After Old Europe collapsed, the dedication of copper objects in North Pontic graves declined by almost 80%.1 Beginning in about 3800 BCE and until about 3300 BCE the varied tribes and regional cultures of the Pontic-Caspian steppes seem to have turned their attention away from the Danube valley and toward their other borders, where significant social and economic changes were now occurring.

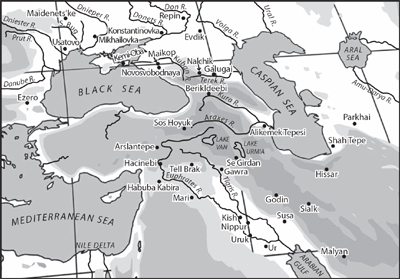

On the southeast, in the North Caucasus Mountains, spectacularly ostentatious chiefs suddenly appeared among what had been very ordinary small-scale farmers. They displayed gold-covered clothing, gold and silver staffs, and great quantities of bronze weapons obtained from what must have seemed beyond the rim of the earth—in fact, from the newly formed cities of Middle Uruk Mesopotamia, through Anatolian middlemen. The first contact between southern urban civilizations and the people of the steppe margins occurred in about 3700–3500 BCE. It caused a social and political transformation that was expressed archaeologically as the Maikop culture of the North Caucasus piedmont. Maikop was the filter through which southern innovations—including possibly wagons—first entered the steppes. Sheep bred to grow long wool might have passed from north to south in return, a little considered possibility. The Maikop chiefs used a tomb type that looked like an elaborated copy of the Suvorovo-Novodanilovka kurgan graves of the steppes, and some of them seem to have moved north into the steppes. A few Maikop traders might have lived inside steppe settlements on the lower Don River. But, oddly, very little southern wealth was shared with the steppe clans. The gold, turquoise, and carnelian stayed in the North Caucasus. Maikop people might have driven the first wagons into the Eurasian steppes, and they certainly introduced new metal alloys that made a more sophisticated metallurgy possible. We do not know what they took in return—possibly wool, possibly horses, possibly even Cannabis or saiga antelope hides, though there is only circumstantial evidence for any of these. But in most parts of the Pontic-Caspian steppes the evidence for contact with Maikop is slight—a pot here, an arsenical bronze axe-head there.

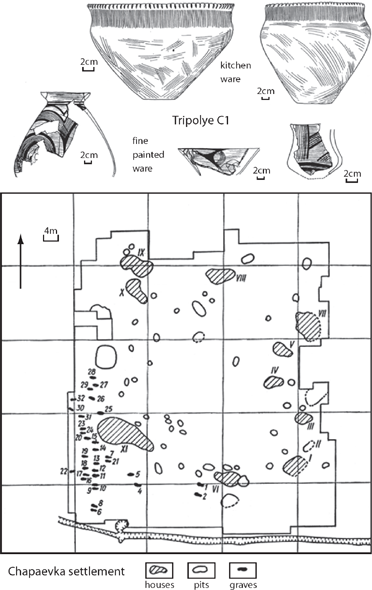

On the west, Tripolye (C1) agricultural towns on the middle Dnieper began to bury their dead in cemeteries—the first Tripolye communities to accept the ritual of cemetery burial—and their coarse pottery began to look more and more like late Sredni Stog pottery. This was the first stage in the breakdown of the Dnieper frontier, a cultural border that had existed for two thousand years, and it seems to have signaled a gradual process of cross-border assimilation in the middle Dnieper forest-steppe zone. But while assimilation and incremental change characterized Tripolye towns on the middle Dnieper frontier, Tripolye towns closer to the steppe border on the South Bug River ballooned to enormous sizes, more than 350 ha, and, between about 3600 and 3400 BCE, briefly became the largest human settlements in the world. The super towns of Tripolye C1 were more than 1 km across but had no palaces, temples, town walls, cemeteries, or irrigation systems. They were not cities, as they lacked the centralized political authority and specialized economy associated with cities, but they were actually bigger than the earliest cities in Uruk Mesopotamia. Most Ukrainian archaeologists agree that warfare and defense probably were the underlying reasons why the Tripolye population aggregated in this way, and so the super towns are seen as a defensive strategy in a situation of confrontation and conflict, either between the Tripolye towns or between those towns and the people of the steppes, or both. But the strategy failed. By 3300 BCE all the big towns were gone, and the entire South Bug valley was abandoned by Tripolye farmers.

Finally, on the east, on the Ural River, a section of the Volga-Ural steppe population decided, about 3500 BCE, to migrate eastward across Kazakhstan more than 2000 km to the Altai Mountains. We do not know why they did this, but their incredible trek across the Kazakh steppes led to the appearance of the Afanasievo culture in the western Gorny Altai. The Afanasievo culture was intrusive in the Altai, and it introduced a suite of domesticated animals, metal types, pottery types, and funeral customs that were derived from the Volga-Ural steppes. This long-distance migration almost certainly separated the dialect group that later developed into the Indo-European languages of the Tocharian branch, spoken in Xinjiang in the caravan cities of the Silk Road around 500 CE but divided at that time into two or three quite different languages, all exhibiting archaic Indo-European traits. Most studies of Indo-European sequencing put the separation of Tocharian after that of Anatolian and before any other branch. The Afanasievo migration meets that expectation. The migrants might also have been responsible for introducing horseback riding to the pedestrian foragers of the northern Kazakh steppes, who were quickly transformed into the horse-riding, wild-horse–hunting Botai culture just when the Afanasievo migration began.

By this time, early Proto-Indo-European dialects must have been spoken in the Pontic-Caspian steppes, tongues revealing the innovations that separated all later Indo-European languages from the archaic Proto-Indo-European of the Anatolian type. The archaeological evidence indicates that a variety of different regional cultures still existed in the steppes, as they had throughout the Eneolithic. This regional variability in material culture, though not very robust, suggests that early Proto-Indo-European probably still was a regional language spoken in one part of the Pontic-Caspian steppes—possibly in the eastern part, since this was where the migration that led to the Tocharian branch began. Groups that distinguished themselves by using eastern innovations in their speech probably were engaging in a political act—allying themselves with specific clans, their political institutions, and their prestige—and in a religious act—accepting rituals, songs, and prayers uttered in that eastern dialect. Songs, prayers, and poetry were central aspects of life in all early Indo-European societies; they were the vehicle through which the right way of speaking reproduced itself publicly.

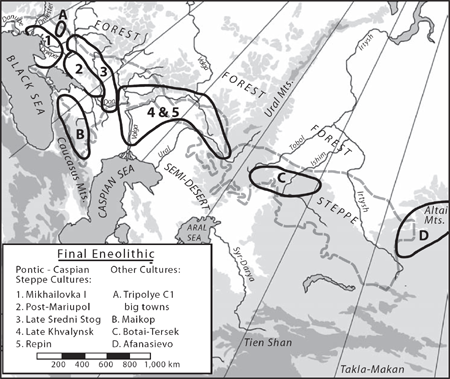

Much regional diversity and relatively little wealth existed in the Pontic-Caspian steppes between about 3800 and 3300 BCE (table 12.1). Regional variants as defined by grave and pot types, which is how archaeologists define them, had no clearly defined borders; on the contrary, there was a lot of border shifting and inter-penetration. At least five Final Eneolithic archaeological cultures have been identified in the Pontic-Caspian steppes (figure 12.1). Sites of these five groups are sometimes found in the same regions, occasionally in the same cemeteries; overlapped in time; shared a number of similarities; and were, in any case, fairly variable. In these circumstances, we cannot be sure that they all deserve recognition as different archaeological cultures. But we cannot understand the archaeological descriptions of this period without them, and together they provide a good picture of what was happening in the Pontic-Caspian steppes between 3800 and 3300 BCE. The western groups were engaged in a sort of two-pronged death dance, as it turned out, with the Cucuteni-Tripolye culture. The southern groups interacted with Maikop traders. And the eastern groups cast off a set of migrants who rode across Kazakhstan to a new home in the Altai, a subject reserved for the next chapter. Horseback riding is documented archaeologically in Botai-Tersek sites in Kazakhstan during this period (chapter 10) and probably appeared earlier, and so we proceed on the assumption that most steppe tribes were now equestrian.

