SIMPLIFIED CHART OF HAWAIIAN AIR FORCE AS OF DECEMBER 7, 1941

(UNDER OVERALL COMMAND OF GENERAL SHORT

When the Army transport Leonard Wood arrived in Honolulu on Saturday night, November 2, 1940, a tall gentleman walked down the gangplank. He had waving gray hair and thick brows shadowing pleasant eyes. His thin face with its oblong jaw, big nose, high forehead, and large ears looked more scholarly then military.

Major General Frederick L. Martin won his wings at the age of thirty-nine, when he was already a major. He completed courses at the Air Tactical School at Langley Field, Virginia, and the Command and General Staff School at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. Then followed a series of command assignments. Further study brought him to the Army War College. After duty at Wright Field, Ohio, he took over command of the Third Bombardment Wing at Barksdale Field, Louisiana, in the spring of 1937 with the temporary rank of brigadier general. On October 1, 1940, he became a temporary major general, and concurrently received his orders to command the Hawaiian Air Force, activated on November 1. With his two stars, he could deal with Herron and later with Short, if not on terms of equality, at least within reaching distance. When he took over his new post, he ranked as the Air Corps’s senior pilot and technical observer and had logged 2,000 hours of flight time.1

Martin was not in the best physical condition and appeared older than his fifty-eight years. He had earlier developed a severe, chronic ulcer condition, which required surgery and undermined his health. As a result, he had not touched an alcoholic drink in years. His assignment placed him in an ambiguous position. As commander of the Hawaiian Air Force he had direct access to Major General H. H. “Hap” Arnold, chief of the Army Air Corps, but he remained under the command of Short, a foot soldier to the soles of his boots. The situation could have been delicate, and indeed, Martin had received specific instructions from Arnold to end the undeclared civil war which had raged on Oahu between the Army, its Air Corps, and the Navy and for which it appears some of the blame rested with the airmen.2

SIMPLIFIED CHART OF HAWAIIAN AIR FORCE AS OF DECEMBER 7, 1941

(UNDER OVERALL COMMAND OF GENERAL SHORT

To understand the American commanders on Oahu in 1941, one must see them in the context of the problems which bedeviled them. So Martin came to Hawaii bearing an olive branch. He took his role very seriously and at times, in the interests of harmony, would abandon a point which his fellow airmen thought he should have followed up more vigorously. His eagerness to please, combined with his rather pedantic appearance and manner, caused some individuals privately to label him a “fuddy-duddy.” But the estimate did the man less than justice, for he was a hardworking, dutiful, and loyal officer, although a worrier who fretted constantly lest he not accomplish enough. With Martin’s appointment, interservice relations improved steadily throughout 1941.3

On December 17, after about six weeks on the job, he wrote to Arnold: “These islands . . . have very few level areas suitable for the location of landing fields. Of the level areas in existence, the greater part of these are under cultivation in pineapples or sugar cane. . . . It is my purpose to provide an outlying field for each of the combat squadrons. . . .” Martin did not want his planes huddled together so that an enemy would have easy pickings if he swooped in on them. Presently he came to his major worry: “We have been satisfied in the past to supply our units in foreign possessions with obsolescent equipment until organizations in the States have been equipped with modern types. This to me is very faulty and could, in these times of uncertainty, be very detrimental to our scheme of national defense. . . .”4

Martin’s naval counterpart was an extroverted Irishman, Rear Admiral Patrick N. L. Bellinger, who had arrived in Hawaii on October 30, 1940. He had a full thatch of dark hair parted on the left side, a rather long mouth, and direct, bright eyes. He had a most distinguished flying career with any number of Navy firsts on his record. Now at Pearl Harbor, he held no fewer than five positions and theoretically answered to five different superiors. These multiple responsibilities bothered him much less than they did a swarm of postattack investigators, and in fact, such assignments have never been rarities in the armed services.

Bellinger was not a profound thinker, but he stood obstinately by his convictions and expressed them forcibly, constantly “beefing up” the letters which his brilliant operations and plans officer, Commander Charles Coe, prepared for his signature. But he had no ounce of bluster in him, and his invincibly sunny disposition made him a general favorite.5 Like Martin, he was running a poor man’s game and had no inhibitions about sounding off loud and clear even to the highest quarters about his troubles. On January 16, 1941, he wrote a strong letter to Stark:

1. I arrived here in October 30, 1940, with the point of view that the International situation was critical, especially in the Pacific, and I was impressed with the need for being ready today rather than tomorrow for any eventuality that might arise. After taking over command of Patrol Wing TWO and looking over the situation, I was surprised to find that here in the Hawaiian Islands, an important naval advanced post, we were operating on a shoestring and the more I looked the thinner the shoestring appeared to be.

