Over the centuries, Malaysia has always been able to attract incomers. Bountiful food sources may have made it an inviting place to settle. In Perak’s Lenggong Valley, archaeologists have revealed the site of the earliest civilisation in the country with the discovery of a stone hand-axe 1.8 million years old. Over in Borneo, the oldest human settlement is the Mansuli Valley in Sabah’s east coast Lahad Datu district, where more than 1,000 stone tools dating back 235,000 years have been discovered.

By 2,000 BC, the nomadic Orang Asli people, hunting with bows and arrows, were driven back from the coasts by waves of immigrants arriving in outrigger canoes. Mongolians from South China and Polynesian and Malay peoples from the Philippines and the Indonesian islands settled along the rivers of the peninsula and northern Borneo. They practised a slash-and-burn agriculture of yams and millet, exhausting the soil and imposing a semi-nomadic existence from one forest clearing to another. Families lived in wooden longhouses like those still seen among the Ibans of Sarawak. Other migrants arrived and settled along the coasts – sailors, fishermen, traders and pirates – known euphemistically as Orang Laut (sea people).

The Indian era

Between the 7th and 12th centuries AD and before the arrival of Islam, Buddhism, Hinduism and South Indian culture and language flourished in Kedah and the coasts of Borneo, which were then under the Srivijaya Empire. With its base in Sumatra, Srivijaya controlled the Strait of Malacca, a key link between the Indian Ocean and the South China Sea. The Malay language was introduced – many Malay words are derived from Sanskrit and Tamil, and some Malay social customs, especially wedding rites, reflect Hindu customs. (Malayu was also the name of a Sumatran state). What is now the state of Kedah benefited from the plough and other Indian farming practices. During the golden era, candi (Hindu temples) were built in Bujang Valley at the foothills of Gunung Jerai in Kedah and on Borneo, at Santubong.

As Srivijaya declined in the 14th century, the Malay peninsula was carved up among Siam (now Thailand), Cambodia and the Javanese Hindu empire of Majapahit. Around 1400, fighting over the island of Singapore drove the Srivijaya prince Parameswara to seek refuge up the coast of the peninsula in Malacca (now known as Melaka).

Working in a paddy field

James Tye/Apa Publications

The glory of Melaka

The Chinese were the first to spot the strategic and commercial potential of Melaka – once an infertile, swampy plain – as a harbour sheltered from the monsoons, with a deep-water channel close to the coast. In 1409, under a directive from Emperor Chu Ti to pursue trade in the South Seas and Indian Ocean, a Chinese fleet headed by Admiral Cheng Ho called into Melaka. They made Parameswara an offer he could not refuse: port facilities and financial support in exchange for Chinese protection against the Siamese (Thais). In 1411, Parameswara took the money to Beijing himself, and the emperor gratefully made him a vassal king.

Twenty years later, however, the Chinese withdrew. The new ruler of Melaka, Sri Maharajah, had switched his allegiance to Muslim traders. Islam won its place in Malaya not by conquest but by trade and peaceful preaching. Bengalis had already brought the faith to the east coast. In Melaka, and throughout the peninsula, Islam thrived as a strong, male-dominated religion, offering dynamic leadership and preaching brotherhood and self-reliance – all qualities ideally suited to the coastal trade. At the same time, Sufi mystics synthesised Islamic teaching with local Malay traditions of animistic magic and charisma, though Islam did not become the state religion until Muzaffar Shah became sultan of Melaka (1446–59).

Melaka was once a busy trading port

Hans Hofer

Yet the key figure in the sultanate was Tun Perak, bendahara (prime minister) and military commander. He expanded Melaka’s power along the west coast and to Singapore and the Bintan Islands.

By 1500, Melaka was the leading port in Southeast Asia, drawing Chinese, Indian, Javanese and Arab merchants. Governed with diplomacy by the great bendahara Tun Mutahir, the sultanate asserted its supremacy over virtually the whole Malay Peninsula and across the Strait of Malacca to the east coast of Sumatra. Prosperity was based entirely on the entrepôt trade: importing textiles from India, spices from Indonesia, silk and porcelain from China, gold and pepper from Sumatra, camphor from Borneo and sandalwood from Timor.

