Abbreviations

AR |

Annual Register |

Bing |

Bingley’s Journal |

CGJ |

Covent Garden Journal |

CM |

Craftsman, or Say’s Weekly Journal |

Conn |

Connoisseur |

DA |

Daily Advertiser |

FFBJ |

Felix Farley’s Bristol Journal |

Fog’s |

Fog’s Weekly Journal |

Gaz |

Gazetteer |

GEP |

General Evening Post |

GM |

Gentleman’s Magazine |

LC |

London Chronicle |

LEP |

London Evening Post |

Lloyd |

Lloyd’s Evening Post |

LM |

London Magazine |

LP |

London Packet or New Lloyd’s Evening Post |

MC |

Morning Chronicle |

Mdsx |

Middlesex Journal |

MH |

Morning Herald |

MP |

Morning Post |

Public Advertiser |

|

St. J |

St. James’s Chronicle |

T&C |

Town and Country Magazine |

White |

Whitehall Evening Post |

1. Observator December 31, 1709–January 4, 1710; Philogamus, Present state of matrimony: or the real causes of conjugal infidelity (London, J. Buckland, 1739), p. 32.

2. GEP November 12, 1751, letter from A Countryman; Conn January 30, 1755 #53: “There are many customs among the Great, which are also practiced by the lower sort of people.”

3. St. J May 19, 1761, “A Sketch of the ruling manners of the Age, from a Discourse on Luxury,” by Thomas Cole; Public Register or Freeman’s Journal March 7–9, 1771.

4. Margaret R. Hunt, The Middling Sort: Commerce, Gender and the Family in England 1680–1780 (Berkeley, University of California Press, 1996), p. 3; Paul Langford, A Polite and Commercial People: England, 1727–1783 (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1998), p. 61; Daniel Defoe, The Life and Strange Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, 3rd edition (London, printed for W. Taylor, 1719), p. 3; Diary or Woodfall’s Register October 4, 1790.

5. Amanda Goodrich, in Debating England’s Aristocracy in the 1790s (Rochester, N.Y., Boydell Press, 2005), pp. 15–22, discusses the usage of the term “aristocracy” in political discourse late in the eighteenth century while Paul Langford, in a section labeled simply ‘Aristocratic Vice’ (A Polite and Commercial People, pp. 582–87), sees this as an important feature of the 1770s. Using the same general, catch-all definition of this group, I am endeavouring to consider a longer, less specific historical period.

6. In her moral tale of 1799, The Two Wealthy Farmers (London, F. and C. Rivington), p. 18, Hannah More’s Farmer Worthy, describing the dangers of reading frivolous novels, says such novels make the “crying sins” of “ADULTERY, GAMING, DUELS and SELF-MURDER” seem commonplace, rather than crimes deserving hanging.

7. Thomas Erskine, Reflections on Gaming, Annuities and Usurious Contracts (London, T. Davies, 1786), p. 3.

8. Henry Fielding, Amelia, ed. Martin Battesin (Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1983), p. 375; Henry Fielding, The Covent Garden Journal [1752], edited by Bertrand Golgar (Middletown, Conn., Wesleyan University Press, 1988) #68, October 14, 1752, p. 359.

9. Anthony Holbrook, Christian Essays upon the Immorality of Uncleanness and Duelling (London, John Wyat, 1727); LC January 12, 1790.

10. PA May 17, 1765; Gaz August 11, 1783.

11. A Discourse Upon Self-Murder (London, J. Fox, 1754), p. 15; Times November 21, 1786.

12. See Patricia Howell Michaelson, “Women in the Reading Circle,” Eighteenth-Century Life 13 (1990), pp. 59–69.

13. T. C. W. Blanning, in The Culture of Power and the Power of Culture: Old Regime Europe 1660–1789 (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2002), p. 4, uses the most capacious definition of culture, which he says, was “classically defined by Sir Edwin Tylor as ‘that complex whole which includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, law, custom and any other capabilities and habits acquired by man as a member of society.’ ” This is too large an understanding for my purposes. For Geertz on the web of meaning, see The Interpretation of Cultures (New York, Basic Books, 1973), “Thick Description,” pp. 3–30. A discussion of habitus can be found in Pierre Bourdieu’s Distinction, trans. Richard Nice (London, Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1984), “The Habitus and the Space of Life,” pp. 9–225.

14. David Hume, “On the first Principles of Government” in Essays and Treatises on Several Subjects (London, A. Millar, 1758), p. 20.

15. GM January 1752, p. 30. It seems to me that, by omitting the word “public” from discussions of “opinion,” one is leaving open and undefined a term which was made, in large part, by appeals to it. By embracing such deliberate vagueness, we avoid problems of locating and specifying who was, or was not, a member of such a group, or who had such an opinion.

16. The OED Online gives 1374 as the date of the first use of “skirmish” in the singular.

17. These critics resemble the diverse groups of eighteenth-century newspaper readers, discussed by Bob Harris, Politics and the Rise of the Press (London, Routledge, 1996).

18. For debating societies see D. T. Andrew, London Debating Societies 1776–1799 (London, London Record Society, 1994) and Mary Thale, “London Debating Societies in the 1790s” in the Historical Journal (1989), “Women in London Debating Societies in 1780” in Gender and Society (1995), and “Deists, Papists and Methodists at London Debating Societies, 1749–1799” in History, 86:283 (2001).

19. One of the earliest and most powerful accounts of the centrality of the press to all sorts of political and cultural change, John Brewer’s Party Ideology and Popular Politics at the Accession of George III (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1976, pp. 139–62) led to a significant change of focus in our understanding of the technologies of social and political power in this period. John Cannon has noted that, in the eighteenth century, “The rise in the number and importance of the middling classes of society—clerks, merchants, teachers, doctors, attorneys, shopkeepers—manifested itself in a great increase in the publication of journals, books and newspapers” (Parliamentary Reform 1640–1832 [Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1972, 1994], p. 48). Kathleen Wilson points out that “printed artifacts” were “one of the first mass cultural commodities” (The Sense of the People: Politics, Culture and Imperialism, 1715–1785 [Cambridge University Press, 1998] p. 31). For more on letters to the editor or printer, see Robert L. Haig, The Gazetteer 1735–1797: a study in the eighteenth-century English newspaper (Carbondale, Southern Illinois Press, 1960), pp. 70–75.

20. Lucyle Werkmeister, The London Daily Press 1772–1792 (Lincoln, University of Nebraska Press, 1963), pp. 7, 90.

21. Only a few of the most recent or influential works are here cited: Duelling: V. J. Kiernan, The Duel in European History (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1988); James Kelly, “That Damn’d Thing Called Honour”(Cork, Cork University Press, 1995); Markku Peltonen, The Duel in Early Modern England: Civility, Politeness and Honour (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2003); Stephen Banks, “Very little law in the case: Contests of Honour and the Subversion of the English Criminal Courts, 1780–1845” (2008) 19(3) King’s Law Journal 575–94; “Dangerous Friends: The Second and the Later English Duel” (2009) 32 (1) Journal for Eighteenth Century Studies 87–106; “Killing with Courtesy: The English Duelist, 1785–1845” (2008) 47 Journal of British Studies 528–58; Robert B. Shoemaker, “The taming of the duel: masculinity, honour and ritual violence in London, 1660–1800” Historical Journal (2002) 45/3 pp. 525–45; idem, “Male Honour and the Decline of Public Violence in Eighteenth-Century London,” Social History (2001) vol. 26, pp. 190–208; Jeremy Horder, “The Duel and the English Law of Homicide,” Oxford Journal of Legal Studies 1992, 12(3), pp. 419–32. Adultery: Lawrence Stone, Road to Divorce (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1990), and Broken Lives (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1993); David Turner, Fashioning Adultery (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2002); Sarah Lloyd, “Amour in the Shrubbery,” Eighteenth Century Studies (2006) 39.4, 421–42; Gillian Russell, “The Theatre of Crim. Con.: Thomas Erskine, Adultery, and Radical Politics in the 1790s” in Unrespectable Radicals? Popular Politics in the Age of Reform, ed. Michael T. Davis and Paul A. Pickering (Farnham, UK, Ashgate, 2007), pp. 57–70; Randolph Trumbach, Sex and the Gender Revolution (Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1998); Karen Harvey, Reading Sex in the Eighteenth Century: Bodies and Gender in English Erotic Culture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004); Cindy McCreery, “Breaking all the Rules: The Worsley Affair in Late-Eighteenth-Century Britain,” in Orthodoxy and Heresy in Eighteenth-Century Society: Essays from the DeBartolo Conference, ed. Regina Hewitt and Pat Rogers (Lewisburg and London: Bucknell University Press, 2002) and “Keeping Up with the Bon Ton: the Tête-a-Tête Series in the Town and Country Magazine,” in H. Barker and E. Chalus, Gender in Eighteenth-Century England (London, Addison Wesley Longman, 1997); Marilyn Morris, “Marital Litigation and English Tabloid Journalism: Crim. Con. in The Bon Ton (1791–1796),” in the British Journal for Eighteenth Century Studies, 2005, vol. 28, pp. 33–54. Suicide: Michael MacDonald, “The Medicalization of Suicide in England: Laymen, Physicians, and Cultural Change, 1500–1870,” in Framing Disease: Studies in Cultural History, ed. Charles Rosenberg and Janet Golden (New Brunswick, N.J., Rutgers University Press, 1992), pp. 85–103; Michael MacDonald, “Suicide and the Rise of the Popular Press in England,” Representations 22 (1988) pp. 36–55; with Terence Murphy, Sleepless Souls (Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1990); Georges Minois, History of Suicide: Voluntary Death in Western Culture, transl. Lydia Cochrane (Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999); R. A. Houston, Suicide, lordship, and community in Britain, 1500–1830 (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2010). Gambling: Nicholas Tosney, “Gaming in England, c. 1540–1760” (unpublished PhD thesis, University of York, UK, 2008); Justine Crump, “The Study of Gaming in Eighteenth Century English Novels” (unpublished PhD thesis, University of Oxford, 1997), Janet Mullin, “We had Carding,” Journal of Social History, vol. 42, #4, (2009) pp. 989–1008.