. . . As there are no plans to modernize the present patrol planes comprising Patrol Wing TWO, this evidently means that there is no intention to replace the present obsolescent type. . . . This, together with the many existing deficiencies, indicates to me that the Navy Department as a whole does not view the situation in the Pacific with alarm or else is not taking steps in keeping with their view. . . .

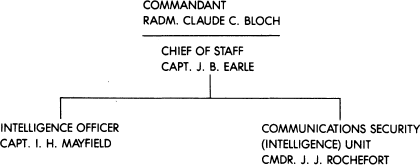

SIMPLIFIED CHART OF 14TH NAVAL DISTRICT AS OF DECEMBER 7, 1941

As commandant, Fourteenth Naval District, Bloch was directly under the Navy Department. He was also commander, Hawaiian Naval Coastal Sea Frontier; commandant, Pearl Harbor Navy Yard. He was also an officer of the Fleet and under CinCPAC as commander, Naval Base Defense Forces, and commander, Task Force Four.

As commander, Naval Base Defense Forces, Bloch had administrative control over

RADM. P. N. L. BELLINGER

Bellinger held down four positions:

1. Commander, Hawaiian Based Patrol Wing and Commander, Patrol Wing Two.

2. Commander, Task Force Nine (Patrol Wings One and Two with attending surface craft).

3. Liaison with commandant, Fourteenth Naval District.

4. Commander, Naval Base Defense Air Force.

He was responsible theoretically to the following superiors:

1. Commander, Aircraft Scouting Force (type command for patrol wings), based at San Diego.

2. Commander, Scouting Force, of which Patrol Wings One and Two were a part.

3. CinCPAC when commanding Task Force Nine.

4. Commanders of Task Forces One, Two, and Three for patrol planes assigned those forces.

5. Commandant, Fourteenth Naval District in Bloch’s capacity as commander, Naval Base Defense Force, when Bellinger was performing duties as commander, Naval Base Defense Air Force.

This was a heavy punch for a rear admiral to swing at the Chief of Naval Operations. Bellinger urgently recommended that “immediate steps be taken to furnish the personnel, material, facilities and equipment required. . . .” After he had laid it squarely on the line, his generous nature reasserted itself, and he added, “The tremendous and all consuming work of those in the Navy Department is fully appreciated and there is no intent to criticize or to shift responsibility.” He ended with a businesslike list of specific recommendations.6

That Bellinger was not talking through his five hats when he spoke of the vital role of patrol planes we know from a remarkable document dated March 31, 1941. This project had its genesis when Kimmel summoned Bellinger to his office on about March 1 and directed him to report to Bloch at the Fourteenth Naval District and get together with Martin to work out a plan for joint action in the event of an attack on Oahu or fleet units in Hawaiian waters.7

Bloch’s assignment consisted of overall responsibility for the great naval base, its vast maintenance shops, the precious, potentially dangerous farm of fuel tanks, harbor defenses, and security. It included innumerable housekeeping functions, such as housing, feeding, and clothing the men of the Fleet as well as of the shore installations. Bloch was also responsible for whatever naval elements could be made available for the defense of Pearl Harbor. He therefore had a very direct interest in the air protection of the installation and the ships.

Of course, Martin and Bellinger did not sit down at a double desk, roll up their sleeves, and proceed to write their report alone. Some of their bright staff members did the spadework, but the two flag officers worked closely with them and accepted and signed the report. So they can claim a full measure of credit.

In its final form this historic work became famous to all students of the Pacific war as the Martin-Bellinger Report. It speaks for itself clearly and crisply. Its “Summary of the Situation” observed, among other things:

(c) A successful, sudden raid against our ships and Naval installations on Oahu might prevent effective offensive action by our forces in the Western Pacific for a long period. . . .

(e) It appears possible that Orange submarines and/or an Orange fast raiding force might arrive in Hawaiian waters with no prior warning from our intelligence service.

