Reading a beach usually begins with looking at large landforms, such as the berm and offshore bars, and proceeds through examining intermediate-scale features, such as wrack lines and beach scarps, and then scrutinizing the small and even tiny features we see at our feet. Landforms and features seen in the topographic profile of a beach, such as large sand dunes or a narrow and steep backshore, tell the story of overall long-term conditions including sand supply, wave energy, and the impacts of engineering that have shaped the beach over many years or even decades.

Intermediate features, such as scarped or breached dunes, washover fans, and wrack lines at the back of the beach or into the dunes, are the evidence of the most recent big storm, which might have happened anytime from years to days ago. Multiple wrack lines or erosional scarps farther down the beach reflect more recent and smaller storms, or spring high-tide lines that may have formed only weeks or days ago; the lowest, fresh wrack line is usually from the last high tide.

Beach ridges and foredunes may reflect erosion-accretion cycles over a period of months or weeks, or longer time intervals in the case of gravel beaches. On sandy beaches, the berm crest nearest the sea often is the crest of the last sandbar to have migrated or welded onto the shore. On gravel beaches, the high berms recall the last storms of winter and remain out of reach of waves until the following winter.

The most interesting features, however, are often the smallest and most recently formed (in the last hours, minutes, or seconds), which collectively give the beach its surface character. This chapter focuses on these smaller features, the so-called sedimentary structures or bedforms on the beach surface. A bedform is the term for all small physical features on the surface of a beach or dune and can be thought of as any variation from a nearly flat surface.

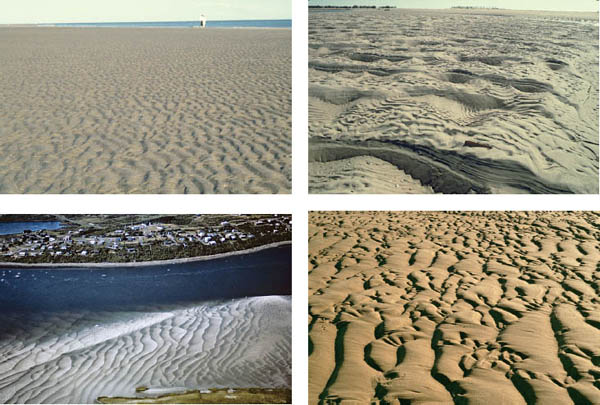

Nearshore water currents and waves expend their energy on the bottom sediments and shape the part of the beach that extends below the water surface. The sand often is reworked into various features that have a wavelike geometry (e.g., sandbars). Next to sandbars (see chapter 5), the largest of these features are referred to as sand waves, such as those formed in deep tidal channels. Although they are usually underwater, sand waves are visible in some aerial images of tidal inlets, and in areas with high tidal ranges they can be exposed at low tide on the margins of tidal channels. By definition, sand waves have crest-to-crest spacing greater than 20 ft (6 m). In shallower offshore areas, but where tidal and wave-generated currents are strong such as in the tidal channels, on the tidal deltas of inlets, and in the surf zone, megaripples can form. Megaripples are small, dunelike features with spacing between crests ranging from about 2 to 20 ft (0.6 to 6 m), and trough-to-crest heights of 4 to 20 in (10 to 50 cm). These bedforms cover extensive surfaces and migrate in the direction of the tidal or wave-generated currents. Megaripples are sometimes exposed at low tide on the surfaces of ebb-tidal deltas at inlets but are generally not seen on beaches. In cross section, megaripples are asymmetric, with a gentle up-current slope facing the direction from which the current comes, a crest, and a steep down-current face that slopes into a trough. Smaller ripples often cover their surfaces. Sand is carried up over the crest and avalanches down the steep face of the dune as it migrates. This deposition on the downdrift face produces inclined bedding within the megaripple, called cross bedding, in which the beds are inclined at up to 22 degrees, the angle of repose of medium sand in water (see chapter 11). The angle of repose is the steepest slope at which sediment will naturally come to rest when deposited on the wet surface.

