Musée de l’Armée

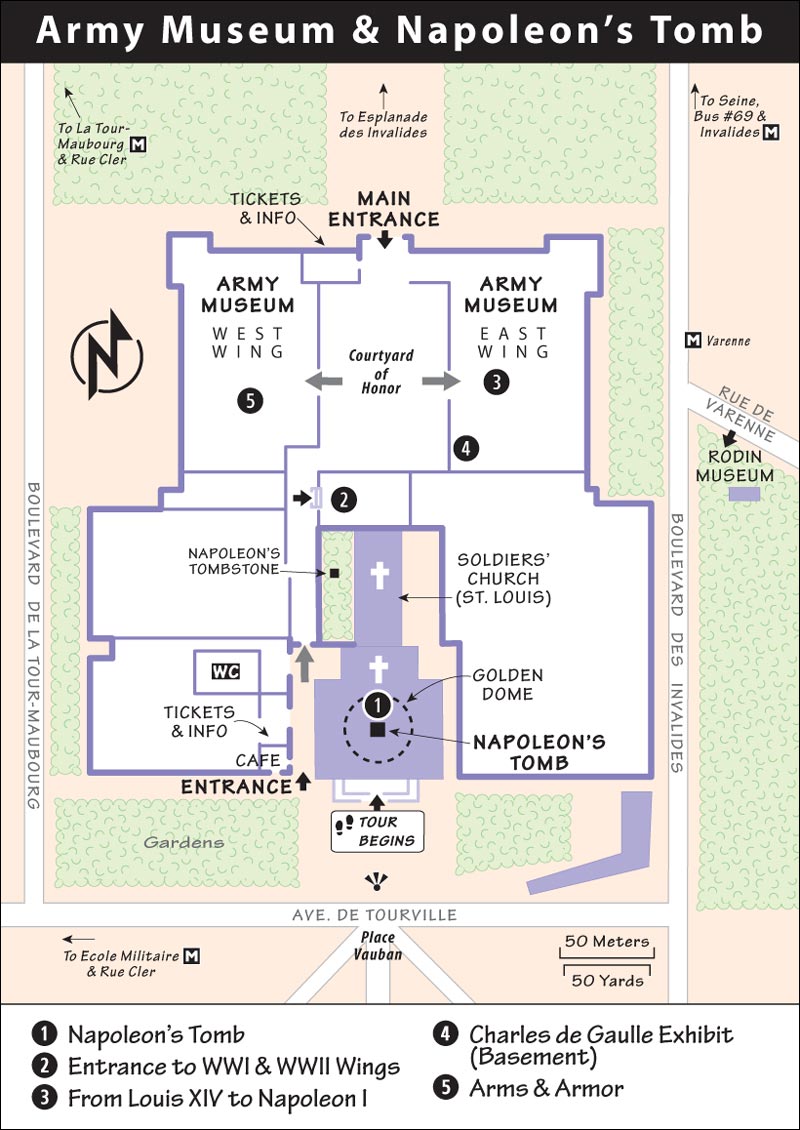

Map: Army Museum & Napoleon’s Tomb

Third Floor—Axis Aggression (1939-1941)

Second Floor—The Tide Turns (1942-1944)

First Floor—The War Slowly Ends (1944-1945)

From Louis XIV to Napoleon I (1643-1814)

If you’re ever considering trying to conquer Europe to become its absolute dictator, come here before gathering your army. Hitler did, but still went out and made the same mistakes as his role model. (Hint: Don’t invade Russia.) Napoleon’s tomb rests beneath the golden dome of Les Invalides church.

In addition to the tomb, the complex of Les Invalides—a former veterans’ hospital built by Louis XIV—has various military collections, collectively called the Army Museum. See medieval armor, Napoleon’s horse stuffed and mounted, Louis XIV-era uniforms and weapons, and much more. The best part is the section dedicated to the two world wars, especially World War II. Visiting the different sections, you can watch the art of war unfold from stone axes to Axis powers.

(See “Eiffel Tower & Nearby” map, here.)

Cost: €9.50, €7.50 after 16:00, covered by Museum Pass, admission includes Napoleon’s Tomb and all the museum collections within the Invalides complex. Temporary exhibitions are extra. Children are free, but you must line up to get them a ticket. The sight is also free for military personnel in uniform.

Hours: Daily 10:00-18:00, July-Aug until 19:00, Nov-March until 17:00; tomb plus WWI and WWII wings open Tue until 21:00 April-Sept; museum (except for tomb) closed first Mon of month Oct-June; Charles de Gaulle exhibit closed Mon year-round; last tickets sold 30 minutes before closing.

Getting There: The museum and tomb are at Hôtel des Invalides, with its hard-to-miss golden dome (129 Rue de Grenelle, Mo: La Tour Maubourg, Varenne, or Invalides). You can also take bus #69 from the Marais and Rue Cler area or bus #87 from Rue Cler and the Luxembourg Garden area. The museum is a 10-minute walk from Rue Cler. There are two entrances: one from the Grand Esplanade des Invalides (river side), the other from behind the gold dome on Avenue de Tourville.

Information: A helpful, free English map/guide is available at the ticket office. Tel. 01 44 42 38 77 or 08 10 11 33 99, www.musee-armee.fr.

Tours: The fine €6 videoguide covers the whole complex.

Length of This Tour: Women—two hours, men—three hours.

WCs: Military leaders have better things to do than provide WCs, and women have better things to do than stand in line at the scarce toilets in this complex. Find a WC before coming here.

Photography: Allowed without flash.

Eating: The cafeteria is reasonable, the rear gardens are picnic-perfect, and Rue Cler is a 10-minute walk away (see here).

Nearby: You’ll likely see the French playing boules on the esplanade (as you face Les Invalides from the riverside, look for the dirt area to the upper right; for the rules of boules, see here).

