THE TIERCERON VAULT and bar tracery were inventions with considerable ornamental potential. It is in the 1260s and 1270s that a wide range of motifs, from the carving of foliage to the patterns made by tracery, began to change as designers explored further new decorative effects. The result was a gradual breakdown of the Early English consensus, and the birth of a new and varied style, Decorated. But Decorated is really a century-long process of experiment, and it can be subdivided into two phases, Geometrical and Curvilinear, that are almost separate styles in themselves. Everything in this long period, however, can be understood as a manifestation of a single ‘Decorated Idea’.

The Decorated Idea aims to blur distinctions: between wall and window, building and fitting, architecture and decoration. This is the great age of the customised fitting, with tombs, sedilia and other features treated as one-off pieces of architectural design, works of sculpture that were also fantasy buildings: micro-architecture. Such fittings become elaborate compositions of openwork spirelets and pinnacles, sporting tiny, sculpted niches, buttresses and vaults, sprinkled with energetic crockets and finials. The effect can be as if the building was transmuting into a plant, or as if forms easier to achieve in elaborate metalwork were being rendered in stone. Tiny grotesque beasts abound in the carving: this is the age when gargoyles are at their most prominent, enhancing the spiky silhouette of a building. The finest results are among the most arrestingly complex and beautiful creations of any era. Microarchitecture illustrates the underlying aim of Decorated style: to create buildings that are overwhelming environments, marshalling a wide range of craft techniques – stained glass, tilework, painted decoration – to create a powerful all-encompassing effect. Inventiveness, playfulness and variety are the themes; the architectural clarity of the past is subverted and undermined, clouding one’s sense of the underlying form of the building. Windows are sometimes rendered on flat surfaces in low relief, prefiguring Perpendicular panelling. But Decorated can speak in many voices; its designers can move from the plain to the elaborate, the conventional to the experimental, in a single building, deliberately giving different voices or qualities to different parts; indeed, a surprising number of Decorated parish churches are rather plain, as if in deliberate contrast to the exuberance seen elsewhere.

The sedilia at Dorchester Abbey, Oxfordshire (probably 1330s), feature an explosion of ornamental ideas: small sculpted arches with complex cusping; sculpted buttresses, gables and tracery motifs; glimpses of capriciously shaped windows, each filled with densely coloured stained glass. Crockets, grotesque heads and ballflower motifs add to the rich effect.

The sedilia at Exeter Cathedral (from 1316–17) were designed by the master mason Thomas of Witney, one of the greatest creators of complex micro-architecture.

The Decorated Idea is first fully expressed in such French buildings as the Sainte Chapelle on the Île de la Cité, Paris (c. 1240). Such structures inspired a series of exceptionally ornate late Early English buildings, in particular Westminster Abbey (c. 1245), before the formal details of architectural style began to transform (see page 35), and the first of the two phases of Decorated, which ran from the 1260s to around 1300, truly began. During this Geometrical phase the Decorated Idea transforms architecture in a rather gradual way – as if Early English is gradually loosening its tight canon of stylistic rules. Hence the disagreements over where to place the dividing line between it and Decorated. In the second, Curvilinear phase, a series of innovations stimulate a change of direction and a more self-conscious process of experiment. The roots of this phase lie in a small group of buildings, of which the most influential, the Eleanor Crosses and St Stephen’s Chapel in the Palace of Westminster, were funded by the Crown and begun in the 1290s. Such works would be sources of inspiration for some time, but the two most immediately influential new ideas were a kind of arch, the ogee, and a type of vault rib, the lierne. These motifs and their implications begin to pervade architecture in the 1310s and 20s; the resulting Curvilinear Decorated is then dominant until the mid-fourteenth century and hangs on in some areas, especially along the eastern seaboard and in the north, well into the late fourteenth century.

At its height in the 1320s and 30s, Curvilinear Decorated is the backdrop to a series of highly exploratory experiments – almost an avant-garde. This period of rapid evolution gave birth to the final medieval style, Perpendicular. The greatest of these works, such as the Octagon at Ely and the east ends at the cathedrals of Wells and Bristol, are works of genius which almost defy stylistic categorisation. Such designs appear to have had a substantial influence on European architecture: while the extent of this is much debated, it is agreed that ideas invented in the English West Country at this period can be found as far away as Prague.

