From Sacré-Cœur to the Moulin Rouge

Church of St. Pierre-de-Montmartre

Church of St. Pierre-de-Montmartre

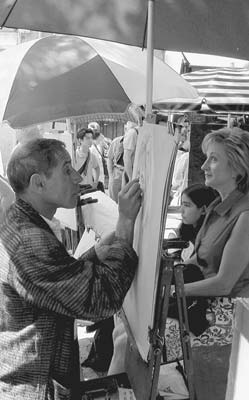

Place du Tertre—Bohemian Montmartre

Place du Tertre—Bohemian Montmartre

Montmartre Museum and Satie’s House

Montmartre Museum and Satie’s House

Le Bateau-Lavoir (Picasso’s Studio)

Le Bateau-Lavoir (Picasso’s Studio)

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec’s House

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec’s House

Stroll along the hilltop of Butte Montmartre amid traces of the many people who’ve lived here over the years—monks stomping grapes (1200s), farmers grinding grain in windmills (1600s), dust-coated gypsum miners (1700s), Parisian liberals (1800s), Modernist painters (1900s), and all the struggling artists, poets, dreamers, and drunkards who came here for cheap rent, untaxed booze, rustic landscapes, and cabaret nightlife. In the jazzy 1920s, the neighborhood became the haunt of American GIs and expat African Americans. Today it’s a youthful neighborhood in transition—both slightly seedy and extremely trendy.

Many tourists make the almost obligatory trek to the top of Paris’ Butte Montmartre, eat an overpriced crêpe, and marvel at the view—but most miss out on the neighborhood’s charm and history. Both are uncovered in this stroll. We’ll start at the gleaming Sacré-Cœur Basilica, wander through the hilltop village, browse affordable art, ogle the Moulin Rouge nightclub, and catch echoes of those who once partied to a bohemian rhapsody during the belle époque.

(See “West Paris” map, here.)

Length of This Walk: Allow more than two hours for this two-mile uphill/downhill walk.

When to Go: To minimize crowds at Sacré-Cœur, come on a weekday or by 9:30 on a weekend. Sunny weekends are the busiest—especially on Sunday, when Montmartre becomes a pedestrian-only zone and most shops stay open. On Friday afternoon, Place d’Anvers hosts a small open-air food market (15:00-20:00, at far side of square). If crowds don’t get you down, come for the sunset and stay for dinner. This walk is best under clear skies, when views are sensational. Regardless of when you go, prepare for more seediness—particularly near Place Pigalle and Place d’Anvers—than you’re accustomed to in Paris.

Getting There: This walk begins at Métro stop Anvers. Other stops nearby include Abbesses and Pigalle. (Avoid the seedy Métro station Barbès.)

You have several options to avoid climbing the hill to Sacré-Cœur: Take the funicular (covered in our walk), which runs near the Anvers Métro and costs one Métro ticket. Alternatively, from Place Pigalle, you could catch the “Montmartrobus,” a city bus that drops you right by Sacré-Cœur (at the Funiculaire stop, costs one Métro ticket, 4/hour). A taxi from the Seine or the Bastille to Sacré-Cœur costs about €15 (€20 at night).

Scam Alert: At Sacré-Cœur and in the areas around the Pigalle and Anvers Métro stations, beware of pickpockets, smartphone snatchings, the “found ring” scam, and the “friendship bracelet” scam; see here.

Sacré-Cœur: Church—free, daily 6:00-22:30, last entry at 22:15; dome—€6, not covered by Museum Pass, daily May-Sept 9:00-19:00, Oct-April 9:00-17:00.

Church of St. Pierre-de-Montmartre: Free, Sat-Thu 8:45-19:00, Fri 8:45-17:00.

Dalí Museum (L’Espace Dalí): €11.50, not covered by Museum Pass, daily 10:00-18:00, July-Aug until 20:00, audioguide-€3, 11 Rue Poulbot.

Montmartre Museum: €9, not covered by Museum Pass, daily 10:00-18:00, last entry 30 minutes before closing, price includes good audioguide, 12 Rue Cortot.

Services: As you face Sacré-Cœur, WCs are down the stairs to the right (free, 10:00-18:15). Others are in the Square Suzanne Buisson park (north of #16 on the tour), the Montmartre Museum, in an automated cabin at the base of the funicular (long lines), in the souvenir shop at the top of the funicular (€1), and any cafés you patronize.

