Chapter 2

How Newspapers Made Money

I learn'd to love despair

—Byron, “The Prisoner of Chillon,” 1816.

To appreciate how the locale for Byron's poem serves as a metaphor for the American newspaper industry, drive a short distance north of Montreaux, Switzerland, and visit the Rock of Chillon. It sits on the eastern edge of Lake Geneva, and it was fortified in the ninth century. In the twelfth century, the counts of Savoy built a castle on the rock. With the lake on the west side and a mountain on the east, the castle commands the north-south road between. Any traveler on that road had to choose between paying a toll to the owner of the castle, climbing the mountain or swimming the lake. It was such a sweet deal that the lords of Savoy and their heirs clung to that rock for three centuries.

For generations, U.S. newspaper publishers were like the Savoy family. Their monopoly newspapers were tollgates through which information passed between the local retailers and their customers. For most of the twentieth century, that bottleneck was virtually absolute. Owning the newspaper was like having the power to levy a sales tax.

But new technology bypassed the bottleneck. Just as today's travelers can fly over Chillon or pass it in a power boat or on an alternate road, today's retailers are finding other ways to get their messages out. Newspapers have been slow to adapt, because their culture is the victim of that history of easy money. For perspective, consider the following comparison: In most lines of business there is a relationship between the size of the profit margin—the proportion of revenue that trickles to the bottom line—and the speed of product turnover. Sell a lot of items, and you can get by with just a little profit on each one. If sales are few, you'd better make a bundle every time.

Supermarkets can prosper with a margin of 1 to 2 percent because their buyers consume the products continually and have to keep coming back. Sellers of diamonds or yachts or luxury sedans build much higher margins into their prices to compensate for less frequent sales. Across the whole range of retail products, the average profit margin is in the neighborhood of 6 to 7 percent.1

In turnover, daily newspapers are more like supermarkets than yacht dealers. Their product has a one-day shelf life. Consumers and advertisers alike have to pay for a new version every day if they want to stay current. Absent a monopoly, newspaper margins would be at the low end. But because they owned the bottleneck, the opposite was true. Before technology began to create alternate toll routes, a monopoly newspaper in a medium-size market could command a margin of 20 to 40 percent. As recently as 2007, the average was still close to 25 percent.

That easy-money culture has led to some bad habits. If the money comes in no matter what kind of product you turn out, you become production oriented instead of customer oriented. You are motivated to get it out the gate as cheaply as possible. If your market position is strong, you can cheapen the product and raise prices at the same time. Innovation happens, but it is often directed at making the product cheaper instead of making it better.

Before newspapers were controlled by publicly held companies, their finances were secret. A few retailers may have noticed that a publisher's family took flying vacations to Europe while they drove theirs to the local mountains or the beach, but publishers were usually careful not to flaunt their wealth. It is unwise to arouse resentment from one's own clientele.

When newspaper companies began going public in the late 1960s, the books opened, and Wall Street was delighted with what it saw. Analyst Patrick O'Donnell, in an industry review prepared for E. F. Hutton clients in 1982, ticked off the advantages enjoyed by newspapers:

•Competition in selling was increasing the size of the advertising market, and newspapers had consistently received 28–30 percent of total advertising dollars in the previous two decades.

•Newspapers were practically immune from the profit-eroding effects of inflation because they could “pass cost pressures along through prices very efficiently.”

•With their strong cash flows, newspaper companies could finance growth with their own money and avoid the uncertainties of fluctuating interest rates.2

Looking at the previous decade, O'Donnell noted with satisfaction that “aggressive pricing met little resistance, especially in one-newspaper markets where retailers have few other means of access to their customers.” (Note his use of the word aggressive to describe increasing prices. In other industries discussed in business literature, aggressive pricing is lower pricing. That's because most industries are competitive, and a price cut is aggression against the competition. Newspapers, being mostly monopolies, direct their price aggression against their customers.)

