Chapter 1

The Influence Model

Once when William Allen White visited Boston, two young reporters, Louis Lyons of The Boston Globe and Charles Morton of the Transcript, sought him out for an interview. The sage of Emporia put his arms around the two men and said, “We all have the same face. It is not an acquisitive face.”1

Later, when he was curator of the Nieman Foundation (1939– 1964), Lyons recalled that moment and advised young journalists to work for organizations that put service to society above the values of “a banker or an industrialist.” Today, he might say above the values of “a hedge fund or a mortgager broker.” But it's the same idea.

The glory of the newspaper business in the United States used to be its ability to match its success as a business with self-conscious attention to its social service mission. Both functions are threatened today. Measured by household penetration (average daily circulation as a percent of households), this mature industry peaked early in the 1920s at 130.2 By 2007, newspaper household penetration was down to 44 percent.3 But while household penetration declined, newspaper influence and profitability remained robust for most of the twentieth century. Now both are in peril.

The decay of newspaper journalism creates problems not just for the business but for society. One problem is basic: to make democracy work, citizens need information. “Knowledge will forever govern ignorance,” warned James Madison, “and a people who mean to be their own governors must arm themselves with the power which knowledge gives.”4 Democracy was more manageable when mass media and its associated advertising for mass-produced goods tended to mold us into one culture. But that started to change after World War II. For some time now, historians have seen the world in three stages: a pre-industrial period, when social life was local and small in scale; the industrial period, which made both mass communication and mass production possible; and the third or post-industrial stage, which shifted economic activity from manufacturing to services. Journalism professors John Merrill and Ralph Lowenstein described the effect of these changes on our media system in 1971.5 The mass media were already starting to break up the audience into smaller and smaller segments, promoting what sociologist Richard Maisel called “cultural differentiation.” If we're all attending to different messages, our capacity to understand one another is diminished. Even in the 1960s when Maisel started working on this issue, he could see decreasing support for educational institutions as one consequence of the differentiated culture. That trend has continued.

It might take a different kind of journalism, backed by a different kind of financial support, to keep us together. For our social and political health, we need to understand enough about the business of journalism to try to preserve it in new platforms.

The literature of business administration has a theoretical framework that provides a good place to start. Theodore Levitt popularized the term “disruptive technology” and captured the imagination of a generation of executives when he wrote “Marketing Myopia” for Harvard Business Review in 1960.6 One of his examples came from the experience of the railroads. Their managers clung stubbornly to the narrow definition of their enterprise: they were in the railroad business. If only they had seen that they were in the transportation business, they might have been prepared when people and cargo began moving through metal tubes in the sky and along asphalt ribbons on the ground.

This model invites some rethinking of what business newspapers are, or should be, in. If you believe the Wall Street analysts most widely quoted in the trade press, newspapers are in the business of delivering eyeballs to advertisers. Everything not directly related to that is unrecovered cost.

Frank Hawkins was the director of corporate relations for Knight Ridder in 1986, a year when that group won seven Pulitzer Prizes. On the day of the announcement, the value of the company's shares fell. Hawkins called one of the analysts who followed the company and asked him why.

“Because,” he was told, “you win too many Pulitzer Prizes.”

Too many? Yes, the analyst said. The money spent on those projects should be left to fall to the bottom line.7

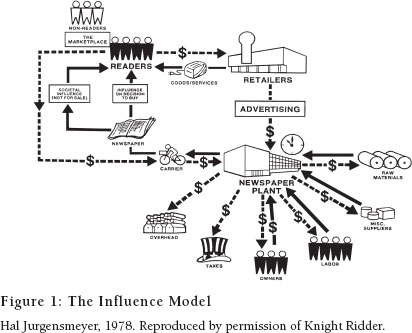

Knight Ridder at that time had another view. It was articulated for me in 1978 when I was posted from the Washington Bureau to corporate headquarters in Miami to serve as the company's first director of news research and help create an experimental electronic home information service. Hal Jurgensmeyer (1931–1995), a business-side vice president of the company, briefed me on the assignment. We were, he said, not in the news business, not even in the information business. We were “in the influence business.” The sketch in Figure 1 is his.

A newspaper, in the Jurgensmeyer model, produces two kinds of influence: societal influence, which is not for sale, and commercial influence, or influence on the consumer's decision to buy, which is for sale. The beauty of this model is that it provides economic justification for excellence in journalism.

A news medium's societal influence can enhance its commercial influence. If the model works, an influential newspaper will have readers who trust it and therefore be worth more to advertisers.

Consider the supermarket tabloids. A front page that pretends to depict a presidential candidate chatting with an alien from outer space is going to attract only that limited subset of advertisers that depends on the most naively credulous subset of the population. A glance at the ads in such a newspaper bears out this supposition: ads for psychics and fake medical products, e.g. pills that cause you to lose weight while you sleep.8

The disruption from technology in the newspaper case is more complicated than the railroad example and others used by Levitt. In those cases, the problem was one of straightforward product substitution. Cars were faster and more durable than horses, planes were faster than trains, natural gas was cheaper to process and transport than oil. For media, new technologies do all that. They make information faster, cheaper, and, through electronic archiving, more durable. But they also change the nature of the audience. The new problem is overload on the audience's ability to receive and consider the messages.

This phenomenon was under way long before the Internet appeared. Offset printing, which made it possible to create printing plates with a photographic process instead of hot lead, reduced the high fixed costs of publishing. Then computers made it easy to lay out a page at an editor's desk instead of by cutting and pasting in the back shop. The advances in printing technology opened the door to specialized publications with smaller audiences. Cheaper, slicker printing also made direct-mail advertising attractive and contributed to the demassification of the media long before there was an Internet.

The Scarcity of Attention

Herbert A. Simon saw the media overload problem coming. In one of a series of lectures sponsored by the Johns Hopkins Institute for Advanced Studies in Washington, D.C., in 1969–1970, he compared the surplus of information to his children's surplus (in his mind) of pet rabbits. They made the lettuce supply scarce. So it is with the wealth of information which “means a dearth of something else: a scarcity of whatever it is that information consumes.”

