The city centre

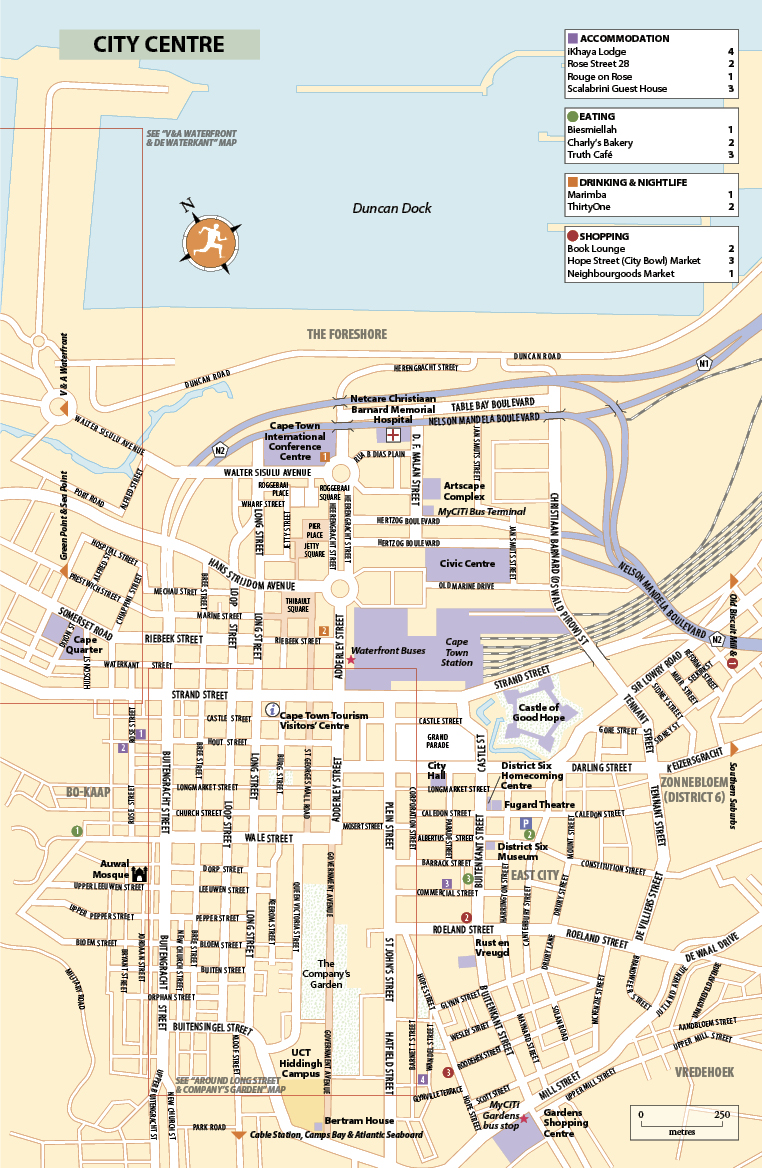

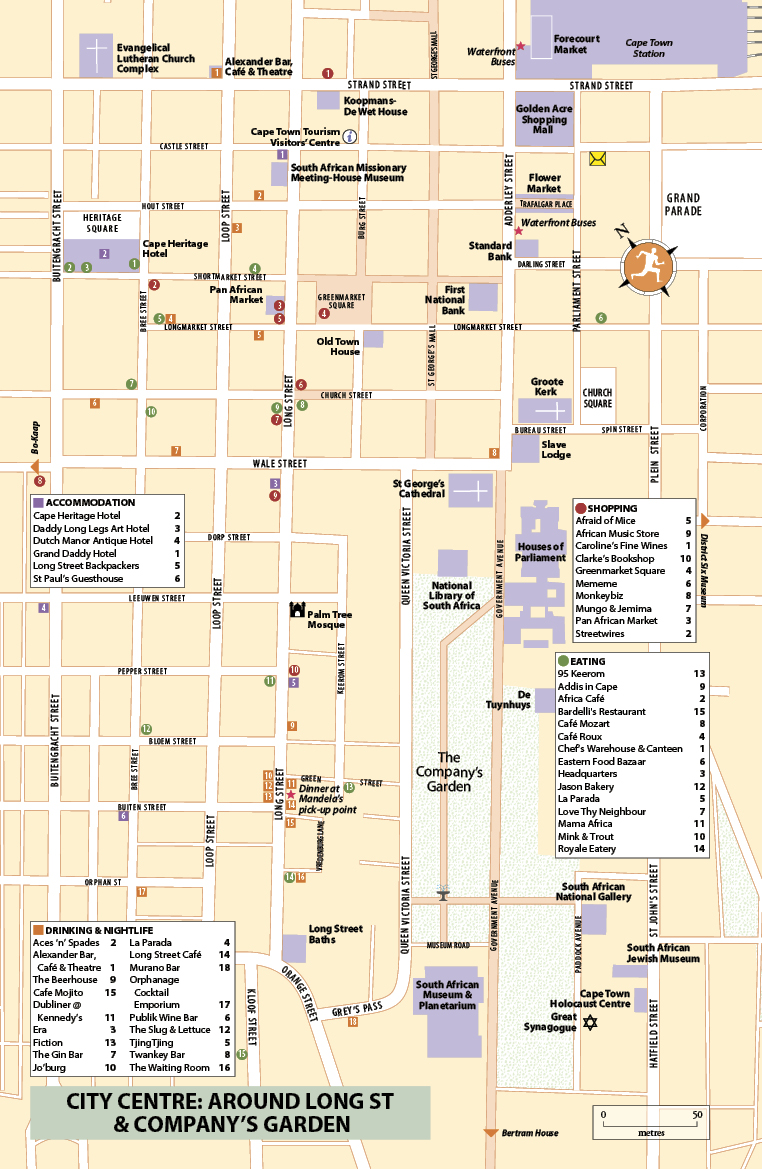

South Africa’s oldest urban region pulses with the cultural fusion that has been Cape Town’s hallmark since its founding in 1652. The city centre is spectacularly situated, dominated by Table Mountain to the south and the pounding Atlantic to the north. Strand Street marks the edge of the city’s original beachfront (though you’d never guess it today), with the Lower City Centre to the northeast and Upper City Centre to the southwest. Another useful orientation axis is Adderley Street, which connects the main train station with St George’s Cathedral, the landmark Anglican cathedral at the northeastern entrance to the Company’s Garden. These venerated gardens are Cape Town’s symbolic heart, surrounded by the Houses of Parliament, museums, historic buildings, archives and De Tuynhuys (the office of the president).

North of St George’s is the closest South Africa gets to a European quarter – a tight network of streets with cafés, buskers, craft markets, street stalls and antique shops congregating around the pedestrianized St George’s Mall and Greenmarket Square.

Parallel to St George’s Mall, Long Street, the quintessential Cape Town thoroughfare, is lined with Victorian buildings containing pubs, bistros, nightclubs, backpacker lodges, bookshops and antique dealers. Climb to the colonial piles’ wrought-iron balconies for glimpses of Table Mountain and the ocean. Two blocks further west is Bree Street, which has established itself as a quieter and more discerning alternative to Long Street, with an interesting choice of boutique stores and bars. The Bo-Kaap, or Muslim quarter, a few blocks further northwest across Buitengracht, is a piquant contrast with its colourful houses, minarets, spice shops and stalls selling curried snacks.

