Beaches are a treasure—cherished by most, exploited by some, enjoyed by all. Beaches are places for recreation, contemplation, renewal and rejuvenation, communing with nature, and sometimes, while staring out to sea, thinking about our place in the universe. On beaches we swim, surf, fish, jog, stroll, or just lose ourselves in the wonder of where the land meets the sea. Yet for all of our interaction with beaches, few of us understand them: why they are there, how they work, why they show so much variety in form and composition, and why they can undergo dramatic changes in a matter of hours.

Humans have been crossing beaches since the dawn of time, and beaches have been critical to human history and development, as they still are. Unfortunately, much of the history of beaches has to do with invasions, but discovery was also part of the human tide that traversed beaches through history. Julius Caesar landed on Deal Beach near Dover when he invaded Britain in 55 B.C., fifteen hundred or so years before Columbus landed in the New World. In A.D. 1001, Leif Ericksson was the first European to set foot on a beach in Vinland (Newfoundland). King Canute sat on his throne on a beach in 1020 and ordered the tides to come no closer, an early object lesson to demonstrate to his subjects that no man, not even the king, has authority over the sea. The Normans crossed the beach at Hastings, England, in 1066 to defeat the English. The Mongols crossed the beach at today’s Fukuoka, Japan, in 1281 to be defeated by the divine wind, a typhoon that destroyed the invasion fleet. The Spanish Armada of 1588 met a similar fate in their attempt to invade England when a great storm blew the surviving ships onto the rocky coasts of the British Isles. Many of the survivors and much debris and treasure washed up on Ireland’s beaches. Columbus planted the Spanish flag and a cross in 1492 on the beach at San Salvador in the New World, to the amazement of the natives. In 1519, Hernán Cortés and six hundred of his men crossed the beaches of the Yucatán Peninsula on his way to conquering the Aztec Empire. Australians first met Aborigines on a beach in 1606. In 1619, a Dutch vessel landed twenty slaves on a beach in Chesapeake Bay, marking the beginning of African slavery in America. In 1620, the Pilgrims disembarked in the New World next to a large rock on the beach now known as Plymouth Rock. In 1659, Robinson Crusoe is said to have crawled across the beach on an uninhabited island off the Orinoco River, in northern South America, where he remained for twenty-eight years. The great explorer Captain Cook met natives on the beach in Hawaii (the Sandwich Islands), where they killed him in 1779. And Darwin met naked Patagonians on a cold beach in Tierra del Fuego in 1833.

A beautiful cliffed shoreline of volcanic rocks in the Aleutian Islands, Alaska. Two small pocket beaches are visible at the base of the cliff. The material of these beaches ranges from sand size to boulders.

In 1915, nearly 330,000 total casualties occurred on or very near the beaches of Gallipoli, Turkey, as the Turks beat back the invading Allied forces. Will Rogers died when his plane crashed on takeoff from a beach near Barrow, Alaska, in 1935. And the beach at Dunkirk, France, in 1940 was the scene of the spectacular rescue of the defeated British Expeditionary Force in World War II. In 1944, the direction of the armies reversed as the Allies invaded Europe across the beaches of Anzio, Italy, and then Normandy, France. In the same time interval, beaches across the Pacific were killing fields as the Allies moved against the Japanese, culminating in the atomic bomb tests at the Bikini Atoll, the namesake for the bikini bathing suit, introduced by a Frenchman in 1946. The largest oil spill in history soiled the beaches of Kuwait and Saudi Arabia in 1991, when Iraq purposely released oil to frustrate beach landings by U.S. Marines in the Gulf War. In 2010, the BP Deepwater Horizon blowout in the Gulf of Mexico became the largest oil spill ever to occur in North America.

Upper A busy summer beach scene in Fréjus, France. The beach is backed by a seawall designed to protect buildings during storms.

Lower People on the beach in Kuwait. More than half of the people on this beach appear to be nonswimmers, but there are many ways to enjoy a beach. Photo courtesy of Miles Hayes.

Having been erased by erosion and flooded by the rise in sea level, archaeological sites are less common on today’s beaches than they were in the past, but we can guess that early humans used the beach in much the same way as today’s third world coastal communities and subsistence cultures do. The beach was their land road, and just as for today’s subsistence societies, from the Arctic to the tropics, living next to the beach is living next to one’s main source of food. Places near the beach were also dump sites for garbage. Termed “middens” by archaeologists, massive piles of shells are common in many coastal settings near beaches and tidal flats where food resources were common. Today on Bazaruto Island, Mozambique, and in other coastal subsistence societies, local people still contribute to growing shell middens.