Eating: You’ll find peaceful, picnic-ready benches all along this walk as well as a patch of grass in the park on the backside of the basilica. Good sandwiches are available along Rue Norvins (in the heart of Montmartre). See here of the Eating in Paris chapter for restaurant recommendations, including L’Eté en Pente Douce and other eateries along Rue Lepic and Rue des Abbesses.

Starring: Cityscape views, Sacré-Cœur, postcard scenes brought to life, a charming market street, and boring buildings where interesting people once lived.

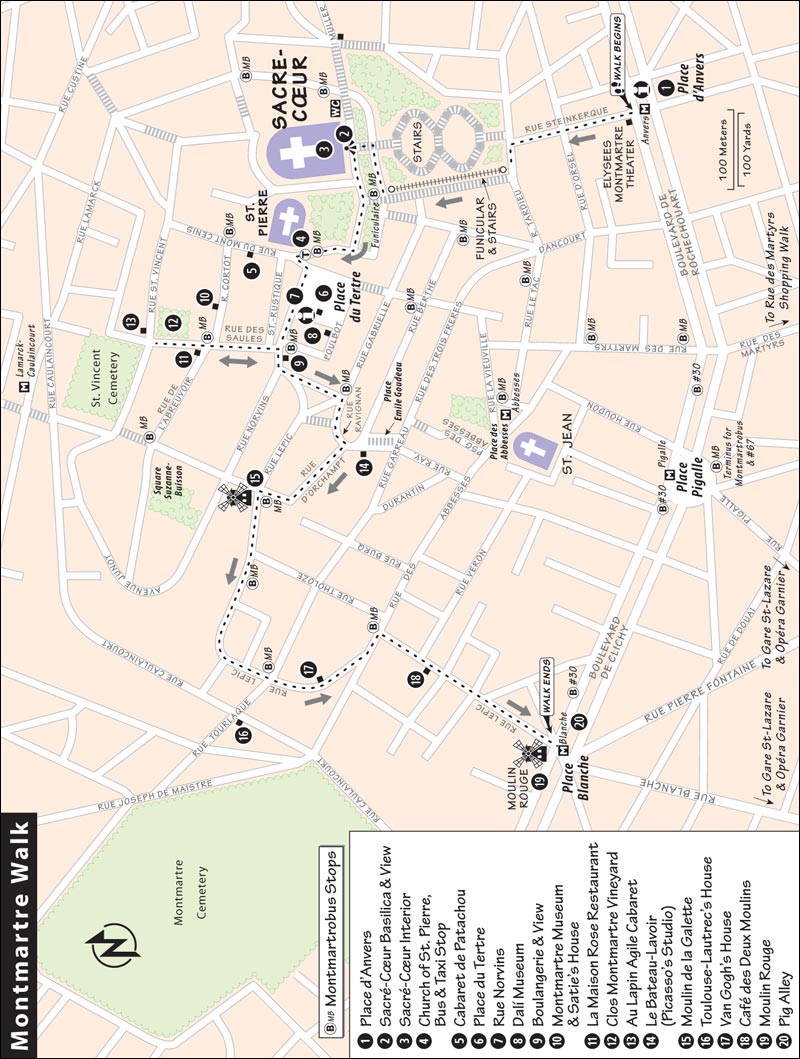

(See “Montmartre Walk” map, here.)

• To reach Sacré-Cœur by Métro, get off at Métro stop Anvers. Surface through one of the original Art Nouveau “Métropolitain” Métro entrances.

Place d’Anvers

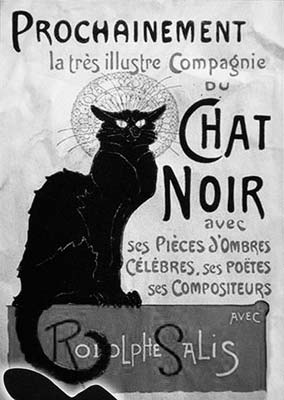

Place d’AnversThe Elysées Montmartre theater across the street is the oldest cancan dance hall in Paris. More recently, it’s been used as a rowdy dance club and concert hall, signaling this area’s transition. (The famous Chat Noir—or Black Cat—cabaret was a half-block down at #84.) Historically, people have moved to this neighborhood for cheap rents—and though it still feels neglected, urban gentrification is under way, as young professionals restore dilapidated apartments, hotels renovate for a more upscale clientele, and rents increase. A TI kiosk is a few steps to your left (daily 10:00-18:00).

You’re standing on Boulevard de Rochechouart, where a wall once separated Montmartre from Paris (boulevard literally means “road that replaced a wall”). Let’s take a walk on the wild side.

