I

The Room

‘History includes the present!

Prayer Beads and Cigarettes

“Now, AND AT THE HOUR of our death. Amen.” When she has finished her prayers, she struggles out of her armchair and shuffles across the room. In just a few months she has begun to feel her age. She opens the window at the other end of the room and peeps out over the early-morning clamour of the station and bus terminus below.

Another hot day has been forecast and news images from France have unsettled her; old people who have succumbed to the heat are being kept in refrigerated trucks till awayonholiday relatives return to claim them for burial. Some have already been placed in temporary graves. She draws the curtains against the bright light. Unless she shuts out the sun now, the room will soon become unbearably hot and she will have to retreat to her tiny bedroom at the back of the building for respite. She settles back into her armchair and pours her rosary beads, like precious grains of amber, from a cupped palm into a red satin pouch in which she also keeps the tasbeeh he gave her.

“Ah!” she exclaimed when he casually dropped the beads into her lap, then proceeded to explore the string with curious fingers. “Issa, this is exquisite. I can’t possibly accept it.”

Yes, you can.

“But your friend brought them fro – ”

Tradition. He knows I’d never use them.

“Then that was not why he gave them.” She held out her hand. “I think you should keep them. To remind you of your friend and his pilgrimage.”

Issa leaned forward and folded her fingers gently around the beads. My friend also gave me a lewd T-shirt he’d picked up in Amsterdam on his way back. I’d rather remember him by that. I want you to have the beads.

She squeezed his hand and smiled mischievously. “Can I see the T-shirt before I decide?”

He didn’t laugh often. But that cracked him up.

It was she who first realised that he had gone missing. They had creaked around each other’s lives between cheap paper-thin walls for nearly three years, during which time she had come to rely on his routine.

She wasn’t too keen when she first realised that a student would be moving in downstairs. Sat anxiously in her armchair while he dumped boxes, waiting for the music, the endless cycle of noisy friends to start and never stop. But she was needlessly concerned and sat up, startled, when she heard the rare sound of footsteps ascend the staircase and land outside her door.

Knock knock.

She knew it must be him, so she pressed her palms gently to her hair and opened the door without interrogation.

Good morning, he greeted. I’ve come to introduce myself. I’m Issa. I’ve just moved in downstairs. He extended his hand.

“How do you do?” she responded. “I’m Frances,” and put her hand in his, the old and fragile enfolded in the young and strong. She hurriedly unpacked a smile when he unexpectedly accepted her hopeful invitation to a cup of tea.

“...You must be thirsty?”

That would be very nice, thank you.

Her anxieties proved premature; his movements downstairs soon became a comforting, harmonious accompaniment to her own lonely life.

Like her, he woke early. At six o’clock, as she started to recite her first prayer of the day – “The angel of the Lord declared unto Mary...” – she would hear his radio alarm click on to the serious political breakfast programme he always listened to in the mornings. She puzzled at how one so young could take the world so seriously. We southerners have to, he responded curtly to an enquiring comment she once passed.

The only quality of life most of us dare to hope for is after death.

The response resonated and for a few mornings after that she also tuned in, but the sound of all those politicians lying and bickering first thing in the morning didn’t appeal to her.

She slips the red satin pouch into the pocket of her cotton house gown. Satin pouch cotton pocket, satin pouch cotton pocket. She does not withdraw her hand immediately but waves it gently around inside her pocket. Satinpouchcottonpocket, satin cot an pocket. She enjoys the feeling of cool cotton brushing against her skin and the muffled jingling mingling of the beads, like the sugar crystals reserved for special guests, that she used to sneak into her pocket from her grandmother’s silver sugar bowl when she was a little girl. The two strings of prayer beads always get tangled in the pouch – a trosebery, she thinks – so that she has to peel the beads apart, like seeds from a pomegranate, when she sits down to pray. Sometimes, her gnarled fingers struggle and when the light is bad, she has to start with the cross to help her identify which of the almost identical beads belong to which string. She doesn’t mind; the ritual helps settle her mind – rosary tasbeeh, rosary tasbeeh – and evokes a scene he once described of a mosque in the shadow of a cathedral. She looks up to imagine the sight: a cathemosdraquel, she thinks – to match her trosebery.

“He washed a lot,” she recalled to his mother during her briefvisit to London immediately after his disappearance. “Extraordinary the amount of times that boy washed during the course of a day. He had a shower every morning at six thirty – just as the sports news was starting, you see – and again every night at ten which, I must admit, rather baffled me.”

“Well, that’s not unusual back home,” Vasinthe said, defensively. “In fact, bathing has always been central to our daily routine.”

“Yes, I understand that, except he also washed several times during the course of a day.”

Vasinthe frowned.

“Oh yes. He was always washing. I’m surprised he had any skin left on him at all. Do you know, he washed every time he came in from outside. Yes, I could tell because I would hear the key in the door, then the sound of him kicking off his shoes and walking to the bathroom which is directly under mine, turning on the hot water tap – I could hear the boiler come on – and then washing for several minutes. He would do that every single time he came in from outside, without fail.”

The cross, she thinks as she handles it – a barbaric execution on a plank, the main difference between the two faiths. She hadn’t realised that that was all. In recent weeks she has not been able to make the short walk to Mass and resolves to share this with Father Jerome during his next Communion visit.

“It’s a rather crucial difference,” the priest responds in his heavy French accent.

“But even the immaculate conception and the virgin birth! Did you know that, Father?” She passes him a slip of paper from her bedside on which she has copied a quote in her neat, careful hand. “Have a look at this.”

The priest takes the quote, but sets it aside.

She watches him blow out the candle and slot it into place in the black leather bag, his portable altar, she thinks, like a doctor’s bag is his portable surgery. Portable altars, portable surgeries, portable meals.

“And don’t you think it peculiar, Father, how one religion remembers things another doesn’t?”

The priest picks up the quote:

Behold! The angels said:

“O Mary! God hath chosen thee

And purified thee – chosen thee

Above the women of all nations...

Behold! The angels said:

”O Mary! God giveth thee

Glad tidings of the Word

From Him: his name

Will be Christ Jesus,

The son of Mary, held in honour

In this world and the Hereafter

And of (the company of) those

Nearest to God.

Qur’an S.iii. 42-45

“You mean like Christ, God incarnate – remember – having died on the cross to redeem our sins?” Father Jerome lays down the quote and secures the buckles on his black satchel. Done. Next, Mr Anderson on Stroud Green Road.

She smiles slowly. “I was thinking about the name of the Virgin’s father.”

The priest is hot. He wants nothing more than to snap the white strip from his collar and undo the tight button underneath. He lifts his satchel from the chair and tugs ineffectually at the neckline of his black shirt instead.

“Imran,” she says, picturing him, as she always does, standing on a bridge.

“Pardon?”

“Christ’s grandfather on earth. He was called Imran.”

The priest frowns.

“Yes, Father, he was. And the Wife of Bath, she was an Arab woman. Did you know that, Father?”

By seven he would be scratching around in the kitchen. So far as I could tell, he didn’t eat very much. I never saw him coming and going with big bags of shopping or garbage. But the recycling bin downstairs was always full of newspapers, often with articles cut out. He used to get them everyday from the newsagents on the corner, and some milk for me if I needed it. On his way back, he’d hand the sports section to the fruit vendor outside the station who always gave him a piece of fruit in return.

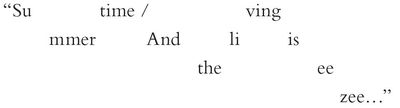

At about ten past eight the volume would go up on the radio for the main interview of the day – some big wig, who, for some or other reason had made it into the news that morning. At nine the radio would go off. This was my favourite time of the morning because then there would follow the most beautiful piece of music I’ve ever heard. A gentle, lilting, slightly sorrowful tune – just beautiful.

As nine o’clock approached, I knew that tune was coming, and as I got my rosary out to say my morning prayers, I would try to hum it in anticipation, but I would never get it quite right.

And so every morning at nine, I would smile with recognition when it came rising up through the floorboards, and I sat down to pray: In the name of the Father, and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit...

I knew then that he would be at his computer, surrounded by all those books, writing for hours, all through the morning, with the same piece of music playing over and over again in the background. He said it blocked out the noise from the street below and helped him concentrate.