At the same time, newspapers were using technology to bring their costs down. Production costs decreased in the last quarter of the twentieth century as the change to cold type and automated typesetting was completed. Circulation costs diminished as newspapers pulled back their “vanity circulation” in areas not considered important by the advertisers in the newspapers' retail trade zones. Administrative costs went up. And news-editorial costs became more flexible.

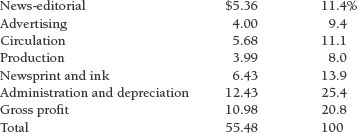

In 2001, a typical newspaper of 100,000 circulation would have an expense breakdown like this (dollar amounts are in millions: percents are of revenue):3

The revenue side was much simpler: Industry-wide, advertising accounted for 82 percent of newspaper revenue in 2000 and circulation was the other 18. That was a shift from a 71–29 division in mid-century. Within the three main categories of advertising—national, retail, and classified—the last grew in relative importance. Here is media economist Robert Picard's analysis of the change between 1950 and 2000:4

That, as Picard suggested, is a whole new business model. And it is a less stable model. Classified advertising, because it includes help-wanted, real estate, and automobile advertising, is especially subject to changes in the business cycle.

Wall Street sees the cyclical nature of the newspaper business as a major drawback. The financial analysts who advise institutional investors make their reputations on their ability to predict the future, so they prefer companies whose growth patterns are steady year in and year out.

The Neuharth Solution

It was Gannett's Al Neuharth who found a solution to this problem. Under his guidance, Gannett accumulated monopoly newspapers in medium-size markets where the threat of competition was remote. Neuharth motivated his publishers to practice earnings management. They held earnings down during the good times by making capital investment, refurbishing the plant, and filling holes in the staff. And they boosted earnings in the bad times by postponing investment, shrinking the news hole, and reducing staff.

Gannett papers played Al's money game vigorously enough to produce a long period of steady quarter-to-quarter growth that satisfied the analysts' lust for predictability. Any long-term costs to these behind-the-scenes contortions did not bother them. Neither, for that matter, did the fact that some of the growth was unreal, because analysts and accountants alike are accustomed to looking at nominal dollar values rather than inflation-adjusted dollars. Neuharth's glory days were also a period of high inflation, and that helped to mask some of the cyclical twists and turns.

Gannett's stock price soared. Managers of the other public companies saw what was happening and began to practice earnings management, too. One of the devices was the contingency budget, which was more like a decision tree than a planning tool. An editor is told how much he or she can spend on the news product in a given year provided that revenues remain at a certain level. If revenue falls below expectations, leaner budget plans are triggered at specified points on the downward slope.

Neuharth's showmanship worked just long enough to raise everyone's expectations about the value of newspapers. Today, despite some heroic efforts, not even Gannett can match Neuharth's record of “never a down quarter.” Inflation is no longer high enough to mask the fluctuations in real return. Readers are drifting away. Advertisers are exploring other routes for their messages. In 1946, at the dawn of the age of television, newspapers had 34 percent of the advertising market.5 In the second half of the twentieth century, newspaper share of the overall advertising market fell from almost 30 percent to close to 20 percent.

Picard reminded us that, despite loss of share, newspapers still made more money than ever, primarily because the size of the advertising market grew, even after inflation was taken into account. However, it did not grow as much as gross domestic product. Newspapers, by raising prices and reducing cost, did well, but newspaper advertising as a share of GDP fell from seven-tenths of a percent to half a percent in the half-century.6 Charging more for delivering less is not a strategy that can be carried into the indefinite future. So where will it all end? To envision the future, it helps to think about the readers.

The readership decline was first taken seriously in the late 1960s, when new information sources began to compete successfully for the time of the traditional newspaper reader. Competition spawned by technology began long before talk of the electronic information highway. Cheap computer typesetting and offset printing led to the explosive growth of specialized print products that could target desired audiences for advertisers. Low postal rates combined with cheap printing and computerized mailing lists to spur the growth of direct mail advertising. In short, the owners of the traditional toll road have been in trouble for some time.