Southeast of Adderley Street lie three historically loaded sites. The Castle of Good Hope is the country’s oldest building and an indelible symbol of Europe’s colonization of South Africa – a process whose death knell was struck from nearby City Hall, the attractive Edwardian building from which Nelson Mandela made his first speech after being released. South of the castle lie the poignant remains of District Six, the coloured inner-city suburb that was razed in the name of apartheid.

getting around: THE CITY CENTRE

By bus

MyCiTi ![]() 0800 65 64 63,

0800 65 64 63, ![]() myciti.org.za. Useful and safe, the MyCiTi bus network has stations and stops on several routes around the City Bowl and beyond. Buses run through the city centre from Gardens and the neighbouring suburbs, on the south side of the City Bowl, to stops including Long St, the castle, the Civic Centre and Adderley (for the main train station), continuing to the Cape Town International Convention Centre and the Waterfront. The Civic Centre and Adderley are central transport hubs, where you can get buses to all areas served by MyCiTi buses. A number of buses run through the city centre, bringing you within a short walk of most of the central attractions. Bus #106 to Camps Bay goes up Adderley St, Long St and Kloof Nek; the #101 to Gardens goes via Long St, while the #109 to Hout Bay crosses the centre at right angles to this, along Riebeek St and onto the Atlantic suburbs.

myciti.org.za. Useful and safe, the MyCiTi bus network has stations and stops on several routes around the City Bowl and beyond. Buses run through the city centre from Gardens and the neighbouring suburbs, on the south side of the City Bowl, to stops including Long St, the castle, the Civic Centre and Adderley (for the main train station), continuing to the Cape Town International Convention Centre and the Waterfront. The Civic Centre and Adderley are central transport hubs, where you can get buses to all areas served by MyCiTi buses. A number of buses run through the city centre, bringing you within a short walk of most of the central attractions. Bus #106 to Camps Bay goes up Adderley St, Long St and Kloof Nek; the #101 to Gardens goes via Long St, while the #109 to Hout Bay crosses the centre at right angles to this, along Riebeek St and onto the Atlantic suburbs.

City Sightseeing ![]() 0861 733 287,

0861 733 287, ![]() citysightseeing.co.za. Hop-on, hop-off sightseeing buses stop at the major attractions in the city centre.

citysightseeing.co.za. Hop-on, hop-off sightseeing buses stop at the major attractions in the city centre.

Upper City Centre

Once the place to shop in Cape Town, Adderley Street, lined with handsome buildings spanning several centuries, is still worth a stroll today. Its attractive streetscape has been blemished by a series of large 1960s shopping centres, but just minutes away from these crowded malls, among the streets and alleys around Greenmarket Square, the area takes on a more human element and is full of historic texture.

Low-walled channels, ditches, bridges and sluices once ran through Cape Town, earning it the name Little Amsterdam. During the nineteenth century, the canals were buried underground, and, in 1850, Heerengracht (Gentlemen’s Canal), formerly a waterway that ran from the Company’s Garden down to the sea, was renamed Adderley Street. There’s little evidence of the canals today, except in name – the lower end of Adderley is still called Heerengracht and a parallel street to the west is called Buitengracht (Outer Canal). The destruction of old Cape Town continued well into the twentieth century, with the razing of many of the older buildings.

Trafalgar Place Flower Market

Trafalgar Pl • Mon–Sat 9am–4pm

Local coloured people, originally from Constantia and more recently from the Bo-Kaap, have run this flower market for well over a century. Look out for Cape classics such as proteas, petunias and daisies at the market, which spills onto Adderley Street.

Standard and First National banks

15 & 82 Adderley St • First National Bank: Mon–Fri 9am–4pm, Sat 8.30am–noon • ![]() standardbank.co.za,

standardbank.co.za, ![]() fnb.co.za

fnb.co.za

Two grandiose bank buildings, one still a major working bank, stand on opposite sides of Adderley Street: the Standard Bank is fronted by Corinthian columns and covered with a tall dome; and the First National Bank, completed in 1913, is the last South African building designed by Sir Herbert Baker. If you pop into the latter for a quick look, still in place inside the banking hall you’ll find a solid-timber circular writing desk with the original inkwells, resembling an altar.

The language of colour

It’s striking just how un-African Cape Town looks and sounds. Halfway between East and West, this city drew its population from Africa, Asia and Europe, and traces of all three continents are found in the genes, language, culture, religion and cuisine of Cape Town’s coloured population.

Afrikaans (a close relative of Dutch) is the mother tongue of around forty percent of the city’s residents, mostly coloured people and Afrikaners. However, about thirty percent of Capetonians are born English speakers, and English punches well above its weight as the local lingua franca, which, in this multilingual society, virtually everyone can speak and understand.

The term “coloured” is contentious, but in South Africa it doesn’t have the same tainted connotations as in Britain and the US; it refers to South Africans of mixed race. Over forty percent of Capetonians are coloured people, with Asian, African and Khoikhoi ancestry – compared with around fifteen percent whites and the growing black African contingent of close to forty percent.

In the late nineteenth century, Afrikaans-speaking whites, fighting for an identity, sought to create a “racially pure” culture by driving a wedge between themselves and coloured Afrikaans speakers. They reinvented Afrikaans as a “white man’s language”, eradicating the supposed stigma of its coloured ties by substituting Dutch words for those with Asian or African roots. In 1925, the white dialect of Afrikaans became an official language alongside English, and the dialects spoken by coloured people were treated as inferior deviations from correct usage.

For Afrikaner nationalists this wasn’t enough, and after the introduction of apartheid in 1948, they attempted to codify perceived racial differences. Under the Population Registration Act, all South Africans were classified as white, coloured or African. These classifications became fundamental to what kind of life you could expect. There are numerous cases of families in which one sibling was classified coloured with limited rights, and another white with the right to live in comfortable white areas, enjoy superior job opportunities and send their children to better schools and universities.

With the demise of apartheid, the make-up of residential areas is shifting – and so is the thinking on ethnic terminology. In Afrikaans, the term kleurling (coloured) is slowly being superseded by bruinmense (brown people). Far from rejecting the term “coloured” and its apartheid associations, most coloured people proudly embrace it, as a means of acknowledging their distinct culture, with its slave and Khoikhoi roots. Many middle class coloured people drop Afrikaans in favour of English, choosing a world language over one that was perceived under apartheid as the language of the white oppressor. However, the quavering coloured dialect of Afrikaans, which is distinct from the version spoken by Afrikaners, remains ubiquitous on the streets of Cape Town.

Groote Kerk

43 Adderley St • Mon–Fri 10am–2pm; services Sun 10am & 7pm • Free • ![]() grootekerk.org.za (Afrikaans only)

grootekerk.org.za (Afrikaans only)

The Groote Kerk (Great Church) was the first church erected in South Africa, shortly after the Dutch arrived in 1652, bringing their rigorous Protestant beliefs with them. The current church replaces an earlier structure, which had become too small for the swelling ranks of the Dutch Reformed congregation at the Cape. The building is essentially Classical, with Gothic and Egyptian elements, and was designed and built between 1836 and 1841 by Hermann Schutte, a German who became one of the Cape’s leading early nineteenth-century architects. The beautiful freestanding clock tower is a remnant of the original church.

The soaring space created by the vast vaulted ceiling and the magnificent pulpit, a masterpiece by sculptor Anton Anreith and carpenter Jan Jacob Graaff, are worth stepping inside for. The pulpit, supported on a pair of sculpted lions with gaping jaws, was carved by Anreith after his first proposal, featuring Faith, Hope and Charity, was rejected by the church council for being “too popish”.