The most common wave- and current-created features found on beaches and tidal flats are much smaller than sandbars, sand waves, and megaripples, but they still show the wave or ripple form from which the structure gets its name: ripple mark. Ripple marks form an undulating surface of alternating ridges and hollows, which give the surface a corrugated appearance. Their crest-to-crest spacing is measured in inches, and their trough-to-crest height is generally less than 2 in (5 cm). The ripples form as a result of turbulence from a wave or current of water (or air) that comes in contact with a bed of sand. The turbulence creates unequal forces on individual sand grains, which then begin to move by sliding, rolling, or hopping (saltation). Not all of the grains move uniformly or at the same rate, and some grains begin to accumulate, forming microridges, which cause more turbulence, allowing the ripple to grow in size. Sand grains move up the back side (the stoss side) of the ripple to the crest, and then are either carried off of the crest by the current or slide down the steeper ripple face in the direction of the wave or current movement. As a result, not only does the sand move, but the ripple form also moves in the same direction. The best way to understand this process is to watch ripples form and migrate in their natural setting. You can watch this happen sometimes in ankle-deep water in the swash zone or in deeper water using a mask and snorkel. Beach and tidal-flat ripples commonly develop in fine to medium sandy environments (grain sizes less than 0.02 in [0.6 mm] in diameter).

Upper left Ripple marks are a common type of bedform. Tidal-flat surfaces are commonly covered by extensive fields of ripple marks of different types, along with animal feeding trails and burrow openings.

Lower left Submerged sand waves and tidal sandbars in the Parker River Estuary, Massachusetts. The waveform is common in sediments and ranges in size from these very large sand waves down to very small ripple marks. Photo courtesy of Miles Hayes.

Upper right Megaripples exposed at low spring tide near Cacela in the Portuguese Algarve. The waveform has an amplitude of about 2 ft (60 cm). Smaller ripple marks cover the surface of the larger megaripples.

Lower right Current megaripples exposed in Kosi Bay, South Africa. The wave amplitude ranges from 6 to 12 in (15 to 30cm). Surfaces of the larger ripples have been modified by tidal currents to produce a lineation pattern.

Upper left Nearshore ripple marks form as a result of wave action but usually show an asymmetry in their form, with a steeper face in the direction the waves were moving, in this case, from left to right. These asymmetric ripple marks show parallel crests, low amplitude, and a tendency for lighter debris to accumulate in the troughs. Note that a single ripple in the lower middle-right foreground branches into two ripples, while two adjacent ripples merge into a single ripple, typical patterns. The scale is 1 ft (about 30cm). Photo courtesy of Miles Hayes.

Center left Sinuous wave ripple marks showing the sharper crest of this ripple type, as well as parallelism of the ripples. Photo courtesy of Miles Hayes.

Lower left Current ripple marks vary in shape but are short crested and often arc shaped in plan view.

Upper right Very small standing wave in a drainage channel across a California beach. The underwater ripple pattern is the same as that on the surface of the water.

Center right Surface waveforms in a creek mouth draining across a Puerto Rican beach indicate the bedforms developing on the sandy bottom. Note the white-water waves breaking upstream. These form over antidunes (sand is moving downstream toward the ocean, but the bedform is moving upstream). In the background, toward the ocean, there are smooth standing waves.

Two categories of ripple marks are found on beaches. Wave ripples are formed by the oscillatory (back-and-forth) current of waves and are characterized by parallel crests. A true oscillation ripple mark, formed only by the to-and-fro motion of the wave, is symmetric in cross section, with a sharp, straight crest and rounded trough. However, even when waves are a dominant factor in forming the ripples, there is usually a weak current, such as a tidal current, or a longshore current moving the sediment and causing the ripples to migrate. The result is that the wave ripples become asymmetric, with a steeper face developing on the downcurrent side of the ripple, but they still retain the parallel crests typical of their wave origin.

Most of the ripple marks found at low tide on beaches and tidal flats are of this type—mostly wave formed with the addition of the force of a weak-to-strong current. In a cross section cut with a shovel or trowel, the internal structure of the ripple shows cross laminae: individual layers or laminations of sand, often no more than a grain or two in thickness, that are inclined in the direction of the current’s flow. The laminae in ripple marks are measured in small fractions of an inch, in contrast to the typical internal layers in the larger sand waves and megaripples, which are measured in several inches to feet (tens of centimeters to meters).

