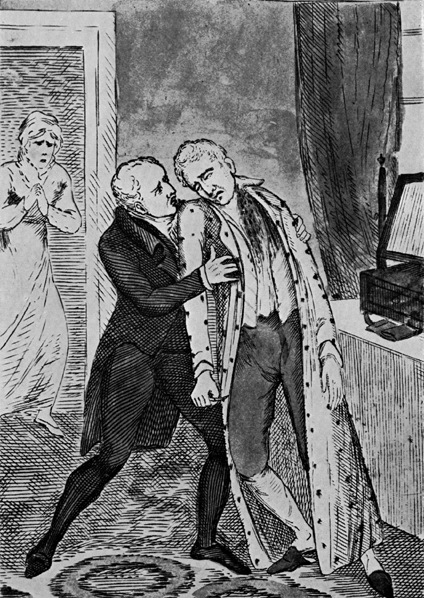

“Bankhead, let me fall upon your arm. ’Tis all over.” Frontispiece of The Strange Death of Lord Castlereagh, from a drawing, George Cruikshank, by H. Montgomery Hyde (London: Heinemann, 1959)

Amongst all the crimes that were ever produced in the world, never any yet was born equal to the horrid one of suicide; and nothing can be so shocking a prospect to men of a common sensibility, as the alarming progress and havock it has made, and is still making.1

This condemnation of suicide as the worst of crimes may perhaps be surprising to the modern ear.2 Yet many in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries would have quickly and completely agreed with it. How could perfectly intelligent and thoughtful people, in a world filled then (as now) with horrific cruelties and unspeakable deeds, consider suicide to be in the first rank of offences? A central reason was surely the widespread belief that the first law of Nature, “the first Lesson taught in Nature’s schools,” was the law of self-preservation. Poets and playwrights, philosophers, clerics, and moralists of all persuasions agreed on this, though they could agree on little else. The “Fundamental, Sacred, and unalterable Law of Self-Preservation” was the foundation of John Locke’s political thought.3 The anonymous author of Populousness with Economy of 1757 declared that “Self preservation is the voice of reason and first law of nature.” The playwright David Mallet presented it as an obvious truth: “Self-preservation is heaven’s eldest law,/Imprest upon our nature with our life,” and the popular cleric John Herries, in an Address to the Public in 1781, proclaimed that suicide was “contrary to the strongest law of nature, SELF-PRESERVATION.” The strength of this primal urge was so thoroughly accepted that, by the late eighteenth century, a long-running advertisement for a popular skin cream had as its opening headline, “Self preservation the first Law of Nature.”4

Given the widespread belief in the force of this drive, how was it possible for people either to kill themselves or to fight duels? For, in many ways, as we shall see, the campaigns to understand the reasons for and to end the practice of self-murder were strikingly similar to those employed by the critics of duelling. From the late seventeenth century, it was common for opponents of suicide to see it as the other face of duelling, or duelling “as a kind of Self-Murder.” Both duellists and suicides, claimed John Jeffery in a sermon of 1702, by their practices, attempt to revive “the obsolete knight errantry of barbarous antiquity in our enlightened days.” The conjunction of these vices furnished the title of a tract of the late 1720s, Self-Murther and Duelling the Effects of Cowardice and Atheism. In it, its author claimed that these activities were sacrifices “to some of the meanest Vices and Passions that belong to Human Nature, viz., the Rage of Resentment, a cloudy Discontent, and a profane Tempting and Distrusting of Providence.”5 In addition, both duellists and well-born suicides seemed to avoid the penalties of the law, and, as MacDonald and Murphy point out, “suicide could serve the same function as the duel among men of honour.”6 Therefore most thought that only through a total abrogation of the normal human equilibrium, brought about by insanity in some cases, by decadent indulgence in the case of the suicide, or by a willful giving-in to the basest and least human passions, in duelling, could this imperative be overcome. This often unspoken, but underlying belief in the centrality of self-preservation would give shape to much of the discussions and debates of the eighteenth century about these two related vices.

Having considered why so much attention was given to this act, this chapter will examine the sorts of evidence that we have of what people thought about suicide during the long eighteenth century. This will begin with a survey of the notions and representations of suicide during the reign of the first two Georges, before considering the extent, nature, and impact of press accounts of such events. We will attempt to canvas the many popular opinions expressed in the press about the motives for suicide. Finally we will look at two important bodies of writing that dealt with such acts—the body of medical thought on the relation of suicide, insanity, and medical competence, and an equally important mass of legal views of suicide, of its legal ramifications and general consequences for the polity. Following a consideration of proposed changes in punishments for suicide at the century’s end, we will conclude with a case study, the press responses to the suicides of some prominent early nineteenth-century men, and with changes in the law governing suicide.

2nd clown: “Will you ha’the truth on’t—if this had not been a gentlewoman, she should have been buried out o’ christian burial.”

1st clown: “Why, there thou say’st: and the more pity, that great folk should have countenance in this world to drown or hang themselves more than their even Christians.”8

When a person was found to have died in surprising or mysterious circumstances, a coroner’s jury was supposed to be called to decide on the cause of death. Though there were several possible inquest verdicts on the death of someone found dead unnaturally, ranging from accident to visitation of God, the two most common at the beginning of the eighteenth century were felo de se or conscious and willful self-murder, self-murder in cold blood we might say, and lunacy, non compos mentis, an unintended act which occurred when the person was deranged, with blood and brains boiling. If one were adjudged felo de se one could not obtain Christian burial, and, depending on the circumstances, the burial might be degrading and shameful to friends and relations. Also, as in other cases judged felonious, the possibility remained that the estate of the deceased might be forfeit to the Crown. Yet, throughout the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, most suicides (and all such deaths of “great folk”) were declared lunatic, and given Christian burial. As with the vice of duelling, to which suicide was often compared and conjoined, eighteenth-century juries not only refused to impose the full weight of the law against these, but seemed, by never finding them criminally culpable, to exculpate the self-destruction of the Great.

Nevertheless, through this period, a prolific and overwhelmingly negative outpouring of printed materials condemned the practice on a number of grounds. The excoriation of the act of self-murder rested on three “planks” which resembled, not surprisingly, the criticisms of duelling. The first, and most obvious perhaps, was that by killing oneself one brought woe and disgrace upon one’s family, one’s aged parents and innocent children. Even if one were alone and entirely solitary, many reasons still remained for not committing this final outrage. For, in several ways, suicide was seen as weakening the polity in which one lived, in depleting the cohesiveness and attacking the principles on which it rested. Suicide, it was said, was “contagious,” and if unpunished, would lead to copycat acts. Only the fear of a frightful punishment could deter others from following such fatal example. When a juror refused to find the proper harsh verdict in a case of self-murder, he had not only committed perjury, but “the doing what in him lies toward the incouraging Self-Murder in Others also.” Only by punishing such acts with “a Mark of Infamy” was it possible to “deter others from the like inhuman and detestable Practices.”9 Second, suicide weakened the bonds of civil society by denying the very grounds of, and reasons for, its existence, i.e., the preservation of life. Therefore, according to the popular pulpit-thumper “Orator” Henley:

for if we may murder ourselves, we may soon be induc’d to think that of others is not unlawful; it defeats the Force of human Laws; for where is legal Punishment, if Self-Murder be warrantable? it opposes the Reasons for which the Murder of others is forbidden, as the having no Authority, depriving the State of a Subject, the Impossibility of making an equivalent Satisfaction.

If each was left to “judge his cause and redress his fancied wrongs,” argued a Norwich clergyman, “anarchy the consequence would be.” The danger that unpunished suicide posed to civil society was so great and so widely felt, that even a letter in the London Journal which argued against the common notion that self-murder was an act of cowardice still agreed that it was “highly suitable, and in political Societies, absolutely necessary, to oppose and discourage all we can”10 this fearsome practice.

