TOM LAWSON is Professor of History at Northumbria University. He is the author of Debates on the Holocaust and The Church of England and the Holocaust: Christianity, Memory and Nazism.

Published in 2014 by I.B.Tauris & Co. Ltd

6 Salem Road, London W2 4BU

175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010

www.ibtauris.com

Distributed in the United States and Canada

Exclusively by Palgrave Macmillan

175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010

Copyright © 2014 Tom Lawson

The right of Tom Lawson to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by the author in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or any part thereof, may not be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

ISBN: 978 1 78076 626 3

eISBN: 978 0 85773 472 3

A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

A full CIP record is available from the Library of Congress

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: available

eBook by Tetragon, London

For Arthur and Florence

&

in memory of Doug Robinson

Contents

- List of Plates

- Acknowledgements

- INTRODUCTION · From Thinking about Britain and the Holocaust to Writing about Genocide in the British World

- ONE · Defining Terms

- TWO · Genocide in Van Diemen’s Land

- THREE · Ethnic Cleansing

- FOUR · Cultural Genocide

- FIVE · ‘We have exterminated the race in Van Diemen’s Land’: Genocide in British Culture

- SIX · Coming to Terms with the Past?

- CONCLUSION · A British Genocide in Tasmania

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Plates

List of Plates

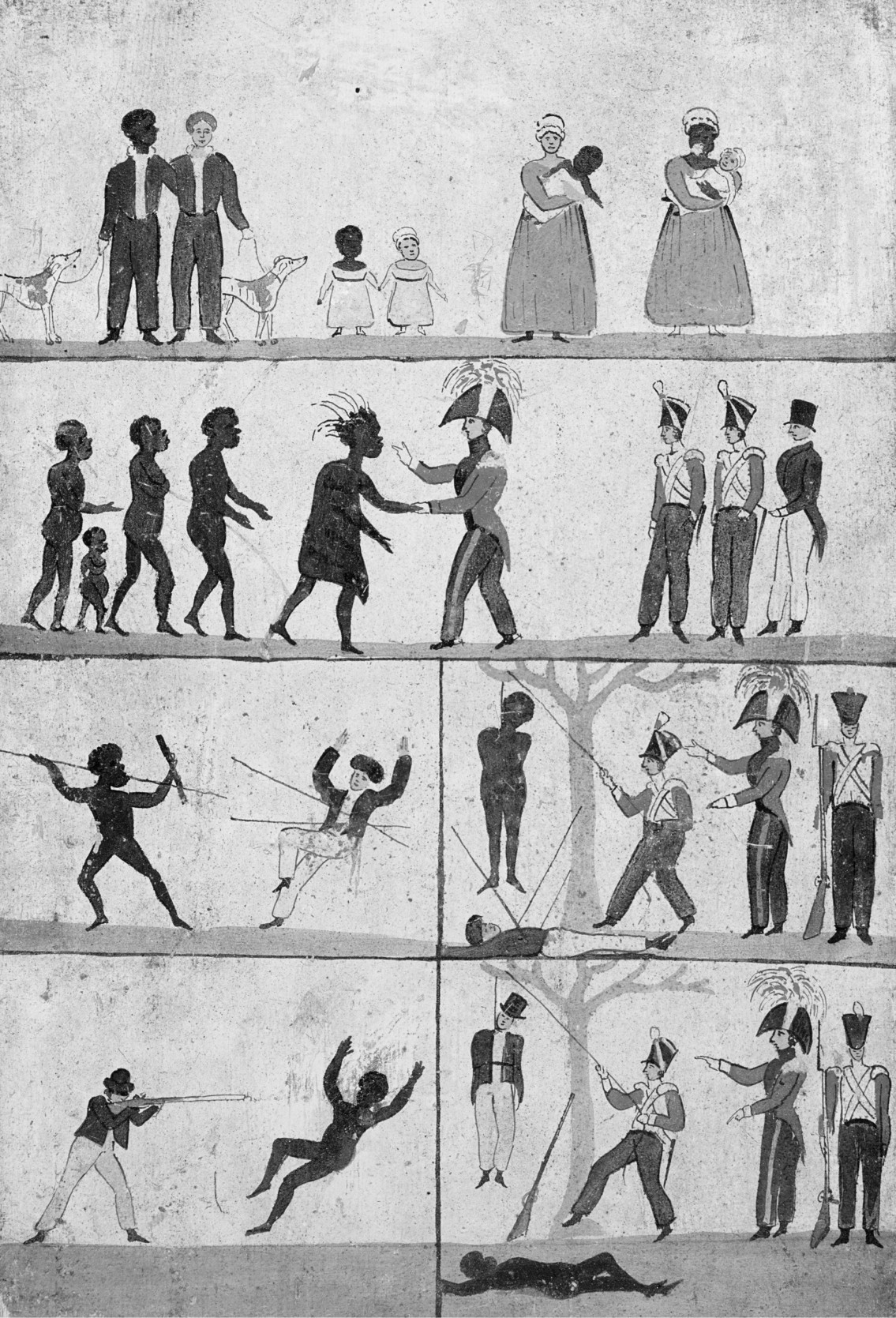

1. Gov. Arthur’s Proclamation to the Tasmanian Peoples, 1830 © Peabody Museum

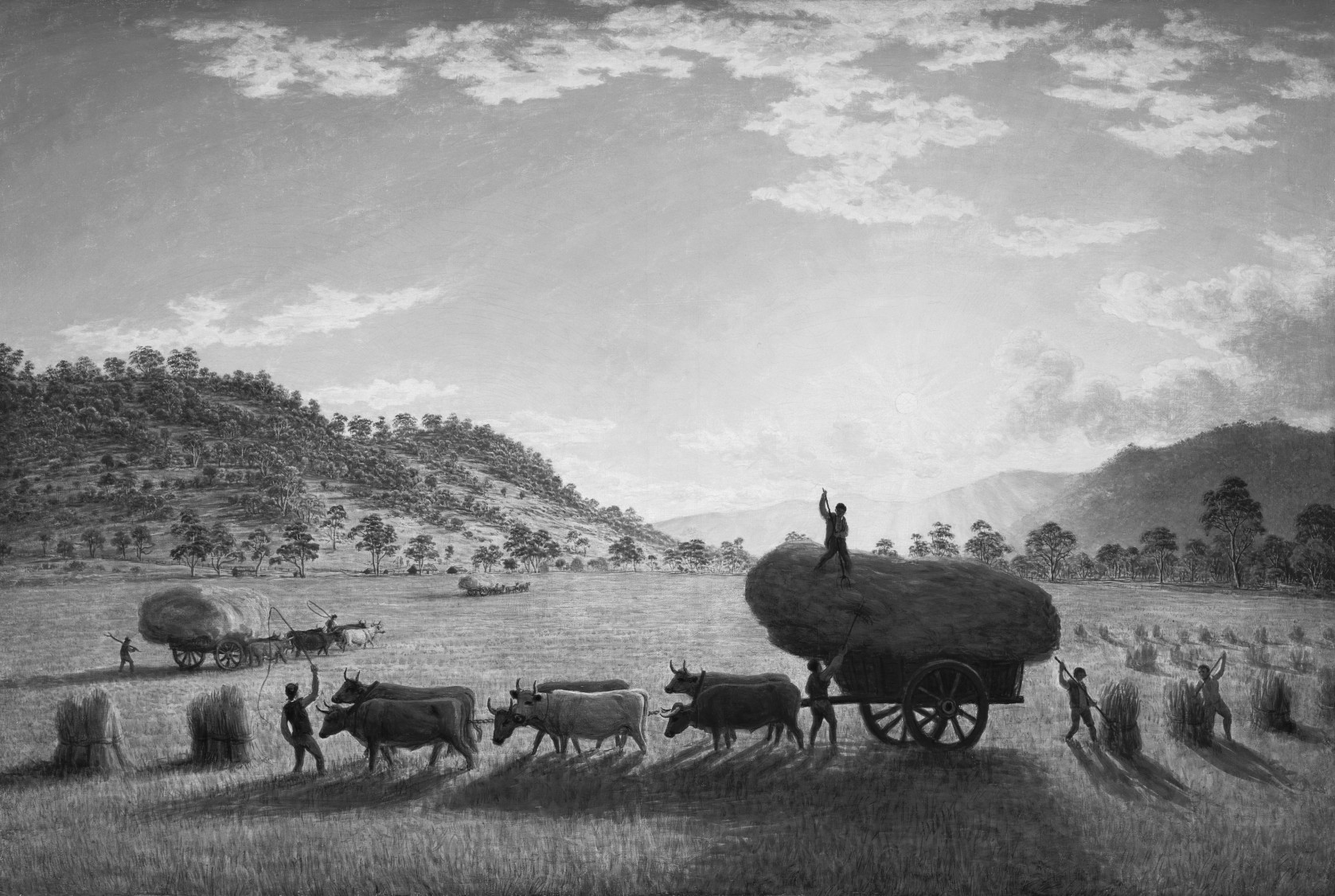

2. My Harvest Home by John Glover © Tasmanian Museum & Art Gallery

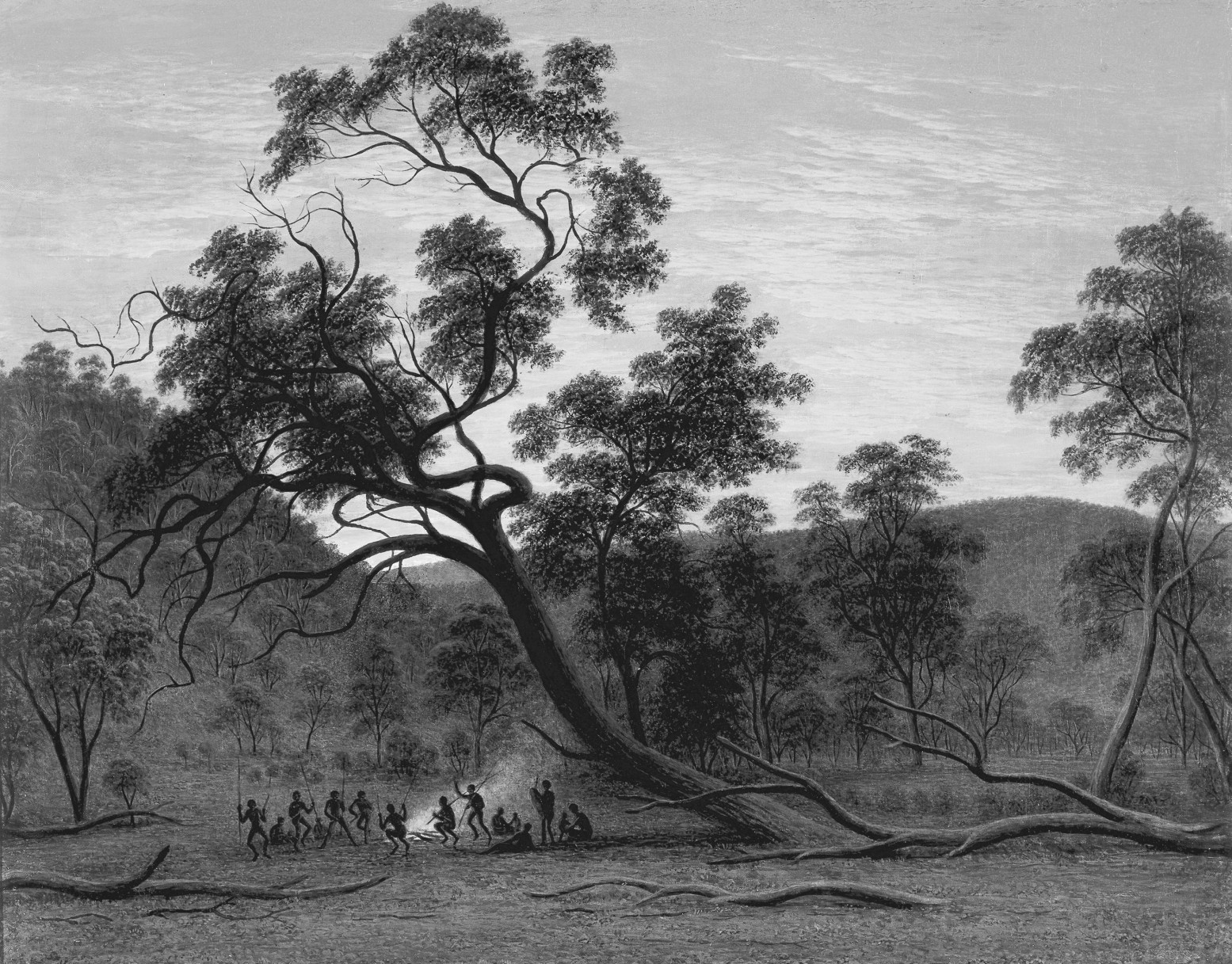

3. A Corroboree of Natives in Mills Plains by John Glover © Art Gallery of South Australia

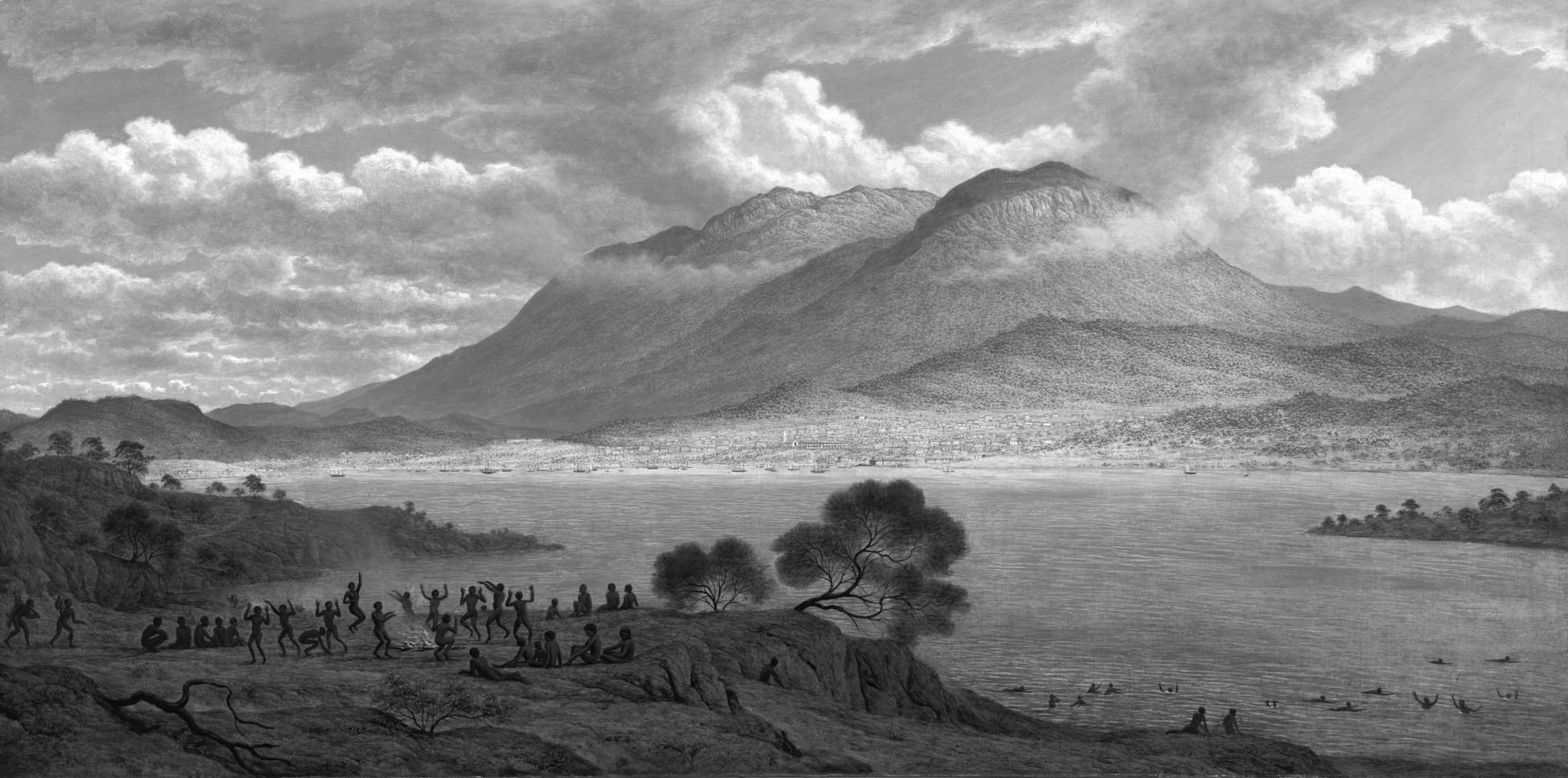

4. Mount Wellington and Hobart Town from Kangaroo Point by John Glover © National Gallery of Australia

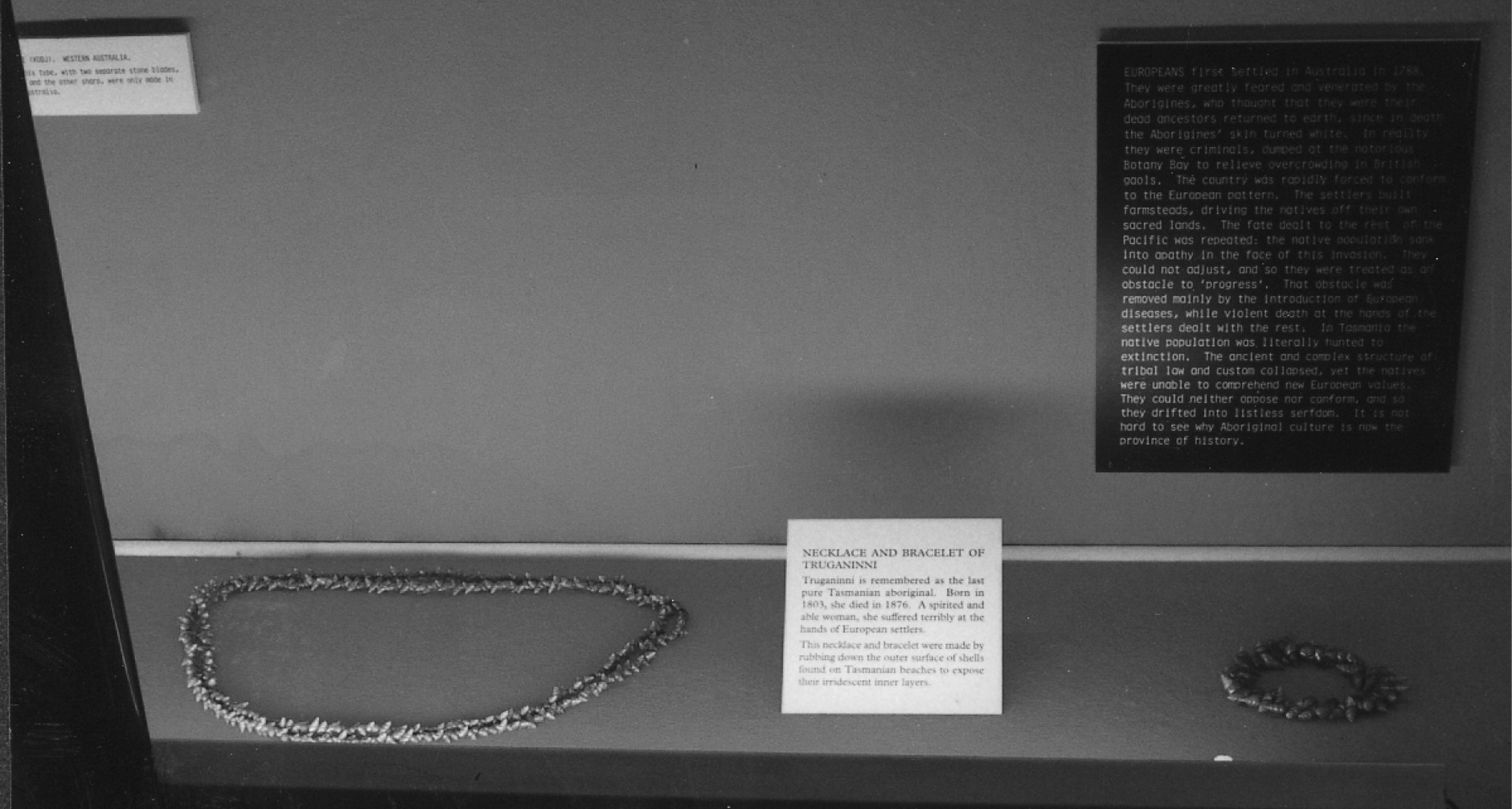

5. Truganini Necklace from Exeter Museum (courtesy of the Royal Albert Memorial Museum and Exeter City Council)

6. George Augustus Robinson’s grave (author’s photo)

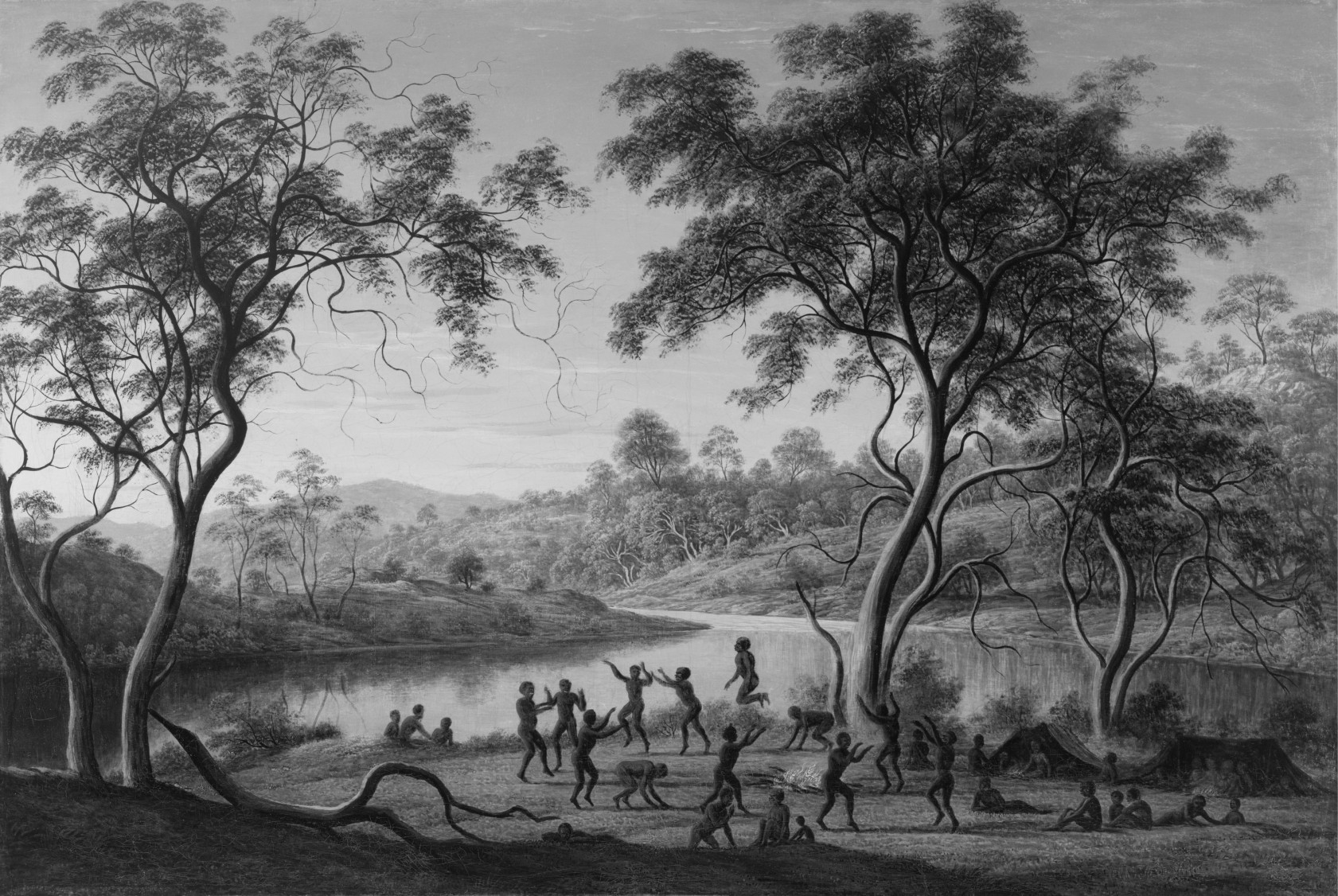

