SUPERFICIALLY, Perpendicular sits in marked contrast to Decorated. In effect, the sinuous ogival curve is replaced by the sobriety of the straight line; variety and inventiveness are replaced by repetition and a canonical set of stylistic rules almost as tight as those of Early English. Yet there are important continuities between the two.

A number of motifs seen in Perpendicular – the ogee arch, the lierne vault, the wave moulding and crinkly foliage have been mentioned, and there are also straight-topped windows and polygonal capitals (see pages 71 and 72) – were Decorated inventions. What Perpendicular does is to replace the capricious variety of Decorated design with a single, defining motif, applied with an unerring visual logic; everything from arch forms to capitals are adjusted to reflect its implications. As a result various once-popular motifs, such as ballflower, disappear, while the significance of others, such as the ogee arch, decreases markedly.

This motif, the panel (see page 65), brings visual unity to everything from the smallest fitting to the grandest church façade. It thus fulfils much that Decorated designers had striven for, while also reducing the number of one-off customised elements in a design. (Decorated at its height must have been very expensive to produce.) When seen from this point of view, Perpendicular is not so much a rejection of the licence of the Decorated era, an architecture going straight: it is a fulfilment of some of its most deeply desired aims, as if something restlessly searched for had finally been found.

Nevertheless, the lack of variety that results gives many Perpendicular buildings a sober, masculine, repetitive quality very unlike that of Decorated at its most exuberant: as it was put in 1540 of the parish churches of Nottingham, the style is ‘excellent, new and uniform in work … [with] many fair windows’.

A grid of panels, rectilinear motifs derived from tracery, covers the tower at Cirencester, Gloucestershire (after c. 1400). If it were not for its arched head, the belfry window would simply be a continuation of the surface pattern that runs either side of it.

Its dependence on a single motif is only one of Perpendicular’s unique characteristics. The style is long-lasting, which is another way of saying it is rather conservative: it is hard to distinguish a building of 1380 from one of 1480. Perpendicular is also uniquely English: for example, in Scotland and Ireland styles very close to contemporary French architecture (and to Curvilinear Decorated) predominated into the sixteenth century (see pages 11 and 13).

While a range of contextual factors may explain such qualities, including the traumas caused by the Black Death of 1348 and the relative isolation from French influence that was a result of the Hundred Years’ War, it is true that European architecture in general fragmented into a series of distinct national styles during the fifteenth century. Historians generally think of the era from the mid-fourteenth to the sixteenth century as ‘late medieval’ and the Perpendicular style aligns perfectly with this important phase of social, political and cultural change: it is particularly relevant to church architecture that this saw the development of a deep, widespread and distinctive popular religious culture (see page 73), while a smaller group of people – the Lollards – for the first time publicly questioned some of the tenets of the traditional faith.

A panel in the nave at Winchester Cathedral (1370s–1394 to c. 1400), rising from the curved side of the arch beneath.

Perpendicular seems to have been consciously invented. This is a complex and fascinating story with its roots in the Decorated experiments associated with the royal court in the 1290s. For example, from this date there are occasional experiments with inserting short straight lines into the curves of window tracery patterns, and very occasional uses of new arch forms in addition to the ogee – in particular, the four-centred arch. In addition to this, in one single (and lost) building, St Stephen’s Chapel in the Palace of Westminster (1292), the window mullions are extended down the wall beneath each window, running blank over the wall surface, and then, like strings across an opening, continuing over the front of a lower set of windows.

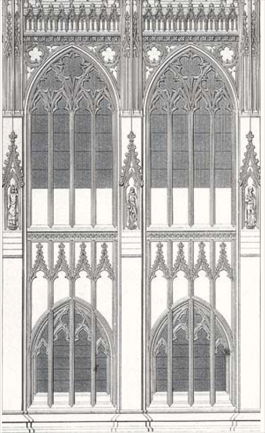

St Stephen’s Chapel in the Palace of Westminster: an influential building, designed in 1292. Note the continuation of the mullions of the upper windows over the walls and windows beneath.

Such innovations were ultimately inspired by contemporary French practice; they vividly embody the Decorated delight in delicious contrasts and the occlusion of structural clarity. But they were not as immediately influential as those other innovations of the 1290s, the ogee arch and the lierne vault. It is ironic that, in the longer term, they would result in an English architecture that was less interested in French precedent than any before, and the development of a style that moved away from obfuscation and variety and towards clarity and unity.