However, the strongest and most enduring criticism of the practice throughout the period was based, not surprisingly, on religious grounds. Now, it should be pointed out that no one condemned those who, plagued by obdurate insanity, killed themselves under their afflictions. While these sorts of death were regrettable and cause for sorrow, they were part of the ills the flesh was heir to, and thus not culpable. Neither were such deaths thought to constitute the greatest part of all self-murders. Only people “who rid themselves of their Being, as a perfectly reasonable Action … and as simply preferring, in their Circumstances, Death to Life” were considered to be particularly heinous, particularly dangerous and sinful. Thus a late seventeenth-century writer thought the prevalence of suicide was “a great Proof of the Degeneracy of the Age,” especially since “there are so many Christians who do such Violence to themselves.” Zachary Pearce, Bishop of Rochester, in a sermon against suicide, took as his text the injunction “that it is our Duty to receive Evil as well as Good, at the hand of God.”11 Many religious writers argued that people’s lives were not their property, to dispose of as they liked. Either men and women were to consider themselves as “so many hir’d Servants, set on Work by our Great Master Above, who hath set out our labour to us.…” or, even more strongly, that only God was the absolute proprietor of men’s lives, and therefore a man has “a Right of Use over it, not of Propriety; a Power to employ it to that End for which he receiv’d it, and may therefore hazard, but not himself destroy it.”12 God’s property in human lives and destinies could not, in this view, ever be superseded or set aside. To protect his property, God implanted in all peoples what we have already seen described as “the first law of Nature,” i.e., the desire for self-preservation. Thus, willful self-murder was seen to be not only ungodly but unnatural.

If suicide was such an atrocious act, how could some men and women bring themselves to commit it? In addition to the moral contagion we have already considered, a number of other reasons were adduced to explain how this could happen. Despite MacDonald and Murphy’s view that, in an increasingly secular age, suicide (like duelling) was explained by natural, physical causes rather than by supernatural temptations, many contemporaries still argued that the Devil and his minions were active in seductions to suicide.13 There were, of course, some few in the first six decades of the eighteenth century who thought that the act of suicide always arose from illness; a correspondent to the London Magazine noted, in his “Reflections on Suicide” that, like many other illnesses, the melancholy leading to suicide was due not to demonic possession, but to physical disorder; “many diseases, which were formerly ascribed to supernatural causes, and regarded with a superstitious reverence, are now found to submit to the powers of medicine.” The weight of opinion, however, seemed otherwise, the anonymous author of the Occasional Paper, for example, arguing that if the suicide “was at that Instant beside himself,” this did not “take away the Guilt of it.… For he ought to have been otherwise, and to have restrain’d his Passions in time, e’re they brought him into that Fury.”14

Most writers on suicide held that the act had always been most common “precisely in those periods, and in those communities in which impiety and profligacy were most prevalent.” Modern, like ancient suicides, were due to “Impotence of Mind and Dissoluteness of Manners, together with a general Ignorance or Disregard of the Law of Nature.”15 But the relation between irreligion and self-murder was complex, and a variety of connections were discussed. Most dismissed the influence of English weather on suicide rates, but some thought that an English love of freedom and equality were indeed to blame. A much-copied essay, for example, explaining why “the English are more liable to this Crime than other People,” attributed it to the fact that all ranks of English men and women, believing themselves “equal and free,” could not cheerfully bear either subservience or the reversals of fortune. Others thought that the moderns, misled by an exaltation of Roman suicide, were fooled into the practice. The devil, claimed the author of the Occasional Poems, “will stir up some subtile Instrument/That Crime of Suicide to represent/As if it were a Roman, Manly Fact/A daring, brave, and a courageous Act.” And especially after the success of Addison’s play Cato, with its sympathetic portrayal of heroic self-sacrifice and self-destruction, most opponents of suicide argued against this example. Even a decade after its first performance, this play was thought to have had a powerful, negative influence.

Those Authors who have wrote either directly or indirectly in favour of Self-Murther, have (as ’tis to be feared) contributed not a little to the Frequency of this horrid Fact. Among the latter I am sorry that I’m obliged to place the ingenious Author of the celebrated Play call’d Cato.…16

And, regardless of the play, when the facts of Cato’s life were considered, observed the editor of the Universal Spectator, it would be seen that he “acted on false Principles, deceiv’d himself with a mistaken Notion of Honour, and that which is celebrated for an Heroic Virtue, was nothing but the Effects of Fear and a sullen Pride.”17 But most laid the blame squarely on two interrelated moral flaws or sins, on overweening pride and an overreliance on the power and veracity of human reason.

“Pride,” said Thomas Knaggs, “is the predominant Vice that Reigns among us, and it is so radicated by Time and Custom, that I am afraid, it lies too deep in the Hearts of many to be easily swept away.” And, in 1756, in an article in the Gentleman’s Magazine (a magazine which MacDonald and Murphy characterize as polite society’s arbiter elegantiae) entitled “Pride the chief Inducement to Suicide,” the same theme was spelled out at length.18 Thus, through the first half of the eighteenth century, this sinful pride was often connected with the fallacious notion that a man could properly conduct his life by the light of his reason alone. “O Reason,” apostrophized one correspondent, “false, delusive, specious Name! What art thou, but Ignorance, Pride, Fancy, Whim and Chance.” The failure of ancient Stoicism, argued John Jeffery, proved the weakness of unaided human reason against the pressures and passions of life; by itself reason could not deter the commission of suicide, and thus needed legislative assistance “to press the duty a feared conscience will not see.” One writer went so far as to suggest that this over-valued reason was, “amongst the learned and thinking part of mankind,” the chief inducement to suicide: “It is the groundless conception, that man, by his natural powers, is able to sustain himself in the most trying circumstances, and even to work out his own salvation, that is the cause of vast misery to human creatures.”19

In an age when deistic writings were not uncommon, but were much feared for their corrosive impact on what were perceived to be virtues supported by religious sanctions and faith, the obvious ensemble of relationships among intellect, pride, irreligion, and suicide were often drawn. Two cases especially provided instances or examples of such connections. The first, and one of the most widely written-about suicides of the entire eighteenth century, was the disturbing deaths of Richard and Bridget Smith, who killed themselves after dispatching their sleeping infant. Richard Smith was a bookbinder by trade and clearly a literate, philosophically engaged person. He was confined with his family in King’s Bench debtor’s prison. Neither the fact of the incarceration, nor even of the self-murders could have been so unusual as to merit the judgment of the Gentleman’s Magazine, that their deaths were “the most melancholy Affair … heard of for many Years.” In fact, what made this such a cause célèbre were the letters that the Smiths left behind, both as practical requests and a sort of testament to the loftiness of their minds. Even today, reading these, one can sense both their enormous pain in the life they were leaving and their proud resolution in the face of adversity. Proclaiming a belief in a wise and good first-mover, they noted, however, that “this Belief of ours is not an Implicit Faith, but deduced from the Nature and Reason of Things” and because it was their opinion that since such a benevolent being could not possibly “Delight in the Misery of his Creatures” they felt justified in killing themselves “without any Terrible Apprehensions.” Not surprisingly, “the Coroner’s Jury found them both guilty of Self-Murder … and they were both buried in the Cross-Way near Newington Turnpike.”20 Many years later Voltaire referred to this case in his Philosophic Dictionary, as did Richard Hey, more than half a century later, in his Dissertation on Suicide. It was this case, and the suicide of Eustace Budgell in 1737, that were probably responsible for the outpouring of articles in the journals and newspapers of the decade on this topic.21

In her book on Victorian suicide, Barbara Gates has called the Budgell affair “one of the most notorious suicides of the eighteenth century.” Budgell, a cousin of Addison’s, and a contributor to the Spectator, took his life in 1737. The causes for his suicide are unclear; all we know is that he left a note on his desk that read “What Cato did/And Addison approved/Cannot be wrong,” and drowned himself. He was widely held to have been a free-thinker, and his death was described as of the same sort as those of earlier deists, Charles Blount and Thomas Creech. His sad end was referred to not only a few months after his death in the journals of the day, but by the great Cham himself, Samuel Johnson. When Johnson discussed suicide with Goldsmith and Boswell, he noted that once a man had resolved to kill himself, there was nothing to stop him from doing any harm or evil. Thus, he argued, when “Eustace Budgel was walking down to the Thames, determined to drown himself, he might, if he pleased, without any apprehension of danger, have turned aside and first set fire to St. James’s Palace.”22

The phenomenal growth of the periodical press and the continuing spread of literacy after 1700 transformed the hermeneutics of suicide, just as they affected almost every other aspect of social and cultural life.… [The press] also carried news of suicides to a vast audience of readers and enabled them to form their own judgments about them.23

These two dramatic cases, however, were quite unlike the run-of-the-mill press reports of self-inflicted deaths through the first six decades of the eighteenth century. When we get such accounts, they tend to be both very brief and cryptic, neither condemnatory nor exculpatory, usually emotionless statements of fact.24 Two such reports, both coming from Fog’s Weekly Journal, are good illustrations of the brevity and flatness of tone so common in the press notices of this period. The first and longer of the two, is an account of the death of

Hugh Hunter, who keeps the Crown Inn or Livery Stables, in Coleman Street for many Years, being reduc’d in his Circumstances, it caused such disorder in his senses that he hanged himself last Thursday se-’nnight in the morning at his Bed’s Feet. The Coroner’s Jury sate upon his body and brought him in a Lunatick.