Starring: Napoleon’s Tomb, exhibits on World War II, memorabilia of Napoleon (including his stuffed horse).

(See “Army Museum & Napoleon’s Tomb” map, here.)

• You can enter the vast Invalides complex of chapels and museum exhibits from either the north or south side (ticket offices are at both entrances). Start at Napoleon’s Tomb—underneath the golden dome, with its entrance on the south side (farthest from the Seine).

(See “Army Museum & Napoleon’s Tomb” map, here.)

Enter the church, gaze up at the dome, then lean over the railing and bow to the emperor lying inside the scrolled, red porphyry tomb (see photo at the beginning of chapter). If the lid were opened, you’d find an oak coffin inside, holding another ebony coffin, housing two lead ones, then mahogany, then tinplate...until finally, you’d find Napoleon himself, staring up, with his head closest to the door. When his body was exhumed from the original grave and transported here (1840), it was still perfectly preserved, even after 19 years in the ground.

Born of humble Italian heritage on the French-owned isle of Corsica, Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821) went to school at Paris’ Ecole Militaire, quickly rising through the ranks amid the chaos of the Revolution. The charismatic “Little Corporal” won fans by fighting for democracy at home and abroad. In 1799, he assumed power and, within five short years, conquered most of Europe. The great champion of the Revolution had become a dictator, declaring himself emperor of a new Rome.

Napoleon’s red tomb on its green base stands 15 feet high in the center of a marble floor, circled by a mosaic crown of laurels and exalted by a glorious dome above.

Napoleon is surrounded by family. After conquering Europe, he installed his big brother, Joseph, as king of Spain (turn around to see Joseph’s black-and-white marble tomb in the alcove to the left of the door); his little brother, Jerome, became king of the German kingdom of Westphalia (tucked into the chapel to the right of the door); and his baby boy, Napoleon II (downstairs), sat in diapers on the throne of Rome.

In other alcoves, you’ll find more dead war heroes, including Marshal Ferdinand Foch, the commander in chief of the multinational Allied forces in World War I, his tomb lit with otherworldly blue light. To the right of Foch lies Maréchal Vauban, Louis XIV’s great military engineer, who designed the fortifications of more than 100 French cities. Vauban’s sarcophagus shows him reflecting on his work with his engineer’s tools, flanked by figures of war and science. These heroes, plus many painted saints, make this the French Valhalla in the Versailles of churches.

Before moving on, consider the design of the church itself. It’s actually a double church—one for the king and one for his soldiers—built under Louis XIV in the 17th century. You’re standing in the “dome chapel,” decorated to the glory of Louis XIV and intended for royalty before it became the tomb of Napoleon. The original altar was destroyed in the Revolution. What you see today dates from the mid-1800s, and was inspired by the altar and canopy at St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome.

Behind the altar is the Church of St. Louis, where the veterans hospitalized here attended (mandatory) daily Mass. You can peek into this church as you descend to the floor level of Napoleon’s tomb. (You can’t enter the Church of St. Louis from here, but you can from the main courtyard.)

• The stairs behind the altar (with the corkscrew columns) take you down to crypt level for a closer look at the tomb.

(See “Army Museum & Napoleon’s Tomb” map, here.)

As you descend the stairs from the altar, notice how Napoleon’s tomb is a kind of grand room within this church. At the bottom of the steps, face its entrance, which is flanked by two bronze giants representing civic and military strength. The writing above the door is Napoleon’s wish for his remains to be with the French people. And, like a welcome mat, a big inlaid N welcomes you into the tomb of perhaps the greatest military and political leader in French history.

Wandering clockwise, read the names of Napoleon’s battles on the floor around the base of the tomb. Rivoli marks the battle where the rookie 26-year-old general took a ragtag band of “citizens” and thrashed the professional Austrian troops in Italy, returning to Paris a celebrity. In Egypt (Pyramides), he fought Turks and tribesmen to a standstill. The exotic expedition caught the public eye, and he returned home a legend.

Napoleon’s huge victory over Austria at Austerlitz on the first anniversary of his coronation made him Europe’s top dog. At the head of the million-man Great Army (La Grande Armée), he made a three-month blitz attack through Germany and Austria. As a military commander, he was daring, relying on top-notch generals and a mobile force of independent armies. His personal magnetism on the battlefield was said to be worth 10,000 additional men.

Pause halfway around to gaze at the grand statue of Napoleon the emperor in the alcove at the head of the tomb—royal scepter and orb of earth in his hands. By 1804, all of Europe was at his feet. He held an elaborate ceremony in Notre-Dame, where he proclaimed his wife, Josephine, empress, and himself—the 35-year-old son of humble immigrants—emperor. The laurel wreath, the robes, and the Roman eagles proclaim him the equal of the Caesars. The floor at the statue’s feet marks the grave of his son, Napoleon II (Roi de Rome, 1811-1832).

Around the crypt are relief panels showing Napoleon’s constructive side. Dressed in toga and laurel leaves, he dispenses justice, charity, and pork-barrel projects to an awed populace.

• In the first panel to the right of the statue...

He establishes an Imperial University to educate naked boys throughout “tout l’empire.” The roll of great scholars links modern France with those of the past: Plutarch, Homer, Plato, and Aristotle. Three panels later, his various building projects (canals, roads, and so on) are celebrated with a list and his quotation, “Everywhere he passed, he left durable benefits” (“Partout où mon regne à passé...”).

Hail Napoleon. Then, at his peak, came his fatal mistake.

• Turn around and look down to Moscowa (the Battle of Moscow—marked beneath his tomb).

Napoleon invaded Russia with 600,000 men and returned to Paris with 60,000 frostbitten survivors. Two years later, the Russians marched into Paris, and Napoleon’s days were numbered. After a brief exile on the isle of Elba, he skipped parole, sailed to France, bared his breast, and said, “Strike me down or follow me!” For 100 days, they followed him, finally into Belgium, where the British hammered the French at the Battle of Waterloo (conspicuously absent on the floor’s decor). Exiled again by a war tribunal, he spent his last years in a crude shack on the small South Atlantic island of St. Helena.