It is with the great experiments of the 1320s and 30s (see page 49) that these ideas are more fully explored. In particular, in two buildings of the same year, 1331–2, they come together to create an architecture in which straight lines are the watchword, extending over wall surfaces and transforming tracery patterns. These are the chapter house of Old St Paul’s and the south transept (and, following on from it, the choir and north transept) at Gloucester Cathedral.

In both these buildings the straight line has been applied to window tracery to an extent previously unknown: it now becomes the defining idea of the pattern itself. For example, reticulations, which most other designers were forming from ogival curves, here become near-hexagons – Perpendicular reticulations. Transoms, hardly known in church windows before around 1300 (they are common in castles), become very emphatic, dividing the lower part of a window from the top, and giving it a grid-like aspect. Each light of the window beneath the transom is topped by a cusped arch, resulting in a row of rectilinear, arch-topped lights. A further row of these lights, each again topped by a cusped arch, is then carved on to the surface of the wall beneath, almost as if it were a blocked window – as if the base of the window above was merely another transom. These motifs are panels; they turn the elevation into an extension of the window lights and unite the entire composition around their grid-like repetition. Other details, from arch forms to vaults, are flattened, emphasising rectilinearity wherever possible.

At Gloucester Cathedral (the choir, which refines the ideas used in the south transept of c. 1331–6, is shown here) the idea of continuing the window tracery over walls and surfaces is explored to spectacular effect. The grid-like effect that results is further emphasised by the straightening of the lines used in the window tracery and the emphatic transoms running across the window.

To many at the time, these buildings might have seemed little more than further contributions to a series of one-off experiments. Yet the extent to which they reinvent the formal details of architecture, and the consistency of effect that results, had all the hallmarks of a new style. These were ideas that could be replicated and used in a wide variety of contexts.

The façade of the porch at Cirencester (c.1490–1500) is a handsome display of panelling.

At first the responses to this constitute an ‘early Perpendicular’, for example by adopting aspects of the new forms in otherwise conventionally Decorated settings. But in the 1350s and 60s, the architecture of Gloucester and Old St Paul’s starts to be copied and finessed, and by the 1370s it has spread across southern England. Spectacular new naves at Winchester and Canterbury cathedrals cemented its success. By the 1380s Perpendicular is common in eastern and northern areas, too, though Curvilinear motifs long existed side by side with it in a manner rarely seen in the style’s southern and south-western homeland. Well before 1400, it has simply become the only way to build, and would remain so for well over a century. In the later fifteenth century, however, the style develops a marked late phase, sometimes called Tudor, that can often be recognised, especially in vaults and arches (see page 61) and signs of Renaissance influence (page 77). The greatest of these buildings displayed a creativity and ornamental verve not seen since the 1330s.

The panel, as will already be clear, is the unmistakable diagnostic motif that lies at the heart of the Perpendicular style. Its origin lies in the shape of an individual window light. It is simply a shallow rectangle with a cusped arch in its head. Its rectilinear outline means it can be repeated to form a grid, which can be carved over any kind of surface, extending across windows and walls alike.

The motif is superficially like a niche, or even some of the pilaster strip patterns seen in Anglo-Saxon architecture, but can be straightforwardly distinguished from both. To function, a niche needs to be deep enough to hold a statue, whereas the panel itself is almost flat. Standing figures can be, and often were, painted in panels, but, to put a statue in one, a bracket or a canopy needs to be added to it. Anglo-Saxon pilaster strips are merely plank-like strips of stone, whereas panels, being derived from window mullions, have simple but delicate mouldings, and the cusped arches in their heads are unknown in Anglo-Saxon architecture. Also, and again unlike pilaster strips, panels are not structurally separate from the surface into which they have been carved. Bearing in mind this single motif and its grid-like implications, we can explore the various other aspects of the Perpendicular style.

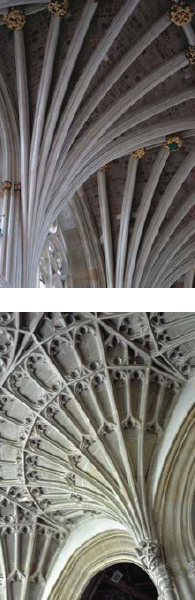

The vault in the nave at Winchester Cathedral (1370s–1394 to c. 1400) uses liernes to insert panel-like patterns between the tiercerons.