22. In this I agree with William J. Bouwsma, who argues that, unlike social history in which “gross discontinuities” and rapid change seem possible analytic modes, they are “generally implausible in cultural history, in which change is very slow.” A Usable Past: Essays in European Cultural History (Berkeley, University of California Press, 1990) p. 5.

23. Ivor Asquith noted that “Most newspaper proprietors were aware that, if they were to maintain their papers as profitable, or even viable concerns, they had to cater for the tastes of the general reader who was not only interested in politics. Such a committed Foxite journalist as James Perry described miscellany, or non-political features, as “the soul of a newspaper …” Furthermore, “some contemporaries took the view that if a newspaper was of poor quality, it was as much the fault of the public as of the proprietors; it was felt that proprietors had little alternative but to respond to the public’s taste” (“The Structure, ownership and control of the press, 1780–1855,” in George Boyce, ed., Newspaper History from the 17th century to the present day (London, Constable, 1978) pp. 107, 114.

24. Commenting on the symbolic centrality of law to Britons in this period, John Brewer noted that “The essential difference between Britain and other nations was that her constitution was a government of laws …” in which, at least in theory, “All those who held power … were deemed subject to the law.” (Brewer, Party Ideology, p. 244).

25. E. P. Thompson, The Making of the English Working Class (Harmondsworth, Penguin Books, 1968), p. 8; William Allen (ed.), The Philanthropist, 1801, v, p. 187.

1. The first part of this chapter title is taken from the title of a study by Frank M. Turner, Contesting Cultural Authority (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1993) which examines the Victorian period; Julian Pitt-Rivers, International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, “Honor,” p. 510.

2. George Stanhope, A Paraphrase and Commentary upon the Epistles and Gospels, vol. 2, p. 94, quoted in the Oxford English Dictionary. See Leviathan [1651] (New York, Macmillan & Co, 1962), p. 51, for Thomas Hobbes’s earlier definition of aristocratic magnanimity as “a contempt for little helps and hindrances,” For more on this long history, see Anna Bryson, From Courtesy to Civility (Oxford, Clarendon, 1998).

3. See, for a similar usage, Amanda Goodrich, Debating England’s Aristocracy in the 1790s (London, Boydell Press, 2005), and Paul Langford, A Polite and Commercial People, p. 582.

4. Antoine Courtin, The Rules of Civility or the Maxims of Genteel Behaviour, with A Short Treatise on the Point of Honour (London, Robert Clavell and Jonathan Robinson, 1703), pp. 3–8, 225–72. This work had gone into its twelfth English edition by 1703. For more on Courtin’s earlier reception, see Bryson, From Courtesy to Civility, pp. 81–100, 131–40.

5. George Berkeley, The Works of George Berkeley, Bishop of Cloyne, ed. A. A. Luce and T. E. Jessop, 9 vols. (London, T. Nelson, 1948–1957), “Alciphron or The Minute Philosopher” [1732] 3: 112.

6. Edward, Lord Herbert of Cherbury, The Life of Edward, First Lord Herbert of Cherbury (London, Oxford University Press, 1976), p. 49; John Mackqueen, Two Essays: the first on courage, the other on honour (London, John Morphew, 1711), p. 2.

7. Herbert of Cherbury, Life, p. 43; LM March 1735, p. 145.

8. A Hint on Duelling, in a letter to a friend (London, M. Sheepey, 1752), p. 3; LM October 1732, p. 361.

9. John Mackqueen, An Essay on Courage p. 13; The Tatler, ed. Donald F. Bond (Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1987) 4: July 22–25, 1710, p. 79; see Bernard Mandeville, Fable of the Bees, ed. F. B. Kaye (Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1924, p. 58) for his discussion of the “Rapture we enjoy in other’s esteem [which] overpays us for the conquest of strongest passions.” For more on Mandeville’s thought and importance, see Thomas A. Horne, The Social Thought of Bernard Mandeville (New York, Columbia University Press, 1978), M. M. Goldsmith, Private Vices, Public Benefits: Bernard Mandeville’s Social and Political Thought (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1985), and J. Martin Stafford, ed., Private Vices, Publick Benefits? The Contemporary Reception of Bernard Mandeville (Solihull, Ismeron, 1997).

10. Robert Heath, “To one who was so impatient,” in Clarasella; together with Poems Occasional (London, Humph. Moseley, 1650), pp. 6–7; ‘self-preserving,’ OED, quoting Ezekiel Hopkins, bishop of Raphoe and Derry, “A Sermon” [on Peter ii 13, 14] preached at Christ’s Church, Dublin, 1669.

11. John Prince, Self-Murder Asserted to be a Very Heinous Crime (London, B. Bragge, 1709), p. 9. Susannah Centlivre in The Perjur’d Husband (London, Bennett Banbury, 1700, p. 15) noted that “if I should betray/You, I bring my self into jeopardy, and of all Pleasures/Self-Preservation/Is the dearest.” Anne Finch, most unusually, thought this the philosophy only of freethinkers; see Free-Thinkers, a poem (London, 1711).

12. Officer [Defoe, Daniel], An Apology for the Army (London, J. Carson, 1715), pp. 8–9.

13. [Bernard Mandeville], An Enquiry into the Origins of Honour and the Usefulness of Christianity in War [1732], 2nd. ed. with a new introduction by M. M. Goldsmith (London, Frank Cass, 1971), p. iv; Officer, Apology, p. 13.

14. Mandeville, Origins of Honour, p. 62; John Oldmixon, A Defence of Mr. Maccartney (London, A. Baldwin, 1712), p. 8.

15. Courtin, Civility, p. 251; Mackqueen, Essay on Courage, p. 1: “Among all the noble Qualities which adorn Mankind, there is none more Excellent in it self, more Illustrious in the Eyes of others, or more Beneficial to the World, than Courage or Valour.”

16. Mandeville, Origins of Honour, p. 60; see also Thomas Hobbes, English Works, ed. Sir William Molesworth, 9 vols. (London, Bohn, 1839–45) 2:160.

17. Daniel Defoe, The Review VII, March 6, 1711, p. 590; see also Mandeville, Origins of Honour, p. 45. For other articulations of this notion of courage as the centerpiece of male virtue, see Addison in The Spectator, edited with an introduction and notes by Donald F. Bond, 3 vols. (Oxford, Clarendon, 1965) #99, June 23, 1711, 1: 416, and The Man #14, April 2, 1755, p. 3.

18. Archibald Campbell, An Enquiry into the Original of Moral Virtue (Edinburgh, Gavin Hamilton, 1733), p. 179; Henry Baker, “The Universe, A Philosophical Poem, Intended to restrain the Pride of Man,” 2nd edition (London, J. Worrall, 1746), p. 6.

19. E. W., Poems Written on Several Occasions, to which are added three essays (London, J. Baker, 1711), p. 117, 120.

20. Courtin, Civility, p. 236–37; Hobbes, Leviathan, p. 200.

21. GM, January 1736, vol. 6, pp. 11–12.

22. Anthony Holbrook, Christian Essays upon the Immorality of Uncleanness and Duelling delivered in two Sermons preached at St. Paul’s (London, John Wyat, 1727, p. 36). In his sermons Holbrook contrasted his own sense of honor as “an honest Concern for the just Dignity of Human Nature” with that other sort, which was only self-regarding and self-serving. [Edward Ward] Adam and Eve Stript of their Furbelows: or the Fashionable Virtues and Vices of Both Sexes, Exposed (London, J. Woodward, 1714), pp. 201–5.

23. Francis Hutcheson, An Inquiry into the Original of Our Ideas of Beauty and Virtue (London, J. Darby, A. Bettesworth, 1726), p. 221; Thomas Hobbes, The Elements of Law [1650], ed. Ferdinand Tonnies (London, Simpkin, Marshall, 1889), pp. 34–35.

24. Mackqueen, Essay on Honour, p. 7. “True courage,” argued Mackqueen, “is not the Exercise of an imperious, insolent Power, and going on in domineering, hectoring Language …”

25. Captain Abraham Clerke, A Home-Thrust at Duelling intended as an answer to a late Pamphlet intitled A Hint on Duelling (London, S. Bladon, 1753), pp. 14–15; Thomas Comber, A Discourse upon Duels (London, R. Wilkin, B. Tooke, 1720) p. 17.

26. LM September 1732, “Of Courage,” p. 278. The essay was also reprinted in the GM, September 1732, p. 943. Few would have agreed with Mandeville that the flaws were as integral to the code as its virtues. In discussing the inevitability of duelling, for example, Mandeville argued that “to say, that those who are guilty of it go by false Rules, or mistake the Notions of Honour, is ridiculous; for either there is no Honour at all, or it teaches Men to resent Injuries and accept Challenges” (Mandeville, Origin of Honour, p. 219).

27. Timothy Hooker [John Hildrop], An Essay on Honour (London, R. Minors, 1741), p. 4, 15–16. GM September 1731, p. 375.

28. GM May 1737, p. 284; Mackqueen, Essay on Honour, p. 11.

29. Courtin, Civility, p. 230; A Timely Advice, or Treatise of Play and Gaming (London, Th. Harper, 1640), pref. Arguing paradoxically that honor and virtue were two entirely different things, Mandeville applauded the former’s efficacy while derogating the latter: “The Invention of Honour has been far more beneficial to the Civil Society than that of Virtue, and much better answer’d the End for which they were invented (Mandeville, Origin of Honour, pp. 42–43.)

30. Hooker, Essay on Honour, p. 15; Holbrook, Christian Essays, pp. 33–34.

31. Duke of Wharton as cited in the GM September 1731, p. 383. It seems unlikely that Wharton in fact made this observation. He was a founder of the Hellfire Club, and his entry in the Dictionary of National Biography characterized his life as one of “reckless behavior” and “profligacy.” Hooker also employs the comparison of a sick and healthy body: “But whatever Similitude there may seem to be betwixt Pride and Honour, Ambition and true Greatness of Mind, they are as far asunder as the Swelling of a Dropsy, from a full and robust Habit of Body.” Essay on Honour, p. 44; for restatements of this thought, see [Theophilus Lobb], Sacred Declarations or a Letter to the Inhabitants of London (London, J. Buckland, 1753) p. 5; [François Vincent Troussaint], Manners, translated from the French (London, J. Payne & J. Boquet, 1749), p. 2.