“What information consumes,” he said, “is rather obvious: it consumes the attention of its recipients. Hence a wealth of information creates a poverty of attention and a need to allocate that attention efficiently among the overabundance of information sources that might consume it.”9

The national newspaper USA TODAY was one response to the problem. As originally designed, it let users scan the newspaper quickly and evaluate a large number of brief items. In most cases, the brief report was enough. A reader might want to follow up with other sources, but the newspaper had performed the service of alerting him or her. Harold Lasswell called this “the surveillance function.” We all need a brief and efficiently presented heads-up about the dangers and opportunities that each new day presents.10

But few newspapers have copied that aspect of USA TODAY, and it has itself moved on to a more conventional mix of long and short stories. While there have been innovations in graphics and design for better information retrieval, the newspaper industry's main response to substitute technology has been to reduce costs and raise prices. Some of the savings were achieved with better production technology. Others came from making the editorial product cheaper. Even as readership lagged, newspaper publishers congratulated themselves in the trade press for their ability to put out cheaper products while raising ad rates and subscription prices.

The strategy was possible because of newspapers' historically strong market position. Many newspaper owners—not all, of course—gained monopoly or near-monopoly situations by taking care to maintain the respect of their communities. For most of the twentieth century, newspapers were family businesses, run for the long term, attending to market share more than profitability. As the families sold to bigger organizations, the economics of publishing weeded out the weaker operations and built the eventual monopolies. Market share was no longer an issue. Yet, for many, this sense of obligation to community persisted.

The Harvesting Strategy

In recent years, as ownership shifted from individuals and families to shareholders guided by professional money managers and market analysts, a shorter-time horizon came to dominate American business in general. The newspaper industry was no exception. At the same time, the newest of the disruptive technologies, online information service, offered the most dangerous product substitution yet, especially in classified advertising. There is a textbook solution for a mature industry that is unable to defend against a substitute technology. Harvard professor Michael E. Porter called it “harvesting market position.”11

A stagnant industry's market position is harvested by raising prices and lowering quality, trusting that customers will continue to be attracted by the brand name rather than the substance for which the brand once stood. Eventually, of course, they will wake up. But, as the harvest metaphor implies, this is a nonrenewable, take-the-money-and-run strategy. A given crop can be harvested only once.

At the start of the twenty-first century, newspaper managers appeared to be harvesting—not so much for Porter's end-game strategy as to gather the financial resources to transfer the brand name to new ways of delivering news and advertising. Such a transfer requires investment, of course, and the problem was to generate the resources, without damaging the brand, in order to engage in costly experiments with new forms of media. But risk taking came hard to an industry with such a long history of success, and the most interesting experiments with new media tended to come from elsewhere. Paying for new media ventures with shrinking news space and diminished reporting was itself a risky action, putting the newspaper industry's precious community influence in peril.

While today's investors might think it perverse, the notion of service to society as a function of business is neither new nor confined to those protected by the First Amendment. Henry Ford argued that profit was just a byproduct of the service to society that his company performed.

In 1916, Ford was sued by the Dodge brothers, Horace and John, who were counting on dividends from their 10 percent stake in Ford to invest in their own car company. To their dismay, Ford had increased wages and cut prices at the same time. The brothers said he wasn't doing his duty to shareholders. Their counsel tried to trap Ford into admitting that.

“Your controlling feature, then,” he asked Ford at the trial, “is to employ a great army of men at high wages, to reduce the selling price of your car so that a lot of people can buy it at a cheap price and give everybody a car that wants one?”

“If you give all that,” said Ford, “the money will fall into your hands. You can't get out of it.”12

The compatibility of profit and social virtue is not novel in capitalist theory. Such an absolutist as Milton Friedman has argued for “justly obtained profit.”13 And when newspapers were mostly owned by private individuals and families, the best of them tended to treat profitability as Ford did, as incidental to the main focus of business—making life better for themselves, their customers, and their employees.

Because a newspaper is so central to the functioning of its community, both for the commercial messages and the societal influence, the social pressure on a resident owner can be immense. And when publishers expanded into other markets, as the Knight brothers did from the base their father established in Akron, they tended to be careful about their standing in their new communities. Like Henry Ford, they had all the money they needed to meet their personal needs and desires. Ford sounded a lot like a newspaper publisher when he said all he wanted was “to have a little fun and do the most good for the most people and the stockholders.”14

Ford was also assuring himself of market share, which in a new technology business, can be far more important than immediate profitability. In the early years, Ford Motor Co. was one of some 150 car makers. Like the dot-com entrepreneurs of today, he realized that to rise from the pack, he would have to create a product for a mass market.

When newspaper companies began going public in the 1960s, Wall Street was not immediately impressed. It was a mature industry, and the disrupting technologies were already apparent. Television had eaten into newspaper's share of national advertising, and cheaper, slicker printing was making it possible for highly specialized publications to thrive with narrowly directed advertising.15

Moreover, the people who analyzed media businesses lived mostly in the large cities where they could see newspapers dying or consolidating steadily since World War II. It took Al Neuharth of the Gannett Co. to show them the profit potential of monopoly newspapers in small and medium size markets.

These monopolies had not, for the most part, been managed to maximize near-term profitability. Their owners, partly out of a sense of social responsibility and partly with an eye on the long-term health of their companies, were more interested in influence than in maximizing their fortunes.

The Cowles family of Minneapolis and Des Moines was an example. When it sold The Des Moines Register in 1985 to Gannett Co., the paper covered the entire state of Iowa and had a tidy 10 percent operating margin.

Gannett's finance people looked at the operation, saw no economic value in its statewide influence, and cut circulation back to the area served by advertisers in the Des Moines market. That saved money on the main variable costs, newsprint and ink. Two of five state news bureaus were eliminated. The operating margin went quickly to 25 percent.

Charles Edwards was publisher during the transition. “All these things, in and of themselves, one individual move wouldn't necessarily be devastating to the quality or the capacity of the newspaper to do good journalism,” he said. “But collectively it had a huge impact . . . over time we just no longer had the capacity and the resources to do the kind of work we'd done.”16

That ability to do journalism beyond the necessary minimum to maintain a platform for advertising, the capacity to do journalism with a broader purpose of maximizing a newspaper's influence—call it the influence increment of the business—existed in many markets. By systematically siphoning it out, the owners in these markets could give Wall Street the illusion that their mature and fading business was a growth industry. (Wall Street's myopic preoccupation with quarter-to-quarter changes in earnings helped, of course.)

W. Davis Merritt, former editor of the Wichita Eagle, told a similar story. In the mid 1990s, Knight Ridder told him and his publisher to increase the operating margin to 23.5%.