The second story was of “one Clarke, a broker in Shoe lane, [who] upon some Discontent, shot himself in the Belly and dy’d soon after. There was a Woman in the Room when he did it.” Sometimes the press gave a reason for the act, such as the belief that Woolaston Shelton, “the youngest cashier of the Bank,” had killed himself because of “some concerns he had with Messrs. Woodwards, the Bankers.” Most, however, were explained merely with the phrase “some Discontent of Mind.”25 And, as far as I have been able to find, no newspapers reported the felo de se of anyone of “family” (with one exception, which we will discuss in chapter 5); such deaths were, and continued for a long while to be, glossed over and misrepresented. Thus, for example, when the Duke of Bolton killed himself in 1765, the London Evening Post merely reported that “Yesterday … after a short illness, his Grace, the Duke of Bolton” died at his house. Only in Horace Walpole’s letters do we get the real story. In a letter to his friend Mann, Walpole remarked, “The Duke of Bolton t’other morning, nobody knows why or wherefore, except that there is a good deal of madness in the blood, sat himself down upon the floor in his dressing room, and shot himself through the head.” Walpole then went on, “What is more remarkable is, that it is the same house and the same chamber in which Lord Scarborough performed the same exploit.” According to Walpole, Richard Lumley, Earl Scarborough had also shot himself in 1740: however, the press at the time merely noted that he had “died suddenly … of an apoplexy.” Walpole commented that “Suddenly, in this country, is always at first construed to mean, by a pistol.”26 However, by the 1760s, though the Great were still being shielded in this way, press reporting of ordinary suicides, as of duels, was becoming more frequent and fuller.

One of the lengthiest and most curious of all these articles was the lead story in the Gentleman’s Magazine of September 1760, entitled “Some Account of Francis David Stirn.” This story, which ran six full pages, told of the life and death of a talented young German, who, coming to England around 1758 in pursuit of employment, ran into a variety of difficulties, largely because of “his jealous and ungovernable temper.” Conceiving a deadly hatred for his last employer, a Mr. Matthews, he first challenged him to a duel, and then when Matthews refused to fight, shot him point blank. Stirn was tried and found guilty of murder, but defeated the hangman by taking poison and killing himself. This tale was told with a great deal of circumstantial detail, and with considerable sympathy for Stirn’s situation as a very bright and able man forced to swallow his pride and accept (at least in his own mind) insult and rejection from his employer. It ended, however, with a moral and a warning to those like Stirn, “whose keen sensibility, and violence of temper” might lead them to murder and suicide: “If, by this mournful example, some of these shall be warned gradually to weaken their vehemence of temper by restraint … neither Stirn” nor his employer “will have died in vain.” Here is a fine example of the contrarieties of eighteenth-century thinking about suicide—sympathy for the man, but not the deed, and a firm belief that passion and temper could be brought under control by the force of habit and God’s mercy.27

With few exceptions, the newspaper accounts of suicides of this period did not give the victims’ names, even if they were not of the ton. And, although this is more a “hunch” than a fact, it certainly seems as though, through the 1760s, those suicides that had some interesting personal appeal or some eccentricity had a better chance of being featured in the press. In 1765 alone we have six reports of suicides, of which five had some unusual feature or human-interest element. One of these, the death of a gentleman who had previously served as high sheriff of “a certain county,” was unusual because he was reported to have been found felo de se; the second concerned a gentleman who killed himself on the eve before his marriage “to a very amiable young lady of 10,000l. fortune”; the third was about “a young lady, elegantly dressed, [who] threw herself from a boat into the Thames” because of a stepmother’s cruelty; the fourth described a woman harshly treated by her husband who, after passing a sociable evening at cards with a party of friends, “shot herself thro’ the head,” and the last, a Scot fleeing his creditors was caught by them on a boat to France, and threw himself (and the ship’s master) overboard.28 These stories exhibit neither horror nor bereavement, they were neither moralistic nor sympathetic, but, like stories about two-headed calves and other natural oddities, seemed to cater to a widespread appetite for unusual or curious happenings.

In contrast to the rather bland tone of the reporting of actual suicides were the poems about suicide that various contributors sent to the newspapers and magazines. All the instances of these I have found employ poetic techniques designed to raise horror and to instill a proper repugnance for the foul deed. Thus “Belinda,” writing to the Morning Chronicle, noted that since that paper “made room a few days since for some lines said to be written by a gentleman who put a period to his own existence,” she sends along what she describes as “an antidote to the poison” of those lines, an excerpt from Edward Young’s Night Thoughts. In his poem Young portrayed suicides as “selling their rich reversion … to the Prince who sways this nether world” and when they grow sick of their condition, “with wild Demoniac rage” they kill themselves. Young argued that “the deed is madness; but the madness of the heart.” Another letter, signed “B,” sent to the Westminster Magazine, quoted both Pope and Blair to illustrate the iniquity of self-murder; for those who kill themselves, Blair prophesied that “Unheard of tortures/Must be reserved for such.” Finally, the Gentleman’s Magazine, in its review of the poems of Thomas Warton, published his “The Suicide,” as that piece, which once read, will make the reader wish for more. The poem begins with an invocation of the life and self-murder of a failed poet, and his lonely untended grave on the moors. Then, lest the message be lost in the sympathetic tearfulness of it all, an angelic voice breaks into the poet’s reverie, warning him to “Forbear, fond bard, thy partial praise;/Nor thus for guilt in specious lays/The wreath of glory twine.” In these popular poems, the reader was invited to sympathize perhaps, but quickly to step back, to bewail the doer, but not the deed, to understand that the madness of the heart was culpable and demonic. Though MacDonald and Murphy agree that “none of these poets condoned suicide,” they nevertheless hold that their “sentimentalization of death inspired pity for self-slayers and eroded the revulsion that suicide had formerly inspired.” I can find little evidence to support their contention.29

