Nature, to be commanded, must be obeyed.

FRANCIS BACON, NOVUM ORGANUM

The single greatest threat to the future of the world’s beaches is not storms or rising sea level. It is us. The threat comes not from nature, but from humans in our attempts to control the beach. Beaches, left to their own resources, are extremely resilient. As a rule, natural beaches are nearly indestructible; indeed, it appears that beaches have discovered the fountain of youth. Whatever the level of the sea, beaches will persist. Every rule, of course, has exceptions, and in a few instances beaches can meet their demise by natural circumstances (e.g., small beaches in non–coastal plain settings may run up against rock cliffs, the natural sand supply may be cut off, or the relative sea-level rise may be rapid enough to overwhelm the shore, as in the case of rapid subsidence due to an earthquake or a sinking, abandoned delta). In most cases, however, even in big storms, the beach survives and, given time, repairs itself from storm damage. The media may say a particular hurricane or storm has caused “beach erosion” or “severe beach loss,” but a visit to the shore tells us the beach is still there (perhaps sans buildings).

All over the world, we have crowded buildings up against the shoreline, right next to beaches that are widely recognized to be retreating (migrating landward). But instead of moving landward with the rising sea level as they naturally would, these beaches are forced to stay in place in order to protect the buildings. Clearly some people value buildings over beaches and are often willing to protect buildings even at the price of the loss of the beach.

A wide beach masks the spectacular events that have taken place on appropriately named Washaway Beach in the U.S. state of Washington. A careful look at the photo reveals four pipes protruding from the beach, lined up in the offshore direction. Each of these pipes extended to a well from a house that has long since fallen victim to storms and beach retreat. Over the last decade or two, four houses have fallen here.

The biggest long-term threat to buildings next to the shoreline is sea-level rise. The sea level is rising because the surface waters of the oceans are warming and expanding, and ice sheets and glaciers are melting. In the early twenty-first century, the rate of global sea-level rise was a bit more than 1 ft (0.3 m) per century. All indications are that the ice sheets’ melting rate is increasing and that sea-level rise is accelerating. We believe that 3 to 5 ft (0.9 to more than 1.5 m) of sea-level rise should be expected by the year 2100. In fact, a 7-ft (2 m) rise is not out of the question.

Three feet (0.9 m) of vertical sea-level rise does not sound spectacular, but for low-lying, gently sloping coasts characteristic of the world’s coastal plains in China, Brazil, and the United States, the resulting displacement of the shoreline will be far inland. Three feet of sea-level rise will be enough to halt all development on the world’s barrier islands as we know them. Three feet will flood much of the city of Miami, Florida, and large portions of other cities such as Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; Venice, Italy; New Orleans, Louisiana; Durban, South Africa; Lagos, Nigeria; Gold Coast, Australia; Tel Aviv, Israel; and Cadiz, Spain„to name only a few. Low-lying island nations already are feeling the consequences of the sea-level rise (e.g., the Maldives in the Indian Ocean; Tuvalu, Kiribati, and others in the Pacific Ocean). Outside of the cities, a worst-case scenario is that many of the world’s beaches that are accessible to tourists will become engineering projects. Most beaches will become roads for bulldozers spreading newly placed sand or constructing seawalls in an attempt to hold back the sea to protect buildings, foolishly placed next to the ocean.

The only “solution” to the erosion problem that minimizes harm to the beach is to move buildings back from the shore, demolish them, or let them fall into the sea. This, the so-called retreat option, is routinely practiced in the developing world but is less attractive in the world of wealthy and politically influential beachfront property owners, who opt for engineering solutions instead.

The “we shall not be moved” approach confronts the sea-level rise with either or both of two common engineering responses: hard stabilization or soft stabilization. Both are very damaging to beaches, especially the shore-hardening approach.

This motel at South Nags Head, North Carolina, extends beyond the midtide line on the open-ocean beach. One of the first medium-rise buildings on the Outer Banks, it was built well back from the beach, but a steady erosion rate of 3 ft (1 m) per year has moved the beach into this position. More than forty rooms now have a beautiful view of the sea, although one might wish to check the weather forecast before renting one of them.

These buildings along the much narrowed beach in front of the Mar Menor, Spain, seawall are in a hazardous zone. The round columns on the beach are part of the sewer system that has been exposed by shoreline retreat.

Since the time of the ancient Romans, humans have attempted to engineer shorelines by building hard structures to hold the shoreline in place. Hard stabilization consists of putting something hard and “permanent” on the beach. Most common are seawalls (and their cousins, revetments and bulkheads), which are walls built parallel to and on the landward, or back, side of the beach. A seawall may be a wall of concrete or steel; a line of rocks, logs, or sandbags at the top of the beach; or a massively engineered structure such as the walls in Galveston, Texas, and along the coast of Belgium, the coastal defenses surrounding much of Holland, and the walls on the barrier islands protecting the Venice lagoon and the city of Venice, Italy. Many esplanades on urban shores are in effect glorified seawalls, including well-known examples such as Brighton, England; Nice, France; Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; Tel Aviv, Israel; Beirut, Lebanon; and Colombo, Sri Lanka.