7. Natives at a Corrobory, under the wild woods of the Country [River Jordan below Brighton, Tasmania], ca. 1835 / John Glover © Mitchell Library. State Library of NSW – ML 154

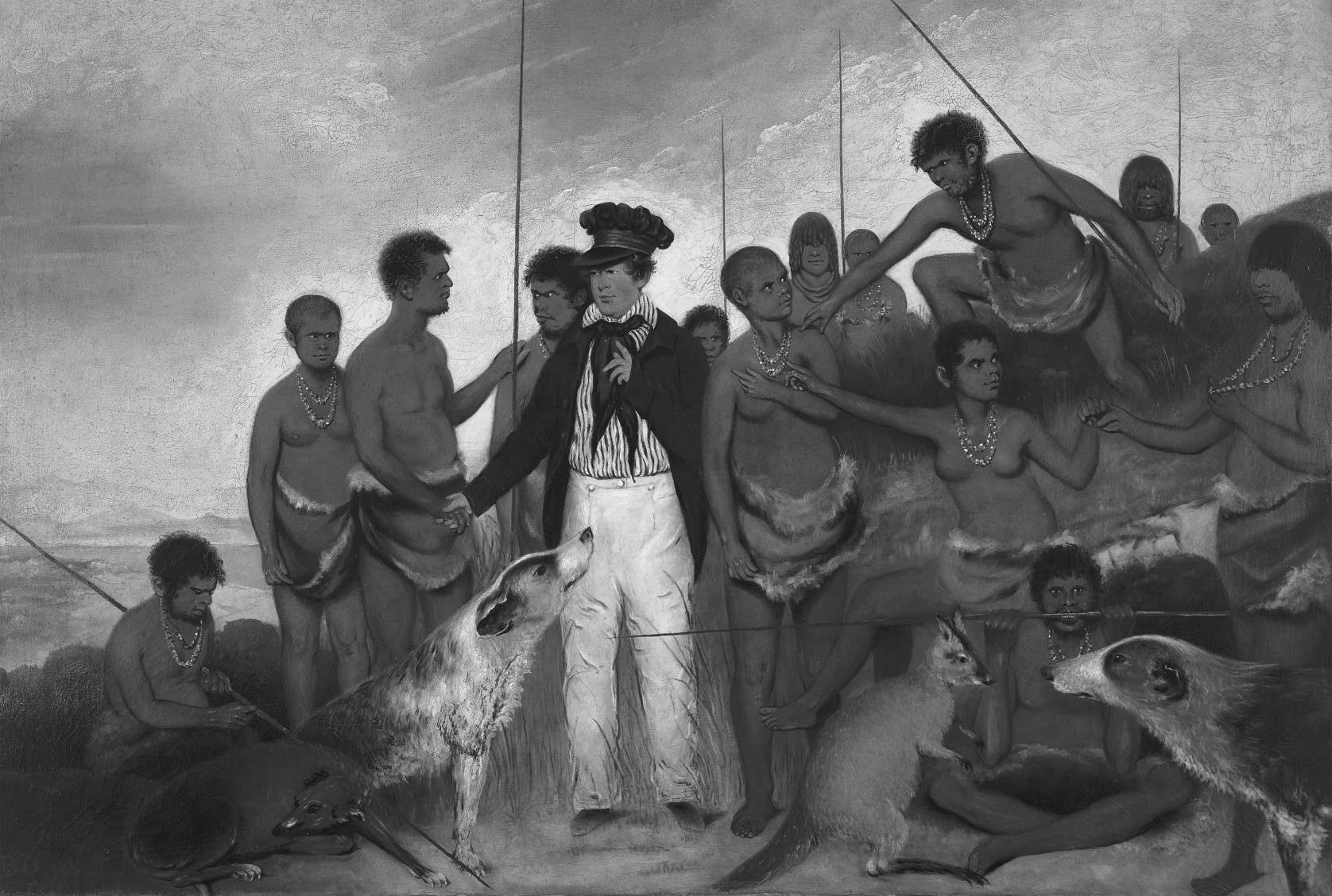

8. The Conciliation by Benjamin Duterreau © Tasmanian Museum & Art Gallery

Acknowledgements

I am writing these acknowledgements on Flinders Island, as part of an ongoing research project into how the events described in this book are remembered. It is extraordinarily beautiful and utterly peaceful. It has certainly aided my understanding of the subject. While it is a wonderfully tranquil, indeed serene, place, I also feel rather uneasy here. I am as far from home as I have ever been. My mobile phone does not work and the place where I am staying has no internet connection. I feel somehow displaced and disconnected – too far away from the places and people I love. In some senses, I am, I guess, afraid. While this is a very modern, and utterly self-indulgent, form of fear, I feel it nonetheless. I wonder how far some of the violence that is described in this book was born of a much more profound fear, a sense of disconnection and displacement in a world in which the physical and temporal distances from home were so much greater.

The peace of Flinders Island also enables me to reflect on the various debts I have accumulated in the research and writing of this book. It was entirely written while I was at the University of Winchester, an institution I leave next month, after 11 years. I owe many people there a great deal. It has been a privilege to work with and for Kris Spelman Miller over the past four years, and her support for me and for this project has been crucial. I am similarly grateful to Liz Stuart. In the History department there have been difficult times, but Mark Allen and Colin Haydon have always provided friendly counsel. As did Neil Murphy, in whose office the title of this book was first articulated. Thanks also to Neil Messer and Jo Pearson, who helped me in drafting the application that secured a British Academy Mid-Career Fellowship in support of this project. I was very proud of this award, and my thanks go to the British Academy for the faith shown in me.