32. Mandeville, Origins of Honour, p. 15, 40. Comber, Discourse upon Duels, p. 6, and A Circumstantial and Authentic Account of a Late unhappy Affair (London, J. Burd, 1765), p. 8; both agreed that modern honor was a “gothic” or Germanic invention.

33. Mandeville, Origins of Honour, p. 14; Berkeley, Alciphron, 3:112.

34. An Essay on Modern Gallantry (London, M. Cooper, 1750), p. 4; A Timely Advice, p. 34. The author of this pamphlet, citing St. Augustine, described the gamester as an idolater. “The Gamester therefore may be said to worship the Dice or Cards for his gods, seeing he loveth them more than God.…”

35. Well-wisher, Honours Preservation Without Blood (London, 1680), p. 25.

36. Mandeville, Origins of Honour, p. 2; see Courtin, Civility, “A Duel attacks directly the Sovereign Authority and is therefore High Treason,” p. 272, and Hobbes, Leviathan, pp. 117, 120 for the notion that those who follow the dictates of honor deny the power of their sovereign.

37. GM May 1737, p. 284; Person of Quality, Marriage Promoted (London, Richard Baldwin, 1690), p. 46. Hooker, Essay on Honour, p. 21, also believed that for their own good and the nation’s, irreligious immoral men “ought to be laid under proper restraints.”

38. Jeremy Collier, “Upon Duelling” in Essays upon several Moral Subjects [1692] (London, R. Sare, H. Hindmarsh, 1698), p. 124; Comber, Discourse Upon Duels, p. 37.

39. Thus, in Mandeville’s dialogue The Origins of Honour, when the interlocutor, Horatio, asks his companion, Cleo, how many of the gentlemen of his acquaintance would refuse a duel from Christian principles, and Cleo replies, “A great many, I hope,” Horatio retorts: “You can hardly forbear laughing, I see, when you say it” (pp. 79–80).

40. Timely Advice, pref.; Well-Wisher, Honours Preservation, p. 18.

41. GM May 1737, p 286; John Brown, On the Pursuit of False Pleasures and the Mischiefs of Immoderate Gaming (Bath, James Leake, 1750), p. 12.

42. Joseph Trapp, Royal Sin, or Adultery Rebuk’d in a Great King, a sermon delivered at St. Martin’s (London, J. Higgonson, 1738), p. 14.

43. Erasmus Mumford, A Letter to the Club at Whites (London, W. Owen, 1750), p. 7.

44. Alexander Jephson, The henious sins of ADULTERY and FORNICATION, p. 17.

45. Brown, On the Pursuit of False Pleasures, p. 14.

46. An Address to the Great (London, R. Baldwin, 1756), p. 9; Mandeville, Origins of Honour, p. 177; Thus the Man, a short-lived essay-periodical of the mid 1750s, argued that “It is of the highest consequence rightly to instruct the people in the nature of virtue, and fit them for society. The best and shortest way of instructing them is by the example of their superiors; whom they as naturally follow, as soldiers follow their leader, when they have a high opinion of his honesty and abilities” (May 7, 1755, p. 5).

47. Reflexions on Gaming (London, J. Barnes, 1750), p. 44; William Webster, A Casuistical Essay on Anger and Forgiveness (London, W. Owen, 1750), p. 75.

48. GM 1731, p. 428; Hooker, Essay on Honour, p. 14; see also LM July 1732, “Praise of Cowardice,” pp. 175–76.

49. LM July 1732, pp. 186–87, September 1735, pp. 491–92.

50. Hooker, Essay on Honour, p. 18; Webster, Casuistical Essay, pp. 14–15.

51. The Man January 15, 1755, p. 2; GM February 1756, “The Advantages of Ancestry demonstrated,” pp. 81–2.

52. Berkeley, Alciphron, 2nd Dialogue, 3:69; the Man November 19, 1755, p. 5.

53. Mackqueen, Essay on Courage, p. 9; Modest Defense of Gaming (London, R. & J. Dodsley, 1754), p. 23.

54. Toussaint, Manners, p. 1; GM May 1737, “The Character of a Man of Honour in the BEAU MONDE,” pp. 284–85.

55. John Cockburn, A Discourse of Self Murder (London, 1716), p. 6; Self-Murther and Duelling the Effects of Cowardice and Atheism (London, R. Wilkin, 1728), p. 43. Not only were the two vices combined and discussed as one in the later work, but Cockburn himself produced A History and Examination of Duels just four years after his essay on suicide (London, G. Strahan, 1720).

56. Timely Advice, pp. 59, 62; the Devil March 1, 1755, p. 40.

57. Comber made the connection between duelling and suicide clear: “ ’Tis true, in this case the Dueller falls by another’s hand; but he ought to be accounted a Self-murtherer for all that; because he voluntarily and deliberately exposed himself to that Sword by which he fell.” Discourse upon Duels, p. 13.

58. The Man, February 9, 1755, p. 3; The Whole Art and Mystery of Modern Gaming (London, J. Roberts, 1726), p. iv. The LM of 1735 concluded that “At present, Honour is a Man, a Cheat in Gaming, false to his Friend, a Betrayer of the Liberties of his Country, is maintain’d by—a lucrative Office” (p. 426. Note that the first vice mentioned, the root perhaps of all the rest, is gaming.

59. The Connoisseur (London, R. Baldwin, 1755–56), 2 vols., #50, January 9, 1755, 1:296; Jephson, The heinous sins, pp. 8–9; Oldmixon, Defense, p. 3.

60. Steele, Spectator, #75, May 26, 1711, pp. 323–25. Another definition of a gentleman can be found in the Guardian (2 vols., 1756) I, 20 April 1713, 146, “by a fine gentleman I mean a man completely qualified as well for the service and good as for the ornament and delight of society.”

61. John Wesley, The Works of the Rev. John Wesley, 10 vols. (Philadelphia, D& S Neall, 1826–7), The Journal, November 1738, 3: 113.

62. Spectator #99, June 23, 1711, p. 416; the Man #14, April 2, 1755, p. 3.

63. Mandeville, Origins of Honour, p. 54; Keith Thomas, “The Double Standard,” Journal of the History of Ideas 20 (2) (1959), pp. 195–216.

64. Hooker, Essay on Honour, p. 2; Essay on Modern Gallantry, p. 50.

65. Mandeville, Origins of Honour, pref. iii; see also Well-Wisher, Honour’s Preservation, p. 4.

66. Chishull, Against Duelling, p. 5; Holbrook, Christian Essays, p. 38.

67. Clerke, Home Thrust at Duelling, p. 20. Anthony Fletcher points out that the earliest citation for the word ‘masculinity’ was in 1748. He notes that “It is not so much that masculinity was entirely different from manhood or manly behaviour, rather perhaps that the word attempted to express a more rounded concept of the complete man.” Gender, Sex, and Subordination in England, 1500–1800 (New Haven, Yale University Press, 1995), pp. 322–23; The Gentleman instructed in the Conduct of a Virtuous and Happy Life, 2 vols. (London, R. Ware, 1755), 1:24; the Man, March 12, 1755, #11, p. 3.

68. Mandeville, Origins of Honour, p. 210; Prince, Self-Murder Asserted, pp. 25–26.

69. Chishull, Against Duelling, p. 12; GM December 1731, p. 523.

70. Joshua Kyte, Sermon, “True Religion the only Foundation of true Courage” (London, B. Barker, 1758), pp. 5, 14. Kyte concluded that while many thought “Irreligion and Infidelity, drunkenness and Profaness, with all the appendages of riot and profligacy” necessary to the fighting man, he believed them to have no part of “the polite ingredients for the Military Character.”

71. John Locke, quoted in Philip Carter, Men and the Emergence of Polite Society 1660–1800 (Harlow, England, Longman, 2001), p. 55; Jonathan Swift, quoted ibid., pp. 68–69.

72. Fletcher notes “the gradual substitution from around the 1730s, of the world ‘politeness’ for the word ‘breeding.’ The new term indicates a much stronger focus than previously on external manners alone” (p. 336). See also Lawrence Klein, Shaftesbury and the Culture of Politeness (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1994) for an in-depth articulation of the tenets of politeness. Carter, Men and the Emergence, has an interesting discussion on women’s refining role, pp. 68–70.

73. Essay on Gallantry, p. 45. See also Thoughts on Gallantry, Love and Marriage (London, R. and J. Dodsley, 1754), p. 18.

74. Addison, Spectator, June 23, 1711, in The Papers of Joseph Addison, 4 vols. (Edinburgh, William Creech, 1790) 2:90; Berkeley, Alciphron, 3:70. In this dialogue, Berkeley tells the story of Lady Telesilla, who “made no figure in the world” until her husband introduced her to the ways of the beau monde. Thereupon she became a gambler, an extravagant spender, and in exchange for his instruction, gave her husband “an heir to his estate, [he] having never had a child before.”

75. CGJ #66, October 28, 1752, pp. 350–51; Jephson, The heinous sins, p. 7.

76. For the culture of politeness see Lawrence E. Klein, Shaftesbury and the Culture of Politeness; “Politeness and the Interpretation of the British Eighteenth Century,” The Historical Journal, Volume 45, Number 4 (2002), pp. 869–98; “The Polite Town: Shifting Possibilities of Urbanness, 1660–1715,” in Tim Hitchcock and Heather Shore, eds., The Streets of London (London, Rivers Oram Press, 2003); and Philip Carter, Men and the Emergence.

