The Kuala Lumpur skyline from Kampung Baru

James Tye/Apa Publications

As Malaysia continues resolutely into the modern age, it remains, culturally and historically, a rich, multi-layered blend of traditions fuelled by a modern, busy and outward-looking economy. From sandy beaches, broad rivers and deep forests, to the rising skyscrapers and wide expressways of Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia is set to exceed visitors’ expectations.

Facts and figures

Peninsular and East Malaysia together cover a total area of 329,759 sq km (127,317 sq miles). The peninsula is 750km (466 miles) long and about 350km (218 miles) at its widest point. It is only two-thirds the size of East Malaysia. Some four-fifths of Malaysia was originally covered by rainforest. Of the many rivers, the peninsula’s longest is the Pahang, at 475km (295 miles). In East Malaysia, the longest river is the Rajang, at 563km (350 miles).

In the heart of Southeast Asia, Malaysia is about the size of Japan and has a population of over 30 million. The country is divided into two major regions: the peninsula, bordered by Thailand, the Strait of Malacca and the South China Sea; and East Malaysia, whose two states, Sarawak and Sabah, are located on the island of Borneo, 800km (500 miles) across the South China Sea. Sarawak and Sabah are vast regions of forests, rivers and mountains bordering the Indonesian state of Kalimantan and the sultanate of Brunei. Industry and urban society are concentrated on the peninsula, especially on the west coast, while East Malaysia is dominated by rainforests. The two regions share a hot, humid climate, but differ greatly in their population density and urban development.

Malaysia’s relative wealth is reflected in the excellent road and rail networks along the peninsula’s west coast. Its per capita income is one of the highest in Southeast Asia.

Five Kinds of Forest

Variations in soil, slope and altitude give rise to five kinds of forest:

Mangrove forest. Mangrove trees and shrubs grow on coastal marshland in the brackish zone between the sea and fresh water. An associated species is the low, trunkless nipa palm, whose fronds have traditionally been used as roofing material for coastal huts.

Freshwater swamp. Abundant fruit trees in the fertile alluvium of river plains attract prolific wildlife. Where swamp gives way to dry land, you may see the fascinating, monstrous strangler-figs.

Dipterocarp forest. Named after the two-winged fruit borne by many of the forest’s tallest trees, this dry-land rainforest is what you will see most frequently from just above sea level up to an altitude of 900m (3,000ft).

Heath forest. Poor soil on the flat terrain leading to foothills or on sandy mountain ridges produces only low, stunted trees with thick leaves.

Montane forest. At 1,200m (4,000ft) and above in large mountain ranges, or as low as 600m (2,000ft) on small isolated mountains, the large trees and liana creepers give way to myrtle, laurel and oak trees.