“We looked and looked, and the only way we could do that was to cut 10,000 circulation, reducing all our commitment anywhere west of Wichita. We had to tell 10,000 people who were buying and reading our paper, we're not going to let you buy our paper anymore.”

That was damaging to Wichita, Merritt said, because the city's political influence in the state was a reflection of the newspaper's reach beyond its immediate market.17

There is a tendency among editorial-side people to blame these developments on the conversion of privately held companies to public trading. But more is going on than that. In 1984, Stanley Wearden and I compared the attitudes of newspaper managers (editors and publishers) with those of investment analysts about the relative importance of financial performance and journalistic quality. We expected managers in public newspaper companies to agree with the analysts more than would the managers of nonpublic companies. We were wrong. At that time, managers in public and private companies held identical attitudes.

“King Kong with a Quotron”

A more important development, noted by Harvard's Rakesh Khurana, has been the gradual dispersion of ownership in corporate American in general—not just among media companies—from family and friends of the founders to institutional investors. In 1950, Khurana reported, less than 10 percent of corporate equities in the USA were owned by institutions such as pension funds and mutual funds. By the turn of the century, institutions controlled about 60 percent.

Some institutional investors, like Warren Buffet of Omaha, are long-term oriented. They call themselves “value investors” and think in terms of five years or even longer. But many, in the words of law professor Lawrence E. Mitchell, are like “King Kong with a Quotron.” The typical money manager “is paid on the basis of how much money he makes for the fund in the short run, a fact which focuses his attention on the short-term performance of his portfolio corporations.”18 Like the Dodge brothers attacking Henry Ford, these kinds of institutional investors wanted faster payout from their holdings, and they were getting aggressive about it by the 1980s. They promoted hostile takeovers and pressured directors to be more responsive to short-term interests of shareholders.19

An even broader view was taken by Jane Cote of Washington State University-Vancouver, who saw investor pressure eroding professionalism in a variety of fields regardless of their business structure.20 Doctors who sold their practices to corporations risked losing control of their ability to maintain professional responsibility, whether the corporations were public or private. The corruption of the professional values of accounting firms, made highly visible by Enron and related scandals in 2002, showed that a company didn't have to be a corporation at all to be affected. Accounting firms are partnerships, not corporations. The erosion of professional values might be a useful frame for examining what is happening to newspaper journalism.

But the most interesting frame is the influence model. If the influence model is valid, then newspaper companies that yield to investor pressure to convert the influence increment into cash have either decided to harvest their market position and get out, or they are taking a terrible risk. They are trying to harvest enough of their market position to provide the capital to move into new forms of media without making any new investment. But new enterprises do require investment. The best way to ensure the future of newspapers would have been to conserve their influence and pay the costs of the radical experimentation needed to learn what new media forms will be viable.

These still developing media forms are the real competitors, and market share is an issue again. It is a more complicated market because the good being sought is neither share of circulation nor share of readership. It is share of the audience's finite amount of attention. Like Henry Ford, media entrepreneurs, including newspaper companies, should be more interested in capturing the relevant share rather than in maximizing short-term profitability.

How can we test the reality of the influence model? A crude first step would be to find a measure of something that relates to newspaper influence to see if it changes over time along with readership. The General Social Survey offers trend data on both readership and confidence in the press. First, let's look at confidence:

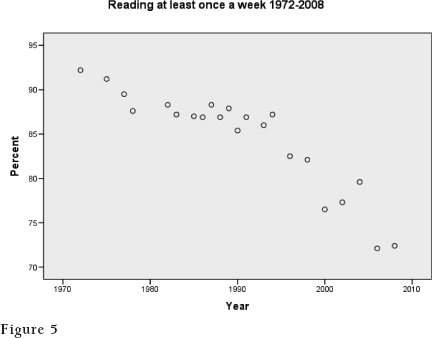

As you can see, the decline shows signs of leveling off after a sharp drop between 1991 and 1993. Now let's see what happened to the daily newspaper reading habit in that same period.

This is a steeper line, and there is less year-to-year variation around it. The regression slope is about 0.94 percentage points per year. Try extending that line with a straight edge, and it shows us running out of daily readers in March 2044.21 But please don't take that observation as a prediction. Straight-line trends do not continue indefinitely. Nature likes to throw us curves. Publishers might be stubborn, but they will not relentlessly continue to churn out papers until one last weary reader recycles the last crumpled copy. Red ink would stop them long before that.

The fact that both confidence and readership are declining in the same period and at close to the same rate does not mean that one is the cause of the other. Time is one of those variables that Harvard Professor James A. Davis calls “fertile” because they produce lots of different things.22 When we take out the effect of time (with a partial correlation of readership and confidence, controlling for year) we are left with a very low and not-at-all significant correlation.23

The true source of the readership decline can easily be seen in the next graph. For years, marketers have been acting like it is a big mystery. Instead, the basic problem is quite simple. It is a matter of generational replacement. Since the baby boomers came of age, we have known that younger people read newspapers less than older people. For years, we comforted ourselves with the thought that they would become like us and adopt the newspaper habit as they got older.24 It never happened. In Figure 4, each line is a generation. The lines are roughly parallel (allowing for some kinks due to sampling error). As the years go by, each generation keeps roughly the reading habit that it had established by the time it reached voting age. (Although you can see the aging World War II generation start to falter in 2002. Its youngest members were then 74.)

Let your gaze linger on the above chart so the message sinks in. Here it is in plain words: all the readership studies to learn “what readers want” and all the resulting tweaking of content in response, all that activity throughout the final quarter of the twentieth century, didn't matter. The important things that affect readership are happening before the customers are old enough to show up in reader surveys!

Well, almost. We're talking about daily readership here, and you might still make a pretty good business out of a product that readers consult only two or three times a week. Let's go back to the General Social Survey and see what happens when we chart the percentage of adults who read a newspaper once a week or more.

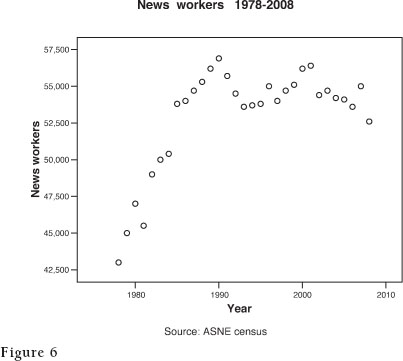

Here we can see something that is not so obvious in the daily reader chart. Newspaper readership flattened out in the 1980s! What happened?