• To get to the Courtyard of Honor and the various military collections, exit the same way you entered, make a U-turn right, and march past the cafeteria and ticket hall. Pause halfway down the long hallway. On the right, through the glass, you’ll see...

(See “Army Museum & Napoleon’s Tomb” map, here.)

This bare stone slab, surrounded by shrubs and weeping willows, once rested atop Napoleon’s grave on the island of St. Helena. The epitaph was never finished because the French and British wrangled over what to call the hero/tyrant. The stone simply reads, “Here lies...”

• Continuing to the end of the hallway, you’ll find the entrance to the World War I and World War II wings. Go upstairs, following blue banners reading Les Deux Guerres Mondiales, 1871-1945. The museum is laid out so you first see the coverage of World War I, though some may choose to skip ahead to the more substantial WWII section.

(See “Army Museum & Napoleon’s Tomb” map, here.)

World War I (1914-1918) introduced modern technology to the age-old business of war. Tanks, chemical weapons, monstrous cannons, rapid communication, and airplanes made their debut, conspiring to kill nearly 10 million people in just four years. In addition, the war ultimately seemed senseless: It started with little provocation, raged on with few decisive battles, and ended with nothing resolved, a situation that sowed the seeds of World War II.

This 20-room exhibit leads you chronologically through the background, causes, battles, and outcome. There’s good English information posted on the walls in most rooms, and video displays have English versions—but the displays themselves are lackluster and low-tech; move quickly and don’t burn out before World War II. Prepare to hunt for some room numbers to follow my tour. A quick walk-through gives you the essential background for the next world war.

Paintings of dead and wounded soldiers from the Franco-Prussian War make it clear that World War I actually “began” in 1871, when Germany thrashed France. Suddenly, a recently united Germany was the new bully in Europe.

Snapping back from its loss, France began rearming itself, with spiffy new uniforms and weapons like the American-invented Gatling gun (early machine gun).

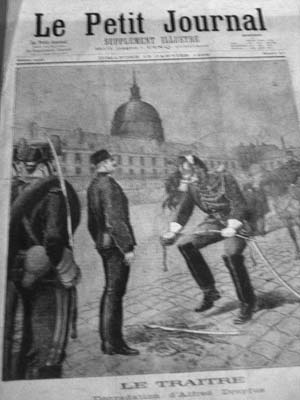

The French replaced the humiliation of defeat with a proud and extreme nationalism. An English-language video shows how fanatical patriots hounded a (Jewish) officer named Alfred Dreyfus on trumped-up treason charges (1890s). They convicted and imprisoned him (after ceremonially breaking his sword in the Invalides courtyard), before he was finally acquitted.

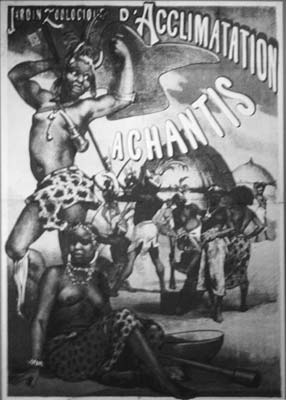

France, Germany, and the rest of Europe were in a race for wealth and power, jostling to acquire lucrative colonies in Africa and Asia (map, video, exotic uniforms). In a climate of mutual distrust, nations allied with their neighbors, vowing to protect each other if war ever erupted. In Room 6, a map of Europe in 1914 shows France, Britain, and Russia (the Allies) teaming up against Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Italy (the Central Powers). Meanwhile, the Ottoman Empire (Turkey and the Balkans) was breaking apart, creating a tense and unstable Western world. Europe was ready to explode, but the spark that would set it off had nothing to do with Germany or France.

Bang. On June 28, 1914, an Austrian archduke was shot to death (see video of the political mood, assassination, and mobilization). It happened in (what’s now) Bosnia—a region not very central to Europe (or even the Austrian Empire), but very politically charged. One by one, Europe’s nations were dragged into the regional dispute by their webs of alliances. All of Europe mobilized its troops. The 1914 stone on the floor is the first of the museum’s year-stones. The Great War had begun.

In September, German forces swarmed into France, hoping for a quick knockout blow. Germany brought its big guns (photo and miniature model of Big Bertha). The projection map shows how the armies tried to outflank each other along a 200-mile battlefront. As the Germans (brown arrows) zeroed in on Paris, the French (blue arrows) scrambled to send 6,000 crucial reinforcements, shuttled to the front lines in 670 Parisian taxis. The German tide was stemmed, and the two sides faced off, expecting to duke it out and get this war over quickly. It didn’t work out that way.

• The war continues upstairs.

By 1915, the two sides reached a stalemate, and they settled in to a long war of attrition—French and Britons on one side, Germans on the other. The battle line, known as the Western Front, snaked 450 miles across Europe from the North Sea to the Alps. For protection against flying bullets, the soldiers dug trenches, which soon became home—24 hours a day, 7 days a week—for millions of men.

Life in the trenches was awful—cold, rainy, muddy, disease-ridden—and, most of all, boring. Every so often, generals waved their swords and ordered their men “over the top” and into “no man’s land.” Armed with rifles and bayonets, they advanced into a hail of machine gun fire. In a number of battles, France lost 70,000 men in a single day. The “victorious” side often won only a few hundred yards of meaningless territory that was lost the next day after still more deaths.

The war pitted 19th-century values of honor, bravery, and chivalry against 20th-century weapons: grenades, machine guns, tanks, and gas masks. To shoot over the tops of trenches while staying hidden, they even invented crooked and periscope-style guns.

