Good Sanitation Is Good Economics: Challenges and Solutions

Regional Vice President, World Bank

IMAGINE WAKING UP tomorrow without access to sanitation. No toilet to use. No pipes to take away the waste or any system in place for that waste to be treated. And imagine having no sink or soap for washing your hands.

Hard to envision, isn’t it? Yet this is a daily reality for far too many people: according to UNICEF and World Health Organization’s (WHO) Joint Monitoring Program, two billion people still did not have basic sanitation facilities such as toilets or latrines in 2017, and of these, 673 million defecated in the open.

All too often with such stark statistics, their scale numbs us to the personal toll inflicted. That figure of two billion means that one out of every 3.5 people on the planet – mothers, daughters, sisters and wives; fathers, sons, brothers and husbands – were denied the basic safety, dignity and opportunity of sanitation.

This is why the ambitious Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 6.2 calls for ensuring universal access to safe sanitation services by 2030. Although impressive progress has been made in recent years, throughout much of the developing world achieving this goal remains a fundamental challenge. Ensuring universal access to safe sanitation services requires not only the provision of sanitation infrastructure, but also the containment of waste and its safe conveyance, treatment and disposal. The successful implementation of these interventions at scale, as we have learned from India’s Swachh Bharat Mission (SBM), is possible only with sound political will, solid public finance, strong policies and sustained people engagement to achieve long-term behaviour change.

Why Sanitation Matters

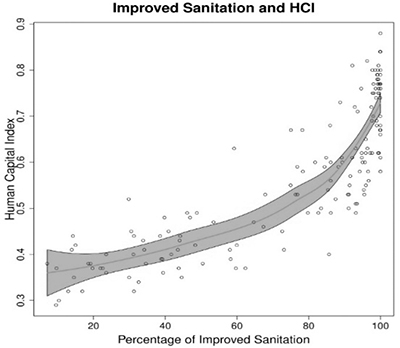

The Government of India launched SBM in 2014 because it understood the compelling economic and social reasons that justified giving priority to addressing the challenge of sanitation access across the country. The World Bank has also realized that, beyond the human dignity aspects of ensuring the availability of safe sanitation facilities to all, there is a conspicuous link between access to improved sanitation and improved human development outcomes. The World Bank’s Human Capital Index illustrates the effects that improved sanitation has on human development outcomes (Gatti et al. 2018; Figure 1 ). While the figure below does not imply a causal relationship, it convincingly demonstrates that as sanitation improves, the Human Capital Index also increases. While none of the indicators which comprise the Human Capital Index, such as health and education, explicitly includes water and sanitation, the graph clearly shows that sanitation underlies and impacts them all. As such, the World Bank realizes that sanitation can accentuate and accelerate human capital, which in turn drives economic growth, helping us tackle extreme poverty and create more inclusive societies.

Figure 1: The Relationship between Improved Sanitation and the Human Capital Index

Notes : Human Capital Index (Gatti et al. 2018); Improved sanitation (https://washdata.org/ ). R square values for linear regression models are: 0.6898. Source: Authors’ calculations. Each dot signifies a country included in the Human Capital Project of the World Bank.

Good Sanitation Is Good Economics

A large body of evidence documents why this is the case. Poor sanitation alone kills nearly 9,00,000 people per year, or around 2,460 people every day. Tragically, 56 per cent of deaths of children under the age of five are due to diarrhoea which is related to poor sanitation. Even those who survive its pernicious impacts are not spared: poor sanitation can also make people sick. For adults, it means higher health expenditures, lower productivity and reduced wages. In many countries, poor sanitation can trap households in a vicious cycle of poverty. For children, it limits their ability to absorb nutrients and imperils their physical and cognitive development, denying them the ability to accumulate human capital, and grow into healthy, productive and smart adults who can contribute more to the economy and fulfil their potential.