You probably had to be there to understand, but we veterans can remember. Newspaper owners were scared. They saw readership trending downward. They knew that circulation growth was less than household growth—meaning declining penetration. What did they do about it? They tried to make their newspapers better.

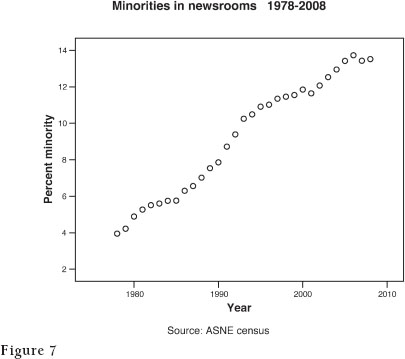

The American Society of Newspaper Editors has been taking a census of newsrooms since 1978. This action was initiated in response to the civil rights movement and a belief that newspapers could better serve their communities if the demography of the newspaper staff reflected the demography of the community. So ASNE set a formal goal: make the minority proportion in the newsroom equal the minority makeup of the community it serves by the year 2000. A byproduct of that effort was a useful year-to-year comparison of newsroom staff sizes.

You can see what happened: a steep climb in human resources in the newsroom throughout the decade of the 1980s. It corresponds closely to the leveling off in the decline of newspaper readership seen in the previous chart. And then, after 1990, the pattern shifted, and newsrooms started to get smaller. The good news is that minority representation climbed fairly steadily, averaging about a third of a point per year. However, minority representation in the population was increasing at just about the same rate.

The net effect of these two variables, newsroom population and minority representation, can be estimated with regression analysis. Francesca Carpentier built a model using year-to-year changes in both variables. They were positively correlated with the percent of all adults reading at least weekly, minorities reading at least weekly, and the percent expressing confidence in the press. The growth in minority staffing proved to be the strongest predictor. It was significantly correlated with overall reading and strongly and significantly correlated with minority readership.25 In other words, without the ASNE effort, the newspaper industry's situation would have been much worse.

It is possible to get an intuitive feel for the effects that we have estimated by looking at a regression equation expressed as a declarative sentence:

The passage of each year accounts for a readership decline of 1.4 percentage points, but this is partially offset by an increase of about half a percentage point for each 1,000 workers added to the nation's newsrooms and another 2.2 percentage points for each one-point increase in minority representation. During the golden 1980s, newsroom staffing actually did increase by about a thousand workers per year. Minority representation grew by about a third of a point a year.

We can only guess how much readership might have been preserved if the improvements of the 1980s had been sustained. Regression is pretty good at estimating effects in the past, not so good at estimating the future because the straight-line trends on which it relies do not run indefinitely. Eventually, the law of diminishing returns forces the lines to bend.

Where they would bend in this case, we'll never know, because publishers lost heart in the 1990s and tried too hard to preserve their historic operating margins in the face of increasing competition from the Internet for both news and advertising. Craig Newmark founded his Craigslist classified advertising service in 1995 and started expanding beyond the San Francisco Bay area in 2000. The service is mostly free, but it gets revenue from selected business applications.

Other entrepreneurs, perhaps inspired by Newmark's example, found more business applications, and online advertising grew from a $300 million industry in 1996 to $16.7 billion in 2006.26 Newspapers tried to compete with online ads of their own, but the upstart competitors had lower costs and tighter focus on customer service.

Thus ended the Golden Age. Bob Ingle, who was editor of the San Jose Mercury in that period, remembers it fondly as “the entire decade of the 1980s, maybe a wee tad into the 1990s. Because all lines of revenue were strong— or at least if one line was weak, the others were more than making up for it. At the Merc, we were hiring people as fast as we could interview them. Also, strong linage meant big newshole.”27

When newspaper owners started withdrawing resources from the newsroom, the predictable effect was a weakening of their influence in their communities. What we really want to know in looking back is whether the decline in influence was the key element in their downward spiral. If influence is important, it needs to be taken into account when media businesses do their strategic planning.

Measuring Influence

To find out, we need a way to evaluate, at the community level, the public sphere and the newspaper's role in creating it. There might be some happy combination of individual and community attributes that makes the influence model work. The problem calls for an experimental design that compares newspaper use in communities with different levels of credibility over an extended period of time. No such data set exists. However, historical data are available for newspaper circulation and household penetration. And the Knight Foundation has archived a twenty-six community survey—with replication after three years—that includes a question addressing newspaper believability. If we can accept credibility, measured by a single survey question on believability, as an indicator of newspaper influence, then we can at least make a start.

Editors have been worrying about the credibility issue for years. The most alarming report on the topic came in 1985 from Kristin McGrath of MORI Research with a little nudging by David Lawrence who, on behalf of the American Society of Newspaper Editors, hired her firm to do a national survey. “Three-fourths of all adults have some problem with the credibility of the media,” she wrote, “and they question newspapers just as much as they question television.”28

A contrasting report was issued early the following year by the Times Mirror newspaper after it hired The Gallup Organization to cover the same territory.

“If credibility means believability, there is no credibility crisis,” said this report, written by Andrew Kohut and Michael Robinson. “The vast majority of the citizenry thinks the major news organizations are believable.”29

Oddly, the data collected by the two organizations were not very different. Their different interpretations reflected a half-full v. half-empty attitude difference rather than a data contrast.30

Another contribution to the conversation came in 1998 when Christine Urban, also working for ASNE, produced another report. Hers made no reference to the earlier work, but it did propose six major sources of low trust. Number one on the list: “The public and the press agree that there are too many factual errors and spelling or grammatical mistakes in newspapers.”31

Two purely descriptive studies were published in 2001. News credibility was one of a very broad array of social indicators asked about in 1999 by the Knight Foundation which found that 67 percent believe “almost all or most” of what their local daily newspaper tells them.32 A similar result was published at the same time by American Journalism Review, based on field work in 2000 funded by the Ford Foundation. This study reported that 65 percent believe all or most of what they read in the local paper.33

Designers of none of these studies made any effort to attain compatibility with previous work so that comparisons could be made over time.

Nor were any of the studies informed by any kind of theory that might help us understand how much credibility a newspaper needs, how much it costs to get it, and whether the cost is worth it. As careful and detailed as they were, these reports generated little but description “waiting for a theory or a fire.”34

The model's appeal is that it provides a business rationale for social responsibility. The way to achieve societal influence is to obtain public trust by becoming a reliable and high-quality information provider, which frequently involves investments of resources in news production and editorial output. The resulting higher quality earns more public trust in the newspaper and, not only larger readership and circulation, but influence with which advertisers will want their names associated.