The document then considered the capability of Japan in terms of actual strength: “(a) Orange might send into this area one or more submarines and/or one or more fast raiding forces composed of carriers supported by fast cruisers.”8 One notes a striking difference from Kimmel’s Pacific Fleet letter of February 15. The two airmen, Martin and Bellinger, estimated that enemy carriers would be “supported by fast cruisers,” instead of vice versa. These experienced exponents of aerial warfare were thinking along the same lines as Genda. The report continued: “The aircraft at present available in Hawaii are inadequate to maintain, for any extended period, from bases on Oahu, a patrol extensive enough to insure that an air attack from an Orange carrier cannot arrive over Oahu as a complete surprise. . . .” Here in a nutshell was the dilemma of Oahu’s defenders—the need for a 360-degree arc of patrol without the planes necessary to accomplish such a mission.

In the area of “Possible Enemy Action,” the authors virtually foretold the future:

(a) A declaration of war might be preceded by:

1. A surprise submarine attack on ships in the operating area.

2. A surprise attack on Oahu including ships and installations in Pearl Harbor.

3. A combination of these two.

(b) It appears that the most likely and dangerous form of attack on Oahu would be an air attack. It is believed that at present such an attack would most likely be launched from one or more carriers which would probably approach inside of three hundred miles.

(c) A single attack might or might not indicate the presence of more submarines or more planes awaiting to attack after defending aircraft have been drawn away by the original thrust.

(d) Any single submarine attack might indicate the presence of a considerable undiscovered surface force probably composed of fast ships accompanied by a carrier.9

Someone let a discrepancy slip by with this observation or else did not appreciate the vital difference between “carriers supported by fast cruisers” and “fast ships accompanied by a carrier.” In fact, these estimates of enemy action somewhat echo the existing Pacific Fleet letter.

(e) In a dawn air attack there is a high probability that it could be delivered as a complete surprise in spite of any patrols we might be using and that it might find us in a condition of readiness under which pursuit would be slow to start, also it might be successful as a diversion to draw attention away from a second attacking force. . . . Submarine attacks could be coordinated with any air attack. . . . 10

The possibility of such undersea craft prowling into the Hawaiian area was a nasty one. Actually Martin and Bellinger went somewhat ahead of Onishi and Genda’s original plan for a Pearl Harbor attack, which did not envisage the use of submarines.

What then could Kimmel, Bloch, and Short do about a potential Japanese attack? Martin and Bellinger had this answer:

(a) Run daily patrols as far as possible to seaward through 360 degrees to reduce the probabilities of surface or air surprise. This would be desirable but can only be effectively maintained with present personnel and material for a very short period and as a practicable measure cannot, therefore, be undertaken unless other intelligence indicates that a surface raid is probable within rather narrow time limits.11

Thus, into two short sentences Martin and Bellinger unknowingly compressed an awesome American tragedy.

The two planners next went into thorough detail concerning “Action open to us,” but pointed out the painful fact that no actions could “be initiated by our forces until an attack is known to be imminent or has occurred. On the other hand, when an attack develops time will probably be vital and our actions must start with a minimum of delay.”12

Martin and Bellinger could not have done a much better job of mind reading had they actually looked over the shoulders of Yamamoto, Onishi, Genda—and others. For in Japan the Pearl Harbor circle was widening even as Oahu’s planners labored over their report. The final document bore the date of March 31, 1941, approximately the same time that Yamamoto put his Combined Fleet staff to work on his design.

Washington was pleased with the Martin-Bellinger Report. “We agreed thoroughly with it, approved it,” said Turner, “and it was very comforting and gratifying to see that officers in important commands out there had the same view of the situation as was held in the War and Navy Departments.”13

The Martin-Bellinger Report stands as a workmanlike, almost inspired example of defensive planning, but along with the Joint Coastal Frontier Defense Plan of which it was an annex, it had a basic flaw. The findings of the Navy Court of Inquiry into the Pearl Harbor disaster summarized this clearly:

The effectiveness of these plans depended entirely upon advance knowledge that an attack was to be expected within narrow limits of time and the plans were drawn with this as a premise. It was not possible for the Commander in Chief of the Fleet to make Fleet planes permanently available to the Naval Base Defense Officer, because of his own lack of planes, pilots, and crews and because of the demands of the Fleet in connection with Fleet operations at sea.14