In the United Kingdom, seawalls are particularly common in resorts, where many were built to support concrete promenades rather than as sea defenses. The seawall in Blackpool often is topped by waves during storms. The Dawlish seawall protects the southwest coast railway line, and trains frequently have to stop running during storms. The possibility of rerouting the southwest railway line has been discussed, but it was ruled out by local government. The seawall from Hopton in Norfolk to Corton in Sussex was closed to the public in 2008 after a storm damaged the wall.

The remnants of sandbag seawalls litter the beach after the passage of Hurricane Ivan on Galveston Island, Texas. Sandbag seawalls are often viewed as a compromise solution to be used instead of concrete. The problem here is that such remnants are seldom cleaned up, leaving behind a highly degraded beach after the sandbag seawalls are destroyed.

Three generations of sand bags are visible on the beach at Figure 8 Island, North Carolina. The oldest set is the white fragments visible in the foreground. The second sandbag seawall was made up of the black sandbags that can be seen in the middle of the photo. At the time the photo was taken, a third sandbag seawall was located up against the dune scarp.

Destruction of the beach in front of a seawall is largely a passive process that can take years or decades. The wall is constructed because the shoreline is retreating, but the wall does not address the wave and current processes that are causing the shoreline to retreat. Thus, after the wall is put in, the beach continues to retreat, getting narrower and narrower as it backs up against the wall. Eventually the dry beach disappears.

This process usually takes a few decades, but it can happen much more quickly. In the United States, this fact has been recognized by some, and Texas, Oregon, South Carolina, North Carolina, Rhode Island, and Maine have all taken steps to limit and even outlaw seawalls and other hard structures on their beaches. But politics in democratic societies often favors development over environment, and it is difficult to halt the march of seawalls along developed beaches.

In the United States, the state of Florida is in the worst shape of all and provides a good illustration of the secondary effects of seawalls. The walls provide a sense of security, which encourages construction of high-rises. It is one thing to move cottages back from a rising sea level and retreating shoreline, but a twenty-story condominium is another matter. The point is, large buildings will precipitate heroic attempts (that will inevitably fail) to hold the shoreline in place, and meanwhile the beach will be history. The state of Maine recognized this effect twenty years ago and banned all buildings taller than 35 ft (10 m) from coastal sand dune areas.

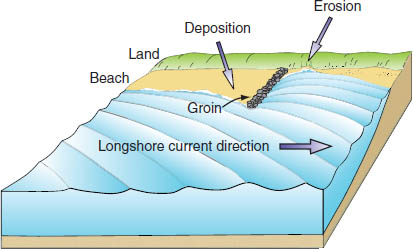

Another approach to hard stabilization is construction of walls built perpendicular to the shoreline called groins (groynes). These structures are designed to trap sand that is transported along the beach by longshore currents and thus widen the beach. Groins range in length from a few tens of feet to a few hundred feet and are successful in widening a beach when there is sand available. The problem is that the shore to which the trapped sand was going (the adjacent beaches) is now suffering a sand deficit, which of course leads to increased erosion rates there. Perhaps the most spectacular damage done to beaches by groins occurs along much of Portugal’s open-ocean coast north of Lisbon. Most of these groins were put in place less than three decades ago.

A very crowded, narrow pocket beach in Estérel, France. Beach volleyball was invented in France, but the court would be narrow for a game here. Presumably the seawall is responsible for the narrowed beach.

Groins are just about everywhere on the south coast of the United Kingdom. Brighton, Bournemouth—all the main seaside resorts have them. In fact, groins have become a part of the traditional English seaside resort landscape. Interestingly, in Barcelona, Spain, the local government created an unexpected uproar when it removed some groins and nourished the beach instead. It turns out that the groins had divided the beach into de facto zones used by families, the gay community, the nudist community, and so forth, and their removal had removed the zones!

Jetties are a generally larger form of groins that are placed adjacent to tidal inlets and river mouths to keep sand out of navigation channels. These structures also have the potential to trap huge quantities of sand and wreak havoc on the downdrift beaches that would have received the trapped sand. Just that has happened in several well-known U.S. examples, including Ocean City, Maryland and Charleston, South Carolina. It is estimated that half of the erosion of Florida’s beaches results from jetties at inlets. In some locations, where the inlet is also the mouth of a river that delivers sand to the beach, a jetty can cause erosion by depriving the adjacent beach of river sand. Camp Ellis, Maine, is an example of that sad situation. Such long-term erosion effects also are evident in many United Kingdom and European examples, where jetties have been in place for very long periods of time. Offshore breakwaters are a third species of hard-engineering structures, consisting of a wall built parallel to the shoreline, but these are positioned offshore a few tens or hundreds of feet. These structures reduce wave energy reaching the shoreline by creating a wave shadow on the beach, interrupting the longshore current, which causes the wave-transported sand to stop and accumulate. In other words, a breakwater has an impact similar to that of a groin, in that it causes the beach to widen at one point at the expense of the downdrift beach, which narrows or disappears.

Upper left This seawall on the Majuro Atoll, Marshall Islands, is made of gabions, wire baskets filled with rocks and shells. The seawall holds back the landfill of the town of Majuro. These gabion wire baskets are notorious for corroding within five to seven years, rupturing and spilling their contents on the beach and becoming a hazard to walking on the beach. If not replaced, their failure will allow the refuse to escape, creating a pollution hazard. Thousands of coastal landfills around the world are threatened by the sea-level rise.

