in the millennia following the end of the Paleolithic—the imposition of geometric forms on the landscape.104 Rectangles, squares, pyramids, and even the true, or Euclidian, circle are unknown in the natural world—biotic or abiotic.105 Evolutionary biology yields symmetrical forms, but not geometric shapes (organisms tend to be lumpy and uneven). Simple geometric shapes are creations of the modern mind. From the late Upper Paleolithic onward, modern humans began to reconstruct the natural landscape in accordance with these mental creations, remaking the world in the form of the mind. So pervasive is the contemporary landscape of this externalized geometry that most of the global population now dwells largely within its own mind.

Geometry is a common theme in later Upper Paleolithic art. Although some of most impressive examples of representational art—both cave paintings and sculptures—date to after 20,000 years ago, abstract designs and geometric forms predominate in places like central and eastern Europe.106 The meanings attached to the visual art of the later Upper Paleolithic remain unknowable, but the change in content and style from the EUP and the Gravettian is undeniable and suggests a shift in worldview. Later Upper Paleolithic people had acquired considerably more knowledge of and greater control over the external world than their predecessors, which surely was reflected in how they interpreted it. Perhaps they felt that they lived in a more orderly and manageable universe than had their ancestors. If so, they were indeed laying the foundation for the post-Paleolithic civilizations that would obsessively reconstruct that universe with numbers.