77. The first part of this heading is quoted from the Edinburgh Review by Alexander Andrews, The History of British Journalism (London, Richard Bentley, 1859), p. 7; the second part is the title of a letter from “Theseus” to the editor of the MC (August 23, 1786), bemoaning the inclusion of great gobs of morality among the news.

78. George Crabbe, The Poetical Works of the Rev. George Crabbe (London, John Murray, 1838), vol. 2, p. 128. There were those who agreed with him, some, like “Carus” who wrote to the Daily Courant (November 14, 1732), arguing that newspapers were not the appropriate fora to discuss matters of high politics.

79. Edward Bearcroft, representing the plaintiff in the Howard v Bingham divorce cause, cited in the Times, March 6, 1794.

80. Andrews, History of British Journalism, pp. 99, 101.

81. Carter, Men and the Emergence, p. 25.

82. In terms of dates at which periodicals began, the 1730s saw the birth of 2 dailies, 1 tri-weekly, 4 weeklies, and 2 monthlies; between 1750 and 1770, 6 dailies, 2 tri-weeklies, and 7 monthlies were published. The seven monthlies mentioned were the Gentleman’s Magazine (begun 1731), the London Magazine (1732), Samuel Johnson’s Rambler (1750), the Universal Magazine, the Annual Register, the Oxford Magazine and the Town and Country Magazine.

83. For this book I have consulted more than 150 newspapers and magazines from the 1680s through the 1840s; about half of these cover the period 1760–1800. Robert Louis Haig, The Gazetteer, 1735–1797 (Carbondale, Southern Illinois University Press, 1960), p. 4. See also John Brewer, Party Ideology.

84. Haig, Gazetteer, p. 70, 71.

85. Bob Clarke, From Grub Street to Fleet Street (Aldershot, Ashgate Publishing, 2004), p. 86.

86. For recent histories of the roles of the coffeehouse see Markman Ellis, The Coffee House: A Cultural History (London, Weidenfeld & Nicholson, 2004), and Brian Cowan, The Social Life of Coffee (New Haven, Yale University Press, 2005). Ayton Ellis, in The Penny Universities: A History of the Coffee-Houses (London, Secker & Warburg, 1956) especially stresses their role as centers of discussion.

87. Haig, Gazetteer, p. 59.

88. Connoisseur #45, December 5, 1754, p. 268.

89. Victoria Glendinning, Trollope (London, Hutchinson, 1992), p. 399.

1. A Full and Exact Relation of the Duel fought in Hyde park on Saturday November 15, 1712, between His Grace James, Duke of Hamilton, and the R.H. Charles Lord Mohun, in a letter to a member of Parliament (London, E. Curll, 1713), p. 15.

2. Victor Stater, High Life, Low Morals: The Duel that Shook Stuart Society (London, John Murray, 1999).

3. The quotation that serves as title to this chapter comes from Chishull, Against Duelling, p. 5.

4. Anthony Holbrook, “The Obliquity of the Sin of Duelling,” in Christian Essays upon the Immorality of Uncleanness and Duelling delivered in two Sermons preached at St. Paul’s (London, John Wyat, 1727), pp. 33–34.

5. See for example a letter against duelling in the LEP April 25, 1765, in which its author discussed “the most effectual way to suppress this devilish custom”; ten years later the author of Duelling, a poem (London, T. Davies, 1775) argued that Satan was the father of both murder and duelling. Even in the late 1820s, following the Wellington/Winchilsea duel which will be discussed in chapter 6, the Age commented that the Duke should not have fought, no matter what the charges against him, but “seduced by Satan, he fell into a fleshly snare, and called for pistols …” [March 29, 1829].

6. Henry Fielding, Amelia [1754], ed. Martin C. Battesin (Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1983), p. 503.

7. For the growth of politeness and civility, see Markku Peltonen, “Politeness and Whiggism, 1688–1732,” Historical Journal (2005) 2:391–414; John Brewer, “The Most Polite Age and the Most Vicious,” in The Consumption of Culture 1600–1800, ed. Ann Bermingham and John Brewer (London, Routledge, 1995), pp. 341–61.

8. The Spectator #84, June 6, 1711, p. 359; four numbers of the Spectator mentioned duelling in its first year alone: #1, March 1, 1711; #2, March 2, 1711; #84, June 6, 1711; #99, June 23, 1711.

9. White, April 19, 1750; The Duellist, or a cursory view of the rise, progress and practice of Duelling (London, 1822), quoting Spectator #97, June 21, 1711; Carter, Men and the Emergence of Polite Society, p. 25.

10. Henry Fielding, The History of Tom Jones, a foundling, 6 vols. (London, A. Millar, 1749), 3:116–17.

11. See Susannah Centlivre, The Beau’s Duel (London, D. Brown & N. Cox, 1702), p. 29; William Popple, The Double Deceit (London, T. Woodward & J. Wallace, 1736), and for yet another play, see John Kelly, The Married Philosopher (London, T. Worral, 1732), p. 70.

12. Samuel Richardson, The History of Sir Charles Grandison (London, S. Richardson, 1753–54); Richardson, Clarissa or the History of a Young Lady, 8 vols. (London, S. Richardson, 1751), 7: Letters LII–LIV; Eliza Haywood, The History of Miss Betsy Thoughtless [1751], ed. Christine Blouch (Broadview Literary Texts, Peterborough, Ont., 1998) and The History of Jemmy and Jenny Jessamy (London, T. Gardner, 1753); for Fielding, Tom Jones.

13. Tatler, #39, July 9, 1709, pp. 281–87.

14. For the Mohun-Hamilton duel, see The Examiner, November 13, 1712, Stater, High Life, Low Morals, and H. T. Dickinson, “The Mohun-Hamilton duel: Personal feud or Whig plot?” Durham University Journal (1965), pp. 159–65; for the Deering-Thornhill duel, see An Account of the Life and Character of Sir Cholmley Deering, Bart (London, J. Read, 1711), [Richard Steele] The Spectator #84, June 6, 1711, and Richard Thornhill, The Life and Noble Character of Richard Thornhill (London, 1711); for the Clarke-Innes duel, GM March 1750, p. 137, Old England May 12, 1750, White April 19, 1750; for Dalton-Paul, GM 1751, p. 234; and for the Byron-Chaworth duel, see AR 1765, pp. 208–12, GM 1765, pp. 196–97, 227–29. Only in the Pultney-Harvey duel do we read of the presence of seconds.

15. For the Andrews-Lee duel, see the Universal Spectator August 9, 1735; the duel between the Irish friends, ibid., January 22, 1737; the philosophical duel, which occurred in June 1721, was recounted as part of a letter to the Universal Spectator December 25, 1742.

16. For the Grey-Lempster duel see GM April 1752, p. 90.

17. See, for example, the Protestant [Domestick] Intelligence March 2, 1680; the Daily Post April 6, 1723; and the Evening Post September 29, 1724.

18. Woman of Honour (London, T. Lowndes and W. Nicholl, 1768), ii:131. See also The Tatler # 26, June 9, 1709, pp. 202–3: “I expect Hush-Money to be regularly sent for every Folly or Vice any one commits in this Town; and hope, I may pretend to deserve it better than a Chamber-Maid, or Valet de Chambre: They only whisper it to the little Set of their Companions: but I can tell it to all Men living, or who are to live.”

19. The Yale Edition of Horace Walpole’s Correspondence, ed. W. S. Lewis, 48 vols. (New Haven, Yale University Press, 1937–1983), To Mann, 14th May 1765, 22:293.

20. See The Trial of Captain Edward Clarke for the Murder of Captain Thomas Innes in a duel in Hyde park, March 12, 1749 (London, M. Cooper, 1750). For more on this, see Nicholas Rogers, Mayhem: Post-War Crime and Violence in Britain, 1748–1753 (New Haven, Yale University Press, 2012). My thanks to Dr. Rogers for clarifying this for me.

21. Old England #320, May 12, 1750; see also White April 19, 1750 and GM May 1750, pp. 219–20.

22. See for another instance of these sentiments, a poem written after this duel, False Honour, or the Folly of Duelling (London, A. Type, 1750), p. 9. For a fine analysis of the difficulties faced by Army officers, see Arthur N. Gilbert, “Law and Honour among Eighteenth-Century British Army Officers,” Historical Journal 19 (1976), 75–87.

23. See, for example GM November 17, 1762, p. 550, and May 23, 1763, p. 256. For Wilkes’s own first duel with the Scots Lord Talbot, see John Sainsbury, “ ‘Cool Courage Should Always Mark Me’: John Wilkes and Duelling,” Journal of the Canadian Historical Association, 1997, pp. 19–33.

24. LEP April 25, 1765. The letter appeared on the paper’s front page.

25. For these, see “S.Y.’s” letter in the Gaz March 4, 1765; the letter from “Bob Short” in the LEP April 13 and “Candidus’s” reply ibid., April 18, 1765.

26. LEP April 25, 1765.

27. “WA,” PA May 27, 1765; ibid., July 20, 1765, signed “Philanthropos”; ibid., August 2, 1765.

28. GM, vol. 35, May 1765, p. 229; AR 1765, Appendix to the Chronicle, p. 211.

29. Tatler #93, November 12, 1709, p. 83.

30. These phrases taken from a letter, “Thoughts on the unwritten Laws of Honour,” published in the GM May 1769, pp. 240–41.

31. For Wilkes, see PA November 18, 1763, “An Epigram”; for Pitt, MC May 31, 1798.

32. Fog’s Weekly Journal, January 30, 1731 did report the duel, naming names and giving details. See also M. Dorothy George, Catalogue of Political and Personal Satires (London, 1978), #2580, “A Parliamentary Debate in Pipes’s Ground,” p. 460.

33. GM October 1762; PA October 7, 1762; LEP October 5, 1762.

34. In my survey of the Burney collection of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century newspapers, I have found 7 duels in the eighty years between 1680 and 1759 attributed to political differences; in the decade 1760–1769, 16 duels attributed to such differences.