She doesn’t know how to use the tasbeeh. He didn’t really know either, but said it was simple, that you just rolled the beads through your hands during prayer rather than pause at every individual one. Sometimes, when she hasn’t been attentive, she’s found herself saying the rosary with his tasbeeh.

When this happens, she doesn’t stop to swap prayer beads, she just continues by counting the decades on her fingers, the tasbeeh dangling from her old bent hands:

Hail Mary,

Full of grace,

The Lord is with thee;

Blessed art thou amongst women,

And blessed is the fruit of thy womb,

Jesus.

At around noon he’d nip out to the local shops on the other side of the station. It’s very vibrant down there, lots of Algerian, Ethiopian and Caribbean stores. You can buy almost anything you can think of – so different from when I first moved here. You couldn’t find an onion then. Bananas. And satsumas! Good heavens, back then they were a treat rare enough for Christmas stockings.

He always knocked on the ceiling to see if I wanted anything. I would knock back, once for no or twice for yes. If I knocked twice, he’d come scaling up the steps, three or four at a time as he used to, to see what he could get me.

He didn’t have a TV, so he’d call by most evenings to watch the news at seven. We’d usually have a bite to eat together, bread and soup, beans on toast, simple fare – like me, he wasn’t one given to excess, though I always got the impression that for him, simplicity was a choice rather than a necessity. Sometimes, when he was feeling homesick, he’d cook his favourite, lentils and rice, for which I soon developed a taste, but which he always ate with a faraway look, only ever having a couple of mouthfuls, moving the food around his mouth slowly, as if it hurt, before giving up and setting his plate aside.

After dinner, he’d stay for a while and chat about this and that – what he’d heard on the radio or read in the papers that day. Sometimes he’d bring clippings from the day’s newspapers to show me. I always pretended to understand them, but to be honest, the issues that interested him were a bit too advanced for me. He must have known I was none the wiser really, but he never lost interest or patience and was always very polite.

Occasionally, he’d even talk about his writing. He’d get carried away and very animated about it all and I would watch with interest, not because I understood very much about what he was saying, but because I enjoyed seeing the excitement his work brought to the face of someone usually so serious.

But more often than not, it was me who did all the talking, especially, you know, towards the end. He didn’t seem to mind listening to all my ramblings, about the war and that. Very unusual, I thought, for such a young lad to be interested in an old lady’s memories. But then again, perhaps that’s not so surprising. After all, he did spend his days writing about history.

Then he’d go back down there, and that piece of music would start up again for a couple of hours. He’d have another shower at ten and at eleven his light switch would click off.

And there you have it. That was how Issa spent his days. Well, at least till everything changed. Occasionally his friend Katinka would call round and sometimes he would go to see her. But otherwise he was here, downstairs, at that computer – day in, day out. Doesn’t sound like much, does it? Boring even, some might say. But they’d be wrong. I spent too much of my life being dazzled by peacocks, learnt too late that it’s the quiet ones, the ones who make themselves invisible, God’s abstemious creatures, who often hold the trick.

She looks up at the clock. Half past nine. A long hot day full of desolate sighs yawns ahead. She wishes it were evening so she could step out onto the roof to take in the cool air. It will be two hours before her newspaper is delivered. Her newspaper and her portable meal. And then? What next? Portable toilets? Portable black bags? Zip. Portable refrigerated French –

She stops herself. Reaches for the packet of cigarettes from the table next to her chair.

Katinka had forgotten a packet during one of her visits some weeks back. At first it lay there for days. She’d look at the packet, wishing for Katinka to call by for them. She almost picked up the phone once to remind her about them, but she stopped herself. Don’t be silly, you old bird. Why would someone want to come half way across London to collect a packet of cigarettes? She smoked them instead.

“A bit late to be starting new habits, Frances,” the woman from Social Services remarked while she laid out her portable meal on a portable tray in her lap.

“Helps pass the time,” Frances responded indifferently.

“But you want to be looking after your health, especially at your age.

“It’s my age that needs the health warning,” Frances said. “It will see me off long before these do.”

“Don’t be so silly,” the woman chided, slinging her bag over her shoulder. “Now eat up. I’ll be back with your tea at five,” and then she vanished through the door.

Portable altars, portable surgeries, portable meals. Come and go. Come and sorry, can’t stop, go.

Black and White

“LADIES AND GENTLEMEN, we have commenced our descent for London’s Heathrow airport. In preparation for the landing, please make sure that your seats are in the upright position and your seatbelts fastened, that your tray tables are folded away and that your hand luggage has been safely stowed.”

The announcement wakes Kagiso. Sleepily he moves his journal into his lap and folds away his table. He does not crane, like the woman next to him, eager to catch a glimpse through the tiny window of the enormous city below; he’d rather not be doing this. Instead, while the aeroplane bides its time, swooping and tilting and dipping in the skies above the sprawling city, waiting for its moment, he closes his eyes again and tries to chase the dreamlike memories that have been scattered by the announcement.

When he was a little boy and already captivated by the moving image, a grainy black and white sequence, an amalgam of the SABC propaganda films of their childhood constituted Kagiso’s mental picture of what that spring morning in September 1970 must have been like. No dialogue accompanied the images, only the imagined rattle of an antiquated projector. He knew very little about what actually happened on that day, so his mind film was very short.

In it, she is walking down a road in an affluent Johannesburg suburb. A two-month-old bundle is strapped in a blanket to her back. She is in search of work. She knocks on another front door. A heavily pregnant woman opens. They have a brief exchange, which he cannot hear above the rattle of his imaginary projector. The pregnant woman smiles and invites her in. She closes the door.

That is it. The end.

The pregnant woman has her baby, a boy, later that same day. But he only knows that in these few words. That is all there is to know. He never imagined the birth. For a long time it never occurred to him to do so.

He has spent most of the overnight flight from Johannesburg scratching in the journal cradled in his lap, at first repeating, as has become his custom, his opening affirmation as soon as they were fully airborne:

SA 238 Johannesburg – London

Thursday 7th August 2003

I am Kagiso Mayoyo. I grew up in Johannesburg, but I was born in Taung. Taungs as the old people say, the place of lions...

Taung, a small village hardly ever featured on the map. Approximately half way between its more famous neighbours: to the south, Kimberley, city of diamonds and, consequently, home to the largest man-made excavation on earth; and to the north, Mafikeng, besieged by 6 000 Afrikaners under the leadership of Generals Snyman and Cronje at the start of the South African War in 1899 and defended by Colonel Robert Baden-Powell for 217 brave days.

Yes, the very same and very honourable Colonel Robert Baden-Powell, founder of the Boy Scouts, brave defender of Mafikeng and arguably the determiner of Issa’s fate. But has anyone ever heard of heard of the Black Watch? And does anyone even know that, were it not for them, Mafikeng would have fallen to Snyman and Cronje because, during the siege, Baden-Powell relied heavily on the Barolong, the Black Watch, my people, to defend the town?

History was not intended to capture this part of the story; Baden-Powell went to great lengths to omit it from his reports and from his diaries. He also omitted to mention that my people were forced to survive on less rations during the siege than their British counterparts. Yet, at the end of the siege, which had turned Baden-Powell into a national hero in England, not one of my people so much as saw the glint of a medal. But while the Colonel was able to contrive his written submissions of the siege to London, he had less control over the version of events that passed from the mouths of my forefathers into the ears of their descendents. My grandmother would gather Issa and I at her feet on the mud floor of her dark shack that smelt of fire wood and into which daylight sparkled through holes in the corrugated iron like stars in the canopy of night.

“Forget about medals,” she’d roar in a big voice imitating the elders in the kgotla. “Land will be our true reward for aiding the British in this war. The honourable Baden-Powell has promised it to us in abundance.” But then my grandmother would lower her head and look to the mud floor between her feet. “They received,” she would start, letting her pointing hand rise and fall three times, once for each word that followed, “not one inch. African land – Baden-Powell’s to give, Baden-Powell’s to withhold.”

My grandmother would lean forward, her elbows resting on her knees. “‘Forget about medals,’ the elders urged, ‘and land takes long to allocate. But money, money is easy to give and we hear that the good people of Britain have raised money, a lot of it, £30 000 for the reconstruction of our town. The generosity of the good people of Britain, that will be our true reward.’”