Portuguese conquest

In the 16th century, Melaka fell victim to Portugal’s anti-Muslim crusade in the campaign to break the Arab-Venetian domination of commerce between Asia and Europe. The first visit of a Portuguese ship to Melaka in 1509 ended badly, as embittered Gujarati Indian merchants poisoned the atmosphere against the Portuguese. Two years later, the Portuguese sent their fleet, led by Afonso de Albuquerque, to seize Melaka. No match for the Portuguese invaders, the court fled south, establishing a new centre of Malay Muslim power in Johor. Albuquerque built a fort and church on the site of the sultan’s palace. He ruled the non-Portuguese community with Malay kapitan headmen and the foreigners’ shahbandars (harbour masters). Relations were better with the merchants from China and India than with the Muslims.

The 130 years of Portuguese control proved precarious. They faced repeated assault from Malay forces, and malaria was a constant scourge. Unable or unwilling to court the old vassal Malay states or the Orang Laut pirates to patrol the seas, the new rulers forfeited their predecessors’ monopoly in the Strait of Malacca and, with it, command of the Moluccas spice trade.

A carved stone wall at A’Famosa fort

James Tye/Apa Publications

They made little effort, despite the Jesuit presence in Asia, to convert local inhabitants to Christianity or to expand their territory. The original colony of 600 men intermarried with local women to form a large Eurasian community.

Buffalo horns

The name Minangkabau roughly means ‘buffalo horns’ and is reflected in the distinctive upward curving roofs in museums and government offices built in the Minangkabau style.

The Dutch take over

Intent on capturing a piece of the Portuguese trade in pepper and other spices, the Java-based Dutch joined the Malays in 1633 to blockade Melaka. This ended in a seven-month siege with the Portuguese surrender in 1641.

Unlike the Portuguese, the Dutch decided to do business with the Malays of Johor, who controlled the southern half of the peninsula together with Singapore and the Riau islands. Without ever regaining the supremacy of the old Melaka sultanate, Johor had become the strongest regional power. Meanwhile, fresh blood came in with the migration into the southern interior of Minangkabau farmers from Sumatra, while tough Bugis warriors from the east Indonesian Celebes (Sulawesi) roved across the peninsula. The Minangkabau custom of electing their leaders provided the model for rulership elections in modern federal Malaysia. Their confederation of states became today’s Negeri Sembilan (Nine States), with Seremban as its capital.

In the 18th century, with the Dutch concentrating again on Java and the Moluccas, the Bugis took advantage of the vacuum by raiding Perak and Kedah, imposing their chieftains in Selangor and becoming the power behind the Johor throne.

British rule

The British had shown little interest in Malaya. That changed in 1786, when the Sultan of Kedah granted Francis Light, a representative of the East India Company, rights to the island of Penang and the strip of mainland coast called Province Wellesley (now Seberang Perai) as a counterweight to the demands of the Siamese and Burmese. Unlike Portuguese and Dutch trading posts, Penang was declared a duty-free zone, attracting settlers and traders. By 1801, the population was over 10,000, concentrated in the island’s capital, George Town.

In 1805, a dashing EIC administrator, Thomas Stamford Bingley Raffles, came to Penang at the age of 24. His knowledge of Malay customs and language, and humanitarian vision, made him vital in Britain’s expanding role in Malay affairs. Raffles secured his place in history by negotiating, in 1819, the creation of the Singapore trading post with the Sultan of Johor. Singapore became capital of the Straits Settlements – as the EIC called its Malay holdings, incorporating Penang and Melaka – and was the linchpin of Britain’s 150-year regional presence.

