ACADEMIC AND SCHOLARLY REACTION

The final conclusions of the previous chapter, namely that a link existed between the Essenes of Qumran and an Egyptian pharaoh named Akhenaten, are, I believe, fully supported by the overwhelming weight of evidence that has been presented.

The final conclusions of the previous chapter, namely that a link existed between the Essenes of Qumran and an Egyptian pharaoh named Akhenaten, are, I believe, fully supported by the overwhelming weight of evidence that has been presented.

Since publication of The Copper Scroll Decoded in 1999, the main theory has been tested against a broad spectrum of academic and scholarly opinion, and in many instances response to the main thrust of the theory has been favourable and enthusiastic. This is especially true where the commentator has taken the time to study the work in some depth. Where there has been a negative response, it has been in the form of guarded scepticism, particularly as the theory presents a radically new view of religious evolution that strongly conflicts with enshrined orthodoxy. Two main factors have, I believe, inhibited any widespread acceptance of the central theory. Firstly, time constraints on individuals have not allowed them to undertake a detailed analysis. Secondly, few academics are in a position to evaluate the broad historical and archaeological scope of Israelite, Egyptian, and Mesopotamian religious culture from a multi-disciplinary standpoint. There tends to be quite sharp divisions in their areas of expertise. They are masters in their own field but rarely have much scientific or engineering training.

Most academics and scholars in the field of biblical research are knowledgeable linguists, historians, theologians, epigraphers, philologists, or archaeologists who increasingly specialise in a particular area of interest. Whilst they may draw on the expertise of computer and medical specialists, engineers, scientists, anthropologists and sociologists, there is virtually no one from these disciplines working in the field of biblical research.

For fifty years, and more, Dead Sea Scrolls scholars have busied themselves with the philology, palaeography, and linguistics of comparing text with text, scribal hand with scribal hand, biblical language with Qumran scroll. Nearly all the leading figures in the field have been trained as biblical scholars, earning their living by teaching in universities or seminaries, their outlook data driven, dominated by historical criticism.

Our frame of reference is closely bounded by the biblical tradition and rabbinic Judaism. There has been very little scholarship to relate the scrolls to the broader Mediterranean world, or to the history and sociology of religion.’1

EXEGETISTS AND HISTORIOGRAPHERS

Students of the Dead Sea Scrolls and their related texts tend to fall into two broad groupings – exegetists and historiographers; those who study the internal nature of the texts and those who look more to their historical setting.

By virtue of the exegetists being far greater in number, their views tend to dominate current discussions, but perhaps partly as a result of my work, there is an increasing call for scholars to take greater account of outside factors and the historical situations that existed at the time the texts were composed or written down.

It is only now, more than a half a century after the discovery of the first of the Dead Sea Scrolls, that the Academy of Qumran scholars are beginning to lift their eyes above the deserts of Judaea, clear their vision of the dusty sand and see, in the distance, the clarity of the vast Mediterranean area.

As Professor Lawrence Schiffman, of New York University, put it in an amusing parody of the massive achievements and shameful lapses of the first ‘Jubilee’ years of Dead Sea Scrolls research:

And they shall be studied together with the papyri of Egypt in light of later Jewish legal texts from the Judaean. Desert and Rabbinic literature.2

For future tasks, he instinctively pointed his colleagues in the direction of Egypt – towards the signposts I have already suggested in this book.

Response from academics, on specific areas of their own expertise, has generally been supportive. On alternative interpretations of the meaning of the Copper Scroll, for example, particularly in the context of the weight and number terms given in the Scroll, there has been a considerable consensus of acknowledgement that previous interpretations have not been correct. Amongst those scholars conceding that previous translations are deficient, one of the world’s experts on the Copper Scroll, Judah Lefkovits, of New York, has reiterated that the Scroll is much more problematic than some scholars would allow. He has written a number of books on the subject, including a recent classic work The Copper Scroll 3Q15: A Reevaluation; A New Reading,Translation, and Commentary3, and now does not think that the conventional translation of the weight term as a Biblical talent is necessarily correct. He has suggested that it might be a much smaller weight, such as the Persian karsch. In supporting my claim, in relation to the weight term, against the views of previous researchers, he now believes the total precious metal weights have been greatly exaggerated.

A number of other scholars have shown support, albeit with reservations, for the more extensive theories connecting the Qumran-Essenes to Egypt. These include Professor George Brooke, of Manchester University, who wrote a foreword to this book, Jozef Milik (leader of the original Dead Sea Scrolls translation team), Henri de Contenson (discoverer of the Copper Scroll), Professor Hanan Eshel and Esti Eshel (Bar Ilan University, Jerusalem), Rabbi Mark Winer (Senior Rabbi West London Synagogue), Helen Jacobus (The Jewish Chronicle), and Professor Rosalie David (Keeper of Egyptology, Manchester Museum).

One eminent scholar, Professor Harold Ellens, University of Michigan, has come out strongly in favour of the generalised theory, which he says is almost certainly basically correct. In his view, the particularised findings relating to the Dead Sea are worthy of serious consideration and, he says, may be one of the most important contributions to Dead Sea Scrolls’ research of recent times.

...upon the basis of independent personal research, since reading Robert Feather’s book, I have been able to confirm almost all of his findings and conclusions. I am now wholly persuaded that his work is right on target.4

If there is a partial acceptance of the possibility of a connection between the Qumran-Essenes and the Jacob-Joseph-Pharaoh Akhenaten period, it is in demonstrating the detailed historical links that most hesitancy arises. It is a connection Jozef Milik refers to as: ‘equivalent to the jump the Masonic movement makes in relating its origins to the time of Solomon’s Temple’. Whereas Professor George Brooke prefers to see any possible correspondences to Egypt for the Essenes as occurring at the time of the High Priest Onias IV, rather than much earlier.

