In different climatic settings ranging from the tropics to the Arctic, natural beaches form as a result of the interaction of tides, waves, and currents with an array of coastal sediments of different compositions, grain sizes, and sorting. Add to this the effects of wind, of organisms that rework sandy beaches, and of the breathing of beaches as they fill and empty with water and air with the rise and fall of the tide. All beaches share similarities, but because every beach has been shaped by a unique combination of local processes in the last seconds, minutes, hours, days, and weeks, no beach is the same as it was moments before, or stays the same as it is right now. The beach as we see it is shaped by the present breeze, the last breaking wave, today’s accumulated tracks of humans or of crabs and their burrows, the piles of seaweed and driftwood and sometimes plastic refuse, the last rise and fall of sea level on the tidal cycle, and the last storm. Being able to decipher the sequence of such events adds to our enjoyment of the beach.

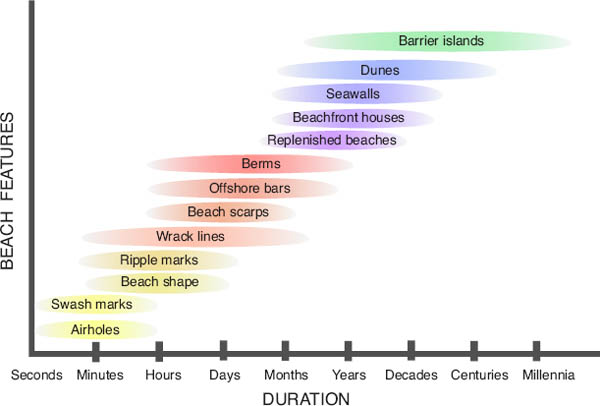

Comparison of the relative time spans for which various beach features tend to persist. Small features such as airholes and swash marks may last from only seconds to minutes, whereas large features such as dune fields and barrier islands may last from centuries to millennia under natural conditions. Drawing by Charles Pilkey.

Chapters 6 through 11 are a guide to reading the beach, focusing on features that range in size from the large (e.g., wrack lines and fields of ripple marks) to the smallest underfoot (e.g., foam traces and bubble marks). Internal features also are examined, from types of bedding produced by waves, to fabrics produced by air and water moving through the beach, to burrows, tracks, and traces of organisms.