35. LEP November 15, 1763; PA November 18, 1763.

36. Letter signed “Timidus” in LEP November 19, 1763; see also ibid., November 24, 1763. This last letter, as well as that signed “Democritus” ibid., November 29, 1763, and one ibid., December 3, 1763, mentions Martin’s failure to return Wilkes’s letter as well as his target practice. The letter that appeared in the PA on November 30, 1763, and the LEP November 27, 1763, sounds as though it came from Wilkes himself.

37. The conversation between the wit and his friend is recounted in the Gaz December 24, 1770; The Lady’s Magazine December 1770, p. 236 for their account of the duel. The Gaz (December 22, 1770) also reported that after the duel, Johnstone commented to Germaine that “I must declare that I now look upon the reflections (of cowardice) thrown out against your Lordship to be unjust, although at the time I spoke, I thought them well founded, and supported by the general opinion of mankind.” Walpole’s Correspondence, 18 December 1770, 23:256. Germaine’s name at the time of Minden was Sackville; he changed it to Germaine upon inheriting the estate of Lady Betty Germaine.

38. Gaz December 26, 1770, see also Bingley’s December 29, 1770.

39. The Fox-Adam duel was reported in the MC November 30, December 2, 3, 1779; the LC November 27, December 2, 1779; the Gaz November 30, December 1, 2, 1779; Lloyd December 1, 1779 and the PA December 2, 1779; the GM November 1779, p. 610 and the AR 1779, pp. 235–35; the poem to Fox appeared in the Gaz December 7, 1779. The Shelburne-Fullerton duel received coverage in the MC March 23, 24, 25, 27, 1780; the Gaz March 22, 23, 24, 1780; the LC March 23, 1780 and the GM March 1780, p. 151, 152.

40. Two pro-Fox letters, one signed “TW” and the other “WX,” appeared in the MC December 7, and December 13, 1779. A third signed “JB,” violently anti-Foxite, also appeared in the MC on December 15, 1779; I have italicized the words in the quote from this letter. “Right”’s letter also in that paper on January 5, 1780.

41. The three letters on the Shelburne-Fullerton affair: the first, signed “Heath Cropper,” appeared in the Gaz March 29, 1780; the second, in the LC, March 24, 1780; and the third, signed “A little further” also in the Gaz April 1, 1780. For the comment on the impropriety of duels for parliamentarians, see the T& C letter to the Observer, signed “Anti-Duellist,” October 1784, p. 532.

42. For the debates on duelling in the 1770s, see MC October 4, 30, 1773, *August 25, 1777, October 27, 1777, December 29, 1777, July 20, *27, 1778; Gaz October 17, *24, 1777, December 22, 1778. The four debates for which we have votes are indicated with *s.

43. The four debates on duelling after the Shelburne/Fullerton encounter can be found in the LC March* 24, April *3,*10, 1780 and the Gaz April 1, 1780. The debates which specifically refer to this duel are indicated with *s.

44. AR vol. 23, 1780, pp. 150–52.

45. Ibid., p. 151.

46. William Wilberforce, A Practical View of the Prevailing Religious System of Professed Christians (London, T. Cadell jr. and W. Davies, 1797), p. 224.

47. Times March 2, 1792. These comments were made after a member was challenged for his Parliamentary remarks by a republican Irishman.

48. The Observer June 3, 1798; for other expressions of this, see the Evening Mail May 25, 1798, the St. J May 26, 1798.

49. See, for example, the MH May 29, 31, 1798; the MC May 30, 1798.

50. The LP May 28, 1798; the MC May 30, 1798; the MH June 2, 1798.

51. The only newspaper I have found that made these sorts of negative comments was the Weekly Register (May 30, 1798) “We have repeatedly lamented that a practice so lamentable to civilization, and so criminal in the eyes of God, should be permitted in this country; but that it should receive the sanction of persons so high in office as Mr. Pitt, and that the Sabbath should be appropriate to this horrid practice, can never be sufficiently regretted.”

52. For Hodgson’s remarks, see the MC June 1, 1798; “The Ballad of Putney-Heath” in the MH June 4, 1798 and the LP June 1, 1798; the MH May 31, 1798. The St. J of May 29, 1798 argued that there was “no cure for this sort” of offence “but by fire and sword.”

53. The Sun May 29, 1798, MC May 31, 1798.

54. The Evening Post June 4, 1798 and the GEP June 5, 1798; the MC June 4, 1798.

55. Thomas Perceval, Moral and Literary Dissertations (Warrington, W. Eyres, 1789), “True and False Honour,” p. 28.

56. Of the 311 duels I have notice of for the 1780s, more than half (169) involved at least one member of the armed forces and in a little less than a quarter (76) of the cases, both duellists were military or naval men. Of course, this is very impressionistic, since press descriptions of all duellists are vague and often inaccurate.

57. “XY” in LEP September 28/October 1, 1781.

58. The LP April 21, 1783; the MH April 26, 1783. See the press commendation of such action following the Macartney-Stuart duel in the Times June 13, 1786.

59. For similar cases, see MH February 2, 1785; Times December 21, 1787; ibid., August 4, 1788; ibid., September 21, 1791; GM supplement 1805, pp. 1223–24.

60. MH April 26, 1783; GM 1783, p. 302.

61. The GM 1783, p. 443; the GEP May 1, 1783; the LP May 2, 1783; the MC May 2, 1783.

62. The MC April 26, 1783; the GM 1783, p. 485.

63. The LP April 25, 1783; the story about Adolphus appeared in both the GEP May 1, 1783 and the LP May 5, 1783.

64. The LP May 7, 1783.

65. This column, called “Clotted Cream” and signed “Lac Mihi” was an ongoing series. For the one inspired by the Riddell/Cunningham duel see the MC April 26, 1783. The essay in the LP of May 14, 1783 appeared under the heading “The Companion”; Number CXXVII and was called “Duelling.” This last quote appeared in the Gaz May 6, 1783.

66. See Andrew, London Debating Societies 1776–99, #909, p. 155. Eleven debates on duelling took place in London during the 1770s and sixteen occurred there in the 1780s.

67. This duel was reported in the MH, the MP, the MC September 5, 1783 and the GM September 1783, p. 801; the coroner’s inquest following it in the MC September 9, 1783. The exculpatory note is in the MP September 11, 1783. For another bloody duel, the second that the two combatants had engaged in, fought about the American campaign, see the St. J August 3, 1784; the White August 3, 1784, the MC August 3, 1784, the PA August 3, 1784, and FFBJ August 6, 1784; the LC August 7, 1784 and the Gaz August 6, 1784 with the GM reporting the meeting in its August 1784 issue, p. 634.

68. Thus in the April 27, 1765 issue of the LEP, that paper reported that “It is said that duelling will be made a capital offence, without distinction of persons, with regard to the aggressor.” Pharamond’s edict proposed in the MC September 16, 1783 and in the MP September 17, 1763; for legislative changes, see the MH September 12, 1783 and for the Bishop of London’s bill, ibid., September 15, 1783. A month latter, the MH reported that ‘We are well assured that the practice of duelling has become an object of Royal consideration, and that the Secretary of State will have orders to deliver a message to Parliament respecting it’ (October 24, 1783). Needless to say, there is no evidence for this in the public record.

69. The five letters on this duel appeared in the MC September 8, 1783 signed “Humanitas,” September 9, 1783 signed “A Constant Reader,” September 13, and 24, 1783 signed “Scrutator” (the quoted sections are from the second Scrutator letter) and the MP September 10, 1783.

70. The AR October 17, 1783, p. 219; see also Gaz October 21, 29, 1783.

71. An example of the acceptance of duelling as the best of a set of bad alternatives can be seen in the comment of the Times of February 8, 1785, if duelling were to be strongly punished by the law, “something little short of Italian assassination may succeed to the generosity and manliness of the English duel.”

72. The first phrase, “established etiquette,” was used by Lieutenant Samuel Stanton, author of The Principles of Duelling with Rules to be Observed in every particular respecting it (London, T. Hookham, 1790), pp. 6–7, to describe the necessity that the gentleman are under for giving and accepting challenges to fight, while the second, used by Rev. Peter Chalmers in Two Discourses on the sin, danger and remedy of duelling (Edinburgh, Thomsons, Brothers, 1822), p. 165, argued that with a such a change men would no longer engage in such rencounters.

73. Jonathan Swift, quoted in the AR 1762, p. 166; A Hint on Duelling, p. 5.

74. The duel near Kensington was reported in Lloyd (June 19, 1775), the Mdsx and St.J (June 20, 1775), the MP (June 21, 1775), and the CM (June 24, 1775); the duel at Hyde Park reported in Lloyd (September 30, 1795), the Courier and Evening Gazette (October 2, 1795), and the Telegraph (October 5, 1795).

75. The MP January 11, 1775; the Times July 29, 1786.

76. The Times November 11, 1786; MP November 3, 1786.

77. For others wishing only satirical or ridiculous duelling items to appear, see both the LP June 7, 1782 and the PA November 9, 1786. For the mock duel between Jerry Puff, hairdresser, and Jack Grimface, chimneysweep, the Times November 4, 1786. Two years later, a similar mock duel appeared in the Times (January 18, 1788), recounting the battle between “Monsieur Stew-frog, head cook to Lord Bayham … [and] Roast Beef, head cook to Lord Howe.” An impression of the increased coverage can be seen in the rising number of duels and related items in the press; in the 1760s I have found 677 accounts in 20 magazines and papers, and in the 1770s, 1758 accounts in 33 similar works.

78. The Times, June 25, 1789.

79. Thoughts on Duelling (Cambridge, J. Archdeacon, 1773), pp. 3–5; the MP October 23, 1777; William Jackson, 30 Letters on various subjects, 2 vols. (London, T. Cadell, 1784) 1:12–13; Gaz December 22, 1784.

80. The original account of Johnston’s trial can be found in the Times, April 29, 1788, and the two items arguing for the incapacity of legal means to address slurs to gentlemanly honor, in the Times, May 1 and May 2, 1788.

81. T&C January 1779, letter to “the Man of Pleasure,” pp. 27–29; A Short Treatise upon the Propriety and Necessity of Duelling (Bath, 1779), pp. 21–22.