SUPPLEMENTARY EVIDENCE

To try and respond to this criticism, and reinforce the evidence included in the first edition, additional detail is presented in the remainder of this chapter. Some of the supplementary detail has emerged from analysis of new and existing Dead Sea Scrolls texts, suggestions from other scholars, subsequently published material and recent archaeological discoveries.

Both ends of the chain that join Pharaoh Akhenaten and the Qumran-Essenes are, I believe, firmly established. Placing each link in the chain for a length of time spanning over 1,000 years, as proven historical events, is a tall expectation, especially as we are talking of events ranging from some 2,000 to 3,300 years ago. The jump inevitably gives rise to some speculative evidence, but even if not one single link can be demonstrated, the validity of the case is not undermined. Eduard Meyer, supported by a number of other scholars, showed, as early as 1940, that reminiscences of Akhenaten had survived in Egyptian oral tradition and had surfaced again after almost 1,000 years of latency.5

The anomalies and puzzles that litter Dead Sea Scrolls (and Old Testament) interpretation require answering, but time and time again the classic phrases ‘more research needs to be done’, or ‘we just do not have an answer’, ends a research paper. Many of these surprises and problems can be convincingly resolved by looking towards Egypt.

As it is, there are dozens of very conclusive sequential pericopes lying along the route. Some of the more potent are, I maintain, visible through the behaviour and evidence of:

- Joseph and Jacob – contemporaries of Akhenaten

- Levitic priests – appointed at the time of Jacob and referred to as palace guards (c.1350 BCE)

- Moses – a Prince of Egypt who takes up the Hebrew cause (c.1200 BCE)

- Presence of Egyptian priests amongst the Exodus of the multitudes

- Ongoing conflict between priestly factions as to monotheistic tabernacle/temple practice (from c.1200 BCE–70 CE)

- Continual appearance of the sun disc – Akhenaten’s symbol for God through the history of the Promised Land (1,000–100 BCE)6

- Allusions of Isaiah (c.740 BCE) and Ezekiel (c.590 BCE) to Egyptian monotheism

- Examples of royal insignia employed by King Hezekiah (c.720–690 BCE) and by King Josiah (c.640–610 BCE) which bear Egyptian motifs characteristic of hieroglyphs designating ‘Aten’

- Disclosure of the Book of Deuteronomy (620 BCE) – hidden for some 400 years

- Onias IV – High priest who built a Hebrew Temple in Egypt (c.190 BCE) including an Atenist symbol

- Thinly veiled references to Akhenaten, his Queen and High Priest, in the Dead Sea Scrolls of the Qumran-Essenes – some of which date back to First Temple and Mosaic antiquity

- Continual allusions to Akhenaten’s Holy City and Great Temple in the Dead Sea Scrolls and Old Testament.

Pivotal in the chain of links is the role of Moses. Ever since Sigmund Freud7 made a direct connection between the Hebrew religion and the monotheism of Akhenaten, other authors have flirted with the idea. Most recently Jan Assmann, Professor of Egyptology at the University of Heidelberg,8 has re-evaluated the work of Sigmund Freud in the light of modern knowledge and come to the conclusion that the monotheism of Moses can be traced to the monotheism of Pharaoh Akhenaten.

FROM MOSES TO THE QUMRAN-ESSENES

Evidence for the link from Akhenaten to Moses is summarised above and discussed earlier in the book.

The defined task is therefore to try and demonstrate more clearly that a separate priestly sect existed right the way down from the time of Moses to the Qumran-Essenes, within the history of the Hebrews, and that that sect held distinct religious views consistent with those of Akhenaten. Also that the sect had the opportunity of possessing and preserving unique information and material objects not available to the generality of the Hebrew people.

That there were two warring factions within the Levitic-priestly groups is apparent from the earliest stories of the Exodus, right way through the Old Testament. The problem then resolves into one of differentiating the groups and showing which one was more closely aligned to the religious views and practices espoused by the Qumran-Essene sect and demonstrating that they could indeed have transformed into that sect. For this evidence I rely heavily on the work of a retired Professor from Hebrew University, Cincinnati, Ben Zion Wacholder, and Professor Richard Elliott Friedman of the University of California, San Diego.

The central theme of the priestly rivalries revolved around who got the privileges, and material benefits, that attached to the portable Tabernacle and subsequently the Temple in Jerusalem.

To try and understand which group was in the ascendancy and what they promoted, we need to gently enter the world of biblical analysis. People like Karl Heinrich Graf, Wilhelm Vatke and Julius Wellhausen,9 in the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century, analysed differing strands of authorship in the Old Testament and their findings, together with the latest ideas, are admirably summarised in Professor Friedman’s book Who Wrote the Bible?10

In essence parts of the Bible are attributed to group allegiance authorship through the different titles they used for the name for God and the common thrust of the texts. These apparently conforming parts are known as:

| E - | where God is referred to as Elohim*59 |  | ||

| J - | where God is referred to as Jahwe | First four Books of Moses | ||

| P - | where Priestly views on law, rituals predominate | |||

| D - | Deuteronomy | Independent author(s) Book |

The authorship group of E is associated with the earliest priests who guarded the Tabernacle and its contents in their place of keeping at Shiloh, in the North. This group claimed descent from Moses.

The authorship group of J is associated with the earliest priests who were originally based at Hebron, and then, as guardians of the Temple and its contents, at Jerusalem, in the South. This group claimed descent from Aaron.