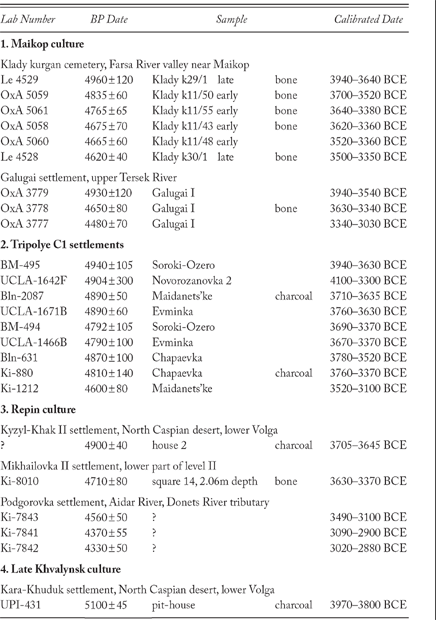

TABLE 12.1 Selected Radiocarbon Dates for Final Eneolithic Sites in the Steppes and Early Bronze Age Sites in the North Caucasus Piedmont

Figure 12.1 Final Eneolithic culture areas from the Carpathians to the Altai, 3800–3300 BCE.

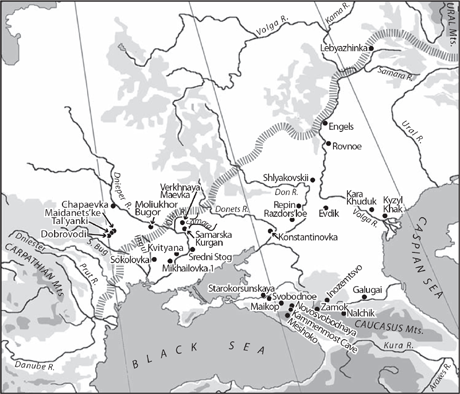

Figure 12.2 Final Eneolithic sites in the steppes and Early Bronze Age sites in the North Caucasus piedmont.

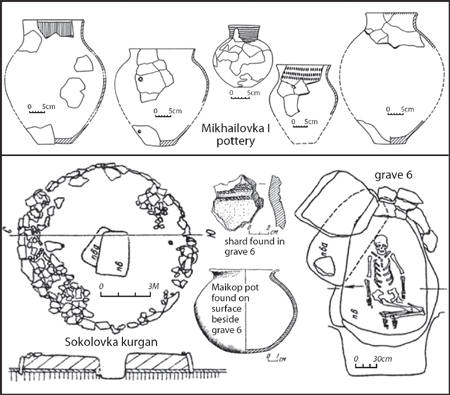

The westernmost of the five Final Eneolithic cultures of the Pontic-Caspian steppes was the Mikhailovka I culture, also called the Lower Mikhailovka or Nizhnimikhailovkskii culture, named after a stratified settlement on the Dnieper located below the Dnieper Rapids (figure 12.2).2 Below the last cascade, the river spread out over a broad basin in the steppes. Braided channels crisscrossed a sandy, marshy, forested lowland 10–20 km wide and 100 km long, a rich place for hunting and fishing and a good winter refuge for cattle, now inundated by hydroelectric dams. Mikhailovka overlooked this protected depression at a strategic river crossing. Its initial establishment probably was an outgrowth of increased east-west traffic across the river. It was the most important settlement on the lower Dnieper from the Late Eneolithic through the Early Bronze Age, about 3700–2500 BCE. Mikhailovka I, the original settlement, was occupied about 3700–3400 BCE, contemporary with late Tripolye B2 and early C1, late Sredni Stog, and early Maikop. A few late Sredni Stog and Maikop pottery sherds occurred in the occupation layer at Mikhailovka I. A whole Maikop pot was found in a grave with Mikhailovka I sherds at Sokolovka on the Ingul River, in kurgan 1, grave 6a. Tripolye B2 and C1 pots also are found in Mikhailovka I graves. These exchanges of pottery show that the Mikhailovka I culture had at least sporadic contacts with Tripolye B2/C1 towns, the Maikop culture, and late Sredni Stog communities.3

The people of Mikhailovka I cultivated cereal crops. At Mikhailovka I, imprints of cultivated seeds were found on 9 pottery sherds of 2,461 examined, or 1 imprint in 273 sherds.4 The grain included emmer wheat, barley, millet, and 1 imprint of a bitter vetch seed (Vicia ervilia), a crop grown today for animal fodder. Zoologists identified 1,166 animal bones (NISP) from Mikhailovka I, of which 65% were sheep-goat, 19% cattle, 9% horse, and less than 2% pig. Wild boar, aurochs, and saiga antelope were hunted occasionally, accounting for less than 5 percent of the animal bones.

The high number of sheep-goat at Mikhailovka I might suggest that long-wool sheep were present. Wool sheep probably were present in the North Caucasus at Svobodnoe (see below) by 4000 BCE, and almost certainly were in the Danube valley during the Cernavoda III–Boleraz period around 3600–3200 BCE, so wool sheep could have been kept at Mikhailovka I. But even if long-wool sheep were bred in the steppes during this period, they clearly were not yet the basis for a widespread new wool economy, because cattle or even deer bones still outnumbered sheep in other steppe settlements.5

Mikhailovka I pottery was shell-tempered and had dark burnished surfaces, usually unornamented (figure 12.3). Common shapes were egg-shaped pots or flat-based, wide-shouldered tankards with everted rims. A few silver ornaments and one gold ring, quite rare in the Pontic steppes of this era, were found in Mikhailovka I graves.

Mikhailovka I kurgans were distributed from the lower Dnieper westward to the Danube delta and south to the Crimean peninsula, north and northwest of the Black Sea. Near the Danube they were interspersed with cemeteries that contained Danubian Cernavoda I–III ceramics.6 Most Mikhailovka I kurgans were low mounds of black earth covered by a layer of clay, surrounded by a ditch and a stone cromlech, often with an opening on the southwest side. T e graves frequently were in cists lined with stone slabs. T e body could be in an extended supine position or contracted on the side or supine with raised knees, although the most common pose was contracted on the side. Occasionally (e.g., Olaneshti, k. 2, gr. 1, on the lower Dniester) the grave was covered by a stone anthropomorphic stela– a large stone slab carved at the top into the shape of a head projecting above rounded shoulders (see figure 13.11). This was the beginning of a long and important North Pontic tradition of decorating some graves with carved stone stelae.7

Figure 12.3 Ceramics from the Mikhailovka I settlement, after Lagodovs-kaya, Shaposhnikova, and Makarevich 1959; and a Mikhailovka I grave (gr. 6) stratified above an older Eneolithic grave (gr. 6a) at Sokolovka kurgan on the Ingul River west of the Dnieper, after Sharafutdinova 1980.

The skulls and faces of some Mikhailovka I people were delicate and narrow. The skeletal anthropologist Ina Potekhina established that another North Pontic culture, the Post-Mariupol culture, looked most like the old wide-faced Suvorovo-Novodanilovka population. The Mikhailovka I people, who lived in the westernmost steppes closest to the Tripolye culture and to the lower Danube valley, seem to have intermarried more with people from Tripolye towns or people whose ancestors had lived in Danubian tells.8

The Mikhailovka I culture was replaced by the Usatovo culture in the steppes northwest of the Black Sea after about 3300 BCE. Usatovo retained some Mikhailovka I customs, such as making a kurgan with a surrounding stone cromlech that was open to the southwest. The Usatovo culture was led by a warrior aristocracy centered on the lower Dniester estuary that probably regarded Tripolye agricultural townspeople as tribute-paying clients, and that might have begun to engage in sea trade along the coast. People in the Crimean peninsula retained many Mikhailovka I customs and developed into the Kemi-Oba culture of the Early Bronze Age after about 3300 BCE. These EBA cultures will be described in a later chapter.