• Walk two blocks up Rue de Steinkerque (the street to the right of Elysées Montmartre), through a low-rent gauntlet of cheap clothing and souvenir stores. You’ll reach a grassy park way below the white Sacré-Cœur church. The terraced hillside was once dotted with openings to gypsum mines, the source of the white “plaster of Paris” that plastered Paris’ buildings for centuries.

Hike up to the church, or ride the funicular (station to your left, costs one Métro ticket, closes periodically for maintenance). At the top, find a good viewing spot at the steps of the church.

Sacré-Cœur Basilica and View

Sacré-Cœur Basilica and ViewFrom Paris’ highest natural point (420 feet), the City of Light fans out at your feet. Pan from left to right. The long triangular roof on your left is the Gare du Nord train station. The blue-and-red Pompidou Center is straight ahead, and the skyscrapers in the distance define the southern limit of central Paris. Next is the domed Panthéon, atop Paris’ other (and far smaller) butte. Then comes the modern Montparnasse Tower, and finally (if you’re in position to see this far to the right), the golden dome of Les Invalides.

Now face the church. The Sacré-Cœur (Sacred Heart) Basilica’s exterior, with its onion domes and bleached-bone pallor, looks ancient, but was finished only a century ago by Parisians humiliated by German invaders. Otto von Bismarck’s Prussian army laid siege to Paris for more than four months in 1870. Things got so bad for residents that urban hunting for dinner (to cook up dogs, cats, and finally rats) became accepted behavior. Convinced they were being punished for the country’s liberal sins, France’s Catholics raised money to build the church as a “praise the Lord anyway” gesture. The church was a kind of penitence by the French: Many were disgusted that in 1871 their government actually shot its own citizens, the Communards, who held out here on Montmartre after the French leadership surrendered to the Prussians (the Communards’ monument is in Père Lachaise Cemetery—see here).

The five-domed, Roman-Byzantine-looking basilica took 44 years to build (1875-1919). It stands on a foundation of 83 pillars sunk 130 feet deep, necessary because the ground beneath was honeycombed with gypsum mines. The exterior is laced with gypsum, which whitens with age.

• Go inside.

Sacré-Cœur Interior

Sacré-Cœur Interior(See “Sacré-Coeur” map, here.)

Crowd flow permitting, pause near the entrance and take in the nave.

View of the Nave: In the impressive mosaic high above the altar, a 60-foot-tall Christ exposes his sacred heart, burning with love and compassion for humanity. Joining him are a dove representing the Holy Spirit and God the Father high above. Christ is flanked by biblical figures on the left (including St. Peter, kneeling) and French figures on the right (a kneeling Joan of Arc in her trademark armor). As you get closer, you’ll see other French figures: clergymen (who offer a model of this church to the Lord), government leaders (in business suits), and French saints (including St. Bernard, above, with his famous dog, and St. Louis, with the crown of thorns). Remember, the church was built by a French populace recently humbled by a devastating war. At the base of the mosaic is the National Vow of the French people begging God’s forgiveness: “Sacritissimo Cordi Jesu Gallia poenitens et devota...,” which means: “To the Sacred Heart of Jesus, we are penitent and devoted.” Right now, in this church, at least one person is praying for Christ to be understanding of the world’s sins—part of a tradition that’s been carried out here, day and night, 24/7, since Sacré-Cœur’s completion.

View of the Nave: In the impressive mosaic high above the altar, a 60-foot-tall Christ exposes his sacred heart, burning with love and compassion for humanity. Joining him are a dove representing the Holy Spirit and God the Father high above. Christ is flanked by biblical figures on the left (including St. Peter, kneeling) and French figures on the right (a kneeling Joan of Arc in her trademark armor). As you get closer, you’ll see other French figures: clergymen (who offer a model of this church to the Lord), government leaders (in business suits), and French saints (including St. Bernard, above, with his famous dog, and St. Louis, with the crown of thorns). Remember, the church was built by a French populace recently humbled by a devastating war. At the base of the mosaic is the National Vow of the French people begging God’s forgiveness: “Sacritissimo Cordi Jesu Gallia poenitens et devota...,” which means: “To the Sacred Heart of Jesus, we are penitent and devoted.” Right now, in this church, at least one person is praying for Christ to be understanding of the world’s sins—part of a tradition that’s been carried out here, day and night, 24/7, since Sacré-Cœur’s completion.

• Start shuffling clockwise around the church. Near the entrance, find the white...

Statue of St. Thérèse: Follow Thérèse’s gaze to a pillar with a plaque (“L’an 1944...”). The plaque’s map shows where, on April 21, 1944, 13 bombs fell on Montmartre in an Allied air raid during World War II—all in a line, all near the church—killing no one. This fueled local devotion to the Sacred Heart and to this church.

