How long does it take you to change your mind about something? A day? A week? A month? Longer? No, not at all, we can actually change our minds very quickly indeed. Sure, we might procrastinate and put it off for a while. We might think about it a lot, even tell ourselves stories about it, and find evidence for us being right. We might endlessly chat it over with friends and on and on and on, but when it actually comes down to it, we change our minds quickly – in a heartbeat – and so, in exactly the same way, natural, permanent and effective change only ever happens fast, just like that.

Neuro-Linguistic Programming (NLP) is a method of influencing our brain’s behaviour (the ‘neuro’ part of Neuro-Linguistic Programming) through the use of language (the ‘linguistic’ part) and other types of communication to enable us to ‘recode’ the way our brain responds to stimuli (that’s the ‘programming’) and enjoy new and better, more appropriate behaviours.

NLP could best be described as a hybrid of techniques – a collection of the best bits, or an ensemble, of what works best from many other therapeutic disciplines – underpinned by some core principles, such as that change happens fast and we are separate from our behaviours. In the same way that two computers can run two different programs – and in effect be two different products – while at their core only the hardware (our head) is fixed; the programming (our behaviours) is completely interchangeable. NLP often incorporates both hypnosis and self-hypnosis too, to help achieve the desired change (or ‘programming’).

Dr Richard Bandler invented the term ‘Neuro-Linguistic Programming’ in the 1970s, and was recently asked to write the definition of NLP for the Oxford English Dictionary, which reads: ‘A model of interpersonal communication chiefly concerned with the relationship between successful patterns of behaviour and the subjective experiences (esp. patterns of thought) underlying them’; and ‘A system of alternative therapy based on this which seeks to educate people in self-awareness and effective communication, and to change their patterns of mental and emotional behaviour.’

So NLP is fundamentally two things:

Or, in plain English, NLP is the art and science of excellence, derived from studying how top people in different fields obtain their outstanding results; and also a therapy based on shining a light of awareness on the internal processes and programs so that we can change. The good news is that anyone can learn these communication skills and improve their effectiveness, both personally and professionally.

NLP began in the early 1970s as a simple university thesis project in Santa Cruz, California. Then student, Richard Bandler, and his professor, John Grinder, wanted to develop models of human behaviour to understand why certain people seemed to be excellent at what they did, while others found the same tasks very challenging or nearly impossible to accomplish – all other things being equal, of course.

Inspired by pioneers in different fields of therapy and personal growth and development, Bandler and Grinder began to develop systematic procedures and theories that formed the foundations of what we know today as NLP.

The early focus of NLP was on modelling. In other words, if you do something really well and I do exactly the same as you, then we will both get the same result. Logically it makes sense, but how? Clearly, it is our mind that drives our body so what do we need to do differently in our mind to get a different result from our body?

Fascinated by the world of therapy, Bandler and Grinder began by studying three top therapists: Virginia Satir, a family therapist, who was able to get extraordinary results and consistently resolve difficult family relationships, which many other therapists found impossible; innovative psychotherapist Fritz Perls, who founded the school of therapy known as Gestalt therapy; and then, famously, the great Milton Erickson, the world’s leading hypnotherapist.

Their goal was to develop models of how these three therapists got results so fast. The concept of modelling is a very simple principle and so they focused on the how by identifying and modelling the patterns or techniques that consistently produced these outstanding results. The acid test of this modelling being that they would then be able to teach these models to others and get the same results – even without any of the original therapists’ background skill, experience or knowledge.

These three very gifted therapists were also very different personalities and ascribed to very different modalities of change, yet Grinder and Bandler discovered some powerful underlying patterns in their work that were very similar. It was these key patterns or techniques that became the foundation structure of NLP as we know it today, and many of the well-known NLP phrases – e.g. meta model, submodalities, reframing, language patterns, well-formed outcomes, conditions and eye-accessing cues – all come from this very early formulation period.