Upper right This unique version of a seawall in French Polynesia is made of palm logs, facing the open ocean on an atoll. Obviously this wall was made from local materials! Note the concentration of coral and associated carbonate sediment derived from the offshore reef (white strip). The high tide regularly reaches the wall, which offers little protection against a big storm.

Center upper left An eroding landfill on the Puget Sound shore, Port Angeles, Washington. The shoreline was walled in 2006 to halt the erosion (for a while). Courtesy of Hugh Shipman.

Lower right The Galveston, Texas, seawall probably is the mightiest seawall on any barrier island in the world. Constructed after a 1900 hurricane that killed six thousand citizens of the city, the wall caused the eventual narrowing and disappearance of the dry beach as the beach and offshore slope steepened. A rock revetment was placed at the toe of the wall to protect its foundation. As steepening continued, a second rock revetment was put in to protect the first rock revetment.

Center lower left This seawall at Salinopolis, Brazil, just south of the Amazon River mouth, was flanked by accelerated erosion at the end of the seawall, rendering it useless. Instead of protecting property, the wall has caused littering of the beach and contributed to the shoreline erosion hazard. Seawalls, once installed, always require extensive and expensive maintenance.

Lower left This seawall in British Columbia, Canada, was built from logging-operations debris. As is commonly the case, easily available local materials are used to make seawalls, but no matter the type of materials, on eroding shorelines, seawalls cause beach loss.

A diagram of the effects of a seawall. A rigid wall reflects and refracts wave energy, causing erosion in front of the wall and concentrating energy at the ends of the wall, also resulting in erosion. The net effects are beach narrowing, beach steepening, and the ultimate loss of the beach in front of the wall; breaching at the end of the wall; and the cutoff of the sediment supply to downdrift beaches. Drawing by Charles Pilkey.

Unfortunately, large storms over-whelm breakwaters and damage or destroy the buildings the breakwaters were designed to protect. Holly Beach, Louisiana, hosted a vast replenished beach and offshore breakwaters far more costly than the beach houses they were built to save on the “Cajun Riviera.” When Hurricane Rita struck nearby in 2005, the breakwaters withstood the storm quite well, but the sand and houses were virtually all lost.

A field of natural groins is the result of low rock ridges caused by outcropping rock layers that strike perpendicular to the beach. Sand has accumulated on one side of the natural groin (middle of photo) and caused the shoreline to retreat on the other side (background). The only individuals impacted by this sediment deprivation would be the beach mammals and birds that frequent this beach on the Antarctic Peninsula. Photo courtesy of Norma Longo.

A good example of offshore breakwaters in the United Kingdom is at Sea Palling in Norfolk. In the Blackwater Estuary in southeast England, a line of sixteen old barges was sunk about 550 yd (500 m) offshore to create some very unusual offshore breakwaters.

Some confusion exists when discussing shore-hardening structures because of differences in terminology between countries. Jetties, as defined above, are called training walls in Australia, while they use the term jetty for what are termed recreational piers in North America and the United Kingdom. In New Jersey, groins are sometimes called jetties. But regardless of the name, these are all hard structures that impact shorelines.

All in all, if preservation of beaches for future generations is a high priority, all forms of hard stabilization should be avoided. This means of course that, in a time of rising sea level, buildings must be removed and the shoreline must be allowed to march onward. This option is unreasonable in an urban setting. Cities such as Tokyo, Singapore, and New York City are not going to retreat as the sea level rises. The priority in an urban situation is preservation of the buildings and infrastructure, but along most of the nonurban ocean shoreline, we believe the priority should be preservation of beaches and not the defense of beachfront houses.

This groin in Portugal clearly has blocked the sand movement from left to right. In Portugal, installation of a number of such groins along the Atlantic coast created erosion problems along more than a hundred miles of shoreline. Photo courtesy of Miles Hayes.

Although the designation soft may be misleading, soft stabilization refers to engineering designs to hold beaches and dunes in place by artificially adding sediment or, in the case of dunes, using vegetation to trap and hold sand. Most commonly for beaches, this approach involves the construction and maintenance of artificial beaches by the process of dredge and fill or by hauling in sand to place on the beach, referred to as beach nourishment or beach replenishment. Although marketed under the pretext of protecting beaches, this soft approach again is usually aimed at protecting property (buildings and infrastructure), not the beach habitat. Nevertheless, this approach has become the solution of choice for many retreating beaches in the developed world. Construction of artificial beaches, however, is simply too costly for the developing nations.

Diagram of the effects of groins. Groins block the natural alongshore drift of sand, cutting off the sand supply to downdrift beaches and contributing to their erosion. Several groins are usually placed along a beach (groin field), magnifying the effect. Often they are ineffective during storms, breaching on the landward end and losing their trapped sand. Drawing by Charles Pilkey.

Such replenishment is carried out either by dredging sand from the seafloor and pumping it to a beach or by transporting sand with trucks from inland sources. Dredging is usually carried out in lagoonal waters, in tidal inlets, or on the adjacent continental shelf. The cost in the United States ranges from $1 million to $10 million per mile of open ocean beach. On a volume basis, the U.S. cost of sand ranges from $2 to $40 per cubic yard, and the volume of sand per mile of beach is usually between 150,000 and 1 million cu. yd. (between about 115,000 and 765,000 m3). The life span of nourished beaches is quite variable, ranging from days (Cape Hatteras, North Carolina) to as many as two decades or so (Miami Beach, Florida). Most replenished beaches on the U.S. East Coast have life spans of between three and five years.