When wave energy is low and the water is clear, well-formed, parallel-crested wave ripple marks are often visible near the water’s edge, just beyond the wave plunge point. The plunge point itself may be marked by coarser shell fragments or mixed sand and gravel, concentrated by the high-energy turbulence. Fields of ripples are best seen at low tide on exposed tidal flats. Although the ripple crests are more or less parallel, tracing individual ripples reveals that they commonly split (bifurcate) into two ripples, or two ripples will merge into one. This pattern results because a single ripple does not migrate at the same rate along its entire length. Somewhere along the crest line, the ripple detaches, migrates into the next ripple, and reattaches to give the appearance of either splitting or merging.

Current ripple marks result where a single-directional current (as opposed to an oscillating wave-formed current) is the dominant force transporting sand. The geometry of current ripples is significantly different from that of wave ripples. Most current ripples have short, discontinuous crests and are arcuate in form rather than parallel crested. When viewed from above, specific types of current ripples are named according to their shapes—linguoid (tongue shaped), cuspate (horn shaped), catenary and lunate (crescent shaped)—which are determined by features of the current’s flow, such as its velocity and turbulence. These ripples usually occur in groups or sequences called ripple trains.

Current ripples typically form in channels where confined currents flow. On the shore, one of the best places to find current ripples and ripple trains, and to observe them forming and evolving, is in beach runnels (troughs) and runnel outlets. These troughs between bars and berm crests, when exposed at low tide, channel the drainage parallel to the beach, and strong currents can develop in these shallows. Current ripples form and migrate downstream as the current carries sand and finer sediment. In some cases, earlier-formed wave ripples will have produced sets of ripple crests parallel to the long axis of the trough, and then the later current will superpose current ripples atop the wave ripples (and vice versa on the rising tide).

Tidal creeks and creek or drainage channels coming off the land and crossing the beach also are natural observatories for seeing the relationships that link running water, sediment transport, and the resulting bedforms. In addition to current ripples, such channels may have larger bedforms during high-velocity flow. The presence of such bedforms is revealed by the character of the flowing water’s surface. A smooth waveform known as a standing wave reflects a similarly shaped bedform on the floor of the stream. Where flow velocity changes abruptly, a hydraulic jump forms, like the white water seen at the base of a dam. Where flow velocities are very high, breaking waves form and then appear to wash out, indicating the formation of bedforms referred to as antidunes on the stream floor. These underwater features can range in size from that of megaripples to that of ripple marks, with similar spacing, and are termed antidunes because the bedforms move upstream, even though the sediment is moving downstream. The smaller antidunes occur (very commonly) when they form under the very shallow film of water (backwash) rushing back down a beach following wave run-up (see later in this chapter).

Upper left Flat-topped ripple marks formed when the current reversed and moved sand toward the bottom of the photograph. The tops of the ripples were truncated, the sand was carried into adjacent ripple troughs, and in some cases the ripples were smoothed out in the direction of flow (left of the coin). The U.S. penny is shown for scale.

Upper right Flat-topped ripple field in which some of the ripples were breached and miniature channels carried sand into adjacent troughs to form small deltalike deposits. The U.S. quarter is shown for scale.

Center left Ladderback ripple marks produced by a strong set of ripples that moved from right to left; then a later set of smaller ripples was superimposed on top of the first set at a 90-degree angle, producing the appearance of rungs on a ladder. Note the fine shell debris in the ripple troughs. The U.S. penny (shown for scale) is resting against the steep face of the ripple.

Center right Interference ripple marks on the north coast of Spain show a right-angle orientation of weaker wave ripples atop the larger ripple set.

Lower left This set of interference ripples on a Brazilian beach produced a checkerboard pattern.

Lower right Flaser ripples form when mud fills in the troughs of the ripples. The ripples on this tidal flat at Yepoon, Australia, are sand, but the flooded troughs are filling with mud settling from the water. When buried and viewed in cross section, the sandy ripples will appear to be floating in a layer of mud.