From the North Slope of Alaska to the tropical shores of the Pacific in Colombia, beaches continue to be workplaces and storage places for fishing boats, and spaces for net- and fish-drying racks. In the tropics, sea breezes provide relief from the heat and help reduce malarial mosquitoes. The beach itself is a resource for construction material and for whatever bounty the sea delivers. The people of such communities live by the sea by necessity; it is their means of life. With a vista to see who is approaching, a beach provides security. But living next to the beach, particularly on low-lying coasts, presents great risks, as demonstrated by the great tsunami of 2004 that roared across thousands of miles of Indian Ocean beaches and killed 225,000 people—including those who were there by necessity and those who were there by choice.

Dubai beach sign noting that only women can swim here on certain days. Women can be accompanied by males, provided they are four years of age or younger. On tourist beaches in Dubai, however, almost anything goes!

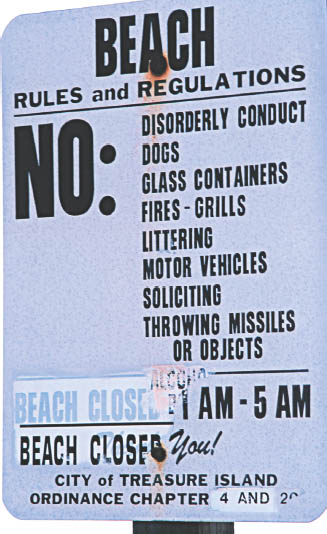

A sign posted at a beach in Treasure Island, Florida. As traffic increases, more traffic regulations are emplaced. The same is true for the density of beach use. This sign is typical of the increasing need to regulate multiple uses on beaches, but sometimes it looks like having fun is prohibited!

In contrast to beaches that support subsistence cultures, urbanized shores are mostly characteristic of first world countries. The combination of the shore as a place of commerce and the shore as a place of leisure is probably as old as humankind. The ruins of Roman and Greek villas by the sea attest to a very early resort mentality, whereas ancient Peruvians built massive temples and dug grave sites near their beaches. It was not until the nineteenth century that beaches became a greater focal point for technological and recreational development. In 1801, the first American advertisement for a beach resort (Cape May, New Jersey) appeared in the Philadelphia Aurora. In 1845, the Sanlucar de Barrameda beach horse race began in Spain, and beach horse races in Laytown, Ireland, commenced in 1876. The first successful transatlantic telegraph cable, completed in 1866, crossed the beach at Heart’s Content, Newfoundland, in the west, and at Valentia Island, Ireland, in the east. In 1898, gold was mined on the beach at Nome, Alaska. In 1903, the speed of a horseless carriage was timed on the beach at Daytona Beach, Florida. Beginning in 1905, Duke Kahanamoku rejuvenated the Polynesian sport of surfing, which the Hawaiian missionaries had halted earlier for being ungodly. In 1927, the same year that Charles Lindbergh landed the Spirit of St. Louis on the beach at Old Orchard Beach, Maine (the airport was fogged in), beach volleyball was introduced to Europe in a French nudist camp. “Beach music” started in 1945. In 1953, Deborah Kerr and Burt Lancaster made love on a beach (Halona Beach, Hawaii) in From Here to Eternity. The Beach Boys rock band formed in 1961. In 1963, Frankie Avalon and Annette Funicello starred in the surfing classic Beach Party, and in the 1968 movie Planet of the Apes, Charlton Heston and Kim Hunter, riding horseback on a beach, discovered the ruins of the Statue of Liberty.

The site of Eric the Red’s Viking village on the northern tip of Newfoundland. The mounds of earth record the sites of individual buildings that were once close to the shoreline. The sea level is dropping here because the land is rebounding from the removal of the weight of the former ice sheets. The marsh in the background was once a small harbor and is uplifted and now preserved.

Beachfront condominiums in Dunkirk, France. This peaceful scene belies the violence that occurred here in 1940 as the British army avoided annihilation and escaped back to England. The small bunker in the foreground is all that remains to remind us of the historic event that occurred here. The tide range at Dunkirk is nearly 20 ft (6 m), and at low tide the beach is often more than 435 yd (400 m) wide, with four to five sand ridges on the intertidal beach.

Upper An aerial view of a heavily oiled beach along the Saudi Arabian shoreline. The oil was spilled purposely by the Iraqis in January 1991, during the Gulf War, in order to prevent a seaborne invasion by coalition troops. This was by far the largest oil spill in history, amounting to as much as 520 million gallons. Although oil now is no longer visible on the surface of the beach, concentrations of oiled sand can be found within a foot or two of the surface. Photo courtesy of Miles Hayes.