Statue of St. Thérèse: Follow Thérèse’s gaze to a pillar with a plaque (“L’an 1944...”). The plaque’s map shows where, on April 21, 1944, 13 bombs fell on Montmartre in an Allied air raid during World War II—all in a line, all near the church—killing no one. This fueled local devotion to the Sacred Heart and to this church.

• Continue up the side aisles, and find a...

Scale Model of the Church: It shows the church from the long side (you’d enter at left). This early-version model doesn’t accurately reflect the finished product, but it’s close. You see its central dome surrounded by smaller domes, and the tower. The “Byzantine” style is clear in the onion domes and in the arches—heavy horseshoe arches atop slender columns. The church is built of large rectangular blocks (just look around you), with no attempt to plaster over the cracks/lines in between.

Scale Model of the Church: It shows the church from the long side (you’d enter at left). This early-version model doesn’t accurately reflect the finished product, but it’s close. You see its central dome surrounded by smaller domes, and the tower. The “Byzantine” style is clear in the onion domes and in the arches—heavy horseshoe arches atop slender columns. The church is built of large rectangular blocks (just look around you), with no attempt to plaster over the cracks/lines in between.

• Continue along, looking to the right at...

Colorful Mosaics of the Stations of the Cross: Pause to rub St. Peter’s bronze foot and look up to the heavens.

Colorful Mosaics of the Stations of the Cross: Pause to rub St. Peter’s bronze foot and look up to the heavens.

• Continue your circuit around the church.

Stained-Glass Windows: Because the church’s original stained-glass windows were broken by the concussion of WWII bombs, all the glass you see is post-1945.

Stained-Glass Windows: Because the church’s original stained-glass windows were broken by the concussion of WWII bombs, all the glass you see is post-1945.

• As you approach the entrance you’ll walk straight toward three stained-glass windows dedicated to...

Joan of Arc (Jeanne d’Arc, 1412-1431): See the teenage girl as she hears the voice of the Archangel Michael (right panel, at bottom) and later (above) as she takes up the Archangel’s sword. Next, she kneels to take communion (central panel, bottom), then kneels before the bishop to tell him she’s been sent by God to rally France’s soldiers and save Orléans from English invaders (central panel, top). However, French forces allied with England arrest her, and she’s burned at the stake as a heretic (left panel), dying with her eyes fixed on a crucifix and chanting, “Jesus, Jesus, Jesus...”

Joan of Arc (Jeanne d’Arc, 1412-1431): See the teenage girl as she hears the voice of the Archangel Michael (right panel, at bottom) and later (above) as she takes up the Archangel’s sword. Next, she kneels to take communion (central panel, bottom), then kneels before the bishop to tell him she’s been sent by God to rally France’s soldiers and save Orléans from English invaders (central panel, top). However, French forces allied with England arrest her, and she’s burned at the stake as a heretic (left panel), dying with her eyes fixed on a crucifix and chanting, “Jesus, Jesus, Jesus...”

• Exit the church. A public WC is to your left, down 50 steps. To your right is the entrance to the church’s...

Dome and Crypt: For an unobstructed panoramic view of Paris, climb 260 feet (300 steps) up the tight and claustrophobic spiral stairs to the top of the dome (especially worthwhile if you have kids with excess energy). The crypt is just a big, empty basement.

Dome and Crypt: For an unobstructed panoramic view of Paris, climb 260 feet (300 steps) up the tight and claustrophobic spiral stairs to the top of the dome (especially worthwhile if you have kids with excess energy). The crypt is just a big, empty basement.

• Leaving the church, turn right and walk west along the ridge, following tree-lined Rue Azaïs. At Rue St. Eleuthère, turn right and walk uphill a block to the Church of St. Pierre-de-Montmartre (at top on right). The small square in front of the church has a convenient taxi stand and a bus stop for the Montmartrobus to and from Place Pigalle (bus costs one Métro ticket).

You’re in the heart of Montmartre, by Place du Tertre. A sign for the Cabaret de la Bohème reminds visitors that in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, this was the world capital of bohemian life. But before we plunge into that tourist-filled scene, let’s see where this whole Montmartre thing first got its start—in a nearby church.

Church of St. Pierre-de-Montmartre

Church of St. Pierre-de-MontmartreThis church was the center of Montmartre’s initial claim to fame, a sprawling abbey of Benedictine monks and nuns. The church is one of Paris’ oldest (1147). Look down the nave at the Gothic arches and stained glass. The church was founded by King Louis VI and his wife, Adelaide. (Some say Dante prayed here.)