Some observers draw a line on the chart of newspaper decline (see Chapter 1), using a straightedge to extend it into the future and foresee the death of newspapers. The reality is likely to be quite different. There is room for newspapers in the non-monopoly environment of the newspaper future. They will not be as profitable, and that is a problem for their owners—whether they are private or public shareholders—but it is not a problem for society.

Imagine an economic environment in which newspapers earn the normal retail margin of 6 or 7 percent of revenues. As long as there are entrepreneurs willing to produce a socially useful product at that margin—and trust me, there will be—society will be served as well as it is now. Perhaps they will not be the same entrepreneurs who are serving us now, and that is not necessarily a concern to customers—except for one problem.

The problem is that there is no easy way to get from a newspaper industry used to 20 to 40 percent margins to one that is content with 6 or 7 percent. The present owners have those margins built into their expected return on investment, which is related to their standard of living.

It is return on investment that keeps supermarket owners content with 2 percent margins. And it is return on investment that makes newspaper owners—whether they be families, sole proprietors, or public shareholders—want to preserve their 20 to 40 percent. All of the money that they have sunk into the industry, whether by buying newspapers or spending on buildings and presses, has been cost-justified on the basis of that fat profit margin.

Look at it this way. If I sell you a goose that lays a golden egg every day, the price you pay me will be based on your expected return on investment (ROI), which needs to beat what the bank would pay on a certificate of deposit, but not by much. In negotiating the price that you are willing to pay me (and at which I am willing to sell), we'll both look for an expected ROI that compares favorably with other possible investments. And the reasonable assumption will be that the goose will continue to produce at the same rate.

Fast forward a bit. Once safe under your roof, the goose drops its production to one golden egg a week. That makes you a major loser.

Now, it's still a pretty good goose. You can resign yourself to the reduced income or you can sell it to a third somebody who will be proud to own and house and feed it. And that new owner can, of course, get the return on investment that you were hoping to receive by simply paying one seventh of the price you paid.

What happened to the rest of the goose's value? I captured it when I sold it to you on the basis of the seven-day production schedule. The third owner is a winner, too, because he gets a fair return on his investment. Society is okay because there are plenty of other sources for golden eggs. The only loser is you.

Avoiding the fate of the second owner of the goose is the central problem facing newspaper owners today. They know they have to adjust to the reduced expectations that technology-driven change has brought them. They just don't know how. To understand the range of possible adjustments, consider two opposing scenarios laid out by business strategist Michael E. Porter:

Scenario 1: The present owners squeeze the goose to maintain profitability today without worrying about the long term.

This is the take-the-money-and-run strategy. Under this scenario, the owners raise prices and simultaneously try to save their way to profitability with the usual techniques: cutting news hole, reducing staff, peeling back circulation in remote or low-income areas of less interest to advertisers, postponing maintenance and capital improvement, holding salaries down.

It can work. A good newspaper, some sage once observed, is like a fine garden. It takes years of hard work to build and years of neglect to destroy. The advantage of the squeeze scenario for present-day managers is that it has a chance of being successful in preserving their accustomed standard of living for their career lifetimes. Both advertisers and readers are creatures of habit. They will keep paying their money and using the product for a long time after the original reasons for doing so have faded. When the bad end finally comes, the managers who locked the company into the strategy will be in comfortable retirement. They can look back and say, “It didn't happen on our watch.” Porter calls this strategy “harvesting market position.”7

Scenario 2: The present owners—or their successors—will accept the realities of the new competition and invest in product improvements that fully exploit the power of print and make newspaper companies major players in an information marketplace that includes electronic delivery.

That would be consistent with Porter's advice in Chapter 1. “Rather than viewing a substitute as a threat, it may be better to view it as an opportunity,” he says. “Entering the substitute industry may allow a firm to reap competitive advantages from interrelationships between a substitute and a product, such as common channels and buyers.” The movement of newspaper companies into Internet distribution of news and advertising is a good example, because it exploits the newspaper's experience at creating content by applying it to the new distribution medium.