Lierne vaults are the commonest Perpendicular vault type. Designers often used them to evoke the idea of the panel, for example by using them to make extended, cusped shapes in their vaults, a form derived from window lights. However, the masons working on the cloisters at Gloucester (and perhaps a couple of other places) in the 1350s or 60s found a way of applying panels to vaults in a far more radical manner, known as a fan vault.

These vaults were constructed in a fundamentally new way. Instead of being made out of two separate elements – the groined infilling and the ribs – they are constructed as a single, curved skin built up in slabs so that it grows from the springing of the vault, very much like the cone of a trumpet. The result was a series of curved conoids, with small flat areas of ceiling where the conoids meet, structurally more akin to a dome or an igloo than a rib vault. The smooth surfaces of these conoids are carved with a series of panels, forming a pattern that spreads evenly out from the base; tracery patterns or perhaps a boss fill the flat areas between the conoids. Drawn as a plan, the carved panels are clearly derived from tracery patterns; indeed, they can be almost identical to those of earlier Gothic rose windows.

The true fan vault has no ribs or groins at all. Instead, panels are carved onto curving skins of stone. The geometrically ordered, almost mathematical quality that results is unmistakable, as seen here in the Lane Aisle (1526) at Cullompton, Devon.

Fan vaults have an unerring smoothness, a kind of geometricality, that is both beautiful and distinctive. Unlike tierceron or lierne vaults, with which they are most often confused, there are no groins and no structural distinctions between rib and infilling, merely a single, smooth, curved surface bearing a carved pattern of panels. This effect is unmistakable, so much so that even when the same effect is contrived in a vault that is visually identical to true fan vaults but does have separate ribs and infillings (as can be seen at Christ Church Cathedral, Oxford, and Sherborne Abbey, Dorset), such vaults are usually called fan vaults, too.

The difference between tierceron (upper, at Exeter Cathedral) and fan (lower, at Cullompton) vaults is clear when they are seen side by side.

The fan vault is diagnostic for Perpendicular. It is also restricted to relatively intimate locations – aisles, cloisters, chantry chapels – and to south west England until the mid-fifteenth century. Indeed, true fan vaults (Sherborne is earlier but is not structurally a fan vault) were not placed over the main spaces of churches until around 1500, at King’s College Chapel, Cambridge, for example, and such fan vaults help mark out late or Tudor Perpendicular from the rest of the style. At Christ Church, Oxford, and at Henry VII’s Chapel, Westminster Abbey, the fans have become freestanding stalactite-like features, hanging down from the ceiling, and carved into pendants: though few such vaults in their pure form exist, roofs of other kinds, including timber ones, can have prominent pendants and are again diagnostic for Perpendicular in its late phase.

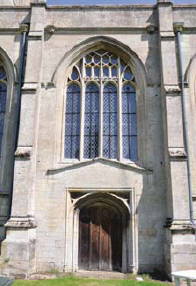

The designers of arches strove to translate the new thinking to ways of covering openings. The emphasis is now on ways in which the curved outline of an arch can be given a rectilinear aspect. The most diagnostic of these is the flattened, shouldered profile of the four-centred arch. This is so called because it is drawn by putting one’s compass down four times (see page 82): parts of the arcs of two separate small circles give the arch its pronounced shoulders; then two much larger intersecting circles, struck from a much lower point, are used to bridge the gap between them. These arcs sometimes barely appear to be curved at all. This type of arch is seen very occasionally in the experiments of the 1290s to the 1330s, but it then takes over: very few Perpendicular buildings do not have some. A logical extension of this is for the shoulders to be made of extremely small circles, and the rest of the arch to be composed simply of straight lines, a motif called the Tudor arch, diagnostic for Perpendicular and particularly common from the later fifteenth century and into the sixteenth. It is quite different from the triangular arches of the Anglo-Saxon era, which are steep triangles, made of unmoulded stone, and contain no curves of any kind. Depressed arches are common in Perpendicular buildings, and much broader and flatter in profile than before, while a new and diagnostic variant, the three-centred arch, appears: both these developments again serve to de-emphasise the arch’s curvature. Finally, arches of all kinds, whether they be ogee, four-centred or of another form, and especially those over doors and tombs, are very often placed in rectilinear frames, formed of drip-moulds (the moulded lip that often runs round the outside of a window arch, previously a rather utilitarian feature). These had usually followed the curve of the arched window or door itself; now they become prominent, square, moulded frames, making the opening as a whole akin to the top of a large panel. Again, the motif emphasises the rectilinear and is highly diagnostic.