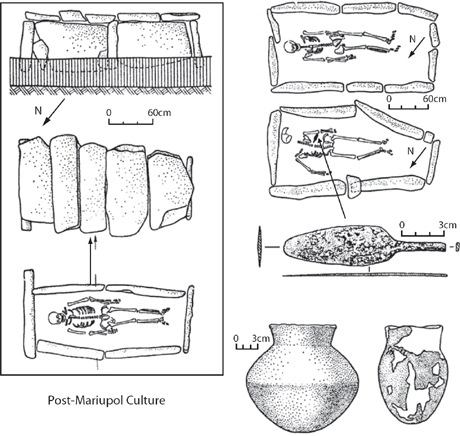

The clumsiest culture name of the Final Eneolithic is the “Post-Mariupol” or “Extended-Position-Grave” culture, both names conveying a hint of definitional uncertainty. Rassamakin called it the “Kvityana” culture. I will use the name “Post-Mariupol.” All these names refer to a grave type recognized in the steppes just above the Dnieper Rapids in the 1970s but defined in various ways since then. N. Ryndina counted about three hundred graves of the Post-Mariupol type in the steppes from the Dnieper valley eastward to the Donets. They were covered by low kurgans, occasionally surrounded by a stone cromlech. Burial was in an extended supine position in a narrow oblong or rectangular pit, often lined with stone and covered with wooden beams or stone slabs. Usually there were no ceramics in the grave (although this rule was fortunately broken in a few graves), but a fire was built above the grave; red ochre was strewn heavily on the grave floor; and lamellar flint blades, bone beads, or a few small copper beads or twists were included (figure 12.4). Three cattle skulls, presumably sacrificed at the funeral, were placed at the edge of one grave at Chkalovska kurgan 3. The largest cluster is just north of the Dnieper Rapids on the east side of the Dnieper, between two tributary rivers, the Samara (smaller than the Volga-region Samara River) and the Orel. Two chronological phases are identified: an early (Final Eneolithic) phase contemporary with Tripolye B2/C1, about 3800–3300 BCE; and a later (Early Bronze Age) phase contemporary with Tripolye C2 and the Early Yamnaya horizon, about 3300–2800 BCE.9

Figure 12.4 Post-Mariupol ceramics and graves: left, Marievka kurgan 14, grave 7; upper right, Bogdanovskogo Karera Kurgan 2, graves 2 and 17; lower right, pots from Chkalovskaya kurgan 3. After Nikolova and Rassamakin 1985, figure 7.

About 40 percent of the Post-Mariupol graves in the core Orel-Samara region contained copper ornaments, usually just one or two. All forty-six of the copper objects examined by Ryndina from early-phase graves were made from “clean” Transylvanian ores, the same ores used in Tripolye B2 and C1 sites. The copper in the second phase, however, was from two sources: ten objects still were made of “clean” Transylvanian copper but twenty-three were made of arsenical bronze. They were most similar to the arsenical bronzes of the Ustatovo settlement or the late Maikop culture. Only one Post-Mariupol object (a small willow-leaf pendant from Bulakhovka kurgan cemetery I, k. 3, gr. 9) looked metallurgically like a direct import from late Maikop.10

Two Post-Mariupol graves were metalsmiths’ graves. They contained three bivalve molds for making sleeved axes. (A sleeved axe had a single blade with a cast sleeve hole for the handle on one side.) The molds copied a late Maikop axe type but were locally made.11 They probably were late Post-Mariupol, after 3300 BCE. They are the oldest known two-sided ceramic molds in the steppes, and they were buried with stone hammers, clay tubes or tulieres for bellows attachments, and abrading stones. These kits suggest a new level of technological skill among steppe metalsmiths and the graves began a long tradition of the smith being buried with his tools.

The third and final culture group in the western part of the Pontic-Caspian steppes was the late Sredni Stog culture. Late Sredni Stog pottery was shell-tempered and often decorated with cord-impressed geometric designs (see figure 11.7), quite unlike the plain, dark-surfaced pots of Mikhailovka I and the Post-Mariupol culture. The late Sredni Stog settlement of Moliukhor Bugor was located on the Dnieper in the forest-steppe zone. A Tripolye C1 vessel was found there. The people of Moliukhor Bugor lived in a house 15 m by 12 m with three internal hearths, hunted red deer and wild boar, fished, kept a lot of horses and a few domesticated cattle and sheep, and grew grain. Eight grain impressions were found among 372 sherds (one imprint in 47 sherds), a higher frequency than at Mikhailovka I. They included emmer wheat, einkorn wheat, millet, and barley. The well-known Sredni Stog settlement at Dereivka was occupied somewhat earlier, about 4000 BCE, but also produced many flint blades with sickle gloss and six stone querns for grinding grain, and so also probably included some grain cultivation.

Horses represented 63% of the animal bones at Dereivka (see chapter 10). The Sredni Stog societies on the Dnieper, like the other western steppe groups, had a mixed economy that combined grain cultivation, stockbreeding, horseback riding, and hunting and fishing.

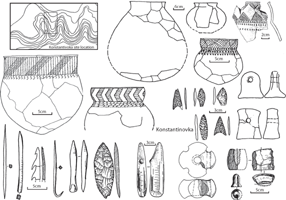

Late Sredni Stog sites were located in the northern steppe and southern forest-steppe zones on the middle Dnieper, north of the Post-Mariupol and Mikhailovka I groups. Sredni Stog sites also extended from the Dnieper eastward across the middle Donets to the lower Don. The most important stratified settlement on the lower Don was Razdorskoe [raz-DOR-sko-ye]. Level 4 at Razdorskoe contained an early Khvalynsk component, level 5 above it had an early Sredni Stog (Novodanilovka period) occupation, and, after that, levels 6 and 7 had pottery that resembled late Sredni Stog mixed with imported Maikop pottery. A radiocarbon date said to be associated with level 6, on organic material in a core removed for pollen studies, produced a date of 3500–2900 BCE (4490 ± 180 BP). Near Razdorskoe was the fortified settlement at Konstantinovka. Here, in a place occupied by people who made similar lower-Don varieties of late Sredni Stog pottery, there might actually have been a small Maikop colony.12

Bodies buried in Sredni Stog graves usually were in the supine-with-raised knees position that was such a distinctive aspect of steppe burials beginning with Khvalynsk. The grave floor was strewn with red ochre, and the body often was accompanied by a unifacial flint blade or a broken pot. Small mounds sometimes were raised over late Sredni Stog graves, but in many cases they were flat.

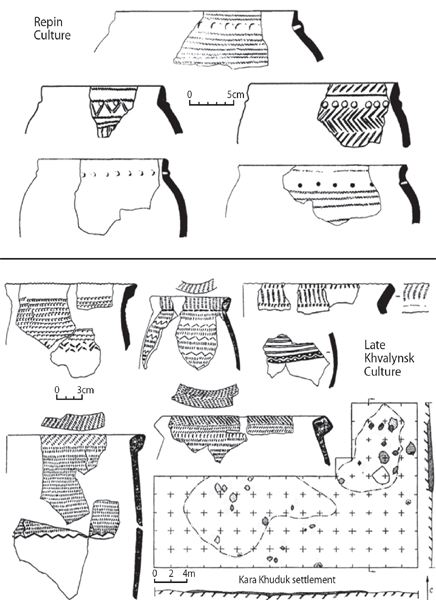

The two eastern groups can be discussed together. They are identified with two quite different kinds of pottery. One type clearly resembled a late variety of Khvalynsk pottery. The other type, called Repin, probably began on the middle Don, and is identified by round-based pots with cord-impressed decoration and decorated rims.

Repin, excavated in the 1950s, was located 250 km upstream from Razdorskoe, on the middle Don at the edge of the feather-grass steppe. At Repin 55% of the animal bones were horse bones. Horse meat was much more important in the diet than the meat of cattle (18%), sheep-goat (9%), pigs (9%), or red deer (9%).13 Perhaps Repin specialized in raising horses for export to North Caucasian traders (?). The pottery from Repin defined a type that has been found at many sites in the Don-Volga region. Repin pottery sometimes is found stratified beneath Yamnaya pottery, as at the Cherkasskaya settlement on the middle Don in the Voronezh oblast.14 Repin components occur as far north as the Samara oblast in the middle Volga region, at sites such as Lebyazhinka I on the Sok River, in contexts also thought to predate early Yamnaya. The Afanasievo migration to the Altai was carried out by people with a Repin-type material culture, probably from the middle Volga-Ural region. On the lower Volga, a Repin antelope hunters’ camp was excavated at Kyzyl Khak, where 62% of the bones were saiga antelope (figure 12.5). Cattle were 13%, sheep 9%, and horses and onagers each about 7%. A radiocarbon date (4900 ± 40 BP) put the Repin occupation at Kyzyl-Khak at about 3700–3600 BCE.

Kara Khuduk was another antelope hunters’ camp on the lower Volga but was occupied by people who made late Khvalynsk-type pottery (figure 12.5). A radiocarbon date (5100 ± 45 BP, UPI 430) indicated that it was occupied in about 3950–3800 BCE, earlier than the Repin occupation at Kyzyl-Khak nearby. Many large scrapers, possibly for hide processing, were found among the flint tools. Saiga antelope hides seem to have been highly desired, perhaps for trade. The animal bones were 70% saiga antelope, 13% cattle, and 6% sheep. The ceramics (670 sherds from 30–35 vessels) were typical Khvalynsk ceramics: shell-tempered, round-bottomed vessels with thick, everted lips, covered with comb stamps and corded-impressed U-shaped “caterpillar” impressions.