It’s not known, or perhaps just not remembered, when the phrase ‘Neuro-Linguistic Programming’ was first used to describe the process of how personality creates and expresses itself. But when Bandler and Grinder started teaching NLP it’s reported that the first class of students quickly nicknamed it ‘Mindf**k 101’. Fortunately, the nickname didn’t stick or the world of therapy could be a very different place.

NLP works on the principle that humans are made up of a neurology that conveys information about our environment to the central nervous system and brain. Since we are also meaning-creating creatures, we have to make sense of things in order to know what to do with them, so we translate these perceptions into meanings, beliefs and then expectations.

As we grow from a baby into a more complex adult human, we tend to filter, distort and magnify the input we get from our environment so that it matches the elaborate program we’ve evolved to explain our life experiences to ourselves.

As infants, we pass through the ‘magical thinking’ phase, and various other stages of development, on our journey to adulthood. Magical thinking is most dominantly present in children aged between two and seven years. During this time, children strongly believe that their personal thoughts have a direct effect on the rest of the world. Therefore if they experience something tragic they don’t understand, for example a death, their mind creates a reason to feel responsible. Jean Piaget, a developmental psychologist, came up with the theory of four developmental stages, and children aged between two and seven years are classified under his ‘Preoperational Stage’ of development. During this stage children are perceived not to be able to use logical thinking. Their young minds don’t understand the finality of an event like death, and so magical thinking bridges the gap.

The study of how we do all this at all ages, the kinds of meanings we make up from our perceptions and the internal programming and external behaviours we set up to explain, predict and make sense of it all – this is what the core of NLP is all about.

In NLP, we are not so much interested in why we do what we do, but how. The why part relates to history and the meaning we give it, but we can’t change history. It also relates to people trying to do the best they could at the time and subsequently, given their frame of reference, the experience filters that they are passing the information through and also the best options they ‘think’ they have in the moment. For the most part, people are generally trying to do their best. Very few deliberately set out to be assholes (although many achieve it), but most people are simply doing the best they can, given all those factors. For that reason, how someone constructs their subjective experience is far more useful than why they do so, not to mention far easier to change – and with far more variables, and therefore options, for different outcomes than anything else we have to work with.

Today, NLP has grown in a myriad different directions, including hypnosis and behavioural, personal change work and structures of beliefs, as well as modelling personal success, systems of excellence, expertise in business coaching and sales training. It has been ‘popularized’ by the remarkable works of luminaries such as Paul McKenna, John La Valle, Robert Dilts, Tad James, Tony Robbins, Michael Neill, Eric Robbie, Phil Parker and, of course, Dr Richard Bandler himself. Richard, to be absolutely correct, is credited as the co-creator of NLP. His then professor, John Grinder, has also developed their creation further as Richard still does, but it’s the Bandler school of thought that has really shaped NLP as most people know it.

In my own work as a therapist and life coach, NLP is just what I do. As a result, my understanding has deepened as to the nature of our subjective experience. I’d like to think that some of what you’re learning here is akin to being given the TV remote to your brain: you can make the horror movie less scary and, in fact, even change the channel to something that makes you feel good. But it is worth mentioning that what you see, think and believe in your head is just a movie and when you stop engaging with it – stop believing it and acting as though it were true – you automatically go back to your default setting (which is happy) anyway.

There really is nothing you need to do to make yourself happy. Happiness is just what happens when you do less on the inside, not more. Just as the nature of water is clear, you don’t need to do anything to make it clearer, or keep it clean, it is just clear. If, for any reason, it’s not, then the best way to return it to clarity is not finding a new way to shake it or stir it up, but to leave it alone. And that is exactly the same with you. You have an innate clarity, an innate wellbeing and an innate knowing. Sure, sometimes your thoughts get in the way, and you will find some great techniques in the following chapters to help you when they do, but they work in the same way that a dressing on a cut provides a clean environment for it to heal. In other words, it is not the dressing that does the healing, it is you; the dressing simply helps you to heal and returns you to your natural setting of wellness.