As the tide or wind shifts during a tidal cycle and the current reverses direction, the crests of the wave ripples may be eroded off, producing flat-topped ripple marks, and here and there along the ripple crests, small patches of sand are carried into the troughs like miniature deltas or overwash fans. Second sets of ripples, related to different current conditions, can be superimposed over preexisting sets to produce checkered patterns (interference ripples or cross-ripple marks) or ladderlike patterns (ladderback ripples). Where mud accumulates, particularly in the ripple troughs, during times of quiet water between episodes of ripple formation, the resulting rippled sand layers will be interbedded with mud, producing flaser ripples. Other types of ripple marks form in the swash zone of the beach face, as described in the next section.

Watching wave run-up and the swash and backwash at the water’s edge can be mesmerizing. A kaleidoscope of changing patterns and processes may be seen as the last bit of the wave’s energy dissipates on the beach, either completely soaking into the beach or turning into backflow that runs back down the beach’s face. More energy is spent in the run-up, which may have enough velocity and turbulence to roll shells and gravel-size particles, pick up sand, and transport sediment up the slope of the beach, than in the backwash. If backflow occurs, the water running back down the slope of the beach has less energy and moves finer material. Such winnowing sorts beach materials by size and, in the case of heavy minerals, by density (see chapter 3). However, if the beach is very steep and the waves are high, the energy of the backwash will be stronger than usual, and gravel-size materials and shells will be carried back downslope. Most pebble, cobble, and boulder beaches are so porous, however, that the swash usually soaks quickly into the beach itself and backwash occurs only during storms.

Ripple marks form in gravel as well as sand, as shown here in Tierra del Fuego, South America.

Gravel-size material is often sorted by shape as well as size. Strong currents also produce ripple marks in gravel. Flat pebbles and cobbles may be stacked in an imbricate pattern, like the shingles on a roof, and, as noted in chapter 3, when a steep beach is composed of gravel shingles and rounder materials, shape sorting occurs as the disk-shaped shingles are left behind on the top of the beach and the “rollers” return downslope. Sometimes the relative age of such sorting can be determined. At the rear of a gravel beach, it is common to find pebbles that differ in color from those on the more seaward parts of the beach. Careful examination shows that these back-beach pebbles not only have weathered a little, but also are encrusted by vegetation, usually lichen. The extent of lichen encrustation can give an indication of how long the pebble has been inactive; the more lichen, the longer the inactivity. Similarly, on tropical gravel and boulder beaches composed of coral rubble, the most landward parts of the beach have been exposed the longest to the effects of slightly acidic rainwater. These coral fragments have been leached, as some of the coral skeleton has been dissolved, to produce very jagged edges on the coral fragments, which sometimes are stained black.

Shape sorting in beach gravels is common. Here the sliders (ranging from disc-shaped pebbles to small cobbles) are on the upper beach (to the woman’s right), while the rollers (more spherical pebbles) are on the lower beach (to her left).

Near the water’s edge, each swash event may deposit a single lamina, or layer, of sand grains, giving the beach its internal structure of parallel laminae (see chapter 11). These laminae are usually gently inclined seaward at the same slope of the beach face (less than 10 degrees). This swash run-up, with its loss of energy and ability to continue to carry sediment, combined with the bubbly foam at the edge of the swash deposits a concentration of material that marks the farthest advance of the swash. Such swash marks are one of the most universal of surface features found on beaches. These arcuate-shaped lines, which are stranded on the beach as the tide falls, record the last uprush of water on the beach face and usually show crosscutting relationships so that a sequence of swash events can be determined (earlier swash lines are truncated by the more recent swash line). These features are also common on the landward side of emergent sandbars where a wave just barely makes it over the bar crest (or berm crest on the beach), again soaking in, leaving the material at the swash edge as a line on the back of the bar.

How long gravel particles have been on a beach sometimes can be determined by the growth of lichens on the surface of the stones. Here the “old” cobbles on the left are coated with lichen growth and appear darker in color, whereas the “new” deposit of wave-worked material (on the right) is fresher and brighter in appearance, lacking the organic surface coating. The pile of wire lobster traps marks the extent of the storm wrack line.

Swash marks are miniature wrack lines, enhanced by concentrations of heavy minerals, shells, and floating materials such as seaweed fragments, seeds, insect carcasses, and other fine particles of flotsam. The swash lines are often the focus of feeding activity by beach-dwelling creatures such as crabs and shorebirds.