Late Khvalynsk graves without kurgans were found in the 1990s at three sites on the lower Volga: Shlyakovskii, Engels, and Rovnoe. The bodies were positioned on the back with knees raised, strewn with red ochre, and accompanied by lamellar flint blades, flint axes with polished edges, polished stone mace heads of Khvalynsk type, and bone beads. Late Khvalynsk populations lived in scattered enclaves on the lower Volga. Some of them crossed the northern Caspian, perhaps by boat, and established a group of camps on its eastern side, in the Mangyshlak peninsula.

The Volga-Don late Khvalynsk and Repin societies played a central role in the evolution of the Early Bronze Age Yamnaya horizon beginning around 3300 BCE (discussed in the next chapter). One kind of early Yamnaya pottery was really a Repin type, and the other kind was actually a late Khvalynsk type; so, if no other clues are present, it can be difficult to separate Repin or late Khvalynsk pottery from early Yamnaya pottery. The Yamnaya horizon probably was the medium through which late Proto-Indo-European languages spread across the steppes. This implies that classic Proto-Indo-European dialects were spoken among the Repin and late Khvalynsk groups.15

Figure 12.5 Repin pottery from Kyzl-Khak (top) and late Khvalynsk pottery and settlement plan from Kara-Khuduk (bottom) on the lower Volga. After Barynkin, Vasiliev, and Vybornov 1998, figures 5 and 6.

Two notable and quite different kinds of changes affected the Tripolye culture between about 3700 and 3400 BCE. First, the Tripolye settlements in the forest-steppe zone on the middle Dnieper began to make pottery that looked like Pontic-Caspian ceramics (dark, occasionally shell-tempered wares) and adopted Pontic-Caspian–style inhumation funerals. The Dnieper frontier became more porous, probably through gradual assimilation. But Tripolye settlements on the South Bug River, near the steppe border, changed in very different ways. They mushroomed to enormous sizes, more than 400 ha, twice the size of the biggest cities in Mesopotamia. Simply put, they were the biggest human settlements in the world. And yet, instead of evolving into cities, they were abruptly abandoned.

Chapaevka was a Tripolye B2/C1 settlement of eleven dwellings located on a promontory west of the Dnieper valley in the northern forest-steppe zone. It was occupied about 3700–3400 BCE.16 Chapaevka is the earliest known Tripolye community to adopt cemetery burial (figure 12.6). A cemetery of thirty-two graves appeared on the edge of settlement. The form of burial, in an extended supine position, usually with a pot, sometimes with a piece of red ochre under the head or chest, was not exactly like any of the steppe grave types, but just the acceptance of the burial of the body was a notable change from the Old European funeral customs of the Tripolye culture. Chapaevka also had lightly built houses with dug-out floors rather than houses with plastered log floors (ploshchadka). Tripolye C1 pottery was found at Moliukhor Bugor, about 150 km to the south, perhaps the source of some of these new customs.

Most of the ceramics in the Chapaevka houses were well-fired fine wares with fine sand temper or very fine clay fabrics (50–70%), of which a small percentage (1–10%) were painted with standard Tripolye designs; but generally they were black to grey in color, with burnished surfaces, and were often undecorated. They were quite different from the orange wares that had typified earlier Tripolye ceramics. Undecorated grey-to-black ware also was typical of the Mikhailovka I and Post-Mariupol cultures, although their shapes and clay fabrics differed from most of those of the Tripolye C1 culture. One class of Chapaevka kitchen-ware pots with vertical combed decoration on the collars looked so much like late Sredni Stog pots that it is unclear whether this kind of ware was borrowed from Tripolye by late Sredni Stog potters or by Tripolye C1 potters from late Sredni Stog.17 Around 3700–3500 BCE the Dnieper frontier was becoming a zone of gradual, probably peaceful assimilation between Tripolye villagers and indigenous Sredni Stog societies east of the Dnieper.

Figure 12.6 Tripolye C1 settlement at Chapaevka on the Dnieper with eleven houses (features I–XI) and cemetery (gr. 1–32) and ceramics. After Kruts 1977, figures 5 and 16.

Closer to the steppe border things were quite different. All the Tripolye settlements located between the Dnieper and South Bug rivers, including Chapaevka, were oval, with houses arranged around an open central plaza. Some villages occupied less than 1 ha, many were towns of 8–15 ha, some were more than 100 ha, and a group of three Tripolye C1 sites located within 20 km of one another reached sizes of 250–450 ha between about 3700 and 3400 BCE. These super sites were located in the hills east of the South Bug River, near the edge of the steppe in the southern forest-steppe zone. They were the largest communities not just in Europe but in the world.18

The three known super-sites—Dobrovodi (250 ha), Maidanets’ke (250 ha), and Tal’yanki (450 ha)—perhaps were occupied sequentially in that order. None of these sites contained an obvious administrative center, palace, storehouse, or temple. They had no surrounding fortification wall or moat, although the excavators Videiko and Shmagli described the houses in the outer ring as joined in a way that presented an unbroken two-story-high wall pierced only by easily defended radial streets. The most thoroughly investigated of the three, Maidanets’ke, covered 250 ha. Magnetometer testing revealed 1,575 structures (figure 12.7). Most were inhabited simultaneously (there was almost no overbuilding of newer houses over older ones) by a population estimated at fifty-five hundred to seventy-seven hundred people. Using Bibikov’s estimate of 0.6 ha of cultivated wheat per person per year, a population of that magnitude would have required 3,300–4,620 ha of cultivated fields each year, which would have necessitated cultivating fields more than 3 km from the town.18 The houses were built close to one another in concentric oval rings, on a common plan, oriented toward a central plaza. The excavated houses were large, 5–8 m wide and 20–30 m long, and many were two-storied. Videiko and Shmagli suggested a political organization based on clan segments. They documented the presence of one larger house for each five to ten smaller houses. The larger houses usually contained more female figurines (rare in most houses), more fine painted pots, and sometimes facilities such as warp-weighted looms. Each large house could have been a community center for a segment of five to ten houses, perhaps an extended family (or a “super-family collective,” in Videiko’s words). If the super towns were organized in this way, a council of 150–300 segment leaders would have made decisions for the entire town. Such an unwieldy system of political management could have contributed to its own collapse. After Maidanests’ke and Tal’yanki were abandoned, the largest town in the South Bug hills was Kasenovka (120 ha, with seven to nine concentric rings of houses), dated to the Tripolye C1/C2 transition, perhaps 3400–3300 BCE. When Kasenovka was abandoned, Tripolye people evacuated most of the South Bug valley.

Figure 12.7 The Tripolye C1 Maidanets’ke settlement, with 1,575 structures mapped by magnetometers: left: smaller houses cluster around larger houses, thought to be clan or sub-clan centers; right: a house group very well preserved by the Yamnaya kurgan built on top of it, showing six inserted late Yamnaya graves. Artifacts from the settlement: top center, a cast copper axe; central row, a polished stone axe and two clay loom weights; bottom row, selected painted ceramics. After Shmagli and Videiko 1987; and Videiko 1990.

Specialized craft centers appeared in Tripolye C1 communities for making flint tools, weaving, and manufacturing ceramics. These crafts became spatially segregated both within and between towns.20 A hierarchy appeared in settlement sizes, comprised of two and perhaps three tiers. These kinds of changes usually are interpreted as signs of an emerging political hierarchy and increasing centralization of political power. But, as noted, instead of developing into cities, the towns were abandoned.

Population concentration is a standard response to increased warfare among tribal agriculturalists, and the subsequent abandonment of these places suggests that warfare and raiding was at the root of the crisis. The aggressors could have been steppe people of Mikhailovka I or late Sredni Stog type. A settlement at Novorozanovka on the Ingul, west of the Dnieper, produced a lot of late Sredni Stog cord-impressed pottery, some Mikhailovka I pottery, and a few imported Tripolye C1 painted fine pots. Mounted raiding might have made it impossible to cultivate fields more than 3 km from the town. Raiding for cattle or captives could have caused the fragmentation and dispersal of the Tripolye population and the abandonment of town-based craft traditions just as it had in the Danube valley some five hundred years earlier. Farther north, in the forest-steppe zone on the middle Dnieper, assimilation and exchange led ultimately in the same direction but more gradually.

Steppe contact with the civilizations of Mesopotamia was, of course, much less direct than contact with Tripolye societies, but the southern door might have been the avenue through which wheeled vehicles first appeared in the steppes, so it was important. Our understanding of these contacts with the south has been completely rewritten in recent years.