Besides the Western Front, the war extended elsewhere, including the colonies, where many natives (see their exotic uniforms) joined the armies of their “mother” countries. On the Eastern Front, Russia and Germany wore each other down. (Finally, the Russian people had enough; they killed their czar, brought the troops home, and fomented a revolution that put Communists in power.)

• Down a short hallway, enter...

By 1917, the Allied forces were beginning to outstrip the Central Powers, thanks to help from around the world. Britain drew heavily from its Commonwealth nations, such as Canada and Australia.

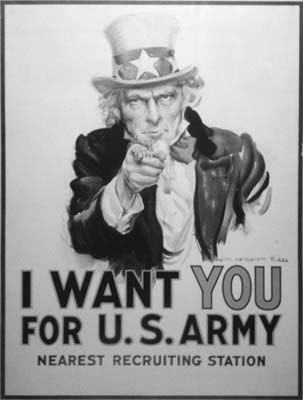

And when Uncle Sam said, “I Want You,” five million Americans answered the call to go “Over There” (in the words of a popular song) and fight the Germans. Though the US didn’t enter the War until April of 1917 (and was never an enormous military factor), its very presence was one more indication that the Allies seemed destined to prevail.

Under the command of French Marshal Ferdinand Foch, the Allies undertook a series of offensives that, by 1918, would prove decisive. At the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month (November 11, 1918), the guns fell silent. Allied Europeans celebrated with victory parades.

Weary soldiers returned home to be honored (painting of Arc de Triomphe parade). After four years of battle, the war had left 9.5 million dead and 21 million wounded (see plaster casts of disfigured faces). Three out of every four French soldiers had been either killed or wounded. A generation was lost.

The Treaty of Versailles (1919), signed in the Hall of Mirrors, officially ended the war. A map shows how it radically redrew Europe’s borders. Germany was punished severely, leaving it crushed, humiliated, stripped of crucial land, and saddled with demoralizing war debts. Marshal Foch prophetically said of the Treaty: “This is not a peace. It is an armistice for 20 years.”

France, one of the “victors,” was drained, trying to hang on to its prosperity and its colonial empire.

But by the 1930s—swamped by the Great Depression and a stagnant military (dummy on horseback)—France was reeling, unprepared for the onslaught of a retooled Germany seeking revenge.

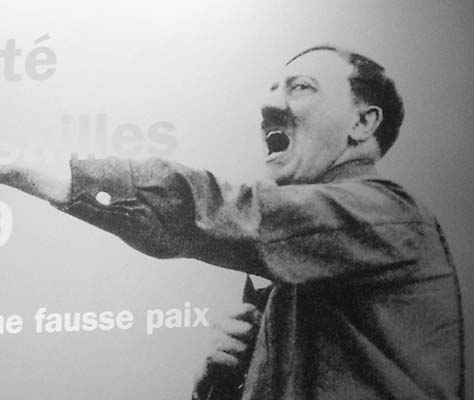

A photo of Adolf Hitler and a video presage the awful events that came next.

• World War II is covered directly across the hall, in the rooms marked 1939-1942.

World War II was the most destructive of earth’s struggles. In this exhibit, the war unfolds in photos, displays, and newsreels, with special emphasis on the French contribution. (You may not have realized that it was Charles de Gaulle who won the war for us.) The museum takes you from Germany’s quick domination (third floor), to the Allies turning the tide (second floor), to the final surrender (first floor). There are fine English descriptions throughout. Be ready—rooms come in rapid succession (and may no longer be numbered)—so treat this tour as an overview.

On September 1, 1939, Germany, under Adolf Hitler, invaded Poland, starting World War II. But in a sense the war had really begun in 1918, when the “war to end all wars” ground to a halt, leaving 9.5 million dead, Germany defeated, and France devastated (if victorious). For the next two decades, Hitler fed off German resentment over the Treaty of Versailles, which humiliated and ruined Germany.

After Hitler’s move into Poland, France and Britain mobilized. For the next six months, the two sides faced off, with neither actually doing battle—a tense time known to historians as the “phony” war (Drôle de Guerre).

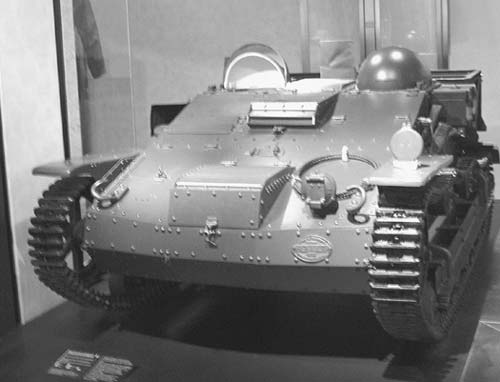

Then, in spring of 1940, came the Blitzkrieg (“lightning war”), and Germany’s better-trained and better-equipped soldiers and tanks (see turret) swept west through Belgium. France was immediately overwhelmed, and British troops barely escaped across the English Channel from Dunkirk. Within a month, Nazis were goose-stepping down the Champs-Elysées.

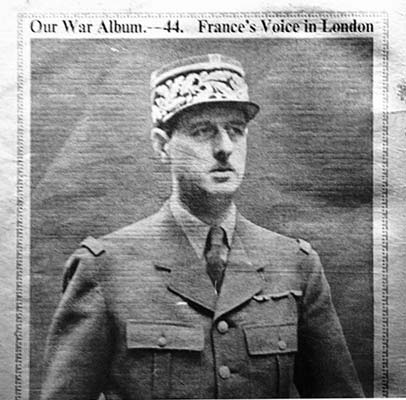

Just like that, virtually all of Europe was dominated by Fascists. During those darkest days, as France fell and Nazism spread across the Continent, one Frenchman—an obscure military man named Charles de Gaulle—refused to admit defeat. This 20th-century John of Arc had an unshakable belief in his mission to save France. De Gaulle (1890-1970) was born into a literate, upper-class family, raised in military academies, and became a WWI hero and POW. But when World War II broke out, he was still only a minor officer with limited political experience, who was virtually unknown to the French public.