As you will read in the book itself, this project really began with an edited collection titled The Memory of the Holocaust in Australia. I am especially grateful to my co-editor on that book, James Jordan. Not only is James a great colleague in all that we do together but he is also a good friend. I would not have made my first long trip to Australia without James and as such would probably never have embarked on this research at all. It was also with James that I met for the first time a group of people in Australia who have been incredibly warm and welcoming on each of my subsequent visits, and whose friendship it has been a pleasure and a privilege to enjoy. Suzanne Rutland, Konrad Kwiet, Mariela Sztrum and in particular Avril Alba have sustained me with their company on numerous occasions – on every one of which I have laughed more than anyone can reasonably expect to. I am especially grateful to Avril, who has become a good friend. Our apparently unending culinary tour of Sydney has been great fun.

Ann Curthoys and John Docker have also both offered good company and critical support. Dirk Moses and Damien Short equally provided crucial advice at important moments, as has Donald Bloxham. I am also very grateful to scholars whom I have never met, but without whom this project would have been impossible. I am thinking here especially of Lyndall Ryan and Henry Reynolds.

Many thanks to all of the people who have shown me round archives, and who have taken the time and trouble to discuss the project with me and locate records for it. Len Pole at Saffron Walden and Tony Eccles at the Royal Albert Memorial Museum in Exeter were especially helpful. Thanks also to Margaret Clegg at the Natural History Museum and to the University of Edinburgh for providing important material and perspectives for the chapter on the return of human remains. Thanks also to Patrick Scarff who worked as a research assistant at the very outset.

I am very grateful to the anonymous referees for their critical appraisal of the original manuscript – it is much better for that process. At I.B.Tauris Jo Godfrey has been supportive throughout and Alex Middleton has been a genuinely brilliant copy-editor. Thanks also to my dad for reading through the manuscript. As ever any remaining mistakes are all mine.

Thanks to Tony Kushner and all the rest of the Cavaliers, and to Simon Payling, whose company has made watching Arsenal more pleasurable than it might have been over the last few years.