Careful examination of the uppermost swash lines sometimes reveals another curiosity: evidence of floating sand. The swash line is usually a tiny ridge of sand, perhaps only the diameter of a sand grain or two higher than the surface of the beach. This microridge is due to a film of sand grains floating at the edge of the swash. Although sand is supposed to sink in water, surface tension can hold sand grains as a thin film on the water surface if there is no turbulence, and the swash mark is sometimes the deposit of this floating sand. Another location where floating sand can be found on beaches is at the edges of pools of still water in beach runnels at low tide; the sand typically appears as a scum on the water surface.

When the swash washes over the surface of the beach, it sometimes aligns or orients the individual grains so that their long axes are parallel to each other as well as to the line of the current. The beach surface appears smooth, but the parallel grains give rise to a streaked appearance, or parting lineation, and microridges and microgrooves terminate as lines more or less perpendicular to the swash marks. Because the swash curves in its run-up and because the grains may be reoriented by backwash, parting lineation sometimes shows a curved pattern, as if someone had taken a paintbrush or broom and made swooping brushstrokes over the surface of the sand.

Other seemingly mysterious surface markings result from any object moved over the sand surface by the swash where the object is in contact with the sand. These drag marks are as unique as the object being dragged along to scribe the mark in the sand, but common patterns are brushlike marks where small clumps of seaweed and algae are carried in the swash. If the object that made the mark is missing, the origin of the surface feature will remain a mystery, but sometimes the “tool” will be found at the end of the mark.

Backwash also modifies the beach surface, sometimes producing interesting patterns. One of these is the diamondlike or V pattern of rhomboidal ripple marks that form as backwash flows down a beach face of uniform sand. Steeper beach faces seem to favor their formation, and the Vs always point landward, or upslope. The one exception is where rhomboidal ripples form on the landward side of beach crests and sandbars that are overwashed by waves.

Swash marks form as each wave soaks into the beach, leaving the material it carried landward. These swash marks on a beach in Barbuda, West Indies, derive their color from the concentration of small pieces of pink coral at the swash margin. Each successive swash cuts the earlier swash marks, so a sequence of swash events can be determined. In this case, the mark in the lower left was the first event; it was followed by the middle-left arcuate mark, then the middle-right brownish mark, and finally the mark in the upper left. Each swash event left a layer of sand only one or two grains in thickness.

Similar V patterns, called crescent marks or obstacle marks, form as backwash flow scours around any larger, resistant object on the beach surface. The erosive scouring is due to the turbulence generated in the backflow around the obstacle, the same effect that gives waders that “sinking” feeling as a wave’s backwash scours around their feet. Typical obstacles include individual shells, pebbles, and clumps of seaweed; the larger the object, the larger and deeper the crescent. Once an obstacle creates a disturbance in the flow, it is propagated laterally and downslope to generate a field of rhomboid ripple marks or similar pattern. For example, small patches of either crescentlike or rhomboidal ripplelike patterns often are generated where a group of burrowing organisms is just below the sand with their antennae or feelers protruding through the surface and disrupting the flow. Some burrowers build vertical tubes that are coherent enough to form obstacles when exposed, so the apex of some crescent marks is a hole.

Any slight difference in the surface relief of the beach can create either linear scour patterns or linear depositional patterns without scour. Streaks of sand or microridges may extend in the direction of backflow from the lips of burrow holes or from other small objects that create a low-energy shadow in the downdrift direction.

Backwash down the face of a beach during a falling tide can produce the same high-velocity flow, called critical flow, that occurs in streams (described earlier in this chapter). The surface of the thin layer of backwash water will show riffles, or asymmetric water ripples, that reflect the small antidunes forming on the beach face. Although they are not as large as those seen in streams, the effect is the same. The ripple’s steep face is landward and is migrating up the beach slope, even though the sand is moving downslope (the opposite orientation of the current ripple marks). These bedforms are very shortlived and are almost always washed out by the continued swash and backwash activity, but the bases of these antidune ripples are often preserved, giving the beach a striped appearance. On beaches with high concentrations of heavy minerals, selective sorting of different-colored grains enhances the appearance of these features as light and dark sets of stripes on the beach. Where the higher part of the antidune dries out faster than the trough, a series of wet and dry stripes is also visible. At low tide, the surfaces of some high-energy intertidal beaches are completely covered in truncated antidunes.