I am delighted and grateful to Dr Bandler for the impact that NLP has had on my life and the lives of the countless people I have been able to help. Giving someone the control they are looking for is a priceless gift, just as being able to adjust the movie and live a different life is a special thing. However, realizing that you are already OK and knowing when you stay out of your own way for long enough you tend to do just great, is a profound and life-changing insight for most people – perhaps now for you too.

As I alluded to earlier, aspects of NLP have also been incorporated into other therapies too, such as EMDR (eye movement desensitization and reprocessing). NLP has also been taken in a more spiritual direction and used to assist in the alignment of personal behaviours and beliefs with a higher purpose and connection to the Divine and spirit. Some have even developed processes to speed healing in hospital settings and to lessen the need for anaesthesia during medical procedures. NLP techniques have also been applied to influencing sales and negotiations, and even how to pick up women. You name it, there’s probably an NLP-related application for it and a book about it too, but here we’ll be focusing on its therapeutic applications, where it’s proved so successful.

Take phobias, for example, an easy and illustrative choice. A phobia could be defined as ‘an irrational fear’ and so if it is ‘irrational’ then it has to be a product of our subjective experience because there is no rational basis for it, but we think there is… So, for instance, public speaking is listed as the second biggest fear after death, which means that almost as many people would be as scared of giving the eulogy at a funeral as they would be of being in the casket itself.

NLP has proved incredibly successful in treating irrational fears, as well as issues such as stage fright, parenting, allergies and trauma. In fact the list of areas where training in NLP and individual therapeutic work with NLP practitioners is valuable is endless – and that is simply because NLP is not about any of these specific things but about people. The hardware is more or less the same in each of us, it’s the software that is variable and this can be reprogrammed quickly and easily with NLP, often just by pressing the ‘restore factory settings’ option and allowing us to be OK.

So, if you’ll pardon the pun, let’s start by looking at one of most well-known, if controversial, discoveries in NLP, but also potentially one of the most valuable to the novice NLPer: the observation of eye movements as indicators of specific cognitive processes.

Learning to read ‘eye-accessing cues’, as they are called, is a fairly simple skill and you’ll probably already know that when speaking to someone their eyes tend to move all over the place. Whilst it is socially acceptable, and even expected, to look the other person in the eye, we just can’t seem to do that and think at the same time. It’s almost as if we have to look away in order to be able to access our thoughts. I distinctly remember at school (and I wasn’t at all good at school stuff) being asked a question, quickly followed by the teacher barking at me that the answers weren’t on the ceiling. For some reason, my eyes had drifted up whilst I was genuinely trying to think – well, before I was interrupted, that is – and when I had to look at her, I just couldn’t think at all. My mind went blank, even though I knew that I knew the answer; it was on the tip of my tongue, if only I could get to it.

I’m sure you’ve had a similar experience, or will have certainly noticed people’s eyes moving around when you’ve had a conversation. But have you ever noticed how they move?

Imagine in your mind’s eye that you have a screen much like that on your computer. You know that you need to move the little cursor around to access different files on your computer. Well, it’s exactly the same in your mind, only your eyes are like the cursor and the files are all arranged nice and neatly so you don’t need to search around too much. The reason that my eyes naturally drifted upwards to find the answer to the question is that I am predominantly visual and had stored the answer – or at least the image to access the answer – not on the ceiling (that would be cheating), but in the folder of images that we all access by looking up. You’ll have seen people do that and then perhaps say ‘let me see’, as they ‘look’ for the answer.

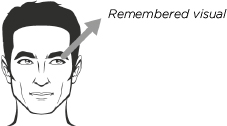

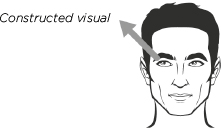

For a right-handed person, images that are memories tend to be up and to the left. Without looking, quickly, which side is the handle on your front door? Notice where your eyes go to access the information. Images from which we must construct the answer tend to be up and to the right. So, just imagine an elephant crossed with a rhino… where did you look? Up and right?