The naming of Adderley Street

Although the Dutch used Robben Island as a political prison, in the 1800s the South African mainland only narrowly escaped becoming a second Australia, which at that time was a penal colony where British felons and enemies of the state could be dumped. In the 1840s, “respectable” Australians were lobbying for a ban on the transportation of criminals to the Antipodes, and the British authorities responded by trying to divert convicts to the Cape.

The British ship Neptune set sail from Bermuda for Cape Town in 1848, carrying 282 prisoners. There was outrage when news of its departure reached the Cape; five thousand citizens gathered on the Grand Parade to hear prominent liberals denounce the British government, an event depicted in The Great Meeting of the People at the Commercial Exchange by Johan Marthinus Carstens Schonegevel, which hangs in the Rust en Vreugd Museum. When the ship docked in September 1849, governor Sir Harry Smith forbade any criminal from landing; meanwhile, back in London, politician Charles Adderley successfully addressed the House of Commons in support of the Cape colonists. In February 1850, the Neptune set off for Tasmania with its full complement of convicts, and grateful Capetonians renamed the city’s main thoroughfare Adderley Street.

The Groote Kerk still has a keen family congregation, with a thundering organ and pealing bells. Across Parliament Street, slaves were once traded on Church Square, as the Slavery Memorial remembers, its eleven black granite blocks engraved with the names of slaves.

Slave Lodge

Cnr Adderley and Wale sts • Mon–Sat 10am–5pm • R30 • ![]() iziko.org.za/museums/slave-lodge

iziko.org.za/museums/slave-lodge

The Slave Lodge, which sits at the southern corner of Adderley Street, just as it veers northwest into Wale Street, was built in 1679 to house the human chattels of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) – the Cape’s largest slaveholder.

For nearly two centuries – more than half the city’s existence as an urban settlement – Cape Town’s economic and social structures rested on slavery (see box opposite). By the 1770s, almost a thousand slaves were held at the lodge. Under VOC administration, the lodge also became the Cape Colony’s main brothel, its doors thrown open for an hour each night. From 1810, following the British takeover, the lodge variously housed government offices, the Supreme Court, the country’s first library and first post office, finally becoming a museum in 1966.

The Slave Lodge has redefined itself as a museum of slavery as well as human rights museum, with displays showing the family roots, ancestry and peopling of South Africa, and changing exhibitions which have covered the likes of Steve Biko and slavery in Brazil. Taking an audio headset allows you to follow the footsteps of German salt trader Otto Menzl as he is taken on a tour of the lodge in the 1700s, giving a good idea of the miserable conditions at the time. Of note is a scale model of the Meermin, one of several ships sent to Madagascar in the eighteenth century to bring men, women and children into slavery in the Cape. Another memorable stop is an alcove, lit by a column of light, where the names of slaves are marked on rings that resemble tree trunks, symbolic of the Slave Tree under which slaves were bought and sold. Though the actual Slave Tree is long gone, the spot is marked by a simple and inconspicuous plinth behind Slave Lodge, on the traffic island in Spin Street.

Long Street

Parallel to Adderley Street, buzzing one-way Long Street is one of Cape Town’s most diverse thoroughfares, and is best known as the city’s main nightlife strip. When Muslims first settled here some three hundred years ago, Long Street marked Cape Town’s boundary; by the 1960s, it had become a sleazy alley of drinking holes and brothels. The libation and raucousness are certainly still here, but with a whiff of gentrification and a wad of fast-food joints, and the street deserves exploration roughly from the Greenmarket Square area upwards.

Mosques still coexist alongside bars, while antique dealers, craft shops, bookshops and cafés occupy the attractive Victorian buildings with New Orleans-style wrought-iron balconies. The street is packed with backpacker hostels and a few hotels, though the proliferation of nightclubs means it can be noisy into the early hours. Until the area quietens down for the night, it’s relatively safe to pub or club crawl on foot, with pickpockets being the main danger, and you’ll always find taxis and street food.

Long Street Baths

Cnr Long and Orange sts • Daily 7am–7pm, women only Tues 10am–4pm • Pools R22, Turkish baths R60 per hour • ![]() 021 422 0100

021 422 0100

The Long Street Baths is an unpretentious and relaxing historic Cape Town institution, established in 1908 in an Edwardian building at the top of Long Street. Though shabby, behind its Art Nouveau facade are a 25m heated pool and a children’s pool, overlooked by murals of city life. Call ahead to use the Turkish baths, which have a sauna and steam room with massages available.

Palm Tree Mosque

185 Long St • Closed to the public

The diminutive Palm Tree Mosque was named after two palm trees that stood outside; the fronds of one still caress the building’s upper storey. South Africa’s second-oldest mosque, it is also the street’s only surviving eighteenth-century building, erected in 1780 by Carel Lodewijk Schot as a private dwelling. The house was bought in 1807 by Frans van Bengal, a member of the local Muslim community, and a freed slave, Jan van Boughies, who became its imam and turned the upper storey into a mosque, the lower into his living quarters.

Slavery at the Cape

Slavery was officially abolished at the Cape in 1834, but its legacy lives on in South Africa. The country’s coloured inhabitants, who make up over forty percent of Cape Town’s population, are largely descendants of slaves, political prisoners from the East Indies and indigenous Khoisan people. The darkest elements of apartheid recalled the days of slavery, as did labour practices such as the “dop system”, in which workers on wine farms were partially paid in rations of cheap wine. Even today, domestic service, which is widespread throughout South Africa, can be traced back to colonialism and slavery.

By the end of the eighteenth century, the almost 26,000-strong slave population of the Cape exceeded that of the free burghers. Despite the profound impact this had on the development of social relations in South Africa, slavery remained one of the most neglected topics of the country’s history, until the publication in the 1980s of a number of studies on slavery. There’s still reluctance on the part of most coloured people to acknowledge their slave origins. Common coloured surnames such as January and September generally indicate these roots, as they refer to the month the slave was acquired.

Few if any slaves were captured at the Cape for export, making the colony unique in the African trade. Paradoxically, while people were being captured elsewhere on the continent for export to the Americas, the Cape administration, forbidden by the VOC from enslaving the local indigenous population, had to look further afield. Of the 63,000 slaves imported to the Cape, most came from East Africa, Madagascar, India and Indonesia, representing one of the broadest cultural mixes of any slave society. This diversity initially worked against the establishment of a unified group identity, but eventually a Creolized culture emerged which, among other things, played a major role in the development of the Afrikaans language.

Pan African Market

76 Long St • Summer Mon–Fri 8.30am–5.30pm, Sat 9am–3.30pm; winter Mon–Fri 9am–5pm, Sat 9am–3pm • ![]() 021 426 4478

021 426 4478

Behind the yellow facade of the Pan African Market, one of Cape Town’s most enjoyable places to buy African crafts, is a three-storey warren of passageways and rooms bursting at the hinges with traders selling art and artefacts from all over the continent. The colourful mishmash includes terrific masks from West Africa, baskets from Zimbabwe, brass leopards from Benin and contemporary South African art textiles, as well as CDs and musical instruments. This is also the place to get kitted out in African garb – in-house seamstresses are at the ready.

South African Missionary Meeting-House Museum

40 Long St • Mon–Fri 8.30am–4pm • Free • ![]() 021 423 6755

021 423 6755

The South African Missionary Meeting-House Museum was the first missionary church in the country, where slaves were taught literacy and instructed in Christianity. This exceptional building, completed in 1804 by the South African Missionary Society, boasts one of the most beautiful frontages in Cape Town. Dominated by large windows, the facade is broken into three bays by four slender Corinthian pilasters surmounted by a gabled pediment. Inside, an impressive Neoclassical timber pulpit perches on a pair of columns, and frames an inlaid image of an angel in flight.