Floating sand appears as surface patches of sand on the quiet water in a beach trough on this Lake Superior (U.S.) beach. A thin layer of surface sand, no more than a sand grain in thickness, is picked up by rising water and remains floating due to surface tension. Where there is a gentle current, the sand will be carried in the direction of flow.

The rising tide also produces some unique structures. Where waves first break over small beach scarps, return flow carries sand seaward back over the lip of the scarp. The small, saturated sand flows produce an array of intriguing patterns on the face of the scarp, as well as miniature deltas and fans at the toe of the scarp. These features are very short-lived: They are erased by the rising tide’s waves as they attack the slope, or they collapse on drying if the scarp survives.

The high-tide waves may slop over such low beach scarps and produce irregular, thin patches of wet sand over the dry beach. There may be openings in the wet sand patch, which act as windows showing the dry sand in somewhat oval or circular patterns, with curled edges on the rims of the wet sand layer.

A strong swash lineation pattern is evident, oriented from top to bottom. The pattern is a result of the alignment of the long axes of the sand grains, although they are too small to see. Note also the truncated burrow hole and the sand extrusions around the burrow openings (see chapter 9). The U.S. penny is shown for scale.

A Puerto Rican beach in which the high content of dark heavy minerals helps to accentuate the swash and backwash patterns. Recurved backwash patterns in the black sand are prominent, seaward of the swash line, in the right part of the photo. Obstacle-mark patterns are also prominent as a result of backwash flow around the clumps of seaweed flotsam.

Upper left Drag mark produced by a clump of seaweed dragged by a falling-tide current across the muddy sand of this Irish tidal flat. Drag-mark patterns vary with the different objects (tools) that leave their marks on the surface. Note the ripple marks, some of which are flat topped, the snail trails, and the mounds produced by burrowers. Footprints are shown for scale.

Lower left A large chevron obstacle mark around a pebble that is beautifully highlighted by the pink garnet sand fraction, selectively sorted by the backwash on this California beach. Note the faint rhomboidal pattern in the lower right. Photo courtesy of Miles Hayes.

Upper right Close-up of obstacle marks resulting from pebbles on the beach surface. Backwash turbulence around the pebbles resulted in scour on the upstream side and then deposition in the direction of flow (toward the top of the photo). Note the nail holes due to air in the sand. The U.S. penny is shown for scale.

Lower right Rhomboidal ripple marks produce their characteristic diamond or V-shaped pattern on the surface of this Gold Coast, Australia, beach. The Australian two-cent coin is shown for scale.

Backwash riffles in the foreground indicate that very small antidunes are forming on the submerged surface of the beach. The backwash flow is seaward and is carrying sand seaward, but the ripples are moving landward as they form, hence the name antidune. These ripples wash out quickly, but differences in grain size and grain composition result in the striped pattern that indicates that antidunes were present.

Raindrop impressions produced the pitted pattern seen over this area of a beach in the British Virgin Islands. Raindrop impressions tend to be fairly uniform in size, although they will show variation with raindrop size. The U.S. quarter is shown for scale.

Upper left Airlie Beach, Australia, provides a good example of the characteristic striped-beach pattern resulting from the formation and then truncation of antidunes on the surface of the beach during a falling tide.

Lower left The face of a beach scarp where water from the last wave to break over the scarp has washed a slurry of sand down the face, producing interesting patterns of channels, fans, and deltas. The bubble-foam line is from the edge of the last wave. The U.S. penny is shown for scale.

Upper right The edge of the slosh from a wave throwing water onto the dry beach produces a scabby pattern from the thin, irregular layer of wet sand over dry sand. The lighter patches are dry sand showing through the windows of wet sand that curls along its edges as a result of surface tension. The same pattern often appears at the most landward edge of the swash line. The U.S. penny is shown for scale.

Lower right Drip marks forming from water dripping off boulders at the back of a beach in Santa Catarina, Brazil. The resulting pits are usually larger than raindrop impressions.