The Straits Settlements were formed after the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of London (1824). This colonial carve-up partitioned the Malay world through the Strait of Malacca. The peninsula and Sumatra, after centuries of common language, religion and traditions, were divided. The islands south of Singapore, including Java and Sumatra, went to the Dutch. Peninsular Malaysia and northwest Borneo remained under British control. From 1826, British law was technically in force, but in practice few British people lived in the Straits, and local affairs were run by merchant leaders serving as unofficial kapitans.

Apart from the few Malays in the settlements’ rural communities of Province Wellesley and the Melaka hinterland, the majority still lived inland. Unity among them and the east coast communities trading with the Siamese, Indochinese and Chinese came from their shared rice economy, language, culture, and customs inherited from the Melaka sultanate.

Province Wellesley acted as a mainland buffer for Penang, and Melaka similarly turned its back on affairs in the hinterland. When Kedah and Perak sought British help against Siam, the British took the easier option of siding with the Siamese to quell revolts. But in the 1870s, under the Colonial Office, the profits gained from exporting Malayan tin through Singapore forced the British to take an active role in Malay affairs.

The lucrative tin mines of Kuala Lumpur, of Sungai Ujong (Negeri Sembilan), and of Larut and Taiping (Perak) were run for the Malay rulers by Chinese managers and labourers. Chinese secret societies waged gang wars for the control of the mines, bringing tin production to a halt at a time when world demand was at a peak. In 1874, Governor Andrew Clarke persuaded the Malay rulers of Perak and Selangor to accept British Residents as advisors; in return, Britain offered protection.

City Hall in George Town

John W. Ishii/Apa Publications

It began badly. Within a year the Resident in Perak, James Birch, was assassinated after efforts to impose direct British control. Subsequent British advisors served on a consultative state council alongside Malay ruler, chiefs and Chinese kapitans. Birch’s successor in Perak, Hugh Low (1877–89), was more successful. Reforms he persuaded the ruler to accept included organising revenue collection, dismantling slavery and regulating land. Unity was enhanced by the growing network of railways and roads. Governor Frederick Weld (1880–87) extended the residency system to Negeri Sembilan and the more recalcitrant Pahang, where Sultan Wan Ahmad was forced to open the Kuantan tin mines to British prospectors.

A Federation of Malay States – Selangor, Perak, Negeri Sembilan and Pahang – was proclaimed in 1896 to coordinate economics and administration. Frank Swettenham became first Resident-General, with Kuala Lumpur as the capital.