Through the 1770s and 1780s (and, in some cases beyond) when well-known or powerful people killed themselves, not only were their deaths often presented as due to natural causes, but perhaps because of medical complicity, their bodies often seem not to have come under the notice of the coroners’ juries. Two of the most famous of such instances were the deaths of Charles Yorke, Chancellor of England, and of Robert Clive, the great Nabob of India. When, just a few days after accepting the Chancellorship, Yorke killed himself, the first reports in the press merely noted that on Saturday the 20th, at five in the afternoon, the Right Honourable Charles Yorke, Lord High Chancellor, had died at his home, but remarked that “the immediate cause of this gentleman’s death is differently reported,” citing fever and cold, an overstrong emetic or a “scorbutic eruption” as some of the proffered explanations. Most of the press settled on the undoubtedly true immediate cause of death, that Yorke had died “by the rupture of a vessel inwardly.” And, in two of the leading monthly magazines a poetical epitaph appeared almost immediately, perhaps family-sponsored, which concluded with the lines “Here Heaven clos’d the temporary scene; and snatched her Favorite, to celestial Honours.”30 Similarly, four years later, when Robert Clive took his life, the press noted only that “Last Tuesday night died the Right Honorable Lord Clive.…” When the press speculated on the cause of his death, the most they could come up with was “a nervous disorder of the stomach.” But the causes of this last death, despite the press whitewashing, was clearly known to some of the public, for it evoked a powerful and angry front page letter from “A poor Man with a good Conscience,” published in the Morning Chronicle just four days later. Comparing these “late circumstances in the world” with the deaths of classical heroes like Cato and Brutus, the writer wondered how it was possible that “we who have a better religion than the Romans, have worse principles and less refined sentiments.” Unlike the ancients who died for love of their country, modern men killed themselves “to avoid the pain and ignominy of an enquiry into our conduct, or to decline surviving the loss of an overgrown fortune, extorted from people by barbarous usage and indiscretion.”31 This clear reference to Clive’s life and death shows that, for one person at least, the omission of the facts of the nature of Clive’s death prevented disapproval neither of the act nor of the man. These two deaths continued to be talked of in a conjoined fashion, even though, ostensibly, no one knew they were suicides. Thus, in the Town and Country Magazine of May 1778, there appeared A Dialogue in the Shades between Lord C[live] and the Hon. Mr. Y[ork], which openly admitted the nature and discussed the causes of their self-inflicted exits. After the two met in the after-world, they concluded that “ambition has been the ruin of us both,” though both agreed that “many of the leading men” of the day “envy us our present situation; but want the courage to shew themselves Catos.” A much blacker, fuller, and more interesting piece, which we shall consider in more detail later, also made reference to Clive’s suicide, albeit it was published fifteen years after the fact. Complaining of the unfairness of coroners’ juries in finding only poor people felo de se, “J. A.” expressed a hope that

the next Eastern plunderer, debauched lord, or corrupt commoner, who, in his sober senses, makes use of a pistol as a remedy against the tedium vitae, or the stings of a guilty conscience, may meet with a jury so uncomplaisantly mindful of their oaths, as peremptorily to doom them to all the penalties of a felo de se, which no after-connivance may set aside.

Another correspondent to the Gentleman’s Magazine wrote in with regard to the life of Clive as published in Kippis’s Biographica Britannica. Criticizing this biography as an attempt to gloss over Clive’s “most tyrannical cruelty” which led, “Academicus” suggested, to his untimely and self-inflicted death, he said: “The judge [of the dead] there [in the after-life] is not long to be flattered by ambition, soothed with pleasure, or bribed by riches, but he rises to take ample vengeance.”32

This letter reminds us that eighteenth-century readers took the opportunity to write in to the press when they disliked or disagreed with something they had read, heard, or felt. Though the press had a fairly consistently negative attitude toward the topic of suicide in the abstract, when readers discerned what they deemed a “palliation” of the act in a particular suicide account, they wrote angry responses to the journal. Thus when, in November 1784 a loving and gentle obituary of the writer Theodosius Forrest appeared in the Gentleman’s, a response was swift in coming. Criticizing the mildness of the treatment of Forrest’s death, “HOC,” quoting the lines from Hamlet cited at the beginning of the previous section, agreed with Shakespeare, but argued that the same severe justice must be shown to all those who killed themselves.33

We have looked at the death of Clive, surely the Eastern plunderer referred to by “J. A.,” but what of the debauched Lord or corrupt commoner that he also cited? In the self-inflicted death in 1776 of the Honorable John Damer, eldest son of Lord Milton, we have a fine example of the former, and in the suicides of Samuel Bradshaw in 1774 and John Powell in 1783, outstanding examples of the latter.

When the Morning Post first announced the death of Damer on the day after his suicide, it reported that he had died at his house in Tilney Street, Mayfair, and gave no further information. This polite untruth about the place and manner of his death was soon set aside and the London press indulged in an orgy of hints and innuendoes, honoring Damer’s high-born status, however, either with oblique references to him as “the unfortunate gentleman,” “a certain man of fashion” or the “unfortunate Mr. D—.”34 Who could resist the tale of the young aristocrat, heir to £30,000 a year, who spent his last moments in a pub in Covent Garden, drinking with “four women of the town” and a blind musician? All the papers hinted at dissipation: the loss of a sum of money said one, the granting of annuities said another, being of a “turn rather too eccentric to be confined within the limits of any fortune,” said a third. The Morning Post, as befitted its reputation as London’s premier scandal-sheet, gave several reasons, ranging from “the unfortunate temper” of his wife, which “had long been a bar to their domestic happiness” to the “profusion of his table” which “was ill suited to an annual income of five thousand pounds.”35 Yet, at the end of the day, perhaps most significantly, the inquest jury found Damer to have committed the act in a state of lunacy, and therefore neither criminal nor to be punished.

More surprising perhaps were the similar verdicts on the self-murders of Bradshaw and Powell, two important, unpopular, though non-noble government officials. Of Bradshaw the London newspapers merely reported that he had died at his home, “after a few days’ illness.” But in the next month’s issue of the London Magazine the secret was given away. In an extraordinary article entitled “The Character of a late Placeman,” its author, using the standard dashes instead of spelling out Bradshaw’s name, not only negatively assessed his life but also revealed the secret of his death, though he attributed his self-murder to “a dejection of mind, and melancholy.” Comparing Cato’s crime with Bradshaw’s, the writer noted that “that the former was a man, the latter was but a minister’s man.” Perhaps Grafton, “his” minister, performed a last kindness for his “man” and saved his family from the embarrassment of an inquest jury.36

Ten years later, when John Powell, a self-made man like Bradshaw, the cashier at the Pay-office, killed himself after being dismissed from his government employments, and under Parliamentary investigation for peculation, he was less lucky than Bradshaw in evading a coroner’s inquest. His death was also correctly and minutely reported by both the daily and the monthly press, and evoked interesting comments from correspondents. While “X.Y.’s” letter to the Gentleman’s Magazine was very guarded, it is quite possible that he, and others, felt that Fox, Burke, and Rigby had generously exaggerated the extent of Powell’s mental derangement and thus “X.Y.’s” comment, that “suicide is too much the fashion of the present day to be considered only as an act of a lunatic!” was a condemnation of the exculpatory verdict of insanity. A similar, delicately worded complaint appeared in the Gazetteer of May 30th, 1783: its author suggested that the “increase and fashion of suicide is such that the Legislature should extend the penalties, and confiscate the property of the self-murderer, whether the verdict of the Coroner be or be not Lunacy.”37

This reticence of the press either to report, except in the briefest comment, the suicides of men of family and position, or to comment on those deaths, like Yorke’s, Clive’s, and Bradshaw’s, which may never have been brought before a coroner’s jury,38 or those like Damer’s and Powell’s, which did come to such a trial, but were mitigated, was a mark of the sensitivity of the issue, of the general shamefulness about the act that people felt, and the sense that the press tacitly agreed that the hoi polloi had no business in judging the lives or deaths of their betters. Perhaps the press developed a code to signal, without having to say so, that a person had killed himself. In several cases the newspapers described the deaths merely as “sudden,” as Walpole had suggested. Of the thirteen suicides mentioned by Horace Walpole, only six appeared in the press as people who took their own lives. Lamenting the detailed though quite sympathetic account that the World printed of the suicide of Lord Say and Sele, Walpole, in a letter to Hannah More, bemoaned the degeneracy of the modern press; “They now call it a duty to publish all those calamities which decency to wretched relations used in compassion to suppress, I mean self-murder in particular.”39

Suicide not only appeared obliquely in the press, was the subject of many sermons and pamphlets, and featured in poetry, but it was also debated and discussed at least twenty-one times through the last three decades of the century at nine of London’s commercial debating societies. The questions raised dealt with the issue of Cato’s death, wondered whether suicide was an act of courage or of cowardice, and asked whether it proceeded most “from a Disappointment in Love, a State of Lunacy, or from the Pride of the human Mind?” Unfortunately we have the votes in only three of the debates, and these are inconclusive and contradictory. Still, this was a topic that people wanted to talk and hear about, especially in 1789, the year in which one debating society declared that there had been “a late alarming number of Suicides” and claimed that “fifty-three suicides were reported in the newspapers within the month” of October alone.40 Perhaps spurred by this popular enthusiasm, perhaps responding to what was perceived to be a growing incidence of suicide, the press in the late 1780s began fulsomely to report on many of the suicide cases of the day, especially when they involved “public” figures, people who moved in the “great” world, who fell from eminent heights to the depths of despair and death. Such stories had more color and drama, more popular appeal—elements that no commercial venture like the highly competitive daily papers could afford to neglect. These stories often contained some heart-wrenching detail—the last acts of the deceased, the letters left behind, the grief of an agonized widow, the generous tribute of mourning friends. This only served to increase the stories’ impact, and, of course, to sell more papers.