82. The AR 1780, pp. 150–52, gives an account of debate in the House of Commons, in which “a gentleman in high office” commented that duelling “would teach gentlemen to confine themselves within proper limits”; the Gaz November 5, 1783, who argued that duelling “prevails most in those polite nations where the sense of honour is most refined”; the MH November 1, 1783, “The spirit of duelling is a purifier, and may rid the world of many plagues”; two letters to the Times February 7, and February 21, 1785; a letter to the GM June 1788, p. 485.

83. Stanton, The Principles of Duelling, pp. 29, 35, 4. See also Stephen Payne Adye, A Treatise on Courts Martial (London, J. Murray, 1778), p. 32.

84. William Eden, Principles of Penal Law (London, B. White, 1771), pp. 223–26; Old Officer, Cautions and Advices to Officers of the Army (Edinburgh, Aeneas Mackay, 1777), pp. 149–50; “Scrutator” in the MC September 13, 1783; the Gaz October 31, 1783.

85. “Tiresias,” letter to the Times, August 18, 1789; Thomas Jones, A Sermon upon Dueling (Cambridge, J. Archdeacon, 1792.), p. 5; the Times September 4, 1786. For the connection between duelling and barbarity see also the MC September 5, 1780, the Times September 1, 1787 and August 18, 1789; for duelling and politeness, comments in the MP September 30, 1784, An Essay on Duelling, written with a view to discountenance this barbarous and disgraceful practice (London, J. Debrett, 1792), pp. 29–30, and Edward Barry, Theological, Philosophical and Moral Essays, 2nd ed. (London, J. Connor [1797?]), p. 94. “Tiresias,” letter to the Times, August 18, 1789; Jones, A Sermon upon Dueling, p. 5; Times, September 4, 1786.

86. The LP May 2, 1783; Thoughts on Duelling, p. 7.

87. For a later example of the notion that potential duellists should become brave soldiers, see “Tiresias,” Times, August 18, 1789, who noted that such acts would allow intrepidity to “receive the praises of their bravery without a blush.” For the role of such bravery directed against pre-revolutionary France, see Jonas Hanway, Virtue in Humble Life, 2 vols. (London, J. Dodsley, 1774), 1:218; Elizabeth Bonhote, The Parental Monitor, 4 vols. (London, Wm. Lane, 1796), 4:213.

88. Times October 29, 1785 and April 3, 1786, MH November 2, 1786; Times September 4, 1786.

89. M. J. Sedaine, The Duel, trans. William O’Brien (London, T. Davies, 1772), p. 6. See also the Prologue to William Kenrick, The Duellist (London, T. Evans, 1773), “Nay, arrant cowards, forc’d into a fray,/Now fight, because they fear to run away.” William Cowper noted of duelling “That men engage in it compelled by force,/And fear not courage is its proper source” (“Conversation” in Poems (London, J. Johnson, 1782), pp. 220–22.

90. Duelling, a poem (London, T. Davies, 1775), p. 18; Samuel Hayes, Duelling, a poem (Cambridge, J. Archdeacon, 1775), p. 9. Hayes called the father of duelling Moloch, not Satan, but I take these just to be different names for the same malignant spirit; Gentleman of that City, Modern Honour or the Barber Duellist, A comic opera in two acts (London, J. Williams, 1775), p. 27, see also H. H. Brackenridge, “Answer to a Challenge,” in Gazette Publications (Carlisle, Printed by Alexander & Phillips, 1806), p. 20, “Besides; the thing is now degraded/The lowest classes have invaded/The duel province.”

91. Miles Peter Andrews, The Reparation (London, Printed for T. and W. Lowndes [etc.], 1784), pp. 70–72; John Burgoyne, The Heiress (Dublin, John Exshaw, 1786), pp. 67–70.

92. Times March 13, 1792. This is a reference to the action of the Earl of Coventry in complaining of a young challenger to the House of Lords.

93. For the Coventry-Cooksey contretemps and laudatory comments, Times March 13, 1792; for more on the issue, see the Times March 17 and 27, 1792. The AR of February 1769, p. 72, carried the only account I have been able to find of the Meredith challenge; for a letter hostile to Coventry see “A Clergyman,” the Gaz May 6, 1769 and Haig, Gazetteer, p. 76; for a positive, laudatory letter see “A Freeman of Liverpool” in the Mdsx May 9, 1769.

94. Antony E. Simpson has argued that “few misdemeanor arrests or prosecutions occurred in this period” though he mentions in passing, that four potential duellists were charged £600, “a huge amount,” to keep the peace. We have seen that legal recourse, whether through magistrates’ arrests or cases at King’s Bench, grew at the end of the eighteenth century, and that much larger sums than £600 were required as bail. For our story, however, one element that is importantly neglected by Simpson in his fine study is the role of the press in publicizing such options (“Dandelions on the Field of Honour: Dueling, the Middle Classes, and the Law in Nineteenth-Century England,” in Criminal Justice History, 1988, pp. 99–155).

95. From 1730 through 1759 I have found 6 reports of men taking challengers to court; see the British Journal November 14, 1730, the Echo February 10, 1730, the British Journal, or the Traveller February 20, 1731, the DA October 12, 1743, the LEP April 26, 1744 and Old England May 25, 1751. The case of a man challenged going to the magistrates was reported in the MP on November 17, 1778. For a typical case of a duel stopped by the magistrates because “notice had been given” see the LC March 3, 1764. For another discussion of these challenges see Stephen Banks, A Polite Exchange of Bullets (Woodbridge, Boydell & Brewer, 2010), pp. 154–66.

96. See, for example, the Shaw/Delaval case, reported in the Times February 11, 1799; the Cavendish/Bembric case, ibid., February 1, 1800; the Payne/Beevor case, ibid., February 3, 1800, and the Stodthard/Prentice case, ibid., January 26, 1802.

97. Seventeen of the 103 reported King’s Bench cases received at least two notices; a very small number, however, were more fully covered—three, four, six, and even seven accounts (the last in the case of the notorious Lord Camelford) occasionally occurred.

98. The earliest of these complaints to the magistrates can be found in the World, March 17, 1786; the Times July 22, 1786 and March 19, 1787.

99. It was reported that the Duke of Norfolk and Sir John Honeywood were on the brink of a duel, until reconciled by their friends (Times April 4, 1791); that the impending duel between the Earl of Belfast and Lord Henry Fitzgerald was stopped by the intervention of the Earl’s uncle (Times April 14, 1791). For the Scottish courts, see Times March 24, 1790 and July 15, 1805; and for the apology of a drunk officer to John Rolle, MP and Colonel of a militia unit, which terminated the conflict, see the Times September 10, 1791.

100. The initial notice, under the Law Reports, King’s Bench heading, appeared in the Times, February 1, 1800; “Anti-Duellist’s” letter was published on February 12, 1800. Interestingly enough, though Cavendish refused to fight Bembric, he was a second (to Earl Fitzwilliam) in an interrupted duel five years earlier; see Times June 30, 1795.

101. See, for example, the court case brought by the Solicitor General, Sir John Scott, against Robert Mackreth, MP, for issuing a challenge, Times February 26, 1793, or Christopher Saville, M.P.’s suit against G. Johnstone M.P., Times January 25, 1802. The Earl of Darnley brought his former friend and relation, the Honourable Robert Bligh, to court a number of times for sending challenges or attempting to provoke a duel; for some of these see Times April 24, 1801 and August 15, 1805. There was also a suit in King’s Bench in which a Mr. Robert Knight charged his brother-in-law, the son of Lord Dormer, with sending him a letter which attempted to provoke a duel, Times November 27, 29, 1805.

102. See Times June 30, 1795.

103. For Craven’s appearance before the magistrates, see Times August 15, 1799; for St. Vincent and Orde, Times October 5 and October 8, 1799.

104. Times March 29, 1798.

105. For the Opera scuffle, see Times April 2, 1796; for the Newbon-Gibbons almost-duel, ibid., August 11, 1798.

106. Times February 3, 1800.

107. Ibid., September 30, 1796.

108. For the report of seconds being charged £200 see the Times August 12. 1806; those charged £500 each were reported in the Observer August 3, 1800.

109. Times May 4, 1785.

110. See ibid., February 20, 1799.

111. Ibid., June 2, 1794.

112. Ibid., February 5, 1798.

113. Ibid., November 20, 1798.

114. Ibid., February 11, 1799.

115. This fourth case can be found ibid., February 20, 1799. Kenyon’s self-characterization came in a case reported ibid., November 11, 1796.

116. On Erskine overpowered, see ibid., November 25, 1799, and Erskine on the other side, ibid., February 7, 1799.

117. Ibid., February 11, 1799.

118. Ibid., June 11, 1801; January 26, 1802.

119. Ibid., November 22, 1796, and the ruling on January 27, 1797; for the gallant naval Captain, ibid., November 23, 1799.

120. Part of the address of Captain Macnamara to the jury, at his trial in 1803, for the murder of Colonel Montgomery in a duel; see Lorenzo Sabine, Notes on Duels and Duelling (Boston, Crosby, Nichols, 1855), pp. 247–49.

121. Lord Ellenborough made this remark at a case brought to King’s Bench, in which both the challenger and challenged were merchants; see Times November 27, 1812.

122. For Lauderdale/Arnold duel, see ibid., July 2, 1792; for Norfolk/Malden duel, ibid., April 30, 1796, and for the Irish duel between A. Montgomery of Conway, Esq. and Sir Samuel Hayes of Drumboe, Bart., ibid., October 19, 1797.

123. Times March 2, 1792. For the Lauderdale/Richmond quarrel, see ibid., June 5 and June 6, 1792.

124. The Times, the Courier, and the MC reported the incident, but made no condemnatory comment about the duel itself. A very trenchant satirical poem, The Battle of the Blocks, was published shortly afterwards, a few lines of which deserve to be cited: “If this be honour, what is sense of shame?/If this be virtue, who shall murd’rers blame?” (London, Maxwell & Wilson, 1809, p. 14).