And finally, to my family – no amount of thanks is enough. My wife, Elisa, has provided the space for me to write this book, and has brought up our children while I did so. Thank you, my love. Thanks also to all of those people who help Elisa with the children, especially when I am away, particularly her mum, Arlene Robinson, my mum, Linda Lawson, Judith Payling, Richard Levett and Vic Nicholas.

This book is dedicated to my children, Arthur and Florence. I am sorry that I have been away so much and so often over the last few years, and that I have been so grumpy when I have been at home but have been working. I love you both with all of my heart and I hope you will be pleased to see your names at the front of this book. Perhaps one day you will read it.

The book is also dedicated to the memory of my father-in-law, Doug Robinson. Doug died after a short but incredibly brutal illness at the beginning of 2011. He is greatly missed. It is a source of enduring sadness for me that Arthur and Florence will not have the privilege of knowing him as they grow up. For my part, I will make every effort to ensure that they remember him as he was: their wonderful granddad.

Introduction

From Thinking about Britain and the Holocaust to Writing about Genocide in the British World

This book is the product of an intellectual journey that began not in thinking about Australian or Tasmanian history, or even the history of the British Empire, but with the history of the Holocaust and its contexts. I am primarily a Holocaust historian – I have written and edited several books in Holocaust studies, and much of my teaching is concerned with the destruction of Europe’s Jews and its legacies. How I got from there to thinking about the role of genocide in the British Empire requires at least some explanation, especially because without it, it might be assumed that I am suggesting some broad equivalence between these two very different histories. I am not, but it would be disingenuous not to admit that it was thinking about the Holocaust that brought me to the study of an instance of genocide in the British Empire.

My foremost concern in Holocaust studies has been with the ‘bystanders’. Questions about how Britain responded to the Holocaust were the first that I tried to answer, both in terms of specific institutional and intellectual responses to Nazi anti-Jewish policies, and in terms of imaginings and memories of the genocide of the Jews that abounded in postwar Britain. And it was one of the central questions of the study of the ‘bystanders’ that ultimately led me to this book. It is often proposed that one of the reasons that the outside world had such difficulty in responding to the Holocaust was that the Nazis’ genocidal policies were beyond the imagination, that the notion of racial extermination was so alien to external observers that, to put it crudely, they simply could not believe that the reports emanating from German-dominated Europe were true. As I grew more and more aware of the monotonous regularity of racial violence, especially in the modern world, and indeed the destructiveness of the British Empire, it seemed to me that this assertion was not quite historically literate. As such, one of the motivations for my researching Tasmania in the first instance was to be able to place the history of British reactions to the genocide of the Jews more squarely within the context of responses to mass violence and genocide across a much wider chronology.

Added to this, in recent years in particular I have been concerned that a preoccupation with the memory of the Holocaust in contemporary Britain has become counterproductive. It has not become, as many campaigners for greater awareness of the Holocaust assumed it would, a prompt to self-reflection about the past, but instead a terrain in which some British national myths – of eternal tolerance, of the country as a haven for the persecuted, for example – are being further reinforced.1 Instead of undermining the stable rituals of historical memory, Holocaust memorialisation has itself become ritualised and, rather than challenging, safe. Indeed in many ways it appears that Holocaust memorialisation is being fed more and more into ideas of British national pride, and is being used as an example of the inherent dangers of any alternative to our liberal-democratic selves. This was particularly so with the egregious invocations of the Holocaust in justification of some of Britain’s military adventures at the beginning of the twenty-first century.2

These concerns did not lead me to think specifically about genocide in the British world until a first encounter with Australian history, which in many ways transformed my academic life. Again, this came through the lens of Holocaust studies. In 2008 I put together a collection titled The Memory of the Holocaust in Australia with my friend and colleague James Jordan. In that book we made no pretensions to be experts in Australian history, but used it instead to explore questions surrounding the global memories of the Holocaust in a specific and unfamiliar context.3

What our book lacked, however, was enough reflection on one of the particular contexts for Holocaust memories in Australia – the interaction (or otherwise) between the memory of the Nazi genocides and the genocides of indigenous Australians in the nineteenth century and into the twentieth.4 I felt this absence particularly acutely when we launched the book at the Sydney Jewish Museum and I witnessed for the first time the acknowledgement of Aboriginal dispossession that precedes all public events in Australia. It was while reflecting on our failure to do justice to that context – to explore fully how memories of the Holocaust interacted with memories of colonial genocide – that it began to occur to me (although the connection may have been entirely obvious to others) that this might have implications for my understanding of British history, and British Holocaust memories. Although Australia represented a specific site of genocide, it was a part of the British world, and as such genocide in Australia meant that such an atrocity was part of British history too. This is especially true when one considers genocide in Tasmania, which took place almost exclusively under direct British rule, and was committed by British colonists and settlers who were working either for the British Crown or for British companies, and who moved between Britain and the Antipodes. As such it occurred to me that the idea of racial violence and even extermination might be rather closer to home than either studies of the Holocaust and its contexts or the rituals of modern memory implied.

At first these observations led me to plan a book on Britain and genocide in the modern world – which would have begun by looking at genocide inside the British Empire, which in turn would begin with Tasmania. The Last Man is the product of the research for what I planned to be the first chapter of the Britain-and-genocide project. As the research developed it became increasingly clear that the interactions between genocide in Tasmania and British history were so intricate, multi-layered and long-standing that that case alone demanded a specific book. What follows considers the role of the British state in the genocidal destruction of indigenous Tasmanians.5 It goes on to consider the echoes of that destruction in British culture, right up to the present day.

But the profound links that I write about in this book between the British past and the history of genocide are difficult to discern in our present. This is true when you observe both historical investigations of genocide in British Australia, and more general interactions with the idea of genocide (which usually means the Holocaust) in British culture. While the allegation that genocide occurred in Australia has caused and continues to cause paroxysms in Australian academia and politics, such ‘History Wars’ have been observed with detachment in Britain, as if it were very little to do with ‘us’ somehow. That the issue of genocide in Australian history has been so politically charged there is precisely because it has mattered so much – raising existential questions about Australian identity about what it means to be Australian. Yet somehow the existence or otherwise of genocide in the British world seems to cause no such angst within Britain itself. Indeed, as will be discussed later in this volume, that the idea of genocide in Tasmania can be discussed glibly by modern-day apologists for empire is evidence of how little the question of colonial genocide seems to matter in Britain today.

In Australia, too, scholarly debates about genocide often deliberately avoid detailed consideration of their implications for the British centre of the former Empire. Consider Henry Reynolds’s An Indelible Stain? as an example. The title of Reynolds’s investigation of the role of genocide in Australian history is taken from the text of a famous despatch sent by the Secretary of State for the Colonies in London,6 George Murray, to the lieutenant governor of Van Diemen’s Land, now Tasmania, George Arthur, in 1830. In it Murray demanded to know what was happening to the peoples of the island, ending with the following warning: that the ‘extinction’ of the indigenous population of Van Diemen’s Land would leave ‘an indelible stain’ upon the reputation of the British government.7 Reynolds takes up Murray’s challenge, stating that

the question that Murray’s words still confronts us with is whether our history has left an indelible stain upon the character and reputation of Australian governments – colonial, State and federal – and upon the colonists themselves and their Australian-born descendants.8

Yet George Murray had not himself been that interested in the moral implications of genocide for the colony, but for the metropole. The ‘indelible stain’ that Murray feared was, it is worth repeating, upon the reputation of the British government.

Thus this book asks the questions of Britain and the British past that Reynolds sought to ask of Australia – considering both the role that the British government played in the development of genocide in Tasmania and the wider role that genocide in Tasmania itself has played in British culture. In doing so, I hope it will fill a historiographical gap by considering in depth a case study of genocide in the British Empire.

But why Tasmania? The story of genocide there is well worn, much more so than, for example, genocide in Queensland or indeed the ‘continuing genocide’ faced by indigenous peoples in contemporary Australia.9 Much of the story I tell here will be very familiar at least to Australian readers. Surely the job of the historian should be to tread less well-worn paths to the past? In mitigation I would argue that while the history of genocide in Tasmania is well established, the role of the British government and the echoes of colonial genocide in British culture are not. Furthermore, this is a book for the present as well as the past, and it would be much easier for Britain to avoid confronting genocidal collisions with indigenous peoples in the 1850s and 1860s, because they occurred after the Australian colonies had become self-governing. Although the British state may bear much responsibility for the structural inequalities in the relations between white settlers and peoples in the colonies they established, it has recourse to an explanation for genocide as the sins of the errant sons of Britain rather than their metropolitan parents. This is not the case for Tasmania, where (notwithstanding the vagaries of colonial administration) Van Diemen’s Land was under the direct rule of the Crown during almost the entire period in which the indigenous population was rapidly declining.

What is more, the sheer fact that the story of genocide in Tasmania has been so well worn in Britain from the 1820s onwards is itself of crucial importance. The ‘Black War’ between colonists and the indigenous peoples of Van Diemen’s Land, and the idea that the latter had been exterminated, was culturally significant in Britain during the nineteenth century and has remained so since, albeit somewhat less prominently. Indeed this book seeks to demonstrate that this is a genocide that has become part of British identity. As such understanding how it is that identity-building in Britain has incorporated genocide is crucial in order to uncover the degree to which Britain is itself a post-genocidal state and society. This is therefore not a book about Tasmania but about Britain. While in the process of writing it I have learnt much about Tasmanian history, my aim has been to learn about the British genocidal past.

But as I have already said there is little or no acknowledgement within a wider memorial culture today that Britain has such a genocidal past, or that Britain is in effect a post-genocidal state. Indeed there is an overwhelming tendency to represent genocide as a crime committed only by others. Self-evidently the genocidaires of the Holocaust were, for example, the enemies of Britain, and liberal democracy is often represented as the alternative to genocidal regimes. Perhaps the best example here is the Imperial War Museum in London, a place in which British military success is remembered and celebrated. Yet at the same time it also contains an exhibition about the Holocaust. It is difficult to avoid the impression that the Holocaust exhibition exists in this context to present a worked-through example of the alternative to British liberal democracy. Such an impression is further embedded by the accompanying ‘Crimes against Humanity’ exhibition, which sets the Holocaust in the context of the history of genocide. Yet within that history there is no mention of Britain’s imperial crimes (although there is engagement with the crimes of, for example, the German Empire in South West Africa).