Between 3700 and 3500 BCE the first cities in the world appeared among the irrigated lowlands of Mesopotamia. Old temple centers like Uruk and Ur had always been able to attract thousands of laborers from the farms of southern Iraq for building projects, but we are not certain why they began to live around the temples permanently (figure 12.8). This shift in population from the rural villages to the major temples created the first cities. During the Middle and Late Uruk periods (3700–3100 BCE) trade into and out of the new cities increased tremendously in the form of tribute, gift exchange, treaty making, and the glorification of the city temple and its earthly authorities. Precious stones, metals, timber, and raw wool (see chapter 4) were among the imports. Woven textiles and manufactured metal objects probably were among the exports. During the Late Uruk period, wheeled vehicles pulled by oxen appeared as a new technology for land transport. New accounting methods were developed to keep track of imports, exports, and tax payments—cylinder seals for marking sealed packages and the sealed doors of storerooms, clay tokens indicating package contents, and, ultimately, writing.

The new cities had enormous appetites for copper, gold, and silver. Their agents began an extraordinary campaign, or perhaps competing campaigns by different cities, to obtain metals and semiprecious stones. The native chiefdoms of Eastern Anatolia already had access to rich deposits of copper ore, and had long been producing metal tools and weapons. Emissaries from Uruk and other Sumerian cities began to appear in northern cities like Tell Brak and Tepe Gawra. South Mesopotamian garrisons built and occupied caravan forts on the Euphrates in Syria at Habubu Kabira. The “Uruk expansion” began during the Middle Uruk period about 3700 BCE and greatly intensified during Late Uruk, about 3350–3100 BCE. The city of Susa in southwestern Iran might have become an Uruk colony. East of Susa on the Iranian plateau a series of large mudbrick edifices rose above the plains, protecting specialized copper production facilities that operated partly for the Uruk trade, regulated by local chiefs who used the urban tools of trade management: seals, sealed packages, sealed storerooms, and, finally, writing. Copper, lapis lazuli, turquoise, chlorite, and carnelian moved under their seals to Mesopotamia. Uruk-related trade centers on the Iranian plateau included Sialk IV1, Tal-i-Iblis V–VI, and Hissar II in central Iran. The tentacles of trade reached as far northeast as the settlement of Sarazm in the Zerafshan Valley of modern Tajikistan, probably established to control turquoise deposits in the deserts nearby.

Figure 12.8 Maikop culture and selected sites associated with the Uruk expansion.

The Uruk expansion to the northwest, toward the gold, silver, and copper sources in the Caucasus Mountains, is documented at two important local strongholds on the upper Euphrates. Hacinebi was a fortified center with a large-scale copper production industry. Its chiefs began to deal with Middle Uruk traders during its phase B2, dated about 3700–3300 BCE. More than 250 km farther up the Euphrates, high in the mountains of Eastern Anatolia, the stronghold at Arslantepe expanded in wealth and size at about the same time (Phase VII), although it retained its own native system of seals, architecture, and administration. It also had its own large-scale copper production facilities based on local ores. Phase VIA, beginning about 3350 BCE, was dominated by two new pillared buildings similar to Late Uruk temples. In them officials regulated trade using some Uruk-style seals (among many local-style seals) and gave out stored food in Uruk-type, mass-produced ration bowls. The herds of Arslantepe VII had been dominated by cattle and goats, but in phase VIA sheep rose suddenly to become the most numerous and important animal, probably for the new industry of wool production. Horses also appeared, in very small numbers, at Arslantepe VII and VIA and Hacinebi phase B, but they seem not to have been traded southward into Mesopotamia. The Uruk expansion ended abruptly about 3100 BCE for reasons that remain obscure. Arslantepe and Hacinebi were burned and destroyed, and in the mountains of eastern Anatolia local Early Trans-Caucasian (ETC) cultures built their humble homes over the ruins of the grand temple buildings.21

Societies in the mountains to the north of Arslantepe responded in various ways to the general increase in regional trade that began about 3700–3500 BCE. Novel kinds of public architecture appeared. At Berikldeebi, northwest of modern Tbilisi in Georgia, a settlement that had earlier consisted of a few flimsy dwellings and pits was transformed about 3700–3500 BCE by the construction of a massive mudbrick wall that enclosed a public building, perhaps a temple, measuring 14.5 × 7.5 m (50 × 25 ft). At Sos level Va near Erzerum in northeastern Turkey there were similar architectural hints of increasing scale and power.22 But neither prepares us for the funerary splendor of the Maikop culture.

The Maikop culture appeared about 3700–3500 BCE in the piedmont north of the North Caucasus Mountains, overlooking the Pontic-Caspian steppes. The remi-royal figure buried under the giant Maikop chieftan’s kurgan acquired and wore Mesopotamian ornaments in an ostentatious funeral display that had no parallel that has been preserved even in Mesopotamia. Into the grave went a tunic covered with golden lions and bulls, silversheathed staffs mounted with solid gold and silver bulls, and silver sheet-metal cups. Wheel-made pottery was imported from the south, and the new technique was used to make Maikop ceramics similar to some of the vessels found at Berikldeebi and at Arslantepe VII/VIA.23 New high-nickel arsenical bronzes and new kinds of bronze weapons (sleeved axes, tanged daggers) also spread into the North Caucasus from the south, and a cylinder seal from the south was worn as a bead in another Maikop grave. What kinds of societies lived in the North Caucasus when this contact began?

The North Caucasian piedmont separates naturally into three geographic parts. The western part is drained by the Kuban River, which flows into the Sea of Azov. The central part is a plateau famous for its bubbling hot springs, with resort towns like Mineralnyi Vody (Mineral Water) and Kislovodsk (Sweet Water). The eastern part is drained by the Terek River, which flows into the Caspian Sea. The southern skyline is dominated by the permanently glaciated North Caucasus Mountains, which rise to icy peaks more than 5,600 m (18,000 ft) high; and off to the north are the rolling brown plains of the steppes.

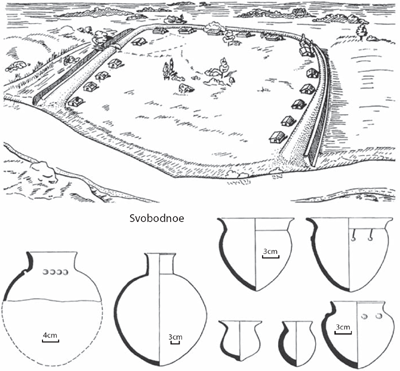

Herding, copper-using cultures lived here by 5000 BCE. The Early Eneolithic cemetery at Nalchik and the cave occupation at Kammenomost Cave (chapter 9) date to this period. Beginning about 4400–4300 BCE the people of the North Caucasus began to settle in fortified agricultural villages such as Svobodnoe and Meshoko (level 1) in the west, Zamok on the central plateau, and Ginchi in Dagestan in the east, near the Caspian. About ten settlements of the Svobodnoe type, of thirty to forty houses each, are known in the Kuban River drainage, apparently the most densely settled region. Their earthen or stone walls enclosed central plazas surrounded by solid wattle-and-daub houses. Svobodnoe, excavated by A. Nekhaev, is the best-reported site (figure 12.9). Half the animal bones from Svobodnoe were from wild red deer and boar, so hunting was important. Sheep were the most important domesticated animal, and the proportion of sheep to goats was 5:1, which suggests that sheep were kept for wool. But pig keeping also was important, and pigs were the most important meat animals at the settlement of Meshoko.

Svobodnoe pots were brown to orange in color and globular with everted rims, but decorative styles varied greatly between sites (e.g., Zamok, Svobodnoe, and Meshoko are said to have had quite different domestic pottery types). Female ceramic figurines suggest female-centered domestic rituals. Bracelets carved and polished of local serpentine were manufactured in the hundreds at some sites. Cemeteries are almost unknown, but a few individual graves found among later graves under kurgans in the Kuban region have been ascribed to the Late Eneolithic. The Svobodnoe culture differed from Repin or late Khvalynsk steppe cultures in its house forms, settlement types, pottery, stone tools, and ceramic female figurines. Probably it was distinct ethnically and linguistically.24

Figure 12.9 Svobodnoe settlement and ceramics, North Caucasus. After Nekhaev 1992.

Nevertheless, the Svobodnoe culture was in contact with the steppes. A Svobodnoe pot was deposited in the rich grave at Novodanilovka in the Azov steppes, and a copper ring made of Balkan copper, traded through the Novodanilovka network, was found at Svobodnoe. Potsherds that look like early Sredni Stog types were noted at Svobodnoe and Meshoko 1. Green serpentine axes from the Caucasus appeared in several steppe graves and in settlements of the early Sredni Stog culture (Strilcha Skelya, Aleksandriya, Yama). The Svobodnoe-era settlements in the Kuban River valley participated in the eastern fringe of the steppe Suvorovo-Novodanilovka activities around 4000 BCE.