A view of groins from a cliff top in Lima, Peru, shows sand moving from the top to the bottom of the photo. The narrowed beach in the foreground is starved of sand and shows well-developed beach cusps (bottom center) and an erosional scarp at the back of the beach cutting into the upland, which eventually will threaten the road.

The Dutch require that sand for beach nourishment of the Frisian Islands must be obtained from water depths of 65 ft (20 m) or more. This means that the North Sea sand is dredged from over the horizon. This distance is important because if depressions are dredged on the continental shelf too close to the shoreline, they will alter wave patterns on the beach, often leading to accelerated erosion in unwanted locations. Elsewhere in the world, including sometimes in the United States, dredging is frequently carried out within a matter of a few hundred yards of the beach, often contributing to rapid loss of the artificial beach (as happened in Grand Isle, Louisiana).

Another problem is with the choice of sites from whence to obtain sand. On barrier islands, the highest-quality and cheapest sand is found in inlets. The sand in inlets is beach sand that reached the inlet by longshore currents. The problem with mining inlets is that the hole that is left behind rapidly fills with sand that would otherwise have crossed the inlet to the beaches on adjacent islands. Thus, mining sand in inlets to halt erosion ultimately causes increased erosion on nearby beaches.

Surprisingly, after a half century of beach-nourishment projects around the world, there are relatively few studies of the impact of such projects on the biota. Beaches and their associated inner shelf areas are part of the nearshore ecosystem. The construction of artificial beaches certainly impacts beach fauna during the construction phase, and there are a limited number of studies to suggest that the impacts are longer term, perhaps permanent in some cases.

The Five Sisters (five breakwaters) protect Winthrop Beach, Massachusetts. The natural beach disappeared long ago, and large seawalls and groins protect property along with the breakwaters. The breakwaters create a “shadow zone” of lower wave energy, and tombolos are forming. These sand bodies are accumulating from the shore to the breakwaters and almost connect the breakwaters with a replenished beach. The tombolos in turn prevent any longshore transfer of beach sand from behind this structure, cutting off the sand supply to the downdrift beach.

The food chain of the beach begins with the debris washed up on the shore, and the nutrients carried in water from the ocean and the land. These nutrients sustain the microscopic animals that live between the sand grains and go up through a complicated web of feeders including crabs and mollusks to the birds and fishes that feed on them. Each level in the ecosystem depends on all the others. Adding to the mix are the small mammals that scavenge whatever washes up on the beach and, where possible, eat the eggs laid by the turtles and birds on the beach. The lions that survive on the Namibian desert coast by eating dead whale carcasses are one of the most bizarre examples of beach scavengers.

Needless to say, the animals that live on and in the beach are used to extreme events such as storms. The living things in the beach are frequently moved about, buried, and unburied, and somehow they manage to survive. However, beach nourishment creates a different set of stresses on the organisms. On a large nourished beach, most living things are killed when they are buried by a yard or more of sand in a very short period of time. Eventually the organisms come back, reestablished from populations from adjacent beaches, as long as the new sand on the artificial beach is about the same size and composition as the original beach. If the new grain sizes and composition are not compatible, a whole new type of fauna may arrive. If the nourished sand has a lot of mud, the new fauna will be very different indeed. Recovery of the living things in an artificial beach depends on their mobility, but complete recovery probably takes several years.

A grounded supertanker off Goa, India, is acting as an offshore breakwater, causing the local beach in front of the restaurant to build out. At the time this photo was taken, the tanker had been grounded for more than a year. Photo courtesy of John Gunn.

A cascade of sand slurry (the pipe mouth is in the sand mound) being pumped onto a beach at Durban, South Africa, for beach nourishment. The sand is dredged from the adjacent port entrance, where it accumulates as a result of longshore drift from the south, and then pumped to the beach. This operation of bypassing the sand across the channel is carried out once a year, every year. The young man in the foreground is probably looking for seashells.

Also, many of the areas impacted are offshore, out of sight, where invertebrate populations live on so-called hard grounds, where meadows of sea grasses thrive, where fish nest and feed, and, in tropical regions, where coral reefs need clear waters to thrive.

The biological impacts of nourished beaches also involve the shorebirds that nest on the beach. These include various plovers, sandpipers, terns, and skimmers. Studies have shown that an artificial beach changes foraging behavior, leading to more feeding time and less food. Decreased parental time leads to predator problems for the newly hatched chicks. The density of nests usually declines dramatically, as nesting shifts to other beaches. Turtles too have problems on nourished beaches. They sometimes can’t dig through the compacted sand and can have their flippers cut to shreds by sharp shell fragments broken up in the dredge hopper.

The quality of sand used to make an artificial beach is one of the biggest issues in coastal engineering. All over the world there are examples of nourishment sand that is of poor quality—too muddy, too rocky, too shelly. A number of Spanish replenished beaches are reported to be muddy sand. In the state of North Carolina, which has laws requiring “compatible” sand for artificial beaches, there have been artificial beaches that are rocky (Oak Island), shelly (Emerald Isle), full of construction debris (Holden Beach), and muddy (Atlantic Beach). In all cases, the site for obtaining the sand was poorly sampled in an effort to save money, and government failed to halt the emplacement of poor-quality sand. In the rush to save the beachfront property, it seems anything goes.