In contemporary British culture then, genocide can be made use of in the celebration of being British. This book is a warning against that tendency – it seeks to demonstrate how genocide is part of British history rather than suggest that British history simply offers alternatives to genocide. It is therefore a book that has a live political purpose, which asks that Britain confront the implications of its genocidal past, rather than continuing to wallow in a genocidal past in Europe. This is not in any way to fall prey to the temptation to say that the Holocaust is not part of British history – its entanglements with Britain are many and profound. Instead it is to say that an understanding of the Holocaust has allowed us to see more clearly the moral imperatives of genocide, and as such it behoves us to ask awkward as well as comforting questions of our national past too. In a world in which politicians and others often suggest that we should turn to Britain’s imperial past for our historical narratives, this book serves as a reminder that some of the most cherished national assumptions about that past – about our liberal selves – disguise a darker history, which failed absolutely to recognise and cherish the diversity of mankind.

One

Defining Terms

The earliest traces of the inhabitants of the island that we call Tasmania are some 40,000 years old. At least 8,000 years ago the island was cut off from continental Australia by the flooding of the Bass Strait. Remarkably, indigenous Tasmanians in the nineteenth century reported that their ancestors had walked across the land before the flooding – suggesting a folk memory or legend that had endured for more than 300 generations.1

In the very latter stages of this deep history, in 1642, the Dutch explorer Abel Tasman named the island, which was known to its inhabitants as ‘Trouwunna’, ‘Van Diemen’s Land’.2 The next Western visitor to the island arrived in 1772, beginning a flurry of activity that ended in the creation of a permanent British settlement in 1803 and 1804. In the meantime British men from New South Wales had begun an informal colonisation of the island, which included starting relationships with indigenous women. When the British formally established their base, there were several thousand indigenous people on the island in as many as nine different nations. When the colony was awarded self-government by the British just 53 years later, there were officially just 17 of those inhabitants or their descendants still alive, although many more lived beyond the official gaze. Nonetheless, Tasmania had witnessed a calamitous population decline, one that had been the direct result of the British presence on the island – indigenous peoples had been the victims of settler violence and imported disease, before the relatively few survivors were rounded up and deported from the island. These survivors were settled on Flinders Island in the Bass Strait between Tasmania and continental Australia. There, unable to leave, the population were subjected to a crude campaign to transform them into ‘Europeans’ who cultivated the land and worshipped the Christian God. This new settlement witnessed a further, disastrous population decline. When one of the few survivors, William Lanne,3 died in 1869 it was declared in Britain that the ‘Tasmanian race’ stood on the edge of extinction. For he was ‘the last man’, survived only by two women, Mary Ann Arthur and Truganini. Mary Ann died in 1871 and Truganini in 1876. After the latter’s death, it was universally declared that the Tasmanian population had been entirely wiped out.

Claims of total destruction completely ignored a mixed-race community concentrated on Tasmania’s outlying islands, and a number of mixed-race children living in white-settler homes. The former was the product of the original informal colonisation of Tasmania. It would not only survive but flourish across the nineteenth and twentieth centuries to form the basis of the Tasmanian Aboriginal community today.4 But if the destruction of their ancestors was not total, it was comprehensive. All original communities had been destroyed since the British invasion, and the population reduction was greater than 99 per cent. This was a British genocide, carried out on the other side of the world by British men, articulating British ideas, discussed in British newspapers and ultimately embedded in British history and remembered in British museums.

A British Genocide

The British settlement had been established to forestall any French claims to the island in the midst of the Napoleonic wars. Van Diemen’s Land was also a remarkably benevolent land. Its climate was much more temperate than that of its parent Australian colony, New South Wales. There were abundant supplies of game, which flourished in open pastureland close to the coastal areas, which were the first to be settled. There were equally abundant supplies of shellfish in the coastal waters. While at the time some imperial propaganda suggested that Tasmania had been a harsh, unforgiving land, which the colonists had to overcome, in fact what the first settlers discovered was a ‘veritable Eden’.5

Little thought was given to the indigenous population that had in fact shaped much of that environment.6 Both British and French expeditions to Van Diemen’s Land before 1803 had experienced encounters with the inhabitants of the island – but comparatively little attention had been paid to them. They were certainly not seen as a barrier to colonisation. Those accompanying Captain Cook in 1777, or d’Entrecasteaux in 1792, had noted only that the population seemed to pose little threat; they were ‘harmless and content; an extraordinary remnant of primitive innocence’.7 François Péron, historian of the French explorer Nicolas Baudin’s expedition to the island in 1802, had been repulsed by the ‘savage hordes’ he encountered, but had agreed with earlier observers that that they were not threatening.8 No such extensive descriptions of the existing population were offered by the first British settlers, but if they considered these people at all,9 the British assumed that they could recruit them in the process of developing the island – in the first instance as a penal colony. Indeed the first authorities in the British colony were instructed to treat the ‘natives’ with ‘amity and kindness’ in order that they too might share in the benefits of colonisation.10

Probably the most eloquent indication of how little impact indigenous populations had on the British mind or that of other European colonisers was the widespread belief that their land was vacant and thus ripe for possession. Of course, the British did not believe that the land was literally uninhabited. But, in a concept that became known as Terra nullius (‘land that belongs to no one’) by the end of the nineteenth century, the British and other European powers understood that continental Australia and Tasmania represented so-called ‘wastelands’. As such, because indigenous Australians did not operate any formal laws of property, and indeed because they did not exploit natural resources through farming in a manner that the British could recognise, it was assumed the land was essentially empty. The British thus concluded that they could declare ownership of that land, and sovereignty over its peoples.11

In fact the nine nations in Tasmania had a complex relationship with their country. The land was managed to support the main sources of food (for example, grazing pasture was created by fire), and clans moved across the country according to where the food supply was most abundant at different times of the year. Movement across the land does not mean, however, that there was no sense of property: the clans (which made up a nation) had a clear understanding of the demarcation of their territory, although not the exclusive ownership of it. In the most comprehensive survey of indigenous communities and their social relations, Brian Plomley identified some 48 different clans at the time of the British invasion with specific territories, although Lyndall Ryan argues there may have been as many as 100.12 It is difficult to be precise because all of these functioning communal units were destroyed by the British.

Because of that destruction, we simply cannot know exactly how large the existing population was in 1803, but the most recent speculations suggest that it could have been as high as 8,000, and that it was rising.13 Certainly it massively outnumbered the original settlers and convicts, of whom there were just a few hundred spread across three main settlements.14 Contact between the very small settler population and indigenous peoples was necessarily very limited – in effect the British mainly occupied a small enclave in the south-east corner of the island in the first months of occupation. Although we know that those nations located on the sites of settlement watched the British arrival carefully, much of the population on the rest of the island may have been oblivious to the British presence for some time.15

Although contact between the British and the inhabitants of Van Diemen’s Land was limited at the beginning of the settlement, it was very quickly lethal. As Lyndall Ryan writes: ‘from the outset the British in effect were trying to eliminate the Aborigines by killing the parents, abducting their children and transforming them into white people.’16 The killing of indigenous people in defence of the expanding settlements and farmlands was tacitly accepted by the colonial authorities.17 And although the documentary evidence is scarce, it appears that at least until 1808 the new colony was defined by violence between settlers and indigenous nations, especially over control of land that supported game such as kangaroo.18 Those groups that inhabited the lands on which the towns of the new colony were established seem to have been devastated. According to Lyndall Ryan, ‘The Mouheneenner clan, whose territory included Hobart, experienced massive population decline in this period.’19

After 1808, however, a period of calm and indeed coexistence seemed to descend on the colony. As the rate of colonial expansion stabilised, conflict between settlers and indigenous Tasmanians subsided. Indeed, it is possible to argue that between 1808 and 1820 a Creole society was created: a ‘potent mix of cross-cultural, economic and sexual interaction’.20 As well as the European–indigenous relationships in the seal-hunting communities, groups of islanders could for example be seen in the settlements looking for food. At the same time, more and more indigenous children were taken into white homes, and some were even sent to England to be educated. The practice of taking children suggests that any coexistence came with little respect for local culture, and indeed those who served as domestic servants were in effect being used in a form of slavery.21

By the end of 1819 the indigenous and colonial populations were roughly equal in size. Yet that parity meant that each population was 5,000 strong, and as such we should not underestimate the immediate demographic impact of colonisation. In the first 15 years of settlement, the indigenous population declined by more than 30 per cent. Indeed, in 1819 Governor William Sorell told of an enduringly violent relationship on the Tasmanian frontier, where attacking the island’s peoples had become habitual. We can only speculate as to the numbers of casualties.22

After 1819, however, there is no doubt that colonial Van Diemen’s Land was defined by violence. Massive population and territorial expansion in the 1820s not only increased settler attacks on indigenous peoples, but also drove the latter to resist settler expansion more actively. In the same report in which Sorell had referred to habitual violence on the frontier, he had predicted that expansion would lead to more attacks on settlers and their livestock, and he was right. During the 1820s and especially after 1824 Van Diemen’s Land was the site of a war for control of the land. At some points during this ‘Black War’ (as it was known at the time), colonial authorities believed that indigenous violence jeopardised the very existence of the colony. It certainly threatened to derail any further development, as individual settlers claimed they were unable to defend the frontier without military assistance.23

From November 1823 onwards the indigenous population fought back with increasing success, and a spiral of violence ensued. Between the warring communities sat a colonial government instructed by London both to protect the original inhabitants of the island and to defend the colony from depredation. Such instructions were deliberately contradictory, and tell us a great deal about the priorities of the London government with regard to its Empire. Ultimately the security of its territorial settlements took precedence over the lives of the original owners of the land on which those settlements stood. As a consequence, the colonial government, then under Lieutenant Governor George Arthur, pursued a series of measures that by 1828 amounted to war with the indigenous population, after a declaration of martial law in the colony. The ‘Black War’, which saw both licensed and unlicensed forces pursuing indigenous populations, who themselves continued to attack settlers and their livestock, continued until the end of 1830. It ended with a spectacular show of strength from the colonial authorities when almost the entire settler population was militarised and attempted to confine the clans in a corner of the island. This action, known as ‘the Line’, was a miserable failure, in part because by then the number of indigenous Tasmanians was so small. It is not clear how many were killed directly at British hands during the conflict, with British weapons, but Lyndall Ryan can account for approximately 800 deaths on the Tasmanian frontier.24 We can assume that much violence went unrecorded too. As James Boyce argues, the conflict was much better documented after it became formalised in 1828, but by then most indigenous Tasmanians were already dead.25

The decline in the island’s original population was precipitous and by 1831 there were only a few hundred survivors. This had been matched by an equally steep increase in the British population. The survivors were for the most part collected together by George Augustus Robinson, who himself had emigrated to Hobart, the capital of the Tasmanian colony, at the beginning of the 1820s. Robinson was employed by the colonial government to ‘conciliate’ the antagonistic indigenous population from 1829. In that role Robinson, and a group of indigenous guides on whom he relied, eventually brought together the vast majority of the surviving members of the clans. He brokered their peace with the colonial government and eventually arranged for their removal en masse (you might call it deportation) to Flinders Island, which was separated from the north-west coast of mainland Tasmania by some 40 miles. There, in a settlement known to its inhabitants as Wybalenna, the population was beset by disease. Although it would be wrong to characterise the settlement as a place of decline, and descriptions of it as a concentration camp or gulag are unhelpful, it is impossible to escape the view that the efforts to transform and ‘civilise’ indigenous Tasmanians that were enacted there had calamitous consequences.26 By 1847 there were just 47 people remaining in the community on Flinders Island. In little more than a generation the original population had been reduced by 99.5 per cent.