Because trust is a scarce good, it could be a natural monopoly. Once a consumer finds a trusted supplier, there is an incentive to stay with that supplier rather than pay the cost in time and effort of evaluating a substitute. I've been going to the same barbershop for twenty-five years for that reason.

The theory we hope to test, then, is that the societal influence of a newspaper achieved from practicing quality journalism could be a prerequisite for financial success. Over the long term, social responsibility in the democratic system would support, rather than impede, the fulfillment of a newspaper's business objectives, through the channels of obtaining public trust and achieving societal influence, which then feeds back into further fulfillment of the public mission, thereby creating a virtuous cycle (see Figure 8).35

Reversing the argument, cutbacks in content quality will, in time, erode public trust, weaken societal influence, and eventually destabilize circulation and advertising. So why would anyone want to cut quality? If management's policy is to deliberately harvest a company's market position, it makes sense. And pressure from owners and investors might even lead managers to do it without thinking very much about it because reducing quality has a quick effect on revenue that is instantly visible while the costs of lost quality are distant and uncertain. When management is myopically focused on short-term performance indicators such as quarterly or annual earnings, the harvesting strategy is understandable.

If those distant costs could be made more concrete and predictable, managers and investors might make different decisions. This is a natural agenda for journalism researchers: to reduce the uncertainty about the long-term cost of low credibility, using individual communities and their newspapers as the level of analysis.

Testing the Model

The first test of the model is very simple: find a correlation between credibility and profitability. After that, it gets difficult. Correlation does not prove causation, so we'll have to treat this as a puzzle and include a dose of common sense in the solution.

For starters, we need to be able to measure both credibility and profitability at the level of individual newspapers. Fortunately, the Knight Foundation data are available.

The Knight Foundation keeps track of the twenty-six communities where John S. and James L. Knight operated newspapers in their lifetimes.36 (The ownership of the newspapers in these communities is widely scattered due to various sales, including the break-up of Knight Ridder in 2006. While the company bought and sold newspapers, the Foundation's list remained constant.) The communities watched over by the foundation range from large (Philadelphia and Detroit) to very small (Milledgeville, Ga., and Boca Raton, Fla.). One of the questions in the 1999 and 2002 surveys asks this about the communities' general trust in newspapers as a media category:

“Please rate how much you think you can believe each of the following news organizations I describe. First, the local daily newspaper you are most familiar with: would you say you believe almost all of what it says, most of what it says, only some, or almost nothing of what it says.”

It is a crude measure compared to Gaziano and McGrath's multi-item measure for ASNE in 1985. Its value comes from its consistent use, which allows comparisons across different markets and at two points in time.37

Profit data is hard to get, so we'll use a special measure of circulation as a stand-in. One good thing about it is that circulation is fairly stable, while profit depends on fluctuations in the business cycle. To adjust for different market sizes, let's use circulation divided by the number of households. Newspaper marketers call this number “market penetration.” That leaves yet another problem, how to define the market.

Newspapers vary wildly in their self-definition of markets. Sometimes, their definitions change, as in the Des Moines case. While maximizing circulation is not always the business goal, I know of no important newspaper that is ambivalent about circulation in its home county. Therefore, it makes sense to take home county penetration as our uniform indicator of business success.

One more step is needed to put matters on an apples-to-apples basis. Some markets have chronically low penetration due to local circumstances. We can adjust for such built-in differences by making change over time the key indicator. Each market defines its own baseline, and business success is measured by the ability to improve on that base—or minimize the decline—from some reference point in time. The result is a fair comparison of audience response to changing circumstances across wildly different markets.

Such a definition deserves a name. I call it “penetration robustness,” and I calculate it from the 1995, 2000 and 2003 county penetration reports of the Audit Bureau of Circulations (ABC). Penetration declined almost everywhere. But it makes sense to call it robust when its value at Time 2 is a relatively high proportion of its value at Time 1.38

So much for theory. Now to some practical obstacles. Use of ABC's county penetration report made it necessary to eliminate two Knight communities where the 1999 survey geography was not defined by counties.39 A third, Milledgeville, had to go because its newspaper was not an ABC member.

That leaves a sample of twenty-three markets. In south Florida, the sample size was great enough to allow separation of Dade and Broward counties so that they could be treated as separate communities. Now we have twenty-four.

Most of these communities have dominant newspapers that were, at some time in the past, owned by Knight Ridder. Palm Beach and Broward counties in Florida are exceptions. In the former, the dominant paper is Cox's The Palm Beach Post. In the latter, it is Tribune Co.'s South Florida Sun-Sentinel. Several counties have more than one strong newspaper. Because we are more interested in a test of influence theory than in the fate of individual newspapers, having multiple cases in a county can actually help reduce error. We'll use county-level aggregates for both robustness and credibility in the hunt for a correlation.

Here's another practical obstacle: the single-question credibility measure in the Knight Foundation survey is unstable. There was considerable shifting among the counties. The correlation between the 1999 and 2002 measures was significant but lower than we would like.40 Sedgwick County, Kan., gained seven points, while Grand Forks, N.D., lost six. Transient local controversies or major news events might have had something to do with these shifts.41

Accordingly, it seems prudent not to base the credibility measure on a single measure but to average the 1999 and 2002 survey findings. This yields a range from 15 percent trusting their “most familiar” newspaper among the six circulating in Boulder County, Colo., to 27 percent among readers of the three dailies sold in Brown County, S.D.42 It also yields a credibility distribution with no outliers.43

Alas, the same cannot be said for the circulation data. There were three outliers or extreme cases in the 1995-2000 period.44 Examining each of them in turn, I found local factors affecting circulation that would overwhelm any more subtle effects that we might seek:

•Dade County, Fla.—The county's explosive circulation boom was the result of an artifact, the unbundling of El Nuevo Herald from its mother ship, The Miami Herald. Before the separation, ABC folded circulation of the Spanish language edition into the Herald's total. After the split, Herald circulation went down, but counting El Nuevo separately made total circulation rise sharply. There was no way to correct for this to make a before-after comparison, and Dade County was dropped from the sample.45

•Boulder County, Colo.—In the months before the creation of the joint agency by the owners of The Denver Post and the Denver Rocky Mountain News in 2000, the two Denver newspapers were engaged in a bitter circulation war that saw the price of a newspaper drop to a penny per copy. This battle extended into neighboring Boulder County. While it cost the local paper circulation, total newspaper circulation in the county soared. Boulder County was dropped.46

•Wayne County, Mich.—Detroit, always a strong labor town, underwent a bitter newspaper strike that began in 1995 and led to many union members losing their jobs. In a display of sympathy and solidarity, enough working people in the home county stopped buying the paper to cause a catastrophic circulation decline. Wayne County was removed from the sample.