At this point I would look to the forefinger on my grandmother’s limp hand as it dangled between her knees, and when it started to unfurl as it always did, I knew what was to come. “Not one penny. The only reward our people received for their sacrifice, was more death – more than, 1 000 of our people died of starvation. So, your Boy Scouts’ Baden-Powell may be a national hero in Jo’burg and London, but here, among our people, he’s a lying thief.” And then my grandmother would disappear into the even darker darkness behind the thick curtain that divided the shack in half and into which we never assumed we could follow.

Surprised?

I was too. And angry. Exactly how, I started to wonder, could one people’s hero be another’s villain? And how, I wanted to know, would my people have been any worse off if the demonic Boers had been victorious?

But what has all this past got to do with me, now, here hurtling northwards towards Issa-less London, the African sun setting dramatically to my left? Well, everything. Ma Vasinthe received an e-mail from Issa some months before he went missing. It contained only one line: ‘The past is eternally with us.’ It may have contained more. Ma Vasinthe may have deleted the rest before she forwarded the e-mail to me, but I doubt it. Issa was very good at one-line summations. ‘The past is eternally with us.’ That is very Issa.

So yes, even as we approach the equator at an altitude of 36 000 feet and travelling at an awesome 840 kilometres per hour (Taung not even a speck on the global co-ordinates of our flight path), the past gives easy chase because of Issa. It was he who first challenged the official version of events we were taught in school, though I must confess that I shook my head in dismay when he called Baden-Powell a ‘lying thief’ in our history class. This caused an outrage that unsettled sensibilities at our private school for months – Mr Thompson, our history teacher, being leader of the northern suburbs branch of the Scouts and a longtime admirer of the Colonel.

But Issa remained resolute, even as he became the butt of snide comments from Maths to Phys Ed: ‘Dreamer, schemer, history’s cleaner.’ Eventually, Ma Vasinthe, who usually let us fight our own battles, intervened. She put Issa in touch with a research student at the university, who helped him compile a bibliography of recent revisionist research into the South African War. It took weeks and Issa read every entry before presenting it to Mr Thompson.

“Conjecture!” he exclaimed dismissively, throwing the bibliography to one side. “Mere conjecture. Speculation by a bunch of new age leftists at Wits. And woe betide that university for encouraging it. History cannot be re-written,” he confirmed. “History is, and at St Stephen’s we accept only the thorough, rigorous and sanctioned historical versions outlined in the syllabus, in which, let me remind you, the conflict of 1899 to 1902 is referred to as the Anglo-Boer War. I would advise you to remember that, Shamsuddin, when you take your examinations.”

But Issa didn’t heed the warning. As I read the question in the mid – year exam asking to explain Baden-Powell’s role in the siege of Mafikeng, I knew that not only would he ignore the alternative question on the Jameson Raid, but also that he would present Mr Thompson with his view of Baden-Powell as a lying thief. Even though the final examination of that year was externally marked, the fact that Issa had compromised his mid-year scores meant that in the end he got five A grades and a B for matric, rather than the six A grades he would almost certainly otherwise have attained. It was a defining moment. Issa was never given to excessive displays of emotion, but in the end he lost the struggle to fight back the tears as a huge drop fell, plop, on the official advice of results.

Issa took to his room for three days playing ‘We don’t need no education’ at full volume, over and over again. During that time, only Ma Gloria was allowed in. We never knew what they spoke about. When he eventually emerged, it was to pick up the phone to turn down his place at the prestigious white liberal University of Cape Town where we had both, to Ma Vasinthe’s delight, been accepted.

I’m going to UWC, he declared to our shocked assembly when he put down the phone, and then spent the next few days rushing in a late application to the University of the Western Cape, the intellectual home of the left and the most radical university in the country.

I should perhaps also mention that Taung has its own claim to fame, unearthed as it were, by my great-uncle, my grandfather’s brother, while he and his fellow labourers were toiling away in a lime pit in 1925. My grandmother still keeps the article from The Star announcing the discovery. I took a copy of it for my journal the last time I saw her:

Tuesday, February 3, 1925

THE MISSING LINK?

FOSSIL SKULL MIDWAY BETWEEN MAN AND THE APE

LIME CLIFF FIND NEAR TAUNGS

IMMENSE IMPORTANCE OF DISCOVERY BY PROFESSOR DART

A scientific discovery of the very first importance has been made in the Union and developed by investigation from Johannesburg. So far as its nature can be put into a sequence, it is the discovery of a fossil skull representing something really midway between man and the great apes.

The expression “the missing link” – loose and unscientific as it is – most clearly covers the nature of the owner of the skull in question, which is that of an individual about six years of age...

I remember Issa asking me from the corner of his mouth where my forefather’s name was when my grandmother brought out the article during one of our visits to Taung. I shrugged my shoulders.

Missing, he whispered. Just like the Black Watch. Missing from history. Missing from archaeology. Like a missing link.

When the aeroplane finally slams onto the runway, his head falls forward, once again spilling his rekindled dreams. He presses back into the seat to steady himself against the forwardbackward thrusting of the craft as it rushes down the runway, wings distorted like a mating mantis, straining desperately to bring its trans-global propulsion to a halt.

“Ladies and gentlemen, welcome to London Heathrow. Please remain seated until the aircraft has come to a complete stop. We trust that you’ve enjoyed your flight with us. On behalf of the captain and all the crew, we wish you a pleasant stay and look forward to seeing you again in the future. Thank you for flying South African Airways and goodbye.”

In the arrivals hall, Katinka walks up to the monitor of flight arrivals: SAA 238 Johannesburg landed 06:25. She smiles at the safe arrival of her saviour, her knight in student banger. It was Kagiso who insisted that Issa stop to give her a ride through the scorching Karoo all those Februarys ago, poised as they were, at the dawn of a new world. They have spoken on the phone several times since Issa went missing in April, but this will be their first reunion in many years.

Summer of 2003

THEY HAVE BEEN STATIONARY ON the motorway for nearly ten minutes, though, for Kagiso, after all the speed and motion, it seems like much longer. An overhead electronic road sign flashes a warning: ‘Congestion ahead. Slow down.’

“Has there been an accident?” he asks, moving around awkwardly in his seat.

Katinka shakes her head. “Nope, just the rush hour into central London.”

“Sjoe!” he exhales before unbuckling his seat belt to remove his jacket. “You were right. It is hot.” He leans forward, shaking his arms behind him to shed the unwanted garment. “The pilot warned of a scorcher on the plane.”

Katinka adjusts her sunglasses. “I know. Can you believe it? There’s been great excitement about it on the radio as well. But I’m not complaining. I like this transformation.” She pulls up the handbrake and reaches down to a cavity by the gear stick for a packet of cigarettes. “Fag?”

Summertime in London. Coats and boots, low grey skies and bare trees, long dark nights and long miserable faces, have all been rolled up like winter rugs and stuffed into the cupboard under the stairs – the control switch on the central heating panel finally flicked, with the victorious sigh of a survivor, from constant to off. However brief its forecast stay, however disappointing its outlook, spirits are high: anything is better than the winter.

Now, dragonflies dart around to the buzz oflawnmowers. Garden furniture has been dusted, huge sun-deck umbrellas unfurled, and cookers abandoned for barbecues. Flat roofs, however precarious, have become terraces. Long carefree dinners are enjoyed outside. At nine thirty when it is still light, it is hard to imagine the long winter nights when it is dark by four. Trees are lush and green.

The sky, especially down by the river, is big, blue and high, Katinka thinks. Issa used to love it down there.

‘London ceases to be London.’ Pubs are covered in hanging baskets bursting with brightly coloured blooms and by midday, skiving punters flow over onto the pavements like the white froth from their chilled glasses. Flesh is everywhere; shirtless men, wispy-frocked women, translucently pale at first, painfully red as the season progresses, celebrate their liberation from the confines of coats and jackets. Parks, like temples of Akhenaten, burst with sun worshippers; the animated movement of skate-boarders, roller – bladers, kite flyers, Frisbee throwers, contrasts acrobatically with the horizontal inertia of the religious proceedings. The annual traditions of tennis at Wimbledon, cricket at Lords, racing at Ascot, the jubilation of carnival, long queues at tourist attractions and nightly classical music concerts at the Royal Albert Hall all confirm that, even though it might not look like summer, it definitely is not winter.

Inching their way through the city, Katinka turns up the volume on the radio, then turns to smile at Kagiso:

There is nothing ambiguous about this summer, she thinks. It will surely be remembered for generations to come, earning its place in the national memory of climatic abnormalities, along with the storm of ‘87, the summer of ’76, the floods of ’53, the gales of...