Heritage Square

From Long Street, head northwest down Shortmarket Street to Heritage Square, one of the largest restoration projects ever undertaken in Cape Town. Saved from becoming a car park, the block of Cape Dutch, Georgian and Victorian buildings houses a cluster of restaurants and wine bars set around a tranquil courtyard, where South Africa’s oldest known (and still fruit-bearing) vine continues to flourish. The square is worth visiting for the architecture and a good glass of Cape wine under shady umbrellas. Adjoining it is the Cape Heritage Hotel, one of the city centre’s most stylish historic hotels.

Bo-Kaap

Minutes from Parliament, on the slopes of Signal Hill, is the Bo-Kaap, one of Cape Town’s oldest and most fascinating residential areas. Its streets are characterized by brightly coloured nineteenth-century Cape Dutch and Georgian terrace houses – an image familiar from tour brochures – concealing a network of alleyways which are the arteries of its Muslim community. The Bo-Kaap harbours its own strong identity, made all the more unique by the destruction of District Six, with which it had much in common.

Bo-Kaap residents descend from slaves, dissidents and Islamic leaders brought over by the Dutch in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. They were known collectively as “Cape Malays”, a term still heard today, even though it’s a misnomer: as well as the Dutch colonies in present-day Malaysia and Indonesia, many came from Africa, India, Madagascar and Sri Lanka.

SLAVERY AND SALVATION

The South African Missionary Society was founded in 1799 by the Reverend Vos, who was alarmed that many slaveholders neglected the religious education of their “property”. The owners believed that once their slaves were baptized, their emancipation became obligatory – a misunderstanding of the law, which merely stated that Christian slaves couldn’t be sold. Vos, himself a slaveholder, saw proselytization to those in bondage as a Christian duty, and even successfully campaigned to end the prohibition against selling Christian slaves, which he believed was “a great obstacle in this country to the progress of Christianity”, because it encouraged owners to avoid baptizing their human possessions.

Bo-Kaap Museum

71 Wale St • Mon–Sat 10am–5pm • R20 • ![]() 021 481 3938,

021 481 3938, ![]() iziko.org.za/museums/bo-kaap-museum

iziko.org.za/museums/bo-kaap-museum

If you’re exploring the Bo-Kaap without a guide, a good place to start is the Bo-Kaap Museum. Occupying one of the neighbourhood’s oldest houses, the museum explains the local culture and illustrates the lifestyle of a nineteenth-century Muslim family. It also explores the local form of Islam, which has its own unique traditions and two dozen kramats (shrines) dotted about the peninsula.

exploring the Bo-kaap

The easiest way to get to the Bo-Kaap is by foot along Wale Street, which trails up from the south end of Adderley Street and across Buitengracht, to become the neighbourhood’s main drag. The architectural charm of the colourful, protected historic core climbing Signal Hill, roughly bordered by Dorp, Strand and Buitengracht streets, is one of Cape Town’s great surprises.

While there is still a solid Muslim community in the Bo-Kaap, it has been joined by new residents who like the area’s aesthetics and slight edginess, not to mention its central location and stunning Table Mountain views. As such, in recent years a smattering of design boutiques, coffee shops and B&Bs has sprung up here.

The best way to explore the Bo-Kaap is by joining one of the walking tours that take in the Bo-Kaap Museum and explore the district, with Cape Malay snacks or lunch along the way. A number of these combine walking with a cooking tour.

The Bo-Kaap Cooking Tour (meet at Bo-Kaap Museum; R500, including three-course lunch; ![]() 074 130 8124,

074 130 8124, ![]() bokaapcookingtour.co.za) offers a two-hour tour including a forty-minute walk and lunch in culinary guru Zainie’s home. From Tuesday to Thursday, the same outfit offers a three-hour tour (R750) featuring an interactive cooking lesson, in which Zainie teaches you to mix masala and produce a Cape Malay meal. You need to book at least a day in advance, but for the delicious food, the forward planning is definitely worth it.

bokaapcookingtour.co.za) offers a two-hour tour including a forty-minute walk and lunch in culinary guru Zainie’s home. From Tuesday to Thursday, the same outfit offers a three-hour tour (R750) featuring an interactive cooking lesson, in which Zainie teaches you to mix masala and produce a Cape Malay meal. You need to book at least a day in advance, but for the delicious food, the forward planning is definitely worth it.

Cooking With Love (109 Wale St; ![]() 072 483 4040,

072 483 4040, ![]() facebook.com/Faldela1), run by the charismatic Faldela Tolker, Lekka Kombuis (

facebook.com/Faldela1), run by the charismatic Faldela Tolker, Lekka Kombuis (![]() 079 957 0226,

079 957 0226, ![]() lekkakombuis.co.za) and Andulela (

lekkakombuis.co.za) and Andulela (![]() 021 790 2592,

021 790 2592, ![]() andulela.com) also offer Cape Malay cooking “safaris”.

andulela.com) also offer Cape Malay cooking “safaris”.

Auwal Mosque

39 Dorp St • Closed to the public

The Auwal Mosque was South Africa’s first official mosque, founded in 1797 by the highly influential Imam Abdullah ibn Qadi Abd al-Salam (commonly known as Tuan Guru or Master Teacher), a Moluccan prince and Muslim activist who was exiled to Robben Island in 1780 for opposing Dutch rule in the Indies. While on the island, he transcribed the Koran from memory and wrote several important Islamic commentaries, which provided a basis for the religion at the Cape for a century. On being released in 1792, he began offering religious instruction from his house in Dorp Street, before founding the Auwal nearby.

Although it is closed to the public, you may be able to access the Auwal on a Cape Malay cooking safari (see box above). It’s one of ten mosques serving the Bo-Kaap’s Muslim residents, their minarets punctuating the quarter’s skyline.

Greenmarket Square

Cnr Shortmarket and Burg sts

Turning east from Long Street into Shortmarket or Longmarket street, you’ll skim the edge of Greenmarket Square, its cobblestones fringed by grand Art Deco buildings and coffee shops. As its name implies, the square started as a vegetable market, and, after many ignominious years as a car park, it is now home to a flea market where you can buy crafts, jewellery and hippie clobber. This is one of the best places in Cape Town to buy from Congolese and Zimbabwean traders, who sell masks and malachite carvings that make great souvenirs.

Michaelis Collection

Old Town House, Greenmarket Square • Mon–Sat 10am–5pm • R20 • ![]() 021 481 3933,

021 481 3933, ![]() iziko.org.za

iziko.org.za

At the southern corner of Greenmarket Square are the solid limewashed walls and small shuttered windows of the Old Town House, entered from Longmarket Street. Built in 1755, this beautiful example of Cape Rococo architecture, with a fine interior, has seen duty as a guardhouse, a police station and Cape Town’s city hall. Today it houses the Michaelis Collection of minor but interesting seventeenth-century Dutch and Flemish paintings. At the time of writing it was closed for maintenance.

The seventeenth century was one of great prosperity for the Netherlands and has been referred to as the Dutch “Golden Age”, during which the nation threw off the yoke of its Spanish colonizers and sailed forth to establish colonies of its own in the East Indies and, of course, at the Cape. The wealth that trade brought to the Netherlands stimulated the development of the arts, and the paintings of the era reflect the values and experience of Dutch Calvinists. A notable example is Frans Hals’ Portrait of a Woman, hanging in the upstairs gallery. Executed in shades of brown, relieved only by the merest hint of red, it reflects the Calvinist aversion to ostentation. The sitter for the picture, completed in 1644, would have been a contemporary of the settlers who arrived at the Cape some eight years later. Less dour and showing off the wealth of a middle-class family is the beautiful Couple with Two Children in a Park, painted by Dirck van Santvoort in the late 1630s. The artist displays a remarkable facility for portraying sensuous fabrics which glow with reflected light; you can almost feel the texture of the lace trimming.