That leaves twenty-one communities without obvious unusual circumstances to mask the effect of credibility on circulation.

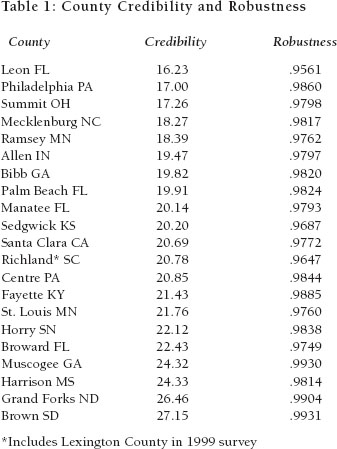

Just for reassurance that we are grounded in the real world, here is the list of twenty-one counties with their credibility scores and average annual robustness for the period 1995–2000. Please remember that these are aggregate scores for all the newspapers in the county. Credibility comes from the survey question about the newspaper read most often, and robustness comes from ABC data for all audited newspapers in the county. They are listed in ascending order of their credibility.

The plot in Figure 8 shows that credibility and penetration robustness are strongly related. As one rises, so does the other. Their relationship is quite unlikely to be due to chance. The credibility of the newspapers in these communities explains 31 percent of the variation in the robustness of their combined daily penetration. In other words, if you tell me the credibility of the newspapers in any given county, I can estimate their combined robustness with 31 percent greater accuracy than if I just used the 21-county average to inform my guess.

Each little square in the plot is a county, and I have identified some as space permits.47 As credibility increases from left to right, robustness rises from bottom to top.

The slope of a straight line defining that relationship is .2, meaning that annual circulation robustness—the ability of a county's newspapers to hold their collective circulation in the face of all of the pressures trying to degrade it— increases on average by two-tenths of a percentage point for each 1 percent increase in credibility. However, there is a problem. Just by inspecting the list, one can see that credibility tends to be greater in the smaller markets. Keith Stamm, the University of Washington professor who investigated the effect of community ties on newspaper use, prepared us for the possibility that those ties might weaken as cities grow.48 Distrust of local newspapers could be a function of weaker community ties.

The size effect is not linear because it diminishes as counties get larger. For counties larger than 400,000 households, there is no size effect at all. One way to deal with a curvilinear effect like this one is to re-express market size as its logarithm. The correlation between the log of households (which takes the curve into account) and credibility is negative, significant, and powerful.49 An effect this basic needs to be noted so that we can take it into account when we look at other aspects of newspaper quality. We should start to suspect that large and small markets are qualitatively different from one another.

Looking for Causes

Now for the hard part: showing the path of causation behind these interesting connections. We have three nicely linked variables: market size, credibility and robustness. Which are causes and which are effects? While this might look like a statistical problem, it's really more of a logic issue. The most important logical rule is that tomorrow's events can't cause today's.50 A related principle is that events closest to one another in a causal sequence will have the highest correlations. The other common-sense rule is to identify what Jim Davis calls “fertile variables” and “sticky variables.” The sticky variables are those that do not change easily, if they change at all. One's year of birth is an example. Such variables are more likely to be causes than effects. Fertile variables are those that affect everything they touch—social class, for example. This characteristic makes us look to them first when seeking causes.

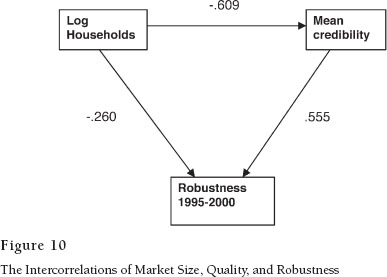

In this case, market size is both sticky—it does not change quickly—and fertile—it has lots of effects. So there is plenty of reason to think of it is as a first cause in this simple model. To help understand the situation, here's another picture. The numbers show the correlation coefficients while the direction of the arrows gives our best guess at the direction of causation.

What this picture says is that market size causes credibility (the sign is negative, so smaller communities tend to be more trusting), and credibility causes robustness. There appears to be a smaller, direct effect of market size on robustness. Or is there? It might be that the small correlation of -.260 is just an artifact of the reduced credibility in larger markets.

There is a statistical way to help us decide. It is called partial correlation. It tells us what the correlation between market size and robustness would be if all the markets had the same credibility. If you like sports metaphors, you can call this “leveling the playing field.” If you want to sound like a statistician, you say you are “controlling for credibility.”

When market size (log of households) is controlled, the correlation between credibility and robustness remains positive and significant. That gives us confidence that credibility, in and of itself, improves circulation robustness.

But when credibility is controlled, the link between size and robustness virtually disappears. This leads us to believe that size itself doesn't matter except as it affects credibility. The path is straightforward: smallness in size contributes to credibility which in turn aids robustness. The direct effect of size is nil.

This result is consistent with Maisel's thesis that media aimed at smaller audiences do better, and it hints that credibility achieved by narrower targeting is the reason. It is also very good news for editors. They can't do much about the size of their home counties, but they can at least try to imagine ways to manage a larger newspaper that would yield some of the effects of a smaller community. Zoning is one obvious way. Encouraging citizen participation in the affairs of the larger community, a goal of the civic journalism movement, is another. Or they can imagine other specialties.

What we have here is evidence in support of one link in the model in Figure 3. It is weak evidence, limited as it is to twenty-one markets and one five-year time period. When the data are used to predict robustness from 2000 to 2003, nothing happens. Perhaps it takes longer than three years for the effect of trust to accumulate to the point of being measurable. However, this is not true of all effects, as we'll see in Chapter 5.

This case illustrates the difficulty of demonstrating, in a way that will be appealing to investors, the relationship between quality journalism and profitability. Hal Jurgensmeyer's influence model deserves further investigation, but several things are needed:

1. Bigger samples and longer time periods. Teasing out the direction and degree of causation requires looking at more points in time so that effects can be separated from ongoing secular trends. It also needs a more varied sample. Because of their history, the communities tracked by the Knight Foundation tend to have better than average newspapers. With more variance in newspaper quality, we might see stronger effects.