The rivalry between these groups stretched back to Sinai, to the episode of the golden calf, and the rebellion of Korah, Dathan, Abiram and On (Numbers16).11 In each episode the authors’ bias seems to centre around whether the author was a supporter of Moses or of Aaron.

Professor Freidman puts it this way:

The overall picture of the E stories is that they are a consistent group, with a definite perspective and set of interests, and that they are profoundly tied to their author’s world....The priests of Shiloh were apparently a group with a continuing literary tradition. They wrote and preserved texts over centuries: laws, stories, historical reports, and poetry. They were associated with scribes. They apparently had access to archives of preserved texts. Perhaps they maintained such archives themselves, in the way that another out-of-power group of priests did at Qumran centuries later.’12

It is the Shilonite strain of priests that became alienated from the Temple at a very early period in Israel’s history and, who I maintain, were the spiritual ancestors of the Qumran-Essenes. Through careful analysis it is possible to show how the Shilonite connection could have run all the way down to the Qumran-Essenes. Their original stewardship of the Tabernacle meant that they would have had access to all the associated precious accompaniments brought out of Egypt with Moses – precious metals, secret texts, and copper.

Some of the hiding places mentioned in the Copper Scroll include locations in the North, not far from Shiloh, at Gerizim, and the territory of the Samaritans. The undoubted close relationship between the Qumran-Essene beliefs and those of the Samaritans has been an ongoing subject of debate and the scenario of events described here explains to some extent why there should be such a relationship.

When the Shilonites were banished from the office of High Priest by King Solomon, around 970–80 BCE, the Aaronite priests took control of the Temple and it is only some 300 years later that the Shilonite influence bursts through with their revelation of the Book of Deuteronomy, in the time of King Josiah, c.620 BCE.

Could the Shilonite priests really have maintained their identity through 300 years of being out of power and without a major religious centre? The question is posed by Professor Friedman,13 and his answer is an emphatic ‘yes’. The power of Shilonite thought emerges with the Prophets Jeremiah, who is considered with Baruch to be the author of Deuteronomy, and the prophet Ezekiel.14 The latter is considered by Professor Ben Zion Wacholder to be the founder of the Qumran-Essene sect.

The view of Professor Ben Zion Wacholder is highly pertinent to the role of Ezekiel in the continuity of the Shilonite priesthood.

IN THE KINGDOM OF THE BLIND. . .

Ben Zion Wacholder is a partially blind Professor of the Hebrew University, Cincinnati, but he has the ability to see through the tangled undergrowth of intertwined scrolls and is a king and much respected father-figure in the land of his peers. In the celebratory fiftieth anniversary conference of the finding of the first of the Dead Sea Scrolls, held in Jerusalem, he created a minor sensation by going against his colleagues in claiming Ezekiel as the first Essene.15

He perceives many of the sectarian Dead Sea Scrolls of the Qumran-Essenes, such as the Temple Scroll; New Jerusalem Scroll; the Aramaic Testament of Levi, Qahat, and Amram; Jubilees; and the Cairo-Damascus documents, as derivative of Ezekiel’s refusal to recognise the legitimacy of the Second Temple and standing outside normative Judaistic authority. In a sense he recognises two quite separate sets of biblical texts – Ezekielian and non-Ezekielian.

By going back to Ezekiel’s time of the sixth century BCE, Professor Wacholder bridges a large part of the gap between the Qumran-Essenes and Pharaoh Akhenaten, and his views forge Isambard Kingdom Brunel*60 size links in the intervening chain. Whilst I agree with many of the Professor’s contentions, I believe that some of Ezekiel’s apparently derivative scrolls contain material that predates the prophet by many centuries. But Professor Wacholder goes further. The Zadokite priests who feature in the Book of Ezekiel have generally been associated with the theocratic state founded by Jeshua ben Jozadaq and Zerubbabel – respectively, High Priest and rebuilder of the Second Temple after the return of many Israelites from captivity in Babylon.16 Ben Zion Wacholder disagrees with this view as follows:

I, however, differ with this accepted interpretation. As I see it, Ezekiel’s Benei Zadok (sons of Zadok) reflect a movement that stood in opposition to the sacerdotal authorities who controlled the First Temple from the time of Solomon, and whose descendants ruled Judea until the Seleucid persecution. In fact, the book of Ezekiel may be read, as indeed it was by the author of CD (Cairo-Damascus Documents) and many of the rabbinic sages, as an indictment of the preexilic high priests. Moreover, it is becoming increasingly apparent that the book of Ezekiel served as a kind of textbook or systematic program for sectarian Judaism of the Second Temple era.17

If Ezekiel is in the direct linkage from Qumran to Akhetaten, then Professor Wacholder’s next assertion takes us back from First Temple times, c.950 BCE, a further 250 years. Whilst ‘Deuteronomistic’ ideology, visible in many parts of the Old Testament, shows Israel prospering when it obeyed God’s laws but suffering when it strayed into apostasy, Ezekiel contradicts this perspective.

As Ezekiel saw it, Israel had been an apostate nation ‘ever since their sojourn in the wilderness.’18

In other words, Professor Wacholder maintains, as I do, that there was a strand of separatist priestly followers stretching all the way back from Qumran to the wilderness of Sinai who had a different understanding of monotheism and its worship. This strand preserved an understanding and recalling of a form of worship far closer to that of the Egyptian Pharaoh Akhenaten than the rest of the Hebrew community.