This close-up view of a shell hash on a newly nourished beach on Emerald Isle, North Carolina, shows how nourishment can sometimes degrade a beach. The original beach was composed of a more uniform sand with a pleasant tan color (the area is known as the “Crystal Coast”), but the new beach was very coarse due to an abundance of broken shell material, and dark gray in color because of the high content of black shell material. The initial new beach was made up mostly of shell hash, including much larger shells than shown here, and the broken shells had sharp edges. The beach was no longer a pleasant barefoot experience. With time, the finer sand winnowed out of this material to cover the shell hash with a thin layer of sand, but in the intertidal zone that people cross to go swimming, shoes were required because of the abundant sharp shells. The dark color also lessened with exposure. Courtesy of Adam Griffith.

Beach bulldozing or scraping is another soft method of protecting buildings. Sand is bulldozed or scraped from the low-tide beach up to the back of the beach to form a “storm dune” (an artificial sand dike) to provide temporary protection to buildings during minor storms. This approach provides no long-term protection, however, because no new sand is added to the beach. The scraping has the added disadvantage of destroying the beach fauna.

Beach grooming is a common procedure on recreational beaches to make them more pleasant for tourists, but this is another damaging process in terms of the impact on the tiny creatures that live within the beach. In addition, beach grooming may contribute to shoreline erosion. One hotel owner on the island of Roatán, Honduras, indicated that the elevation of the hotel’s beach was lowered by 1 ft (30 cm) after a few years of daily raking. About half of all of Southern California tourist beaches are groomed once a day, and the urban beaches of Los Angeles are often raked twice a day to pick up garbage, cigarette butts, cans, and whatever else people leave behind. Usually such grooming is done by raking, but sometimes it is carried out by sieving the sand. In either case, the living organisms are largely removed. Even dune-building plants that may be creeping out onto the beach from nearby dunes are routinely killed. A bold Least Tern that chooses to nest in the most seaward clump of dune grass will be a potential victim of overzealous beach grooming. In any case, the beach becomes a sterile desert. One solution is to alternate groomed and nongroomed areas or to hand clean the beaches, perhaps using volunteers who love beaches and who love to stroll on them. Some Belgian beaches are now routinely hand-picked, specifically to remove garbage but leave natural beach debris behind.

This erosion scarp on a nourished beach at Kashima, Japan, exposes shell hash and dark-colored sediment. Scarps are almost always present on nourished beaches, a sign that the new beach is eroding much faster than the previous natural beach. A clue that this beach is artificial is provided by the fact that all of the shells are white and mostly fragmented.

Invasive and alien species can result from activities that are well-intentioned or deemed harmless. Artificial plantings of nonnative plant species to stabilize dunes are an example noted earlier. Almost every dune system in the world has examples of plant species that originally were introduced into flower gardens but then spread into the dunes at the expense of native species. In coastal regions in the Caribbean and southeastern United States, Australian pines have been planted as windbreaks and for their aesthetics, but these trees grow to the edge of the back of the beach and cover important nesting grounds for birds in particular that would be attracted to the otherwise open sand flats. Australian pines have shallow root systems and are notorious for blowing over in hurricanes and blocking roads as well as littering back-beach nesting grounds.

Several alien animal species have negatively impacted North America’s Great Lakes, but none more so than the zebra mussel. These prolific small clams have clogged water intakes and outfalls, altered water quality, and grown to such abundances that in some places their shells have become the dominant material on local beaches.

Beach driving, or vehicular traffic on beaches, deserves special mention. Whether or not to allow vehicles on beaches is a contentious issue in many countries. Daytona Beach, Florida, is famous for its liberal beach-driving policies, which have been in place for more than one hundred years. The Texas Open Beaches Act acknowledges a right of people to drive on the beach that is greater than the right of people to have a house on the beach. In northwest Europe, where there are many wide beaches with hard surfaces of fine sand, there is a long tradition of driving normal two-wheel-drive cars onto the beach. Beach parking lots are even provided, and a fee is sometimes levied for car access to the beach. In South Africa, as mentioned earlier in the book, beach driving was recently halted in the entire country, and within two years beach life had sprung back very impressively. Australian beach managers are working to restrict beach driving in that country to protect and restore habitat.

Post-storm beach bulldozing (beach scraping) on a hazy morning at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. The sand is pushed up to the beach cottages to provide a buffer against the next storm, but such sand dikes (they are not dunes) are quickly whisked away in storms. The seagulls are gathering for the free lunch provided by the bulldozer as it exposes (and destroys) the beach ecosystem.

The problem with beach driving is that heavy traffic does essentially the same thing to the beach fauna that grooming does. People who fish and surf are the main culprits, but sightseers and those who just want to try out their four-wheel-drive vehicle are among those crowding beaches. In addition, some “outlaw” drivers wander into the dunes, killing nesting birds, destroying beach vegetation, and destabilizing dunes. Beach driving is a practice that should generally be opposed if the quality of beaches and dunes is to be maintained for the majority of beach users.