Lower A pool of oil on Grand Terre Island, Louisiana, in May 2010, one of the early results of the BP Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico, the largest oil spill in U.S. history. The horrific oil pool here provides a beautiful reflection of the clouds. Photo courtesy of Adam Griffith.

From the post–World War II era to the present, coastal resort communities have experienced rapid growth. This time period also has witnessed the greatest losses to both coastal property and, more significantly, the beaches themselves. The 1962 Ash Wednesday storm along the U.S. East Coast caused beach loss so significant, particularly in New Jersey, that it precipitated the U.S. national beach nourishment program. This approach has been widely adopted, leading to many artificial beaches internationally (see chapter 12).

Independent of the fact that beaches have played a significant role in history, these natural systems are quite amazing and unique in their behavior. Beaches are arguably the most flexible and dynamic features in nature. If we did not know better, we might think that beaches are living creatures. They do things that make sense: Beaches protect themselves during storms by hunkering down and flattening, which makes the storm waves dissipate their energy over a broadened surface. If the sea level rises, the beach does not disappear. Instead it moves up and back toward the land, apace with the water-level rise.

Viewed from the air, beaches are the thin line that marks the boundary between terra firma and the great blue expanse of the ocean. This graceful winding line is not fixed; it changes constantly. The line waves back and forth, both landward and seaward, although nowadays the line usually is moving landward by a process called shoreline retreat (also called erosion or migration). It is fair to say that most of the world’s beaches are retreating, partly in response to a rising sea level.

The beach changes its shape constantly, whether viewed in cross section or in profile. The alert beach visitor who comes to the shore in different seasons may see large differences. Some changes may occur within a few hours during a storm, and some may manifest over the course of months, as the beach responds to seasonal differences in wave energy. When engineering structures are put in place to hold the shoreline still and protect buildings, the beach behaves quite differently than it does in its natural state. Usually it becomes narrower and over time may even disappear altogether.

Beaches range in color from white, as on the coral beaches of Pacific atolls, to pink in Bermuda, to yellow-brown on southeastern U.S. beaches, to black on volcanic islands. A few beaches have strange colors (see chapter 3); for example, Papakolea Beach, Hawaii, where the mineral olivine is concentrated, has green sand, and Northern Labrador has red beaches, which reflect the color of abundant garnet.

Even smaller features of beaches, those just beneath our feet, change very frequently and rapidly with each breaking wave’s swash and backwash, with each gust of wind, with whatever organisms are working on or within the sand. These various beach surface features, referred to as bedforms, give particular character to the beach and are as fascinating as the shells and the flotsam and jetsam that are often the focus of our beachcombing. These features often raise the most questions in terms of what, how, why, and when, as beach aficionados attempt to “read” the beach.

A healthy beach is a dynamic beach, but humans tend to think of beaches as permanent in their location, and they dislike natural features that move about, particularly when people have placed buildings in the path of such movement. In fact, the only real enemy that beaches have is us.

Upper Known as the Glidden midden, this accumulation of shells was left by years of Native American shell fishers at Damariscotta, Maine. The midden is eroding and providing an abundance of shells to the beach.

Lower Scallop shells discarded on the beach at Portavogie, Northern Ireland. These shells came from a seafood-processing plant that started operations about twenty-five years ago. The shells are still accumulating in a modern midden.

Peruvian beach at Chan Chan, near the city of Trujillo. The mound of sand is believed to be the ruins of a large temple built close to the shoreline, and hundreds of robbed graves (depressions) are visible in both the foreground and background. This Peruvian coast is a desert environment, which means that vegetation plays a much smaller role in forming and maintaining sand dunes than in more temperate climates.

From remote Eskimo villages in Siberia or the barrier island villages in Nigeria, to shoreline urban developments such as the Gold Coast of Australia (with its eighty-five-story beachfront condo) or the endless line of high-rises on Saint Petersburg Beach, Florida, the greatest fear of all beach inhabitants is the landward movement of the beach. On the Gold Coast and on Saint Petersburg Beach, Florida, communities erect seawalls and make artificial beaches to replace the native sand. In Nigeria and Siberia, where less money is available, houses are often moved back from the beach. Ironically, the result is that beaches often remain more pristine in poor societies than in affluent ones.