(But what do you call an elephant crossed with a rhino? ‘Eleph – I – no’? Sorry, couldn’t resist!)

Ask yourself the following, and just notice where your eyes go, then get some of your friends to do the same:

All these questions are designed to make you access your visual memory, which means, for right-handed people, the eyes should go up and left.

Like most things, eye-accessing cues are not new, but rather brought together from somewhere else to give a ‘best of breed’ solution. The notion that eye movements might be related to internal representations was first suggested way back by American psychologist William James in his book Principles of Psychology. Observing that some forms of micro movement always accompany thought, James wrote:

‘In attending to either an idea or a sensation belonging to a particular sense-sphere, the movement is the adjustment of the sense-organ, felt as it occurs. I cannot think in visual terms, for example, without feeling a fluctuating play of pressures, convergences, divergences, and accommodations in my eyeballs… When I try to remember or reflect, the movements in question… feel like a sort of withdrawal from the outer world. As far as I can detect, these feelings are due to an actual rolling outwards and upwards of the eyeballs.’1

What James is describing is well known in NLP as visual eye-accessing cues, but his observation lay dormant until the early 1970s when psychologists2–4 first began to equate lateral eye movements with processes related to the different hemispheres of the brain. They observed that right-handed people tended to shift their heads and eyes to the right during ‘left hemisphere’ (logical and verbally oriented) tasks, and move their heads and eyes to the left during ‘right hemisphere’ (artistic and spatially oriented) tasks. That is, people tended to look in the opposite direction of the part of the brain they were using to complete a cognitive task.

Then, in early 1976, Richard Bandler, John Grinder and their students began to explore the relationship between eye movements and the different senses, as well as the different cognitive processes associated with the brain hemispheres.5

But in 1977, Robert Dilts at the Langley Porter Neuropsychiatric Institute in San Francisco took it all a step further, when he attempted to correlate eye movements to particular cognitive and neurophysiological processes. Dilts used electrodes to track both the eye movements and brainwave characteristics of subjects who were asked questions related to using the various senses of sight, hearing and feeling for tasks involving both memory (right-brain processing) and mental construction (left-brain processing).

Subjects were asked a series of questions in eight groupings. Each grouping of questions appealed to a particular type of cognitive processing; what we know as visual, auditory and kinaesthetic (feelings). Each was also geared to either memory (non-dominant hemisphere processing) or construction (dominant hemisphere processing). Dilts’ recordings tended to confirm other tests that showed that eye movements accompanied brain activity during different cognitive tasks. This pattern also seemed to hold for tasks requiring different senses.6–7

As a result of these and other studies8–9 – and many hours of observations of people from different cultures and racial backgrounds from all over the world – the following eye-movement patterns were identified.

From the person’s perspective

The diagram below illustrates the basic NLP eye-accessing cues.

This pattern appears to be constant for right-handed people throughout the human race, with the possible exception of inhabitants of the Basque region who, interestingly but completely inexplicably, appear to offer a fair number of exceptions to the rule – definitely one for an NLP pop quiz.

Many left-handed people, however, tend to be reversed from left to right. That is, their eye-accessing cues are the mirror image of those of the average right-handed person. They look down and left for feelings, instead of down and right. Similarly, they look up and to the right to remember visual imagery, instead of up and to the left, and so on. A small number of people (including ambidextrous and a few right-handed people) will be reversed in some of their eye-accessing cues (their visual eye movements, for example), but not the others.

To explore the relationship between eye movements and thinking, have a play with these eye-accessing cues. It’s definitely easier if you find a partner; just ask the following questions and observe their eyes.

We’ve practised the first visual cues already, but for completeness, they are included in this exercise as well.