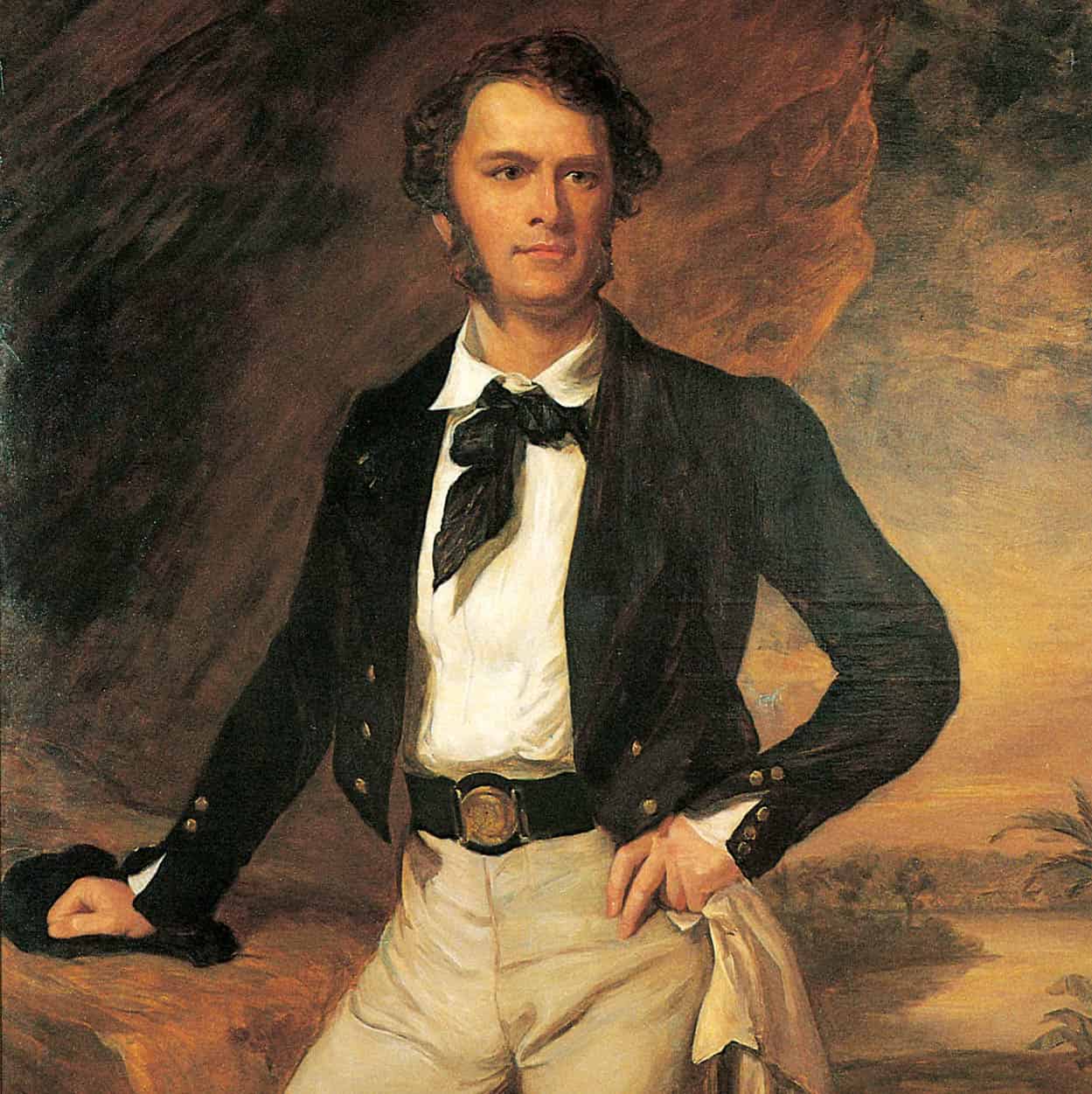

James Brooke, Rajah of Sarawak

Hans Hofer

In the 19th century, Borneo remained undeveloped. Balanini pirates, fervent Muslims, disputed the coast of northeastern Borneo (modern-day Sabah) with the sultanate of Brunei. Sarawak’s coast and interior were controlled by the Iban, Sea Dayak pirates and Land Dayak slash-and-burn farmers. The region’s only major resource was the gold and antimony mined by the Chinese in the Sarawak River valley.

In 1839, the Governor of Singapore sent James Brooke (1803–68) to promote trade with the Sultan of Brunei. In exchange for helping the regent end a revolt by Malay chiefs, Brooke was made Rajah of Sarawak in 1841, with his capital in Kuching. He tried to halt the Dayaks’ piracy and head-hunting (believed to bring spiritual energy to their communities), while defending their more ‘morally acceptable’ customs. His attempts to limit the opium trade met with resistance from the Chinese in Bau, who revolted. His counterattack with Dayak warriors drove the Chinese out of Bau. Thereafter, Chinese settlement was discouraged.

In 1863, Brooke retired, handing Sarawak over to his nephew, Charles. A better administrator and financier, Charles Brooke imposed his efficient lifestyle. He brought Dayak leaders onto his ruling council but favoured the colonial practice of divide and rule by pitting one tribe against another.

In 1877, northeast Borneo (Sabah) was ‘rented’ from the Sultan of Brunei by British businessman Alfred Dent, who was operating a royal charter for the British North Borneo Company. This region was grouped together with Sarawak and Brunei in 1888 as a British protectorate, named North Borneo.

The early 20th century

The British extended their control over the peninsula by putting together the whole panoply of colonial administration. At the same time, the tin industry, which had been dominated by the Chinese, passed increasingly into the hands of Westerners, who employed modern technology. Petroleum had been found in northern Borneo, at Miri, and in Brunei, and the Anglo-Dutch Shell company used Singapore for exporting.