All of these generalizations about shape, color, surface features, and changes pertain to sandy beaches. Many beaches in the world are made up of sand, but many also consist of gravel (throwing-size pebbles), cobbles (grapefruit-size stones), and even boulders (rocks too big to lift), depending on where the beach material came from. In high, Northern Hemisphere latitudes, many beaches are made of glacial sediment, carried to the site by the now-retreated glaciers. Some rocks on Danish beaches came from Norway, and some material on Irish beaches hails from Scotland, indicating that various beach materials were transported many miles from their original locations. Sand on many beaches originated as rocks that were located hundreds or thousands of miles away and were weathered and transported by rivers. In contrast, the white sand on the beaches of many tropical islands was transported only a few meters from offshore reefs. Some boulder beaches are derived from disintegrating cliffs at the back of the beach, or just “upstream,” where the beach connects to an eroding bluff. Gravel beaches also may be derived from concentrations of seashells, coral fragments from offshore reefs, or adjacent streams and rivers that carry mainly gravel. Arctic beaches are commonly gravel.

Sometimes long stretches of shorelines have no real beaches at all but have mudflats instead. Perhaps the most famous such occurrence is the shoreline north of the mouth of the Amazon River in Brazil. It is along this shoreline that Amazon River sediment is transported by waves and currents, and because the river carries very little sand, the “beaches” are broad mudflats, stabilized by mangrove forests, all the way up to Suriname, more than 400 miles away.

Halona Beach, Oahu, Hawaii, where Deborah Kerr and Burt Lancaster made love in a scene from the movie From Here to Eternity. This is a pocket beach, a common type of beach on volcanic coasts like those of Hawaii. Photo courtesy of Norma Longo.

Microscopic view of Hawaii green sand, composed mainly of the green mineral olivine, a few pink to cream-colored shell fragments, and black sand-size rock fragments.

Occasionally a beach is virtually hidden from view by logs or seaweed. In Spencer Gulf, Australia, some beaches are completely covered with a thick layer of sea grass washed up from adjacent shallows. In some beaches in northern Brittany, seaweed, formed as a result of overfertilization of nearby farm fields, is sometimes piled a meter deep on local beaches. The rotting seaweed produces toxic gases that have been lethal to animals—not a good recommendation as a tourist hot spot. Beaches off the Mississippi River mouth are covered with plant detritus (salt-marsh straw) from the extensive salt mashes of the delta. So much grass is deposited there that natural gas formed by the breakdown of the organic matter is emitted from holes in the beach.

In remote areas adjacent to the mouths of major rivers, logs and driftwood that float down the rivers virtually cover the beach. At the mouth of the Magdalena River on Colombia’s Caribbean coast, for example, beaches to the west of the river mouth are hidden from view by the log cover. Abundant logs on the beaches of Oregon and Washington states and British Columbia, Canada, shift without warning as waves strike them and have proven to be hazardous to beach strollers.

Beaches also have been the landing sites for oil spills. The 1969 oil spill in Santa Barbara, California, provided the United States with a dramatic wake-up call to the problem. Since then, most spills have come not from oil production areas such as Santa Barbara but from shipwrecks (see chapter 12).

A beautiful white carbonate sand beach in the British Virgin Islands. The white color is typical of beaches made up entirely of calcium carbonate skeletons of marine plants and animals.

While nature throws up obstacles to our trip along the beach in the form of rocky outcrops, boulders, or mazes of driftwood and fallen trees, the larger accoutrements from human activities also provide obstacles. All sorts of objects cross beaches. In the Gulf of Mexico, hundreds of pipelines carrying oil and gas traverse the beaches on their way to refineries and storage facilities. In the latter half of the nineteenth century, many telephone and telegraph cables, some transoceanic, angled off to the ocean under the beach sand. During the Cold War, the United States and the Soviet Union, laid many miles of cable intended to reveal the presence of “enemy” vessels, both on the surface and submerged. One of the listening stations was at Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, where at least once some mysterious cables appeared on the beach after a storm.

Then there are the artifacts of war. Pillboxes, watchtowers, antisubmarine canon emplacements, antiaircraft batteries, forts, antitank and anti–landing craft structures, and searchlight platforms still abound on the beaches of various combatant countries. Many have fallen into the sea or are stranded on the beach. A few have been made into beach houses; they are perfect for storm-resistant dwellings, but given their low elevations they are unsuitable fortresses in which to ride out coastal storms.

Lighthouses all over the world have crossed the beach on their way to oblivion as shoreline retreat caught up with and then passed their sites. In a famous 1999 move, the 3,500-ton Cape Hatteras Lighthouse in North Carolina was moved back 2,000 ft (610 m) to save it from storms and the retreating shoreline. The foundation ruin of its predecessor lighthouse resides on the inner continental shelf, just offshore.

An Antarctic boulder beach occupied by local inhabitants (gentoo penguins). Beaches here are covered in ice every winter, so winter storms have little impact on beach evolution. Often the beach material on the scarce Antarctic beaches is ice rafted. Since a small iceberg that might be grounded here could drift in from a wide variety of locations, the beach is often made up of a wide variety of rock types. Photo courtesy of Norma Longo.