One of those surviving on Flinders Island was Truganini, a woman who had been with Robinson since he first took control of an ‘Aboriginal establishment’ on Bruny Island in 1829. Truganini and the other survivors were sent back to the Tasmanian mainland in 1847. She was the last of that community to die in 1876. At that point it was widely declared that the indigenous population of Tasmania had been wiped out. As I have said, such a claim ignored the existence of a mixed-heritage community both in Tasmania and on other islands in the Bass Strait, but it articulated a widespread sense of the superiority of the British. The Empire was, it was assumed, so powerful that it had swept an entire people out of existence.

The book that follows attempts to tell a version of the story of the violent dispossession and deportation that I have summarised here. However, its focus will not be the indigenous victims of the process, but the British forces which shaped it.

Histories of Genocide in Tasmania

This book is certainly not the first history of genocide in Tasmania. In fact, histories that identify that indigenous Tasmanians were the victims of a deliberate campaign of extermination pre-date the working through of the concept of genocide by more than a century. Henry Melville, a Hobart newspaper proprietor, wrote of the ‘war to the knife’ between settlers and indigenous islanders in his History of the Island of Van Diemen’s Land in 1835. Melville’s tale of ‘destruction’ was specifically aimed at implicating the colonial government in a campaign that ‘swept’ ‘populous tribes […] from the face of the earth’.27 John West’s History of Tasmania, one of the foundational texts of Australian historiography, confronted the destruction of the indigenous population directly in the early 1850s – describing it baldly as an example of ‘systematic massacre’.28 West lamented the ‘fate of the Aborigines’, and described their ‘tread[ing] […] to the dust’ as a calamity that ought to ‘check exaltation’ at the triumph of colonisation. His History was part of a campaign against the system of transporting convicts to Van Diemen’s Land and as such alleged that genocide had been the result of Britain’s export of her most depraved sons to wreak havoc in the New World.29

Both West and Melville wrote about the destruction of the indigenous population for an audience in Britain, in order to draw attention to the politics of colonisation. Later in the nineteenth century James Bonwick, who had been a schoolteacher in various parts of continental Australia, wrote the first history of the decline and destruction of the indigenous community, The Last of the Tasmanians, which was again directed at a British audience and again had a political purpose. Bonwick’s account became the classic narrative of destruction in Tasmania, and was particularly influential in informing anthropological investigations of what was then understood to be the extinct Tasmanian population at the end of the nineteenth century. Bonwick’s aim was to ensure that other indigenous peoples throughout the world were preserved.

In the aftermath of World War II, Tasmania was often identified as one of the sites of the newly recognised crime of genocide. The author of the idea of genocide, Raphael Lemkin, who was also largely responsible for its codification in international law, included the Tasmanian case in his projected history of the concept. Lemkin’s account of genocide on the island was largely based on Bonwick’s work. At a similar time Clive Turnbull identified the ‘extermination of the Tasmanian Aborigines’ as the key element in the colonisation of Van Diemen’s Land, a microcosm of the relationship between conquerors and indigenous peoples throughout the history of European colonialism.30 The idea that genocide in Tasmania was a kind of British ‘Final Solution’ also became embedded in critical histories of the British Empire in the postwar period – betraying the interaction between a perception of the murder of Europe’s Jews and the understanding of colonial violence.31

Because Raphael Lemkin included it in his survey of genocide and because it was (outside Tasmania and Australia) almost universally assumed that the destruction of the indigenous population had been total, Tasmania is frequently included in general surveys of genocide in the modern world.32 Yet Henry Reynolds has argued that this can often be the result of an almost reflex action, based on little understanding of the particularities of Tasmanian history. In particular, the insistence on the totality of extermination that is sometimes contained within these accounts is in some ways a perpetuation of colonial thinking about the nature of the indigenous community and its relationship with colonial authority. The idea that all of the original Tasmanians had been exterminated not only ignores the endurance of an indigenous community on the island, but subscribes to a racialised imagination that assumes that the children of mixed-race relationships in Tasmania were somehow rendered ‘white’ by the blood of their fathers. Moreover, the story of genocide itself – which often suggests that the helpless islanders were the passive victims of the all-powerful white settlers – is to perpetuate a colonial discourse that denies the possibility that indigenous communities were agents in their own history after the arrival of white Europeans.33 Such a view ignores the fact that much of the violence was the result of indigenous efforts to defend their land.

As a consequence, the most recent accounts of genocide in Tasmania (although not all would accept the use of that term) have been contained within what might be described as post-colonial Australian histories. Scholars have particularly sought to draw attention to the survival of some indigenous Tasmanians – in part bringing historical narratives in line with the assertive contemporary politics of the Tasmanian Aboriginal community. In particular, such histories describe the active role played by the island’s existing communities in the conflict with settlers in the first three decades of the colony. In such a formulation, depopulation has been recast as the consequence of war between settler and indigenous communities, of active competition for the land rather than the result of the British men of modernity sweeping the island clear of the passive and helpless indigenes. The most modern historiography rejects the passive-victim thesis as essentially patronising,34 and asserts that indigenous peoples were the subjects rather than the objects of their own history.35 In rejecting the idea of the total extermination of indigenous Tasmanians as itself a colonial myth, such history points to the living vibrancy of the Aboriginal Tasmanian community and hints at the complexity of deploying the term genocide too.

It is not only in the assertion of indigenous agency that such histories of colonial Van Diemen’s Land present what might be called post-colonial narratives. In common with much ‘new imperial’ history, the contemporary historiography of Tasmania demonstrates that the Empire must be understood in the exchange between imperial authorities and the settler colonies or the societies they created. As such Van Diemen’s Land was not a society somehow transplanted from Britain by pioneering settlers who tamed a harsh and unforgiving land, but the product of interaction between the settlers, the land and the peoples that they conquered.36 This interaction included exchange with the existing population, and, as Lyndall Ryan has argued, histories that see only a destructive relationship between indigenous peoples and the British obscure the development of important Creole cultures that were the product of positive colonial encounters.37

Some of the most important recent histories have therefore been richly detailed local studies. These works set the story of population decline firmly in the communities and the landscape in which it occurred.38 And of course the local contexts for the history of genocidal conflict between indigenous and settler societies have a real and essential political dimension in the contemporary relationship between ‘white’ and indigenous Tasmanians.39 Yet one of the unintended consequences of this assertion of the importance of the local is that the metropolitan centre can be almost written out of the history of colonial Tasmania and its impacts on the island’s original inhabitants. For James Boyce, for example, genocide was a consequence of the specific local Tasmanian culture and took place despite the metropolitan British.40 For Lyndall Ryan genocide took place in a policy vacuum created by the British government’s lack of engagement with Van Diemen’s Land.41

Other histories, concerned more generally with indigenous dispossession in Australia, also tend to marginalise the metropolitan British. Henry Reynolds’s re-examination of the legal basis of settlement, for example, and his assertion that British colonial authorities did recognise the land rights of existing peoples (both in Tasmania and throughout colonial Australia), played a crucial role in Australia’s recent search for a more equitable settlement with indigenous communities.42 But again the interpretative consequence of this for British history is to distance the British government especially from the violence on which colonial rule so often depended. Reynolds argued that the Colonial Office in Britain, and certainly evangelical reformers who sought to influence Downing Street, held assumptions about indigenous rights that were the diametric opposite of any will to exterminate that might have been seen in the colonies themselves. In such a thesis the British are portrayed as the (albeit hapless) protectors of the indigenous community from the ravages of the settlers.

In what is the most comprehensive history of the tragedy that the British unleashed in Tasmania, which rejects the label genocide, Reynolds suggests that although policy towards indigenous peoples was confused and contradictory the British government was essentially the source of restraint – that in their entreaties against violence the British held back settlers who from the mid 1820s wished to destroy the existing population, who were attacking them in a war for control of the land.43 In doing so, Reynolds unwittingly found common cause with scholars engaged in a quite different historical and political project. Niall Ferguson, for example, wishes that his book Empire might rehabilitate the historical memory of British imperialism. Remarkably, he uses genocide in Tasmania as evidence in support of his case, arguing that the British attempted to prevent genocide there and succeeded in doing so on continental Australia. Ferguson describes ‘one of the most shocking of all chapters in the history of the British Empire’ in which ‘the Aborigines in Van Diemen’s Land were hunted down, confined and ultimately exterminated’. Perhaps most remarkable is the significance that Ferguson ascribes to genocide in Tasmania:

All that can be said in mitigation is that, had Australia been an independent republic in the nineteenth century, like the United States, the genocide might have been on a continental scale rather than just a Tasmanian phenomenon […] one of the peculiarities of the British Empire was the way that the imperial power at the centre endeavoured to restrain the generally far more ruthless impulses of the colonists on the periphery.44

In such a formulation Britain is set free of the burden of genocide in its history. Colonialism and imperialism can be reclaimed as respectable political discourses. Genocide was carried out not by the British, but by colonists who had somehow betrayed their British heritage.