Can one really believe that Ezekiel made up a detailed, divine vision of the Temple and its Holy City and by weird coincidence the details matched, in many respects, that of Akhenaten’s Temple and Holy City? A vision that saw a temple that far exceeded the actual size of the Temple Mount, set in an area of land far greater than the city limits of historical Jerusalem could accommodate. I think not.

After the re-establishment of the Second Temple, around 540 BCE, the Aaronite priests are again in command and effectively retain control of the High Priesthood right down to Seleucid times in 200 BCE.

When the Seleucid Greeks take control of the country the Aaronite high priests are out of favour and a Shilonite priest from the family of Onias seizes the opportunity to become High Priest. This priest, Onias IV, is ousted by the new High Priest, Menelaus, and flees to Egypt. There he does a very strange thing. He builds a new Hebrew temple at Leontopolis, near Heliopolis. The argument as to why I believe Onias IV was the Teacher of Righteousness, and why his description matches that described in the Dead Sea Scrolls, is set out in more detail in a sequel book to The Mystery of the Copper Scroll of Qumran. It is, I believe, at Leontopolis, in Egypt, that Onias IV had his knowledge of the Akhenaten strain of monotheism that had percolated down through the years of the Shilonite priests, reinforced by contact with the Theraputae19 and by the residual knowledge of Akhenaten that still resided at Heliopolis.

Again one could ask how the knowledge of Akhenaten could have survived for so long in Egypt. Much of the evidence has been set forth earlier in this book, but in this instance I note the views of Professor Jan Assmann.20

In one of the most brilliant pieces of historical reconstruction, Eduard Meyer was able to show, as early as 1904, that some reminiscences of Akhenaten had indeed survived in Egyptian oral tradition and had surfaced again after almost a thousand years of latency.21 He demonstrated that a rather fantastic story about lepers and Jews preserved in Manetho’s Aigyptiaka could refer only to Akhenaten and his monotheistic revolution. Rolf Krauss and Donald B. Redford were able to substantiate Meyer’s hypothesis by adducing more arguments and much new material.22

When Onias IV returned to Judaea, around 160 BCE, I believe it was he who led his followers to sanctuary at Qumran, where they established a settlement in many ways similar to those of the Theraputae in Egypt. One only has to look at the Old Testament writings of Ezekiel, who Professor Wacholder insists was a prime force in founding the Essene movement, to see why Onias IV might have led his disciples to Qumran. In Chapter 47 of Ezekiel the prophet relates how the cleansing waters of a Great River ran through a vast temple, and then how those same cleansing waters would one day flow into the Dead Sea at Ein Gedi and turn it into a sea that can sustain life. The Great River he was remembering can only be the Nile and the vast temple the Great Temple of Akhenaten. Ein Gedi, by the Dead Sea, is mentioned by Pliny in relation to an Essene settlement that he said lay to the north of it, and he was almost certainly referring to the settlement of Essenes at Qumran.

That the Qumran-Essenes thought of themselves as an élite group, more holy than the rest of the population, is beyond question. One might, however, question whether, in referring to themselves as ‘Zadokite priesthood’, the Community was associating itself with Zadok the High Priest who appeared to be opposed to the Shiloh priesthood, who I am suggesting were the ancestral predecessors of the Qumran Community. Part of the answer given by Professor Wacholder has already been cited, and additionally Professor Philip Davies, of Sheffield University, asserts that in his view the Essenes did not claim Zadok the High Priest as their founder or have any special attachment to the Aaronic Zadokites or their cause.23

THE TEMPLE

One of the troubling aspects of a number of the Dead Sea Scrolls, in the words of Israeli scholar, of Bar Ilan University, Esti Eshel is; “their persistent reference to Temple priests being appointed at the time of Jacob. This is especially true for the Testament of Levi scrolls.”

As indicated in earlier chapters of this book, the evidence from the New Jerusalem Scroll and The Temple Scroll, as well as from the book of Ezekiel of the Old Testament, is to my mind conclusive, in that they are all talking of distant memories of a much larger temple – one that could never have been located on the Temple Mount. There just isn’t the room for it. The conventional explanation is that all these sources are talking about a visionary temple. This just cannot be the case; for no other reason than that descriptions of visionary temples would not need to include details of where the latrines were positioned!

Descriptions in The Temple Scroll of the Qumran-Essenes, considered to derive from pre-First Temple Jerusalem times, bear many similarities to The Great Temple at Akhetaten. Indeed knowledge of the Scroll has been attributed to Moses; in the Apocrypha (2 Baruch 49) and in Midrash (Samuel). How can this be? There was no temple in Jerusalem at the time, and yet Moses apparently had possession of a detailed plan of God’s Holy Temple.

There are many other puzzling aspects of The Temple Scroll, some of which are discussed below.

When my three Dutch airline friends Klosterman, Luz, and Margalit,24 researching in the 1980s and 1990s, identified ancient Akhetaten as the closest fit of any city in the Middle East to that described in the New Jerusalem Scroll, which by the way never mentions Jerusalem, they are tying the description to Akhenaten’s Holy Temple. Their work was more recently resurveyed in a massive study by Michael Chyutin,25 an Israeli architect, who came to a similar conclusion (and also that the town plan of the pseudo-Hebrew settlement at Elephantine bore a remarkable similarity to that of Akhetaten).