Four-centred arch in a square frame over a door at Tattershall, Lincolnshire (from 1469). The mullions of the window above rise continuously up to the window-arch.

Two motifs, one really only a widened version of the other, are the key to understanding Perpendicular window tracery. The largest of these, the Perpendicular reticulation, is rarely a true hexagon: though it has straight sides, its top and bottom are usually slightly curved. It is used to generate a limited range of diagnostic patterns that must exist in their thousands in churches large and small across the country.

Very commonly, one sees three-light windows with two reticulations in the window-head. Four-light windows might still be divided into pairs by sub-arches, but now have a Perpendicular reticulation above each pair of lights. The straight sides of these reticulations run upwards through the sub-arches and become the sides of a further reticulation in the window-head, before striking the arch of the window-head itself, as if the foiled circles in the bar tracery of the 1240s had been drawn with a ruler rather than a compass (see pages 41, 70). Indeed, the presence of a straight line in a window that runs throughout the tracery pattern (whatever the pattern itself is), from the top of a window light to the arch of the window-head itself, is also, wherever it occurs, diagnostic.

In these patterns each reticulation may be filled with a pair of small, glazed panel-like motifs. While the three-light and four-light variants described above (with or without paired, panel-like subdivisions of their reticulation units) are seen everywhere, these smaller units can also be used to generate tracery patterns in their own right: they play a key role in the larger and more varied Perpendicular tracery patterns. The most elaborate of these can have a lace-like quality. Spectacular east windows at Gloucester and York Minster, both comparatively early in the style, are often claimed to be among the largest medieval windows in Europe; Perpendicular churches in general can be large, airy cages of glass, their aisles lit by repeated tracery patterns.

There are some very simple forms of Perpendicular window. One is the style’s updating of the triple-light window (see page 38), most easily distinguishable from its Decorated predecessor by its use of four-centred, depressed or three-centred arches. Even simpler, and very illustrative of the Perpendicular mindset, are flat-topped windows. These usually comprise simply a row of panel-shaped lights, sometimes with paired panel-like motifs above each light. Such windows become increasingly commonplace in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. They are almost diagnostic, but, if the top of the light is a lancet arch or has a Curvilinear reticulation above it, it is probably Decorated; and, if the top of the light is an equilateral or ogee arch, one should check for other clues. Nevertheless, Perpendicular flat-topped windows with emphatic drip-moulds, their tracery a simple row of glazed panels with four-centred or, later, semicircular tops, are ubiquitous in churches and domestic buildings alike.

The three-light window on the right, at Avebury, Wiltshire, features what is probably the commonest Perpendicular tracery pattern of all: a pair of Perpendicular reticulations, each filled with two small panel-like motifs. The porch on the left is also Perpendicular, a four-centred arch topped by an emphatic drip-mould that ends in big, square label stops.

The windows to the left and right here feature a typical pattern for four-light Perpendicular windows, in which the straight sides of the reticulations cross the sub-arches, stopping at the window-arch. The walls here, at St Mary Magdalene, Launceston, Cornwall (1511–24), are covered with a riot of panelling, carved from intractable granite.

An emphatic drip-mould and a Tudor arch at Elkstone, Gloucestershire; fifteenth or sixteenth century.

Two-light windows are given a Perpendicular character by straightening the sides of the reticulation and placing within it a pair of small panel-like features. Elkstone; probably fifteenth century.

A grand Perpendicular west window in the tower at Blakeney, Norfolk. Creativity in Perpendicular window design is usually focused on windows in the western and eastern walls of a church.

Perpendicular foliage remains knobbly in character, if often rather stiff, like dried seaweed; very often it is clear the plant depicted is a stylised grapevine. It is the way this foliage is arranged that sets it apart most clearly from that of the Curvilinear Decorated era. It often runs in thin horizontal rows, which can be seen ranged one above the other; often, too, an ‘S’-shaped tendril or branch links the leaves or fruits either side of its curves, or the leaves spiral around a central branch. The arrangement of foliage into such bands is seen in countless buildings, and is equally ubiquitous in timber roofs, screens and other furnishings; it is diagnostic for Perpendicular.