While the tone of these stories was not condemnatory but somber, neither was it generally mitigating or exculpatory. At best the press usually explained the fatal act as an instance of general luxuriousness, of the badness “of the times” or just threw up its hands, arguing that the cause was unknown. When the journals and papers discussed the topic of suicide abstractly or generalized from specific instances, their comments were harsher and more one-sided. Thus, a letter in the Town and Country Magazine from “Anti-Suicide” contained the bald assertion that “few if any, have been driven to the deed by insurmountable distress.” In the twenty-two periodical pieces I have found on the topic which discuss the reasons for suicide from 1772 to 1797, the two most common causes cited were the over-gratification of the passions and desires, and the fear of shame or contempt. Thus an article in the Lady’s Magazine, by “a young physician” argued that “… the gratification of every sensual desire, if carried beyond the bounds of reason, is attended with a proportional degree of subsequent uneasiness or pain” and for this reason assigned, as the first cause of suicide,“[e]xpectation, elevated above the bounds of prudence and reason, disappointed; as in the respective cases of love, honour, riches or any other predominant passion.” A letter from “Plato” to the St. James’s Chronicle agreed; “Despair, indeed, is the natural Cause of these shocking Actions [of self-murder]; but this is commonly Despair brought on by wilful Extravagance and Debauchery.”41 The second motive, fear of contempt, might spring from apprehensions of imprisonment, execution, or merely the loss of honor. Thus a correspondent writing to the Morning Chronicle noted that those who killed themselves frequently “steal a death, perhaps in prison, to avoid the scandal of a public execution, to avoid the pain and ignominy of an enquiry into our conduct, or to decline surviving the loss of an overgrown fortune, extorted from people by barbarous usage and indiscretions.” A comment in the Times agreed:

The numerous Suicides we have in this country, are a melancholy proof of the depravity of the mind, as they in general arise from the fear of encountering the inquisition of justice, from despair at obtaining the object sought for,—or from remorse of conscience at the recollection of some mischief done to a fellow creature.

And at least two military men left notes with the phrase “Death before (or preferable to) dishonour!” and killed themselves.42

I have found only four instances in anything published in the press in the later eighteenth century which argued that the suicide in question had been a noble act, or that suicide was the irresistible result of illness, mental or otherwise. Let us look at these examples, and then consider the widely reported, much lamented, but discreetly and clearly condemned death of George Hesse. The first piece, entitled “Thoughts on Suicide” by “Cato,” appeared in the Sentimental Magazine in 1775. It was an effusive attempt to evoke sympathy for those “whose real life misery renders their continuance in life a tremendous hydra” and expressed a hope that “the God of Immortality” would not doom such suicides to eternal perdition. The second, an essay by James Boswell in The Hypocondriack, playing on the same sentimental tone, argued that

people of humane and liberal minds cannot feel the same indignation against one who has committed Suicide, that we feel against a robber, a murderer, or, in short, one who has daringly counteracted a clear and positive command … [for those who kill themselves] have generally their faculties clouded with melancholy, and distracted by misery.

The third, which appeared as a newspaper article, was much of the same sort. Entitled “Suicide, a Fragment,” this was a Sterne-like, “man-of-feeling” type of piece, apostrophizing the suicide of James Sutherland, who had been the judge-advocate of Minorca until suspended from that position in August 1780, by its governor. Three years later he won a case against that governor, General Murray, and was awarded a £5000 settlement. By 1791, according to the Annual Register, he was “reduced … to great distress,” and on August 16th of that year he killed himself in front of the carriage carrying the King. When a laudatory account of his life and death appeared in the Times, it was filled with long dashes, with exclamations and rhetorical questions à la Sterne. Presenting Sutherland as a rational and conscious suicide, it compared his act to that of Brutus and Cato, and argued that “there are situations in which death is preferable to life—.” The piece concluded by noting that Julia (a character hitherto absent in the fragment) had said that she “would rather be the dead Sutherland, than the living man who caused thy misfortunes.” This, the author concluded, demonstrates that “her heart, like thine was intersected by some of the finest fibres of nature—and when sensibility touched one of them, the whole vibrated to the centre.”43

The fourth piece, published almost exactly a year later, was a curious reflection on suicide in both England and Geneva. After a beginning which seemed to blame suicide on the absence of a belief in “the soul’s immortality, and a future state,” and which castigated “those philosophers … who have endeavoured to shake this great and important conviction from the minds of men, … thereby open[ing] a door to suicide, as well as to other crimes,” its author confessed that “there is a disease sometimes which affects the body, and afterwards communicates its baneful influence to the mind … render[ing] life absolutely insupportable.”44 These four instances, along with the letter to the London Magazine which was earlier cited, are the only statements I have found which express neither horror nor blame, or which see the act as either noble or caused by disease. An examination of the various accounts given of the suicide of George Hesse will illustrate the extent and limitations of a medicalized and sympathetic public response to this act.

When Hesse, bon vivant and friend of the Prince of Wales, killed himself on June 2, 1788, the newspapers, after a brief hiatus, eagerly covered the story. The Times explained the delay in reporting this death by confessing they had “from delicacy suppressed” the news. But two days after the event, the papers were full of it. On the whole, the early accounts were factual and non-judgmental, merely stating the time, place, and manner of death, and Hesse’s activities on the evening preceding his fatal decision. They also remarked on the coroner’s verdict, which was lunacy. The second reports, a day later, expressed sympathetic pity, noting that “every one who knew him, must pathetically lament—and those who knew him not, sincerely pity” his fate. However, even here, much more space was given to a fiscal reckoning of Hesse’s road to advancement, wealth, and prosperous marriage, than to compassion. His father had secured him a place in the office of the paymaster general, and in the years after, he had advanced as government agent to the forces, “so that his official income amounted annually to the sum of fifteen hundred pounds.” Added to this was the “liberal fortune” brought to him by his marriage with the daughter of a West-India merchant. Clearly, in terms of the goods of this world, he was a man particularly fortunate; the long catalogue of his wealth and offices made such comment unnecessary. How shocking it must have been then to read that Hesse had killed himself because “his pecuniary affairs, from deep play, had, it appears, sustained a shock of the most momentous nature—and from which he expressed his apprehension, that he could not speedily extricate himself.”45 Other papers, however, did not refrain from making pointed comments, even while discussing Hesse’s “very liberal and fine feelings.” A paragraph repeated in several papers alluded to what, it was thought, had led to this disastrous situation: “Some connexions too splendid not to be broken, and too high not to dazzle, may have led him astray.” Hesse, one observed, “had very early a propensity for gay life” and it was this desire to live with and like the Great that led to his downfall.46 In its next issue, the General Evening Post continued their exposé of Hesse’s failings, while simultaneously lamenting the fact that his death had “too prematurely deprived society of one of its most amiable and accomplished ornaments.” Noting, however, that this “unhappy gentleman” (as was not unusual; negative comments about important people did not mention them by name) “possessed, in places, estate and interest of money, very near three thousands pounds per year,” the paper concluded that “this, without children, surely was enough for all the elegant conveniencies of life.” It was a “too strong propensity” for the “pernicious practice of gaming” that led him to lose £50,000 and his own life.47 The Star and Evening Advertiser added yet a further “wrinkle,” recounting a perhaps fictitious story of a practical trick that had been played upon him by his high-born friends, which, according to the paper, “contributed to convince him he was rather permitted to enjoy the high intercourse which in the end produced his lamentable fate, than deemed a partner in it.” One paper, the Morning Post, underlined the moral of this sad fable even more sharply:

We are afraid, however, from some expressions which dropped from the unhappy man a few days before, that the coldness with which he had been treated by some of those elevated connections, which he seemed particularly to court, was too much for his feelings, as he foresaw, in this high neglect, the rapid desertion of every other society above the level of his own rank.