The shift from Svobodnoe to Maikop was accompanied by a sudden change in funeral customs—the clear and widespread adoption of kurgan graves—but there was continuity in settlement locations and settlement types, lithics, and some aspects of ceramics. Early Maikop ceramics showed some similarities with Svobodnoe pot shapes and clay fabrics, and some similarities with the ceramics of the Early Trans-Caucasian (ETC) culture south of the North Caucasus Mountains. These analogies indicate that Maikop developed from local Caucasian origins. But some Maikop pots were wheel-made, a new technology introduced from the south, and this new method of manufacture probably encouraged new vessel shapes.

The Maikop chieftain’s grave, discovered on the Belaya River, a tributary of the Kuban River, was the first Maikop-culture tomb to be excavated, and it remains the most important early Maikop site. When excavated in 1897 by N. I. Veselovskii, the kurgan was almost 11 m high and more than 100 m in diameter. The earthen center was surrounded by a cromlech of large undressed stones. Externally it looked like the smaller Mikhailovka I and Post-Mariupol kurgans (and, before them, the Suvorovo kurgans), which also had earthen mounds surrounded by stone cromlechs. Internally, however, the Maikop chieftan’s grave was quite different. The grave chamber was more than 5 m long and 4 m wide, 1.5 m deep, and was lined with large timbers. It was divided by timber partitions into two northern chambers and one southern chamber. The two northern chambers each held an adult female, presumably sacrificed, each lying in a contracted position on her right side, oriented southwest, stained with red ochre, with one to four pottery vessels and wearing twisted silver foil ornaments.25

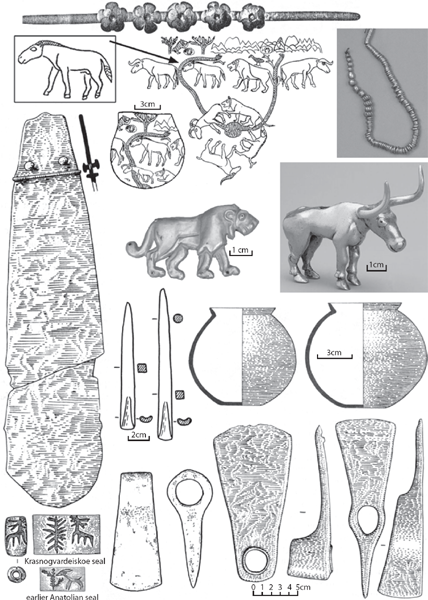

The southern chamber contained an adult male. He also probably was positioned on his right side, contracted, with his head oriented southwest, the pose of most Maikop burials. He also lay on ground deeply stained with red ochre. With him were eight red-burnished, globular pottery vessels, the type collection for Early Maikop; a polished stone cup with a sheet-gold cover; two arsenical bronze, sheet-metal cauldrons; two small cups of sheet gold; and fourteen sheet-silver cups, two of which were decorated with impressed scenes of animal processions including a Caucasian spotted panther, a southern lion, bulls, a horse, birds, and a shaggy animal (bear? goat?) mounting a tree (figure 12.10). The engraved horse is the oldest clear image of a post-glacial horse, and it looked like a modern Przewalski: thick neck, big head, erect mane, and thick, strong legs. The chieftan also had arsenical bronze tools and weapons. They included a sleeved axe, a hoe-like adze, an axe-adze, a broad spatula-shaped metal blade 47 cm long with rivets for the attachment of a handle, and two square-sectioned bronze chisels with round-sectioned butts. Beside him was a bundle of six (or possibly eight) hollow silver tubes about 1 m long. They might have been silver casings for a set of six (or eight) wooden staffs, perhaps for holding up a tent that shaded the chief. Long-horned bulls, two of solid silver and two of solid gold, were slipped over four of the silver casings through holes in the middle of the bulls, so that when the staffs were erect the bulls looked out at the visitor. Each bull figure was sculpted first in wax; very fine clay was then pressed around the wax figure; this clay was next wrapped in a heavier clay envelope; and, finally, the clay was fired and the wax burned off—the lost wax method for making a complicated metal-casting mold. The Maikop chieftain’s grave contained the first objects made this way in the North Caucasus. Like the potters wheel, the arsenical bronze, and the animal procession motifs engraved on two silver cups, these innovations came from the south.26

Figure 12.10 Early Maikop objects from the chieftain’s grave at Maikop, the State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg; and a seal at lower left from the early Maikop Krasnogvardeiskoe kurgan, with a comparative seal from Chalcolithic Degirmentepe in eastern Anatolia. The lion, bull, necklace, and diadem are gold; the cup with engraved design is silver; the two pots are ceramic; and the other objects are arsenical bronze. The bronze blade with silver rivets is 47 cm long and had sharp edges. After Munchaev 1994 and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

The Maikop chieftan was buried wearing Mesopotamian symbols of power—the lion paired with the bull—although he probably never saw a lion. Lion bones are not found in the North Caucasus. His tunic had sixty-eight golden lions and nineteen golden bulls applied to its surface. Lion and bull figures were prominent in the iconography of Uruk Mesopotamia, Hacinebi, and Arslantepe. Around his neck and shoulders were 60 beads of turquoise, 1,272 beads of carnelian, and 122 golden beads. Under his skull was a diadem with five golden rosettes of five petals each on a band of gold pierced at the ends. The rosettes on the Maikop diadem had no local prototypes or parallels but closely resemble the eight-petaled rosette seen in Uruk art. The turquoise almost certainly came from northeastern Iran near Nishapur or from the Amu Darya near the trade settlement of Sarazm in modern Tajikistan, two regions famous in antiquity for their turquoise. The red carnelian came from western Pakistan and the lapis lazuli from eastern Afghanistan. Because of the absence of cemeteries in Uruk Mesopotamia, we do not know much about the decorations worn there. The abundant personal ornaments at Maikop, many of them traded up the Euphrates through eastern Anatolia, probably were not made just for the barbarians. They provide an eye-opening glimpse of the kinds of styles that must have been seen in the streets and temples of Uruk.

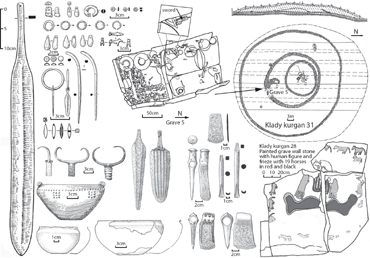

The relationship between Maikop and Mesopotamia was misunderstood until just recently. The extraordinary wealth of the Maikop culture seemed to fit comfortably in an age of ostentation that peaked around 2500 BCE, typified by the gold treasures of Troy II and the royal “death-pits” of Ur in Mesopotamia. But since the 1980s it has slowly become clear that the Maikop chieftain’s grave probably was constructed about 3700–3400 BCE, during the Middle Uruk period in Mesopotamia—a thousand years before Troy II. The archaic style of the Maikop artifacts was recognized in the 1920s by Rostovtseff, but it took radiocarbon dates to prove him right. Rezepkin’s excavations at Klady in 1979–80 yielded six radiocarbon dates averaging between 3700 and 3200 BCE (on human bone, so possibly a couple of centuries too old because of old carbon contamination from fish in the diet). These dates were confirmed by three radiocarbon dates also averaging between 3700 and 3200 BCE at the early Maikop-culture settlement of Galugai, excavated by S. Korenevskii between 1985 and 1991 (on animal bone and charcoal, so probably accurate). Galugai’s pot types and metal types were exactly like those in the Maikop chieftain’s grave, the type site for early Maikop. Graves in kurgan 32 at Ust-Dzhegutinskaya that were stylistically post-Maikop were radiocarbon dated about 3000–2800 BCE. These dates showed that Maikop was contemporary with the first cities of Middle and Late Uruk-period Mesopotamia, 3700–3100 BCE, an extremely surprising discovery.27

The radiocarbon dates were confirmed by an archaic cylinder seal found in an early Maikop grave excavated in 1984 at Krasnogvardeiskoe, about 60 km north of the Maikop chieftain’s grave. This grave contained an east Anatolian agate cylinder seal engraved with a deer and a tree of life. Similar images appeared on stamp seals at Degirmentepe in eastern Anatolia before 4000 BCE, but cylinder seals were a later invention, appearing first in Middle Uruk Mesopotamia. The one from the kurgan at Kransogvardeiskoe (Red Guards), perhaps worn as a bead, is among the oldest of the type (see figure 12:10).28