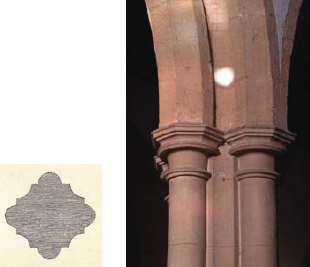

Capitals also show continuity with their late Decorated predecessors. Look out for capitals in which these horizontal foliage bands feature, or in which some or all of the moulding is polygonal rather than curved in plan: straight lines again. The latter are a Decorated invention, so one has to look for other motifs to be certain of their date. In general, Perpendicular mouldings tend towards smoothness, in a manner rather similar to their Curvilinear Decorated predecessors, and continuous and wave mouldings continue to be used. A couple of specific mouldings for columns, ultimately descended from compound piers, are diagnostic, and seen in countless buildings. Perpendicular columns also have exceptionally high bases, making them more straightforwardly diagnostic than the bases of preceding styles.

These Perpendicular flat-topped windows at Ogbourne St George, Wiltshire, simply comprise a row of tracery lights, like a row of glazed panels. The four-light lower window also has an emphatic hood-mould.

Dry-looking crinkly foliage, arranged in piled-up horizontal rows, on the rood screen at Cullompton, Devon.

More Perpendicular fittings survive than those of any other style: medieval timber roofs (such as the famous hammerbeam roofs, diagnostic, and popular in eastern England), doors, screens, pulpits, pews, sets of choir stalls or, more rarely, stone reredoses can be found (the only fittings earlier than this to survive in any number are tombs, fonts, Easter sepulchres, piscinas and sedilia). The scale of this survival is partly a reflection of the fact that this is both the most recent and the most long-lived of styles, but is also a vivid illustration of the nature of late medieval piety. At this time ordinary people invested large amounts of their disposable income in religious activities, creating a rich popular religious culture, intensely focused on preparation for death and on prayers for the souls of the dead, who were believed to be held in Purgatory. Huge numbers of parish churches were rebuilt or modernised by pious donors, and new fittings proliferated.

One type of fitting, invented in the 1360s, is a testament to this, and by definition Perpendicular: this is the cage chantry, at its simplest merely a panelled rectilinear enclosure of timber or stone inserted into an existing building, though the most elaborate are almost small churches in their own right. A chantry need not be held in a purpose-built chapel: it is simply a type of mass, one focused on the soul of a particular named individual or individuals. All that is needed is time at an altar for certain periods of the day. Structures of various kinds had for some time been created as venues for these masses, usually accompanied by a tomb. Now this specific invention, a rectilinear panelled cage or screen inserted into a church, and containing an altar and a tomb, became the venue for the more lavishly endowed of these masses. The cage chantry is a reminder of the intense importance of commemorative prayer in this era, and an illuminating example of the Perpendicular aesthetic. Both a fitting and architecture, cage chantries are among the most richly creative designs of the late medieval period.

The design of this column at Arundel, West Sussex (1380), follows a moulding pattern that was used in many churches over some two hundred years (see top left): four attached shafts are separated by scoops; only the shafts have capitals (here they almost touch), leaving the scoop as a continuous moulding. Here, each bell capital has a polygonal abacus.

Late medieval religious culture also had a specific impact on Perpendicular art and imagery, resulting in the development of incidental sculpted motifs that do not occur at any other period and are thus diagnostic. Shields bearing chivalrous coats of arms, for example, had been carved on walls and tombs or depicted in stained glass windows in churches since the mid-thirteenth century, but now they proliferated, and developed a range of distinctive features. Perpendicular shields are often held by a sculpted angel. They may bear the Arma Christi, emblematic depictions of the wounds of Christ or the implements used to inflict them. They may also bear an inscription, a merchant’s mark (in effect a logo) or a rebus, a punning representation of the name of the person who is being commemorated. Such features may be used in other decorative contexts, such as on roofs, where choirs of angels often bear them. Some tombs are grisly cadaver effigies, depicting the individual after death rather than before. All these motifs are designed to encourage pious reactions: prayers for the soul of a dead individual, empathy for the suffering of Christ, meditations on mortality.