Find Adelaide’s white slab tombstone (pierre tombale) midway down on the left wall. Older still are the four gray columns—two flank the entrance, and two others are behind the altar in the apse (they’re the two darker columns supporting either side of the central arch). These may have stood in a temple of Mercury or Mars in Roman times. The name “Montmartre” comes from the Roman “Mount of Mars,” though later generations—thinking of their beheaded patron St. Denis—preferred a less pagan version, “Mount of Martyrs.”

And speaking of martyrs, continue clockwise around the church to find Montmartre’s most famous martyr. Near the entrance is a white statue of St. Denis, holding his head in his hands. This early Christian bishop was sentenced to death by the Romans for spreading Christianity. As they marched him up to the top of Montmartre to be executed, the Roman soldiers got tired and just beheaded him near here. But Denis popped right up, picked up his head, and carried on another three miles north before he finally died.

Next to Denis, the statue of “Notre Dame de Montmartre” marks a modern miracle—how the Virgin spared the neighborhood from the WWII bombs of April 21, 1944.

Before leaving, rub St. Peter’s toe (again), look up, and ask for déliverance from the tourist mobs outside.

• Now step back outside. Before entering the crowded Place du Tertre, get a quick taste of the area by making a short detour to the right down Rue du Mont-Cenis. These days it’s lined with cafés and shops. But back in the day, #13 Rue du Mont-Cenis was the...

Cabaret de Patachou

Cabaret de PatachouThis building, now a pleasant art gallery, is where singer Edith Piaf (1915-1963) once trilled “La Vie en Rose.” Piaf—a destitute teenager who sang for pocket change in the streets of pre-WWII Paris—was discovered by a nightclub owner and became a star. Her singing inspired the people of Nazi-occupied Paris. In the heady days after the war, she sang about the joyous, rosy life in the city. For more on this warbling-voiced singer, see here.

• Head back to the always-lively square, and stand on its cusp for the best perspective of...

Place du Tertre—Bohemian Montmartre

Place du Tertre—Bohemian MontmartreLined with cafés, shaded by acacia trees, and filled with artists, hucksters, and tourists, the scene mixes charm and kitsch in ever-changing proportions. The Place du Tertre has been the town square of the small village of Montmartre since medieval times. (Tertre means “stepped lanes” in French.)

In 1800, a wall separated Paris from this hilltop village. To enter Paris you had to pass tollbooths that taxed anything for sale. Montmartre was a mining community where the wine flowed cheap (tax-free) and easy. Life here was a working-class festival of cafés, bistros, and dance halls. Painters came here for the ruddy charm, the light, and the low rents. In 1860, Montmartre was annexed into the growing city of Paris. The “bohemian” ambience survived, and it attracted sophisticated Parisians ready to get down and dirty in the belle époque of cancan. The Restaurant Mère Catherine is often called the first bistro—this is where Russian soldiers first coined the word by saying, “I’m thirsty, bring my drink bistro!” (meaning “right away”).

The square’s artists, who at times outnumber the tourists, are the great-great-grandkids of the Renoirs, Van Goghs, and Picassos who once roamed here—poor, carefree, seeking inspiration, and occasionally cursing a world too selfish to bankroll their dreams.

• Plunge headlong into the square. The Montmartre TI (Syndicat d’Initiative) across the square sells good maps (daily 10:00-18:00, tel. 01 42 62 21 21). Just south of the square (in the far corner) is the quiet, tiny Place du Calvaire, with the recommended café Chez Plumeau (closed Tue Oct-April and Wed year-round). But for now continue west along the main drag, called...

Rue Norvins

Rue NorvinsMontmartre’s oldest and main street is still the primary commercial artery, serving the current trade—tourism.

• If you’re a devotee of Dalí, a detour left on Rue Poulbot will lead to the...

Dalí Museum (L’Espace Dalí)

Dalí Museum (L’Espace Dalí)This beautifully lit black gallery (well-described in English) offers a walk through statues, etchings, and paintings by the master of Surrealism. The Spaniard found fame in Paris in the 1920s and ’30s. He lived in Montmartre for a while, hung with the Surrealist crowd in Montparnasse, and shocked the world with his dreamscape paintings and experimental films. Don’t miss the printed interview on the exit stairs.

• Continue west down Rue Norvins a dozen steps to the intersection with Rue des Saules, where you’ll find a...

Boulangerie with a View

Boulangerie with a ViewThe venerable boulangerie (bakery) on the left, dating from 1900, is one of the last surviving bits of the old-time community, made famous in a painting by the artist Maurice Utrillo (see sidebar).