The problems of beach pollution are widely recognized around the world. The most obvious major pollution source comes from untreated or partially treated sewage. Often treatment plants are overwhelmed in heavy rainfalls, and raw sewage is added to the storm-water runoff. In beach communities, malfunctioning septic tanks are a big problem. Dangerous conditions in beach swimming areas can be determined by analysis of the water for certain pathogens and indicators (e.g., E. coli bacteria). Certain organisms, including some types of seaweed, are also indicators of pollution. Off of Adelaide, Australia’s shore are areas of extensive sea grass loss, caused by industrial and wastewater discharge. This loss has been directly correlated to an increase in the volume of sand on the adjacent beach.

Workers grooming the beach in the Maldives, Indian Ocean. The use of rakes is certainly better for the beach fauna than tractor-drawn and heavy mechanized beach sweepers. Nonetheless, such beach cleaning disrupts the beach microfauna, creating breaks in the food chain that lead all the way up to the fish cruising in nearshore waters. It is better to hand pick the trash from the beach.

This pile of refuse on a Bali beach in Indonesia is the result of an effort to clean trash from the beach. Globally, such scenes are common as beaches accumulate wrack from human sources, usually dominated by plastic. Places like Bali and Sumba Island still have beautiful beaches, but they are threatened by solid waste, as seen here. Photo courtesy of Claude Graves.

Australian Pines line the back of this Bahama Islands beach, unusual in that they grow almost to the high-tide line, so they commonly fall to erosion and accumulate in the back-beach area. The trees are a problem for tourist recreational beaches and a serious problem for birds that nest on the upper beach. The Australian pine here and in much of the Caribbean and south Florida is an invasive species. Photo courtesy of Sidney Maddock.

It is important to remember that on polluted beaches, building sand castles with wet sand and other beach activities can be just as hazardous to one’s health as swimming in the polluted water.

A partially buried car on Washaway Beach, Washington, leaves one wondering how it got there. A look to the background tells part of the story: a bare scarped bluff face, downed trees, and remnants of an infrastructure. This beach is eroding at more than 100 ft (30 m) per year, and we can conjecture that the car’s fate was due to a storm and shoreline retreat that caught up to a house and driveway.

One way to ensure that the beach where your family swims is safe is to use Blue Flag Beaches only. The Blue Flag Beach Programme of the Foundation for Environmental Education (www.blueflag.org) has approved more than thirty-three hundred beaches in twenty-nine countries in Europe, the Caribbean, Canada, New Zealand, and others. The requirements for approval include good management and good water quality.

In the United States, the Natural Resources Defense Council publishes an annual report (www.nrdc.org/water/oceans/ttw/ttw2009.pdf) on the quality of beach water at two hundred of the most popular beaches in the United States. The primary causes of pollution are storm-water runoff and sewage release. More than twenty thousand brief closures occurred at these beaches in 2008. The worst U.S. beaches were in the Great Lakes and the best were along the shores of the southeastern United States.

On April 20, 2010, the mile-deep BP Deepwater Horizon oil spill began in the Gulf of Mexico when the blow-out preventer on the sea floor failed and the oil rig exploded. This spill exceeded the Exxon Valdez disaster to become the biggest oil spill in U.S. history. The well was finally sealed on September 19, 2010, after gushing close to five million barrels of oil into the Gulf. The impact of this spill will be felt for decades to come, and it is the harbinger of spills yet to come.

Upper Tire tracks on beach sand rich in heavy minerals. The tracks are rather striking because they were made on a beach surface with a thin layer of white sand underlain by a thicker layer of black heavy-mineral sand. Vehicular traffic on beaches damages bird and turtle nesting areas and also impacts the microfauna within the beach—damage that goes unseen.

Lower Tire tracks on the beach at Doñana, Spain, are deep and abundant. Designation of such an area as a park has little effect in terms of conservation if driving on the beach is allowed. No successful nesting will take place here, and the beach fauna will be sparse as well.

Many beaches in the world have small tar balls waiting in the sand for the unwary stroller to step on, blackening the soles of their feet. Some resorts along Mediterranean and Caribbean shores provide beachgoers with brushes and cans of solvents to remove oil from bare feet upon leaving the beach. Tar balls, some as small as sand grains, are the end product of oil spills after all the light components of the oil have evaporated away. Most are the result of small amounts of oil released into the ocean by passing ships, a practice that has decreased dramatically in recent years.

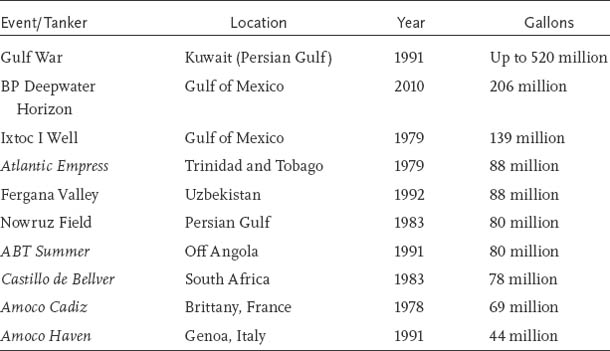

Oil spills, especially the largest ones, which occur as a result of accidents with tankers and wells, provide the most spectacular pollution incidents for beaches. There are two kinds of oil spills: chronic and episodic. Chronic spills are those that occur frequently in the vicinity of ports where there is ship traffic. Episodic spills are the occasional and relatively uncommon (at any given location) release of oil after an accident of some kind, often involving a tanker. The largest oil spill in history was the 1991 Gulf War oil spill in the Persian Gulf, which resulted from the purposeful release of at least 140,000 tons of oil by Iraq to stymie an expected amphibious landing by U.S. Marines. The ten largest oil spills in today’s oceans as of 2010 are shown in Table 12.1.