The Maikop chieftain’s grave is the type site for the early Maikop period, dated between 3700 and 3400 BCE. All the richest graves and hoards of the early period were in the Kuban River region, but the innovations in funeral ceremonies, arsenical bronze metallurgy, and ceramics that defined the Maikop culture were shared across the North Caucasus piedmont to the central plateau and as far as the middle Terek River valley. Galugai on the middle Terek River was an early Maikop settlement, with round houses 6–8 m in diameter scattered 10–20 m apart along the top of a linear ridge. The estimated population was less than 100 people. Clay, bell-shaped loom weights indicated vertical looms; four were found in House 2. The ceramic inventory consisted largely of open bowls (probably food bowls) and globular or elongated, round-bodied pots with everted rims, fired to a reddish color; some of these were made on a slow wheel. Cattle were 49% of the animal bones, sheep-goats were 44%, pigs were 3%, and horses (presumably horses that looked like the one engraved on the Maikop silver cup) were 3%. Wild boar and onagers were hunted only occasionally. Horse bones appeared in other Maikop settlements, in Maikop graves (Inozemstvo kurgan contained a horse jaw), and in Maikop art, including a frieze of nineteen horses painted in black and red colors on a stone wall slab inside a late Maikop grave at Klady kurgan 28 (figure 12.11). The widespread appearance of horse bones and images in Maikop sites suggested to Chernykh that horseback riding began in the Maikop period.29

The late phase of the Maikop culture probably should be dated about 3400–3000 BCE, and the radiocarbon dates from Klady might support this if they were corrected for reservoir effects. Having no 15N measurements from Klady, I don’t know if this correction is justified. The type sites for the late Maikop phase are Novosvobodnaya kurgan 2, located southeast of Maikop in the Farsa River valley, excavated by N. I. Veselovskii in 1898; and Klady (figure 12.11), another kurgan cemetery near Novosvobodnaya, excavated by A. D. Rezepkin in 1979–80. Rich graves containing metals, pottery, and beads like Novosvobodnaya and Klady occurred across the North Caucasus piedmont, including the central plateau (Inozemtsvo kurgan, near Mineralnyi Vody) and in the Terek drainage (Nalchik kurgan). Unlike the sunken grave chamber at Maikop, most of these graves were built on the ground surface (although Nalchik had a sunken grave chamber); and, unlike the timber-roofed Maikop grave, their chambers were constructed entirely of huge stones. In Novosvobodnaya-type graves the central and attendant/gift grave compartments were divided, as at Maikop, but the stone dividing wall was pierced by a round hole. The stone walls of the Nalchik grave chamber incorporated carved stone stelae like those of the Mikhailovka I and Kemi-Oba cultures (see figure 13.11).

Arsenical bronze tools and weapons were much more abundant in the richest late Maikop graves of the Klady-Novosvobodnaya type than they were in the Maikop chieftain’s grave. Grave 5 in Klady kurgan 31 alone contained fifteen heavy bronze daggers, a sword 61 cm long (the oldest sword in the world), three sleeved axes and two cast bronze hammer-axes, among many other objects, for one adult male and a seven-year-old child (see figure 12.11). The bronze tools and weapons in other Novosvobodnaya-phase graves included cast flat axes, sleeved axes, hammer-axes, heavy tanged daggers with multiple midribs, chisels, and spearheads. The chisels and spearheads were mounted to their handles the same way, with round shafts hammered into four-sided contracting bases that fit into a V-shaped rectangular hole on the handle or spear. Ceremonial objects included bronze cauldrons, long-handled bronze dippers, and two-pronged bidents (perhaps forks for retrieving cooked meats from the cauldrons). Ornaments included beads of carnelian from western Pakistan, lapis lazuli from Afghanistan, gold, rock crystal, and even a bead from Klady made of a human molar sheathed in gold (the first gold cap!). Late Maikop graves contained several late metal types—bidents, tanged daggers, metal hammer-axes, and a spearhead with a tetrahedral tang—that did not appear at Maikop or in other early sites. Flint arrowheads with deep concave bases also were a late type, and black burnished pots had not been in earlier Maikop graves.30

Figure 12.11 Late Maikop-Novosvobodnaya objects and graves at Klady, Kuban River drainage, North Caucasus: (Right) plan and section of Klady kurgan 31 and painted grave wall from Klady kurgan 28 with frieze of red-and-black horses surrounding a red-and-black humanlike figure; (left and bottom): objects from grave 5, kurgan 31. These included (left) arsenical bronze sword; (top row, center) two beads of human teeth sheathed in gold, a gold ring, and three carnelian beads; (second row) five gold rings; (third row) three rock crystal beads and a cast silver dog; (fourth row) three gold button caps on wooden cores; (fifth row) gold ring-pendant and two bent silver pins; (sixth row) carved bone dice; (seventh row) two bronze bidents, two bronze daggers, a bronze hammer-axe, a flat bronze axe, and two bronze chisels; (eighth row) a bronze cauldron with repoussé decoration; (ninth row) two bronze cauldrons and two sleeved axes. After Rezepkin 1991, figures 1, 2, 4, 5, 6.

Textile fragments preserved in Novosvobodnaya-type graves included linen with dyed brown and red stripes (at Klady), a cotton-like textile, and a wool textile (both at Novosvobodnaya kurgan 2). Cotton cloth was invented in the Indian subcontinent by 5000 BCE; the piece tentatively identified in the Novosvobodnaya royal grave might have been imported from the south.31

The southern wealth that defined the Maikop culture appeared suddenly in the North Caucasus, and in large amounts. How did this happen, and why?

The valuables that seemed the most interesting to Mesopotamian urban traders were metals and precious stones. The upper Kuban River is a metal-rich zone. The Elbrusskyi mine on the headwaters of the Kuban, 35 km northwest of Elbruz Mountain (the highest peak in the North Caucasus) produces copper, silver, and lead. The Urup copper mine, on the upper Urup River, a Kuban tributary, had ancient workings that were visible in the early twentieth century. Granitic gold ores came from the upper Chegem River near Nalchik. As the metal prospectors who profited from the Uruk metal trade explored northward, they somehow learned of the copper, silver, and gold ores on the other side of the North Caucasus Mountains. Possibly they also pursued the source of textiles made of long-woolen thread.

It is possible that the initial contacts were made on the Black Sea coast, since the mountains are easy to cross between Maikop and Sochi on the coast, but much higher and more difficult in the central part of the North Caucasus farther east. Maikop ceramics have been found north of Sochi in the Vorontsovskaya and Akhshtyrskaya caves, just where the trail over the mountains meets the coast. This would also explain why the region around Maikop initially had the richest graves—if it was the terminal point for a trade route that passed through eastern Anatolia to western Georgia, up the coast to Sochi, and then to Maikop. The metal ores came from deposits located east of Maikop, so if the main trade route passed through the high passes in the center of the Caucasus ridge we would expect to see more southern wealth near the mines, not off to the west.

By the late Maikop (Novosvobodnaya) period, contemporary with Late Uruk, an eastern route was operating as well. Turquoise and carnelian beads were found at the walled town of Alikemek Tepesi in the Mil’sk steppe in Azerbaijan, near the mouth of the Kura River on the Caspian shore.32 Alikemek Tepesi possibly was a transit station on a trade route that passed around the eastern end of the North Caucasian ridge. An eastern route through the Lake Urmia basin would explain the discovery in Iran, southwest of Lake Urmia, of a curious group of eleven conical, gravel-covered kurgans known collectively as Sé Girdan. Six of them, up to 8.2 m high and 60 m in diameter, were excavated by Oscar Muscarella in 1968 and 1970. Then thought to date to the Iron Age, they recently have been redated on the basis of their strong similarities to Novosvobodnaya-Klady graves in the North Caucasus.33 The kurgans and grave chambers were made the same way as those of the Novosvobodnaya-Klady culture; the burial pose was the same; the arsenical bronze flat axes and short-nosed shaft-hole axes were similar in shape and manufacture to Novosvobodnaya-Klady types; and carnelian and gold beads were the same shapes, both containing silver vessels and fragments of silver tubes. The Sé Girdan kurgans could represent the migration southward of a Klady-type chief, perhaps to eliminate troublesome local middlemen. But the Lake Urmia chiefdom did not last. Mos-carella counted almost ninety sites of the succeeding Early Trans-Caucasian Culture (ETC) around the southern Urmia Basin, but none of them had even small kurgans.