From the boulangerie, look back up Rue Norvins, then backpedal a few steps to catch the classic view of the dome of Sacré-Cœur rising above the rooftops.

• Let’s lose the tourists. Follow Rue des Saules downhill (north) onto the back side of Montmartre. A block downhill, turn right on Rue Cortot to reach the...

Montmartre Museum and Satie’s House

Montmartre Museum and Satie’s HouseIn what is now the museum (at 12 Rue Cortot), Pierre-Auguste Renoir once lived while painting his best-known work, Bal du Moulin de la Galette (pictured on here). Every day he’d lug the four-foot-by-six-foot canvas from here to the other side of the butte to paint in the open air (en plein air) the famous windmill ballroom, which we’ll see later.

A few years later, Utrillo lived and painted here with his mom, Suzanne Valadon. In 1893, she carried on a torrid six-month relationship with the lonely, eccentric man who lived two doors up at #6—composer Erik Satie, who wrote Trois Gymnopédies and who was eking out a living playing piano in Montmartre nightclubs.

The Montmartre Museum fills several floors in this creaky 17th-century manor house with paintings, posters, old photos, music, and memorabilia. If you pay the admission, you’ll see artifacts from the Butte’s 2,000-year history. There’s a headless St. Denis and an abbey bell from the hill’s religious origins. Next come photos of the gypsum quarries and flour-grinding windmills of the Industrial Age. Learn how Sacré-Cœur’s construction was an act of national penitence resulting from the Prussian invasion of 1870 (see here).

Then you reach Montmartre’s Golden Age, the cabaret years. There’s the original Lapin Agile sign, the famous Chat Noir poster, and Toulouse-Lautrec’s dashing portrait of red-scarved Aristide Bruant, the earthy cabaret singer and club owner. A scale model of the hill lets you find the famous cabarets and homes of the bohemians who lived here—Renoir, Picasso, Edith Piaf, Toulouse-Lautrec, and more.

You learn about the artsy inhabitants of this former house—Renoir, alcoholic Utrillo and his mother Valadon, and see paintings by her and her husband, André Utter. You’ll see more Toulouse-Lautrec posters and displays on the biggest and most famous cabaret of all, the cancan-kickers of the Moulin Rouge. Outside in the grounds, you have nice views over the hill’s vineyard.

• Return to Rue des Saules and walk downhill to...

La Maison Rose Restaurant

La Maison Rose RestaurantThe restaurant, made famous by an Utrillo painting, was once frequented by Utrillo, Pablo Picasso, and Gertrude Stein. Today it serves lousy food to nostalgic tourists.

• Just downhill from the restaurant is Paris’ last remaining vineyard.

Clos Montmartre Vineyard

Clos Montmartre VineyardWhat originally drew artists to Montmartre was country charm like this. Ever since the 12th century, the monks and nuns of the large abbey have produced wine here. With vineyards, wheat fields, windmills, animals, and a village tempo of life, it was the perfect escape from grimy Paris. In 1576, puritanical laws taxed wine in Paris, bringing budget-minded drinkers to Montmartre. Today’s vineyard is off-limits to tourists except during the annual grape-harvest fest (first Sat in Oct, www.fetedesvendangesdemontmartre.com), when a thousand costumed locals bring back the boisterous old days. The vineyard’s annual production of 300 liters is auctioned off at the fest to support local charities. Bottles average €45 apiece and are considered mediocre at best.

• Continue downhill to the intersection with Rue St. Vincent.

Au Lapin Agile Cabaret

Au Lapin Agile CabaretThe poster above the door gives the place its name. A rabbit (lapin) makes an agile leap out of the pot while balancing the bottle of wine that he can now drink—rather than be cooked in. This was the village’s hot spot. Picasso and other artists and writers (Renoir, Utrillo, Paul Verlaine, Aristide Bruant, Amedeo Modigliani, etc.) would gather for “performances” of serious poetry, dirty limericks, sing-alongs, parodies of the famous, or anarchist manifestos. Once, to play a practical joke on the avant-garde art community, patrons tied a paintbrush to the tail of the owner’s donkey and entered the resulting “abstract painting” in a show at the Salon. Called Sunset over the Adriatic, it won critical acclaim and sold for a nice price.

The old Parisian personality of this cabaret survives. Every night except Monday a series of performers takes a small, French-speaking audience on a wistful musical journey back to the good old days (for details, see here of the Entertainment in Paris chapter).