2. A more stable measure of influence. The 1985 ASNE study provided evidence that a newspaper's perceived ties to its community are a factor in its credibility, and by implication, its influence. That lead should be pursued. The concept is too important to rely on a single survey question.

3. Recognition that small and large papers operate in environments so different that they probably need to follow different rules. Other research has shown that circulation volatility is much greater among smaller newspapers.51 If the rules are different, somebody needs to discover and codify them.

4. Identification of the “sweet spot” and a means of determining where a given newspaper stands in relation to it.

The last one requires some explanation. The concept of the sweet spot has been used by Jack Fuller to define an optimal compromise between demands of profitability and public service. My definition is a little different. It assumes that quality brings in more dollar return than it costs—up to a point. It is vital for a manager—or an investor—to know whether that point is approached, reached, or exceeded. Imagine a bell-shaped curve with profit measured along its horizontal dimension. Here is a picture of such a curve.

Quality is measured on the horizontal. As it increases, so does profit— slowly at first, then, as critical mass is reached, with accelerating effect. Then the curve rounds off at the top and begins to descend. This is the law of diminishing returns. Since it's a natural law, there's probably not much we can do about it. But we can try to determine when and how the diminution of return sets in.

This goal is much harder than it sounds because the effect of quality takes some time to kick in. The initial effect is cost. The monetary return comes later, after the newspaper's influence accumulates. The good news is that there is a similar lag when quality is degraded. Readers and advertisers alike keep using the product out of habit long after the original reasons for doing so are forgotten.

A newspaper is in danger when its owners assume that it has passed the sweet spot and is on the downhill side of the curve. If they have really passed the point of diminishing return, they would be right to cut quality and get back to a level that makes economic sense. But what if they are in fact on the uphill side? In that case, the quality cuts will drag them backward down the slope to eventual destruction.

Since the dawn of the electronic era in the 1920s, newspapers have minimized their decline by adapting to a long string of new technologies that disrupted their then existing business models: radio, television, high-quality printing for direct-mail advertising and highly specialized print media. Of the six classic strategies enumerated by Michel Porter for dealing with competitive new technology, four clearly apply to newspapers.52

1. Enlist suppliers to help in defense. Newsprint suppliers were major funders of the newspaper industry's experiments with market research in the 1960s and 1970s. United Press International, a supplier of news, chipped in even when it was in serious financial trouble itself.53

2. Redirect strategy toward segments that are least vulnerable to substitution. When television captured national image advertising, newspapers concentrated more on detailed price and product advertising for local retailers. After direct-mail innovators put advertising messages on slick paper and in color, newspapers responded with preprints and total market coverage (TMC) products.

3. Enter the substitute industry. Before the FCC limited cross ownership, some newspaper companies were quick to acquire and apply their brand name to radio and TV stations. Now they are responding to the Internet threat by creating online versions of themselves.

4. Harvest market position. This is the “take-the-money-and-run” plan. Because newspaper customers are such creatures of habit, it could be quite seductive. It means raising prices, reducing quality, and taking as much money out of the firm as possible before it collapses.

I know of no newspaper company that is totally committed to the fourth strategy. But on some days, at some companies, there are very strong indications that they are drifting in that direction, egged on by short-sighted investors. Documentation and detailed specification of the Jurgensmeyer influence model might help the industry avoid this fate.

Or it might not. Even if nothing can save newspapers from the leaders that William Allen White feared, the ones with acquisitive faces, the influence model could motivate the creators of the newer forms of media to find a way to keep social responsibility in their business plans. It deserves our highest priority. We should have started sooner.

1. Louis M. Lyons, Reporting the News (Cambridge, Mass.: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1965), 255.

2. Donald L. Shaw, “The Rise and Fall of Mass Media,” Roy W. Howard Public Lecture, School of Journalism, Indiana University, April 4, 1991.

3. This number is derived from circulation reported by the Newspaper Association of America at http://www.naa.org/ and household projections reported by the U.S. Census. Average daily circulation is counted by the formula (6*D + S)/7 where D = average weekday circulation and S = average Sunday circulation.

4. James Madison, Letter to W. T. Barry, August 4, 1822, in Saul K. Padover, ed., The Complete Madison (Millwood, N.Y.: Kraus Reprint Co., 1953).

5. Merrill and Lowenstein, Media, Message, and Man (New York: David McKay, 1971).

6. Republished in Edward C. Bursk and John F. Chapman, eds., Modern Marketing Strategy (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1964). Levitt's retrospective commentary appeared in Harvard Business Review 53 (September–October 1975). Available at http://bold.coba.unr.edu/769/Week6/MarketingMyopia.pdf (retrieved June 29, 2003).

7. Personal conversation, Chapel Hill, N.C., March 22, 2002.

8. We all lose weight while we sleep, through evaporation, respiration, and elimination.

9. Simon, “Designing Organizations for an Information-Rich World,” in Martin Green-burger, ed., Computers, Communications, and the Public Interest (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1971).

10. Lasswell, “The structure and function of communication in society,” in L. Bryon, ed., The Communication of Ideas: A Series of Addresses (New York: Harper, 1948), 37–51.

11. Michael E. Porter, Competitive Strategy: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance (New York: Free Press, 1998), 311.

12. Carol Gelderman, Henry Ford: the Wayward Capitalist (New York: Dial Press, 1981), 84. Ironically, Ford Motor Co. was far less successful when Ford was sole owner. After Ford bought out the minority shareholders in 1919, he began losing market share to General Motors and Chrysler.

13. For an excellent development of this idea, see John M. Hood, The Heroic Enterprise: Business and the Common Good (New York: The Free Press, 1996).

14. Gelderman, Henry Ford, 85.

15. Richard Maisel, “The Decline of Mass Media,” Public Opinion Quarterly 73:159 (1973).

16. Edwards, panel discussion, “Are the Demands of Wall Street Trumping the Needs of Main Street?” AEJMC Media Management and Economics Division, Miami Beach, Fla., Aug. 8, 2002.

17. Merritt, remarks to Seminar in Media Analysis, School of Journalism and Mass Communication, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, N.C., April 22, 2002.

18. Mitchell, Corporate Irresponsibility: America's Newest Export (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001), 170. An analysis by Rick Edmonds indicated that newspaper companies had a disproportionate number of value investors. See “Who Owns Public Newspaper Companies and What Do They Want?” Poynter Online, www.poynter.org, Dec. 11, 2002 (retrieved Dec. 10, 2003).