The second largest spill in U.S. waters was the Exxon Valdez, which dumped 11 million gallons of oil into Prince William Sound in Alaska in 1989 and oiled portions of an 1,100 mi (1,770 km) stretch of shoreline, including sandy and rocky beaches. Although this spill ranks thirty-fifth on the all-time list by volume of oil released, it was one of the most damaging environmentally because of where it occurred. The oil residues from that spill can still be found at depth in the beach sediments, twenty years after the event. Similarly, the Kuwaiti and Saudi Arabian oiled beaches and tidal flats in the Persian Gulf have been slow to recover, and concentrations of oil are present at a foot or two below the surface. In contrast, the BP Deepwater Horizon spill initially appears to have been less damaging to Gulf of Mexico beaches than one might expect, given the size of the spill. This is not to say that there wasn’t beach damage: beaches in Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama particularly were affected, as were marshes in Louisiana and the offshore fishery. The true extent of the total damage to habitat may never be known.

Table 12.1 The Ten Largest Oil Spills in Today’s Oceans as of 2010

A TOXIC GREEN WAVE ON THE BEACH by Sharlene Pilkey

With beaches all over the world already under attack from sea-level rise, mining, driving, seawall construction, and encroachment by human development, another menace is mounting an assault—and humans are behind this one too. Articles in the Guardian (August 10 and August 21, 2009) reported that lethal green algae have invaded heavily used vacation beaches in Brittany, northern France, and along England’s coastline from Wales to Portsmouth. These deep piles, up to 3 ft (1 m) thick, with hard, crusted tops, are stinking, ticking gas bombs.

Vincent Petit, a twenty-seven-year-old veterinarian, was horseback riding on a Brittany beach near St. Michel en Grève, when his horse broke through the crust and went down. A cloud of hydrogen sulfide gas was released from the rotting algae, reportedly killing the horse within thirty seconds. Fortunately a tractor was nearby; it was used to clear away algae and drag Mr. Petit to safety. He was rescued in an unconscious state and hospitalized. He reportedly was suing the local municipality, which was responsible for beach maintenance.

On June 22, 2009, on the Côtes d’Armor, a forty-eight-year-old maintenance worker clearing dead algae from the beach was stricken and died, apparently from a heart attack, but the lethal rotting vegetation is suspected in his death.

This abundant accumulation of marine algae on the French coast was apparently the product of overfertilization of nearby fields and drainage emptying into the sea. Towns along the Brittany coastline have hired bulldozers to scrape the seaweed away, but more is brought ashore by waves.

Previously, on a beach near Mr. Petit’s accident, two dogs met their death from the gaseous fumes. In a strange coincidence indicating the global nature of this problem, the death of two dogs running on an algae-encrusted beach was recently reported from the north of Auckland, New Zealand, as was the death of four dogs killed in 2009 by toxic beach algae near Elkton, Oregon.

The more one learns about this beach hazard, the more apparent its global scope becomes. In 2008, the Chinese government brought in the army to clear away the slimy green growths so the Olympic sailing competition could be held and so observers could safely view the event. In Italy, near Genoa, a sixty-year-old man had to be taken to the hospital because he swam in algae-infested water, and also in Genoa, more than two hundred people were sent to hospital after swimming in the algae or inhaling toxins carried to the beach by the wind. During the summer of 2009, officials in Massachusetts put out a toxic-beach-algae warning but did not close the beaches. And the problem extends to freshwater lake beaches as well.

Some are attributing the algae outbreaks to global warming. Although this may indeed be a factor as our seas warm up, it is clear that excess nitrate-rich fertilizers, along with animal wastes and poorly treated or untreated sewage, are the main villains.

The problem is greater than just the hazard it poses to humans. When a beach is covered with algae, virtually everything that lives on and within the beach is killed, while access is denied to nesting and to food for local birds, fish, sea turtles, and various crustaceans. Thus, an entire beach—nearshore ecosystem, which includes microscopic organisms (meiofauna) living between sand grains at the bottom of the food chain up to sharks cruising offshore, is wiped out. Simultaneously, oxygen is usually depleted in nearshore waters, which creates a threat to marine mammals and seabirds.

Although politicians are finally beginning to pay attention to this danger and take action, as in France, the problem comes down to the use of fertilizers to boost food production on farms and agribusinesses along the coasts and nearby rivers. They must recognize their responsibility to be good stewards and adopt agricultural methods that protect the coastal waters. Beaches are not only habitat, but the basis for human economies as well. The more than seventy troubled beaches in northern France and along the English coastline from Cardiff Bay to Portsmouth Harbor are highly visible examples of worldwide coastlines under the threat of a range of pollution problems. Is this toxic green wave the future for the world’s beaches?