Other paintings, most of them quite sombre, depict mythological scenes, church interiors, still lifes, landscapes and seascapes; the latter are very close to the seventeenth-century Dutch heart, often illustrating Dutch East India Company vessels or the drama of rough seas encountered by trade ships. A tiny print room on the ground floor has a small selection of works by Daumier, Gillray, and Cruikshank, and others.

Small visiting exhibitions also find space here, and there are regular evening chamber-music concerts and cultural lectures; the website lists forthcoming events.

St George’s Mall

Coffee shops, snack bars, street traders and buskers make the pedestrianized thoroughfare of St George’s Mall a pleasant route between the train station and the Company’s Garden.

St George’s Cathedral

5 Wale St • Mon–Fri 9am–4.30pm, Sat 9am–noon; services Mon–Fri 7.15am & 1.15pm, also Tues–Thurs 8am & 4pm, Wed 10am, Sat 8am, Sun 7am, 8am, 9.30am & 6pm • Free • ![]() 021 424 7360,

021 424 7360, ![]() sgcathedral.co.za

sgcathedral.co.za

St George’s Cathedral, at the southern end of St George’s Mall, is as interesting for its history as for its Herbert Baker Victorian-Gothic design. There are daily services, as well as the main Sunday Mass at 9.30am, and the cathedral hosts good classical, jazz and choral concerts (check website for details). The most famous former archbishop of Cape Town is undoubtedly Nobel Peace Prize-winner Desmond Tutu, who hammered on the cathedral’s doors symbolically on September 7, 1986, when he was enthroned as South Africa’s first black archbishop. Three years later, he heralded the last days of apartheid by leading thirty thousand people from St George’s to the City Hall, where he coined his now famous slogan for the new order: “We are the rainbow people!”, and told the crowd, “We are the new people of South Africa!” In 2014, at the cathedral, Archbishop Tutu launched a book on a topic close to his heart, The Book of Forgiving, with his daughter, Reverend Mpho Tutu.

Church Street

Church Street and its surrounding area abound with antique dealers selling bric-a-brac and Africana. In the pleasant pedestrianized section, between Long and Burg streets, art galleries mingle with the smell of coffee, and you can rest your legs sitting at an outdoor table at Café Mozart.

Government Avenue and around

A stroll down the oak-lined, pedestrianized Government Avenue makes for one of the most serene walks in central Cape Town. The leafy boulevard runs past the rear of Parliament through the Company’s Garden, and its benches host everyone from office workers to bergies (homeless inhabitants of Cape Town).

Houses of Parliament

Public entrance 120 Plein St • Tours hourly tours Mon–Fri 9am–4pm, 1hr • Free • Book ahead and bring ID • ![]() 021 403 2266,

021 403 2266, ![]() www.parliament.gov.za • Debating sessions Tues, Wed & Thurs afternoons, also occasionally Fri mornings • Free • Book at least a day in advance on

www.parliament.gov.za • Debating sessions Tues, Wed & Thurs afternoons, also occasionally Fri mornings • Free • Book at least a day in advance on ![]() 021 403 8219 or

021 403 8219 or ![]() mtsheole@parliament.gov.za

mtsheole@parliament.gov.za

South Africa’s Houses of Parliament, east of the north end of Government Avenue, are a complex of interlinking buildings, with labyrinthine corridors connecting hundreds of offices, debating chambers and miscellaneous other rooms. Many are relics of the 1980s reformist phase of apartheid, when, in the interests of racial segregation, three distinct legislative complexes catered to people of different “race”.

The original wing, completed in 1885, is an imposing Victorian Neoclassical building which first served as the legislative assembly of the Cape Colony. After the Boer republics and British colonies amalgamated in 1910, it became the parliament of the Union of South Africa. This is the old parliament, where over seven decades of repressive legislation, including apartheid laws, were passed. It’s also where 1960s prime minister Hendrik Verwoerd, the arch-theorist of apartheid, was stabbed to death by unstable parliamentary messenger Dimitri Tsafendas. The assassin reputedly claimed that he was following the orders of a tapeworm in his stomach, although police may have concocted this story to detract attention from his crime’s political motivation. Due to his mental state, Tsafendas escaped the gallows to outlive apartheid – albeit in an institution.

Verwoerd’s portrait, depicting him as a man of vision and gravitas, used to hang over the main entrance to the dining room. In 1996 it was removed “for cleaning”, along with paintings of generations of white parliamentarians, and never returned.

The new chamber was built in 1983 as part of the Tricameral Parliament, P.W. Botha’s attempt to avert majority rule by trying to co-opt Indians and coloureds – but in their own separate debating chambers. The “tricameral” chamber, where the three non-African “races” on occasions met together, is now the National Assembly, where you can watch sessions of parliament. One-hour tours take in the old and new debating chambers, the library and museum. You can get free day-tickets to debating sessions in the chambers of the National Assembly or National Council of Provinces (see above).

National Library of South Africa

5 Queen Victoria St • Mon–Fri 8am–6pm • Free • ![]() 021 424 6320,

021 424 6320, ![]() nlsa.ac.za

nlsa.ac.za

If you head south from the top of Government Avenue, you’ll soon come across the National Library of South Africa on your right. The building houses one of the country’s best collections of antiquarian historical and natural history books, covering southern Africa. It opened in 1822 as one of the world’s first free libraries.

Company’s Garden

19 Queen Victoria St • Daily: March–Nov 7am–9pm; Dec–Feb 7.30am–8.30pm • Free • ![]() 021 426 1357

021 426 1357

The Company’s Garden, which stretches from the National Library of South Africa down to the South African Museum, was the raison d’être for the Dutch settlement at the Cape. Established in 1652 to supply fresh greens to Dutch East India Company (VOC) ships travelling between the Netherlands and the East, the gardens were initially worked by imported slave labour. This proved too expensive, as the slaves had to be shipped in, fed and housed, so the Company opted for outsourcing: it phased out farming and granted the land to free burghers, from whom it bought fresh produce.

At the end of the seventeenth century, the gardens were turned over to botanical horticulture for Cape Town’s growing colonial elite. Ponds, lawns, landscaping and a crisscross web of oak-shaded walkways were introduced. It was during a stroll in these gardens that Cecil Rhodes (a statue of whom you’ll find here) first plotted the invasion of Matabeleland and Mashonaland (which together became Rhodesia and subsequently Zimbabwe). He also introduced an army of small, furry colonizers to the gardens – North American grey squirrels.

Today, the gardens are full of local plants, the result of long-standing European interest in Cape botany; experts have been sailing out since the seventeenth century to classify and name specimens. In recent years, the vegetable patches have been revived to evoke the agricultural diversity and splendour of the VOC era, when Government Avenue was lined with citrus trees to supply the scurvy-ridden sailors. The garden-cum-park is a pleasant place to meander, with a good outdoor café situated under massive trees.

De Tuynhuys

Government Ave • Not open to the public

Peer through an iron gate to see the grand facade and tended flowerbeds of De Tuynhuys, the office (but not residence) of the president. In 1992, President F.W. de Klerk announced outside this beautiful eighteenth-century building that South Africa had “closed the book on apartheid”.