But the major breakthrough for the Malay economy was rubber, developed by the director of Singapore Botanical Gardens, Henry Ridley. World demand increased with the motor car and electrical industries, and rocketed during World War I. By 1920, Malaya was producing 53 percent of the world’s rubber. Together with effective control of the rubber and tin industries, the British firmly controlled government.

The census of 1931 was an alarm signal for the Malay national consciousness. Bolstered by an influx of immigrants to meet the rubber and tin booms, non-Malays now slightly outnumbered the indigenous population. The Depression of 1929 stepped up ethnic competition in the shrinking job market, and nationalism developed to safeguard Malay interests against the Chinese and Indians rather than British imperialism.

Conservative Muslim intellectuals and community leaders came together at the Pan-Malayan Malay Congress in Kuala Lumpur in 1939. The following year, they were joined in Singapore by representatives from Sarawak and Brunei.

Japanese occupation

The Pacific War actually began on Malaysia’s east coast. On 8 December 1941, an hour before Pearl Harbor was bombed, Japanese troops landed on Sabak Beach (for more information, click here). Japan coveted Malaya’s natural resources of rubber, tin and oil and the port of Singapore. The stated aim of the Japanese invasion was a ‘Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere’, appealing to Malay nationalism to throw off Western imperialism.

Not expecting a land attack, Commonwealth troops on the peninsula were ill-prepared. The landings were launched from bases ceded to the Japanese by Marshal Pétain’s French colonial officials in Indochina and were backed by fighter jets.

Japanese infantry poured in from Thailand to capture airports in Kedah and Kelantan. Kuala Lumpur fell on 11 January 1942 and, five weeks later, Singapore was captured.

If Japanese treatment of Allied prisoners of war in Malaya was notoriously brutal, the attitude towards Asian civilians was more ambivalent. At first, the Japanese curtailed the privileges of the Malay rulers and forced them to pay homage to the Japanese Emperor. Then, to gain Malay support, the Japanese upheld their prestige, restored pensions and preserved their authority, at least in Malay customs and Islamic religion.

The Chinese were massacred. From 1943 Chinese communists led the resistance in the Malayan People’s Anti-Japanese Army, aided by the British, to prepare for an Allied return.

The National Monument in KL

Jon Santa Cruz/Apa Publications

The Japanese surrender left in place a 7,000-strong resistance army led by Chinese communists. Before disbanding, the army wrought revenge on Malays who had collaborated with the Japanese. This in turn sparked a brief wave of racial violence between Malays and Chinese.

To match their long-term stake in the country’s prosperity, the Chinese and Indians wanted political equality with the Malays. Nationalists in the new United Malays National Organisation (UMNO) resented this ‘foreign’ intrusion imposed by 19th-century economic development. To give the Malays safeguards against economically dominant Chinese and Indians, the British created the new Federation of Malaya in 1948. Strong government under a High Commissioner left powers in the hands of the states’ Malay rulers. Crown colony status was granted to Northern Borneo and Singapore, the latter excluded from the Federation because of its Chinese majority. The Chinese, considering their loyalty to the Allied cause in World War II, felt betrayed. Some turned to the Chinese-led Malayan Communist Party (MCP).

Four months after the creation of the Federation, three European rubber planters were murdered in Perak – the first victims in a guerrilla war launched by communist rebels. The British sent in troops, but the killing continued. The violence reached a climax in 1951, with the assassination of High Commissioner Henry Gurney.

Gurney’s successor, General Gerald Templer, stepped in to deal with the ‘Emergency’. He intensified military action, while cutting the political grass from under the communists’ feet. Templer stepped up self-government, increased Chinese access to full citizenship and admitted those of Chinese origin for the first time to the Malayan Civil Service.