The Morning Post went on to connect his suicide, or, as they described it, “his aweful farewel,” with his desire to tread “the delusive and dangerous paths of greatness.”48 Finally two poems written to commemorate Hesse exemplify the ambiguities felt by the press, and probably by their readers, about the death of this likeable man. The first, entitled On the Death of Mr. Hesse, was all praise: it extolled “The virtues of the man, who’s now the saint!/For merit sure he shar’d in ev’ry part,/Merit most true—the integrity of heart!” The second poem, published in the Town and Country Magazine, ended with the lines “Altho’ restrain’d by tender ties,/Into Eternity he flies!/A lesson leaving to the gay,/To tread with care life’s slip’ry way.”49

Whatever the truth of these constructions of Hesse’s death, their point was clear and made even stronger and more acute when, a day after the event, another “gentleman … of some distinction in the county of Middlesex,” identified only as A—k—n, killed himself, it was said, because of “some heavy losses which he sustained at Ascot races.” Several of London’s newspapers printed the same concluding paragraph to this story, which linked suicide not with mental illness but with moral decay:

The progress of bankruptcy and that of suicide seem to keep pace with each other—and both are to be ascribed to the same causes, dissipation, extravagance, and speculation. No matter whether the speculation is in trade, on the course at Newmarket, or in relying upon one’s connexions with the great.50

Thus sympathy could be mixed with criticism, humane fellow-feeling with condemnation. And though there is no doubt that sentimental portrayals in verse, the novel, and the theater became very popular during the last four decades of the century, there is no reason to think that this taste was carried over and looked for in newspaper stories. For most eighteenth-century newspaper readers, the experience of consulting their daily report was quite unlike that of reading a sentimental novel; the latter was designed to invoke strong feelings, to draw tears, to serve as a holiday retreat into a world of overheated emotions and acts. Though they lacked our developed literary understanding of genre differences, eighteenth-century readers knew that a novel was not a newspaper account, and that “real life” was not to be confused with light reading.51

Used more and more frequently, it [the non compos mentis verdict] was the tangible expression of the secularization of suicide, of the opinion that self-destruction was in itself an act of insanity, an end more to be pitied than to be scorned.…

The leading legal authorities of the day protested against the lenient interpretation of psychiatric evidence.… The lawyers were worried that juries’ disregard for the rules of law would undermine the rule of law.52

It was well known at the time, and has been reaffirmed ever since, that, starting in the later seventeenth century, coroners’ juries, faced with the bodies of those who had killed themselves, came increasingly to decide that such deaths were the result of lunacy, and therefore not culpable. Of course, some were still found felo de se,53 but the vast increase of mitigatory verdicts requires some explanation. MacDonald and Murphy conclude, “At some point during the mid-eighteenth century the men of middling rank who served as coroners’ jurors adopted the medical interpretation of suicide.”54 But it might repay a few moments’ consideration to examine eighteenth-century medical opinion on the nature and causes of suicide and lunacy, and to speculate on the circumstances and influence of such changing ideas.

We have already seen the dismissal of supernatural causes in favor of medical insight in an article in the London Magazine of 1762, but, in this context, it is worth revisiting this piece and considering the pivotal importance here given to the medical professional. In the second part of the same essay, published in the journal’s next issue, its author advised the friends and relations of possible suicides “to remark the first approaches of the disorder; and to apply immediately to some able physician; for the least delay in these cases is particularly dangerous.…” The young physician-correspondent to the Lady’s Magazine maintained, despite his opinion that suicide was frequently caused by over-gratified sensual desires, that suicide was now generally understood as a disease and “ranked amidst the number of those which every regular physician does, or ought, to pay attention to; and as mental complaints are in many instances the objects of our practice, from their intimate connection with the body …,” and therefore that the services of a doctor were vital. William Rowley, noting that changes in people’s physical constitutions could also lead to changes in their mental states, added that “[p]hysicians have frequent opportunities of observing the diminution of human courage and wisdom from long-continued misfortunes, or bodily infirmities.… The man is then changed, his blood is changed; and with these his former sentiments.”55 By 1808, a correspondent to the Gentleman’s Magazine confidently stated that suicide was always the result of lunacy, the conclusion of “all such medical men who have for many years devoted that time and attention to the development of the disease termed Insanity, which it greatly merits.…” That doctors, especially “mad-doctors,” increasingly subscribed to the notion that suicide was caused by mental derangement, is undoubtedly true; what is less clear is how compelling their views might have been to the men who composed coroners’ juries, men familiar with the expanding world of claimed medical expertise, men who may have thought that such assertions of particular insight into the roots of suicidal impulses was part of what has been dubbed the “medicalization” of insanity.56 For, in the eighteenth century, insanity and all its circumstances became a growth industry, with mad doctors doing much to insist on a need for trained medical expertise and for an expanded role for their professional assistance.

What other bodies of thought might have influenced coroners’ juries to arrive at lunacy verdicts? The concern frequently stated through the eighteenth century, which MacDonald and Murphy have so cogently expressed, that the actual workings of inquest juries would undermine the rule of law, was the widely shared view of many moralists, whether lawyers or not. Commenting on such decisions, many contemporaries felt that the refusal of juries to find people felo de se, like the refusal of juries to find duellists guilty of murder, undermined the credibility of the English legal system and the confidence of men and women in English justice. The comparison with duelling broke down at this point, however, for while a duellist theoretically could be punished, it was impossible to punish a suicide. Yet juries continued to find lenient verdicts, even as commentators continued to lambast their decisions. Could this very discomfort with mitigation have been responsible, at least in part, for the continuance of the practice that gave rise to it?

The unease with coroner’s juries was based on several grounds. Late seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century commentators thought that coroners’ juries had misunderstood the true meaning of lunacy, and therefore found verdicts incorrectly. The Occasional Paper, for example, believed that where “a Man is capable of Rational Actions in other respects, the Law justly supposes him capable of having us’d his Discretion in this [act] also.” A constant and total state of derangement was clearly the only criterion for finding a verdict of non compos mentis, according to law. John Jeffery made a similar point, linking the impropriety of mitigatory verdicts for suicides with the assessment of the culpability of duellists. Coroners, he argued “willfully mistake the already named false estimate of things for reason’s full decay: otherwise they must, in some degree, upon duellists (nay other culprits) pass the same decree; what yet they never do, and why? but that here no confiscations are made to take place, at least, which is not a little strange, since the crimes appear of equal dye.”57 Such criticism did not end in the mid-century. Thus, in one of the most frequently cited texts of the eighteenth century, Sir William Blackstone explicitly argued against the view “that the very act of suicide is an evidence of insanity.” In volume four of his Commentaries on the Laws of England, a volume entitled “Of Public Wrongs,” he concluded that suicide is properly ranked as “among the highest crimes.” Blackstone noted that if one interpreted insanity in a tolerant manner, “as if every man who acts contrary to reason, had no reason at all,” then this argument would overthrow all law, “for the same argument would prove every other criminal non compos.” And even in 1829, when a new guide to the duties of the coroner and his jury was issued, written by the Lord Chief Justice of the Court of Common Pleas, John Jervis, Blackstone’s comments on suicide were included virtually word-for-word.58

Even more troubling than what might be innocent mistakes or kindly meant mitigation was the widely shared belief, whether rightly or wrongly held, that the verdicts of coroners’ juries could be purchased, that, as a consequence, there was one law for the Great and another for the small. In a funny mock-serious advertisement inserted after the death notices in the Gentleman’s Magazine of 1755 there is an account of a cheap, painless, and untraceable “medicine” to help “men of pleasure” kill themselves. This cure is offered as an alternative to the usual practice:

AND WHEREAS such is the prejudice still remaining among the great and little vulgar, that this necessary and heroic act reflects indelible dishonour upon such men of wit, honour and pleasure, and their families, and makes the experience of bribing a coroner’s jury to perjury absolutely necessary, to prevent a forfeiture of their personal estate, if any such there be … the advertiser offers his potion as an alternative, cheaper solution.