She remembers walking the streets of the sun-baked capital in July, desperately dishing out ‘Missing’ leaflets of Issa to anybody who would take one.

At the time she found it hard to imagine that earlier in the year they were grid-locked for hours when a few inches of snow had brought the city to a standstill. Once again Britain’s fragile infrastructure stood by the roadside, helpless hands on flabby hips, jeering at stranded commuters. Trains, also capable of being rendered immobile by leaves, ground to a halt on icy tracks and motorists forced to spend the night in their cars stuck on frozen motorways, snowed in ahead of the snow ploughs and gritters who got caught up in the gridlock having left their depots too late.

How do they manage in Russia?

But then, as cloudless day succeeded the novelty of cloudless day, a feeling of disbelieving excitement took hold of the city: the wish that ‘if only it could be like this every day’ supplanted by the glorious reality of it being like this everyday.

“Today London was hotter than Nairobi!”

“Keep your homes well ventilated.” (Houses built for the cold can become murderous furnaces in the heat.)

“Drink plenty of liquids.”

“More sangria, anyone?”

“Strawberries?”

The tube became even more unbearable than usual. “Ladies and gentlemen, this train will no longer be stopping at Cockfosters. In your own interest, we have been redirected to the Caribbean instead. Ladies and gentlemen, this train is for the Caribbean. Please stand clear of the closing doors.” Smiles became broader, skins darker, office hours shorter.

While bookmakers braced themselves for the biggest weather-induced betting spree since the summer of ’76, leaf-fearing trains ground to a halt on temperamental railway tracks – in the heat they had buckled – and motorists were once again stranded on constantly worked-on but eternally inadequate road surfaces – in the heat they had melted.

How do they manage in India?

On the 10th of August the unprecedented was confirmed: the mercury reached 37.9°C at Heathrow, 38.5 in Kent, the highest since records began in 1875, the highest, in fact, since the thermometer that contained it, was invented. Paradise had come to London. And before the year was over, heaven arrived too, in the form of a big gold cup brought back from a rugby pitch in Australia. Everybody wanted a photo-op, especially the ‘Things can only get better’ Prime Minister, who was, by now, gagging for a bit of good news, perhaps making constant invocation to his name-sake saint, the finder of elusive things.

And now Kagiso, who also understands something of the frustration of a futile search, has arrived to a city transformed. Fountains have become swimming pools and the sandy enclaves on the riverbank at low tide, venues for impromptu beach-like parties: “Do you really like it? / Is it is it wicked? / We’re loving it loving it loving it / We’re loving it like that.”

When Katinka tells him that they’re approaching Issa’s flat, he looks intently at the throng, the crowded pavements, the busy roads, the well-stocked shops already trading briskly, but all he can see in the teaming multitude of normality is what has gone from it, what is not there, skulking, a haunting absence everywhere he looks – the missing link, he thinks, between him and the city.

He wants to leap out of the car and shout, “Stop! Please, don’t anybody move. Everybody just stand still.” That will make finding him a lot easier. But who would take any notice? People would just walk through him, around him, like they’re doing right now, paying no attention to the cavity in their midst.

“I can’t park here until after six thirty this evening,” Katinka explains when they eventually pull up outside the flat. “I’ll have to drop you here, if that’s okay?”

A few seconds lapse before Kagiso registers that she is talking to him. “Sure! That’s fine, thanks.”

“I’ll pick you up for dinner at six thirty. Say hi to Frances if you see her. Tell her I’ll pop in this evening. And get some rest. You look completely fucked.”

Homelands

KAGISO IS IN LONDON TO PACK and clean Issa’s flat, but apart from the bookcase, there isn’t actually much to pack; apart from a thin layer of dust that has slipped in through the gap under the door, like the angel of death, he imagines, to cover everything. There isn’t really much to clean.

Katinka had warned him of the heat on the phone, but he was dismissive – I’m from South Africa. How hot can London get? When he returns to Issa’s abandoned flat after dinner, he opens the only window in the room. In Johannesburg, he would be able to step through it onto his balcony overlooking the pool. Here, there is only this tiny window, a droning bus terminus and an entrance to a station into which people flow like miners into the tunnelled baking bowels of the earth.

He turns away from the window and moves towards his open journal on Issa’s desk. He writes the date, Friday, 8th August 2003. And then he writes two words: disappear disappearance. But that is all he can manage, so he starts doodling instead. He turns the F of Friday into an E, which he then forces into the number 8. He extends the tail of the y into a squiggly circle all around the date. Encouraged, he moves his nib over to the two words. He slashes them into syllables. He colours in the loopy letters, except the p’s. These, he turns into two sets of searching eyes with bushy eyebrows. Their tails become noses. He adds two sad mouths, then a loop around each word transforms them into faces. The words now seem to wrap around the faces across the eyes, like blindfolds. He doesn’t like the image so he blots out the negative prefixes and tries to invert the sad mouths into happy smiles. This only achieves sinister grins. Frustrated, he draws an angry line through the sketches, clambers out of his clothes and walks into the shower.

On the eastern side of the city, Katinka is seated at her kitchen table, pen poised at the top right-hand corner of the page (she’d positioned the pen instinctively on the left at first but moved it quickly to the other side when she realised her mistake) eyes on the alphabet stuck on the wall in front of her, another of Karim’s little gifts.

Karim.

Whom she does not want to share.

Karim.

About whom she speaks to no one.

Karim.

Her secret.

Karim.

Now behind the wall.

She has pledged to learn the alphabet during the summer vacation. “If I do nothing else this summer,” she told a colleague, “then at least I will have learned a whole new code, turned the key to literacy in a whole new language.”

Now she is seated at her kitchen table, pen poised at the top right-hand corner of the page, eyes on the alphabet stuck on the wall in front of her, another of Karim’s little gifts. Karim. Whom she does not want to share. Karim. About whom she speaks to no one. Karim. Her secret.

Karim.

Now behind the wall.

She says the first letter out loud – aa – and simultaneously pulls a downward stroke on the paper: She sits back to evaluate her effort then repeats the letter a few times before moving on to the next, bá’:

Kagiso steps out of the shower knowing what to write, the words forcing at his fingertips, making them twitch. He does not shave as he had intended, does not dry himself, does not get dressed, but immediately returns to his journal to write, not like Katinka is doing, slowly, deliberately, letter for letter, but swiftly, his fingers responding nimbly, dishing out words and phrases that have stewed for decades through a keen and agile pen, beads of London water, like teardrops, weeping from his skin.

I am Kagiso Mayoyo. I grew up in Johannesburg, but I was born in Taung, Taungs as the old people say, the place of lions. I found myself thinking again tonight, far away and on the other side of the world, about my place of birth while I was in, of all places, the men’s toilet in a restaurant in Brick Lane, East London.

“East London?” I checked, confused, when Katinka announced our destination. “But I’ve only just arrived.”

“Not that East London! East London here, where I live, in the East End, mate.”

Of course, I’d realised my mistake as soon as I opened my mouth, but I went with it. It felt good to laugh again.

“And here we are, Brick Lane!” Katinka declared, introducing me to the vibrant colourful cobbled street by gesturing up it with a theatrically extended arm. “Like the Meghna River flowing through East London.”

I was amazed. Here was a London you won’t find in the postcard shops. Like the time I accompanied Issa on his illicit trip to Durban. It was as though we had arrived, not in Zululand, but somewhere on the sub-continent. In Brick Lane, where Katinka took me to eat dhal, even the street signs are in another language.

“Welcome to Londonistan,” the waiter joked when he heard we were South African and then, looking at Katinka and then at me, smiled an approving smile, “So nice to see you getting on these days, so nice to see.”

When we had placed our order, I went to the toilet. Inside the cubicle was a long chain of graffiti. It started with: Bangladesh used to be East Pakistan. To this had been added: Pakistan used to be India. The chain rolled on: Israel used to be Palestine / Lebanon used to be Syria / Eritrea used to be Ethiopia / Alsace used to be France then Germany then France / America used to be England / England used to be France. Alongside this main chain ran a parallel chain, around which someone had drawn a huge bracket which pointed to the heading, insha’allah: One day Basque will have been Spain / Northern Ireland, Wales and Scotland will have been Britain / Tibet will have been China / Palestine will have been Israel / Chechnya will have been Russia. Under all of this was a somewhat unrelated contribution thrown in for good measure. It read: St George had never been to England. And in red, right at the bottom, somebody had made a final addition, which made me laugh: And what about Kashmir? Self – ule never contemplated, not even in the bog.