Intertidal bars (sand waves) on a mainland Gulf of California beach, made by both wave and tidal current action. The tops of the sand waves seen in this aerial photo are light brown in color because the sand has been dried out by wind. They are spaced about 300 ft (91 m) apart.

A mother grizzly bear and her cub grazing on barnacles at low tide on an Aleutian rocky shore. You would not want to go ashore at this location. The beach material here ranges in size from large boulders to pebbles.

Imagine approaching a beach only to find musk oxen preventing your access to the shoreline. These musk oxen are on the beach at Cape Espenberg along the Chukchi Sea, well above the Arctic Circle in Alaska. Photo courtesy of Owen Mason.

The most frequent obstacles one encounters on beaches, however, are the engineering structures that attempt to hold back the sea. Seawalls, fields of groins, and breakwaters, along with other beach construction such as piers, often in a state of failure or ruin, interrupt beaches’ natural topography and ultimately cause the loss of the beaches’ natural ambiance (see chapter 12).

This eighty-five-story condo on the Gold Coast beach, Australia, may be the highest beachfront building in the world. The problem with high-rises such as this one, and even smaller ones, is that they reduce the flexibility of a community to respond to sea-level rise. Moving an entire resort community of high-rises to higher ground is impossible, and the community is not likely to be defended when the sea-level-rise crisis comes, because funding will go to protect ports, industries, and urban areas.

Natural beaches are in fact threatened by at least three major human actions: engineering, mining, and pollution. So many beaches are just elongated engineering projects that one sometimes gets the impression that engineers run beaches. The entire coast of Belgium is lined by seawalls. Miles and miles of the southern coast of Spain are walled. Sometimes the shoreline is lined by sand-trapping groins, which are short walls built perpendicular to the shoreline. Long walls, called jetties, next to inlets and navigation channels sometimes extend more than a mile into the sea. They prevent sand from clogging the navigation channel, but they, along with groins and seawalls, cut off the sand supply that nourishes downdrift beaches. Finally, piles of rock called breakwaters are mounded in the water off beaches to reduce the impact of storm waves on the beaches and the houses landward of them. They perform well in small storms but fail during big storm events, as do the other structures mentioned here.

Fundamentally, engineering applied to a beach is done with the philosophy that preservation of buildings is more important than preservation of the beach. Beaches or buildings; we can take our choice.

Beaches are mined all over the world. The most important product is sand, many tons of which are used in construction projects. There is hardly a beach in the world that has not been mined at one time or another on scales ranging from wheelbarrow loads, as on Pacific atolls, to multiple front-end-loader and dump-truck loads, as in Morocco (see chapter 3). Elsewhere, just about any valuable mineral that comes down a river is mined from beaches, including gold in Nome, Alaska; diamonds in South Africa and Namibia; iron in California and Oregon; tin in Indonesia; titanium in Australia; zirconium in Brazil; and uranium in India. The minerals sought are usually a component of the “black sands” that commonly include the minerals zircon, cassiterite, monazite, magnetite, ilmenite, limonite, garnet, staurolite, and rutile.

Logs on a beach in Puget Sound, Washington. In forested areas such as this, logs are an integral part of the beach and its ecosystem. If the logs are “cleaned up” (removed), rapid erosion often ensues. Photo courtesy of Tom Terich.

This pipeline in Bay Marchand, Louisiana (Gulf of Mexico), extends from the shore to the offshore oil rigs that can be seen in the distance, and stretches landward across the shoreline. The beach here consists almost entirely of salt-marsh peat covered by seaweed. Often such pipes are buried in the beach and are not visible to the beach stroller.

The term beachcomber first referred to eighteenth-century Europeans on South Pacific islands who combed the beaches for edibles and anything else that came ashore. Many of them were sailors who, tiring of the dangerous and difficult life of sailors of that day, jumped ship when the opportunity arose. Beachcomber took on the connotation of a vagrant living on the beach. Today, the term refers to a major recreational activity enjoyed all over the world. Beachcombing ranks as one of the top beach activities, and the treasures one finds can contribute to an understanding of some aspects of the beach.