Perhaps one of the most significant of Michael Chyutin’s findings relates to number mysticism, which he touched on in the 1994 official-backed Discoveries in the Judaean Desert series. He found he could only make sense of the numbering system in the New Jerusalem Scroll when he applied Egyptian dimensional measurements. He later concluded that the measurements of the city alluded to in the New Jerusalem Scroll make use of Egyptian metrology dating back to at least First Temple times. There is also an implication that the author of the New Jerusalem Scroll was Egyptian educated and was heir to a tradition deriving from the Elephantine temple, in southernmost Egypt. The author’s inability to explain the sacred destiny of the city, why its proposed location for a vast temple does not include mention of Jerusalem (which, in context of the ideal Temple, also receives no mentioned in The Temple Scroll, Ezekiel, or even Deuteronomy) and why we are back to at least the ninth century BCE for descriptive purposes are major criticisms that have previously remained unresolved. Unresolved unless the conclusions of this book are taken on board.

When the Qumran-Essenes built their main settlement building at Qumran in ‘exact’ alignment to the main walls of Akhenaten’s Temple and constructed ten ritual washing pools, they were echoing a recorded memory of that Temple.

Uniquely, and unknown from anywhere else in Israel, one of the ritual washing ‘Mikvaot’ has four divisions – just as the ritual washing basins in the Temple at Akhetaten exhibited.

In a recent conference reviewing the previous fifty years of research into ‘Qumranology’ one paper discussed commentary on Isaiah’s three nets of Belial. The point was made that the Qumran Damascus Document defined the three nets, or traps of evil, as whoredom, wealth, and defilement of the Temple26 – but what temple was Isaiah talking about? The setting for Belial's traps is Jacob’s son, Levi, warning the inhabitants of the land – noticeably not mentioning Israel. Yet at the time of Jacob there was no Temple in Jerusalem, nor would there be for another 400 years.

The author of the paper, John Kampen of Bluffton College, America, goes on to make a scathing challenge to the entrenched notion that the Qumran-Essenes ‘spiritualised’ the activities of the Temple in Jerusalem, which they saw as being defiled during the reign of the Hasmoneans (164 to 63 BCE), through an alternative observance of Temple worship by replacing it with observance of the Law. For John Kampen:

(those) who propagate this view have misunderstood the relation ship of law and temple within it. Law does not take precedence over temple, the place of God’s presence. The problem is that Israel has not followed the correct law because it was rooted in the wrong temple.27

He concludes that the defiling of the Temple was something the Qumran Community had experienced in its own history, and for them the law did not take precedence over the Temple. The Temple the Qumran-Essenes were concerned about was, he insists, not the Temple in Jerusalem but an idealised future Temple. Whilst agreeing with the main thrust of his argument, the visionary Temple was, I maintain, based on a real design. Details in the Temple Scroll, for example, spell out the dimensions of the longest Temple wall as 1600 cubits, equivalent to 800m. The length of the longest wall of the Great Temple at Amarna has been measured, from detailed archaeological excavations, as being 800m. This, amongst many other congruent features, is no coincidence.

The temple being referred to is real, as conveyed by Yigael Yadin, archaeologist and a Deputy Prime Minister of Israel, in his study of the Temple Scroll, where he states that it ‘refers to the earthly temple of the present’, as well as one of the future.28 Israel had not followed the correct law, according to the Qumran-Essenes, because it was rooted in the wrong temple.

FOUND UNDER KANDO’S BED – THE TEMPLE SCROLL

The Temple Scroll, or 11QT as it is professionally known, is the longest (884.5cm) of the Dead Sea Scroll manuscripts and in some ways the most puzzling. Recovered in 1967 from Bethlehem, where it had been hidden under Kando’s*61 bed (see Chapter 1, note 4), it now resides in the Shrine of the Book building, in Jerusalem.

One of the more perplexing narratives in the Temple Scroll is the author’s assertion that the Lord revealed to Jacob at Bethel, as he did to the Levi (confirmed in another Dead Sea Scroll, the Testament of Levi), that the Levites would be the priests in the Temple of the Lord. There is no such mention in the Bible, where the Levi are not appointed until the time of the Tabernacle and Moses.

As Yigael Yadin points out in his seminal book, The Temple Scroll, it is quite mysterious that the Bible gives no divine law as to the construction of the Temple, and yet the writer of the Temple Scroll seemed to have access to a plan and a written law. Beyond a mention of this plan, in 1 Chronicles 28:11-19, there is no detail of it in the Old Testament – a real conundrum for biblical sages. However in Midrash Samuel it is recorded that God gave Moses the Temple Scroll, and that it was passed down through the generations to David and Solomon. That this original Temple Scroll, with its wealth of planning detail, ever came into the possession of Solomon or normative authority is extremely doubtful, as all its prescriptions severely contradict normative Judaism. It explains one of the main reasons why the Essenes rejected the Temple at Jerusalem – it did not conform to the plan that they had of the Temple.

Nor does later Rabbinic lore confirm that David had a set plan he gave to Solomon. In Midrash Tehillim (see Glossary) we find that King David proposed a measurement of 100 cubits for the height of the Temple, compared to the very modest 30 cubits specified in Deuteronomy, Chronicle, and 1 Kings for Solomon’s Temple.29

The logical conclusion is that the information in the Temple Scroll, in its original form, existed before Moses, and that it described the plan of a real temple that was not the Temple at Jerusalem. The details must have been handed down in secret through a distinct line of Levitical priests to the Qumran-Essenes, who based their copy on the original version.