All such fittings take on the language of the style, though some aspects of their micro-architecture, especially the canopies placed over niches or stalls, can be almost indistinguishable from those of the Decorated era. Canopies that have been placed in a panel or a squared frame, or given emphatically flattened tops, are Perpendicular: everywhere, the panel can be applied with equal felicity to an entire building or to a small fitting such as a font or pew.

This fifteenth-or sixteenth-century capital at Cullompton features a horizontal line of crinkly foliage, which runs in a spiral around a knobbly branch. The pier beneath has a type of wave moulding between its attached shafts.

A typically high Perpendicular column base with polygonal mouldings at Cirencester. It may have been designed to be visible above timber pews, which became popular for the first time in the late medieval era. Before this, church naves were largely free of fittings, apart from a font and side-altars; sometimes a stone bench ran around the walls.

A Perpendicular shield-holding angel set against a horizontal string-course made of spirals of crinkly foliage, at St Mary, Oxford (c. 1485–95). The angel, carved with a handsome fullness typical of the fifteenth century, may have displayed the arms of a sponsoring family or institution, or religious emblems such as the Arma Christi.

These owls at Exeter Cathedral stud the walls of the chantry chapel of Bishop Oldham (died 1519). The design of his rebus suggests that the bishop’s name was pronounced ‘Owl-dam’, as it still is in his native Lancashire.

Perpendicular has very pronounced regional characteristics, especially visible in the austere granite churches of Cornwall and west Devon; in the bell towers of Somerset, the belfry windows of which become the centrepieces of enormous panel-like compositions, while their pinnacles and battlements dissolve into lacy crowns of pierced stonework; and in the flushwork popular in East Anglia, in which panels, tracery patterns, inscriptions and other motifs cut from honey-white limestone are filled with the grey-blue glow of knapped flints. Another source of rich-looking textures was alabaster, a kind of gypsum, used for altarpieces (and, more rarely, effigies). These were produced in huge quantities by workshops in Nottinghamshire.

These niches at Burford, Oxfordshire (c. 1450), are capped by tall canopies that, taken in isolation, would be indistinguishable from those of the Decorated style. It is their setting in the midst of a tight pattern of rectilinear panelling that places them in the Perpendicular era.

Finally, one might also argue that the style sees some attempts to play with the defining features that, for three hundred years, had gone to set great churches apart: such buildings as St George’s Chapel, Windsor, and King’s College Chapel, Cambridge, can be read as attempts to create distinctive variants on the great church specific to the collegiate communities that were developed on a previously unmatched scale at this period. In greater and lesser churches alike, panelling often fills the space between the clerestory and the arcade, in great churches reducing the triforium to a bare minimum, and in lesser ones bringing a level of complexity to parish-church elevations that had previously been unknown. The clear distinction between greater- and lesser-church elevations was thus reduced, though it by no means disappeared.

This niche, in the chapter house at Exeter Cathedral (after 1413) has a typically Perpendicular flat-topped profile.

The simple granite vernacular of Cornish/west Devon Perpendicular at Zennor, Cornwall.

Panelling rendered in flushwork at Lavenham, Suffolk (1525).

We have already mentioned a few features, such as Tudor arches, massive fan vaults and pendants (see pages 60 and 68) that are particularly associated with the last phase of Perpendicular. Though many of these features can be seen as early as the 1430s, it is at the end of the period that they become popular and architecture rediscovers something of the inventiveness and ornamental verve seen in the Decorated era. These late motifs are joined in the first decades of the sixteenth century by an infusion of motifs from Continental Europe, seen almost exclusively in timber fittings, some perhaps produced by itinerant foreign carpenters. Flamboyant, flickering tracery forms appear, hard to distinguish from (much rarer) Curvilinear-era timber fittings, but often accompanied by carved motifs of Renaissance origin, by now circulating in printed engravings: putti, little cherubs quite unlike hieratic Gothic angels; curving arrangements of vine and acanthus leaves. It may also be Renaissance influence that leads, for the first time in three hundred years, to a slight return for semicircular arches. Usually these curves have a depressed form rather than being pure semicircles, in window tracery and architecture alike; they rarely play a dominant role in a composition.