The power of the Maikop chiefs probably grew partly from the aura of the extraordinary that clung to the exotic objects they accumulated, which were palpable symbols of their personal connection with powers previously unknown.34 Perhaps the extraordinary nature of these objects was one of the reasons why they were buried with their owners rather than inherited. Limited use and circulation were common characteristics of objects regarded as “primitive valuables.” But the supply of new valuables dried up when the Late Uruk long-distance exchange system collapsed about 3100 BCE. Mesopotamian cities began to struggle with internal problems that we can perceive only dimly, their foreign agents retreated, and in the mountains the people of the ETC attacked and burned Arslantepe and Hacinebi on the upper Euphrates. Sé Girdan stood abandoned. This was also the end of the Maikop culture.

Valuables of gold, silver, lapis, turquoise, and carnelian were retained exclusively by the North Caucasian individuals in direct contact with the south and perhaps by those who lived near the silver and copper mines that fed the southern trade. But a revolutionary new technology for land transport—wagons—might have been given to the steppes by the Maikop culture. Traces of at least two solid wooden disc wheels were found in a late Maikop kurgan on the Kuban River at Starokorsunskaya kurgan 2, with Novosvobodnaya black-burnished pots. Although not dated directly, the wooden wheels in this kurgan might be among the oldest in Europe.35 Another Novosvobodnaya grave contained a bronze cauldron with a schematic image that seems to portray a cart. It was found at Evdik.

Evdik kurgan 4 was raised by the shore of the Tsagan-Nur lake in the North Caspian Depression, 350 km north of the North Caucasus piedmont, in modern Kalmykia.36 Many shallow lakes dotted the Sarpa Depression, an ancient channel of the Volga. At Evdik, grave 20 contained an adult male in a contracted position oriented southwest, the standard Maikop pose, stained with red ochre, with an early Maikop pot by his feet. This was the original grave over which the kurgan was raised. Two other graves followed it, without diagnostic grave goods, after which grave 23 was dug into the kurgan. This was a late Maikop grave. It contained an adult male and a child buried together in sitting positions, an unusual pose, on a layer of white chalk and red ochre. In the grave was a bronze cauldron decorated with an image made in repoussé dots. The image seems to portray a yoke, a wheel, a vehicle body, and the head of an animal (see figure 4.3a). Grave 23 also contained a typical Novosvobodnaya bronze socketed bident, probably used with the cauldron. And it also had a bronze tanged dagger, a flat axe, a gold ring with 2.5 twists, a polished black stone pestle, a whetstone, and several flint tools, all typical Novosvobodnaya artifacts. Evdik kurgan 4 shows a deep penetration of the Novosvobodnaya culture into the lower Volga steppes. The image on the cauldron suggests that the people who raised the kurgan at Evdik also drove carts.

Figure 12.12 Konstantinovka settlement on the lower Don, with topographic location and artifacts. Plain pots are Maikop-like; cord-impressed pots are local. Loom-weights and asymmetrical flint points also are Maikop-like. Lower right: crucible and bellows fragments. After Kiashko 1994.

Evdik was the richest of the Maikop-Novosvobodnaya kurgans that appeared in the steppes north of the North Caucasus between 3700 and 3100 BCE. In such places, late Novosvobodnaya people whose speech would probably be assigned to a Caucasian language family met and spoke with individuals of the Repin and Late Khvalynsk cultures who probably spoke Proto-Indo-European dialects. The loans discussed in chapter 5 between archaic Caucasian and Proto-Indo-European languages probably were words spoken during these exchanges. The contact was most obvious, and therefore perhaps most direct, on the lower Don.

Konstantinovka, a settlement on the lower Don River, might have contained a resident group of Maikop people, and there were kurgan graves with Maikop artifacts around the settlement (figure 12.12). About 90% of the settlement ceramics were a local Don-steppe shell-tempered, cord-impressed type connected with the cultures of the Dnieper-Donets steppes to the west (late Sredni Stog, according to Telegin). The other 10% were red-burnished early Maikop wares. Konstantinovka was located on a steep-sided promontory overlooking the strategic lower Don valley, and was protected by a ditch and bank. The gallery forests below it were full of deer (31% of the bones) and the plateau behind it was the edge of a vast grassland rich in horses (10%), onagers (2%), and herds of sheep/goats (25%). Maikop vistors probably imported the perforated clay loom weights similar to those at Galugai (unique in the steppes), copper chisels like those at Novosvobodnaya (again, unique except for two at Usatovo; see chapter 14), and asymmetrical shouldered flint projectile points very much like those of the Maikop-Novosvobodnaya graves. But polished stone axes and gouges, a drilled cruciform polished stone mace head, and boars-tusk pendants were steppe artifact types. Crucibles and slag show that copper working occurred at the site.

A. P. Nechitailo identified dozens of kurgans in the North Pontic steppes that contained single pots or tools or both that look like imports from Maikop-Novosvobodnaya, distributed from the Dniester River valley on the west to the lower Volga on the east. These widespread northern contacts seem to have been most numerous during the Novosvobodnaya/Late Uruk phase, 3350–3100 BCE. But most of the Caucasian imports appeared singly in local graves and settlements. The region that imported the largest number of Caucasian arsenical bronze tools and weapons was the Crimean Peninsula (the Kemi-Oba culture). The steppe cultures of the Volga-Ural region imported little or no Caucasian arsenical bronze; their metal tools and weapons were made from local “clean” copper. Sleeved, one-bladed metal axes and tanged daggers were made across the Pontic-Caspian steppes in emulation of Maikop-Novosvobodnaya types, but most were made locally by steppe metalsmiths.37

What did the Maikop chiefs want from the steppes? One possibility is drugs. Sherratt has suggested that narcotics in the form of Cannabis were one of the important exports of the steppes.38 Another more conventional trade item could have been wool. We still do not know where wool sheep were first bred, although it makes sense that northern sheep from the coldest places would initially have had the thickest wool. Perhaps the Maikop-trained weavers at Konstantinovka were there with their looms to make some of the raw wool into large textiles for payment to the herders. Steppe people had felts or textiles made from narrow strips of cloth, produced on small, horizontal looms, then stitched together. Large textiles made in one piece on vertical looms were novelties.

Another possibility is horses. In most Neolithic and earlier Eneolithic sites across Transcaucasia there were no horse bones. After the evolution of the ETC culture beginning about 3300 BCE horses became widespread, appearing in many sites across Transcaucasia. S. Mezhlumian reported horse bones at ten of twelve examined sites in Armenia dated to the later fourth millennium BCE. At Mokhrablur one horse had severe wear on a P2consistent with bit wear. Horses were bitted at Botai and Kozhai 1 in Kazakhstan during the same period, so bit wear at Mokhrablur would not be unique. At Alikemek Tepesi the horses of the ETC period were thought by Russian zoologists to be domesticated. Horses the same size as those of Dereivka appeared as far south as the Malatya-Elazig region in southeastern Turkey, as at Norşuntepe; and in northwestern Turkey at Demirci Höyük. Although horses were not traded into the lowlands of Mesopotamia this early, they might have been valuable in the steppe-Caucasian trade.39

During the middle centuries of the fourth millennium BCE the equestrian tribes of the Pontic-Caspian steppes exhibited a lot of material and probably linguistic variability. They absorbed into their conversations two quite different but equally surprising developments among their neighbors to the south, in the North Caucasus piedmont, and to their west, in the Cucuteni-Tripolye region. From the North Caucasus probably came wagons, and with them ostentatious displays of incredible wealth. In the west, some Tripolye populations retreated into huge planned towns larger than any settlements in the world, probably in response to raiding from the steppes. Other Tripolye towns farther north on the Dnieper began to change their customs in ceramics, funerals, and domestic architecture toward steppe styles in a slow process of assimilation.

Although regionally varied, steppe cultural habits and customs remained distinct from those of the Maikop culture. An imported Maikop or Novosvobodnaya potsherd is immediately obvious in a steppe grave. Lithics and weaving methods were different (no loom weights in the steppes), as were bead and other ornament types, economies and settlement forms, and metal types and sources. These distinctions persisted in spite of significant cross-frontier interaction. When Maikop traders came to Konstantinovka, they probably needed a translator.

The Yamnaya horizon, the material expression of the late Proto-Indo-European community, grew from an eastern origin in the Don-Volga steppes and spread across the Pontic-Caspian steppes after about 3300 BCE. Archaeology shows that this was a period of profound and rapid change along all the old ethnolinguistic frontiers surrounding the Pontic-Caspian steppes. Linguistically based reconstructions of Proto-Indo-European society often suggest a static, homogeneous ideal, but archaeology shows that Proto-Indo-European dialects and institutions spread through steppe societies that exhibited significant regional diversity, during a period of far-reaching social and economic change.