Under Cambridge-trained lawyer Tunku Abdul Rahman, brother of the Sultan of Kedah, UMNO’s conservative Malays formed an alliance with the English-educated bourgeoisie of the Malayan Chinese and Malayan Indian Congress. During the Emergency, Chinese and Indian community leaders sought a solution. The Alliance won 51 of 52 seats in the 1955 election by promising a fair, multiracial constitution.

Independence

Independence or merdeka (freedom) came in 1957, and the Emergency ended three years later. The Alliance’s English-educated elite imagined that multiracial integration would come about through education and employment. With a bicameral government under a constitutional monarchy, the Federation made Malay the compulsory language and Islam the official religion. Primary education could be in Chinese, Indian or English, but secondary education was in Malay.

Tunku Abdul Rahman, the first prime minister, reversed his party’s anti-Chinese policy by offering Singapore a place in the Federation. With the defeat of Singapore’s moderate Progressive Party by left-wing radicals, Tunku Abdul Rahman feared the creation of a communist state on his doorstep. As a counterweight to the Singapore Chinese, he brought in the North Borneo states of Sabah and Sarawak, granting them special privileges for their indigenous populations and funds to help to develop their economies.

To embrace the enlarged territory, the Federation took on the new name of Malaysia in September 1963, but Singapore, with its multiracial policies, sought to dismantle Malay privileges. Singapore’s effort to reorganise political parties on a social and economic, rather than ethnic, basis misread Malay feelings. Riots broke out in 1964, and Tunku Abdul Rahman was forced to expel Singapore from the Federation in 1965.

Four days of racial riots in the federal capital in 1969 led to the suspension of the constitution and a state of emergency. The constitution was not restored until February 1971. The riots were a warning for the government, which was passing controversial legislation, such as the granting of special rights to Malays and the restriction of public gatherings.

Tun Abdul Razak became prime minister after the retirement of Tunku Abdul Rahman in 1970. Under his administration, emphasis was placed on improving the status of Malays and ‘other indigenous peoples’. The government’s aim was to broaden the distribution of wealth held by Malays.

The Prime Minister’s palatial residence in Putrajaya

Bigstock

On Abdul Razak’s death in 1976, Datuk Hussein Onn, a son of the founder of the UMNO, became prime minister, and UMNO became stronger just as Malaysian exports were growing. Combined political and economic strength set a sound base for Datuk Seri Dr Mahathir Mohamad when he became prime minister in July 1981.

Under Dr Mahathir, Malaysia achieved remarkable economic prosperity. Rubber and tin declined in importance, but were supplemented by palm oil plantations, discoveries of petroleum and natural gas reserves off Borneo’s north coast and the peninsula’s east coast, and developments in manufacturing and tourism. Timber, which during the 1970s and 1980s brought valuable revenue, was reduced to conserve forests. In recent years, manufacturing, particularly electronics, represented a new direction away from a dependence on commodity exports.

The 21st century

Malaysia entered the new millennium as a wealthy country with a sound economy. In October 2003, Datuk Seri Abdullah Ahmad Badawi took over the premiership, following Dr Mahathir’s retirement. In the 2008 election, the coalition government received its biggest backlash in 50 years with the opposition winning the states of Kelantan, Selangor, Kedah, Penang and Perak. Voters expressed their concern over Badawi’s leadership and his government’s lack of direction. In 2009, Najib Abdul Razak took over as Malaysia’s sixth PM, and started repairing the damage by introducing a multi-million-Ringgit campaign called ‘1 Malaysia’ to convince Malaysians that unity is a priority. In practice, however, the government continues to woo non-Malay voters and the Malay electorate with different promises. In 2013, the general elections’ result was the worst-ever for the ruling party. Despite winning the popular vote, the coalition led by Anwar Ibrahim failed to regain the two-thirds parliamentary majority. For 16 years Anwar Ibrahim dominated Malaysian opposition until in March 2015, he was sentenced to five-years in jail for, as he claims, politically motivated charges of sodomy. At the time of writing, Prime Minister Najib Razak was undergoing increasing scrutiny for corruption and use of the legal system to silence government critics.