Such interpretations of the relationship between Britain and the violence in its colonies have long roots. The idea that colonial society was itself a kind of savage deviation from the noble traditions of British politics and culture was well established in the nineteenth century. Indeed the Colonial Office convinced itself that the devastating impact of colonial Van Diemen’s Land on the indigenous population was a result of a rejection of the essential tenets of British rule. As a consequence, some of the first chroniclers of the destruction in Tasmania argued that the ‘home authorities’ could be ‘exonerated’ from any charges with relation to the treatment meted out against indigenous peoples by the settlers.45 And even the most challenging histories of the colonial experience have long asserted that the devastating consequences of imperialism can be explained by the idea that colonial outriders were somehow set free from the control of metropolitan Britain.46

The story of genocide as a consequence of British actions has not therefore been comprehensively explored. It is not that historians haven’t suggested that genocide in Tasmania is linked to British history – that would be absurd – they have just not fully worked through the implications of such arguments. John West’s History of Tasmania played into that cultural separation of the savage settler from the respectable British. He excoriated the British practice of transporting convicts. But at the same time he linked violence against indigenous Tasmanians to wider currents in British history. West stated clearly that the British government was ‘remiss and culpable. The crimes of individuals, without diminishing their guilt, must be traced to those general causes which are subject to the disposal of statesmen and legislators.’47 In the post-colonial world several scholars, and indeed politicians, have loudly asserted British responsibility for genocide in Tasmania, but not gone on to explore the interactions between action and policy and the intentions of, for example, the British Colonial Office.48 The then prime minister Paul Keating’s efforts to reappraise Australian history and confront responsibility for the ‘evils of colonialism’ in the late 1980s and early 1990s transferred much of that responsibility to the ‘imperial master’.49 More recently, even those historians cited above as contributing to the sense of a gulf between genocide in Tasmania and British policy have referred obliquely to the wider links between violence and the centre of empire. Lyndall Ryan suggested that British colonial policy was the root of the destruction of Tasmania’s indigenous community, but offered no detailed analysis of how the British government interacted with policy towards indigenous groups in Tasmania.50 And Henry Reynolds also recognised that the original impulse for violence must be traced to Britain and the ‘colonising venture’ itself, again without fully exploring such an idea.51

What follows will attempt to flesh out that relationship between Britain and genocide in Tasmania. I will argue that genocide was the result of the British presence in Van Diemen’s Land. This does not mean that the British government or its agents explicitly planned the physical destruction of indigenous Tasmanians. They did not. But genocide was the inevitable outcome of a set of British policies, however apparently benign they appeared to their authors. I will show that those policies – even those aimed at protection – ultimately envisaged no future whatsoever for the original peoples of the island. The specific policies that led to genocide may well have been made in Tasmania by the colonial authorities and the settlers, but they were approved by His Majesty’s Government in London, reported in the British press and ultimately responded to the desires and demands of a British colonisation.

Furthermore, The Last Man will demonstrate that the links between Britain and genocide in Tasmania do not travel in only one direction. It is not just that the destruction of indigenous Tasmanians and their culture was the consequence of British politics, but that it had an impact on British politics and culture too. What follows will show that genocide in Tasmania has been a shadowed presence in Britain since the 1820s, which at times breaks the surface of public discourse right up to the present day. For example, the debates about the origins of mankind in the mid to late nineteenth century and those about the return of human remains stored in British museums to indigenous peoples across the world in the late twentieth century relied heavily on the idea of genocide in Tasmania and both demonstrate the links between genocide and the articulation of certain identities in Britain today.

On Genocide in Australia

The idea that what occurred in colonial Tasmania should be labelled genocide is, as seen earlier, contested. Henry Reynolds’s investigation of the issue in Australian history concludes explicitly that the demographic disaster precipitated by the British in Tasmania did not amount to genocide. Focusing on the concept of intent, Reynolds argues that we can find no evidence that the British deliberately planned the wholesale destruction of indigenous Tasmanians and therefore that what occurred does not meet the definition enshrined in the 1948 UN convention, which codified genocide as ‘acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group’. In part because the British in Tasmania so frequently employed the rhetoric of protection, Reynolds concluded that there was no ‘intent’ to destroy and thus no genocide.52

It is the apparent absence of an explicitly and generally murderous intent that has made the question of genocide in Australian history so controversial. Witness the reaction to the 1997 report Bringing Them Home by the ‘National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from Their Families’, which was commissioned to investigate the practice of forced removal of children from indigenous communities, especially those of mixed heritage, by Australian states up to the 1960s. It concluded that there was enough evidence to suggest that the purpose of removing children was the cultural eradication of those communities: ‘when a child was forcibly removed that child’s entire community lost, often permanently, its chance to perpetuate itself in that child. The Inquiry has concluded that this was a primary objective of forcible removals.’ As a consequence, it devastatingly suggested, ‘they amount to genocide.’53

Reaction to the report from the conservative right wing in Australia was predictable. Critics of the ‘black armband’ view of Australian history54 poured scorn on the attempt to locate genocide in the Australian past. Most famously, Keith Windschuttle produced The Fabrication of Aboriginal History (the first volume of which was concerned with Tasmania) in order to deny, at length, that indigenous dispossession could be labelled genocide. The most recently published volume in Windschuttle’s trilogy denies not only the allegation of genocide but even that there was a policy of child-removal and thus a ‘stolen generation’ at all. The debates that Windschuttle’s work prompted crystallised into what have been dubbed Australia’s ‘History Wars’.55

Windschuttle’s rejection of genocide is easily and indeed politically explicable, but some of the criticism of the application of genocide to Australian history has come from less predictable sources. For example, Inga Clendinnen, a historian and anthropologist who was among other things a Holocaust scholar, wrote:

I am reasonably sophisticated in these modes of intellectual discussion, but when I see the word ‘genocide’ I still see Gypsies and Jews being herded into trains, into pits, into ravines, and behind them the shadowy figures of Armenian women and children being marched into the desert by armed men. I see deliberate mass murder.56

In doing so Clendinnen encapsulated many of the objections to the notion that genocide is part of Australian history, based on a sense not of what that history was but of what it was not. Indigenous dispossession may have been many things, Clendinnen seemed to be arguing, but it was not that. Or, to put it another way, Wybalenna, the ‘Aboriginal establishment’ on Flinders Island at which indigenous Tasmanians were confined and many of them died, may have been many things, but it was not Auschwitz.

Clendinnen famously went on to write evocatively about the first encounters between British settlers and indigenous Australians.57 But in her rejection of the term genocide she articulated an almost instinctive reaction in Australian politics and culture. The argument went something like this: genocide was only committed by Nazis or other totalitarian ideological warriors, not by ‘us’.58 In this formulation ‘genocide’ conjures up images of the Holocaust. Henry Reynolds operated a similarly narrow understanding of genocide as the Holocaust in his investigations. In this there was also common cause with the likes of Windschuttle, who argued that there was no will to extermination on the part of ‘the colonial authorities [who] wanted to civilise and modernise the Aborigines’. Again, the argument was that, as a consequence, there was no genocide.59

The implication of this critique is that genocide must look like the Nazi killing fields. Or at least it must look like a clichéd caricature of that ‘Final Solution’. The Holocaust, which such an understanding of genocide relies upon, was the result of a unified process, a specific plan of extermination, enacted in specific sites like Auschwitz. I have already made clear that Wybalenna was not Auschwitz. What is more, in the 30 years of the most violent interactions between settlers and indigenous nations in Tasmania, and more obviously across the two centuries of destructive interaction in continental Australia, there was self-evidently no worked-through and unifying aim of putting to death the existing communities on the part of ‘white settlers’, their descendants or the British, colonial or Australian governments.60 Thus, if one insists that in order to find genocide we must also find the avowed and unifying intention to exterminate all members of a single group, then we won’t find it in either Australia generally or Tasmania in particular. If genocide must look like the Holocaust (or at least a caricature of the Holocaust), then it indeed did not play a role in either the Australian or the British past.

We certainly won’t find genocide in relation to the entire indigenous community, or, to use the term that settlers would have used, the entire ‘Aboriginal’ community, of Australia either. That assumption, that ‘Aborigines’ were all part of a single ethnic group and culture, was itself born of a racist mindset – as I have said, in Tasmania alone there were nine different nations. Therefore, the idea that we can add up all of the murders of representatives of quite different nations across the vast continent of Australia and see a desire to exterminate, might itself be a perpetuation of the original colonial assumptions about the nature and essential similarity of indigenous societies.

That said, if we consider the individual nations in isolation then we might well be able to discern genocide more clearly – as there were obviously ‘genocidal moments’ in Australian history at which settlers and indeed the authorities sought to remove a particular group from a territory, and indeed did so using exterminatory violence.61 The deployment of the Native Police Corps in Queensland in the 1860s, when they were used to ‘disperse’ clans from particular territories and did so using mass violence, offers many examples of this practice.62 In Tasmania, the deliberate clearing of the North West clans from the territory of the Van Diemen’s Land Company towards the end of the 1820s was also in these terms an example of genocide – in that it had the clear goal of the eradication of a particular ethnic and linguistic group in a defined region.63 But, those who deny genocide in the Australian past would argue, even genocidal moments do not necessarily add up to genocide.

What the examples of Queensland in the 1860s and Tasmania in the 1820s also demonstrate is that if we consider genocide to be a state crime – and again the Holocaust draws us to that notion – then it might not appear to be applicable in the Australian case. Much of the violence in Australia was committed in apparent defiance of the state. Although they are few and far between, there are examples of efforts to punish the perpetrators of violence against indigenous peoples and communities on the part of the colonial and imperial state.64 Colin Tatz has argued in relation to the same problem that genocide in Australia might be best regarded as ‘private’. It was after all driven forward by individual settlers, rather than by either the colonial state or its metropolitan masters.65

Clearly there was no state project of extermination in either Tasmania or continental Australia, but this does not necessarily mean that we can find, as Henry Reynolds in effect does, that the state was not guilty of genocide or indeed that there was no genocide. After all, the lines between state and private action were not entirely clear. The violence on the Tasmanian frontier in the 1820s was in the service of a state-led cause – the project of settler colonisation and the creation of a new world. Dirk Moses and Mark Levene have argued separately that in those moments of violence we can see that the colonial project itself had a genocidal logic. It was not always evident, and indeed colonialism was spoken of in terms of protection and improvement. There was nothing approaching a ‘Final Solution’ that required, for its own sake, the extermination of indigenous Australians, but when communities resisted the colonial project exterminatory violence was unleashed66 – most notably, of course, in Van Diemen’s Land. Perhaps we ought simply to revise the idea of genocide as purely a state crime in the light of Australian history. After all, the frontier represented the most lethal theatre of violence in both Tasmania and later in Queensland and it was a space defined by the absence of the state.67

However, such observations still only pertain to extreme, indeed murderous, physical violence, something plainly not experienced by all indigenous Australians or even Tasmanians. This too might be evidence that the idea of genocide is not conceptually very useful in understanding the totality of the indigenous experience of the establishment of Australian colonies – because mass violence was just one form of dislocation that those peoples experienced.68 Even in Van Diemen’s Land perhaps fewer than 1,000 indigenous individuals met their deaths through violence on the frontier – although it is almost impossible to know how much violence has been forgotten as a result of the documentary deficit of an early-nineteenth-century colony in which the massacre of indigenous peoples was often kept secret.

Regardless of the deficiencies of the record, however, and indeed regardless of the precise role of lethal violence in the destruction of indigenous Tasmania, I am satisfied that it is both conceptually useful and morally correct to apply the label genocide to the British colonisation of Tasmania. This is not to say that this was a ‘genocidal moment’ within a more benign framework, but rather that colonisation itself amounted, in total, to genocide.

How, bearing in mind the objections cited above, can I assert this so confidently? For one thing, genocide does not refer only to lethal violence and nor does something have to look like the Holocaust to be genocide. Even if we are to use genocide only in a strictly legal sense then the authors of Bringing Them Home were quite right – the forcible transfer of children with the intention to undermine the viability of a community is defined as genocide in the 1948 convention. There is therefore no requirement for murder. But we must go beyond the formal legal framework – which after all was itself a compromised and imperfect articulation of the original concept of genocide.