After the invasion, de Gaulle escaped to London. From there he made inspiring speeches over the radio, beginning with a famous address broadcast on June 18, 1940. He slowly convinced a small audience of French expatriates that victory was still possible.

After France’s surrender, Germany ruled northern France, including Paris—see the photo of Hitler as a tourist at the Eiffel Tower. Hitler made a three-hour blitz tour of the city, including a stop at Napoleon’s Tomb. Afterward he said, “It was the dream of my life to be permitted to see Paris. I cannot say how happy I am to have that dream fulfilled today.”

The Nazis allowed the French to administer the south and the colonies (North Africa). This puppet government, centered in the city of Vichy, was right-wing and traditional, bowing to Hitler’s demands as he looted France’s raw materials and manpower for the war machine. (The movie Casablanca, set in Vichy-controlled Morocco, shows French officials following Nazi orders while French citizens defiantly sing “The Marseillaise.”)

Facing a “New Dark Age” in Europe, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill pledged, “We will fight on the beaches....We will fight in the hills. We will never surrender.”

In June of 1940, Germany mobilized to invade Britain across the Channel. From June to September, they paved the way, sending bombers—up to 1,500 planes a day—to destroy military and industrial sites. When Britain wouldn’t budge, Hitler concentrated on London and civilian targets. This was “The Blitz” of the winter of 1940, which killed 30,000 and left London in ruins. But Britain hung on, armed with newfangled radar, speedy Spitfires, and an iron will.

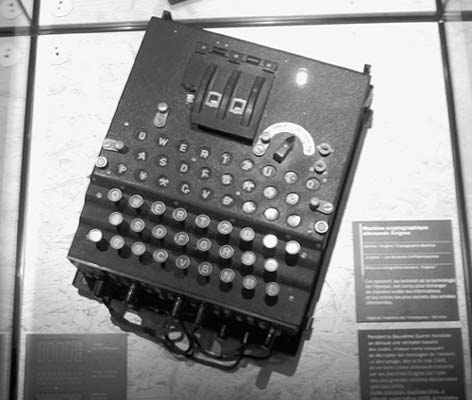

They also had the Germans’ secret “Enigma” code. The Enigma machine (in display case), with its set of revolving drums, allowed German commanders to scramble orders in a complex code that could be broadcast safely to their troops. The British (with crucial help from Poland) captured a machine, broke the code (in a project called “Ultra”), then monitored German airwaves. For the rest of the war, they had advance knowledge of many top-secret plans. (Occasionally, Britain even let Germany’s plans succeed—sacrificing its own people—to avoid suspicion.)

By spring of 1941, Hitler had given up any hope of invading the Isle of Britain. Churchill said of his people: “This was their finest hour.”

Perhaps hoping to one-up Napoleon, Hitler sent his state-of-the-art tanks speeding toward Moscow in June of 1941 (betraying his former ally Joseph Stalin). By winter, the advance had stalled at the gates of Moscow and was bogged down by bad weather and Soviet stubbornness. The Third Reich had reached its peak. From now on, Hitler would have to fight a two-front war. The French Renault tank (displayed) was downright puny compared to the big, fast, high-caliber German Panzer. This war was often a battle of factories, to see who could produce the latest technology fastest and in the greatest numbers. And what nation might have those factories...?

On December 7, 1941, “a date which will live in infamy” (as US President Franklin D. Roosevelt put it), Japanese planes made a sneak attack on the US base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, and destroyed the pride of the Pacific fleet in two hours.

The US quickly entered the fray against Japan and her ally, Germany. In two short years, America had gone from isolationist observer to supplier of Britain’s arms to full-blown war ally against fascism. The US now faced a two-front war—in Europe against Hitler, and in Asia against Japan’s imperialist conquest of China, Southeast Asia, and the South Pacific.

America’s first victory came when Japan tried a sneak attack on the US base at Midway Island (June 3, 1942). This time—thanks to the Allies who had cracked the Enigma code—America had the aircraft carrier USS Enterprise (see model) and two of her buddies lying in wait. In five minutes, three of Japan’s carriers (with valuable planes) were mortally wounded, their major attack force was sunk, and Japan and the US were dead even, settling in for a long war of attrition.

Though slow to start, America eventually had an army of 16 million strong, 80,000 planes, the latest technology, $250 million a day, unlimited raw materials, and a population of Rosie the Riveters fighting for freedom to a boogie-woogie beat.

• Continue downstairs to the second floor.

(See “Army Museum & Napoleon’s Tomb” map, here.)

In 1942, the Continent was black with fascism, and Japan was secure on a distant island. The Allies had to chip away on the fringes.

German U-boats (short for Unterseeboot) and battleships such as the Bismarck patrolled Europe’s perimeter, where they laid spiky mines and kept America from aiding Britain. (Until long-range transport planes were invented near war’s end, virtually all military transport was by ship.) The Allies traveled in convoys with air cover, used sonar and radar, and dropped depth charges, but for years they endured the loss of up to 60 ships per month.

• Don’t bypass Room 14, tucked in the corner.

Three crucial battles in the autumn of 1942 put the first chink in the Fascist armor. Off the east coast of Australia, 10,000 US Marines (see kneeling soldier in glass case 14D) took an airstrip on Guadalcanal, while 30,000 Japanese held the rest of the tiny, isolated island. For the next six months, the two armies were marooned together, duking it out in thick jungles and malaria-infested swamps while their countries struggled to reinforce or rescue them. By February of 1943, America had won and gained a crucial launch pad for bombing raids.

A world away, German tanks under General Erwin Rommel rolled across the vast deserts of North Africa. In October of 1942, a well-equipped, well-planned offensive by British General Bernard (“Monty”) Montgomery attacked at El-Alamein, Egypt, with 300 tanks. (See British tank soldier with headphones.) Monty drove “the Desert Fox” west into Tunisia for the first real Allied victory against the Nazi Wehrmacht war machine.