This bit of graffiti reminded me of Taung, my place of birth, because it used to be in the Republic of South Africa, but in 1977 it became part of the newly created Republic of Bophuthatswana under the leadership of His Excellency, President Lucas Mangope. Bophuthatswana was one of the more bizarre homelands because it had no territorial integrity. Instead, it consisted of seven different entities, pockets of Setswana-speaking islands scattered all over the central and northern regions of South Africa.

My mother and I were already living with Ma Vasinthe in Johannesburg by the time it was created, but to a child, it felt as though the whole world had changed, as though my grandmother had been packed up and moved to another planet. Despite Ma Vasinthe’s best efforts to explain, I couldn’t understand how a whole town could become part of another country just like that, and although I hardly knew her at that time, I cried for days about what had become of my grandmother.

My grandmother never acknowledged the change, or Mr Mangope’s puppet presidency, and she didn’t care who knew it. “Idiots and stooges,” she called all those who insisted on their Bophuthatswanan nationality. “The place oflions has been thrown into the puppet’s den. I’ll have nothing to do with it.”

For her dissent, she regularly had her electricity cut and her miniscule state pension withheld. When, seventeen years later, Mangope eventually fell and Bophuthatswana was reincorporated into the new South Africa, my grandmother rejoiced for days, not because she was a patriot, but because she was a democrat and the collapse of the ‘imaginary homeland’ meant that she could now vote in the first democratic elections of April 1994. “I have waited a long time to see this day,” she said as she proudly took up her place in the queue that stretched for miles and miles, “and now it has finally arrived.”

Of course, literally speaking, my grandmother could not see at all, her cataracts having become inoperable.

“It’s because of my political views, isn’t it, doctor,” she confronted the young medic.

“No, not – ”

My grandmother cut him short. “But let me tell you something,” she said, waving a foreboding finger. “Opinions are expressed with this,” she pointed at her mouth, “and as you can hear, it’s in tip-top shape. Do with my eyes what you like, but we know it’s my mouth you’re really after.”

My grandmother was right to be suspicious. She had had medical treatment punitively withheld, but in this instance, her politics weren’t the reason. Even a supporter of the new republic would have been told the same: “Mrs Moyoyo, in Bophuthatswana we can’t do cataracts.”

Ma Vasinthe had offered that she come to Johannesburg to have them removed privately, but my grandmother would hear nothing of it. “Hayikhona!” she exclaimed. “Me, in Jo’burg? That crazy town! I don’t need my eyes that much.”

Ma Vasinthe did not insist. “The operation would have made little difference,” she told me. “After all the years of obscured vision, her brain will almost certainly have forgotten its ability to see.”

This memory made me want to add: ‘Bophuthatswana, Venda, Transkei, Ciskei, Lebowa, Gazankulu, KwaZulu, KwaNdebele, KaNgwane all used to be South Africa’, to the graffiti chain, but I didn’t have a pen on me.

After Katinka and I had left the restaurant and were walking back to the car, taking in the cool air, I recalled the graffiti chain and was glad I had not added to it. Apart from the fact that most of its readers would probably never have heard about the homelands or the immense suffering they contained, I thought it rather pointless to insert a now-settled dispute alongside so many contemporary and unresolved ones.

Disappeared

KAGISO LOOKS UP FROM THE PAPER. In front of him, stuck to the wall above the desk, is a quotation, one of many placed in various locations around the room. This one kindles a nostalgic melancholy, a fetid brooding, like a swampy afternoon, a hot night. He can’t stop himself reading it again:

I consume the day (and myself) brooding, and making phrases and reading and thinking again, galloping mentally down twenty divergent roads at once, as apart and alone as in Barton Street in my attic. I sleep less than ever, for the quietness of night imposes thinking on me: I eat breakfast only, and refuse every possible distraction and employment and exercise.

TE Lawrence

He turns to look around the cell-like room. To someone who didn’t know him, it would seem stripped, cleared of all personal belongings, and abandoned. But to him, the room is full of Issa. It is spartan, monastic; a desk, at which he is seated, a mattress on the floor. The kitchen is a cupboard at one end of the room, the bathroom a tiny cubicle. The only thing of excess is a neat but overflowing bookcase, behind which is concealed the bedstead. The room is sweltering now, but according to Frances, it is a very cold room in the winter, “having only storage heating.” He didn’t really understand what that meant.

On the bookcase is a postcard of home, the skyline at night, taken during a thunderstorm. It rests above the five volumes of the TRC Report, a city of gold balanced on a catalogue of crimes. He remembers sending the card, in the early days, soon after Issa first came to London. He likes the picture. It captures something of the city, he thinks – its drama, its ambitions. People often mistake it for a picture of New York.

He repositions himself at the desk. Earlier that afternoon, he’d come across another picture, one he’d almost forgotten about. It disconcerted him. After having forced himself to look at it for a while, he laid it face down on the desk. Now, his eyes move slowly to the down-turned photograph. Cautiously, as if handling a dangerous device, he lifts the photograph.

It is of the two of them as boys. He remembers Ma Vasinthe taking it with her new camera, Ma Gloria watching from behind. It was springtime. She had got them to crouch on the lawn in the front garden.

“Say cheese.”

“Cheese,” he smiled, self – consciously obedient.

Paneer, Issa said, leaning on his cricket bat. In the picture his mouth is poised for p.

“Why do you always have to spoil things, Issa?” Ma Vasinthe complained. “Let’s do it again.”

But Issa was already halfway up the garden path, eager to return to his cricket match in the street.

Nearly twenty years later, Kagiso has to strain to recognise himself in the shy and withdrawn figure in the picture. But even at that age, Issa’s steely confidence, his intense good looks, were already apparent. He turns over the photograph, this time depositing it in the desk drawer before picking up his pen.

I, we, still find it difficult to accept what has happened. We seldom talk about it. What more is there to say? We’ve given all the statements, answered all the questions. We seldom look at one another for fear of detecting it, lurking, in ever searching eyes. We’ve done, it seems, what we can, provided all the red-T-shirt descriptions, followed the few ephemeral leads to their nose-breaking dead ends. Nothing. Except a pile of ‘Missing’ leaflets for distribution, which, like watches, keys, wallets and cell phones, have become part of the baggage that orbits us as we drift like off-course planets searching an endless universe. Issa, difficult, contrary, spoilt to the last, had been, it seems, the centre of our lives, the improbable silent force that held us all together. Now, sitting in his chair, at his desk, surrounded by his simple things, I am trying again to piece together his story, but there is much I don’t know; Issa had become a stranger to us during his time here. And in the years before he left, he and I, well...

Yet I have to do something with the little I do know. I can’t keep it to myself. I have to let it out. And then, it seems, let it go. For months I have scratched around in this notebook trying to make sense of things, of Issa, of me. But now, sitting in his room in London, his last known address, I am aware that before long I will have packed his scant possessions into boxes for posting back home and cleaned his room ready for its new tenant. By the time I leave London, I will have made his disappearance complete.

He shrinks away from the thought and searches the journal, like a killer returning to the sight of his crime, for the remains of the two words he had mutilated earlier.

When he finds them, he leans forward, trying to draw meaning from their rotting carcasses, like a pathologist, examining these basic components, the two words, just the two, a verb and its noun, that seem to have become a part of his family, it would seem, for good.

He reaches across for the dictionary and copies the definitions:

disappear v.intr: 1 cease to be visible; pass from sight. 2 cease to exist or be in circulation or use (trams had all but disappeared). disappearance n. 1 vanish, evaporate, vaporize, fade (away or out), evanesce. 2 die (out or off), become extinct, cease (to exist), perish (without a trace).

What to make of them? They seem a bit... far-fetched? The noun especially sounds scientific, clinical. Improbable. I can relate them to lost wallets, errant socks, missing pets, the Marie Celeste and planes over the Bermuda Triangle. Until now, I’ve only ever had to use them in that sort of context, and in relation to the disappearance of others: Steve Biko, Victor Jara, Phakamile Mabija, Che. But that was the sort of stuff Issa used to talk about.