It was that prospect, in fact, that took my old outfit, Knight Ridder, into an experiment with electronic delivery of information way back in 1978. It offered hope of reducing the burden of high variable costs in the newspaper business. A variable cost is one that increases with each unit of production, as opposed to fixed costs which are expressed in units of time. As circulation increases, the cost of newsprint, ink, and transportation rises in direct proportion. For an electronic distribution system, the analogous costs are basically the same whether one hundred or one million consumers read your content.

Under the second scenario, newspaper companies would build, not degrade, their editorial products. And there is a way to profit from the interrelationship between the old technology and the new. Tufts University political scientist Russell Neuman hinted at it in The Future of the Mass Audience. There is a way for newspapers to preserve at least some of their monopoly power. He called it the “upstream strategy.” Find another bottleneck further back in the production process.8

Originally, the natural newspaper monopoly was based on the heavy capital cost of starting a hot-type, letterpress newspaper operation. That high entry cost discouraged competitors from entering the market. Today, computers and cold type have made entry cost low, but the tendency toward one daily umbrella paper per market has continued unabated. That is because the source of the monopoly involves psychological as well as direct economic concerns. In their efforts to find one another, advertisers and their customers like to minimize their transaction costs by converging on the dominant medium in a market. One meeting place is enough. Neither wants to waste the time or the money exploring multiple information sources.

This is why the winner in a competitive market can be decided by something as basic as the amount of classified advertising. One paper becomes the marketplace for real estate or used cars. Display advertisers follow in what, from the viewpoint of the losing publisher, seems a vicious cycle. From the viewpoint of the winner, of course, it is a virtuous cycle.

Neuman's thesis is that the competitive battle across a wide variety of media and delivery systems will make content the new bottleneck. “What is scarce,” he says, echoing Herbert Simon, “is not the technical means of communication, but rather public attention.” Getting that attention depends on content. He cites the victory of VHS over Betamax for home video players. Betamax had superior technology, but the buyers of VHS were attracted by the content because the manufacturer made sure that the video stores had VHS tapes.

How would that principle apply to newspapers? If the argument in Chapter 1 is correct, the most effective advertising medium is one that is trusted. If, as Hal Jurgensmeyer proposed, we define the newspaper's product not as information so much as influence, then we have an economic justification for editorial quality. The quickest way to gain influence is to become a trusted and reliable provider of information.

Trust as the Bottleneck

Trust, in a busy marketplace, lends itself to monopoly. If you find a doctor or a used car dealer that you trust, you'll keep going back without expending the effort or the risk to seek out alternatives. If Walter Cronkite is the most trusted man in America, there can be only one of him. Cathleen Black, when she headed the Newspaper Association of America, was getting at the same idea when she exhorted her members to capitalize on the existing “brand name” standing of newspapers. Brand identity is a tool for capturing trust.

And newspapers are in a good position to win that role of most trusted medium based on their historic roles in their communities. Under Scenario 2, they would define themselves not by the physical nature of the medium, but by the trust that they have built up. And they would expand that trust by improving services to readers, hiring more skilled writers and reporters, taking leadership roles in fostering democratic debate.

Which scenario are we moving toward—harvesting the goose or nurturing it and integrating it with new technology? The signals are no longer mixed. Since the start of the twenty-first Century, newspapers have tilted toward the harvest scenario. Reporters, once secure in their jobs, now hold what Herbert Gans has called “contingent employment.”9 When the Duluth News-Tribune discovered it was not meeting the year's profit goals set by parent Knight Ridder, it decided that it could meet its community service responsibilities with eight fewer reporters, and out the door they went. Layoffs, closing bureaus, and shrinking news holes became commonplace.

On the other hand, the public journalism movement represented an effort to build civic spirit in a way that would, if carried out over a long period of time, emotionally bind citizens to the newspaper. But the wholehearted practice of genuine public journalism involves cost. Newspaper owners preferred the harvesting scenario because it has visible and immediate rewards while the costs are hidden and distant. The nurturing scenario yields immediate costs and distant benefits.