Then came Stalingrad. (See kneeling Soviet soldier in heavy coat.) In August of 1942, Germany attacked the Soviet city, an industrial center and gateway to the Caucasus oil fields. By October, the Germans had battled their way into the city center and were fighting house-to-house, but their supplies were running low, the Soviets wouldn’t give up, and winter was coming. The snow fell, their tanks had no fuel, and relief efforts failed. Hitler ordered them to fight on through the bitter cold. On the worst days, 50,000 men died. (By comparison, America lost a total of 58,000 in Vietnam.) Finally, on January 31, 1943, the Germans surrendered, against Hitler’s orders. The six-month totals? Eight hundred thousand German and other Axis soldiers dead, 1.1 million Soviets dead. The Russian campaign put hard miles on the German war machine.

Also in 1942, the Allies began long-range bombing of German-held territory, including saturation bombing of civilians. It was global war and total war.

Winston Churchill and US President Franklin D. Roosevelt (see photo with de Gaulle), two of the 20th century’s most dynamic and strong-willed statesmen, decided to attack Hitler indirectly by invading Vichy-controlled Morocco and Algeria. On November 8, 1942, 100,000 Americans and British—under the joint command of an unknown, low-key problem-solver named General Dwight (“Ike”) Eisenhower—landed on three separate beaches (including Casablanca). More than 120,000 Vichy French soldiers, ordered by their superiors to defend the Fascist cause, confronted the Allies and...gave up. (See display of some standard-issue weapons: Springfield rifle, Colt 45, Thompson machine gun, hand grenade.)

The Allies moved east, but bad weather, inexperience, and the powerful Afrika Korps under Rommel stopped them in Tunisia. But with flamboyant General George S. (“Old Blood-and-Guts”) Patton punching from the west, and Monty pushing from the south, they captured the port town of Tunis on May 7, 1943. The Allies now had a base from which to retake Europe.

Inside occupied France, other ordinary heroes fought the Nazis—the underground Resistance. Bakers hid radios within loaves of bread to secretly contact London. Barmaids passed along tips from tipsy Nazis. Communists in black berets cut telephone lines. Farmers hid downed airmen in haystacks. Housewives spread news from the front with their gossip. Printers countered Nazi propaganda with pamphlets.

Jean Moulin (see photo in exhibit), de Gaulle’s assistant, secretly parachuted into France and organized these scattered heroes into a unified effort. In May of 1943, Moulin was elected chairman of the National Council of the Resistance. A month later, he was arrested by the Gestapo (Nazi secret police), imprisoned, tortured, and sent to Germany, where he died in transit. Still, Free France now had a (secret) government again, rallied around de Gaulle, and was ready to take over when liberation came. (See additional Resistance exhibits in Room 20.)

Monty, Patton, and Ike certainly were heroes, but the war was won on the Eastern Front by Soviet grunts, who slowly bled Germany dry. Maps show the shifting border of the Eastern Front.

On July 10, 1943, the assault on Hitler’s European fortress began. More than 150,000 Americans and British sailed from Tunis and landed on the south shore of Sicily. (See maps and video clips of the campaigns.) Speedy Patton and methodical Monty began a “horse race” to take the city of Messina (the US won the friendly competition by a few hours). They met little resistance from 300,000 Italian soldiers, and were actually cheered as liberators by the Sicilian people. Their real enemies were the 50,000 German troops sent by Hitler to bolster his ally Benito Mussolini. By September, the island was captured. On the mainland, Mussolini was arrested by his own people, and Italy surrendered to the Allies. Hitler quickly poured troops into Italy (and reinstalled Mussolini) to hold off the Allied onslaught.

In early September, the Allies launched a two-pronged landing onto the beaches of southern Italy. Finally, after four long years of war, free men set foot on the European continent. Lieutenant General Mark Clark, leading the slow, bloody push north to liberate Rome, must have been reminded of the French trenches he’d fought in during World War I. As in that bloody war, the fighting in Italy was a war of attrition, fought on the ground by foot soldiers and costing many lives for just a few miles.

In January of 1944, the Germans dug in between Rome and Naples at Monte Cassino, a rocky hill topped by the monastery of St. Benedict. Thousands died as the Allies tried inching up the hillside. In frustration, the Allies air-bombed the historic Monte Cassino monastery to smithereens, killing many noncombatants...but no Germans, who dug in deeper. Finally, after four months of vicious, sometimes hand-to-hand combat by the Allies (Americans, Brits, Free French, Poles, Italian partisans, Indians, etc.), a band of Poles stormed the monastery, and the German back was broken.

Meanwhile, 50,000 Allies had landed near Rome at Anzio and held the narrow beachhead for months against massive German attacks. When reinforcements arrived, Allied troops broke out and joined the two-pronged assault on the capital. Without a single bomb threatening its historic treasures, Rome fell on June 4, 1944.

• Room 23 (with chairs) shows a film on...

Three million Allies and six million tons of material were massed in England in preparation for the biggest fleet-led invasion in history—across the Channel to France, then eastward to Berlin. The Germans, hunkered down in northern France, knew an invasion was imminent, but the Allies kept the details top secret. On the night of June 5, 150,000 soldiers boarded ships and planes without knowing where they were headed until they were under way. Each one carried a note from General Eisenhower: “The tide has turned. The free men of the world are marching together to victory.”

At 6:30 a.m. on June 6, 1944, Americans spilled out of troop transports into the cold waters off a beach in Normandy, code-named Omaha. The weather was bad, seas were rough, and the prep bombing had failed. The soldiers, many seeing their first action, were dazed and confused. Nazi machine guns pinned them against the sea. Slowly, they crawled up the beach on their stomachs. A thousand died. The survivors held on until the next wave of transports arrived.