Under the governorship of Lord Charles Somerset (1814–26), an official process of Anglicization at the Cape included his private obsession with architecture, which saw the demolition of the two Dutch wings of De Tuynhuys in Government Avenue. Imposing contemporary English taste, Somerset reinvented the entire garden frontage with a Colonial Regency facade, characterized by a veranda sheltering under an elegantly curving canopy, supported on slender iron columns.

South African National Gallery

Access via Paddock Ave, Company’s Garden • Daily 10am–5pm • R30 • ![]() iziko.org.za/museums/south-african-national-gallery

iziko.org.za/museums/south-african-national-gallery

The South African National Gallery is an essential port of call for anyone interested in the local art scene, with a small but excellent permanent collection of contemporary South African art. Displays change every three months, as the number of items far exceeds the capacity of the exhibition space. However, one of the pieces that regularly makes an appearance is Jane Alexander’s powerfully ghoulish plaster, bone and horn sculpture, The Butcher Boys (1985–86), created at the height of apartheid repression. It features three life-size figures with distorted faces that exude a chilling passivity, expressing the artist’s interest in the way violence is conveyed through the human figure. Alexander’s work is representative of “resistance art”, which exploded in the 1980s, broadly as a response to the growing repression of apartheid.

Paul Stopforth’s powerful graphite-and-wax triptych, The Interrogators (1979), featuring larger-than-life-size portraits of three notorious security policemen, is a work of monumental hyperrealism. Many other artists, unsurprisingly for a culturally diverse country, aren’t easily categorized; while works have tended to borrow from Western traditions, their themes and execution are uniquely South African. The late John Muafangelo employed biblical imagery in works such as The Pregnant Maria (undated), producing highly stylized, almost naive black-and-white linocuts; while in Challenges Facing the New South Africa (1990), Willie Bester used paint and found objects to depict the melting pot of the Cape Town squatter camps.

Since the 1990s, and especially in the post-apartheid period, the gallery has engaged in a process of redefining what constitutes contemporary indigenous art and has embarked on an acquisitions policy that “acknowledges and celebrates the expressive cultures of the African continent, particularly its southern regions”. Material that would previously have been treated as ethnographic, such as a major bead collection as well as carvings and craft objects, is now finding a place alongside oil paintings and sculptures.

The permanent collection also includes minor works by British artists, including George Romney, Thomas Gainsborough, Joshua Reynolds and some Pre-Raphaelites.

South African Jewish Museum

88 Hatfield St • Mon–Thurs & Sun 10am–5pm, Fri 10am–2pm • R60 • Bring ID • ![]() 021 465 1546,

021 465 1546, ![]() sajewishmuseum.org.za

sajewishmuseum.org.za

The South African Jewish Museum is partially housed in South Africa’s first synagogue, built in 1863. One of Cape Town’s most ambitious permanent exhibitions, it tells the story of the South African Jewish community from its beginnings, over 150 years ago, to the present. Starting in the Old Synagogue, visitors cross, via a gangplank, to the upper level of a two-storey building, symbolically re-enacting the arrival by boat of the first Jewish immigrants at Table Bay harbour in the 1840s. Multimedia interactive displays, models and artefacts explore Judaism in South Africa, drawing parallels between the religion and the ritual practices and beliefs of South Africa’s other communities. The basement level houses a walk-through reconstruction of a Lithuanian shtetl or village (most South African Jews have their nineteenth-century roots in Lithuania). The museum complex also has a restaurant, shop and noteworthy collection of ivory, staghorn and wood Japanese Netsuke figures. During the time of the Samurai, the affluent Japanese merchant classes used these miniature carvings to hang containers from their kimonos.

Cape Town Holocaust Centre

88 Hatfield St • Mon–Thurs & Sun 10am–5pm, Fri 10am–2pm • Free • Bring ID • ![]() 021 462 5553,

021 462 5553, ![]() ctholocaust.co.za

ctholocaust.co.za

Opened in 1999, the Cape Town Holocaust Centre, Africa’s first centre of its kind, features one of the city’s most moving and brilliantly constructed displays. The Holocaust Exhibition resonates sharply in a country that endured half a century of systematic racial oppression – a connection that the exhibition makes explicitly.

Exhibits trace the history of anti-Semitism in Europe, culminating with the Nazis’Final Solution; they also look at South Africa’s Greyshirts, who were motivated by Nazi propaganda during the 1930s and were later absorbed into the National Party. A twenty-minute video tells the story of the Holocaust survivors who settled in Cape Town.

Great Synagogue

88 Hatfield St • Mon–Thurs & Sun 10am–4pm • Free • Bring ID • ![]() 021 465 1405,

021 465 1405, ![]() gardensshul.org

gardensshul.org

The Great Synagogue or Gardens Shul is one of Cape Town’s outstanding religious buildings. Designed by the Scottish architects Parker & Forsyth and completed in 1905, it features an impressive dome and two soaring towers in the style of Central European Baroque churches. Guides can show you (for free) around the elegant neo-Egyptian interior with its carved teak pulpit, gold-leaf friezes and stained-glass windows.

South African Museum

25 Queen Victoria St; accessed from Museum Rd • Daily 10am–5pm • Adults R30, children 6–18 R15 • ![]() iziko.org.za/museums/south-african-museum

iziko.org.za/museums/south-african-museum

The nation’s premier museum of natural history and human sciences, the South African Museum is notable for its ethnographic galleries, which contain some good displays on the traditional arts and crafts of several African groups. There are also some exceptional examples of rock art (entire chunks of caves are in the display cases), as well as casts of the stone birds found at the archaeological site of Great Zimbabwe, in southeastern Zimbabwe.

Upstairs, the natural history galleries display mounted mammals, dioramas of prehistoric Karoo reptiles and Table Mountain flora and fauna. The highlight is the four-storey “whale well”, a hanging collection of beautiful whale skeletons, including a 20.5m blue whale skeleton, accompanied by recordings of the eerie strains of their song.

from top the bo-kaap; street vendors on long street

Planetarium

25 Queen Victoria St; accessed from Museum Rd • Shows daily; closed first Mon of every month • R40 • ![]() iziko.org.za/museums/planetarium

iziko.org.za/museums/planetarium

Housed in the South African Museum building is the Planetarium, in which you can see the constellations of the southern hemisphere, with an informed commentary. The changing programme of daily shows covers topics such as San sky myths, with some geared towards children and others to teenagers and adults, and you can buy a monthly chart of the current night sky.

Shows generally take place hourly from noon to 3pm, and at 7pm and 8pm, but times change during school holidays. Check the website for schedules.

Bertram House

University of Cape Town, Hiddingh Campus, accessed from Orange St • Daily 10am–5pm • Donation • ![]() iziko.org.za/museums/bertram-house

iziko.org.za/museums/bertram-house

At the southernmost end of Government Avenue, you’ll pass Bertram House, whose beautiful two-storey brick facade looks out across a fragrant herb garden. The museum is significant as Cape Town’s only surviving brick, Georgian-style house, and displays typical furniture and objects of a well-to-do colonial British family in the first half of the nineteenth century.

The house was built in 1839 by John Barker, a Yorkshire attorney who came to the Cape in 1823 and named the building in memory of his late wife, Ann Bertram Findlay. The reception rooms are decorated in the Regency style, while the porcelain is predominantly nineteenth-century English, although there are also some very fine Chinese pieces.