The dilemma cuts across all media and forms of newspaper ownership, but publicly held companies bear a special burden because of Wall Street's habit of basing value on short-term return. I pointed out the precarious state of Knight Ridder in a 1995 article and updated it in lectures. The last update was in 2003, and here is what it showed.

With total average daily circulation of 4 million, its newspapers would bring a total of $7.2 billion if sold separately at an average value of $1,800 per paying reader. (McClatchy paid the Daniels family more than $2,400 per unit of circulation for Raleigh's News & Observer, but Raleigh was a better than average market). With 82.3 million shares outstanding at the early 2003 price of $64 per share, the entire company, including its non-newspaper properties, was valued by its investors at only $5.3 billion, or $1.9 billion less than the break-up value.

The investor who forced the breakup of Knight Ridder was Bruce Sherman of Private Capital Management, who had decided to bet on newspapers after the dot.com bubble burst in 2000. Perhaps, he reasoned, the Internet threat had been overestimated. Soon he owned 19 percent of Knight Ridder.

But by 2004, Internet advertisers, led by Craigslist, were cutting into newspaper revenue, and Sherman realized that his bet had been a bad one. He had too many Knight Ridder shares to unload without driving the price down. But if the entire company were sold, he had a good chance of getting out without taking a beating. With the help of other unhappy investors, he was in a position to elect a new board that would throw out the existing management and get the sale done. CEO Tony Ridder saw the hand he had been dealt and decided to do the deed himself while he could still negotiate favorable terms for himself and his officers. Knight Ridder was sold to McClatchy Newspapers, and Sherman made a modest profit on his shares.10

McClatchy was a well-respected public company that was insulated from investor pressure by a two-class stock plan. But it was still forced by the changing economics of the media into the unwanted scenario of squeezing the golden goose. Here's how it works. A newspaper that depends on customer habit to keep the dollars flowing while it raises prices and gives back progressively less in return has made a decision to liquidate. It is a slow liquidation and is not immediately visible because the asset that is being converted to cash is intangible—what the bean counters call “good will.”

Good will is the organization's standing in its community. More specifically, it is the habit that members of the community have of giving it money. In accounting terms, it is the value of the company over and above its tangible assets like printing presses, cameras, buildings, trucks, and inventories of paper and ink. In 1995, I asked two people who appraise newspapers for a living, John Morton of Washington, D.C., a former analyst, and Lee Dirks of Santa Fe, a newspaper broker, to estimate the proportion of a typical newspaper's value represented by good will at that time. Both gave the same answer: 80 percent. That left only 20 percent for the physical assets.

This was vital intelligence for an entrepreneur interested in entering a market to challenge a fading newspaper. As an existing paper cut back on its product and its standing in the community fell, there had to come an inevitable magic moment when a competitor could move in, start a paper and build new good will from scratch, ending up owning a paper at only 20 percent or one-fifth of the cost of buying one.

Such a scenario is overly simplified, of course. Newspaper valuations have fallen drastically since 1995, and all of the decline has been in the intangible good-will portion. Today's opportunity is more likely to arise from another direction—from a newspaper bankruptcy. If a town's only newspaper shuts down and the physical assets are sold to pay creditors, the buyer of those assets could start a paper without the debt burden of a previous owner who still had historic good will to amortize. In either case, the newcomer would have a tremendous advantage, and that is its lower capitalization. Because its outlay is only the cost of the physical plant, one-fifth of the historic value of the existing paper, the newcomer can get the same return on investment with a 6 percent margin that the old paper's owners got with a 30 percent margin. Voila! A happy publisher with a 6 percent margin! Because this publisher would be building good will from scratch, he or she could cheerfully pour money into the editorial product, invest in the Internet, expand circulation, create new bureaus, heavy up the news hole and do the polling and special public interest investigations that define public journalism.