125. In his article, “Dandelions on the Field of Honour” Antony Simpson includes a chart of reports of duels which he has assembled from contemporary accounts. He has included in this chart all “duels reported in Britain, or involving Britons overseas.” Thus, for the years under consideration, he has found a greater number than I have. Probably the difference comes about in the scope of my search (I have eliminated all duels of Britons abroad) and the sources I’ve used to find such accounts (a reading of the eighteenth-century press combined with the utilization of the digitalized version of the Times of London).

126. For the Macnamara-Montgomery duel, see Times April 7, 1803, and for a “copy-cat” duel, resembling this first, and fought for the same motive, Times September 23, 1803. For the duel because of the billiard quarrel, see Times May 25, 1797. Lord Falkland, a Captain in the Royal Navy, called a Mr. Powell by “the familiar appellation of Pogey” and a duel followed, Times March 2, 1809. The duel about the girl occurred in Portsmouth, and was reported ibid., October 14, 1812.

127. As early as 1790, the press reported military trials in which officers challenged their superiors, and in which, in all cases, the challengers were found guilty, and faced a variety of punishments. Lieutenant Edwards challenged his Captain and was broke by a naval court, Times March 10, 1790; a naval tribunal found two men guilty for having challenged a Lieutenant Ferguson, ibid., December 30, 1791; a court-martial was held in Dublin against two Army Captains for having delivered a challenge, and being the challenger of the Earl of Bellamont, ibid., July 29, 1796; three young military men taken to Bow Street for challenging their Captain, ibid., October 3, 1797.

128. For the case of Major Armstrong, heavily punished for having challenged his superior officer, General Coote, to a duel, see ibid., June 21, 1800, and June 11, 1801. The King’s letter can be read ibid., July 8, 1800.

129. Rowland Ingram, Reflections on Duelling (London, J. Hatchard, 1804), pp. 98–99; Samuel Romilly, Times February 26, 1805; [John Taylor Allen] Duelling, an Essay (Oxford, S. Collingwood, 1807), pp. 19–20.

130. Rev. William Butler Odell, Essay on Duelling, in which the subject is Morally and Historically Considered; and the practice deduced from the Earliest Times (Cork, Odell and Laurent, 1814), p. 27.

131. Thus in 1823, George Buchan, in his Remarks on Duelling; comprising observations on the arguments in defense of that practice (Edinburgh, Waugh and Innes), argued that “It is an interesting thing, what greatly distinguishes the age in which we live, to see many officers, both naval and military, who now dare to be singular on such points [challenges to duel], and who now live under impressions little known a few years ago. This number is every year on the increase …” To newspaper readers, the incidence of reports of duels in the press might have seemed to suggest a similar decline, though the rate of this varied with the paper read:

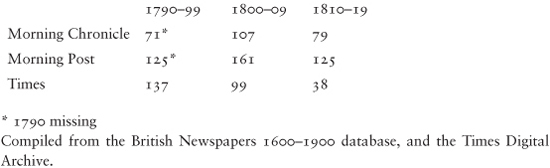

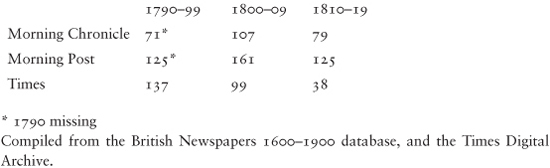

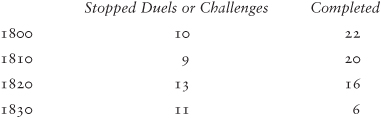

Number of duels reported

1. T&C December 1773, “Essay on Suicide,” p. 455.

2. The chapter title is taken from Thomas Knaggs, A Sermon against Self-murder (London, H. Hills, 1708), p. 2.

3. E. Arwaker, Aesop: Truth in Fiction, 4 vols. (London, J. Churchill 1708), “Fable XVII; The Fox and Sick Hen”; John Locke, Two Treatises on Government, ed. P. Laslett (New York, Mentor, 1963), p. 413.

4. Populousness with Economy 1757, pp. 21–22; David Mallet, Mustapha (London, A. Millar 1739), p. 134; John Herries, An Address to the Public on the frequent and enormous crime of suicide, 2nd. ed. (London, John Fielding, 1781), p. 3; advertisement for “Warren’s only True Milk of Roses for the Skin,” in the Gaz January 28, 1778.

5. The Occasional Paper: Number X. “Concerning self-murder. with some reflexion upon the verdicts often brought in of non compos mentis, in a letter to a friend” (London, M. Wotton, 1698), p. 35; John Jeffery, Felo de Se: or a Warning against the most Horrid and Unnatural Sin of Self-Murder in a Sermon (Norwich, A & J Churchill, 1702), pp. 13–14; Self-murther and duelling, p. 3. The Rev. Matthew H. Cooke, in his The Newest and Most Complete Whole Duty of Man (London, [1733?]), followed his essay on the evil of suicide (pp. 118–21) with one on the evils of duelling (pp. 121–23); similarly Caleb Fleming’s A dissertation upon the unnatural crime of Self-Murder, occasioned by the many late instances of suicide in this city (London, Edward and Charles Dilly, 1773, p. 21), followed his discussion of suicide with a similar analysis of duelling. For a later comment on the conjunction, see “A Poor Man’s” letter to the Gaz April 4, 1775.

6. Michael MacDonald & Terence R. Murphy, Sleepless Souls (Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1990), p. 184.

7. Occasional Paper, p. 10.

8. ‘The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark” in Shakespeare’s Tragedies (London, J. M. Dent, 1925), Act V, Sc. 1, p. 559.

9. Occasional Paper, p. 34; Self-murther and duelling, p. 6.

10. John Henley, Cato condemned, or the case and history of self-murder argu’d and displayed at large, on the principles of reason, justice, law, religion, fortitude, love of ourselves and our country, and example; occasioned by a gentleman of Gray’s inn stabbing himself in the year 1730, A theological lecture, delivered at the Oratory (London, J. Marshall, 1730), pp. 6–7; Jeffery, Felo de Se, p. 9; the London Journal August 15, 1724, letter signed “Theophilus.”

11. London Journal August 15, 1724, letter signed “Theophilus”; Occasional Paper, p. 2; Zachary Pearce, A Sermon on Self-murder [1736], 3rd edition (London John Rivington, 1773), p. 5.

12. Knaggs, Sermon, p. 6; Henley, Cato condemn’d, p. 4. See also Zachary Pearce, Sermon on Self-murder, p. 13, and Occasional Paper, p. 10.

13. See MacDonald and Murphy, Sleepless Souls, pp. 306–7. At times, it appears that they wish to have their cake and eat it; after arguing that polite society rejected supernatural appeals (and one would certainly think that university-educated clergymen might fit into this category) they note (p. 164) that “Even [clergy]men like Francis Ayscough and John Cockburn, who conjured with the name and shape of Satan, relied heavily on philosophical arguments in their sermons.” Are Ayscough and Cockburn here being blamed for invoking the Devil, or for employing philosophical arguments? At other times they show more wariness about what sorts of people continued to believe in the instigation of Satan, (see p. 211).

14. LM March 1762, p. 145; Occasional Paper, p. 33. Samuel Johnson agreed, arguing that human desires and impulses “though very powerful, are not resistless; nature may be regulated, and desires governed.” The Rambler #151, August 27, 1751.

15. Occasional Paper, p. 4.

16. The occasional comment on the weather does appear, such as in the article “Of Self-Murder” copied from the Universal Spectator and reprinted in the LM August 1732, p. 251. The much-copied letter on “Suicide and Self-Murder,” which first appeared in the Weekly Register of April 29, 1732, was reprinted in both the LM of April 1732, p. 32, and the GM of the same month and year, pp. 714–15; Occasional Poems (London, 1726), p. 22. Addison’s hero was Cato the younger, who killed himself; Self-Murther and Duelling, p. 7.

17. The Universal Spectator, April 13, 1734, p. 1; in 1736, a correspondent wrote to the Prompter (in an article later reprinted in the GM January 1736, p. 13, which is cited here) asking if his motives to suicide were not as admirable and justifiable as Cato’s. While Cato’s suicide had some admirers and many mitigators in the eighteenth century, it also had some fierce condemnations; see for example Paradise regained, or the battle of Adam and the Fox (London, J. Bew, 1780), p. 13; Richard Hey, Three Dissertations on the Pernicious Effects of Gaming (1783), on Duelling (1784) and on Suicide (1785) (Cambridge, J. Smith, 1812), pp. 3–4, William Combe, The Suicide from The English Dance of Death, 2 vols. (London, J. Diggens, 1815), 2: 11.

18. Knaggs, A Sermon, p. 14; GM 1756, p. 18; MacDonald and Murphy, Sleepless Souls, p. 202.

19. For a clear exposition of the philosophic deist view of suicide in this period, see MacDonald and Murphy, Sleepless Souls, pp. 150–64. LM July 1737, p. 375; Jeffery, Felo de Se, p. 17; GM April 1762, the lead article of that month, entitled “A Letter to a Friend, on Suicide and Madness,” p. 151; thanks for this reference to Randall McGowen.

20. This account of the deaths of the Smiths is taken from the report in the LM April 1732, pp. 37–38. Their deaths were also reported at considerable length in the GM of that month, pp. 722–23. This latter report is eerily detailed, noting the cleanliness of the Smiths’ clothes, the rope with which they hanged themselves, as well as the fact that Mrs. Smith was seven months pregnant. Both magazines also reprinted a letter on self-murder, first published in the Weekly Register, which the GM claimed (p. 714), was occasioned by “a late tragical catastrophe” and then cited the Smith suicides. See also MacDonald and Murphy, Sleepless Souls, pp. 157–58, 204–5.