Under paragraph 18 (1) of the basic plan Short transferred responsibility for long-range aerial reconnaissance to Bloch’s Fourteenth Naval District, retaining only scouting some twenty miles offshore.15 The wisdom of this switch is questionable because the Hawaiian Department was charged with the protection of the Fleet in harbor as well as with defense of the Islands, and long-range air scouting was a fundamental tool of this mission. But cold facts dictated the decision, for Short and Martin never had at any time more than a handful of the planes necessary for the required wide swing around Hawaii. Under the Short-Bloch agreement, when the latter’s aircraft were insufficient for the mission, the Hawaiian Air Force would make planes available “under the tactical control of the Naval commander directing the search operations.”16

When Bloch accepted this solemn responsibility, he “had no patrol planes permanently assigned to his command. . . . The only Naval patrol planes in the Hawaiian area were the 69 planes of Patrol Wing Two and these were handicapped by shortage of relief pilots and crews.” Unfortunately, the aircraft of Patrol Wing Two never came to a total large enough for a meaningful search arc. More important, “The task assigned the Commander in Chief . . . was to prepare his Fleet for war. . . . The Fleet planes were being constantly employed in patrolling the operating area in which the Fleet’s preparations for war were being carried on.”17

On April 1, exactly one day after the dating of the Martin-Bellinger Report, Naval Intelligence in Washington alerted the commandants of all naval districts—including the Fourteenth at Hawaii—as follows:

Personnel of your Naval Intelligence Service should be advised that because of the fact that from past experience shows sic the Axis Powers often begin activities in a particular field on Saturdays and Sundays or on national holidays of the country concerned they should take steps on such days to see that proper watches and precautions are in effect.18

Another link in the chain of prediction! If Japan took the plunge, the defenders could expect it to be on a Saturday, Sunday, or national holiday.

While military leaders on Oahu were busy developing plans to meet a possible Japanese attack, many Americans conceived of Hawaii as an impregnable fortress. A vast protective belt of water shielded Oahu on all sides. Some military experts considered the great area of “vacant sea” to the north the best and most likely avenue of approach for the enemy, but by the same token it provided an open highway of exposure and detection. The undeniable argument that Japan had a vast ocean in which to approach Oahu could be countered by the simple fact that Hawaii commanded all seaways in the central Pacific. Moreover, a screen of outlying bases into which the United States was pouring millions of defense dollars flanked Oahu. Midway lay 1,300 miles to the northwest; Wake about another 1,000 miles west and somewhat southward. Johnston Island, a white spear of land, barely crested the waves 700 miles to the southwest, with Palmyra 1,000 miles due south. Still other American and British possessions stretched beyond this defensive rim. Up in the Aleutians a new naval and air base at Dutch Harbor guarded the northern Pacific and flanked Japan’s shortest line of approach to the West Coast.

U.S. naval strength was concentrated heavily at Pearl Harbor. Here, at any time the Fleet moved out in stately maneuver, one could see fighting craft of all descriptions—six to eight battleships; two or three aircraft carriers; numerous heavy and light cruisers; dozens of destroyers, submarines, minesweepers, and auxiliary craft. Oil storage tanks, dry docks, workshops, and many other shore installations made Pearl Harbor virtually an independent maintenance base. Here, in the “Navy behind the Navy,” the entire Fleet could dock, fuel, supply, and undergo repairs. From this great mid-Pacific pivotal point it could swing into action at a moment’s notice and strike hard at the enemy in any direction. Hawaii was proud of its guardian of the seas. “If there were ever men and a fleet ready for any emergency,” bragged the Honolulu Advertiser on February 1, 1941, “it’s Uncle Sam’s fighting ships.”

The Army, too, bent every effort to make good the boast that Pearl Harbor was “the best defended naval base in the world.” In 1941 Oahu had a strong garrison of about 25,000 troops. Armed with all the tools of modern warfare, kept rugged and alert by constant field exercises, these soldiers were expertly trained in the defense of the island. And if the Japanese sideslipped the American outer defense posts or succeeded in fighting through the Pacific Fleet, the Hawaiian Air Force stood ready to help smash any attack. Bombers stationed at Hickam Field gave the Air Force potent scoring punch, and the latest fighter planes organized in effective squadrons at Wheeler Field assured mastery of the skies over Oahu. In case the enemy got too close or tried to land there, field guns stood ready. Well could Short say on April 7: “Here in Hawaii we all live in a citadel or gigantically fortified island.”19

Little wonder that so many Americans extolled their mid-ocean bastion with glowing confidence and no doubt would have regarded the Martin-Bellinger Report, could they have seen it, as a worthy but academic school exercise having no relationship to the realities of geography or logistics.