One never knows what a stroll on a beach will reveal. Everything that floats on the surface of the oceans or that is moved landward by waves in shallow water can end up on the beach. The beach is the landward edge of a gigantic ecosystem, and everything that dies and floats, from whales to microscopic organisms and their shells, may eventually make it to the beach. Hunting seashells is perhaps the most celebrated activity on the world’s beaches. On Sanibel Island, Florida, shell seekers come out on the beach in the middle of the night with flashlights, seeking shells at low tide and at a time when they will encounter less competition from other shell seekers. On the world’s barrier island beaches, shells that appear to be fresh may actually be fossils that found their way to the beach as the island moved landward over former lagoon shell layers. Some shells on beaches are thousands of years old; a few are millions of years old (see chapter 10). Other treasured beach finds include colorful glass net floats, often from far away, colored glass fragments rounded by wave abrasion (called beach glass or mermaid’s tears), crab-trap floats, lobster traps, bones and skulls of various marine organisms, turtle shells, and whale bones and baleen. Not-so-treasured beach finds include tar balls, which are the remnants of oil spills, much plastic debris of all sizes, shapes, and colors, freshly broken glass, and rotting carcasses of various marine organisms.

This 8 in (20 cm) cannon, now fallen on the beach along with other defensive structures in the background on Xefina Island, Mozambique, was part of the coastal defenses that protected Maputo, the capital, during World War I. All over the world, implements of war, including pillboxes, watchtowers, and gun emplacements, now reside on the beaches or are entirely submerged because of shoreline retreat.

Items from faraway places are found on beaches, and some of these are very strange indeed. Coconuts and mangrove seeds from the tropics are occasional components of mid-latitude beaches. In fact, specialized collectors search for sea beans and drift seeds, inventorying their finds and competing for the largest or farthest-traveled of particular species (for example, a Mary’s bean, also known as a crucifix bean, has been found approximately 15,000 mi [more than 24,000 km] from its source). Bales of raw rubber, sized for transport in dugout canoes on the Amazon or Orinoco River, have been found on Puerto Rican beaches in the Caribbean. Logs from exotic tree species from hundreds and even thousands of miles away are mixed with logs from local trees.

In the 1950s, thousands of U.S. Navy mops showed up on a very remote Pacific Coast beach off Baja California, Mexico; they were seen by only a few people. In 2008, long reaches of Suffolk, United Kingdom, beaches were piled deep in lumber from a ship that lost its load in a storm. In contrast to the appearance of the mops in Mexico, this beach incident made most of the world’s newspapers and TV news programs. We imagine local folks became true beachcombers in these two instances, salvaging mops and lumber. Certainly salvaging is still important on third world shores. Subsistence fishermen in Colombia collect beach sandals (flip-flops) from the wrack and trim the soles into disc-shaped floats for their nets.

Upper left The 3,500-ton Cape Hatteras Lighthouse, on the Outer Banks of North Carolina, was threatened by a retreating shoreline and was moved back 2,000 ft (610 m) from the shoreline in 1999. Built in 1870, the original location was about the same distance back from the shoreline as it is today. The $12 million move was strongly opposed by local politicians, who feared it would draw global attention to the local shoreline erosion problems (it did). Photo courtesy of the U.S. National Park Service.

Lower left A groin in front of beach hotels in Rhodes, Greece, that has clearly widened the beach in one direction (updrift) by trapping the sand, but has caused a sand deficit and beach loss in the other direction (downdrift). Chairs on the widened beach indicate heavy use of the beach by tourists, but the narrowed beach is much less useful for public recreation. Photo courtesy of Norma Longo.

Upper right Part of the massive seawall that stretches in one style or another along Belgium’s entire shoreline. Judging from the wet-dry line, there is little to no beach here at high tide, a global problem with seawalls. When the beach disappears, tourists are entertained by the view from the promenade on top of the wall. Note the World War II bunkers to the right (green belt).

Lower right Seawall with a promenade in Nusa Dua, Bali, Indonesia. Southeast Asia has become a popular beach tourist destination.

In 1991, sixty thousand Nike shoes were released from spilled containers carried on a storm-tossed ship, and many eventually ended up on beaches on all sides of the Pacific Ocean. Upon arrival on the beaches, the shoes were still usable, once cleaned, and beachcombers organized exchange get-togethers during which one could trade a left for a right shoe or a size 9 for a size 12. In 1995, twenty-nine thousand rubber duckies and other bath toys were released into North Pacific waters near the international date line, again from containers washed over a ship’s side. Within ten months, the first rubber duckies appeared on Canadian beaches.

Some beach debris is gruesome. In 2008, two young girls playing on an Arbroath beach on the east coast of Scotland found the head of a woman wrapped in a plastic bag. The origin of the head remains a mystery. Also in 2008, over a period of several months, five running shoes washed up on British Columbia beaches, each with a human foot still inside. Four were left feet and one was a right foot. The identities of the owners of the feet also remains a mystery. In the 1970s, a local physician found a piece of shipwreck timber on a North Carolina Outer Banks beach. The piece of cypress wood had two clumps of rust on it separated by a few inches. Close examination of the rust revealed fragments of a fibula and tibia in each. The explanation: The wood fragment was part of a slave ship that sank with its human cargo shackled to ship timbers, unable to escape. More recently, in January 2010, wreckage from an Ethiopian airliner carrying ninety passengers washed up on a Lebanese beach.