Dating and understanding the Scroll is an ongoing controversy. According to Professor Lawrence Schiffman, of New York University, dating the Scroll hinges on the meaning of a section in it known in Hebrew as ‘Torah Ha-Melech’ – Law of the King. Much of this section comes from Old Testament sources but regulations relating to the Queen, provision of a round-the-clock royal bodyguard, the King’s army council, conscription in the case of war and division of booty are not found in the Bible. The stipulation regarding the Queen, in fact, goes against the Bible in requiring the King to stay with her all the days of her life. In the Bible the wife may be ‘sent away’.30

Where the author of the Temple Scroll got his information has always been a puzzle. However, if the King referred to is Akhenaten, we know he remained, for a pharaoh, unusually faithful to his wife Nefertiti, and to her alone, all the days of her life; and he was constantly attended by a bodyguard. Assuming a background of Akhetaten, and that the requirements of the Law of the King related to an idealised renewal in Israel, many of the anomalies of the Temple Scroll fall away, and reasonable explanations are forthcoming. For example the phrase; ‘He should not return the people to Egypt for war’, that appears in the Temple Scroll makes little sense for any candidate kings of Judaea or Israel, unless there was some locus in Egypt.

The king’s army council is aptly described in Cyril Aldred’s insightful Akhenaten, King of Egypt31 – the army commanders ‘formed a council of management around the king, like henchmen around their war-lord’ – in almost a paraphrase of the description in the Temple Scroll. No decisions on going to war were made without their consultation.

THE COPPER SCROLL AND THE GREEK LETTERS THAT SPELL AKHENATEN

One of the questions that has been posed on my reading of the mysterious Greek letters interspersed amongst the ancient Hebrew text is; ‘how can one be sure of this reading? Are there any examples of Pharaoh Akhenaten’s name in Greek records?’

The simple answer is that there are no examples of his name because very soon after his death it was lost, even to Egyptian common history. It was not, I maintain, lost to the secret tradition of his followers. To quote Professor Rosalie David, Reader in Egyptology at The University of Manchester, and a world authority on ancient Egypt:

There is no Greek equivalent of Akhenaten. His previous Name, before he changed it to show his allegiance to the Aten, was Amenhotep IV. The Greek version of Amenhotep was Amenophis. Also, there is no Greek equivalent of the city, Akhetaten. I am not aware that there is any reference to either Akhenaten or Akhetaten in Greek literature, because the king and the city were obliterated from history until the site of Tell el-Amarna (Akhetaten) was rediscovered in recent times.32

There are two difficulties in being absolutely certain about any comparisons of the Greek letters. Firstly, the pronunciation of the Pharaoh’s Atenistic, or Atonistic, name is at best an approximation from the hieroglyph versions we have. One of the best examples of the fourteenth century BCE name can be seen in a double tablet cartouche now in the Turin Museum, Italy. The vocalisation from this cartouche shows that whatever the exact sounds might have been, their order is very close to similar sounding Greek letters that appear in the Copper Scroll. The odds against finding matching sequential sounds in two four-syllable words from different languages, each having approximately twenty-two different sounding letters, is more than 160,000 to 1! Secondly there can be no certainty that the Qumran scribe chose the same Greek letters as we might subscribe to today.

To come as close as possible to the choice, I consulted numerous sources of Greek dictionaries. These indicate that similar sounding names to that of Aton and Akhenaten, or Xuenaten as it is sometimes written,33 would have called for similar Greek letters as those used in the Copper Scroll. The validity of this view is re-enforced by the opinion of Professor John Tait, of University College London, who considers the reading of the Greek letters as quite plausibly the name of the Pharaoh in question.

That the name of Aten or Aton, the name Akhenaten knew his God by, is embedded throughout the Old Testament has many attesters, from Sigmund Freud34 onwards. Most recently Messod and Roger Sabbah35 have published an extensive study on the subject and conclude that Akhenaten was the forerunner of the Hebrew religion and that not only the Old Testament, but specifically the Dead Sea Scrolls, include reference to Akhenaten and Aton. They note that the name of God appears in many forms in the Old Testament, but in an earliest invocation as God of the Exodus, it appears as the Hebrew word ‘Adonai’, and as ‘Adon’.36 Many Egyptian names are read with the letter ‘D’ or the letter ‘T’ interchangeable – Touchratta or Douchratta, Taphne or Daphne, and in Egyptian Coptic the letter D can be pronounced ‘D’ or ‘T’.37 Thus Aton could well be written ‘Adon-ai’ where ‘ai’ relates God to the Hebrews38 in the sense of ‘my master’, or ‘The Lord’.

Another example may be the first identified definitive inscriptional connection between the Hebrews of Egypt and Akhenaten’s name for God, ‘Aten’. It can be found in the Alnwick Castle collection of Egyptian artefacts, from Northumberland, in England.39 Here, on a dark blue glass rectangular object, dated to the Amarna period, is written:

Ra nefer Xeperu Ua en Aten

In Chapter 12 there is a discussion on the possible names the Hebrews might have been known by during their stay in Egypt. The suggestion I put forward as the most likely source was the Egyptian word ‘Cheperu’.

A possible translation of the inscription then becomes:

The beautiful sun God of the Hebrews the Aten

The idea that Cheperu, derived from the name of a creator god Chepri or Khepri and often represented in ancient Egypt in the form of a scarab beetle, is not without significance, as will be seen later in this Chapter.

THE HEBREW-EGYPTIAN LANGUAGE LINK

In the same way that conventional scholarship has tended to veer away from Egypt as a fundamental source for biblical studies, it has wrongly attributed the origins of the Hebrew alphabet to the Canaanite coastal region. If there is one factor that defines a commonality of culture it is a commonality of language.