We all have far more scope for expression than most of us ever use, and also far more versatility and ability to change how we feel in any given moment. The problem is that we have it lined up in the wrong way a lot of the time, and so we generally just don’t appreciate how many shades there are or how many distinctions we are able to make whenever we want. We humans are creatures of habit and we tend to redo things the way we have always done them… why?

Well, for the same reason that, even though all that information has been there all along, you just didn’t know any better. But as soon as you notice for the first time what’s there, then you can’t un-notice it and it will always be there for you to use. The world and the people in it have always been like that; you’ve just never noticed before.

However, there are two small yet vital points of caution:

If I am working in almost any capacity with someone, I almost always begin by making chitchat about what they did at the weekend and what they’ll be doing later – nothing major, just day-to-day small talk. It seems very normal and natural, and people certainly don’t think anything of it. BUT this is actually when I am paying the most attention because, in actual fact, I’m calibrating to them. What they got up to last weekend, the way they describe it and where their eyes go gives me a very good calibration reference point for how they recall information.

We have to assume that they are telling the truth, of course, but we’ll take that as a given because they certainly have no reason to lie to me. Then what they are doing for the rest of the day tells me how they ‘construct’ information, as they have to do so in order to be able to make sense of what’s coming next. Be a little careful because if that’s somewhere they go or have been to before, they might have to access a memory in order to create the frame into which they can then place the scene.

However, you’ll notice that I have asked ‘what’ they are doing later, not where they will be going, so usually, after a brief foray into the past to get the scene set, they will be over on the right side constructing and giving me another really useful calibration reference point. You might also like to notice on which wrist they wear their watch (although this is increasingly less reliable) or which hand they write with to know which is their dominant hand. The second point is that even once you’re sure of how they are ‘wired up’, be careful before jumping to the conclusion that someone might be lying. We need to be very careful and clean with the questions that we ask.

I was once sitting in, assisting on an interview panel to select some very senior managers for an organization, and when one candidate left the room, the HR person turned to me and said, ‘I think he was the best so far; it’s a real pity he was lying.’ There then ensued a very long conversation about how they knew that from the person’s eye-accessing cues. (She had been on a one-day NLP course and thought she had it sussed.) Here’s the question she asked and here’s how his eyes moved… Can you spot where she went wrong?

‘In your previous role with XYZ Corporation, what was a key skill that you developed, the one that gave the biggest results, and how would you be able to utilize that experience here?’

His eyes did this… for a split second.

When challenged, the HR person said that she knew for certain that he was lying because he looked up and right the entire time when answering, only occasionally looking at her and then ‘furtively’ (as she put it) looking away and up and right, which showed he was lying.

What she hadn’t factored in, however, was that while in her head, her line of questioning was rooted in what the candidate would bring to her company based on his last job (and he did access up and left to find that memory, but only for a split second), the majority of the thinking required to answer the question accurately actually required him to construct an answer placed in the future. Given that he had never worked for that company and had therefore never used any of his skills there, never mind that one, the only possible way to form an answer was to project what he did know into that situation and to keep doing so until he felt he had given as complete an account as his imagination would allow him to construct. Which is exactly what he did.

What the interviewer mistook for looking ‘furtively’ away from her eye contact was actually the candidate quickly getting back to his picture under interview pressure to continue with his answer before he lost his train of thought. She completely missed the ‘up and left’ visual-recall accessing cue. After clearing that up, the guy got the job! Of course, what would have helped would have been if our candidate had been able to build better rapport in the first place. Although I’m sure it wouldn’t have prevented the HR person from getting it wrong, she would have been much more likely to give him the benefit of the doubt.

This chapter has been all about noticing what’s always been there, but that you’ve just never noticed before. I wonder where else that might be true in your life? Yes, take away what you have learned about eye movements and accessing cues from here, but there’s a much bigger ‘take away’ too. The more you turn up your own sensory acuity, and the more you pay attention to the world and those around you, the more options you have, both in what to do and how to be next.