All day long, Allied confusion did battle with German indecision; the Nazis never really counterattacked, thinking D-Day was just a ruse, instead of the main invasion. By day’s end, the Allies had taken several beaches along the Normandy coast and began building artificial harbors, providing a tiny port-of-entry for the reconquest of Europe. The stage was set for a quick and easy end to the war. Right.

• Go downstairs to the...

(See “Army Museum & Napoleon’s Tomb” map, here.)

Through June, the Allies (mostly Americans) secured Normandy by taking bigger ports (Cherbourg and Caen) and amassing troops and supplies for the assault on Germany. In July they broke out and sped eastward across France, with Patton’s tanks covering up to 40 miles a day. They had “Jerry” on the run.

On France’s Mediterranean coast, American troops under General Alexander Patch landed near Cannes (see parachute photo), took Marseilles, and headed north to meet with Patton.

French Resistance guerrilla fighters helped reconquer France from behind the lines. (Don’t miss the folding motorcycle in its parachute case.) The liberation of Paris was started by a Resistance attack on a German garrison.

As the Allies marched on Paris, Hitler ordered his officers to torch the city—but they sanely disobeyed and prepared to surrender. On August 26, 1944, General Charles de Gaulle walked ramrod-straight down the Champs-Elysées, followed by Free French troops and US GIs passing out chocolate and Camels. Two million Parisians went crazy.

The quick advance from the west through France, Belgium, and Luxembourg bogged down at the German border in autumn of 1944. Patton outstripped his supply lines, a parachute invasion of Holland (the Battle of Arnhem) was disastrous, and bad weather grounded planes and slowed tanks.

On December 16, the Allies met a deadly surprise. An enormous, well-equipped, energetic German army appeared from nowhere, punched a “bulge” deep into Allied lines, and demanded surrender. General Anthony McAuliffe sent a one-word response—“Nuts!”—and the momentum shifted. The Battle of the Bulge was Germany’s last great offensive.

The Germans retreated across the Rhine River, blowing up bridges behind them. The last bridge, at Remagen, was captured by the Allies just long enough for them to cross and establish themselves on German soil. Soon US tanks were speeding down the autobahns and Patton could wire the good news back to Ike: “General, I have just pissed in the Rhine.”

Soviet soldiers did the dirty work of taking fortified Berlin by launching a final offensive in January of 1945, and surrounding the city in April. German citizens fled west to surrender to the more-benevolent Americans and Brits. Hitler, defiant to the end, hunkered in his underground bunker. (See photo of ruined Berlin.)

On April 28, 1945, Mussolini and his girlfriend were killed and hung by their heels in Milan. Two days later, Adolf Hitler and his new bride, Eva Braun, avoided similar humiliation by committing suicide (pistol in mouth), and having their bodies burned beyond recognition. Germany formally surrendered on May 8, 1945.

Lest anyone mourn Hitler or doubt this war’s purpose, gaze at photos from Germany’s concentration camps. Some camps held political enemies and prisoners of war, including two million French. Others were expressly built to exterminate peoples considered “genetically inferior” to the “Aryan master race”—particularly Jews, Gypsies, homosexuals, and the mentally ill. The criminals who perpetrated these acts were tried and sentenced in an international court—the first of its kind—held in Nuremburg, Germany.

Often treated as an afterthought, the final campaign against Japan was a massive American effort, costing many lives, but saving millions of others from Japanese domination.

Japan was an island bunker surrounded by a vast ring of fortified Pacific islands. America’s strategy was to take one island at a time, “island-hopping” until close enough for B-29 Superfortress bombers to attack Japan itself. The war spread across thousands of miles. In a new form of warfare, ships carrying planes led the attack and prepared tiny islands for troops to land and build an airbase. While General Douglas MacArthur island-hopped south to retake the Philippines (“I have returned!”), others pushed north toward Japan.

In February of 1945, Marines landed on Iwo Jima, a city-size island-volcano close enough to Japan (800 miles) to launch air raids. Twenty thousand Japanese had dug in on the volcano’s top and were picking off the advancing Americans. On February 23, several US soldiers raised the Stars and Stripes on the mountain (that famous photo), which inspired their mates to victory, at a cost of nearly 7,000 men.

On March 9, Tokyo was firebombed, and 90,000 were killed. Japan was losing, but a land invasion would cost hundreds of thousands of lives. The Japanese had a reputation for choosing death over the shame of surrender—they even sent bomb-laden “kamikaze” planes on suicide missions.

America unleashed its secret weapon, an atomic bomb (originally suggested by German-turned-American Albert Einstein). On August 6, a B-29 dropped one (named “Little Boy,” see the replica dangling overhead) on the city of Hiroshima and instantly vaporized 100,000 people and four square miles. Three days later, a second bomb fell on Nagasaki. The next day, Emperor Hirohito unofficially surrendered. The long war was over, and US sailors returned home to kiss their girlfriends in public places.

The death toll for World War II (September 1939-August 1945) totaled 80 million soldiers and civilians. The Soviet Union lost 26 million, China 13 million, France 580,000, and the US 340,000.

World War II changed the world, with America emerging as the dominant political, military, and economic superpower. Europe was split in two. The western half recovered, with American aid. The eastern half remained under Soviet occupation. For 45 years, the US and the Soviet Union would compete—without ever actually doing battle—in a “Cold War” of espionage, propaganda, and weapons production that stretched from Korea to Cuba, from Vietnam to the moon.

• Return to the large Courtyard of Honor, where Napoleon honored his troops, Dreyfus had his sword broken, and de Gaulle once kissed Churchill. Two exhibits—one in the east wing and one in the west wing—flank the courtyard. The west wing contains arms and armor from the 13th to 17th century (see here for a short description). The east wing houses an exhibit that takes you...