• Backtrack uphill on Rue des Saules to the boulangerie (at the intersection with Rue Norvins).

Circling around the right side of the boulangerie, go downhill (south). Don’t curve right on car-filled Rue Lepic; instead, go straight, down the pedestrian-only Place J. B. Clement, hugging the buildings on the left. Turn right on Rue Ravignan and follow it down to the leafy little square with the TIM Hôtel. Next to the hotel, at 13 Place Emile Goudeau, is...

Le Bateau-Lavoir (Picasso’s Studio)

Le Bateau-Lavoir (Picasso’s Studio)A humble facade marks the place where Modern art was born. Here, in a lowly artists’ abode (destroyed by fire in 1970, rebuilt a few years later), as many as 10 artists lived and worked. This former piano factory, converted to cheap housing, was nicknamed the “Laundry Boat” for its sprawling layout and crude facilities (sharing one water tap). It was “a weird, squalid place,” wrote one resident, “filled with every kind of noise: arguing, singing, bedpans clattering, slamming doors, and suggestive moans coming from studio doors.”

In 1904, a poor, unknown Spanish émigré named Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) moved in. He met dark-haired Fernande Olivier, his first real girlfriend, in the square outside. She soon moved in, lifting him out of his melancholy Blue Period into his rosy Rose Period. La belle Fernande posed nude for him, inspiring a freer treatment of the female form.

In 1907, Picasso started on a major canvas. For nine months he produced hundreds of preparatory sketches, working long into the night. When he unveiled the work, even his friends were shocked. Les Demoiselles d’Avignon showed five nude women in a brothel (Fernande claimed they were all her), with primitive mask-like faces and fragmented bodies. Picasso had invented Cubism.

For the next two years, he and his neighbors Georges Braque and Juan Gris revolutionized the art world. Sharing paints, ideas, and girlfriends, they made Montmartre “The Cubist Acropolis,” attracting freethinking “Moderns” from all over the world to visit their studios—the artists Amedeo Modigliani, Marie Laurencin, and Henri Rousseau (see here); the poet Guillaume Apollinaire; and the American expatriate writer Gertrude Stein. By the time Picasso moved to better quarters (and dumped Fernande), he was famous. Still, Picasso would later say, “I know one day we’ll return to Bateau-Lavoir. It was there that we were really happy—where they thought of us as painters, not strange animals.”

• Walk back half a block uphill and turn left on Rue d’Orchampt. Walk the length of this short street and into a tiny alley, which spits you out the other end at the intersection with Rue Lepic, where you’re face-to-face with a wooden windmill.

Moulin de la Galette

Moulin de la GaletteOnly two windmills (moulins) remain on a hill that was once dotted with 30 of them. Originally, they pressed monks’ grapes and farmers’ grain, and crushed gypsum rocks into powdery plaster of Paris. When the gypsum mines closed (c. 1850) and the vineyards sprouted apartments, this windmill turned into the ceremonial centerpiece of a popular outdoor dance hall. Renoir’s Bal du Moulin de la Galette (in the Orsay, see here) shows it in its heyday—a sunny Sunday afternoon in the acacia-shaded gardens with working-class people dancing, laughing, drinking, and eating the house crêpes, called galettes. Some call Renoir’s version the quintessential Impressionist work and the painting that best captures—on a large canvas in bright colors—the joy of the Montmartre lifestyle. The Moulin de la Galette restaurant offers good meals and a few historic black-and-white photos of the windmill and old Montmartre (recommended in the  Eating in Paris chapter).

Eating in Paris chapter).

• Follow Rue Lepic as it winds down the hill. The green-latticed building on the right side was also part of the Moulin de la Galette (the second surviving windmill is just above, through the trees). Rounding the bend, look to the right when you reach Rue Tourlaque. The building one block down Rue Tourlaque was...

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec’s House

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec’s HouseFind the building on the southwest corner (across the intersection on the left) with the tall, brick-framed art-studio windows under the heavy mansard roof. Every night Toulouse-Lautrec (1864-1901, see here)—a nobleman turned painter, whose legs were deformed in a horse-riding accident during his teenage years—would dress up here and then journey down Rue Lepic to the Moulin Rouge. One of Henri’s occasional drinking buddies and fellow artists lived nearby.

• Continue down Rue Lepic and, at #54, find...

Vincent van Gogh’s House

Vincent van Gogh’s HouseVincent van Gogh lived here with his brother from 1886 to 1888, enjoying a grand city view from his top-floor window. In those two short years, Van Gogh transformed from a gloomy Dutch painter of brown and gray peasant scenes into an inspired visionary with wild ideas and Impressionist colors.