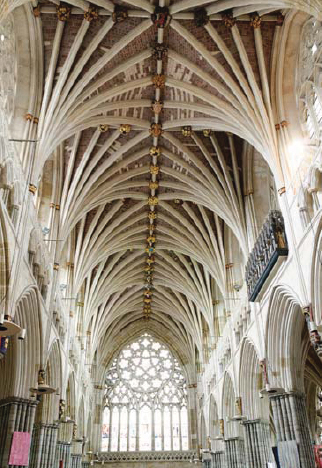

Let us start the story of Decorated with the tierceron vault. In the nave of Lincoln Cathedral, from the 1220s (see page 10), additional ribs were inserted between the cross-ribs that followed the edges of the groins and the ridges of the vault. Each of these tierceron ribs runs from the springing of the vault to its ridge, just like the cross-ribs of a groin vault, but these ribs do not follow the groins. The resulting increase in the number of ribs gave vaults a spreading, organic quality and reduced the viewer’s sense of its underlying structural form. These vaults had their ultimate roots in the one-off ‘crazy vaults of Lincoln’ built in the east end of the same church from 1192 (this was also the place where the ridge rib was invented). Tierceron ribs become widely popular only in the 1260s and 70s, but their luscious effect was explored widely thereafter, with such memorable results as the 96-metre-long run of vaults at Exeter Cathedral (1280s onwards) and the vault that spreads over the octagonal chapter house at Wells Cathedral (after 1286). However, the tierceron vault on its own is not diagnostic as, while its use as the centrepiece of a design decreased significantly during the fourteenth century, it was never forgotten, even as further new types of vault were developed.

The tierceron vaults at Exeter Cathedral, probably designed in the 1280s, feature eleven separate ribs, each curving like a palm-tree from the springing point of the vault to its ridge rib. They grace what is often said to be the longest unbroken run of Gothic vaulting in the world.

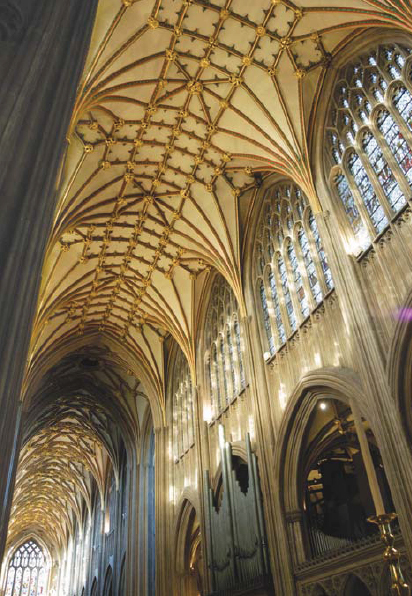

The idea of the tierceron vault had important implications. Ribs no longer had to reflect a vault’s underlying structural form by following its ridges and groins. They could thus be used purely for their decorative effect. The next step was to add further, shorter ribs, in the simple pursuit of pattern for pattern’s sake: liernes. A handful of designers in the 1290s (and perhaps a little before) tried this, and in the early fourteenth century liernes began to spread, increasing in complexity of pattern as they did so. Liernes are distinguishable from tiercerons because they link one rib to another, rather than running from the base to the apex of the vault. They can be used to cover curved ceilings with a potentially infinite variety of stone patterns. Lierne vaults, like tierceron vaults, never died; indeed, they remained the default vault-type through to the Reformation (see page 66), and the presence of a lierne vault alone (their development is a complex study in its own right) can be used diagnostically only to indicate that a building dates to after c. 1300, that is, to identify it as Curvilinear Decorated or Perpendicular in style. They sometimes have cusps added to them, rather like tracery; these are usually large and emphatic in Curvilinear Decorated buildings, when the tendency is to use the liernes to form big, dynamic diamond shapes and net-like patterns.

This pattern of development is comparable to that of arches. In the Geometrical phase of Decorated, the lancet arch becomes much less common, leaving the equilateral arch (and sometimes depressed variants of it) as the default arch-form, as it remains throughout the medieval period. However, the sinuous double-‘S’ curve of the ogee (see pages 52, 82) embodies much about the Decorated Idea: it is counter-intuitive (one can never imagine an ogee arch holding anything up effectively), and more obviously found in plants and metalwork than in buildings of stone; it thus prioritises decorative effect over structural clarity. Like the lierne vault, the ogee appears in the 1290s, though, unlike the lierne, it is by no means an English invention; the earliest examples are found in third/second-century BC India.

The tiercerons and cross-ribs of the vault at St Mary Redcliffe, Bristol, are surrounded, and in some cases interrupted, by shorter lierne ribs, forming cusped patterns of diamonds, triangles and squares. Though the windows are Perpendicular, this fourteenth-century design is characteristic of Decorated lierne vaults.

Ogee arches, lavishly sculpted, on the blank arcades at Beverley Minster, East Yorkshire (c. 1335–40).