We can match his name with other verbs and other nouns. For instance, we can say that Issa has gone to London. Even though he and I had drifted apart by then, that was still a hard sentence to get used to at first. And saying goodbye was an inner wrench, because, for a long time, there hadn’t been very many hellos. We missed him terribly during those first months. Funny how one misses the presence of a silent person. But after a while, we could say it. Issa has gone to London. Issa now lives in London. Issa is studying in London. Issa is doing a PhD in London. We never had difficulty with that one, especially Ma Vasinthe. Issa is doing a PhD in London. It made her proud. It made us all proud.

In the same way, we can attribute nouns to Issa: Issa’s intensity, Issa’s integrity, Issa’s intelligence, Issa’s temper, Issa’s good looks.

But, nearly four months later, we cannot reconcile Issa’s name with this verb, to disappear, and its noun, disappearance. We can’t say, “Issa has disappeared.” We can’t talk about Issa’s disappearance. To us, they are incompatible, irreconcilable; like oil and water, they just don’t mix. Like red next to green, they just don’t match, can make you sick, and if you look at them juxtaposed for long enough, can drive you crazy.

Of course, when it first became apparent that that was what had happened, we had to. We, or rather, I, had to report the event to others. So I had to make his name the subject of that dreadful verb: Issa has disappeared. I had to match it to that unlikely noun: Ma Gloria is devastated by Issa’s disappearance; Ma Gloria rarely talks, following Issa’s disappearance, or, Ma Vasinthe keeps her cell phone on all the time, following Issa’s disappearance. In fact, Ma Vasinthe has taken to clutching her cell phone, like a talisman, waiting, as though the constant contact will make it ring, make him phone. Her assistant once told me that she just apologises at the start of meetings. “But people don’t mind,” she smiled sympathetically. “They understand.”

And in the cinema, which she has developed an increased liking for, she sets it to vibrate and always sits in an aisle seat. She hates flying because then she has to switch it off. I once called her phone when I knew she was on a flight from Cape Town to Johannesburg, just to check. She had switched it off but the message said, “Issa, this is your mother. I had to switch off because I’m flying from Cape Town to Jo’burg. You know that it’s only a two-hour flight. I’ll switch on again as soon as we have landed. Please leave me a message.”

I was waiting for her at the airport when she arrived. I watched as she switched on her phone immediately upon entering the arrivals hall. I saw the expectation that the message signal brought to her face, and then I saw it disappear when she realised that the call was from me.

“You didn’t leave a message,” she said. “Is everything okay?”

“Everything’s fine,” I said. “I dialled your number by mistake.”

She re-recorded her standard message in the car on the way home: “You have reached the voicemail of Dr Vasinthe Kumar. For urgent medical enquiries, please call 011 776 9132 or 011 776 9133. For urgent academic enquiries, please call 011 761 7595. Otherwise, please leave a message here. Thank you.”

As a final act of the day, Kagiso stretches, as if trying to span a continent, towards the postcard of home on the bookshelf. He transfers it carefully to the desk in front of him before falling, knees first, onto the mattress on the floor, asleep before his face touches the pillow.

The Karoo

1989. Slogans resounded across the country.

‘We will not forget?’

‘Steve Biko!’

‘Long live?’

‘Nelson Mandela, long live!’

‘We Shall Overcome!’

‘Liberation before?’

‘Education!’

‘The People Shall?’

‘Govern!’

‘We will not forget?’

‘Matthew Goniwe!’

‘We will not forget?’

‘Hector Pieterson!’

‘Viva?’

‘Oliver Tambo, viva!’

‘Long live?’

‘Govan Mbeki, long live!’

‘Amandla!’

Freedom is taken, never given.

‘Awethu!’

IN DECEMBER, AT THE END OF THE disrupted academic year, they reverse the summer holiday routine of their childhood and set off once again on the long drive from Cape Town to Johannesburg, a 1 500-kilometre journey north-east along the N1, the main national road that runs for days through the vast, arid centre of the country. You can follow its route on a map, as Kagiso now did, wistfully tracing its path with a slender finger from its starting point at the foot of Table Mountain, distracting himself from Issa’s loud ominous silence.

They know the mammoth journey like they do their garden path – Cape Town / Paarl / Worcester / Laingsburg / Beaufort West / Colesberg / Bloemfontein / Winburg / Ventersburg / Kroonstad / Johannesburg – backwards and forwards, eyes closed; summer school holidays were spent traversing its harsh unending miles to get to the coast. Then Vasinthe would drive, vrou alleen, as men observed admiringly, with the boys in the back and Gloria’s constant presence by her side, ready to make conversation, turn cassettes, pour cups of coffee or help keep an eye on the road:

“We need to watch out for kudus now.”

Why?

“Because they’re dangerous.”

But we’re in a car. And we’re going fast.

“That’s why they’re dangerous. If a kudu jumps into the road, this car will fold like paper.”

But there’s a fence.

Gloria laughed dismissively. “That fence is for farm animals. It can’t keep back a kudu.”

Why not?

“Because a kudu is big and wild.”

Wild! The word thrilled him.

“Yes,” Gloria continued. “And with its strong hind legs it can stand right next to a fence three times as high as this one and just hop over.”

Wow! Kagiso, we have to look out for kudus. You look your side. I’ll look mine.

Except to buy petrol, about which they had no choice, they avoided the verkrampte little dorps that occasionally interrupted the otherwise relentless isolation of the journey. Vasinthe always imagined that she would have time, to explain. Gloria agreed that it should come from her, that she should be the one to inform them about the way things were. She knew the dates and the facts and the names. She had them all in her head and at the tips of her fingers; could summon them like she does surgical instruments in an operating theatre. She would be much better at it.

Vasinthe thought constantly about what she would say when the time came. She tried to anticipate how it would arise, how she would phrase things, what questions they might ask. She anguished about not leaving them feeling angry or inferior. These were often among her first thoughts of the day as she tied her sari, while sometimes inadvertently humming her favourite morning bhajan from childhood. She’d rehearse her explanation while she walked the gleaming corridors of Jo’burg General, a time when she also remembered her father. He used the theatre of the hospital to distract her, following the delayed admission of her broken-bodied mother:

“Watch, Sinth!” he said to her when they were expelled from her ward by a cacophony of bleeping machines: “Doctors Laategan, Du Preez and Smidt to ICU! Doctors Laategan, Du Preez and Smidt to ICU!”

“Look,” he prodded her, “here they come.”

She saw a group of earnest, marching medics come rushing down the corridor towards them, their unflinching sights set on the finishing line, the threshold of her mother’s room.

“See their white coats flapping, Sinth. See their stethoscopes.”

“What, Baba?”

“Ste tha scopes.”

“Ste tha scopes,” she repeated.

“Good girl. Come. Step aside now.” He pulled her towards him as if from the path of a speeding car. As it rushed down the corridor towards them, the group reshaped itself into a lean line of hierarchy, a white-coated stethoscoped streak, which flashed past them and disappeared into her mother’s ward, leaving a foreboding gust of wind in their wake that chilled her father to the bone.

“Did you see that, Sinth?” he asked, summoning the excitement of a spectator at Kyalami.

She nodded. “Yes, Baba. I saw,” then threw her arms around his knees.

He crouched and ran his trembling fingers through her windblown hair. “Would you like to be like them one day, Sinth? What could be more important than rushing to save a life?”

And so it was that, as his wife, his ‘Mumtaz’, lay dying, her ‘Shah Jahan’, who within a month would die a premature, brokenhearted death, opened a door in their only daughter’s mind as they sat huddled in a long, gleaming hospital corridor.

“Yes, Baba,” she said.

He lifted her chin and wiped the dust from her cheek with a licked wet thumb. “Good girl,” he said. “Very good girl.”

Vasinthe would run over her explanation in her mind while she checked their homework before she herself sat down to a long night of study. But whatever her preferred choice of words – it changed from day to day – in the end she always decided to leave it till they were a little older. For the moment, she just wanted them to be children. She had herself known too soon:

“Baba. Why isn’t the ambulance taking Ma?”

He didn’t look at her. “They’re sending another one, Sinth. That one is full,” he said as he sat down in the sand to stroke her mother’s limp arm.

“But there was no one in it, Baba. I saw.”

“Come Sinth, hold Ma’s other hand so she can feel you near.” He pulled her towards them. “The other ambulance will be here soon.