Prior to the publication of the first edition of this book, in July 1999, virtually every conventional source you cared to consult ascribed the earliest forms of alphabetical writing to the Levant area and Hebrew writing as a derivative of Phoenician, which in turn was thought to have emanated from proto-Canaanite, and Ugarit, dating back to c.1550 BCE. Egyptian was seen to have had an influence on the earliest alphabet, but the original reduction of symbols, from many thousands to less than thirty, was credited to the coastal countries in the region of what is now Lebanon.*62

In collaboration with Jonathan Lotan, an Anglo/Israeli scholar, I went against this view and included a diagram (see Chapter 15), which indicated Egyptian hieroglyphs and hieratic as the main line from which Hebrew was derived. No one is always right, and I would not claim to be, but in this instance....

In the summer of 1998, Dr John Coleman Darnell, an Egyptologist from Yale University, America, and his wife Deborah, were working ‘in the middle of nowhere’, near Wadi el-Hol (Gulch of Terror), about fifteen miles from the Nile and some fifteen miles north of the Valley of the Kings. They discovered inscriptions on limestone walls, now considered to be the work of Semitic people writing in an alphabet with less than thirty letters, based on Egyptian symbols. Their findings were not published until November 1999, when they were authenticated by Dr Bruce Zuckerman, Director of the West Semitic Research Project, University of Southern California, as an earliest ever form of alphabet, which had been developed between 1800 and 1900 BCE, predating any previous find by some 300 years. The inscription apparently refers to ‘Bebi’ – a general of the Asiatics, water, a house and a god.

According to Dr P. Kyle McCarter Jr, Professor of Near Eastern Studies, Johns Hopkins University, America.

...it forces us to reconsider a lot of questions having to do with the early history of the alphabet. Things I wrote only two years ago I now consider out of date.40

For Frank Moore Cross, Emeritus Professor at Harvard University:

...this belongs to a single evolution of the alphabet.41

SYMBOLS OF THE ATEN

Examples of inscriptions showing the Egyptian Aten sun disc, as detailed in note 5 of this chapter, have been discovered in many parts of Israel and are a neuralgic headache for religious historians. They do not seem to know what they represent. Evidence of the worship of the Syrian god Baal and pagan shrines on ‘high places’, throughout the early period of Israelite history, can be explained as aberrations caused by interactions with local deities, or throwbacks to the idolatry of Egypt, but why a king of Israel like Hezekiah, who was particularly strong on monotheism, should use a sun disc and a beetle as symbols remains unexplained in conventional terms.

Both images were in fact basic Egyptian motifs and the sun disc specifically related to Akhenaten’s form of worship. Examples have been found on ancient jar handles and in other forms across Israel. Even more telling are recent finds of bullae, clay seal impressions, with the name of the seventh century BCE King Hezekiah, a reforming king who practised a policy of purging the country of foreign images and influences. Some of the seals show a two winged scarab, but two recent examples show a central sun disc with rays shooting out from above and below and an ‘ankh’ sign (life) on either side. The suggestion that Egyptian iconography, prevalent across Israel and other parts of the Middle East, was adopted simply because it had been associated with a dominant power and had anyway lost its religious significance seems quite inadequate. All three symbols are closely associated with the Amarna period, and the sun disc and ankh sign were the key elements of the Aten cartouche, representing Akhenaten’s name for God. The form of the disc, with rays emanating from above and below, is quite specific to the style of Aten imagery seen on tomb walls at Amarna, where beams of light radiate out from a central sun disc and carry ankh signs at their extremeties.

Two bullae, in the collection of Shlomo Moussaieff, carry the Hebrew letter ‘ntnmlk’ and could well be read as ‘n-aten melech’ – relating Aten to the king.42 However, perhaps the most embarrassing discovery, for devout religious followers, is an inscription found on a storage jar at Kuntillet Ajrud, in the Negev area, dated to the eighth century BCE. This has been interpreted as depicting God with his consort. Other inscriptions are read as ‘I bless you by Yahweh... and by his Asherah.’ The idea of God having a consort is, of course, a complete anathema to Judaism. Whether Asherah refers to a goddess of fertility or simply a female deity is not certain.

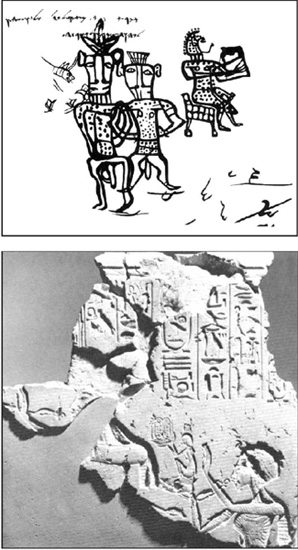

In the light of my theory connecting worship of God, in the Judaeo-Christian tradition, back to the monotheism of ancient Egypt, there is an explanation that might provide solace. The scene depicted on the Kuntillet Ajrud storage jar (see Figure 23) shows a small snake’s head in the top left-hand corner and the two central figures have been interpreted as representing the Egyptian god Bes. I believe the scene is one of Egyptian memory, rather than a contemporary scene in Israelite religiosity.

Whilst the two figures identified as Bes do have characteristics of this Egyptian folklore figure of music and merriment, the imagery seems to me much more like one where two important figures, seated on throne chairs, are being entertained by a lyre-playing courtier. The Bes icon was always a favourite of Nefertiti and the Akhenaten family, as demonstrated on a ring (shown top left of Plate 14 in the illustration section of this book) considered to have belonged to Nefertiti. It is possible, therefore, to come to a quite different interpretation of this controversial scene.

The small snake is a typical Egyptian hieroglyph symbol (having the sound ‘F’ ), deriving its design from the Egyptian corn viper. It appears in the cartouche of Aten, and in this sense means ‘in the name of (Aten)’. More significantly it appears in exactly the same relative position to the head of Akhenaten in a number of Egyptian reliefs; for example, one found on a fragment of parapet, now in the Brooklyn Museum, New York, shows King Akhenaten and Queen Nefertiti making an offering to the Aten. The relative sizes of the Kuntillet Ajrud figures – that I take to be that of the King, wearing the triple ‘Atef ’ (crown) and the Queen wearing the single crown – are highly reminiscent of other representations of the couple adorned with their royal headgear.