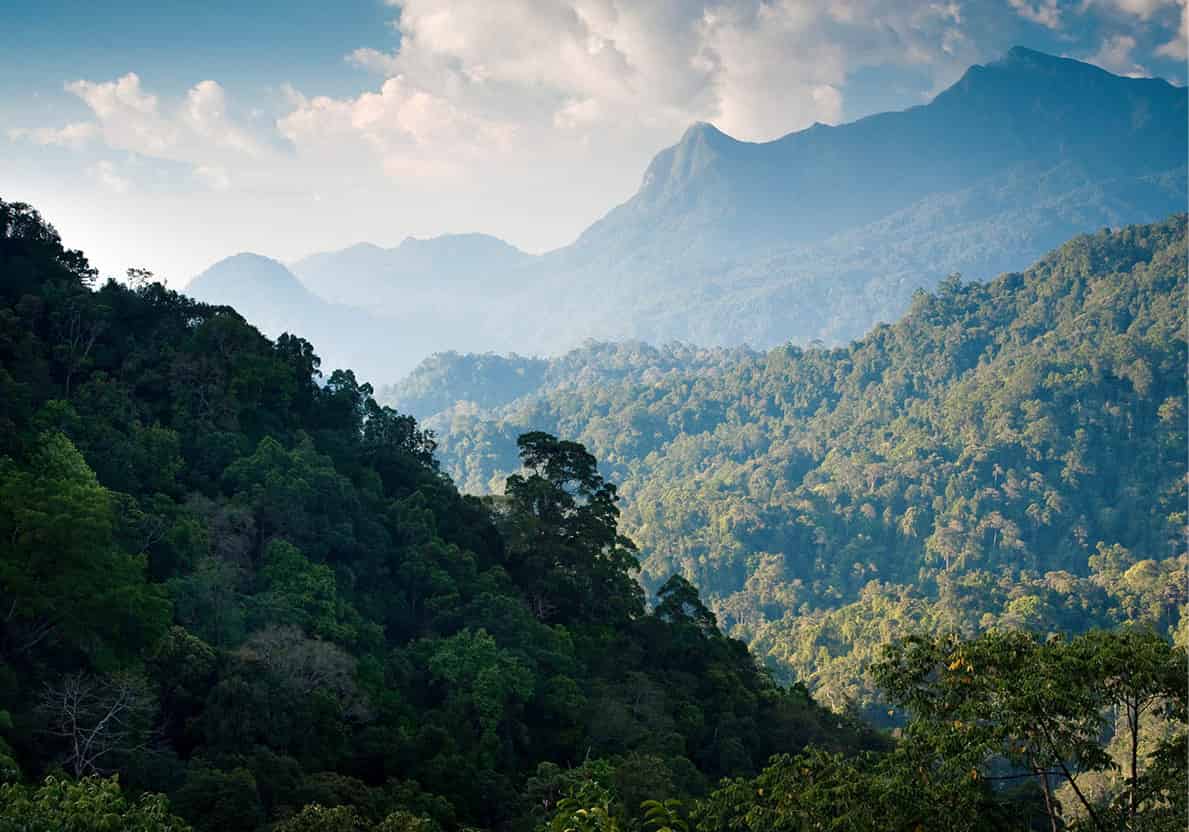

In the Cameron Highlands

James Tye/Apa Publications

Nature’s Supremacy

Whether you are staying at a beach resort or visiting a city, a stand of forest is never far away. Even in modern, urban Kuala Lumpur, you can find a forest reserve more than a century old.

The country’s prosperity has come from its coastal plains, wider on the west than the east side of the peninsula. Malaysia rose first as a trading point for Asia and Europe, with the port of Melaka (or Malacca). Then came tin mining and rubber plantations followed by palm oil, timber and petroleum and gas. Rice paddy fields in the northwest and around river deltas on the east coast, and on hillsides in Sarawak and Sabah, are where Malaysia’s rice is cultivated. Mangrove swamps along the coast and nipa palms give rise to mangrove forests. The world’s oldest rainforests engulf low but steeply rising mountain chains that cross the peninsula from east to west, with one long north–south Main Range as their backbone. Until the highway construction of the modern era, access to many forested areas had been – and sometimes still is – only by river.

Mangroves in Langkawi

James Tye/Apa Publications

In East Malaysia’s states of Sarawak and Sabah, plantations alternate with marshland on the plains before giving way to the forests of the interior. To the south, a natural barrier of mountains forms the border with Indonesian Kalimantan. Near the coast at the northern end of the Crocker Range is Gunung Kinabalu (Mount Kinabalu). At 4,095m (13,435ft), it is one of the highest peaks in Southeast Asia and popular with climbers.

With the growth of tourism, resort facilities have burgeoned in islands such as Penang, Pangkor and Langkawi on the west coast of the peninsula, Tioman on the east coast, and around Sabah’s islands off Kota Kinabalu.

To go to Malaysia without setting foot in the rainforest would be to overlook one of the essential features of the country. Sounds flood in from all sides: the orchestra of cicadas, the chatter of squirrels, the cries of gibbons, and the calls of hornbills. Animal life may be harder to spot as, unlike the wildlife of the African plains, most animals of the Malaysian rainforest are not conspicuous. Tigers and leopards remain rare, and the elephants, rhinos and bears are the smallest of their kind.