Girls are particularly affected. Without the privacy afforded by toilets they are more likely to drop out of school, and less likely to secure a job and participate in the economy in later life. Examples of interventions that explicitly target and reduce community levels of open defecation, such as in rural Mali, show significant effects on reducing under-five stunting (Pickering et al. 2015).

Investments in good sanitation provide some of the largest development dividends for an economy. The WHO reports that the economic return on sanitation spending is $5.50 for every $1 invested – as a Return on Investment that would be the envy of investment bankers everywhere. On the other hand, the costs of inaction are staggering. Every year, inadequate sanitation costs the world an estimated $260 billion. Clearly, investing in sanitation is an investment that pays dividends, now and in the future: the returns are high, the savings are big and the benefits to people can transform lives.

The Government of India, most notably through its pledge to end open defecation, recognizes these social and economic benefits. That’s why they have made the eradication of open defecation a priority and mobilized almost $20 billion towards the nationwide mission that began in 2014. And this is also why the World Bank is contributing to the ambitious SBM with a $1.5 billion loan, one of its largest ever, and has helped introduce a performance-based approach that links funding directly to results in the expectation that hundreds of millions of Indians can wake up and make use of a clean and safe toilet within their household compound.

The World Bank has been delighted to partner with the Government of India on SBM as the lessons from its bold approach of providing political leadership and public finance to deliver a massive programme at scale are influencing the design of Bank programmes across the world. Improved sanitation also benefits sectors of the economy dependent on water quality, such as fisheries, agriculture and services. There are benefits to the environment, too, through lower levels of surface-water pollution and groundwater contamination. Moreover, there is growing evidence, including through case studies from Senegal and Sri Lanka, that large-scale government commitment and investment in sanitation for all across the sanitation ecosystem can spur growth and vitalize local economies, creating jobs for masons and small-scale contractors who build toilets; for construction material suppliers; and for social workers and mass media who implement programmes to deliver behaviour change at scale; for a whole new grassroots industry of service providers who will maintain sanitation facilities, manage and treat septage and ensure its safe disposal into the environment.

In India, SBM has created and delivered on this opportunity for entrepreneurship at scale. The Mission has trained women across rural India and they have eagerly stepped up to become masons and increase their earning opportunities by constructing toilets (Women’s Leadership in SBM-Grameen, World Bank 2018, p. 8).

Addressing Sanitation Challenges

There is no single solution to the sanitation challenge; however, ensuring the availability of toilets at home and in public buildings is a necessary step in the development of a sanitation service chain.

Changing Mindsets

Better health and other economic impacts of access to sanitation facilities can be achieved only by the effective and sustainable use of these facilities by all members of the population. One of the lessons the World Bank has learned, not only from SBM, but also from our projects across several countries, is that it’s not just about building a toilet – it’s about changing the mindsets and encouraging people to use them. Achieving lasting behaviour and social change remains essential to sustaining the development outcomes of improved sanitation. This means tackling those ‘below the waterline’ elements of change – breaking taboos and addressing biases. After all, changing centuries-old habits of defecating in the open is a complex undertaking involving behaviour change at a deep level. Yet, examples from around the world and from SBM have shown that community-led sanitation programmes can and do change people’s behaviour around sanitation. By entrusting and empowering households and communities and building ownership around the cause of becoming open defecation free, these programmes may sustain achievements in sanitation with lasting impacts.

SBM has placed considerable emphasis on behaviour change campaigns at all levels and utilized many different channels and platforms to do so. Importantly, it provides opportunities for women to take leading roles in their communities. Women comprise roughly 30-40 per cent of the volunteers – swachhagrahis – who lead the process of triggering behaviour change at the village level (World Bank 2018, pg. 1). In addition, enlisting well-known celebrities and mass media has proven to be an effective means of disseminating important messages. The Darwaza Band mass media campaigns supported by the World Bank focus on ‘closing the door’ on open defecation and sustaining behaviour change as a community.