In the first decades of the fourteenth century the ogee starts to transform architectural style, as masons explore the ways in which ogival curves can be applied to patterns, especially window tracery, and micro-architecture. In some particularly lavish buildings, of which the Lady Chapel at Ely Cathedral (from 1321) is the most famous, blank ogee arches and ogee-headed niches are draped over entire wall surfaces; many bend outwards into the space, forming nodding ogees. Even today, stripped of its colour, the effect is like inhabiting a metalwork shrine, or standing inside a hothouse filled with various kinds of architectural plant life. Though in the later fourteenth century the ogee arch loses its defining role in architectural style, it is never forgotten, playing a relatively minor but quite common role in Perpendicular designs. On its own it is thus not straightforwardly diagnostic: like the lierne vault, it simply denotes a date after 1300.

The question to ask, then, when faced with ogee curves, is whether they define the composition as a whole: the more a design is imbued with these flickering, organic curves, the more confidently one can ascribe it to the Curvilinear era. Window tracery is perhaps the best place to see this.

In the Geometrical phase, the canonical patterns of early bar tracery (see pages 40–41) breaks down and designers begin to explore a vast range of other patterns. All, at this stage, can simply be generated by playing with a compass, creating intersecting curves, or taking regular shapes such as squares and triangles and giving them curved sides (in particular, spherical triangles). The patterns subvert the clarity of Early English bar tracery, for example by inserting an extra light between sub-arches, or placing two sets of arches of different type – for example, a tall lancet arch enclosing a lower ogee one – at the top of each light. Cusps become extremely elaborate: split cusps (a mouth-like opening with a cusp, most often seen in Kent), and sub-cusps (cusps within cusps, often seen thereafter), etc. One particularly common pattern, intersecting tracery, is diagnostic for Geometrical Decorated and sometimes seen in the second phase of the style, too. The aim in all these cases is to achieve effects of variety and surprise: in some memorable examples, such as Exeter Cathedral, each bay of the church has its own unique tracery designs.

Positioned beneath steep, crocketed gables, these nodding ogees on the outer north porch at St Mary Redcliffe, Bristol (probably c. 1320), give the surface of the structure a swaying, rippling, organic quality; large, brightly painted statues once stood beneath each such arch.

A lavish Geometrical Decorated window at Leominster Priory, Herefordshire, usually dated to the 1320s. The underlying idea of circlets separated by sub-arches is derived from that of early bar tracery, but an extra light separates the sub-arches from each other, and the circlets are filled with complex patterns of cusped stars and triangles. Ballflower covers everything.

Rose window-like designs often fill the main roundel of a window; though pure rose windows – circular windows filled with tracery – are rare in England, and most (but not all) examples are Early English in date (circular windows without tracery, oculi, tend to be small and are usually Anglo-Saxon or Romanesque; or, with simple cusped patterns in them, Decorated).

Late-thirteenth-century Geometrical tracery at Howden Minster, East Yorkshire, after c. 1267–72. Relatively subtle tricks – for example, removing the circlets that enclosed trefoils and quatrefoils, or making the central light slightly larger than the others – add a Decorated twist to bar tracery patterns.

A grand display of Geometrical tracery at Exeter Cathedral. A variant on the intersecting window is seen at bottom right; that at bottom left has sub-arches supporting an enormous spherical triangle. The nave was begun in the 1320s and ogee curves can be seen in some of the clerestory windows.

Curvilinear tracery patterns are unmistakable, and diagnostic. From the 1310s, ogival curves – that is, the ‘S’ shape traced by one side of an ogee arch – begin to appear in windows. Designers used them to make the elements of a pattern flow into one another, resulting in a curvaceous effect that over the ensuing decade or two became the defining feature of tracery in general. One particular motif, the mouchette (and its straighter variant, the dagger), is used again and again, varying in size and precise arrangement. Again, now with a flickering, flowing, organic quality, variety is the aim. Sometimes, Geometrical and Curvilinear windows are seen side by side (or, later, Perpendicular and Curvilinear, though after 1400 Curvilinear patterns are usually only comparatively small elements in Perpendicular windows). One particular Curvilinear pattern is particularly diagnostic: called reticulated, it fills the entire window-head with a single, symmetrical, repeated motif, in effect a honeycomb based on ogees rather than hexagons.

Decorated foliage, too, falls into two phases of development. In the 1260s and 70s stiff leaf gradually turns into something equally stylised, and equally divorced from anything seen in nature, but rather knobbly in quality, and often called crinkly or ‘seaweed’ foliage. The stalks or branches that support it are often less prominent than before: sometimes entire surfaces are covered with rippling expanses of it. By c. 1300 this kind of foliage had become universal, changing only subtly – mainly in how it is arranged – in the Perpendicular period (see pages 57 and 72). These carvings continue to have the potential to be inhabited by beasts, green men and other grotesques, for which the Decorated era was a golden age. At the same time there is also a brief flowering of naturalistic foliage, in which individual species of plant, such as oak, maple and hawthorn, can be identified: indeed, this, along with the tracery patterns of the era, is the one motif that can truly be called diagnostic for Geometrical Decorated. At its very best, naturalistic foliage has clearly been carved directly from life: the chapter house at Southwell Minster (1288) contains the most famous examples. Both these types of foliage are widely used everywhere, for example on crockets, which are ubiquitous from now on.