21. Voltaire, The Works of Voltaire, 25 vols. (London, J. Newbery, 1761), 10: 31–32. Richard Hey, Dissertation on Suicide, p. 20. For another reference to this case, in an essay published just after the Budgell suicide, see LM May 1737, “On English Suicide,” from Fog’s Journal, pp. 289–90. See also MacDonald and Murphy, Sleepless Souls, pp. 319–21. Although the count of articles is unscientific and impressionistic, of the four vices covered in this book, accounts and discussions of suicide in the 1730s are a larger proportion of the total number of such items than similar discussions for the other vices in that decade.

22. Barbara Gates, Victorian Suicide: Mad Crimes and Sad Histories (Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1988) pp. 82–83; GM 1737, pp. 315–16; LM 1737, p. 274, see also the reference to the Budgell death, GM July 1737, p. 375. For Johnson, see George Birkbeck Hill, ed., Boswell’s Life of Johnson, 6 vols. (Oxford, Clarendon, 1887), 2:228–29. The suicide of Fanny Braddock, the third suicide much discussed in the eighteenth-century press, will be considered in chapter five.

23. MacDonald and Murphy, Sleepless Souls, p. 301. Though this chapter is, in many ways, a contrary interpretation of the impact of suicide on popular opinion in eighteenth-century Britain, I would like to express my appreciation for the magisterial quality of their book, and for the assistance it has afforded me in thinking about this difficult subject.

24. Ibid. MacDonald and Murphy argue that “the style and tone of newspaper stories about suicides promoted an increasingly secular and sympathetic attitude to self-killing.” I find few grounds for such a conclusion.

25. All cases cited come from Fog’s Weekly Journal of 1731; the Hunter and Clarke stories are found in the January 2, 1731 edition, the Shelton death in that of April 10, 1731. For a death which cites discontent of mind, see the report of the death of Evan Lewis in the March 20, 1731 edition.

26. LEP July 4, 1765. Lloyd July 5, 1765, noted that, in their column listing deaths, “His Grace the Duke of Bolton, Mq. of Winchester and premier Marquis of England, at his house in Grosvenor Square.” Horace Walpole to Mann, Correspondence, vol. 22, p. 312. For Scarborough, see LM 1740, p. 101, GM 1740, p. 37. The London Daily Post January 1, 1740 and the LEP January 29, 1740 reported his death as due to “an apoplecktick fit.” A review of a pamphlet “A Dialogue in the Elysian fields, between two Dukes,” in the July 1765 edition of the GM, p. 341, which only includes initials, hints that B – n (or Bolton) killed himself because he was refused an army posting. For Walpole’s comment on the use of “sudden” to indicate a suicide, see Correspondence, vol. 24, Letter to Mann 28 November 1779, p. 536.

27. GM September 1760, pp. 399–400, 404.

28. Lloyd June 28, 1765; I have not been able to locate this case elsewhere; GM September 10, 1765, p. 440; this story was also covered in the LM September 1765, p. 485; GM September 17, 1765, p. 441; GM October 30, 1765, p. 535; LM December 1765, p. 643. The rather mundane story was about the suicide of a Mr. Howard, a “schoolmaster and clerk of parish of Cambridgeshire” who, after killing a Mr. Webb who was attempting to seize his possessions for debt, cut his own throat. See LM November 1765, p. 596.

29. “Belinda’s” letter to the MC December 15, 1775; “AB’s” letter to the Westminster Magazine October 1775, pp. 524–25; review of Warton’s poems in the GM 1777, vol. 47, pp. 70–71; for their view of Blair, Warton, and the influence of “the graveyard poets” see MacDonald and Murphy, Sleepless Souls, p. 193.

30. See Gaz January 22, 1770; GM 1770, p. 47. See also, for reiterations, PA January 22, 1770, Mdsx January 20, 1770, LM 1770, p. 53. The epitaph appeared in the GM p. 60 and the LM p. 61 of January 1770.

31. MC November 24, 25, 1774; LC November 24, 1774; GM 1774, p. 542; LM 1774, p. 562; the letter in MC November 28, 1774.

32. T&C May 1778, “A Dialogue in the Shades,” pp. 243–44; GM 1789, pp. 1080–81, “Reflections on the Laws concerning Suicide” by “J. A.” The rebuke to Kippis came in a letter by “Academicus,” published in the GM 1785, p. 260.

33. Forrest’s obituary appeared in the GM November 1784, pp. 877–78, “HOC’s” critical response in the same journal, December 1784, pp. 963–64.

34. Gaz August 17, 19, 20, 1776; MP August 19, 20, 1776. The GM (vol. 46, August 1776, p. 383) referred to him as the Hon. C, son to Lord C.

35. Both the GM August 1776, p. 383 and the Gaz August 19, 1776 noted his fiscal worth and the Gaz also reported the company that Damer kept just before the fatal shot; the debt was reported by the Gaz and the MP August 20, 1776, as were comments on the annuities he had granted. The GM had described him as “eccentric” and the explanations in the MP came on consecutively on August 19 and 20, 1776. MacDonald and Murphy also discuss Damer’s suicide, but in a different context, see Sleepless Souls, p. 280.

36. The briefest notices of his death are found in the LC November 5, 1774; the LM 1774, p. 592, the PA November 8, 1774 and the MP November 9, 1774. “The Character of a Placeman” with a very complete description of Bradshaw’s career, appeared in the December 1774 issue of the LM, pp. 591–92.

37. For Powell’s death, see MH May 28, 1783, GM 1783, p. 454, p. 539, “X.Y.,” “Anecdotes of the late Mr. Powell” and pp. 612–13, for evidence from the Coroner’s jury. “X.Y.” suggested that the testimony about Powell’s mental incapacity may have been tainted by noting that Fox “found [Powell] a very useful friend,” that Powell had helped Burke “in the accomplishment of a reform in the little abuses of his office.” Again, MacDonald and Murphy add interesting features of these cases, but with very different emphases; see Sleepless Souls, p. 281.

38. Since there were no formal or legal requirements for medical certificates stating the cause of death, or any registration of deaths in England until the passage of the 1836 Births and Deaths Registration Act, it seems quite possible that several instances of suicide were concealed by the families of notable men and women. For more on this, see J. D. J. Havard, The Detection of Secret Homicide (London, Macmillan, 1980), p. 39.

39. The deaths of these thirteen men (Thomas Bradshaw, Robert Clive, John Crowley, John Damer, William Fitzherbert, J. G. Goodenough, Sir George Hay, Hesse, Sir William Keyt, William Bromley, Lord Montfort, Perry, Hans Stanley) stretch from the earliest, Sir William Keyt in 1741 to the last, Lord Saye and Sele in 1788. Keyt’s death, by self-immolation, Damer’s by pistol, Hesse’s, in 1788, Powell’s, and Saye and Sele’s were the only ones that the papers described as self-inflicted. There is an account in the Gaz January 6, 1772, which may be that of William Fitzherbert; the victim is referred to only as “a certain Member of Parliament.” For Saye and Sele’s suicide, see the World July 4, 1788 and for Walpole’s letter, see Correspondence, vol. 31, p. 267.

40. See Andrew, London Debating Societies, especially November 4, 1789, pp. 266–67.

41. Lady’s Magazine June 1773, pp. 298–299; letter from “Plato” in the St. J January 8, 1780. For more see T&C June 1783, “On Suicide,” p. 321 and Evening Chronicle June 3, 1788.

42. Letter in MC November 1774; Times August 12, 1790; MH February 25, 1785 and Public Advertiser March 4, 1785 for Captain Battersby.

43. See the Sentimental Magazine September 1775, pp. 390–92. James Boswell, The Hypocondriack, December 1781, p. 262. For a balanced and unemotional account of Sutherland’s life and death, see the AR 1791, pp. 34–35; the fragment appeared in the Times August 22, 1791. This sort of emotionalism was clearly a very potent and widely sought experience. After the suicide of Eleanor Johnson, a servant girl of seventeen, for the love of a black man named Thomas Cato (a perhaps inauspicious name as things turned out), not only did the Times print the account of her life, death, and inquest in some detail, but copied the entire tear-streaked letter she wrote to Cato, September 25, 1789. This death also occasioned a debate at the Coachmaker’s Hall Debating Society on the question “Does suicide proceed mainly from a disappointment in love, a state of lunacy, or from the pride of the human mind?” Times November 12, 1789. See also MacDonald and Murphy, Sleepless Souls, pp. 195–96.

44. T&C August 1792, “Reflections on the Prevalence of Suicide in England and Geneva,” pp. 351–52.

45. The earliest reports in the Times, the MC, the MP, and the PA of June 4, 1788 are identical, except for the brief notice in the Times explaining their earlier suppression of the story. The second reports, which the Times entitled Farther Particulars of the late Mr. HESSE, were also identical and appeared in the Times, the MP, and the PA on June 5, 1788. This case is discussed in MacDonald and Murphy’s Sleepless Souls, (pp. 189–90) but seen quite differently. They instead report that the “papers were elegiac” and that the Times “reporter recounted his life and death without a critical word.” I think, even in the Times, though most explicitly in some of the other papers, criticism could be, and was read by contemporaries, in the detailed descriptions of Hesse’s property and prosperity, blown away by a propensity for “deep play.”

46. Both the English Chronicle of June 3, 1788 and the General Evening Post of June 5, 1788 contain the comment about Hesse’s “connexions too splendid.” Hesse’s desire to partake of the gay life with the Great is also found in the English Chronicle of June 3, 1788 and the PA June 5, 1788.

47. GEP June 5, 1788. See also the sentimentalized account of Hesse’s widow in the next edition of this paper, June 7, 1788.

48. MP June 6, 1788, June 7, 1788. The story about the practical trick appeared in the Star and Evening Advertiser June 6, 1788.

49. On the Death of Mr. Hesse in the PA June 9, 1788; EPITAPH on Mr. Hesse by Edw. Beavan in the T&C July 1788, pp. 334–35.

50. The paragraph linking bankruptcy and suicide appeared in The Star and Evening Advertiser of June 6, 1788, in the English Chronicle of June 3–5, 1788, and its first sentence in the Times June 6, 1788. Interestingly the Times continued without mentioning the two suicides alluded to by the other papers, but used the occasion to suggest the need for a general moral reform.