It wasn’t. For nearly two hours they crouched in the heat and dust by the roadside next to their wrecked car before the non-white ambulance arrived.

But when the time for explanations came, Vasinthe was asleep.

December 1977. It is a hot day. When they arrive in Victoria West, Vasinthe stops for a break in the shade of the trees by the white graveyard. She and Gloria watch from the car as Issa leads Kagiso by the hand to the small store just across the road. Though the younger by two months, Issa is by far the more confident of the two.

They have promised to cross the road carefully. They will buy their iced lollies, not forgetting to say please and thank you, and return immediately to perch themselves on the low wall beside the car. They will sit quietly; they are not at home now. They disappear into the store. Vasinthe reclines her seat and shuts her eyes. Gloria rolls down her window and remains vigilant.

The boys re-emerge from the store, empty-handed. They walk hesitantly to a barred window at the side of the building and join the short queue. Gloria looks down at Vasinthe whose lips have quickly started to puff the way they do when she is on the verge of sleep; the early morning delivery of Christmas hampers to Taung followed by a visit to the Open Mine Museum in Kimberley was perhaps too ambitious for one driver, in one day.

Gloria slips quietly out of the car and joins the boys in the queue. Issa relinquishes control and slips his hand into hers.

When Gloria steps to the front of the queue she assesses the dark interior of the store through the black bars. It is a general store, selling basic provisions as well as some cooking utensils, paraffin stoves, toolboxes, a couple of bicycles. She asks for two iced lollies. Asseblief. The shop assistant retrieves the lollies from a noisy refrigerator and lays them down on the dirty wooden plank that serves as a counter.

“Dankie.” Gloria lays down R70 on the counter. The assistant is surprised. This is far in excess of the cost of two iced lollies. Gloria adds to the order. “And a bicycle. Asseblief.”

Issa looks up questioningly at Gloria but knows not to interrupt. She pats his hand, still clenched in hers, reassuringly on her thigh. Kagiso has started whispering reluctant responses to a dirty little girl in the queue.

“For the bicycle, you can come around the front.” The shop assistant reaches for the money. Gloria slaps her hand down on it. The woman looks up at her, startled.

“I’ll take it through the window. Asseblief.”

The shop assistant is taken aback. A crowd of curiosity has gathered. Somebody quickly whispers an update to the newcomers. “The bicycle is too big to pass through the window. You’ll have to come around the front to get it.”

Gloria edges the money forward without releasing her grip on the notes. “Then disassemble it. Asseblief.” The crowd murmurs incredulity. Issa studies their rough, leathery faces, their toothless smiles, their threadbare, tattered rags, then looks to the woman behind the counter.

“That’s impossible. I can’t dismantle the bicycle. You’ll have to collect it from the front. It’s not far. You only have to walk around the corner.”

“If you can’t dismantle the bicycle, then you’ll have to break down these bars.”

The assistant splutters in disbelief. “But that’s mos malligheid. You expect me to break down these bars because you won’t come round the front to fetch the bicycle?”

Gloria lays out another R20 on the counter. The crowd gasps. “You won’t break down these bars, but you will break the law by bringing me into the front of your shop.” The lollies have started to melt on the grimy counter. A frenzy of flies buzzes erratically around the sweet sticky water.

Kagiso has tired of the little girl who won’t believe that they are from Johannesburg, that that is their car, that this is his brother. “Maar hy’s ’n coolie en jy’s ’n kaffir,” she objects. “Hy’t dan gladde hare, en joune is kroeser dan myne!” the girl remarks, pointing to the difference in the texture of the boys’ hair. Kagiso tries to enlist Issa’s support, but is brushed off.

“The law doesn’t stop you from coming into the front of the shop.”

“What does?”

“My husband. And you’d better stop playing these silly games. He’ll be back soon.”

“Then I’ll wait.” The crowd gasps. Gloria tightens her grip on Issa’s hand. He watches the sweat trickle from her perspiring palm down his wrist. Soon his hand starts to go numb, but he doesn’t attempt to release it. Instead, he shifts his weight to the other leg as a sort of ineffective distraction and, with his left hand, traces the patterns on her printed skirt.

“Then step aside and let me serve the rest of the people in the queue.” Gloria turns around and scans the onlookers. Nobody steps forward. She repositions herself at the head.

When her husband arrives, the woman reports the deadlock. The man assesses Gloria and the boys. He looks over to the car parked under the trees. “That your car?”

“Yes.”

“Very nice. Jo’burg plates?”

“Yes.”

“Going to Cape Town?”

“Yes.”

“Where will you put the bike?”

“We’ll make space.”

“These your boys?”

“Yes.”

“Him too?” Issa glares at the man from under a furrowed brow.

“Yes.”

Kagiso nudges the dirty girl. “Now do you believe me?”

The man looks at Gloria then at the crowd behind her. He steps back from the counter. He looks at his wife, then turns back to face Gloria.

“The bicycles are sold.”

The woman looks surprised.

“Yes. I sold them this morning, before you came in, to Jan from Soetfontein. He bought them for his boys, for Christmas. I forgot to tell you.”

Vasinthe is woken by the sound of closing doors. “Ready?” she asks sleepily.

“Yes,” says Gloria. “Let’s go.”

On the back seat, Kagiso taps Issa for answers, explanations. But Issa looks past him at the crowd outside the shop. Some start to trail away. Others take up their places obediently in the queue. Issa sees the dirty little girl stoop to pick up the remnants of the molten lollies as the woman in the shop brushes them off the counter and onto the dusty pavement. The girl steps out of the crowd and watches them drive away, holding her salvaged lollies in upturned palms. When they have left the town behind, Ma Vasinthe taps her thumbs on the steering wheel to initiate another sing-a-long:

“We’re all goin’ on a summer holiday / No more workin’ for a...”

But Issa doesn’t join in. He turns away from Kagiso to look out at the dry and barren wilderness that stretches out eternally beyond the windows of their speeding car.

Now, more than a decade later with Issa at the wheel, they are able to anticipate every ridge and bend, peak and valley, as the road cuts its dramatic path from Paarl across the Hottentots’ Holland Mountains – eventual refuge of the indigenous Khoi expelled from the ever-growing Dutch settlement – and into the picturesque valleys of the hinterland, before eventually reaching up through the Hexrivierberg Pass and out onto the great escarpment. They take the longer route across Du Toit’s Kloof Pass, avoiding the new tunnel that cuts through the bowels of the mountain and to which Issa is still not reconciled; a few months earlier he had joined in the demonstrations organised to coincide with President Botha’s ceremonial opening of the tunnel. Why the Huguenot Tunnel? Has nothing happened in the 300 years since their arrival that might also merit remembering? Had they not received enough recognition, enough recompense – a pristine corner of the world’s fairest Cape, forever named Franschhoek, on which to start an industry that would make them wealthy beyond their persecuted Protestant dreams? How many refugees get a clean slate, let alone such a fabulous one?

As they wind their way slowly through history’s majestic backdrops, Kagiso stares out of the window at the fertile valleys of pristine vineyards and orchards unfolding below. This is his favourite part of the journey.

He can’t imagine anywhere being more beautiful and sighs despondently when they arrive in Laingsburg.

But for Issa, Laingsburg is where the real journey begins. Relieved finally to have left behind all the deceptive liberal prettiness of the Cape – the picturesque wine farms, where labourers are paid by the tot; the plush southern suburbs, whose residents know little of the squalor and violence that afflicts their neighbours in the slums of the Cape Flats. Even the breathtaking panoramas from Table Mountain, which also reveal the black hole in the middle of the bay into which his hero has been sucked. What lies ahead is the harsh, honest isolation of the Great Karoo, where everything is exactly as it appears, unforgiving, dry, vast, desolate. He prefers it. Can position himself in relation to it. Death Run looms ahead. He isn’t daunted because it does not conceal what it is, makes no pretences, has no hidden little catches. To him, the desert is an honest landscape.

In junior school he does all his geography tasks on deserts: Sahara is the Arabic for desert; Dune 7 in the Namib, biggest dune on earth in the oldest desert on earth – it never changes shape; the Kalahari grows by a phenomenal two centimetres a year. He calculates that, at that rate, it would take ten million years to travel two thousand kilometres to the Cape. The Karoo gets its name from the Khoi word, karo, meaning dry. But it was once an endless lake. Fossils of aquatic life have been found on what was once the bottom of the lake but is now the surface of the desert. It covers one-third of the country’s surface. He wishes one day to see its illusive hare. His teacher eventually forces another topic on him:

But I like deserts, Teacher.