• Follow Rue Lepic downhill as it makes a hard right at #36 and becomes a lively market street. Enjoy the small shops and neighborhood ambience. Two blocks down, on the corner to your right (at #15), you’ll find the pink...

Café des Deux Moulins

Café des Deux MoulinsThis café has become a pilgrimage site for movie buffs worldwide, since it was featured in the quirky 2001 film Amélie. Today it’s just another funky place with unassuming ambience and reasonably priced food and drinks, frequented by another generation of real-life Amélies who ignore the movie poster on the back wall (daily 7:00-24:00, 15 Rue Lepic, tel. 01 42 54 90 50).

• Now continue downhill on Rue Lepic to Place Blanche. On busy Place Blanche is the...

Moulin Rouge

Moulin RougeOoh la la. The new Eiffel Tower at the 1889 World’s Fair was nothing compared to the sight of pretty cancan girls kicking their legs at the newly opened “Red Windmill.” The nightclub seemed to sum up the belle époque—the age of elegance, opulence, sophistication, and worldliness. The big draw was amateur night, when working-class girls in risqué dresses danced “Le Quadrille” (dubbed “cancan” by a Brit). Wealthy Parisians slummed it by coming here.

On most nights you’d see a small man in a sleek black coat, checked pants, a green scarf, and a bowler hat peering through his pince-nez glasses at the dancers and making sketches of them—Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. Perhaps he’d order an absinthe, the dense green liqueur (evil ancestor of today’s pastis) that was the toxic muse for so many great (and so many forgotten) artists. Toulouse-Lautrec’s sketches of dancer Jane Avril and comic La Goulue hang in the Orsay (see reproductions in the entryway).

After its initial splash, the Moulin Rouge survived as a venue for all kinds of entertainment. In 1906, the novelist Colette kissed her female lover onstage, and the authorities closed the “Dream of Egypt” down. Yves Montand opened for Edith Piaf (1944), and the two fell in love offstage. It has hosted such diverse acts as Ginger Rogers, Dalida, and the Village People—together on one bill (1979). Mikhail Baryshnikov leaped across its stage (1986). And the club celebrated its centennial (1989) with Ray Charles, Tony Curtis, Ella Fitzgerald, and...a French favorite, Jerry Lewis.

Tonight they’re showing...well, find out yourself: Walk into the open-air entryway or step into the lobby to mull over the photos, show options, and prices. Their souvenir shop is back up Rue Lepic a few steps at #9.

• Our tour is over. The Blanche Métro stop is here in Place Blanche. (Plaster of Paris from the gypsum found on this mount was loaded sloppily at Place Blanche...the white square.) If you have more energy, my Rue des Martyrs boutique stroll (see here) starts a few hundred yards east of here, near Métro Pigalle. The area east of here, down Boulevard de Clichy, was known as...

Pig Alley

Pig AlleyThe stretch of the Boulevard de Clichy from Place Blanche to Place Pigalle is the den mother of all iniquities. Remember, this was once the border between Montmartre and Paris, where bistros had tax-free status, wine was cheap, and prostitutes roamed freely. Today, sex shops, peep shows, the Museum of Erotic Art, live sex shows, chatty pitchmen, and hot dog stands line the busy boulevard. Dildos abound.

In the Roaring Twenties, this neighborhood at the base of the hill became a new center of cabaret nightlife. It was settled by African American jazz musicians and WWI veterans who didn’t want to return to a segregated America. Black-owned nightclubs sprang up. There was Zelli’s (located at 16 bis Rue Fontaine, a block southeast of the Moulin Rouge), where clarinetist-saxophonist Sidney Bechet played. A block away was the tiny Le Grand Duc (at Rue Fontaine and Rue Pigalle), where poet Langston Hughes bused tables. Next door was the most famous of all, Bricktop’s (at #73 and then at 66 Rue Pigalle), owned by the vivacious faux-redhead who hosted Cole Porter, Duke Ellington, Picasso, the Prince of Wales, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Josephine Baker, and many more. The area was “Harlem East,” where rich and poor, black and white, came for a good time.

By World War II, the good times were becoming increasingly raunchy, and GIs nicknamed the Pigalle neighborhood “Pig Alley.” Today, though the government is cracking down on prostitution, and the ladies of the night are being driven deeper into their red-velvet bars as the area is gradually being gentrified, very few think of the great French sculptor Pigalle when they hear the district’s name. Bars lining the streets downhill from Place Pigalle (especially Rue Pigalle) are lively with working girls eager to share a drink with anyone passing by.