In the same year, this charge was seriously and forcefully made in A Discourse against Self-Murder by the Anglican clergyman Francis Ayscough. Commenting on the notion that suicide is itself a mark of insanity, he wondered

… what is it that the Jury is called together to enquire into? The Truth is, they are called together to keep up the Formality, and to set aside the Spirit and Intention of the Law; to receive, I am afraid, a stated Fee for a directed Verdict; in plain Words, to be bribed, and to be forsworn.

Thus, indeed, is to charge on them a high Degree of Wickedness. But if it be true, it ought to be spoken, and if it be not so, I would only ask—How comes it to pass, that no Man of Rank and Fortune was ever subjected to the Penalties of this Law.…59

This charge went beyond the commonly recognized fact that, in this, as in every other facet of eighteenth-century life, social position mattered. Thus the Connoisseur, in a popularly reprinted issue, commented on this inequality:

… of hundreds of lunatics by purchase, I never knew this sentence [felo de se] executed but on one poor cobler, who hanged himself in his own stall. A penniless poor dog, who has not left enough to defray the funeral charges, may perhaps be excluded the church-yard; but self-murder by a pistol genteely mounted, or the Paris-hilted sword, qualifies the polite owner for a sudden death, and entitles him to a pompous burial and a monument setting forth his virtues in Westminster-Abbey.60

But what was merely hinted at by many, that money had actually changed hands, that the coroner and/or his jury were bribed by friends or family to find the correct verdict, i.e., non compos mentis, was also unambiguously made. Sometimes this allegation was thundered from the pages of the press, sometimes more coyly and matter-of-factly included in contemporary journal stories. In “She Met Her Match,” a moral tale published in the Town and Country Magazine in 1773, a Mr. Portland killed himself because of marital infelicity, whereupon “Mrs. Portland, when she had bribed a coroner to bring in a verdict of lunacy, proceeded to the opening of her husband’s will.” MacDonald and Murphy point out, quite correctly, that such “[b]ribery has left few records, for obvious reasons.” However, they also note before dismissing the charge, that “[s]ome critics complained that bribery was widespread.” Citing Defoe’s opinion “that it was less important than sympathy in securing favourable verdicts,” they conclude that they “are inclined to agree with him.”61 A brief reconsideration of this point may be in order.

In Sleepless Souls, MacDonald and Murphy tell the story of the one coroner’s verdict they found, the report of the inquest on the body of Edward Walsingham, on which someone had made a note stating that the verdict was paid for by his family. I also have found such a case, but have much more evidence than just that rather obscure notation. My source is from the voluminous correspondence of Margaret Georgina, first countess of Spencer. In 1780, in a letter to her oldest friend, Mrs. Howe, Lady Spencer made a curious inquiry. Lady Spencer, an aristocrat and a correspondent to the Bluestocking circle, was a woman of quiet, though deep-felt religious conviction. It is her exemplary moral character, well noted by contemporaries, that makes her request so odd and interesting. Telling her friend of the suicide of Hans Stanley on their estate, Lady Spencer recounts a letter she had received from Stanley’s family, asking her to “pay off” the coroner. Here is the nub of Lady Spencer’s problem; she expresses no hesitation about the act itself, or about corrupting the legal system, but wonders instead how much money should change hands, and requests that Mrs. Howe ask her acquaintance for such information. If someone as truly Christian and morally upright as the Countess could treat the suborning of a jury as a standard, everyday sort of practice, this, I think, lends weight to those eighteenth-century contemporaries who saw this as a widespread practice.62 By the late 1780s this practice had become so common as to be denounced in a letter to the Gazetteer. Why, asked the writer, do candidates for the job of coroner “spend a thousand pounds to obtain their election? What is their object?” His answer is plain: “[t]hey are inspired by hopes of eventual emoluments.”

A great man may commit suicide; to save the forfeiture of his property it must be brought in Lunacy. The jury (who, God knows, are seldom philosophers) are persuaded that insanity, and self murder are convertible terms.—The deceased’s relations are satisfied with the verdict of the jury, and the Coroner with the price of it.63

Just two months before, the Times reported that a coroner’s jury had found a certain nobleman’s brother felo de se, and they hailed the verdict. The Times expressed a hope, that though the verdict was “a matter of regret” to the family “that this rigour may operate, as it ought, in prevention of the crime.” If, it added three days later, “the burial in a public highway, and the stake, was put in force against a very few suicides of rank, the crime of self-murder would soon be extinguished.”64 This was never reported as happening, however. The weight of such comments, as well as the Spencer example, though not an irrefragable proof of the widespread nature of such corruption, still convinces me that Defoe was, in this instance, uncharacteristically trusting.

The strongest and most coherent newspaper letter on the laws concerning suicide was one which I have already cited, published in the Gentleman’s Magazine in 1789, and signed only “J. A.” Arguing for a repeal of the law of suicide, this correspondent stated his strongest objection to its operation.

[T]his is one of those few instances in which that equal distribution of justice to all ranks of people, which is the greatest boast of our country, is violated. It is violated too, I fear, in a very heinous manner, namely by direct perjury on the part of juries; thus contaminating the very source of all public justice.

Though “J. A.” did not directly refer to the bribery of coroners or their juries, he did note “that coroners’ juries have often been influenced to bring in false verdicts.” Referring to those lines of the second clown quoted at the beginning of an earlier section, “J. A.” hoped that “a little serious consideration will convince every one, that partiality in the administration of justice, and the violation of a solemn oath, were evils of no small magnitude.” This was neither a conservative nor a traditionalist speaking: “J. A.’s” argument was for an amelioration and improvement of the entire criminal law, beginning with a repeal of this particular aspect of it.65

Thus jurymen, moved either by instructions from their coroner, or by ideas picked up from the press about the corruption and venality of other unspecified coroners, might well have been willing to find the great majority of suicides who came before them to have been non compos mentis. This may have meant for these jurors, that men and women with no resources to expend, no bribes to tender, no friends to forswear, were deemed no less innocent of crime than those other suicides, equally culpable but richer or better situated.

We have looked at a range of opinions about and representations of suicide in a variety of popular venues, and seen much dissatisfaction with the way that suicides were dealt with by the agents of the law. What proposals however, were made for a more effective, more humane, or more egalitarian process in dealing with such cases?

For most of the writers on suicide in the popular press from the 1730s through the 1780s, the answer was unambiguous; a misplaced sympathy with the families of the deceased and the corruption of the law by the families of the Great, had caused a diminution and corruption of the proper treatment of the self-murderer—dissection and display. The classical cases were frequently cited as examples of how suicide might be curtailed: if the virgins of Miletus stopped killing themselves when the corpses of some of their more resolute sisters were dragged through the streets, why would this not work equally well in London? Some suggested that special charnel houses be established to display the remains of suicides, with engraved accounts of their deaths and decorated with “the glorious Ensigns of their Rashness—the Rope, the Knife, the Pistol or the Razor.”67 Shaming rituals continued to be supported as a method for diminishing the number of suicides: rather than burying a suicide “in a crossroad and a stake driven through the body,” ventured “Humanitas” in a letter to the New Monthly Magazine, “might it not act more in terrorem if the body were given to the Royal College of Surgeons for dissection?” Not only would this cause a decline in the incidence of suicide, but, argued “W. T. P.” in a letter to the Gentleman’s Magazine, “it would probably supply the want of the Profession, and stop the trade of the resurrection men.” Even correspondents like “Ordovex” who, in 1818 wrote a letter on suicide to the Times, commented that while he did not “approve, in an unqualified manner, of the penalties assigned by our law to this crime,” he thought it imperative that “some signal and indelible mark of infamy be attached to the memory of that man who has wantonly become the murderer of himself; let his name be raised as a beacon, to warn away others from the same fatal shoal.” Though he did not refer to him by name, perhaps “Ordovex’s” proposal owes something to the compromise position adopted by Richard Hey, in his Dissertation on Suicide of 1785. Hey proposed the abolition of the forfeiture of property as a punishment for all suicides, but, at the same time he advocated that “no regard should be paid to Lunacy, but that, in all cases, alike, some certain Mode of treating the Body of the deceased should be invariably observed, and some certain Marks of Infamy affixed to his Memory.”68 Hey’s proposal may have rested upon the view, expressed two decades before, that “[t]his clause of the law [the expropriation of property] indeed, is now seldom put into execution.” Arguing that “the untimely death of a cottager or mechanic must occasion more exquisite distress than that of a peer or senator (for very few consider the indigent as proper objects of consolation),” the author of Reflections on Suicide concluded, like Hey, that justice demanded an equitable and equal treatment of all suicides.69