Beach cleanup procedures are costly and very damaging environmentally. Sometimes the damage from cleaning a shoreline is probably, in the short run, more damaging than the spill itself. Different shoreline environments have different susceptibilities to spilled oil. A vertical rock cliff would be the least susceptible, followed by more susceptible sandy beaches, tidal flats, and, most vulnerable of all, marshes and mangrove swamps. Fine-sand beaches are less susceptible than coarser-sand beaches because in fine sand the oil penetrates only about 0.5 inch (1.3 cm) due to lower permeability. The coarser the sand on a beach, the more damage a spill will cause because of increased penetration. Gravel and boulder beaches are particularly vulnerable (e.g., as in the impact of the Exxon Valdez spill). Thus, high-latitude beaches on glaciated coasts are particularly susceptible. Arctic beaches are commonly made up of gravel, and many tropical beaches associated with coral reefs are very coarse sand and gravel; hence, all are susceptible to spills.

Coauthor Joe Kelley is leaning on a septic tank exposed on the beach after a nor’easter caused extensive shoreline retreat at South Nags Head, North Carolina (November 2009). The septic tank had been exposed in previous storms and was then reburied with trucked-in sand. After this storm, however, the houses were condemned and the owners were ordered to remove them. In the background, beyond the line of light-brown sandbags, is a blue house that was in the third row of houses back from the beach twenty-five years ago. Now the house is in row number one, next to the beach, waiting its turn to fall into the sea.

Bubbly sand (see chapter 7) and the effects of burrowers (see chapter 9) counteract the grain-size effect. Oil has been observed to penetrate into the beach as much as 1.3 ft (40 cm) in bubbly sand and to greater depths in deep burrows associated with crabs and ghost shrimp. Thus, on this account, the vulnerability of beaches on the southeastern U.S. Atlantic will vary considerably. Georgia beaches have both more Callianassa burrows and more and thicker bubbly sands than beaches in North Carolina and therefore are more endangered by oil spills, even though they are finer grained than the North Carolina variety.

Upper left An oil-covered boulder beach along the shores of Prince William Sound in Alaska, from the 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill (11 million gallons). Oil penetrates deeply into boulder beaches and is almost impossible to remove, as attested by the fact that oil from this 1989 spill is still present in beaches more than twenty years later. The process of oil removal is always environmentally damaging in and of itself. Photo courtesy of Jacqueline Michel.

Upper right Swash lines made up of spilled oil (69 million gallons) from the 1978 Amoco Cadiz disaster off the coast of France. Oil penetration is not as severe on fine-sand beaches providing the sand is well sorted, not bubbly, and not burrowed; however, not many beaches have this set of properties. Photo courtesy of Jacqueline Michel.

Lower This dark pool of oil on Isle Grand Terre, Louisiana, from the May 2010 BP Deepwater Horizon oil spill is only a small local example of the extensive environmental disaster that spread along the Gulf of Mexico coast. Every high tide brought more oil to the beaches, sounds, and marshes. The penetration of the oil into the sediment is a function of the grain size: The coarser the grains, the greater the penetration is the rule. Needless to say, all living beach creatures will probably be killed in a locality such as this. Note the drilling platform in the far background. As these facilities age, and as drilling proceeds into deeper water and less stable seafloors, more such spills will occur. Photo courtesy of Adam Griffith.

Oil spilled on beaches eventually disappears, but how quickly it goes away depends on the amount and type of oil that was spilled and the local climate. Early in World War II, many beaches in Europe, the Caribbean, and along the U.S. East Coast were blackened by spilled oil from tankers sunk by submarines. Most beaches recovered in a few years.

An oil-covered beach in Urquiola, La Coruña, Spain, in the “cleanup” after a 1976 oil spill, clearly a horror story. Photo courtesy of Miles Hayes.

Beaches have found the fountain of youth. Absent the impact of humans, few natural beaches ever need salvation.

Beaches protect themselves from storms. Beaches flatten and produce offshore bars during storms, processes that reduce the impact of big storm waves and limit beach retreat.

Beaches have different personalities. Different types of waves, the frequency of storms, and variability in grain size, composition, and the sand supply give each beach its uniqueness.

Beaches never create an erosion problem. Those who build next to the beach create the problem.

Beaches are damaged by shoreline engineering. Whether by the emplacement of an artificial beach or by the construction of a boulder seawall, engineering alters beach dynamics so the natural beach and its ecosystem will never be the same.

Beach mining goes on at every scale, from the local horse-and-cart operation to the giant mineral mines in coastal sands, such as in Namibia. Here a young man is obtaining sand from a beach in Uruguay near Cabo Polonio. When you multiply the volume of this individual’s sand removal by many thousands, it can become a significant factor in beach degradation. Photo courtesy of Rob Thieler.

The greatest single threat to beaches in the immediate future is engineering. The extensive global coastal engineering effort is largely to save buildings, not to save beaches.

The greatest single threat to beaches in the longer term (more than fifty years) is engineering. The initial response to retreating beaches due to rising seas has been and will continue to be attempts to hold the shoreline in place with engineering structures and nourishment sand. The resulting costs, both economically and environmentally, will increase exponentially as it becomes more and more difficult to defeat nature over the great length of developed shorelines.

Globally, beaches can be viewed as endangered habitats. Unless there is a significant change in the philosophy of conserving the global shoreline, natural beaches will continue to be replaced by artificial beaches and become extinct, just like endangered species. Both current and future management of beaches will require much care, improvement, and foresight if the beaches are to survive in the latter half of the twenty-first century and beyond.