“Yes, I know that Issa, but what I don’t understand is why you like them so much.”

Issa looks at her, deciding whether to trust her with a piece of himself. Because they’re clean, Teacher.

The class explodes with laughter. Kagiso lowers his head.

“Silence!” the teacher shouts, knocking her ruler on the board. “Silence!” When an uneven quiet has hissed through the class, she returns her attention to Issa. “That is a strange answer, Issa. Tell us, what makes you say so?”

The whole class turns to look at Issa.

“Issa?” the teacher calls out. “Stand up when I’m talking to you.”

Issa stands.

“Now,” the teacher repeats, “tell us why you think that deserts are clean.”

But Issa doesn’t respond. He just stares back at the teacher over the heads of his bursting-to-laugh classmates.

Uncomfortable with the silent standoff, the teacher resorts to threat. “If you can’t explain yourself, I’ll give you another topic.”

“Tell her, Issa,” Kagiso wills silently. Tell her. Tell them all.

Issa doesn’t move.

“It’s because of Lawrence, Teacher,” Kagiso wants to shout.

“We saw the film. It’s his favourite. He watches it over and over again.” Tell her Issa. Tell Teacher that it’s what Lawrence said:

Bentley: ... May I put two questions to you, straight?

Lawrence: I’d be interested to hear you put a question straight, Mr Bentley.

Bentley: One. What, in your opinion, do these people hope to gain from this war?

Lawrence: They hope to gain their freedom. Freedom.

Bentley: “They hope to gain their freedom.” There’s one born every minute.

Lawrence: They’re going to get it, Mr Bentley. I’m going to give it to them. The second question?

Bentley: Oh. Well. I was going to ask... erm... What is it, Major Lawrence, that attracts you personally to the desert?

Lawrence: It’s clean.

“Well then, Issa,” the teacher intones, “if you’ve nothing to say for yourself, your next task will be on something completely different – oceans.” But her decisive nod is undermined by Issa’s immediate response.

Oceans are not completely different to deserts.

The teacher stares back at him across a sniggering class.

They’re deserts of water. And “the desert is an ocean in which no oar is dipped.”

“Don’t distract Ma Vasinthe now. Kudu are nocturnal.”

Knock?

“Noc tur nal.”

Noc tur nal.

“Yes. That means they are most active at night, like leopards and foxes.”

And bats and owls.

“Yes. So we have to be especially vigilant when driving in the dark.”

Vi gi lant. He turns around and stares out the back window at the road already travelled, counting the white stripes as they flick by in the tail lights. There are no other cars behind them. It feels to him as though they are alone in the world. He tries to imagine what he’d do if he were left behind in this wilderness. Would a black dot appear from a mirage on the shimmering horizon and grow slowly into a Bedouin on a camel with a gun? The prospect fills him with dreadful excitement.

Look, he says.

“What is it?” asks Gloria from the front.

He doesn’t respond.

Kagiso turns to follow Issa’s gaze. “Ha ka ka!” he exclaims.

Vasinthe peers into the night sky through the rear view mirror. What she glimpses makes her pull over onto the sandy embankment on the side of the road, sending clouds of dust rushing into the beams of the headlights. They get out of the car and watch in silent amazement as it rises serenely over the horizon, the bride of the night, big and full and red behind a veil of desert dust, like another world coming slowly and silently to envelop their own. He wants to run forward a little, but Ma Gloria is running her fingers through his hair, so he stays by her side, slips his hand into hers and with his left forefinger held up to his narrowed eyes, he traces the outline of the man on the moon.

Kagiso traces the path on the map north, past Johannesburg and across the border into Zimbabwe at Messina. Then on to Harare and across the border into Malawi at Nyampanda. Then up to Lilongwe and around the shores of Lake Nyasa. At Mbeya, he traces the route to the right through Iringa and across the border with Tanzania to Dodoma, then Arusha. Still further north, across the border with Ethiopia at Moyele, up through the Great Rift Valley as far as Asmara.

“As ma ra,” he says, breaking the silence of rubber on tar.

The interruption pulls Issa back from his own far-off place. He can recall whole paragraphs, entire chapters of what he has read, in minute detail:

In these pages the history is not of the Arab movement, but of me in it. It is a narrative of daily life, mean happenings, little people. Here are no lessons for the world, no disclosures to shock peoples. It is filled with trivial things, partly that no one mistake for history the bones from which some day a man may make history, and partly for the pleasure it gave me to recall the fellowship of the revolt. We were fond together, because of the sweep of the open places, the taste of the wide winds, the sunlight, and the hopes in which we worked. The morning freshness of the world-to-be intoxicated us. We were wrought up with ideas inexpressible and vaporous, but to be fought for. We lived many lives in those whirling campaigns, never sparing ourselves: yet when we achieved and the new world dawned, the old men came out again and took our victory to re-make in the likeness of the former world they knew. Youth could win, but had not learned to keep: and was pitiably weak against age. We stammered that we have worked for a new heaven and a new earth, and they thanked us kindly and made their peace.

What? He asks, as if stirred from sleep.

“Asmara. In Ethiopia.”

It’s not in Ethiopia.

“It is according to the map.”

Forget about maps. They don’t show things as they are. Asmara is in Eritrea.

“Eritrea?” He scrutinises the map. “Don’t see it.”

That’s because it’s still a dream. Maps don’t show dreams either. Only nightmares.

“But in reality, Asmara is still in Ethiopia.”

Not to the people of Asmara. Not to those men and women dying on the battlefield for their convictions. To them, Asmara is in Eritrea and will one day be its capital.

From Asmara Kagiso follows the route as it sweeps to the left and across the border into Sudan. At Kasala he pauses, contemplating left to Khartoum or straight ahead to Port Sudan on the Red Sea Coast. He decides on the road to Khartoum, union of the Blue and White Niles. It sounds to him a magical place.

From there, he traces the path up through the Nubian Desert all the way to Wadi Halfa on the shores of Lake Nasser, where his finger leaps across the lake to Abu Simbel and then all along the Nile to places with names, which, like As ma ra, call out to be uttered:

“Aswan

Luxor

Qena

Asyût

Beni Suef

Cairo

Alexandria

A lex an dri a.”

Memory house of the world.

“Is that so?”

Issa nods.

“Let’s just carry on. Imagine that, if we didn’t stop at Jozi but just carried on all the way north, up and up and up. Wouldn’t that be amazing? Let’s do it sometime. You like driving. You can drive all the way across Africa, all the way to Alexandria, to the world’s memory, on the northern edge of Africa.”

Violent Night

KATINKA STRIKES A MATCH AND holds it to the nightlight on her bedside table. Slowly, the tiny flame starts to lick away the darkness from the objects in its shaky circle: two photographs; one of Issa, the other of Karim, and the items from the ritual she enacts here every day. Flowers arranged along the base of each picture. Leaves, picked in passing from the same tree, flat and large, on which to stand ornate bottles of unction. Precious, the crushed essence from a thousand flowers – jessamine, violet, rose – their fragrance so concentrated, it endures a bath. But only ever used here to anoint the cherished photographs.

She reclines and lets the flame lull her back into the violent night when she searched the smoky room, looking left, looking right, over and under, for her friend among the dazed onlookers...

Eventually, she catches sight of his red T-shirt, but it retreats from her when she tries to focus on it. So she stops, rubs her eyes, and tries again, this time not looking directly at him, only approximately, so as to keep the blurred T-shirt in view. But then there is a flash and a thunderous noise. She looks towards it – explosion – and in its intense rays, she glimpses a vision of him, not face to face, almost; he has his back turned towards her, slightly, so that she only catches his profile, askance, as he sits, chin to chest, in an opulent room, smoking a water pipe. He doesn’t notice her. From underneath a furrowed brow, he stares ahead in disbelief at the giant screen, which fills the wall at one end of the room.

His shoulder-length black hair is tied back from his face with a black and white kefiya in the manner of the lead singer in one of his favourite bands, Fun-da-mental; one of the first gigs he went to after coming to London. On the front of his red T-shirt is emblazoned an inscription: ‘I am a standing civil war’, and the letters MK. On the back, just below the neckline, the logo of the South African Communist Party and its motto: ‘Simply Revolutionary’.