Beware of this one. This Portuguese man-of-war has tentacles that can give a devastating sting. Although not true jellyfish in spite of their appearance, these threatening species are found all over the world in warm waters. If spotted on a beach, they should be looked at but not touched, and beachgoers should be aware that they are likely to be in the water column as well, so swimmers and waders should be wary.

In 2008, Hurricane Gustav drowned thousands of the invasive rodent nutria in the marshes of Louisiana. Storm currents eventually washed seven thousand nutria carcasses up on the beach of Waveland, Mississippi. Old-timers in Waveland tell of a hurricane in the distant past that washed dozens of dead cattle onto the same Waveland beach. The cattle had been grazing on the narrow, low barrier islands, just offshore from the community.

Solid waste disposal on land is a problem, but the accumulation of such waste along the global shoreline is reaching a crisis point. Ships that throw trash overboard, communities that put their wastes, liquid and solid, into the sea, the great infusions of debris and trash that are introduced into coastal waters in every hurricane and typhoon, are impacting all marine environments, but especially beaches. The following examples describe only a small portion of this pervasive problem.

The aftermath of Hurricane Ike, which struck the Texas coast in 2008, left tons of refuse on Texas beaches. A month after the storm, the beaches’ appearance was described as that of a “dump,” and the trashed beaches extended for a hundred miles from the point of the storm’s landfall. At the same time, a zone of floating trash some 80 mi (129 km) long was still located offshore, and onshore transport continued to bring this debris to the beaches for months afterwards—not a happy situation for the coastal communities there that depend on beaches for tourism.

Upper left A debris-laden seawalled beach in Newcastle, Northern Ireland, shortly after a storm.

Center left A debris line left along the Galveston, Texas, shoreline after Hurricane Ike in 2008. Even after the beach is cleaned up, debris from such storms may wash up onto the beach for years. Beachcombers often find valuables from destroyed homes, including jewelry, money, and the like. There are a number of urban legends associated with post-hurricane beach scrounging, including the alleged, but never quite verified, discovery of a can containing $100,000 after Hurricane Ike.

Lower left Shoes on a beach in Sefton, England, along with an abundance of razor-clam shells. Shoes are a common component of beach debris, almost as common as caps and other headwear, blown off the heads of unwary fishermen. It is a little more difficult to explain why shoes are so common on beaches, though forgetful bathers perhaps stay in the water while the rising tide steals their footwear. Even stranger are the five shoes that showed up on beaches on Vancouver Island, British Columbia, Canada, with human feet still attached, a mystery that has yet to be solved.

Upper right Trash on a beach in Kashima, Japan. Much of this trash probably came from offshore, where it was dumped by passing vessels, large and small. Most beaches in Japan are periodically cleaned of such debris.

Lower right Trash on beaches is all too common, and animals rooting in beach garbage follow. These pigs are rooting in the beach litter at Mezquital on an inlet of the Laguna Madre, Tamaulipas, eastern Mexico.

Following is a list of some of the interesting things (excluding the vast variety of shipborne garbage and the wide variety of dead marine organisms) that we (the authors) have spotted over the years as we have wandered about on beaches.

Bikinis and swimsuits

Bottles containing messages

Bricks

Caps and hats (by the hundreds)

Cars and their sundry parts

Coconuts and large seeds, far from their origins

Computers

Elephant tusks (fossil and modern)

Fossil shark teeth and other marine vertebrate remains

Fossil shells and bones

Glass and cork net floats from distant shores

Houses

Native American arrowheads on Chesapeake Bay beaches

Kitchen sinks

Life preservers, rings, and rafts

Fishing lines (miles of them) and other fishing paraphernalia

Lobster- and crab-trap buoys (by the hundreds)

Lobster-trap buoy from Maine on an Irish beach

Logs

Marijuana bales

Mops

Navigation markers

Pottery fragments (modern and prehistoric)

Bales of raw rubber

Shipwrecks and shipwreck timbers

Spanish soccer ball on a Moroccan beach

Stone-age tools on a Portuguese beach

Vacuum cleaners

Whales

Whale vertebrae

World War I cannon on a Mozambican beach

World War II bunkers, pillboxes, artillery platforms, and observations towers

World War II ordnance

On the Pacific Coast of Colombia, the city of Buenaventura (population 320,000) used to dump its solid waste into Buenaventura Bay. With the right tide and wind conditions, this flotsam would float out of the bay and into the ocean, ending up on nearby barrier island beaches. During storms, the trash was carried landward, into the interior of the rain-forest-covered barrier islands. Ironically, buried trash items could then be used to estimate the age of storm-overwash sand deposits on the islands. We hasten to point out that most Colombian beaches on the Pacific are beautiful and pristine.