Many and Diverse Peoples

Malaysia can be proud of the continued coexistence of the three prominent peoples of the nation: Malays (usually Muslim), Chinese (mostly Buddhist) and Indians (mainly Hindu). Although there have been periods of social unrest in Malaysia’s past, people generally live in harmony, and it is not unusual to see a mosque, pagoda, temple and church all built close to each other. Another feature is the marvellous diversity in the nation’s food, with food centres often serving Malay, Chinese and Indian dishes at adjacent stalls. The country’s multiculturalism is also apparent in tribal communities like the Kadazan/Dusun of Sabah, the Iban of Sarawak (for more information, click here) and the Orang Asli people who first arrived on the peninsula at least 11,000 years ago.

The Malays, or Bumiputra (meaning ‘sons of the soil’), make up over half the population and this is reflected in Islam’s status as the national religion, with Malay – Bahasa Malaysia – as the national language.

The bulk of Malays are humble town or village-dwelling people, tending goats and buffalo, growing rice and working in the coconut, rubber, timber, rattan and bamboo industries. Just as court rituals are influenced by the ancient customs of pre-Muslim Malaya, so a mild Sunnite version of Islam is often seasoned with the ancient beliefs of animist medicine-men.

Useful phrases

Courtesy and knowledge of a little Bahasa Malaysia are always welcomed. A simple phrase such as terima kasih (thank you) is likely to be answered sama sama (you’re welcome). Other phrases can be found in the language section (for more information, click here), but just remembering selamat pagi (good morning) or selamat tengah hari (good afternoon) is worth the effort.

Religious Tolerance

To the outsider, public life in Malaysia may sometimes seem like one religious holiday after another. All the world’s major beliefs, along with an array of minor ones, are practised in Malaysia. While Islam is the official religion, most other faiths are treated with a tolerance that contrasts with ethnic struggles at the political or economic level. The free pursuit of all beliefs is guaranteed by the constitution.

Islam is observed by some 60 percent of the population, mostly Malays, but also some Indians, Pakistanis and Chinese. First introduced by Arab and Indian Gujarati traders, its earliest trace is an inscribed 14th-century Terengganu stone. From 1400, the religion was spread through the peninsula by the Melaka sultanate. Today, each sultan or ruler serves as leader of the faith in his state. Since Islam makes no distinction between secular and religious spheres, it regulates many aspects of everyday life, from greeting people to washing and eating.

Now practised by 19 percent of the population, Buddhism was introduced to the peninsula by early Chinese and Indian travellers, but only took hold when Chinese traders came to Melaka in the 15th century. With their 3,500 temples, societies and community organisations, the Chinese practise the Mahayana (Greater Vehicle) form of Buddhism, which evolved in the first century BC. A more rigorous form, known as Hinayana (Lesser Vehicle), is practised by the Thais in Kelantan, Kedah, Perlis and Penang. For most Malaysian Chinese, the Confucian moral and religious system coexists with Buddhism.

As the country’s earliest organised religion, pre-Islamic Hinduism of the Brahman priestly caste reinforced the authority of the Indian ruling class. Rituals of that era survive in Malay weddings and other ceremonies. Modern Hinduism in Malaysia has been shaped by 19th-century immigration from the Indian subcontinent. The largest contingent and most powerful influence were Tamil labourers from southern India and Sri Lanka, with their devotion to Shiva. Temples have been built on almost every plantation worked by Indian labourers.

Christians make up 9 percent of Malaysia’s population, mostly in Sabah and Sarawak. This is largely due to Catholic and Methodist missionary work from the 19th century onwards, although many of the Catholics are of Eurasian origin, dating back to the Portuguese colonisation of Melaka. Christmas is widely celebrated throughout the country and Easter is a public holiday in Sarawak and Sabah.

Despite its reputation for religious and multiracial harmony, Malaysia faces the challenge of maintaining stability. In the political sphere, rifts have deepened between fundamentalists and more moderate Muslims. Ethnic wealth gaps are also a problem. Nevertheless, Malaysia remains one of Southeast Asia’s most successful economies, and attracts tourists with its diverse landscapes and multicultural, welcoming population.