19. Rakesh Khurana, Searching for a Corporate Savior: The Irrational Quest for Charismatic CEOs (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2002).

20. Seminar in Media Analysis, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, N.C., March 20, 2002.

21. This plot has a data point for 1967 when NORC asked the newspaper readership question for the Nie-Verba “Participation in America” survey and 73 percent reported reading a newspaper every day. The General Social Survey was started in 1972.

22. Davis, The Logic of Causal Order (Newbury Park, Calif.: Sage Publications, 1985).

23. R = .164, p = .544.

24. For example, Heidi Dawley of Media Life Magazine, quoting Dr. Leo Kivijarav, then director of research and publication for Veronis Suhler Stevenson, the investment banking firm: “Kivijarv believes that as people get older they take on the habits of older people. So as the young folks today who spurn newspapers get older, they will become newspaper readers.” Media Life Magazine, “Dispelling myths about newspaper declines,” June 4, 2003. www.medialifemagazine.com/news/2003 (retrieved Dec. 10, 2003).

25. R = .67, p < .01. Unpublished paper, Francesca Carpentier, Philip Meyer and C. Temple Northrup, “Harvesting Market Position or Planting for the Future?: The Influence of Workforce Investment on Newspaper Readership,” paper prepared for International Communication Association, Chicago, 2009.

26. Data are from Pricewaterhouse Coopers LLP as posted by the Pew Research Center's Project for Excellence in Journalism at http://journalism.org/node/6667 in 2007.

27. Bob Ingle, e-mail, Oct. 9, 2008.

28. Newspaper Credibility: Building Reader Trust, a National Study Commissioned by the American Society of Newspaper Editors (Minneapolis: MORI Research, Inc., April 1985).

29. The People & the Press: A “Times Mirror” Investigation of Public Attitudes Toward the News Media Conducted by The Gallup Organization (Washington, D.C.: Times Mirror, January 1986).

30. Philip Meyer, “There's Encouraging News About Newspapers' Credibility, and It's in a Surprising Location,” presstime (June 1985).

31. Urban, Examining Our Credibility: Perspectives of the Public and the Press. (American Society of Newspaper Editors, 1989), 5.

32. Listening and Learning: Community Indicator Profiles of the Knight Foundation Communities and the Nation, (Miami: Knight Foundation, 2001).

33. Carl Sessions Stepp, “Positive Reviews,” American Journalism Review (March 2001).

34. This phenomenon is not confined to media businesses. Ronald Coase, in a critique of early institutional studies in business administration, said, “Without a theory they had nothing to pass on except a mass of descriptive material waiting for a theory or a fire.” Quoted by Oliver E. Williamson in Giovanni Dosi, David J. Teece and Josef Chytryl, eds., Technology, Organization and Competitiveness: Perspectives on Industrial and Corporate Change (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998).

35. This is the model proposed in Philip Meyer and Yuan Zhan, “Anatomy of a Death Spiral: Newspapers and their Credibility,” Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication, Miami Beach, Fla., Aug. 10, 2002.

36. The John S. and James L. Knight Foundation promotes excellence in journalism worldwide and invests in the vitality of twenty-six U.S. communities where the communications company founded by the Knight brothers published newspapers. The Foundation is wholly separate from and independent of those newspapers.

37. Listening and Learning.

38. Such a measure is complicated by the variance in the lag time between an ABC audit and publication of the result in the reports. Each report presents results of the most recent audit, which can be anywhere from a few months to more than a year before the date of the report. To correct for this, I used the number of days elapsed between audits to calculate an annualized robustness. It can be conceptualized as the proportion of home county penetration retained in an average year during the study period. To summarize: Penetration = circulation/households. Robustness = Penetration at Time 2/Penetration at Time 1. Annualized Robustness = 1-(1-R)/A where R = Robustness for the period and A = elapsed time in years between ABC audits.

39. Long Beach, California, and Gary, Indiana.

40. r = .457, p = .022. Despite individual shifts, the twenty-five Knight counties were stable as a group. The percent who believed their newspaper all or most of the time averaged 20.4 percent in 1999 and 20.7 percent in 2002.

41. The Grand Forks Herald, for example, had come under intense local criticism for editorially supporting native Americans' efforts to persuade the University of North Dakota to change its athletic nickname, “The Fighting Sioux.” Or its trust might have suffered some statistical regression after the paper's extraordinary effort in its Pulitzer-winning coverage of the 1997 flood on the Red River of the North.

42. The six papers circulating in Boulder County in 2000 were the Daily Camera, The Denver Post, Denver Rocky Mountain News, Fort Collins Coloradan, Daily Times-Call and USA TODAY. In Brown County, the three were Aberdeen American-News, USA TODAY, and Star Tribune (Newspaper of the Twin Cities).

43. Using the Tukey boxplot, the outliers were Brown County in 2002 and Leon County, Fl., and Grand Forks, N.D., in 1999.

44. All four met Tukey's definition of outliers and extreme values as cases that are more than 1.5 times the interquartile range from the upper and lower edges of that range. See John W. Tukey, Exploratory Data Analysis (Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley, 1977).

45. I appreciate the help of Armando Boniche, research manager of The Miami Herald, in sharing this history.

46. Barrie Hartman, former executive editor of the Boulder Daily Camera, provided this background.

47. R = .555, p = .009.

48. Keith Stamm, Newspaper Use and Community Ties: Toward A Dynamic Theory (Norwood, N.J.: Ablex, 1985). He reports contrasting arguments on pp. 178–79.

49. For log households and credibility, r = -.609, p = .003.

50. Or, as James A. Davis has put it, “After cannot cause before.” Davis, The Logic of Causal Order (Beverly Hills: Sage Publications, 1985), 11.

51. Philip Meyer and Minjeong Kim, “Above-Average Staff Size Helps Newspapers Retain Circulation,” Newspaper Research Journal 24:3 (Summer 2003), 76–82.

52. The six possible strategies are listed by Porter in his chapter on substitution (Chapter 8) in Competitive Advantage. Two lack an obvious application to newspapers. One of these is finding new uses unaffected by the substitute, like the use of baking soda as a refrigerator deodorant, an application that now exceeds the product's use for baking. The other is to compete in areas where the substitute is weakest. For newspapers, applications requiring the portability of the printed product might have some promise.

53. These efforts are chronicled by Leo Bogart in Preserving the Press (New York: Columbia University Press, 1991).