Rust en Vreugd

78 Buitenkant St • Mon–Fri 10am–5pm • R20 • ![]() iziko.org.za/museums/rust-en-vreugd

iziko.org.za/museums/rust-en-vreugd

The most beautiful of Cape Town’s house museums, Rust en Vreugd was built in 1778 for Willem Cornelis Boers, the colony’s Fiscal (a powerful position akin to the police chief, public prosecutor and collector of taxes rolled into one), who was forced to resign in the 1780s following allegations of wheeler-dealing and extortion. Under the British occupation, it was the residence of Lord Charles Somerset during his governorship (1814–26).

The house was once surrounded by countryside, but now stands along a congested route that brushes past the edge of the central business district. Designed by architect Louis Michel Thibault and sculptor Anton Anreith, the two-storey facade features a pair of stacked balconies, the lower one forming a stunning portico fronted by four Corinthian columns carved from teak. The front door, framed by teak pilasters, is an impressive work of art, rated by architectural historian De Bosdari as “certainly the finest door at the Cape”. Above the door, the fanlight is executed in elaborate Baroque style.

Inside, the William Fehr Collection of artworks on paper occupies two ground-floor rooms and includes illustrations by important documentarists such as Thomas Baines, who is represented by hand-coloured lithographs and a series of watercolours recording a nineteenth-century expedition up Table Mountain. The work of Thomas Bowler, another prolific recorder of Cape scenes, is also on display here, with his striking landscape painting of Cape Point from the sea in 1864, which shows dolphins frolicking in the foreground.

The garden is a reconstruction of the original eighteenth-century semiformal one, laid out with herbaceous hedges, bay trees, gravel walkways, and a spacious lawn with a quaint gazebo.

Castle of Good Hope

Castle St • Daily 9am–4pm; tours Mon–Sat 11am, noon & 3pm; cannon firing & key ceremony Mon–Fri 10am & noon, Sat 11am & noon • R30 including optional tour, kids R15 • ![]() 021 787 1249,

021 787 1249, ![]() castleofgoodhope.co.za

castleofgoodhope.co.za

Despite its unprepossessing pentagonal exterior, South Africa’s oldest official building is one of the city’s most worthwhile historical sights. Built in 1666, the Castle of Good Hope still serves as a (significantly downscaled) military barracks site, and is considered the best-preserved example of a Dutch East India Company (VOC) fort. For a hundred and fifty years, this was the symbolic heart of the Cape administration, and a sense of self-importance lingers in its grand rooms and courtyards.

Finished in 1679, complete with the essentials of a moat and torture chamber, the castle replaced Van Riebeeck’s earlier mud-and-timber fort which stood on the site of the Grand Parade. The building was designed along seventeenth-century European principles of fortification, comprising strong bastions from which the outside walls could be protected by crossfire.

Moving boundaries

The original, seaward entrance had to be moved to its present, landward position because the spring tide sometimes came crashing in; a remarkable thought given how far aground the castle is now, thanks to land reclamation. The entrance gate displays the coat of arms of the United Netherlands and those of the six Dutch cities in which the VOC chambers were situated.

Still hanging from its original wooden beams in the tower above the entrance is the bell, cast in 1697 by Claude Fremy in Amsterdam; it was used variously as an alarm signal, which can be heard from 10km away, and as a summons to residents to receive pronouncements. On the left after you enter, you can see the castle’s original gate in the Castle Military Museum, which exhibits South African military uniforms and delves into the Anglo-Boer War (often referred to as the South African War).

From castle to prison

The castle was the main prison for the Cape Colony, and prisoners held here included indigenous Khoi people and slaves accused of transgressions against their owners. As punishment could only be administered once a confession was made, detainees were routinely questioned and tortured. The guided tour takes you to the dark, inconspicuous room where these acts took place, with the original iron chains, that were used to bind the prisoner, still firmly attached to the wall; as well as to the adjacent solitary-confinement room – the much feared Donker Gat (Dark Hole). In other prison cells and dungeons, you can still see the touching centuries-old poetry and graffiti painstakingly carved into the walls by prisoners.

The inner courtyard is home to the platform where families of slaves would stand as they were bought and sold. As no law existed to keep families together, a mother would watch her children being sold off individually to different farms and vineyards in the Western Cape.

The William Fehr Collection

Across the grassy courtyard from the entrance, De Kat Balcony is named after the adjoining kat (defensive cross wall in Dutch). The ornate balcony leads to interconnected rooms that were once the heart of VOC government at the Cape and which now house the bulk of the William Fehr Collection, one of the country’s most important exhibits of decorative arts. The contents, acquired from the 1920s onwards by businessman William Fehr, and sold and donated to the government, continue to be displayed informally, as he preferred. The galleries are filled with items that would have been found in middle-class Cape households from the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries, with some fine examples of elegantly simple Cape furniture from the eighteenth century.

Early colonial views of Table Bay appear in a number of paintings, including one by Aernout Smit showing the Castle in the seventeenth century, right on the shoreline. Among the antique oriental ceramics are a blue-and-white Japanese porcelain plate from around 1660, which displays the VOC monogram; and a beautiful polychrome plate from China, dating from around 1750 and depicting a fleet of Company ships in Table Bay – against the backdrop of a very oriental-looking Table Mountain.

Grand Parade to City Hall

The Grand Parade, just northwest of the Castle of Good Hope, is a large open area where the residents of District Six used to come to trade. On Wednesdays and Saturdays it still transforms itself into a market (9am–4pm), where there is an array of bargains on offer, from cheap clothes to spicy food.

The Grand Parade appeared on TV screens throughout the world on February 11, 1990, when over sixty thousand people gathered to hear Nelson Mandela make his first speech after being released from prison, from the balcony of the City Hall. It’s also where an interfaith prayer was made upon his death, on December 6, 2013. The City Hall is a grand Edwardian building dating to 1905, dressed in Bath stone and looking impressive against the backdrop of Table Mountain.

District Six

South of the Castle of Good Hope, in the shadow of Devil’s Peak, is a vacant lot shown on maps as the suburb of Zonnebloem. Before being demolished by the apartheid authorities, it was an inner-city neighbourhood known as District Six, an impoverished but lively community of fifty-five thousand predominantly coloured people. Once regarded as the soul of Cape Town, the district harboured a rich – and much mythologized – multicultural life in its narrow alleys and crowded tenements: along the cobbled streets, hawkers rubbed shoulders with prostitutes, gangsters, drunks and gamblers, while craftsmen plied their trade in small workshops. This was a fertile place of the South African imagination, inspiring novels, poems and jazz, often with more than a hint of nostalgia, anger and pain of displacement. A case in point are the musicals of David Kramer, which are often staged at the resident Fugard Theatre.

In 1966, the Group Areas Act declared District Six a white area and the bulldozers moved in, taking fifteen years to drive District Six’s presence from the skyline, leaving only the mosques and churches. The accompanying forced removals saw the coloured inhabitants moved to the Cape Flats. But, in the wake of the demolition gangs, international and domestic outcry was so great that the area was never developed, apart from a few residential projects on its fringes and the hefty Cape Technikon college. After years of negotiation, the original residents are moving back under a scheme to develop low-cost housing in the area.

District Six Museum

25A Buitenkant St • Mon–Sat 9am–4pm • Entry R30; tours R15 • ![]() 021 466 7200,

021 466 7200, ![]() districtsix.co.za

districtsix.co.za

Few places in Cape Town speak more eloquently of the effect of apartheid on the day-to-day lives of ordinary people than the compelling District Six Museum. On the northern boundary of District Six, the museum occupies the former Central Methodist Mission Church, which offered solidarity and ministry to the victims of forced removals right up to the 1980s, and became a venue for anti-apartheid gatherings. Today, it houses a series of fascinating displays including everyday household items and the tools of bygone local trades, such as hairdressing implements, as well as documentary photographs, evoking the lives of the individuals who once lived here. Occupying most of the floor is a huge map of District Six as it was, annotated by former residents, who describe their memories, reflections and incidents associated with places and buildings that no longer exist. There’s also a collection of original street signs, secretly retrieved at the time of demolition by the man entrusted with dumping them into Table Bay.