That there is an Egyptian dimension to this inscription was, indeed, sensed by École Biblique scholar, Émile Puech. In a lecture he gave on two Davidic Psalms, to a conference on Forty Years of Research, held in Israel, in 1988, he quoted the similarity of the salutation formulae at Kuntillet Ajrud to that seen on a papyrus from Saqqara in Egypt.43

The association in the inscription, which has been read as: Yahweh and ‘his asherah’44 is also reminiscent of the fertility goddess associated with Yahweh by the pseudo-Hebrew community at Elephantine, and it seems that this association continued on through a strand of monotheism into Canaan. Any idea that the Kuntellit Ajrud inscription shows Jahweh with his consort is therefore, I believe, completely wrong, and it almost certainly portrays King Akhenaten with his Queen, Nefertiti.

SUMMATION

The additional information in this Chapter is intended to supplement previous evidence and answer the main criticisms that have inevitably been forthcoming from staunchly orthodox circles in academia. In developing some of the more detailed responses, it is suggested that even stronger arguments have emerged to substantiate the overall thesis. Aspects of these arguments have now been given a visual dimension with the screening of a TV Documentary, based on the book.

Entitled The Pharaoh’s Holy Treasure the one hour Documentary was first shown on BBC2, on 31 March 2002, and featured interviews with leading scholars from America, Great Britain, Germany, France, and Egypt. Much of the presentation fleshed out confirmatory opinion on a possible connection between Qumran and Amarna, whilst other interviewees rejected some of the findings and could not accept the full implications of the new theory.

Two major interviews were omitted by the editors from the TV Documentary on the basis that they were: ‘too supportive of the theory and would damage the controversial balance of the programme’. One of these interviews was with Professor John Tait, of the University of London, Vice Chairman of The Egypt Exploration Society, and a world authority on Egyptian and Greek texts. On being asked for his reading of the mysterious Greek letters that appear interspersed in the Hebrew text of the Copper Scroll, which I read as Akhenaten, he reiterated his view, and that of Professor Rosalie David, Egyptologist at Manchester University, that my interpretation was not unreasonable.

Figure 23: (Top) Drawing and inscription on a storage jar found at Kuntillet Ajrud, dated to the Eighth or Ninth century BCE. (Courtesy BMP.) (Bottom) Section of Palace parapet from Amarna, now in the Brooklyn Museum, New York, showing snake in the same relative postition to Pharaoh Akhenaten’s face as on the Kuntillet Ajrud jar. (Courtesy Brooklyn Museum.)

Robert Feather’s suggestion that the name of the Egyptian king Akhenaten can be read is something I was very interested to hear. The first reaction from someone like me is that that king was written out of Egyptian history deliberately after the end of his reign. It’s certain he was consistently written out of official king lists and therefore one’s first thought is that the name will just not be known later. To me, one of the fascinating things is just to be made to consider whether that name could have lingered on. Egyptologists nowadays are very interested in the difference between the official orthodox records and a view of how Egypt was run, centring on the king, and the possibility of detecting less official beliefs, less official traditions. The trouble is it is very difficult to find such evidence, as in the case of the copper scroll material, but it is a challenge. Immediately I am worried by purely technical questions here, about how the name could be written. The suggestion is, I think, that in this case we are dealing with oral tradition, something passed on by word of mouth and not relying on written records. We are talking about, presumably, a period of something like a millennium at least, therefore changes are bound to occur and one is not going to expect a very exact representation. The other big consideration is that these are Greek letters, and Akhenaten’s second name – the name in his second cartouche – was originally in Egyptian hieroglyphs.

We are immediately faced with the problem that the Greek alphabet cannot properly represent every sound in the Egyptian language. This is a problem with which those who invented the Coptic script, in the third century of the common era, had to cope with – the lack of a way of writing certain sounds. They came up with the dodge of using some native Egyptian characters to fill the gaps. Now, if you have not yet thought of doing that your attempt to represent some Egyptian sounds is going to be second best. But no more second best than the way we in England would now represent Indian words, Hindi, Arabic, or Chinese words. Unless you put in a lot of horrible scholarly dots and dashes, you are going to finish up with an approximation.

One of the letters that’s perhaps the main worry is the reading of the letter that they took as the Greek gamma, but then they would have been faced with the problem that they couldn’t have a very accurate reproduction, and I think it’s just about acceptable that they might come up with the solution of using the letter gamma.

So, someone hearing a name in oral tradition could come up with this group of letters to represent the name of Akhenaten, it’s not unreasonable.45

The second major interview that was omitted was with Professor Harold Ellens, of Michigan University, and his views are amply set out in the Foreword to this edition.

Professor Shiffman ended his parody on the future of Dead Sea Scrolls research, at a conference celebrating the fiftieth birthday of their finding, in the voice of an evangelical preacher:

For up to now you have collected parallels and there has arisen the thought that Jesus, or perhaps his teacher John the Baptist, was a member of the Qumran sect or even that Jesus had been killed at Qumran....46

These remarks might well have enticed me to look more closely at the relationship of early Christianity with Second Temple period Judaism, and more particularly to the special form of Judaism practised at Qumran. As it was I had already embarked on such an endeavour when I came across the quotation. Who would have thought that Professor Shiffman’s throwaway remarks would strike so close to the truth?