Toilets Alone Are Not Enough

While building household toilets outside of each home provides every family member access to a dignified service, pit latrines and septic tanks do fill up, and their waste must be treated, just like any piped sewage system. An analysis of data from 39 countries shows that 43 per cent of the human waste that is transmitted through sewers is untreated. Similarly, the sewer-connected toilet is not the right fit for every community. Such toilets require significant amounts of water and well-functioning sewer infrastructure to operate effectively. At the same time, in the absence of sewer-connected toilets, people around the world use a range of non-sewered, on-site toilet options to meet their needs. While these options safely contain human waste, they need to be linked to collection and treatment systems that ensure the removal of pathogens from the environment. The twin-pit toilets being promoted by SBM are an important and innovative technology that manages the waste on-site and also requires less water.

There are also huge opportunities for effective resource recovery – by generating energy and nutrient-rich by-products from treated waste, and re-using these for agriculture, or even the production of recycled or ‘new’ water. All of this requires creativity, technological innovation and novel ways of delivering services across the value chain – which in turn create jobs and opportunities.

Finance, Incentives and Institutions

Breakthroughs in financing models are also needed to provide sanitation as a service which responds to user demands. To this end, setting clear public policy goals and using public funds to leverage the financing and technical capabilities of the private sector, as demonstrated by SBM, are critical to accelerate the integration of disruptive thinking and the adoption of innovative approaches to deliver sanitation solutions at scale.

Several countries are implementing these ideas. In Sri Lanka, for example, the National Water Supply and Drainage Board is testing a new model of public–private partnerships for toilet improvement and septage management in four municipalities outside of Colombo. In India, large public investments in sanitation have been instrumental in building momentum for improving sanitation across the country. These examples show that there is a fundamental complementarity between infrastructure and institutions, and both are central to improving the quality of sanitation in the developing world (Ashraf, Glaeser and Ponzetto, 2016).

A Complex Challenge – But Not Insurmountable

Ultimately, investing in sanitation is about preventing needless deaths, investing in people and transforming lives. Achieving improved and safely managed sanitation for all may be a complex challenge, but the transition from open defecation to the safe disposal and treatment of waste is possible – and essential. Toilet-building combined with other factors such as social and behaviour change, maintenance and repair of toilets, waste and drainage management and treatment, re-use of by-products of treated waste for productive purposes, innovations in technology and finance along with institutional and policy reforms remain the key ingredients to help countries meet the challenge of sustained sanitation improvement.

Keeping an Eye on the Ball: Measuring Results and Impact

Global experience has highlighted the importance of effective monitoring and assessment mechanisms to measure the short- and long-term performance and impacts. The World Bank support to SBM builds such capacity at the national, state and gram panchayat levels. This includes annual monitoring of progress through a nation-wide survey, the National Annual Rural Sanitation Survey. This measures not only the availability of safe sanitation facilities, but also the sustained use of these facilities by the population. Such monitoring helps measure progress and informs when course correction may be required. Two rounds of this survey have been completed, the first in 2017–18 and the second in 2018–19, and they have shown the significant progress India has made in increasing access to sanitation in a short span of time. The World Bank is committed to supporting the Government of India in continuing these surveys to ensure that sustained and effective use is being made of the toilet facilities, so that the intended economic, social and environmental benefits of SDG 6.2 are fully realized.

Solutions to the challenge of attaining sustainable universal sanitation are available as demonstrated by the lessons and results of SBM. This is perhaps the right moment for other countries across the world to seize the momentum of SBM by providing the same level of political leadership and financing to achieve the SDG objectives of an open-defecation-free world. The World Bank is proud to support SBM and, through its Lighthouse India initiative, stands ready to build on the tremendous results of SBM and work with partners across the world to deliver a future where sound political leadership, public financing, policy direction and people’s engagement ensure that the safety, dignity and opportunity of sanitation become a reality for all.