This dream is not so wild. Remember Al Neuharth. One of the factors that propelled him to the top at Gannett was his astuteness in recognizing a parallel situation in east central Florida. Rapid population growth stimulated by space exploration had created a community that needed its own newspaper. He founded Florida Today for significantly less than the cost of buying an existing paper. The only obstacle is finding the right time and place—plus an opposition that is greedy and either shortsighted or slow-footed enough to continue squeezing out the old margins in the face of a challenge.

To old newspaper hands, the prospect of battles between the newspaper squeezers and the newspaper nurturers has a definite charm. Some of us old enough to remember the fun of working in competitive markets would line up to work for the nurturer against the squeezer. But the threat to companies that are liquidating their good will might come from another direction. It might not come from other newspaper companies at all.

The race to be the entity that becomes the institutional Walter Cronkite in any given market will not be confined to the suppliers of a particular delivery technology. How the information is moved—copper wire, cable, fiberglass, microwave, a boy on a bicycle—will not be nearly as important as the reputation of the creators of the content. Earning that reputation may require the creativity and the courage to try radical new techniques in the gathering, analysis, and presentation of news. It might require a radically different definition of the news provider's relationship to the community, as well as to First Amendment responsibilities.

It is fashionable to blame Wall Street for the bind in which newspaper companies find themselves. However, not all investors and analysts have a narrow, short-term orientation. Analyst O'Donnell, writing a quarter of a century ago, observed that quality journalism “can be expensive, but it helps a paper build an image that attracts talented employees both in news and other departments. We have spoken to employees in press rooms, for example, who take great pride in working on a newspaper that wins national awards. . . . [T]he perceived ‘quality’ of a paper can be a critical factor in morale and is not to be underestimated. . . . [R]eaders' perceptions of the value of the product are substantially related to the quality of the news coverage.”11

Analysts and investors make their money by spotting trends and taking investment positions in them before their competitors do. If journalistic quality is to have value on Wall Street, we will have to make the case that it is a leading indicator of profitability. If it is, savvy investors will find out eventually. The free market makes it inevitable. But the market sometimes takes a very long time to work its will, and we should not expect existing newspaper organizations to help very much.

Newspapers' inherent conservatism, a consequence of their easy-money history, places them at a disadvantage in attempts at innovation. The pressures to harvest their market position by squeezing out the historic margins in the short term have made them inflexible. But if influence is the product, sooner or later some business entity will find a way to package and sell it, and the castle that it builds on its rock will shelter the best and the brightest creators of content.

1. Non-accountants sometimes confuse margin with return on investment. They are not the same. Margin is the proportion of revenue left to fall to the bottom line after expenses are paid. Return on investment (ROI) depends on the size of the investment, i.e., what was paid to create the money-making enterprise. Thus a supermarket can have a larger ROI on its two percent margin than a newspaper with twenty percent margin because it takes less investment to create.

2. Donnell, “The Business of Newspapers: An Essay for Investors,” E. F. Hutton Equity Research, Feb. 12, 1982.

3. These numbers are based on grouped data compiled by the Inland Daily Press Association, “National Cost and Revenue Study for Daily Newspapers for 2001.”

4. Picard, Evolution of Revenue Streams and the Business Model of Newspapers: the U.S. Industry between 1950–2000, Business Research and Development Center, Turku School of Economics and Business Administration, Turku, Finland, (2002), 25. Also published in Newspaper Research Journal 23:4 (Fall 2002), 21–33.

5. Jon G. Udell, The Economics of the American Newspaper (New York: Hastings House, 1978), 30.

6. Picard, Evolution, 20.

7. Porter, Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance (New York: The Free Press, 1985), 311.

8. Neuman, The Future of the Mass Audience (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1991), 150.

9. Gans, Democracy and the News (New York: Oxford University Press, 2003),

10. Katherine Q. Seelye, “What-Ifs of a Media Eclipse,” New York Herald Tribune (August 28, 2006).

11. O'Donnell, “The Business of Newspapers,” pp. 13–14. Like several other analysts, O'Donnell spoke from the vantage point of a former newspaper person. He was Knight Ridder's director of corporate relations in the late 1970s.