A Curvilinear window at Ducklington, Oxfordshire, probably c. 1320–40: ogee curves give a flowing quality to its tracery. Sub-arches divide the window into two halves. The areas of solid masonry in the uppermost motif carry sculpted statuary inside the building, a typically Decorated conceit.

swooping mouchettes and daggers in a Curvilinear window of c. 1333 at Heckington, Lincolnshire.

Reticulated tracery at Earls Barton, Northamptonshire. This pattern, usually dated to the 1330s and 40s, can be seen in a great many windows of the Curvilinear period, though rarely with the window-arch itself being ogee-shaped, as here.

This Curvilinear two-light window at North Elmham, Norfolk, follows the pattern set by its Early English predecessors (see pages 40–41), but replaces the foiled circle with a single reticulation, rising from ogee-topped lights.

Two sprigs of crinkly foliage on a fourteenth-century capital at Beverley Minster.

Lavish microarchitecture on the Easter sepulchre at Heckington. A fictive gable sprouts crockets and a finial of crinkly foliage, more of which spreads across the surface above.

In the Decorated era the capitals on which foliage is carved tend to shrink in size, and in the early fourteenth century begin often to be restricted to the shaft-like part of a column’s moulding, allowing a continuous moulding to rise through to the arch above in Curvilinear Decorated and later, Perpendicular buildings. Sometimes the capital is a wide band at the top of the column; at others, there are simply no capitals at all, and the moulding swoops from the base of the column to the apex of the arch.

The bell capitals and emphatic shafts of this Geometrical Decorated pier at Exeter Cathedral are not dissimilar to those of the Early English style. But by bunching these features together, and subtly flattening the mouldings above, the designer has emphasised richness of effect and surface texture over clarity and linearity.

Such continuous mouldings existed in the West Country in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, but are not seen elsewhere. They break the principle, previously fundamental, that capitals should emphatically divide a column from an arch. They thus embody some of the defining ideas behind Decorated mouldings. Geometrical mouldings are chiefly slightly flattened versions of their Early English predecessors, but from around 1300 mouldings tend to flatten and simplify, gaining a smooth quality rather akin to their Perpendicular successors. An ogivally curving surface known as a wave moulding, very different from the complex forms of Early English and many Geometrical Decorated mouldings, is frequently used. The tendency to create separate en-delit shafts declined throughout the Geometrical Decorated period, too, and again after around 1300 almost disappears. Columns now read more as bundles of interconnected motifs than as arrangements of separate shafts. Though the shafting still roughly lines up with steps in the moulding above, its visual significance has been greatly reduced: the effect is to replace linear clarity with smooth dynamism.

Small capitals clasp the diminutive shafts, while a great swoop of wave moulding runs continuously up the pier and into the arch. This pioneering design at Bristol Cathedral, possibly dated as early as 1298, also features unique vaults supported on bridges pierced by enormous mouchettes.

In the fourteenth century mouldings tend to get simpler and smoother, and ogee curves are introduced through the use of wave mouldings.

Exeter Cathedral, rebuilt between the 1270s and the mid-fourteenth century, is a touchstone of Decorated design. Note the small triforium, which could never be confused with a gallery.

Ballflower, a circular fruit-like motif with a three-lobed mouth that contains a smaller seed or fruit, at Bampton, Oxfordshire; probably early fourteenth century.

In both phases of Decorated, variety is the watchword in other ornamental motifs. Nailhead and dogtooth, like stiff leaf and the repetitive patterns of early bar tracery, disappear rapidly in the 1260s–70s, and among a range of replacement motifs, most of them floral, is one that is highly diagnostic: ballflower, a ball-shaped fruit with a three-lobed mouth. This is seen occasionally in the 1280s–90s and becomes very widespread in the Curvilinear phase. It is repeated along mouldings and outside arches of all kinds, much as chevron and nailhead had been in previous stylistic phases; sometimes the ballflowers are joined by a curving foliate tendril; sometimes, especially in the Marches and west Midlands, they are simply dotted over entire surfaces, making some buildings appear as if they have caught a kind of architectural rash. Its obfuscatory, organic quality must have been profoundly ill-suited to the next style, and ballflower disappears rapidly from the mid-fourteenth century. In general the age in which it was created, the Decorated period, might have been in the mind of John Lydgate when he fantasised, in 1412–20, about architecture: ‘So fresh, so rich, and so delightable, as it alone was incomparable.’

Tudor arches (in the three main blank arches) and pendant vaults at the Divinity School, Oxford (c.1423–83), a building that helped inspire a rebirth of architecture in the decades before the Reformation.