The elevation of the nave at Lavenham: panel-like blank tracery patterns are used to create a composition whose refinement and complexity would, at any other period, be exceptional in parish-church architecture.

All this becomes increasingly common in the 1520s and 30s, reminding us that Gothic church architecture would have continued to evolve had the complex processes of Reformation, starting with the Dissolution of the Monasteries in 1536 and 1539, but taking a series of twists and turns over many decades, not transformed the whole pattern of building in general. This era, of course, saw the separation of the Protestant and Catholic churches, the destruction of medieval shrines, the reduction of many monasteries to ruins, and, from 1547, systematic iconoclasm.

Renaissance putti and other Classical motifs cavort along the edge of a late Perpendicular tomb recess at Exeter Cathedral.

The story thereafter is a fascinating one, but can only be sketched out here in the briefest form. The weight of architectural investment and invention shifts rapidly following the Dissolution from churches to country houses; for example, no new great church was built in England until St Paul’s Cathedral was rebuilt in the 1660s. Before this, the details used in Elizabethan and Jacobean church fittings have a distinctive, Renaissance-influenced flavour, though church architecture itself, where it exists, is often a simple version of late Perpendicular practice, perhaps with a few Classical details thrown in. Fittings changed, reflecting new thinking about the faith itself. For many, the altar was no longer seen as sacramental: it was merely a table. A new emphasis on the sermon resulted in prominent pulpits. It is not until the late seventeenth century that a pure and fully understood Renaissance style first becomes the norm in English architecture; to recognise this, one has to be familiar with the many diagnostic elements of Classical architecture, including its rules of proportion and composition, and the capitals and other diagnostic details used in the Doric, Tuscan, Ionic, Composite and Corinthian orders. From now on church buildings are more frequently seen, successively Baroque and Neo-Classical in style, depending on period; increasingly in the eighteenth century, some loosely evoke medieval designs: this ‘Gothick’ is easy to distinguish from the real thing, but it is worth remembering that it is at this period that people first began to take an interest in an architectural form that had long been derided for its association with Catholicism. The term ‘Gothic’ is a post-medieval coining, associating the style with the ‘barbarian’ despoilers of Classical Rome.

The lavish late Perpendicular completion of King’s College Chapel, Cambridge, from 1508 has a swaggering richness, its panelling studded with Tudor heraldic motifs.

Then, from the early nineteenth century, and running right into the twentieth century, serious archaeological interest in medieval architecture flowers, alongside a movement known as Historicism, in which older styles of architecture are revived. The Gothic Revival was a major development within this: here, medieval architectural styles were applied to everything from railway stations to the new churches of the industrial towns and suburbs. At the same time the widespread ‘restoration’ of ancient churches to their ‘pure’ medieval form has created a challenge for modern architectural historians. Indeed, it should be emphasised that almost all statues, wall paintings, stained glass windows, monuments, pulpits and pews, and most roofs and screens, in churches today are Victorian or later.

Some Gothic Revival work is easy to recognise because it mixes up motifs of different medieval eras or borrows them accurately but unhistorically from outside England – chiefly from Italy or France. But in other places restoration is nearly impossible to tell from original work: without a pre-restoration illustration, a given motif may look suspiciously ‘clean’ or machine-cut in its detailing, but determining whether it is an accurately recut medieval original, an inaccurately but convincingly recut medieval original or a complete invention may not be straightforward. Better clues come in any associated sculpted imagery and stained glass: if statues have heads, and windows are not comprised of a mosaic of black lines caused by centuries of fixing and re-fixing, they are probably Victorian. In all these cases, the Victorians rarely depicted figures, especially faces, in quite the stylised, hieratic way that was the norm in the medieval period: a kind of realism in modelling and features, under the influence both of the Renaissance and of photography, is diagnostic once the eye has learnt to identify it. Today, it is impossible to get permission to make changes to the fabric of churches that are indistinguishable from older work, though they must be in sympathy with it.

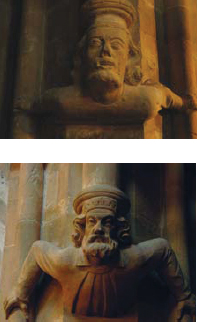

The realism and fine finish of the nineteenth-century re-carving (above) separates it from a more stylised and worn thirteenth-century original (below) at Cirencester.