Shipwreck on a beach in Okhotsk, Siberia. Beaches in this vicinity have numerous shipwrecks, which in most cases are actually abandonments rather than wrecks. Photo courtesy of Nicolas Epanchin.

Myths and legends are easily created on beaches like the fog-shrouded Koekohe Beach, Otago, New Zealand, where the mysterious Moeraki Boulders might have been placed by giants. In fact, the boulders are resistant concretions that formed millions of years ago in the mudstone formation that is today being eroded by the Pacific’s waves, leaving the rounded masses in the otherwise sandy beach. Photo courtesy of Brad Murray.

Latin beaches are not the only ones with a trash problem. In a single year the following items were found on a Massachusetts beach: refrigerators, shoes, lightbulbs, portable toilets, stepladders, tires, toys, balloons, batteries, fishing lines, crates, clothes, and much more.

Hats and caps are a common component of beach debris, most often blown off the heads of boaters and fishermen trolling just offshore. Shaving lotion, whiskey, vodka, gin, and beer bottles of all descriptions, brands, and nationalities are commonly found on beaches. If the bottles have resided on the beach for a few months, they may become frosted—abraded by wind-blown sand. Sometimes trash can be the nucleus for dune formation on the uppermost beach. Sand accumulates on the lee side of obstacles such as bottles and logs, and if vegetation is established, a dune may form.

Every few years, medical waste, including blood bags and syringes with needles, ends up on New Jersey beaches. In 2008, medical waste was found in a 50 mi (80 km)-long offshore garbage slick, with identifying labels indicating that the material came from two New York hospitals. Apparently the material, which was supposed to be burned in an incinerator, was hauled offshore by a contractor, who dumped it all close to the coast.

Imagine the change in the heart rate of the first beach strollers who spotted lead ingots on a South African Beach. Certainly these must have initially been mistaken for gold or silver ingots. The bars came ashore because of a strange quirk in the nature of storm waves. As anyone who has snorkeled near a surf zone can attest, breaking waves rock the water column back and forth. As it turns out, the forces that push bottom material in a landward direction are stronger than the forces that move it back toward the sea. Thus the lead ingots from a shipwreck were inched forward (in storms), centimeter by centimeter, until they reached the beach. The sand moved back and forth, too, but the ingots moved in only one direction, toward the beach, in response to the strongest currents.

Occasionally land animals find themselves on a beach where they don’t want to be. Poisonous copperhead snakes are found (rarely) in the surf zone off some Outer Banks islands of North Carolina, probably washed to sea in a river flood. In South Africa, two years after the enactment of a prohibition on driving on almost all of the nation’s beaches, leopards were occasionally spotted loping along the swash zone. Apparently when cars were still whizzing by, the big, shy cats avoided the beach, which was a normal part of their range.

Beaches are a natural laboratory for the study of physical and biological processes and unique environments that have persisted through geologic time and left a rock record. Our fascination with beaches is what led us, four geologist authors, to write this book. In our combined one hundred plus years of studying beaches, we have each arrived at an appreciation of beaches that goes beyond the science. We have come to love the subject of our studies and to see the unique beauty in beaches. Besides the obvious exquisite experience of strolling on a beach, hearing the roar of the surf, and feeling the wind and the salt air, we have learned that a beach is a complicated creature that evolves in complex, yet predictable ways. We also have learned that the beach leaves all kinds of fascinating clues as to how it works, how it was formed and shaped; its surface is a record of timed events from the last season through the last week to today and the last few seconds. The beach is a natural mural waiting to be read and interpreted.

When you finish this book, you will know about beach characteristics ranging from the broadest scale of different types of coasts down to the individual beach features, including barking sand, heavy minerals, bubbly sand, the array of ripple marks, the significance of stained shells, and other interesting phenomena. In the end we hope that you too will feel the beauty in the beach as we do and that you will understand how it responds to tides, waves, and wind, how the critters that live in the beach manage to survive, and how humans can destroy the very features that we find unique.

Finally, we fear for the future of beaches. In this time of rising sea level, whether developed beaches survive or not will depend on how society answers the question, Which is more important, beaches or buildings?