Some features on the surface of the beach are so delicate and faint that they are difficult to see, but they are just as indicative of recent beach events as the more visible features. Such is the case with the marks produced by sea foam. Sea foam is formed during wave agitation of water containing organic compounds, which are added when waves churn up seafloor sediments or where tannin-rich river water enters the sea. Bubbles form and persist, creating the mass of foam, as in a bubble bath, and the foam is carried onto the beach by waves and wind. During big storms, foam can accumulate to thicknesses of several feet at the back of the beach, where it piles up against the dunes or other obstacles, including buildings. In August 2007, a foam layer formed along the Yamba, Australia, shore north of Sydney that was at least 6 to 10 ft (2 to 3 m) thick and led to the area’s new name, “the Cappuccino Coast” (see www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-478041/cappuccino-coast-the-day-pacific-whipped-ocean-forth.html). A walk through such a mass of foam will leave a gray scum on one’s clothing because inorganic clay particles are attached to the bubbles. Anywhere stormy seas are common, foam is common (in addition to the Australian coast, e.g., the U.S. and South American Atlantic and Pacific coasts, the coasts of the North Sea, the Japanese coast, and the South African coast). However, the average beachgoer does not visit the beach during storms and rarely sees foam at the height of its formation. Even during fair weather, though, small amounts of foam may be visible in the surf, and a strip of bubbles is usually seen at the edge of the swash as it runs up onto the shore. These bubble lines contribute to swash marks, as noted earlier. The bubbles of foam, as delicate as they are, leave not only traces, tracks, or trails as the swash or wind moves them over the surface of the beach, but also a pattern at the point where the bubbles dissipate. Because the bubbles disappear rapidly, they are rarely actually seen producing their delicate foam marks.

A patch of dissipating foam that moved from the base of the photo to its resting position. Note the faint parallel marks in the lower part of the photo. These are the inscribed trails or fine stripes created by the foam bubbles. The U.S. quarter is shown for scale.

Where foam clumps are moved across the beach, either on a thin film of water or in direct contact with the beach, foam stripes are formed. These faint stripes parallel the wind direction. Occasionally the wind breaks off a large clump that is carried by hops, skips, and jumps across the beach, leaving an intermittent trace (foam track) each time it touches down. When the foam patch comes to rest and the bubbles burst, a final set of bubble impressions is left as a surface trace. These bubble pits are very shallow and of variable diameters. Although they are the most faint and delicate of features, once identified, foam structures tend to be recognized over much of the wet beach. When the foam dissipates, a film of dark mud and organic material can be left on the beach surface.

Parallel bubble tracks on the surface of a Portstewart, Northern Ireland, beach. The British fifty-pence coin is shown for scale.

Foam skip marks (light patches in center) are the faintest of impressions left on the beach surface as the wind skips a ball of foam across the beach. The U.S. penny is shown for scale.

Another feature related to bubbles occurs at the wet-dry line during times when waves run well up onto the dry beach. Rather than the one-grain-thick lamination deposited by weak swash, a large wave swash will deposit a thicker layer of sand, though still less than an inch in thickness. If such a wet sand layer with bubbles is deposited over the dry beach, a scabby-looking surface develops when the bubbles burst, producing pits in which the dry sand can be seen below the wet sand. Surface tension causes curling of the wet sand around the rims of the bubble pits. These are similar to the features produced where waves slop over the crests of small beach scarps. Another common process that produces pitting is rain, but raindrop impressions differ from bubble pits in that they tend to be of uniform size and are distributed over much larger areas of the beach, as well as into any dunes that are present.

Other common, but short-lived, features over the entire surface of the beach include raindrop impressions, which are microimpact structures, and shallow craters, often with a faint rim, the result of grains being thrown up by the drops’ impact. Raindrop impressions can be confused with tiny depressions formed as a result of escaping air or water or collapsed air bubbles (see chapter 7), but these do not cover the entire beach or have the density of spacing seen in raindrop impressions. Similarly, drip marks from trees, ledges, or boulders produce pitted structures, but these are usually larger than raindrop impressions and are localized. There are also a variety of features produced by wind blowing over wet or dry beach sand (see chapter 8) and by animals leaving tracks, trails, and traces on the beach surface (see chapter 9).