As Dirk Moses has argued, Lemkin originally defined genocide as a ‘total social practice’. Crucially, this encapsulated the cultural undermining of the communal basis of a population group as well as any violence done. Lemkin wrote:

Genocide has two phases: one, destruction of the national pattern of the oppressed group; the other, the imposition of the national pattern of the oppressor. This imposition, in turn, may be made upon the oppressed population which is allowed to remain, or upon the territory alone after removal of the population and the colonisation of the area by the oppressor's own nationals.69

There is little doubt that colonial Van Diemen’s Land meets these criteria, and bearing in mind Lemkin’s cognisance of events in Tasmania it is not beyond the bounds of possibility that he had them in mind when formulating such an argument. After all, the settlement at Flinders Island, which sought to enforce different ways of living, farming and indeed believing on indigenous Tasmanians, was nothing if not an attempt to ‘impose the national pattern of the oppressor’.

That the British attempted to do this will become obvious as you read this book. The practice of child-removal that the Bringing Them Home report identified as genocidal was carried out in Van Diemen’s Land precisely with the aim of eradicating the islanders’ culture. The children who were removed were to be educated as white men. The removal of the indigenous nations from the land also enforced an explicit break from a shared past in Van Diemen’s Land that amounted to cultural destruction, and led to the Flinders Island settlement in which islanders were subjected to a crude process aimed at cultural transformation, further evidence of the destructive aim as well as effect of policy. Moreover, many British people who were disgusted by violence in Tasmania believed that it would only be by abandoning their way of life – the way they ate, the way they lived, their spiritual beliefs – that indigenous Tasmanians would have any chance of survival.

Therefore it is precisely because the idea of genocide offers us a framework through which we might unify many of the different approaches to indigenous communities that it is conceptually useful for understanding the history of the British in Tasmania.70 Some indigenous people in Tasmania died as at the hands of settlers who wished to exterminate them. Some died in the process of being removed from land that settlers wished to develop. Some died in the process of being removed from the land and ‘civilised’ into Europeans. Some died from warfare between the island’s nations that was prompted by their declining resource bases, a result of the British presence. Some died of imported diseases. And, of course, some survived, but with little or no access to a culture that the British considered worthless and had attempted to destroy. This happened over the course of a colonisation played out during more than 50 years. Perhaps, then, genocide is not a description of an event at all, but the identification of a set of events, a process or an epoch. This is something that is only retrospectively visible.71 And few could argue that the outcome of the British presence in Tasmania was anything but genocidal, with a population of several thousand reduced to a mere handful.

It is only the concept of genocide that captures the totality of a destruction that is not simply, to return to Inga Clendinnen’s point, defined by deliberate mass murder. In what follows you will find perhaps fewer references to violence than you might expect in a book on genocide. Indeed, you will find that much of the book is dedicated to a discussion of the commitment of both the British government and its colonial representatives to the protection of the indigenous community. But, I will argue, such a commitment to protection and the ‘progress’ of the island’s peoples was as much a commitment to eradication as the violence of the men on the Tasmanian frontier who openly practised and preached extermination.

But what about the role of disease? The British can hardly be held responsible for the ravaging of the indigenous Tasmanian population by diseases that the settlers did not themselves understand. It is not possible, for an epidemiologist let alone a historian, to delineate precisely the role that disease played in the destruction of indigenous Tasmanians and their communities. But we know, for example, that the precipitous decline of the population at Flinders Island was the result of disease rather than violence. As a result, it might appear that to label the Flinders Island settlement a site of genocide is illogical. Yet we also know that, perhaps knowingly, the British did introduce diseases into Australian populations. After all, the first contact with the people of what became Sydney led to a smallpox epidemic that devastated the community.72 We also know that the settlers were certainly aware that the indigenous communities were apparently unable to cope with infections that Europeans could easily survive. As a consequence, the British both in Tasmania and at home interpreted indigenous population decline as the result of a natural process. But even those contemporary readings of the disaster in Tasmania ultimately understood that it was the arrival of the Europeans that was its root cause. Indeed, some iterations of the idea that the island’s peoples were naturally slated for extinction relied on medicalised imagery – such as the idea that Tasmanians were destroyed by the ‘breath of our presence’. Yet there was nothing natural about, for example, the deportation of indigenous Tasmanians into the confined spaces of the Wybalenna settlement and their forced cohabitation with an ever-changing cast of Europeans. As we will see, the authorities were aware that Flinders Island was literally killing its community, but that did not, until it was too late, force them to reconsider the utility of an institution that was anyway designed to destroy at the very least indigenous culture. Although it might be to overstate the case, it is worth remembering that Jews who died of typhus in Auschwitz were victims of genocide just like those who died in gas chambers.

The logic of the British presence in Tasmania, and indeed on continental Australia, looked forward to and indeed demanded a future free of the original owners of the soil. It is only the idea of genocide, incorporating both cultural and physical destruction, that can fully capture the totality of the project to undermine and destroy indigenous populations and their culture. In this analysis, I follow what Tony Barta identified as ‘relations of genocide’, in which the only outcome of the settler-colonial project could have been the destruction of existing societies. What is more, the British government knew explicitly that it had unleashed a destructive process that would eradicate those societies.73 Its representatives disavowed, and indeed even regretted, the exterminatory impacts of their presence, yet they never faltered, never sought to roll back colonial development. Indeed, they even developed an understanding of the world that saw as inevitable the dying out of ‘inferior’ indigenous races.74

It is for these reasons that I believe that the term genocide is conceptually important and applicable in the Tasmanian case. Furthermore, I think it is even possible to identify a genocidal plan, and genocidal intent, thereby satisfying a more essentialist definition of genocide. Colonisation as a whole amounted to a ‘plan’ for a Tasmania, and indeed an Australia, free of indigenous peoples and their culture. This was a universal cultural assumption, it united protectionists and exterminationists, it was the common cause of the Colonial Office in Downing Street and the Tasmanian frontiersmen. Ultimately, there was among almost the entire British community a shared view that, to use Trollope’s memorable phrase, the ‘black men had to go’. The manner of their departure from history was contested, but there was a genocidal consensus that they had no part in the future. To put it another way, try imagining the colonisation of Van Diemen’s Land proceeding in a manner that provided the island’s original peoples with a future as inhabitants of Tasmania. Imagine if you like that those individuals committed to the protection of indigenous peoples had held sway, that disease had not destroyed the community held at Flinders Island. Is it possible to imagine a future in which indigenous communities flourished, practising their own culture and traditions? I would argue that it is not, because the avowed aim of colonisation was to destroy that culture and, at best, to save ‘savages’ from themselves.

It would, however, be intellectually dishonest to suggest that genocide is just deployed as an explanatory or conceptual device. There is a moral content to the accusation of genocide, just as there is to the rejection of the applicability of the word. Those who deny genocide in the Australian past do so in part because they do not wish to associate the Australian present with such an allegation. In international politics, the idea of genocide has a specific moral as well as legal force. Although the signatories to the genocide convention are not legally bound to intervene in reported cases of genocide, it is clear that various powers perceive that the moral case for their doing so will be greatly enhanced if a particular conflict can be labelled genocidal. Of course, this has had the regrettable impact of powers trying to avoid the use of the word in order to justify inaction – most notoriously in Rwanda in 1994.75 In the politics of history and memory it is clear that the label of genocide conveys a particular moral message – hence the Turkish government’s enduringly heavy-handed efforts to deny the Armenian genocide, and indeed other governments’ enthusiastic embracing of the idea that the Turkish state committed genocide.76 For victim groups, the label can also have a moral purpose – in that it appears to be the best way to articulate the depth of their suffering in any particular situation. Henry Reynolds reports for example the realisation of Wadjularbinna of the Gungalidda people of Northern Australia that she had been the victim of ‘barbaric acts of genocide […] a deliberate plan to deny me my true identity and try and destroy my place within a system of law and religion which connects me spiritually to the land, sea and creation’.77 With reference to Tasmania, it is only genocide that can capture morally as well as conceptually the sheer scale of indigenous dislocation.

Yet it is in the moral case for the use of the term genocide that we are confronted again with the problem of comparison with the Holocaust. There is no doubt that the moral force of the term comes from association with the Nazi genocides. It was during World War II that Lemkin articulated his conceptualisation of genocide, and it is the Holocaust that modern globalised memory has elevated as the defining example of that crime. It is precisely because of associations with the Holocaust, the ultimate atrocity, that Turks, Americans and, as we have seen above, Australians deny that genocide occurred in their pasts, and it is for the same reason that Armenians, Native Americans and indigenous Australians assert that they have been victims of genocide.

Yet I have already asserted that genocide in Tasmania was not like the Holocaust, and in historical terms it was not. But paradoxically I do believe that the moral associations with the Holocaust that it creates are another reason that genocide provides a more pertinent framework for understanding the indigenous experience of colonisation than less morally charged concepts do. While there is no workable historical comparison between the dispossession and extermination of indigenous Tasmanians and the fate of Europe’s Jews at the hand of the Nazis, there is a meaningful moral comparison.78 While revulsion at the Holocaust is in part about the methods and the scale of the murder, there is something more fundamental that was and is repulsive about the Nazi project. What the Nazis sought to do was nothing less than to remake mankind in their own image – their desire was therefore literally to control and transform what it meant to be human. This, it seems to me, as well as the scale of destruction, is why the Holocaust now appears as the ultimate atrocity. It is certainly why I was drawn to Holocaust studies. But in the realisation that the Holocaust – through an attack on Jews and Judaism – was another in a long history of attacks on the nature of humanity, one is led inexorably to the conclusion that other historical episodes pose a similar moral challenge. And one of these is the settler colonisation of Australia and Tasmania, in which the British elevated themselves as the representatives of all humanity and quite deliberately consigned indigenous peoples to the past.

As a consequence, it is possible that observations about the moral similarities between the British settler-colonial project and the Nazi genocides might also cause us to revise the assertion that there is no sensible historical comparison between the Holocaust and the genocide of indigenous peoples. There is no sensible comparison to be made if one works backwards from the Holocaust, that remains true. If we attempt to fit genocide in Tasmania and Australia into the model of the Holocaust then we will inevitably fail. But self-evidently the crimes of settler colonialism pre-date the Holocaust. If we reverse the question, and ask whether, looking forward from the crimes of the settler-colonial era (throughout the European empires), we can usefully fit the Holocaust into a wider history of genocidal colonialism, then the answer is, of course, yes. We might well learn something about the Holocaust too, as a form of colonial violence come home to Europe, by considering the history of genocide in settler colonies – be that the British in Australia or, for example, the Germans in South West Africa.79