Others thought persuasion might have some effect, especially if it were serious in tone and religious in content. A correspondent to the General Advertiser advocated that every minister should deliver an annual sermon “on the causes and cure, or consequences of temptations, to self-murder” and another, to the Times, concurred: “Should not our Divines frequently make this the subject of their pulpit discourses? If they did it would have its good effects.” Still others hoped that their published inquiries into the history of ideas about suicide would have some positive influence on its prevention; in this spirit Charles Moore stated his wish that his Full Inquiry into the Subject of Suicide would be of use

to instruct the ignorant, to persuade the wavering, to uphold the weak, to caution the unwary, to guard the avenues through which youth and inexperience must pass, and to confirm and strengthen every previous good inclination to moral and virtuous habits.70

Many, however, thought some change necessary in the law, either in how it was enacted or how it was enforced. Most of the discussion resolved itself to one of two positions: some people seemed to think the law as it stood was fine, but that its enforcement was inadequate, and others thought the law itself was too stringent, too barbaric, and needed to be modernized and tamed. In addition, there were those who thought that coroners and coroners’ juries needed a clearer idea of what the state of non compos mentis involved. If some guidelines could be laid down, juries’ verdicts could be more uniform, less liable to outside interference, and thus more equitable.

We have already seen that many contemporaries believed that coroners and their juries were corrupt and could be bribed to return the correct, exculpatory verdict. In addition to this perhaps overly cynical view, there were many who just could not understand how inquests could reach their verdicts. Though the Morning Chronicle’s comment on such decisions was a bit too facile and tongue-in-cheek, it betrays the kinds of confusion that many must have felt in reading accounts of suicide verdicts in their daily papers.

The proofs of lunacy required by Coroners’ Juries are among the most extraordinary phenomena of the law of evidence. Within these six months, the following have been considered as decisive.—Speculating in the funds—believing in Lord MALMESBURY’S mission—leaving off a course of physic—paying debts (this was in the case of a nobleman)—not being able to obtain a seat in Parliament—having a very bad wife—going to church three times a day—talking Greek in a fruit-shop—and being neglected by Mr. Pitt!

But by the early nineteenth century, public opposition to this condemnatory view of the coroners’ juries was also finding public voice. In a letter to the Gentleman’s Magazine entitled “The Disease termed Insanity little understood,” its correspondent took umbrage at “the stigma thrown upon our Juries by the term “fashionable verdict of Lunacy” and denounced such slurs as “very undeserved.” Similarly, writing about the suicide of Abraham Goldsmid, the Examiner noted that it was “a most difficult task” for any jury to decide “whether the unhappy suicide was in his senses or not. The Jury, therefore, with much propriety and feeling, in all such cases of doubt (99 out of 100) bring in a verdict of lunacy.…” Furthermore, added a correspondent who signed himself “Medicus Ignotus,” not only was it difficult to tell real self-murder from acts of lunacy, but also “the disease of the mind is totally out of the reach of all bodily remedies” and therefore its unhappy sufferer can in no way be considered culpable.71

Both those who stressed the difficult but real medical causes of suicide, those who thought inquest juries correct in their verdicts, and those who did not, but wished for a stricter and less expansive understanding of lunacy, desired a change in the law. Thus Richard Hey condemned the leniency of coroners’ courts. “Juries,” he argued, “in opposition to Law, have shewn a compassionate attention which, in the deceased person, both Law and private Duty had called for in vain.” Charles Moore’s impressive and much cited Inquiry agreed that the mistaken kindness of the juries had a significant and deleterious social impact. “It is self-evident then, that the abettor of suicide,” and by this Moore meant inquest juries, “undermines the basis of all civil society, that he defies all threatenings of law and terrors of judicial process, and consequently that the executive authority loses by these means its firmest hold over the decent and regular conduct of its dependents and citizens.”72 In this view, if law was partial, was corrupted or corruptible, whether through humanity or bribery, it ceased to have the authority needed for maintaining a safe and fair society. The clash of these points of view occurred frequently during the Napoleonic and postwar period, and was still raging when, in 1818, Sir Samuel Romilly took his life.

When Sir Samuel Romilly, Member of Parliament, eminent civil lawyer, crusader for the abolition of the slave trade and a reduction in the severity of the criminal law, killed himself on November 2, 1818, London’s newspapers were filled with the story. In the following weeks, the story of Romilly’s demise continued to be discussed as the press published not only reports of the inquest, details of the funeral, the contents of his will, and the implications of his death for the political situation, but also poems, editorials, and letters to the editor eulogizing his life and bemoaning his death. Seldom has the demise of a non-royal received so much public attention. Let us examine these posthumous comments on Romilly’s life and the manner of his death, before turning to another suicide in public life, which occurred only four years later, that of Robert Stewart, Lord Londonderry.

We have considered that body of thought that argued that all suicides were the result of mental illness, and should thus be treated medically rather than as criminal acts, and have also noted a remaining widespread horror and disgust, a fear and revulsion toward the act and its consequences. Since Samuel Romilly both killed himself, and was enormously loved and respected, in the accounts of his death we can observe early nineteenth-century writers attempting to come to terms both with the man and with his heinous end.

It is instructive to consider press reports of the mourning occasioned by Romilly’s death. It was said that “never perhaps was a more sincere tribute of respect and veneration paid to an individual, than what was exhibited on Tuesday morning in the two Courts of Equity.” The Lord Chancellor, glancing at the spot where Romilly normally had stood, “could no longer restrain his feelings; the tears rushed down his cheeks; he immediately rose and retired to his room, to give vent to his feelings.” But grief spread far wider than the courts; the loss of Romilly, “that incomparable person … filled the metropolis with sorrow.” It was, judging from press reactions to popular upset, as if a terrible national calamity had occurred. “We have never witnessed a sensation at once so strong and so general as what at this time occupies all minds.” But to judge his death merely as a national disaster did not seem enough for some commentators. Thus one writer, noting that “his death is indeed a great national calamity,” went on to add that the loss was “not confined to his country, for the range of his mighty and extraordinary mind encompassed every class of his fellow beings.…” Rather than his death being presented only as that of an exemplary Englishman and an ardent advocate of improvement, it was described as having “given a shock, wholly without example, to every heart which cherishes a hope for the advancement of its species.”74 By these accounts Romilly appeared as a species-hero.

The qualities most lauded posthumously were threefold. Romilly was mourned for three sorts of excellencies: as an uncorrupted law-maker and politician, as a self-made man of business and endeavor, and as an exemplary family man, a father, husband, and son. Described as a patriot and sage, lauded for “the purity of his intentions” and characterized by his “love of constitutional liberty,” in his public capacity Romilly seemed to exemplify a particularly valuable and perhaps rare sort of man. These attributes of the statesman were matched by his devotion to his profession, and his success at it. The press repeatedly insisted that though Romilly’s father, a jeweler, had given him a good education, “all the rest had been achieved by himself.” He was a model of the rewards of hard work and industry, having “acquired those habits which usually promote health and success in life.…” Rising early, he caught “those moments for improvement, which others too often waste in indolence.…” Known as a “most indefatigable labourer,” he was widely praised for his “knowledge, learning and eloquence.”75 In a phrase redolent of his philosophic mentor, Jeremy Bentham, the Constitution summed up his life as “useful.”76