You can tour the museum with an ex-resident for an extra R15, and guided walks around the area can be organised. The coffee shop offers a variety of snacks, including traditional, syrupy koeksisters. The nearby District Six Homecoming Centre (15 Buitenkant St), a cultural centre in the old Sacks Futeran textile warehouse, hosts changing exhibitions on local subjects, as well as performances by musicians and poets.

from top left CITY HALL; TRAFALGAR PLACE FLOWER MARKET; CASTLE OF GOOD HOPE

Strand Street

A major artery from the N2 freeway to the central business district, Strand Street neatly separates the Upper from the Lower city centre. Between the mid-eighteenth and mid-nineteenth centuries, this was one of the most fashionable streets in Cape Town, due to its proximity to the shore – it used to run along the beachfront, but now lies about a kilometre south of it. Its former cachet is now only discernible from the handful of quietly elegant national monuments left standing amid the traffic.

Evangelical Lutheran Church

98 Strand St, at Buitengracht • Mon–Fri 10am–2pm • Free • ![]() 021 421 5854,

021 421 5854, ![]() lutheranchurch.org.za

lutheranchurch.org.za

This Lutheran church is South Africa’s oldest church in permanent service and forms part of the country’s oldest city block. German woodcarver Anton Anreith converted it in around 1780 from a warehouse, where services had taken place in secret for several years.

The establishment of a Lutheran church in Cape Town struck a significant blow against the extreme religious intolerance that pervaded under VOC rule. Before 1779 (when permission was granted for Lutherans to establish their own congregation), Protestantism was the only form of worship allowed, and the Dutch Reformed Church held an absolute monopoly over saving people’s souls. The Lutheran Church’s congregation was dominated by Germans, who at the time constituted 28 percent of the colony’s free burgher population.

The church’s facade has Classical details such as a broken pediment perforated by the clock tower, as well as Gothic features including arched windows. Inside, the magnificent pulpit, supported on two life-size Herculean figures, is one of Anreith’s masterpieces; the white swan perched on the canopy is a symbol of Lutheranism.

Koopmans-De Wet House

35 Strand St • Mon–Fri 10am–5pm • R20 • ![]() 021 481 3935,

021 481 3935, ![]() iziko.org.za/museums/koopmans-de-wet-house

iziko.org.za/museums/koopmans-de-wet-house

Sandwiched between two office blocks, the Koopmans-De Wet House is an outstanding eighteenth-century pedimented Neoclassical townhouse and museum, which exhibits a fine collection of antique furniture and rare porcelain.

The earliest sections of the house were built in 1701 by Reyner Smedinga, a well-to-do goldsmith who imported the building materials from Holland. After changing hands more than a dozen times over the following two centuries, the building eventually fell into the hands of Marie Koopmans-De Wet (1834–1906), a prominent figure on the Cape social and political circuit.

The house represents a fine synthesis of Dutch elements with the demands of local conditions: typically Dutch sash windows and large entrances combine with huge rooms, lofty ceilings and shuttered windows, all installed with high summer temperatures in mind. The lantern in the fanlight of the entrance was a common feature of Cape Town houses in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, its purpose to shine light onto the street and hinder slaves from gathering to plot.

Bree Street

Humming with design shops, boutiques, restaurants, cafés and bars, Bree Street has become the favourite haunt of hipsters, fashionistas and well-heeled Capetonians. The conversion of old buildings into new spaces enhances the lovely architecture, adding charm to equal Long Street’s Victorian edifices, and even the car-loving locals are enticed to wander the pavements. The upper end of Bree, roughly between Buitensingel Street and Heritage Square, is your best bet to get a feel for this vibrant strip.

Lower City Centre

In the mid-nineteenth century, the city’s middle classes viewed the Lower City Centre and its low-life activities with a mixture of alarm and excitement – a tension that remains today. Lower Long Street splits this area just inland from the docklands. To the east is the Foreshore, an ugly post-World War II wasteland of grey corporate architecture, among which is the Artscape Centre, Cape Town’s premier arts complex. The Foreshore is gradually being redeveloped, with a centrepiece in the successful Cape Town International Convention Centre (CTICC), linked by a canal and pedestrian routes with the Waterfront. Cape Town Station, at the junction of Adderley and Strand streets, is the city’s commuting nexus; it has its own bustling life of hooting and hollering taxi drivers, buskers and stallholders hawking cheap Chinese goods.

The Foreshore

The Foreshore is an area of reclaimed land northeast of Strand Street, stretching to the docks and northwest of Lower Long Street. The area was developed in the late 1940s in the spirit of modernism that was sweeping the world, with its penchant for large, highly planned urban spaces. It was intended to turn Cape Town’s harbour into a symbolic gateway to Africa; instead, all that emerged was a series of large concrete boxes surrounded by acres of windswept tarmac car parks.

In 2013, the construction of the FNB-branded Portside Tower gave Cape Town its tallest building (139m), in the heart of a small financial and legal district. It’s also the city’s greenest building: LED lighting and low-energy technology are used throughout, with ample bicycle racks and changing rooms, electric car chargers and parking for hybrid vehicles.

Another recent development is the fourteen-storey, R285 million office block, Roggebaai Place. However, the area’s street life pales in comparison with other parts of the city centre, and most visitors will prefer to spend their time elsewhere. The main attraction here is watching a performance at the dynamic Artscape Complex, while you may spot the glassy blue facade of the Foreshore’s latest construction triumph, the Netcare Christiaan Barnard Memorial Hospital, from the Nelson Mandela Boulevard flyover.

Artscape Complex

D.F. Malan St, just east of Heerengracht • Performance times vary; visit website for listings • ![]() 021 410 9800,

021 410 9800, ![]() artscape.co.za

artscape.co.za

The Artscape Complex, Cape Town’s monumental performance venue, includes a huge theatre, an opera house and the compact Arena Theatre, collectively offering the city’s liveliest calendar of drama, opera, comedy, dance and musicals. The concrete 1970s complex is the home of Cape Town Opera, which features the best of South Africa’s singers; Jazzart, the Western Cape’s longest-established contemporary dance company, going since 1973; and the century-old Cape Town Philharmonic Orchestra.

Netcare Christiaan Barnard Memorial Hospital

Cnr D.F. Malan St & Rua Bartholomeu Dias Plain • ![]() www.netcare.co.za

www.netcare.co.za

One of the latest additions to the Foreshore is the Netcare Christiaan Barnard Memorial Hospital, a 250-bed private hospital, which superseded the 35-year-old hospital of the same name on the corner of Bree and Longmarket streets. If you are in the area, pass through reception, where artworks and AV installations honour the life and work of Barnard, the pioneering surgeon who performed the world’s first successful heart transplant at Cape Town’s Groote Schuur Hospital in 1967.

Jetty Square

Between Jetty St & Pier Pl • ![]() capetownpartnership.co.za

capetownpartnership.co.za

Cape Town Partnership, the organisation driving the regeneration of the central city, has placed sculptures and installations in the Foreshore’s plazas, bringing beauty and humour to these urban spaces. A good example is Ralph Borland’s eerie shark sculptures in the small Jetty Square, reminders that the land here was reclaimed from the sea. The skeletal structures have infrared sensors in their noses, which make them swivel in accordance with the movements of passing pedestrians.