(See “Army Museum & Napoleon’s Tomb” map, here.)

• The exhibit is located in the center of the east wing off the courtyard. The main collection is upstairs on the second floor.

This display traces the evolution of uniforms and weapons through France’s glory days, with the emphasis on Napoleon Bonaparte. As you circle the second floor, the exhibit unfolds chronologically in four parts: the Ancien Régime (Louis XIV, XV, and XVI), the Revolution, the First Empire (Napoleon), and the post-Waterloo world. Many (but not all) exhibits have some English information.

The following is not a room-by-room tour—this is more a museum for browsing. I’ve highlighted a handful of the (many) exhibits you might see. Explore, and let the museum surprise you.

Louis XIV unified the army as he unified the country, creating the first modern nation-state with a military force. You’ll see how gunpowder was quickly turning swords, pikes, and lances to pistols, muskets, and bayonets. Uniforms became more uniform, and everyone got a standard-issue flintlock.

At the end of the hall, a display case has some amazingly big and odd-shaped rifles. Nearby, a projection screen (with English commentary) shows a re-enactment of the Battle of Fontenoy (in present-day Belgium) in 1745. Watch how, at the turning point in the battle, the British troops (in red) cluster into a dense, square column and penetrate the French line of defenses. But the French swarm around them on three sides, then drive them back, affirming French superiority on the Continent.

• Turn the corner and enter...

Room 13 features the American War of Independence. You’ll see the sword (épée) of the French aristocrat Marquis de La Fayette, who—full of revolutionary fervor—sailed to America, where he took a bullet in the leg and fought alongside George Washington.

After France underwent its own Revolution, the king’s Royal Army became the people’s National Guard, protecting their fledgling democracy from Europe’s monarchies while spreading revolutionary ideas by conquest. A young, relatively obscure officer distinguished himself on the battlefield and quickly rose through the ranks—Napoleon Bonaparte.

Midway down the hall, find the large model of the Battle of Lodi in 1796. The French and Austrians faced off on opposite sides of a northern Italian river, each trying to capture a crucial bridge. The model shows the dramatic moment when the French cavalry charged across the bridge, overpowering the exhausted Austrians. Stories spread that it was the brash General Bonaparte himself who personally sighted the French cannons on the enemy—normally the job of a lesser officer. It turned the tide of battle and earned him a reputation and a nickname, “The Little Corporal.”

Rooms 19-21 chronicle Napoleon as emperor. While pledging allegiance to Revolutionary ideals of democracy, Napoleon staged a coup and soon ruled France as a virtual dictator. The museum displays General Bonaparte’s hat, sword, and medals. In 1804, Napoleon donned royal robes and was crowned Emperor. The famous portrait by J. A. D. Ingres shows him at the peak of his power, stretching his right arm to supernatural lengths. The ceremonial collar and medal he wears in the painting are displayed nearby, as are an eagle standard and Napoleon’s elaborate saddle.

Continue to the end of Hall 2 to find Napoleon’s beloved Arabian horse. Le Vizir weathered many a campaign with Napoleon, grew old with him in exile, and now stands stuffed and proud.

Ambitious Napoleon plunged France into draining wars against all of Europe. In Room 29 (midway down the hall), you’ll see Napoleon’s tent and bivouac equipment: a bed with mosquito netting, a director’s chair, his overcoat and pistols, and a table that you can imagine his generals hunched over as they made battle plans.

Napoleon’s plans to dominate Europe ended with disastrous losses when he attempted to invade Russia. The rest of Europe ganged up on France, and in 1814 Napoleon was forced to abdicate. Room 35 shows a portrait of a crestfallen Napoleon, now replaced by King Louis XVIII (whose bust stands opposite). Napoleon spent a year in exile on the isle of Elba. In March of 1815, he escaped, returned to France, rallied the army, and prepared for one last hurrah.

• Turning the corner into Hall 4, you run right into what Napoleon did—Waterloo.

A projection screen maps the course of the history-changing Battle of Waterloo, fought on the outskirts of Brussels, June 15-19, 1815.

On June 18, 72,000 French (the blue squares) faced off against the allied armies of 68,000 British-Dutch under Wellington (red and yellow) and 45,000 Prussians under Blücher (purple). Napoleon’s only hope was to split the two armies and defeat them individually.

First, Napoleon’s Marshal Ney advances on the British-Dutch, commanded by the Prince of Orange. Then the French attack the Prussians on the right. They rout the Prussians, driving them north. Napoleon’s strategy is working. Now he prepares to finish Wellington off.

On the morning of June 18, Wellington hunkers down atop a ridge at Waterloo. Napoleon waits two hours to attack, to let the field dry—some say it was his fatal mistake. At 11:30, Napoleon fakes to the left, then punches hard at the center. Wellington holds firm. Meanwhile, the Prussians have regrouped and begun advancing from the right. Napoleon must now fight both armies, on two flanks—Wellington on the ridge, the Prussians to the right.

Caught in a pincer, Napoleon has no choice but to send in his elite troops, the Imperial Guard, who have never been defeated. The British surprise the Guard in a cornfield, and Wellington swoops down from the ridge, routing the French. By nightfall, the British and Prussian armies have come together, and Napoleon’s reign of glory is over.

Napoleon was sent into exile on St. Helena. Once the most powerful man in the world, Napoleon spent his final years as a lonely outcast suffering from ulcers, dressed in his nightcap and slippers, and playing chess, not war.

• From here head downstairs, following the signs to the...

Finish at this engaging memorial, the “Historial Charles de Gaulle,” which brings France’s history of war into the modern age. The exhibit leads you through the life of the greatest figure in 20th-century French history. After helping to defeat Hitler, de Gaulle went on to lead the nation for two decades as its president. The multimedia displays lead you from de Gaulle’s youth, through two world wars, to the rebuilding of France during his presidency, and the social unrest of the 1960s that toppled him.